Abstract

Feature at a Glance: Nonadherence to hypertension medications is associated with negative health outcomes, which is of particular importance for older adults because of the high prevalence of hypertension in this population. To promote medication adherence among this group, we translated a behavioral intervention that improved adherence by 36% into a digital therapeutic self-management system. Design strategies included interviewing older adults, conducting usability evaluations after each iteration, and engaging a team of experts from nursing, cognitive psychology, pharmacy, human factors in aging, and software development. We outline our design process that can guide translation of other behavioral interventions into digital therapeutic platforms.

Keywords: mHealth, digital therapeutics, design for older adults, usability, test and evaluation, design strategies, health management, self-management, medication adherence, hypertension

Medication adherence is a complex, multifaceted self-management behavior (Gast & Mathes, 2019; Sabaté, 2003). Despite the negative health consequences associated with medication nonadherence, rates of nonadherence among individuals with hypertension are over 45% (Abegaz et al., 2017). Nonadherence to hypertension medications is associated with an increased risk for adverse outcomes including increased incidence of stroke, heart attack, and kidney disease (Burnier & Egan, 2019). These risks are proportionally higher among individuals age 65 or older, for whom poor adherence is associated with increased hospitalization rates and an increased risk of death (Burnier et al., 2020). Although the health and experience of older adults can vary, this group is more likely to experience complex health conditions and faces unique challenges, necessitating the need for strategies that support healthy aging behaviors (WHO, 2018).

Digital therapeutics are technology-based solutions that integrate digital and online technologies. They include mobile health (mHealth) applications, web portals, telehealth platforms, and sensor technology, and represent an emerging approach to supporting individuals managing chronic diseases (Khirasaria et al., 2020). Memory and attentional processes are crucial for prospective memory performance in tasks such as medication taking (Insel et al., 2015). Technology may be used to support these processes and thus increase adherence among older adults with hypertension. Designing technology for older adults requires consideration of their unique cognitive, physical, and motivational needs to ensure usability and promote effectiveness (Morey et al., 2019). We describe our process of designing and translating a successful behavioral intervention into a digital therapeutic self-management system to promote self-management of hypertension medications among older adults.

Foundations for System Development

Medication adherence requires individuals to develop and adapt a plan for adherence, encode the intention to take the medication, store this information, remember to take the medication at the correct time, execute the action of taking the medication, and continuously assess whether doses were taken as intended (Insel et al., 2006). Declines in response speed and memory are characteristics of age-associated cognitive change (Salthouse, 2019). Older adults are especially vulnerable to cognitive changes that impact the planning, monitoring, and execution of intentions that are required for self-management behaviors like medication adherence (McDaniel & Einstein, 2011).

Insel et al. (2006) found that executive function and working memory predicted medication adherence among a group of community-dwelling older adults taking commonly prescribed medications. This work informed a multifaceted prospective memory intervention to improve medication adherence among older adults with hypertension, by incorporating strategies into the intervention that relied on automatic associative processes rather than more effortful self-initiated cognitive processes such as executive function and working memory (Craik et al., 2018; Insel et al., 2016). Intervention strategies included education and imagining medication taking to further encode and store the intention through implementation intentions or action plans (Insel et al., 2016). Using the participant’s own daily schedule, we asked them to identify an event in their daily routine that could be associated with medication-taking. Hence, the cue to take medication was tailored to his/her own schedule (Insel et al., 2016). The intervention was tested with a randomized control trial using an active control condition where time and attention were equated between groups. Participants in the control group received the same educational information on hypertension and hypertension medications that was given to the participants in the intervention group (Insel et al., 2016). Significant improvements in medication adherence were observed in the intervention group, with mean adherence rising from 57% at baseline to 78% after the intervention (Insel et al., 2016). The participants that had lower executive function and working memory abilities achieved the greatest benefit. However, the gains achieved by participants gradually declined over another five months of continued adherence monitoring after cessation of the nurse visit component of the intervention (Insel et al., 2016). The lack of sustained benefit signaled a need for continued support and promotion of adherence strategies and led us to embark on translating the behavioral intervention into a digital therapeutic self-management system that incorporates the effective intervention components.

Translation of the Intervention to the MEDSReM© System

Our review of the usefulness and acceptability of commercially available medication adherence apps for use by older adults indicated that available technology solutions for self-care are not necessarily designed to address the needs of older adults, may not provide reliable information, may not be clinically evidence-based, and may not deliver visualizations that are informative and motivating for reminding or medication adherence (Blocker et al., 2017; Blocker et al., 2018; Stuck et al., 2017). These technology challenges can be remedied by attention to user-centered design via easier navigation, streamlined data entry, recovery from errors, and improved visualizations (Morey et al., 2019). To address these challenges, we formed an interdisciplinary team of experts from nursing, pharmacy, cognitive psychology, software development, gerontology, and human factors. Our goal was to effectively translate the multifaceted prospective memory intervention into a digital therapeutic self-management system that would improve and sustain medication adherence. An R21 exploratory/developmental grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (National Institutes of Health Grant R21NR016285) was used to initiate application development.

Structured Interviews

We began by conducting a comprehensive literature review on medication adherence among older adults, ultimately finding a paucity of research that examined medication adherence from the perspective of prospective memory performance. Survey data indicate that older adults rely on multiple cues and strategies to effectively take medications, and report forgetting to take their medications more often during unexpected activities or deviations from their normal routine (Boron et al., 2013). We conducted structured interviews with six older adults taking at least one prescribed medication for hypertension to investigate preferences related to technology systems that support hypertension medication management strategies. These data are reported in Blocker et al. (2018) but are briefly summarized here. The mean age of participants was 79.33 (SD 5.50) years, and 50% were male. This group was well-educated with all participants having attended at least some college. Five of the participants where White, one participant was Asian, and all were recruited from local community centers.

We asked participants to describe their health and experience managing their blood pressure, and their process for remembering to take their medications. We included questions about medication-taking routines, the use of reminders/alarms, organizational strategies, and scenario-based examples. Participants described their perceptions related to using technology to assist with medication adherence, specifically the method that would most easily integrate with their lifestyle, and their preference for built-in reminders and the presentation of information. Two members of the research team conducted a qualitative content analysis, which identified themes that included overall positive intentions related to medication-taking, challenges with routine changes, and the desire for easy-to-access information about their specific medications. These interviews provided valuable insights into educational, decision-making, reminder, and monitoring needs, which ultimately informed the first iteration of the Medication Education, Decision Support, Reminding, and Monitoring (MEDSReM©) system. We then conducted a focus group with the participants who had participated in the structured interviews, wherein feedback was elicited, and users were asked to give their perspectives on the proposed system.

MEDSReM© System Components

Figure 1 includes examples of the wireframes that were created for the first iteration of MEDSReM. Once the participant’s hypertension medications were loaded into the medication list, an individualized reminder schedule could be created, linking medication taking with the participant’s preferred daily activities. The features of MEDSReM were designed to incorporate the successful components from the multifaceted prospective memory intervention, which included relationship building, education, action plan development, tailoring medication taking to individual routines, linking medication taking to events rather than time, calling attention to the action of taking the medication and enhancing the ability to monitor if the medication was taken as intended (Insel et al., 2016). MEDSReM also features educational information about hypertension and hypertensive medications, along with links to credible sources. Decision support was built into MEDSReM to provide support to older adults who missed taking a dose during the designated time window for safety. Using the pharmacology of aging principles, we developed a medication-based algorithm to provide specific guidance for the older adult regarding whether to take the missed dose or wait until the next scheduled dose, supporting adherence and reducing risk. Participants could monitor their adherence over time and view a calendar that depicted their historical medication adherence, providing motivation that can improve adherence long-term (illustrated on the right side of Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MEDSReM© wireframes

Note. Examples of the wireframes that were created for MEDSReM to connect medication-taking with a routine from the participant’s daily schedule.

Usability Testing

We recruited six older adults who were at least 65 years of age, spoke English, and took one or more medication for high blood pressure. Recruitment occurred at community centers that served different socioeconomic and geographic areas. None of the participants from the previous intervention or structured interviews were included. If participants were identified as having suspected dementia on the Mini-Cog Assessment (Borson et al., 2003) they would have been excluded from participation. The measures listed in Table 1 were used to describe the sample. Participants were individually invited into a private conference room where one human factors expert and one note-taker observed participant challenges as each older adult navigated the MEDSReM screens on the smartphone. We limited the number of people in the room during the usability testing to foster a less stressful and non-intimidating environment. A camera, focused on the participant’s hands, was used to record their interaction with the mobile device. This video feed along with audio from the interaction was streamed into a larger conference room where additional researchers and software developers were observing and taking relevant notes. Participants were asked to explore the MEDSReM system and to perform certain tasks. Following this interaction, participants evaluated the system’s usability and completed a feedback questionnaire, and a post interaction interview.

Table 1.

Assessment Measures

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Demographics Questionnaire (locally developed)a, b | General measure to obtain background information on each user. |

| Telephone Executive Assessment (TEXAS) Questionnaire (Royall et al., 1992)a, b | Executive function assessment |

| Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (Roque & Boot, 2018)a, b | Assessment of mobile device proficiency, including the ability to perform certain tasks. |

| Values and Beliefs Questionnaire (locally developed)a, b | Measure that assesses beliefs about blood pressure and blood pressure medications. |

| System Usability Scale (Brooke, 1996)a | Brief usability measure that provides an evaluation of the overall usability of a system. |

| App Feedback Questionnaire (locally developed)a | Assessment of user perceptions of the mobile health application component of MEDSReM. |

Included in usability testing

Included in field trial

Results from the usability testing revealed design insights, reminder preferences, and general positive opinions regarding technology use for medication management. A qualitative analysis of the usability testing transcripts revealed that the responses largely corresponded with the themes identified by Blocker et al. (2018) during qualitative content analysis of the structured interviews. Table 2 provides direct quotes from the participants that were used to inform modifications of the MEDSReM system.

Table 2.

Quotes from Usability Testing

| Usefulness to Support Medication Adherence | “I think it is helpful for people that need help taking their medications.” “When you’re on vacation or away from your routine, it’s very easy to forget to take something or get on a different schedule.” “My blood pressure medication routine is pretty much set, but for someone who takes it at night might need it. The morning routine is pretty set, but as the day goes on, you can forget. Especially for older people.” |

| Design Insights and Information Presentation | “It’s very clear. Nicely laid out.” “If I have high blood pressure and I’m taking readings periodically at home, is there any way that the readings can be fed in?” “It might be easier to see if the background was darker. And that would make the numbers show more.” |

| Reminder and Monitoring Preferences | “…the history of how well I’m doing is a check that I’ve never had before.” “If it had the alert thing it would help me remember. Usually I don’t have trouble, but I did for the night dose 3 days ago. I just plain forgot. So there was the pill the next morning.” “When the phone goes off, it’s time to take your medication. You can see a pattern. Now, if I had to take it morning and evening, that would be a new pattern for me.” |

| Education Preferences and Perceived Knowledge | “There is a lot of information and for people that want that kind of information, it’s good.” “It isn’t all right there to overwhelm you. It’s available so you can get it, but it doesn’t overwhelm you.” “High blood pressure or how to change my lifestyle about blood pressure, I would not do it on my phone – I would do it somewhere where I would sit down and read about it.” “If my blood pressure is not under control, that would be vital information.” |

This usability feedback resulted in design changes including color gradient modifications, for example, using higher contrast colors instead of the yellow on white originally used in the calendar visualization of adherence history. This feedback also resulted in the incorporation of a back button, and clearer, more consistent terminology to guide tasks. Some participants voiced interest in having a description of the pills built within the system to assist with recognition. We ultimately excluded this as it would have required information about the medication manufacturer, which changes frequently depending on pharmacy contracts. Participants also voiced a desire to have blood pressure integration within the system, and a desire to have access to educational information via a web-based portal, which are planned for a future iteration of MEDSReM.

Field Testing

The feedback from structured interviews and usability testing guided modifications of the MEDSReM system and allowed us to address usability challenges that threatened the effectiveness of the system for use with older adults. We then field-tested MEDSReM using a pre and post within-subjects design. We recruited 26 older adults taking at least one medication for hypertension. Recruitment occurred at community centers that served different socioeconomic and geographic areas, and no participants were included that had participated in the behavioral intervention or previous phases of MEDSReM testing. Those with Parkinson’s disease or who reported a past stroke were excluded. Those identified as having severe depression on the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) (Yesavage et al., 1982) or suspected dementia on the Mini-Cog Assessment (Borson et al., 2003) were also excluded. Demographic and background information were collected, and participants were screened for near vision prior to enrollment using the Snellen Eye Chart, to ensure that visual deficits would not interfere with their ability to use the system. Participants also completed the TEXAS measure of executive function (Royall et al., 1992) and Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (Roque & Boot, 2018).

Participant visits during the field test were conducted by investigators and research staff who had gerontology experience. Adherence was monitored for four weeks using the Medication Event Monitoring System MEMS® caps (MEMS 6: Medication Event Monitoring System, 2015). MEMS® caps are one form of electronic medication adherence monitoring wherein microcircuitry is incorporated into the cap of the medication bottle, with bottle opening time acting as a valid and reliable indicator of when the participant actually took the medication (Vrijens & Urquhart, 2014). We included a 4-week run-in period in which adherence was monitored but no intervention was performed, and participants were blinded to the results of the MEMS® data downloads.

The data on medication adherence, measured using MEMS® caps, was used to determine intervention eligibility. Only participants identified as nonadherent (adherence of less than or equal to 86%) during the last two weeks of the baseline monitoring period were invited to participate in the MEDSReM intervention. We excluded individuals from participating in the intervention if they were classified as adherent to avoid a ceiling effect.

Nine participants initially qualified to test the MEDSReM system, however two declined. One of the two participants declined due to frustration with using a smartphone, and the other stated that she was too busy to create a medication schedule for adherence. Demographic characteristics for the participants who advanced to field testing are in Table 3. During the first intervention visit, we provided participants with Apple® smartphones that were loaded with the MEDSReM system and offered training for how to use it. An additional visit occurred at 1 week to address questions and to ensure use of MEDSReM. Five weeks post intervention we returned to pick up the smartphone, the MEMS® cap and to talk with the participant about the experience. The final visit allowed for four weeks of post-intervention adherence monitoring.

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Usability and Field Testing

| Demographic Characteristic | Usability Testing (n = 6) Mean (SD) or Score/Frequency |

Field Testing (n = 7) Mean (SD) or Score/Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Average Age | 83 years (5.4) | 74.9 years (6.9) |

| Age Range | 75–90 years | 65–84 years |

| Gender | ||

| Male | n = 3 | n = 3 |

| Female | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Education | ||

| Some College | n = 1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | n = 1 | n = 2 |

| Graduate degree | n = 5 | n = 4 |

| Occupation | ||

| Retired | n = 6 | n = 7 |

| Race | ||

| White | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| Native American | n = 1 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | n = 3 | n = 1 |

| Married | n = 1 | n = 3 |

| Widowed | n = 2 | n = 3 |

| Systolic blood pressure at baseline (sitting) | 117 mmHg (28.8) | |

| Diastolic blood pressure at baseline (sitting) | 74 mmHg (13.6) | |

| Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) (Yesavage et al., 1982) | ||

| Total Scorea | 0 (n = 1) | |

| 1 (n = 4) | ||

| 2 (n = 2) | ||

| Telephone Executive Assessment (TEXAS) Questionnaire (Royall et al., 1992) | ||

| Total Scoreb | 0 (n = 2) | 0 (n = 3) |

| 1 (n = 4) | 1 (n =2) | |

| 2 (n = 2) | ||

| Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (MDPQ-16) Total Scorec | ||

| <10 | n = 1 | |

| 10–20 | n = 0 | |

| 21–30 | n = 4 | n = 3 |

| >31 | n = 1 | n = 4 |

| System Usability Scale (Brooke, 1996) Total Score | ||

| 60–70 | n = 1 | |

| 71–80 | ||

| 81–90 | n = 2 | |

| 91–100 | n = 3 |

A score > 5 points is suggestive of depression.

Range is from 0–10 with higher scores indicating greater executive function impairment.

Higher scores indicate higher proficiency.

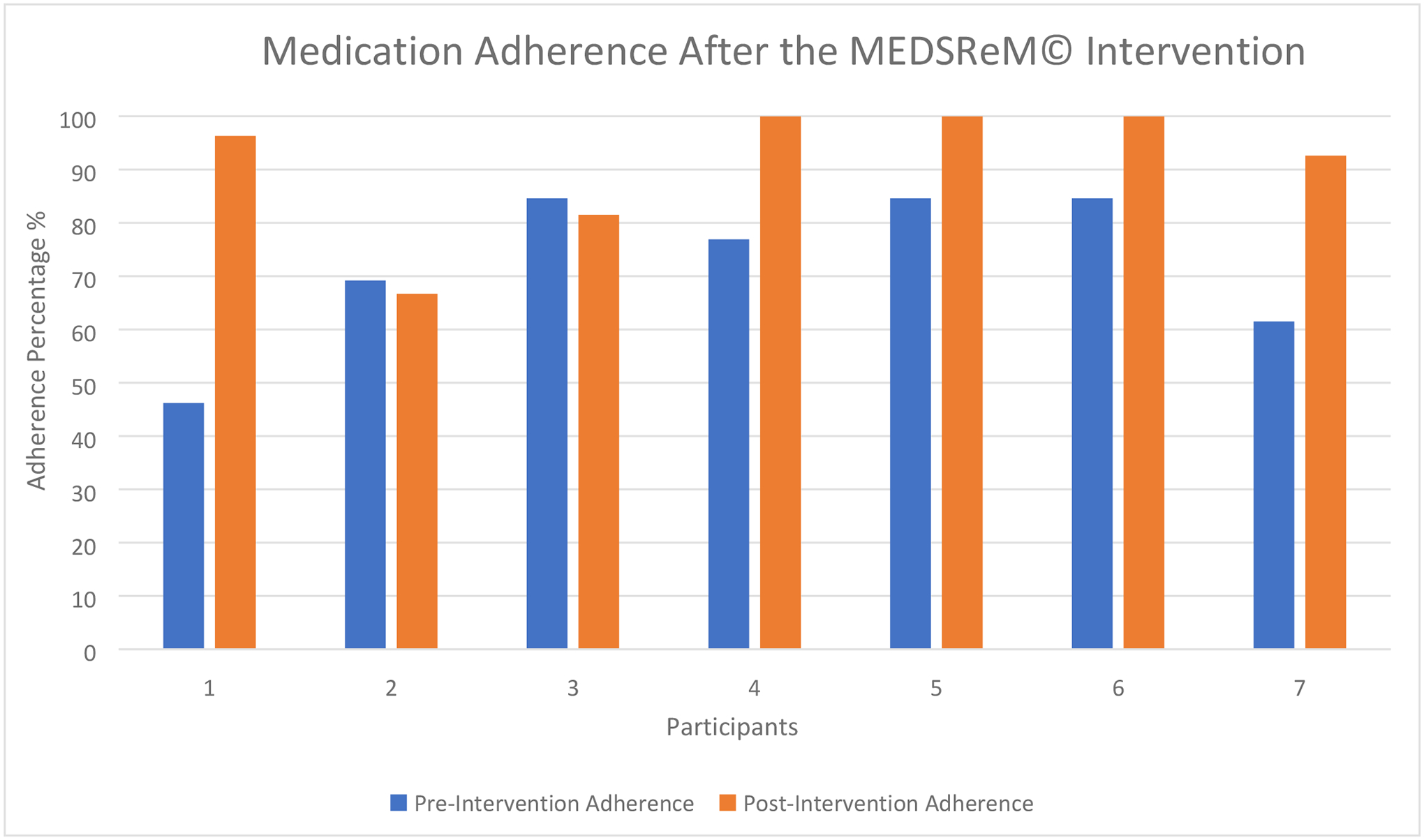

Figure 2 illustrates each participant’s medication adherence at baseline and after MEDSReM system use. Data analysis determined that overall medication adherence among the participants increased from a baseline adherence of 72.5% (SD 14.6) to a post-intervention medication adherence of 91.0% (SD 12.6); a paired t test indicated this was statistically significant (p = 0.04). In the exit interviews, participants described the visualizations and colors of MEDSReM as helpful, especially the calendar representation of their adherence rates over time. The participants classified the reminder/scheduling function as the best part of MEDSReM, preferring the system’s approach to medication scheduling, which included coupling medication taking with an already established routine in their daily schedule, such as drinking coffee or brushing their teeth, rather than a defined time. The least liked aspects included slow loading times between screens, the “undo” prompt on the medication entry screen, reminder tones being too quiet, and the lack of an Android™ version of the system. Participants reported it would be helpful if MEDSReM included a place to record blood pressure readings and other medications. Additionally, some participants would have liked the ability to increase the loudness of the reminder tones from within the mHealth application, rather than in the phone’s settings. Participants also wanted to be able to mute or snooze a reminder, but still receive an additional prompt a few minutes later. In general, all participants thought the system would be useful for themselves or other people they knew.

Figure 2.

Medication adherence rates before and after the MEDSReM© Field Test

Note. Each participant from the field test is represented. Adherence was measured using MEMS® caps and was defined as the percent of doses on schedule, with both the baseline and post-intervention adherence rates displayed. Mean overall adherence increased from 72.5% (SD 14.6) to 91.0% (SD 12.6), representing a statistically significant improvement (p=0.04).

Lessons Learned and Design Recommendations

Our goal was to develop a digital therapeutic self-management system that would translate the benefits of the multifaceted prospective memory intervention that improved medication adherence among older adults taking hypertension medications (Insel et al., 2016). This system supports older adults’ adherence to hypertension medications by incorporating components that include education, decision support, reminding, and monitoring. MEDSReM incorporates several efficacious prospective memory strategies, building upon the successful behavioral intervention from Insel et al. (2016). MEDSReM facilitates changing medication taking from an effortful process dependent on cognitive processes that may decline with age, to customized and cue-driven associative processes that are preserved with age, incorporating additional support for making decisions about missed doses.

Technology interventions designed for older adults require special consideration for their broad range of technology experiences (Czaja et al., 2019). For example, even though our system was specifically designed to accommodate older adults’ perceptual and cognitive capabilities, instructional support was still required. It’s also important to note that two participants did decline the intervention, hence the system may only be valuable for those older adults that are open to both applying new strategies to support medication adherence and to using digital technologies. Moreover, we did observe some trepidation on the part of older adults about using an app on a smartphone, and training about basic phone controls might also be required (e.g., downloading apps, controlling volume). Nevertheless, smartphone adoption is increasing for older adults (Anderson & Perrin, 2017). Digital therapeutic systems have tremendous potential to augment care networks and enable health self-management. With instructional support, and an age-friendly design, this potential might be realized.

The formulation of an interdisciplinary team that was involved in all elements of system development represents a strength of our design process that is recommended for other teams that seek to design and/or test digital therapeutic self-management systems. Specifically, the expert in nursing educated the software development team about the intervention components needed to replicate the nurse-based intervention into a digital therapeutic self-management system. The pharmacy expert developed components of the integrated decision support based on pharmacology of aging principles. The human factors experts designed and implemented user testing and assisted with technology design throughout system development. The nurse and pharmacist recruited participants through community health centers where they routinely provided educational sessions to older adults and thus had established collaborative relationships with the leadership of the centers.

The inclusion of older adult stakeholders at multiple phases of the design process allowed us to identify their unique needs and to design the system to meet the needs of older adults and support their adherence. This was especially evident during the usability testing, which used cameras and video streaming technology to creatively view and collaborate with the older adult participant while also providing privacy and a comfortable environment for their exploration of the system.

Next steps will include advancing the design of the MEDSReM system to implement new functionalities including electronic blood pressure self-monitoring, expanded decision support, and an online portal. User testing the advanced MEDSReM system with iterative enhancement will occur prior to determining the efficacy and scalability of the system through a randomized control trial. Incorporating a larger, more diverse sample during the next phase of testing will be important, as the previous usability and field test samples were comprised of predominately White, well-educated users. The use of a randomized control trial design will ensure that improvements in medication adherence can be attributed to the MEDSReM system, and not confounding variables. Employing the methodological strategies that we have outlined may be necessary when designing and building a digital therapeutic system that seeks to address the unique needs of older adult users and strives to promote and support sustained behavior change.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (National Institutes of Health Grant R21NR016285). The authors thank Tracy Mitzner, Gilles Einstein, Dan Morrow, Kari Koerner Marano, Jennifer Skye Nicholas, and the Ephibian, Inc. software development team for their contributions to this system.

Biographies

Stacy A. Al-Saleh is a PhD candidate in nursing at the University of Arizona. Her research interests include the use of technology to promote self-management behaviors among individuals with chronic diseases and the implications of technology on health disparities. Her current research explores medication adherence behaviors among organ transplant recipients. sakuchar@email.arizona.edu.

Jeannie K. Lee, PharmD, BCPS, BCGP, FASHP is Assistant Dean of Students and Associate Professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice & Science at the University of Arizona (UA) College of Pharmacy. She is also Clinical Associate Professor in the Division of Geriatrics, General Internal Medicine & Palliative Medicine at the UA College of Medicine, and research associate in the Arizona Center on Aging. She practices interprofessionally at the Banner University Medical Center Geriatrics Clinic.

Wendy A. Rogers, Ph.D., is Khan Professor of Applied Health Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She is a Certified Human Factors Professional (BCPE #1539). She is Director of the McKechnie Family LIFE Home and the Health Technology Education Program; Program Director of CHART (Collaborations in Health, Aging, Research, & Technology); and Director of the Human Factors and Aging Laboratory. Her research interests include design for aging; technology acceptance; human-robot interaction; and training.

Kathie Insel, PhD, RN, is a Professor and Chair of the Biobehavioral Health Science Division in the College of Nursing, University of Arizona. She is the owner of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center sub-initiative “Next Generation Model of Health Aging.” Her research focuses on cognition and its influence on self-management of chronic conditions among older adults including interventions to support self-management, and translation of these interventions to digital therapeutics for widespread dissemination.

Footnotes

Apple is a trademark of Apple Inc. Android is a trademark of Google LLC.

Contributor Information

Stacy Al-Saleh, University of Arizona..

Jeannie Lee, Department of Pharmacy Practice & Science at the University of Arizona (UA) College of Pharmacy.; Division of Geriatrics, General Internal Medicine & Palliative Medicine at the UA College of Medicine, Arizona Center on Aging, Banner University Medical Center Geriatrics Clinic.

Wendy Rogers, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. McKechnie Family LIFE Home and the Health Technology Education Program; Program Director of CHART (Collaborations in Health, Aging, Research, & Technology); Human Factors and Aging Laboratory.

Kathleen Insel, Biobehavioral Health Science Division in the College of Nursing, University of Arizona.; University of Arizona Health Sciences Center sub-initiative “Next Generation Model of Health Aging.”

References

- Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, & Elnour AA (2017). Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 96(4), e5641. 10.1097/md.0000000000005641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Perrin A (2017). Technology use among seniors. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/technology-use-among-seniors/ [Google Scholar]

- Blocker KA, Insel KC, Koerner KM, & Rogers WA (2017). Understanding the Medication Adherence Strategies of Older Adults with Hypertension. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 61(1), 11–15. 10.1177/1541931213601498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker KA, Insel KC, Lee JK, Nie Q, Ajuwon A, & Rogers WA (2018). User Insights for Design of an Antihypertensive Medication Management Application. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 62(1), 1077–1081. 10.1177/1541931218621247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron JB, Rogers WA, & Fisk AD (2013). Everyday memory strategies for medication adherence. Geriatric nursing (New York), 34(5), 395–401. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, & Ganguli M (2003). The Mini-Cog as a Screen for Dementia: Validation in a Population Based Sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 51(10), 1451–1454. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke J (1996). SUS- A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability evaluation in industry (pp. 189–194). [Google Scholar]

- Burnier M, Polychronopoulou E, & Wuerzner G (2020). Hypertension and Drug Adherence in the Elderly. Front Cardiovasc Med, 7, 49. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnier MM, & Egan MB (2019). Adherence in Hypertension: A Review of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Impact, and Management. Circulation Research, 124(7), 1124–1140. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik FIM, Eftekhari E, Bialystok E, & Anderson ND (2018). Individual differences in executive functions and retrieval efficacy in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 33(8), 1105–1114. 10.1037/pag0000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Boot WR, Charness N, & Rogers WA (2019). Designing for Older Adults: Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches (3 ed.). CRC Press. 10.1201/b22189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gast A, & Mathes T (2019). Medication adherence influencing factors-an (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev, 8(1), 112. 10.1186/s13643-019-1014-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel, Einstein GO, Morrow DG, Koerner KM, & Hepworth JT (2016). Multifaceted Prospective Memory Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(3), 561–568. 10.1111/jgs.14032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel K, Lee JK, Einstein GO, & Morrow DG (2015). Opportunities for Technology: Translating an Efficacious Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence Among Older Adults. In (pp. 82–88). Cham: Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-20913-5_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insel K, Morrow D, Brewer B, & Figueredo A (2006). Executive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(2), P102–107. 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khirasaria R, Singh V, & Batta A (2020). Exploring digital therapeutics: The next paradigm of modern health-care industry. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 11(2), 54–58. 10.4103/picr.PICR_89_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, & Einstein GO (2011). The neuropsychology of prospective memory in normal aging: A componential approach. Neuropsychologia, 49(8), 2147–2155. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEMS 6: Medication Event Monitoring System. (2015). Aardex Corp. https://www.aardexgroup.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Morey SA, Stuck RE, Chong AW, Barg-Walkow LH, Mitzner TL, & Rogers WA (2019). Mobile Health Apps: Improving Usability for Older Adult Users. Ergonomics in design, 27(4), 4–13. 10.1177/1064804619840731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roque NA, & Boot WR (2018). A New Tool for Assessing Mobile Device Proficiency in Older Adults: The Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(2), 131–156. 10.1177/0733464816642582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royall DR, Mahurin RK, & Gray KF (1992). Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40(12), 1221–1226. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté E (2003). Adherence to long-term therapies evidence for action. Geneva: : World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA (2019). Trajectories of Normal Cognitive Aging. Psychology and Aging, 34(1), 17–24. 10.1037/pag0000288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck RE, Chong AW, Tracy LM, & Rogers WA (2017). Medication Management Apps: Usable by Older Adults? Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 61(1), 1141–1144. 10.1177/1541931213601769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B, & Urquhart J (2014). Methods for Measuring, Enhancing, and Accounting for Medication Adherence in Clinical Trials. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 95(6), 617–626. 10.1038/clpt.2014.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, & Leirer VO (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37–49. 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]