ABSTRACT

Flowers are colonized by a diverse community of microorganisms that can alter plant health and interact with floral pathogens. Erwinia amylovora is a flower-inhabiting bacterium and a pathogen that infects different plant species, including Malus × domestica (apple). Previously, we showed that the co-inoculation of two bacterial strains, members of the genera Pseudomonas and Pantoea, isolated from apple flowers, reduced disease incidence caused by this floral pathogen. Here, we decipher the ecological interactions between the two flower-associated bacteria and E. amylovora in field experimentation and in vitro co-cultures. The two flower commensal strains did not competitively exclude E. amylovora from the stigma habitat, as both bacteria and the pathogen co-existed on the stigma of apple flowers and in vitro. This suggests that plant protection might be mediated by other mechanisms than competitive niche exclusion. Using a synthetic stigma exudation medium, ternary co-culture of the bacterial strains led to a substantial alteration of gene expression in both the pathogen and the two microbiota members. Importantly, the gene expression profiles for the ternary co-culture were not just additive from binary co-cultures, suggesting that some functions only emerged in multipartite co-culture. Additionally, the ternary co-culture of the strains resulted in a stronger acidification of the growth milieu than mono- or binary co-cultures, pointing to another emergent property of co-inoculation. Our study emphasizes the critical role of emergent properties mediated by inter-species interactions within the plant holobiont and their potential impact on plant health and pathogen behavior.

IMPORTANCE

Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, is one of the most important plant diseases of pome fruits. Previous work largely suggested plant microbiota commensals suppressed disease by antagonizing pathogen growth. However, inter-species interactions of multiple flower commensals and their influence on pathogen activity and behavior have not been well studied. Here, we show that co-inoculating two bacterial strains that naturally colonize the apple flowers reduces disease incidence. We further demonstrate that the interactions between these two microbiota commensals and the floral pathogen led to the emergence of new gene expression patterns and a strong alteration of the external pH, factors that may modify the pathogen’s behavior. Our findings emphasize the critical role of emergent properties mediated by inter-species interactions between plant microbiota and plant pathogens and their impact on plant health.

KEYWORDS: Erwinia amylovora, Pseudomonas, Pantoea, emergent property, meta-transcriptome, co-culture, co-inoculation, fire blight, Malus domestica

INTRODUCTION

The flower microbiota provides a useful model for studying the ecological processes of plant microbiome assembly (1). These short-lived plant organs support the growth of a diverse community of microorganisms (2, 3). The microbial communities that inhabit flowers convey many functions including interactions with pollinators, altering flower chemistry, and providing a potential defense mechanism against floral pathogens (1, 4). The inter-species interactions between plant microbiota and plant pathogens may lead to properties that mediate disease suppression (5, 6). Exploring these interactions within the plant holobiont could reveal new mechanisms to control plant diseases and promote plant health.

Flowers are nutrient-rich microbial habitats coveted by plant pathogens (7). Erwinia amylovora is a pathogen that infects several plant species of the Rosaceae family (8). This bacterium causes fire blight, which incurs significant losses in pome fruit production. Conventional management of fire blight relies mainly on the prophylactic application of antibiotics, such as streptomycin, oxytetracycline, or, to a lesser extent, oxolinic acid or kasugamycin (9). However, these management strategies lead to the evolution of antibiotic resistance in E. amylovora (9). The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains drives pressure to develop sustainable practices to control fire blight. Microbial inoculants offer alternative strategies to protect plants against pathogens. Examples include the bacterium Pantoea agglomerans, known to secrete antibiotics that inhibit E. amylovora in the field (10), or Pantoea vagans, which excludes the pathogen from the stigma by competing for limiting substrates (11, 12). Lytic phages have also been shown to protect against the fire blight disease (13). While the biological control of the fire blight by these microbial species is mainly mediated by competitive niche exclusion, direct antagonism, or competing for space and nutrients, little consideration is given to the role of inter-species interactions beyond competition that mediate the suppression of plant diseases (14).

In an earlier study, we showed that the co-inoculation of Pseudomonas CT-1059 (Ps) and Pantoea CT-1039 (Pa), two bacterial strains isolated from apple flowers, leads to reduced disease incidence in experimental orchards (15). These two microbiota members did not show evidence of strong inhibitory interactions against E. amylovora in culture, and disease suppression was highest in the presence of both inoculated strains, suggesting that ecological interactions among the members likely accounted for the suppression of the fire blight disease (15). In the present study, we aimed to decipher the ecological interactions between the two flower-associated bacteria (i.e., Ps and Pa) and the fire blight bacterium E. amylovora using field co-inoculations and laboratory co-culture growth conditions. We hypothesized that bacterial inter-species interactions may alter pathogen activity and promote plant health. To this end, we investigated the potential of co-inoculation of Ps and Pa to influence the establishment, survival, and activity of the pathogen E. amylovora. Using synthetic stigma exudation medium (16), we characterized how strain co-cultures altered bacterial growth and gene expression. This study demonstrates that ecological interactions between microbiota commensals and plant pathogens are inherently complex and could lead to emergent functions with significance to plant health.

RESULTS

Co-inoculation of two flower bacterial commensals reduces fire blight occurrence

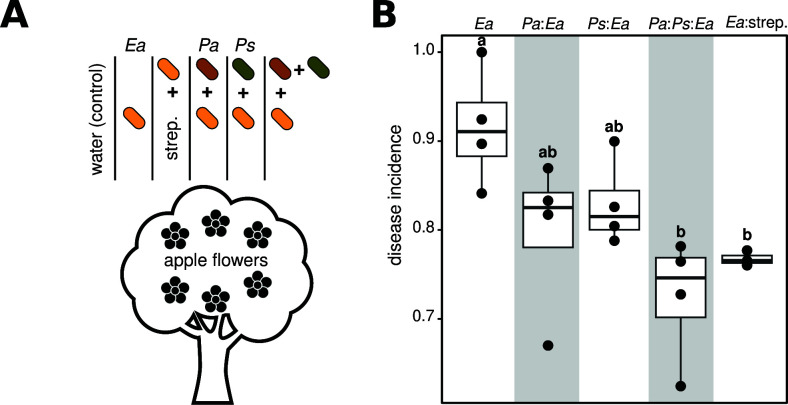

We showed previously that the probiotic co-inoculation of two flower-associated bacteria, Ps and Pa, reduces fire blight occurrence (15). The inoculation of these strains was repeated in this study (Fig. 1A; Materials and Methods). In brief, four trees of the apple cultivar “Red Delicious” were treated either with water (control), only the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora 110 (Ea), Pa or Ps followed by the inoculation of Ea (Pa:Ea or Ps:Ea, respectively), or mixture of Pa and Ps followed by Ea inoculation (Pa:Ps:Ea). The co-inoculation of both flower commensal bacteria significantly reduced fire blight incidence to a similar extent as the streptomycin treatment (Pa:Ps:Ea vs Ea:strep., respectively), whereas single isolate inoculations of Pa or Ps at the same cell concentration (either Pa:Ea or Ps:Ea) did not significantly reduce the disease incidence (Fig. 1B). These results verify our previous findings and show that the co-inoculation of these two flower commensal bacteria significantly reduce disease incidence in field experimentation, indicative of the role of ternary interactions between the species and the potential emergence of a microbial-mediated plant phenotype.

Fig 1.

Co-inoculation of two flower commensal bacteria reduces disease incidence in experimental orchards. (A) The drawing shows the experimental procedure of co-inoculating Pseudomonas and Pantoea on apple flowers “Red Delicious.” Briefly, apple trees were either inoculated with water (control), with Ea, with Ea than treated with streptomycin (Ea:strep), inoculated with Pantoea (Pa) or Pseudomonas (Ps) than treated with Ea (Pa:Ea or Ps:Ea, respectively), or co-inoculated with Ps and Pa then treated with Ea (Pa:Ps:Ea). (B) Boxplots show fire blight disease incidence in the field under the five treatments: Ea, Pa:Ea, Ps:Ea, Pa:Ps:Ea, and Ea:strep. Co-inoculation of the flowers with Pseudomonas and Pantoea significantly reduced fire blight incidence in the experimental field. Each circle corresponds to one tree; the letter indicates significant differences.

The pathogen E. amylovora remains abundant and active in apple flowers

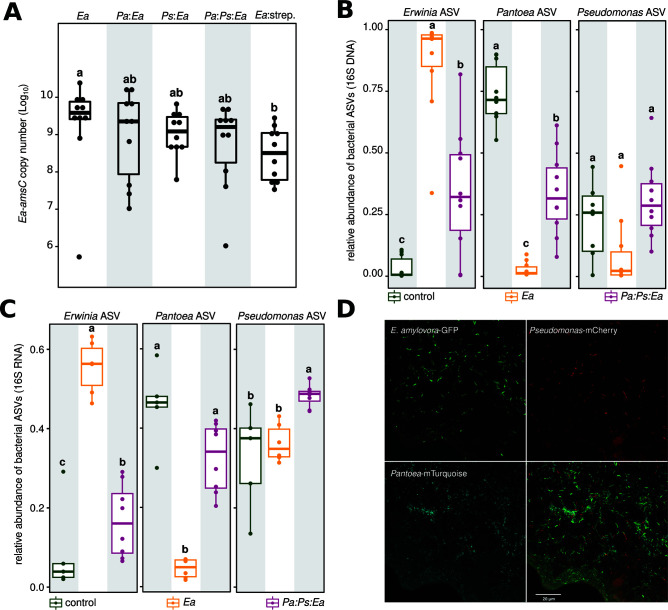

To investigate whether the flower commensal strains (i.e., Pa and Ps) exclude E. amylovora from colonizing the apple flowers, we quantified the pathogen abundance by measuring the copy number of E. amylovora-specific gene amsC (Fig. 1A). The mono- and co-inoculations of Pa, Ps did reduce in average amsC gene copy number in comparison to mono-inoculation treatments (Fig. 2A, Ps:Ea, Pa:Ea, Pa:Ps:Ea vs Ea, respectively); however, these reductions were not significant (Fig. 2A). In contrast, we observed that the application of streptomycin did significantly reduce Ea abundance in comparison to the control (Fig. 2A, Ea vs Ea:strep), but this reduction was not significantly different from mono- and co-inoculation treatments (Fig. 2A, Ea:strep. vs Pa:Ea, Ps:Ea, and Pa:Ps:Ea, respectively). These results demonstrate that neither inoculation of Pa, Ps or both excluded the pathogen E. amylovora from colonizing the apple flowers, but these bacteria may impede the optimal growth of E. amylovora in the flowers, to a similar level as streptomycin.

Fig 2.

The two flower commensal bacteria do not competitively exclude E. amylovora from the stigma. (A) The boxplots depict amsC gene copy number of E. amylovora on the flower stigma. Each circle corresponds to one flower, and letters indicate significant differences between treatments. E. amylovora was detected in all treatments. None of the inoculations significantly reduced the population size of Ea, except the application of streptomycin. (B and C) The boxplots show the relative abundance of Erwinia amplicon sequence variant (ASV), Pantoea ASV, and Pseudomonas ASV revealed by amplicon sequencing of the 16S gene and gene transcript, respectively. Although co-inoculation of Pa and Ps reduced the relative abundance of Ea, the 16S gene (B) and gene transcript (C) of E. amylovora were readily detected in all treatments. (D) Micrographs show confocal microscopy of E. amylovora expressing Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP) (top left), Pseudomonas expressing mCherry (top right), Pantoea expressing mTurquoise (bottom left), and the overlay of the three channels (bottom right) on the stigma of apple flower. Ps and Pa were first inoculated on the stigma, then Ea was applied after 1 day. Microscopy pictures were acquired 2 days after the inoculation of Ea. All three bacterial strains are detected and express fluorescent proteins on the stigma of apple flowers.

Measuring bacterial abundance from the DNA pool, as with quantitative PCR (qPCR) of the amsC gene, recovers sequences from dormant and dead cells or even exogenous DNA. Thus, these assays may overestimate the abundance of the target organism. We hypothesized that the co-inoculation may alter the activity of the pathogen. To test this, we performed rRNA gene sequencing (rDNA) and rRNA gene transcript sequencing (rRNA). The rRNA gene represents the abundance of DNA and the rRNA transcripts, as a component of the ribosome, represents transcriptionally active cells. We limited our analysis to the samples treated with water (control), Ea, or Pa and Ps followed by Ea (Pa:Ps:Ea). Both Pa and Ps were detected in the control samples, displaying average relative abundances of 0.75 and 0.22 in the rDNA [Fig. 2B, Pantoea amplicon sequence variant (ASV), Pseudomonas ASV, control, respectively] and 0.45 and 0.32 in the rRNA (Fig. 2C, Pantoea ASV, Pseudomonas ASV, control, respectively). This observation reinforces the characterization that these two strains are common members of the apple stigma flora. Additionally, they emerged as significant contributors to the active microbial community, evident from their prevalence in the rRNA data sets (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Ea showed minimal presence in the water control samples, accounting for only 0.03 of the rDNA sequences (Fig. 2B, Erwinia ASV, control) and only 0.08 of the rRNA sequences (Fig. 2C, Erwinia ASV, control). These results suggest that E. amylovora naturally occurs with lower abundance within the apple flower microbiota.

The inoculation of E. amylovora led to a significant increase in the abundance of the pathogen in both the rDNA and rRNA pools (Fig. 2B and C, Erwinia ASV, respectively). Upon inoculation of Ea, there was little effect on the relative abundance of Ps as there were no significant differences in the relative abundance of the Pseudomonas ASV in either rDNA or rRNA pools (Fig. 2B and C, Pseudomonas ASV, respectively). Comparatively, inoculation of Ea showed a detrimental effect on Pa, which decreased significantly in abundance in both rDNA and rRNA pools (Fig. 2B and C, Pantoea ASV, Ea, respectively), suggesting reduced participation in both the total and the active communities. This trend suggests the possibility of a competitive interaction between the pathogen E. amylovora and the flower commensal Pantoea.

After the co-inoculation treatment, Ea was still readily detected, making up 0.34 of the rDNA and 0.16 of the rRNA pool (Fig. 2B and C, Erwinia ASV, Pa:Ps:Ea, respectively). Although there was no significant increase in the relative abundance of Ps in the rDNA pool upon the co-inoculation treatment, we observed a moderate but still significant increase in the rRNA pool for this bacterium (Fig. 2C, Pseudomonas ASV, Pa:Ps:Ea). On the contrary, the co-inoculation treatment led to a significant increase in the relative abundance of Pa in the rDNA pool, but this increase was less than the water control (Fig. 2B, Pantoea ASV, Pa:Ps:Ea vs control). In the rRNA pool, we observed a significant increase in Pa relative abundance, but this increase was not significantly different from the water control (Fig. 2C, Pantoea ASV, Pa:Ps:Ea vs control). Our findings suggest that a high inoculation of E. amylovora may displace a fraction of the Pantoea population, but this effect is overcome, to some extent, by re-inoculating the Pantoea strain. Yet, it is important to note that 16S rRNA gene sequencing produces abundances on a relative scale (17). Thus, increasing one member necessitates decreasing another member(s), even though the absolute abundance remains unchanged. This could partly explain why we do not observe significant changes in E. amylovora amsC copy numbers in the probiotic inoculation but relatively large reductions in the 16S rRNA/rDNA data sets. These observations reflect a better performance of Pa rather than a reduction in Ea and that makes up a substantial proportion of both the total and the active populations on the apple stigma. Thus, Ea does not appear to be competitively excluded from the stigma after the co-inoculation treatment. However, it is still plausible that the inoculations of the flower commensals decrease the abundance of the pathogen on the flowers.

As a final test to investigate whether the bacterial cells co-occur on the stigma, we visualized the colonization of the stigma of apple flowers by labeled bacteria that actively express fluorescent proteins (FP). Flowers were exposed to Pseudomonas CT1181 expressing mCherry FP, Pantoea CT-1039 expressing mTurquoise FP, and E. amylovora 1189 expressing green FP. Microscopic inspection of these stigmas showed that all three labeled strains actively expressed fluorescent proteins and co-existed in proximal vicinity to each other (Fig. 2D). By visually inspecting the micrographs, we could readily detect that Pantoea-mTurquoise, Pseudomonas-mCherry, and E. amylovora-GFP co-occur at micro-scale on the flower stigma (Fig. 2D). These results further corroborate that the flower commensal bacteria do not competitively exclude the pathogen E. amylovora, but they co-occur on the apple flowers, even in close vicinity, and E. amylovora remains alive and active as evidenced by expression of the fluorescent marker.

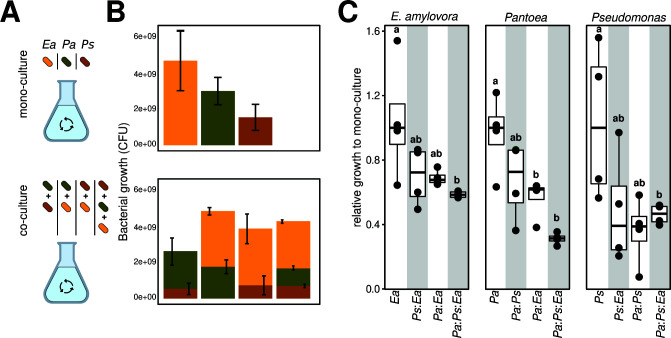

The pathogen and both flower commensal bacteria co-exist under co-culture growth conditions

Because both the pathogen (i.e., E. amylovora) and the commensal strains (i.e., Pa and Ps) co-exist on the apple flowers, we wanted to further investigate the interactions between these strains under in vitro conditions. Using a synthetic stigma exudate medium (16), we cultured the strains in mono- or co-association (Fig. 3A). After 6 h of growth under shaking, we counted colony-forming units (CFUs) for each strain by using selective antibiotics (Materials and Methods). In mono-cultures, the average cell densities of Ea reached 4.8 109 CFUs/mL, whereas Pa and Ps reached an average of 3.1 109 and 1.6 109 CFUs/mL, respectively (Fig. 3B, top panel). These results suggest that each strain reached similar population densities in the synthetic media, although Ea had the largest population size, followed by Pa and Ps. In pairwise and ternary co-cultures, the total bacterial density reached on average 2.68 109, 3.95 109, 4.37 109, and 4.94 109 CFUs/mL in Pa:Ps, Ps:Ea, Pa:Ps:Ea, and Pa:Ea co-cultures, respectively (Fig. 3B, bottom panel), suggesting similar cell densities were reached across the co-cultures. Importantly, none of the tested strains were competitively excluded in pairwise or ternary co-culture conditions. However, we noted a decrease in the relative growth of E. amylovora, Pantoea, and Pseudomonas upon ternary co-culture compared to the mono-culture (Fig. 3C, Pa:Ps:Ea). Together with the observations made in Fig. 2, these results demonstrate that these bacteria co-exist under in vivo and in vitro growth conditions. In fact, Ea consistently reached higher cell densities than the other strains in these conditions, providing further evidence that E. amylovora is not competitively excluded and co-exists with the two flower commensal bacteria.

Fig 3.

In vitro co-culture of the two flower commensal bacteria and the fire blight pathogen. (A) The schematic depicts in vitro mono- and co-culture of E. amylovora (Ea), Pantoea (Pa), and Pseudomonas (Ps) using a synthetic stigma exudation medium. (B) Bar plots show bacterial CFUs that were determined after 6 h post-inoculation using Lysogeny Broth agar with a selective antibiotic (Materials and Methods). The three bacterial species reached different growth rates in mono-culture, but none of the bacterial strains were out-competed in co-culture. (C) The boxplots show the relative growth of each bacterium in co-culture compared to its mono-culture growth condition. A relative growth >1 indicates that the strain grows more abundantly in the co-culture vs mono-culture, whereas a value <1 indicates otherwise. Boxplots labeled Ea, Pa, and Ps show growth variations in the mono-culture of E. amylovora, Pantoea, and Pseudomonas, respectively. Ternary co-culture of the bacteria leads to growth depletion, but none of the strain is out-competed to extinction.

Ternary inter-species interactions lead to the emergence of new expression patterns

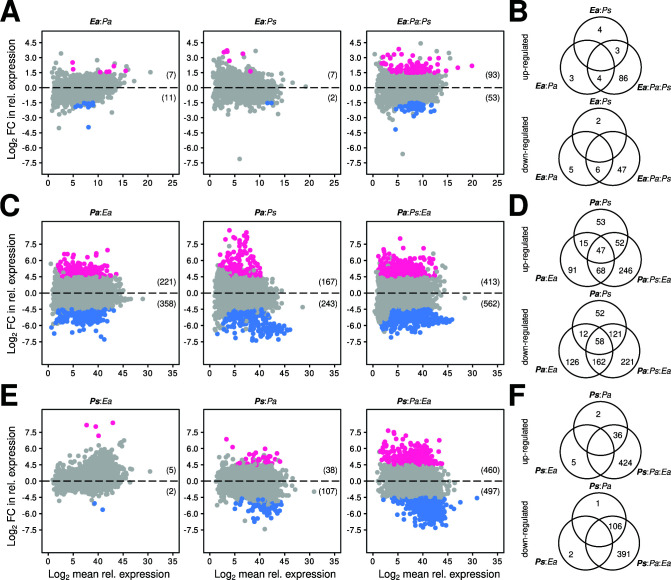

Next, we sought to understand how the co-culture of Pa, Ps, and Ea modulate gene expression in these three strains. We performed transcriptome analysis for the three strains in different strain assemblages including mono-cultures and binary and ternary cultures of Pa, Ps, and Ea (Fig. 3A). To quantify the changes in gene expression, we computed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by contrasting relative gene expression in co-cultures versus mono-culture growth conditions (Materials and Methods). The ternary co-culture combination (Fig. 4A, C, and E, 3rd panel) led to more DEGs than any binary co-culture growth conditions (Fig. 4A, C, and E, first and second panels) in all three strains tested. For example, we observed 146 DEGs (93 genes with increased expression and 53 genes with decreased expression) in E. amylovora grown in a ternary mixture compared to when Ea was grown in mono-culture (Fig. 4A, third panel). In contrast, binary co-culture of Ea with Pa or Ps led to only 18 and 9 DEGs of combined up- and down-regulated genes, respectively (Fig. 4A, first and second panels). Similar patterns were observed for Ps and Pa, with larger DEGs in ternary cultures than binary co-cultures (Fig. 4C and E, respectively). None of the DEGs in Ps and Ea were shared across all co-culture growth conditions (Fig. 4B and F, respectively). However, we noted 47 up-regulated and 58 down-regulated genes in Pa that were differentially regulated across all co-culture growth conditions (Fig. 4F). These findings highlight that the differentially expressed genes were not additive or predictable from binary interactions. Instead, the ternary inter-species interactions led to the emergence of new expression patterns for each member of this community.

Fig 4.

Co-culture of the three bacterial strains leads to new expression patterns. (A, C, and E) depict MA plots (log fold-change versus mean expression) showing DEGs in Ea, Pa, and Ps upon binary and ternary co-culture, respectively. Count data were fitted to negative binomial distribution (DESeq2) and DEGs were determined based on the cutoffs of 1.5 and 0.05 in log2 fold change expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value, respectively. Red and blue indicate significantly up- and down-regulated genes, and gray indicates no significant change in the expression. Numeric values indicate a total number of genes up- or down-regulated. Ternary co-culture of Ea, Pa, and Ps led to more DEGs in the three strains compared to their binary co-culture. (B, D, and F) show Venn charts indicating the number of DEGs shared between binary and ternary co-cultures in Ea, Pa, and Ps, respectively. Top Venn diagrams in (B, D, and F) correspond to significantly up-regulated genes Ea, Pa, and Ps respectively. Bottom Venn diagrams correspond to significantly down-regulated genes in Ea, Pa, and Ps, respectively. In Ea and Ps, we noted no core genes significantly up- or down-regulated shared between all co-culture growth conditions. Pa showed a small fraction of core genes significantly up- or down-regulated shared between all co-culture conditions.

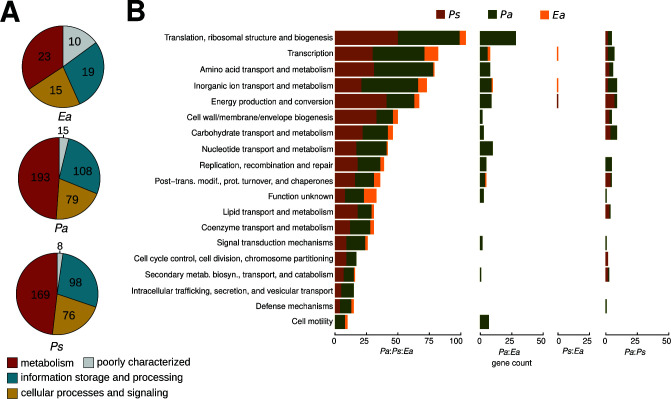

To characterize the functions associated with multi-strain interactions, we functionally annotated and classified DEGs to Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) (18, 19). The majority of DEGs in Ea (79 genes), Pa (395 genes), and Ps (351 genes) were not assigned to a molecular function or a biological process (Table S1). Among DEGs that can be assigned with known functions, most of these were metabolism-related genes with 34.3% or 23 DEGs in Ea, 48.8% or 193 DEGs in Pa, and 48.1% or 169 DEGs in Ps (Fig. 5A). Other DEGs identified belong to the categories of information storage and processing and cellular processes and signaling. Further characterization of the DEGs revealed that these genes cover a wide range of specific biological functions and processes (Fig. 5B). Importantly, several of the DEGs functions, such as intracellular trafficking and secretion and coenzyme transport and metabolism, were exclusively identified during Pa:Ps:Ea ternary interactions but not in any binary interactions. Other functions such as transcription or energy production and conversion were more represented in ternary interactions as compared to binary interactions (Fig. 5B). Notably, several DEGs were involved in the transport and metabolism of amino acids, inorganic ion, carbohydrate, nucleotide, and lipid in both commensal bacteria and the pathogen (Fig. 5B). We also identified DEGs belonging to ABC transporters (Fig. S1A), secretion systems (Fig. S1B), and prokaryotic defense systems (Fig. S1C). The gene set enrichment analysis of DEGs showed the over-represention of 19, 160, and 150 Gene Ontology (GO) terms in Ea, Pa and Ps, respectively (Table S2), whereas only 11 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) metabolic pathways were over-represented in the three bacterial strains (Table S3). To determine potential behavior changes of Ea during ternary interactions as compared to binary and mono-culture, we further examined functions of individual DEGs uniquely identified in Ea during ternary interactions (Table S1). Notably, two DEGs with functions related to virulence regulation were identified: slyA (Ea_01648) (20) and rcsB (Ea_02226) (21). Four DEGs related to motility were identified: sigma factor fliA (Ea_02027), flagellar regulator flk (Ea_02294), fliS (Ea_02031), and flagellar hook-associated protein 1 (Ea_01424). Six DEGs related to antimicrobial resistance/tolerance were identified: tripartite efflux system emrA (Ea_01261) and emrB (Ea_01390), fosmidomycin resistance protein (Ea_01027), blue copper oxidase CueO (Ea_00767), multidrug efflux pump accessory protein acrZ (Ea_01184), and outer membrane protease ompP (Ea_00731). Finally, we also identified nine DEGs related to stress response: clpB (Ea_02585), apaG (Ea_00661), peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase msrB (Ea_01894), phage-shock-protein (psp) operon transcriptional activator (Ea_01805), organic hydroperoxide resistance transcriptional regulator (Ea_03382), DNA damage-inducible protein I (Ea_01405), heat shock protein hspQ (Ea_01362) and ibpA (Ea_03427), and cold shock-like protein cspE (Ea_01091). Interestingly, several DEGs identified in Ea during ternary interactions are related to tolerance to acidic conditions, such as spermidine export protein mdtJ (Ea_02894) (22) and regulator of acid tolerance rcsB (Ea_02226) (21), which suggests a possible adaptation of E. amylovora to reduced pH in the growth milieu.

Fig 5.

Functional annotation of differentially regulated genes. (A) shows circle chart that depicts the proportion of the functional annotation of DEGs in Ea (top), Pa (middle), and Ps (bottom). Color code indicates category, and values inside the chart indicate gene counts. More DEGs are related to metabolism, than to information storage and processing, or cellular processes and signaling. (B) Barplots indicate the classes of COGs of the annotated DEGs in the three strains. Color denotes bacterial strain. Ternary co-culture results in the increase of DEGs and annotated COGs classes.

Several DEGs identified in Pa and Ps upon ternary co-culture are involved in microbe-microbe interactions (Table S1). These include toxin/antitoxin system genes (hicB Pa_01959, relB Pa_04496, relE Pa_04497, higB-1 Pa_02515, higB-2 Ps_01321, hipA Ps_03571, and fitB Ps_01790), quorum sensing (Ps_05074), iron utilization (Ps_03966), and biofilm formation (bdlA Pa_03522 and Ps_02062), suggesting modulation of genes involved in inter-species interactions.

Taken together, our meta-transcriptomic analysis shows that the three bacterial strains undergo substantial transcriptional re-programming in response to ternary inter-species interactions and highlight the emergence of microbial functions that were not identified in mono- and binary co-cultures.

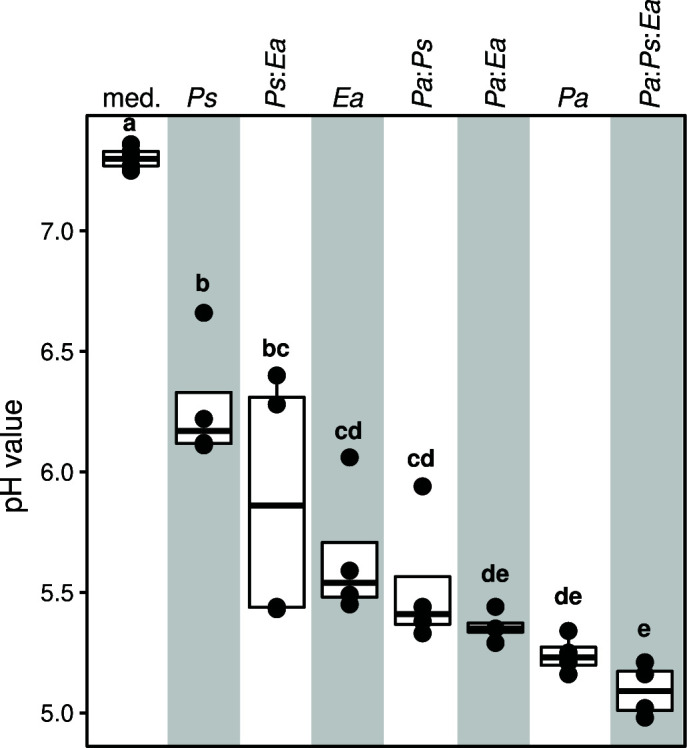

Finally, to test if co-culturing influenced the external environment, we measured the pH at the end of bacterial growth. We detected pH reductions in all growth conditions (Fig. 6). Mono-cultures of Ps, Ea, and Pa led to a reducing pH on average from 7.30 (media control) to 6.27, 5.64, and 5.24, respectively (Fig. 6). We noted that any binary co-culture with Pa (i.e., Pa:Ea and Pa:Ps) led to more acidic medium than the binary co-culture of Ps and Ea (Fig. 6). Notably, the pH of the ternary co-culture was even more acidic than any of the binary or mono-culture conditions (Fig. 6). Thus, while the growth of all three strains alters the pH of the milieu, the ternary co-culture of Ea, Pa, and Ps strongly reduced the pH, pointing to potential interactive effects of these strains in co-culture, and another emergent property of the ternary growth conditions.

Fig 6.

Ternary co-culture leads to strong acidification of the pH. The boxplots show pH values in the control (no bacterial inoculation), the mono- and the co-cultures. Inoculation of any of Ea, Pa, Ps or their combinations significantly alters the pH of the growth milieu. Ternary co-culture of the bacteria shifts the pH to more acidic than any binary co-culture or mono-culture. Color denotes growth condition, and letters show significance in the P-value (P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Conover’s post hoc test).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the co-inoculation of two members of the flower microbiota, Pseudomonas CT-1059 and Pantoea CT-1039, reduced fire blight infection caused by Ea in experimental orchards (Fig. 1B). These results corroborate previous finding (15) and further point to the potential use of these strains as probiotic inoculants to control fire blight. Several bacterial strains that control fire blight have been previously identified and used, such as Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 (23), Bacillus subtilis QST713 (24), Pantoea agglomerans E325 (25), and Pantoea vagans (26), to cite only a few. The mechanism by which the above-mentioned biocontrol bacteria protect the plant from the pathogen is attributed to their ability to reduce or suppress the growth of E. amylovora on the stigma through antibiosis or competing for nutrients and space (11, 27, 28). In contrast, our study did not provide evidence of competitive niche exclusion of E. amylovora by the commensal strains. The abundance of the pathogen remained relatively high on the flower stigma, fluorescence micrographs showed that E. amylovora co-localize at the micro-scale with both flower commensals, and all three strains co-existed in the same culture media (Fig. 3B). Therefore, these bacterial strains do not seem to inhibit the establishment of E. amylovora populations; instead, these results indicate the ecological co-existence among the three bacteria on flowers.

Nevertheless, we did observe smaller Ea populations both through amsC copy numbers (Fig. 2A) and 16S rRNA gene/transcript sequencing (Fig. 2B and C) in the presence of the bacterial strains, suggesting potentially reduced population sizes of E. amylovora. Our findings cannot rule out the possibility that these flower commensal bacteria restrict the population size of the pathogen below a threshold that impairs its pathogenicity or infectivity. Future work will help us test this hypothesis and reveal how Pseudomonas and Pantoea alter E. amylovora population on the stigma of apple flowers.

As the commensal bacteria did not appear to significantly hinder the growth of E. amylovora, either in vivo on the stigma of apple flowers (Fig. 2A) or in vitro in synthetic media (Fig. 3B), our next objective was to investigate whether these strains influence the activity of the pathogen. We postulated that the presence of the commensal flower bacteria affects the activity of E. amylovora and their interactions lead to emergent properties translated by gene expression. An emergent property is defined here by the emergence of functions or phenotypes not predictable from the constituent part of the community when observed in isolation (6, 29). The meta-transcriptome study revealed changes in the transcription profiles of all three bacteria when in ternary co-culture. These expression patterns were unique compared to when they were grown alone, or even in binary co-cultures (Fig. 4A, C, and E). Characterization of DEGs identified in ternary interactions revealed that these genes covered various microbial functions and processes (Fig. 5B; Table S2). Importantly, several of the DEGs encoded for molecular functions that mediate bacterial inter-species interactions, ABC transporters, defense mechanisms, or stress response (Fig. S1; Table S1). These findings indicate that the two flower-associated bacteria and the floral pathogen undergo substantial re-programming in gene expression under ternary interactions, and the emergence of microbial functions is non-additive to the binary interactions.

It is reasonable to hypothesize that the transcriptional re-programming of E. amylovora during ternary co-culture (146 DEG/3,674 total genes, or 4% total genes) leads to phenotypical changes in the pathogen. From our analysis, we identified two genes that may play an important role in the virulence of E. amylovora or related bacteria. First, RcsB (Table S1, Ea_02226, log2FC = 1.53, P-value = 3.71E-05) is a response regulator of the RcsBCD phosphorelay system that is a major regulator of the biosynthesis of exopolysaccharide and amylovoran in E. amylovora (30). Amylovoran is known to be critical for biofilm formation in E. amylovora (31) and has been suggested to mediate a protective role against plant defense during infection (7). Second, SlyA (Ea_01648, log2FC = 2.45, P-value = 1.54E-11) is a virulence regulator of the type III secretion system in closely related bacterial plant pathogen Dickeya dadantii (20). The altered expression of this regulator gene may impact the ability of E. amylovora to infect its host. Furthermore, to cause an effective infection, E. amylovora is required to migrate to the base of the flower that harbors natural openings. For this, motility is required. In ternary co-culture, the expression of several motility-related genes is suppressed in E. amylovora (e.g., fliA Ea_01648, log2FC = −1.75, P-value = 0.03). Furthermore, up-regulation of several genes involved in stress responses and antimicrobial tolerance (e.g. multidrug efflux pump gene acrZ, Ea_01184, log2FC = 2.23, P-value = 2.15E-06) was observed during ternary co-culture. These results suggest that the fire blight pathogen may be under stress when interacting with the commensal flower bacteria. Although we could not attribute the suppressed disease infection phenotype to DEGs, the transcriptomic re-programming of Ea of multiple DGEs during the ternary interaction could be one explanation for the reduced infection upon interactions with Ps and Pa. Regarding the commensal bacteria Ps and Pa, DEGs with various functions related to microbe-microbe interactions, such as quorum sensing, biofilm formation, toxin production, and nutrient acquisition, were identified in ternary interaction but not in mono- or binary interactions (Table S1), suggesting enhanced microbe-microbe interaction activities during ternary interaction, which suggests these bacteria also modulate their behavior in the presence of Ea.

Our analysis of the gene expression data pointed to metabolic or physiological changes in E. amylovora indicative of adaptations to an acidified environment and general stress response in both commensal bacterial strains (Table S1). Pantoea was the strongest driver of pH reduction, and ternary co-culture led to the strongest pH acidification of the growth milieu (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that acidification has previously been reported as a mechanism by which biological control strains may reduce Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity. Pusey and colleagues have shown that Pantoea agglomerans strain E325 acidifies the pH of the flowers to a point that could deplete the growth of the fire blight pathogen (25). Furthermore, Pester and colleagues have shown that reducing the pH of apple flowers leads to the down expression of virulence genes in E. amylovora (32). Similar dynamics have been described for other pathogen-host systems. For instance, the bumble bee symbiont Lactobacillus bombicola was shown to inhibit the pathogen Crithidia bombi by reducing the pH in the gut (14). These studies highlight the role of environmental pH as a potential property that modulates microbial interactions and potentially pathogen behavior (33, 34). It remains to be tested whether co-inoculation of Pseudomonas and Pantoea could lead to down-regulation of pathogenicity genes in E. amylovora and whether this is a direct consequence of acidified habitat on the apple flower.

In conclusion, this study showed that co-inoculating two flower-associated bacteria protects the host plant from the fire blight disease. These two bacterial strains did not competitively exclude E. amylovora from the stigma habitat, but bacterial inter-species interactions led to alterations in the activities of all three members. Ternary interactions between the bacteria led to a strong alteration of the pH beyond what was expected from any strain alone and to the emergence of new gene expression patterns. Our study emphasizes the role of emergent microbial properties that are not predictable from binary interactions. We propose further exploring inter-species interactions between microbial consortia and plant pathogens to mediate disease resistance. As the outcome of inter-species interactions is inherently complex, microbial virulence may be an emergent microbial propriety itself (35). In this respect, deciphering these interactions requires empirical testing and needs to be understood in their ecological context. Exploring the properties of microbiota commensals offers an alternative and sustainable practice to manage plant diseases and promote host health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study were Erwinia amylovora strain 110, Pseudomonas CT-1059 (field co-inoculations and in vitro co-culture assay), Pantoea CT-1039 (field co-inoculations, in vitro co-culture assay and microscopy imaging), and Pseudomonas CT1181. All strains were cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium at 28°C overnight with shaking (250 rpm). Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations when required: chloramphenicol, 30 µg/mL; kanamycin, 50 µg/mL; ampicillin, 100 µg/mL; spectinomycin, 50 µg/mL.

Bacterial strain co-inoculations in the field and fire blight scoring

Field co-inoculations were performed on 30-year-old apple tree cultivar “Red Delicious” in May 2021 at the Lockwood Farm, Hamden, CT (41.406 N, 72.906 W). Thirty-six apple trees were randomly grouped into nine treatment groups with four tree replicates per treatment and organized in a randomized complete block design. Pantoea CT-1039 and Pseudomonas CT-1059 were cultured in LB overnight. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 min, adjusted to ca. 5 × 107 CFU/mL in water, and then sprayed to apple flowers approximately 2 L per tree. Treatments were applied twice, at 60% bloom (29 April 2021) and at 80% bloom (30 April 2021), using a motorized Solo sprayer (3.8 L per tree). E. amylovora was inoculated at 100% bloom (1 May 2021) with the concentration of 5 × 106 CFU/mL. Streptomycin (Firewall 50, at 100 ppm) was applied 2 h post Ea inoculation (1 May 2021). For Pa:Ps co-inoculation, the bacteria were mixed at equal volume and applied to the same dosage as single strain treatments. Fire blight disease infection was rated 3 weeks after the inoculation of E. amylovora. Disease incidence was calculated as percentage of symptomatic flower clusters from the pool of treated flower clusters of each tree per treatment.

Flower sampling for E. amylovora quantification

From the field co-inoculation experiments conducted May 2021, we collected flower samples for DNA and RNA extractions. DNA from the single flower was used to quantify E. amylovora, and to profile microbial communities using 16S rRNA gene, whereas RNA from 20 flowers were used to profile the flower microbiota using 16S rRNA gene transcripts. Flowers were harvested after 2 days post-inoculation of E. amylovora (3 May). For DNA isolation, 10 individual flowers for each treatment were harvested. Four to five stigmas from each flower were dissected, placed into micro-centrifuge tube using sterile scissors, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and were treated as a single biological replicate. For RNA extraction, stigmas were collected from 20 flowers, placed into micro-centrifuge tube, snap frozen, and treated as one biological replicate. Samples were stored at −80°C until further processing.

DNA extraction from apple stigma

Deep-frozen stigma samples were retrieved from −80°C and 200 µL of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) + 0.001% Silvet L77 (PlantMedia, Dublin, OH) were added to the tube. To retrieve epiphytic bacteria from the stigma surface, samples were sonicated for 5 min in a water batch at room temperature followed by full-speed vortex for 30 s. Stigma tissues were removed from the tube and DNA was extracted from the solution using DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions, except the following modifications. Cell suspensions were treated with 36 µL of lysozyme (10 mg/mL in 1× PBS, AmericanBio, Natick, MA) for 30 min at 37°C followed by 20 µL of proteinase K (>600 U/mL, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 5 µL of RNase A/T1 (2 mg/mL / 5,000 U/mL, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 5 min at room temperature. DNA was eluted in 35 µL of nuclease-free water (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

RNA extraction from apple stigma

Deep-frozen stigma samples were retrieved from −80°C and 200 µL of 1× PBS (pH 7.4, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) + 0.001% Silvet L77 (PlantMedia, Dublin, OH) + beta-mercaptoethanol (% vol/vol) were added to the tube. Epiphytic bacteria were detached by combining water bath sonication for 5 min and followed by full-speed vortex for 30 s as described in the DNA extraction protocol. Stigma was removed from the tube, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy PowerLyzer Tissue & Cells Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Yield and quality were determined using QuBit and Agilent Bioanalyzer, respectively. Eluted RNA was depleted from ribosomal RNA using NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (Bacteria, New England Biolabs, MA), then used as a template to generate cDNA using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (England Biolabs, Ipwich, MA). The resulting cDNA was assessed with a high-sensitivity Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Size profiles of cDNA fragments were consistent across samples.

Quantification of E. amylovora by qPCR

The absolute abundance of E. amylovora in each stigma sample was quantified using a previously described method (36). In brief, the DNA copy number of E. amylovora was quantified by determining the cycle threshold (CT) value of the E. amylovora-specific gene amsC. qPCR was performed using SsoAdvanced universal SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR, as described previously (37). The CT values for a 1/10 dilution series of known amsC gene copies of E. amylovora chromosomal DNA were determined to make a standard curve for calculating copy numbers in stigma samples.

Confocal microscopy observation of microbial colonization on stigma

Pseudomonas CT-1181, Pantoea CT-1039 constitutively expressing mCherry (red), and mTurquoise (turquoise) FP were generated using miniTn7-pURR25DK-3xmCherry and miniTn7-pURR25DK-mTurquoise, respectively (38). Using tri-parental mating including helper strain Escherichia coli RHO3 carrying pTNS, mCherry, and mTurquoise were inserted at unique site attTn7 in the genome of recipient Pseudomonas CT-1181 and Pantoea CT-1093, respectively (39–41). Derivative E. amylovora 1189 expressing green fluorescent protein carried a gfp (green) under the control of nptII promoter integrated into the chromosome. Bacterial cells were cultured in LB overnight at 28°C shaking (250 rpm). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and adjusted to 107 CFUs/mL before spray-inoculating onto the stigma of 3-year-old trees of the cultivar “Gala.” Trees were potted in separate containers. Inoculated trees were kept in a plant growth chamber (25°C, 80% relative humidity, and 16-h cycle of 350 µmol light intensity). Pseudomonas CT-1181 expressing mCherry FP and Pantoea CT-1039 expressing mTurquoise FP were inoculated on stigma when petals first open, and E. amylovora 1189 expressing green FP was inoculated 1 day thereafter. Stigmas were collected 2 days post the inoculation of E. amylovora. Fluorescent green (484 nm/507 nm), mCherry (587 nm/610 nm), and mTurquoise (434 nm/474 nm) signals were observed with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with four laser channels (405 nm, multiline Argon, 561 nm and 633 nm) and two HyD detectors. Images were captured with Leica LAS AF software and overlayed using Leica LAS-X software.

Profiling the microbiota of apple flower stigma

To study the relative abundance of E. amylovora, Pseudomonas, and Pantoea on the apple flowers, we profiled the flower microbiota using a previously described protocol (3, 35). Briefly, the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primer set, 515F and 806R in triplicate from either isolated DNA or generated cDNA. PNA clams were added to PCR mixture to reduce the amplification of apple plastids and mitochondrial sequences (3). PCR products from the triplicates were pooled, purified, and normalized using SequalPrep kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Normalized amplicons were pooled together and submitted for sequencing using MiSeq v2.2.0 platform (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) at Yale Center for genome analysis.

Sequences processing and community analysis

MiSeq forward and reverse reads were joined and demultiplexed using qiime2 pipeline (q2cli v2021.4.0) (42). PhiX and chimeric sequences were filtered out using qiime2-DADA2 (43). Scripts used for sequence processing are available under https://github.com/hmamine/PPE/tree/main/reads_processing and raw sequencing reads are accessible at sequence read archive accession number PRJNA966219. Taxonomic classification of reads was performed using qiime2 feature classifier (q2cli v2021.4.0) (42) and on scikit-learn naive Bayes trained classifier (44). The classifier was trained on 16S rRNA sequences (Green Genes 13.8.99) using the primer set 515F/806R. Reads were assigned to ASVs with 100% sequence identity. All R scripts used in this study are indicated at https://github.com/hmamine/PPE.

In vitro mono- and co-culture growth assays

For mono-culture assay, cells from 5 mL of an overnight culture of E. amylovora strain 110, Pseudomonas CT-1059, or Pantoea CT-1039 were pelleted, washed, and re-suspended in equal volume of 0.5× PBS. Cell concentration was adjusted to an initial Optical Density 600nm (OD600) of 0.08 in partial stigma-mimicking media. Cells were incubated at 28°C for 6 h with shaking. For co-culture assays, bacterial cell suspensions were prepared similarly to mono-culture growth assay. Mono-cultures of each strain were adjusted to the same density and mixed in equal volume to produce an initial OD600 of 0.08. The population of each strain and the pH of the culture were determined after 7 h of growth. The colony-forming units of each isolate were determined by plating on an LB agar medium with selective antibiotics. E. amylovora and Pseudomonas CT-1059 were resistant to rifampicin and streptomycin, respectively. Pantoea CT-1039 was sensitive to both aforementioned antibiotics. Thus, Pa counts were determined by counting cells resistant to both antibiotics and subtracting those counts from cells resistant to either antibiotic independently.

RNA extraction in vitro co-culture assays

Bacterial cells were collected from mono- and co-cultures after 6 h of growth at 28°C in a partial stigma-mimicking medium. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy PowerLyzer Tissue & Cells Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was eluted in 50 µL nuclease-free water. Quantity and quality control of the RNA was assessed by using Qubit RNA Broad-Range Assay (Invitrogen) and with RNA ScreenTape analysis on Agilent TapeStation Bioanalyzer. Before Illumina library preparation, rRNA depletion was conducted using the NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (Bacteria, New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Then, DNA removal coupled with cDNA synthesis was conducted using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. DNA quantity was checked using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Library sequencing was conducted on an Illumina NovaSeq platform through services provided by the Yale Center for Genome Analysis.

Transcriptome analysis

Adapter removal and sequence trimming were conducted using Trimmomatic (45). The full genome of each of E. amylovora 110, Pseudomonas sp. strain CT-1059, and Pantoea sp. strain CT-1039, available in the GenBank Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA693803, was concatenated to build a unique index for mapping the reads. The index was generated using Salmon (v1.10) (46). Reads were quantified against the generated index using the alignment tool Salmon (v1.10). Differential expressed genes were identified using DESeq2 R package (47) using normalized reads indicated by transcripts per million. Genomes were annotated using Prokka annotation tool (v.1.14) (48) and the Functional Annotation and Classification of Proteins of Prokaryotes tool (19). The enrichment analysis was computed using the Functional Analysis and Gene Set Enrichment for Prokaryotes tool (19). All scripts are available at https://github.com/hmamine/PPE/tree/main/metatrans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Brian Kvitko (Univ. of Georgia) for providing miniTn7-pURR25DK-3xmCherry and miniTn7-pURR25DK-mTurquoise, Yale Center for Genome Analysis, for providing support during sequencing and high-performance computing center at the University of Connecticut.

This study was funded by the USDA-NIFA grants: 2023-51181-41319, 2023-51300-40727, 2020-67013-31794, CAES Board of Control Research Award (2022), and USDA-Specialty Crop Block Grant (SCBG) through the Department of Agriculture, State of Connecticut.

Contributor Information

Blaire Steven, Email: blaire.steven@ct.gov.

Quan Zeng, Email: quan.zeng@ct.gov.

Anne K. Vidaver, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

All sequencing reads used in this study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive BioProject number PRJNA966219. All R scripts used to generate the figures could be accessed at https://github.com/hmamine/PPE.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00213-24.

Differentially expressed genes.

Genes that were differentially expressed in Erwinia amylovora, Pantoea CT-1039, and Pseudomonas CT-1059 in ternary co-culture.

GO term enrichment analysis.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vannette RL. 2020. The floral microbiome: plant, pollinator, and microbial perspectives. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 51:363–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-013401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shade A, McManus PS, Handelsman J. 2013. Unexpected diversity during community succession in the apple flower microbiome. mBio 4:e00602-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00602-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steven B, Huntley RB, Zeng Q. 2018. The influence of flower anatomy and apple cultivar on the apple flower phytobiome. Phytobiomes J 2:171–179. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-03-18-0015-R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burgess EC, Schaeffer RN. 2022. The floral microbiome and its management in agroecosystems: a perspective. J Agric Food Chem 70:9819–9825. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c02037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vannier N, Agler M, Hacquard S. 2019. Microbiota-mediated disease resistance in plants. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007740. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van den Berg NI, Machado D, Santos S, Rocha I, Chacón J, Harcombe W, Mitri S, Patil KR. 2022. Ecological modelling approaches for predicting emergent properties in microbial communities. Nat Ecol Evol 6:855–865. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01746-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kharadi RR, Schachterle JK, Yuan X, Castiblanco LF, Peng J, Slack SM, Zeng Q, Sundin GW. 2021. Genetic dissection of the Erwinia amylovora disease cycle. Annu Rev Phytopathol 59:191–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-095540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malnoy M, Martens S, Norelli JL, Barny M-A, Sundin GW, Smits THM, Duffy B. 2012. Fire blight: applied genomic insights of the pathogen and host. Annu Rev Phytopathol 50:475–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stockwell VO, Duffy B. 2012. Use of antibiotics in plant agriculture. Rev Sci Tech 31:199–210. doi: 10.20506/rst.31.1.2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vanshree CR, Singhal M, Sexena M, Sankhla MS, Parihar K, Jadhav EB, Awasthi KK, Yadav CS. 2022. Chapter 11 - microbes as biocontrol agent: from crop protection till food security, p 215–237. In Samuel J, Kumar A, Singh J (ed), Relationship between microbes and the environment for sustainable ecosystem services. Vol. 1. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright SAI, Zumoff CH, Schneider L, Beer SV.. 2001. Pantoea agglomerans strain EH318 produces two antibiotics that inhibit Erwinia amylovora in vitro. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smits THM, Rezzonico F, Kamber T, Blom J, Goesmann A, Ishimaru CA, Frey JE, Stockwell VO, Duffy B. 2011. Metabolic versatility and antibacterial metabolite biosynthesis are distinguishing genomic features of the fire blight antagonist Pantoea vagans C9-1. PLoS One 6:e22247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park J, Kim B, Song S, Lee YW, Roh E. 2022. Isolation of nine bacteriophages shown effective against Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Pathol J 38:248–253. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.NT.11.2021.0172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palmer-Young EC, Raffel TR, McFrederick QS. 2019. pH-mediated inhibition of a bumble bee parasite by an intestinal symbiont. Parasitology 146:380–388. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018001555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cui Z, Huntley RB, Schultes NP, Steven B, Zeng Q. 2021. Inoculation of stigma-colonizing microbes to apple stigmas alters microbiome structure and reduces the occurrence of fire blight disease. Phytobiomes J 5:156–165. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-04-20-0035-R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lawrence Pusey P, Rudell DR, Curry EA, Mattheis JP. 2008. Characterization of stigma exudates in aqueous extracts from apple and pear flowers. horts 43:1471–1478. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.43.5.1471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gloor GB, Macklaim JM, Pawlowsky-Glahn V, Egozcue JJ. 2017. Microbiome datasets are compositional: and this is not optional. Front Microbiol 8:2224. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. 1997. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Jong A, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2022. FUNAGE-Pro: comprehensive web server for gene set enrichment analysis of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research 50:W330–W336. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zou L, Zeng Q, Lin H, Gyaneshwar P, Chen G, Yang C-H. 2012. SlyA regulates type III secretion system (T3SS) genes in parallel with the T3SS master regulator HrpL in Dickeya dadantii 3937. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2888–2895. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07021-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carter MQ, Parker CT, Louie JW, Huynh S, Fagerquist CK, Mandrell RE. 2012. RcsB contributes to the distinct stress fitness among Escherichia coli O157:H7 curli variants of the 1993 hamburger-associated outbreak strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7706–7719. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02157-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higashi K, Ishigure H, Demizu R, Uemura T, Nishino K, Yamaguchi A, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. 2008. Identification of a spermidine excretion protein complex (MdtJI) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190:872–878. doi: 10.1128/JB.01505-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilson M, Lindow SE. 1993. Interactions between the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 and Erwinia amylovora in pear blossoms . Phytopathology 83:117. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sundin GW, Werner NA, Yoder KS, Aldwinckle HS. 2009. Field evaluation of biological control of fire blight in the eastern United States. Plant Dis 93:386–394. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-93-4-0386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pusey PL, Stockwell VO, Rudell DR. 2008. Antibiosis and acidification by Pantoea agglomerans strain E325 may contribute to suppression of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 98:1136–1143. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-10-1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stockwell VO, Johnson KB, Sugar D, Loper JE. 2010. Control of fire blight by Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 and Pantoea vagans C9-1 applied as single strains and mixed inocula. Phytopathology 100:1330–1339. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-03-10-0097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dagher F, Nickzad A, Zheng J, Hoffmann M, Déziel E. 2021. Characterization of the biocontrol activity of three bacterial isolates against the phytopathogen Erwinia amylovora. Microbiologyopen 10:e1202. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Niu B, Vater J, Rueckert C, Blom J, Lehmann M, Ru J-J, Chen X-H, Wang Q, Borriss R. 2013. Polymyxin P is the active principle in suppressing phytopathogenic Erwinia spp. by the biocontrol rhizobacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa M-1. BMC Microbiol 13:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salt GW. 1979. A comment on the use of the term emergent properties. Am Nat 113:145–148. doi: 10.1086/283370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang D, Qi M, Calla B, Korban SS, Clough SJ, Cock PJA, Sundin GW, Toth I, Zhao Y. 2012. Genome-wide identification of genes regulated by the Rcs phosphorelay system in Erwinia amylovora. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25:6–17. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-11-0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koczan JM, McGrath MJ, Zhao Y, Sundin GW. 2009. Contribution of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharides amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: implications in pathogenicity. Phytopathology 99:1237–1244. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-11-1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pester D, Milčevičová R, Schaffer J, Wilhelm E, Blümel S. 2012. Erwinia amylovora expresses fast and simultaneously hrp/dsp virulence genes during flower infection on apple trees. PLoS One 7:e32583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ratzke C, Gore J. 2018. Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH can drive bacterial interactions. PLoS Biol 16:e2004248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aranda-Díaz A, Obadia B, Dodge R, Thomsen T, Hallberg ZF, Güvener ZT, Ludington WB, Huang KC. 2020. Bacterial interspecies interactions modulate pH-mediated antibiotic tolerance. Elife 9:e51493. doi: 10.7554/eLife.51493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casadevall A, Fang FC, Pirofski L. 2011. Microbial virulence as an emergent property: consequences and opportunities. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002136. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pirc M, Ravnikar M, Tomlinson J, Dreo T. 2009. Improved fireblight diagnostics using quantitative real-time PCR detection of Erwinia amylovora chromosomal DNA . Plant Pathology 58:872–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02083.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cui Z, Huntley RB, Zeng Q, Steven B. 2021. Temporal and spatial dynamics in the apple flower microbiome in the presence of the phytopathogen Erwinia amylovora. ISME J 15:318–329. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00784-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baltrus DA, Feng Q, Kvitko BH. 2022. Genome context influences evolutionary flexibility of nearly identical type III effectors in two phytopathogenic pseudomonads. Front Microbiol 13:826365. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.826365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bao Y, Lies DP, Fu H, Roberts GP. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167–168. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90604-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Teal TK, Lies DP, Wold BJ, Newman DK. 2006. Spatiometabolic stratification of Shewanella oneidensis biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:7324–7330. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01163-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lambertsen L, Sternberg C, Molin S. 2004. Mini-Tn7 transposons for site-specific tagging of bacteria with fluorescent proteins. Environ Microbiol 6:726–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00605.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, et al. 2019. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. 2016. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, Dubourg V, et al. 2011. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. null. J Mach Learn Res 12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. 2017. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Differentially expressed genes.

Genes that were differentially expressed in Erwinia amylovora, Pantoea CT-1039, and Pseudomonas CT-1059 in ternary co-culture.

GO term enrichment analysis.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis.

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing reads used in this study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive BioProject number PRJNA966219. All R scripts used to generate the figures could be accessed at https://github.com/hmamine/PPE.