YAP confers small cell lung cancer with the intratumoral heterogeneity and resistance to chemotherapy drugs.

Abstract

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has a high degree of plasticity and is characterized by a remarkable response to chemotherapy followed by the development of resistance. Here, we use a mouse SCLC model to show that intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC is progressively established during SCLC tumorigenesis. YAP/TAZ and Notch are required for the generation of non-neuroendocrine (Non-NE) SCLC tumor cells, but not for the initiation of SCLC. YAP signals through Notch-dependent and Notch-independent pathways to promote the fate conversion of SCLC from NE to Non-NE tumor cells by inducing Rest expression. In addition, YAP activation enhances the chemoresistance in NE SCLC tumor cells, while the inactivation of YAP in Non-NE SCLC tumor cells switches cell death induced by chemotherapy drugs from apoptosis to pyroptosis. Our study demonstrates that YAP plays critical roles in the establishment of intratumoral heterogeneity and highlights the potential of targeting YAP for chemoresistant SCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is classified as a high-grade neuroendocrine (NE) tumor. The overall 5-year survival rate of advanced-stage disease remains at 1 to 5% for decades (1). SCLC is a particularly aggressive and deadly form of lung cancer characterized by fast growth, early metastasis, and rapidly acquired therapeutic resistance (2). The standard chemotherapy for SCLC consists of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide, which was defined decades ago (3). A remarkable response to the chemotherapy is followed almost invariably by the development of resistant disease. The addition of immunotherapy to classic chemotherapy led to a longer overall survival, but only limited efficacy in most patients with SCLC (4, 5). The molecular mechanisms responsible for acquired therapeutic resistance in SCLC are largely unknown. More effective treatment approaches for SCLC are desperately needed.

Acquired resistance is the direct consequence of preexisting intratumor heterogeneity and progressive alteration during therapy, which enables the chosen tumor cells to survive the treatment and facilitates the development of therapy-resistant mechanisms (6). Although most SCLC tumor cells display strong NE features, some tumor cells do not express NE genes and are so-called non-neuroendocrine (Non-NE) tumor cells. Non-NE tumor cells were also observed in both mouse and human SCLC tumors (7, 8). Emerging evidence indicates that the activation of Ras or Notch signaling within SCLC tumors promotes the generation of Non-NE SCLC cells (8–11). However, how the intratumor heterogeneity in SCLC tumors is established and pertains to the acquired therapeutic resistance and metastatic progression are largely unexplored.

Recently, four distinct molecular subtypes of SCLC are defined by differential expression of four key transcription regulators ASCL1 (achaete-scute family bHLH transcription factor 1), NEUROD1 (neuronal differentiation 1), POU2F3 (POU class 2 homeobox 3), or YAP, which is based from the comprehensive analysis of primary human tumors, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), cancer cell lines, and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) (12). ASCL1high subtype of SCLC represents most SCLC (12). Ascl1, but not Neurod1, is required for tumorigenesis in mouse SCLC models (13). NEUROD1high subtype is associated with variant cell morphology and MYC amplification in human SCLC cell lines (13). Myc expression drives tumors to activate Notch, shifting SCLC from ASCL1high to NEUROD1high and to YAPhigh states (14, 15). Expression profiling of a large panel of human SCLC reveals that YAP, the key transcriptional regulator in the Hippo pathway, is highly expressed in Non-NE SCLC cell lines but low or undetectable in most SCLC cell lines with the ASCL1high or NEUROD1high NE subtypes (16, 17). In contrast to SCLC, YAP expression and activity are pervasively induced in most other human solid tumors, as revealed by immunohistochemistry and gene expression analyses in large cohorts of patient samples (18, 19). YAP is instrumental for tumor initiation and progression in multiple tissue types. YAP activation endows cancer cells with several of the abilities, particularly in proliferation, metastasis, immune evasion, and drug resistance (20). However, the precise role of YAP in the initiation, progression, and drug resistance of SCLC is currently lacking.

A large number of comprehensive genomic studies have reported that recurrent loss-of-function alterations in RB1 and TP53 occur in 90 to 100% of human SCLC (21–23). Simultaneous loss of Rb1 and Trp53 in the mouse lungs demonstrates that inactivation of the two genes is a critical step for SCLC initial development (24). In cooperation with Rb1 and Trp53 loss, deletion of Rb1 family member Rbl2 (p130) (25) or Pten tumor suppressor (26–28) and overexpression of Myc (15), FGFR1 (29), or Mycl (30) generate variable histological subtypes of mouse SCLC with different tumor latency. Previously, we have described a mouse model in which SCLC is developed within 2 months after cell type–specific inactivation of Trp53, Rb1, and Pten in pulmonary NE cells (PNECs) using CgrpCreER cre driver (26). Here, we set out to determine the impact of Yap on the establishment of intratumoral heterogeneity and chemoresistance of SCLC based on the mouse SCLC model CgrpCreER;Trp53f/f;Rb1f/f;Ptenf/f.

RESULTS

Intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC is progressively established

The evidence of intratumoral heterogeneity in the mouse SCLC model, CgrpCreER;Trp53f/f;Rb1f/f;Ptenf/f (referred to as CgrpCreER;TKO (triple knockout), or TKO in the figures), was determined by the expression of a variety of genes that have been identified as possible markers for Non-NE tumor cells, such as Hes1 and Cc10 (encoded by Scgb1a1) (8, 31). To explore how the intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC is regulated, we first evaluated the kinetics of HES1 (Hes family bHLH transcription factor 1) and CC10 (Clara cells 10 kDa secretory protein) protein expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mouse lung tumors during the SCLC progression. All CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice developed SCLC tumors within 2 months with all tumor cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and markers for NE differentiation following tamoxifen injection. In the CgrpCreER;TKO SCLC model initiated by tamoxifen, almost all the PNECs including neuroepithelial body (NEB) and solitary PNEC progressed to hyperplasia or tumors because we could not find normal NEB or solitary PNEC along the distal large airways or small bronchioles. HES1+ tumor cells marked by GFP expression were absent within the first week but appeared 2 weeks after tamoxifen injection and continued to increase over time (Fig. 1A). CC10+ tumor cells appeared later than HES1-expressing cells (Fig. 1B). Notably, most of CC10+ tumor cells were also HES1 positive (fig. S1A). Occasionally, tumor cells expressing both NE (SYP) and Non-NE (HES1) markers were observed at two to three consecutive sections in a tumor, which might represent an intermediate stage of the cell fate transition (fig. S1B). Our results suggest that both NE and Non-NE SCLC tumor cells are clonally derived from PNEC precursors and that Non-NE tumor cells are gradually developed during the progression of SCLC.

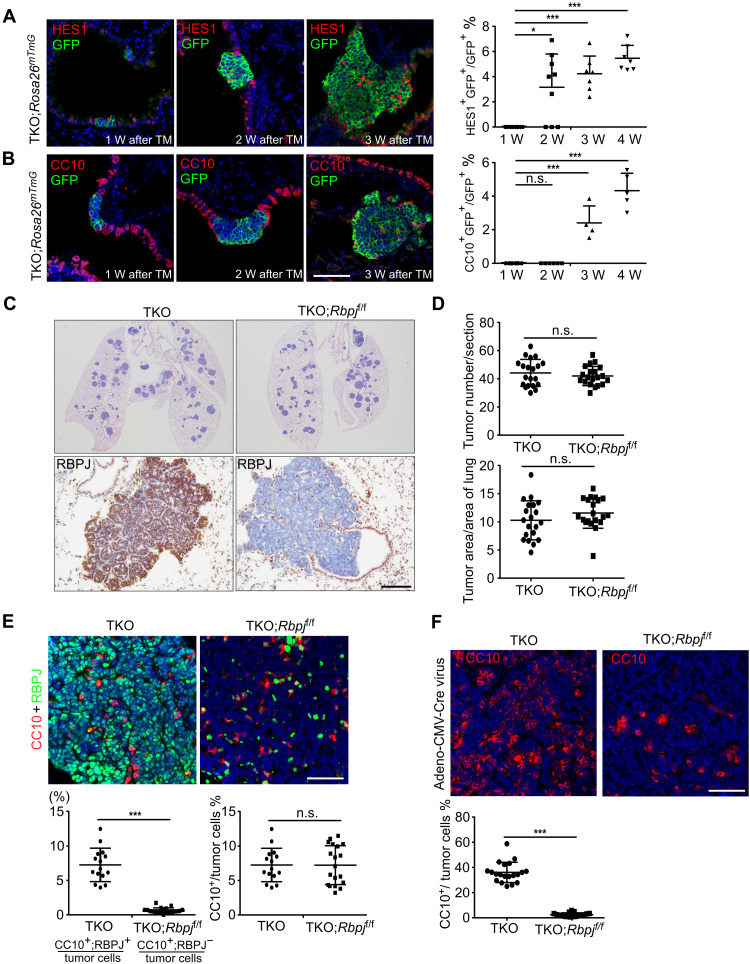

Fig. 1. Non-NE tumor cells gradually occurred during SCLC progression.

(A and B) HES1 (A) and CC10 (B) immunofluorescence staining of SCLC tumors from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG adult mice at indicated times after tamoxifen (TM) injection. Scale bar, 50 μm. Right panels show statistical analysis of percentage of HES1+ (A) and CC10+ (B) cells. n = 3 mice per group at each time point. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. n.s., not significant. (C) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and RBPJ immunostaining on lung sections from CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f mice 2 months after tamoxifen injection. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantification of tumor burden and tumor number in CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f mouse lungs 2 months after tamoxifen injection. n = 5 mice per group. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of SCLC tumors from CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f mice 2 months after tamoxifen injection. Statistical analysis of percentage of CC10+ cells. n = 5 mice per group. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of SCLC tumors from CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f adult mice 2 months after Adeno-CMV-Cre virus administration. The bottom panel shows statistical analysis of percentage of CC10+ cells. n = 5 mice per group. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Activation of Notch pathway has been shown to lead to an NE to Non-NE fate switch in the mouse and human SCLC tumor cells (8). Our previous study demonstrated that Notch signaling plays the key role in PNEC transdifferentiation following naphthalene-induced lung injury (32), a process similar to the NE to Non-NE fate conversion in SCLC tumors. It is possible that the intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC is regulated by Notch signaling. To test this idea, we introduced Rbpj (Notch transcriptional coactivator)–floxed allele into the CgrpCreER;TKO SCLC model to inactivate the transcriptional activity of Notch pathway by generating CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f mice. Immunostaining of CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f SCLC tumors with anti-RBPJ (recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region) antibody revealed a complete removal of Rbpj gene in the CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f SCLC tumor cells (Fig. 1C). Notably, the tumor load and tumor count in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f mice was comparable with CgrpCreER;TKO mice 2 months after tamoxifen injection (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, tumor cells derived from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f SCLC tumors did not respond to Notch activation, indicated by the nonresponsiveness of Notch target gene HES1 upon NICD (Notch1 intracellular domain) overexpression (fig. S1C). Thus, our results suggest that Notch is not required for the initiation of SCLC.

Next, intratumoral heterogeneity of CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f SCLC tumors was assayed by the CC10-expressing cells. Unexpectedly, the overall CC10+ cells in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumors were similar as in CgrpCreER;TKO tumors (Fig. 1E). However, a careful examination of CC10+ cells in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumors suggested that many of them were not tumor cells because RBPJ proteins were still expressed in these cells by costaining the tumors with anti-CC10 and RBPJ antibodies (Fig. 1E). Only very few CC10+;RBPJ− tumor cells were present in the CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumors (Fig. 1E). It is possible that CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumor cells attracted uncharacterized stromal cells from the surrounding tissue into the SCLC tumors to function as Non-NE tumor cells and to fulfill the tumor growth and metastasis. Previous studies showed that mouse SCLC initiated from different origin of cells displays distinct intratumoral heterogeneity evidenced by the amount of CC10+ tumor cells using cell type–specific promoter-driven Adeno-Cre virus (31). In agreement with the previous finding, the tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus had much higher number of CC10+ and HES1+ tumor cells than that of tamoxifen-induced tumors (fig. S1D). Notably, there was a significant decrease of CC10+ cells in the CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus (Fig. 1F). RBPJ immunostaining confirmed that the Rbpj gene had been completely deleted by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus in the CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f tumors (fig. S1E). Together, these results suggest that Notch signaling is required for the generation of Non-NE SCLC tumor cells, but not for the tumorigenesis of SCLC.

YAP is not expressed in PNECs and NE SCLC cells

Recently, several studies speculate that YAP is a transcriptional driver for Non-NE subtype of SCLC based on the expression profiling of a large panel of human SCLC cell lines and tumor tissues (12, 17, 33, 34). To investigate the function of YAP in SCLC, we first examined YAP expression in PNECs, the cell origin of mouse SCLC in CgrpCreER;TKO model. As expected, YAP expression was not detected in the NEB or solitary PNECs of healthy human lungs and adult mouse lungs (Fig. 2, A and B). Similar to HES1, YAP+ tumor cells were absent within the first week following tamoxifen injection but appeared 2 weeks after tamoxifen injection and continued to increase over time (Fig. 2C). Most of YAP+ tumor cells were also HES1 positive (fig. S2A). In addition, the frequency of YAP+ tumor cells varied in human SCLC tumors (Fig. 2D). To further validate the expression of YAP proteins in mouse SCLC tumor cells, we used flow cytometry to analyze the expression of YAP (fig. S2B). Tumor-bearing lungs were enzymatically dissociated into single cells from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice after tamoxifen injection at different time and subjected to flow cytometry analysis using anti-YAP antibody. Tumor cells were identified by the GFP reporter. Similar to immunostaining, the ratio of YAP-expressing tumor cells increased during tumor progression by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S2, C and D). Notably, the tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice had more YAP-expressing tumor cells than that of tamoxifen-induced tumors (fig. S2E), which is consistent with the observation of CC10 and HES1 expression in Adeno-CMV-Cre virus-induced tumors. Thus, our data indicate that YAP is expressed in a subpopulation of SCLC tumor cells.

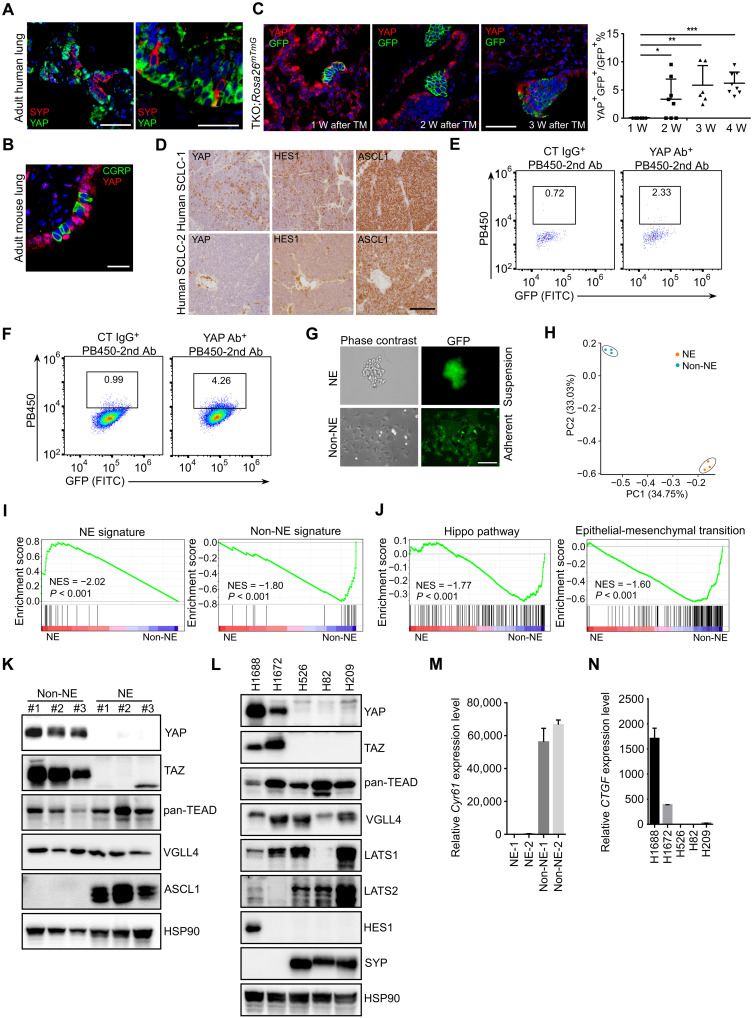

Fig. 2. YAP is expressed in a subset of SCLC tumor cells.

(A and B) Immunofluorescence staining of adult human (A) and mouse (B) lung sections with indicated antibodies. Scale bars, 50 μm (A) and 20 μm (B). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of lung sections with anti-YAP and anti-GFP antibodies from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG adult mice at indicated times. Right panel shows the quantification of YAP+ tumor cells. n = 3 mice per group at each time point. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Immunostaining of human SCLC tumor sections with indicated antibodies. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E and F) Flow cytometry analysis of YAP expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG SCLC tumor cells 2 weeks (E) and 5 weeks (F) after tamoxifen injection. Whole lung cells were proceeded to flow cytometry analysis by control immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-YAP antibody (Ab). Tumor cells were genetically labeled by GFP protein from Rosa26mTmG reporter. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. (G) The morphology of SCLC cells derived from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG lung tumors with suspending aggregates (NE) and attaching (Non-NE) cells. Both of the clones expressed GFP. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H) PCA of RNA-seq from mouse NE and Non-NE tumor cells. (I and J) GSEA for NE and Non-NE signature (I) and Hippo pathway genes and EMT (J) from the RNA-seq data of mouse NE and Non-NE tumor cells. (K) Western blot analysis of a panel of mouse NE and Non-NE SCLC cell lines derived from CgrpCreER;TKO mice. (L) Western blot analysis of a panel of human SCLC cell lines. (M) Quantitative analysis of Cyr61 mRNA levels in mouse NE and Non-NE tumor cell lines. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as means ± SD. (N) Quantitative analysis of CTGF mRNA levels in human SCLC tumor cells. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments.

To further characterize and investigate intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC, we established mouse SCLC tumor cell lines from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG SCLC tumors in which all tumor cells are labeled with GFP reporter. Consistent with a previous observation in mouse Trp53 and Rb1 DKO (double knockout) SCLC tumor cells (11), mouse CgrpCreER;TKO SCLC cells grew as suspension of small aggregated cells (NE) and adherent (Non-NE) tumor cells in the primary culture dish (Fig. 2G). Genotyping the mouse SCLC cell lines confirmed the complete deletion of Trp53-, Rb1-, and Pten-floxed alleles in both mouse NE and Non-NE tumor cells (fig. S2F). Tumor cells expanded rapidly and could be passaged for extended periods of time. Both suspension and adherent tumor cells expressed GFP protein (Fig. 2G), indicating that they were both derived from the same cell of origin, PNECs.

Three paired NE and Non-NE cell lines derived from independent mouse SCLC tumors were subjected to expression profiling analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (fig. S2, G and H). Global transcriptome analysis revealed that mouse NE and Non-NE tumor cells exhibited strong transcriptional similarity within the groups but did not overlap each other by principal components analysis (PCA) (Fig. 2H). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) supported an enrichment for NE and Non-NE signature in NE tumor cells and Non-NE tumor cells, respectively, with the gene sets comprising 25 NE- and 25 Non-NE–related genes from human SCLC cell lines (Fig. 2I) (35) and Hippo pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in Non-NE SCLC cells (Fig. 2J). Next, YAP and its homolog TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif) expression was examined in a panel of human and mouse SCLC cells. In agreement with previous findings, YAP and TAZ proteins were not detected in human and mouse NE SCLC cells (Fig. 2, K and L). In contrast, other Hippo pathway components such as TEADs (TEA domain family members), VGLL4 (vestigial like family member 4), and LATS (large tumor suppressor kinase) 1/2 were expressed in both NE and Non-NE SCLC cells (Fig. 2, K and L). As expected, YAP/TEAD target genes CTGF and CYR61 only expressed in YAP-expressing tumor cells (Fig. 2, M and N). We noticed that the adherent mouse Non-NE cell lines expressed a very low level of HES1 (fig. S2I). We reasoned that Notch pathway may be not activated in the cultured Non-NE tumor cells because of the lack of Notch ligands. To test this, we mixed mouse NE tumor cells (express high levels of Notch ligands) with Non-NE SCLC cells in the culture dish. Notably, NE cells tended to attach to the Non-NE cells the following day and induced HES1 expression in Non-NE SCLC cells (fig. S2I). Together, these results suggest that the expression of YAP in both mouse and human primary SCLC tumors represents an intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC.

YAP activation drives NE to Non-NE fate conversion of SCLC

To determine whether YAP activation could drive the transition from NE to Non-NE phenotype in mouse SCLC cells, we generated a doxycycline (dox)–inducible Flag-YAPS127A and Flag-YAP5SA (both are constitutively activated forms of YAP, and YAP5SA has a higher activity than YAPS127A) transgenic mice by pronuclear injection of the TRE-Flag-YAPS127A-polyA or TRE-Flag-YAP5SA-polyA cassette DNA into fertilized mouse eggs (Fig. 3A). Compound genetically engineered SCLC mouse models (CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A and CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA) with inducible Flag-YAPS127A and Flag-YAP5SA expression by dox administration were generated by introducing TRE-Flag-YAPS127A, TRE-Flag-YAP5SA, and Rosa26rtTA into the CgrpCreER;TKO SCLC mouse model. Mouse SCLC tumor cells were derived from CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A and CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA tumors. Active forms of YAP were induced by the addition of dox to the cultures of these SCLC tumor cells. Protein and mRNA levels of the NE marker ASCL1 were greatly decreased upon dox administration to the CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A and CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA NE SCLC cells (Fig. 3, B and C, and fig. S3A). In addition, the expression of YAP5SA, but not YAPS94A (does not bind to TEAD transcription factors), suppressed ASCL1 expression in human SCLC NCI-H209 cells (Fig. 3D) and mouse NE SCLC cells (fig. S3B), indicating that this process is TEAD dependent. The conversion of NE to Non-NE SCLC cells often accompanies with morphological change of cells (8, 11). Sustained expression of active YAP, but not YAPS94A, caused mouse and human NE SCLC cells from a tight floating cluster to adherent cultures (Fig. 3, E and F). The magnitude of changes maximally started at 7 days after YAP expression, when 70 to 80% of spheroids adhered to the plastic dish with increased cell size and spreading. Gene expression profiling of YAP5SA induction in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA NE SCLC cells in a time course fashion further supported the down-regulation of NE marker gene expression (Fig. 3G) and increased Non-NE gene expression (Fig. 3H) over time, as well as a profound change in the transcriptome during the fate switch (fig. S3, C and D). In addition, a large number of the genes differentially expressed between days 0 and 21 of YAP5SA-expressing mouse tumor cells overlapped with the differentially expressed gene set from NE versus Non-NE mouse SCLC cells (Fig. 3I). Thus, YAP activation suppresses the expression of NE genes and induces a morphological change in NE tumor cells.

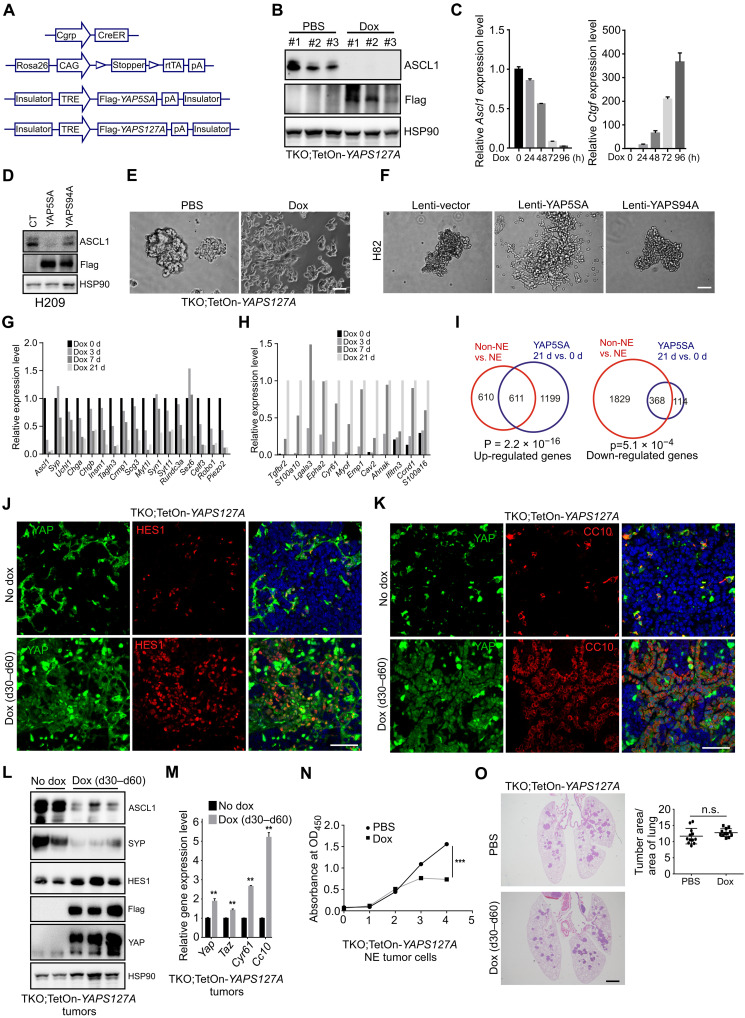

Fig. 3. YAP activation drives NE to Non-NE fate conversion of SCLC.

(A) Schematic representation of the generation of dox-inducible YAPS127A and YAP5SA mouse lines. (B and C) Western blot (B) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (C) analysis of ASCL1 levels in mouse CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated without or with dox for 96 hours. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of ASCL1 protein in Lenti-YAP5SA and Lenti-YAPS94A virus–transduced NCI-H209 cells. (E and F) Phase-contrast photomicrographs of dox-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE SCLC cells and Lenti-YAP5SA– and Lenti-YAPS94A–transduced NCI-H82 cells for 2 weeks. Scale bars, 20 μm (E), 50 μm (F). (G and H) Histogram representing the relative expression changes of NE (G) and Non-NE (H) signature genes from RNA-seq analysis of YAP5SA-expressing cells. (I) Venn diagram representing the numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each indicated paired comparison set. (J and K) Immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissues from CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A lungs treated without or with dox. Scale bars, 50 μm. (L and M) Western blot (L) and quantitative PCR (M) analysis of tumor tissues isolated from CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A lungs treated without or with dox. n = 3 mice per group. Data are presented as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01. (N) Cell proliferation analysis of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with or without dox. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. (O) Representative H&E staining of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A lungs treated without or with dox. Scale bar, 500 μm. Quantification of tumor burden was shown at the right panel. n = 3 mice per group.

Next, we were wondering whether the fate change of NE tumor cells occurs upon YAP activation in vivo. To test this, we treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A and CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA mice with dox for 30 days 1 month after tamoxifen injection. Notably, the expression of YAP5SA led to the fate change in almost all NE SCLC tumor cells, indicated by the loss of NE marker ASCL1 and the change of cell morphology with aberrant nuclear (fig. S3E). For unknown reason, not all tumor cells expressed YAPS127A in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A SCLC tumors shown by immunostaining with anti-YAP antibody (Fig. 3, J and K). Next, YAPS127A-expressing tumor cells were investigated by examining various NE and Non-NE marker expression. Consistent with the in vitro study, YAPS127A expressing cells also exhibited HES1, CC10, and VIMENTIN expression (Fig. 3, J and K, and fig. S3F), indicating that these cells have lost NE differentiation. Immunoblotting and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of lung tumor tissues isolated from dox-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice further confirmed the down-regulation of NE markers ASCL1 and SYP (Synaptophysin) and the up-regulation of Non-NE markers HES1 and Cc10 (Fig. 3, L and M). In addition, ectopic expression of YAPS127A did not change lung epithelial cell lineage of tumor cells, indicated by NKX2.1 expression (fig. S3G). Similar to CgrpCreER;TKO (26), dox-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice could not survive beyond 2 months after tamoxifen injection. Although the expression of YAPS127A in mouse NE tumor cells inhibited the cell growth in vitro (Fig. 3N), there was no significant difference in the tumor size of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice treated with or without dox during the treatment (Fig. 3O). As TKO mice developed medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), which expresses ASCL1 and SYP (26, 36), we also examined the fate of MTC tumor cells upon the activation of YAP5SA and YAPS127A. Consistent with the observations in lung tumors, YAP activation suppressed ASCL1 and SYP expression in MTC tumors (fig. S3, H and I). MTC tumors seemed more vulnerable to YAP-induced cell fate conversion because most CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A MTC tumor cells lost NE marker expression and changed cell morphology (fig. S3, I and J). Together, these results demonstrate that activation of YAP in NE SCLC cells elicits a fate change to Non-NE state and highlights the central role of YAP signaling in regulating NE to Non-NE transition.

Loss of YAP and TAZ results in the loss of Non-NE tumor cells in SCLC

To determine whether Yap and Taz are required for the formation of Non-NE tumor cells, we generated a mouse SCLC model without Yap and Taz expression by introducing floxed Yap and Taz alleles into TKO mice. Loss of Yap alone had no effect on tumor formation (fig. S4A). In contrast to CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f SCLC tumors, the tumor formation assayed by histological examination of tumor load or tumor count was significantly attenuated when Yap and Taz were both removed in mouse SCLC tumors (Fig. 4, A and B). The cell proliferation was slightly decreased in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f tumors, but there was no statistically significant difference (fig. S4B). Cell death examined by cleaved caspase-3 expression was largely unaffected upon Yap and Taz deletion (fig. S4B). Next, the intratumoral heterogeneity of CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f SCLC tumors was examined by CC10- and HES1-expressing cells. Similar with CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f SCLC tumors, the overall CC10- and HES1-expressing cells were similar between control and CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f SCLC tumors 2 months after tamoxifen injection (Fig. 4C). However, we found that CC10+ cells still expressed YAP shown by costaining tumor tissues with anti-CC10 and anti-YAP antibodies (fig. S4C), suggesting that CC10+ cells were not tumor cells in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/ f;Tazf/f f lung tumors. Next, we induced SCLC tumor formation by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus. Notably, both CC10+ and HES1+ tumor cells decreased markedly in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f SCLC tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus (Fig. 4D and fig. S4D). Thus, our results demonstrate that Yap and Taz are required for tumor progression and generation of Non-NE tumor cells in mouse SCLC.

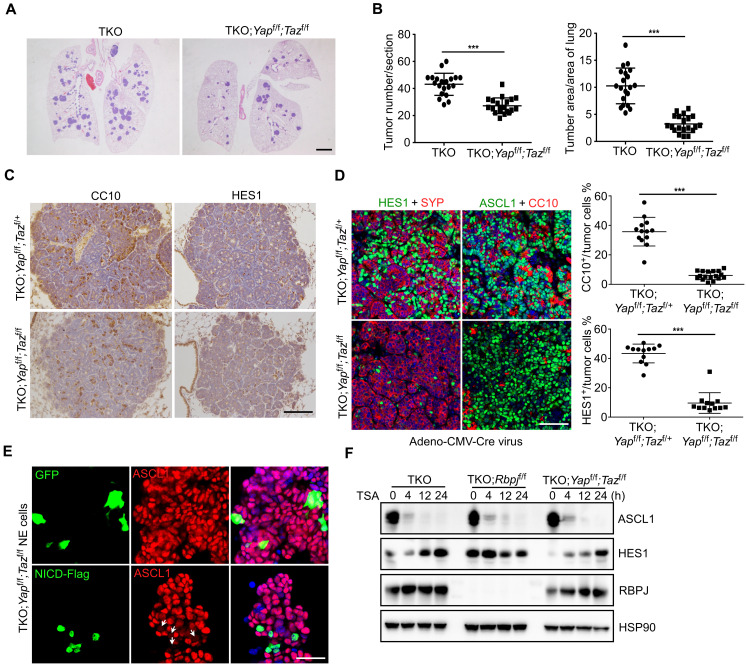

Fig. 4. Loss of YAP and TAZ results in the decreased Non-NE tumor cells in SCLC.

(A) Representative H&E staining of CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f lungs 2 months after tamoxifen injection. Scale bar, 500 μm. (B) Quantification of tumor burden and tumor number of CgrpCreER;TKO and CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f mice 2 months after tamoxifen injection. n = 5 mice each genotype. ***P < 0.001. (C) Immunostaining of CC10 and HES1 expression in the lung tumors of CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/+ and CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f mice 60 days after tamoxifen injection. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of CC10 and HES1 expression in the lung tumors of CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/+ and CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f mice 70 days after Adeno-CMV-Cre virus administration. n = 5 mice each genotype. Right panels show the statistical analysis of the percentage of HES1- and CC10-positive cells. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of ASCL1 in mouse CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f NE SCLC cells transfected with GFP or NICD-Flag plasmids. Arrows indicate NICD-Flag–expressing cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) Western blot analysis of various mouse NE tumor cells treated with TSA at indicated times.

It has been demonstrated that Notch pathway inhibits NE differentiation during lung development (37) and promotes NE to Non-NE conversion of SCLC by inducing Rest expression (8). To test whether Yap and Taz are required for Notch-driven NE to Non-NE fate switch, we overexpressed NICD in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f NE tumor cells. The expression of ASCL1 in NE tumor cells was still inhibited by NICD expression in the absence of Yap and Taz (Fig. 4E). It has been previously described that the alteration of histone acetylation induces human SCLC cell lines to a dedifferentiated phenotype, characterized by the down-regulation of NE markers through Notch and Rest activation (38). Therefore, trichostatin A (TSA), a potent and specific inhibitor of histone deacetylase activity, was used to activate Notch in NE SCLC cells. Consistent with previous observation, ASCL1 expression was quickly down-regulated with concomitant elevated Notch target HES1 expression in TKO NE tumor cells when TSA was administrated (Fig. 4F). However, the expression dynamics of ASCL1 and HES1 in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f NE tumor cells were same as in CgrpCreER;TKO NE tumor cells (Fig. 4F). Notably, ASCL1 expression was inhibited, and Rest expression was elevated in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f NE tumor cells with TSA treatment (Fig. 4F and fig. S4E). These results suggest that there is a Notch-independent mechanism for the regulation of Ascl1 and Rest expression.

Yap directly regulates Notch2 and Rest expression in SCLC

It is noteworthy that YAP/TAZ and Notch signaling extensively interact in many scenarios, such as self-renewal and differentiation of stem cell, cell fate decisions, and human cancers (39). Recent studies suggest that Notch2 is a direct transcriptional target of YAP (40). We found that the expression of YAPS127A in mouse SCLC tumors and NE tumor cells induced the expression of Notch2 and its target gene Hes1 (Fig. 5, A to C). However, ectopic expression of NICD did not induce YAP and TAZ expression in mouse and human NE SCLC cells (fig. S5, A and B). To test whether Notch is required for YAP-induced NE to Non-NE conversion, we used γ-secretase inhibitor dibenzazepine (DBZ) to inhibit Notch activity during YAP activation. As expected, the induction of HES1 by YAPS127A expression was diminished by the treatment with DBZ in NE tumor cells (Fig. 5D). However, the loss of NE marker ASCL1 expression still occurred in NE tumor cells; even Notch activity was inhibited (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that YAP could act independently on Notch signaling to promote the conversion of NE to Non-NE cells.

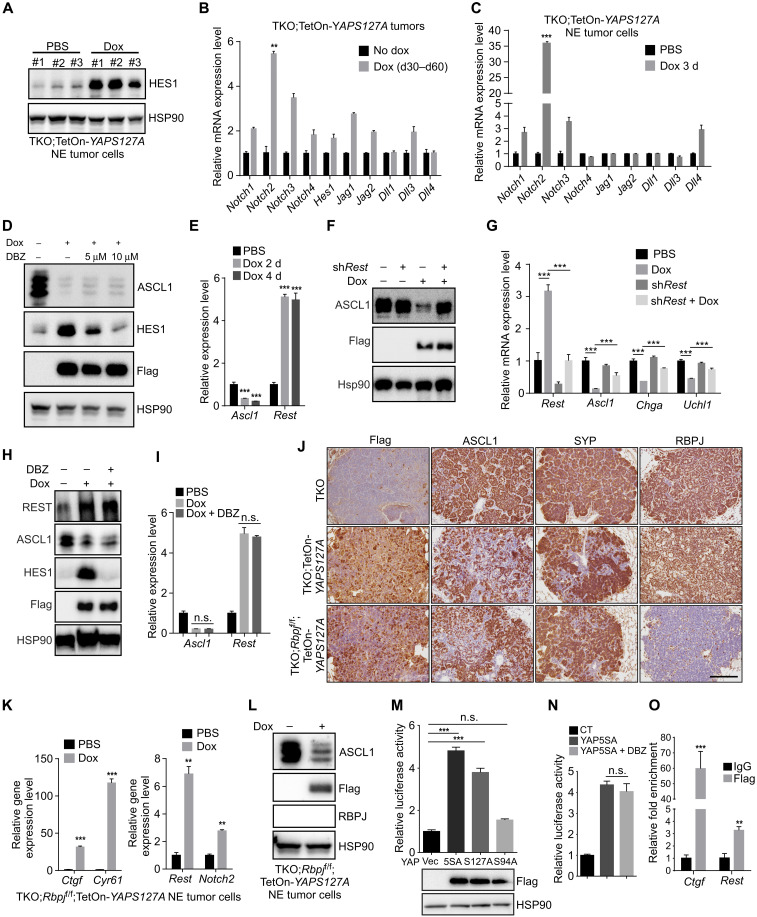

Fig. 5. YAP promotes the expression of Notch2 and Rest in SCLC.

(A) Western blot analysis of HES1 expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with dox for 96 hours. The same cell lysates were used as in Fig. 3B. (B and C) Quantitative analysis of Notch signaling components in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A tumor tissues (B) and NE cells (C) as indicated. (D) Western blot analysis of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with dox and DBZ together for 3 days. (E) Quantitative analysis of Ascl1 and Rest mRNA in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells as indicated. (F) Western blot analysis of ASCL1 expression in Rest knockdown CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated as indicated. (G) Quantitative analysis of gene expression levels in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE tumor cells treated with dox and shRest lentivirus. (H and I) Western blot (H) and quantitative PCR (I) analysis of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with dox and DBZ together for 4 days. (J) Immunostaining of lung tumors from indicated mice treated with dox from days 30 to 60 after tamoxifen injection. Scale bar, 100 μm. (K) Quantitative analysis of gene expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with dox for 4 days. (L) Western blot analysis of ASCL1 expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells treated with dox for 3 days. (M and N) Relative luciferase activity of mouse Rest 2-kb promoter assayed in CgrpCreER;TKO NE cells. (O) ChIP assay in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA NE cells treated with dox for 3 days. There are two YAP/TEAD binding sites in Ctgf ChIP region and one in Rest ChIP region. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Induction of Rest is a critical step to suppress NE differentiation in SCLC (8). Rest is also a direct target of Notch (8). We found that Rest expression was elevated upon YAP expression in both mouse and human NE SCLC cells (Fig. 5E and fig. S5, C and D). YAPS94A failed to induce REST expression in human SCLC NCI-H69 cells (fig. S5C). Down-regulation of Rest by short hairpin RNA restored the ASCL1 and NE gene expression in YAPS127A-expressing mouse NE tumor cells (Fig. 5, F and G). However, the depletion of Rest did not affect YAP-induced Vimentin (Vim) expression and morphological change of mouse NE tumor cells (fig. S5, E and F), indicating that YAP-induced EMT and down-regulation of NE gene expression might be separate events. To test whether up-regulation of Rest by YAP was through Notch signaling, we inhibited Notch activity with the treatment with DBZ. Unexpectedly, Rest expression was not affected by the administration of Notch inhibitor upon YAP expression (Fig. 5, H and I). To further validate this finding, we generated CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A compound mutant mice, in which YAPS127A can be conditionally induced in Rbpj KO (knockout) SCLC tumor cells. CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A tumors were characterized after dox treatment for 30 days 1 month after tamoxifen injection. Immunostaining of NE markers ASCL1 and SYP revealed a loss of NE differentiation in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A lung tumor cells (Fig. 5J) and thyroid tumor cells (fig. S5G), indicating that YAPS127A drives the fate change of NE tumors in the absence of Notch-mediated transcriptional regulation in vivo. CC10 expressing lung tumor cells was drastically reduced in CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A tumors (fig. S5H). Furthermore, YAP-induced Cc10 mRNA expression in mouse NE tumor cells was blocked by DBZ treatment (fig. 5SI), suggesting that Notch is the major regulator for the formation of CC10+ Non-NE tumor cells. Furthermore, consistent with the in vivo observation, the induction of YAPS127A in NE SCLC cells derived from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rbpjf/f;TetOn-YAPS127A tumors resulted in the up-regulation of Rest and Notch2 (Fig. 5K) and down-regulation of ASCL1 (Fig. 5L and fig. S5J). Together, these data suggest that YAP could drive NE to Non-NE conversion and Rest expression in SCLC through Notch-independent pathway.

Next, we were wondering whether YAP could directly regulate Rest expression. To test this, we cloned 2-kb mouse Rest promoter into a luciferase reporter vector. YAP5SA and YAPS127A, but not YAPS94A, elicited a luciferase activity driven by Rest promoter in mouse NE tumor cells (Fig. 5M). In addition, Notch inhibition by DBZ did not affect YAP-induced luciferase activity (Fig. 5N). Deletion analysis in the 2-kb Rest promoter determined a key region responsible for YAP-induced Rest expression (fig. S5K). There is a TEAD binding site located about 500–base pair upstream of the transcriptional start site of the Rest gene. YAP-induced luciferase activity was abolished when the TEAD binding site was deleted (fig. S5, L and M). Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay revealed that YAP/TEADs directly bound to the TEAD binding site in the mouse Rest promoter using CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA NE cells (Fig. 5O). Together, our results indicate that YAP promotes NE to Non-NE conversion through regulating Rest expression in Notch-dependent and Notch-independent ways.

Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis in NE SCLC cells

SCLC is initially highly responsive to cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy but, in almost every case, becomes rapidly chemoresistant (41). However, the mechanisms underlying initial sensitivity and subsequent resistance are not well understood. The notion that antitumor therapeutics act most potently through stimulating apoptosis prompted us to comprehensively investigate the different path of cell death that likely occurs in response to chemotherapy drugs in SCLC cells. NE and Non-NE tumor cells of human and mouse were selected to be treated with etoposide or cisplatin. Unexpectedly, reminiscent of characteristic pyroptotic cell morphology was observed in NE tumor cells with evident balloon-like bubbles that were distinct from classic apoptosis in mouse Non-NE tumor cells (Fig. 6, A and B). GSDME (Gasdermin E) in cancer cells has been recognized as the executor of cell pyroptosis induced by chemotherapy drugs (42, 43). Mouse Non-NE tumor cells had much lower GSDME expression compared to mouse NE tumor cells (Fig. 6C). Previous studies suggested that in vitro culture of cancer cells might lead to the loss of GSDME expression (43). By exploring a publicly available transcriptome dataset profiling the freshly isolated mouse NE and Non-NE SCLC cells from Trp53−/−;Rb1−/−;Rbl2−/− tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus, we found that GSDME expression was lower in HES1high Non-NE tumor cells than in HES1low NE tumor cells (fig. S6A), which is consistent with our observation from mouse SCLC tumor cell lines. Thus, GSDME expression was down-regulated during NE to Non-NE differentiation.

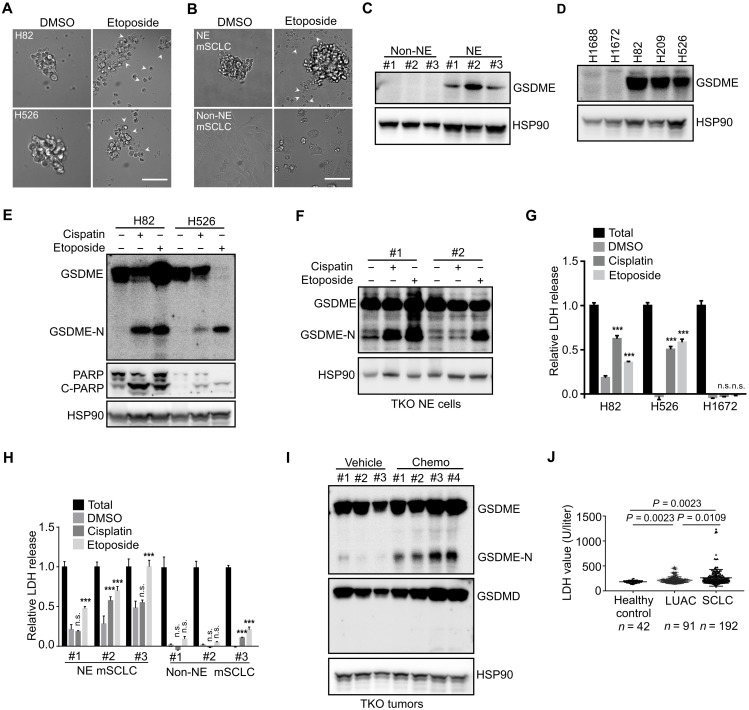

Fig. 6. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis in NE SCLC cells.

(A and B) Phase-contrast images of human (A) and mouse (B) SCLC cell lines treated with etoposide for 24 hours. Arrowheads indicate pyroptotic cells. Scale bars, 50 μm. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; mSCLC, mouse SCLC. (C and D) Western blot analysis of GSDME expression in mouse SCLC cells (C) and human SCLC cell lines (D). (E and F) Western blot analysis of human (E) and mouse (F) SCLC cells treated with cisplatin or etoposide for 24 hours. (G and H) LDH release assay in human (G) and mouse (H) SCLC cells treated with cisplatin or etoposide for 24 hours. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as means ± SD. ***P < 0.001. (I) Western blot analysis of SCLC tumor tissues isolated from CgrpCreER;TKO mice treated with an acute cisplatin/etoposide chemotherapy. (J) Serum LDH concentrations of healthy control, patients with LUAC, and patients with SCLC at the diagnosis without any treatment.

Next, we examined GSDME expression in several human SCLC cell lines. NCI-H82, NCI-H526, and NCI-H209 had much higher GSDME expression than NCI-H1688 and NCI-H1672 SCLC cell lines (Fig. 6D). GSDME expression showed a negative correlation with YAP (Figs. 2, I and J, and 6, C and D). Recent studies establish that tumor cell pyroptosis is executed by proteolytically processed GSDME upon the activation of caspase-3 (42, 43). GSDME was cleaved to generate N-terminal fragments following etoposide or cisplatin treatment in mouse and human NE SCLC cells (Fig. 6, E and F, and fig. S6B). Furthermore, only NE SCLC cells released lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) due to the pores formed on the plasma membrane by the cleaved GSDME (Fig. 6, G and H). The cleavage of GSDME and extracellular release of LDH were abrogated by the cotreatment with a pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD (fig. S6, C and D). To test whether pyroptosis of SCLC cells occurs in vivo, one round of acute chemotherapy was administrated to the tumor-bearing CgrpCreER;TKO mice. As expected, the cleavage of GSDME was readily detected in the chemotherapy drug–treated SCLC tumors (Fig. 6I), with concomitant increased serum LDH levels (fig. S6E). Similar to the studies in mice, chemotherapy-induced pyroptosis was plausibly functional in human patients with SCLC. A significant number of patients with SCLC had increased serum LDH concentrations after cisplatin/etoposide-based treatment (fig. S6F). Although multiple factors likely contributed to the elevated serum LDH levels, a fraction of patients showed progressively reduced serum LDH levels accompanying marked cancer regression (fig. S6G), highlighting a circumstance where drug-related tumor cell death at least partially accounted for the LDH release. Serum LDH levels of some patients with acquired resistance to chemotherapy did not respond to cisplatin/etoposide administration (fig. S6H), suggesting that the SCLC tumor cells might acquire alternative mechanism to bypass the chemotherapy-induced pyroptotic cell death. In addition, consistent with frequent necrosis observed in human SCLC tumors, human patients with SCLC without any treatment exhibited a higher level of serum LDH than healthy control and patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAC) (Fig. 6J). Furthermore, SCLC tumor–bearing mice had higher serum LDH levels than nontumor mice (fig. S6I). Notably, mouse TKO SCLC tumors often exhibited necrosis in the center of tumors compared to mouse LUAC driven by oncogenic KrasG12D (fig. S6, J and K). Together, these results suggest that GSDME is highly expressed in NE SCLC cells, and chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis in NE SCLC cells.

YAP activation decreases the chemosensitivity of NE SCLC cells

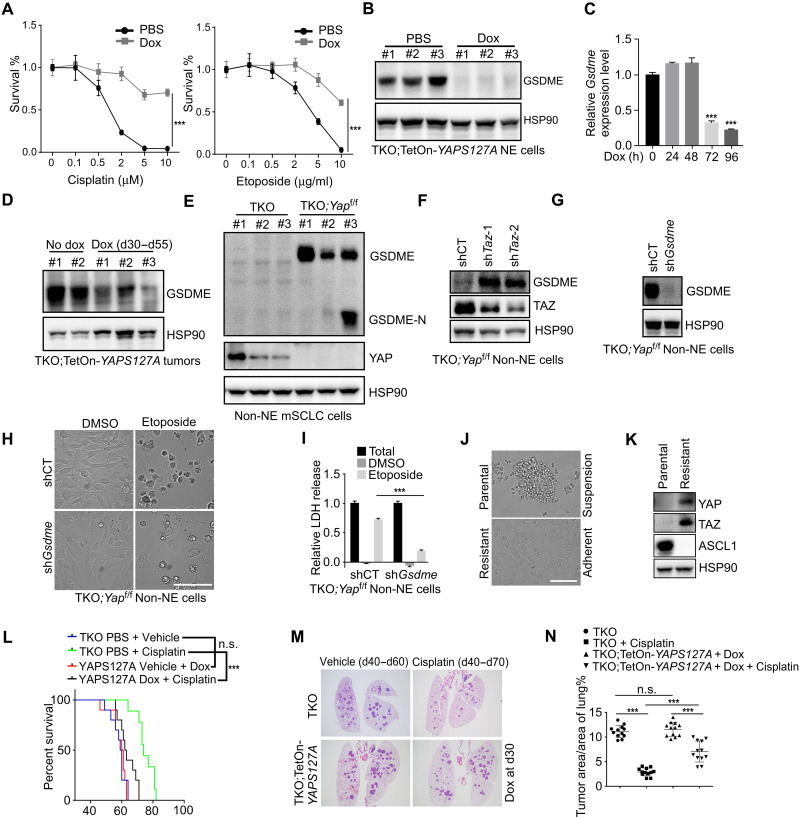

Emerging evidence indicates that deregulation of YAP/TAZ signaling is a major mechanism of intrinsic and acquired resistance to various targeted and chemotherapies (44). In a comparison of median inhibitory concentration values for cisplatin and etoposide between YAP+ Non-NE and YAP− NE mouse SCLC groups, Non-NE cell lines were significantly more resistant to chemotherapy drugs than NE tumor cell lines (fig. S6L). Intriguingly, the activation of YAP enhanced the resistance to chemotherapy drugs in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE SCLC cells with a concomitant down-regulation of GSDME expression and LDH release (Fig. 7, A to D, and fig. S6, M to O). Similar reduction of GSDME was observed in YAP-overexpressing human SCLC NCI-H82 cells (fig. S6P). To further delineate the function of YAP in regulating chemoresistance, NE and Non-NE SCLC cells were generated from CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f mice. GSDME expression was significantly elevated in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f Non-NE SCLC cells (Fig. 7E), and knockdown of Taz further increased GSDME expression (Fig. 7F). Consistent with increased GSDME expression, loss of Yap switched apoptosis to pyroptosis in etoposide-treated Non-NE tumor cells, while ablating Gsdme reversed pyroptosis to apoptosis in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f Non-NE tumor cells (Fig. 7, G to I, and fig. S6Q). To determine whether YAP is correlated with acquired resistance, we generated an acquired drug-resistant mouse SCLC cell line by culturing NE tumor cells in gradually increasing doses of etoposide. Robustly, in vitro–acquired resistance to etoposide was associated with a change in cell morphology, converting from a suspension, aggregated culture to an exclusively adherent culture and loss of NE differentiation (Fig. 7J). Notably, YAP/TAZ expression was induced upon acquired drug resistance (Fig. 7K). Consistently, a multidrug-resistant variant, H69AR cells derived from human classic SCLC cell line NCI-H69, also exhibited up-regulation of YAP/TAZ in a publicly available dataset (fig. S6R). Thus, our results suggest that YAP/TAZ suppress GSDME expression in SCLC cells and that increased YAP expression is associated with acquired resistance to chemotherapy in SCLC.

Fig. 7. Activation of YAP suppresses GSDME expression and decreases the chemosensitivity in NE SCLC cells.

(A) Viability analysis of CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells without or with dox treatment for 3 days and followed by etoposide and cisplatin treatment for 48 hours. (B) Western blot analysis of GSDME expression in dox-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells. The same cell lysates were used as in Fig. 3B. (C and D) Quantitative PCR (C) and Western blot (D) analysis of GSDME expression in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A NE cells (C) and tumor tissues (D) treated with dox at indicated times. (E and F) Western blot analysis of GSDME expression in indicated Non-NE cells. (G) Western blot analysis of GSDME in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f Non-NE cells transduced with control or shGsdem lentivirus. (H and I) Phase-contrast images (H) and LDH release assay (I) in CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f Non-NE cells transduced with control or shGsdme lentivirus and exposed to etoposide for 48 hours. Scale bar, 50 μm. (J and K) Phase-contrast images (J) and Western blot analysis (K) of parental (suspension) and chemoresistant (adherent) mouse SCLC cell lines. Scale bar, 50 μm. (L) Survival curves for vehicle- and cisplatin-treated animals. Dox and cisplatin were administrated 30 days after tamoxifen injection. n = 15 mice per group. ***P < 0.001. (M) Representative H&E staining of vehicle- and cisplatin-treated animals. Lungs were collected at 70 days after tamoxifen injection. (N) Quantification of tumor burden of vehicle- and cisplatin-treated animals. Lungs were collected at 70 days after tamoxifen injection. n = 3 mice per group. ***P < 0.001. Data in (A), (C), and (I) are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments.

To further investigate the role of YAP in mediating chemoresistance in vivo, we administrated dox-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice with cisplatin or vehicle 40 days after tamoxifen injection. In line with the in vitro study, the mice expressing YAPS127A in tumor cells conveyed a significant worse survival than control cohort upon cisplatin treatment (Fig. 7L), suggesting that YAP-expressing tumors responded worse to the treatment. Furthermore, histopathological evaluation of the tumors showed less tumor regression in YAPS127A-expressing tumors after cisplatin treatment (Fig. 7, M and N). In addition, cisplatin-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f mice displayed significantly reduced tumor burden (fig. S6S). Because CgrpCreER;TKO;Yapf/f;Tazf/f mice have smaller lung tumors and reduced tumor number from the beginning, it is not clear whether the phenotype is due to the loss of Yap and Taz or small tumors to begin with. Together, these results suggest that SCLC tumor cells acquire chemoresistance upon YAP activation in mouse SCLC model.

Single-cell RNA-seq of mouse SCLC followed by chemotherapy

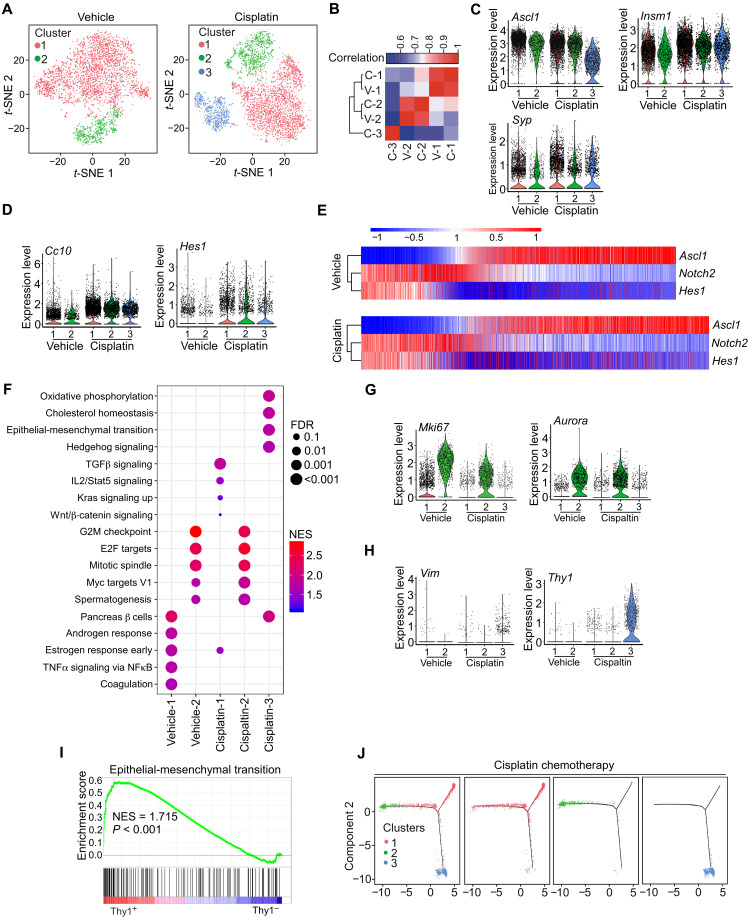

Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful method to comprehensively characterize cellular states in tissues. To extensively interrogate both intratumoral heterogeneity and mechanisms of acquired resistance to chemotherapy, we profiled single-cell transcriptomes using mouse TKO SCLC tumor samples from vehicle and chemotherapy-treated animals. To focus on malignant cells, we used CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice to specifically label tumor cells with GFP reporter and sorted GFP+ cells from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG lung tumors. In total, we obtained 3699 and 4245 high-quality cells from vehicle- and chemotherapy-treated mice, respectively. The mean and median numbers of detected genes per cell were 3227 and 3204 for the vehicle sample and 2597 and 2484 for the chemotherapy sample. To classify the major cell types, we performed t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis based on highly expressed genes and identified at least two clusters in vehicle-treated tumor cells and three clusters in chemotherapy-treated tumor cells (Fig. 8A and fig. S7, A and B). Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed that cluster 3 in chemotherapy-treated tumor cells represented a distinct population that did not correlate with any cluster in vehicle- and chemotherapy-treated tumor cells (Fig. 8B). In addition, cluster 3 has less NE feature than cluster 1 and cluster 2 by Spearman’s correlation analysis (fig. S7C). Consistent with mouse SCLC immunostaining, scRNA-seq revealed that tumor cells expressed a large number of NE-specific genes (such as Ascl1, Syp, and Insm1) (Fig. 8C) and Non-NE genes (Hes1 and Cc10) (Fig. 8D). However, Yap and Taz mRNAs were not detected by scRNA-seq because of the low abundance of Yap and Taz transcripts. Notably, Hes1high cells were clearly separated from Ascl1high cells, which further supports the existence of distinct Non-NE population in mouse SCLC tumors (Fig. 8E). In addition, the population of Hes1high or Scgb1a1high was increased after chemotherapy (Fig. 8, D and E). Thus, our scRNA-seq confirms the existence of Hes1high Non-NE cells in SCLC tumors and demonstrates the transcriptional diversity between cellular subpopulations.

Fig. 8. scRNA-seq of mouse SCLC followed by chemotherapy.

(A) t-SNE analysis of control and cisplatin-treated CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice. (B) Spearman’s correlation analysis among different clusters. V, vehicle; C, cisplatin. (C and D) Violin plots indicating the range of expression of Ascl1, Insm1, and Syp (C) and Hes1 and Cc10 (D) in single cells from each cluster. Each dot represents one cell, and the violin curves represent the density of cells at different expression levels. (E) Expression patterns of Ascl1, Notch2, and Hes1 genes from scRNA-seq in vehicle- and cisplatin-treated tumor cells. (F) The top five enriched hallmark gene sets in each cluster. NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. (G and H) Violin plots indicating the range of expression of Mki67 and Aurora (G) and Vim and Thy1 (H) in single cells from each cluster. (I) GSEA with NES for hallmark gene sets associated with EMT in Thy1+ (cluster 3) and Thy1− population. (J) Pseudo-time trajectory by monocle 2 from cisplatin-treated tumor cells.

Next, we performed GSEA to assess gene expression pathways associated with specific cell clusters in each group (Fig. 8F). Cluster 2 clearly showed enriched cell proliferation and was characterized with Mki67 and Aurora expression (Fig. 8G). EMT was within the top five enriched pathways in cluster 3 (Fig. 8F). Recently, EMT has been shown to associate with treatment resistance and metastasis of SCLC (45, 46). Cluster 3 had a proportion of cells that expressed the mesenchymal genes encoding Vim and Zeb1 and had elevated EMT scores (Fig. 8H and fig. S7D). In addition, cluster 3 had a high proportion of cells expressing Thy1 (Fig. 8H). Analysis of EMT pathway by GSEA based on Thy1 expression further confirmed that cluster 3 gained EMT feature (Fig. 8I). To investigate tumor cell evolution during chemotherapy, we constructed pseudo-time trajectories to delineate predicted transcriptional relationships within chemotherapy-treated tumor cells. Unsupervised pseudo-time ordering of combined tumor cells predicted a single lineage trajectory that corresponds with clusters 1 to 3 (Fig. 8J). Together, our scRNA-seq data suggest that chemotherapy induces a unique cell population with EMT state through a defined evolution path.

DISCUSSION

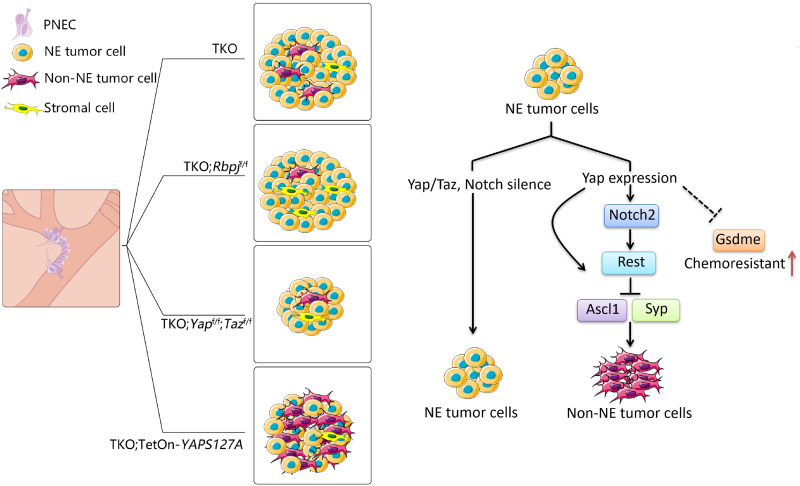

Tumor heterogeneity is critical for tumor growth, metastasis, and acquired therapeutic resistance. Emerging evidence indicates that SCLC NE tumor cells can give rise to a number of Non-NE tumor cells that promote tumor growth and chemoresistance. In this study, we investigated the fundamental mechanism of the establishment of Non-NE SCLC tumor cells and the role of YAP in the chemoresistance of SCLC. We found an extensive interaction between Notch and YAP signaling during the establishment of intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC using GEMM models. Furthermore, we showed that YAP/TAZ suppress GSDME expression in Non-NE SCLC cells, and activation of YAP enhanced the resistance to chemotherapy drugs in NE SCLC cells. Thus, our findings demonstrate that YAP/TAZ and Notch are critical for the generation of Non-NE population of SCLC and that YAP is involved in chemoresistance of SCLC by regulating the form of cell death (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. The model shows that YAP/TAZ regulate intertumoral heterogeneity and drug resistance of SCLC.

YAP signals through Notch-dependent and Notch-independent pathways to promote the fate conversion of SCLC from NE to Non-NE tumor cells by inducing REST expression. YAP suppresses GSDME expression in SCLC cells and is associated with acquired resistance to chemotherapy in SCLC.

We found that mouse SCLC tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus or CgrpCreER Cre driver are composed of Non-NE tumor cells at different frequencies. It is likely that different cell origins of SCLC have profound influences on the dynamics of tumor plasticity, which has been also argued in another study (31). Mouse SCLC tumors share many features with human SCLC, including cellular morphology, marker profile, and pattern of metastatic spread to specific organs. The derivation of cell lines with different cell morphologies from human SCLC tumors has also been reported (47–49). However, the procedures for deriving these cell lines might have resulted in the loss of heterogeneous tumor cells, because culture conditions selected for specific variants. Cancer organoids have near-physiological architecture, retaining specific functions of the native tumors and recapitulating drug responses. Development of SCLC organoids is an alternative approach to investigate the scale and evolution of intratumoral heterogeneity, the interaction among the tumor cell variants, and how it contributes to clinical outcomes.

Our results suggest that both YAP and Notch activity are required to promote Non-NE fate in mouse SCLC models. Extensive studies have outlined the interplay between YAP and Notch signaling, which influences various biological processes (39). In our study, YAP promotes REST expression and down-regulates NE signature genes in the absence of Notch transcriptional activity. Thus, YAP can act synergistically or independently with Notch to promote the fate conversion. It should be pointed out that unlike other type tumor cells, YAP is regulated at transcriptional level in SCLC. The molecular mechanisms of how YAP/TAZ are inactivated in NE tumor cells and reactivated in Non-NE tumor cells need further investigation. PNEC stem cells identified recently expressed low levels of Notch2 and Hes1 (50). Whether Yap is also expressed in the Notch2-expressing PNEC stem cells remains unknown. Recently, Notch activation in SCLC was shown to direct NE to Non-NE fate switch (8). This is contradictory to the inability of Notch activation in PNECs to confer new cell fates in the absence of lung injury (32). These studies suggest that SCLC tumor cells are in a different cell state from PNECs and are primed for the fate change by Notch activation. Future comparative transcriptome analysis will provide additional insights into this important issue.

Tumor cell behavior not only depends on the interactions with stromal cells but also is influenced by the interactions with tumor cell variants that fulfill a distinct role in the tumor tissue. SCLC tumors have few infiltrating stromal cells. Numerous clinical observations indicate that SCLC tumors have a high degree of plasticity to make their own diverse microenvironment. Heterogeneity in SCLC endows the ability of SCLC tumors to adapt to different microenvironment and therapeutics. Our single-cell transcriptional profiling revealed the expression of Non-NE markers such as HES1 and CC10 in freshly isolated mouse SCLC tumor cells, consistent with the antibody immunostaining analysis. In addition, we identified a cell population induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy, characterized by a mesenchymal feature. This observation is consistent with a recent report that cisplatin resistance is associated with EMT-related genes observed in a human SCLC PDX model by scRNA-seq analysis (46). scRNA-seq of isolating pure tumor cells can be used in a time course study to investigate the cell state transition during tumor progression, in conjunction with chromatin state analysis by single-cell epigenomics. Furthermore, scRNA-seq analysis of Rbpj KO and Yap/Taz KO SCLC tumors will provide more insights into the molecular mechanisms of how the intratumoral heterogeneity of SCLC is established and regulated by the interplay of Notch pathway and YAP/TAZ. It should be noted that the composition of mouse Non-NE tumor cells is dependent on genetic mutation or cell origin of tumor. SCLC tumors initiated by Adeno-CMV-Cre virus have more Non-NE tumor cells. YAP can induce CC10-negative Non-NE tumor cells in the absence of Notch pathway. These observations imply a potential mechanism of adaptive resistance during the therapy and highlight the importance of understanding the regulatory programs for the generation of intratumor heterogeneity.

Our work links the YAP-mediated fate conversion of NE to Non-NE tumor cells and the development of acquired therapeutic resistance using CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice. One of the caveats in this study is that it is unclear whether the resistance is due to the fate change of the tumor cells, intrinsic mechanism of YAP-induced chemoresistance in NE cells, or non–cell-autonomous effect of the Non-NE tumor cells, because YAP-expressing NE tumor cells quickly converted into Non-NE cells in CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAPS127A mice after dox was administrated. It would be interesting to test whether the blockage of Non-NE differentiation would lead to the chemoresistance in NE cells after YAP activation. Another caveat is that our CgrpCreER model targets the whole cluster of NEB, not a single PNEC cell. It is possible that the intratumoral heterogeneity is generated by the subpopulation of PNECs within the NEB. Confetti or rainbow reporter mice may help to elucidate this issue. Chemotherapy induces the YAP expression and EMT in NE SCLC tumor cells. EMT-regulating transcription factors have been linked to anticancer drug resistance (51). Recently, inducing ferroptosis has been demonstrated to be an effective way to kill the therapy-resistant high-mesenchymal cancer cells (52). One study showed that Non-NE SCLC tumor cells are more sensitive to the ferroptosis inducer (53). Thus, targeting different cell death routes is a plausible way for treating chemonaive and chemoresistant SCLCs.

It has become increasingly apparent that abnormalities in the upstream and downstream members of the Hippo pathway play important roles in the tumorigenesis of various human cancers. YAP/TAZ activation is a major mechanism of intrinsic and acquired resistance to various targeted chemotherapies and immunotherapies (44). The overexpression of YAP has also frequently been observed in non-SCLC. In the present study, we revealed the roles of YAP not only in determination of NE features but also in chemoresistance of SCLC tumors. Because of the short lifetime of tumor-bearing CgrpCreER;TKO mice (less than 2 months after SCLC tumor initiation), it is difficult to model the acquired resistance to cisplatin/etoposide in CgrpCreER;TKO mice. Further study using a xenograft tumor model may resolve this issue. Direct YAP/TAZ/TEAD inhibitors are currently under development (54). It is possible that combination therapy with YAP/TAZ inhibitors might be beneficial to chemoresistant patients with SCLC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal husbandry

Rosa26mTmG, Rosa26rtTA, and floxed Pten mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Floxed Rbpj mice were provide by H. Han, floxed Yap mice were provided by D. Pan, and floxed Taz mice were provided by N. Tang. CgrpCreER and SpcCreER mice have been previously reported (26, 55). Floxed Trp53, floxed Rb1, and KrasLSL-G12D mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute Mouse Repository. To produce the TetOn-YAPS127A and TetOn-YAP5SA mice, Flag-YAPS127A and Flag-YAP5SA were placed under the control of TRE (Tetracycline response element)-tight promoter, and the TRE-YAPS127A (YAP5SA)–polyA cassette was flanked by the insulators. DNA was linearized and introduced into C57/BL6 zygotes by pronuclear injection to produce transgenic mice. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Zhejiang University approved all experiments performed in this study.

Patient samples

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University in accordance with the U.S. Common Rule. We queried for patients diagnosed with SCLC and LUAC between 1 January 2003 and 1 January 2020 from the Cancer Clinical Research Database at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. We then retrospectively reviewed the available clinical data from the samples to retrieve information about patient clinical staging, treatment response, etc. LDH concentrations were measured by the clinical laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. Computed tomography (CT) images were provided by the medical imaging department. All participating patients provided written informed consent for blood and tumor collection and data analysis.

Cell culture and lentiviral transduction

Mouse and human SCLC cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. For lentiviral production, the mixture of pMD2.G, pSPAX2, and lentiviral plasmids (2:3:4) was introduced into human embryonic kidney–293T. Media containing lentivirus were collected 48 and 72 hours after transfection. For the derivation of mouse SCLC cell lines, tumors were dissected and mechanically disaggregated in collagenase IV (600 U/ml) and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) (2 μg/ml) of RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were passed through a 100-μm cell strainer to remove larger aggregates. Cells were cultured until suspending aggregates and adherent cultures appeared. The suspending and adherent cells were split to culture separately for several passages until they formed stable cell lines. Chemicals are listed in table S1.

Tamoxifen, dox administration, and intratracheal delivery of adenovirus

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in corn oil to make a stock solution of 50 mg/ml. To induce tumor formation, tamoxifen [2 mg/25 g (body weight)] was injected into adult mice daily three times. Drinking water with dox at 1 mg/ml was given to the mice at indicated time points to induce YAPS127A or YAP5SA expression in transgenic mice. Adeno-CMV-Cre virus was purchased from HanBio. Virus (1 × 108 plaque-forming units) was intratracheally delivered into mouse lungs. Lungs were collected for analysis at indicated time points.

Flow cytometric analysis for YAP expression

CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mouse lungs with tumors were collected after being perfused with ice cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by mechanical disruption with scissors. The minced tissues were incubated with collagenase IV (600 U/ml) and DNase (2 μg/ml) for a maximum of 45 min at 37°C. The digested tissue was separated through a 70- and 40-μm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension. Cells were spun down at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and treated with 1× red blood cell lysis buffer (BioLegend). Lung cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at 4°C and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Cells were blocked in 1% FBS/PBS for 1 hour and followed by incubation with rabbit anti-YAP antibody (1:100) (Beyotime) for 2 hours. After three washes with 1% FBS/PBS, cells were incubated with Pacific Blue– or Brilliant Violet 421–conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min. Tumor cells were identified with the expression of GFP proteins.

Cisplatin and etoposide treatments

The high-dose acute chemotherapy was as follows: cisplatin [7.5 mg/kg (body weight)] on day 1 and etoposide [15 mg/kg (body weight)] on days 2 and 4 by intraperitoneal injection. For scRNA-seq, mice were treated with vehicle or cisplatin [5 mg/kg (body weight)] every 4 days for 2 weeks. For the survival curve study, animals were injected with cisplatin (5 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection once a week.

Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was subjected to quantification by real-time PCR using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Relative quantification was expressed as 2−△Ct, and glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase was used as a control. Quantitative PCR primers are listed in table S2.

Dual luciferase reporter analysis

For luciferase assay, cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and transfected with pGL3-basic, Rest luciferase reporter plasmid together with β-gal vector and indicated plasmids. Thirty-six hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System following the manufacturer’s instructions. All luciferase activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Mouse lungs were perfused with PBS through the right ventricle and inflated with 1 ml of 2% PFA and fixed for 8 hours at 4°C in 2% PFA. After dehydration and processing, lungs were embedded in paraffin for sectioning and immunohistochemistry. All the tissues were sectioned at 6-μm thickness for histological analysis. For immunohistochemical or immunofluorescence staining, paraffin sections were stained as previously described (26). Citrate-based solution (pH 6.0; 0.01 M) was used for antigen retrieval. Primary antibodies are listed in table S1. Sections developed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen were counterstained with hematoxylin. For YAP staining, biotinylated secondary antibody and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used in combination with fluorogenic substrate Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 tyramide (1:200; TSA kit, PerkinElmer).

Microscopy imaging

Fluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon confocal microscope. Adjustment of red/green/blue histograms and channel merge were performed by ImageJ or Photoshop. To examine cell death morphology, cells were treated as indicated in six-well plates. Bright-field images of cultured cells were captured using an Olympus IX71 microscope. The images were processed using the ImageJ or Photoshop program. All image data shown were representative of at least three randomly selected fields.

Effects of drug treatment on cell viability and cell death

Mouse or human SCLC cells were seeded into a 12-well or 6-well plate. Cells were treated with cisplatin or etoposide as indicated with the time and concentration and subjected to microscopy imaging, cell viability/death, or immunoblotting analyses. Viability was detected using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. LDH release was measured to analyze cell death using the cytotoxicity assay kit (BioTime) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting

Cells were seeded on round glass coverslips and subjected to the indicated treatment. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Then, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C after blocking with 3% BSA/PBS for 30 min at room temperature and followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor–labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For Western blotting, cells were lysed in 1× SDS sample buffer and denatured by heating at 100°C for 10 min. Proteins were separated on 8 or 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blotting images were captured by ChemiScope5600 (Clinx, Shanghai) with enhanced chemiluminesence substrate.

ChIP assay

ChIP assays were performed using SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kits (Cell Signaling Technology, #9003) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, CgrpCreER;TKO;TetOn-YAP5SA NE SCLC cells were fixed with formaldehyde after 72 hours of dox (0.1 μg/ml) treatment. Anti-Flag antibody and mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) were used for ChIP. All ChIP signals were normalized to the input DNA, and relative fold change was compared with IgG control. Primer sequences are provided in table S2.

RNA-seq library preparation and data analysis

Total RNA extracted from cells was qualified and quantified using a NanoDrop and Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Then, first-strand cDNA was generated using random primers after the purified mRNA was fragmented into small pieces. A second-strand cDNA was synthesized. A-Tailing Mix and RNA Index Adapters were added to the end of the cDNA. The cDNA fragments were amplified by PCR. The product was qualified and quantified on the Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. The PCR products were then denatured by heat and circularized by the splint oligo sequence to get the final library. The single-strand circle DNA was formatted as the final library. Sequencing was performed on the BGIseq2000 platform (BGI-Shenzhen, China).

Sequencing reads were filtered and trimmed with trim_galore (v1.12) to remove low-quality reads and adaptors. Cleaned reads were mapped against the mouse genome (mm10) with STAR (v.2.4.2) using the following parameters “--outFilterMismatchNmax 2 --outSJfilterReads Unique --quantMode GeneCounts”. Gene expression was calculated as RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). Only genes that were expressed in at least one sample were retained for further analyses. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by DESeq2 (fold change of >4, Padj of <0.05, negative binomial generalized linear model fitting, and Wald test). Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses were performed using clusterProfiler package in R. GSEA was performed using GSEA 2-2.2.4 (minimum size: exclude smaller sets = 5, number of permutation = 10), and the gene sets are listed in data files S1 and S2.

scRNA-seq library preparation and data processing

For scRNA-seq, lung tumors were harvested 60 days after tamoxifen injection from CgrpCreER;TKO;Rosa26mTmG mice treated with vehicle or cisplatin [5 mg/kg (body weight)] every 4 days for 2 weeks. Tumors were processed by enzymatic dissociation with collagenase IV (600 U/ml) and DNase (2 μg/ml) for a maximum of 45 min and neutralized in collection buffer (10% FBS in RPMI 1640). Dissociated live cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting with GFP fluorescent protein for downstream single-cell transcriptomic analyses. A total of 5000 cells from vehicle and 5000 cells from cisplatin-treated tumors were loaded per lane on the 10x Genomics platform and processed for complementary cDNA synthesis and library preparation as suggested by the manufacturer’s protocol.

scRNA-seq data were processed by the Cell Ranger toolkit (version 2.0.2, 10x Genomics) for read alignment, barcode processing, and single-cell transcript quantification. The paired-end reads were aligned to the mm10 mouse reference genome and transcriptome provided by 10x Genomics. We used the filtered gene-cell count matrix from Cell Ranger for downstream analysis. Cells with lower than 1000 detected genes or with higher than 15% of total UMIs (unique molecular identifiers) originating from mitochondrial RNAs were removed. After filtering, we obtained 3699 and 4245 cells for the vehicle and chemotherapy samples, respectively. Gene expression in each sample was transformed and normalized using the “Normalize Data” function in Seurat package version 3.0.1 (56). For dimension reduction, we first selected the highly variable genes using the FindVariableFeatures function (Mean VarPlot mode, 0.1 < mean < 8, dispersion > 1) in Seurat. We then performed PCA and selected the most significant 20 PCs for each sample according to the “knee” point at the cumulative curve of SDs of each PC. Cell clusters were identified using the Seurat FindNeighbors function with the number of k-nearest neighbor set to 150 and FindClusters function with the resolution set to 0.1. The clusters were visualized on a two-dimensional t-SNE map, implemented by the Seurat package with the perplexity = 30. For each cluster, DEGs were identified by comparing this cluster with the rest clusters using the MAST (Model-based Analysis of Single-cell Transcriptomics) method. The top 10 most significant DEGs (log2 fold change > 0.2; detected in at least 20% cells within the cluster) were shown in the heatmap plots as cell type markers. We calculated Spearman’s correlations of clusters between vehicle and chemotherapy samples. GSEA was performed using GSEA 2-2.2.4 software (minimum size: exclude smaller sets = 5 and number of permutation = 10) with hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (V7.1). All gene sets can be viewed in data file S3.

For multiple testing, P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. EMT scores were calculated on the basis of EMT signatures, as described previously (57). All statistical analyses were performed using the R software program.

Statistical analysis

For quantitative reverse transcription PCR data expressed as relative fold changes, Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s test were used for pairwise comparisons and multigroup comparison, respectively. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant. Equal variances were assumed. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Zheng for generating TetOn-YAPS127A and TetOn-YAP5SA transgenic mice and N. Tang for Taz floxed mice. Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2019YFA0802003) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31970727, 81802887, and 81670350). Author contributions: Q.W. and H.S. conceived experiments. Q.W. and Y.L. carried out most of the experiments. J.G. and L.S. performed bioinformatics analysis. Q.Z., C.W., X.C., L.M., X.X., and M.W. performed clinical analysis. X.L. characterized TetOn-YAPS127A and TetOn-YAP5SA transgenic mice. C.L., P.X., and D.F. contributed to intellectual inputs. H.S. supervised the entire project and wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: C.L. is a full-time employee of Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co. Ltd. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database with accession nos. GSE161742, GSE161740, and GSE161741. Resources or reagents related to this paper can be provided by the corresponding authors pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests should be submitted to the corresponding authors.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 and S2

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Data files S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Nicholson A. G., Chansky K., Crowley J., Beyruti R., Kubota K., Turrisi A., Eberhardt W. E. E., van Meerbeeck J., Rami-Porta R.; Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions , The international association for the study of lung cancer lung cancer staging project: Proposals for the revision of the clinical and pathologic staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11, 300–311 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gazdar A. F., Bunn P. A., Minna J. D., Small-cell lung cancer: What we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 725–737 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabari J. K., Lok B. H., Laird J. H., Poirier J. T., Rudin C. M., Unravelling the biology of SCLC: Implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 549–561 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horn L., Mansfield A. S., Szczęsna A., Havel L., Krzakowski M., Hochmair M. J., Huemer F., Losonczy G., Johnson M. L., Nishio M., Reck M., Mok T., Lam S., Shames D. S., Liu J., Ding B., Lopez-Chavez A., Kabbinavar F., Lin W., Sandler A., Liu S. V.; IMpower133 Study Group , First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2220–2229 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ready N. E., Ott P. A., Hellmann M. D., Zugazagoitia J., Hann C. L., de Braud F., Antonia S. J., Ascierto P. A., Moreno V., Atmaca A., Salvagni S., Taylor M., Amin A., Camidge D. R., Horn L., Calvo E., Li A., Lin W. H., Callahan M. K., Spigel D. R., Nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small cell lung cancer: Results from the CheckMate 032 randomized cohort. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 426–435 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marusyk A., Janiszewska M., Polyak K., Intratumor heterogeneity: The rosetta stone of therapy resistance. Cancer Cell 37, 471–484 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shue Y. T., Lim J. S., Sage J., Tumor heterogeneity in small cell lung cancer defined and investigated in pre-clinical mouse models. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 7, 21–31 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim J. S., Ibaseta A., Fischer M. M., Cancilla B., O’Young G., Cristea S., Luca V. C., Yang D., Jahchan N. S., Hamard C., Antoine M., Wislez M., Kong C., Cain J., Liu Y.-W., Kapoun A. M., Garcia K. C., Hoey T., Murriel C. L., Sage J., Intratumoural heterogeneity generated by Notch signalling promotes small-cell lung cancer. Nature 545, 360–364 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falco J. P., Baylin S. B., Lupu R., Borges M., Nelkin B. D., Jasti R. K., Davidson N. E., Mabry M., v-rasH induces non-small cell phenotype, with associated growth factors and receptors, in a small cell lung cancer cell line. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 1740–1745 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mabry M., Nakagawa T., Nelkin B. D., McDowell E., Gesell M., Eggleston J. C., Casero R. A. Jr., Baylin S. B., v-Ha-ras oncogene insertion: A model for tumor progression of human small cell lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 6523–6527 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calbo J., van Montfort E., Proost N., van Drunen E., Beverloo H. B., Meuwissen R., Berns A., A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 19, 244–256 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]