Abstract

Background

Regular physical activity elicits multiple health benefits in the prevention and management of chronic diseases. We examined the mortality risks associated with levels of leisure-time aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans among US adults.

Methods

We analysed data from the 1999 to 2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey with linked mortality data obtained through 2006. Cox proportional HRs with 95% CIs were estimated to assess risks for all-causes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality associated with aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity.

Results

Of 10 535 participants, 665 died (233 deaths from CVD) during an average of 4.8-year follow-up. Compared with participants who were physically inactive, the adjusted HR for all-cause mortality was 0.64 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.79) among those who were physically active (engaging in ≥150 min/week of the equivalent moderate-intensity physical activity) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.97) among those who were insufficiently active (engaging in >0 to <150 min/week of the equivalent moderate-intensity physical activity). The adjusted HR for CVD mortality was 0.57 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.97) among participants who were insufficiently active and 0.69 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.12) among those who were physically active. Among adults who were insufficiently active, the adjusted HR for all-cause mortality was 44% lower by engaging in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week.

Conclusions

Engaging in aerobic physical activity ranging from insufficient activity to meeting the 2008 Guidelines reduces the risk of premature mortality among US adults. Engaging in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week may provide additional benefits among insufficiently active adults.

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of regular physical activity on physical and mental well-being have been studied extensively. These benefits include promoting cardiorespiratory fitness and physical functioning; maintaining healthy weight; improving insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control; reducing risks for cognitive decline and chronic conditions including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer and depression; and improving self-perceived health and health-related quality of life.1-5 Moreover, the association between physical activity and risk of mortality has been reported previously6-9 and regular physical activity has been shown to be inversely associated with all-cause mortality in men and women.10 11

The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2008 Guidelines) released by the US Department of Health and Human Services recommends that all adults engage in a minimum of 150 min/week of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75 min/week of vigorous-intensity physical activity or an equivalent combination of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity.12 In addition, adults should perform two or more times a week of muscle-strengthening activity of moderate-intensity or high-intensity that involve all major muscle groups.12

Currently, evidence of the relationship between meeting the 2008 Guidelines and mortality risks is limited. A study using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) showed that the mortality risk from all causes decreased significantly among adults who adhered to the minimum 150 min/week of physical activity in accordance with the 2008 Guidelines.13 It is not clear whether engaging in muscle-strengthening activity can provide an additional mortality risk reduction beyond that derived from aerobic physical activity among this population.

Using a nationally representative sample of US adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)-linked mortality study, we examined the mortality risks associated with levels of leisure-time aerobic physical activity, muscle-strengthening activity and the combination of these activities based on the 2008 Guidelines.

METHODS

Study design

From 1999 to 2004, three 2-year nationally representative samples of the non-institutionalised US population were recruited to participate in NHANES. During the baseline survey, a total of 14 213 adults aged ≥20 years were interviewed at home and then invited to a mobile examination centre to undergo various physical examinations and to provide blood samples for laboratory tests. The NHANES-linked mortality data were obtained by follow-up through 31 December 2006. A more detailed description of the NHANES survey design and methods are reported elsewhere.14 The response rates for examined samples in the 1999–2004 NHANES ranged from 76% to 80%. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Leisure-time aerobic physical activity

Participants’ leisure-time aerobic physical activity was assessed by utilising the following questions: (1) “Over the past 30 days, did you do any moderate-intensity activities for at least 10 min that cause only light sweating or a slight to moderate increase in breathing or heart rate? Some examples are brisk walking, bicycling for pleasure, golf and dancing,” and (2) “Over the past 30 days, did you do any vigorous-intensity activities for at least 10 min that cause heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate? Some examples are running, lap swimming, aerobics classes or fast bicycling.” Participants with an affirmative answer to either question were then asked about specific moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity leisure-time activities, how many times per week they participated in these activities and the average duration each time they engaged in the activity. We calculated the average minutes per week that participants reported participating in moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity physical activity. The minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity were doubled and added to the minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity to compute an equivalent combination of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity (1 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity is equivalent to 2 min of moderate-intensity physical activity). Based on the 2008 Guidelines,12 we created three levels of physical activity: (1) physically active if they reported ≥150 min/week of moderate-intensity activity or ≥75 min/week of vigorous-intensity activity or ≥150 min/week of an equivalent combination (≥150 min/week); (2) insufficiently active if they reported some physical activity but not enough to meet the active definition (>0 to <150 min/week) and (3) inactive if they reported no moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Muscle-strengthening activity

Muscle-strengthening activity was assessed by utilising the following questions: (1) “Over the past 30 days, did you do any physical activities specifically designed to strengthen your muscles such as lifting weights, push-ups or sit-ups?” and (2) “Over the past 30 days, how many times did you do these physical activities?” Following the 2008 Guidelines,12 we dichotomised the muscle-strengthening activity into two groups that are based on meeting the frequency requirement of the muscle-strengthening activity guideline: ≥2 times/week and <2 times/week.

Linked mortality data

The mortality data for the 1999–2004 NHANES survey participants were obtained by matching participants’ identifying information to the National Death Index to determine their survival status through 31 December 2006. The probabilistic matching between NHANES and National Death Index data was performed by the National Center for Health Statistics in CDC. Based on the standardised list of 113 causes of death identified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10th revision), we computed the number of deaths from all causes and from CVD (ICD-10th revision: I00-I78 and I80-I99).

Covariates

Based on existing literature, the following variables were selected as confounding variables measured at the baseline survey. The demographic characteristics included sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican-American and other) and education (<high school graduate, high school graduate/equivalent and >high school diploma). Lifestyle-related behaviours included smoking (current, former, never-smoked) and heavy alcohol drinking (yes/no). Current smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one’s life and still smoking, former smoking as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one’s life but stopped and never-smoked as having smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in one’s life. Heavy alcohol drinking was defined as having an average of >2 drinks/day in men and >1 drink/day in women during the previous 12 months. Body mass index was calculated as measured weight (kg) divided by square of height (m2) and categorised as <25.0, 25.0–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2.15 Laboratory biomarkers included serum concentrations of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and C reactive protein (<0.3, ≥0.3 mg/dL). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.16 Pre-existing comorbidities at baseline included a history of CVD including coronary artery disease, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and stroke (yes/no); diabetes (categorised as physician-diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes (glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5%), prediabetes (HbA1c 5.7–6.4%) and no diabetes); hypertension (categorised as hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or taking antihypertension medications), prehypertension (systolic blood pressure 120–139 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure 80–89 mm Hg) and no hypertension)17; arthritis (yes/no); current asthma (yes/no); cancer (yes/no) and disability (yes/no). Disability was defined as participants who reported being limited in any way in any activities (such as being kept from working or limited in the kind or amount of work or having difficulty walking without using any special equipment) because of a physical, mental or emotional problem.

Statistical analysis

We estimated age-adjusted mortality rates with 95% CIs stratified by patterns of meeting the 2008 Guidelines. Cox proportional HRs with 95% CIs were estimated to assess risks for all-cause and CVD mortality associated with levels of physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity. In the Cox proportional hazard regression analyses, we used age as the time scale. Age at baseline and at event (at death or at the end of follow-up) were used to account for left truncation (ie, participants entered the cohort at different ages).18 19 We tested the proportional hazards assumption by regressing Schoenfeld residuals corresponding to each level of covariates on follow-up time to identify non-zero slopes,20 which showed no slopes were statistically significant from zero (p>0.05). SUDAAN (Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data, Release V.10.0.1, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA) was used in all analyses to account for the complex sampling design.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Of 14 213 survey participants aged ≥20 years, we excluded 833 women who reported being pregnant, 43 adults who had missing responses to the questions on leisure-time physical activity or muscle-strengthening activity and 21 adults with unascertained survival status. After further excluding those with missing values for study covariates, 10 535 (5431 men, 5104 women) remained in our analysis as eligible study participants. The mean age of eligible participants was 46 years (median, 44 years). Approximately 73.5% were non-Hispanic white, 9.8% non-Hispanic black, 7.0% Mexican-American and 9.7% of ‘other’ races. About 54.5% of survey participants had attained an education of greater than a high school diploma.

Characteristics of study participants by mortality status

During an average of 4.8-year follow-up, a total of 665 deaths from all causes were recorded including 233 deaths from CVD. Compared with survivors, adults who did not survive to follow-up were more likely to be older, male, less educated and former smokers, to have higher levels of total cholesterol and C reactive protein and a lower level of eGFR and to have histories of chronic physical conditions (except for current asthma) (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics* of adults aged ≥20 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004 by mortality status after an average 4.8-year follow-up period

| Deceased (n=665) |

Survivors (n=9870) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent or mean | (95% CI) | Percent or mean | (95% CI) | p Value† | |

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| 20–39 | 3274 | 5.9 | (3.2 to 10.5) | 40.2 | (38.5 to 41.9) | |

| 40–59 | 3342 | 21.5 | (17.4 to 26.2) | 39.4 | (38.1 to 40.8) | |

| ≥60 | 3919 | 72.7 | (67.0 to 77.7) | 20.3 | (19.2 to 21.5) | |

| Sex | 0.007 | |||||

| Men | 5431 | 57.6 | (53.0 to 62.0) | 50.1 | (49.2 to 51.1) | |

| Women | 5104 | 42.4 | (38.0 to 47.0) | 49.9 | (48.9 to 50.8) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 5454 | 78.3 | (73.1 to 82.7) | 73.3 | (69.8 to 76.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1901 | 11.4 | (8.7 to 14.8) | 9.7 | (8.0 to 11.8) | |

| Mexican American | 2408 | 3.9 | (2.3 to 6.4) | 7.1 | (5.5 to 9.2) | |

| Other | 772 | 6.4 | (3.7 to 10.9) | 9.9 | (7.7 to 12.5) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||||

| <High school diploma | 3353 | 37.3 | (33.1 to 41.5) | 18.6 | (17.3 to 20.0) | |

| High school graduate | 2516 | 27.4 | (23.5 to 31.8) | 26.2 | (24.6 to 27.9) | |

| >High school diploma | 4666 | 35.3 | (30.8 to 40.1) | 55.2 | (52.9 to 57.4) | |

| Health-related lifestyle factor | ||||||

| Physical activity | <0.001 | |||||

| Inactive | 4604 | 63.9 | (58.9 to 68.7) | 34.2 | (32.5 to 36.0) | |

| Insufficiently active | 2254 | 15.2 | (11.9 to 19.3) | 24.1 | (22.9 to 25.2) | |

| Physically active | 3677 | 20.8 | (17.0 to 25.3) | 41.7 | (39.5 to 43.9) | |

| Muscle-strengthening activity | 0.001 | |||||

| <2 times/week | 8674 | 89.5 | (84.4 to 93.0) | 79.3 | (77.7 to 80.9) | |

| ≥2 times/week | 1861 | 10.5 | (7.0 to 15.6) | 20.7 | (19.1 to 22.3) | |

| Current smoking | 2365 | 26.6 | (21.2 to 32.7) | 25.0 | (23.5 to 26.6) | 0.610 |

| Former smoking | 2891 | 39.6 | (35.1 to 44.3) | 24.4 | (23.0 to 25.9) | <0.001 |

| Heavy drinking | 737 | 8.6 | (5.4 to 13.3) | 8.3 | (7.4 to 9.3) | 0.898 |

| Clinical biomarker | ||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)‡ | 10 535 | 27.7 | (27.0 to 28.3) | 28.1 | (27.9 to 28.4) | 0.196 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL)‡ | 10 535 | 209.0 | (204.2 to 213.7) | 202.6 | (201.3 to 203.9) | 0.014 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL)‡ | 10 535 | 52.1 | (50.0 to 54.2) | 51.8 | (51.2 to 52.4) | 0.768 |

| C reactive protein (mg/dL)‡ | 10 535 | 0.71 | (0.63 to 0.79) | 0.40 | (0.38 to 0.42) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)‡ | 10 535 | 76.7 | (73.6 to 79.9) | 98.6 | (97.7 to 99.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic condition | ||||||

| Hypertension | 4019 | 68.3 | (62.6 to 73.4) | 28.4 | (26.8 to 30.0) | <0.001 |

| Prehypertension | 2964 | 17.1 | (13.6 to 21.2) | 31.0 | (29.8 to 32.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1346 | 22.5 | (19.4 to 26.0) | 8.0 | (7.2 to 8.9) | <0.001 |

| Prediabetes | 1600 | 23.8 | (19.5 to 28.6) | 11.0 | (10.0 to 12.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1144 | 33.0 | (28.9 to 37.5) | 6.9 | (6.1 to 7.8) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 489 | 6.4 | (4.2 to 9.5) | 5.0 | (4.3 to 5.7) | 0.278 |

| Arthritis | 2801 | 46.7 | (41.1 to 52.4) | 21.4 | (20.1 to 22.7) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 960 | 25.9 | (21.7 to 30.6) | 7.4 | (6.8 to 8.1) | <0.001 |

| Disability | 2824 | 54.2 | (50.2 to 58.1) | 21.4 | (20.0 to 23.0) | <0.001 |

Weighed percentage (%) with 95% CI unless otherwise indicated.

χ2 test.

Weighted mean with 95% CI.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

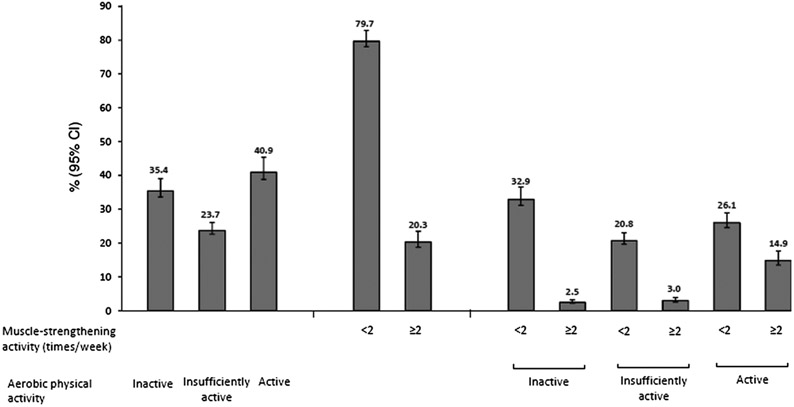

For physical activity, participants who died during the follow-up period were more likely to be physically inactive and less likely to engage in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week than those who survived to the end of 2006 (table 1). During the baseline survey, the percentages of adults who engaged in various levels of aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity are shown in figure 1. Approximately 40.9% of adults were physically active (ie, met the aerobic 2008 Guidelines), 20.3% engaged in the muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week and 14.9% were physically active and engaged in the muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week as well.

Figure 1.

Distribution of adults aged 20 years or older by levels of aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity at baseline among the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants (n=10 535).

Mortality rates and risks by patterns of aerobic physical activity

The age-adjusted mortality rates of all causes were significantly lower among adults who were physically active (4.9/1000 person-years) and who were insufficiently active (6.5/1000 person-years) versus adults who were physically inactive (12.7/1000 person-years, p<0.01, table 2); similarly, the age-adjusted CVD mortality rates were also significantly lower among adults who were physically active (1.5/1000 person-years) and who were insufficiently active (1.6/1000 person-years) versus adults who were physically inactive (4.4/1000 person-years, p<0.01).

Table 2.

HRs for all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality by levels of Leisure-time physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity among US adults who participated in the NHANES 1999–2004 during 4.8-year follow-up period

| Deaths/number at risk* | Mortality rate† |

Model 1‡ |

Model 2§ |

Model 3¶ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | ||

| All-cause mortality | |||||||||

| Aerobic physical activity | |||||||||

| Inactive | 436/4604 | 12.7 | (11.3 to 14.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Insufficiently active | 99/2254 | 6.5 | (4.9 to 8.2) | 0.59 | (0.45 to 0.77) | 0.72** | (0.54 to 0.97) | 0.75** | (0.54 to 1.05) |

| Physically active | 130/3677 | 4.9 | (3.7 to 6.1) | 0.47 | (0.38 to 0.60) | 0.64** | (0.52 to 0.79) | 0.70** | (0.56 to 0.88) |

| Muscle-strengthening activity | |||||||||

| <2 times/week | 605/8674 | 9.1 | (8.2 to 10.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥2 times/week | 60/1861 | 5.4 | (3.1 to 7.8) | 0.68 | (0.46 to 0.99) | 0.87†† | (0.56 to 1.36) | 0.97†† | (0.61 to 1.54) |

| CVD mortality | |||||||||

| Aerobic physical activity | |||||||||

| Inactive | 163/4604 | 4.4 | (3.4 to 5.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Insufficiently active | 27/2254 | 1.6 | (0.9 to 2.3) | 0.45 | (0.28 to 0.72) | 0.57** | (0.34 to 0.97) | 0.53** | (0.30 to 0.94) |

| Physically active | 43/3677 | 1.5 | (1.0 to 2.1) | 0.45 | (0.28 to 0.73) | 0.69** | (0.43 to 1.12) | 0.85** | (0.50 to 1.43) |

| Muscle-strengthening activity | |||||||||

| <2 times/week | 208/8674 | 2.9 | (2.4 to 3.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥2 times/week | 25/1861 | 2.0 | (1.1 to 2.8) | 0.76 | (0.49 to 1.18) | 1.00†† | (0.64 to 1.57) | 1.17†† | (0.67 to 2.04) |

Unweighted numbers.

Age-adjusted, presented as per 1000 person-years.

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education, body weight status, smoking, heavy alcohol drinking, serum concentrations of total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, elevated C reactive protein, eGFR, pre-existing chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, asthma, arthritis, disability and cancer).

Model 3: subanalyses were conducted after excluding deaths that occurred during the first-year follow-up period while controlling for covariates as listed in model 2 (all deaths=577, CVD deaths=196).

With further adjustment for muscle-strengthening activity.

With further adjustment for aerobic physical activity.

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Following adjustment for study covariates including muscle-strengthening activity (model 2, table 2), compared with adults who were physically inactive, those who were physically active had a significantly lower risk for all-cause mortality (reduced by 36%, p<0.001); the risk for CVD mortality was also reduced by 31% but did not reach statistical significance. Participants who were insufficiently active had a 28% (p<0.05) reduced risk for all-cause mortality and 43% (p<0.05) reduced risk for CVD mortality compared with adults who were physically inactive. These associations persisted after excluding deaths that occurred within the first-year follow-up period (model 3, table 2). Similar results were also observed when aerobic physical activity was assessed by computing a metabolic equivalent task (MET)-hour index (data not shown).

Mortality rates and risks by patterns of muscle-strengthening activity

The overall mortality rate was significantly lower among adults who engaged in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week (5.4/1000 vs 9.1/1000 person-years) than among those who did <2 times/week of muscle-strengthening activity (table 2).

Following adjustment for study covariates including aerobic physical activity levels, the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality and CVD mortality did not differ significantly between adults who engaged in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week and those who did not (table 2).

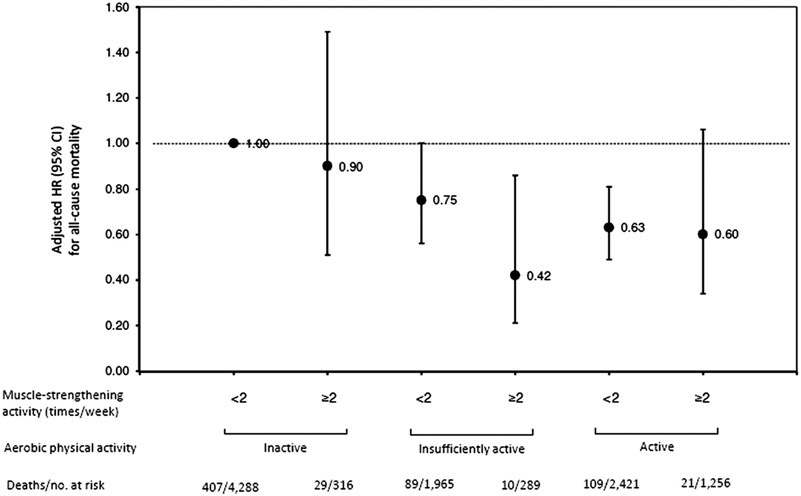

Further stratified analyses by patterns of aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity showed that, among adults who were insufficiently active, the adjusted HR for all-cause mortality was 44% lower among those who engaged in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week compared with those who did not (adjusted HR=0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.86 vs adjusted HR=0.75, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.00, figure 2). However, among adults who were physically active, engaging in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week did not affect the risk of all-cause mortality. Similar results were also observed after excluding deaths that occurred within the first-year follow-up period (model 3, table 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted HRs with 95% CIs for all-cause mortality among participants stratified by aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity. The 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)-linked mortality study..

DISCUSSION

Our results from a large, nationally representative sample support previous findings that meeting the aerobic 2008 Guidelines is associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality.21 Our findings for CVD mortality are also suggestive of a protective association; however, this association was not significant following adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle risk factors and preexistence of major chronic conditions. In addition, our results suggest the insufficient physical activity is also associated with a risk reduction for all-cause and CVD mortality following multivariate adjustment. Although engaging in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week was not significantly associated with all-cause or CVD mortality, it may help reduce the risk of all-cause mortality among adults who were insufficiently active.

To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies that have examined mortality risks associated with meeting the 2008 Guidelines using nationally representative samples. The findings of the current study add to accumulating evidence showing that meeting the 2008 Guidelines exerts an important influence on overall risk of premature mortality of the US adult population, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study based on data from the NHIS.13 Another study also showed that Taiwanese adults who were physically inactive had a 17% increased risk of mortality, whereas those who were active for an average of 92 min/week (or 15 min/day) had a reduction in all-cause mortality of 14% and an increased life expectancy of 3 years.22 Our results further demonstrated that engaging in aerobic physical activity ranging from insufficient activity to the recommended levels reduced the risk for all-cause mortality by 28–36%.

In the current study, we observed lower CVD mortality rates among adults who engaged in aerobic physical activity compared with adults who were physically inactive; the risk of death from CVD was also lower among adults who were insufficiently active than among those who were physically inactive. The protective benefit on CVD mortality of being physically active was insignificant after adjustment for potential confounding factors. This could be due to a small sample size or inadequate statistical power. Some studies suggest that excessive exercise may have adverse cardiovascular effects23-27 and increase mortality risk.28 Because of the relatively small sample size, our study did not examine whether individuals within our physically active group were participating in excessive exercise. Future large longitudinal studies may wish to examine the relationship between excessively high levels of physical activity and the risk of CVD mortality.

Increased muscle strength and muscle mass have been shown to be inversely associated with excessive body fat and abdominal fat29 30 and directly associated with improved insulin sensitivity and metabolic health.31-33 Limited evidence showed that muscle strength was associated with lower all-cause mortality among healthy men or men with hypertension.34 35 However, our results from a nationally representative sample did not show significant benefits by engaging in muscle-strengthening activity at the recommended level in the general population. Nonetheless, our results did show that meeting muscle-strengthening activity guidelines modestly reduced the risk of premature death from all causes among people who, based on their aerobic physical activity, were insufficiently active. In the current study, we found that 23.7% of adults were insufficiently active, but only 3% of adults were insufficiently active and engaged in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week as well. Thus, more efforts are needed to promote muscle-strengthening activity participation among adults who were insufficiently active to reduce mortality risk.

It has been deduced that aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity exert a variety of health benefits, which include promoting weight loss or maintaining a healthy weight, improving glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity, decreasing HbA1c levels, improving cardiorespiratory fitness and reducing risk factors for CVD2 36-39; all these factors may provide underlying mechanisms for reducing CVD mortality risk, thereby reducing total mortality.

Several limitations are noted in this study. First, data on physical activity and some of the covariates were self-reported and subject to recall bias. For example, although self-reported physical activity has been shown to provide valid information regarding moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity in public health surveillance,40-42 a few studies have reported that physical activity levels measured using self-report are overestimated compared to those measured by accelerometer.43 44 This would likely lead to a more conservative estimate of the association between physical activity levels and mortality. Second, the questions on muscle-strengthening activity only provided frequency measurement; information on whether the activities involved the seven major muscle groups as specified in the 2008 Guidelines was not provided, which could result in an overestimation of the prevalence of meeting the muscle-strengthening activity guideline. Third, the mortality data were obtained after a relatively short follow-up period (~4.8 years) resulting in a relatively small number of deaths. Consequently, conducting stratified analyses by muscle-strengthening activity or by more levels of aerobic physical activity proved challenging. Future large cohort studies with longer follow-up periods are warranted to further investigate the benefits of varying levels of aerobic physical activity (eg, using five levels of aerobic physical activity as inactive, 1–59, 60–149, 150–299 and ≥300 min/week or using five levels as inactive, insufficiently active, meeting recommendation for moderate-intensity physical activity only, for vigorous-intensity physical activity only and for moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activities) on reducing mortality risks.

The strength of the current study is that our study was a prospective cohort study that was based on a large, nationally representative survey of the US adult population. In addition, the instrument for measuring physical activity was based on general and individually specified activities, and hence we were able to assess physical activity by computing the average minutes per week and the MET-hour index.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that participation in leisure-time aerobic physical activity ranging from insufficient activity to meeting the 2008 Guidelines is associated with a reduced risk for premature death among adults in the USA. Engaging in muscle-strengthening activity at the recommended level may modestly reduce the risk of premature mortality among adults who were insufficiently active. Currently, despite scientific and media advocacy about physical activity and the health benefits it confers, based on data from the NHIS, only about 43.5% adults met the 2008 Guidelines for aerobic physical activity and 21.9% met the guideline for muscle-strengthening activity in 2008,45 and there was little progress in increasing physical activity among US adults during the period of 1998–2008.45 Therefore, continuing efforts to promote a physically active lifestyle that includes muscle-strengthening activity may help improve the overall health of the population, decrease mortality and ultimately increase life expectancy of the population.

What are the new findings.

Our prospective cohort study provides further evidence to support that meeting the 2008 Guidelines (ie, ≥150 min/week of the equivalent moderate-intensity physical activity) exerts an important influence on overall risk of premature mortality in the US adult population.

Engaging in some physical activity but not sufficient to meet the 2008 Guidelines (ie, >0 to <150 min/week of the equivalent moderate-intensity physical activity) can also reduce the risks for all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality.

Engaging in muscle-strengthening activity ≥2 times/week helps reduce the overall risk of premature mortality among adults who were insufficiently active.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future.

Given a relatively low prevalence of adherence to the 2008 Guidelines in the US population, findings from this study may assist healthcare clinicians and public health professionals to provide appropriate counselling and education on the benefits of physical activity, especially on long-term mortality risk reduction, for patients as well as for the general population.

Healthcare clinicians and public health professionals may also educate and motivate people to participate in muscle-strengthening activity not only for the purpose of improving body function and reducing frailty in the elderly, but also for an overall mortality risk reduction among insufficiently active adults.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:876–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed HM, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, et al. Effects of physical activity on cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:288–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJ, et al. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;44:CD005381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1081–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, et al. The ABC of physical activity for health: a consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sports Sci 2010;28:573–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herman KM, Hopman WM, Vandenkerkhof EG, et al. Physical activity, body mass index and health-related quality of life in Canadian adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:625–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee IM, Skerrett PJ. Physical activity and all-cause mortality: what is the dose-response relation? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:S459–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1382–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabia S, Dugravot A, Kivimaki M, et al. Effect of intensity and type of physical activity on mortality: results from the Whitehall II cohort study. Am J Public Health 2012;102:698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lollgen H, Bockenhoff A, Knapp G. Physical activity and all-cause mortality: an updated meta-analysis with different intensity categories. Int J Sports Med 2009;30:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nocon M, Hiemann T, Muller-Riemenschneider F, et al. Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008;15:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Depatment of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx (accessed 30 Mar 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenborn CA, Stommel M. Adherence to the 2008 adult physical activity guidelines and mortality risk. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm (accessed 30 Mar 2013).

- 15.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.htm (accessed 30 Mar 2013).

- 16.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the joint National committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pencina MJ, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB. Choice of time scale and its effect on significance of predictors in longitudinal studies. Stat Med 2007;26:1343–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards test and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report 2008. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/committeereport.aspx (accessed 30 Mar 2013).

- 22.Wen CP, Wai JP, Tsai MK, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378:1244–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La GA, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, et al. Exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction and structural remodelling in endurance athletes. Eur Heart J 2012;33:998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Breuckmann F, et al. Running: the risk of coronary events: prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nassenstein K, Breuckmann F, Lehmann N, et al. Left ventricular volumes and mass in marathon runners and their association with cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;25:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Keefe JH, Patil HR, Lavie CJ, et al. Potential adverse cardiovascular effects from excessive endurance exercise. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:587–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shave R, Oxborough D. Exercise-induced cardiac injury: evidence from novel imaging techniques and highly sensitive cardiac troponin assays. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012;54:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DC, Pate RR, Lavie CJ, et al. Running and all-cause mortality risk–is more better?. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44(Suppl. 2-5S):924. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson AW, Lee DC, Sui X, et al. Muscular strength is inversely related to prevalence and incidence of obesity in adult men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1988–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trudelle-Jackson E, Jackson AW, Morrow JR Jr. Relations of meeting national public health recommendations for muscular strengthening activities with strength, body composition, and obesity: the Women’s Injury Study. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1930–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng YJ, Gregg EW, De RN, et al. Muscle-strengthening activity and its association with insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Churilla JR, Magyari PM, Ford ES, et al. Muscular strengthening activity patterns and metabolic health risk among US adults. J Diabetes 2012;4:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurca R, Lamonte MJ, Barlow CE, et al. Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37: 1849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artero EG, Lee DC, Ruiz JR, et al. A prospective study of muscular strength and all-cause mortality in men with hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1831–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, et al. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamer M, Ingle L, Carroll S, et al. Physical activity and cardiovascular mortality risk: possible protective mechanisms? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:84–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huebschmann AG, Kohrt WM, Regensteiner JG. Exercise attenuates the premature cardiovascular aging effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vasc Med 2011;16:378–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koba S, Tanaka H, Maruyama C, et al. Physical activity in the Japan population: association with blood lipid levels and effects in reducing cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. J Atheroscler Thromb 2011;18:833–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddigan JI, Ardern CI, Riddell MC, et al. Relation of physical activity to cardiovascular disease mortality and the influence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1426–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An explanation of US physical activity surveys. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/surveillance.html#Surveys (accessed 30 Mar 2013).

- 41.Gruner C, Alig F, Muntwyler J. Validity of self-reported exercise-induced sweating as a measure of physical activity among patients with coronary artery disease. Swiss Med Wkly 2002;132:629–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strath SJ, Bassett DR, Ham SA, et al. Assessment of physical activity by telephone interview versus objective monitoring. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:2112–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport 2000;71:S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Schoenborn CA, et al. Trend and prevalence estimates based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]