Abstract

Lymph nodes (LNs) are sites of active human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) replication and disease at both early and late stages of infection. Consequently, variant viruses that replicate efficiently and subsequently cause immune dysfunction may be harbored in this tissue. To determine whether LN-associated SIVs have an increased capacity to replicate and induce cytopathology, a molecular clone of SIV was isolated directly from DNA extracted from unpassaged LN tissue of a pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina) infected with SIVMne. The animal had declining CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts at the time of the LN biopsy. In human CD4+ T-cell lines, the LN-derived virus, SIVMne027, replicated with relatively slow kinetics and was minimally cytopathic and non-syncytium inducing compared to other SIVMne clones. However, in phytohemagglutinin-stimulated pig-tailed macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), SIVMne027 replicated efficiently and was highly cytopathic for the CD4+ T-cell population. Interestingly, unlike other SIVMne clones, SIVMne027 also replicated to a high level in nonstimulated macaque PBMCs. High-level replication depended on the presence of both the T-cell and monocyte/macrophage populations and could be enhanced by interleukin-2 (IL-2). Finally, the primary determinant governing the ability of SIVMne027 to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs mapped to gag-pol-vif. Together, these data demonstrate that LNs may harbor non-syncytium-inducing, cytopathic viruses that replicate efficiently and are highly responsive to the effects of cytokines such as IL-2.

In both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)- and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected individuals, high viral load and generalized immune activation herald CD4+ T-cell decline and progression to AIDS (22, 36, 42, 49, 54). This correlation most likely reflects the fact that these lentiviruses require cellular activation signals to productively infect CD4+ T lymphocytes (7, 46, 57, 64). It also raises the possibility that chronic immune stimulation plays a central role in HIV and SIV pathogenesis. Support for this hypothesis comes from studies of HIV-1 that have demonstrated transient increases in plasma viremia and proviral burden in infected individuals immunized against hepatitis B or tetanus toxoid, or having an intercurrent secondary infection (11, 13, 55), and from recent studies showing that continuous rounds of virus infection and replication drive rapid CD4+ T-cell turnover (28, 62). On the other hand, the persistent replication of HIV and SIV that occurs throughout the course of infection could be the primary driving force underlying the maintenance of a chronic immune activation state (22). In fact, a unique strain of SIVsmm, SIVPBj14, causes massive T-cell activation both in vivo and in vitro, demonstrating that a lentivirus is capable of inducing an immune activation state (52). Together, these data not only demonstrate the importance of virus-host interactions in the regulation of HIV and SIV replication but also suggest that a determinant of virulence may be defined by a virus’s ability to induce and utilize immune activation signals for efficient replication.

The requirement for cellular activation signals in the initiation and maintenance of HIV-1 and SIV replication is well established in vitro (7, 45, 46, 57, 64), but the mechanism by which the virus interacts with cellular signalling pathways to enhance viral replication remains poorly understood. In infected T cells, activation signals (e.g., via T-cell receptor/CD3 and CD28 and cytokine receptors) release the arrest in viral replication that occurs at postentry steps prior to integration of the provirus, including reverse transcription and nuclear translocation of the viral preintegration complex (7, 45, 46, 57, 64). Furthermore, in productively infected cells, cellular activation is important for upregulating viral transcription from the long terminal repeat (LTR) (2, 27, 29). Additionally, there is evidence that HIV and SIV proteins such as envelope (Env) gp120 and Nef can promote or suppress viral replication through the induction of cytokines or modulation of T-cell activation, respectively (6, 20, 26, 37). In the context of these data, virulence may potentially be influenced by genetic variation in viral determinants that affect infectivity, postentry steps in the virus life cycle, and transcription.

Genetic variation has been shown to influence the phenotype of HIV-1 (34). Indeed cytopathic variants of HIV-1 that emerge in the peripheral blood (PB) during the course of infection may play an active role in determining the rate of disease progression. These viruses are associated with an increase in viral load, accelerated CD4+ T-cell decline, and onset of AIDS; they are frequently able to infect T-cell lines, and they may be rapidly replicating, highly cytopathic, and syncytium inducing (T-tropic, rapid-high/SI) in tissue culture (1, 12, 14, 15, 23, 59, 60). By contrast, viruses isolated early after infection, when CD4+ T-cell counts are stable or slowly declining, are commonly macrophage-tropic, slowly replicating, minimally cytopathic, and non-syncytium inducing (M-tropic, slow-low/NSI) (1, 12, 14, 15, 23, 59, 60). We have observed a similar shift in the phenotype of viruses isolated from the PB of SIVMne-infected macaques at early and late stages of infection (50). Together, these data have led to the hypothesis that T-tropic, rapid-high/SI viruses are more pathogenic than M-tropic, slow-low/NSI viruses. However, immune dysfunction is evident early in infection (53), when the virus population tends to be M-tropic, slow-low/NSI, suggesting that these viruses may also have an impact on disease progression.

Immune activation in HIV-1- and SIV-infected individuals is prominent in secondary lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes (LNs), which serve as major reservoirs for the viruses (10, 21, 22, 44). In LNs, manifestations of disease are evident at early and late stages of infection (10, 22, 44), perhaps due to viral replication associated with chronic immune stimulation within this tissue. Moreover, it has been shown, at least for SIV, that the predominant variants harbored in lymphoid tissue are genetically distinguishable from those found in PB (8). While there is a high level of viral replication and evidence for disease in LNs of HIV-1- or SIV-infected individuals, primary full-length LN-derived molecular variants of HIV-1 or SIV have not been directly cloned (i.e., without prior selection in culture) and characterized. Thus, in this study we describe the direct cloning and in vitro characterization of a LN-derived molecular clone of SIVMne.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of a SIVMne molecular clone from LN tissue.

DNA was extracted from mesenteric LN tissue of a pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina, animal T78027) infected with an uncloned isolate of SIVMne (5). This isolate reproducibly causes an AIDS-like syndrome in pig-tailed and rhesus (M. mulatta) macaques in 1 to 3 years (5). The mesenteric LN tissue was biopsied at 16 months postinfection when the animal had declining CD4+ T-cell counts and early signs of AIDS. The DNA was digested with EcoRI, layered onto a 10 to 40% continuous sucrose gradient in STE buffer (1 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 8], 5 mM EDTA [pH 8]), and fractionated by centrifugation at 26,000 rpm for 20 h at 15°C in a Beckman (Fullerton, Calif.) SW41.1 rotor. Fractions containing DNA fragments 10 to 20 kb in size were concentrated by ethanol precipitation, ligated into the EcoRI sites of the λ Dash II arms, and packaged by using the Gigapack II XL system as specified by the manufacturer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Approximately 107 plaques were screened for SIV, using 32P-labeled gag and env DNA probes derived from a pathogenic clone of SIVMne (SIVMneCl8 [4, 38, 43]). Plaques that scored positive for both probes were isolated and purified. One phage clone encoded a full-length provirus which we designated SIVMne027. The provirus was excised from the λ Dash II vector with EcoRI and ligated into the EcoRI site of pUC18. The full DNA sequence of SIVMne027 was determined by manual sequencing using Sequenase version 2.0 (United States Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio) as well as an ABI automated sequencer.

Construction of recombinant viruses.

To construct a chimeric virus containing the 5′ half of SIVMne027 (R-U5-gag-pol-5′vif) and 3′ half of SIVMneCl8 (3′vif-vpx-vpr-rev-tat-env-nef-U3-R) or the reciprocal recombinant virus, BstBI-SalI fragments from the plasmid proviral clones of SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 (pMneCl8) were exchanged. BstBI cleaves both proviruses in vif (position 5343, which is 536 bp into the vif gene), and SalI cuts in the polylinker region of both proviral plasmid clones at a site downstream of the cellular sequences flanking the 3′ LTR of each provirus. The chimeric virus that consisted of the 5′ half of SIVMne027 and 3′ half of SIVMneCl8 was designated SIVMne027/Cl8, and the reciprocal virus was designated SIVMneCl8/027.

Generation of virus stocks.

Ten million CEMx174 cells were transfected with 10 μg of each plasmid proviral construct by the DEAE-dextran method and cultured for 10 days in RPMI complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated [56°C for 30 min] fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin [100 U/ml], streptomycin [100 μg/ml], and amphotericin B [250 ng/ml]). Conditioned supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm in a Beckman clinical centrifuge, filtered through 0.22-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and stored in 1-ml aliquots at −70°C. The tissue culture infectious dose (TCID) of each virus supernatant stock per milliliter was determined by the sMAGI assay (9). Briefly, sMAGI indicator cells were infected with 1 to 50 μl of viral supernatant and stained for β-galactosidase expression 3 days postinfection (p.i.) as previously described (9).

Infection of human CD4+ cell lines.

The human CD4+ T-cell lines Jurkat, CEM, MT4, and Molt4 clone 8, and a CD4+ T-B-cell hybrid cell line, CEMx174, were maintained in RPMI complete medium. To examine viral tropism for these cell lines, triplicate cultures of 5 × 105 cells from each line were infected with 1,000 TCID of each virus derived from the molecular clones of SIVMne and propagated in 2 ml of RPMI complete medium. Every 3 days, the total cell number in each culture was adjusted to 5 × 105, and fresh medium was added. If there were cytopathic effects in a culture that reduced the total cell number below 5 × 105, then no cells were removed, but the culture medium was replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium. At 6, 12, and 18 days p.i., 1 ml of supernatant from each culture was removed and stored at −70°C. Viral replication was assessed by examining the supernatants for cell-free SIV p27gag by antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for the SIV p27gag capsid protein (Immunotech, Westbrook, Maine). Cultures were scored positive for viral replication if the cell-free supernatants taken at 12 and 18 days p.i. were positive for SIV p27gag (>50 pg/ml).

Replication and cytopathicity of SIVMne variants in CEMx174 cells.

To compare the replication rates and cytopathicity of the different viruses in the CEMx174 cell line, duplicate cultures of 8 × 105 CEMx174 cells were infected with 200 TCID of each virus for 4 h in RPMI complete medium. Following the incubation, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual free virions, and resuspended in 2 ml of fresh RPMI complete medium. Every 2 to 3 days, both the viable and total cell numbers were determined by trypan blue dye exclusion, and the total syncytia per culture were counted by visual inspection. Only syncytia larger than 5 cell diameters were scored. Viral replication was monitored by assaying dilutions of the culture supernatants for cell-free SIV p27gag by antigen ELISA. All p27gag values were obtained in the linear range of the assay. The cell number in each culture was adjusted to 8 × 105, and fresh RPMI complete medium was added to a final volume of 2 ml. If the cell number was below 8 × 105, then no cells were removed, but the culture medium was replaced with 2 ml of fresh RPMI complete medium.

Isolation and infection of macaque PBMCs, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells.

Macaque PB mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood of SIV- and simian type D retrovirus-negative pig-tailed macaques (M. nemestrina) by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation as previously described (50). To examine viral replication in nonstimulated PBMCs (i.e., in the absence of exogenous mitogens) or interleukin-2 (IL-2)-stimulated PBMCs, 3 × 106 PBMCs were infected with 6,000 TCID of each virus in duplicate in 1 ml of RPMI complete medium. Following a 24-h incubation, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in RPMI complete medium. Nonstimulated PBMC cultures were grown continuously in the absence of exogenous IL-2, while IL-2-stimulated PBMC cultures were grown continuously in the presence of exogenous IL-2 (20 U/ml) for the duration of the experiment. Every 3 to 4 days, supernatants were harvested, stored at −70°C, and used to monitor viral replication by antigen ELISA for p27gag.

To examine viral replication in PBMCs prestimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA), PBMCs were cultured with 10 μg of PHA-P (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) per ml in RPMI complete medium for 3 days. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation and washed with RPMI complete medium to remove the PHA, and duplicate cultures of 2 × 106 cells were infected with 2,000 TCID of each virus in 1 ml of RPMI complete medium plus 20 U of recombinant human IL-2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) per ml. The following day, the cells were pelleted, washed with PBS twice to remove residual cell-free virions, and resuspended in RPMI complete medium supplemented with 20 U of IL-2 per ml. Every 3 days, culture supernatant was removed and replaced with fresh RPMI complete plus IL-2 (20 U/ml). The supernatants were stored at −70°C and used to monitor virus replication by assaying for cell-free SIV p27gag antigen by ELISA.

To analyze the cytopathicity of the viruses for CD4+ T cells, 4 × 106 PBMCs were infected with each virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) ranging from 0.001 to 0.1. Over a 14-day period, the percentage of CD4+ T cells in each of the cultures was monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis using a Becton Dickinson FACScan. For the analysis, 30,000 viable cells were counted. Forward and side scatter light characteristics were used to exclude dead cells from the analysis. Anti-human CD4 and anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) that cross-react with macaque CD4 and CD8, respectively, were used for enumeration in addition to an anti-macaque CD3 monoclonal antibody obtained from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.).

Monocytes/macrophages were isolated from macaque PBMCs by adherence to plastic tissue culture flasks (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.), cultured for 5 days in macrophage medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated [56°C, 30 min] human AB serum, 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 10% GCT conditioned medium [obtained from the AIDS Research Reagent and Reference Program], 2 mM glutamine, penicillin [100 U/ml], streptomycin [100 mg/ml], and amphotericin B [250 ng/ml]), and infected as previously described (50). Duplicate cultures were infected with each virus at an MOI ranging from 0.001 to 0.1. Viral replication was monitored by assaying supernatants taken at 3- to 4-day intervals p.i. for the presence of SIV p27gag by ELISA.

Enriched populations of primary macaque T cells were isolated from PBMCs by a modification of the method used by Polacino et al. (46). Macaque PBMCs were first cultured for 2 h in RPMI complete medium, using Corning T75 flasks to remove the adherent population of cells. The nonadherent cell population was concentrated by centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium, loaded onto a 30%/40%/60% Percoll step gradient, and spun at 2,900 rpm in a Beckman clinical centrifuge for 20 min at 4°C. Cells at the 40%/60% interphase were recovered, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in RPMI complete medium. By FACS analysis, this cell population contained mainly T cells (>98% CD3+). The T cells (1.5 × 106/culture) were infected in 1 ml of RPMI complete medium with each virus at an MOI of 0.001. After 24 h, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 2 ml of RPMI complete medium. Every 3 days, 1 ml of conditioned supernatant from each culture was removed and stored at −70°C to monitor viral replication by ELISA for SIV p27gag.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of SIVMne027 was entered into GenBank under accession no. U79412.

RESULTS

Isolation of an infectious molecular clone of SIVMne from LN tissue.

To study the properties of viruses found in LNs, we first isolated a proviral clone directly from unpassaged LN tissue of a pig-tailed macaque (animal T78027) that had been infected with an uncloned, pathogenic isolate of SIVMne (5). Macaque T78027 had been infected with SIVMne for 16 months and had declining CD4+ T-cell counts and early signs of AIDS at the time of the LN biopsy. Using recombinant lambda phage cloning, we obtained a single full-length proviral variant of SIVMne, designated SIVMne027, from this animal’s LN DNA sample. CEMx174 cells transfected with the proviral clone of SIVMne027 expressed virus that was infectious for macaque and human cells (Table 1). The host cell range of SIVMne027 was similar to that of SIVMneCl8, a pathogenic virus that was cloned from the SIVMne isolate that was inoculated into macaque T78027 (4, 38, 43). SIVMne027 replicated in pig-tailed macaque PBMCs and to low levels in macaque monocytes/macrophages. It also replicated in the human CD4+ cell lines CEMx174 and MT4. However, the host range of SIVMne027 was different from those of uncloned mixtures of late variant viruses previously isolated from PBMCs of other pig-tailed macaques with AIDS. These uncloned mixtures of late variants had an expanded host range for CD4+ human cell lines that included Molt4 clone 8, but they replicated poorly or not at all in monocyte/macrophage cultures (Table 1 and reference 50).

TABLE 1.

Replication and tropism of SIVMne027a

| Virus | Viral replication

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC | mMφ | CEMx174 | Jurkat | CEM | MT4 | Molt4 clone 8 | |

| SIVMneCl8 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| SIVMne027 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| SIVMne variants | + | +/− | + | NT | NT | NT | + |

The cultures were scored positive (+) for viral replication if, during the 3-week culture period, the cell-free supernatants were positive for SIV p27gag by antigen ELISA. A minus sign indicates that SIV p27gag was not detected at any time point during the culture period. NT, not tested. PBMC and monocyte-derived macrophages (mMφ) were prepared from SIV- and simian type D retrovirus-negative pig-tailed macaques. The replication and tropism of the uncloned SIVMne variant mixture (M87004 170 week [PBMC]) were previously reported (50) but are shown for comparison.

SIVMne027 is rapidly replicating and highly cytopathic but non-syncytium inducing.

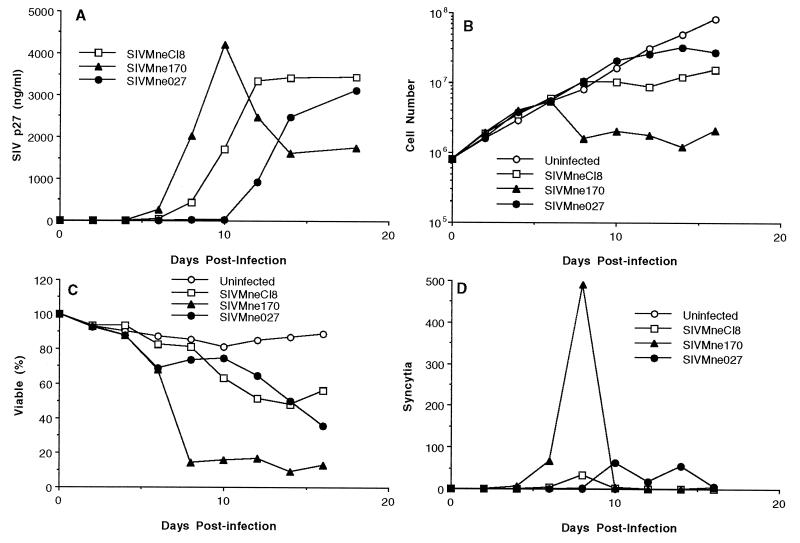

We previously demonstrated that CEMx174 cells are highly sensitive to the cytopathic effects of SIV and can be used as an indicator for the identification of rapid-high/SI variants of SIVMne (50). To determine the biological characteristics of SIVMne027, we compared its replication kinetics, cytopathicity, and syncytium-inducing ability in CEMx174 cells with those of SIVMneCl8, a slow-low/NSI virus (50), and SIVMne170, a rapid-high/SI virus molecularly derived from an uncloned mixture of late variant viruses isolated by cocultivation from PBMCs (31). The phenotype of SIVMneCl8 is typical of viruses present early in infection, while the phenotype of SIVMne170 is representative of variants found late in infection (50). When CEMx174 cells were infected with each virus at a low MOI (0.00025), SIVMne027 replicated with delayed kinetics compared to SIVMneCl8 and SIVMne170, reaching a peak SIV p27gag antigen later than SIVMneCl8 and SIVMne170, respectively (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, SIVMne027 was minimally cytopathic for CEMx174 cells, a phenotype similar to that of SIVMneC18 (Fig. 1B and C); specifically, it reduced the viable cell number fivefold and percentage of cells that were viable to 40%. In contrast, the rapid-high/SI virus, SIVMne170, reduced the viable cell number approximately 100-fold and the percentage of viable cells to less than 10%. Increasing the MOI to 0.025 or greater did not enhance the cytopathicity of SIVMne027 (data not shown). Finally, like SIVMneC18, SIVMne027 induced few syncytia compared to SIVMne170 (Fig. 1D). Syncytia were not observed in any other infected cell lines, including MT4 (data not shown). By these criteria, SIVMne027 is a slow-low/NSI variant of SIVMne.

FIG. 1.

Replication and cytopathicity of SIVMne027 in CEMx174 cells. Eight hundred thousand CEMx174 cells were infected with 200 TCID of virus. At 2-day intervals p.i., supernatants were harvested to monitor viral replication by antigen ELISA for SIV p27gag. The viable cell number was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion, and syncytia were scored as described in Materials and Methods. (A) SIV p27gag levels versus days p.i.; (B) extrapolated viable cell number versus days p.i.; (C) percentage of the total number of cells that are viable versus days p.i.; (D) total number of syncytia versus days p.i. The value shown for each time point is the average of duplicate cultures. Similar data were obtained in three independent experiments.

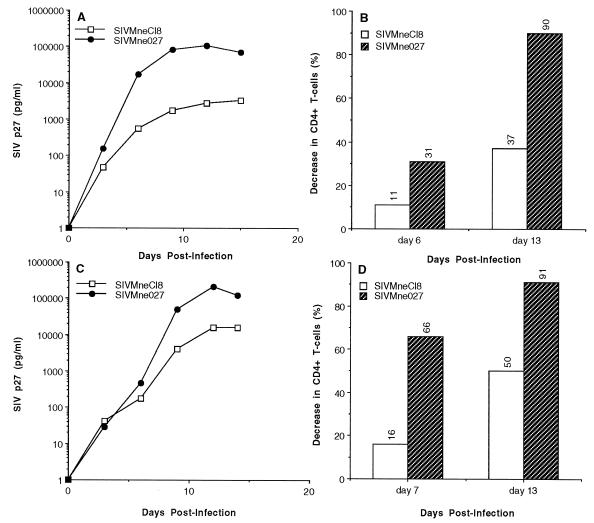

Differences in the replication kinetics and cytopathicity of SIV and HIV-1 have been elucidated in cultures of PBMCs prestimulated with PHA (1, 12, 14–16, 23, 58–60, 63). Thus, to further characterize SIVMne027, we examined its phenotype in PHA-stimulated macaque PBMCs. SIVMne027 replicated to a 50-fold-higher level than SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 2A), and it replicated with the most rapid kinetics of any SIVMne variant examined to date (data not shown). Furthermore, the CD4+ T-cell (CD3+ CD4+) population in infected PBMC cultures was decreased to a greater extent by SIVMne027 (37% at day 6 and 90% at day 13 p.i.) than SIVMneCl8 (11% at day 11 and 31% at day 14) infection (Fig. 2B). The decrease in CD4+ cells in the infected cultures was not simply due to down regulation of CD4 expression on the surface of cells. It was more likely caused by a depletion of the CD3+ CD4+ cell population because almost all of the CD3+ CD4− cell population expressed CD8 (data not shown). These observations were confirmed in assays using PBMCs isolated from a second macaque (Fig. 2C and D). In PBMCs from this animal, SIVMneCl8 replicated to a fivefold-higher level than in the PBMCs from the first donor. However, SIVMneCl8’s maximum p27gag level was still 15-fold lower than that achieved by SIVMne027, and its highest level of CD4+ T-cell killing was also significantly less than that for SIVMne027. Similar results were obtained with different MOIs over a 100-fold range and in multiple independent experiments using PBMCs isolated from two other pig-tailed macaques (data not shown). In all experiments, SIVMne027 was consistently more cytopathic than SIVMneCl8. However, the extent of cell killing was different for each experiment and was dependent on the donor PBMCs as well as the MOI. The decrease in the CD4+ T-cell population at 2 weeks p.i. ranged from 10 to 50% for SIVMneCl8-infected PBMCs and from 65 to 92% for SIVMne027-infected PBMCs. Last, syncytia were not observed in any of the infected PBMC cultures (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate that SIVMne027 is a non-syncytium-inducing virus in both macaque PBMCs and a CD4+ cell line, but it is rapidly replicating in macaque PBMCs and is highly cytopathic for the CD4+ T-cell population. Additionally, they suggest that an increase in the replication kinetics and cytopathicity of SIV can evolve independent of the syncytium-inducing property.

FIG. 2.

Replication and cytopathicity of SIVMne027 in PHA-stimulated macaque PBMCs. (A and C) SIV p27gag levels versus days p.i. Two million PHA-stimulated PBMCs were infected with 2,000 TCID of virus in duplicate. Virus production was monitored by antigen ELISA for SIV p27gag. The average antigen value for the duplicate cultures at each time point is shown, and the viruses used for infection are indicated. (B and D) Decrease in CD4+ T cells versus days p.i. Four million PHA-stimulated PBMCs were infected with 40,000 TCID of virus. The decrease in CD4+ T cells at the indicated time point (6 and 13 days p.i.) was monitored by FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The values in panels B and D represent the decrease in the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ cells in the virus-infected cultures relative to the uninfected culture at each time point.

SIVMne027 replicates in nonstimulated PBMCs.

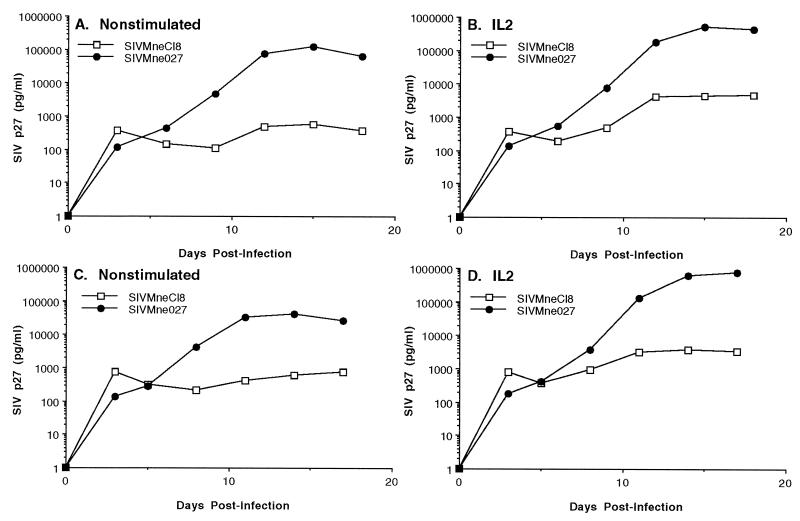

A few studies have investigated the ability of HIV-1 and SIV to replicate in leukocyte cultures or PBMCs that had not been stimulated with potent mitogens such as PHA or concanavalin A (17, 20, 25, 32, 33, 47, 48, 61). To determine the efficiency of replication of SIVMne027 in PBMC cultures that had not been prestimulated with exogenous mitogens, we compared the replication kinetics of SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 in pig-tailed macaque PBMCs in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2. Interestingly, SIVMne027 replicated to significant levels in the nonstimulated PBMC cultures, whereas SIVMneCl8 replicated poorly (Fig. 3A and C). The addition of IL-2 at 24 h p.i. enhanced the production of p27gag in the SIVMne027-infected cultures 5- to 20-fold. In contrast, while the production of p27gag in the SIVMneCl8-infected cultures was also increased by IL-2, the highest level of p27gag was still 100- to 200-fold less than that attained by SIVMne027 (Fig. 3B and D). We observed these characteristics in seven independent experiments using PBMCs from three different pig-tailed macaques (data not shown). Furthermore, the PB-derived SIVMne variant clone, SIVMne170, behaved like SIVMneCl8 in nonstimulated PBMC cultures, demonstrating that among variants of the SIVMne strain, the ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs was unique to SIVMne027 (data not shown). These data demonstrate that SIVMne027 may have an increased capacity to replicate in PBMCs, and they also show that this virus is highly responsive to signals induced by IL-2. Additionally, the ability of SIVMne027 to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs appeared to occur without the induction of cellular proliferation because we could not detect a difference in cell number between infected and uninfected control PBMCs by the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide)] colorimetric assay. Furthermore, like infection with other variants of SIVMne, infection with SIVMne027 did not increase expression of the T-cell activation marker CD69 or CD25. These data suggest that virus production may not involve CD3+ lymphocytes. However, selection for CD3+ cells from SIVMne027-infected PBMC cultures by immunomagnetic bead separation using an anti-macaque CD3 monoclonal antibody and subsequent analysis of the CD3+ cells by antigen ELISA for p27gag or PCR for proviral DNA demonstrated that the T-cell population was productively infected (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Replication of SIVMne027 in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated pig-tailed macaque PBMCs. Three million nonstimulated PBMCs were infected with 6,000 TCID of virus and cultured in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2. Virus production was monitored by antigen ELISA for SIV p27gag. Each antigen value is the average of duplicate cultures. (A and C) Virus production from nonstimulated PBMCs. (B and D) Virus production from IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. IL-2 was added 24 h p.i. and was maintained at 20 U/ml for the duration of the experiment. Panels A and B and panels C and D represent independent experiments using PBMCs prepared from different pig-tailed macaques.

Comparison of the replication kinetics of SIVMne027 and other SIV clones.

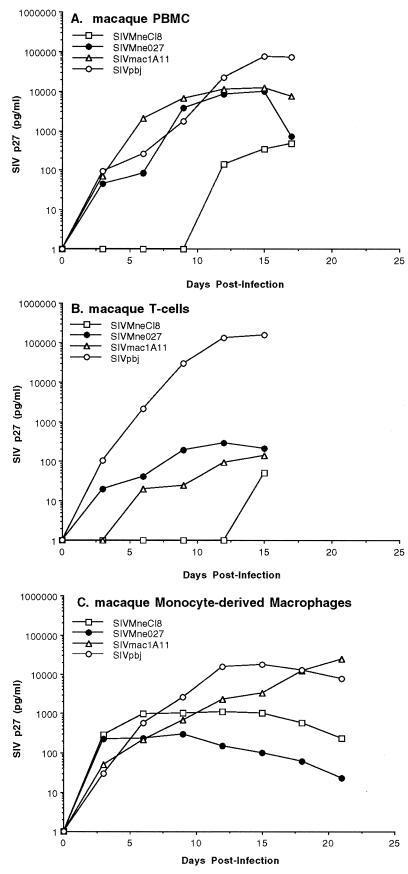

To further characterize SIVMne027, we compared its ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs with those of a molecular clone of the immunostimulatory viral isolate, SIVPBj14 (clone SIVPBj1.9 [16]), and a highly macrophage-tropic clone, SIVmac1A11 (3), as well as SIVMneCl8. SIVMne027, SIVPBj1.9, and SIVmac1A11 replicated to substantial levels in nonstimulated PBMCs compared to SIVMneCl8 as measured by SIV p27gag antigen production (Fig. 4A). The peak SIV p27gag antigen level achieved in the SIVMne027- and SIVmac1A11-infected cultures was approximately 10,000 pg/ml, while the SIVPBj14-infected cultures produced a sevenfold-higher maximal level of antigen (72,000 pg/ml). In contrast, the SIVMneCl8-infected cultures reached a maximum SIV p27gag level at 300 pg/ml.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the replication kinetics of SIVMne027 and of other strains of SIV in nonstimulated macaque PBMCs and macaque T-cell-enriched cultures. (A) Virus production from nonstimulated macaque PBMCs. The infection and analysis were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (B) Virus production from primary macaque T-cell cultures. Cultures of T cells were infected with each virus at an MOI of 0.001. (C) Virus production from macaque monocyte-derived macrophage cultures. Monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were infected with each virus at an MOI of 0.001. For panels B and C, virus production was monitored by SIV p27gag antigen ELISA, and cultures were maintained as described in Materials and Methods.

To further characterize the phenotype SIVMne027, we examined whether the virus could replicate in cultures enriched for macaque resting T lymphocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages. Virus replication was low in resting T-cell cultures infected with SIVMne027, similar to the cultures infected with SIVmac1A11, while SIVMneCl8 replication was undetectable (Fig. 4B). By contrast, SIVPBj1.9 efficiently replicated in resting T-cell cultures in the absence of the monocyte/macrophage population. In monocyte-derived macrophage cultures, SIVMne027 replicated to a low level, three- to fourfold lower than the level achieved by SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, both SIVmac1A11 and SIVPBj1.9 replicated efficiently and to high levels in these monocyte-derived macrophage cultures, as previously demonstrated by Banapour et al. (3) and Fletcher et al. (24), respectively. Together, these data demonstrate that SIVMne027’s requirements for replication in nonstimulated PBMC cultures are different from those of SIVPBj, which replicates efficiently in both resting T cells and monocytes/macrophages, and SIVmac1A11, which efficiently replicates in monocytes/macrophages. SIVMne027, instead, requires both the T-cell and monocyte/macrophage populations for high-level replication in nonstimulated macaque PBMCs, suggesting that T-cell–macrophage interactions are important for stimulating SIVMne027 replication.

Genetic comparison of SIVMne027 with other SIVs.

We determined the sequence of the entire SIVMne027 genome and compared the predicted amino acid sequences of the gene products with the homologous regions of SIVMneCl8, SIVPBj14 (16), SIVmac1A11 (35), and a prototype AIDS-inducing SIV clone, SIVmac239 (30, 35) (Table 2). SIVMne027 encodes a complete open reading frame for each gene. SIVMne027 had the strongest sequence similarity to SIVMneCl8; the percentage of amino acid differences ranged from a low value of 0.7% in reverse transcriptase (RT) and integrase (IN) to a high value of 4.0 to 5.3% in Vpr, Tat, Rev, and Nef. In contrast, SIVMne027 differed overall from SIVPBj14 by 12.7%. SIVMne027 was most similar to SIVPBj14 in IN (3.8% different) and most different in Env, Vif, Tat, Rev, and Nef (17.3 to 24.6%). Our sequence analysis also revealed that SIVMne027 did not have an additional Src homology 2 (SH2) binding motif (YXXL) in Nef or a duplication of the NF-κB binding site in the U3 LTR region (data not shown), two of the known determinants of SIVPBj14 that contribute to its ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs (16–19). Additionally, SIVMne027 differed from SIVmac239 and SIVmac1A11 by a greater percentage than SIVMneCl8 in each viral protein, except Vpx, which was identical. However, both SIVmac239 and SIVmac1A11 had fewer amino acid differences with SIVMne027 than did SIVPBj14. Finally, SIVMne027 was also found to be genetically distinguishable from other clones of SIV and HIV-1 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Percentages of amino acid differences between SIVMne027 and other SIVs

| Viral protein | % Amino acid difference

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIVMneCl8 | SIVmac239 | SIVmac1A11 | SIVPBj14 | |

| Gag | 2.5 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 8.4 |

| Pol | ||||

| Protease | 2.8 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 12.0 |

| RT | 0.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 5.5 |

| IN | 0.7 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.8 |

| Env | 2.9a | 8.5 | 8.8a | 19.2 |

| Vif | 2.3 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 17.3 |

| Vpx | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 9.8 |

| Vpr | 4.0 | 6.9 | 11.0a | 8.9 |

| Tat | 4.6 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 24.6 |

| Rev | 4.7 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 22.4 |

| Nef | 5.3 | 13.3a | 14.8 | 22.1 |

The protein is predicted to be truncated due to a premature stop codon in the sequence of the gene. The premature stop codons were considered single mutations, and the predicted amino acid sequences encoded downstream from these stop codons were included in the calculations.

Replication of SIVMne027 in nonstimulated PBMCs requires a determinant located within the 5′ half of the viral genome.

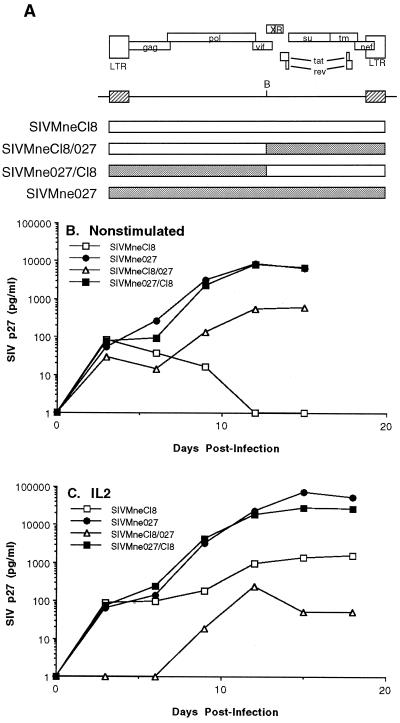

To identify the determinant in SIVMne027 that confers the ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMC cultures, we constructed reciprocal recombinant proviruses that exchange the 5′ and 3′ regions of SIVMne027 and the parental virus, SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 5A), and compared the abilities of viruses derived from these constructs to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. When nonstimulated PBMCs were infected with these viruses, similar patterns of replication were observed in the cultures infected with the wild-type SIVMne027 and the chimeric virus, SIVMne027/Cl8, which encodes the R-U5-gag-pol-5′vif region of SIVMne027 and 3′vif-vpx-vpr-tat-rev-env-nef-U3-R region from SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the reciprocal clone, SIVMneCl8/027, resembled SIVMneCl8 in that it did not show an appreciable level of virus replication as measured by p27gag expression. Furthermore, the SIVMne027/Cl8 chimeric virus was responsive to the addition of IL-2. However, its peak production of p27gag was approximately threefold lower than that of SIVMne027 (Fig. 5C). The SIVMneCl8/027 chimera, like SIVMneCl8, produced only a low level amount of p27gag under these conditions. These results indicate that the 3′ region of SIVMne027, including nef and the U3-R region of the LTR, does not contain the primary determinants for replication in nonstimulated or IL-2-stimulated PMBCs. Instead, the primary determinant(s) that confers SIVMne027’s ability to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs lies in a region of the 5′ half of the virus, which includes U5-gag-pol and the 5′ end of vif.

FIG. 5.

Construction and analysis of SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 chimeric viruses. (A) Schematic diagram of the chimeric viruses. B, the BstBI restriction site used for generation of the chimeric viruses. (B) Virus production from nonstimulated PBMCs. (C) Virus production from IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. For panels B and C, infection of PBMCs and the analysis of virus production were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 3 and Materials and Methods.

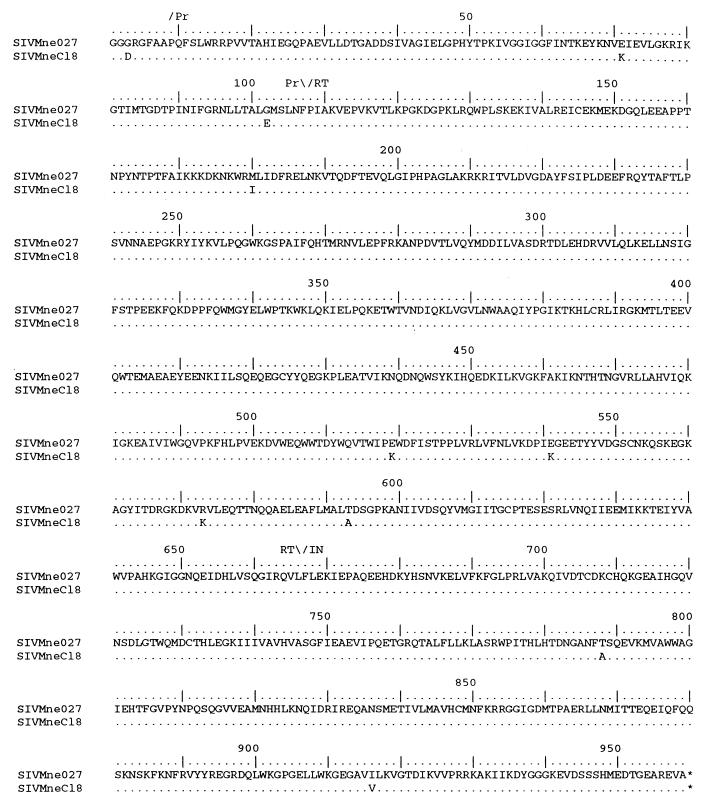

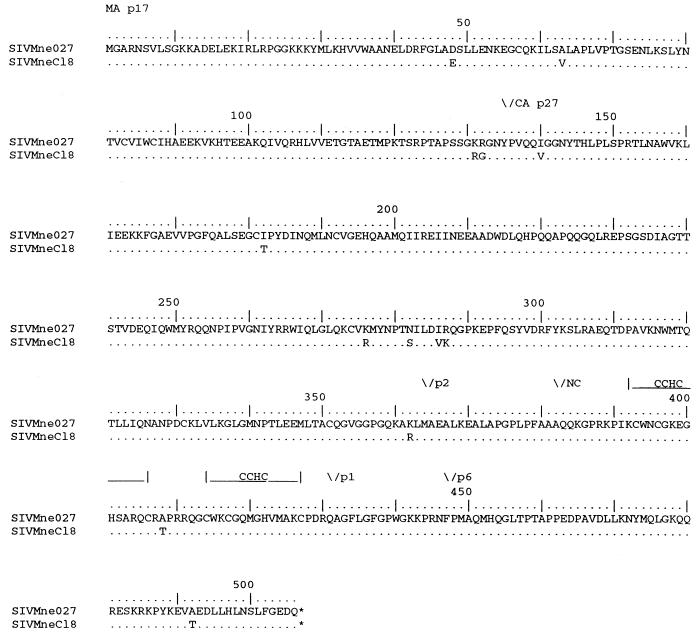

The U5, Gag, Pol, and amino-terminal Vif sequences from SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 were further analyzed to determine more specifically which 5′ region of SIVMne027 may contain the determinant conferring the ability to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. The analysis revealed that the SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 U5 sequences and the untranslated region upstream of the gag translational initiation codon were highly conserved. There were four nucleotide differences, all were located in U5; none was in the primer binding site (data not shown). Pol was also highly conserved (99.1% identical) (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Only one of the amino acid differences (position 573 in RT, Lys to Arg) occurred at a position that is conserved among the SIVs, including SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 6 and reference 39). On the other hand, the Gag sequence of SIVMne027 differed from that of SIVMneCl8 by 2.5% and contained conservative and nonconservative amino acid differences at nine positions (amino acids 48, 63, 132, 182, 276, 286, 287, 362, and 492) that are conserved among other SIVs, including SIVMneCl8 (Fig. 7 and reference 39). Finally, while there were four amino acid differences (Glu-64, Tyr-85, Tyr-104, and Asn-143) between SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8 in the amino-terminal region of Vif, a comparison with the Vif protein of other SIVs revealed that none of the mutations were unique to SIVMne027 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences of Pol from SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8. The predicted amino acid sequence of SIVMne027 Pol serves as the reference. The regions encoding protease (Pr), RT, and IN are shown above the sequences. Similarities and differences between SIVMne027 Pol and the other SIV Pol proteins are shown with the same notation as described in the legend to Fig. 5.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences of Gag from SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8. The regions coding for MA, CA, and NC are indicated above the sequences. Amino acid similarities and differences are noted as described in the legend to Fig. 5.

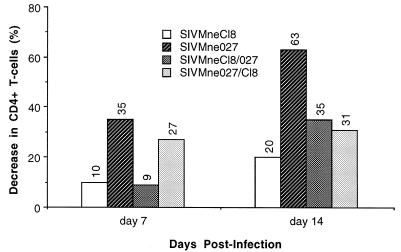

To examine whether the determinants in SIVMne027 that enhanced replication were also responsible for its cytopathicity, we also examined the cytopathic properties of the recombinant viruses in PHA-stimulated PBMCs (Fig. 8). Both chimeric viruses, SIVMne027/Cl8 and SIVMneCl8/027, were less cytopathic than the parent virus SIVMne027, which reduced the CD4+ T-cell population by 35 and 63% after 7 and 14 days of infection, respectively, in this experiment. SIVMne027/Cl8 depleted 27% of the CD4+ T cells by 7 days postinfection; by day 14, this value had increased to only 31%. The reciprocal virus SIVMneCl8/027 killed 9% of the CD4+ T-cell population after 7 days of infection and 35% by 14 days p.i. Although both chimeric viruses were less cytopathic than SIVMne027, they were more cytopathic than the parent virus, SIVMneCl8, which reduced the CD4+ T-cell population by 10 and 20% after 7 and 14 days of infection, respectively. Thus, determinants in both halves of SIVMne027 may contribute to its cytopathicity.

FIG. 8.

Cytopathicity of the chimeric viruses for PHA-stimulated PBMCs. Four million PBMCs prestimulated with PHA for 3 days were infected with 40,000 TCID and cultured in RPMI complete medium and IL-2 (20 U/ml). Cytopathicity of the viruses for CD4+ T cells was monitored by FACS as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

The predominant SIV variants in lymphoid tissue have been shown to be genetically different from those found in the peripheral blood of infected macaques (8). To begin to evaluate the contribution of LN-derived lentivirus variants to viral pathogenesis, we molecularly cloned a variant of SIV directly from DNA prepared from unpassaged LN tissue of a pig-tailed macaque inoculated with SIVMne. Importantly, this is the first infectious HIV-1 or SIV molecular clone isolated directly from unpassaged LN tissue. The virus, SIVMne027, displayed a distinct phenotype in culture compared to other SIVMne clones. SIVMne027 was macrophage-tropic, replicated poorly in T-cell lines, and was non-syncytium inducing. However, it replicated efficiently in PHA-stimulated PBMCs and was highly cytopathic for the CD4+ T-cell population. Interestingly, SIVMne027 also replicated efficiently in nonstimulated PBMCs in the absence of potent mitogens (e.g., PHA or concanavalin A), and it was responsive to IL-2 under these culture conditions. These data demonstrate that in SIV- and, by implication, HIV-1-infected individuals, LNs may harbor cytopathic variant viruses with an increased ability to utilize, and perhaps deregulate, cellular activation signals that are typically required for viral replication.

We previously demonstrated that SIVMne, like HIV-1, evolves from a slow-low/NSI virus to a rapid-high/SI virus population during the course of an infection (50). Interestingly, the primary determinant that conferred the rapid replication kinetics and increased cytopathic effects of a rapid-high/SI SIVMne variant molecular clone mapped to gag, but not the syncytium induction determinant, which mapped to the envelope surface protein coding region (31, 51), suggesting that rapidly replicating, highly cytopathic SIVMne variants may evolve independent of the syncytium-inducing phenotype. The data presented here demonstrate that a SIVMne variant, SIVMne027, can be rapidly replicating and highly cytopathic in the absence of an overt syncytium-inducing phenotype. The experimental inoculation of macaques with SIVMne027 will allow us to directly examine whether the increased in vitro virulence of SIVMne027 is predictive of increased in vivo pathogenicity. Furthermore, comparative studies of SIVMneCl8 and SIVMne027 may allow us to further define the viral genetic determinants and in vitro biological characteristics of virulence. In regard to the latter, it is noteworthy that the chimeric viruses, SIVMne027/Cl8 and SIVMneCl8/027, were less cytopathic for CD4+ T cells in PHA-stimulated PBMCs and replicated less efficiently than the parent virus SIVMne027 in IL-2-stimulated PBMCs, demonstrating that determinants in both halves of the virus may contribute to its overall virulence.

Unlike other SIVMne clones, SIVMne027 replicated efficiently in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. SIVMne027’s ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs initially appeared to be similar to that of the immunostimulatory virus, SIVPBj14. However, SIVMne027 was distinguishable from SIVPBj14 by several criteria. First, in contrast to the molecular clone of SIVPBj14, SIVPBj1.9, SIVMne027 did not replicate well in either macaque resting T-cell or monocyte-derived macrophage-enriched cultures; instead, it required the presence of both cell populations for efficient replication. Second, SIVMne027 did not contain either a duplication of the NF-κB site in the U3 region of the LTR or an additional YXXL motif in the amino-terminal region of Nef, two mutations that have been shown to be critical for the phenotype of SIVPBj14 (16–20). We further verified that mutations in these regions of SIVMne027 were not the primary determinants conferring the ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs with recombinant viruses. Third, SIVMne027 was slowly replicating and minimally cytopathic in CEMx174 cells, whereas SIVPBj14 has been shown to be highly cytopathic for this cell line (16). Fourth, while SIVPBj14 is able to induce T-cell proliferation (25), we could not detect an increase in lymphocyte proliferation in SIVMne027-infected PBMCs by the MTT assay in preliminary experiments. We also could not detect an up regulation of the T-cell activation markers CD69 and CD25 on CD4+ T cells in SIVMne027-infected cultures. Nevertheless, we did find infected CD3+ lymphocytes, demonstrating the importance of T cells in SIVMne027 replication in nonstimulated PBMC cultures. These data suggest that SIVMne027 may either induce immune activation signals that are sufficient for viral replication but not cellular proliferation or bypass the requirement for T-cell activation. However, IL-2 enhanced SIVMne027 production from infected PBMCs. This observation indirectly suggests that the SIVMne027-infected cells may be activated, because resting T cells are refractory to the effects of IL-2 (56). Our failure to detect T-cell activation in SIVMne027 infected-cultures by other methods, such as FACS, may be explained by a high rate of turnover of productively infected CD3+ CD4+ T cells. This interpretation is consistent with our data demonstrating that SIVMne027 is highly cytopathic for the CD3+ CD4+ T cells. Together, these data demonstrate that SIVMne027 is genetically and phenotypically distinct from SIVPBj14.

Cell-cell interactions play an important role in regulating lentivirus replication. Several recent studies have demonstrated that efficient replication of both SIV and HIV-1 requires contact between mononuclear phagocytes or antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophages or dendritic cells, and T cells (32, 33, 47, 48, 61). Furthermore, introduction of an additional SH2 binding domain into the amino-terminal region of Nef of SIVmac239 results in a virus (SIVmac239YE) that is capable of replicating in nonstimulated PBMCs in a macrophage-dependent manner (20). We demonstrate here that SIVMne027, like the SIVmac239YE mutant (20) but unlike SIVPBj1.9, depends on monocytes/macrophages for efficient replication in nonstimulated PBMCs. SIVMne027 also appeared to resemble the macrophage-tropic virus, SIVmac1A11, in its ability to replicate in nonstimulated PBMCs because SIVmac1A11 required the monocyte/macrophage population. However, SIVMne027 differed from SIVmac1A11 because it replicated poorly in cultures enriched for monocyte-derived macrophages, whereas SIVmac1A11 replicated to a high level. Indeed, replication of SIVmac1A11 in nonstimulated PBMCs could be explained entirely by macrophage infection. By contrast, the level of SIVMne027 replication in monocyte-derived macaque macrophages is too low to account for the high-level replication in nonstimulated macaque PBMCs. Therefore, it seems unlikely that replication of SIVMne027 in the monocyte/macrophage population alone can fully explain its ability to replicate to high levels in nonstimulated PBMCs. In support of this interpretation, we demonstrated here and have previously shown that both SIVMneCl8 and SIVMne170 replicated with kinetics similar to those of SIVMne027 in monocyte-derived macrophage cultures (31, 50, 51), but neither virus replicated to appreciable levels in either nonstimulated or IL-2-stimulated PBMCs, further suggesting that macrophage infection is insufficient for viral replication in nonstimulated or IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. A model consistent with our data is that SIVMne027 has a greater capacity to utilize activation signals resulting from mononuclear phagocyte–T-cell interactions for replication than the other molecular variants of SIVMne. Although the significance of the SIVMne027 phenotype is unclear, the selection for viruses during infection that are highly responsive to cellular activation signals seems plausible, especially because persistent SIV and HIV-1 replication correlates with immune activation and disease progression (22, 36, 42, 49, 54), productive infection of CD4+ T cells requires activation signals (7, 46, 57, 64), and vaccinations or secondary infections elevate viral loads in HIV-1-infected individuals (11, 13, 55).

The primary determinant(s) conferring the ability of SIVMne027 to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs lies within gag-pol-5′vif. While we have not identified the specific mutation(s) that determine the ability of SIVMne027 to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs in a functional assay, a U5, Pol, or Vif determinant seems unlikely because these regions are highly conserved between SIVMne027 and SIVMneCl8. On the other hand, the Gag polyprotein of SIVMne027 encodes nine unique mutations that distinguish it from SIVMneCl8 and other SIVs, making it a more likely candidate for the determinant that confers SIVMne027’s ability to replicate in nonstimulated and IL-2-stimulated PBMCs. Interestingly, Novembre et al. showed, using recombinant viruses between SIVPBj clones and the closely related clones SIVsmmH4 and SIVsmmH9, that mutations in gag and the central region of the proviral genome which encodes for regulatory genes affect the phenotype of SIVPBj14 (40, 41). Our data further underscore the influence that mutations selected in genes located in the 5′ half of the viral genome exert on viral replication. Identification of the specific mutations and the mechanism of action will be important for understanding how variation in gag, pol, or vif affects viral replication in vitro and the impact that this may have on virus replication and pathology in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jen Rohn and Mary Poss for critical reviews of the manuscript. The CEMx174 cell line and GCT conditioned medium were obtained from the AIDS Research Reagent and Reference Program. Virus stocks of SIVmac1A11 were kindly provided by Marta Marthas.

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 AI34251. J.T.K. was supported in part by NIH training grants T32 CA09229 and T32 AI07140 and NRSA individual postdoctoral fellowship F32 AI09337. J.O. is a scholar of the Leukemia Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Åsjö B, Albert J, Karlsson A, Morfeldt-Manson L, Biberfeld B, Lidman K, Fenyö E M. Replicative capacity of human immunodeficiency virus from patients with varying severity of HIV infection. Lancet. 1986;ii:660–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Åsjö B, Cefai D, Debre P, Dudoit Y, Autran B. A novel mode of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) activation: ligation of CD28 alone induces HIV-1 replication in naturally infected lymphocytes. J Virol. 1993;67:4395–4398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4395-4398.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banapour B, Marthas M L, Munn R J, Luciw P A. In vitro macrophage tropism of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVMAC) Virology. 1991;183:12–19. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90113-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benveniste R E, Hill R W, Eron L J, Csaikl U M, Knott W B, Henderson L E, Sowder R C, Nagashima K, Gonda M A. Characterization of clones of HIV-1 infected HuT 78 cells defective in gag gene processing and of SIV clones producing large amounts of envelope glycoprotein. J Med Primatol. 1990;19:351–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benveniste R E, Morton W R, Clark E A, Tsai C-C, Ochs H D, Ward J M, Kuller L, Knott W B, Hill R W, Gale M J, Thouless M E. Inoculation of baboons and macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus/mne, a primate lentivirus closely related to human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1988;62:2091–2101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2091-2101.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghi P, Fantuzzi L, Varano B, Gessani S, Puddu P, Conti L, Rosaria Capobianchi M, Ameglio F, Belardelli F. Induction of interleukin-10 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and its gp120 protein in human monocytes/macrophages. J Virol. 1995;69:1284–1287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1284-1287.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukrinsky M I, Stanwick T L, Stevenson M. Quiescent T lymphocytes as an inducible virus reservoir in HIV1 infection. Science. 1991;254:423–427. doi: 10.1126/science.1925601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell B J, Hirsch V M. Extensive envelope heterogeneity of simian immunodeficiency virus in tissues from infected macaques. J Virol. 1994;68:3129–3137. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3129-3137.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chackerian B, Haigwood N L, Overbaugh J. Characterization of a CD4-expressing macaque cell line that can detect virus after a single replication cycle and can be infected by diverse simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. Virology. 1995;213:386–394. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrabarti L, Cumont M-C, Montagnier L, Hurtrel B. Variable course of primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in lymph nodes: relation to disease progression. J Virol. 1994;68:6634–6642. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6634-6643.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheeseman S H, Davaro R E, Ellison R T., III Hepatitis B vaccination and plasma HIV-1 RNA. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng-Mayer C, Seto D, Tateno M, Levy J A. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science. 1988;240:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2832945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claydon E J, Bennett J, Gor D, Forster S M. Transient elevation of serum HIV antigen levels associated with intercurrent infection. AIDS. 1991;5:113–114. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199101000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor R I, Ho D D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased replicative capacity develop during the asymptomatic stage before disease progression. J Virol. 1994;68:4400–4408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4400-4408.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor R I, Mohri H, Cao Y, Ho D D. Increased viral burden and cytopathicity correlate temporally with CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline and clinical progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1993;67:1772–1777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1772-1777.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewhurst S, Embretson J E, Anderson D C, Mullins J I, Fultz P N. Sequence analysis and acute pathogenicity of molecularly cloned SIVSMM-PBj14. Nature. 1990;345:636–640. doi: 10.1038/345636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dittmar M T, Cichutek K, Fultz P N, Kurth R. The U3 promoter region of the acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus clone smmPBj1.9 confers related biological activity on the apathogenic clone agm3mc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1362–1366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dollard S C, Gummuluru S, Tsang S, Fultz P N, Dewhurst S. Enhanced responsiveness to nuclear factor κB contributes to the unique phenotype of simian immunodeficiency virus variant SIVsmmPBj14. J Virol. 1994;68:7800–7809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7800-7809.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du Z, Ilyinskii P O, Sasseville V G, Newstein M, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. Requirements for lymphocyte activation by unusual strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1996;70:4157–4161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4157-4161.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Z, Lang S M, Sasseville V G, Lackner A A, Ilyinskii P O, Daniel M D, Jung J U, Desrosiers R C. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell. 1995;82:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Embretson J, Zupancic M, Ribas J L, Burke A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Haase A T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fauci A S. Multifactorial nature of human immunodeficiency virus disease: implications for therapy. Science. 1993;262:1011–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.8235617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenyö E M, Morfeldt-Manson L, Chiodi F, Lind B, von Gegerfelt A, Albert J, Olausson E, Åsjö B. Distinct replicative and cytopathic characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus isolates. J Virol. 1988;62:4414–4419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4414-4419.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher T M, III, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman M A, Stivahtis G, Sharp P M, Emerman M, Hahn B H, Stevenson M. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIVsm. EMBO J. 1996;15:6155–6165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fultz P N. Replication of an acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus activates and induces proliferation of lymphocytes. J Virol. 1991;65:4902–4909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4902-4909.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gessani S, Puddu P, Varano B, Borghi P, Conti L, Fantuzzi L, Belardelli F. Induction of beta interferon by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and its gp120 protein in human monocytes-macrophages: role of beta interferon in restriction of virus replication. J Virol. 1994;68:1983–1986. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1983-1986.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannibal M C, Markovitz D M, Clark N, Nabel G J. Differential activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 transcription by specific T-cell activation signals. J Virol. 1993;67:5035–5040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5035-5040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeang K T, Gatignol A. Comparison of regulatory features among primate lentiviruses. Current Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;188:123–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78536-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kestler H, Kodama T, Ringler D, Marthas M, Pedersen N, Lackner A, Regier D, Sehgal P, Daniel M, King N, Desrosiers R. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimata J T, Overbaugh J. The cytopathicity of a simian immunodeficiency virus Mne variant is determined by mutations in Gag and Env. J Virol. 1997;71:7629–7639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7629-7639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinter A L, Poli G, Fox L, Hardy E, Fauci A S. HIV replication in IL-2-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells is driven in an autocrine/paracrine manner by endogenous cytokines. J Immunol. 1995;154:2448–2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight S C. Bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells and the pathogenesis of AIDS. AIDS. 1996;10:807–817. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy J A. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:183–289. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.183-289.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luciw P A, Shaw K E S, Unger R E, Planelles V, Stout M W, Lackner J E, Pratt-Lowe E, Leung N J, Banapour B, Marthas M L. Genetic and biological comparisons of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVMAC) AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:395–402. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merrill J E, Koyanagi Y, Chen I S Y. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor a can be induced from mononuclear phagocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding to the CD4 receptor. J Virol. 1989;63:4404–4408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4404-4408.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton W R, Benveniste R E, Clark E A, Tsai C-C, Gale M J, Thouless M E, Overbaugh J, Katze M G. Transmission of the simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmne in macaques and baboons. J Med Primatol. 1989;18:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myers G, Hahn B H, Mellors J W, Henderson L E, Korber B, Jeang K T, McCutchan F E, Pavlakis G N, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Novembre F J, Johnson P R, Lewis M G, Anderson D C, Klump S, McClure H M, Hirsch V M. Multiple viral determinants contribute to pathogenicity of the acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj variant. J Virol. 1993;67:2466–2474. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2466-2474.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novembre F J, Saucier M M, Hirsch V M, Johnson P R, McClure H M. Viral genetic determinants in SIVsmmPBj pathogenesis. J Med Primatol. 1994;23:136–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1994.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Brien W A, Hartigan P M, Martin D, Esinhart J, Hill A, Benoit S, Rubin M, Simberkoff M S, Hamilton J D, AIDS V A C S G O. Changes in plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ lymphocyte counts and the risk of progression to AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:426–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overbaugh J, Rudensey L M, Papenhausen M D, Benveniste R E, Morton W R. Variation in simian immunodeficiency virus env is confined to V1 and V4 during progression to simian AIDS. J Virol. 1991;65:7025–7031. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.7025-7031.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Demarest J F, Butini L, Montroni M, Fox C H, Orenstein J M, Kotler D P, Fauci A S. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 1993;362:355–358. doi: 10.1038/362355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polacino P S, Liang H A, Clark E A. Formation of simian immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat circles in resting T cells requires both T cell receptor- and IL-2-dependent activation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:617–621. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polacino P S, Liang H A, Firpo E J, Clark E A. T-cell activation influences initial DNA synthesis of simian immunodeficiency virus in resting T lymphocytes from macaques. J Virol. 1993;67:7008–7016. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7008-7016.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pope M, Betjes M G H, Romani N, Hirmand H, Cameron P U, Hoffman L, Gezelter S, Schuler G, Steinman R M. Conjugates of dendritic cells and memory T lymphocytes from skin facilitate productive infection with HIV-1. Cell. 1994;78:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pope M, Elmore D, Ho D, Marx P. Dendritic cell-T cell mixtures, isolated from the skin and mucosae of macaques, support the replication of SIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:819–827. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popov J, McGraw T, Hofmann B, Vowels B, Shum A, Nishanian P, Fahey J L. Acute lymphoid changes and ongoing immune activation in SIV infection. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:391–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudensey L M, Kimata J T, Benveniste R E, Overbaugh J. Progression to AIDS in macaques is associated with changes in the replication, tropism, and cytopathic properties of the simian immunodeficiency virus variant population. Virology. 1995;207:528–542. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudensey L M, Kimata J T, Long E M, Chackerian B, Overbaugh J. Changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein of variants that evolve during the course of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVMne infection affect neutralizing antibody recognition, syncytium formation, and macrophage tropism but not replication, cytopathicity, or CCR-5 coreceptor recognition. J Virol. 1998;72:209–217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.209-217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwiebert R, Fultz P N. Immune activation and viral burden in acute disease induced by simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj14: correlation between in vitro and in vivo events. J Virol. 1994;68:5538–5547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5538-5547.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shearer G M, Clerici M. Early T-helper cell defects in HIV infection. AIDS. 1991;5:245–253. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheppard H W, Ascher M S. The natural history and pathogenesis of HIV infection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:533–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanley S K, Ostrowski M A, Justement J S, Gantt K, Hedayati S, Mannix M, Roche K, Schwartzentruber D J, Fox C H, Fauci A S. Effect of immunization with a common recall antigen on viral expression in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1222–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stern J B, Smith K A. Interleukin-2 induction of T-cell G1 progression and c-myb expression. Science. 1986;233:203–206. doi: 10.1126/science.3523754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevenson M, Stanwick T L, Dempsey M P, Lamonica C A. HIV-1 replication is controlled at the level of T cell activation and proviral integration. EMBO J. 1990;9:1551–1560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tao B, Fultz P N. Molecular and biological analyses of quasispecies during evolution of a virulent simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVsmmPBj14. J Virol. 1995;69:2031–2037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2031-2037.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tersmette M, De Goede R E Y, Al B J M, Winkel I N, Gruters R A, Cuypers H T, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Differential syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus isolates: frequent detection of syncytium-inducing isolates in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J Virol. 1988;62:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2026-2032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tersmette M, Gruters R A, De Wolf F, De Goede R E Y, Lange J M A, Schellekens P T A, Goudsmit J, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Evidence for a role of virulent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) variants in the pathogenesis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: studies on sequential HIV isolates. J Virol. 1989;63:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2118-2125.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Akagawa K, Kimoto H, Suzuki K, Iwasaki M, Yasuda S, Hausser G, Hultgren C, Meyerhans A, Takemori T. Monocyte-derived cultured dendritic cells are susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus infection and transmit virus to resting T cells in the process of nominal antigen presentation. J Virol. 1995;69:4544–4547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4544-4547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu X, McLane M F, Ratner L, O’Brien W, Collman R, Essex M, Lee T-H. Killing of primary CD4+ T cells by non-syncytium-inducing macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10237–10241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zack J A, Arrigo S J, Weitsman S R, Go A S, Haislip A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]