Abstract

Nucleic acid double helices in their DNA, RNA, and DNA-RNA hybrid form play a fundamental role in biology and are main building blocks of artificial nanostructures, but how their properties depend on temperature remains poorly understood. Here, we report thermal dependence of dynamic bending persistence length, twist rigidity, stretch modulus, and twist-stretch coupling for DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplexes between 7°C and 47°C. The results are based on all-atom molecular dynamics simulations using different force field parameterizations. We first demonstrate that unrestrained molecular dynamics can reproduce experimentally known mechanical properties of the duplexes at room temperature. Beyond experimentally known features, we also infer the twist rigidity and twist-stretch coupling of the hybrid duplex. As for the temperature dependence, we found that increasing temperature softens all the duplexes with respect to bending, twisting, and stretching. The relative decrease of the stretch moduli is 0.003–0.004/°C, similar for all the duplex variants despite their very different stretching stiffness, whereas RNA twist stiffness decreases by 0.003/°C, and smaller values are found for the other elastic moduli. The twist-stretch couplings are nearly unaffected by temperature. The stretching, bending, and twisting stiffness all include an important entropic component. Relation of our results to the two-state model of DNA flexibility is discussed. Our work provides temperature-dependent elasticity of nucleic acid duplexes at the microsecond scale relevant for initial stages of protein binding.

Graphical abstract

Significance

Nucleic acid double helices in their DNA and RNA forms, as well as hybrid double helices combining a DNA and an RNA strand, play a key role in biology and nanotechnological applications. Our work examines, by means of extensive computer simulations and analysis, how the mechanical rigidity of these helices changes with temperature. We found that, as temperature increases, the helices get softer, and we established the stiffness decrease quantitatively. Our results will help to understand biological mechanisms of thermal adaptation and aid the design of nucleic acid nanostructures operating at various temperatures.

Introduction

Double-stranded DNA is a key biological macromolecule, carrying genetic information in all cellular life. RNA in biological contexts can take up a variety of structures, but its double helical form is a prominent motif (1). Hybrid DNA-RNA duplexes emerge naturally during replication and transcription, are part of the so-called R-loops, and are also related to disease (2). Organisms can survive in astonishingly broad range of temperatures, from nearly 0°C up to 100°C (3). Moreover, thermal effects on cellular physiology emerge as a consequence of global warming and thermal pollution, with implications on health and disease; for instance, temperature is a critical factor defining the outcome of viral infections and the direction of viral evolution (4). Nevertheless, mechanisms of thermal adaptation at the molecular level are only starting to be understood (5,6,7). DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplexes are also basic building blocks of artificial nanostructures (8,9,10), and it is important to predict how these structures will respond to external loads and resist thermal fluctuations in a range of operational temperatures. For these reasons, we need to better understand how mechanical properties of DNA, RNA, and hybrid DNA-RNA duplexes depend on temperature.

Several experimental studies examined temperature dependence of DNA bending persistence length and twist rigidity (11,12,13,14). A simulation study (15) investigated thermal effects on DNA at the local scale of rigid bases and base pairs. From these local data, the authors deduced temperature-related changes of the persistence length and predicted thermal stabilization of DNA duplex by applied torque. In previous collaborative work focused on thermal dependence of DNA twist (16), our all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) data yielded the twist-temperature change in quantitative agreement with magnetic tweezer (MT) measurements, adding confidence to the use of MD simulations to probe thermal effects on the DNA duplex. A follow-up MD study (17) suggested that, in response to rising temperature, DNA mainly increases its diameter, whereas its length measured along the helical axis stays nearly constant. Despite these advances, how mechanical properties of the DNA double helix respond to temperature is still not fully understood.

As for the thermal effects on the elasticity of RNA double helices, we enter a largely uncharted territory. The temperature-dependent twist of double-stranded RNA has recently been measured (18), but how the RNA duplex elasticity depends on temperature is not known. The bending persistence length and stretch modulus of a DNA-RNA hybrid duplex at room temperature have only recently been experimentally established (19), but their thermal dependence has not been studied. Given the paucity of experimental results, unrestrained MD simulations appear as a viable alternative to study temperature-dependent mechanical properties of nucleic acid (NA) duplexes.

An extensive effort has been put into the characterization of an NA duplex as a mechanical system of interacting rigid bodies. The research initially focused on DNA (20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29) but was soon extended also to RNA (29,30,31,32) and hybrid duplexes (29,33). Models of various locality and structural detail were proposed, and X-ray structural ensembles as well as MD were used as the source of data. A complementary approach consists in employing unrestrained MD to deduce elastic constants describing an NA oligomer as a piece of a flexible rod. This method, introduced for DNA in an early work (34), has since then been developed by various authors (see for example (31,35,36,37,38,39)). It was applied to both DNA and RNA helices to quantitatively reproduce their opposing twist-stretch couplings and to unveil the microscopic origin of this difference (40). The twist-stretch coupling of the hybrid duplex has been inferred from MD simulations of short oligomers (41). An extensive study deduced sequence-dependent DNA bending persistence length using a coarse-grain model parameterized from unrestrained MD simulations (42). Theoretical and simulation approaches have been put forward to characterize the transition between the rigid body and flexible rod scales (38,39,43,44,45). In addition to the unrestrained MD simulations, mechanical properties of DNA and RNA duplexes have also been studied by MD at constant stretching force (46,47,48), enabling one to examine the dependence of the elastic constants on the applied force (49). These and other results, summarized in recent reviews (50,51,52,53,54), demonstrate the utility of atomic-resolution MD simulations to probe elastic properties of NA duplexes. The question of how RNA and DNA-RNA duplex elasticity depend on temperature, however, still remains open.

In the present work, we apply atomic-resolution, unrestrained MD simulations to examine temperature dependence of bending, twisting, and stretching flexibility, as well as the coupling between twisting and stretching, for NA duplexes in their DNA, RNA, and hybrid forms. As a source of data, we produced atomic-resolution MD trajectories of a 33-base-pair (bp) duplex in its DNA, RNA, and DNA-RNA hybrid versions. Simulations at five different temperatures between 7°C and 47°C were performed. To check the robustness of the results, the simulations were repeated using several NA force fields, ion parameters, and water models. From the MD trajectories, time series of suitably chosen conformational descriptors were extracted. The dynamic bending persistence length was deduced using local tangent vectors to the oligomer, with the static structure factorized out, and a constant prefactor to account for the nonzero offset in the semilog plot. Fluctuations of the oligomer length and global twist were employed to compute the stretch modulus, twist rigidity, and twist-stretch coupling. In particular, we report the twist stiffness of the DNA-RNA hybrid and unveil how the definition of the global twist affects the MD-derived twist-stretch coupling value. The results suggest that bending, twisting, and stretching stiffness of NA duplexes on the microsecond timescale decrease with temperature, whereas the twist-stretch coupling remains nearly constant. The enthalpic and entropic component of the stiffness constants are deconvoluted. Finally, we discuss the relation of our results to Schurr’s two-state model of temperature-dependent DNA shape and stiffness.

Materials and methods

MD simulations

The simulated 33-bp DNA oligomer, whose sequence of the reference strand reads GAGAT GCTAA CCCTG ATCGC TGATT CCTTG GAC, was used in previous studies (16,53,55). The sequence is mixed, contains each of the 10 unique dinucleotide steps at least once, and lacks any particular motifs such as polypurine tracts or short repetitive sequences. The GC content of the central 27-bp part taken for the analysis is 48%. The RNA sequence was obtained from the DNA one by mutating T to U in both strands, whereas only the complementary strand was mutated to obtain the hybrid. The Amber17 suite of programs was used to perform the simulations. The Amber OL15 (56) and bsc1 (57) force fields were employed for DNA, whereas the χOL3 (58,59) and Shaw (60) parameter sets were used for RNA. The Dang (61) and Joung-Cheatham (JC) (62) ion parameters and the SPC/E (63) as well as TIP4P-Ew (64) water models were utilized, with the exception of the Shaw RNA force field, which was combined with its recommended CHARMM22 ion parameters (65) and the TIP4P-D water model (66). The parameter combinations tested are in Table S1.

The DNA and RNA duplexes were built in their canonical B and A form, respectively, using the “nab” module of Amber. To build the hybrid, the 3D-NuS server (67), with the “sequence specific model” and “nmr” options, was used. The systems were immersed in an octahedral periodic box containing the duplex, water molecules, K+ ions to neutralize the duplex charge, and additional K+ and Cl− ions to mimic the physiological concentration of 150 mM KCl. They were then subjected to a series of energy minimizations and short MD runs before starting the production of MD trajectories, 1 μs each. Hydrogen mass repartitioning and the time step of 4 fs were employed. Details of the protocol can be found elsewhere (16). Only the inner 27 bp (or 26-bp steps) were analyzed; 3 bp at each end were excluded.

Analysis

We define the length of the 27-bp oligomer and its parts (fragments) as the sum of helical rises defined by the 3DNA conformational analysis algorithm (68). The global twist (or twist for short) is defined in two ways, either as the sum of 3DNA helical twists (40) or as the end-to-end twist between suitably chosen coordinate frames at the ends of the fragment (end frames). The twist between the end frames is computed in a manner exactly analogous to the 3DNA local twist between adjacent base-pair frames (16). The end frames are base-pair frames of the end pairs provided by 3DNA, rotated so that their z axis aligns with the direction of the local helical axis (the mean direction of the helical axes for the two steps flanking the pair, again computed by 3DNA). This ensures that, in the open structures of the RNA and the hybrid, we probe the movement of the double helix (the “spring”), rather than that of the stripe of base pairs surrounding the central void (the “wire”) (17,46,69). The deformation free energy is assumed to be a quadratic function of the coordinates (34,53),

| (1) |

Here, is the coordinate vector, is the equilibrium length of the duplex, and is the vector of equilibrium values of the coordinates. The equilibrium values are estimated as means over the simulated trajectory. The stiffness matrix is related to the coordinate covariance matrix , again estimated from the MD data, as

| (2) |

where the superscript −1 denotes the matrix inverse (53).

We first consider a one-dimensional (1D) case with only one coordinate. In that case, is just one number, the coordinate variance , and the stiffness matrix reduces to one force constant. Taking the duplex length as the coordinate, we obtain the stretch modulus of pulling the duplex, whereas all other degrees of freedom are relaxed (integrated out), as in a typical magnetic or optical tweezer experiment. Taking the twist instead, we obtain the elastic modulus of twisting the duplex, whereas all other degrees of freedom are relaxed (it is common to work with the twist stiffness , which is expressed in units of length). Considering the fragment length and twist simultaneously, we have a two-component vector , the covariance and the stiffness are both 2-by-2 matrices, and we also obtain, in addition to the 2D values of stretch modulus and twist rigidity (which are now somewhat higher than their 1D counterparts), the twist-stretch coupling, represented by the off-diagonal element . It is convenient to express the coupling in terms of the coefficient indicating the length change upon overtwisting the duplex by one turn. It can be computed as a ratio of the stiffness matrix elements (40),

| (3) |

Finally, we characterize the duplex by its bending persistence length (p.l.). Since we examine a single short sequence, we can deduce just the dynamic bending p.l., , capturing the effect of thermal fluctuations rather than static disorder. We define as in Ref. (53),

| (4) |

On the left is the ensemble mean, again computed from the MD trajectory, for the scalar product of the unit tangent vectors associated with pairs 0 and i, and on the right are these same tangent vectors but for the equilibrium structure. The latter is obtained by first computing the trajectory means of local intra-base-pair and step rigid base coordinates (buckle, propeller, opening, shear, stretch, stagger; tilt, roll, local twist, shift, slide, and rise) as defined by 3DNA and rebuilding the structure at the rigid base level from these means. We consider two definitions of the tangent vectors: the standard choice of the base-pair normals (42) and the directions of the local helical axis (53). Plotting the logarithm of against the fragment length between base pairs 0 and i (semilog plot), and fitting with a linear function, yields . The prefactor involving the static tangent vectors, proposed in (42), serves to deconvolute the equilibrium fragment shape, which, if not straight, would bias the linear fit. The constant allows for an offset in the fitting (53). In a model of straight DNA, has been shown to stem from integrating out the internal, translational degrees of freedom (70). Here, we include the constant without investigating its microscopic basis, simply because the linear fit clearly does not pass through the coordinate origin. In the computations, base pair 0 is the first pair of the analyzed 27-bp fragment, and the index i runs from 1 to 26. Notice that, contrary to various prior treatments where the persistence length was expressed in terms of base pairs and then multiplied by a fixed inter-base-pair distance (usually 3.4 Å for DNA), in Eq. 4 we consider the actual simulated length of each fragment.

Convergence check

To verify that our MD trajectories are long enough, we perform the following convergence test for the global coordinates of the 27-bp oligomer: the end-to-end twist, the sum of helical twists, and the oligomer length. Each coordinate is examined individually. For the MD time series of the (1D) coordinate , of length (), we first discard the initial time interval from 0 to . We then infer the probability density function (pdf) of from the MD time series for the time interval from to , denoted by , as well as for the first half and the second half of this interval, denoted by and , respectively. Next, we calculate the Kullback-Leibler divergences

| (5) |

where . Notice that the divergences depend on the length of the initial discarded interval. Finally, we take the arithmetic mean of the two,

| (6) |

The quantity indicates how similar the coordinate pdf for the whole trajectory is to the pdfs for its halves, provided that the data in the initial time interval of length are discarded. If, for instance, there were major conformational rearrangements at the beginning, then discarding them would improve the similarity. On the other hand, discarding too much would mean leaving too few data to analyze. Thus, one would expect as a function of to initially decrease, reach an optimal domain, then increase again for large .

We performed the test on our MD data. The integration in Eq. 5 was extended over the range of the observed values and was computed numerically. Thus, at this stage, we did not assume any particular form of the pdf (e.g., they need not be Gaussian). Examples of as a function of the discarded time for a DNA, an RNA, and a hybrid simulation are in Fig. S1, and the other simulations behave similarly. It is seen that there is no initial decrease of , suggesting no major equilibration event at the beginning of the production MD. We also observe that, in the case of DNA and the hybrid, starts to increase rather early, after discarding the initial 300 ns or so; i.e., leaving less than 700 ns for the analysis would already increase the difference between the trajectory halves and the whole. In the case of RNA, however, one can discard a much longer interval before the divergence starts increasing. This indicates a much faster sampling of the conformational space in the case of the RNA helix compared to DNA and hybrid helices, probably due to the fact that double-stranded RNA does not contain backbone substates analogous to BI/BII in DNA, whose populations take long to converge.

Motivated by these observations, we estimate the error of a quantity deduced from the MD trajectory as the mean absolute difference between values for the whole trajectory (1 μs) and for its halves (500 ns each).

Combining results from different MD simulations

In this work, we compute properties (e.g., the stretch modulus) of the inner 27-bp DNA fragment of our sequence from MD simulations using different NA force fields, ion parameters, and water models. For an individual MD simulation, we estimate the error as indicated above. Thus, we get multiple values of the same quantity, each deduced from a different MD simulation, together with its own error estimate, and we want to somehow combine (fuse) these values to obtain a more robust result with smaller uncertainty. To do this, we look at the individual MD results as if they were measurements of the same quantity, but each with a different measuring device (sensor), and use the confidence-weighted averaging algorithm (71) to fuse them. Suppose we do n measurements, each yielding the value and error . The fused value is then computed as a weighted average of the individual measurements,

| (7) |

The weights are given by

| (8) |

where the fused error takes the form

| (9) |

Thus, the measurements are weighted according to their errors, so that values with larger errors weight less. It follows from Eqs. 8) and 9) that the sum of the weights is equal to 1, as it should be. To see how the scheme works in practice, take the DNA stretch modulus (Table S1, first two lines) as an example. We have , , , (all values in pN). From Eq. 9 we find the fused error , smaller than any of the individual errors, and from Eq. 8 we deduce the weights , . Thus, the fused value of the stretch modulus, obtained by combining the two measurements, is . Fused values together with their fused errors are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Values of the stiffness constants at 27°C

| (nm) | (pN) | (nm) | (nm/turn) | a (nm) | ka(nm/turn) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | 67 ± 1 | 1490 ± 12 | 109 ± 1 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 118 ± 1 | 0.69 ± 0.01 |

| DNA-RNA | 78 ± 0 | 790 ± 2 | 123 ± 1 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 121 ± 1 | −0.13 ± 0.02 |

| RNA | 81 ± 0 | 657 ± 4 | 123 ± 1 | −0.60 ± 0.01 | 126 ± 1 | −0.95 ± 0.01 |

Values for the global twist defined as the sum of 3DNA helical twists.

Results

Our model of the duplex stretching and twisting contains two coordinates, the duplex length and its twist (computed either as the end-to-end twist or as a sum of 3DNA helical twists). The time series of the coordinates, as well as those of the bending angle, for all the systems and all temperatures are shown in Figs. S2–S6. No structural anomaly, such as kinking or unwinding, is observed in the data at any temperature. The 1D coordinate distributions for all the systems and all temperatures are in Figs. S7–S11. They are all very close to Gaussian, strongly supporting the assumption of quadratic deformation energy.

Twisting and stretching stiffness at room temperature

We first compute the stretch modulus while the twist is integrated out (the 1D case above). The fused results are in Table 1, and results for the individual MD simulations are in Table S1. Experimental values of DNA stretch modulus range from ca. 1000 to 1500 pN, whereas 350–500 pN were reported for RNA (69,72). A recent MT study (19) found ∼1300 pN for DNA, ∼630 pN for RNA, and ∼660 pN for the hybrid at 100 mM NaCl. Our values are on average slightly above these experimental results but correctly reproduce the ordering RNA < hybrid < DNA, as well as the hybrid stretch modulus being much closer to the RNA value than to the DNA one. MT experiments indicate both DNA and RNA intrinsic twist rigidities close to 100 nm (69). Our results (Tables 1 and S1) are once again moderately higher than that, and are slightly higher for RNA than for DNA. The experimental twist stiffness of the DNA-RNA hybrid duplex, to our knowledge, has not been reported. Our results indicate that it may be similar to the RNA value.

Next, we consider stretching and twisting simultaneously (the 2D case). The resulting stretch moduli and twist stiffness constants (not shown) are now slightly higher than their 1D counterparts, and we also obtain the twist-stretch coupling coefficient (Tables 1 and S1). Experiments show that has opposite signs for DNA and RNA: DNA elongates upon overtwisting, whereas RNA shortens (69). Earlier unrestrained MD simulations, as well as MD under constant stretching force, were able to reproduce this finding (40,46). Just as in these earlier studies, our results compare favorably with the measured 0.42–0.5 nm/turn for DNA and −0.85 nm/turn for RNA (69). The two twist definitions yield somewhat different values of the twist-stretch coupling. In particular, they give different couplings for the hybrid: although the 3DNA helical-twist sum indicates a coupling close to zero, as deduced earlier from linear fitting of helical rise vs. helical twist in MD simulations of short oligomers (41), the end-to-end twist definition yields a distinctly positive value, albeit smaller than the DNA one. To our knowledge, the experimental value of the twist-stretch coupling for the DNA-RNA hybrid has not yet been reported. In a prior study on temperature dependence of DNA twist (16), the end-to-end twist decrease with temperature observed in MD agreed quantitatively with MT measurements, whereas the decrease of the sum of 3DNA helical twists underestimated the MT data. Indeed, the end-to-end twist is closer in spirit to the MT experimental setup and may be more directly comparable to the MT data. Nevertheless, we found that the twist-stretch couplings for various simulations obtained using the two twist definitions (Table S1) are tightly linearly correlated ().

Bending persistence length

The DNA dynamic bending persistence length was deduced here using two different definitions of the duplex tangent vectors. In addition to the standard choice of base-pair normals, we also tested the directions of the local helical axis, as we proposed earlier for DNA (53). The semilog plots for the choice of the base-pair normals are in Fig. 1. The DNA values decrease rather linearly (Fig. 1 A), whereas those for the RNA and the hybrid result in a characteristic oscillatory pattern due to the A-like structure of the molecules (Fig. 1 B and C). The static prefactor introduced in (42) filters this out, so that an excellent linear dependence is obtained (Fig. 1 D–F). The fitted lines do not pass through the origin; a small but discernible offset is reflected by the value of . The analogous plots based on the axis directions lack pronounced undulations, but the linear fit is poorer (Fig. S12). Nevertheless, the fitted are entirely consistent with the ones based on the normals (not shown), with . From now on we focus just on the values inferred using the base-pair normal vectors.

Figure 1.

Examples of semilog plots used to infer the bending persistence length. Base-pair normals are used as the duplex tangent vectors. If the prefactor related to the static structure is omitted in Eq. 4, the DNA data (A) decrease approximately linearly with the fragment length, whereas the data for the DNA-RNA hybrid (B) and for RNA (C) exhibit major undulations related to the A-like structure of the molecules. If, however, the prefactor is included (D–F), the data fit a linear function very well. The fitted straight lines clearly do no pass through the origin but are slightly shifted toward negative values. The offset is captured by the constant in Eq. 4. To see this figure in color, go online.

The fused values of are listed in Table 1, and the individual MD results are in Table S1. The DNA value is consistent with the dynamic persistence length of 78 ± 13 nm found in a cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) experiment (73). Experiments also indicate that the total persistence length for RNA is higher than for DNA (69,72,74), and a recent MT measurement found the hybrid value between the two (19). Our data in Table 1 suggest that the ordering DNA < hybrid < RNA applies to the dynamic persistence length as well. A recent thesis (75) examined dynamic persistence lengths of a pool of 220-bp sequences in their DNA, RNA, and hybrid version using a coarse-grained model. The peaks of the persistence length distributions they report follow the same ordering as above.

Temperature dependence

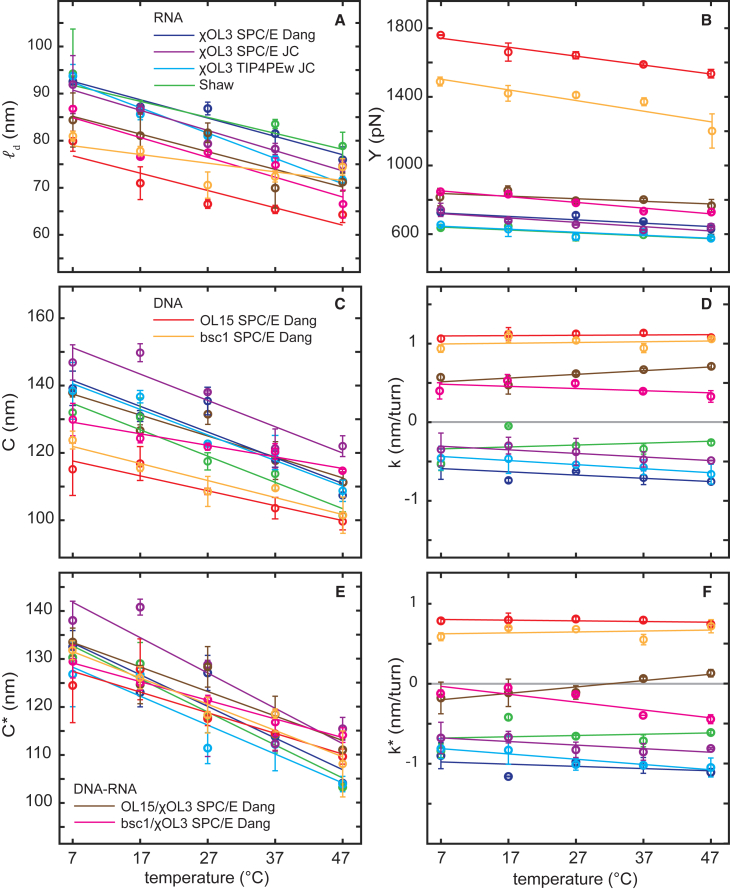

The temperature-induced changes of the stiffness parameters , , , and of the dynamic p.l. for the 27-bp fragment are shown in Fig. 2, the fused temperature slopes are listed in Table 2, and the data for the individual simulations are in Table S2. We observe that the dynamic p.l., stretch modulus, and twist stiffness of the DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplexes all decrease with temperature. The observed thermal decrease of the DNA persistence length, −0.21 nm/K, agrees quantitatively with the experimental values reported in (11). Specifically, a linear fit of the data obtained from the analysis of topoisomer distributions (Table 1 in (11)) between 5°C and 42°C yields −0.25 nm/K, the values from j-factor measurements (Figure 7 in (11), values listed in Table 4 of (76)) in the same temperature range gives −0.28 nm/K. We stress that our observation only concerns the dynamic persistence length.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the stiffness constants deduced from MD simulations. The dynamic bending persistence length (A), stretch modulus (B), twist rigidity (C), and twist-stretch coupling (D) are shown. (E and F) Twist stiffness and the coupling deduced using the sum of 3DNA helical twists rather than the end-to-end twist. Error bars are mean absolute differences between values for the whole trajectory and for its halves. The color coding shown in (A), (C), and (E) applies to all panels. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Temperature dependence of the stiffness constants

| (nm/K) | (nm/K) | (nm/K) | Ca/ (nm/K) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | −0.21 ± 0.02 | −5.59 ± 0.7 | −0.44 ± 0.12 | −0.52 ± 0.07 |

| DNA-RNA | −0.42 ± 0.06 | −3.1 ± 0.2 | −0.49 ± 0.10 | −0.41 ± 0.01 |

| RNA | −0.41 ± 0.02 | −1.8 ± 0.2 | −0.78 ± 0.02 | −0.73 ± 0.01 |

Values for the global twist defined as the sum of 3DNA helical twists.

Dividing the slopes in Table 2 by the room temperature values in Table 1 yields the relative decrease of the stretch modulus between 0.003 and 0.004/°C, surprisingly similar for all the double-helix variants despite their very different stretch moduli (Table 1). As for the twist stiffness, its definition already includes temperature, i.e., , where is the twist elastic modulus. Differentiating this relation with respect to temperature, we obtain

| (10) |

Similarly, we can associate to the bending p.l. a stiffness of a hypothetical homogeneous, straight isotropic rod by the relation . The quantities and are then related exactly as and in Eq. 10. Inserting values from Tables 1 and 2 yields the relative decrease of ∼0.001/°C or smaller for both and of the DNA duplex, a higher value of ∼0.003/°C for of the RNA duplex, and values in between for the other cases. The DNA and RNA twist-stretch couplings are nearly unaffected by temperature changes, their slopes being zero within statistical error (Table S3).

Inspired by the reasoning in (15), we estimate the enthalpic and entropic contributions to the stiffness constants. Just as in (15), we write the quadratic deformation free energy (Eq. 1) as

| (11) |

and assume that the enthalpy and the entropy are themselves also quadratic functions of the coordinates,

| (12) |

where the parameters are temperature independent. The equilibrium length is in general temperature dependent but cancels out in Eq. 11). Substituting Eq. 12 and Eq. 1 into Eq. 11 and taking the second derivative with respect to the coordinates, we find that the temperature-dependent stiffness is given by

| (13) |

Thus, is the stiffness matrix extrapolated to 0 K, whereas contains the (negative) temperature slopes of the constants in . In the 1D case, is just one constant and is its temperature slope. If the stiffness were purely enthalpic, then and the constants would be temperature independent.

Here, we focus on the (1D) stretching, bending, and twisting stiffness. Substituting the stiffness values at T = 300 K from Table 1 for and the slopes from Table 2 for , we use Eq. 13 to compute , i.e., the MD-derived stiffness constants extrapolated to 0 K. We find that, at 0 K, the DNA stretch modulus is more than twice as high compared to its room temperature value and therefore contains a major entropic component, whereas DNA bending stiffness and twist modulus increase by 20%–40% and are therefore less entropic in nature. For RNA, in contrast, all three elastic constants increase by 50%–90%, indicating a stronger entropic contribution, presumably related to the more open A-form structure of the RNA double helix. The hybrid duplex yields, as expected, somehow mixed results, with more than twofold increase in the stretch modulus, 60% in the bending stiffness, and less than 20% in the twist modulus. Thus, the bending, twisting, and stretching stiffness of the NA duplexes examined here all contain an important entropic component.

Discussion

Choice of the force field

The OL15 and bsc1 DNA force fields employed in this work are both state-of-the-art descriptions of DNA interatomic interactions that have been thoroughly tested (77,78). The same applies to the χOL3 and Shaw RNA force fields; a recent extensive MD study of RNA duplexes (79) concluded that both χOL3 and the Shaw force field (also called DESRES (79)) correctly describe the A-form RNA duplex structure.

The SPC/E water model, together with the TIP3P model (80), are among the most popular water models used in biomolecular MD. However, SPC/E provides more realistic viscosity (81), dielectric constant (82), as well as diffusivity and other characteristics (83,84) at ambient conditions than TIP3P. Remarkably, SPC/E reproduces the water dielectric constant rather well even at elevated temperatures (85). Besides these three-point models, four-point descriptions such as TIP4P-Ew (64) or TIP4P-D (66) are widely used. The temperature-dependent diffusivity of TIP4P-Ew is in excellent agreement with experiment (64), whereas its temperature-dependent viscosity is close to the SPC/E one and underestimates the experimental values (86), and its dielectric constant is also somewhat too low (82). As for the TIP4P-D model, it reproduces the temperature-dependent diffusivity and viscosity very well, whereas it again underestimates the temperature-dependent dielectric constant (87). It has been remarked that the inability to accurately describe the dielectric constant is related to the lack of polarizability of the models (84). Indeed, none of the many nonpolarizable models tested in (82), including five-point ones, were able to fully reproduce the complex dielectric spectra of water. Since it is not the purpose of this study to comprehensively test the dependence of our results on water models, we employ the SPC/E, TIP4P-Ew, and TIP4P-D models as outlined above and just exclude the TIP3P model. The Dang, JC, and CHARMM22 ion parameters employed here have been used in many previous MD studies on NAs. Several ion parameterizations including JC (but not the others considered here) have been tested for temperature-dependent mean ionic activity coefficients and solubilities, with no model performing clearly better than the others (88). However, we remark that it is not only the performance of the water and ion models as such but also their interactions with each other and with the solute that influence the outcome of the simulations.

Structural dynamics of DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplexes

In an earlier study, MD was used to probe thermal dependence of DNA stiffness at the local scale of rigid bases and base pairs (15). The results were then subjected to a coarse-graining procedure to deduce thermal changes of persistence length. The relatively short (50 ns) MD achievable at that time led to a much weaker decrease than the one deduced from equilibrium topoisomer distribution (11), but the two could be reconciled by assuming local transient denaturation bubbles. We do not observe any structural anomalies in our simulations, with the exception of short-lived alternative pairing in the RNA and the hybrid (Fig. S13) and exceptional visits of the RNA sugar pucker to the DNA region (Figs. S14 and S15). Nevertheless, different force fields may exhibit very different dynamics of the backbone torsion angles, the DNA bsc1 and RNA Shaw parameterizations being particularly colorful in this respect (Figs. S16–S19). The oligomer ends may break, but that almost never concerns more than two outermost pairs (Figs. S20–S23). These findings suggest that the decrease of the dynamic persistence length, as well as that of the stretch modulus and twist rigidity, over the temperature range and the timescale studied here may be achieved without any major distortion of the duplex structure. Assuming such distortions, however, might be necessary to explain the sharper decrease of p.l. at more elevated temperatures (the 60°C data point in Table 1 of (11) and in Fig. 5 of (15)).

Relation to the two-state model

A two-state model has been proposed to account for a number of diverse, at times seemingly contradictory, experimental results on DNA flexibility (see recent papers (14,76,89) and references therein). In the model, any base pair of a DNA duplex is supposed to be in one of two states, denoted a and b, each characterized by different values of the bending elastic constant , torsion elastic constant , and the helical rise . The bending elastic constant is related to the total (bending) persistence length P by

| (14) |

where T is the absolute temperature. Similarly, the torsion elastic constant is related to the twist rigidity C introduced above in this work, by the analogous relation

| (15) |

The a state is shorter, torsionally softer, but flexurally stiffer than the b state. The interconversion between the states takes place at a very long timescale and is highly cooperative; the mean domain size at the midpoint of the transition is around 224 bp. The total persistence length of a given DNA fragment is calculated from the fraction, , of its base pairs in the b state as

| (16) |

Entirely analogous relations hold also for the twist rigidity. In each of the two states, the bending persistence length is supposed to take the form

| (17) |

where the individual contributions represent fast-relaxing bends (assumed to relax at the submicrosecond scale), slow-relaxing bends, and nonrelaxing or permanent bends. Interestingly, there is no indication of a slow-relaxing torsional stiffness, so that just one, timescale independent, value is assumed for each state.

Importantly, the a and b states are both considered inextensible and their properties fixed under any circumstances within the range of validity of the model. All the predicted effects due to temperature changes, applied force, or buffer conditions are then due to the shift in population between the two states.

Besides many other applications, the model is able to solve the apparent discrepancy regarding the persistence length of intrinsically straight sequences. Cryo-EM studies indicate their persistence length much higher than that of natural sequences (73,90), whereas j-factor measurements of ∼200-bp fragments in a ligation buffer containing 10 mM Mg2+ suggest a value similar to that of a natural sequence (91). According to the two-state model, the intrinsic tension and the ligand conditions in the j-factor measurements drive the circular DNA predominantly to the b state, assumed intrinsically straight (), so that differences between natural and straight sequences are largely diminished. By contrast, DNA in the cryo-EM experiment is neither strained nor exposed to divalent ions, so that the difference between straight and natural DNA persists. However, one also has to take into account that DNA in this experiment is held at cryogenic temperatures. It is supposed that the fast-relaxing bends relax down to 223 K, so that must be rescaled accordingly, whereas the slow-relaxing bends do not relax within the estimated 100-μs vitrification time, so that is not rescaled. The model indeed yields very different persistence lengths in the two cases, each in quantitative agreement with the given experiment.

We may relate our results to the two-state model. Due to the microsecond simulation time and the short oligomer examined, we assume to sample just one DNA state (indeed, we observe no bimodality in the distributions of the oligomer length, Figs. S7–S11). The mean helical rise deduced from MD at 27°C (300 K) is 0.323 nm for the OL15 force field and 0.325 nm for bsc1, both with very small statistical error, so that we take nm, their mean. This value is roughly midway between the a and b helical rises of the two-state model. Our simulated DNA twist stiffness is nm. Thus, α = 13.9 × 10−19 J (Eq. 15), similar to 12.32 × 10−19 J assumed for the b state (see, e.g., Table 1 in (14)).

The case of the bending stiffness is more intricate. First, since the permanent bends are factorized out in our analysis, it is the persistence length of a straight sequence to compare our data with. Our value, 67 nm, lies near the lower end of the cryo-EM measurement range (82 ± 15 nm (90), later refined to 78 ± 13 nm (73)). On the other hand, numerous experiments indicate 170 nm on the submicrosecond scale and for ∼100–110 mM univalent cations (14), which at first sight seems more relevant to our case. However, a strict separation of timescales, clearly useful for modeling purposes, seems unlikely in reality. Rather, a fragment of DNA in solution is more likely to exhibit a continuum of relaxation times. Taking a few examples from the MD domain, the lifetimes of BI and BII backbone substates are on the order of 10–100 ps, monovalent ions around the DNA take hundreds of nanoseconds to equilibrate (92), and a correlation analysis of a long (44 μs) MD trajectory revealed two different timescales for equilibration of the DNA entropy, namely 2.1 and 10.5 μs (93). Moreover, the real timescale and the effective timescale of MD simulations need not be exactly the same. MD, being already coarse grained in some sense (although still fine grained compared to other models, such as oxDNA (94)), may sample the conformational space a bit faster than a real piece of DNA. Thus, it is plausible to assume that, besides the fast-relaxing bends detected in experiments, also slow-relaxing bends are partially sampled. Setting Ptot = 67 nm, Pf = 170 nm, in Eq. 17, we obtain Ps = 111 nm for the slow-relaxing part. Assuming now that both fast and slow contributions relax down to 223 K in the cryo-EM experiment, we have (300/223) × 67 nm = 90 nm, this time near the upper end of the cryo-EM experimental range. If only the fast part relaxes, we get 75 nm, very close to the cryo-EM value.

We now turn to the temperature-dependent twist elasticity. Based on numerous fluorescence polarization anisotropy measurements of plasmid DNAs in the absence of force, the two-state model assumes that for ∼100–110 mM univalent cations, the temperature-dependent torsion elastic constant is given by the following formula, which we take from Ref. (14):

| (18) |

This relation implies a relative change of with temperature equal to 0.011/K, an order of magnitude higher than the one we deduce from our MD simulations. Our result, however, can be reconciled with the two-state model: while the model describes the population shift between the states, assuming the properties of each state to be constant, our MD data, sampling just one state, provide a correction to this picture, namely that the torsion elastic constant of a given state is not constant but slightly decreases with temperature.

The data for the bending stiffness fully confirm this interpretation. The experiments in (11) have been critically re-analyzed using the two-state model (76), with the conclusion that the bending elastic constant in fact increases with temperature. A linear fit of obtained from the topoisomer data in (11) and reported in Table 2 of (76), gives the relative change of , a linear fit for the j-factor data (Table 4 in (76)) indicates . The j-factor data are based on small (∼200 bp) circular fragments in divalent salt, where the internal tension and the salt conditions shift the DNA toward the b state. As a result, the increase in the a state population due to rising temperature is smaller and the rise of is weaker compared to the large (2686 bp) circular DNA in the topoisomer experiment. However, it is a linear fragment rather than a circular one that is most relevant for us here. To estimate its properties, we proceed as follows. From Eq. 18 we compute at 278 K and 320 K. From this and from the values of in the a and b states (Table 1 in (14)), we obtain the populations and , which then yield , and finally the thermal change of relative to equal to , even higher than for the topoisomer experiment. In comparison, the relative change we deduce from the simulations is , of opposite sign but an order of magnitude smaller than the former one. Thus, once again, although the two-state model predicts a dramatic increase in the bending rigidity, assuming its value fixed in each state, our data indicate an additional slight decrease in each individual state.

Taken together, our results do not contradict the two-state model. Instead, they suggest a correction thereof: the bending and torsion rigidities of the individual states are not constant but gently decrease with temperature. The model also assumes the two states to be inextensible, but, at higher forces, the finite stretching stiffness starts to play a role, and in this work we provide the temperature dependence of the stretch modulus as well as that of the twist-stretch coupling. Moreover, we present results not only for DNA but also for RNA and the DNA-RNA hybrid double helices.

Our results should also be relevant to DNA under tension, as present, e.g., during transcription, replication, or homologous recombination. This applies all the more to MT experiments where DNA is often held at rather high forces (∼10 pN). In these situations, the tension would induce a high population of the b state, whose properties would then dominate over the thermal shift between the a and b state populations. Thus, the thermal changes of the DNA stiffness observed in MT experiments at high force should largely reflect the properties within the fixed state, which is the situation examined in this work.

Conclusions

We used all-atom, unrestrained MD simulations to probe temperature-dependent elastic properties of DNA, RNA, and hybrid DNA-RNA double helices. We employed several different parameterizations of interatomic interactions (force fields) to verify the robustness of the results and related our findings to experiments whenever possible. The good agreement with available experimental data indicates the ability of unrestrained MD simulations not only to examine mechanical properties of NA duplexes in their DNA form but also to model the mechanics of RNA and hybrid DNA-RNA double helices. Some of the elastic constants deduced here, to our knowledge, have not been measured. This concerns the twist rigidity of the hybrid duplex, which we inferred to lie within the RNA range, and the twist-stretch coupling of the hybrid. We found the MD value of the latter to critically depend on the exact definition of the duplex global twist. The definition that most closely resembles the MT setup yields a small positive value. Our data indicate that the stretch modulus, bending stiffness, and twist rigidity of all the molecules decrease with temperature, and we report their thermal slopes. In particular, the relative decrease of the stretch modulus is similar for the DNA, RNA, and hybrid duplexes, despite their very different stretching stiffness. The twist-stretch couplings of all the duplexes are nearly unaffected by temperature. Our data further suggest that the stiffnesses of the three duplex variants include an important entropic component. Relation to the two-state model of DNA flexibility is discussed. Our results provide temperature-dependent material properties of NA duplexes at the microsecond scale, relevant for diffusion encounter and binding of transcription factors. They may also inspire physical models of NA duplex elasticity.

Author contributions

H.D. and F.L. designed research. H.D. and E.M. performed the simulations and analysis. H.D. and F.L. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Michael Schurr for inspiring discussions and Marie Zgarbová for her help with preparing the simulations. This work was supported by grants of Specific University Research provided by the University of Chemistry and Technology, Prague (grant no. A2_FCHT_2020_047 to H.D. and F.L., and grant no. A1_FCHT_2023_010 to E.M.).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Editor: Jason Kahn.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2024.01.032.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Holbrook S.R. Structural principles from large RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:445–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera A., García-Muse T. R Loops: From transcription byproducts to threats for genome stability. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakashima H., Fukuchi S., Nishikawa K. Compositional changes in RNA, DNA and proteins for bacterial adaptation to higher and lower temperatures. J. Biochem. 2003;133:507–513. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisht K., te Velthuis A.J.W. Decoding the role of temperature in RNA virus infections. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.02021-22. e02021–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kortmann J., Narberhaus F. Bacterial RNA thermometers: molecular zippers and switches. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knapp B.D., Huang K.C. The effects of temperature on cellular physiology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2022;51:499–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-112221-074832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becskei A., Rahaman S. The life and death of RNA across temperatures. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022;20:4325–4336. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeman N.C. DNA in a material world. Nature. 2003;421:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature01406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabow W.W., Jaeger L. RNA self-assembly and RNA nanotechnology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:1871–1880. doi: 10.1021/ar500076k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko S.H., Su M., et al. Mao C. Synergistic self-assembly of RNA and DNA molecules. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1050–1055. doi: 10.1038/nchem.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geggier S., Kotlyar A., Vologodskii A. Temperature dependence of DNA persistence length. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1419–1426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driessen R.P.C., Sitters G., et al. Dame R.T. Effect of temperature on the intrinsic flexibility of DNA and its interaction with architectural proteins. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6430–6438. doi: 10.1021/bi500344j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet A., Salomé L., et al. Tardin C. How does temperature impact the conformation of single DNA molecules below melting temperature? Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:2074–2081. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schurr J.M. A quantitative model of cooperative two-state equilibrium in DNA: experimental tests, insights, and predictions. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2021;54:e5. doi: 10.1017/S0033583521000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer S., Jost D., et al. Everaers R. Temperature dependence of the DNA double helix at the nanoscale: Structure, elasticity, and fluctuations. Biophys. J. 2013;105:1904–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriegel F., Matek C., et al. Lipfert J. The temperature dependence of the helical twist of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:7998–8009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohnalová H., Dršata T., et al. Lankaš F. Compensatory Mechanisms in Temperature Dependence of DNA Double Helical Structure: Bending and Elongation. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2020;16:2857–2863. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian F.-J., Zhang C., et al. Dai L. Universality in RNA and DNA deformations induced by salt, temperature change, stretching force, and protein binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2218425120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C., Fu H., et al. Zhang X. The mechanical properties of RNA-DNA hybrid duplex stretched by magnetic tweezers. Biophys. J. 2019;116:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson W.K., Gorin A.A., et al. Zhurkin V.B. DNA sequence-dependent deformability deduced from protein-DNA crystal complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11163–11168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lankas F., Sponer J., et al. Cheatham T.E., III DNA basepair step deformability inferred from molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2872–2883. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lankas F., Sponer J., et al. Cheatham T.E., III DNA deformability at the base pair level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4124–4125. doi: 10.1021/ja0390449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lankas F., Gonzalez O., et al. Maddocks J.H. On the parameterization of rigid base and basepair models of DNA from molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10565–10588. doi: 10.1039/b919565n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez O., Petkevičiūtė D., Maddocks J.H. A sequence-dependent rigid-base model of DNA. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138 doi: 10.1063/1.4789411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petkevičiūtė D., Pasi M., et al. Maddocks J.H. cgDNA: a software package for the prediction of sequence-dependent coarse-grain free energies of B-form DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez O., Pasi M., et al. Maddocks J.H. Absolute versus relative entropy parameter estimation in a coarse-grain model of DNA. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2017;15:1073–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liebl K., Zacharias M. Accurate modeling of DNA conformational flexibility by a multivariate Ising model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021263118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Güell K., Battistini F., Orozco M. Correlated motions in DNA: Beyond base-pair step models of DNA flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:2633–2640. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma R., Patelli A.S., et al. Maddocks J.H. cgNA+web: A visual interface to the cgna+ sequence-dependent statistical mechanics model of double-stranded nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 2023;435 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2023.167978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez A., Noy A., et al. Orozco M. The relative flexibility of B-DNA and A-RNA duplexes: database analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6144–6151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noy A., Pérez A., et al. Orozco M. Relative flexibility of DNA and RNA: a molecular dynamics study. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battistini F., Sala A., et al. Orozco M. Sequence-dependent properties of the RNA duplex. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023;63:5259–5271. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c00741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noy A., Pérez A., et al. Orozco M. Structure, recognition properties, and flexibility of the DNA.RNA hybrid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4910–4920. doi: 10.1021/ja043293v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lankas F., Sponer J., et al. Langowski J. Sequence-dependent elastic properties of DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:695–709. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lankas F., Cheatham T.E., III, et al. Sponer J. Critical effect of the N2 amino group on structure, dynamics and elasticity of polypurine tracts. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2592–2609. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75601-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noy A., Golestanian R. Length scale dependence of DNA mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.228101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velasco-Berrelleza V., Burman M., et al. Noy A. SerraNA: a program to determine nucleic acids elasticity from simulation data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020;22:19254–19266. doi: 10.1039/d0cp02713h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nomidis S.K., Kriegel F., et al. Carlon E. Twist-bend coupling and the torsional response of double-stranded DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;118 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.217801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skoruppa E., Voorspoels A., et al. Carlon E. Length-scale-dependent elasticity in DNA from coarse-grained and all-atom models. Phys. Rev. E. 2021;103 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.103.042408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebl K., Drsata T., et al. Zacharias M. Explaining the striking difference in twist-stretch coupling between DNA and RNA: A comparative molecular dynamics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10143–10156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J.-H., Xi K., et al. Tan Z.-J. Structural flexibility of DNA-RNA hybrid duplex: Stretching and twist-stretch coupling. Biophys. J. 2019;117:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell J.S., Glowacki J., et al. Maddocks J.H. Sequence-dependent persistence lengths of DNA. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2017;13:1539–1555. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumoto A., Olson W.K. Sequence-dependent motions of DNA: A normal mode analysis at the base-pair level. Biophys. J. 2002;83:22–41. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker N.B., Everaers R. From rigid base pairs to semiflexible polymers: Coarse-graining DNA. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;76 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.021923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutiérrez Fosado Y.A., Landuzzi F., Sakaue T. Coarse graining DNA: Symmetry, nolocal elasticity, and persistence length. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023;130 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.058402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marin-Gonzalez A., Vilhena J.G., et al. Moreno-Herrero F. Understanding the mechanical response of double-stranded DNA and RNA under constant stretching force using all-atom molecular dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:7049–7054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705642114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marin-Gonzalez A., Vilhena J.G., et al. Perez R. Sequence-dependent mechanical properties of double-stranded RNA. Nanoscale. 2019;11:21471–21478. doi: 10.1039/c9nr07516j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marin-Gonzalez A., Pastrana C.L., et al. Moreno-Herrero F. Understanding the paradoxical mechanical response of in-phase A-tracts at different force regimes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:5024–5036. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luengo-Márquez J., Zalvide-Pombo J., et al. Assenza S. Force-dependent elasticity of nucleic acids. Nanoscale. 2023;15:6738–6744. doi: 10.1039/d2nr06324g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggarwal A., Naskar S., et al. Maiti P.K. What do we know about DNA mechanics so far? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020;64:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.da Rosa G., Grille L., et al. Dans P.D. Sequence-dependent structural properties of B-DNA: what have we learned in 40 years? Biophys. Rev. 2021;13:995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s12551-021-00893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marin-Gonzalez A., Vilhena J.G., et al. Moreno-Herrero F. A molecular view of DNA flexibility. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2021;54:e8. doi: 10.1017/S0033583521000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dohnalová H., Lankaš F. Deciphering the mechanical properties of B-DNA duplex. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022;12:e1575. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cruz-Leon S., Assenza S., et al. Guzman H.V. In: Physical Virology. Comas-Garcia M., Rosales-Mendoza S., editors. Vol. 24. Springer; Cham: 2023. RNA multiscale simulations as an interplay of electrostatic, mechanical properties, and structures inside viruses. (Springer Series in Biophysics). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cruz-León S., Vanderlinden W., et al. Schwierz N. Twisting DNA by salt. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:5726–5738. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zgarbová M., Šponer J., et al. Jurečka P. Refinement of the sugar-phosphate backbone torsion beta for Amber force fields improves the description of Z- and B-DNA. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2015;11:5723–5736. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ivani I., Dans P.D., et al. Orozco M. Parmbsc1: a refined force field for DNA simulations. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:55–58. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banáš P., Hollas D., et al. Otyepka M. Performance of molecular mechanics force fields for RNA simulations: stability of UUCG and GNRA hairpins. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2010;6:3836–3849. doi: 10.1021/ct100481h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zgarbová M., Otyepka M., et al. Jurečka P. Refinement of the Cornell et al. nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2011;7:2886–2902. doi: 10.1021/ct200162x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan D., Piana S., et al. Shaw D.E. RNA force field with accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art protein force fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E1346–E1355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713027115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dang L.X. Mechanism and thermodynamics of ion selectivity in aqueous solutions of 18-crown-6 ether: a molecular dynamics study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6954–6960. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joung I.S., Cheatham T.E., III Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berendsen H.J.C., Grigera J.R., Straatsma T.P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 1987;91:6269–6271. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Horn H.W., Swope W.C., et al. Head-Gordon T. Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:9665–9678. doi: 10.1063/1.1683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., et al. Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piana S., Donchev A.G., et al. Shaw D.E. Water dispersion interactions strongly influence simulated structural properties of disordered protein states. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:5113–5123. doi: 10.1021/jp508971m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patro L.P.P., Kumar A., et al. Rathinavelan T. 3D-NuS: A web server for automated modeling and visualization of non-canonical 3-dimensional nucleic acid structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:2438–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu X.-J., Olson W.K. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–5121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lipfert J., Skinner G.M., et al. Dekker N.H. Double-stranded RNA under force and torque: Similarities to and striking differences from double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15408–15413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407197111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fathizadeh A., Eslami-Mossallam B., Ejtehadi M.R. Definition of the persistence length in the coarse-grained models of DNA elasticity. Phys. Rev. E. 2012;86 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elmenreich W. Fusion of continuous-valued sensor measurements using confidence-weighted averaging. J. Vib. Control. 2007;13:1303–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herrero-Galán E., Fuentes-Perez M.E., et al. Arias-Gonzalez J.R. Mechanical identities of RNA and DNA double helices unveiled at the single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:122–131. doi: 10.1021/ja3054755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furrer P., Bednar J., et al. Dubochet J. Opposite effect of counterions on the persistence length of nicked and non-nicked DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:711–721. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abels J.A., Moreno-Herrero F., et al. Dekker N.H. Single-molecule measurements of the persistence length of double-stranded RNA. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2737–2744. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma R. EPFL; 2023. cgNA+: A Sequence-dependent Coarse-Grain Model of Double-Stranded Nucleic Acids. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schurr J.M. Temperature-dependence of the bending elastic constant of DNA and extension of the two-state model. Tests and new insights. Biophys. Chem. 2019;251 doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2019.106146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galindo-Murillo R., Robertson J.C., et al. Cheatham T.E., III Assessing the current state of Amber force field modifications for DNA. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2016;12:4114–4127. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dans P.D., Ivani I., et al. Orozco M. How accurate are accurate force-fields for B-DNA? Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4217–4230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kührová P., Mlýnský V., et al. Banáš P. Sensitivity of the RNA structure to ion conditions as probed by molecular dynamics simulations of common canonical RNA duplexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023;63:2133–2146. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., et al. Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 81.González M.A., Abascal J.L.F. The shear viscosity of rigid water models. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132 doi: 10.1063/1.3330544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zarzycki P., Gilbert B. Temperature-dependence of the dielectric relaxation of water using non-polarizable water models. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020;22:1011–1018. doi: 10.1039/c9cp04578c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guillot B. A reappraisal of what we have learnt during three decades of computer simulations on water. J. Mol. Liq. 2002;101:219–260. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vega C., Abascal J.L.F. Simulating water with rigid non-polarizable models: a general perspective. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:19663–19688. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22168j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rami Reddy M., Berkowitz M. The dielectric constant of SPC/E water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;155:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Markesteijn A.P., Hartkamp R., et al. Westerweel J. A comparison of the value of viscosity for several water models using Poiseuille flow in a nano-channel. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;136 doi: 10.1063/1.3697977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morozova T.I., García N.A., Barrat J.-L. Temperature dependence of thermodynamic, dynamical, and dielectric properties of water models. J. Chem. Phys. 2022;156 doi: 10.1063/5.0079003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mester Z., Panagiotopoulos A.Z. Temperature-dependent solubilities and mean ionic activity coefficients of alkali halides in water from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143 doi: 10.1063/1.4926840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schurr J.M. Effects of sequence changes on the torsion elastic constant and persistence length of DNA. Applications of the two-state model. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:7343–7353. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b05139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bednar J., Furrer P., et al. Stasiak A. Determination of DNA persistence length by cryo-electron microscopy. Separation of the static and dynamic contributions to the apparent persistence length of DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;254:579–594. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vologodskaia M., Vologodskii A. Contribution of the intrinsic curvature to measured DNA persistence length. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:205–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Várnai P., Zakrzewska K. DNA and its counterions: a molecular dynamics study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4269–4280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dršata T., Lankaš F. Multiscale modelling of DNA mechanics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2015;27 doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/27/32/323102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snodin B.E.K., Randisi F., et al. Doye J.P.K. Introducing improved structural properties and salt dependence into a coarse-grained model of DNA. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142 doi: 10.1063/1.4921957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.