This cohort study evaluates prevalence and factors associated with bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in inpatients with asymptomatic bacteriuria with or without altered mental status.

Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in hospitalized patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB)?

Findings

In this 5-year, 68-hospital cohort study of 11 590 hospitalized patients with ASB, only 1.4% developed bacteremia from a presumed urinary source, while 72.2% received empiric antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infection. In the 2126 patients with bacteriuria with altered mental status but no systemic signs of infection, only 0.7% developed bacteremia from a presumed urinary source.

Meaning

These findings suggest that bacteremia from a presumed urinary source was rare in patients with ASB, even those presenting with altered mental status.

Abstract

Importance

Guidelines recommend withholding antibiotics in asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), including among patients with altered mental status (AMS) and no systemic signs of infection. However, ASB treatment remains common.

Objectives

To determine prevalence and factors associated with bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in inpatients with ASB with or without AMS and estimate antibiotics avoided if a 2% risk of bacteremia were used as a threshold to prompt empiric antibiotic treatment of ASB.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study assessed patients hospitalized to nonintensive care with ASB (no immune compromise or concomitant infections) in 68 Michigan hospitals from July 1, 2017, to June 30, 2022. Data were analyzed from August 2022 to January 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was prevalence of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source (ie, positive blood culture with matching organisms within 3 days of urine culture). To determine factors associated with bacteremia, we used multivariable logistic regression models. We estimated each patient’s risk of bacteremia and determined what percentage of patients empirically treated with antibiotics had less than 2% estimated risk of bacteremia.

Results

Of 11 590 hospitalized patients with ASB (median [IQR] age, 78.2 [67.7-86.6] years; 8595 female patients [74.2%]; 2235 African American or Black patients [19.3%], 184 Hispanic patients [1.6%], and 8897 White patients [76.8%]), 8364 (72.2%) received antimicrobial treatment for UTI, and 161 (1.4%) had bacteremia from a presumed urinary source. Only 17 of 2126 patients with AMS but no systemic signs of infection (0.7%) developed bacteremia. On multivariable analysis, male sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.45; 95% CI, 1.02-2.05), hypotension (aOR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.18-2.93), 2 or more systemic inflammatory response criteria (aOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.21-2.46), urinary retention (aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.18-2.96), fatigue (aOR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.08-2.17), log of serum leukocytosis (aOR, 3.38; 95% CI, 2.48-4.61), and pyuria (aOR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.10-5.21) were associated with bacteremia. No single factor was associated with more than 2% risk of bacteremia. If 2% or higher risk of bacteremia were used as a cutoff for empiric antibiotics, antibiotic exposure would have been avoided in 78.4% (6323 of 8064) of empirically treated patients with low risk of bacteremia.

Conclusions and Relevance

In patients with ASB, bacteremia from a presumed urinary source was rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients with AMS. A personalized, risk-based approach to empiric therapy could decrease unnecessary ASB treatment.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most overdiagnosed infections, especially in hospitalized patients, older adults, and catheterized patients.1 Recent data show almost 50% of antibiotic prescriptions for outpatient UTIs are either inappropriate or unnecessary.2 Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is even more common in hospitalized older adults and those presenting with dementia and/or altered mental status (AMS).3,4,5,6,7 AMS remains one of the primary indications for ASB treatment despite guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommending withholding antibiotic treatment in patients with ASB.8

One reason for ASB overtreatment is clinicians’ concern that poor outcomes (eg, bacteremia from UTI) may occur if antibiotics are not started early.9,10 Evidence to guide treatment in these situations are sparse. On the one hand, studies suggest antibiotic delays in patients with bacteremia or severe sepsis may increase mortality.11 In contrast, antibiotic treatment of ASB has not been shown to improve clinical outcomes and is instead associated with increased health care utilization, adverse drug events, and Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI).6,12 Prior studies have suggested that estimating a patient’s risk of an outcome (eg, bacteremia) and then treating with antibiotic therapy if their risk exceeds 2% could balance potential under and overtreatment.13,14 However, there is no validated way to estimate the risk of bacteremia in a hospitalized patient with ASB.

We sought to (1) determine the prevalence of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in a large, multihospital cohort of hospitalized patients with ASB and a subgroup of patients with AMS; (2) examine factors associated with bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in patients with ASB; and (3) estimate antibiotics avoided if a 2% risk of bacteremia were used as a threshold for empiric antibiotic treatment of ASB.

Methods

Study Setting and Design

This cohort study includes data from 68 hospitals (53 urban and 15 rural, including a critical access hospital) in the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium. HMS hospitals range in size from 25 to 1131 beds with a median (IQR) bed size of 275 (151-392). This project was not regulated by the University of Michigan Medical School’s institutional review board, which deemed the work to be quality improvement and thus waived the requirement of informed consent. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was followed.

Patient Selection

This study included a sample of adult patients admitted to nonintensive care unit settings in HMS hospitals with a positive urine culture between July 1, 2017, and June 30, 2022. Patients were consecutively reviewed with the first patient included daily. Patients were ineligible for inclusion if they met any of the following criteria: (1) age younger than 18 years; (2) pregnant and/or breastfeeding; (3) altered urinary tract anatomy, urologic surgery during hospitalization, or urinary stent or nephrostomy tube in place during hospitalization; (4) intensive care unit admission within 3 days before or after urine culture; (5) under hospice care on admission; (6) patient directed discharge; (7) concomitant infection (abstractors excluded any patient with documented antibiotic treatment for a concomitant bacterial infection during the hospital encounter unless the infection was potentially related to the UTI [eg, bacteremia, CDI]); (8) active treatment and/or prophylaxis for UTI on admission; (9) solid organ or bone marrow transplant recipient; (10) HIV with CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm3; (11) neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <0.5 cells/μL on hospital day 1 or 2); or (12) within the 30 days after discharge from index hospitalization already abstracted for that patient.

For this study, patients were excluded if they had specific signs or symptoms of a UTI defined per IDSA ASB guidelines8,16,17,18,19 (Box). Patients with isolated candiduria and Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria were also excluded as candiduria frequently represents colonization or contamination, and Staphylococcus aureus in urine usually represent hematogenous spread20,21 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

Box. Definitions.

Bacteriuria

Bacteriuria or positive urine culture was defined if flagged as abnormal by the hospital. While many hospitals use bacterial growth of 103 or greater with no more than 2 organisms or 102 with E.coli,15 some use alternative definitions.

Signs and Symptoms

Specific Signs or Symptoms of UTI

Nonspecific Signs or Symptoms

Altered mental status with or without dementia, fatigue, falls, functional decline, malaise, change in color or odor of urine, acute or new onset urinary retention, urinary incontinence, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Systemic Signs or Symptoms of Infection

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or leukocytosis or hypotension with systolic blood pressure less than 90.18

Bacteremia

Bacteremia from a presumed urinary source was defined if a patient had a positive blood culture growing at least 1 organism matching the urine culture. To be included, the blood culture had to have no more than 2 pathogens and be obtained within 3 days of the positive urine culture (patients with concomitant infections were excluded).19

Urologic History

Complicated urologic history was defined as a history of nephrolithiasis (kidney stones); urologic surgery in prior 30 days (lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, cystoscopy); prior suprapubic catheter or nephrostomy tube within 30 days; history of urinary obstruction, urinary retention, neurogenic bladder, or urinary incontinence in the 30 days before the hospital encounter.

CDI Events

CDI events were defined in patients with laboratory diagnosis (positive C. difficile polymerase chain reaction and/or glutamate dehydrogenase level with toxin enzyme immunoassay testing) occurring ≥48 hours after urine culture or a new CDI event within 30 days after hospital discharge ascertained via medical record or patient report on 30-day post-discharge phone call.

Duration

Duration of hospitalization was assessed from the day urine culture was performed (urinalysis or urine culture).

Data Collection

As previously described,6,7,22 trained abstractors collected data retrospectively from patient records (eMethods in Supplement 1). Briefly, deidentified data were collected from 90 days before admission until 30 days after discharge or sooner if follow-up was terminated by a major complication (eg, death). Variables collected from the medical record include demographics, signs and symptoms, laboratory findings, vital signs, antibiotic type and duration, and outcomes. Information on signs and symptoms were collected from clinician and nursing documentation 3 days before through 3 days after urine culture collection. Demographics like race, ethnicity, age, and sex were assessed to better understand their association with bacteremia from a presumed urinary source. Thirty-day patient outcomes were collected via medical record review and prospective patient phone call 30 days following hospitalization. Patients who died or were discharged to hospice or another care facility were not eligible for postdischarge phone calls.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was bacteremia from a presumed urinary source (positive blood culture with matching organism within 3 days of urine culture). We assessed for possible variables associated with bacteremia including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), complicated urologic history, comorbidities, presence of dementia or AMS, nonspecific signs or symptoms (eg, foul smelling urine, fatigue) and relevant laboratory results (ie, elevated peripheral white blood cell [WBC] count, urinalysis parameters, and urine culture results). Secondary outcomes included duration of hospitalization after urine culture and 30-day CDI event, mortality, readmission, and/or emergency department visit.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the prevalence of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source in all patients and in a subgroup of patients with AMS with or without dementia. We assessed variables associated with bacteremia initially in a bivariable analysis using χ2 tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. We treated age as a linear variable and BMI as a categorical variable. Missing variables (urine WBC, leukocyte esterase, serum leukocytosis, BMI) were imputed using 10-fold multiple imputation. For those with a urinalysis, we assessed variables associated with bacteremia in multivariable logistic regression analysis accounting for clustering within hospitals with a random intercept. WBC counts from urine were provided as ranges rather than exact values, so we categorized this variable and dichotomized it for the final model as less than 25 vs 25 or higher. Serum WBC count was log-transformed to improve model fit. Age was modeled linearly. We retained variables in the final multivariable model that were significant or that were observed to have a confounding effect on the association between another variable and risk of bacteremia. We expressed results as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs, using a 2-sided P value less than .05 to indicate significance, although log odds ratios were used in the figure to preserve spatial relationships between variables. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data were analyzed from August 2022 to January 2023.

Based on the multivariable model, we next calculated mean estimated probability of bacteremia for each patient using various combinations of factors including sex, symptoms such as urinary retention and fatigue, clinical signs such as tachycardia, and laboratory markers such as WBC thresholds and presence of pyuria on urinalysis. Using a 2% risk of bacteremia as a cutoff for whether a patient should receive empiric antibiotics or not, we first assessed the estimated risk of bacteremia for each patient in our cohort. For patients below 2% risk, we then calculated—compared with their actual antibiotic treatment—how many patients could have avoided antibiotic therapy for ASB. Here, empiric therapy is defined as any antibiotic therapy on the day the urine culture was sent or the day after.

Results

Baseline Demographics

Of 11 590 hospitalized patients with ASB (median [IQR] age, 78.2 [67.7-86.6] years); 8595 female patients [74.2%]; 2235 African American/Black patients [19.3%], 184 Hispanic patients [1.6%], and 8897 White patients [76.8%]), 8364 (72.2%) received antimicrobial treatment for UTI, while only 161 (1.4%) developed bacteremia from a presumed urinary source. Demographics of the entire cohort are described in Table 1. Nearly half (5059 patients [43.6%]) had AMS, 3210 (27.7%) had dementia, 1761 (15.2%) had an indwelling urinary catheter, 6323 (54.6%) had complicated urologic history, 11 039 (95.2%) had a urinalysis test (individual urinalysis parameters further described in Table 1), and 3589 (31.0%) had blood cultures obtained within 3 days of urine cultures. Of blood cultures, 401 of 3589 (11.2%) were obtained before the urine culture, 2836 of 3589 (79%) were obtained the same day, and 487 of 3589 (13.6%) were obtained after the urine culture. Patients who did not receive blood cultures had a significantly lower prevalence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), hypotension, tachycardia, and leukocytosis than those who had blood cultures (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographics, Risk Factors, and Outcomes in Patients With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria.

| Risk factor | Bacteremia from a presumed urinary source, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without (n = 11 429) | With (n = 161) | ||

| Age | |||

| Median (IQR) | 78.2 (67.7-86.6) | 79.5 (72.2-88.2) | .02 |

| ≥65 y | 9123 (79.8) | 140 (87.0) | .02 |

| ≥75 y | 6709 (58.7) | 107 (66.5) | .05 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2931 (25.6) | 64 (39.8) | <.001 |

| Female | 8498 (74.4) | 97 (60.2) | |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 28 (0.2) | 0 (0) | .64 |

| Asian | 51 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | |

| African American/Black | 2210 (19.3) | 25 (15.5) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 23 (0.2) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| White | 8765 (76.7) | 132 (82.0) | |

| Unknown | 352 (3.1) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 183 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | .11 |

| Non-Hispanic | 9737 (85.2) | 132 (82.0) | |

| Unknown | 1509(13.2) | 28 (16.4) | |

| BMIa | |||

| ≤18.5 | 711 (6.4) | 9 (5.7) | .24 |

| 18.6-25 | 3654 (32.8) | 64 (40.5) | |

| 25.1-30 | 3042 (27.3) | 39 (24.7) | |

| >30 | 3722 (33.4) | 46 (29.1) | |

| Vital signs on day of culture | |||

| Hypotension (SBP <90) | 840 (7.3) | 28 (17.4) | <.001 |

| Heart rate >90 bpm | 5212 (45.6) | 100 (62.1) | <.001 |

| ≥2 SIRS criteria | 3340 (29.2) | 87 (54.0) | <.001 |

| Nonspecific symptomsb | |||

| No dementia nor AMS | 5443 (47.6) | 66 (41.0) | .01 |

| Dementia, no AMS | 1016 (8.9) | 6 (3.7) | |

| AMS, no dementia | 2821 (24.7) | 50 (31.1) | |

| AMS and dementia | 2149 (18.8) | 39 (24.2) | |

| Change in urine color or character | 2134 (18.7) | 43 (26.7) | .01 |

| Falls | 2091 (18.3) | 26 (16.1) | .48 |

| Fatigue (new or worsening) | 3053 (26.7) | 59 (36.6) | .005 |

| Functional decline (new or worsening) | 904 (7.9) | 22 (13.7) | .008 |

| Malaise (new or worsening) | 676 (5.9) | 13 (8.1) | .25 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 2297 (20.1) | 34 (21.1) | .75 |

| New urinary incontinence | 2642 (23.1) | 42 (26.1) | .38 |

| New urinary retention | 884 (7.7) | 26 (16.1) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1945 (17.0) | 19 (11.8) | .08 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Indwelling catheter present | 1729 (15.1) | 32 (19.9) | .10 |

| Complicated urologic history in past 30 dc | 6214 (54.4) | 109 (67.7) | <.001 |

| Kidney stones | 185 (3.0) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Urologic surgery | 81 (1.3) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Urinary obstruction | 199 (3.2) | 12 (11.0) | |

| Urinary retention | 1979 (31.8) | 44 (40.4) | |

| Urinary incontinence | 4900 (78.8) | 76 (69.7) | |

| Diabetes | 4422 (38.7) | 67 (41.6) | .45 |

| Moderate to severe chronic kidney disease | 4709 (41.2) | 87 (54.0) | .001 |

| Immunosuppression | 380 (3.3) | 5 (3.1) | .88 |

| Hemodialysis | 190 (1.7) | 3 (1.9) | .75 |

| Cancer history | 2441 (21.4) | 40 (24.8) | .28 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3086 (27.0) | 42 (26.1) | .80 |

| Liver disease | 754 (6.6) | 9 (5.6) | .61 |

| Spinal cord injury | 171 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | .74 |

| Coming from SNF, SAR, LTAC, or similar | 2591 (22.7) | 28 (17.4) | .11 |

| Urinalysis on day of or before urine culture | |||

| Any | 10 888 (95.3) | 151 (93.8) | .38 |

| Pyuria | |||

| 0-5 WBCs/hpf | 1421 (13.3) | 9 (6.0) | <.001 |

| 6-10 WBCs/hpf | 1246 (11.6) | 5 (3.3) | |

| 11-25 WBCs/hpf | 1741 (16.3) | 8 (5.3) | |

| ≥26 WBCs/hpf | 6301 (58.8) | 128 (85.3) | |

| Leukocyte esterase | |||

| Absent | 2136 (18.7) | 23 (14.3) | .15 |

| Any | 9293 (81.3) | 138 (85.7) | |

| >1+ | 8271 (72.4) | 133 (82.6) | .004 |

| >2+ | 6600 (57.7) | 117 (72.7) | <.001 |

| Nitrite | |||

| Positive | 4018 (36.9) | 46 (30.5) | .10 |

| Serum WBC | |||

| <10 000/μL (Reference) | 6914 (62.4) | 40 (25.2) | <.001 |

| 10 001/μL-15 000/μL | 2974 (26.9) | 61 (38.4) | |

| >15 001/μL | 1187 (10.7) | 58 (36.5) | |

| Urine pathogens | |||

| Escherichia coli | 5670 (49.6) | 109 (67.7) | <.001 |

| Klebsiella spp | 1890 (16.5) | 28 (17.4) | .77 |

| Enterococcus spp | 1287 (11.3) | 8 (5.0) | .01 |

| Proteus spp | 830 (7.3) | 12 (7.4) | .93 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 552 (4.8) | 4 (2.5) | .17 |

| Enterobacter spp | 344 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) | .10 |

| Citrobacter spp | 295 (2.6) | 1 (0.6) | .12 |

| ≥2 bacteria | 1512 (13.2) | 21 (13.0) | .94 |

| Outcomes | |||

| 30-d mortality | 519 (4.5) | 15 (9.3) | .004 |

| 30-d readmission | 1888 (16.5) | 23 (14.3) | .48 |

| 30-d ED visit | 1257 (11.0) | 16 (9.9) | .669 |

| CDI event at 30 d | 97 (0.8) | 0 (0) | .647 |

| Duration of hospitalization, median (IQR) | 4 (3-6) | 6 (4-7) | <.001 |

| Receipt of antibiotics the day of or day after urine culture, | 8207 (71.8) | 157 (97.5) | <.001 |

| Total antibiotic duration among those on antibiotics day of culture or day after, median (IQR) | 6 (4-8) | 13 (9-15) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AMS, Altered mental status; bpm, beats per minute; BMI, Body Mass Index; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; ED, emergency department; hpf, high-powered field; LTAC, long-term acute care facility; SAR, subacute rehabilitation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SNF, skilled nursing facility; spp, several species; WBC, white blood cells.

Body mass index is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Symptoms include those documented in medical record at any point in the 3 days prior through 3 days after urine culture collection.

Complicated urologic history defined as a history of nephrolithiasis (kidney stones), urologic surgery in prior 30 days (new suprapubic catheter or nephrostomy tube placement, lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, cystoscopy), urinary obstruction, urinary retention or neurogenic bladder, urinary incontinence in the 30 days before the hospital encounter.

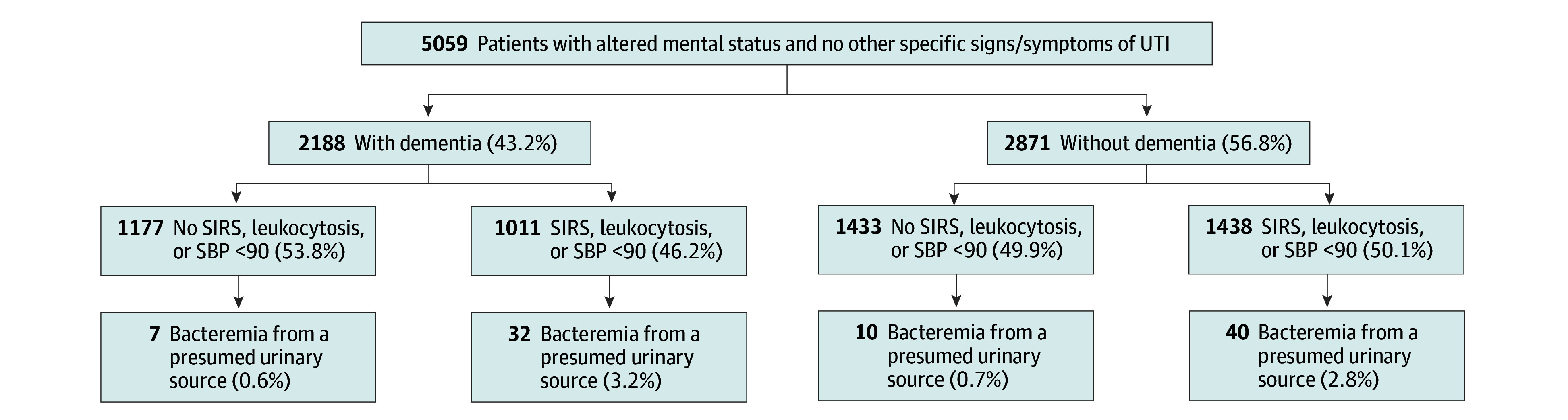

Patients With AMS

Among patients with ASB, 5059 (43.6%) had AMS (Figure). Of these, 89 (1.8%) were found to have bacteremia from a presumed urinary source (vs 72 [1.1%] in patients without AMS). Risk of bacteremia in patients with AMS differed 4-fold based on whether they had systemic signs of infection (ie, evidence of SIRS or leukocytosis): 0.7% (17 of 2610) for patients without systemic signs of infection (number needed to treat, 154) vs 2.9% (72 of 2449) for patients with systemic signs of infection (number needed to treat, 34). Differences based on whether patients had dementia are shown in the Figure.

Figure. Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source Among Hospitalized Patients With Bacteriuria and Altered Mental Status With or Without Dementia.

SBP indicates systolic blood pressure; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Variables and Outcomes Associated With Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source

In unadjusted comparisons, patients with ASB who developed bacteremia from a presumed urinary source were older (median [IQR] age, 79.5 [72.2-88.2] years) than patients who did not develop bacteremia (median [IQR] age, 78.2 [67.7-86.6] years; z score, 2.32; P = .02). Symptoms or comorbidities associated with developing bacteremia from a presumed urinary source included presentation with AMS with or without dementia, complicated urologic history, indwelling catheter, change in urine characteristics, fatigue, functional decline, and urinary retention (see Table 1 for details). Diagnostic findings associated with development of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source included: serum leukocytosis, elevated urinalysis parameters (ie, pyuria or leukocyte esterase), and growth of Escherichia coli (compared with other pathogens) (Table 1).

Patients with ASB who developed bacteremia from a presumed urinary source had higher unadjusted mortality (9.3% vs 4.5%; χ21 = 8.24; P = .004) and median (IQR) duration of hospitalization after urine culture (6 [4-7] vs 4 [3-6] days; z score, 7.08; P < .001) than those without bacteremia. Other outcomes including 30-day readmission, 30-day ED visit, and CDI event at 30 days were similar between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Adjusted Analysis

On multivariable analyses accounting for hospital clustering, we found that male sex (aOR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.02-2.05), hypotension (aOR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.18-2.93), 2 or more SIRS criteria (aOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.21-2.46), urinary retention (aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.18-2.96), fatigue (aOR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.08-2.17), log of serum leukocytosis (aOR, 3.38; 95% CI, 2.48-4.61), and pyuria with more than 25 WBC/hpf on urinalysis (aOR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.10-5.21) were associated with bacteremia from a presumed urinary source (Table 2; eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). In contrast, older age, AMS, dementia, and change in urine were not associated with a higher risk for bacteremia from a presumed urinary source (Table 2; eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Risk Factors for Bacteremia in Hospitalized Adults With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Multivariable Model.

| Variable (n = 11 039) | No. (%) | aOR (95% CI) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 78.3 (67.9-86.6) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .09 |

| Male sex | 2851 (25.8%) | 1.45 (1.02-2.05) | .04 |

| Hypotension (SBP<90) | 828 (7.5%) | 1.86 (1.18-2.93) | .008 |

| ≥2 SIRS criteria | 3315 (30.0%) | 1.72 (1.21-2.46) | .003 |

| Dementia without AMS | 4846 (43.9%) | 1.38 (0.97-1.96) | .08 |

| AMS (with or without dementia) | 975 (8.8%) | 0.5 (0.21-1.18) | .11 |

| Change in urine color or character | 2082 (18.9%) | 1.36 (0.92-2.02) | .12 |

| Fatigue | 2985 (27.0%) | 1.53 (1.08-2.17) | .02 |

| Urinary retention | 860 (7.8%) | 1.87 (1.18-2.96) | .01 |

| UA WBC/hpf >25 | 6477 (58.7%) | 3.31 (2.10-5.21) | <.001 |

| Log serum WBC, median (IQR)b | 2.2 (1.9-2.5) | 3.38 (2.48-4.61) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AMS, altered mental status; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; hpf, high-powered field; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; UA, Urinalysis; WBC, white blood cells.

P < .05 was considered significant.

Log serum WBC: A 1 unit increase in log WBC is exp (log (WBC) +1) – exp (log (WBC)).

Estimated Risk of Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source

In the absence of other findings, no single nonspecific sign or symptom (eg, AMS) or comorbidity conferred a 2% or greater risk of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source. The mean estimated probability of having bacteremia from a presumed urinary source ranged from 0.09% to 16.18% across combinations of variables (see eTable 2 in Supplement 1). For example, mean (SD) estimated probability of bacteremia in a male patient with ASB presenting with urinary retention (no fatigue or tachycardia), serum leukocytosis (>20 000/mL), and less than 25 WBCs on urinalysis was 16.18% (6.4%). In contrast, the mean (SD) estimated probability of bacteremia in a female patient with ASB presenting without tachycardia, urinary retention, or fatigue, and with serum WBC less than 5000/mL and pyuria of 25 or lower WBCs on urinalysis was 0.09% (0.004%).

Risk-Stratified Approach to Empiric Antibiotic Therapy

Mean estimated probabilities of bacteremia from a presumed urinary source that were 2% or higher (our prespecified cut off for considering empiric antibiotic treatment) have been highlighted in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. Patients’ actual empiric treatment compared with their recommended treatment if a 2% risk of bacteremia were used to determine empiric treatment is shown in Table 3. Based on these results, using 2% as a cutoff to inform empiric antibiotic use in ASB would have avoided treatment in 6323 patients with very low risk of bacteremia (of whom 0.7% [44 of 6323] had bacteremia) and empirically treated an additional 206 patients with higher risk for bacteremia (of whom 1 [0.5%] developed bacteremia).

Table 3. Receipt of Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Patients With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Stratified by 2% Risk for Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source.

| Receipt of antibiotics | Estimated risk of bacteremia, % (No.) | |

|---|---|---|

| <2% (n = 9092) | ≥2% (n = 1947) | |

| Received on day of or day after urine culture obtained | 69.5% (6323) | 89.4% (1741) |

| Did not receive on day of or day after urine culture | 30.5% (2769) | 10.6% (206) |

Discussion

In this 68-hospital study of 11 590 hospitalized patients with ASB, 1.4% had bacteremia from a presumed urinary source and only 0.7% of patients with AMS and no systemic signs of infection did. No single risk factor conferred a 2% or greater risk of bacteremia. Specifically, older age, AMS, dementia, and change in urine character were not associated with bacteremia. These data reinforce prior evidence highlighting the poor yield of urine and blood cultures among hospitalized patients without systemic signs of infection and support not empirically treating patients with AMS and no systemic signs of infection.23,24,25

Our study highlights that bacteremia in adult inpatients with ASB is rare, compared with estimates as high as in 24% to 56% in symptomatic patients.26,27 The probability of bacteremia varies widely based on individual risk factors, clinical presentation, and laboratory findings. We found that the highest risk group had a 16.2% mean estimated probability of bacteremia as compared with 0.09% in the lowest risk group. Our study also adds data on laboratory markers that help identify patients at risk for bacteremia. Specifically, patients without specific signs or symptoms of UTI who developed bacteremia were twice as likely to have pyuria with 25 or greater WBCs on urinalysis and also more likely to have serum leukocytosis greater than 10 000/μL. Notably, no single characteristic conferred 2% or greater risk of bacteremia; rather, patients at elevated risk generally had multiple diagnostic findings, comorbidities, or symptoms.

IDSA guidelines for ASB highlight the dearth of evidence on whether antimicrobial therapy is beneficial for bacteriuria in patients with delirium or AMS in the absence of specific signs or symptoms of UTI.8 The guidelines suggest a strategy of watchful waiting in patients with AMS and no systemic signs of infection while recommending empiric antibiotic therapy in patients with systemic signs of infection. Our findings support this strategy, as patients with systemic signs of possible infection were significantly more likely than those without systemic signs of infection (2.9% vs 0.7%) to develop bacteremia. To obtain a thorough picture of a patient’s clinical condition, we used a 3-day infection window for assessing signs and symptoms and capturing blood culture data consistent with national guidance.28 Our data also highlight negligible rates of bacteremia in patients with AMS in the absence of SIRS, hypotension, or leukocytosis, supporting the safety of deferring empiric antibiotic therapy in this group. Moving forward, interventions that provide absolute risks personalized to a patient’s presenting signs and symptoms could be one way to inform evidence-based empiric antibiotic use—or avoidance. In our analyses, a risk-based approach would reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure in almost 70% of patients with low risk of bacteremia.

Little scientific evidence exists on risk factors and epidemiology of bacteremia from a urinary source, especially in older adults.29 Prior studies have shown that diabetes, immunosuppression, catheterization, and shaking chills are independent risk factors for bacteremia from a urinary source.30,31,32 In our analysis, patients with diabetes, immunosuppression, and catheterization were not at higher risk for bacteremia in the absence of specific signs or symptoms of UTI. This discrepancy could indicate those risk factors are more prominent in symptomatic patients—a group we excluded. Additionally, none of these studies investigated specific urinalysis pyuria thresholds.

Implications

Our study has important implications for risk stratifying inpatients with ASB. First, these data provide assurance that history of dementia alone is not a risk factor for bacteremia, likely because ASB is so common in this group. Second, if patients have altered mentation and cannot attest to having specific signs or symptoms of UTI, clinicians should assess for SIRS, leukocytosis, and pyuria when deciding who may possibly benefit from empiric antibiotic treatment. If the patient with ASB does not have systemic signs of infection, they have a very low risk of bacteremia from a urinary source. Finally, moving forward, a validated UTI risk calculator may help determine the need for empiric antibiotic therapy in patients with positive urine cultures and could improve the precision of stewardship interventions. Using these personalized risk estimates would allow us to decrease unnecessary ASB treatment without substantially delaying early empiric therapy in those at highest risk of bacteremia.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, this was an observational study dependent on presence of positive urine culture and documentation of signs and symptoms in the medical record. Second, we excluded concomitant infections, and hence, may not have captured the full scope of ASB in hospitalized patients. Third, we do not have data related to varying methods of diagnosing CDI events or nuances of urine culture reporting across hospitals. Fourth, our study only captures bacteremia in patients with blood and urine cultures growing the same organism within the 3-day infection window, so it may miss patients for whom blood or urine cultures were not obtained or were drawn after antibiotic initiation. Without systematically drawing blood cultures on all patients, it is not possible to determine the true prevalence of bacteremia in this population, but our data reflect clinical experience. Similarly, although we exclude patients with documented concomitant infections, we cannot be assured that all bacteremia was from a urinary source. Additionally, severely immunocompromised patients and those in intensive care units were excluded, where the risk or benefit calculation may be different. In real life, decisions are often made before urine culture results are known (eg, based on urinalyses); thus, for a population of all-comers, we over-estimated the risk of bacteremia.

Conclusions

In our multihospital cohort of 11 590 hospitalized patients with ASB, bacteremia from a presumed urinary source was rare. The risk of bacteremia in patients presenting with AMS was negligible in the absence of systemic signs of infection (eg, leukocytosis or SIRS). A personalized, risk-based approach to empiric antibiotic therapy in patients without specific signs or symptoms of a UTI could decrease unnecessary ASB treatment without delaying early empiric therapy in those at highest risk of bacteremia.

eFigure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Inclusion

eMethods. Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Collaborative Data Curation Methods

eTable 1. Baseline Demographics and Risk Factors in Patients With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB)

eFigure 2. Risk Factors for Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source in Hospitalized Adults With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Multivariable Model

eTable 2. Estimated Probabilities (Expressed as a %) by Patient Subgroups in Ascending Order of Risk

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(8):844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark AW, Durkin MJ, Olsen MA, et al. Rural-urban differences in antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(12):1437-1444. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakih MG, Advani SD, Vaughn VM. Diagnosis of urinary tract infections: need for a reflective rather than reflexive approach. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(7):834-835. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advani SD, Gao CA, Datta R, et al. Knowledge and practices of physicians and nurses related to urine cultures in catheterized patients: an assessment of adherence to IDSA guidelines. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(8):ofz305. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Advani SD, Schmader KE, Mody L. Clin-Star corner: what’s new at the interface of geriatrics, infectious diseases, and antimicrobial stewardship. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(8):2214-2218. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petty LA, Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, et al. Risk factors and outcomes associated with treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1519-1527. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petty LA, Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, et al. Assessment of testing and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria initiated in the emergency department. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(12):ofaa537. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korenstein D, Scherer LD, Foy A, et al. Clinician attitudes and beliefs associated with more aggressive diagnostic testing. Am J Med. 2022;135(7):e182-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baghdadi JD, Korenstein D, Pineles L, et al. Exploration of primary care clinician attitudes and cognitive characteristics associated with prescribing antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214268. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman H, et al. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all cause mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019;364:l525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughn VM, Chopra V. Revisiting the panculture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):236-239. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunting-Early TE, Shaikh N, Woo L, Cooper CS, Figueroa TE. The need for improved detection of urinary tract infections in young children. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Hum SW, et al. Development and validation of a calculator for estimating the probability of urinary tract infection in young febrile children. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(6):550-556. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2018 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(6):813-816. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: review and discussion of the IDSA guidelines. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28(suppl 1):S42-S48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Society of Nephrology; American Geriatric Society . Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654. doi: 10.1086/427507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gando S, Shiraishi A, Abe T, et al. ; Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) Sepsis Prognostication in Intensive Care Unit and Emergency Room (SPICE) (JAAM SPICE) Study Group . The SIRS criteria have better performance for predicting infection than qSOFA scores in the emergency department. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64314-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima S, Hagiya H, Fujita K, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of polymicrobial bacteremia: a retrospective, multicenter study. Infection. 2022;50(5):1233-1242. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01799-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajdács M, Dóczi I, Ábrók M, Lázár A, Burián K. Epidemiology of candiduria and Candida urinary tract infections in inpatients and outpatients: results from a 10-year retrospective survey. Cent European J Urol. 2019;72(2):209-214. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2019.1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chihara S, Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. Staphylococcus aureus bacteriuria as a prognosticator for outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaughn VM, Gandhi TN, Hofer TP, et al. A statewide collaborative quality initiative to improve antibiotic duration and outcomes in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(3):460-467. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leis JA, Gold WL, Daneman N, Shojania K, McGeer A. Downstream impact of urine cultures ordered without indication at two acute care teaching hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(10):1113-1114. doi: 10.1086/673151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mozafarihashjin M, Leis JA, Maze Dit Mieusement L, et al. Safety, effectiveness and sustainability of a laboratory intervention to de-adopt culture of midstream urine samples among hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(1):43-50. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piggott KL, Trimble J, Leis JA. Reducing unnecessary urine culture testing in residents of long term care facilities. BMJ. 2023;382:e075566. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-075566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegman-Igra Y, Fourer B, Orni-Wasserlauf R, et al. Reappraisal of community-acquired bacteremia: a proposal of a new classification for the spectrum of acquisition of bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(11):1431-1439. doi: 10.1086/339809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lark RL, Saint S, Chenoweth C, Zemencuk JK, Lipsky BA, Plorde JJ. Four-year prospective evaluation of community-acquired bacteremia: epidemiology, microbiology, and patient outcome. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;41(1-2):15-22. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00284-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Identifying healthcare-associated infections (HAI) for NHSN surveillance. Accessed January 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/2psc_identifyinghais_nhsncurrent.pdf

- 29.Peach BC, Garvan GJ, Garvan CS, Cimiotti JP. Risk factors for urosepsis in older adults: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. Published online April 6, 2016. doi: 10.1177/2333721416638980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lalueza A, Sanz-Trepiana L, Bermejo N, et al. Risk factors for bacteremia in urinary tract infections attended in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(1):41-50. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1576-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahagon Y, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Prevalence and predictive features of bacteremic urinary tract infection in emergency department patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26(5):349-352. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0287-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shigemura K, Tanaka K, Osawa K, Arakawa S, Miyake H, Fujisawa M. Clinical factors associated with shock in bacteremic UTI. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(3):653-657. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0449-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Inclusion

eMethods. Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Collaborative Data Curation Methods

eTable 1. Baseline Demographics and Risk Factors in Patients With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB)

eFigure 2. Risk Factors for Bacteremia From a Presumed Urinary Source in Hospitalized Adults With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Multivariable Model

eTable 2. Estimated Probabilities (Expressed as a %) by Patient Subgroups in Ascending Order of Risk

Data Sharing Statement