Abstract

Flavonoids are natural phytochemicals that have therapeutic effects and act in the prevention of several pathologies. These phytochemicals can be found in lemon, sweet orange, bitter orange, clementine. Hesperidin and hesperetin are citrus flavonoids from the flavanones subclass that have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor and antibacterial potential. Preclinical studies and clinical trials demonstrated therapeutical effects of hesperidin and its aglycone hesperetin in various diseases, such as bone diseases, cardiovascular diseases, neurological diseases, respiratory diseases, digestive diseases, urinary tract diseases. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the biological activities of hesperidin and hesperetin, their therapeutic potential in various diseases and their associated molecular mechanisms. This article also discusses future considerations for the clinical applications of hesperidin and hesperetin.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant, Antitumor, Antibacterial, Hesperidin, Hesperetin

1. Introduction

Citrus flavonoids, including hesperidin (Hsd) and hesperetin (Hst), have a wide range of biological effects. Citrus fruits such as lemon, sweet orange, bitter orange, clementine are rich in Hsd. Hesperidin is also found in mint, Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort), Salvia miltiorrhiza (red sage) [1]. Hesperidin and hesperetin are found in the same plant material, Hsd is a metabolite of Hst. Hesperidin can be readily extracted from citrus processing residue [2,3]. However, the extraction process for Hst is complicated and increases the cost to end users.

Hesperidin (C28H34O15), a flavanone glycoside, which is composed of aglycone Hst (C16H14O6) and a sugar moiety known as rutinoside. Rutinoside is a disaccharide composed of rhamnose and glucose, with glucose attached to C7 of the Hst ring. The chemical name for Hst is 4'-methoxy-3',5,7-trihydroxyflavanone (Fig. 1A), while that for Hsd is 4'-methoxy-3',5,7-trihydroxyflavanone-7-rhamnoglucoside (Fig. 1B) [4,5].

Fig. 1.

Chemicai structure of Hsd(A)、Hst(B)、HD-14(C) and HD-16 (D).

Hesperidin can be isolated using various methods such as extraction, percolation, batch or continuous reflux. The quality, yield, efficiency of extraction are influenced by different factors such as solvent type, temperature, extraction time and liquid-solid ratio. Common solvents in this extraction process include dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methanol, or aqueous combinations of these solvents in various ratios. The another newer methods have replaced impregnation and Soxhlet extraction, resulting in improved efficiencies and selectivities. Hesperidin offers advantages such as enhanced safety, minimal cumulative side effects, low effective dose. Mice were administered Hsd at dosages ≤5 percent to validate its safety and even after long-term administration, Hsd caused no mutation, toxicity, or carcinogenesis [6]. Only 10 percent of individuals undergoing hesperidin therapy present with mild-to-moderate side effects [7]. The effects of Hsd and Hst have been investigated on exercise performance [[8], [9], [10]]. Oral administration of Hsd, Hst, or orange juice can aid muscle recovery and enhance performance in elite and recreational athletes by optimizing oxygen and nutrient supply to the muscles and improving anaerobic performance.

This review summarizes the mechanisms underlying the biological activities and therapeutic roles of hesperidin and hesperetin in various diseases as well as potential considerations for their future clinical applications.

2. Hesperidin and hesperetin bioavailability

Both Hsd and Hst exhibit approximately 20 percent bioavailability [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. Owing to its limited water solubility, only a small quantity of Hsd molecules are released into the aqueous environment of the gastrointestinal tract [16]. P-glycoprotein in the alimentary canal eliminates ingested chemicals from the extracellular space and inhibits their absorption [17]. Therefore, hesperidin may be released into the external environment following absorption by the intestinal epithelium. Numerous efforts have been made to improve the water solubility of Hsd.

Hesperetin derivative-14 (HD-14) (Fig. 1C) was synthesized using Mannich base synthesis and its molecular formula is C34H32Cl2N2O6. Its chemical name is (S)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-7-{[4-(trifluoromethyl) benzyl] oxy} chroman-4-one and it exhibits improved water solubility and bioavailability compared to its parent compound. Hesperetin derivative-14 also demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and prevented liver fibrosis in mice [18]. Hesperetin derivative-16 (HD-16) was synthesized by combining Hsd with various brominated aromatic and alkyl groups (Fig. 1D); its molecular formula is C19H19O6. The chemical name of the compound is (S)-7-(allyloxy)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl) chroman-4-one and it exhibits improved water solubility and activity compared to Hsd [19]. Hesperetin derivative-16 ameliorates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice [20].

Cyclodextrin glucosyltransferase was used to synthesize 8α-GH by combining glucose with Hsd. The latter displayed a 3.7-fold higher bioavailability and 10,000-fold increased water solubility compared with Hsd [21]. Dietary 8α-GH significantly reduces white adipose tissue weight in mice [22]. Methylation improves flavonoid bioavailability, metabolic stability, tissue distribution and biological activity [23]. Alkaline conditions promote the formation of hesperidin methyl chalcone (HMC), which exhibit increased metabolic resistance and transport capacity compared to their precursor compounds [12]. Hesperidin methyl chalcone has shown efficacy in treating chronic venous insufficiency [24,25], colitis, arthritis and UVB irradiation-induced effects [[26], [27], [28]]. Hesperidin methyl chalcone also ameliorates high-fat diet-induced lipid and sugar metabolism disorders and increases energy expenditure by promoting fat degradation [29]. Hesperidin -7-O-glucoside exhibited superior efficacy compared with its parent compound in restoring the hepatic antioxidant system and releasing cytokines [30]. Hesperidin exhibits limited targeting and oral absorption. A mannose-6-phosphate bovine serum albumin-labelled Hsd liposome carrier system targeting hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) was developed to prevent liver fibrosis in rats [31]. Garg [32] developed sulfonated hesperidin (S-Hsd) as an inhibitor of sexually transmitted infection (STI)-causing bacteria, specifically Chlamydia trachomatis and gonococci, without affecting normal vaginal flora such as Lactobacillus gasseri. It provides protection against certain STIs without causing adverse effects on sperm or vaginal tissues [32].

3. Biological activities of Hsd and Hst

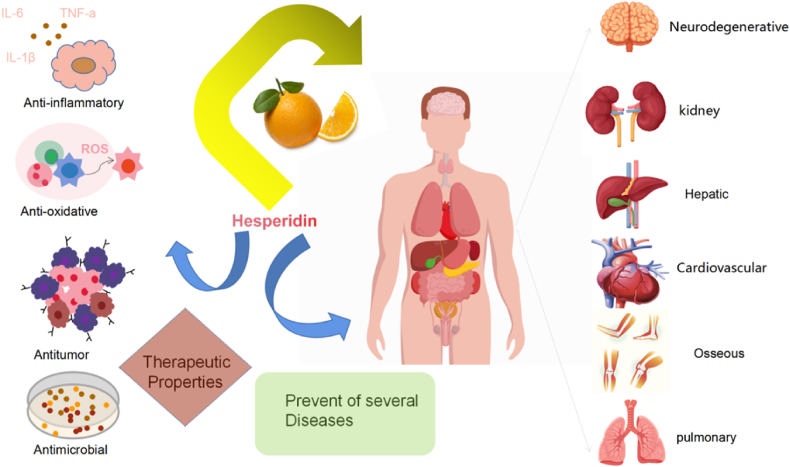

Hesperidin and hesperetin exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor and antimicrobial properties [33]. In recent years, various in vivo and in vitro studies have explored the therapeutic potential of Hsd and Hst in treating a range of diseases, including bone, cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory, digestive and urinary tract diseases (Fig. 2). Table 1 detailing the specific model, route, mechanism and reference of Hsd and Hst have been provided.

Fig. 2.

Biological activity of Hsd and Hst and its impact on diseases.

Table 1.

In vitro and in vivo studies of Hsd and Hst for disease treatment.

| Biological activities | Disease | Flavanone | In Vitro Models | In Vivo Models | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant | Arthritis | Hsd | Rheumatoid arthritis rats | Reduce the levels of catalase, nitric oxide and free radicals. | [140] | |

| Postmenopausal osteoporosis | Hst | RANKL-induced RAW 264.7 cells | Ovariectomized mice | Inhibit Jnk mediated Irf-3/c-Jun activation. | [141] | |

| Postmenopausal osteoporosis | Hst | Ovariectomized rats | Regulate bone morphogenetic protein pathway and osteopontin expression | [142] | ||

| Genotoxicity | Hsd | Cyclophosphamide-induced mice | Reduce the frequency of MnPCE and increased proliferation on bone marrow cellularity that affected by CP. | [143] | ||

| Cardiovascular Remodeling |

Hsd | l-arginine methyl ester-induced rats | Down-regulation of TGF-β1 and TNF-R1 protein expression | [99] | ||

| Metabolic Syndrome | Hsd | Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Stimulate phosphorylation of Src, Akt, AMP kinase, endothelial NO synthase to produce NO. | [144] | ||

| Cardiomyocyte apoptosis | Hst | LPS-induced H9C2 cells | Downregulate the protein expression of Bax, upregulated the expression of Bcl-2 and attenuated the phosphorylation level of JNK | [145] | ||

| Protect cardiomyocytes | Hsd | Senescent rats | Enhance the activity of enzyme antioxidants | [37] | ||

| Myocardial ischemia reperfusion | Hsd | Experimentally-induced rats | Increase tissue nitrite, antioxidant level and Reduce inflammation, arrhythmias and apoptosis | [146] | ||

| Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance | Hsd | ISO-induced rats | Reduce levels of plasma cholesterol, LDL-C, VLDL-C, TG, FFA | [1] | ||

| hypercholesterolemia and fatty liver | Hsd | High-cholesterol diet-induced rats | Inhibit synthesis and absorption of cholesterol and regulate the expression of mRNA for RBP, C-FABP, H-FABP | [147] | ||

| Cognitive impairment | Hsd | APP/PS1 mice | Reduce the levels of ROS, LPO, protein carbonyl, 8-OHdG, increasing the activities of HO-1, SOD, catalase, GSH-Px | [148] | ||

| Diabetes Depression | Hsd | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | Enhancement of Glo-1 and activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway | [149] | ||

| Acute lung inflammation | Hsd | Ventilator-induced lung injury mice | Reduce recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways and the formation of CCL-2 and IL-12 | [150] | ||

| Acute lung injury | Hst | LPS-induced ALI mice | (1)Inhibit MAPK activation, regulate Iκβ degradation, block the interaction MD2 and its co-receptor TLR4 (2)Associated with the TLR4-MyD88-NF-κβ pathway. |

[151] [152] [153] |

||

| Acute gastric injury | Hsd | Streptozotocin and nicotinamide-induced rats | Increase antioxidant defense capacity through the induction of HO-1 via ERK/Nrf2 pathway. | [154] | ||

| Hepatotoxicity Nephrotoxicity | Hsd | Paclitaxel-induced rats | Amendment of Nrf2/HO-1 and caspase-3/Bax/Bcl-2 signaling pathways. | [155] | ||

| Renal injury | Hsd | Aluminum-induced rats | Inhibit the MMP-9-related signaling pathway activated by ALCL3. | [138] | ||

| Renal injury | Hsd | sodium fluoride-induced rats | Inhibit PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. | [156] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | Postmenopausal osteoporosis | Hsd | Ovariectomized mice Ovariectomized rats |

Inhibition of osteoclast superoxide reduces bone Resorption. | [157] [158] [159] |

|

| Osteoporosis | Hst | RANKL-induced Murine macrophage cells | LPS-induced mice | (1)Inhibit activation of NF-κβ and MAPK signaling (2)Scavenger active oxygens (3)Activate the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. |

[160] | |

| Cardiac hypertrophy | Hsd | Isoproterenol-induced rats | Interfering with NF‐κB signaling via JNK phosphorylation | [161] | ||

| Hypertensive | Hsd | Spontaneously hypertensive rats | Improving NO bioavailability in endothelial cells. | [162] | ||

| Hypertensive | Hsd | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | Spontaneously hypertensive rats | Stimulate CaMKII/p38 MAPK/MasR expression and CaMKII/eNOS/NO production | [163] | |

| Parkinson's Disease | Hsd | 6-OHDA-induced mice | Attenuate the striatal levels of proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α, interferongamma, interleukin-1β, interleukin-2, interleukin-6 | [164] | ||

| NeuroinflammationMemory Impairments | Hst | LPS-induced HT-22 cells BV2 cells |

LPS-induced mice | Through the NF-κβ signaling pathway reduced the protein expression level of TNF-α and IL-1β cytokines | [165] | |

| Ischemic stroke | Hst | Middle cerebral artery occlusion mice | Inhibit the TLR4-NF-κβ pathway | [166] | ||

| Temporal lobe epilepsy | Hst | Kainic acid-induced mice | Inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules | [167] | ||

| Parkinson's Disease | Hsd | OHDA-induced zebrafish | Downregulated the kinases lrrk2 and gsk3β along with casp3, casp9, polg | [168] | ||

| Asthma | Hsd | HDM-induced mice | Decrease subepithelial fibrosis, smooth muscle hypertrophy in airways, lung atelectasis to ameliorating airway structural remodeling | [169] | ||

| Lung injury | Hsd | Acrolein-induced LLC cells | Acrolein-induced mice | Attenuate the expression levels of the activated forms of p38,p53, JNK | [170] | |

| Peptic ulcers | Hsd | Indomethacin-induced rats | Increase COX-2 and GSH expression | [171] | ||

| Peptic ulcers | Hsd | Stress or ethanol-induced rats | Reduce neutrophil migration and strengthen the mucus barrier close to the mucosa | [172] | ||

| Cholestasis | Hsd | FXR-suppressed HepaRG cells. | FXR-suppressed HepaRG mice | Activate farnesoid X receptor (FXR) | [173] | |

| Acute renal injury | Hsd | Cisplatin-induced rats | Attenuate caspase-3 and DNA damag. | [135] | ||

| Hepatotoxicity | Hsd | Acetaminophen-induced rats | (1)Increase GSH, GST, SOD, GPx levels and deplete MDA level. (2)Elevate TNF-α and lower the levels of interleukin IL-4. |

[174] | ||

| Testicular and kidney damage | Hsd | Carbon tetrachloride-induced rats | Repaire renal and testicular architecture and suppress NF-κβ immunoexpression. | [175] | ||

| Renal injury | Hsd | Colistin-induced rats | Decrease the levels of MDA and inflammatory parameters and Increase GSH, SOD, CAT, GSH-Px levels. | [136] | ||

| Acute kidney injury | Hst | Cisplatin-induced rats | Activate Nrf2, and attenuate the MAPK signaling pathway. | [176] | ||

| Anticancer | Osteosarcoma | Hsd | MG-63 cells | BALB/c mice | Inhibition of cell migration and invasion, cell cycle arrest and induction of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. | [177] |

| Glioma | Hsd | C6 glioma cells graft rats | Inhibit the proliferation of cerebrally implanted C6 glioma and involves suppression of HIF-1α/VEGF pathway | [178] | ||

| Lung cancer | Hsd | NSCLC A549 cells | (1)Induce apoptosis through the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and induced G0/G1 arrest. (2)inhibite the migratory and invasive capabilities of lung cancer cells by the mediation of the SDF-1/CXCR-4 signaling cascade. |

[58] [179] |

||

| Lung cancer | Hsd | Cisplatin-induced A549 cells |

Decrease the expression of P-gp and increased the intracellular accumulation of the P-gp substrate, rhodamine 123 | [180] | ||

| Lung cancer | Hsd | LLC cells | Lung carcinoma mice | Increase pinX1 protein expression. | [181] | |

| Gastric cancer | Hsd | MNNG-induced rats | Activate autophagy and the PI3K/AKT pathway. | [182] | ||

| Esophageal cancer | Hst | Eca109 cells | Human xenograft tumor nude mice | Depletion of GSH, accumulation of ROS, increase of cleaved caspase-9 and cleaved caspase-3 | [183] | |

| Ehrlich ascites carcinoma | Hsd | Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) mice | Down-regulate Bcl2 and Stimulate Caspase3 and Bax genes expression | [184] | ||

| Liver cancer | Hsd | DEN/CCl4-induced rats | Activate Nrf2/ARE/HO-1 and PPARγ pathways. | [185] | ||

| Gastric cancer | Hsd | Xenograft tumor nude mice | Activate the mitochondrial pathway by increasing the ROS. | [129] | ||

| Urinary-bladder carcinogenesis | Hsd | N-butyl-N-nitrosamine-induced mice | Decrease cell proliferation by the induction of cell differentiation. | [186] | ||

| Antimicrobial | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection | Hsd | SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein S1 Subunit-Induced A549 cells |

Attenuated inflammasome machinery protein expressions (NLRP3, ASC, Caspase-1), as well as inactivated the Akt/MAPK/AP-1 pathway. | [187] | |

| Hst | ATCC CRL-1739 cells | ATCC 49503 ATCC 43504 ATCC 51932 ATCC700392 |

(1)block the expression of genes involved in H. pylori's transcriptional (rpoA, rpoB, rpoD, rpoN) and replication (dnaE, dnaN, dnaQ, holB) machinery. (2)reduce the expression of genes involved in H. pylori adhesion and motility (sabA, alpA, alpB, hpaA, hopZ) |

[188] |

3.1. Antioxidant capacity

Oxidative stress is a consequence of elevated levels of free radicals, specifically reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS), in response to various harmful stimuli. An imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in the body can result in tissue damage. Reactive oxygen species encompasses the superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, whereas RNS encompasses nitric oxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide and peroxynitrite. These highly reactive molecules are directly or indirectly involved in maintaining the oxidative and antioxidative equilibrium within the body and interact with key signaling molecules to activate various pathways, including the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell (NF-κB) signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway and mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

Hesperidin and hesperetin enhance cellular antioxidant defense by eliminating free radicals and ROS (Fig. 3). Specifically, hesperidin and hesperetin effectively neutralize ROS, including superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, peroxynitrite and NO radical [[34], [35], [36]]. The upregulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and extracellular signal-related kinases (ERK) 1/2 further enhances cellular antioxidant defense [37,38] by increasing heme oxygenase (HO-1) expression, reducing intracellular pro-oxidants and increasing endogenous antioxidant bilirubin. Heme oxygenase then increases carbon monoxide (CO) levels in anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory cells and induces guanylate cyclase [39]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 upregulates the expression of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione-S-transferase (GST). Additionally, the ERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway induces HO-1 expression, which further enhances the cellular antioxidant defense [39].

Fig. 3.

Basic cellular mechanism of antioxidant activity of Hsd and Hst.+, Raise/activate; -, Deactivate/suppress.

These studies indicate that Hsd and Hst possess antioxidant activity and potential efficacy.

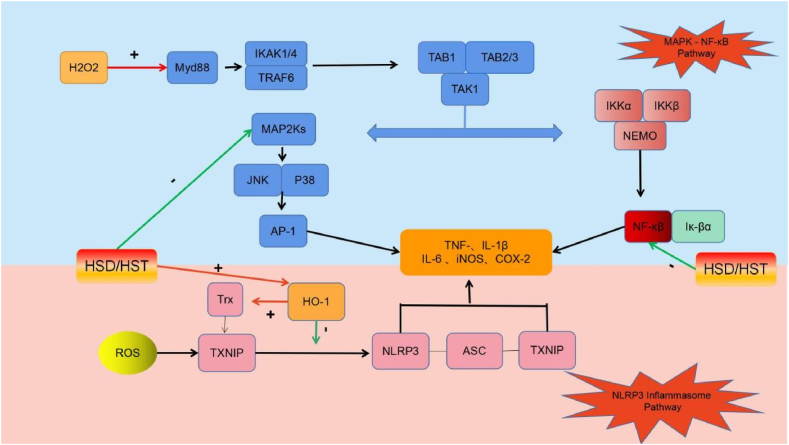

3.2. Anti-inflammatory effects

Oxidative stress frequently elicits an accompanying inflammatory response through the activation of thioredoxin (Trx)-interacting protein (Txnip), which binds to the nucleotide-binding oligomerization structural domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3). This interaction facilitates the binding of NLRP3 to apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD domain (ASC) and cysteine aspartate protease-1 (Caspase-1), leading to activation of the NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle and increased secretion of the proinflammatory mediator interleukin 1β (IL-1β) [40,41]. Nuclear factor kappa-B transcription factors are activated, leading to transcriptional upregulation of inflammatory cytokine genes such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) [42]. Nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway activation is closely associated with MAPK activation, which is a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase involved in intracellular signaling pathways during the proinflammatory response [43]. Additionally, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) can contribute to inflammatory signaling by regulating leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions [44,45].

Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit the Txnip/NLRP3, MAPK and NF-κB inflammatory pathways (Fig. 4). Additionally, hesperetin upregulates HO-1 expression, inhibits the activation of Txnip and its binding to NLRP3 and impedes the binding of NLRP3 to downstream caspase-1 and ASC, thereby inhibiting inflammatory body (inflammasome) activation and downregulating IL-1β levels [46]. Heme oxygenase also upregulates Trx expression, downregulates Txnip expression, promotes Txnip binding and indirectly inhibits inflammasome activation [47,48]. Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit hydrogen peroxide-induced phosphorylation of ERK, c-Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK), p38, NF-κB and NF-κB inhibitory protein (IκB) [49,50]. They also hinder IκB degradation, prevent NF-κB signaling pathway activation [51] and downregulate TNF-α and IL-1β as well as the inflammatory mediators IL-6, iNOS and CO. Furthermore, hesperidin suppresses MAPK kinase (MEK)/ERK phosphorylation in the MAPK signaling pathway, downregulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) expression and reduces inflammation [52].

Fig. 4.

Basic cellular mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity of Hsd and Hst.+: Raise/Activate; -: Deactivate/suppress.

These findings highlight the anti-inflammatory properties and potential therapeutic efficacy of Hsd and Hst.

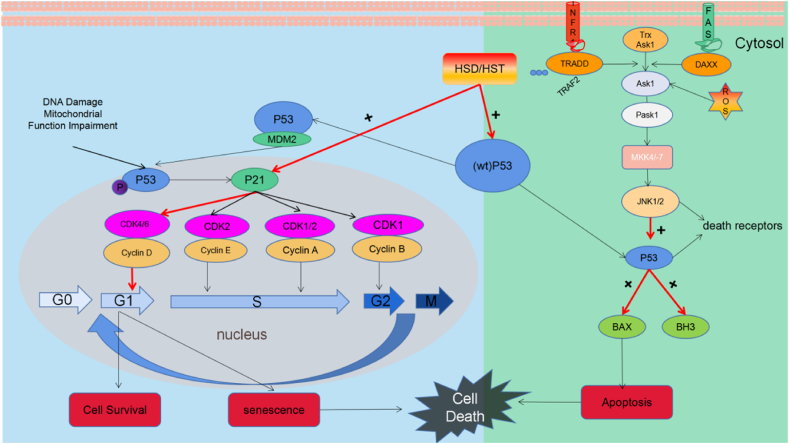

3.3. Anti-cancer efficacy

Cells undergo the cell cycle, a complex process facilitating growth and replication that is regulated by two main groups of genes: oncogenes (such as Ras and c-Myc) and tumor suppressor genes (such as p53) [53]. Cell cycle progression is regulated by the interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes, which consist of a CDK catalytic subunit and cyclin regulatory subunit. The primary CDKs involved in cell cycle progression are CDK1, -2, -4 and -6 [54]. Cyclin-dependent kinase complex activity is regulated by CDK inhibitors (CKIs), such as those from CIP/KIP (p21, p27, p57) and INK4 families [55]. The cell machinery orchestrates cell cycle progression by rhythmically modulating the synthesis and degradation of cyclins. The Tumor Suppressor Protein (P53) pathway, cellular energy levels and ratio of anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic proteins determine cell cycle arrest or apoptosis following DNA damage and/or mitochondrial dysfunction [56]. Tumor Suppressor Protein upregulates the expression of the CDK inhibitor p21 Cip1/Waf1 (P21), which forms complexes with CDK2, CDK-4, CDK-6 and suppresses the G1/S phase transition.

Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit the G1/S transition in cancer cells through p53 (Fig. 5). Hesperidin increases the expression of wild-type p53 in breast cancer, lung cancer and leukemia cell lines in vitro and in colon cancer in vivo [[57], [58], [59]]. Hesperetin also upregulates wild-type p53 in SiHa cervical cancer cell line in vitro and in a breast cancer model in vivo [60,61]. The cyclin D-CDK4 complex phosphorylates the retinoblastoma protein pRb, leading to the generation of transcription factor (TF) E2F, which facilitates the G1/S transition and upregulates the expression of cyclin E and cyclin [62]. Additionally, circulation also upregulates cyclin E expression. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and cyclin E complexes phosphorylate downstream targets, thereby increasing DNA replication and facilitating progression to the S phase. Hesperidin upregulates p21 expression and downregulates cyclin D1 expression in A549 lung cancer cells, leading to G1 cell cycle arrest [58]. Hesperetin has similar effects on the ECA-109 esophageal cancer cell line [63]. It also downregulated cyclin E and CDK2 expression in HeLa cervical cancer and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Therefore, it inhibits DNA replication [64,65]. C-Jun amino-terminal kinases-activated apoptosis is a crucial event in the MAPK pathway. C-Jun amino-terminal kinases influences cell death, proliferation and embryonic development. Increased FAS and TNF receptor activation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and cytosolic ROS levels lead to the dissociation and phosphorylation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) from Trx, resulting in the activation of JNK1/2 [56]. JNK1/2 and p53 regulate apoptosis. Hesperetin increased ROS levels in wild-type p53 MCF-7 breast cancer cells through phosphorylation of ASK1 and JNK [66]. It also upregulated JNK mRNA expression in the p53 mutant A431 cell line. Therefore, it may induce p53-independent apoptosis [67].

Fig. 5.

Basic cellular mechanism of anti-cancer activity of Hsd and Hst.+: Raise/Activate; -: Deactivate/suppress.

These findings highlight the anti-cancer activity and efficacy of Hsd and Hst.

3.4. Antimicrobial efficacy

Hyaluronidase performs multiple functions, including serving as a structural component in epithelial cell extracellular matrix (ECM) development, facilitating cell migration, participating in cell-cell signaling and triggering ECM remodeling enzyme activation and inflammation. Flavonoids exhibit antibacterial properties by forming complexes with hyaluronidase via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit bacterial DNA synthesis, reduce motility, decrease membrane permeability and downregulate metalloenzymes, while enhancing host defense [32,[68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75]]. Hsd modifies the enzyme active site and reduces enzyme activity [76]. Both Hesperidin and hesperetin possess antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea, Trichoderma cinerea and Aspergillus fumigatus [77,78].

Hesperidin has demonstrated antiviral efficacy against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [79,80]. It inhibits the interaction between angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [[81], [82], [83], [84]]. Hesperidin also exhibits strong binding affinity for other SARS-CoV-2 proteins, including 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLPro/MPRO) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [85]. Hesperidin inhibits pp1a and pp1ab, the first proteins transported from the viral genome [84]. In contrast, hyaluronidase facilitates viral access to target cells and tissues, neutralizing the protective antiviral effect of Hsd in HeLa cells. Hesperidin exerts antiviral effects by inhibiting hyaluronidase [86]. The internal ribosome entry site is crucial for viral protein translation and is a promising therapeutic target for enterovirus 71 (EV-71). Hsd can potentially inhibit viral protein translation [87].

Hesperidin at 200 mg/ml concentration was highly effective in eliminating adult worms. However, at lower concentrations, the schistosomicidal effect was minimal or non-existent. These results suggest that hesperidin is effective only against adult worms at higher concentrations. The precise mechanism underlying the schistosomicidal effect of hesperidin in vitro remains unclear and warrants further investigation [88].

These findings indicate that Hsd exhibits antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal and antiparasitic activities. However, further research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and to optimize the clinical dosage and form of administration for various applications.

4. Hesperidin and hesperetin as therapeutic agents

4.1. Bone diseases

Bone, a complex tissue composed of a mineralized organic matrix and various cells, is highly resistant to mechanical stress [89]. Healthy bone metabolism involves a delicate balance between bone generation and resorption [90]. However, aging and disease can disrupt this process and affect bone metabolism [91]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β, significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of bone diseases [92]. In particular, TNF-α downregulates the synthesis of major ECM components and disrupts cartilage by inhibiting the anabolic activities of chondrocytes [93,94]. Additionally, TNF-α stimulates the production of MMPs, particularly MMP-13, by activated chondrocytes, further contributing to cartilage degradation [91]. In addition, the NF-κB signaling pathway, activated by TNF-α, facilitates the proinflammatory function of TNF-α [95]. In osteoarthritis (OA), inflammatory cytokines not only have destructive effects but also contribute to chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degeneration [92].

Hesperidin reversed TNF-α-induced upregulation of IL-1β, PTGS2 and MMP-13. Furthermore, Hesperidin inhibited TNF-α-induced degradation of the chondrocyte extracellular matrix and reversed TNF-α-induced inhibitory effects on chondrocyte proliferation [96]. Hesperidin reduces serum levels of RANKL, TNF, IL-1β and IL-6 receptor activators and increases osteocalcin levels in a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced osteoporosis [96].

Hesperidin and hesperetin possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that support bone cell metabolism, making them potential candidates for prevention and treatment of OA and osteoporosis.

4.2. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD)

Following myocardial infarction (MI), collagen-producing myofibroblasts are activated, contributing to the gradual development of replacement fibrosis. Myocardial fibrosis undoubtedly affects left ventricular remodeling. Myocardial fibroblast activation is triggered by myocardial fiber stretching and inflammation. Myocardial fibrosis is regulated by inflammation, various cell types, paracrine mechanisms (such as TGFs) and collagen-degrading enzymes (such as MMPs) [97].

Hesperidin inhibits both caspase-3 and myeloperoxidase and smooth muscle actin alpha (α-SMA) and MMP-2 play crucial roles in preventing cardiac dysfunction and myocardial remodeling following MI by inhibiting collagen deposition and fibroblast migration [98]. Hesperidin and hesperetin effectively prevented hypertension and cardiac remodeling in a rat model of N(ω)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced hypertension, as evidenced by the reduction in left ventricular wall thickness, cross-sectional area (CSA), fibrosis, vascular remodeling and expression of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and TNF-1 proteins [99].

Hesperidin upregulates serum and hepatic SOD and GSH-Px in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient (LDLR−/−) mice fed a high-fat diet, which suggests an increased endogenous defense against oxidative stress [100]. Furthermore, hesperidin-treated animals exhibited less severe atherosclerosis than their control counterparts, as hesperidin-treated animals had lower serum oxidized (OX)-LDL, IL-6 and TNF levels than controls [100].

Therefore, hesperidin and hesperetin safeguards cardiovascular health by exhibiting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, as well as other pharmacological effects.

4.3. Neurological diseases

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is caused by the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and various mechanisms, such as the generation of ROS [101] and the activation of astrocytes and microglia [102]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 regulates endogenous antioxidant mechanisms [103,104]. Elevated ROS levels lead to the downregulation of Nrf2 and HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1), contributing to the pathogenesis of AD-like effects [105]. Microglia are tissue macrophages that perform tissue maintenance and immune surveillance [106]. Activated microglia express various pattern recognition receptors, specifically from the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family, which enable them to detect microbial invaders. Toll-like receptor activation exacerbates various signaling pathways, resulting in the activation of inflammatory agents such as cytokines, ROS and NO [107]. Microglial expression of TLRs in the central nervous system (CNS) is the first line of defense against endogenous and exogenous agents [107,108]. Toll-like receptor participate in Aβ signaling, triggering an intracellular mechanism that leads to the activation of proinflammatory agents and clearance of Aβ [[109], [110], [111]]. Toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory responses induced by Aβ can result in neurotoxicity. Toll-like receptors 2, 4 and 9 have been suggested as potential therapeutic targets for AD treatment [112,113].

Hesperidin mitigates LPS-induced neuroinflammation, cell death and memory impairment via TLR4/NF-κB signal transduction. Hesperidin improves TLR4-mediated ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1/glial fibrillary acidic protein (Iba-1/GFAP) and downregulates inflammatory cytokines, leading to a decrease in LPS-induced memory impairment. Hesperetin efficiently reverses the pathological outcomes of Aβ treatment in mice and cells, primarily by inhibiting oxidative stress via regulation of Nrf2/HO-1, reducing neuroinflammation by regulating TLR4/NF-κB and preventing apoptotic cell death by regulating Bax/Bcl-2, Caspase-3 and Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in the Aβ mouse model and in cells [114].

Hesperidin and hesperetin demonstrate potential as novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of AD-like neurodegenerative disorders owing to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

4.4. Respiratory diseases

Idiopathic Pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is primarily characterized by injury to the epithelial cells (ECs), increased levels of alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, one of the myofibroblast markers) and ECM in the alveolar walls, myofibroblast accumulation and matrix remodeling resulting in distorted alveolar structure and lung parenchyma remodeling. This leads to progressive alterations in lung functions [115], including pulmonary edema, inflammation and fibrosis. Elevated levels of ROS due to pulmonary insults have been linked to the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 during the initial stages [116]. Transforming growth factor β1 has been implicated in the differentiation of myofibroblasts from fibroblasts, excessive formation of myofibroblasts results in the elevated synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins in the lungs [117]. Transforming growth factor β has also been reported to stimulate ROS generation via Smad 2/3 and MAPK signaling activation [118]. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key element in pulmonary fibrosis and its activation results in autophagy and decreased levels of collagen and ECM. Inhibition of AMPK activation by TGF-β results in mitochondrial dysfunction, which upregulates mitochondrial ROS formation to induce epithelial cell injury [119].

Hesperidin downregulates the TGF-β1/Smad3/AMPK and NF-κB pathways, resulting in improved regulation of oxido-inflammatory markers (such as Nrf2 and HO-1) and proinflammatory markers (such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and reduced collagen deposition during pulmonary fibrosis [120]. In a mouse model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, hesperidin downregulated the IL-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway, resulting in upregulation of P53, p21 and p16 (myofibroblast markers). Additionally, hesperidin downregulated α-SMA, reduced the number of aging-related β-galactosidase-positive cells, prevented lung fibroblast aging and ameliorated pulmonary fibrosis [121].

The anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-cancer properties of Hsd and Hst suggest their potential clinical application in the treatment of respiratory diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis.

4.5. Digestive diseases

Hesperidin has numerous health benefits, including protection against digestive system diseases. Extracellular matrix can accumulate and form fibrotic tissue in response to chronic liver injury, leading to cirrhosis and liver failure in severe cases. Activated hepatic stellate cells (AHSC), a subset of α-SMA-positive liver fibroblasts, contribute to ECM formation during fibrosis. The activation of AHSCs is triggered by liver inflammation, which in turn leads to fibrosis [122,123]. Chronic inflammation and extracellular matrix accumulation cause liver parenchyma fibrosis and ultimately result in scar tissue formation [124,125]. Liver macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines and fibrotic mediators that activate dormant HSCs and transform them into myofibroblasts [126,127].

Hesperidin has demonstrated antifibrotic effects in various models of liver fibrosis, including a rat model of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and primary HSCs. In a mouse hepatic fibrosis model, hesperidin upregulated tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) and suppressed the primary hepatic macrophage inflammatory response. The antifibrotic action of hesperidin is associated with Hedgehog signaling [18] and it protects human hepatocytes against tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBuOOH)-induced oxidative damage [128]. Hesperidin also mitigated hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced hepatic L02 cell injury by upregulating HO-1 [39].

Additionally, hesperidin upregulates the ROS-activated mitochondrial pathway, thereby inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis of stomach cancer cells [129]. Moreover, hesperidin promotes apoptosis in the HT-29 colon cancer cell line via a Bax-dependent mitochondrial mechanism involving oxidant/antioxidant dysregulation [130].

4.6. Urinary tract diseases

Emerging evidence suggests that proinflammatory cytokine release (specifically TNF-α) [131], infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and leukocytes [132] and mitochondrial dysfunction [133] are implicated in the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury. Additionally, nephrotoxic drugs induce renal tissue necrosis and apoptosis by activating caspase-3, a key player in the execution phase of apoptosis [134].

Hesperidin has demonstrated a range of potential therapeutic effects in acute renal injury, including reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and DNA damage [135]. In addition, hesperidin and chrysin attenuated myxin-induced nephrotoxicity [136]. Hesperidin has also been shown to protect rats against acrylamide-induced nephrotoxicity, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and DNA damage [137]. Hesperidin modulates MMP-9 expression and apoptosis and protects against Al-induced kidney damage in rats [138] and acute As-induced liver and kidney injury in mice [139]. Transforming growth factor β1 upregulation in hypertensive rats is associated with endothelial dysfunction and remodeling. Transforming growth factor β-stimulated pericyte myofibroblast differentiation and proliferation induces kidney damage and fibrosis. Hesperidin significantly reduces serum ACE and plasma TGF-β1 activity and downregulates renal angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1) [138]. Thus, hesperidin prevents L-NAME-induced hypertension, vascular and renal dysfunction, renal artery remodeling, glomerular ECM accumulation and renal fibrosis.

5. Conclusion

Oxidative stress and inflammatory response are interconnected and interact with each other. Oxidative stress triggers inflammation, which in turn increases the production of ROS, thereby exacerbating oxidative damage. Hesperidin and hesperetin enhance cellular antioxidant defense by eliminating free radicals and ROS. Additionally, Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit the Txnip/NLRP3, MAPK and NF-κB inflammatory pathways, their upregulates HO-1 expression, inhibits the activation of Txnip and its binding to NLRP3 and impedes the binding of NLRP3 to downstream caspase-1 and ASC, thereby inhibiting inflammatory body activation and downregulating IL-1β levels. The Tumor Suppressor Protein (P53) pathway, cellular energy levels and ratio of anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic proteins determine cell cycle arrest or apoptosis following DNA damage and/or mitochondrial dysfunction. Hesperidin and hesperetin inhibit the G1/S transition in cancer cells through p53. Recent studies have shown that hesperidin and hesperetin exhibits antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal and antiparasitic activities. Although their exact mechanism of action is not fully understood, several mechanisms have been proposed, such as activation of the host immune system, disruption of bacterial membranes and interference with microbial enzymes.

Hesperidin and hesperetin are of natural origin, low toxicity, easy to obtain, and have good prospects for development and utilization in the future. However, due to the poor solubility of Hsd and its susceptibility to hydrolysis by gastric acid and enzymes, the bioavailability is low. Hesperetin is more stable than Hesperidin and has a higher bioavailability, but it is easily metabolized in the body, making it difficult to maintain a higher blood concentration, therefore, it is a major focus to carry out a certain amount of chemical modification of Hsd and Hst to find a synthetic product with a good pharmacological efficacy and a high degree of bioavailability. In addition, in clinical studies, factors affecting the efficacy of flavonoids include the dose of flavonoid metabolites used, the patient population, and the duration of the study. In previous studies, we can note the lack of sufficient clinical information on the therapeutic effects of Hsd and Hst. Therefore, further clinical studies exploring the appropriate dose, bioavailability, efficacy and safety of Hsd and its metabolites are still needed.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the study on Hesperidin on Fibrosis of Frozen Shoulder Inflammation and Mechanism Research (KD2023KYJJ033) by the Kanda College of Nanjing Medical University Research and Development Fund for Natural Science General Programs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhongkai Ji: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Wei Deng: Data curation. Dong Chen: Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhidong Liu: Data curation. Yucheng Shen: Conceptualization. Jiuming Dai: Data curation. Hai Zhou: Data curation. Miao Zhang: Data curation. Hucheng Xu: Data curation. Bin Dai: Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their constructive comments, which improved the presentation of this article. The authors acknowledge the Bullet Edits Limited for lan-guage editing.

References

- 1.Roberts C.K., Hevener A.L., Barnard R.J. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: underlying causes and modification by exercise training. Compr. Physiol. 2013;3(1):1–58. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peluso I., Romanelli L., Palmery M. Interactions between prebiotics, probiotics, polyunsaturated fatty aci ds and polyphenols: diet or supplementation for metabolic syndrome pre vention? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014;65(3):259–267. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2014.880670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asrih M., Jornayvaz F.R. Metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: is insulin re sistance the link? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;418(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alissa E.M., Ferns G.A. Dietary fruits and vegetables and cardiovascular diseases risk. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57(9):1950–1962. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1040487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahleova H., et al. Dietary patterns and Cardiometabolic outcomes in Diabetes: a summary o f Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2209. doi: 10.3390/nu11092209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson G. The role of polyphenols in modern nutrition. Nutr. Bull. 2017;42(3):226–235. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Rio, D., et al., Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxidants Redox Signal.. 18(14): p. 1818-1892.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Buscemi S., et al. Effects of red orange juice intake on endothelial function and inflammatory markers in adult subjects with increased cardiovascular risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;95(5):1089–1095. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefano, R., et al., Citrus polyphenol hesperidin stimulates production of nitric oxide in endothelial cells while improving endothelial function and reducing inflammatory markers in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.. 96(5): p. 782-792.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sthijns M.M.J.P.E., Van B.C.A., Lapointe V.L.S. Redox regulation in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering: the paradox of oxygen. Journal of Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine. 2018;12(10):2013–2020. doi: 10.1002/term.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlund I., et al. Plasma kinetics and urinary excretion of the flavanones naringenin and hesperetin in humans after ingestion of orange juice and grapefruit j uice. J. Nutr. 2001;131(2):235–241. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil-Izquierdo A., et al. In vitro availability of flavonoids and other phenolics in orange juic e. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49(2):1035–1041. doi: 10.1021/jf0000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanaze F.I., et al. Pharmacokinetics of the citrus flavanone aglycones hesperetin and nari ngenin after single oral administration in human subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;61(4):472–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manach C., et al. Bioavailability in humans of the flavanones hesperidin and narirutin a fter the ingestion of two doses of orange juice. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;57(2):235–242. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross J.A., Kasum C.M. Dietary flavonoids: bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002;22:19–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen I.L.F., et al. Bioavailability is improved by enzymatic modification of the citrus fl avonoid hesperidin in humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover tr ial. J. Nutr. 2006;136(2):404–408. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piñuel L., et al. Production of hesperetin using a covalently multipoint immobilized dig lycosidase from Acremonium sp. DSM24697. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;23(6):410–417. doi: 10.1159/000353208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X., et al. Hesperetin derivative attenuates CCl4-induced hepatic fibro sis and inflammation by Gli-1-dependent mechanisms. Int. Immunopharm. 2019;76 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang A.-L., et al. Design, synthesis and investigation of potential anti-inflammatory act ivity of O-alkyl and O-benzyl hesperetin derivatives. Int. Immunopharm. 2018;61:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J.-J., et al. Hesperetin derivative-16 attenuates CCl4-induced inflammati on and liver fibrosis by activating AMPK/SIRT3 pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022;915 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada M., et al. Bioavailability of glucosyl hesperidin in rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70(6):1386–1394. doi: 10.1271/bbb.50657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishikawa S., et al. α-Monoglucosyl hesperidin but not hesperidin induces Brown-like adipoc yte formation and suppresses white adipose tissue accumulation in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(7):1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walle T. Methylation of dietary flavones greatly improves their hepatic metabol ic stability and intestinal absorption. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4(6):826–832. doi: 10.1021/mp700071d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allaert F.A., et al. Correlation between improvement in functional signs and plethysmograph ic parameters during venoactive treatment (Cyclo 3 Fort) Int. Angiol. : a journal of the International Union of Angi ology. 2011;30(3):272–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guex J.J., et al. Quality of life improvement in Latin American patients suffering from chronic venous disorder using a combination of Ruscus aculeatus and he speridin methyl-chalcone and ascorbic acid (quality study) Int. Angiol. : a journal of the International Union of Angi ology. 2010;29(6):525–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasquel-Oliveira F.S., et al. Hesperidin methyl chalcone interacts with NFκB Ser276 and inhibits zym osan-induced joint pain and inflammation, and RAW 264.7 macrophage act ivation. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28(4):979–992. doi: 10.1007/s10787-020-00686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez R.M., et al. Topical formulation containing hesperidin methyl chalcone inhibits ski n oxidative stress and inflammation induced by ultraviolet B irradiati on. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. : Official journal of the Eur opean Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobio logy. 2016;15(4):554–563. doi: 10.1039/c5pp00467e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guazelli C.F.S., et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of hesperidin methyl chalcon e in experimental ulcerative colitis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021;333 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu S., et al. Hesperidin methyl chalcone ameliorates lipid metabolic disorders by ac tivating lipase activity and increasing energy metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2023;1869(2) doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H.-Y., et al. Enzymatic modification enhances the protective activity of citrus flav onoids against alcohol-induced liver disease. Food Chem. 2013;139(1–4):231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morsy M.A., Nair A.B. Prevention of rat liver fibrosis by selective targeting of hepatic ste llate cells using hesperidin carriers. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;552(1–2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg A., et al. Biological activity assessment of a novel contraceptive antimicrobial agent. J. Androl. 2005;26(3):414–421. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.04181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iranshahi M., et al. Protective effects of flavonoids against microbes and toxins: the case s of hesperidin and hesperetin. Life Sci. 2015;137:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg A., et al. Chemistry and pharmacology of the Citrus bioflavonoid hesperidin. Phytother Res. : PTR. 2001;15(8):655–669. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J.Y., et al. Hesperetin: a potent antioxidant against peroxynitrite. Free Radic. Res. 2004;38(7):761–769. doi: 10.1080/10715760410001713844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilmsen P.K., Spada D.S., Salvador M. Antioxidant activity of the flavonoid hesperidin in chemical and biolo gical systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53(12):4757–4761. doi: 10.1021/jf0502000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elavarasan J., et al. Hesperidin-mediated expression of Nrf2 and upregulation of antioxidant status in senescent rat heart. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012;64(10):1472–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez M.C., et al. Hesperidin, a flavonoid glycoside with sedative effect, decreases brai n pERK1/2 levels in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2009;92(2):291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen M.-C., et al. Hesperidin upregulates heme oxygenase-1 to attenuate hydrogen peroxide -induced cell damage in hepatic L02 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58(6):3330–3335. doi: 10.1021/jf904549s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, Y., et al., Curcumin attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in the hippocampus by supp ression of ER stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a manner dependent on AMPK. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.. 286(1): p. 53-63.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Han Y., et al. Corrigendum to 'Reactive oxygen species promote tubular injury in diab etic nephropathy: the role of the mitochondrial ros-txnip-nlrp3 biolog ical axis' [Redox Biology. Redox Biol. 2018;16:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.02.013. 24: p. 101216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Javed, H., et al., Effect of hesperidin on neurobehavioral, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and lipid alteration in intracerebroventricular streptozotocin induced cognitive impairment in mice. J. Neurol. Sci.. 348(1–2): p. 51-59.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Kang S.R., et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of flavonoids isolated from Korea Citrus aurantium L. on lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells by blocking of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways. Food Chem. 2011;129(4):1721–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minami T., Aird W.C. Endothelial cell gene regulation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2005;15(5):174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nizamutdinova, I.T., et al., Hesperidin, hesperidin methyl chalone and phellopterin from Poncirus t rifoliata (Rutaceae) differentially regulate the expression of adhesio n molecules in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. Immunopharm.. 8(5): p. 670-678.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Kim S.-J., Lee S.-M. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in D-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharid e-induced acute liver failure: role of heme oxygenase-1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;65:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C.-Y., et al. Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome and mitigates Alzhei mer's-like pathology via Nrf2-TXNIP-TrX Axis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2019;30(11):1411–1431. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou Y., et al. Nrf2 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulating Trx1/TX NIP complex in cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Behav. Brain Res. 2018;336:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee K.-H., et al. The inhibitory effect of hesperidin on tumor cell invasiveness occurs via suppression of activator protein 1 and nuclear factor-kappaB in hu man hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2010;194(1–2):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nazari M., et al. Inactivation of nuclear factor-κB by citrus flavanone hesperidin contr ibutes to apoptosis and chemo-sensitizing effect in Ramos cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;650(2–3):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pérez-Vargas J.E., et al. Hesperidin prevents liver fibrosis in rats by decreasing the expressio n of nuclear factor-κB, transforming growth factor-β and connective ti ssue growth factor. Pharmacology. 2014;94(1–2):80–89. doi: 10.1159/000366206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee H.J., et al. The flavonoid hesperidin exerts anti-photoaging effect by downregulati ng matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression via mitogen activated p rotein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling pathways. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2018;18(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmadi, A., et al., The role of hesperidin in cell signal transduction pathway for the pre vention or treatment of cancer. Curr. Med. Chem.. 22(30): p. 3462-3471.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Badal, S. and R. Delgoda, Role of the modulation of CYP1A1 expression and activity in chemopreve ntion. J. Appl. Toxicol. : JAT. 34(7): p. 743-753.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Choi, E.J., Hesperetin induced G1-phase cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer M. Nutr. Cancer. 59(1): p. 115-119.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Redza-Dutordoir M., Averill-Bates D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863(12):2977–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghorbani A., et al. The citrus flavonoid hesperidin induces p53 and inhibits NF-κB activat ion in order to trigger apoptosis in NALM-6 cells: involvement of PPAR γ-dependent mechanism. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012;51(1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xia R., et al. Hesperidin induces apoptosis and G0/G1 arrest in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;41(1):464–472. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saiprasad G., et al. Hesperidin induces apoptosis and triggers autophagic markers through i nhibition of Aurora-A mediated phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin and glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta signalling ca scades in experimental colon carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50(14):2489–2507. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.013. Oxford, England : 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alshatwi A.A., et al. The apoptotic effect of hesperetin on human cervical cancer cells is m ediated through cell cycle arrest, death receptor, and mitochondrial p athways. Fund. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;27(6):581–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2012.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi E.J., Kim G.-H. Anti-/pro-apoptotic effects of hesperetin against 7,12-dimetylbenz(a)a nthracene-induced alteration in animals. Oncol. Rep. 2011;25(2):545–550. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Badal S., Delgoda R. Role of the modulation of CYP1A1 expression and activity in chemopreve ntion. J. Appl. Toxicol. : JAT. 2014;34(7):743–753. doi: 10.1002/jat.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu D., et al. Hesperetin inhibits Eca-109 cell proliferation and invasion by suppres sing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and synergistically enhances the a nti-tumor effect of 5-fluorouracil on esophageal cancer <i>in vitro</i > and <i>in vivo</i >. RSC Adv. 2018;8(43):24434–24443. doi: 10.1039/c8ra00956b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi E.J. Hesperetin induced G1-phase cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer M. Nutr. Cancer. 2007;59(1):115–119. doi: 10.1080/01635580701419030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., et al. Hesperidin inhibits HeLa cell proliferation through apoptosis mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways and cell cycle arrest. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:682. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palit S., et al. Hesperetin induces apoptosis in breast carcinoma by triggering accumul ation of ROS and activation of ASK1/JNK pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015;230(8):1729–1739. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smina T.P., et al. Hesperetin exerts apoptotic effect on A431 skin carcinoma cells by reg ulating mitogen activated protein kinases and cyclins. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2015;61(6):92–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xue X.F., et al. 2012. In Vitro Detections of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Porcine β-defensins; pp. 1291–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cushnie T.P.T., Lamb A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;26(5):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Havsteen B.H. The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2002;96(2–3):67–202. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cvetnić Z., Vladimir-Knezević S. Antimicrobial activity of grapefruit seed and pulp ethanolic extract. Acta pharmaceutica (Zagreb, Croatia) 2004;54(3):243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daglia M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawaguchi K., et al. A citrus flavonoid hesperidin suppresses infection-induced endotoxin s hock in mice. Biol. Pharmaceut. Bull. 2004;27(5):679–683. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee Y.-S., et al. Enzymatic bioconversion of citrus hesperidin by Aspergillus sojae nari nginase: enhanced solubility of hesperetin-7-O-glucoside with in vitro inhibition of human intestinal maltase, HMG-CoA reductase, and growth of Helicobacter pylori. Food Chem. 2012;135(4):2253–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mandalari G., et al. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids extracted from bergamot (Citrus b ergamia Risso) peel, a byproduct of the essential oil industry. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007;103(6):2056–2064. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zeng H.-J., et al. Molecular interactions of flavonoids to hyaluronidase: insights from S pectroscopic and molecular modeling studies. J. Fluoresc. 2015;25(4):941–959. doi: 10.1007/s10895-015-1576-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krolicki Z., Lamer-Zarawska E.J.H.P. 1984. Investigation of Antifungal Effect of Flavonoids. 1 [hesperidin, Naringin, Phellodendroside, Luteolin-7-Glucoside, Hipotethin-7-Glucoside, Quecetin, Celastroside, Amentoflavone; Botrytis Cinerea, Trichoderma Glaucum, Aspergillus fumigatus] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Islam S.K.N., Ahsan M.J.P.R. 1997. Biological Activities of the Secondary Metabolites Isolated from Zieria Smithii and Zanthoxylum Elephantiasis on Microorganisms and Brine Shrimps. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang Y., et al. Exploring the potential pharmacological mechanism of hesperidin and Gl ucosyl hesperidin against COVID-19 based on bioinformatics analyses an d antiviral assays. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022;50(2):351–369. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X22500148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lin C.-W., et al. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica ro ot and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir. Res. 2005;68(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basu A., Sarkar A., Maulik U. Molecular docking study of potential phytochemicals and their effects on the complex of SARS-CoV2 spike protein and human ACE2. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bellavite P., Donzelli A. Hesperidin and SARS-CoV-2: new light on the healthy function of citrus fruits. Antioxidants. 2020;9(8):742. doi: 10.3390/antiox9080742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haggag Y.A., El-Ashmawy N.E., Okasha K.M. Is hesperidin essential for prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 Infe ction? Med. Hypotheses. 2020;144 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu C., et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potent ial drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10(5):766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joshi R.S., et al. Discovery of potential multi-target-directed ligands by targeting host -specific SARS-CoV-2 structurally conserved main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2021;39(9):3099–3114. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1760137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wacker A., Eilmes H.G. Antiviral activity of plant components. 1st communication: flavonoids (author's transl) Arzneim.-Forsch. 1978;28(3):347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsai F.-J., et al. Kaempferol inhibits enterovirus 71 replication and internal ribosome e ntry site (IRES) activity through FUBP and HNRP proteins. Food Chem. 2011;128(2):312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Allam G., Abuelsaad A.S.A. In vitro and in vivo effects of hesperidin treatment on adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. J. Helminthol. 2014;88(3):362–370. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X13000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wacker, A. and H.G. Eilmes, Antiviral activity of plant components. 1st communication: flavonoids (author's transl). Arzneim. Forsch. 28(3): p. 347-350.. [PubMed]

- 90.Allam, G. and A.S.A. Abuelsaad, In vitro and in vivo effects of hesperidin treatment on adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. J. Helminthol.. 88(3): p. 362-370.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Gonzalez-Rey, E., et al., Cortistatin, an antiinflammatory peptide with therapeutic action in in flammatory bowel disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States O F America. vol. 103(11): p. 4228-4233.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Hosseinzadeh, A., et al., Apoptosis signaling pathways in osteoarthritis and possible protective role of melatonin. J. Pineal Res.. 61(4): p. 411-425.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Saklatvala, J., Tumour necrosis factor alpha stimulates resorption and inhibits synthe sis of proteoglycan in cartilage. Nature. 322(6079): p. 547-549.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Zhao, Y.-P., et al., Progranulin protects against osteoarthritis through interacting with T. Ann. Rheum. Dis.. 74(12): p. 2244-2253.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Hayden, M.S. and S. Ghosh, Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin. Immunol.. 26(3): p. 253-266.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Liu, H., et al., Hesperetin suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced bone loss. J. Cell. Physiol.. 234(7): p. 11009-11022.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Frantz, S., et al., Left ventricular remodelling post-myocardial infarction: pathophysiolo gy, imaging, and novel therapies. Eur. Heart J.. 43(27): p. 2549-2561.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Yu H.Y., et al. Preventive effect of yuzu and hesperidin on left ventricular remodelin g and dysfunction in rat permanent left anterior descending coronary a rtery occlusion model. PLoS One. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maneesai P., et al. Hesperidin prevents nitric oxide deficiency-induced cardiovascular rem odeling in rats via suppressing TGF-β1 and MMPs protein expression. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1549. doi: 10.3390/nu10101549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun Y.-Z., et al. Anti-atherosclerotic effect of hesperidin in LDLr -/-mice a nd its possible mechanism. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017;815:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cheignon, C., et al., Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer's disease. Redox Biol.. 14: p. 450-464.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Frost, G.R. and Y.-M. Li, The role of astrocytes in amyloid production and Alzheimer's disease. Open biology. 7(12): p. 170228.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Dwivedi, S., et al., Sulforaphane ameliorates okadaic acid-induced memory impairment in rat s by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway. Mol. Neurobiol.. 53(8): p. 5310-5323.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. and A.Y. Abramov, The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 88(Pt B): p. 179-188.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Ding, Y., et al., Posttreatment with 11-Keto-β-Boswellic acid ameliorates cerebral Ische mia-reperfusion injury: Nrf2/HO-1 pathway as a potential mechanism. Mol. Neurobiol.. 52(3): p. 1430-1439.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.Cameron, B. and G.E. Landreth, Inflammation, microglia, and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Dis.. 37(3): p. 503-509.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.Yamamoto, M. and K. Takeda, Current views of toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2010: p. 240365.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Hanke M.L., Kielian T. Toll-like receptors in health and disease in the brain: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clinical science (London, England. 1979;121(9):367–387. doi: 10.1042/CS20110164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Frank, S., et al., Differential regulation of toll-like receptor mRNAs in amyloid plaque- associated brain tissue of aged APP23 transgenic mice. Neurosci. Lett.. 453(1): p. 41-44.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Jin, J.-J., et al., Toll-like receptor 4-dependent upregulation of cytokines in a transgen ic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 5: p. 23.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Olson J.K., Miller S.D. Microglia initiate central nervous system innate and adaptive immune r esponses through multiple TLRs. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. 1950;173(6):3916–3924. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Michaud, J.-P., et al., Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation with the detoxified ligand monophosph oryl lipid A improves Alzheimer's disease-related pathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States O F America. vol. 110(5): p. 1941-1946.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Liu S., et al. TLR2 is a primary receptor for Alzheimer's amyloid β peptide to trigge r neuroinflammatory activation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. 1950;188(3):1098–1107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ikram, M., et al., Hesperetin confers neuroprotection by regulating Nrf2/TLR4/NF-κB Signa ling in an Aβ mouse model. Mol. Neurobiol.. 56(9): p. 6293-6309.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 115.Della Latta, V., et al., Bleomycin in the setting of lung fibrosis induction: from biological m echanisms to counteractions. Pharmacol. Res.. 97: p. 122-130.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Kandhare, A.D., et al., Effect of glycosides based standardized fenugreek seed extract in bleo mycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats: decisive role of Bax, Nrf2. Chem. Biol. Interact.. 237: p. 151-165.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Fernandez, I.E. and O. Eickelberg, The impact of TGF-β on lung fibrosis: from targeting to biomarkers. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. vol. 9(3): p. 111-116.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 118.Saito, A., et al., The role of TGF-β signaling in lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 19(11): p. 3611.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 119.Rangarajan, S., et al., Metformin reverses established lung fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Nat. Med.. 24(8): p. 1121-1127.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 120.Zhou Z., et al. Hesperidin ameliorates bleomycin-induced experimental pulmonary fibros is via inhibition of TGF-beta1/Smad3/AMPK and IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB p athways. EXCLI journal. 2019;18:723–745. doi: 10.17179/excli2019-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Han D., et al. Hesperidin inhibits lung fibroblast senescence via IL-6/STAT3 signalin g pathway to suppress pulmonary fibrosis. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmac ology. 2023;112 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lan T., et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 promotes liver fibrosis by preventing miR-19b-3p- mediated inhibition of CCR2. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 2018;68(3):1070–1086. doi: 10.1002/hep.29885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wree A., et al. NLRP3 inflammasome driven liver injury and fibrosis: roles of IL-17 an d TNF in mice. Hepatology. 2018;67(2):736–749. doi: 10.1002/hep.29523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schuppan D., et al. Matrix as a modulator of hepatic fibrogenesis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2001;21(3):351–372. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Böttcher K., et al. MAIT cells are chronically activated in patients with autoimmune liver disease and promote profibrogenic hepatic stellate cell activation. Hepatology. 2018;68(1):172–186. doi: 10.1002/hep.29782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mederacke I., et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors t o liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pradere J.-P., et al. Hepatic macrophages but not dendritic cells contribute to liver fibros is by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells in mi ce. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 2013;58(4):1461–1473. doi: 10.1002/hep.26429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chen M., et al. Protective effects of hesperidin against oxidative stress of tert-buty l hydroperoxide in human hepatocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 2010;48(10):2980–2987. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jixiang, et al. 2015. Hesperetin Induces the Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells via Activating Mitochondrial Pathway by Increasing Reactive Oxygen Species. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sivagami G., et al. Corrigendum to "Role of hesperetin (a natural flavonoid) and its analogue on apoptosis in HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line – a comparative study". Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;58:552–553. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.11.038. 50 (2012) 660–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ramesh, G. and W.B. Reeves, Salicylate reduces cisplatin nephrotoxicity by inhibition of tumor nec rosis factor-alpha. Kidney Int.. 65(2): p. 490-499.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 132.Faubel, S., et al., Cisplatin-induced acute renal failure is associated with an increase i n the cytokines interleukin (IL)-1beta, IL-18, IL-6, and neutrophil in filtration in the kidney. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut.. 322(1): p. 8-15.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 133.Rodrigues, M.A.C., et al., Carvedilol protects against the renal mitochondrial toxicity induced b y cisplatin in rats. Mitochondrion. 10(1): p. 46-53.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 134.Miller, R.P., et al., Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins. 2(11): p. 2490-2518.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 135.Sahu B.D., et al. Hesperidin attenuates cisplatin-induced acute renal injury by decreasing oxidative stress. inflammation and DNA damage. 2013;20(5):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hanedan B., et al. vol. 108. 2018. pp. 1607–1616. (Investigation of the Effects of Hesperidin and Chrysin on Renal Injury Induced by Colistin in Rats). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Elhelaly A.E., et al. Protective effects of hesperidin and diosmin against acrylamide-induced liver. kidney, and brain oxidative damage in rats. 2019;26(34):35151–35162. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hassan N.H., et al. Hesperidin protects against aluminum-induced renal injury in rats via modulating MMP-9 and apoptosis: biochemical. histological, and ultrastructural study. 2022;30(13):36208–36227. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24800-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ricardo P., et al. Protective Activity of Hesperidin and Lipoic Acid Against Sodium Arsenite Acute Toxicity in Mice. 2004;32(5):527–535. doi: 10.1080/01926230490502566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Umar S., et al. Hesperidin inhibits collagen-induced arthritis possibly through suppre ssion of free radical load and reduction in neutrophil activation and infiltration. Rheumatol. Int. 2013;33(3):657–663. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang Q., et al. Hesperetin prevents bone resorption by inhibiting RANKL-induced Osteoc lastogenesis and Jnk mediated Irf-3/c-Jun activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1028. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Trzeciakiewicz A., et al. Hesperetin stimulates differentiation of primary rat osteoblasts invol ving the BMP signalling pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010;21(5):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ahmadi A., et al. Chemoprotective effects of hesperidin against genotoxicity induced by cyclophosphamide in mice bone marrow cells. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2008;31(6):794–797. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rizza S., et al. Citrus polyphenol hesperidin stimulates production of nitric oxide in endothelial cells while improving endothelial function and reducing in flammatory markers in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2011;96(5):E782–E792. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yang Z., et al. Hesperetin attenuates mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in lipopolysacc haride-induced H9C2 cardiomyocytes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;9(5):1941–1946. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Gandhi C., Upaganalawar A., Balaraman R. Protection against in vivo focal myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injur y-induced arrhythmias and apoptosis by hesperidin. Free Radic. Res. 2009;43(9):817–827. doi: 10.1080/10715760903071656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wang X., et al. Effects of hesperidin on the progression of hypercholesterolemia and f atty liver induced by high-cholesterol diet in rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;117(3):129–138. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11097fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hong Y., An Z. Hesperidin attenuates learning and memory deficits in APP/PS1 mice thr ough activation of Akt/Nrf2 signaling and inhibition of RAGE/NF-κB sig naling. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2018;41(6):655–663. doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0662-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhu X., et al. The antidepressant-like effects of hesperidin in streptozotocin-induce d Diabetic rats by activating Nrf2/ARE/Glyoxalase 1 pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1325. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.de Souza A.B.F., et al. Effects in vitro and in vivo of hesperidin administration in an experi mental model of acute lung inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022;180:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ye J., et al. Protective effects of hesperetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute l ung injury by targeting MD2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019;852:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wang N., et al. Hesperetin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice through regulating the TLR4-MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathway. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2019;42(12):1063–1070. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Liu X.-x., et al. Hesperidin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by inhibiting HMGB1 release. Int. Immunopharm. 2015;25(2):370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]