Abstract

Schools support teachers in their professional learning, just as teachers support students in their learning. To accomplish this, schools can provide support systems that enhance teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and instructional skills. This study examined the impact of two district-provided supports (curriculum and professional development) on sexual health instruction among middle and high school health education teachers. Data were abstracted and analyzed using inductive coding from 24 teacher interviews (2015–2016). Findings illustrate outcomes from both curriculum and PD on teachers’ self-reported knowledge, comfort, and skills. The district-provided supports appeared to contribute to improved teachers’ self-efficacy in delivering sexual health education.

Keywords: Professional development, Curriculum, Sexual health education, STD/HIV prevention, Adolescent pregnancy prevention, Sexual health promotion

1. Introduction

It is said in every classroom of 20 students, there are 21 learners. Teachers, while considered responsible for facilitating students’ learning and achievement (Avalos, 2011; Darling-Hammond, Wei, Andree, Richardson, & Orphanos, 2009; Stronge, Ward, & Grant, 2011), are also active learners who refine their knowledge and skills daily (Darling-Hammond, Hyler, & Gardner, 2017). Schools can improve the instructional capacity of teachers through the use of professional learning and development supports that are innovative, tailored, and sustained. Such supports not only lead to improvements in the personal learning and teaching practices of teachers, but also contribute to improved student learning over time (Darling-Hammond et al., 2009, 2017; Opfer and Pedder, 2011; Stronge et al., 2011).

Just as other academic contents areas (e.g., mathematics or science education) specify competencies and instructional skills needed by teachers (National Science Teacher Association, 2012; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2012), school health and sexual health education also describe content knowledge and pedagogical skills to support effective instruction (American Association for Health Education, 2008; Future for Sex Education, 2011; The Society for Health and Physical Educators, 2018). Such knowledge and skills form the basis of teachers’ professional learning and development needs, presenting unique opportunities for ongoing district-provided support.

2. Literature review

Through implementing appropriate health education, schools can equip students with the essential knowledge and skills to make healthy decisions. Within health education, sexual health education has been associated with delayed initiation of sexual intercourse, reductions in sexual activity and number of sexual partners, and increases in condom or contraceptive use (Chin et al., 2012; Goesling, Colman, Trenholm; Terzian, & Moore, 2014; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007; Ma, Fisher, & Kuller, 2014; Tortolero et al., 2010); these behaviors, in turn, help students reduce their risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and unintended pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). To achieve these results, however, health education must be implemented well.

Highly qualified and trained teachers are necessary to help youth gain the functional information and skills to become healthy and productive adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Research suggests the classroom teacher largely influences whether sexual health education results in positive effects on student knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral outcomes (Murray 2019; LaChausse, Clark, & Chapple, 2014; Vamous & Zhou, 2007; Cohen, Sears, Byers, & Weaver, 2004). Thus, one primary characteristic of effective sexual health education are the highly trained educators who are provided ongoing training, monitoring, and supervision (LaChausse et al., 2014).

Teachers’ acquisition of knowledge and skills to effectively deliver sexual health education can be strengthened through professional development (Clayton, Brener, Barrios, Jayne, & Everett Jones, 2018; Brener, McManus, Wechsler, & Kann, 2013; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009). Professional development (PD) refers to a systematic process for strengthening professional knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, & Smith-Jentsch, 2012). PD can be voluntary or mandatory, individual or collaborative, and formal or informal (Desimone, 2011), and seeks to improve teacher practices and student outcomes (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Among school health education broadly, teachers who engaged in PD demonstrated significantly higher scores on self-efficacy expectations, believed more strongly they could teach a variety of health topics, and increased instructional time delivering health education (Telljohann, Everett, Durgin, & Price, 1996). Data from a national study of school health policies and practices indicate lead health education teachers who received PD included a large number of general health education topics in their instruction than colleagues who did not receive PD (Jones, Brener, & McManus, 2004).

Research on the effectiveness of PD for sexual health education specifically is nascent but follows similar trends. Research by LaChausse et al. (2014) suggests credentialed teachers (i.e., held health education certifications) who attended PD training reported greater self-efficacy and higher curriculum fidelity in teaching sex-related information than peers who did not. Similarly, using data from a nationally representative study, Clayton et al. (2018) found a robust relationship between teachers’ receipt of PD and an increase in the average number of sexual health topics taught and the overall time devoted to the content area. Training for teachers and school staff is one of the most impactful school-based practices to support the health of all youth, but particularly the targeted needs of sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) (Kosciw, Palmer, Kull, & Greytak, 2013; Swanson & Gettinger, 2016). Teachers must be adequately trained to facilitate learning opportunities targeting the essential knowledge and skills youth need to prevent HIV, STDs, and unintended pregnancy. Together, this evidence suggests that PD helps teachers improve their instructional practices and increases their ability to meet the diverse learning and health needs of all youth, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity (Clayton et al., 2018; LaChausse et al., 2014; Center for Public Education, 2013; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Swanson & Gettinger, 2016; Kosciw et al., 2013).

Beyond providing PD, schools can also use evidence-based strategies such as the provision of instructional materials (i.e., curriculum) to strengthen instructional practices. Provision of strong curriculum for classroom use can ensure that teachers have access to accurate and age-appropriate content as well as diverse teaching and learning strategies designed to reinforce relevant knowledge and skills for students. When schools provide teachers with necessary curriculum resources, instructional practices and delivery become more effective and strengthen the likelihood of better student performance (Opfer & Pedder, 2011; Stronge et al., 2011; Avalos, 2011). Preston (2019) found that sexuality education teachers triangulated content from multiple sources to strengthen their teaching practices. Teachers’ reported curriculum delivery was shaped not only by personal knowledge and comfort, but also training on specific curriculum elements (e.g., lesson activities) and formal and informal school district board policies. Collectively, teachers acknowledged that the school district’s provided curriculum and their personal characteristics and capacity (Preston, 2019) influenced their abilities to create environments where students felt rapport, safety, and openness to discuss sexual health.

Although understanding of the professional learning needs of health and sexual health education teachers has grown significantly over the last several years (Telljohann et al., 1996; Clayton et al., 2018; Eisenberg, Madsen, Opliphant, Sieving, & Resnick, 2010; Preston, 2019), additional evidence is needed. This study describes salient characteristics of school district-provided supports—curriculum and PD—and their relationship to teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills for implementing sexual health education in middle and high schools. This study had two primary aims: (a) understand a multi-component district-provided support framework using an adapted curriculum and PD activities (i.e., in-person training and personalized coaching) for health education teachers, and (b) examine the influence of this support framework on teachers’ self-reported knowledge, comfort, and skills in delivering sexual health education.

3. Methodology and methods

The research design for this study used thematic content analysis to explore in-depth interviews with teachers delivering sexual health education. Authors considered elements of a critical constructivist framework in the data analysis process (Guba & Lincoln, 1994) to better understand the evolution of teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills in delivering sexual health education in middle and high school following participation in tailored instructional supports. Specifically, authors sought to understand how co-creation of knowledge and skills (Guba & Lincoln, 1994), constructed through shared learning experiences and professional development coaching, contributed to changes in teachers’ self-reported comfort and confidence with an adapted curriculum. The participating school district provided two unique supports to study participants: an adapted sexual health education curriculum and PD via in-person trainings and personalized coaching, believed to improve comfort and confidence in delivering lessons to students. The instructional supports provided by the school district served as the implementation frame and helped authors understand the environments in which individual participant’s contextualization of curriculum and application of new teaching methods was learned; key characteristics of critical inquiry in qualitative research (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Through the process of engaging with the district-provided supports, participants critically analyzed sexual health lessons and implemented instruction bound by classroom-specific knowledge and approaches to support unique student learning. Acknowledging the interactive and experiential nature of the district-provided supports between teachers, and students receiving the sexual health education lessons, authors used a critical, exploratory framework to understanding teachers’ application of new knowledge and skills to the unique contexts of their classroom settings, improving comfort and confidence over time.

3.1. District-provided support framework

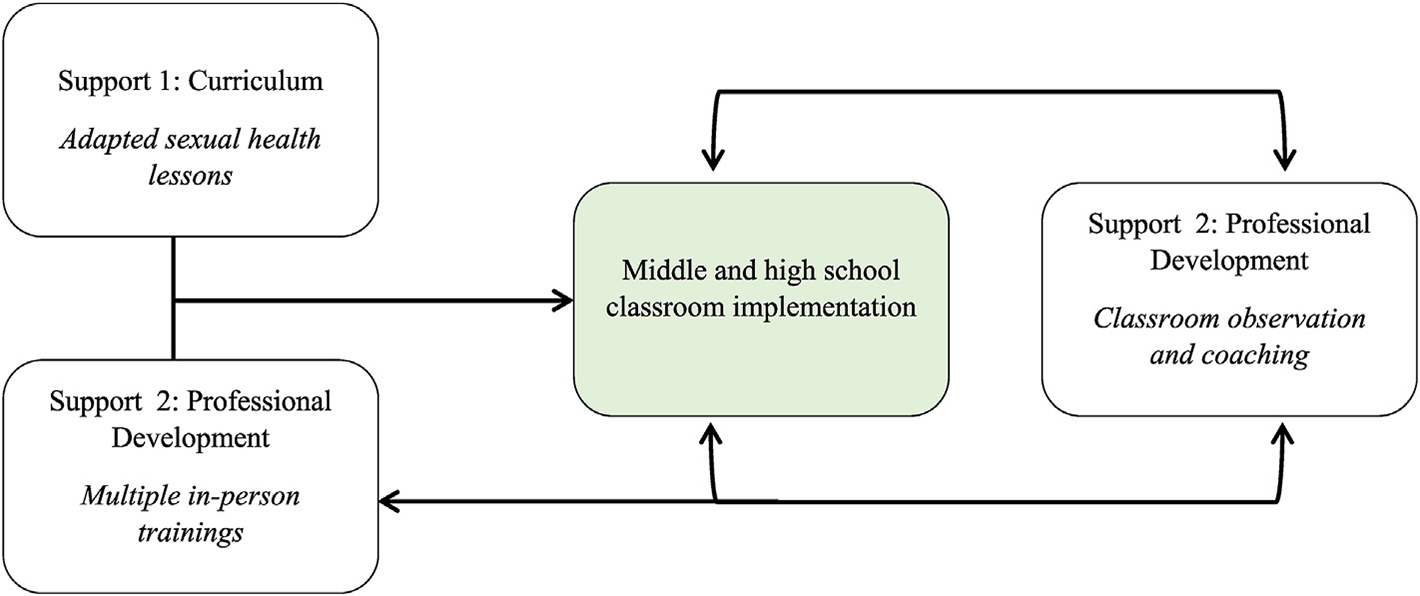

To ensure teachers are prepared to deliver effective classroom-based instruction, schools should provide, at a minimum, appropriate instructional materials and adequate PD to meet teachers’ needs. The school district in this study, a large, urban district in the central, southern United States, provided teachers with an adapted curriculum (including sexual health education lessons) and supplemental student materials as well as ongoing PD (e.g., in-person training, classroom observations and personalized coaching) (see Fig. 1). These element reinforced teachers’ learning across multiple exposures to curriculum, in-person trainings, and consistent feedback and coaching. The bidirectional relationships suggest that as teachers were exposed to curriculum-specific lesson and training their classroom implementation may have been enhanced. As district staff provided personalized coaching using feedback from classroom observations, teachers’ implementation could have been influenced. Moreover, feedback gathered through observation and coaching provided necessary insights to strengthen in-person trainings, using real-time implementation data. This system of feedback illustrates the connectedness of the district-provided supports that were hypothesized to improved delivery of the sexual health educations lessons by teachers in the study.

Fig. 1.

Proposed relationship among district-provided supports to enhance sexual health education.

Adapted curriculum.

Middle school (MS) and high school (HS) teachers taught health education using an adapted version of a packaged comprehensive health education curriculum, HealthSmart (ETR, 2019a). The aim of HealthSmart is to promote the healthy growth and development of youth and give them the knowledge and skills to make healthy choices and establish life-long healthy behaviors (ETR, 2019a). Prior to initiation of our study, the school district underwent a systematic curriculum analysis process using CDC’s Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool [HECAT] and the Tool to Assess the Characteristics of Effective Sex and STD/HIV Education Programs (TAC) to identity essential knowledge and skill expectations aligned to desired behavior health outcomes of interest (ETR, 2014; CDC, 2012). This process resulted in explicit review of comprehensive HIV/STDs, and pregnancy prevention-related lessons within HealthSmart (ETR, 2019a). HealthSmart (ETR, 2019a) is designed to avoid making assumptions about sexual orientation or gender identity and to ensure all students feel represented in the content and skill-building activities (ETR, 2019b), resulting in enhanced inclusivity and appropriateness for SGMY. School district staff determined appropriateness and feasibility of a sub-set of sexual health education lessons which aligned to specific health-related needs of students; thus, resulting in an adapted version of the curriculum. The adapted curriculum included a subset of sexual health education lessons (MS n = 10; HS n = 13) and was delivered to students during the 2015–2016 academic year (AY). The sexual health education lessons were delivered to both same- and mixed-sex classes under individual school administrator preferences. Middle school lessons covered puberty, human reproductive system, benefits of abstinence, HIV/STDs preventions facts, and skills to refusal sexual pressure. Meanwhile, the HS topics included benefits of abstinence, strategies for preventing HIV/STDs and avoiding pregnancy, HIV/STDs testing, and using condoms consistently and correctly.

PD: in-person trainings.

The school district facilitated in-person trainings for health education teachers during the 2015–2016 AY: three trainings for HS teachers (August and October 2015, and February 2016) and four for MS teachers (August and October 2015, February and March 2016). Trainings were designed to increase teachers’ knowledge, confidence, and skills in core curriculum components (e.g., lesson objective, activities, and assessment strategies). Using small and large groups activities, lesson modeling, and teach-back scenarios, teachers drew on the shared expertise of peers and training facilitators to better understanding effective delivering of the curriculum. Moreover, novice and veteran teachers were able to learn from one another, sharing teaching strategies and insights to improve delivery. The trainings were facilitated by individuals external to the district including one of the curriculum developers, national non-governmental organization staff, and university school health researchers.

PD: observations and personalized coaching.

Teachers delivering the curriculum also received personalized coaching and feedback from district staff following observations of their teaching. Classroom observations were conducted throughout the 2015–2016 AY, allowing district staff to observe lesson components in real-time and serving as opportunities to provide teachers with needed materials (e.g., chart paper and markers) to support instruction. District staff used the observations to provide feedback on strengths and areas of improvement within the lessons and encourage teachers to reflect on their teaching practice. Using results and feedback from the observations, district staff provided repeat observations and intensive coaching based on the needs of individual teachers. The dosage of coaching support was not uniform but rather was tailored to the skills and needs of each teacher as observed in the classroom.

3.2. Eligibility criteria

A purposive convenience sample of MS and HS health education teachers was recruited for semi-structured interviews about their experiences delivering the curriculum and receiving district-provided training and coaching. Selection and inclusion criteria included: 1) having taught health education during the 2015–2016 AY, which included teaching sexual health lessons from the adapted curriculum; and 2) having attended at least two of the school district’s in-person trainings during the 2015–2016 AY. The participating school district provided the study team with a list of eligible health education teachers, with information on characteristics such as years teaching, certification, and health education background. Using this list, 30 health education teachers were identified. These teachers received information about the study and were invited to participate, resulting in a final sample of 24 MS and HS health education teachers. In accordance with CDC’s ethics guidelines, approval from the Institutional Review Board at ICF and the Research Review Board of the participating school district was obtained for all study protocols and instruments.

3.3. Procedures

A total of 24 semi-structured interviews were conducted in spring 2016 with 13 MS and 11 HS teachers. Interviews were led by an independent evaluation team and conducted in a private location at each teacher’s school, usually in a classroom during planning periods. Prior to the start of each interview, informed consent was obtained from each teacher. Each interview lasted approximately 45–60 min and was audio recorded for transcription and thematic analysis. Following interviews, teachers received a $20 gift card for participation.

3.4. Instrument

Semi-structured interviews examined teachers’ perceptions and experiences delivering sexual health education and the effectiveness of the district-provided supports in improving teacher practices. The interview guide was developed through an iterative process of reviewing existing measures and literature, consultation with experts in the field, and pilot testing with former teachers. The final guide comprised 19 open-ended items focused on teacher background/experience; attitudes, comfort, and confidence related to sexual health education; delivery of sexual health education lessons; and perception of PD effectiveness.

3.5. Data collection and analysis

Audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim. Qualitative data were managed and analyzed using MaxQDA software (VERBI Software, 2016). Initial codebooks were developed based on key questions of interest and relevant constructs from existing literature. Study team members (n = 3) discussed each code to reach agreement on a final code list and developed an accompanying code dictionary. To establish inter-coder agreement, team members double-coded a sub-sample of interviews (25%, n = 6) and discussed agreement and discrepancies, resulting in 100% agreement among coders.

Once discrepancies were resolved and inter-coder reliability was established, remaining teacher interviews (n = 18) were coded by one member of the team using an inductive, open coding analysis approach (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). Next, team members applied axial coding techniques to categorize and sub-categorize data to identify relationships based on similarities and differences (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Informed by district-provided implementation framework, coded data were grouped into broad, emergent categories and thematic content comparisons were explored (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). No categories and groupings were determined a priori, and team members used iterative discussion and consensus to compile illustrative quotations that represented detail and richness in the data (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). Triangulation (Patton, 2002) using interview data, extant literature, and team members’ expertise allowed for a deeper understanding of outcomes from district-provided supports that influenced teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills in delivering sexual health education.

4. Results

The study team conducted 24 interviews with 13 MS (8 male, 5 female) and 11 HS health education teachers (4 male, 7 female). Middle school teachers reported an average of 3.6 years (range 1–30) of experience teaching health education, while HS teachers reported an average of 5.5 years (range 2–16) of experience teaching health education. Specific to teaching sexual health education, MS teachers reported an average of 1.1 years (range 1–2) of teaching experience, whereas HS teachers reported an average of 5.0 years (range 1–16). Last, 76.9% of MS teachers (n = 10) and 90.9% of HS teachers (n = 10) self-identified as an athletic coach within the school district.

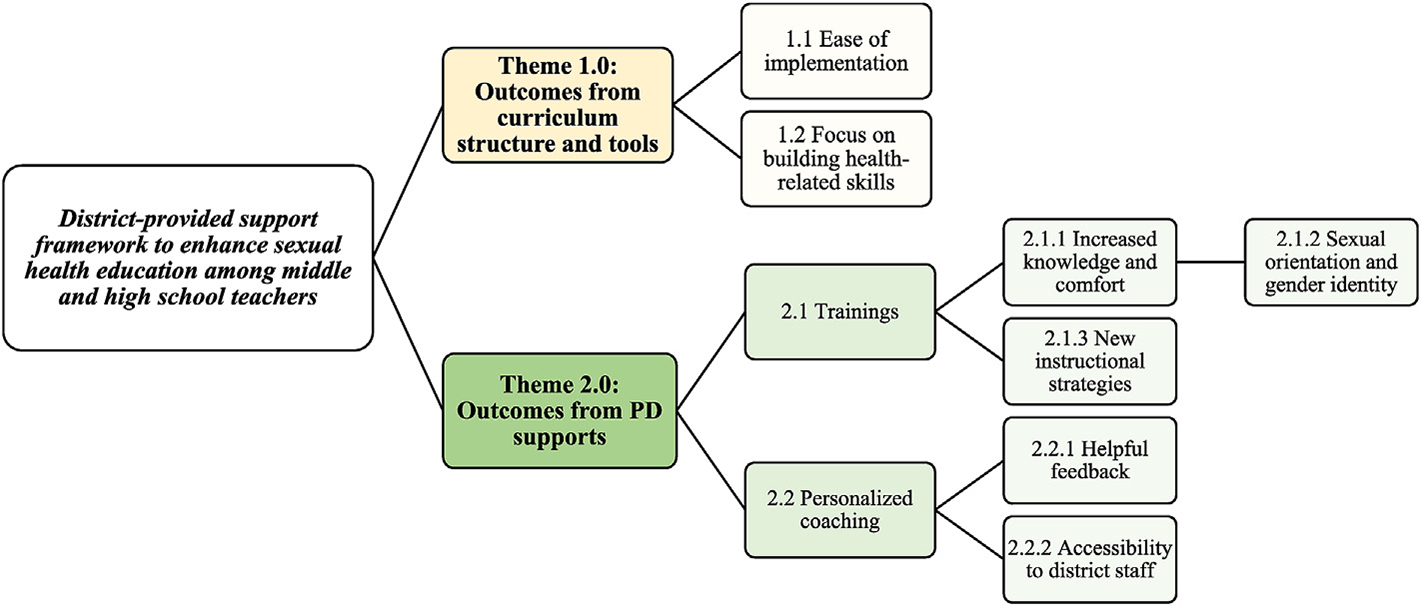

Two major themes and unique sub-themes emerged to describe teachers’ self-reported outcomes from engagement with district-provided supports (Fig. 2). Major themes included outcomes related to the (1) curriculum and sexual health education lessons support, and (2) professional development support (in-person trainings and personalized coaching). Sub-themes included curriculum’s ease of implementation and focus on health-related skill building; improved knowledge and comfort and use of new instructional strategies; and helpful feedback and accessibility to district staff. Each major theme and sub-theme include salient quotes to illustrate teachers described the district-provided supports increased their knowledge, comfort, and skills to deliver sexual health education in MS and HS.

Fig. 2.

Major themes describing outcomes from the district-provided support framework to enhance sexual health education.

4.1. Theme 1.0: Outcomes associated with the curriculum structure and tools

Teachers perceived the adapted curriculum and sexual health education lessons to be beneficial to their instructional practice. Many teachers reported the curriculum was easy to implement, organized, included pertinent health information, and had an intentional focus on building health skills. Teachers believed the curriculum helped enhance their comfort with specific sexual health education topics; one MS teacher commented,

“What I really love is the book [curriculum] doesn’t put the teacher in a bad situation because it is excellent. It gives you different ideas to where, different assignments you can choose from … It gave you options of whether you can do a word box, or there’s a different thing. They give you options of what you can chose, depending’ on what type of students you have or what kind of teacher you have. I like that, I definitely like that.” – MS Teacher

Overall, teachers spoke in-depth about two unique curriculum elementsdease of implementation and focus on health-related skill Building—and described how these elements supported their knowledge, comfort, and skills delivering sexual health content for students.

4.2. Ease of implementation

Both MS and HS teachers spoke favorably about the adapted curriculum and sexual health education lessons. Most believed the curriculum included all pertinent information needed to adequately and appropriately address students’ questions and teach content. More common among HS teachers was an appreciation of the adapted curriculum’s layout and structure (i.e., set units with pre-determined content, student workbooks, and PowerPoint slides). Teachers reported the organization facilitated greater ease and consistency in implementation across semesters, while also noting decreased preparation and rehearsal was needed before delivery. Illustrating this favorable curriculum characteristic, one teacher remarked,

“Like I said, there’s a structure to it. It’s like a map. There’s actually a guide on, Okay, talk about this before you talk about this. Then go into this. My comfort level is a lot higher now with that guide and that structure.” – HS teacher

While another HS teacher reported,

“… the structure helps. It helps limit the possibility of chaos, especially in that subject, because if there’s not structure, the students can go left [get sidetracked] with the simplest questions. This keeps everything structured. It keeps everyone going towards the goal of them learning this, whichever topics we’re on.” – HS teacher

Because of the format of the adapted curriculum, all teachers in the study (24%) reported they adhered to core curriculum components such as the lesson learning objectives, small and large group activities, and assessment strategies. Teachers perceived the sexual health education lessons as easy to follow, thus contributing positively to their knowledge, comfort, and skills during implementation.

1.2. Focus on health-related skill building.

Teachers, particularly those working in HS, described the curriculum as having an intentional focus on enhancing student skills through repetition and practice; critical components to promoting positive behavior change. One HS teacher stated,

“… our curriculum helps them [students] with skills. They address these skills, assessing the risks, weighing possible outcomes, making decisions about complicated topics. In the curriculum, we work through these things—set goals for their lives and their future, we work through those things. We help them solve problems in the curriculum. We talk about difficult topics in the curriculum. Practice things that keep them healthy, even when it is hard to do, we talk about that. Whether they do that or not, my job as a teacher is to talk to them about that.” – HS teacher

The curriculum’s focus on skill building required teachers to use teaching approaches that moved beyond the didactic and instead fostered the development of critical thinking and decision-making skills in students. Another HS teacher reflected,

“In my view, that’s one of the furthest—the highest levels of teaching that you can get to, where the kids are actually practicing the skills … having the students practice, figuring out how to have them practice what they’re learning, is a higher level of teaching.” – HS teacher

4.3. Theme 2.0: Outcomes from PD supports

As part of the district-provided PD support, teachers were offered in-person trainings and personalized coaching to increase their knowledge, comfort, and skills for implementing the sexual health education lessons. First, trainings focused on teacher mastery of lesson content through interactive teach-back and skill building exercises with peers. Reflecting on the overall experience of the trainings, one teacher asserted,

“I think they did a really good job of making the purpose, the process, and the concepts clear and gave us time to practice and think about them.” – MS teacher

Another teacher described the trainings by saying,

“I like the way they’ve [the in-person trainings have] been done because we aren’t just sitting listening. We’re actually involved in the learning process. We get input, but then we also get involved in the learning process. I think it’s helpful and it gets you on your feet and has you thinking about how things work for both adults and students at the same time.” – HS teacher

Teachers reported significant improvements in their knowledge and comfort as they participated in trainings.

4.3.1. Training: increases in knowledge and comfort

Most teachers believed they were more knowledgeable and comfortable teaching the sexual health education lessons after completing the in-person trainings. One teacher remarked,

“Because, before, I said I was comfortable and all that. Yeah, I was comfortable in those things, but the actual confidence … I now feel prepared to be able to teach it and talk to the kids about it, and still learning myself, but I just have more confidence in it just because I’ve gone through a lot of trainings. Yeah, I just have a lot of confidence now.” – HS teacher

Teachers reported that participating in the trainings increased their understanding of lesson content, skill-building activities, assessment strategies, and instructional pacing. Teachers said the trainings helped clarify misperceptions about specific health content, provided up-to-date statistics and information, and illustrated interactive ways to deliver information. One MS teacher reflected on instructional practices prior to trainings by saying,

“Yeah, I mean I talked a lot about HIV and STDs transmission. Before the curriculum and training, I went more into the shaming side of the STDs as a scare tactic. I’m so glad that we’ve gone away from that, because I think that’s an erroneous way go about teaching it” – MS teacher

Trainings highlighted valid and reliable sources of health information teachers could cite during instruction and later used to help students make appropriate and informed decisions. Several teachers reflected on this characteristic. For example, one teacher said,

“Before the trainings, [we did] not [have] as much [knowledge], not as much at all, especially sources of reliable sexual health information, like where the kids can actually go to get other information” – HS teacher

Another remarked,

“… the sources for reliable sexual health information, I felt more confident [after PD training] in that because … the first lesson in the unit discusses … some good sources for students to find not just sexual health information but also general health information.” – MS teacher

4.3.2. Training: sexual orientation and gender identity

As teachers reflected on their initial knowledge and comfort teaching sexual health, many of them expressed initial discomfort teaching sexual orientation and gender identity. Teachers credit the training with enhancing their knowledge on sexual health education topics broadly, but also fostering their understanding and confidence to address sexual orientation and gender identity within the context of sexual health. The training provided common language and instructional guidance for talking about sexual orientation and gender identity and teachers reported feeling less uneasiness and discomfort when discussing issues with students. One teacher recalled,

“[I am] more confident about how gender role, gender identities, and gender expressions influence sexual health. Four years ago, that’s something I might have barely touched on and not really went into a conversation about that. Now, like I said, with the guidance on how this conversation should be held, it’s easier to go through those talks.” – HS teacher

4.3.3. Training: using new instructional strategies

Teachers also described an enhanced ability to use new, innovative instructional strategies in the classroom, post engagement with PD supports. Both MS and HS teachers reported enhanced self-efficacy implementing teaching strategies they learned through training and from feedback and coaching experiences. During the trainings, teachers took part in teach-back exercises, which were largely described as beneficial for watching how peer teachers in the district implemented specific lessons. One teacher reported,

“I think we have some really good teachers in this district. Some of the approaches are better than others and I try to find the best and steal little pieces of what that teacher does … or an example that a teacher gave. I’m like, you know what? I’m going to use that example right there. That’s a really good example that they used. I really do think the teach-backs were very helpful” – MS teacher

High school teachers reported feeling more comfortable and confident in implementing sexual health education activities, such as the condom demonstration, after watching model lessons and practicing lesson implementation with feedback from peers and PD facilitators. Opportunities to share ideas and seek advice from others proved valuable to identifying effective approaches to use during the sexual health education lessons. Other strategies cited by the teachers included using a carousel interactive activity and incorporating physical movement breaks into the sexual health education lessons. One teacher recalled,

“I really like getting more of these teaching strategies or instructional strategies. I mean I try to find different ways. I basically try to turn my classroom into PE class, somehow that we are moving around. I like carousel activities a lot, because the kids sit so long during the day” – HS teacher

One MS teacher reflected on the effectiveness of the in-person trainings by saying,

“I feel much more comfortable just coming along with teaching more, and then have to do using the teach backs, like teaching to our peers at the professional development, being shown the lessons firsthand, having someone else teach it and you watch it. You’re like, “Oh, I didn’t think about,” or just more comfortable actually talking it out to someone instead of showing a condom demonstration the first day in class and never had done it before” – MS teacher

Teachers also reported the trainings enhanced their classroom management skills within the context of sexual health education. The school district deliberately included a wide variety of instructional strategies—some curriculum-specific (e.g., condom demonstrations from the sexual health education lessons) and others related to managing and creating classroom environments conducive to learning—to improve teacher’s instructional competencies. One teacher said,

“After my professional development I would say though, I felt more prepared to teach and to implement classroom management techniques for the unit specifically and as well to create that safe and positive learning environment for the students for the human sexuality instruction.” – MS Teacher

A HS teacher described improved teaching skills gained throughout training by saying,

“Effective instructional strategies, it’s way better now. Student skill on HIV and STDs, and pregnancy prevention, it’s much better now, I can say that. Assessing student knowledge and skills is way better. Appropriate classroom management techniques, that’s good, better. Creating a comfortable and safe learning environment is better. Everything is better.” – HS teacher

Although most teachers reported in-person trainings as valuable and necessary for improving knowledge and skills, a few teachers shared that trainings did not improve their ability to deliver sexual health education lessons. Veteran teachers, when compared to novice educators, commented on the repetitive nature of some trainings and showed a lack of “challenge” within the training’s current offerings. One teacher noted,

“Honestly, there was nothing that really jumped out that was like, whoa, that’s new – I didn’t know that. There wasn’t really anything that kind of hit me that was out of left field that I didn’t really know about already” – MS teacher

While another teacher said,

“I mean, hearing the same information, twice in two different PD trainings was okay, but the third time was overkill to me.…In that way, I wish they would split the people that haven’t done this multiple times, because it does seem like we could do more” – HS teacher

Teachers recommended providing breakout training sessions based on attendees’ knowledge, experience, and skill to foster deeper learning and application. Teachers believed that targeting training would encourage meaningful discussion on specific topics, opportunities to pilot advanced teaching strategies, and time to co-plan and collaborate with others who share similar expertise. Teachers thought a tailored approach would encourage deeper reflection and discussion of skill-building activities.

4.4. Observation and personalized coaching

The final PD supports sub-theme described outcomes related to observations and personalized coaching teachers received. To ensure teachers felt supported and were implementing sexual health lessons with consistency, school district staff conducted classroom observations and offered personalized coaching to health education teachers. Observation and coaching allowed district staff to ensure fidelity to lesson objectives, content, and assessments while also providing opportunities to observe implementation in real time. One teacher stated,

“The observations, it’s a chance for them [the district staff] to be in the classroom to see that all of our schools are different. Even all of our classrooms are different. There’s certain ways that certain teachers have to deliver lessons. So it lets them see, Okay, this is why this is like this.” – HS teacher

Another teacher commented the personalized coaching helped instill confidence in their teaching practice, by stating:

“I guess just knowing that I had people that I could turn to and I knew that they had my back if I needed some help. That was important to me. I know that if something happened or something went wrong, then I knew that they were behind me and helping me get the things that I needed to be successful, and that the kids would also be successful.” – HS teacher

Most classroom observations included a debrief component in which the district staff and the health education teacher reflected on the lesson immediately following implementation. While inconsistent across all observations because of lack of time, the completed debriefs allowed the teacher to analyze his or her own teaching practices with feedback and instructional recommendations from the district observer. District staff made follow-up visits to the teacher’s classroom and provided tailored help based on teaching goals identified during the observation debrief and reflection.

4.4.1. Observation and personalized coaching

helpful feedback.

Most teachers believed the district provided adequate resources and support for them to deliver the sexual health education lessons. Teachers said the coaching was “helpful and informative” to their teaching practices and one teacher commented,

“They’ll come in and check on you. If you need extra support, you can call them anytime … I mean they are very supportive, very involved. No, I love it. I think they’re doing a fantastic job.” – HS teacher

Most teachers did not perceive the classroom observations and coaching to be critical or punitive, but instead felt the tailored feedback helped identify strengths within their lesson delivery and areas for improvement. One HS teacher asserted,

“He’s [district observer is] just so easy to talk to. He lets you know, ‘I’m not here to try to catch you doing or to correct you. I’m here to help you whatever you need help with. If you are struggling because you feel that, tell me and let’s figure out what we can do about it.’ Yeah, he’s awesome” – HS Teacher

Despite substantial support for the personalized coaching, a few teachers, mainly MS teachers, cited feelings of nervousness associated with the observation and coaching. Teachers shared being observed brought feelings of anxiety and made them question their teaching style and skills. One teacher stated,

“At first, it made me nervous. I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, someone’s going to watch me do this?’ It was different doing it in my own classroom and just having’ the kids cuz I don’t really care what the kids think, I guess, but another adult, I was like, ‘Ooh.’ I get nervous talking in front of peers. It’s not one of my strong strengths or anything—I get nervous.” – MS teacher

Some teachers noted inconsistencies in the district’s observation schedule and reported this contributed to anxiety and fear. Some teachers reportedly had multiple (e.g., 8 times) observations during the year, whereas others were only observed once. Teachers communicated a desire for a more fair distribution of classroom observation, promoting more consistency across school buildings and teachers.

4.4.2. Observation and personalized coaching: accessibility to district staff

The personalized coaching also resulted in teachers having on-demand access to district staff to help mitigate challenges. One teacher remarked,

“If you run into a road bump or you have trouble with a student or you have trouble with something in the curriculum you just don’t understand, there is a support system here. I found it to be very helpful and like I said, I’m not in a district where they’re gonna turn their back on me” – MS teacher

And another teacher felt fully supported by district staff and said,

“They [district staff] are very helpful … if you email them; they’re really quick about getting back to you. I love how they do not ever leave you just out and dry hangin’. They give you a lot of tools. Last week, I had a meeting and they gave me some tools to help with the sex education. That next day they was up here with different tools, a list, and everything. They really support you” – MS teacher

Teachers believed the personalized coaching created more accessibility, or instant access, to district staff to help mitigate challenges with lesson materials, technology, and instruction. The accessibility fostered a “culture of support” in which teachers perceived staff, administrators, and the district supported their sexual health education efforts. However, for some teachers, the observation and coaching process created some level of anxiety.

5. Discussion

The district-provided support improved teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills for delivering sexual health education in middle and high schools. The adapted curriculum guided teachers in their implementation of content, activities, and assessment strategies, providing a structured “map for teaching” and unique focus on building students’ health-related skills. The PD support of in-person trainings elevated teachers’ knowledge and comfort with sexual health information and topics, introduced innovative pedagogy and classroom management strategies, and allowed teachers to give and receive critical feedback from peers and facilitators. However, some trainings may have felt repetitive to more veteran teachers who attended all the offerings. Finally, the personalized coaching PD support from district staff provided tailored recommendations to help teachers improve their sexual health education delivery. The ongoing coaching integrated teachers’ experience, classroom observations, training participation, and personal reflections. The reinforcement of PD activities and messaging through training and coaching proved an effective mechanism to meet teachers’ evolving learning needs. As conceptualized in Fig. 1, successful improvements in teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills were reported as a result of the school district providing the necessary supports to improve teaching practices in sexual health education.

Our study illustrated that as schools provide clear curriculum support—which includes choosing a curriculum, training teachers on it, and providing ongoing support—teachers report more confidence in classroom-based instruction. This finding is supported by other research from Lindau, Tetteh, Kasza, and Gilliam (2008) asking teachers to identify reasons why they omitted certain sexuality topics from instruction; results concluded a lack of teaching materials was the only reason rated by a majority of teachers as being an important influence on topic selection and delivery. Research suggests curricular materials that include learning objectives and outcomes, activities, and assessment strategies to evaluate students’ skill mastery are critical components of a curriculum (CDC, 2012). In providing curriculum and supporting materials to teachers, school districts can ensure the use of medically accurate, developmental appropriate, and culturally inclusive and affirming sexual health education materials which reflect local priorities and student health needs (Kirby, 2007, 2011; CDC, 2015; Payne & Smith, 2011).

The school district in this study introduced a curriculum focusing heavily on enhancing students’ skills, which was cited by teachers as helpful in guiding their teaching practices. These findings suggest that school districts may find the selection of strong curriculum with a skill-building focus to be helpful for enhancing teachers’ instruction of sexual health education but must be cognizant of additional PD required to train teachers on skills-driven curriculum. A widely accepted standards framework, the National Health Education Standards (NHES) (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2007), articulates seven performance-related skills and indicators to consider when creating and delivering health education curricula. Additionally, the CDC’s HECAT is a valuable tool to systematically analyze new or existing health curriculum and instructional materials and is aligned to the NHES and Characteristics of Effective Health Education Curricula (CDC, 2018).

This study also found that district-provided PD (i.e., training and personalized coaching) was associated with improvements in teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and use of pedagogical strategies during classroom-based delivery. The positive results produced from the PD in our study also align with previous research by Clayton et al. (2018), Jones et al. (2004), Eisenberg, Madsen, Oliphant, and Sieving (2013), and Ninomiya (2010) describing effectiveness of PD trainings, via multiple modalities, on teachers’ knowledge and comfort implementing sexual health topics and classroom practices. Without knowledge and comfort in sexual health education, teachers may feel less able to implement classroom instruction (Byers, Sears, & Foster, 2013). Mkumbo (2012) and Ninomiya (2010) explain this phenomenon, reporting MS teachers’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality were important predictors of willingness and implementation of curriculum. Moreover, a study by Levenson-Gingiss & Hamilton (1989) testing effects of teacher in-service training described increases in knowledge, perceptions of importance of teaching the curriculum, intent to teach curriculum, and level of comfort with sexual health course content as outcomes from in-service training.

Besides improvements in the general sexual health knowledge, teachers also appreciated additional training on the topics of sexual orientation and gender identity. For sexual health education to be effective, it is essential that it reach youth who are at disproportionate risk for adverse sexual health outcomes; this includes sexual and gender minority youth (Clayton et al., (2018), Johns et al., 2019). Many teachers, however, struggle to know the most appropriate way to create or adapt lessons or to speak appropriately to sexual and gender minority youth. In this particular school district, the curriculum in use was one designed with a goal of ensuring all students, including sexual minority and gender minority youth, could see themselves represented in both content and skill-building activities. However, even with appropriate curriculum, teachers may need additional supports to increase their comfort with topics of sexual orientation and gender identity and using language and strategies that can best reach these youth (ETR, 2019b). Thus, in-service training that improves the ability of health education teachers to do so can have a far-reaching impact on all student’s health and on teachers’ self-efficacy. In our study, teachers explained that PD helped clarify misconceptions, promoted use of correct language and terminology, and introduced inclusive teaching strategies to engage all youth. As part of PD, schools can help strengthen teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills in meeting the needs of all youth, and specifically competencies for serving sexual and gender minority youth, by incorporating PD on establishing and managing safe learning environments and helping teachers discuss sexual and gender minority topics respectfully and nonjudgmentally in the classroom, an emergent theme of the PD support framework in our study. This finding echoes other research highlighting the critical importance of appropriate PD for teachers and school staff (Kosciw et al., 2013; Swanson & Gettinger, 2016).

PD supports also improved teachers’ classroom management strategies. Teachers reported ongoing need for training on effective classroom management, specifically for sexual health education. This finding complements results from a 2013 survey that reported over 40 percent of new teachers felt either “not at all prepared” or “only somewhat prepared” to handle a range of classroom management or discipline situations (Coggshall, Biyona, & Reschly, 2012). Integrating other instructional competencies, like classroom management, into PD can help teachers deliver content more effectively and lead to strong student engagement and on-task time (Greenberg, Putman, & Walsh, 2014).

Teachers reported the use of new, innovative pedagogical strategies resulting from the PD activities in our study, and their descriptions of key learning experiences suggest reserving adequate time to practice new skills as important conditions to consider in future PD frameworks (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Teachers need time to develop, absorb, discuss, and practice new knowledge (Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001), suggesting PD supports should be sustained and intensive rather than brief and sporadic (Opfer & Pedder, 2011; Avalos, 2011).

Additionally, teachers valued the opportunity to observe veteran teachers or trainers’ model lessons during PD and then being given opportunities to receive expert feedback on their own teachback to peers. This strategy was described as helpful in their building confidence and self-efficacy and is considered an evidence-based practice. For example, studies suggests teachers are less likely to change practice because of learning activities that occur strictly via presentation and memorizing new knowledge (Loucks-Horsley, Hewson, Love, & Stiles, 1998; Garet et al., 2001; Birman, Desimone, Porter, & Garet, 2000; Desimone, Porter, Garet, Yoon, & Birman, 2002; Wayne, Yoon, Zhu, Cronen, & Garet, 2008); therefore, incorporating active learning—allowing teachers to practice pedagogical strategies they will actually replicate for their students—provides highly contextual and authentic training experiences (Ingvarson, Meiers, & Beavis, 2005; Patton, 2002) and can result in increased student learning (Stoll, Harris, & Handscomb, 2012). Specific active learning exercises using role-play to simulate activity implementation or answering difficult questions can be used to assist sexual health education teachers strengthen their practice (Herbert & Lohrmann, 2011; Ingvarson; Meiers, & Beavis, 2005).

Teachers in this study recommended using a tiered approach for in-person trainings based on teacher experience, level of expertise, and unique needs. Specificity and individualized PD would have allowed the sexual health education teachers to target varying pedagogical practices (e.g., novice versus advanced techniques), foster in-depth discussion, and facilitate opportunities for stronger collaboration with peers. Darling-Hammond et al. (2009) echoed benefits of a multi-level approach by reporting a ‘one solution for all’ strategy cannot address teachers’ unique learning needs and suggest using communities of practice (CoP), and individual or group coaching, including peer coaching, as pivotal strategies for success. Relatedly, research by Valcke, Rots, Verbeke, and Van Braak (2007) illustrates a successful tiered-PD system, reporting secondary schools teachers preferred training methods that stressed individualized learning (e.g., using self-study and online learning) that complimented teachers’ personalized learning preferences. Offering tailor-made courses and PD activities for teachers based on expertise level and experience may improve satisfaction with PD activities and improve transfer of pedagogical strategies to classroom practice.

Regarding the district’s final PD support, observation and personalized coaching, teachers reported these strategies as helpful in refining their teaching practices in sexual health education. A critical review of school-based coaching programs showed, for novice teachers, mentoring and guidance produced positive effects on teachers’ instructional activities, classroom management strategies, and student achievement tests (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011). Additional studies report instructional delivery, teacher satisfaction, and retention were positively associated with participation in personalized mentoring programs (Darling-Hammond, 2003; Heider, 2005).

Schools could consider systematic classroom observations and personalized coaching, via individual, peer, or group deliver, programs as necessary (Ehrich, Hansford, & Tennent, 2004) to build new knowledge and skills for teachers in sexual health education. In designing observation and coaching programs, it is critical to establish trust and rapport between teachers and observation staff to mitigate feelings of anxiety and fear often associated with classroom observations (Telljohann et al., 1996).

To strengthen effectiveness of coaching, it is important that school districts allow time for personalized feedback and discussion after classroom observations. The coaching should integrate teachers’ background and experience, comfort level, and instructional expertise into a loop of ongoing feedback and guided self-reflection that supports teachers’ professional learning through acquisition of new knowledge and skills. A few teachers in our study described feelings of angst and fear surrounding the observations, presenting a potential barrier to conducting sessions with teachers. Schools need to foster ongoing trust and rapport between district staff and teachers prior to any classroom observation to ensure teachers are comfort with delivery and observers capture valid and reliable data related to fidelity.

This study highlights the need for additional research that explores the influence of district-provided support frameworks on teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills in sexual health education. Although our qualitative approach provided richness and context for understanding the influence of curriculum and PD on teachers’ instructional practices, additional studies using objective measures, such as standardized observation instruments to measure fidelity of implementation (O’Donnell, 2008; Resnicow et al., 1998) and measures of students’ knowledge and health behavior, both before and after introduction of support frameworks are needed.

More rigorous measurement and evaluation methods to assess critical features of PD (e.g., content-focused, integration of active learning), mode of delivery (e.g., in-person workshop, self-study, and asynchronous online platforms), and duration (e.g., standalone or booster sessions) on observed and self-reported teaching practices can provide additional evidence of effective components for PD in sexual health education (Desimore 2009; Garet et al., 2001). Limiting our overreliance on teacher satisfaction data as the sole measure to determine effectiveness of curriculum and PD—a common practice in the peer-reviewed literature—and expanding to measure critical features of PD and associations with actual teaching behavior will advance the field’s understanding of the connection between teachers’ professional learning and student learning (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Desimore 2009; Garet et al., 2001).

Last, a recent study by (Murray 2019), using a teacher sample that overlaps with the one in this study, examined teachers’ characteristics and PD participation related to gains in student health-related knowledge. Findings revealed a significant relationship between teachers’ participation in PD and increased student health knowledge scores among teachers who taught middle school. This is one of the first studies to investigate gains in student performance based on training participation specifically among sexual health education teachers, opening the door for future investigation in this area. Additional studies measuring associations between health education teachers’ participation in district-provided support frameworks and student academic performance and health behavior outcomes are needed.

5.1. Limitations

Although these findings provide important insights about district-provided supports for sexual health education, this study is not without limitations. Due to the convenience sampling, recruitment from a single school district, and limited sample size (n = 24), the findings are not generalizable to teachers and staff in other school districts. Teacher participation was voluntary and no randomization of participants to curriculum intervention group took place; explicit teacher motivations and reasoning for participation are largely unknown and authors acknowledge potential for bias in responses due to study self-selection. The study asked teachers to retrospectively report on their perceived knowledge, comfort, and skills prior to participating in a district-provided support framework and thus results may be subject to both self-report and recall biases. Additionally, our study did not include a standardized curriculum fidelity instrument and relied solely on self-report teacher perception of fidelity of curriculum implementation. The findings herein did not examine actual curriculum fidelity and implementation quality and thus are subject to bias and over-reporting of strict curriculum components and adherence by HS and MS teachers. This limitation prohibits conclusions about true measures of fidelity (e.g., dosage and adherence to intended design) across classroom observations.

6. Conclusions

Supporting the professional learning and development of teachers requires the same level of rigor and dedication from school districts as does supporting student learning and performance. Our study illustrates that a district-provided support framework that includes necessary curriculum tools and PD for teachers appears to be a feasible and realistic approach for supporting sexual health education. Providing high-quality curriculum guidance and instructional recommendations generated through tailored PD supports may positively influence teachers’ knowledge, comfort, and skills within sexual health. Well-equipped and supported teachers are, in turn, positioned to provide the high-quality instruction necessary for students to develop the essential knowledge and skills to reduce HIV, STDs, and unintended pregnancy.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Teachers need the same tailored support and scaffolding to improve their knowledge and skills as students do.

Curriculum, training, and instructional coaching improve teachers’ delivery in sexual health education.

Teachers’ self-efficacy and skilled use of interactive pedagogy increased after district-provided professional development.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff involved in the data collection as well as the staff of the Fort Worth Independent School District for their support of this data collection. We would also like to thank Thearis Osuji, Noah Drew, Pete Hunt, Susan Telljohann, Kelly Wilson, and Healthy Teen Network for their contributions to this project.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH) in the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Contract #HHSS2002013M53944B Task Order #200-2014-F-59670.

Footnotes

Conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Leigh E. Szucs: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Catherine N. Rasberry: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Supervision. Paula E. Jayne: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. India D. Rose: Writing - review & editing. Lorin Boyce: Writing - review & editing. Colleen Crittenden Murray: Writing - review & editing. Catherine A. Lesesne: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. J. Terry Parker: Writing - review & editing. Georgi Roberts: Writing - review & editing.

References

- American Association for Health Education [AAHE]. (2008). 2008 NCATE health education teacher preparation standards. Retrieved from https://hawaiiteacherstandardsboard.org/content/wp-content/uploads/AAHE_and_NCATE_2008stds.pdf.

- American Cancer Society [ACS]. (2007). National health education standards. Journal of School Health, 63, 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- Avalos B (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Birman BF, Desimone L, Porter AC, & Garet MS (2000). Designing professional development that works. Educational Leadership, 57(8), 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, McManus T, Wechsler H, & Kann L (2013). Trends in professional development for and collaboration by health education teachers—41 states, 2000–2010. Journal of School Health, 83(10), 734–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES, Sears HA, & Foster LR (2013). Factors associated with middle school students’ perceptions of the quality of school-based sexual health education. Sex Education, 13(2), 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Public Education. (2013). Effective professional development in an era of high stakes accountability. Retrieved from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/system/files/Professional%20Development.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Health education curriculum analysis tool (HECAT). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Characteristics of an effective health education curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Characteristics of an effective health education curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm.

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, Mercer SL, Chattopadhyay SK, Jacob V, … Griffith M (2012). The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 272–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton HB, Brener ND, Barrios LC, Jayne PE, & Everett Jones S (2018). Professional development on sexual health education is associated with coverage of sexual health topics. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 4(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Coggshall JG, Bivona L, & Reschly DJ (2012). Evaluating the effectiveness of teacher preparation programs for support and accountability. Research & policy brief. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543773.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JN, Sears HA, Byers ES, & Weaver AD (2004). Sexual health education: Attitudes, knowledge, and comfort of teachers in New Brunswick schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, & Strauss A (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L (2003). Keeping good teachers: Why it matters, what leaders can do. Educational Leadership, 60(8), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L, Hyler ME, & Gardner M (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Retrieved from Palo Alto, CA: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L, Wei RC, Andree A, Richardson N, & Orphanos S (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession (Vol. 12). Washington, DC: National Staff Development Council. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, & Lincoln YS (2005). The sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone LM (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone LM (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6), 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone LM, Porter AC, Garet MS, Yoon KS, & Birman BF (2002). Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrich LC, Hansford B, & Tennent L (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518–540. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Madsen N, Oliphant JA, & Sieving RE (2013). Barriers to providing the sexuality education that teachers believe students need. Journal of School Health, 83(5), 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Madsen N, Oliphant JA, Sieving RE, & Resnick M (2010). “Am I qualified? How do I know?” A qualitative study of sexuality educators’ training experiences. American Journal of Health Education, 41(6), 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- ETR. (2014). Tool to assess the characteristics of effective sex and STD/HIV education programs (TAC). Retrieved from https://www.etr.org/store/product/tool-to-assess-the-characteristics-of-effective-sex-hiv-education-programs/.

- ETR. (2019a). HealthSmart comprehensive health curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.etr.org/healthsmart/.

- ETR. (2019b). HealthSmart FAQs. Retrieved from https://www.etr.org/healthsmart/about-healthsmart/faq/.

- Future of Sex Education [FOSE]. (2011). National teacher preparation standards for sexuality education. Retrieved from http://www.futureofsexed.org/teacherstandards.html.

- Garet MS, Porter AC, Desimone L, Birman BF, & Yoon KS (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945. [Google Scholar]

- Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, Terzian M, & Moore K (2014). Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Putman H, & Walsh K (2014). Training our future teachers: Classroom Management. Retrieved from https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/Future_Teachers_Classroom_Management_NCTQ_Report.

- Guba EG, & Lincoln YS (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2(163–194), 105. [Google Scholar]

- Heider KL (2005). Teacher isolation: How mentoring programs can help. Current Issues in Education, 8(14), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert PC, & Lohrmann DK (2011). It’s all in the delivery! an analysis of instructional strategies from effective health education curricula. Journal of School Health, 81(5), 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll RM, & Strong M (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarson L, Meiers M, & Beavis A (2005). Factors affecting the impact of professional development programs on teachers’ knowledge, practice, student outcomes & efficacy. Professional Development for Teachers and School Leaders, 13(10), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, … Underwood JM (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SE, Brener ND, & McManus T (2004). The relationship between staff development and health instruction in schools in the United States. American Journal of Health Education, 35(1), 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D (2007). Abstinence, sex, and STD/HIV education programs for teens: Their impact on sexual behavior, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted disease. Annual Review of Sex Research, 18(1), 143–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D (2011). Reducing adolescent sexual risk: A theoretical guide for developing and adapting curriculum based programs. ETR Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby DB, Laris B, & Rolleri LA (2007). Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(3), 206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, Kull RM, & Greytak EA (2013). The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- LaChausse RG, Clark KR, & Chapple S (2014). Beyond teacher training: The critical role of professional development in maintaining curriculum fidelity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3), S53–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson-Gingiss P, & Hamilton R (1989). Evaluation of training effects on teacher attitudes and concerns prior to implementing a human sexuality education program. Journal of School Health, 59(4), 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Tetteh AS, Kasza K, & Gilliam M (2008). What schools teach our patients about sex: Content, quality, and influences on sex education. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 111(2), 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks-Horsley S, Hewson P, Love N, & Stiles K (1998). Designing professional development for teachers of mathematics and science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma ZQ, Fisher MA, & Kuller LH (2014). School-based HIV/AIDS education is associated with reduced risky sexual behaviors and better grades with gender and race/ethnicity differences. Health Education Research, 29(2), 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkumbo KA (2012). Teachers’ attitudes towards and comfort about teaching school-based sexuality education in urban and rural Tanzania. Global Journal of Health Science, 4(4), 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CC, Sheremenko G, Rose ID, Osuji TA, Rasberry CN, Lesesne CA, … & Roberts G (2019). The Influence of Health Education Teacher Characteristics on Students’ Health-Related Knowledge Gains. Journal of School Health, 89(7), 560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Teachers of Mathematics. (2012). NCTM CAEP standards (2012). Retrieved from https://www.nctm.org/Standards-and-Positions/CAEP-Standards/.

- National Science Teacher Association. (2012). NSTA Standards for science teacher preparation. Retrieved from https://www.nsta.org/preservice/.

- Ninomiya MM (2010). Sexual health education in Newfoundland and Labrador schools: Junior high school teachers’ experiences, coverage of topics, comfort levels and views about professional practice. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 19(1–2), 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer VD, & Pedder D (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81(3), 376–407. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CL (2008). Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K–12 curriculum intervention research. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 33–84. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Payne EC, & Smith M (2011). The reduction of stigma in schools: A new professional development model for empowering educators to support LGBTQ students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(2), 174–200. [Google Scholar]

- Preston M (2019). “I’d rather beg for forgiveness than ask for permission”: Sexuality education teachers’ mediated agency and resistance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Davis M, Smith M, Lazarus-Yaroch A, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, & Wang DT (1998). How best to measure implementation of school health curricula: A comparison of three measures. Health Education Research, 13(2), 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas E, Tannenbaum SI, Kraiger K, & Smith-Jentsch KA (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(2), 74–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Health and Physical Educators. (2018). [SHAPE America] (p. 3). Reston, Virginia: National Standards for Initial Health Education Teacher Education; (2018) (Author. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll L, Harris A, & Handscomb G (2012). Great professional development which leads to great pedagogy: Nine claims from research. Nottingham, UK: National College for School Leadership. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/335707/Great-professional-development-which-leads-to-great-pedagogy-nine-claims-from-research.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Stronge JH, Ward TJ, & Grant LW (2011). What makes good teachers good? A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(4), 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K, & Gettinger M (2016). Teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and supportive behaviors toward LGBT students: Relationship to gay-straight alliances, anti-bullying policy, and teacher training. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(4), 326–351. [Google Scholar]

- Telljohann SK, Everett SA, Durgin J, & Price JH (1996). Effects of an In-service workshop on the health teaching self-efficacy of elementary school teachers. Journal of School Health, 66(7), 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Peskin MF, Shegog R, Addy RC, Escobar-Chaves SL, et al. (2010). It’s your game: Keep it real: Delaying sexual behavior with an effective middle school program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(2), 169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcke M, Rots I, Verbeke M, & Van Braak J (2007). ICT teacher training: Evaluation of the curriculum and training approach in Flanders. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 795–808. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software. (2016). MAXQDA analytics pro [computer programme]. Berlin: Germany: VERBI. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne AJ, Yoon KS, Zhu P, Cronen S, & Garet MS (2008). Experimenting with teacher professional development: Motives and methods. Educational Researcher, 37(8), 469–479. [Google Scholar]