Abstract

Type-I interferons (IFN-I) are critical mediators of innate control of viral infections, but also drive recruitment of inflammatory cells to sites of infection, a key feature of severe COVID-19. Here, IFN-I signaling was modulated in rhesus macaques (RMs) prior to and during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection using a mutated IFNα2 (IFN-modulator; IFNmod), which has previously been shown to reduce the binding and signaling of endogenous IFN-I. IFNmod treatment in uninfected RMs was observed to induce a modest upregulation of only antiviral IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs); however, in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs, IFNmod reduced both antiviral and inflammatory ISGs. Notably, IFNmod treatment resulted in a potent reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral loads both in vitro in Calu-3 cells and in vivo in Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), upper airways, lung, and hilar lymph nodes of RMs. Furthermore, in SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs, IFNmod treatment potently reduced inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and CD163+MRC1- inflammatory macrophages in BAL and expression of Siglec-1 on circulating monocytes. In the lung, IFNmod also reduced pathogenesis and attenuated pathways of inflammasome activation and stress response during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using an intervention targeting both IFN-α and IFN-β pathways, this study shows that, while early IFN-I restrains SARS-CoV-2 replication, uncontrolled IFN-I-signaling critically contributes to SARS-CoV-2 inflammation and pathogenesis in the moderate disease model of RMs.

One Sentence Summary:

Administration of a mutated IFNα2 to rhesus macaques limited viral replication and pathogenesis during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is an ongoing pandemic that has resulted in over 6.9 million cumulative deaths (1, 2). While vaccines are highly effective, vaccine-induced immunity and neutralizing antibody titers wane over time. In addition, the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants resulting in breakthrough infections remains worrisome. Thus, it is imperative to fully characterize the viral pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and early COVID-19 immune responses to identify correlates of protection and design therapeutics that can mitigate disease severity and viral replication.

Type-I interferons (IFN-I) are ubiquitously expressed cytokines that play a central role in innate antiviral immunity and cell-intrinsic immunity against viral pathogens (3–5). The receptors for IFN-I, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, are universally expressed and, following formation of the IFN-I ternary complex, trigger the downstream transcription of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) that mediate a myriad of antiviral effector functions and promote recruitment of inflammatory cells (6). Work early in the pandemic indicated that the IFN-I system has a protective effect from disease in SARS-CoV-2 infection, as individuals with severe COVID-19 were demonstrated to be more likely to have deficiencies to IFN-I responses, either by the presence of rare inborn errors (TLR3, IRF7, TICAM1, TBK1, or IFNAR1), neutralizing auto-antibodies against IFN-I, or the lack of production of IFN-I (7–16). Additionally, Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) of critically ill COVID-19 patients have identified multiple critical COVID-19-associated variants in genes that are involved in IFN-I signaling including IFNA10, IFNAR2, TYK2, as well as type III interferon signaling IL10RB (17). These findings contributed to the establishment of a model in which sustained IFN-I responses were deemed to be critical for protecting SARS-CoV-2-infected patients from progressing to severe COVID-19.

However, more recent work has suggested that the role of the IFN-I system in SARS-CoV-2 infection may be more complex than initially thought. In contrast to the aforementioned studies, Povysil et al. found no associations between rare loss-of-function variants in IFN-I and severe COVID-19 (18). Further, Lee et al. demonstrated that hyper-inflammatory signatures characterized by IFN-I response in conjunction with TNF/IL-1β were associated with severe COVID-19 in SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals (19) and Blanco-Melo et al. showed that high IFN-I expression in the lung was linked to increased morbidity early in the COVID-19 pandemic (20). Additionally, prolonged IFN signaling in murine models of respiratory infection has recently been shown to interfere with repair in lung epithelia, increasing disease severity and susceptibility to bacterial infections (21, 22) and blocking IFN-I with anti-IFNAR2 antibodies has been shown to suppress inflammation in SARS-CoV-2-infected MISTRG6-hACE2 mice when combined with remdesivir (23).

In the past year, progress has been made in characterizing the underlying mechanisms of IFN-I mediated pathogenesis in SARS-CoV-2 infection. For example, pro-inflammatory monocytes (CD14+ CD16+) that can be driven to expand by IFN-I have been shown by Junqueira et al. and Sefik et al. to phagocytose antibody-opsonized SARS-CoV-2 via FCγRs, undergo abortive infection, and induce pyroptosis that results in systemic inflammation (23, 24). Additionally, Laurent et al. demonstrated that pDCs infiltrate into the lungs of COVID-19 patients and IFN-I produced by pDCs in response to SARS-CoV-2 results in transcriptional and epigenetic changes in macrophages that prime them for hyperactivation in vitro; these findings support a model in which pDCs that infiltrate into the lungs directly sense SARS-CoV-2 and produce IFN-I that prime lung macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines (25).

Further work also has demonstrated the association of multiple ISGs with increased SARS-CoV-2 infection. Specifically, interferon-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITM 1–3) have been shown to be commandeered by SARS-CoV-2 to increase efficiency of viral infection (26), the IFN-I-inducible receptor sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 1 (Siglec-1/CD169) can function as an attachment receptor and enhances ACE2-mediated infection and induction of trans-infection (27), and aberrant cGAS-STING activation has not only been found in the severely damaged lungs of COVID-19 patients post-mortem but has also been detected in macrophages surrounding damaged epithelial cells in COVID-19 skin lesions (28).

Several ongoing and recently completed clinical trials administering IFN-I have shown little to no positive effects of therapy during acute infection, despite treatment with IFN being highly efficient against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro (29, 30). No beneficial effects were observed with either IFNβ−1a or combination IFNβ−1a and remdesivir treatment in hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the WHO Solidarity Trial and Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT-3) respectively. In fact, combination IFNβ−1a and remdesivir resulted in worse outcomes and respiratory status in ACTT-3 patients who required high-flow oxygen at baseline when compared to treatment with remdesivir alone (31). Pegylated IFN-α2b has shown some promise in moderate COVID-19 patients, with a phase 3 randomized open label study showing that patients that received pegylated IFN-α2b experienced a faster time to viral clearance (32). Recently, there has been renewed interest in pursuing IFN-λ as a COVID-19 therapeutic following completion of the Phase 3 TOGETHER clinical trial which demonstrated that early administration of pegylated IFN-λ resulted in a 51% risk reduction of COVID-19-related hospitalizations or emergency room visits in predominantly vaccinated individuals at high risk of developing severe COVID-19 (33).

Given the discordant effects of IFN treatment observed in the aforementioned trials and the contradictory findings of IFN-I having a protective or detrimental role in COVID-19, it is critical that further research on the mechanisms of IFN-I in regulating SARS-CoV-2 infection is conducted.

Non-human primate (NHP) models, specifically rhesus macaques (RMs), have been used extensively to study pathogenesis and evaluate potential vaccine and antiviral candidates for numerous viral diseases, including HIV and, more recently, SARS-CoV-2 (34–37). RMs infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop mild to moderate disease, mimic patterns of viral shedding, and, in similar fashion to humans, rarely progress to severe disease (34–37). Multiple previous studies (34–37) have shown that RMs generate a rapid and robust IFN-I response following SARS-CoV-2 infection, with numerous ISGs upregulated as early as 1 day post-infection (dpi) in both peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bronchiolar lavage (BAL).

To better understand how downregulating this early IFN-I response in SARS-CoV-2-infection may impact viral replication and pathogenesis in the RM model, we used a mutated IFNα2, here named IFN-I modulator (IFNmod), which binds with high affinity to IFNAR2, but markedly lower affinity to IFNAR1, with a net effect of reducing the binding and signaling of all forms of endogenous IFN-I (38–40), and, as such, previously referred to as IFN-I competitive antagonist (IFN-1ant). IFNmod has been shown to induce low-level stimulation of robust antiviral ISGs without induction of tunable inflammatory genes when used in vitro in cancer cell lines (38, 39). Importantly, IFNmod has previously been evaluated in vivo in RMs where it was shown to possess a short plasma half-life, allowing us to modulate IFN-I signaling specifically in the early stages of infection, and has been shown to limit the expression of both antiviral and pro-inflammatory ISGs in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV)-infected RMs (40, 41). Using an intervention targeting both IFN-α and IFN-β pathways in the moderate disease model of SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs, our data support a model where early IFN-I restrains viral replication, while uncontrolled IFN-I-signaling contributes to SARS-CoV-2 inflammation and pathogenesis.

RESULTS

IFNmod treatment in uninfected RMs modestly upregulated antiviral ISGs without impacting inflammatory genes

We administered IFNmod to four uninfected RMs at a dose of 1 mg/day, intramuscularly, for 4 consecutive days (Fig. 1a, Table S1) to determine its impact on ISGs in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Transcript levels of a panel of 16 ISGs previously observed to be induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection (34) in RMs were quantified by RNAseq at pre- and post-treatment timepoints. Similar to what was previously observed in cancer cells treated with IFNmod (38, 39), antiviral ISGs were modestly upregulated following IFNmod administration in both the BAL and PBMCs of uninfected RMs (Fig. 1b-c) whereas IL-6 signaling and inflammatory genes remained unchanged (Fig. 1d-e). Previously, Forerro et al. identified that proinflammatory gene expression triggered by Type I IFNs was largely dependent on the selective induction of the transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) (42). In concordance with the unchanged inflammatory gene expression, we did not observe any induction of IRF1 in BAL or PBMCs of uninfected, IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 1f). Additionally, IFNmod treatment in uninfected animals did not impact BAL cytokines and chemokines associated with inflammation and recruitment of inflammatory cells including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12p40, TNFβ, IFNγ, MIP1α, and MIP1β (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1. Administration of IFNmod in uninfected RMs resulted in modest upregulation of ISGs without changes to inflammatory genes or inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

(a) Study design of IFNmod treatment in uninfected RMs; 1mg IFNmod was administered intramuscularly to n=4 uninfected RMs (7–10 years old, median = 9.5 years) for four consecutive days. Blood and BAL were collected at pre-treatment baseline (3 days before treatment initiation) and once a day from days 1–3 post treatment initiation, with the exception of day 2 post treatment initiation, where only blood was collected. Heatmaps of ISG expression in (b) BAL and (c) PBMC of uninfected RMs before and after IFNmod treatment. Heatmaps of genes associated with IL-6 signaling and inflammation in (d) BAL and (e) PBMC of uninfected RMs before and after IFNmod treatment. (f) Distribution of log2 fold-changes of IRF1 relative to pre-treatment baseline (−3d tx). Filled dots represent the mean, and lighter dots are individual data points. (g) Fold change of cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid relative to pre-treatment baseline (−3d tx) measured by mesoscale. Statistical analyses for mesoscale analysis were performed using one-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Each black, open symbol represents an uninfected RM. Black lines represent median fold change. Gray-shaded boxes indicate that timepoint occurred during IFNmod treatment. The color scale depicted in the top right of panel c indicates log2 expression relative to the mean of all samples and is applicable to panels b-e.

Administration of IFNmod in Calu-3 human lung cells modulated IFN-I responses and inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication to levels comparable to Nirmatrelvir

Consistent with the data in uninfected RMs, IFNmod treatment alone in uninfected Calu-3 human lung cancer cells induced low-level expression of antiviral ISGs OAS1 and Mx1, with very minimal changes in the pro-inflammatory chemokine CXCL10 (Fig. 2a-c). In the presence of IFNα stimulation, IFNmod inhibited expression of both antiviral ISGs (OAS1, Mx1) and the pro-inflammatory CXCL10 (Fig. 2b-c). Taken together, these data indicate that IFNmod stimulates a weak antiviral IFN-I response in the absence of endogenous IFNα, but potently inhibits both antiviral and pro-inflammatory IFN-I pathways induced in response to addition of IFNα.

Fig. 2. Administration of IFNmod in Calu-3 human lung cells modulated type I IFN responses and inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication to levels comparable to Nirmatrelvir.

(a) Overview of uninfected Calu-3 cell culture setup with IFNmod (0.004, 0.04, and 0.4 µg/ml) +/− IFNα (0.04 µg/ml) treatment. mRNA fold induction of (b) antiviral genes OAS1 and Mx1 and (c) inflammatory gene CXCL10 in Calu-3 cells following IFNmod (0.004, 0.04, or 0.4 µg/ml) +/− IFNα (0.04 µg/ml) treatment from three independent Calu-3 experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests comparing IFNmod +/− IFNα treated samples to the respective no IFNmod controls. (d) Overview of Calu-3 SARS-CoV-2 cell culture setups with IFNmod (0.004, 0.04, and 0.4 µg/ml), IFNα (20, 100 and 500 IU/ml), or Nirmatrelvir (0.1, 1, and 10µM) treatment initiated pre-infection. (e) Viral N RNA copies/mL quantified by qRT-PCR and (f) normalized relative to the no treatment condition (N= 3 +/− SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests comparing untreated to IFNmod-treated samples. mRNA fold induction of (g) antiviral gene OAS1 and (h) inflammatory gene CXCL10 in SARS-CoV-2-infected Calu-3 cells following IFNmod (0.004, 0.04, or 0.4 µg/ml), IFNα (20, 100 and 500 IU/ml), or Nirmatrelvir (0.1, 1, and 10µM) treatment that was initiated pre-infection relative to untreated, uninfected controls. Statistical analyses were performed using ordinary ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test comparing untreated, infected samples to treated, infected samples. * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value <0.0001.

Given the ability of IFNmod to upregulate antiviral genes in both uninfected RMs and Calu-3 cells, its capacity to limit SARS-CoV-2 replication was explored (Fig. 2d). IFNmod was shown to be just as effective as IFNα and the antiviral Nirmatrelvir (packaged with Ritonavir and sold under the brand name Paxlovid) in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection when treatment was initiated prior to infection (Fig. 2e-f). With this reduced viremia, the expression of OAS1 relative to untreated SARS-CoV-2-infected Calu-3 cells was reduced at all tested concentrations of IFNmod and Nirmatrelvir, but not with the highest tested dose of IFNα (Fig. 2g). As expected, since viral RNA load was the key driver of inflammation in this in vitro model, we observed a potent reduction in CXCL10 mRNA with all three treatments (Fig. 2h). We also performed the same experiment with interventions started post-infection (Fig. S1a); although all 3 treatments potently reduced viral loads, in this setting Nirmatrelvir and IFNα were slightly more potent than IFNmod at the lowest tested concentrations (Fig. S1b-c). At the highest tested doses, there was a trend towards higher CXCL10 mRNA levels with IFNα treatment vs. IFNmod treatment (Fig. S1d), despite similar viral loads, suggesting that uncontrolled IFN-I-signaling contributes to SARS-CoV-2 inflammation.

IFNmod administration decreases SARS-CoV-2 loads in airways of RMs

Since IFNmod treatment resulted in inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro and low-level stimulation of antiviral genes without induction of inflammatory genes in uninfected RMs, we then tested the hypothesis that treatment with IFNmod may inhibit viral replication in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs while limiting systemic inflammation within the host. 18 adult RMs were age and sex matched between two experimental arms to receive 4 doses of IFNmod (intramuscularly, 1 mg/day; IFNmod-treated group) mimicking the 4-day dosing regimen of the uninfected RMs, or to remain untreated (untreated group). To determine how downregulating early IFN-I pathways affects SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenesis in vivo, animals assigned to the IFNmod-treated group initiated treatment at one day prior to infection (d-1) to allow for IFNmod distribution, binding to the IFNR, and early blocking of endogenous IFN-I and continued daily treatment until 2 days post-infection (dpi) (Fig. 3a). On day 0, all 18 RMs were inoculated with a total of 1.1×106 PFU SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV/USA-WA1/2020), administered by intranasal (IN) and intratracheal (IT) routes. Three IFNmod and 3 untreated RMs were euthanized at 2, 4, and 7 dpi each, respectively. Animals were scored according to the Coronavirus Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Network (CoVTEN) standard clinical assessment at cageside (Table S2) and anesthetic (Table S3) accesses. Additionally, vitals including rectal temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, and SpO2 were recorded in anesthetized animals. Following infection, untreated RMs experienced increases in rectal temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rates (Fig. S2a). IFNmod-treated RMs experienced higher SpO2 and heart rates than untreated RMs at 2dpi and 4dpi respectively. However, no differences in fold change (FC) of SpO2 or heart rate from pre-infection baseline (−7dpi) were observed between treatment groups (Fig. S2b). Neither treatment group experienced weight changes (Fig. S2c) and no differences were observed in cageside, anesthetic, and total clinical scores between untreated and IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. S2d). IFNmod was well tolerated without evidence of treatment induced clinical-pathology, nephrotoxicity, or hepatotoxicity when compared to untreated SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs.

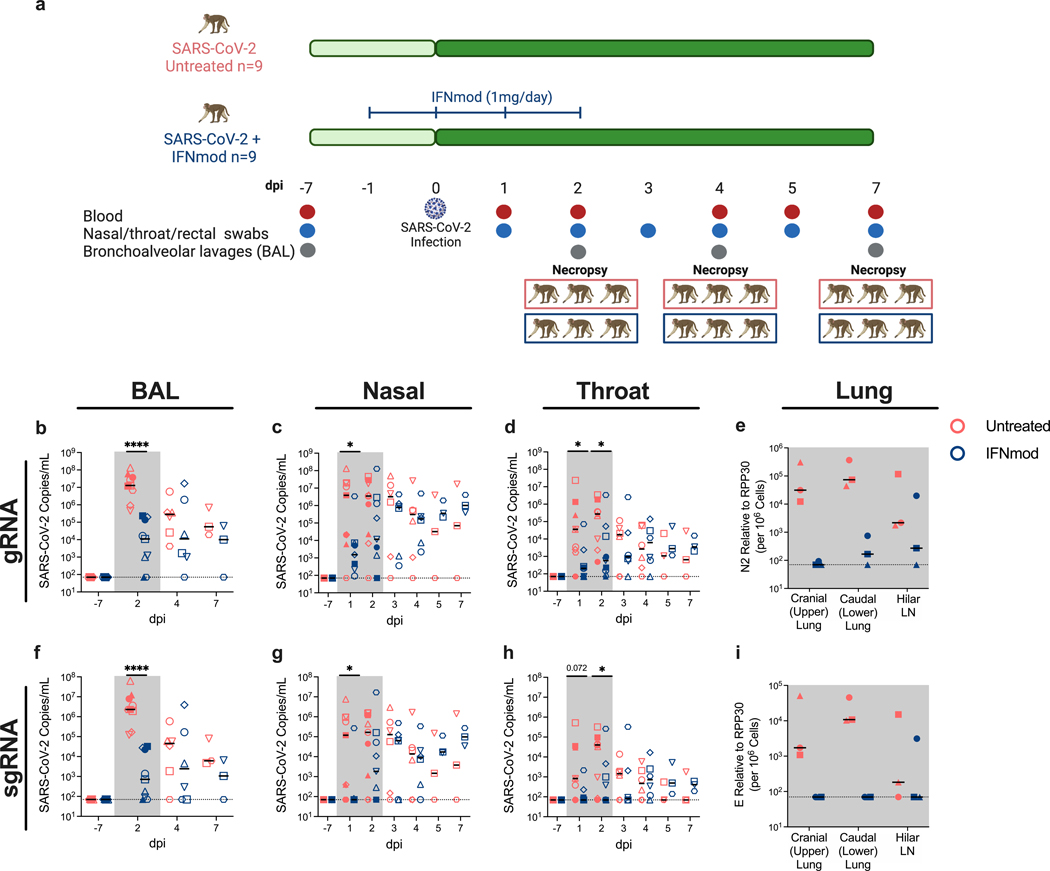

Fig. 3. IFNmod administration reduced viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs.

(a) Study Design; n=18 RMs (6–20 years old, mean = 10 years; 10 males and 8 females) were infected intranasally and intratracheally with SARS-CoV-2. 1 day prior to infection (−1 dpi), n=9 RMs started a 4-dose regimen of IFNmod (1mg/day) that continued up until 2 dpi while the other n=9 RMs remained untreated. RMs were sacrificed at 2 dpi (n=3 RMs per treatment arm), 4 dpi (n=3 RMs per treatment arm), or 7 dpi (n=3 RMs per treatment arm). Levels of SARS-CoV-2 (b-e) gRNA N and (f-i) sgRNA E in BAL, nasopharyngeal swabs, throat swabs, and cranial (upper) lung, caudal (lower) lung, and hilar lymph nodes (LNs) of RMs. For BAL viral loads, n=9 RMs per treatment arm for −7 and 2 dpi, n=6 RMs per treatment arm for 4 dpi, and n=3 RMs per treatment arm for 7 dpi. For nasopharyngeal and throat swab viral loads, n=9 RMs per treatment arm for −7, 1, and 2 dpi, n=6 RMs per treatment arm for 3 and 4 dpi, and n=3 RMs per treatment arm for 5 and 7 dpi. Lung and hilar LN viral loads are from RMs necropsied at 2 dpi (n=3 RMs per treatment arm). Untreated animals are depicted in red and IFNmod-treated animals are depicted in blue. Black lines in h-m represent median viral loads for each treatment group at each timepoint. Gray-shaded boxes indicate that timepoint occurred during IFNmod treatment. Statistical analyses were performed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney tests. * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value <0.0001.

Viral RNA levels were measured using genomic (gRNA) and sub-genomic (sgRNA) qRT-PCR as previously described (34, 43, 44). During the treatment phase of the study, up to 2 dpi, a drastic reduction in the levels of gRNA N (Fig. 3b-e) and particularly sgRNA E (Fig. 3f-i) was observed between untreated and IFNmod-treated RMs in the BAL (Fig. 3f), nasal swabs (Fig. 3g), and throat swabs (Fig. 3h) . Of note, this corresponds to IFNmod treatment resulting in a >3000-fold reduction in median sgRNA E in the BAL at 2 dpi (Fig. 3f). Additionally, in the nasal swabs at 1 dpi, there was a >1500-fold reduction in median sgRNA E copies in IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 3g). The sgRNA E levels detected at 1 and 2 dpi in the throat showed similar differences, 12-fold and 570-fold less median sgRNA E detected in IFNmod-treated RMs compared to untreated RMs at these respective timepoints (Fig. 3h). Once treatment was stopped, viral loads remained stable in the treated group up until 7 dpi, both for the genomic and the sub-genomic RNA. As consistently shown in previous studies (34–37), viral loads decreased in untreated, SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs shortly after the early peak, with swab and BAL viral loads no longer being statistically different between IFNmod-treated and untreated RMs starting from 4 dpi. BAL and nasal swab sgRNA E viral loads were reproduced by an independent laboratory (Fig. S3a) and further confirmed by sgRNA targeting the N gene (Fig. S3b).

To assess the impact of IFNmod on viral replication within lung tissue, sections of cranial (upper) and caudal (lower) lung lobes as well as hilar lymph nodes were collected from all animals at necropsy, with 3 RMs from each treatment group euthanized at 2, 4, and 7 dpi. Notably, IFNmod-treated RMs necropsied during the treatment phase at 2 dpi had lower viral gRNA (Fig. 3e) and sgRNA (Fig. 3i) levels in their upper and lower lungs as well as hilar LNs than untreated RMs. Although the small sample size at 2 dpi limited statistical power, this difference was substantial, with a 1500-fold and 500-fold reduction in mean gRNA and 250-fold and 300-fold reduction in mean sgRNA E observed in the upper and lower lung segments respectively of untreated vs. IFNmod-treated RMs. Additionally, when lung viral loads from all three necropsy timepoints were combined, gRNA N levels were found to be lower in the upper lungs of IFNmod treated RMs as compared to untreated RMs (Fig. S3c-d).

In summation, and consistent with the in vitro data in Calu-3 cells, in vivo treatment with IFNmod resulted in a highly reproducible (1–3 log10) decrease in viremia in the airways of SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs.

IFNmod treatment reduces lung pathology and soluble markers of inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs

Consistent with the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 gRNA and sgRNA in the BAL, cranial (upper) lungs, and caudal (lower) lungs of RMs treated with IFNmod at 2 dpi, we observed substantially lower expression of SARS-CoV-2 vRNA in the lungs of treated RMs as compared to untreated RMs at this timepoint by immunohistochemistry (Fig. S4a). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 vRNA staining was more diffuse in the untreated RMs, whereas IFNmod-treated RMs had small foci of infected cells. Mx1 was also found to be highly localized to regions of active infection in the lungs of untreated animals at 2 dpi; as expected under normal physiological conditions, Mx1 was more diffuse throughout the lung of IFNmod-treated RMs, regardless of the presence of virus (Fig. S4a).

Pathological analysis of the lungs was performed as previously described (34) by two pathologists, independently and blinded to the treatment arms using the following scoring criteria: type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, alveolar septal thickening, fibrosis, perivascular cuffing, and peribronchiolar hyperplasia. In both untreated and IFNmod-treated RMs necropsied at 2 dpi, no lung pathology was observed according to our scoring criteria. However, at 4 and 7 dpi, lung pathology was quantifiable, with untreated RMs having higher alveolar septal thickening and perivascular cuffing as compared to IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 4a, Fig. S4b). The total lung pathology score (considering severity and number of effected lobes) and average lung pathology score per lobe (measuring the average severity of abnormalities per lobe, independently of how many lobes had been affected) were lower in the IFNmod-treated group as compared to untreated RMs at 4 and 7 dpi (Fig. 4b-c, Fig. S4b).

Fig. 4. IFNmod administration resulted in lower levels of lung pathology and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs.

(a) Individual lung pathology scoring parameters, (b) total lung pathology scores, and (c) average lung pathology scores per lobe of RMs necropsied at 4 and 7 dpi (n=6 RMs per treatment arm). (d-k) Fold change of cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid relative to –7 dpi measured by mesoscale. One untreated animal was excluded from all mesoscale analysis due to abnormally high baseline levels. n=8 Untreated and 9 IFNmod for 2 dpi, n=5 Untreated and 6 IFNmod for 4 dpi, and n=2 Untreated and 3 IFNmod for 7 dpi. Untreated animals are depicted in red and IFNmod treated animals are depicted in blue. Black lines represent the median viral load, pathology score, or fold change in animals from each respective treatment group. Gray-shaded boxes indicate that timepoint occurred during IFNmod treatment. Statistical analyses were performed using two-sided non-parametric Mann-Whitney tests. * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value <0.0001.

A key feature of severe COVID-19 is the induction of multiple mediators of inflammation and chemotaxis of inflammatory cells to sites of infection (34). Accordingly, multiple chemokines and cytokines were shown to be highly upregulated in the BAL of untreated RMs at 2 dpi as measured by FC to baseline (−7 dpi); remarkably, at 2 dpi the same cytokines and chemokines remained stable at basal levels in IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 4d-k). More specifically, we observed differences in IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP4 and trending differences in TNFβ, IFNγ, and Eotaxin 3 between untreated and IFNmod-treated RMs.

Altogether, IFNmod treatment potently reduced immune mediated pathogenesis in the lung, as well as the levels of multiple cytokines and chemokines in BAL that orchestrate the recruitment of inflammatory cells to sites of infection.

IFNmod-treated RMs display decreased expansion of inflammatory monocytes and rapid downregulation of Siglec-1 expression

Several studies have reported an expansion of circulating inflammatory monocytes in blood of mild/moderate COVID-19 patients (45–47). High-dimensional flow cytometry was performed on whole blood and BAL of RMs pre- and post-infection to quantify the immunological effects of IFNmod on the frequencies of classical (CD14+CD16-), non-classical (CD14-CD16+), and inflammatory (CD14+CD16+) monocytes as previously described (34) (gating strategy depicted in Fig. S5a). Representative staining of monocyte subsets in untreated and IFNmod-treated animals at pre- and post-infection timepoints is shown in Fig. 5a. The frequency of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in blood increased from 11% to 31% of total monocytes from –7 dpi to 2 dpi in untreated RMs, but only from 14% to 18% in IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 5b-c). This difference between treatment groups was maintained at 4 dpi, where CD14+CD16+ monocytes accounted for 19% of total blood monocytes in untreated animals while only accounting for 10% of total blood monocytes in IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 5b-c). Therefore, treatment with IFNmod limited the expansion of inflammatory monocytes, thus reducing the potential for systemic and lower airway inflammation. Of note, at both 2 and 4 dpi, these differences were specific for blood, with no difference observed within the BAL.

Fig. 5. IFNmod-treated RMs had lower frequencies of CD14+CD16+ monocytes and expression of Siglec-1 compared to untreated RMs.

(a) Representative staining of classical (CD14+CD16-), non-classical (CD14-CD16+), and inflammatory (CD14+CD16+) monocytes in peripheral blood throughout the course of infection with frequency as a percentage of total monocytes. (b-c) Frequency as a percentage of total monocytes and fold change relative to pre-infection baseline (−7 dpi) of inflammatory (CD14+CD16+) monocytes in peripheral blood. (d) Representative staining and (e) frequency as a percentage of total monocytes of Siglec-1+ CD14+ monocytes in peripheral blood. (f) Frequency as a percentage of CD14+ monocytes that were Siglec-1+ in peripheral blood. (g) MFI of Siglec-1 on CD14+ monocytes in peripheral blood. Untreated animals are depicted in red and IFNmod treated animals are depicted in blue. In representative staining plots, frequencies of each quadrant are bolded. Black lines represent the median frequency or fold change in animals from each respective treatment group. Gray-shaded boxes indicate that timepoint occurred during IFNmod treatment. Statistical analyses were performed using two-sided non-parametric Mann-Whitney tests. * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value <0.0001.

Siglec-1, an interferon responsive transmembrane protein present on antigen presenting cells, has been shown to function as an attachment receptor for SARS-CoV-2 through enhancement of ACE2-mediated infection and induction of trans-infection (27, 48), and upregulation of Siglec-1 on circulating human monocytes has been identified as an early marker of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease severity (49). There was a strong and rapid upregulation of Siglec-1 on classical and inflammatory monocytes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in all untreated animals, with increases in the frequency of Siglec-1+CD14+ blood monocytes (as a percentage of total monocytes) from 0.4% to 70.6% (Fig. 5d-e), frequency of CD14+ blood monocytes expressing Siglec-1 from 0.5% to 91.7% between –7 dpi and 2 dpi (Fig. 5f), and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Siglec-1 on CD14+ blood monocytes from 1750 to 4050 (Fig. 5g). All 3 values remained elevated at 4 dpi as compared to −7 dpi. Expression of Siglec-1 was lower in the blood of IFNmod-treated RMs when compared to untreated RMs both at 2 and 4 dpi. The reduced expression of Siglec-1, a well-established downstream molecule of interferon signaling, on blood monocytes in treated RMs is consistent with the observation that IFNmod attenuated antiviral and pro-inflammatory ISGs. Of note, no differences were observed in the expression of Siglec-1 in the smaller myeloid population in the BAL (Fig. S5b-c).

To rule out the possibility that IFNmod treatment negatively impacted SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell and neutralizing antibody responses in SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs, we performed ex vivo stimulation of PBMCs with SARS-CoV-2 S peptide pools and NCAP followed by intracellular cytokine staining and serum SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays at 7 dpi. No differences were observed in SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell or neutralizing antibody responses between treatment groups. Additionally, in line with previous studies (34, 50), we found that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 and CD4 T cell responses were weak (Fig. S6a-e) and titers of neutralizing antibodies (Fig. S6f) were undetectable at 7 dpi.

IFNmod treatment attenuates inflammation and inflammasome activation in the lower airway following SARS-CoV-2 infection

To characterize the pathways that were impacted by IFNmod treatment in vivo, bulk RNA-Seq profiling of BAL, PBMCs, and whole blood was performed at multiple timepoints following SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infection induced a robust upregulation of ISG expression in the BAL of untreated animals at 2 dpi. Notably, the transcript levels of ISGs in BAL were substantially attenuated in RMs treated with IFNmod relative to the levels in untreated animals at both 2 and 4 dpi (Fig. 6a, Data File S1), with 15/16 ISGs being downregulated in IFNmod-treated RMs relative to untreated RMs at 2 dpi (Fig. 6b, Fig. S7a, Data File S1). By 7 dpi, ISG expression levels in the BAL of IFNmod-treated animals had returned to basal levels, whereas in untreated RMs, the ISGs in BAL remained elevated (Fig. 6a, Data File S1).

Fig. 6. IFNmod treatment suppresses gene expression of ISGs, inflammation, and neutrophil degranulation in the BAL of SARS-CoV-2 infected NHPs.

Bulk RNA-Seq profiles of BAL cell suspensions obtained at −7 dpi (n=9 per treatment arm), 2 dpi (n=9 per treatment arm), 4 dpi (n=6 per treatment arm), and 7 dpi (n=3 per treatment arm). (a) Heatmap of longitudinal gene expression in BAL prior to and following SARS-CoV-2 infection for the ISG gene panel. The color scale indicates log2 expression relative to the mean of all samples. Samples obtained while the animals were receiving IFNmod administration are depicted by a blue bar. (b) Distribution of log2 fold-changes of select ISGs relative to baseline. Filled dots represent the mean, and lighter dots are individual data points. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (padj < 0.05) of gene expression relative to baseline within treatment groups; black horizontal bars indicate BH corrected p-values of direct contrasts of the gene expression between groups at time-points (i.e. IFNmod vs Untreated) using the Wald test and the DESeq2 package. (c-e) GSEA enrichment plots depicting pairwise comparison of gene expression of 2 dpi samples vs −7 dpi samples within treatment groups. The untreated group is depicted by red symbols, and data for the IFNmod treated group is shown in blue. The top-scoring (i.e. leading edge) genes are indicated by solid dots. The hash plot under GSEA curves indicate individual genes and their rank in the dataset. Left-leaning curves (i.e. positive enrichment scores) indicate enrichment, or higher expression, of pathways at 2 dpi, right-leaning curves (negative enrichment scores) indicate higher expression at −7 dpi. Sigmoidal curves indicate a lack of enrichment, i.e. equivalent expression between the groups being compared. The normalized enrichment scores and nominal p-values testing the significance of each comparison are indicated. Gene sets were obtained from the MSIGDB (Hallmark and Canonical Pathways) database. (f-h) Heatmaps of longitudinal gene expression after SARS-CoV-2. Genes plotted are the top 10 genes in the leading edge of gene set enrichment analysis calculated in panels c-e for each pathway in the Untreated 2 dpi vs −7 dpi comparison. (i-l) Longitudinal gene expression for selected DEGs in immune signaling pathways. The expression scale is depicted in the top right of panel a and is applicable to panels a, f, g, h, i, j, k, and l.

To assess the impact of IFNmod treatment on inflammation in BAL, the post-infection enrichment of several gene sets in inflammatory pathways, previously associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, was examined at 2 dpi. There was a noticeable loss in enrichment in IL6 JAK/STAT (Fig. 6c) and TNF (Fig. 6d) pathways in IFNmod-treated RMs as compared to untreated RMs. This was even more pronounced for genes associated with neutrophil degranulation (Fig. 6e), where IFNmod-treated RMs had no enrichment between 2 dpi and baseline, but untreated RMs were enriched. Examination of the leading-edge genes in these pathways (Fig. 6f-h, Data File S1), and differentially expressed genes (DEGS) identified by DESeq2 analysis (Fig. 6i-l, Data File S1), displayed a stark divergence in the levels of several inflammatory mediators between the IFNmod and untreated groups. Notably, upregulation of IL6 (Fig. 6f), TNFA-inducing protein 6 (TNFAIP6), PTX3/TNFAIP5, TNF (Fig. 6g, i), IL10, IFNG, and IL7 (Fig. 6i) was evident in BAL samples in untreated animals but largely absent in IFNmod-treated animals (Fig. 6f-g, i). A similar pattern of expression was observed for genes encoding components of azurophilic granules (AZU1/azurocidin 1, RAB44) (Fig. 6h). In untreated animals, several chemokines involved in migration and recruitment of monocytes and macrophages (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4L1, CCL5, CCL7, CCL8, CCL22), neutrophils (CXCL3), and activated T cells (CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11) were elevated after infection; however, this expression was abrogated in the IFNmod-treated group (Fig.6j and S7b). In agreement with these observed effects on inflammatory mediators, we found that untreated RMs experienced a high induction of IRF1 in BAL at 2 dpi and 4 dpi compared to pre-infection baseline; however, there was no change in IRF1 following SARS-CoV-2-infection in the BAL of IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. S7b). Thus, in vivo treatment with IFNmod was found to not trigger IRF1 expression in uninfected RMs (Fig. 1f), and did not block IFR1 expression in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of note, while some of these differences in BAL gene expression of inflammatory mediators between treatment groups were maintained at 4 and/or 7 dpi, no differences were observed in protein levels of BAL inflammatory cytokines and chemokines measured via Mesoscale following the cessation of IFNmod treatment (Fig. 4d-k) This discrepancy between gene expression and protein levels of inflammatory mediators may result from post-transcriptional modification, a higher degree of sensitivity for the transcriptomic measurements as compared to the mesoscale, a higher consumption of those cytokines, thus masking their increase in BAL fluid while increasing the signaling, or a combination of these factors.

Consistent with reports by Laurent et al. of patients with mild COVID-19 (25), we observed an increase in the abundance of pDCs (defined by CLEC4A/BDCA2 expression) in the BAL of untreated RMs at 2 dpi relative to pre-infection baseline (−7 dpi) by bulk RNA-seq (Fig. S7c). Remarkably, IFNmod-treated RMs experienced a lower level of CLEC4C/BDCA2 and IFNαs in the BAL at 2 dpi as compared to untreated RMs, indicating that IFNmod reduced the recruitment of pDCs to the lower respiratory tract (Fig. S7d). Several genes regulating T cell activation and co-stimulation (CD38, CD69, CD274/PDL1, CD80, CD86, CD40) were upregulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection in untreated animals but minimally changed in IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 6k). Lastly, consistent with prior reports in human and mice (51–53), the expression of several S100 acute phase proteins (S100A8, S100A9, S100A12) were elevated in BAL samples from untreated animals but were absent in IFNmod-treated RMs. Collectively, these data demonstrate that IFNmod treatment induces a near complete loss of inflammatory activation and a reduction in pathways associated with recruitment and activation of myeloid cells, neutrophils, and pDCs in the lower airway.

Previously, the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway was shown to be the main driver of IFN-I induced pathology in SARS-CoV-2-infected hACE2 mice and inhibition of NLRP3 was observed to attenuate lung tissue pathology (23). To investigate if NLRP3 signaling was induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection in RMs, we characterized the enrichment of genes associated with the two phases of NLRP3 signaling: i) priming, in which cytokines and PRRs can upregulate inflammasome components such as NLPR3, CASP1, pro-IL1b and ii) activation, which consists of IL1β and IL18 release and pyroptosis (54). Canonical genes in the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway including IL1B, IL1RN/IL1RA, GSDMD, and NLRP3 were upregulated at 2 dpi in BAL samples from untreated animals (Fig. 6l). Additionally, AIM2 was observed to be upregulated in untreated RM BAL at 2 dpi, consistent with previous findings of AIM2 inflammasome activation in the monocytes of patients with COVID-19 (24). In IFNmod-treated RMs, however, there was no discernible upregulation from baseline of these inflammasome-associated factors (Fig. 6l).

Similar to what was described in BAL, IFNmod-treated animals experienced reduced expression of ISGs, inflammatory genes, and innate immune genes in PBMCs and whole blood relative to untreated animals following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. S8a-f). Thus, IFNmod treatment in RMs was not only able to potently attenuate inflammation and inflammasome activation in the lower airway, but also reduce inflammation systemically during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

IFNmod treatment inhibits the accumulation and activation of CD163+MRC1- inflammatory macrophages in the lower airway during SARS-CoV-2 infection

To survey the impact of IFNmod treatment on the landscape of immune cells in the lower airway, droplet-based sc-RNA-Seq was performed on cells obtained from BAL pre- and post- SARS-CoV-2 infection in both IFNmod and untreated animals. After quality filtering, 62,081 cells were clustered using Seurat, followed by more refined annotation with a curated set of marker genes (Fig. S9a-c). Consistent with prior studies (34, 55), most cells were of myeloid lineage (macrophages and monocytes), with a minority of several other immune phenotypes and epithelial cells observed (Fig. 7a, Fig. S9d). The expression of the 17 ISG panel utilized above was examined in these subtypes (except for neutrophils) and showed that ISGs peaked at 2 dpi in untreated animals in all subsets, including pDCs (Fig. S9e-g) which have previously been shown to possess a strong IFN-I signature in the BAL of mild COVID-19 patients (25). Remarkably, IFNmod treatment diminished expression of ISGs in all of the cell subsets identified in the BAL of SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs (Fig. S9e-g). Thus, IFNmod was shown to be highly effective at reducing the IFN-I response in all cells identified in the lower airway.

Fig. 7. Effect of IFNmod treatment on gene expression of BAL single-cells using 10X.

(n=6 Untreated, n=6 IFNmod except n=5 for Untreated −7dpi, IFNmod 4dpi, and IFNmod 7 dpi) (a) UMAP of BAL samples (62,081 cells) integrated using reciprocal PCA showing cell type annotations. UMAP split by treatment and time points are also shown. (b) Mapping of macrophage/monocyte cells in the BAL of SARS-CoV-2-infected untreated and IFNmod treated RMs to different lung macrophage/monocyte subsets from healthy rhesus macaque (84). (c) Percentage of different macrophage/monocyte subsets out of all the macrophage/monocytes in BAL at −7 dpi and 2 dpi from untreated and IFNmod treated RMs. The black bars represent the median. Statistical analyses between treatment groups were performed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney tests. * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value <0.0001. (d) Violin Plots showing the percentage of viral reads in each cell for total macrophages/monocytes and individual macrophages/monocytes subsets at 2 dpi determined using the PercentageFeatureSet in Seurat. (e-h) Dot Plots showing expression of selected (e) ISGs, (f) inflammatory genes, (g) chemokines, and (h) inflammasome genes. The size of the dot indicates the percentage of cells that express a given a gene and the color indicates the level of expression. The numbers of CD16+ monocytes were very low and have been thus omitted.

In recent work, we used sc-RNA-Seq to identify two myeloid population of the BAL of RMs, CD163+MRC1+TREM2+ and CD163+MRC1-, that infiltrated into the lower airway and produced inflammatory cytokines during acute SARS-CoV2 infection (56). We also showed that blocking the recruitment of these subsets with a JAK/STAT inhibitor abrogated inflammatory signaling (34, 56). Here, using a reference comprising of the macrophage/monocyte subsets from lungs of three healthy RMs as described previously (56, 57), we divided the clusters of Macrophage/Monocyte cells in the lower airways of RMs into four subsets: CD163+MRC1+, CD163+MRC1+TREM2+, CD163+MRC1-, and CD16+ monocytes (Fig. 7b, Fig. S10a-b). Of note, the CD16+ monocyte subset was omitted from further functional analyses due to its very low frequency. The percentage of CD163+MRC1+ macrophages in the BAL of untreated RMs decreased following SARS-CoV-2 infection due to the infiltration of CD163+MRC1- and CD163+MRC1+TREM2+ cells at 2 dpi (Fig. 7c, Fig. S10c). Conversely, the percentage of CD163+MRC1+ macrophages in the BAL of IFNmod-treated RMs remained relatively stable, with CD163+MRC1+ macrophages at 2 dpi being higher in IFNmod-treated vs. untreated RMs. Additionally, the CD163+MRC1- population in BAL was shown to have expanded from pre-infection baseline to 2 dpi in untreated animals as compared to IFNmod-treated animals (Fig. 7c, Fig. S10c). At 2 dpi, viral reads were detected (percentage of viral reads > 0) in macrophages/monocytes in the BAL of untreated RM at a rate of 9.8% (1030/9451 cells, median of individual animals 5.8%) (Fig. 7d, Fig. S10d) consistent with studies in human COVID-19 patients where an average of 7.8% of lung macrophages were reported to be SARS-CoV-2 positive (58). IFNmod decreased the frequency of macrophages/monocytes detected in the BAL of treated animals, with a rate of only 0.01% (1/7544) macrophages/monocytes having detectable viral reads (Fig. 7d, Fig. S10d). Among the macrophage subsets in the untreated group, the CD163+MRC1- subset was primarily associated with viral reads with a median of 11% of cells with detectable viral reads compared to 2.2% of CD163+MRC1+ and 2.4% of CD163+MRC1+TREM2+ (Fig. 7d, Fig. S10e). The number of cells with detectable viral reads gradually decreased at 4 dpi and was almost absent by 7 dpi (Fig. S10e).

Peak ISG levels in CD163+MRC1+, CD163+MRC1+TREM2+, and CD163+MRC1- macrophage subsets in BAL were observed at 2 dpi, with the highest and most sustained ISG expression occurring in the CD163+MRC1- population (Fig. 7e, Data File S3). In all three macrophage subsets in the BAL, IFNmod treatment effectively suppressed ISG expression (Fig. 7e). The CD163+MRC1- were the predominant subset producing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines at 2 dpi and other post-infection timepoints in both experimental groups, with IFNmod reducing the transcript levels of both (Fig. 7f-g, Data File S3).

Since a series of studies in humans and a humanized mouse model linked lower airway inflammation during SARS-CoV-2 infection to inflammasome activation specifically within infiltrating monocytes and resident macrophages (23, 24), we went on to characterize the expression of canonical inflammasome genes within each myeloid subset in the lower airway. We observed that the expression of AIM2, CASP1, GSDMD, IL1B, IL1RN and IL27 increased from −7 dpi to 2 dpi in the CD163+MRC1- subset and was maintained until 7 dpi (Fig. 7h, Data File S3). Several inflammasome-associated genes were also induced at 2 dpi in CD163+MRC1+ and CD163+MRC1+TREM2+ macrophages, albeit at lower cellular percentages overall compared to the CD163+MRC1- population (Fig. 7h). Across all three myeloid subsets, IFNmod consistently dampened the expression of inflammasome mediators, with the effect being most apparent at 2 dpi (Fig. 7h).

Collectively, these data indicate a profound effect of IFNmod treatment in inhibiting the accumulation of CD163+MRC1- macrophages, the most prevalent subset undergoing inflammasome activation and contributing to inflammation, in the lower airway during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

IFNmod treatment dampens inflammasome activation, bystander stress response, and cell death pathways in lung during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection

To further characterize the effect of IFNmod within the lower airway, sc-RNA-Seq was conducted on cell suspensions prepared from caudal (lower) lung lobe sections obtained at necropsy. Based on the expression of canonical markers, these cells were classified into four major groups – Epithelial, Lymphoid, Myeloid and “Other”- stromal and endothelial (Fig. 8a), which were then each clustered separately. The annotations were further fine-tuned based on the expression of marker genes (59) (Fig. S11a-d), yielding 42,699 cells with balanced representation of varying phenotypes across the lung (Fig. 8a and Fig. S11a-d). Interestingly, the Myeloid cluster in the lung contained an additional subset beyond the four phenotypes described in the BAL that was closely related to the CD163+MRC1+ cells and was defined by high expression of SIGLEC1 (Fig. 8a and Fig. S11c).

Fig. 8. Effect of IFNmod treatment on lung cells.

(a) UMAP based on reciprocal PCA of lung single cells collected at 2 dpi (n = 2 Untreated, 2 IFNmod) and 7 dpi (n = 1 Untreated, 1 IFNmod). The cells were classified into four broad categories – epithelial, lymphoid, myeloid and others (stromal and endothelial). The cells from each category were subset and clustered separately. UMAPs for each category with cell type annotations are also shown. (b) Selected gene sets that were found to be enriched (p-adjusted value < 0.05) in lung cells from untreated RMs at 2 dpi based on over-representation analysis using Hallmark, Reactome, KEGG, and BioCarta gene sets from msigdb. The size of the dots represents the number of genes that were enriched in the gene set and the color indicates the p-adjusted value. The gene set id in order are: M983, M15913, M27255, M27253, M5902, M5890, M5921, M27250, M41804, M5897, M5932, M27698, M27251, M29666, M27436, M27895, M27897, M1014. (c-f) Dot plots showing gene expression in lung cells present at higher frequencies from untreated and IFNmod treated macaques at 2 dpi (c) ISG, (d) genes related to inflammasome, (e) inflammation, and (f) programmed cell death. The size of the dot represents the percent of cells expressing a given gene and the color indicates the average expression.

Analyses at the pathway level at 2 dpi demonstrated a profound impact of IFNmod treatment in abrogating IFN-I signaling, as observed by an absence of enrichment of several IFN-related gene sets across all cell subsets in the lungs of IFNmod-treated RMs, despite being robustly overrepresented in untreated animals (Fig. 8b, Fig. S12a, Data FIle S4). At the gene level, analyses of individual cell subsets, including AT1 and AT2 cells (Epithelial cluster), CD163+MRC1- cells (Myeloid cluster), T cells, NK cells, and B cells (in the Lymphoid cluster) showed between 12 to 17 ISGs out of the panel of 17 ISGs being lower in IFNmod-treated RMs as compared to untreated RMs at 2 dpi (Fig. 8c, Fig. S12b, Data FIle S5).

At 7 dpi, five days after cessation of IFNmod treatment, expression of ISGs had largely normalized and was equivalent between the untreated and IFNmod groups (Fig. S12c, Data FIle S4). Taken together, these data demonstrate that IFNmod treatment was able to effectively suppress the IFN-I system across a broad distribution of pulmonary cellular subsets during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, including epithelium involved in gas exchange, immune cells in the interstitium, and cells in the lung vasculature.

Given the attenuated expression of genes related to inflammasome signaling in the BAL of IFNmod-treated RMs, we investigated if a similar dampening effect occurred in the lungs of treated animals. In untreated animals, we observed an enrichment of genes within the IL1 signaling cascade at 2 dpi relative to pre-infection baseline across several myeloid, lymphocyte, and endothelial subsets. Conversely, in IFNmod-treated RMs, there was no enrichment of the IL1 signaling cascade gene set at 2 dpi (Fig. 8b). Additionally, there was an enrichment of gene-sets representing necrotic cell-death pathways observed in untreated RMs, but not IFNmod-treated RMs (Fig. 8b). Since infection-induced pyroptosis is a process of inflammation-related necrosis that has been shown to largely occur within myeloid cells (60), we next delineated the contribution of individual subsets to the inflammatory state in the lower airway by visualizing DEGs across subsets (Fig. 8d-f, Fig. S12d-h, Data FIle S5). Notably, expression of components of the inflammasome (Fig. 8d and Fig. S12e) and classical inflammatory mediators (Fig. 8e and Fig. S12f) were restricted to the myeloid subsets, suggesting that inflammasome priming and activation in the lung during SARS-CoV-2 infection is largely constrained to monocyte/macrophage populations. Consistent with this model, expression of GSDMD, a central regulator of NLRP3-regulated pyroptosis, was highest in monocyte/macrophage populations (Fig. 8d). Importantly, levels of these inflammasome components were all potently reduced by IFNmod treatment (Fig. 8d).

In untreated RMs, widespread induction of genes from the programmed cell death (Fig. 8f and Fig. S12g) and response to heat stress (Fig. S12d, h) pathways were observed across the landscape of lung cellular subsets, particularly in the Myeloid and Lymphoid classes of phenotypes. In contrast, within the IFNmod-treated group, expression of genes related to programmed cell death and response to heat stress was strikingly attenuated; this effect was particularly apparent in capillary and capillary aerocytes (Fig. 8f, Fig. S12d, g-h).

These data are consistent with a model in which, during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, activated monocytes and macrophages cells undergo inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis, which provides secondary stress signals to the non-immune cell classes of the lung. Importantly, IFNmod treatment was also able to abolish induction of these stress and cell death related pathways in these pulmonary subsets.

DISCUSSION

The ways in which IFN-I regulates SARS-CoV-2 replication and disease progression are incompletely understood. Here, we employed an integrated systems approach in a nonhuman primate model of mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection to dissect the roles of antiviral and pro-inflammatory IFN-I responses in early SARS-CoV-2 infection using a mutated IFNα2 (IFN-I modulator; IFNmod). Notably, this protein was previously demonstrated to have a high affinity to IFNAR2 and markedly lower affinity to IFNAR1, resulting in receptor occupancy, and blocking binding and signaling of all forms of endogenous IFN-I produced in response to viral infection (38–40). While SARS-CoV-2-infection in untreated RMs was shown to induce a strong IFN-I response with concomitant inflammation and lung damage, IFNmod remarkably and potently reduced viral loads in the upper and lower airways, inflammation, and lung pathology. Therefore, using an in vivo intervention targeting IFN-I to understand its role in SARS-CoV-2 infection, our study shows that early IFN-I restrains SARS-CoV-2 replication and an aberrant IFN-I response contributes to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Furthermore, it also demonstrates a beneficial role of IFNmod in limiting both viral replication and SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammation in NHP when initiated prior to infection.

Initially, we evaluated the effects of administering IFNmod in uninfected RMs and found that IFNmod resulted in a modest and transient stimulation of antiviral ISGs, while genes associated with systemic inflammation remained unchanged. This is consistent with previous in vitro work on cancer cell lines in which low amounts of IFN-I induced the transcription of robust antiviral genes, without the activation of tunable inflammatory genes which often require high concentrations and high affinity IFN-I (35). Next, we showed that IFNmod was capable of substantially reducing SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in vitro in Calu-3 cells to levels equivalent to the antiviral Nirmatrelvir (packaged with ritonavir and sold as Paxlovid), particularly when administered pre-infection. These results raised the intriguing hypothesis that regulating IFN-I signaling using IFNmod in the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection could balance low levels of antiviral genes while blocking the expression of pro-inflammatory genes. Remarkably, the administration of IFNmod prior to and during the first two days of SARS-CoV-2 infection in RMs was found to result in a reduction in viral loads in the BAL (>3 log reduction), nasal, and throat swabs. Additionally, IFNmod reduced viral loads in the upper and lower lungs as well as hilar LNs of RMs during the treatment period and limited lung pathology as well as the production of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines within the lower airways.

We show that IFNmod administration prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection in RMs results in an upregulation of antiviral ISGs, while potently dampening endogenous IFN-I signaling and limiting the immunopathology that has been linked to IFN-I following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although it is likely that the reduction in inflammatory responses that we observed in IFNmod-treated RMs may be partially attributed to lower viral loads in these animals, our data support a direct action of IFNmod in targeting inflammation independent of reducing viral load. This is evidenced by IFNmod treatment in the presence of IFNα (and absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection) potently inhibiting pro-inflammatory CXCL10 in Calu-3 human lung cancer cells and IFNmod-treated RMs still experiencing lower levels of inflammation at 4 and 7 dpi despite viral loads no longer being different between treatment groups. Consistent with the observation that IFNmod achieved a “goldilocks” effect of upregulating antiviral ISGs while reducing expression of inflammatory mediators, we observed that IFNmod blocked the expression of the transcription factor IFR1, which has previously been shown to be a key regulator of proinflammatory gene expression triggered by Type I IFNs, during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Altogether, these data support a working model in which early antiviral IFN-I responses restrain SARS-CoV-2 replication, whereas a sustained and systemic IFN-I response, particularly when extended to pro-inflammatory genes, exacerbate SARS-CoV-2 pathology.

Notably, SARS-CoV-2 infection in RMs represents a mild/moderate model of COVID-19; thus, one limitation of our study is that does not address the impact of IFNmod in severe COVID-19. Additionally, while we observed reductions in SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and inflammatory gene expression in Calu-3 cells when IFNmod was administered post-infection, it is also important to note that we initiated IFNmod treatment in RMs prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2 and that changing the timing of administration could also lead to different results in vivo.

IFNmod administration in SIV-infected RMs during the first 4 weeks of infection was previously shown to result in higher plasma viral loads, increased CD4+ T cell depletion, and a more rapid progression to AIDS. These results highlight that modulating IFN-I during infection with inherently different viruses (SARS-CoV-2, which establishes an acute infection that is naturally controlled in a few weeks in RMs and SIV, which establishes a persistent, chronic infection) can have vastly different effects on pathogenesis.

Our data also show a central role of IFN-I in regulating the axis of infiltrating monocytes and subsequent inflammation within the airway and lung interstitium during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Numerous studies have observed hyperactivation of monocytes and macrophages in COVID-19 (reviewed in (61)). Within the lower airway, an early study identified elevated expression of IL1B, IL6, and TNF within alveolar macrophages in patients with severe COVID-19 (55). Subsequent work has progressed to dissect the precise phenotypes contributing to SARS-CoV-2 driven inflammation within the monocyte/macrophage axis in mice (62), NHPs (36, 56), and more recently, in humans (63). In these studies, a consistent model has emerged in which resident tissue alveolar macrophages are displaced by inflammatory, infiltrating monocytes and interstitial macrophages. Notably, we observed IFNmod treatment to profoundly impact monocyte/macrophage populations in vivo, decreasing the activation state of the CD163+MRC1- population and its recruitment to the BAL as well as reducing the expansion of CD14+CD16+ pro-inflammatory monocytes in the periphery relative to untreated RMs. We also identified the CD163+MRC1- interstitial macrophage-like subset as the predominant population expressing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and exhibiting inflammasome activation within the alveolar space during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, and supporting recent studies in humanized mice (23), our work demonstrates that targeted modulation of the IFN-I system during early SARS-CoV-2 can effectively eliminate the level of cell-associated virus on macrophages and broadly dampen induction of the inflammasome.

Autopsies of patients succumbing to severe COVID-19 have linked disease pathology to the accumulation of aberrantly activated macrophages in lungs (64) and hyperactivated Siglec1+ macrophages co-localizing with SARS-CoV-2 in the hilar LNs of autopsy samples (65). Grant et al proposed a model in which alveolar macrophages act as “Trojan horses” that traffic to adjacent lung regions, ferrying cell-associated virus and propagating inflammation (66). In this context, the observation that IFNmod was able to potently reduce the expression of the viral attachment receptor Siglec-1 on CD14+ blood monocytes and BAL macrophages, with concomitantly lowered ISG expression and inflammasome activation, provides a possible mechanism by which the IFN system may enhance trans-infection and enable propagation and dissemination of inflamed macrophages in the airspace. Our scRNA-Seq data are consistent with the “Trojan horse” hypothesis and extend it by identifying that the CD163+MRC1- and CD163+TREM2+ populations are the predominant populations in the lung in which the inflammasome is induced.

This study, using an intervention targeting both IFN-α and IFN-β pathways, demonstrates the central role of IFN-I in regulating the early events of SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis in RMs, making a strong case that, while rapid and transient stimulation of antiviral ISGs helps restrain SARS-CoV-2 replication, IFN-I driven excessive inflammation has deleterious consequences if left unchecked.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The main objective of our study was to determine how downregulating early IFN-I pathways affects SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenesis. We utilized IFN modulator (IFNmod), a mutated IFNα2 with high affinity to IFNAR2, but markedly lower affinity to IFNAR1 that was previously demonstrated to block binding of endogenous IFN-I. We first assessed the impact of IFNmod on interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) in uninfected rhesus macaques (RMs) and uninfected Calu-3 cells. Additionally, we also evaluated the ability of IFNmod to reduce SARS-CoV-2 replication in infected Calu-3 cells. Next, we used the RM model of SARS-CoV-2 to examine the effect of IFNmod on SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenesis in vivo. 18 RMs (9 untreated and 9 IFNmod-treated from −1 to 2 days post infection (dpi)) were inoculated with WA1/2020 SARS-CoV-2 and necropsied at days 2, 4, and 7dpi. We compared longitudinal BAL, nasopharyngeal swab, and throat swab viral loads as well as lung and hilar LN tissue viral loads at necropsy between untreated and IFNmod-treated animals. Additionally, to evaluate the impact of IFNmod on SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis, we also performed mesoscale immunoassay, flow cytometry, and bulk RNAseq as well as scRNAseq analysis.

Study Approval

EPC’s animal care facilities are accredited by both the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All animal procedures were performed in line with institutional regulations and guidelines set forth by the NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition, and were conducted under anesthesia with appropriate follow-up pain management to minimize animal suffering. All animal experimentation was reviewed and approved by Emory University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under permit PROTO202100003.

Animal models

In the uninfected animal study, 4 (2 females and 2 males; average age of 9 years and 2 months) specific-pathogen free (SPF) Indian-origin rhesus macaques (RM; Macaca mulatta; Table S1) were housed at Emory National Primate Research Center (ENPRC) in the BSL-2 facility. All four uninfected RMs were administered 1 mg/day of IFN-I modulator (IFNmod) for four consecutive days. IFNmod was supplied in solution and diluted with PBS and administered intramuscularly in the thigh. Peripheral blood (PB) and BAL collections were performed at pre- and post-administration timepoints as annotated (Fig. 1a).

In the SARS-CoV-2-infected animal study, 20 (8 females and 12 males; average age of 11 years and 8 months) SPF Indian-origin rhesus macaques (Table S1) were housed at the ENPRC as previously described (67) in the ABSL3 facility. The number of animals was chosen based on (1) viral loads, (2) monocytes inflammation, and (3) RNA transcriptomic data previously published by our group (34) in SARS-CoV-2 infected RMs treated with a JAK1/2 inhibitor. RMs were infected with 1.1×106 plaque forming units (PFU) SARS-CoV-2 via both the intranasal (1 mL) and intratracheal (1 mL) routes concurrently. Two SARS-CoV-2-infected animals were excluded due to error in specimen processing, resulting in missing time points. Nine RMs were administered 1 mg/day of IFN-I modulator (IFNmod) starting one day prior to infection (−1 dpi) until 2 dpi. IFNmod was supplied in solution and diluted with PBS and administered intramuscularly in the thigh. The other 9 animals served as untreated, SARS-CoV-2 infected group. At each cage-side access, RMs were clinically scored for responsiveness, discharges, respiratory rate, respiratory effort, cough, and fecal consistency (Table S2). Additionally, at each anesthetic access, body weight, body condition score, respiratory rate, pulse oximetry, and rectal temperature was recorded and RMs were clinically scored for discharges, respiratory character, and hydration (Table S3). Longitudinal tissue collections of peripheral blood (PB); bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL); and nasal, and pharyngeal mucosal swabs in addition to thoracic X-rays (ventrodorsal and right lateral views) were performed immediately following IFNmod administration as annotated (Fig. 3a). In addition to the tissues listed above, at necropsy the following tissues were processed for mononuclear cells: hilar LN, caudal (lower) lung, cranial (upper) lung, and spleen. Additional necropsy tissues harvested for histology included nasopharynx.

IFNmod production

IFNmod (also named IFN-1ant) was produced as described in the Supplementary Materials.

ISGs induction in IFNmod-treated Calu-3 cells

Human epithelial lung adenocarcinoma cells (Calu-3 cells) were acquired through and authenticated by ATCC (HTB-55). Specifications of authentication are available from the manufacturer. qRT-PCR was performed on uninfected Calu-3 cells treated with various concentrations of IFNmod with or without IFNα to assess induction of antiviral ISGs Mx1 and OAS1 and inflammatory gene CXCL10 as described in the Supplementary Materials.

Impact of IFNmod on SARS-CoV-2 replication in Calu-3 cells

The ability of IFNmod treatment to reduce SARS-CoV-2 replication when initiated pre- and post-infection respectively was assessed in Calu-3 cells as described in the Supplementary Materials.

Viral Stocks

The SARS-CoV-2 NL-02–2020 (BetaCoV/Netherlands/01/NL/2020) viral stock used in Calu-3 cell experiments was obtained from the European Virus Archive. The SARS-CoV-2 viral stock used in RM experiments (USA-WA/2020 strain) was obtained from BEI Resources (Cat no. NR-53899, Lot: 70040383). Prior to infection, stocks were titered on Vero E6 cells by plaque assay (ATCC, CRL-1586) and sequenced to verify the stock’s genomic integrity.

Determination of viral load RNA

SARS-CoV-2 gRNA N and sgRNA E were quantified in nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs, throat swabs, and bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) as described in the Supplementary Materials. Using remaining viral RNA extracted from NP swabs and BAL, sgRNA E mRNA viral loads were repeated by the NIAD Vaccine Research Center (VRC) as described previously (70, 71) and sgRNA N mRNA was also quantified as detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

SARS-CoV-2 quantification from necropsy samples

Upper cranial lung, lower caudal lung, and hilar LN were collected at necropsy, homogenized, and tissue viral RNA was extracted and quantified as detailed in the Supplementary Materials. Additionally, RNAscope in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (72, 73) to characterize the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 vRNA within lung tissue.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Due to study end point, the animals were euthanized, and a complete necropsy was performed. Various tissue samples including lung, nasal turbinates, trachea, and brain were collected for histopathology which was performed as detailed in the Supplementary Materials. Additionally, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of Mx1 on sections of lung was performed as previously described (35, 72, 73).

Tissue Processing

Peripheral blood (PB), nasopharyngeal swabs, throat swabs, and BAL were collected longitudinally. At necropsy, lower (caudal) lung, upper (cranial) lung, and hilar LNs were also collected. Detailed methods pertaining to the collection and processing of these tissues are included in the Supplementary Materials.

Bulk and single-cell RNA-Seq Library and sequencing from NHP BALs

Single cell suspensions from BAL were prepared in a BSL3 as described above for flow cytometry and libraries for bulk and sc-RNA-Seq were prepared as described previously (34, 56). For sc-RNA-Seq, 10,000 cells each from two individual animals containing bar-code hashes were pooled and a total of approximately 20,000 cells were loaded onto the 10X Genomics Chromium Controller. For BAL samples, 10,000 cells from two individual animals containing barcode hashes were pooled except for two samples. Additional sequencing details can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Bulk RNA-Seq analysis

Reads were aligned using STAR v2.7.3. (74). The STAR index was built by combining genome sequences for Macaca mulatta (Mmul10 Ensembl release 100), SARS-CoV2 (strain MT246667.1 - NCBI). Transcript abundance and differential expression testing were performed using htseq-count (75) and DESeq2 (76) as described previously (56). A detailed listing of methods for expression and pathway analyses is described in the Supplementary Materials.

Bulk RNA-Seq Whole blood analysis

Bulk RNA-Seq sample preparation and bioinformatic analyses of whole blood samples were performed independently of BAL or PBMC samples and are described in detail in the Supplementary Materials.

Single-cell RNA-Seq Bioinformatic Analysis

The cellranger v6.1.0 (10X Genomics) pipeline was used for processing the 10X sequencing data and the downstream analysis was performed using the Seurat v4.0.4 (77) R package as described previously (56). A composite reference comprising of Mmul10 from Ensembl release 100 and SARS-CoV2 (strain MT246667.1 - NCBI) was used for alignment of sequencing with cellranger. The percentage of SARS-CoV2 reads was determined using the PercentageFeatureSet for SARS-CoV2 genes. For BAL samples, a total of 62,081 cells across all animals passed QC and were used for analyses. For lung samples, a total of 42,699 cells passed upstream QC and were used for analysis. A detailed breakdown of the number of cells per sample/animals is recorded in Data File S2. Detailed methodology for the sc-RNA-Seq bioinformatics are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Immunophenotyping

23-parameter flow cytometric analysis was performed on whole blood, fresh PBMCs, and mononuclear cells (106 cells) derived from LN biopsies, BAL, and lung as detailed in the Supplementary Materials using anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which we (67, 78–80) and others, including databases maintained by the NHP Reagent Resource (MassBiologics), have shown as being cross-reactive in RMs.

T cell stimulation and intracellular cytokine staining assays

The assay was performed as described before (50, 81). Briefly, ~2 × 106 PBMCs from n=3 animals at days −7pi and 7pi were cultured in 200-μl final volume in 5-ml polypropylene tubes (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) in the presence of anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) and anti-CD49d (1 μg/ml) (BD Biosciences) and the following conditions: (i) negative control with dimethyl sulfoxide only, (ii) whole spike (S) peptide pool 1 (n = 253 peptides, 15-mers with 10-residue overlap) (Weiskopf and Sette labs, LJI, La Jolla, CA) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, (iii) N peptide pool, and (iv) phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin. Brefeldin A was added to all tubes at 10 μg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and cells were cultured for 6 hours and transferred to 4°C before staining for flow cytometry as described in the Supplementary Materials.

SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Neutralization Assays

SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus neutralization assay was based on protocol in Crawford et al 2020 (82) and conducted with minor changes to how it was previously reported in Voigt et al 2022 (83). The revised protocol is detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

Mesoscale

Plasma was collected from EDTA blood following centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes. BALF supernatant was obtained from BAL that was filtered through a 70μm cell strainer and spun down at 1800rpm for 5 minutes. Both plasma and BALF were frozen at −80C and later thawed immediately prior to use.

Cytokines were measured using Mesoscale Discovery. Pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were measured as part of V-Plex (#K15058D-1). INF alpha was measured with a U plex (K156VHK-1 Mesoscale Discovery, Rockville, Maryland). Levels for each cytokine/chemokine were determined in double and following the instructions of the kits. The plates were read on a MESO Quick plex 500 SQ120 machine.

Quantities were determined using the discovery Work bench software for PC (version 4.0).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed two-sided with p-values ≤0.05 deemed significant. Ranges of significance were graphically annotated as follows: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001. Analyses for Figs. 1g, 2b-c, 2e-h, 3b-I, 4a-k, 5b-c, 5e-g, S1b-d, S2a-b, S3a-d, S4b, S5b-c, and S6b-f were performed with Prism version 8 (GraphPad) while analyses for Figs. 7c, S9d and S10c were performed with R version 4.0.3 (using function wilcox.test with the parameters paired and correct set to FALSE). The Wald test (DESeq2 package) was used to calculate the BH corrected p-values for Figs. 6b and S7.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. IFNmod treatment initiated post-SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to reduction in viral RNA loads and inflammatory gene expression.

Fig. S2. Administration of IFNmod was safe and well-tolerated in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs.

Fig. S3. IFNmod reduced nasopharyngeal, BAL, and lung viral loads in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs.

Fig. S4. Mx1 is more highly localized to viral foci in untreated SARS-CoV-2-infected RMs and IFNmod treatment decreases lung pathology.

Fig. S5. Flow gating strategy and expression of Siglec1+ in BAL.

Fig. S6. IFNmod treatment does not impact SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell or neutralizing antibody responses.

Fig. S7. Gene expression in BAL in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2 after treatment with IFNmod.

Fig. S8. Gene expression in PBMCs and whole blood in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2 after treatment with IFNmod.

Fig. S9. Expression of marker genes in BAL single-cells.

Fig. S10. Effect of IFNmod treatment on different BAL cell types.

Fig. S11. Cell annotation of lung samples.

Fig. S12. Effect of IFNmod treatment on gene expression of lung cells.

Table S1. Uninfected and SARS-CoV-2-infected macaque characteristics.

Table S2. Coronavirus Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Network (CoVTEN) standard clinical assessment for cage-side scores, related to Fig. S3b.

Table S3. Coronavirus Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Network (CoVTEN) standard clinical assessment for anesthetized scores, related to Fig. S3b.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to dedicate this manuscript to Dr. Timothy N. Hoang, whose commitment to this project and to scientific discovery were crucial in propelling this study forward. Dr. Hoang will be remembered for his intelligence, drive, and love for science and all of the lives that he touched during his short but impactful career. We thank the Emory National Primate Research Center (EPC) Division of Animal Resources, especially Joyce Cohen, Sherrie M. Jean, and Rachelle L. Stammen in Veterinary Medicine and Stephanie Ehnert, Stacey Weissman, Denise Bonenberger, John M. Wambua, and Racquel Sampson-Harley in Research Resources for providing support in animal care. We would also like to thank Sanjeev Gumber in the EPC Division of Pathology, Kalpana Patel in the EPC Safety Office, Shelly Wang in the Emory CFAR Core, Krista Krish in the EPC Virology Core, Nichole Arnett in the EPC Clinical Pathology Lab, and Elizabeth Beagle, Hadj Aoued, Tristan Horton, David Cowan, Sydney Hamilton, and Thomas Hodder in the Emory NPRC Genomics Core. Additionally, we would like to thank Erin Haupt and the Immunologic Core, Department of Immunology, TNPRC for help with MSD analysis, Elise Smith and Jean Chang in the Gale Lab at WaNPRC for blood RNA-Seq library preparation services, Samuel Beaver for pseudovirus neutralization assays services, and Jana-Romana Fischer and Kerstin Regensburger at Ulm University Medical Center for excellent technical assistance.

Funding:

This work was funded by P510D011132–60S4: COVTEN/ACTIV; the Emory MP3 Grant; Fast Grants #2144, and the Pitts Foundation (all to MPa). Support for this work was also provided by award NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) P51OD11132 to EPC, P30 AI050409 to the Emory Center for AIDS Research Systems Immunology Core (to RPJ), 1RO1 HL140223 (to RDL), P51 OD011092 (to JDE) and P51 OD010425 (WaNPRC; to MGal, LSW, JT-G). FK and KMJS were supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG; CRC 1279 and SP1600/4–1) and the German Federal Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF; Restrict SARS-CoV-2 and IMMUNOMOD). MH is part of the International Graduate School of Molecular Medicine, Ulm. Next generation sequencing services and 10X Genomics captures were performed in the Emory NPRC Genomics Core, which is supported in part by NIH P51OD011132. Sequencing data was acquired on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 funded by NIH S10OD026799 to SEB. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nor does it imply endorsement of organizations or commercial products.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.