Abstract

Background

Scedosporium apiospermum (S. apiospermum) belongs to the asexual form of Pseudallescheria boydii and is widely distributed in various environments. S. apiospermum is the most common cause of pulmonary infection; however, invasive diseases are usually limited to patients with immunodeficiency.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old Chinese non-smoker female patient with normal lung structure and function was diagnosed with pulmonary S. apiospermum infection by metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). The patient was admitted to the hospital after experiencing intermittent right chest pain for 8 months. Chest computed tomography revealed a thick-walled cavity in the upper lobe of the right lung with mild soft tissue enhancement. S. apiospermum was detected by the mNGS of BALF, and DNA sequencing reads were 426. Following treatment with voriconazole (300 mg q12h d1; 200 mg q12h d2-d20), there was no improvement in chest imaging, and a thoracoscopic right upper lobectomy was performed. Postoperative pathological results observed silver staining and PAS-positive oval spores in the alveolar septum, bronchiolar wall, and alveolar cavity, and fungal infection was considered. The patient’s symptoms improved; the patient continued voriconazole for 2 months after surgery. No signs of radiological progression or recurrence were observed at the 10-month postoperative follow-up.

Conclusion

This case report indicates that S. apiospermum infection can occur in immunocompetent individuals and that the mNGS of BALF can assist in its diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, the combined therapy of antifungal drugs and surgery exhibits a potent effect on the disease.

Keywords: Metagenomic next-generation sequencing, Pulmonary infection, Scedosporium Apiospermum

Background

Scedosporium apiospermum (S. apiospermum) belongs to the asexual form of Pseudallescheria boydii, which is widely distributed in various environments. S. apiospermum is one of the most common causes of invasive fungal infection in patients with immune deficiencies, particularly after organ transplantation, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), cystic fibrosis lung disease, structural lung diseases, and long-term use of immunosuppressants or glucocorticoids. The most common infection site of S. apiospermum is the lungs, and the clinical symptoms are usually cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, fever, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Imaging changes associated with pulmonary S. apiospermum infection can be similar to those observed in pulmonary aspergillosis, such as typical fungal balls or non-specific, such as single or multiple nodular lesions with or without cavities, focal infiltration, phyllode infiltration, and bilateral diffuse infiltration. The key to effective treatment is an accurate and timely etiological diagnosis. Otherwise, delayed diagnosis may cause fatal consequences, especially for patients with suppressed immunity. However, it is noteworthy that S. apiospermum can also rarely infect people with normal immune function, similar to our case. Surgical resection has become an essential part of treatment [1–3]. We presented a rare case of a 54-year-old non-immunocompromised female patient who developed pulmonary S. apiospermum infection and was diagnosed with pulmonary S. apiospermum infection by metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), as well as the first literature review of pulmonary S. apiospermum infection in immunocompetent patients.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old Chinese non-smoker female, who worked in a chicken processing factory, experienced intermittent right chest pain with occasional dry cough for 8 months with no apparent trigger. Although the patient’s sputum acid fast staining was negative, she was receiving empirical anti-tuberculosis therapy (2021.04.10) (the specific drug is unknown) in another hospital since her chest computed tomography (CT), dated April 2, 2021, suggested pulmonary tuberculosis. Further, the patient developed skin itching and systemic redness, prompting the anti-tuberculosis drugs to be changed (the specific drug is unknown), however, shortness of breath and shivering occurred following 3 days of medication, and the patient was eventually switched to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin (HRE + Lfx) for tuberculosis therapy. Unfortunately, her symptoms and imaging manifestation did not improve, and the CT at Hechuan People’s Hospital on June 16, 2021, indicated a thick-walled cavity in the upper lobe of the right lung, with irregular morphology, uneven wall thickness, and mild soft tissue enhancement. On June 22nd, 2021, she was admitted to our department for further evaluation and treatment. During the investigation, the patient denied experiencing symptoms such as dyspnea, chest tightness, hot flashes, night sweats, hemoptysis, chills, or a high fever. No significant abnormality was observed in the physical examination, and auxiliary inspection results are demonstrated in Table 1. In particular, this patient had underwent the fungal culture of BALF and lung biopsy, but the results were all negative. The patient was initially diagnosed with bacteriologically negative pulmonary tuberculosis and continued with anti-tuberculosis therapy with HRE and Lfx. The BALF of the patient was sent to undergo mNGS analysis, and the mNGS result revealed that the patient suffered from S. apiospermum infection, and DNA sequencing reads were 426, followed by antifungal therapy with voriconazole (300 mg iv q12h d1; 200 mg q12h iv d2-d20). Chest enhanced CT suggested the possibility of lung cancer (Fig. 1A and B), and positron emission tomography/CT (PET-CT) indicated that peripheral lung adenocarcinoma was not excluded (SUVmax 2.8) (Fig. 2). No significant improvement was observed in her imaging manifestation after the post-treatment review (Fig. 1C and D), and the possibility of fungal infection along with pulmonary neoplasms was not completely excluded. Then a CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy was performed, whose pathological report suggested fibroproliferation with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 3). Although no evidence of pulmonary neoplasms was observed during the lung biopsy, a thoracoscopic right upper lobectomy and lymph node dissection were performed. During the surgery, no pleural effusion was observed, and the lesion was located in the upper lobe of the right lung, measuring about 3*3 cm, with complete excision of the diseased lobe. The postoperative pathological results revealed visible silver-stained (Fig. 4A) and PAS-positive (Fig. 4B) oval spores in the alveolar septum, bronchiole wall, and alveolar cavity, thus, indicating fungal infection. Lung biopsy tissue from the upper lobe of the right lung revealed metaplasia from alveolar to bronchial, along with partial bronchiectasis. In and around the cavity, there was a large amount of inflammatory cell infiltration and foam cell aggregation, accompanied by lymphoid tissue hyperplasia. Fiber hyperplasia was observed in some regions, and alveolar epithelial hyperplasia was also visible (Fig. 5). The patient continued to consume voriconazole (200 mg po bid) for 2 months after surgery, and the diagnosis and treatment process are indicated in Fig. 6. Chest imaging was followed up at 1, 2, and 10 months after surgery, and no signs of recurrence were observed (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

Detailed auxiliary inspection results

| Parameter | Result/Value |

|---|---|

| CBC | normal |

| Hepatic function | normal |

| Coagulation function | normal |

| Scr | normal |

| BUN | normal |

| Stool routine | normal |

| Urine routine | normal |

| Tuberculosis related | |

| PPD | negative |

| TB-Ab | negative |

| T-SPOT | negative |

| X-PERT | negative |

| Acid-fast bacilli in sputum | negative |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria | negative |

| Infection related | |

| CRP | normal |

| PCT | normal |

| ESR | normal |

| Nine respiratory pathogens | negative |

| Tumor related | |

| CYFRA21-1 | 3.4ng/ml(0-3.3) |

| ProGRP | 42.6pg/ml(25.3–77.8) |

| SCC | 1.2ng/ml(0-2.7) |

| CEA | 1.7ng/ml(0.2–10.0) |

| NSE | 12.1pg/ml(0-16.3) |

| Fungi related | |

| GM(plasma) test | negative |

| G(plasma) test | negative |

| GM(BALF) test | 1.24 |

| BALF culture | No fungal growth detected after 7-day culture |

| Smear of lung biopsy | No fungi found |

| Immune status | |

| HIV | negative |

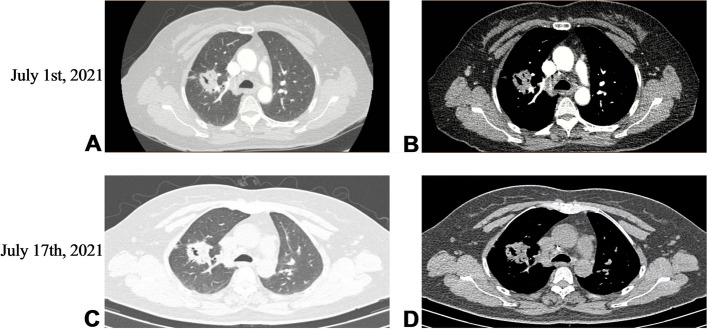

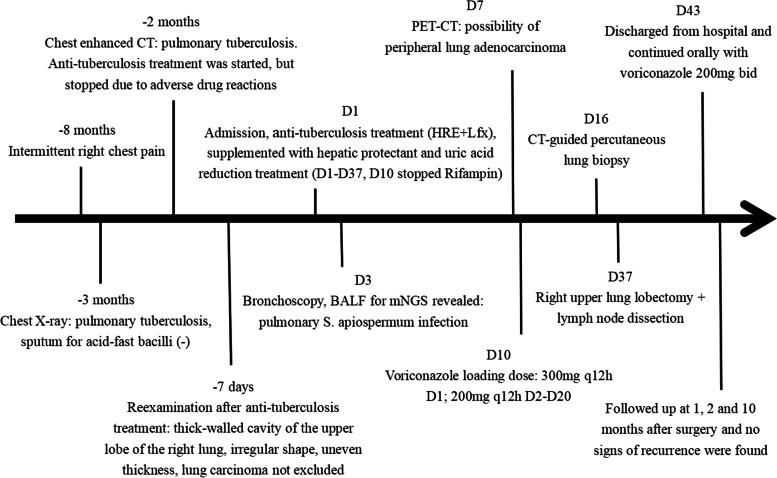

Fig. 1.

Chest CT at different time points. July 1st, 2021 Chest enhanced CT showed irregular soft-tissue density mass in the upper lobe of the right lung, and the bronchial branch of the upper lobe of the right lung was invaded and narrowed, which suggested a high possibility of lung cancer. There were also several small punctate calcification foci in the left lung (A). Slight calcification in mediastinum and left hilar lymph nodes (B). July 17th, 2021 After antifungal therapy, CT showed irregular soft tissue density shadow in the upper lobe of the right lung with cavity formation, which was considered to be lung cancer, with little change from the CT result before treatment (C, D)

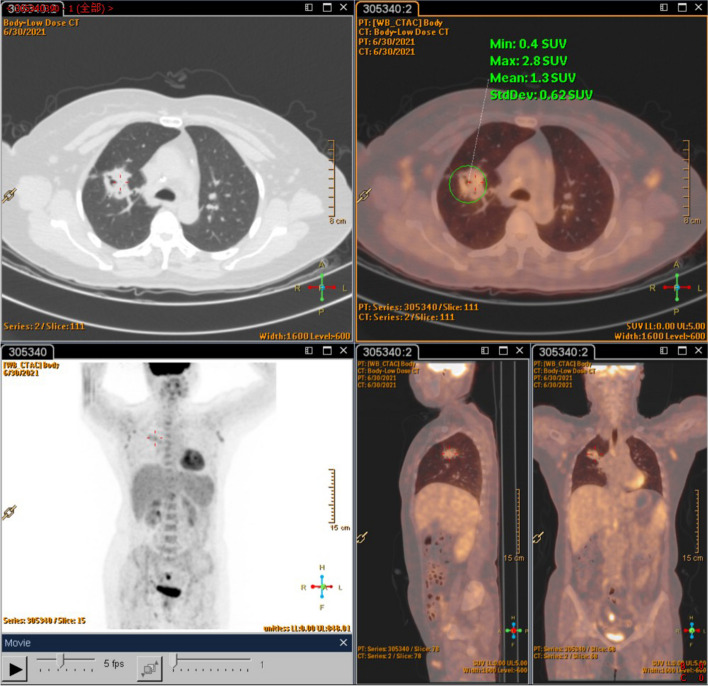

Fig. 2.

PET-CT. June 30th, 2021 PET-CT indicated space-occupying lesions in the upper lobe of the right lung with increased metabolic activity. Peripheral lung cancer was considered

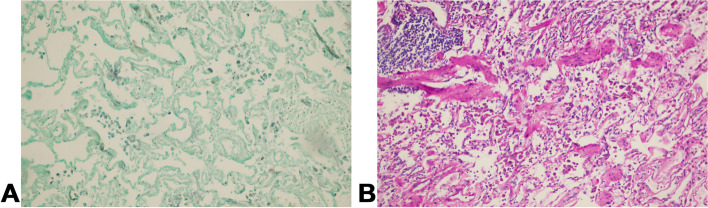

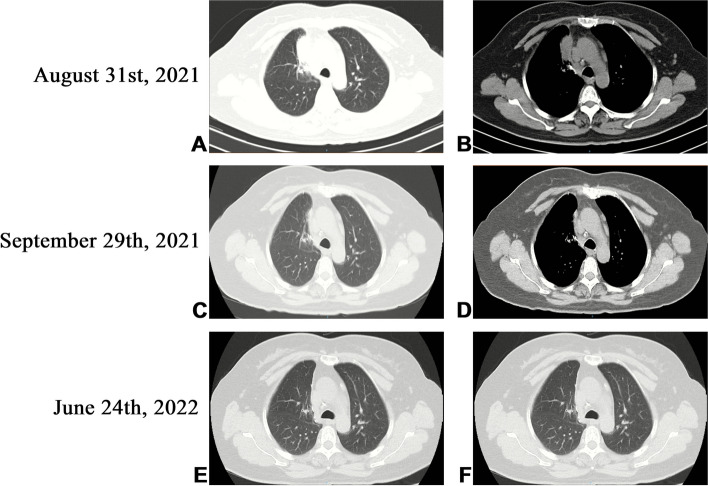

Fig. 3.

The pathological report of CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy suggested fibroproliferation with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration

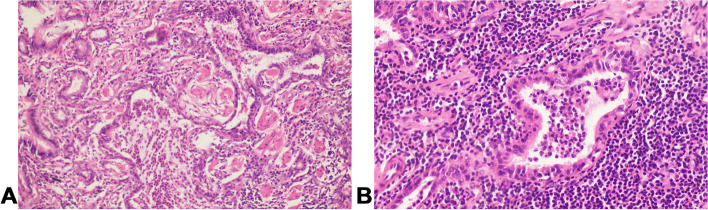

Fig. 4.

The postoperative pathological results of thoracoscopic right upper lobectomy and lymph node dissection showed that silver staining (A) and PAS positive (B) oval spores were found in alveolar septum, bronchiolar wall and alveolar cavity, suggesting fungal infection

Fig. 5.

Lung biopsy tissue from the upper lobe of the right lung revealed metaplasia from alveolar to bronchial, along with partial bronchiectasis. In and around the cavity, there was a large amount of inflammatory cell infiltration and foam cell aggregation, accompanied by lymphoid tissue hyperplasia. Fiber hyperplasia was observed in some regions, and alveolar epithelial hyperplasia was also visible

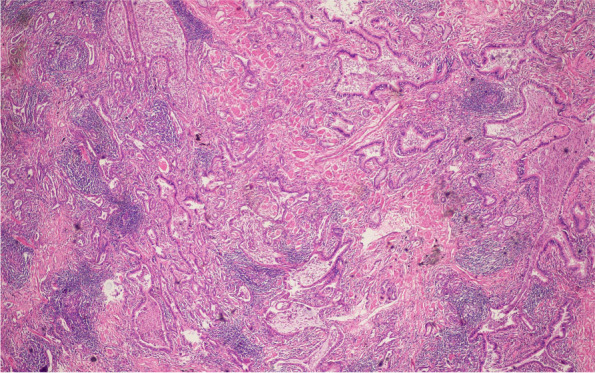

Fig. 6.

Timeline of events. A flowchart shows the patient’s entire diagnosis and treatment process

Fig. 7.

Postoperative reexamination of CT. August 31st, 2021. One month after surgery, HRCT showed the absence of the upper lobe of the right lung, the linear high-density shadow of the right hilar, and the adjacent patchy soft tissue shadow, considering the possibility of postoperative changes. There is a little effusion in the right interlobar fissure (A, B). September 29th, 2021. Two months after surgery, CT showed the absence of the upper lobe of the right lung, the linear high-density shadow of the right side of the lung, and the adjacent patchy soft tissue shadow, which was slightly smaller than that of 1 month after operation. There was a little effusion in the right interlobar fissure, which was slightly less than before (C, D). June 24th, 2022. Ten months after surgery, CT showed the absence of the upper lobe of the right lung, the linear high-density shadow in the right hilar area and the adjacent cord shadow, and the soft tissue shadow disappeared 2 months after operation (E, F)

Literature review

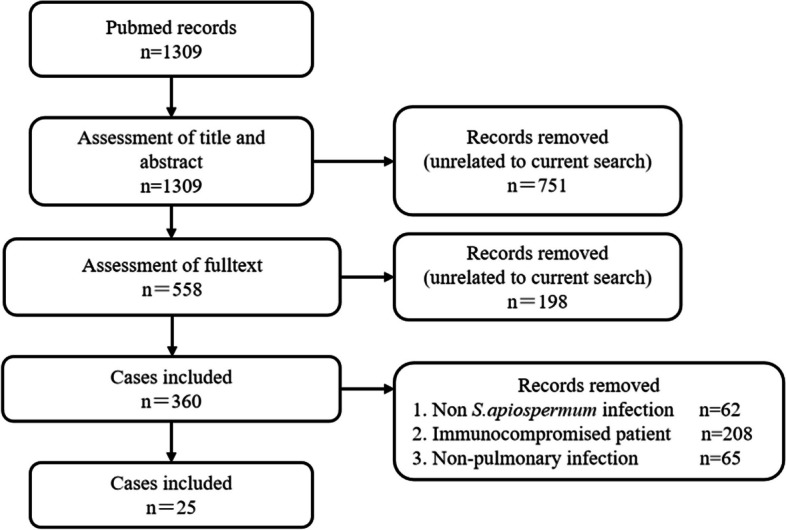

We searched the keywords “Pulmonary” or “Lung” and “Scedosporium” or “Scedosporiums” or “Scedosporium apiospermum” on the PubMed database, which had a total of 1309 articles. Subsequently, we excluded studies unrelated to current research, patients without S. apiospermum infections, patients with immunocompromised lung, and patients with non-pulmonary infections. Finally, 25 medical records with complete case report data were retrospectively analyzed [4–27]. The flow chart of the screening process is indicated in Fig. 8. The included patients were elaboratively summarized per the age, sex, major clinical manifestations, presence or absence of pre-existing disease, diagnostic methods, imaging manifestations, extensive or limited lesions, presence or absence of delay in diagnosis and treatment, treatment plan, and treatment outcome (Table 2).

Fig. 8.

Screening process. The flow chart shows the process of literature review

Table 2.

Brief summarization of included patients

| Characteristics | 25 patients |

|---|---|

| Sex (male / female) | 13/12 |

| Median age (year) | 55 (7–83) |

| Underlying disease | 21 (0.84) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 11 (0.44) |

| Pulmonary cystic fibrosis | 4 (0.16) |

| Bronchiectasis | 3 (0.12) |

| Previous diagnosis of S. apiospermum | 1 (0.04) |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1 (0.04) |

| Diabetes | 1 (0.04) |

| Previous tumor history | 1 (0.04) |

| Oral abscess | 1 (0.04) |

| No underlying disease | 4 (0.16) |

| Clinical manifestations | |

| Cough, Expectoration | 16 (0.64) |

| Hemoptysis | 12 (0.48) |

| Fever | 10 (0.40) |

| Dyspnea | 9 (0.36) |

| Night sweats | 3 (0.12) |

| Blood in sputum | 2 (0.08) |

| Weight loss | 3 (0.12) |

| Loss of appetite | 2 (0.08) |

| Chest pain | 2 (0.08) |

| Fatigue | 2 (0.08) |

| Pneumothorax | 1 (0.04) |

| Diagnosis time | |

| Misdiagnosed | 9 (0.36) |

| No misdiagnosis | 16 (0.64) |

| Diagnostic methods | |

| BALF culture | 13 (0.52) |

| Sputum culture | 7 (0.28) |

| Blood culture | 1 (0.04) |

| Lung biopsy tissue smear | 1 (0.04) |

| Lung biopsy tissue specimen culture | 2 (0.08) |

| Postoperative tissue culture | 4 (0.16) |

| DNA/RNA sequencing of BALF | 2 (0.08) |

| Lesion range | |

| Limited | 12 (0.48) |

| Extensive | 13 (0.52) |

| Treatment scheme | |

| Antifungal therapy | 15 (0.60) |

| Surgery treatment | 4 (0.16) |

| Antifungal + Surgery | 6 (0.24) |

| Prognosis | |

| Cure | 19 (0.76) |

| Improvement | 2 (0.08) |

| Death | 2 (0.08) |

| No mention | 2 (0.08) |

A total of 25 immunocompetent patients with pulmonary S. apiospermum infection were reported on PubMed, and the basic characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 3. In total, 12 females (48%) and 13 males (52%) were included; the average age of the patients was 50.96 years, ranging from 7 to 83 years. Of the included patients, 84% had the following symptoms: 16 with cough and expectoration (64%), 12 with hemoptysis (48%), 10 with fever (40%), nine with dyspnea (36%), and other symptoms including night sweats (12%), weight loss (12%), chest pain (8%), blood in the sputum (8%), anorexia (8%), fatigue (8%), and pneumothorax (4%). Cough and expectoration were the most common symptoms, followed by hemoptysis and fever. The severity of symptoms also varied, from inconspicuous pulmonary symptoms (three cases) to dyspnea (nine cases). Pulmonary tuberculosis was the most common underlying disease (11/25, 44%), followed by pulmonary cystic fibrosis (4/25, 16%) and bronchiectasis (3/25, 12%). The main diagnostic method was BALF culture in 13 cases (52%), followed by sputum culture in seven cases (28%), postoperative tissue culture in four cases (16%), lung biopsy and transbronchial lung biopsy in two cases (8%), gene sequencing of alveolar lavage fluid in two cases (8%), blood culture in one case (4%), and lung biopsy smear in one case (4%). Among the 25 patients included, four (16%) were treated with surgery, 15 (60%) with antifungal therapy (including one case with combined nebulized dornase Alfa and 7% hypertonic saline), and six (24%) were treated with surgery combined with antifungal therapy. Among these patients, treatment was delayed for nine (36%) patients, of which four (16%) were misdiagnosed as Aspergillus infections, one (8%) had empirical tuberculosis treatment, one (8%) whose prior bronchoalveolar lavage culture had later grown S. apiospermum and had been considered a contaminant, one patient (8%) had an unidentified fungus isolated from lung puncture biopsy, one patient (8%) had S. apiospermum detected in sputum three years prior deterioration, but the finding was disregarded, and one case (8%) was treated with antibiotics without finding etiological evidence. Fortunately, all of the above nine patients with delayed diagnosis were effectively treated after diagnosis of S. apiospermum infection. Out of the 25 reported cases, prognosis was not mentioned in two cases, in the remaining 23 cases mortality rate was 8.7% (2/23), cure rate was 82.6% (19/23), and 8.7% (2/23) of the patients showed improvement in their conditions. Of the cases that received only antifungal therapy, one died (6.7%, 1/15 cases). All four patients who received only surgical therapy were cured. Of the patients who received surgery in combination with antifungal therapy, treatment was effective in five cases (83.3%, 5/6 cases). The majority of hosts with normal immune function had a favorable prognosis, however, factors such as prolonged disease duration, underlying diseases, and delayed diagnosis and treatment may have caused the death.

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of included patients

| Case load | Age /Gender |

Symptom | Past medical history and associated risk factors | Diagnosis | Imaging performance | Limit/extensive | Delay diagnosis or not | Therapy | Outcome | The year of publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [4] | 44/female |

Hemoptysis Cough Blood in sputum Weight loss Anorexia |

None | BALF culture | Hollow lesion in the left upper lobe, Bronchiectasia | Limit | Yes, Anti-TB Antibiotic treatment |

Voriconazole → Surgery→ Voriconazole |

Cure | 2020 |

| 2 [5] | 73/female | None | None | BALF and TBLB sample culture | Single bossing | Limit | No | Surgery | Cure | 2018 |

| 3 [6] | 72/male |

Fever Hemoptysis |

TB at the age of 30 years | Sputum culture |

Hollow lesion pulmonary infiltration, Air crescent sign |

Extensive |

Yes, Misdiagnosed as aspergillus infection |

Miconazole | Not mention | 2005 |

| 4 [7] | 24 /male |

Chronic cough Expectoration Intermittent Hemoptysis |

Tooth decay recurrent oral abscesses |

Lung biopsy culture |

Hollow lesion typical of a fungal ball |

Limit |

Yes, Antibiotic treatment |

Itraconazole →Surgery | Not mention | 2005 |

| 5 [8] | 47 /male |

Hemoptysis Cough Expectoration Dyspnea |

TB for 6 years | Sputum culture |

Fungal bulb, Bilateral uneven infiltrating foci |

Limit | No | Itraconazole →Surgery | Cure | 2014 |

| 6 [9] | 59 /female | Fever | None | BALF culture and DNA sequence | Infiltrates and nodular lesions on both sides of the lungs | Extensive |

Yes, Misdiagnosed as aspergillus infection, treated with micafengin, in parallel with empiric antimicrobial therapy |

Voriconazole, Liposomal Amphotericin |

Improve | 2011 |

| 7 [10] | 26 /male |

Cough Expectoration Fever Spontaneous Pneumothora Fungal empyema |

S. apiospermum infection | BALF culture |

Bronchiectasia Multiple cavities with nodules Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes |

Extensive | No |

Posaconazole →Surgery→ Posaconazole |

Cure | 2011 |

| 8 [11] | 40/male |

Cough Hemoptysis |

TB for 15 years | Postoperative specimens culture |

Typical fungal balls Air crescent sign |

Extensive |

Yes, Misdiagnosed as TB and Aspergillus infection |

Voriconazole | Cure | 2016 |

| 9 [12] | 51/female |

Dry cough Night sweats |

None | BALF culture | Hollow lesion Airway dilation | Limit |

Yes, considered as contaminant |

Voriconazole → Surgery |

Cure | 2017 |

| 10 [13] | 83/female |

Cough Blood in sputum Fatigue Dyspnea |

Bronchiectasia COPD Chronic atrial fibrillation |

BALF culture |

Bronchiectasia Tree bud sign |

Limit | No | Voriconazole | Cure | 2021 |

| 11 [14] | 72/female |

Hemoptysis Fever Polypnea |

Pulmonary arterial hypertension | Boold culture | Both lungs are scattered in blurred patches | Extensive | No | Voriconazole and Amphotericin B →Terbinafine | Cure | 2020 |

| 12 [15] | 67/male |

Hemoptysis Fever |

Non-tuberculous Mycobacte for 15 years | BALF culture | Fungal sphere cavular lesions | Limit | No | Voriconazole | Cure | 2021 |

| 13 [16] | 67/male |

Cough Hemoptysis Dyspnea |

Bronchiectasia TB |

BALF culture |

Hollow lesions Bronchiectasia Tree bud sign |

Extensive |

Yes, Antibacterial therapy |

Itraconazole Voriconazole |

Cure | 2015 |

| 14 [17] | 71/male |

Fever Cough Expectoration |

TB Hypertension |

BALF culture and lung tissue biopsy smear |

Hollow lesions Fungal sphere-like shadows |

limit |

Yes, Misdiagnosed as Aspergillus |

Voriconazole | Cure | 2011 |

| 15 [18] | 74/female | None | Mycobacterium tuberculosis avium infection | BALF culture |

Bronchiectasia, Cavity, Nodules |

Extensive | No | Voriconazole | Cure | 2020 |

| 16 [19] | 54/female |

Fever Dry cough Dyspnoea Weight loss |

TB | Sputum culture | Left lower lung infiltration and diffuse small nodular infiltration in the right lung | Extensive | No | Miconazole nitrate Ketoconazole | Cure | 1997 |

| 17 [20] | 68/male |

Cough Purulent sputum Hemoptysis Night sweats Fever Dyspnea Weight loss Fatigue Anorexia |

TB 40 years before | Sputum culture | A thick walled cavity with necrosis | Extensive | No |

Voriconazole →Surgery |

Death | 2007 |

| 18 [21] | 36/female |

Chest pain Fever Cough Purulent sputum Dyspnea |

DM | Postoperative tissue culture | A nodular mass with meniscus sign in the right lower lobe with undefined border | Limit | No | Surgery | Cure | 2004 |

| 19 [22] | 57/female |

Right-side chest pain Hemoptysis |

TB | Postoperative tissue culture |

Partial fibroatelectasic retraction of the left upper lobe and a thin-walled cavity |

Limit | No | Surgery | Cure | 2004 |

| 20 [22] | 61/female |

Cough Hemoptysis |

TB | Sputum culture and BLAF culture | Numerous cavities with indwelling fungal balls Bronchiectasis | Extensive | No | Voriconazole and Bronchial artery embolism | Cure | 2011 |

| 21 [23] | 55/male | none | History of bladder cancer | Post-operative tissue culture | Air crescent sign | Limit | No | Surgery | Cure | 2002 |

| 22 [24] | 17/male |

Hemoptysis Respiratory failure |

Pulmonary cystic fibrosis | BALF Gene sequencing | Severe spongous lung destruction | Extensive |

Yes, Delayed treatment |

Venous Voriconazole and Liposomal Amphotericin B→nebulidized Voriconazole and intravenous Voriconazole |

Cure | 2014 |

| 23 [25] | 37/male |

Cough Expectoration |

Pulmonary cystic fibrosis Bronchiectasia |

Sputum culture |

Bronchiectasis Air crescent sign Hollow lesions |

Extensive | No | Intravenous Voriconazole → nebulidized Voriconazole and Amphotericin B | Death | 2010 |

| 24 [26] | 7/female |

Fever Dyspnea Cough |

Pulmonary cystic fibrosis | BALF culture and sputum culture | Multiple bronchiectasis and bronchial thickening | Extensive | No | Amphotericin B Itraconazole | Cure | 2006 |

| 25 [27] | 12/male |

Dry cough Dyspnea |

Pulmonary cystic fibrosis | BALF culture | Peribronchial thickening in lower lobes | Limit | No | Voriconazole → nebulidized dornase Alfa and 7% hypertonic saline | Improve | 2015 |

Discussion and conclusions

S. apiospermum is widely distributed in various environments, such as contaminated water, wetlands, sewage, and saprobic heritage [28]. Most of the infections occur in patients with immune deficiency, such as those with AIDS, malignant tumors, long-term use of immunosuppressants or glucocorticoids, and organ transplantation, which can cause fatal disseminated infection [29–32]. Additionally, it can occur in patients with normal immune function [4–27]. Our literature review revealed that 11 patients (44%) had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis infection, which was consistent with Kantarcioglu et al.‘s hypothesis that pulmonary tuberculosis infection was the main risk factor for S. apiospermum pulmonary infection [33].

It has been reported that the risk factors for S. apiospermum infection in immunocompromised patients include lymphopenia, neutropenia, and serum albumin levels of < 3 mg/dL [30]. In immunocompetent patients, the main risk factors for S. apiospermum infection are surgery or trauma [34], and the lung and upper respiratory tract are the most infected sites. These infections fall into the following categories: Transient local colonization, bronchopulmonary saprobic involvement, fungus ball formation, and invasive S. apiospermum pneumonia [1]. Among the clinical features of S. apiospermum pulmonary infection, fever is the most common clinical sign and symptom in most cases, and other common symptoms are cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain [35]. The imaging manifestations of S. apiospermum pulmonary infection are similar to those of other infections, such as the formation of fungus balls in preexisting cavities, which is difficult to differentiate from an Aspergillus ball using radiograms. It may also exhibit solitary or multiple nodular lesions with or without cavitation, focal, lobar, or bilateral diffused infiltration [1]. Consistent with our literature review, S. apiospermum infection is frequently misdiagnosed as pulmonary aspergillosis or tuberculosis given the non-specific imaging features [6, 9, 11, 17]. The imaging of our patient presented thick-walled cavities in the right upper lobe, with uneven thickness, an irregular shape, and adjacent pleural adhesion, which are non-specific for pulmonary infections caused by S. apiospermum. Additionally, this patient experienced intermittent right chest pain and occasional dry cough for 8 months without an obvious trigger, which is consistent with tuberculosis symptoms. Prior to admission to our hospital, X-ray and CT conducted at another hospital was suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis. Therefore, since tuberculosis was highly suggested based on symptoms and imaging, with no apparent risk factors for fungal infections, empirical anti-tuberculosis therapy was initiated prior to antifungal therapy consistent with other reports [4, 36, 37].

S. apiospermum infection can be diagnosed by microbiology (including direct staining and culture), histopathology, and polymerase chain reaction to identify fungal DNA [38–41]. Additionally, serology can aid in the diagnosis as S. apiospermum infection through antigen detection using counter-immunoelectrophoresis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [42, 43]. However, owing to the cross-reactions with antigens from other fungi such as Aspergillus spp, this method was not reported in cases [43]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case to use mNGS of BALF in the diagnosis of pulmonary S. apiospermum infection. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of S. apiospermum infection can be fatal, particularly in immunocompromised patients. mNGS can provide rapid and reliable method and offer a valuable diagnostic support, thereby avoiding delays in diagnosis and treatment.

In immunocompromised patients, infections caused by S. apiospermum are difficult to treat and usually fatal, whereas immunocompetent hosts had a better prognosis [1]. S. apiospermum infection is difficult to treat as it has been reported to be resistant to many antifungal agents, such as fluconazole, ketoconazole, flucytosine, terbinafine, itraconazole, and liposomal amphotericin B, however, it is susceptible to voriconazole, and a few studies have reported its efficacy in the treatment of S. apiospermum infection [5, 29, 44, 45]. According to the literature, surgical excision is an effective treatment for infections caused by S. apiospermum when lesions are localized [1]. Even in immunocompetent patients, infections caused by this pathogen often require surgical excision [1]. According to Liu et al.‘s a meta-analysis and systematic review of pulmonary S. apiospermum infection, more than half of the immunocompetent patients with pulmonary infection received surgical treatment, however, this did not cause a better overall survival rate [46]. However, since antifungal therapy failure is more common in immunocompromised patients, surgical resection may help to improve survival rates, whereas immunocompetent patients treated with antifungal therapy alone may have a good prognosis [46]. The overall mortality for pulmonary S. apiospermum infection in patients with the normal immune function was 12.5% (5/40), and among them who received surgery, the mortality was 9.09% (2/22), while the patients without surgery had a mortality of 16.67% (3/18) [46]. Our literature review revealed that the total mortality, the rate of patients who were cured, and improvement rates of 25 patients with normal immune function were 8.7%, 82.6%, and 8.7%, respectively. One patient who received antifungal treatment alone died (6.7%, 1/15), whereas four patients who received surgical treatment were cured, and five patients (83.3%, 5/6) responded favorably to surgery combined with antifungal therapy. In this case, the patient’s immune function and lung structure were normal. The reasons for surgical excision were as follows: (1) Based on the PET-CT report, it was suggested that the local metabolic activity of the upper lobe of the right lung was high (SUVmax = 2.8), and peripheral gonadal carcinoma was suspected; (2) Following antifungal treatment, the foci were not healed, and the possibility of pulmonary fungal infection complicated with lung cancer could not be excluded. The surgery aimed to remove the foci and actively resect the pulmonary tumor simultaneously based on a reported case of pulmonary S. apiospermum infection with pulmonary tumorlets in an immunocompetent patient [5]. The patient was followed up for 10 months after surgery, and the symptoms of dry cough and chest pain had improved, with the chest CT indicating effective treatment.

Based on our case and literature review, despite the absence of trauma or surgery, people with normal immune function and lung structure can also be infected with S. apiospermum. This case highlights mNGS in the clinical diagnosis of pulmonary invasive fungal disease. For traditional culture fail to provide clear pathogenic evidence, it is a rapid and reliable test to avoid the adverse consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment. The combination of antifungal therapy and surgery is effective in the treatment of local lesions of pulmonary infection caused by S. apiospermum in hosts with normal immune function, especially when patients suffers from S. apiospermum infection combined with tumors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- S. apiospermum

Scedosporium apiospermum

- mNGS

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- BALF

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- CT

Computed tomography

- PET-CT

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

Authors' contributions

JH, LL and RD conducted the literature review and edited the case presentation. QL and CL collected clinical data. XW, YZ and RZ provided valuable feedback for the report. HD reviewed and revised the manuscript. JH and LL contributed equally to this work. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University(Approval number K2023-107). Informed written and signed consent for participation from the patient was acquired prior to the submission.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jingru Han and Lifang Liang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, et al. Infections caused by scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):157–197. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas AP, Chen SC, Slavin MA. Emerging infections caused by non-aspergillus filamentous fungi. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(8):670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramirez-Garcia A, Pellon A, Rementeria A, et al. Scedosporium and lomentospora: an updated overview of underrated opportunists. Med Mycol. 2018;56:102–125. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu W, Feng RZ, Jiang HL. Management of pulmonary scedosporium apiospermum infection by thoracoscopic surgery in an immunocompetent woman. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(7):300060520931620. doi: 10.1177/0300060520931620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motokawa N, Miyazaki T, Hara A. Pulmonary scedosporium apiospermum infection with pulmonary tumorlet in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2018;1(23):3485–3490. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.1239-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koga T, Kitajima T, Tanaka R. Et a1. Chronic pulmonary scedosporiosis simulating aspergillosis. Respirology. 2005;10(5):682–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernando SSE, Jones P, Vaz R. Fine needle aspiration of a pulmonary mycetoma. A case report and review of the literature. Pathology. 2005;37(4):322–324. doi: 10.1080/00313020500168786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agatha D, Krishnan KU, Dillirani VA. Et a1. Invasive lung infection by Scedosporium apiospermum in an immunocompetent individual. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57(4):635–637. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.142716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura Y, Utsumi Y, Suzuki N. Et a1. Multiple scedosporium apiospermum abscesses in a woman survivor of a tsunami in northeastern Japan: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;25: 526 . doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan T, Nicholson S, Fahy R. Pneumothorax and Empyema complicating Scedosporium apiospermum mycetoma: not just a problem in the immunocompromised patients. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(4):931–932. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman FU, Irfan M, Fasih N. Pulmonary scedosporiosis mimicking aspergilloma in an immunocompetent host: a case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2016;44(1):127–132. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0840-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma KC, Pino A, Narula N. Et a1. Scedosporium Apiospermum mycetoma in an immunocompetent patient without prior lung disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(1):145–147. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201609-697LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mir MAY, Shrestha DB, Suheb MZK. Scedosporium apiospermum pneumonia in an immunocompetent host. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e16891. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabr R, Hammoud K. Scedosporium Apiospermum fungemia successfully treated with voriconazole and terbinafine. IDCases. 2020;8:e00928. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogata H, Harada E, Okamoto I. Scedosporium apiospermum lung disease in a patient with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Respirol Case Rep. 2020;9(1):e00691. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz R, Barros M, Reyes M. Pulmonary non invasive infection by Scedosporium Apiospermum. Rev Chil Infectol. 2015;32(4):472–475. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182015000500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata R, Hagiwara E, Shiihara J. A case of lung scedosporiosis successfully treated with monitoring of plasma voriconazole concentration level. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;49(5):388–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimeno VM, Muñoz EC. Diagnosis of a typical mycobacterial and fungal coinfection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2020;9(4):435–437. doi: 10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_98_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekavec J, Mlinarić-Missoni E, Babic-Vazic V. Pulmonary tuberculosis associated with Invasive Pseudallescheriasis. Chest. 1997;111(2):508–511. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abgrall S, Pizzocolo C, Bouges-Michel C. Scedosporium apiospermum lung infection with fatal subsequent postoperative outcome in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;15(4):524–525. doi: 10.1086/520009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severo LC, Oliveira FM, Irion K. Respiratory tract intracavitary colonization due to Scedosporium apiospermum: report of four cases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2004;46(1):43–46. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652004000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durand CM, Durand DJ, Lee R. A 61 year-old female with a prior history of tuberculosis presenting with hemoptysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;1(7):910. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Refaï MA, Duhamel C, Rochais GPL. Lung scedosporiosis: a differential diagnosis of aspergillosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(5):938–939. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holle J, Leichsenring M, Meissner PE. Nebulized voriconazole in infections with scedosporium apiospermum — case report and review of the literature. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(4):400–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borghi E, Iatta R, Manca A. Chronic airway colonization by Scedosporium apiospermum with a fatal outcome in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Med Mycol. 2010;48(Suppl 1):108–113. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.504239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vázquez-Tsuji O, Rivera TC, Zárate AR. Endobronchitis by Scedosporium apiospermum in a child with cystic fibrosis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2006;23(4):245–248. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(06)70054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padoan R, Poli P, Colombrita D. Acute Scedosporium apiospermum endobronchial infection in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(6):701–702. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaltseis J, Rainer J, De Hoog GS. Ecology of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium species in human- dominated and natural environments and their distribution in clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2009;47(4):398–405. doi: 10.1080/13693780802585317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husain S, Munoz P, Forrest G. Et a1. Infecfions due to Scedosporium apiospermum and scedosporium prolificans in transplant recipients: clinical characterstics and impact of alltlfungal agent therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(1):89–99. doi: 10.1086/426445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamaris GA, Chamilos G, Lewis RE, et al. Scedospodum infection in atertiary care cancer center: a review of 25 caes from 1989–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(12):1580–4. doi: 10.1086/509579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridde UJ, Chenoweth CE, Kauffman CA. Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection in a previously healthy woman with HELLP syndrome. Mycoses. 2004;47(9):442–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortoneda M, Pastor FA, Mayayo E. Et a1. Comparison of the virulence of Scedosporium prolificans strains from different origins in a murine model. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51(11):924–928. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-11-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantarcioglu AS, de Hoog GS, Guarro J. Clinical characteristic and epidemiology of pulmonary pseudallescheriasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2012;29(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castiglioni B, Sutton DA, Rinaldi MG. Pseudallescheria boydii (Anamorph Scedosporium apiospermum). Infection in solid organ transplant recipients in a tertiary medical center and review of the literature.Medicine. (Baltimore) 2002;81(5):333–348. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lackner M, de Hoog GS, Verweij PE. Et a1. Species-specific antifungal susceptibility patterns of scedosporium and pseudallescheria species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2635–2642. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05910-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You CY, Hu F, Lu SW, et al. Talaromyces marneffei infection in an HIV-Negative child with a CARD9 mutation in China: a case report and review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2021;186(4):553–561. doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00576-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar N, Ayinla R. Endobronchial pulmonary nocardiosis. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(3):617–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman L, Standard PG, Jalbert M, et al. Immunohistologic identification of aspergillus spp. and other hyaline fungi by using polyclonal fluorescent antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(9):2206–2209. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2206-2209.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berenguer J, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Richard C, et al. Deep infections caused by Scedosporium prolificans. A report on 16 cases in Spain and a review of the literature. Scedosporium prolificans Spanish study group. Med (Baltim) 1997;76(4):256–265. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimura M, Maenishi O, Ito H, Ohkusu K. Unique histological characteristics of Scedosporium that could aid in its identification. Pathol Int. 2010;60(2):131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wedde M, Müller D, Tintelnot K, et al. PCR-based identification of clinically relevant pseudallescheria/Scedosporium strains. Med Mycol. 1998;36(2):61–67. doi: 10.1080/02681219880000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin-Souto L, Buldain I, Areitio M, et al. ELISA test for the Serological detection of Scedosporium/Lomentospora in cystic fibrosis patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:602089. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.602089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mina S, Staerck C, Marot A, et al. Scedosporium Boydii CatA1 and SODC recombinant proteins, new tools for serodiagnosis of Scedosporium infection of patients with cystic fibrosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;89(4):282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troke P, Aguirrebengoa K, Arteaga C, et al. Treatment of scedosporiosis with voriconazole: clinical experience with 107 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(5):1743–1750. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01388-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capilla J, Guarro J. Correlation between in vitro susceptibility of scedosporium apiospermum to voriconazole and in vivo outcome of scedosporiosis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(10):4009–4011. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.4009-4011.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu W, Feng RZ, Jiang HL. Scedosporium spp. lung infection in immunocompetent patients: a systematic review and MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98(41):e17535. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.