Abstract

Background

Following the development of gender medicine in the past 20 years, more recently in the field of oncology an increasing amount of evidence suggests gender differences in the epidemiology of cancers, as well as in the response and toxicity associated with therapies. In a gender approach, critical issues related to sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations must also be considered.

Materials and methods

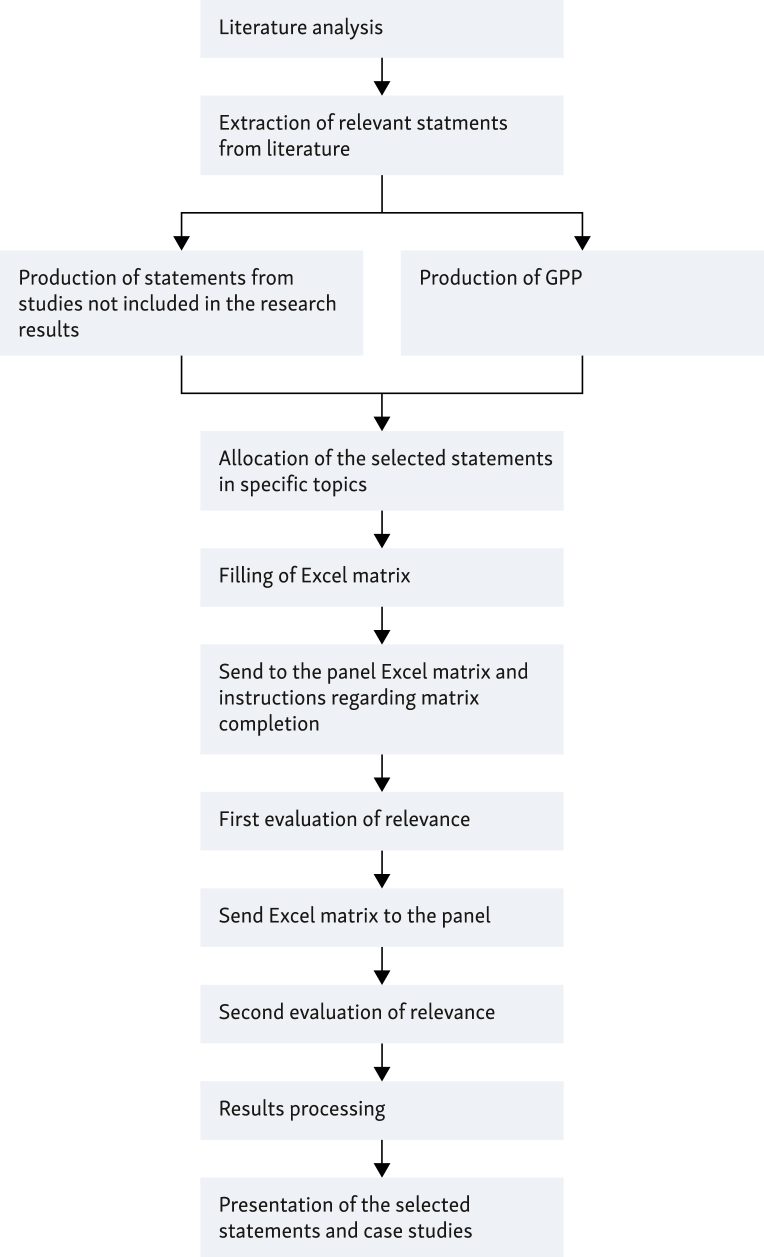

A working group of opinion leaders approved by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM) has been set up with the aim of drafting a shared document on gender oncology. Through the ‘consensus conference’ method of the RAND/University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) variant, the members of the group evaluated statements partly from the scientific literature and partly produced by the experts themselves [good practice points (GPPs)], on the following topics: (i) Healthcare organisation, (ii) Therapy, (iii) Host factors, (iv) Cancer biology, and (v) Communication and social interventions. Finally, in support of each specific topic, they considered it appropriate to present some successful case studies.

Results

A total of 42 articles met the inclusion criteria, from which 50 recommendations were extracted. Panel participants were given the opportunity to propose additional evidence from studies not included in the research results, from which 32 statements were extracted, and to make recommendations not derived from literature such as GPPs, four of which have been developed. After an evaluation of relevance by the panel, it was found that 81 recommendations scored >7, while 3 scored between 4 and 6.9, and 2 scored below 4.

Conclusions

This consensus and the document compiled thereafter represent an attempt to evaluate the available scientific evidence on the theme of gender oncology and to suggest standard criteria both for scientific research and for the care of patients in clinical practice that should take gender into account.

Key words: gender oncology, cancer, epidemiology, outcome and toxicity, anticancer therapies

Highlights

-

•

Data suggest gender differences in cancer epidemiology, as well as in outcome and safety related to anticancer therapies.

-

•

In research it is essential to increase the number of women in clinical trials and disaggregate data by sex and gender.

-

•

Individual, institutional, and systemic adjustments are needed to increase the safety of oncology settings for SGM patients.

Introduction

In medicine, pharmaceutical clinical trials, and scientific research, the study of gender differences is a recent development that represents a milestone of great importance in the progress of science.

As defined by World Health Organisation (WHO), gender medicine is the study of the influence of biological (defined by sex) and socioeconomic and cultural (defined by gender) differences on each person’s health and disease status.

Differences between the two sexes are observed in the pathogenesis, history, and clinical manifestations of diseases and in the response and toxicity related to treatments. Furthermore, it has been shown that at the cellular level several variables (genetic, epigenetic, hormonal, and environmental) contribute to the differences between male and female cells.1

Gender differences between the two sexes are also cultural and social, with women still being disadvantaged compared with men (owing to, in some cases, physical and psychological violence, greater unemployment, or economic difficulties). A female patient often faces the absence of a caretaker, undertaking this role herself for her family members. Within families, mothers and wives are often the first line of defence between disease and treatment, because they are more attentive to the health of their loved ones even at the expense of their own.1

Gender medicine is a necessary interdisciplinary dimension of medicine that aims to study the influence of sex and gender on human physiology, pathophysiology, and pathology. Medical practice now codified by evidence-based medicine and guidelines is based on evidence obtained from large trials conducted almost exclusively on one sex, predominantly male. Therefore it is not only about increasing knowledge of diseases related to the reproductive functions of men or women but also about studying all the diseases that afflict men and women: cardiovascular diseases, tumours, metabolic diseases, osteoarticular, neurological, infectious, and autoimmune diseases, as well as those arising as a result of exposure to environmental pollutants and/or toxic agents. From this perspective, parameters such as age, ethnicity, cultural and religious background, sexual orientation, and social and economic conditions should be considered in the evaluation and management of diseases in addition to the biological sex of the patient. Considering gender, critical issues related to the health status of transgender and intersex people who have particular special needs must also be considered.

Only by proceeding in this direction and strengthening the concepts of ‘patient centrality’ and ‘personalisation of therapies’ will it be possible to guarantee the best care and to ensure the full appropriateness of interventions for each person, while providing financial savings for the National Health System (NHS).

The seminar sponsored by the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), entitled ‘Gender Medicine Meets Oncology’, held in Lausanne in 2018, represented the starting point for underlining the impact of gender in oncology. Cancer shows differences between men and women in epidemiology, pathogenesis, response to treatments, and treatment-related adverse effects.

Men and women have a different predisposition to the occurrence of specific neoplasms, with a higher incidence and mortality of cancer in men than in women both globally and in relation to our country. This is due to the habits and biological factors as well as gender issues. At least historically, men have been exposed more than women to environmental risk factors, such as smoking or ultraviolet radiation, and to environmental pollutants for professional reasons. Besides, regarding nutrition and consumption of alcohol, men are less virtuous than women. In addition, women adhere to screening programs more than men, thanks in part to prevention and awareness campaigns aimed at the female audience.1

It has been shown that differences in epidemiology between the two sexes may also depend on biological factors. Women have two X chromosomes while men only have one and this may be a factor in cancer prevention. When mutated, specific genes on the X chromosome [escape from X-inactivation tumour suppressor (EXITS)] contribute to the development of cancer. Women who possess two copies of these genes would be more protected against the chance of mutations occurring than men who possess only one. Even if one of the two X chromosomes was affected by the mechanism of gene silencing (also known as X chromosome inactivation), the protective effect would still be present.2

A difference in response to therapy between the two sexes has also been detected. Scientific evidence mainly concerns immunotherapy, with women experiencing a lower survival benefit than men when treated with immunotherapy as monotherapy and a greater survival benefit when treated with the combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy.3 It is hypothesised that differences in the immune system between women and men may have an important function in the natural course of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as cancer, and in their response to treatments, also based on how sex and gender can affect the intensity of immune response in general. Differences in the molecular mechanisms that drive the antitumour immune response in the two sexes are a result of complex interactions between genes, hormones, environment, and the composition of the microbiome.3,4

Gender is rarely considered in the risk assessment of toxicity related to treatments, yet data are increasingly consistent: regarding all types of treatment, female sex is associated with an increased risk of 34% of adverse events (AEs) than men and, considering data broken down by therapy type, there is also an increased risk of 49% among those who received immunotherapy. Even within individual categories of AEs there are differences between males and females: women experience an increased risk of severe symptomatic AEs in all treatments, especially immunotherapy, while women treated with chemotherapy or immunotherapy experience an increased risk of severe haematological AEs; however, no statistically significant gender differences in nonhaematological AE risk were found.5 These differences in AEs could be explained in several ways: differences in reported AEs, differences in total dose received, differences in adherence to therapy, and differences in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, emphasising the importance of gender pharmacology and the problem of the underrepresentation of women in pharmaceutical clinical trials. As a result, very few pharmaceutical products make gender claims on the data sheet.6

Therefore a working group of expert health care professionals has been set up by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM) to carry out an evaluation of the available scientific evidence on the theme of Gender Oncology. This has been done through the ‘consensus conference’ method to draw up recommendations useful to health care professionals.

Materials and methods

A modified version of Delphi methodology by RAND/University of California Los Angeles (UCLA)7 developed by the working group has been used as a consensus tool among participants. The original Delphi tool is a quick and structured method for obtaining opinions on a specific topic by a group of experts constituting the evaluation panel.

The panel members assessed a series of statements derived partly from scientific literature and partly formulated by the experts themselves. This process involved multiple rounds, with each round defined based on feedback from the previous evaluation.

The participants made a judgment of relevance on a scale from 1 to 9. At the end of this phase a ranking was produced, and a second meeting was scheduled to discuss the uncertain claims classified with a median score in the range of 4-6.

Participants and recruitment

A group of opinion leaders from academic and institutional backgrounds related to the discipline of gender medicine and oncology was involved with the aim of identifying the most effective interventions on the topic of gender oncology and proposing specific strategies for their application in the management of patients with cancer.

A methodological support group was expected to collect information and process the data.

Literature research

The search strategy involved seeking primary and secondary studies to describe the most robust scientific evidence in the field of gender oncology.

The bibliographical research of scientific documents was carried out by searching the main biomedical database (PubMed/Medline) from 2 January 2023 to 14 January 2023 using the following queries (keywords/MeSH terms): (gender [MeSH terms]) AND (oncology [MeSH terms]), (gender [All Fields]) AND (immunotherapy [MeSH terms]), (gender [All Fields]) AND (radiotherapy [MeSH terms]), (gender [All Fields]) AND (5-fluorouracil [MeSH terms]), (gender [All Fields]) AND (targeted therapy [MeSH terms]).

Studies published from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2022 were reviewed.

Criteria for selection/inclusion of documents

Eligibility

All scientific documents concerning the production of good practices in the field of gender oncology have been considered eligible for inclusion.

Selection of eligible documents

The following selection/inclusion criteria were used for the selection of studies:

-

•

Studies in English (or Italian)

-

•

Studies on healthy adults and adults with cancer

-

•

Search for evidence from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2022

-

•

Relevance of the study for the reference context.

All the following evidence was excluded:

-

•

Not in English (or not in Italian)

-

•

Published before 1 January 2012 and after 31 December 2022

-

•

Referred to the paediatric population

-

•

Referred to patients with non-oncological or haematological diseases

-

•

Related to studies not relevant to the topic of gender oncology.

Evidence report

Through the creation of an evidence report for each selected study, the following information was reported:

-

•

Reference and country

-

•

Introduction

-

•

Materials and methods

-

•

Results and conclusions

-

•

Quality assessment of the study.

Two scales were used to assess the quality of the studies. Qualitative studies were evaluated using The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ)8 and clinical studies using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria.9

Selection of statements

Two different authors independently carried out a detailed reading of the papers. They both extracted the best evidence, a series of statements or opinions, from the documents found. Following a comparison of the selected items, a list of statements was structured in an Excel format matrix linked to a minimum set of information, such as bibliographic references (authors of the paper, title, journal, year of publication, and country where the study was conducted). The text of the selected statements was translated into Italian to facilitate their comprehension among the panel. Furthermore, the following topics were identified:

-

•

Healthcare organisation

-

•

Therapy

-

•

Host factors

-

•

Cancer biology and

-

•

Communication and social interventions.

Finally, the panel received the Excel matrix via e-mail.

Relevance evaluation of the statements selected by the literature, additional recommendations, and case studies

The members of the panel evaluated the relevance of each statement.

A modified version of the Delphi methodology has been used for the evaluation: specifically, the panel members evaluated the relevance of good practices selected as follows:

-

1.

First evaluation of relevance: individual assessment by each group member for each statement proposed within specific subgroups. The judgement was expressed on a scale from 1 to 9, where 1 = certainly irrelevant, 9 = certainly relevant, and 5 = uncertain.

-

2.

Second evaluation of relevance (with the possibility of group comparison): evaluation of intermediate judgements (band 4-6.9). Participants displayed a report showing the results of the first evaluation for each recommendation. The discussion then focused on any potential areas of disagreement.

-

3.

Data analysis: the scenarios were judged in agreement in which the remaining judgments fell into any of the three regions of the score (1-3, 4-6, and 7-9), corresponding to the three levels of evaluation.

In addition to the compilation of the matrix according to the aforesaid criteria, participants were asked to provide additional recommendations to be referred to as good practice points (GPPs), attributed to five predefined topics (discussed earlier), and then submit them to the panel. The recommendations were included in the set of statements to be voted on following the first evaluation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The modified version of Delphi methodology by RAND/University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) developed by the working group. GPP, good practice point.

Finally, in support of each specific topic addressed, the group deemed it appropriate to present some successful case studies. Based on the average evaluation of the various recommendations, these were then included in the final document.

Results

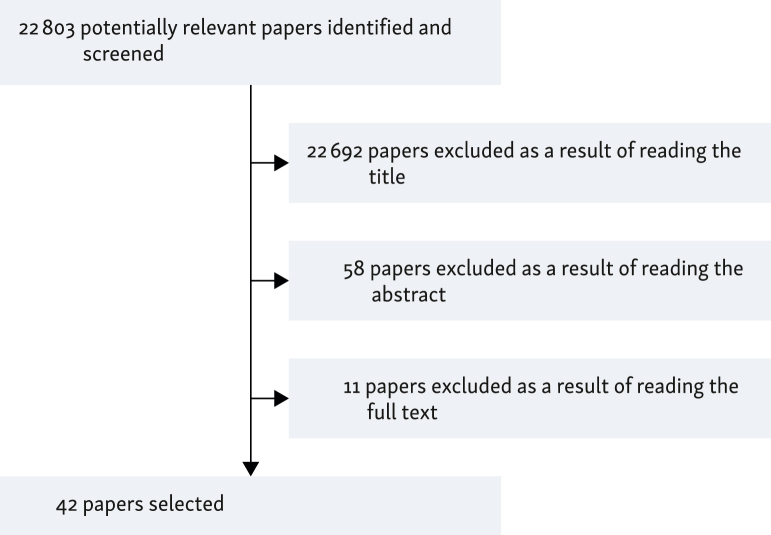

Following the reading and analysis of the evidence found in the literature, 42 articles met the criteria for inclusion in the period considered (2012-2022; Figure 2) from which 50 statements were extracted related to the field of gender oncology.

Figure 2.

Algorithm of selected papers.

Panel participants were given the opportunity to propose additional evidence from studies not included in the research results, from which 32 statements were extracted, and to make recommendations not derived from the literature such as GPPs, four of which have been developed.

Following an evaluation of relevance by the panel of experts, it was found that 81 recommendations scored >7, 3 between 4 and 6.9, and 2 below 4 (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5).

Table 1.

Recommendations on the theme ‘Healthcare organisation’ with relevance assessment

| Recommendations extracted from the selected studies on the theme ‘Healthcare organisation’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statementa | Assessment |

| Health care providers should engage in shared medical decision making, particularly in settings where patient priorities differ from guidelines or when discussing gender-related treatments (e.g. hormones or surgery) in the context of cancer treatment.10 | 9 |

| Patient-reported symptomatic AEs should be included in routine monitoring to shed further light on potential sex-related differences.5 | 9 |

| There should be pooling among clinical trial databases to enhance statistical power to identify trends in AEs by sex.5 | 9 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure clinical trial criteria do not exclude participants based on gender, hormones, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status unless clinically indicated.10 | 9 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure SGM cultural humility training is required for all staff and clinicians.10 | 8.5 |

| Curricula should be required to train oncologists in SGM health care needs and affirmative communication skills to facilitate patient-centred care for SGM individuals with cancer.11 | 8 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure clear and accessible grievance policies for patients who experience discrimination.10 | 8 |

| A comprehensive clinical evaluation of patients, encompassing the functional assessment and the comorbidity profile as well as chronological age, together with the potential predicted risk of treatment-related toxicity, should always be carried out before the start of a first-line treatment to guide the therapeutic choice and to maximise the risk–benefit profile.12 | 8 |

| To promote more equitable research and care for SGM populations, SOGI data should be included in cancer registries and clinical trials. Funding opportunities to train the next generation of researchers should also be increased to raise awareness of health issues among SGM people.13 | 8 |

| More education and research are required to bridge knowledge gaps among radiation therapists about LGBTQ2SPIA+ patients with cancer to provide inclusive patient care.14 | 8 |

| The underlying problems of cancer screening in the SGM populations should be understood to define future clinical and institutional approaches so as to improve health care.15 | 8 |

| Population-based studies or meta-analyses should be conducted to encourage discussion about the inclusion of sex and gender characteristics in the decision making for the personalised treatment of patients with brain metastases.16 | 8 |

| Patients should be provided with different avenues for disclosing SOGI information such as in hospital forms (both written and online) and verbal questioning from HCPs as a routine part of sociodemographic and history-taking.17 | 7 |

| During hospital admissions, assessing patient comfort in sharing rooms with someone of a different SO or GI may be helpful in determining hospital policies and communicating the same to patients upon admission.17 | 7 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure the availability of all-gender restrooms.10 | 7 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure intake forms have a language that does not make presumptions about anatomy based on gender (e.g. ‘for women only: when was your last period?’).10 | 7 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure intake forms are inclusive of SGM people by including answer options inclusive of SGM identities (e.g. questions about gender include nonbinary, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, and/or other options).10 | 7 |

| Oncology institutions should engage in comprehensive data collection, including querying sexual orientation, gender identity (including whether someone is transgender), and anatomy and consider checking hormone levels.10 | 7 |

| Oncology institutions should ensure gowns and other clothing items provided are gender-neutral and/or that multiple options exist from which to choose.10 | 5 |

| Recommendations promoted by the panel of experts on the theme ‘Health care organisation’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| It is important to promote preclinical, clinical, and translational research in oncology that takes into account a gender perspective. | 9 |

| More training of health care professionals in the field of gender medicine and gender oncology is needed. | 9 |

| In preclinical and clinical research in oncology it is essential to disaggregate data by sex and gender, in accordance with the guidelines for the application of gender medicine in research, drawn up by the observatories for monitoring the application of gender medicine in the NHS and this information should also be available on their website.18 | 9 |

| It is essential in the predisposition of integrated care pathways that care dedicated to oncological pathologies takes into account the biological differences between men and women in various types of neoplasms and pays attention to the social and economic factors that affect the state of health, to define management paths in the perspective of gender that can be so facilitated and customised for the patients.18 | 9 |

| Given the gender differences observed in oncology, sex should be an important stratification factor to be included in all randomised clinical trials to better understand the biological differences between men and women to improve biological therapies.19 | 9 |

| Evidence of gender differences in lung cancer may justify a change in screening programmes: different selection criteria for screening programmes for lung cancer by gender should be evaluated, to guarantee equal opportunities for participation, allowing both genders to benefit.20 | 8 |

| A review of the literature shows evidence of gender inequality in patients with lung cancer in access to health care services and treatments in developed countries. However, evidence is not available in developing countries, so further studies are needed to understand gender inequalities in these contexts and design interventions to improve the survival of patients with lung cancer.21 | 8 |

| More training and research are needed to fill gaps in health care professionals’ knowledge (oncologists, other specialists, nurses, etc.) about LGBTQ2SPIA+ patients with cancer to provide inclusive care to these patients. | 8 |

| Clinical trials in oncology should report extensively the outcomes of safety, quality of life, efficacy, and activity by gender, as ancillary publications or as additional material. | 8 |

AE, adverse event; GI, gender identity; GPPs, good practice points; HCP, health care professional; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LGBTQ2SPIA+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, two-spirit, pansexual, intersex, asexual, plus; NHS, National Health System; SGM, sexual and gender minority; SO, sexual orientation; SOGI, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Statements without a bibliographic reference are GPPs.

Table 2.

Recommendations on the theme ‘Therapy’ with relevance assessment

| Recommendations from the selected studies on the topic ‘Therapy’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| The increased severity of both symptomatic and haematological adverse events in women treated with different therapeutic modalities confirms that there is a gender difference. This may be due to differences in the mode of reporting adverse events, pharmacogenomics, total dose received, and/or adherence to therapy. In particular, large gender differences have been observed in patients treated with immunotherapy, indicating that studying adverse events due to such therapies is a priority.5 | 9 |

| 5-FU is a clear example of the importance of gender pharmacology. Further prospective studies to determine sex-specific differences in clinical trials of colorectal cancer treatment using 5-FU as a therapeutic agent should be conducted to support appropriate 5-FU based-chemotherapy based on sex as a crucial factor and to enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and minimise adverse drug reactions to anticancer drugs.12,22, 23, 24, 25, 26 | 9 |

| Future research should ensure greater inclusion of women in studies and focus on improving the efficacy of immunotherapies in women, perhaps by exploring different immunotherapy approaches in men and women.27 | 9 |

| As women are underrepresented in chemotherapy trials cited by national guidelines, especially in head and neck cancers, and are therefore less likely than men to receive definitive chemoradiation therapy compared with definitive radiotherapy, further investigation as well as re-evaluation of eligibility criteria and enrolment strategies should be carried out to improve relevance of clinical trials in women with these cancers.28 | 9 |

| Particularly in the field of immunotherapy, clinical trials should aim to explicate the role of factors such as race, histologic type tumour stage, and other factors to explicate the effect of gender on cancer treatment outcomes.29,30 | 8 |

| As gender, age, and clinicopathological parameters have been correlated with chemoradiotherapy-associated acute toxicity and survival in rectal cancer, pretreatment baseline parameters that allow the identification of subgroups of patients at higher risk of severe acute organ toxicity should be defined to improve the clinical management of these patients and apply optimised standards of supportive care.31 | 8 |

| High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of urinary levels of uracil and dihydrouracil from patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment should be further investigated because it appears to be promising for clinical use to predict and prevent the occurrence of treatment-related toxicities.32 | 7 |

| Clinical trials that aim to investigate the relationship between radiotherapy and gender in terms of outcomes and adverse effects should provide specific information about treatment modality that might affect the analysis.33 | 7 |

| Accrual and design of immunotherapy studies could be conducted separately for men and women, with appropriate sample size planning for both.4,29 | 7 |

| Sex appears to be an independent prognostic factor in Chinese patients with ESCC undergoing definitive radiotherapy, with better survival in women than men. Sex would affect the radiosensitivity of patients with ESCC exposed to radiotherapy and the relationship between sex and radiosensitivity in ESCC should be investigated, for example, by focusing future efforts on the study of the relationship between androgen levels and the prognosis of patients with ESCC exposed to radiotherapy. From this starting point it would be useful to consider future clinical research comparing combined chemoradiotherapy and anti-androgen treatment with chemoradiotherapy alone in the ESCC.34 | 3 |

| Recommendations promoted by the panel of experts on the theme ‘Therapy’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| Women with metastatic melanoma and NSCLC may have a higher risk of immuno-related adverse events than men when treated with anti-PD-1 therapy.35 | 9 |

| The increased severity of both symptomatic and haematological adverse events in women treated with different therapeutic modalities confirms that there is a gender difference. This may be due to differences in the mode of reporting adverse events, pharmacogenomics, total dose received, and/or adherence to therapy. In particular, large gender differences have been observed in patients treated with immunotherapy, indicating that studying adverse events due to such therapies is a priority.5 | 9 |

| To date there is increasing scientific evidence of gender/sex differences in neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, both in incidence (higher in men) and in clinical behaviour (worse prognosis in males and a greater risk of recurrence after curative surgery). However, there is a lack of data on possible differences in response to treatments, which is therefore suggested to be investigated through gender-oriented clinical studies, including an equal representation of the sexes and a gender-disaggregated statistical analysis.36 | 9 |

| Sex and gender have a role in inflammation, immune response to cancer, and carcinogenesis, so understanding these aspects is necessary to increase responses and reduce adverse events from immunotherapy. This gender perspective needs to be taken into account by clinicians and researchers to achieve personalised therapeutic strategies.37 | 9 |

| Endocrine toxicities, frequent in patients treated with immunotherapy, may present gender differences in incidence and type: the female sex predicts the risk of developing thyroid toxicity, while males are more susceptible to pituitary toxicity. However, in the therapeutic management of adverse events, no sex and gender differences are known, so they should be investigated.38,39 | 9 |

| Although women with melanoma generally have a better survival rate than men, combined immunotherapy appears to be disadvantageous for women compared with men; in fact, higher mortality rates have been reported. Through future clinical trials it is essential to investigate whether mortality depends on lower therapeutic efficacy or increased toxicity in women.40 | 8 |

| Women with NSCLC treated surgically typically have a better long-term outcome than men, without significant differences in the severity of the disease. Better survival and lower frequency of post-operative complications among women should be taken into account in the therapeutic decision making and surgical treatment proposal, especially in uncertain cases.41 | 8 |

| Immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC is more effective in males than in females. Gender should be considered in clinical practice in the choice of immunotherapy.42 | 8 |

| Women with melanoma benefit more from adjuvant immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) than men, for greater activation of the type 1 immune response both in the circulatory and in the tumour microenvironment. In an adjuvant setting, this different response may suggest a therapeutic choice that is based on gender and that should be evaluated through dedicated clinical trials.43 | 7 |

5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; ESCC, squamous cell oesophageal carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1.

Table 3.

Recommendations on the theme ‘Host factors’ with relevance assessment

| Recommendations from selected studies on ‘Host factors’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| Smoking history should be equally reported in both male and female patients, because smoking status is an important potential confounder especially in lung cancer clinical trials.44 | 9 |

| The gender-specific sensitivity of rectal cancer screening tests, gender differences in referrals, and clinical reasons for not prescribing preoperative radiotherapy in women should be further examined. If these gender differences are not clinically justifiable, their elimination might enhance survival.45 | 8 |

| Further investigation of sex hormones and their association with the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy should be the focus of larger clinical trials to evaluate these parameters as possible prognostic markers.46 | 8 |

| Subgroup analyses are important and should be conducted to provide evidence of sex-linked pharmacogenomic markers that should be further studied in larger cohorts of patients.47 | 7 |

| Studies in a much larger sample of patients should be conducted to demonstrate more definitive trends in the clinical behaviour of oesophageal carcinoma between sexes.48 | 7 |

| Further studies should be conducted to investigate the sex-dependent anti-tumour immune response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.49 | 7 |

| The tumour microenvironment is closely associated with the clinical outcome of patients with ccRCC. Gender is one of the factors influencing the TII score. A high TII score seems to be more associated with the female sex.50 | 7 |

| Recommendations promoted by the panel of experts on the theme ‘Host factors’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| The number of lung carcinomas in nonsmoking women has increased in recent decades. In these cases, the aetiology should be clarified and the carcinogenicity of genetic factors, environmental exposures, and lifestyle should be investigated in a gender-specific manner, to change the study and management of lung cancer and to plan interventions to reduce the incidence of lung cancer in women.51 | 9 |

| Genetic factors, some of which are sex related, and a number of modifiable environmental factors, including lifestyle, play an important role in the aetiology of colorectal cancer. Excessive body weight, poor nutrition, and physical inactivity are among the major risk factors for the development of this pathology, with a different impact in women and men. In primary prevention, protective diets and specific physical activity regimes for women and men should be considered.52 | 9 |

| In women, the greater average length of the total and transverse colon, the more frequent occurrence of right colon cancer of flat type, and the narrower colon diameter than that of men can cause technical limitations of endoscopic examinations. Therefore a customisation of endoscopic devices for women should be carried out.53,54 | 9 |

| In recent years, significant increases have been observed in the percentage of cases of NSCLC in males and patients >55 years of age. NSCLC pathogenesis research and prevention are urgently needed in these categories of patients.55 | 8,5 |

| Young women with surgically treated NSCLC may have less comorbidity and have a lower percentage of postoperative complications. Despite the more advanced stage of the disease, survival is better than in older women. Therefore earlier and more effective diagnosis is needed in younger women who often have an advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.56 | 8 |

| Gender behavioural differences in adherence to melanoma screening programmes and ultraviolet radiation skin protection have been demonstrated. These differences are also confirmed in patients who have already been diagnosed with melanoma: a greater percentage of women adopt behaviours that prevent the development of subsequent melanomas. More education and close follow-up examinations are therefore suggested, especially in male patients.57 | 8 |

| After a diagnosis of melanoma women appear to have more favourable outcomes than men, as evidenced by longer free-time relapses and lower mortality rates. The skin of men and women differ in response to oestrogens and androgens. The first accelerate scar repair, increases the thickness of the epidermis, and exerts a protective action against so-called photoaging. Androgens, by contrast, can promote melanoma tumorigenesis. In addition, women have higher levels of immunoglobulins G (IgG) and M (IgM) antibodies and also so-called CD3+ T lymphocytes, a condition that makes them less vulnerable to the development of skin tumours. Men, by contrast, seem more susceptible to immunosuppression induced by ultraviolet radiation exposure. Gender is therefore an important prognostic factor for melanoma, for which specific primary prevention campaigns for women and men should be conducted and further studies should be carried out to include gender in the official melanoma staging system.58 | 8 |

| Globally, the total incidence of skin melanoma is higher in men than in women, as well as differences in the anatomical localisation of melanoma. Studies recruiting a balanced number of men and women are needed to better understand gender differences and ensure gender-fair health care.59 | 8 |

| Women with lung adenocarcinoma may have significantly better survival than men regardless of smoking habits. Other prognostic factors besides those known, such as access to treatments and therapeutic choices, should also be investigated.60 | 8 |

| In addition to the scientific evidence regarding gender differences in skin melanoma, preliminary data suggest a different prognosis and a different clinical presentation between men and women also in uveal melanoma. However, they should be investigated through larger case series.61 | 8 |

| In colorectal cancer hormonal factors seem to be responsible, at least in part, for the rate of incidence standardised by age which is higher in men than in women. Female sex hormones, in particular oestrogens, are protective factors, as evidenced by the increased risk found in postmenopausal women and the reduction of risk in postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy. The possible protective role of oestrogen therapy in postmenopausal women with familiarity for colorectal cancer should be further investigated.62 | 7 |

ccRCC, clear renal cell carcinoma; TII, tumour immune infiltration; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

Table 4.

Recommendations on the theme ‘Cancer biology’ with relevance assessment

| Recommendations extracted from the selected studies on the theme ‘Cancer biology’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| Further studies should be conducted to highlight the clinical relevance of immunohistochemistry and confirm sex-specific differences in platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRα) expression for a molecular-guided therapeutic approach in the management of advanced malignant mesothelioma.63 | 8 |

| Further studies should be conducted in the field of advanced pancreatic carcinoma to confirm the predictive value of female sex to therapy with FOLFORINOX and its correlation with serum carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA19.9) levels and the expression of tumour protein p53 (p53) and Ki-67.64 | 8 |

| Further studies should be conducted to confirm that Na+ voltage-dependent channels may be a potential therapeutic target and a useful predictive biomarker before 5-fluorouracil infusion, as a gender association between some polymorphisms of sodium channels and time to recurrence has been demonstrated.65 | 8 |

| Further studies should be conducted to confirm the prognostic value of pre-treatment expression of Ki-67, KU70, and B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) in rectal cancer for pathological tumour response and clinical tumour response before preoperative radiotherapy and to confirm the potential difference between these parameters according to the sex of the patient.66 | 8 |

| In clinical studies several tumour mutational burden cut-off points in men and women should be considered to improve their predictive value in both sexes.3 | 8 |

| Further studies should be conducted to obtain more information on the molecular differences related to sex-specific carcinogenesis in bladder cancer and possible therapeutic considerations.67 | 7 |

| Recommendations promoted by the panel of experts on the theme ‘Cancer biology’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| In women the preferential localisation of colorectal cancer in the right tract of the intestine and the greater distance from the terminal part could make screening for faecal occult blood less effective with a higher probability of false negatives. For this reason and the appearance of cancer at an older age, the extent of screening in women should be assessed.53,54 | 9 |

| The preferential localisation of colorectal cancer to the right tract in women is indicative of a greater aggressiveness than shown in men owing to the different molecular and pathological characteristics that are associated with this neoplasm depending on the location of the tumour: microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation often observed in right colon cancers and chromosomal instability and p53 mutations more often in left-side tumours. Different therapeutic approaches in women and men with colorectal cancer should be investigated.54,68,69 | 8 |

| With new techniques of analysis belonging to the discipline of metabolomics, differences have been demonstrated in the molecular processes of male and female tumours and, therefore, in cancer growth strategies: women with colon cancer have higher levels of fatty acids, responsible for energy production by oxidation, while in male patients there is an increase in the levels of other metabolites such as lactate that produce energy through a different pathway, less erosive than oxidation. Different therapeutic approaches to stop colorectal cancer growth in women and men should be investigated.70 | 8 |

| A gender difference in the mutational burden of skin melanomas has been demonstrated. For this reason, sexual dimorphism in gene expression is also an aspect to be considered for a holistic understanding of melanoma gender differences.71,72 | 8 |

| Rates of melanoma incidence are higher in women before middle age and in older men. These observations are due to gender-specific differences in the incidence of cancer at particular anatomical sites: higher rates of lower limbs melanoma in women at an early age and higher rates of head and neck cancer in older men. Further studies should be carried out to confirm a gender-specific relationship between age and onset of melanoma taking into account not only extended anatomical sites but also finer subdivisions of anatomical sites.73 | 8 |

| Thyroid cancer is more common in women, but in males more aggressive histological subtypes and worse prognosis are detected. In addition to the role of oestrogens that has been investigated to explain such gender differences in cancer incidence and progression, preclinical and clinical research studies are needed to effectively assess the impact of sex and gender on the molecular biology of cancer. The use of cutting-edge molecular biology techniques will allow to promote the design of sex-specific therapies, which are potentially more effective in advanced thyroid cancer.74, 75, 76 | 8 |

| An increased survival among females with lung adenocarcinoma with wild-type P53 genes and high levels of immune infiltration and activation of the interferon gamma (INF-γ) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) pathway is shown. Therefore for a complete and advanced approach to therapy it is necessary to consider the sex of the patient and the mutation state of the tumour protein p53 (TP53) gene.77 | 7 |

Table 5.

Recommendations on the theme ‘Communication and social interventions’ with relevance assessment

| Recommendations extracted from the selected studies on the theme ‘Communication and social interventions’ with relevance assessment. | |

|---|---|

| Statement | Assessment |

| In relation to radiotherapy treatments for pelvic tumours, further research should be conducted to determine the best way to provide inclusive information to transgender and nonbinary patients, such as brochures containing correct language and information.78 | 8 |

| As there are little data available on gender differences about issues such as health-related quality of life of patients with mainly head and neck cancers, future studies should take into account gender differences between patients.79 | 8 |

| Health care professionals should provide information on the possible consequences of cancer-related alopecia for the identity and social relationships in both sexes. Highlighting gender differences in hair loss related to cancer and providing specific support to men’s needs would be particularly helpful, allowing for greater gender equality in clinical practice.80 | 8 |

| Health care professionals should avoid gender language when referring to specific cancers (e.g. ‘women’s cancers’).10 | 7 |

| Healthcare professionals should avoid gender language when asking about partners.10 | 7 |

| Quality of life predictors differ by sex. Depression is a predictor of QoL in both male and female sexes, while other QoL predictors are sex specific. Investigating them can be instructive in designing gender-specific interventions to improve QoL.81 | 7 |

| After collecting SOGI information, health care professionals should use the name and pronouns provided by each patient consistently, both in person and in the documentation.10 | 5 |

| An appropriate support to help healed people enter the working world should consist of a gender-based approach to rehabilitation that strengthens men’s propensity to productivity and activity, to improve the participation of healed male patients and the effectiveness of reintegration efforts.82 | 5 |

| To achieve a more gender-sensitive approach and not put men at a disadvantage, a two-step approach to EoL interviews should be used: (1) an ‘early’ interview providing basic information on the need to talk about EoL or ACP in general; (2) subsequent calls to discuss specific issues on the EoL or to proceed with the ACP using open, nonconflictual, and nonprovocative questions, or using starting points in medical care or organisational ‘facts’, especially for men.83 | 3 |

ACP, advance care planning; EoL, end of life; QoL, quality of life; SOGI, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Discussion and conclusions

Over the past 10 years scientific literature in the field of oncology has been enriched by an increasing amount of evidence about the innovative field of gender differences, in particular in the host-specific factors and biological processes underlying oncological diseases and, consequently, in the epidemiology of tumours, as well as response and toxicity related to therapies, underlying the need for health care organisation and communication interventions to better take charge of the patient and his/her pathology. In a gender approach, critical issues related to the health status of sexual and gender minority patients, which today represent a significant percentage of the population, and which has sui generis characteristics with regard to cancer, must also be considered.

The elaboration of useful and reproducible recommendations aims at a systemisation of research that is reflected in the application in clinical practice of a personalised medicine based on gender.

Primary prevention interventions, including appropriate health education projects; adequate screening programmes in secondary prevention; the predisposition of integrated care pathways dedicated to oncological diseases that take into account gender differences; the promotion of preclinical, clinical, and translational research that does not neglect gender; the design of gender-specific adaptations in oncological treatments that ensure better tolerance of therapies; the attention to communication; and relevant social issues in oncology, are the main purposes of this work.

To our knowledge, this represents the first document to be produced through the ‘consensus conference’ method, providing recommendations about gender oncology. These recommendations, shared and put forward by experts in the medical area, might represent a common basis and highlight good standards that might be used in clinical trials and daily clinical practice to improve the quality of care for oncological patients. Obviously, this method might be applicable to all areas of medicine, replicating our methodology and involving specific experts.

Nevertheless, this work presents some limitations. First, the panel selection was arbitrary, despite it being carried out with the intention of choosing the members specifically based on their expertise in the field as well as considering how each members’ knowledge would complement that of the other panel members. In addition, the subjectivity of individuals who handled the selection of papers from literature and the identification of the statements has unavoidably impacted the work.

In conclusion, personalised medicine must emerge as the future paradigm, incorporating sex-specific adjustments. This approach ensures that scientific research considers gender differences and translates this knowledge into clinical practice within health care organisations. Communication interventions dedicated to oncological diseases should also account for biological disparities among patients, while paying attention to cultural and social factors. A gender view can also generate a reduction in costs because personalised care pathways guarantee a better use of resources and savings, which are generated by an adherence to therapies that avoid prescription errors, together with greater safety in treatments and therapeutic appropriateness. Selecting patients in advance who can respond to treatment could avoid unnecessary costs, with the resources saved being allocated to the treatment of other important diseases as well as improving the quality of care as already mentioned.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

RB grants or contracts from any entity: Roche, Pfizer, AZ, to institution; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Gilead, Seagen, GSK, Eisai, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Boeringher. TV reports payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Helaglobe/Recordati, Astrazeneca; support for attending meetings and/or travel: Sanofi-Regeneron; participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: Takeda; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid: Regional Referent for GISEG (Italian Group Health and Gender). FP reports institutional research grants from: BMS, Incyte, Agenus, Amgen, Lilly and AstraZeneca; personal fees from: BMS, MSD, Amgen, Merck-Serono, Pierre-Fabre, Servier, Bayer, Takeda, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Rottapharm, Ipsen, AstraZeneca, GSK, Daiichi-Sankyo, Seagen. SC is the President of AIOM Foundation (Italian Association of Medical Oncology). The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Istituto Superiore di Sanità. https://www.iss.it/

- 2.Dunford A., Weinstock D., Savova V., et al. Tumor-suppressor genes that escape from X-inactivation contribute to cancer sex bias. Nat Genet. 2017;49:10–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conforti F., Pala L., Pagan E., et al. Sex-based dimorphism of anticancer immune response and molecular mechanisms of immune evasion. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(15):4311–4324. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capone I., Marchetti P., Ascierto P.A., Malorni W., Gabriele L. Sexual dimorphism of immune responses: a new perspective in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:552. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unger J.M., Vaidya R., Albain K.S., et al. Sex differences in risk of severe adverse events in patients receiving immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or chemotherapy in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(13):1474–1486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Università di Padova. Bo Live UniPD https://ilbolive.unipd.it/

- 7.Fitch K., Bernstein F.J., Aguilar M.D., et al. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2000. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh S., Jones M., Bressington D., et al. Adherence to COREQ Reporting Guidelines for Qualitative Research: a scientometric study in nursing social science. Int J Qual Meth. 2020;19 doi: 10.1177/1609406920982145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbour R., Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH2 1JQ. BMJ. 2001;323:334–336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpert A.B., Scout N.F.N., Schabath M.B., Adams S., Obedin-Maliver J., Safer J.D. Gender- and sexual orientation-based inequities: promoting inclusion, visibility, and data accuracy in oncology. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022;42:1–17. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_350175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutter M.E., Simmons V.N., Sutton S.K., et al. Oncologists’ experiences caring for LGBTQ patients with cancer: qualitative analysis of items on a national survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Apr;104(4):871–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raimondi A., Fucà G., Leone A.G., et al. Impact of age and gender on the efficacy and safety of upfront therapy with panitumumab plus FOLFOX followed by panitumumab-based maintenance: a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the Valentino study. ESMO Open. 2021;6(5) doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent E.E., Wheldon C.W., Smith A.W., Srinivasan S., Geiger A.M. Care delivery, patient experiences, and health outcomes among sexual and gender minority patients with cancer and survivors: a scoping review. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4371–4379. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan S., Ly S., Mackie J., Wu S., Ayume A. A survey of Canadian radiation therapists’ perspectives on caring for LGBTQ2SPIA+ cancer patients. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2021;52(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardo J., Ko K., Shimada A., et al. Perceptions of and barriers to cancer screening by the sexual and gender minority community: a glimpse into the health care disparity. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(4):559–582. doi: 10.1007/s10552-021-01549-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangesius J., Seppi T., Bates K., et al. Hypofractionated and single-fraction radiosurgery for brain metastases with sex as a key predictor of overall survival. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8639. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander K., Walters C.B., Banerjee S.C. Oncology patients’ preferences regarding sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) disclosure and room sharing. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(5):1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linee di indirizzo per l’applicazione della Medicina di Genere nella ricerca e negli studi preclinici e clinici Parte 1 Documento approvato in seduta plenaria dall’Osservatorio dedicato alla Medicina di Genere in data: 17/01/2023. https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/6744468/Linee+di+indirizzo+per+l%E2%80%99applicazione+della+Medicina+di+Genere+nella+ricerca+e+negli+studi+preclinici+e+clinici+Parte+1.pdf/5d119413-2b2b-b1b9-ee75-af28ff042844?t=1674042855609. Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 19.Gabriele L., Buoncervello M., Ascione B., Bellenghi M., Matarrese P., Carè A. The gender perspective in cancer research and therapy: novel insights and on-going hypotheses. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52(2):213–222. doi: 10.4415/ANN_16_02_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Randhawa S., Sferra S.R., Das C., Kaiser L.R., Ma G.X., Erkmen C.P. Examining gender differences in lung cancer screening. J Community Health. 2020;45(5):1038–1042. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rana R.H., Alam F., Alam K., Gow J. Gender-specific differences in care-seeking behaviour among lung cancer patients: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(5):1169–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller F., Büchel B., Köberle D., et al. Gender-specific elimination of continuous-infusional 5-fluorouracil in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: results from a prospective population pharmacokinetic study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(2):361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim H., Kim S.Y., Lee E., et al. Sex-dependent adverse drug reactions to 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer. Biol Pharm Bull. 2019;42(4):594–600. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b18-00707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmorino F., Rossini D., Lonardi S., et al. Impact of age and gender on the safety and efficacy of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of TRIBE and TRIBE2 studies. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1969–1977. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruzzo A., Graziano F., Galli F., et al. Sex-related differences in impact on safety of pharmacogenetic profile for colon cancer patients treated with FOLFOX-4 or XELOX adjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47627-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ioannou C., Ragia G., Balgkouranidou I., et al. Gender-dependent association of TYMS-TSER polymorphism with 5-fluorouracil or capecitabine-based chemotherapy toxicity. Pharmacogenomics. 2021;22(11):669–680. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2021-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conforti F., Pala L., Bagnardi V., et al. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):737–746. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benchetrit L., Torabi S.J., Tate J.P., et al. Gender disparities in head and neck cancer chemotherapy clinical trials participation and treatment. Oral Oncol. 2019;94:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conforti F., Pala L., Bagnardi V., et al. Sex-based heterogeneity in response to lung cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(8):772–781. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santoni M., Rizzo A., Mollica V., et al. The impact of gender on The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients: The MOUSEION-01 study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;170 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolff H.A., Conradi L.C., Beissbarth T., et al. Gender affects acute organ toxicity during radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer: long-term results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 phase III trial. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wettergren Y., Carlsson G., Odin E., Gustavsson B. Pretherapeutic uracil and dihydrouracil levels of colorectal cancer patients are associated with sex and toxic side effects during adjuvant 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2935–2943. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roengvoraphoj O., Eze C., Niyazi M., et al. Prognostic role of patient gender in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo H.S., Xu H.Y., Du Z.S., et al. Impact of sex on the prognosis of patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer underwent definitive radiotherapy: a propensity score-matched analysis. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duma N., Abdel-Ghani A., Yadav S., et al. Sex differences in tolerability to anti-programmed cell death protein 1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer: are we all equal? Oncologist. 2019;24(11):e1148–e1155. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muscogiuri G., Barrea L., Feola T., et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: does sex matter? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020;31(9):631–641. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irelli A., Sirufo M.M., D’Ugo C., Ginaldi L., De Martinis M. Sex and gender influences on cancer immunotherapy response. Biomedicines. 2020;8(7):232. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8070232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Triggianese P., Novelli L., Galdiero M.R., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced autoimmunity: the impact of gender. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(8) doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubino R., Marini A., Roviello G., et al. Endocrine-related adverse events in a large series of cancer patients treated with anti-PD1 therapy. Endocrine. 2021;74(1):172–179. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02750-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang S.R., Nikita N., Banks J., et al. Association between sex and immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes for patients with melanoma. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trojnar A., Domagała-Kulawik J., Sienkiewicz-Ulita A., et al. The clinico-pathological characteristics of surgically treated young women with NSCLC. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022 Dec;11(12):2382–2394. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caliman E., Petrella M.C., Rossi V., et al. Gender matters. Sex-related differences in immunotherapy outcome in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2022 doi: 10.2174/1568009622666220831142452. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saad M., Lee S.J., Tan A.C., et al. Enhanced immune activation within the tumor microenvironment and circulation of female high-risk melanoma patients and improved survival with adjuvant CTLA4 blockade compared to males. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):253. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03450-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuminello S., Alpert N., Veluswamy R.R., et al. Modulation of chemoimmunotherapy efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer by sex and histology: a real-world, patient-level analysis. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarasqueta C., Zunzunegui M.V., Enríquez Navascues J.M., et al. Gender differences in stage at diagnosis and preoperative radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):759. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tulchiner G., Pichler R., Ulmer H., et al. Sex-specific hormone changes during immunotherapy and its influence on survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70(10):2805–2817. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02882-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ioannou C., Ragia G., Balgkouranidou I., et al. MTHFR c.665C>T guided fluoropyrimidine therapy in cancer: gender-dependent effect on dose requirements. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 2022 Mar 11;37(3):323–327. doi: 10.1515/dmpt-2021-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rowse P.G., Jaroszewski D.E., Thomas M., Harold K., Harmsen W.S., Shen K.R. Sex disparities after induction chemoradiotherapy and esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(4):1147–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuki H., Hiroshima Y., Miyake K., et al. Reduction of gender-associated M2-like tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28(2):174–182. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bai D., Feng H., Yang J., Yin A., Qian A., Sugiyama H. Landscape of immune cell infiltration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma to aid immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(6):2126–2139. doi: 10.1111/cas.14887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mederos N., Friedlaender A., Peters S., Addeo A. Gender-specific aspects of epidemiology, molecular genetics and outcome: lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5(Suppl 4) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conti L., Del Cornò M., Gessani S. Revisiting the impact of lifestyle on colorectal cancer risk in a gender perspective. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;145 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holme Ø., Løberg M., Kalager M., et al. Long-term effectiveness of sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in women and men: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(11):775–782. doi: 10.7326/M17-1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmuck R., Gerken M., Teegen E.M., et al. Gender comparison of clinical, histopathological, therapeutic and outcome factors in 185,967 colon cancer patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405(1):71–80. doi: 10.1007/s00423-019-01850-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li D., Xu X., Liu J., et al. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) incidence and trends vary by gender, geography, age, and subcategory based on population and hospital cancer registries in Hebei, China (2008-2017) Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(8):2087–2093. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trojnar A., Domagała-Kulawik J., Sienkiewicz-Ulita A., et al. The clinico-pathological characteristics of surgically treated young women with NSCLC. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022;11(12):2382–2394. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen J., Shih J., Tran A., et al. Gender-based differences and barriers in skin protection behaviors in melanoma survivors. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3874572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roh M.R., Eliades P., Gupta S., Grant-Kels J.M., Tsao H. Cutaneous melanoma in women. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(1 Suppl):S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bellenghi M., Puglisi R., Pontecorvi G., De Feo A., Carè A., Mattia G. Sex and gender disparities in melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(7):1819. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu X.Q., Yap M.L., Cheng E.S., et al. Evaluating prognostic factors for sex differences in lung cancer survival: findings from a large Australian cohort. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(5):688–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zloto O., Pe'er J., Frenkel S. Gender differences in clinical presentation and prognosis of uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(1):652–656. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gambacciani M., Monteleone P., Sacco A., Genazzani A.R. Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial, ovarian and colorectal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taghizadeh H., Zöchbauer-Müller S., Mader R.M., et al. Gender differences in molecular-guided therapy recommendations for metastatic malignant mesothelioma. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(7):1979–1988. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hohla F., Hopfinger G., Romeder F., et al. Female gender may predict response to FOLFIRINOX in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a single institution retrospective review. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(1):319–326. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benhaim L., Gerger A., Bohanes P., et al. Gender-specific profiling in SCN1A polymorphisms and time-to-recurrence in patients with stage II/III colorectal cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluoruracil chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14(2):135–141. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gasinska A., Adamczyk A., Niemiec J., Biesaga B., Darasz Z., Skolyszewski J. Gender-related differences in pathological and clinical tumor response based on immunohistochemical proteins expression in rectal cancer patients treated with short course of preoperative radiotherapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(7):1306–1318. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keck B., Ott O.J., Häberle L., et al. Female sex is an independent risk factor for reduced overall survival in bladder cancer patients treated by transurethral resection and radio- or radiochemotherapy. World J Urol. 2013;31(5):1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0971-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tran B., Kopetz S., Tie J., et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(20):4623–4632. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perotti V., Fabiano S., Contiero P., et al. Influence of sex and age on site of onset, morphology, and site of metastasis in colorectal cancer: a population-based study on data from four Italian cancer registries. Cancers. 2023;15:803. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cai Y., Rattray N.J.W., Zhang Q., et al. Sex differences in colon cancer metabolism reveal a novel subphenotype. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4905. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chrysanthou E., Sehovic E., Ostano P., Chiorino G. Comprehensive gene expression analysis to identify differences and similarities between sex- and stage-stratified melanoma samples. Cells. 2022;11(7):1099. doi: 10.3390/cells11071099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gupta S., Artomov M., Goggins W., Daly M., Tsao H. Gender disparity and mutation burden in metastatic melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11):djv221. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olsen C.M., Thompson J.F., Pandeya N., Whiteman D.C. Evaluation of sex-specific incidence of melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(5):553–560. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lorenz K., Schneider R., Elwerr M. Thyroid carcinoma: do we need to treat men and women differently? Visc Med. 2020;36(1):10–14. doi: 10.1159/000505496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li P., Ding Y., Liu M., Wang W., Li X. Sex disparities in thyroid cancer: a SEER population study. Gland Surg. 2021;10(12):3200–3210. doi: 10.21037/gs-21-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shobab L., Burman K.D., Wartofsky L. Sex Differences in differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2022;32(3):224–235. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freudenstein D., Litchfield C., Caramia F., et al. TP53 status, patient sex, and the immune response as determinants of lung cancer patient survival. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6):1535. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burton H., Pilkington P., Bridge P. Evaluating the perceptions of the transgender and non-binary communities of pelvic radiotherapy side effect information booklets. Radiography (Lond) 2020;26(2):122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan S., Duong Dinh T.A., Westhofen M. Evaluation of gender-specific aspects in quality-of-life in patients with larynx carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136(12):1201–1205. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2016.1211319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trusson D., Quincey K. Breast cancer and hair loss: experiential similarities and differences in men’s and women’s narratives. Cancer Nurs. 2021;44(1):62–70. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.West C., Paul S.M., Dunn L., Dhruva A., Merriman J., Miaskowski C. Gender differences in predictors of quality of life at the initiation of radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(5):507–516. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.507-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morrison L., Thomas R.L. Comparing men’s and women’s experiences of work after cancer: a photovoice study. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(10):3015–3023. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seifart C., Riera Knorrenschild J., Hofmann M., Nestoriuc Y., Rief W., von Blanckenburg P. Let us talk about death: gender effects in cancer patients' preferences for end-of-life discussions. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(10):4667–4675. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05275-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]