Abstract

Introduction

A systematic literature review (SLR) and network meta-analysis (NMA) were conducted to evaluate the comparative efficacy, durability and safety of faricimab, used in a Treat & Extend (T&E) regime with intervals up to every 16 weeks (Q16W), relative to other therapies currently in use for treatment of diabetic macular oedema (DME). Of particular interest were anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies applied in flexible dosing regimens such as Pro re nata (PRN) and T&E, which are the mainstay in clinical practice.

Methods

An SLR identifying randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published before August 2021 was conducted, followed by a Bayesian NMA comparing faricimab T&E treatment to aflibercept, ranibizumab, bevacizumab, dexamethasone and laser therapy. Outcomes included in the analysis were change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), change in central subfield thickness (CST), injection frequency, ocular adverse events (AE) and all-cause discontinuation, all of which were evaluated at 12 months. Subgroup analyses including patients’ naïve to anti-VEGF were conducted where feasible.

Results

Twenty-six studies identified in the SLR were included in the NMA. Most importantly for decision making in clinical practise, faricimab T&E was associated with a statistically greater (95% credible intervals exclude zero) and clinically meaningful decrease in retinal thickness compared to all other flexible dosing regimens (greater retinal drying by 55–125 microns). Anatomical outcomes determine treatment efficacy and retreatment of patients. The NMA also showed a statistically greater increase in mean change in BCVA for faricimab T&E vs. flexible regimens using ranibizumab and bevacizumab (increase of 4.4–4.8 letters) as well as a numerical improvement vs. aflibercept PRN (two letters, 95% credible intervals including zero). Accordingly, the injection frequency was numerically lower versus other treatments using flexible dosing regimens (decrease by 0.92–1.43 injections). The analyses also indicated that the safety profile of faricimab T&E was comparable to those of ranibizumab and aflibercept, which have well-established safety profiles, with similar results for the number of all-cause discontinuations.

Conclusion

Faricimab provides a new treatment option in DME with dual-pathway inhibition of VEGF and angiopoeitin-2 (Ang-2). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first indirect comparison of faricimab T&E in DME. The analyses indicate that faricimab T&E is associated with superior retinal drying along with numerically fewer injections compared to all other treatments given in flexible dosing regimens. It also showed superior visual acuity outcomes compared to ranibizumab and bevacizumab.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02675-y.

Keywords: Comparative efficacy, Diabetic macular oedema, Durability, Faricimab, Network meta-analysis, Safety, Systematic literature review

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The current standard of care (SoC) options for treatment of diabetic macular oedema (DME) are anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections (IVT) such as ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab (not licensed) used in flexible treatment regimens such as Pro re nata (PRN) and Treat & Extend (T&E) |

| We conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare the efficacy and safety of faricimab to other therapies typically in use for treatment of DME |

| Network meta-analyses (NMA) allow treatments that are not compared directly within randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to be compared indirectly |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Faricimab T&E is associated with superior or comparable visual outcomes in terms of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and superior anatomical outcomes in terms of decreasing retinal thickness against all other treatments given in flexible dosing regimens, which are the standard of care in clinical practise, whilst offering a low treatment burden |

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a global epidemic, and its prevalence is expected to increase from 463 million in 2019 to 700 million in 2045 [1]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of diabetes that can lead to vision loss and blindness and is one of the leading causes of vision impairment in the working age population [2, 3]. Diabetic macular oedema (DME) is a serious manifestation of DR characterised by exudative fluid accumulation in the macular and is the primary cause of central vision loss among patients with DR [4, 5]. Around 7% of patients with diabetes are affected by DME, and risk of DME increases with severity of DR [6].

Intravitreal injections (IVT) of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents such as ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab (not licensed for ophthalmic use) represent the preferred treatment for DME [7]. These treatments have replaced IVT corticosteroids and laser photocoagulation as the current standard of care for patients with DME [8]. However, real-world outcomes following anti-VEGF therapy for DME lag behind those noted in clinical trials [9]. The need for frequent treatment visits has been associated with non-adherence to anti-VEGF treatment and subsequently worsening visual outcomes [10].

Faricimab is a novel dual-pathway inhibitor of VEGF-A and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), which is thought to promote vascular stability and reduce inflammation [11]. In two pivotal phase III trials, YOSEMITE and RHINE, after the loading phase faricimab T&E was applied in a personalized treat-and-extend- based regimen (T&E). Intervals were extended by 4 weeks up to every 16 weeks (Q16W), maintained or reduced by 4 or 8 weeks (as low as Q4W) based on prespecified central subfield thickness (CST) and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) criteria. Faricimab T&E demonstrated non-inferiority to aflibercept given every 8 weeks (Q8W) in the primary endpoint of change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 12 months in the treatment of DME. Faricimab T&E also demonstrated greater improvement for anatomical outcomes, i.e. reduction in CST, absence of intraretinal fluid (IRF) and absence of DME [12].

YOSEMITE and RHINE provide insight into the efficacy and safety of faricimab T&E relative to aflibercept Q8W. However, indirect comparisons of faricimab T&E with other treatments and particularly flexible dosing regimens such as T&E and Pro re nata (PRN) are needed, given that these are typically used in clinical practise. The objective of this study was to estimate the relative treatment effects of faricimab and other therapies that are currently in use for treatment of DME, based on available evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCT). Network meta-analyses (NMA) allow treatments that are not compared directly within RCTs to be compared indirectly.

Methods

Search Strategy

A systematic literature review (SLR) of RCTs investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments for DME was conducted using electronic databases including Embase, MEDLINE, DARE and the Cochrane library, as well hand-searching supplementary sources including conference proceedings between January 2017 and August 2021, HTA agency websites, clinical trial registries, key government/international bodies, reference lists of included publications and related SLRs. The electronic sources were last searched on August 19, 2021, and the following treatments were included in the search strategy: faricimab, ranibizumab, brolucizumab, aflibercept, bevacizumab, dexamethasone intravitreal implants, laser therapy and placebo/sham. There was no restriction on country of origin or language of publication. Previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses were included for the purpose of bibliographic searches to identify relevant primary studies. The search strategy can be found in the Supplementary Material.

This SLR was conducted in compliance with published guidelines issued by the Cochrane Collaboration, the Centre for Reviews & Dissemination (CRD; York, UK), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13–16]. This study was exempt from ethics approval as it is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Study Population and Selection Criteria

The selection criteria for the NMA are presented in Table 1. Adults with DME were included, and studies investigating patients with diabetic retinopathy without DME or macular oedema not associated with diabetes mellitus were excluded. RCTs of at least 48 weeks or 12 months were included, along with open-label extensions of RCTs up to 24 months. Treatments included only licensed and/or standard doses of faricimab and its comparators. Efficacy outcomes of interest included mean change in BCVA and mean change in CST. The safety outcomes of interest included overall treatment discontinuation/withdrawal and ocular adverse events (AE). The mean number of injections was also evaluated.

Table 1.

PICO framework for the network meta-analysis

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Patients > 18 years old with DME |

| Intervention | Faricimab |

| Comparators |

Licensed and/or standard doses only of Ranibizumab Aflibercept Bevacizumab (not licensed for ophthalmic use) Dexamethasone intravitreal implants Laser therapy Placebo/sham |

| Outcomes |

Time points for all outcomes: 12 months Vision outcomes: Mean change from baseline in BCVA score Anatomic outcomes: Mean change in CST Other: Treatment frequency: Number of injections Overall treatment discontinuation/withdrawal Safety outcomes: Overall ocular AEs rate |

Additional pre-planned outcomes for the NMA included ETDRS letters categories, serious ocular adverse events, serious systemic adverse events and discontinuations due to adverse events. Results for these additional pre-planned outcomes are presented in the supplementary material

AE adverse events, BCVA best-corrected visual acuity, CST central subfield thickness, DME diabetic macular oedema, FA feasibility assessment, MA meta-analysis, NMA network meta-analysis, PICO population, intervention, comparators and outcomes, RCT randomized controlled trial, SLR systematic literature review

Study Screening

Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers, as were the full text articles. Any disputes as to eligibility for inclusion were referred to a third party.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data from included studies were extracted into a predesigned data extraction table (DET) by a single reviewer and quality checked by a second reviewer. Disputes were referred to a third party. Quality and risk of bias were assessed using the seven-criteria checklist provided in Sect. 2.5 of the NICE single technology appraisal user guide [17].

Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Following the identification of relevant studies, a feasibility assessment was conducted to determine whether it was possible and appropriate to conduct network meta-analyses, resulting in a network of studies for each outcome of interest. NMAs enable the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions that have not been directly compared in RCTs. All networks considered monotherapies only (IVT monotherapies for the number of injections outcome). If a study had two arms that were classed as the same treatment node, results from those two arms were pooled using standard meta-analytical methods.

Network meta-analyses were conducted and are presented here for the following outcomes: mean change in BCVA score, mean change in CST, mean number of injections, ocular adverse events and all cause discontinuations. If CST was missing for a study but one or more other anatomical outcomes were reported, the other value was used as a proxy in the following order of preference: central retinal thickness (CRT), central foveal thickness (CFT) or central macular thickness (CMT). Other outcomes analysed presented in the supplemental material were proportion of patients losing or gaining ≥ 10/15 ETDRS letters, serious ocular adverse events, systemic serious adverse events and discontinuations due to adverse events.

The NMAs were conducted under a Bayesian framework using a random effects model as base case. Changes from baseline in BCVA score, CST and number of injections were modelled as normally distributed data, using the arm level mean change from baseline (or for number of injections, the mean number of injections since baseline) as the outcome. All other endpoints were modelled using a binomial likelihood with logit link.

Vague priors were used for all parameters (see Supplementary Material). Sensitivity analyses around model assumptions include a Bayesian fixed-effect model and exclude studies where laser rescue therapy could potentially have influenced the BCVA score. Estimates were calculated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling in R version 3.6.1 and JAGS version 4.3.0 [18, 19]. Three parallel chains were run with at least 40,000 iterations, a burn-in of at least 10,000 and a thinning parameter of at least 10. Convergence was assessed via review of trace plots, posterior density plots, effective sample size and Brooks-Gelman-Rubin statistics, and parameters were increased if necessary to improve convergence. For non-convergence due to rare events, a continuity correction was applied. The deviance information criterion (DIC) was used to compare the relative fit of the models, and models with lower DIC were preferred. Random effect models are used as base case given that the presence of between study heterogeneity is plausible. Differences in DIC < 5 points were not considered meaningful. To assess the absolute fit, the total residual deviance was calculated and compared against the total number of independent data points.

The NMA models for the primary outcome of change in BCVA score were extended by incorporating the following patient characteristics as covariates via meta-regression analyses [20]: BCVA at baseline and CST at baseline. Fixed and exchangeable interaction models were fit using aflibercept as the interaction reference treatment.

Particular subgroups of interest were patients’ naïve to anti-VEGF and experienced with anti-VEGF, but since few studies reported outcomes in the anti-VEGF experienced population, only the anti-VEGF treatment naïve population was evaluated for outcomes with sufficient data and a connected network.

To assess inconsistency of direct and indirect evidence in the Bayesian framework, inconsistency models found in NICE DSU TSD 4 were used [21]. The DIC and residual deviance were used to compare the fit of the standard (consistency) and inconsistency models, with a lower or similar DIC for the standard model indicating a better fit to the data and no evidence of substantial inconsistency.

Output from the NMAs included estimates and 95% credible intervals (CrI), the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and probability that each treatment performs best, along with the probability of non-inferiority using a four-letter threshold following the definition in YOSEMITE and RHINE [12]. Treatments are referred to as statistically different when the 95% credible interval excludes zero for difference outcomes or one for ratio outcomes.

Results

Systematic Literature Review

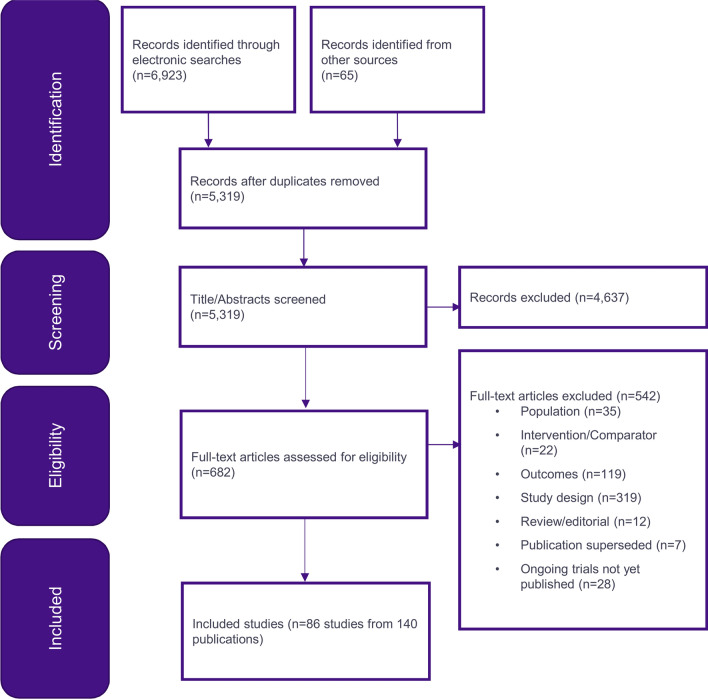

The electronic database search identified 6923 citations in total, and 65 publications were identified through other sources. After removal of duplicates, 5319 citations remained, and after title and abstract screening, 682 full-text publications were assessed for eligibility. In total, 140 publications reporting 86 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in the SLR. Of these, 130 were full publications, 7 were conference abstracts and 3 were trial registry records. The PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1 depicts the process of study identification and selection.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of the studies included in the systematic literature review

After applying the PICOS (population, intervention, comparators, outcomes and study design) criteria for inclusion in the NMA, 26 studies formed a connected network and were considered appropriate for the NMA at 12 months, the details of which can be found in Table 2. Of the 86 studies identified in the SLR, 36 were excluded for treatment-related reasons, 4 were not connected to the faricimab T&E network, 13 were excluded for investigating unlicensed combination regimens and 4 for other reasons. Although identified by the SLR, the RIDE, RISE and Ahmadieh (2008) studies report outcomes at 24 months only and therefore were not included in this report of outcomes at 12 months [22, 23].

Table 2.

Details of the 26 trials included in the network meta-analysis

| Study name | Primary data source: author, year | Time of assessment (period) | Treatments, dose, regimen | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEVORDEX | Gillies, 2014 [22] | 12 and 24 months |

BEV 1.25 mg IVT PRN Q4W DEX 0.7 mg IVT PRN Q16W |

61 (88 eyes) |

| BOLT | Michaelides, 2010 [23] | 12 and 24 months |

LP → BEV 1.25 mg IVT PRN Laser PRN Q16W |

80 |

| Chatzirallis 2020 | Chatzirallis, 2020 [24] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN LP → AFL 2 mg IVT PRN |

112 |

| DA VINCI | Do, 2012 [25] | 12 months |

AFL 0.5 mg IVT Q4W AFL 2 mg IVT Q4W LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W LP → AFL 2 mg IVT PRN Laser PRN |

221 |

| DRCR T | Wells, 2016 [26] | 12 and 24 months |

AFL 2.0 mg IVT PRN Q4W → Laser BEV 1.25 mg IVT PRN Q4W → Laser RAN 0.3 mg IVT PRN Q4W → Laser |

660 |

| Eichenbaum 2018 | Eichenbaum, 2018 [27] | 12 and 24 months |

RAN 0.3 mg IVT Q4W RAN 0.3 mg IVT Q4W → T&E |

20 |

| ETDRS | Anon, 1985 [28] | 12 and 24 months |

Laser PRN Deferred argon laser |

2244 |

| Fouda 2017 | Fouda, 2017 [29] | 12 months |

LP → AFL 2 mg IVT PRN LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN |

42 (70 eyes) |

| LUCIDATE | Comyn, 2014 [30] | 12 months (48 weeks) |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT Q4W Laser PRN Q12W |

37 |

| MEAD 1 | Boyer, 2014 [31] | 12 and 24 months |

DEX 0.7 mg IVT PRN DEX 0.35 mg IVT PRN Placebo |

1048 in MEAD 1 and MEAD 2 |

| MEAD 2 | Boyer, 2014 [31] | 12 and 24 months |

DEX 0.7 mg IVT PRN DEX 0.35 mg IVT PRN Placebo |

1048 in MEAD 1 and MEAD 2 |

| Ozsaygili 2020 | Ozsaygili, 2020 [32] | 12 months |

DEX 0.7 mg IVT (1 dose) → PRN LP → AFL 2 mg IVT PRN |

62 (98 eyes) |

| REACT | Ehlers, 2018 [33] | 12 months |

RAN 0.3 mg IVT Q4W LP → RAN 0.3 mg IVT T&E |

27 |

| REFINE | Li, 2019 [34] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN Laser PRN + Sham IVT |

384 |

| RESOLVE | Massin, 2010 [35] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.3–0.6 mg IVT PRN LP → RAN 0.5—1 mg IVT PRN Sham |

151 |

| RESPOND | Berger, 2015 [36] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT + Prompt Laser PRN Laser PRN |

237 |

| RESTORE | Mitchell, 2011 [37] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT + Prompt Laser PRN Laser PRN Q12W + Sham injection |

345 |

| RETAIN | Prünte, 2016 [38] | 12 and 24 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT + Laser T&E LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT T&E LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN |

372 |

| REVEAL | Ishibashi, 2015 [39] | 12 months |

LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT PRN LP → RAN 0.5 mg IVT + Prompt Laser PRN Laser PRN Q12W |

396 |

| RHINE | Wykoff, 2022 [12] | 48, 52, 56 and average of 48, 52 and 56 weeks |

LP → FAR 6 mg IVT Q8W LP → FAR 6 mg IVT T&E LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W |

951 |

| ROTATE | Fechter, 2016 [40] | 12 months |

RAN 0.3 mg IVT Q4W LP → RAN 0.3 mg IVT PRN |

22 (30 eyes) |

| TREX-DME | Payne, 2017 [41] | 12 and 24 months |

RAN 0.3 mg IVT Q4W LP → RAN 0.3 mg IVT T&E LP → RAN 0.3 mg IVT + Laser T&E |

116 (150 eyes) |

| VISTA | Korobelnik, 2014 [42] | 12 and 24 months (100 weeks) |

AFL 2 mg IVT Q4W LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W Laser PRN (no more frequently than Q12W) |

466 |

| VIVID | Korobelnik, 2014 [42] | 12 and 24 months |

AFL 2 mg IVT Q4W LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W Laser PRN (no more frequently than Q12W) |

406 |

| VIVID-East | Chen, 2020 [43] | 12 months |

AFL 2 mg IVT Q4W LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W Laser PRN |

381 |

| YOSEMITE | Wykoff, 2022 [12] | 48, 52, 56 and average of 48, 52 and 56 weeks |

LP → FAR 6 mg IVT Q8W LP → FAR 6 mg IVT T&E LP → AFL 2 mg IVT Q8W |

940 |

AFL aflibercept, BEV bevacizumab, DEX dexamethasone, FAR faricimab, IVT intra-vitreal treatment, LP loading phase, OLE open label extension, PRN pro re nata, Q4/5Month every 4/5 months, Q6/8/12/16/24W every 6/8/12/16/24 weeks, RAN ranibizumab

Results of the study quality assessment indicated that the studies were generally of moderate to high quality, and the majority reported clear details on patient population and prognostic factors at baseline as well as methodological details regarding treatment regimens and missing data. Included studies were of low to medium risk of bias and sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding high risk of bias study showing consistent results (more details are provided in Fig. S9 in the supplemental material).

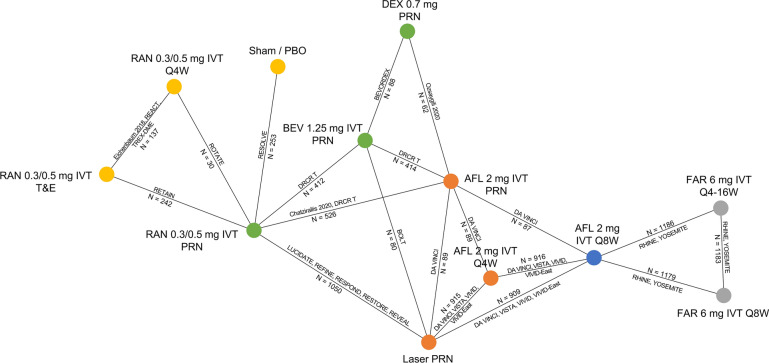

The network of studies reporting a mean change in BCVA score from baseline to 12 months is displayed in Fig. 2. Networks for other outcomes included in the NMA are reported in the Supplementary Material. The 0.3 mg and 0.5 mg ranibizumab doses were merged because of evidence suggesting no difference between them when used monthly [44]. Different treatment schedules (Q4W, Q8W, PRN and T&E) were treated as separate nodes.

Fig. 2.

Network for mean change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) score from baseline to 12 months. AFL aflibercept, BEV bevacizumab, DEX dexamethasone, FAR faricimab, IVT intravitreal, PBO placebo, PRN treatment as needed (pro re nata), Q4/8/16W every 4/8/16 weeks, RAN ranibizumab, T&E treat and extend. Colour-coded nodes illustrate the number of steps (pairwise comparisons) between faricimab and a given comparator to highlight how they are connected and what informs the estimation of the treatment effect. Blue = randomized controlled trial, red = 1 step, green = 2 steps, Yellow = 3 steps

Characteristics and Comparability of Included Studies

Covariates that previous studies identified as potential effect modifiers are baseline BCVA and baseline CST [45]. Although reporting of baseline CST was poor across studies, all studies reported similar baseline BCVA.

In terms of other baseline characteristics, there was some variation in age, gender and race between studies. For example, ages ranged from between 55 and 56.6 years in Fouda 2017 to between 68 and 69 years in the ROTATE trial, and the percentage of white patients ranged between 0% in REVEAL to 94–98% in RETAIN [29, 38–40].

Study design features that could potentially influence outcomes included permitting the use of rescue therapy for patients who require it and whether studies permitted randomization of one or both eyes to the intervention or comparator. Another study design feature that could potentially influence outcomes is the difference in treatment criteria within flexible dosing regimens. There is some variation between studies regarding loading doses and re-treatment criteria. Details of these are included in the Supplementary Material.

Network Meta-Analysis

The analyses for all outcomes were conducted using the standard NMA framework, given that there was no evidence indicating that the treatment effect differed by patient characteristics or that model fit was improved in the patient meta-regressions. No evidence of inconsistency was identified.

In general, convergence diagnostics were good, and model fit was good in most cases, with the exception of the fixed-effect model for the number of injections (including laser PRN) at 12 months. In this case, the random-effects model provided a much better fit. Random-effects models were chosen for all endpoints.

Efficacy

A statistically greater decrease in CST at 12 months from baseline was observed for faricimab T&E versus all other treatments given in flexible dosing regimens with credible intervals not crossing zero. This greater reduction in retinal thickness is considered clinically meaningful [46]. Amongst all treatments given in flexible dosing regimens, faricimab T&E had the highest probability of performing best.

The mean change in BCVA score from baseline of faricimab T&E was statistically greater than that of ranibizumab, bevacizumab, laser and dexamethasone therapy. Faricimab T&E was also associated with a numerical improvement of two letters compared to aflibercept PRN with credible intervals crossing zero. It had the highest probability of performing best amongst all treatments given in flexible dosing regimens. Accordingly, the probability that faricimab T&E was non-inferior versus all comparators was close to one, using a four-letter threshold following the definition in YOSEMITE and RHINE [12].

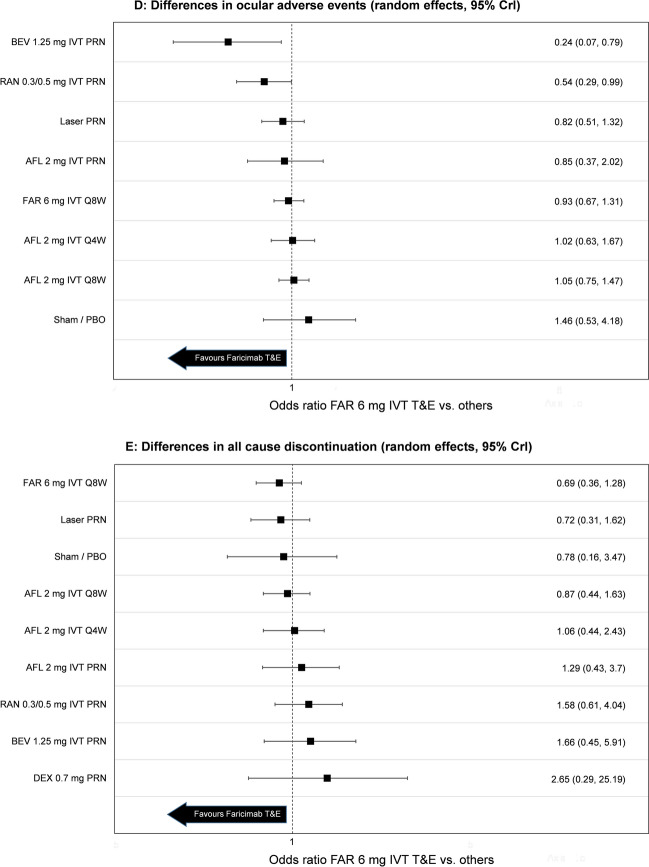

NMA efficacy results including mean difference in change from baseline of BCVA score and mean difference in change from baseline of CST are presented in Fig. 3. Additional results including median rank, probability of each treatment performing best and surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) are contained in the Supplementary Material for all efficacy outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of results obtained through the network meta-analysis for A mean change in BCVA at 12 months from baseline, B mean change in central subfield thickness (CST) at 12 months from baseline, C injection frequency at 12 months, D ocular adverse events at 12 months and E all cause discontinuation. AFL aflibercept, BEV bevacizumab, DEX dexamethasone, FAR faricimab, IVT intra-vitreal treatment, LP loading phase, OLE open label extension, PBO placebo, PRN pro re nata, Q6/8/12/16W every 6/8/12/16 weeks, RAN ranibizumab, CrI credible interval

Injection Frequency

NMAs for injection frequency at 12 months were constructed with and without laser PRN. Treatment effects from networks with and without laser PRN were deemed similar, but since between-study heterogeneity was greater when laser PRN was included, the network without laser PRN was preferred.

Injection frequency was statistically lower for faricimab T&E compared to other treatments given in fixed Q4W or Q8W regimens. Faricimab T&E was also associated with numerically fewer injections versus other treatments given in flexible dosing regimens. Accordingly, faricimab T&E had the highest probability of performing best (83.3%) in terms of reducing injection frequency. NMA results for other comparators are shown in Fig. 3, and additional results including median rank, probability of each treatment performing best and the SUCRA are contained in the Supplementary Material.

Safety

Given the rare occurrence of ocular adverse events and treatment discontinuations as well as the limited available evidence, there is uncertainty in the model and the results should be interpreted with caution. Considering these limitations, the occurrence of ocular adverse events of faricimab T&E was statistically lower or comparable to all regimens. The results for the numbers of all-cause discontinuations were not statistically different.

Numbers and percentages of safety outcomes per treatment in each trial can be found in the Supplementary Material. NMA results for both the ocular adverse events and all cause discontinuations are shown in Fig. 3. Median rank, probability of each treatment performing best and the SUCRA are contained in the Supplementary Material.

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

There were no meaningful differences in terms of model fit or results between the fixed- and random-effects models for each outcome, with the exception of mean number of injections at 12 months as discussed in Sect. 4.4. The fixed-effects model for the mean number of injections network, particularly when including laser PRN, was found to be a poor fit to the data, with a larger residual deviance than number of data points. The random effects model was a much better fit for this outcome.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted for vision outcomes by excluding studies with laser rescue therapy (studies excluded were DA VINCI, DRCR Network Protocol T, RESOLVE, TREX-DME) and results were found to be consistent with the base case analysis [25, 26, 35, 41].

Treatment-naïve networks could be formed for mean change in BCVA score. Results for the anti-VEGF treatment-naïve population were consistent with the results of the whole population.

Discussion

To the knowledge of the authors, this SLR and NMA provides the first indirect comparison of faricimab T&E with other therapies in use for treatment of DME. The studies identified in the SLR and included in the NMA were of moderate-to-high quality. In YOSEMITE and RHINE, faricimab T&E was compared to aflibercept Q8W, meaning indirect comparisons were required to understand the relative efficacy of faricimab T&E compared to other DME treatments, particularly applied in flexible dosing regimens that are most commonly used in clinical practice. Since RCTs are considered gold standard in terms of evidence, conducting an NMA was the most appropriate method to use to attain this objective.

The NMA indicated that the safety profile of faricimab T&E was comparable to those of ranibizumab and aflibercept, which have well-established safety profiles, with similar results for the number of all-cause discontinuations.

The analysis also showed that after 1 year of treatment, faricimab T&E was associated with superior disease control, as expressed by a reduction in retinal thickness, versus all other treatments applied in flexible dosing regimens. This greater reduction in retinal thickness is considered clinically meaningful (> 50 microns) [45] and may point to the role of dual-pathway inhibition of VEGF and Ang-2 in promoting vascular stability and reducing inflammation. This finding is also consistent with the direct evidence in YOSEMITE and RHINE where faricimab T&E also demonstrated greater improvements versus aflibercept Q8W for anatomical outcomes, i.e. reduction in CST, absence of intraretinal fluid (IRF) and absence of DME [12].

Anatomical outcomes determine treatment efficacy and retreatment of patients. Accordingly, faricimab T&E was associated with numerically fewer injections versus other flexible dosing regimens indicating a higher probability for a lower treatment burden. Given the loading phase in year 1 and the gradual extension of intervals (e.g. in 4-week increments in YOSEMITE and RHINE), durability in T&E regimens is expected to further improve in year 2. This effect could also be seen in the pivotal studies as more patients were able to be maintained on longer treatment intervals [47].

The mean change in BCVA score from baseline of faricimab T&E was superior to ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Faricimab T&E was associated with an improvement of approximately five letters or one line on the BCVA chart. This result is consistent with a previous RCT by Sahni (2019), in which a statistically significant gain of 3.6 letters was observed for faricimab compared with ranibizumab after 6 months of treatment [46]. Faricimab T&E was also associated with a numerical improvement compared to aflibercept PRN and had the highest probability of performing best amongst all treatments given in flexible dosing regimens.

The NMA was conducted in accordance with the most recent methodological guidelines [20, 21, 48]. This includes the employment of a Bayesian framework as well as the inclusion of sensitivity analyses where appropriate. Study populations varied in some of their baseline characteristics, such as age and race, but were deemed similar in terms of characteristics that are established to affect outcomes, such as baseline BCVA [45].

Results were broadly consistent with those of the previous NMA of anti-VEGF treatments in DME by Muston (2018) and with a more recent NMA by Wang (2022) [49, 50]. These findings along with the above elements regarding study design demonstrate that the results from this NMA provide a robust, up-to-date comparison of faricimab T&E and other treatments for DME.

Muston suggests that previous analyses that have not adjusted for baseline BCVA are subject to ecological bias [49]. This was addressed in this study by incorporating BCVA at baseline as a covariate via meta-regression. However, there was no evidence that treatment effect differed by patient characteristics or that model fit was improved; hence, all further analyses were conducted under the standard NMA framework. This study captures variation within a treatment due to different dosing regimens, whereas Wang groups treatments regardless of regimen [50].

Time equivalence was assumed between 48 and 56 weeks, 12 months and 1-year outcomes. This is because the mean change in BCVA score was measured from baseline through weeks 48–56 in YOSEMITE and RHINE. However, several trials demonstrate that gains in visual acuity in DME are usually achieved within the first months of treatment with anti-VEGF therapy, and any further therapy beyond that point typically preserves these vision gains, with no further improvement. This suggests that there was no impact on the results because of the equivalence assumption. Aspiring to include as much relevant evidence as possible, other definitions of retinal thickness (CST, CRT, CFT, CMT, in that order) were used if CST values were not reported. These definitions are often used interchangeably, and previous NMAs have used similar approaches [51].

While the results from this NMA provide a current evaluation of the comparative efficacy, injection frequency and safety of faricimab T&E relative to other relevant therapies for treatment of diabetic macular oedema, several limitations were identified. First, while baseline CRT was listed as a potential effect modifier, reporting of baseline CRT was poor across studies. However, a published NMA found that CRT was highly correlated with baseline BCVA [49], and since baseline BCVA was found to be similar across studies, this is unlikely to limit the study. In addition, limited evidence was available for subgroup analyses, as well as for AEs, which made these networks less robust. Networks for BCVA for the anti-VEGF naïve subgroup contained only nine studies, whilst networks for ocular AEs contained only ten studies.

Conclusion

The results of this study support faricimab T&E as a treatment option for DME with the potential to offer the best disease control because of dual Ang-2/VEGF inhibition, improving outcomes and preventing vision loss, which can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Applied in a T&E regimen with a low treatment burden, it can give people living with DME greater independence and meet the current capacity constraints in many health systems and the expected increase in future demand for ophthalmology services [52].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Third-party writing assistance was provided by Craig Keenan and Emily Robertshaw of Putnam PHMR. This was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for the manuscript to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd also funded the Journal Rapid Service and the Open Access Fees.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Tatiana Paulo, Marloes Bagijn and Christian Bührer are employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Claire Watkins is an employee of Clarostat Consulting Ltd, which was contracted by F. Hoffmann-La Roche to undertake the data analysis for this study. Nancy M. Holekamp has served as a consultant for Acucela, Allergan, Apellis, Bayer, Clearside Biosciences, Gemini, Genentech, Inc., Gyroscope, Katalyst Surgical, Lineage Cell Therapeutics, Nacuity, Notal Vision, Novartis, PolyActiva, and Regeneron, and is currently a visiting professor at F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, Chee ML, Rim TH, Cheung N, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fong DS, Aiello LP, Ferris FL, 3rd, Klein R. Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2540–2553. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Song Y, Tao L, Qiu W, Lv H, Jiang X, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among 13473 patients with diabetes mellitus in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological survey in six provinces. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013199. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leasher JL, Bourne RR, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, Keeffe J, Naidoo K, et al. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis from 1990 to 2010. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1643–1649. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan GS, Cheung N, Simó R, Cheung GC, Wong TY. Diabetic macular oedema. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(2):143–155. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iglicki M, González DP, Loewenstein A, Zur D. Next-generation anti-VEGF agents for diabetic macular oedema. Eye (Lond) 2022;36(2):273–277. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01722-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virgili G, Parravano M, Evans JR, Gordon I, Lucenteforte E. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for diabetic macular oedema: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):Cd007419. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007419.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenick AS, Bressler NM. Diabetic macular edema: current and emerging therapies. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19(1):4–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.92110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dervenis N, Mikropoulou AM, Tranos P, Dervenis P. Ranibizumab in the treatment of diabetic macular edema: a review of the current status, unmet needs, and emerging challenges. Adv Ther. 2017;34(6):1270–1282. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0548-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holz FG, Tadayoni R, Beatty S, Berger A, Cereda MG, Hykin P, et al. Key drivers of visual acuity gains in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in real life: findings from the AURA study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(12):1623–1628. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modi Y, Csaky K, Sheth V, Willis J, Haskova Z, Westenskow P. Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) signaling and vascular stability with faricimab in diabetic macular edema (DME) Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63(7):2522–F0248. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wykoff CC, Abreu F, Adamis AP, Basu K, Eichenbaum DA, Haskova Z, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in patients with diabetic macular oedema (YOSEMITE and RHINE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10326):741–755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CRD. Systematic Reviews. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. University of York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009.

- 14.Higgins JT, J. Chandler, J. Cumpston, M. Li, T. Page, MJ. Welch, VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.NICE. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Process and methods [PMG20]. 2018.

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NICE. Single technology appraisal: user guide for company evidence submission template 2016.

- 18.Plummer M, editor. JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. In: Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on distributed statistical computing, Vienna. 2003.

- 19.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2021.

- 20.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, Ades AE. Evidence synthesis for decision making 3: heterogeneity–subgroups, meta-regression, bias, and bias-adjustment. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(5):618–640. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13485157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Caldwell DM, Lu G, Ades AE. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(5):641–656. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12455847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillies MC, Lim LL, Campain A, Quin GJ, Salem W, Li J, et al. A randomized clinical trial of intravitreal bevacizumab versus intravitreal dexamethasone for diabetic macular edema: the BEVORDEX study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(12):2473–2481. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michaelides M, Kaines A, Hamilton RD, Fraser-Bell S, Rajendram R, Quhill F, et al. A prospective randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy in the management of diabetic macular edema (BOLT study) 12-month data: report 2. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1078–86.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatzirallis A, Theodossiadis P, Droutsas K, Koutsandrea C, Ladas I, Moschos MM. Ranibizumab versus aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 18-month results of a comparative, prospective, randomized study and multivariate analysis of visual outcome predictors. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2020;39(4):317–322. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2020.1802741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Do DV, Nguyen QD, Boyer D, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Brown DM, Vitti R, et al. One-year outcomes of the da Vinci Study of VEGF Trap-Eye in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1658–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eichenbaum DA, Duerr E, Patel HR, Pollack SM. Monthly versus treat-and-extend ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: a prospective, randomized trial. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49(11):e191–e197. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20181101-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report number 1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study research group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(12):1796–806. [PubMed]

- 29.Fouda SM, Bahgat AM. Intravitreal aflibercept versus intravitreal ranibizumab for the treatment of diabetic macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:567–571. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S131381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comyn O, Sivaprasad S, Peto T, Neveu MM, Holder GE, Xing W, et al. A randomized trial to assess functional and structural effects of ranibizumab versus laser in diabetic macular edema (the LUCIDATE study) Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(5):960–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyer DS, Yoon YH, Belfort R, Jr, Bandello F, Maturi RK, Augustin AJ, et al. Three-year, randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1904–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozsaygili C, Duru N. Comparison of intravitreal dexamethasone implant and aflibercept in patients with treatment-naive diabetic macular edema with serous retinal detachment. Retina. 2020;40(6):1044–1052. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehlers JP, Wang K, Singh RP, Babiuch AS, Schachat AP, Yuan A, et al. A prospective randomized comparative dosing trial of ranibizumab in bevacizumab-resistant diabetic macular edema: the REACT study. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Dai H, Li X, Han M, Li J, Suhner A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ranibizumab 0.5 mg in Chinese patients with visual impairment due to diabetic macular edema: results from the 12-month REFINE study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(3):529–541. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-04213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massin P, Bandello F, Garweg JG, Hansen LL, Harding SP, Larsen M, et al. Safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema (RESOLVE study): a 12-month, randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter phase II study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2399–2405. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berger A, Sheidow T, Cruess AF, Arbour JD, Courseau AS, de Takacsy F. Efficacy/safety of ranibizumab monotherapy or with laser versus laser monotherapy in DME. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50(3):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell P, Bandello F, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lang GE, Massin P, Schlingemann RO, et al. The RESTORE study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prünte C, Fajnkuchen F, Mahmood S, Ricci F, Hatz K, Studnička J, et al. Ranibizumab 0.5 mg treat-and-extend regimen for diabetic macular oedema: the RETAIN study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(6):787–795. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishibashi T, Li X, Koh A, Lai TY, Lee FL, Lee WK, et al. The REVEAL study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy in Asian patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1402–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fechter C, Frazier H, Marcus WB, Farooq A, Singh H, Marcus DM. Ranibizumab 0.3 mg for persistent diabetic macular edema after recent, frequent, and chronic bevacizumab: the ROTATE trial. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47(11):1–18. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20161031-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Payne JF, Wykoff CC, Clark WL, Bruce BB, Boyer DS, Brown DM. Randomized trial of treat and extend ranibizumab with and without navigated laser for diabetic macular edema: TREX-DME 1 year outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korobelnik JF, Do DV, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Boyer DS, Holz FG, Heier JS, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2247–2254. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YX, Li XX, Yoon YH, Sun X, Astakhov Y, Xu G, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept versus laser photocoagulation in Asian patients with diabetic macular edema: the VIVID-East Study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:741–750. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S235267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heier JS, Bressler NM, Avery RL, Bakri SJ, Boyer DS, Brown DM, et al. Comparison of aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab for treatment of diabetic macular edema: extrapolation of data to clinical practice. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(1):95–99. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regnier S, Malcolm W, Allen F, Wright J, Bezlyak V. Efficacy of anti-VEGF and laser photocoagulation in the treatment of visual impairment due to diabetic macular edema: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e102309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bressler NM, Miller KM, Beck RW, Bressler SB, Glassman AR, Kitchens JW, et al. Observational study of subclinical diabetic macular edema. Eye. 2012;26(6):833–840. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wells JA, Asik K, Haskova Z, Ives J, Silverman D, Tang Y, et al., editors. Faricimab in diabetic macular edema: two-year results from the phase 3 YOSEMITE and RHINE Trials. In: Angiogenesis, exudation, and degeneration 2022 virtual congress 2022.

- 48.Dias S, Sutton A, Ades A, Welton N. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2 a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(5):607–617. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12458724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muston D, Korobelnik JF, Reason T, Hawkins N, Chatzitheofilou I, Ryan F, et al. An efficacy comparison of anti-vascular growth factor agents and laser photocoagulation in diabetic macular edema: a network meta-analysis incorporating individual patient-level data. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-1006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, He X, Qi F, Liu J, Wu J. Different anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for patients with diabetic macular edema: a network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:876386. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.876386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Wang W, Gao Y, Lan J, Xie L. The efficacy and safety of current treatments in diabetic macular edema: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gale R, Cox O, Keenan C, Chakravarthy U. Health technology assessment of new retinal treatments; the need to capture healthcare capacity issues. Eye (Lond) 2022;36(12):2236–2238. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02149-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.