Abstract

The general mechanisms by which ESCRTs (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport) are specifically recruited to various membranes, and how ESCRT subunits are spatially organized remain central questions in cell biology. At the endosome and lysosomes, ubiquitination of membrane proteins triggers ESCRT-mediated substrate recognition and degradation. Using the yeast lysosome/vacuole, we define the principles by which substrate engagement by ESCRTs occurs at this organelle. We find that multivalent interactions between ESCRT-0 and polyubiquitin are critical for substrate recognition at yeast vacuoles, with a lower-valency requirement for cargo engagement at endosomes. Direct recruitment of ESCRT-0 induces dynamic foci on the vacuole membrane and forms fluid condensates in vitro with polyubiquitin. We propose that self-assembly of early ESCRTs induces condensation, an initial step in ESCRT assembly/nucleation at membranes. This property can be tuned specifically at various organelles by modulating the number of binding interactions.

Multivalent interactions between ESCRT-0 and polyubiquitin induce condensate formation and cargo sorting at vacuoles/lysosomes.

INTRODUCTION

ESCRT family members consist of a group of proteins involved in controlling diverse membrane-remodeling biochemical reactions, which include multivesicular body biogenesis, HIV budding, cytokinesis, and membrane repair (1). Many of these occur at different membrane locations in the cell (endosome, lysosome, plasma membrane, and the nucleus). Although the molecules that recruit ESCRTs are mostly known, the general principles of recruitment are less well understood. The mechanisms by which ESCRT reactions are spatially controlled remain unclear. In addition, while the structures of the individual subunits of the ESCRT complexes have been for the most part solved (2–5), the mesoscale structural organization of early ESCRTs on the membrane is unclear.

At endosomes during multivesicular body biogenesis, ubiquitinated membrane proteins (cargo) recruit ESCRT-0, which then recruits the downstream proteins ESCRTs I, II, and III (6). Therefore, ubiquitination serves as a signal to recruit ESCRTs to the endosomal membrane. The ESCRT-I complex has two ubiquitin binding motifs: ESCRT-II has one ubiquitin binding motif (7), and the complex of ESCRT-0 contains at least five ubiquitin binding motifs [one VHS (Vps27, Hrs and STAM) UIM (ubiquitin-interacting motif) motifs in the ESCRT-0 protein Vps27, and one VHS and one UIM motif in the ESCRT-0 protein Hse1] (7). Therefore, the ESCRT-0 complex is a critical component of the pathway that controls cargo binding. Furthermore, ESCRT-0 has been reported to form tetramers, oligomers and clusters (8, 9). In vivo cargo sorting occurs at hotspots (10–12), demonstrating cargo concentration at specific sites, although the mechanism of this organization is not understood. The presence of multivalency for ubiquitin binding in ESCRT-0 and the knowledge of the existence of poly-ubiquitinated cargo as substrate suggest higher-order assembly of these complexes, as demonstrated for various multivalent interactions (13–15).

In this study, to understand the principles of ESCRT and cargo organization at membranes, we set out to delineate the properties of ESCRT’s initial recruitment and assembly at two similar but separate organelles in yeast endosomes and vacuoles (yeast lysosomes). We recently described the mechanism of ESCRT-mediated lysosomal protein recognition and degradation via ubiquitination of lysosomal membrane proteins (16). While studying the requirements of vacuolar membrane protein recognition by ESCRTs, we find that polyubiquitination is critical for efficient ESCRT recognition at the vacuole. Higher valency of ubiquitin is more critical for cargo sorting at the vacuole than at endosomes. Polyubiquitinated proteins associate with ESCRT-0, leading to self-assembly of ESCRT-0 and cargo into dynamic condensates, which may provide a platform for nucleation of downstream ESCRT complexes.

RESULTS

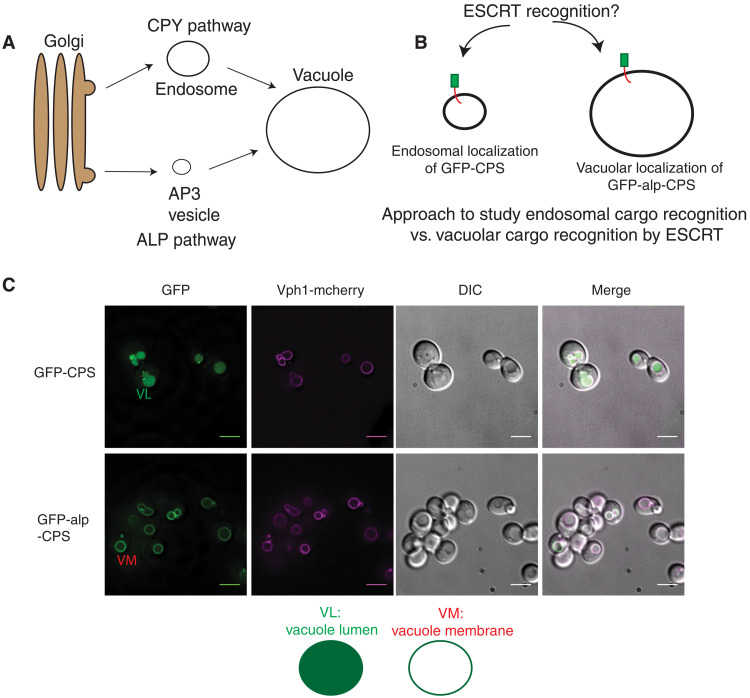

As a model cargo to study ESCRT assembly principles at endosomal and vacuolar membranes, we used the vacuolar protease carboxy-peptidase S (CPS), which is transported to the vacuole from the Golgi via the endosomal pathway (17). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)–CPS is sorted into multivesicular bodies by the action of ESCRTs and is then trafficked to the vacuolar lumen for degradation (Fig. 1, A and C). Therefore, GFP-CPS is localized in the vacuolar lumen (Fig. 1C). In ESCRT mutants (for example, in the ESCRT-0 mutants vps27∆ or hse1∆), GFP-CPS gets stuck at aberrant endosomes (also called class-E compartments or “E-dots”) (fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Engineered CPS routed through the AP-3 pathway localizes to the vacuolar membrane.

(A) Model of carboxy peptidase S (CPS) and ALP trafficking to the vacuole. CPS traffics through the “CPY pathway”/endosome where MVBs are formed by ESCRTs. The ALP-pathway forms separate vesicles that traffic proteins like the alkaline phosphatase to the vacuole. (B) Model for the localization of GFP-CPS and GFP-alp-CPS at two sites where ESCRTs can function, providing a tool to study the same cargo at two membrane locations in the cell. (C) GFP-CPS or GFP-alp-CPS in wild-type strains expressing Vph1-mcherry. Vph1 is a vacuolar membrane protein. Scale bars, 5 μm. Model figure below describes localization pattern of vacuolar luminal (VL) or vacuolar membrane (VM) signals.

While Golgi-endosome-vacuole is one route for proteins to get to the vacuole lumen, another route to the vacuole is through the AP-3 pathway (Fig. 1A). When GFP-CPS is rerouted to the vacuole membrane by adding an AP-3 recognition site (hereafter called GFP-alp-CPS, “alp” for the “alp pathway”), the protein remains at the vacuole membrane (Fig. 1C) (17). These two proteins (GFP-CPS and GFP-alp-CPS) therefore provide us with almost identical cargoes that traffic to the vacuole via two independent vesicular compartments. This design allows us to probe the properties that ESCRTs use for the same protein to be recognized at two different physical locations in the cell.

Our previous study indicated that ESCRTs are able to recognize ubiquitinated membrane proteins at the vacuole membrane as well, in addition to endosomes (16). Considering that GFP-alp-CPS is stable at the vacuole membrane and does not get internalized into the lumen, we tested whether conjugating CPS with ubiquitin induces ESCRT-mediated cargo internalization. We found that when a single ubiquitin is conjugated at the N terminus of GFP-alp-CPS, the protein now gets internalized into the lumen, in a Vps27-dependent fashion (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S1).

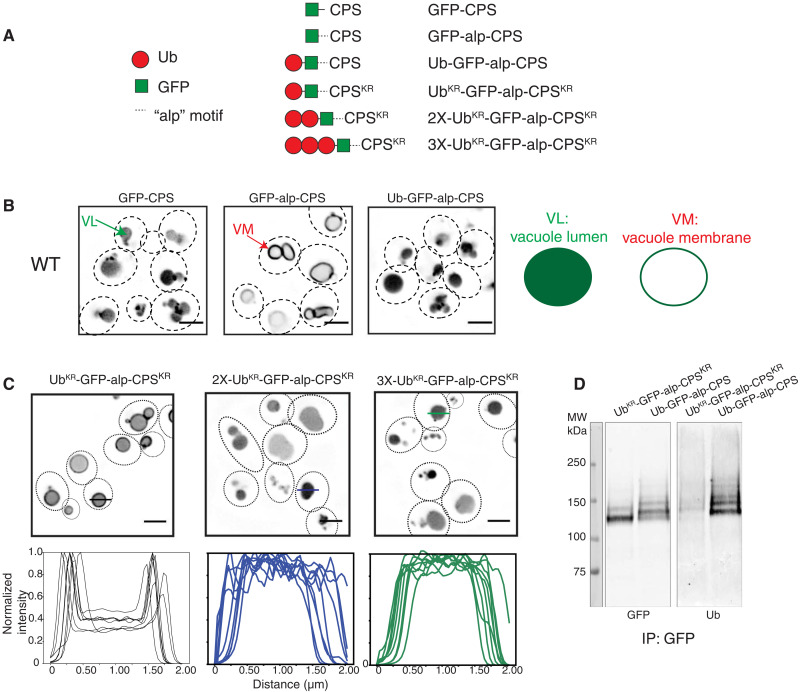

Fig. 2. Polyubiquitination is required for efficient ESCRT-dependent cargo sorting at the vacuole.

(A) Different CPS constructs used in this experiment. (B) Localization of the CPS constructs as listed on top of the figures in a wild-type (WT) strain. The dotted lines represent outlines of yeast cells as imaged through the differential interference contrast (DIC) channel. For simplicity, the DIC channel is not shown, but some images with the DIC channel are shown in Fig. 1. Note that VL denotes vacuolar lumen, and VM denotes vacuole membrane. Right: A model of different variants of GFP-CPS localizing in the VL or VM. Scale bars, 2 μm. (C) Localization of the GFP-CPS constructs as denoted in the figure. UBKR has all the lysines mutated to Arg. Intensity profiles on the bottom represent line scan across the vacuoles. Representative lines are shown across three vacuoles (black, blue, and green lines) in the microscopy images. Scale bars, 2 μm. (D) Immunoblots of UBKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR (lysine-less substrate) and Ub-GFP-alp-CPS after performing immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-GFP. These experiments were performed in a doa4∆ pep4∆ prb1∆ background strain.

Following this observation, we asked whether a single ubiquitin is sufficient for complete internalization of GFP-alp-CPS on the vacuole membrane. Therefore, we used a lysine-less ubiquitin molecule (where all the seven lysines are mutated to arginines) to probe the effect of a polyubiquitin-deficient cargo. CPS normally gets ubiquitinated on K8 and K12 residues (18), which were mutated to Arg in this construct and hereinafter called UbKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR (Fig. 2A).

We found that the internalization of this polyubiquitin-deficient cargo is inhibited, and a large fraction of it remains at the vacuole membrane (Fig. 2C). Compared with the wild-type ubiquitin containing lysines, the lysine-less protein does not form polyubiquitin chains (Fig. 2D). If the number of the lysine-less Ub molecules is increased making 2X-UbKR or 3X-UbKR, then internalization to the lumen is rescued (Fig. 2, A and C).

Vacuole-targeted membrane-protein cargoes are ubiquitinated through the action of E3 ligases such as Rsp5, Tul1, and Pib1 (19). Deletions of Rsp5 adaptors Ssh4 and Ear1, in addition to Tul1 and Pib1, had a severe defect in internalization of the vacuolar-membrane cargo Ub-GFP-alp-CPS (fig. S2). These data provide further evidence that a higher level of ubiquitination (or polyubiquitination) is required for the vacuolar membrane protein to be recognized and sorted by ESCRTs.

Therefore, the vacuolar membrane proteome is susceptible to regulation through the ESCRT pathway, and polyubiquitination of cargo is necessary for efficient sorting and degradation. To study the effect of the number of ubiquitin molecules on vacuolar protein cargo in a controlled fashion, we used a previously established rapamycin-dependent degradation system (16). In this system, the protein/cargo of interest is tagged with FKBP, and the yeast strain also contains an FRB molecule conjugated with ubiquitin. This system allowed us to control the number of ubiquitin molecules conjugated to the cargo of interest by following the kinetics of cargo sorting and degradation after addition of rapamycin, which triggers FRB-FKBP binding.

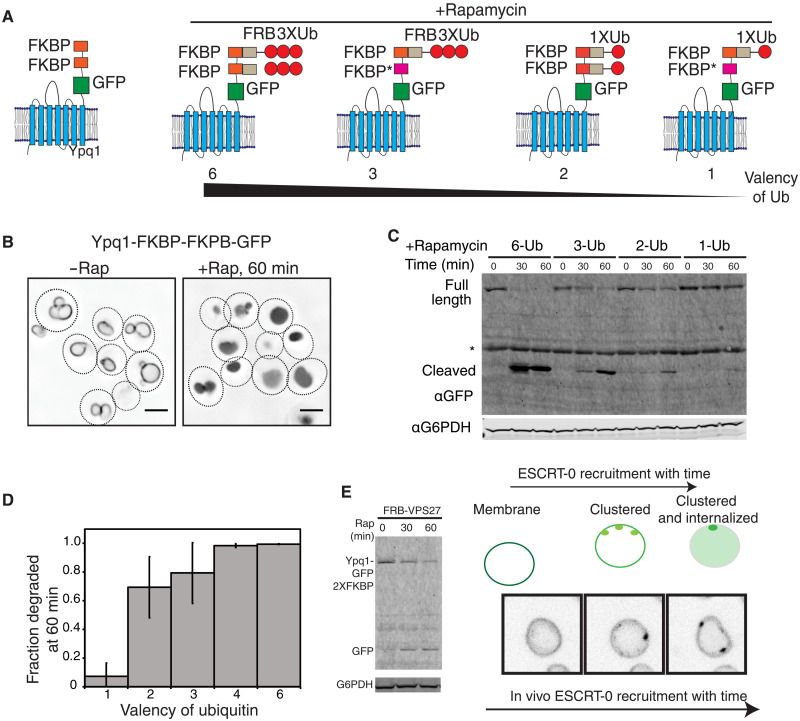

A 2XFKBP (two FKBP molecules fused in tandem) in the presence of FRB-3XUb (three ubiquitin molecules in tandem) was effective in inducing ESCRT-mediated sorting of the vacuolar lysine transporter Ypq1 (20). We modified the valency of ubiquitin bound to the cargo by mutating one of the FRB-binding sites in FKBP (called FKBP*) and by using single- or triple-ubiquitin molecules fused to FRB (Fig. 3A). In cargo sorting assays, we found a strong dependence on the number (valency) of ubiquitin fused to FRB (Fig. 3, A to D, and fig. S3, A and B). The same effect is also observed when we used an orthogonal cargo Vph1, with the number of effective ubiquitin molecules controlling the level of internalization into the vacuolar lumen (fig. S3C).

Fig. 3. Multivalent interactions drive cargo clustering and sorting at the vacuole.

(A) Models of Ypq1 and the FRB constructs used in (B) to (D). FKBP* contains mutations on the FRB-binding sites. (B) Localization of Yqp1 constructs with and without rapamycin addition for 60 min. (C) Immunoblots for GFP after addition of rapamycin for the indicated times. The free GFP band appears and increases in intensity as the full-length protein gets internalized into the vacuole lumen. (D) Quantification of the fraction GFP degraded into the vacuole lumen, at 60 min, from the data in (C). (E) Recruiting FRB-Vps27 onto the vacuolar cargo Ypq1-GFP-2XFKBP induces degradation of the cargo. (E) Recruitment of FRB-Vps27 onto the vacuole via binding to Ypq1-GFP-2XFKBP also induces formation of foci on the surface of the vacuole.

To assess whether direct recruitment of ESCRTs to the vacuolar cargo can cause degradation of the cargo, we fused the ESCRT-0 protein Vps27 to FRB. This construct is fully functional and identical to the activity of the wild-type Vps27 (fig. S4), as it can fully complement the defect of a vps27∆ strain for two different cargo sorting reactions (Mup1-pHluorin and Can1 through a canavanine-sensitivity assay) (21).

Upon rapamycin-induced recruitment of Vps27 in this system, the modified cargo Ypq1 (fused to 2XFKBP) internalized into the vacuolar lumen and degraded over time (Fig. 3E). We also observed formation of distinct foci of the cargo at the vacuole surface upon adding rapamycin (Fig. 3E and fig. S5). These foci are dynamic in nature; they move over time (movie S1 and fig. S5) and occasionally fuse with one another. Some clusters disappear over time, presumably as the cargo gets internalized into the lumen (movie S1 and fig. S4C). The foci also tend to disappear more completely upon cycloheximide treatment to inhibit translation and therefore new synthesis of the cargo (fig. S4C).

When a lower-valency cargo construct is used instead, where one of the FKBP sites is mutated to abrogate FRB-Vps27 binding, rapamycin-induced cargo clustering and sorting are inhibited (fig. S6A). This lower-valency cargo molecule is able to bind to FRB-Vps27 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion (fig. S6B). Therefore, while ESCRT-0 is recruited, the valency of binding sites on the Ypq1 construct is critical to induce ESCRT-mediated cargo sorting.

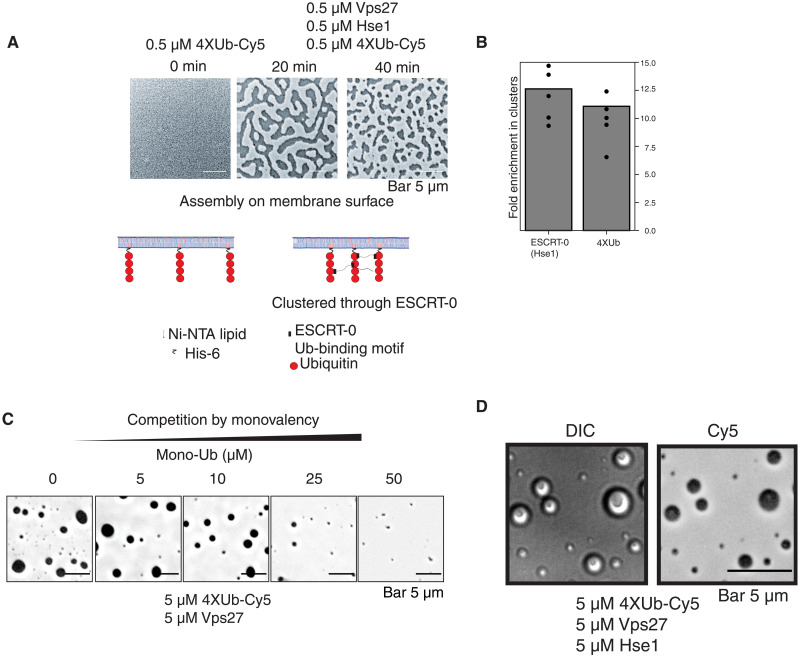

Our data therefore suggest that higher-valency interactions between ESCRT-0 and cargo induce clustering, sorting, and degradation. To understand the basis of cargo clustering induced by ESCRT-0, we purified the ESCRT-0 proteins Vps27 and Hse1 and reconstituted the assembly reaction in vitro, using His6-tagged ubiquitin as the model cargo. We fused four ubiquitin genes in tandem with one another and labeled this molecule with Cy5. Upon assembling this model ubiquitin with ESCRT-0, micrometer-sized condensates formed on supported lipid bilayers and in solution at low micromolar concentrations (Fig. 4, A to C). The concentrations required for formation of condensates are lower in the nanomolar range on supported lipid bilayers and in the micromolar range in solution (Fig. 4, A to C), implying robust formation of these assemblies. The structures also exhibit morphologies expected of liquid-like structures on membranes (Fig. 4A) (13) and undergo fusion on membrane and in solution (movies S2 and S3). The clusters concentrated both ubiquitin and ESCRT-0 (Hse1 labeled with Oregon Green) to approximately 10-fold (Fig. 4B). Inclusion of a single ubiquitin in the assay abrogated condensate formation, signifying the importance of ubiquitin valency in the self-assembly (Fig. 4B).

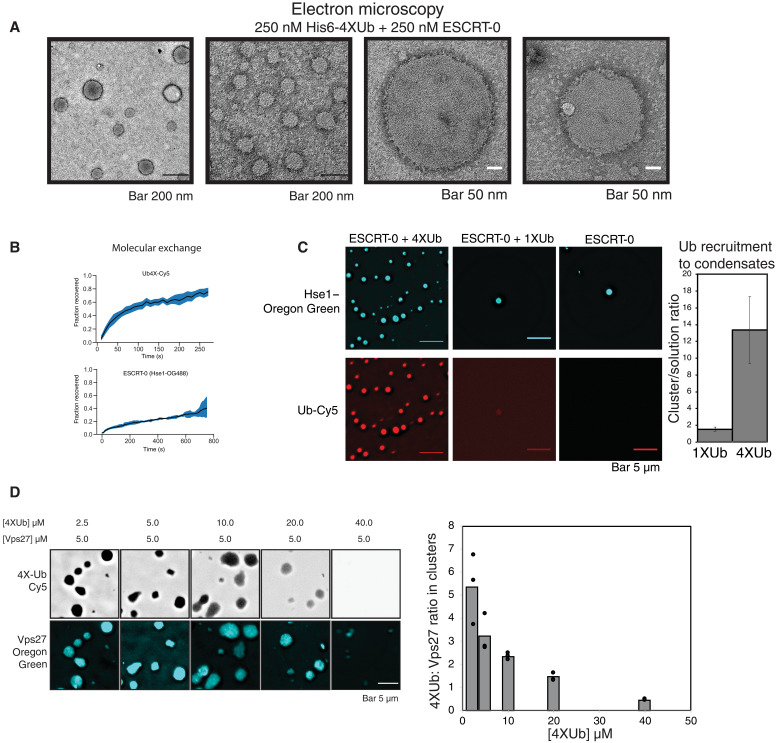

Fig. 4. ESCRT-0 and polyubiquitin coassemble into condensates.

(A) Assembly of Vps27-Hse1 and Cy5-labeled His6-4XUb on supported lipid bilayers consisting of 2% Ni-NTA–PE (phosphatidylethanolamine). Bottom model figure shows how 4XUb is associated with lipid bilayers. Model of ubiquitin binding motifs represent only a fraction of the ESCRT-0 complex. (B) Quantification of the density of 4XUb-Cy5 and Hse1–Oregon Green in the membrane clusters relative to the surrounding membrane. The bars denote average of the data from five clusters (denoted by the data points). (C) Competition experiment of the condensates with the inclusion of mono-ubiquitin at the mentioned concentrations. Protein components were combined, and fluorescence of Cy5 was imaged after 2 hours at room temperature. Experiments were performed in 25 mM bis-tris (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl. (D) Recombinant Vps27 and Hse1 were incubated with 4XUb-Cy5 and imaged after 2 hours at room temperature, showing DIC image on the left and fluorescence (of Cy5) on the right. Experiments were performed in 25 mM bis-tris (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl.

A wide range of condensate sizes down to nanometer scale are formed (Fig. 5C), as depicted by electron microscopy (Fig. 5A). Rough edges of the condensates down to the nanometer level and highly dense meshwork of proteins are reminiscent of network formation in such assemblies, as previously observed in other multivalent systems undergoing condensation (15, 22).

Fig. 5. Multivalent interactions drive ESCRT-0 and ubiquitin condensation.

(A) Electron microscopy images of the ESCRT-0 complex (Vps27/Hse1) with His6-4XUb. The structures form variable size distributions and are spherical in nature. Electron microscopy was performed at 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl. (B) Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of 4XUb-Cy5 and Hse1–Oregon Green. Three whole droplets were bleached to obtain the normalized fluorescence recovery curves. (C) Purified Vps27 and Hse1 were incubated with 4XUb and imaged after 2 hours at room temperature. 4XUb contains a His6 tag at the N terminus and also a cysteine that has been labeled with a Cy5 dye for visualization. Hse1 was labeled with Oregon Green maleimide. Right figure is a quantification of the level of monoubiquitin-Cy5 or tetraubiquitin-Cy5 recruitment in droplets made from respective proteins. (D) Droplet formation at different concentrations of 4XUb-Cy5 (50 nM labeled) with a fixed concentration of Vps27 (1% labeled). Figure on the right represents ratios of 4XUb to Vps27 at different concentrations of 4XUb.

These structures are dynamic since they exhibited molecular exchange (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; Fig. 5B). Ubiquitin exchanges more rapidly than ESCRT-0, most likely because ESCRT-0 self-associates to form oligomers [(8, 9) and see below for ESCRT-0 self-association]. Solvent conditions are important for their formation, as condensation was favored by acidic pH (fig. S7A). In the presence of 1XUb and ESCRT-0 (both Vps27 and Hse1), rare condensates that only weakly concentrated ubiquitin were observed (Fig. 5C). Condensate formation was possible but substantially inhibited with only Vps27 and Hse1, signifying weak self-association between the subunits of the ESCRT-0 complex (fig. S7B), probably owing to the higher-order oligomerization and association of the intrinsically disordered regions of the complex (fig. S6C).

Condensates did not form with only 4XUb or with 4XUb and Hse1 (fig. S7B). Without Hse1, the condensates of 4XUb and Vps27 were smaller (fig. S7B), as the valency of interaction is reduced. Consistent with a multivalency-mediated condensate phenomenon that exhibits a stoichiometrically undefined complex formation, the ratio of ubiquitin to ESCRT-0 varies as a function ubiquitin concentration (Fig. 5D). At the highest concentration of ubiquitin in this experiment, condensate formation is inhibited as the multivalent complexes are titrated off. To test whether the condensates localize nonspecific protein assemblies, we used a fluorescent His6-tagged Snf7 protein (an ESCRT-III protein that does not have specific binding sites for ESCRT-0 or ubiquitin) in our assays. Snf7 forms bright punctate structures (most likely Snf7 polymers) outside of the clusters (fig. S7C), suggesting that to localize to these ubiquitin clusters, Snf7 would require specific binding partners, a topic of further analyses in our future studies.

The aforementioned properties are hallmarks of biomolecular condensates—valency-dependent cluster formation, solvent conditions controlling condensation, dense internal organization, variable stoichiometry of the complexes, domains that exclude nonspecific proteins, structures that exhibit internal rearrangement of molecules, and exchange with the environment (14). These in vitro analyses strongly indicate condensate formation as the mechanism of ESCRT-0–mediated polyubiquitin clustering.

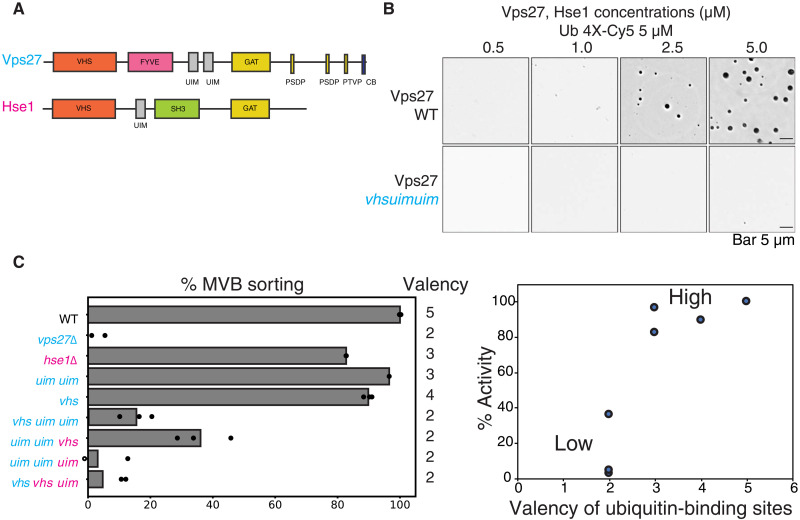

As predicted by this model, mutations in the ubiquitin-binding motifs of Vps27 (Vps27vhs uim uim) also inhibited condensate formation in vitro, as the valency of ubiquitin-binding motifs is decreased (Fig. 6, A and B). To study whether this valency dependence of ubiquitin-binding sites has any effect in vivo on cargo sorting, we used the model endocytosis cargo Mup1 and its sorting assays previously described ((23). We made combinations of several mutations on Vps27 and Hse1 and studied the effects of these mutations on Mup1 sorting to the vacuole. The data suggested a strong valency dependence on cargo sorting, in particular suggesting a regime of low activity toward sorting with lower-valency interactions and a higher activity regime with high-valency interactions (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6. ESCRT-0 multivalency drives condensation and cargo sorting reactions.

(A) Domain organization of the ESCRT-0 proteins Vps27 and Hse1. Vps27 contains three ubiquitin binding domains (a VHS and two UIMs), while Hse1 contains two (a VHS and a UIM motif). (B) Condensate formation with WT Vps27 or the Vps27 vhsuimuim mutant, in the presence of Hse1 and 4XUb-Cy5. Experiments were performed in 25 mM bis-tris (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl. The mutant Vps27 contains mutations in the VHS domain and mutations in the UIM motifs that abrogate ubiquitin binding. (C) Mup1-pHluorin sorting assay through flow cytometry with different ESCRT-0 mutants. Mutations were made in the ESCRT-0 components Vps27 and Hse1 at their VHS and UIM motifs. Cyan italics represent mutations in Vps27, and the magenta italics represent mutations in Hse1. Numbers on the right of the panel represent the number of ubiquitin binding sites present in the ESCRT-0 complex in the various mutants. Dots in the bars represent independent experiments, while the bars represent average sorting from three independent experiments. Right: Sorting activity (as obtained from F) for Mup1-pHluorin sorting as a function of ubiquitin valency in ESCRT-0.

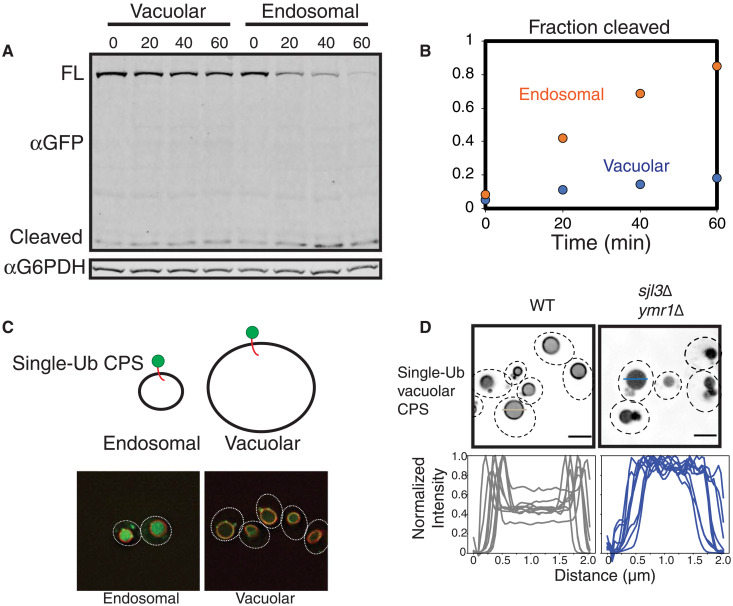

Our data therefore demonstrate a critical role of multivalent interactions during cargo sorting reactions and imply clustering by condensation as the mechanism behind this role. In addition to the endosomal cargo Mup1, higher-valency interactions through polyubiquitin and ESCRT-0 are also critical for cargo sorting reactions at the vacuolar membrane for several cargoes (GFP-alp-CPS, Ypq1, and Vph1). However, the internalization of the lysine-less GFP-CPS molecule (UbKR-GFP-CPSKR: note without the alp signal) that traffics through the endosome localizes to the lumen of the vacuole (Fig. 7, A and C), in contrast to the vacuolar cargo (Fig. 1). Therefore, the cargo recognition and internalization of this polyubiquitin-deficient membrane protein are more severely defective at the vacuolar membrane compared to the endosomal membrane. These effects are also observed when we follow the kinetics of degradation of the vacuole-targeted cargo compared with that of the endosome-targeted cargo. In this experiment, we used a galactose-inducible expression system, following the stability of the protein over time upon translation inhibition with cycloheximide (Fig. 7A). Although the proteins reach the endosome/vacuole membrane (Fig. 7C), the kinetics of degradation of the vacuole-targeted protein are slower than that of the endosome-targeted protein (Fig. 7, A and B). However, the rate of degradation can be enhanced with a 3X-UbKR–conjugated vacuolar CPS molecule (fig. S8). These data imply that lower-valency interactions are more efficient for cargo sorting at endosomes than at vacuolar membrane.

Fig. 7. Differential dependence of valency on cargo sorting of endosomal and vacuolar cargoes.

(A) Kinetics of the degradation of UBKR-GFP-CPSKR (endosomal) and UBKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR (vacuolar) proteins upon induction of expression for 20 min and further inhibition of translation with cycloheximide addition. The zero time point represents 20 min of GAL induction with no cycloheximide. (B) Quantification of the fraction of GFP cleaved of the data from (A). (C) Localization of the UBKR-GFP-CPSKR (endosomal) and the UBKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR (vacuolar) constructs after inducing the expression for 20 min through the GAL promoter and then stopping translation through cycloheximide addition for 30 min. Vacuoles are labeled with Vph1-mcherry in red. (D) Localization of the indicated UBKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR (vacuolar cargo) in the PI3P phosphatase mutant ymr1∆ sjl3∆. Intensity profiles on the bottom represent line scan across the vacuoles. Representative lines are shown across two vacuoles (gray and blue lines) in the microscopy images. Scale bars, 2 μm.

Endosomes are sites where the density of ESCRTs is high (24). We reasoned that because of the higher density of ESCRTs at the endosomes, there is a lower requirement for multivalent interactions to recruit and condense ESCRTs at this organelle, as opposed to the vacuolar membrane. One of the lipid species that recruit ESCRTs to the endosomal membrane is phosphatidyl-inositol-3P (PI3P). We hypothesized that an increase in PI3P density could, in turn, increase the density of ESCRTs, thereby reducing the requirement of higher-valency interactions at the vacuolar membrane. To test this prediction, we used the PI3P phosphatase mutants ymr1∆ and sjl3∆, which have previously been shown to increase the level of PI3P on the vacuole membrane (25). In the single mutants ymr1∆ and sjl3∆, the single-ubiquitin–conjugated vacuolar GFP-CPS (UbKR-GFP-alp-CPSKR) remains mostly on the vacuole membrane (fig. S9B). However, in the double mutant ymr1∆ sjl3∆, the molecule is enriched in the vacuole lumen (Fig. 7D). Therefore, the defective sorting of the substrate can be rescued by the local increase in density of PI3P at the vacuolar membrane. These latter experiments suggest how multivalent interactions and, in turn, condensate formation may function to create high-density cargo sorting sites at the vacuole membrane.

DISCUSSION

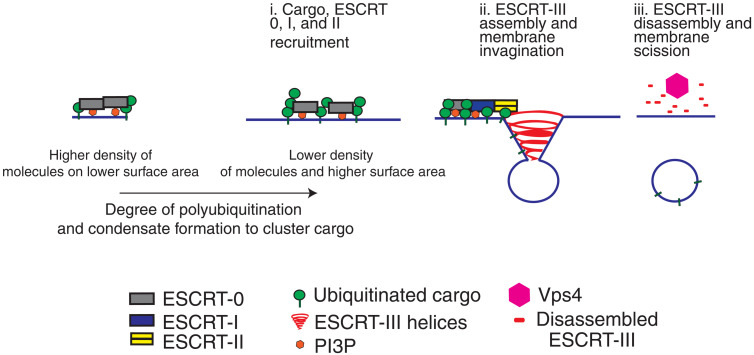

We provide evidence for two distinct mechanisms of recruitment and organization of ESCRT complexes at two separate membrane locations: the endosomes and the vacuole (Fig. 8). Our data suggest that one of the functions of the ESCRT-0 complex, by virtue of having multiple binding sites for ubiquitin, is to facilitate cargo clustering at the membrane through biomolecular condensation. ESCRT-0 by itself has a weaker ability to self-associate and undergo condensation. When substrates are polyubiquitinated, the multivalency of ESCRT-0 enhances formation of higher-order species of the ESCRT-0/cargo complexes. Increasing the density of PI3P increases the local concentration of ESCRT-0/ubiquitin on the membrane, thereby lowering the threshold for self-association (Fig. 4D and fig. S10). We note that in addition to the ubiquitination of the cargo, the reported ubiquitination of Vps27 (28) also could enhance multivalency and ESCRT-0 self-association. The general principles behind function of ESCRTs at membranes were proposed to include recruitment to membranes, “self-assembly,” and ESCRT-III polymerization (26). In the context of cargo sorting reactions, condensation would provide the basis of self-assembly, an initial event in ESCRT-mediated reactions.

Fig. 8. ESCRT-0 and polyubiquitin condensates create high-density cargo sorting sites on vacuolar membrane.

Model suggesting how variation of ESCRT and cargo density affects recruitment and condensation of early ESCRT and substrate on the surface of membranes. The condensation of early players in the pathway may nucleate downstream assembly, leading to ESCRT-III polymerization and membrane budding. At sites of lower-density ESCRT-binding modules (such as the vacuolar membrane in yeast), polyubiquitin-mediated condensation would be more critical for cargo sorting organization, compared with endosomes, with an already existing high density of ESCRTs.

Condensing cargo via early ESCRTs could provide multiple advantages in the cargo sorting process. The physical concentration of cargo could amplify sorting of cargo, increasing the specificity for cargo recognition by ESCRTs. Concentrating downstream ESCRT complexes at a particular location and increasing the dwell time on the membrane could also provide a platform for nucleation of ESCRT-III polymerization, as observed for actin assembly pathways through upstream condensing nucleators (27). The rapid dynamics of ubiquitin in the condensates could allow for facile dissociation of the cargo from ESCRTs. As opposed to an ordered assembly (such as that of a clathrin-coated pit) where there likely is no internal rearrangement of the polymeric subunits, a condensate consisting of a stoichiometrically variable complex most likely requires less energy for its disassembly. This may be the reason behind the design of such clusters for spatial organization on the membrane. Furthermore, condensation of ubiquitinated cargo could feedback to the ubiquitin-ligase machinery, allowing for enhanced ubiquitination of the cargo.

At locations in the cell where ESCRT-0 is not involved, other mechanisms of self-assembly may exist—in the case of HIV budding, the HIV Gag protein is known to form higher-order assemblies, which recruit downstream ESCRTs (29). Clustering and condensation of ESCRT recruiters, therefore, could be a general property of ESCRT-related systems.

Our data provide clues for how clustering of signaling molecules can be regulated at various locations in the cell. By changing the number of binding sites for a complex on the membrane, cells may be able to quickly adjust local concentrations of enzymes and signaling adaptors. Two-dimensional (2D) surfaces and their charge properties may also play an important role in the nucleation of condensates (30) and also promote membrane repair and remodeling (31, 32). The composition of the membrane therefore should play a critical role in controlling the formation and function of membrane-associated biomolecular condensates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids are listed in table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

Fluorescence microscopy

For microscopy purposes of steady-state distribution of GFP-CPS (and its derivatives), Ypq1-2XFKBP-GFP and Vph1-2XFKBP-GFP, the following procedure was used. Cells were grown on YPD (yeast extract, peptdone, and dextrose mixture). One milliliter of mid-log cells was centrifuged for 1 to 2 min at 10,000g and resuspended in 10 to 20 μl of Milli-Q water. Imaging was performed on a Deltavision Elite system with an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope using a 100×/1.4–numerical aperture (NA) oil objective. On the Softworx software, images were deconvolved using 10 iterations with the “conservative” method. Images were analyzed on ImageJ. Line scan images were analyzed after background subtraction and normalized to the range of 0 to 1 by dividing the intensities by the maximum intensity.

Live-cell imaging time-lapse microscopy was performed as follows. Chambered slides were first rinsed with Milli-Q water. Two-hundred microliters of concanavalin A (1 mg/ml) was applied to the glass slide for 1 min at room temperature. Excess concanavalin A was removed, and the slide was rinsed twice with 1 ml of Milli-Q water. Mid-log cells were centrifuged for 1 to 2 min at 10,000g and resuspended with minimal medium. Cells were incubated on the slides for 20 min and then rinsed twice with 1 ml of minimal medium. Imaging was then performed on a CSU-X spinning-disk confocal microscopy system (Intelligent Imaging Innovations), coupled to a DMI 6000B microscope (Leica), 100×/1.45-NA objective, and a EMCCD camera. Analysis was performed on Slidebook and ImageJ.

Timelapse of the 3D droplets (movie S3) was taken on the same CSU-X confocal microscope.

Timelapse of the clusters on supported lipid bilayers (movie S2) was taken on a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 60× objective.

GAL induction and cycloheximide chase assay

GFP-CPS constructs with a galactose inducible promoter (GAL) promoter consist of an estradiol-responsive element (33). For expression of the protein, cells were grown to mid-log, and then 100 nM β-estradiol was added to the medium for GAL induction. After 20 min, translation was stopped by adding cycloheximide (50 μg/ml). Samples were taken [5 ODs (optical density measurements) of cells] 20 min after adding β-estradiol and then at subsequent times as indicated in the figures.

Rapamycin-mediated FKBP-FRB interactions

Different versions of FRB-Ub, FRB-Vps27, and membrane proteins (Ypq1 and Vph1) were allowed to interact through rapamycin-triggered FKBP-FRB association. All rapamycin treatment assays were done similarly by adding rapamycin (1 μg/ml) to mid-log cells for different amounts of time before imaging or taking samples for immunoblots. FKBP* was made by mutating three different rapamycin-FRB–binding sites to ensure complete abrogation of FRB binding in our multivalent system. The sequences of human FKBP and FKBP* are provided below with the mutations highlighted in bold letters: FKBP, MGVQVETISPGDGRTFPKRGQTCVVHYTGMLEDGKKFDSSRDRNKPFKFMLGKQEVIRGWEEGVAQMSVGQRAKLTISPDYAYGATGHPGIIPPHATLVFDVELLKLE; FKBP*, MGVQVETISPGDGRTFPKRGQTCVVHYTGMLEDGKKAVSSRDANAPFKFMLGKQAAARGAEEGVAQMSVGQRAKLTISPDYAYGATAAAAAIPPHATLVFDVELLKLE.

Immunoblots

Western blots were performed as follows, as described before (34). A 5-OD equivalent of cells was collected by centrifugation at 4000g. After washing with 1 ml of cold H2O, and then centrifugation again at 4000g, cells were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid for >1 hour on ice. Cells were washed twice with 1 ml of acetone, resuspending pellets between washes by bath sonication. Pelleted cells were then lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 8 M urea, 2% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA] by bead beating for 10 min. One-hundred microliters of sample buffer [150 mM tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 8 M urea, 10% SDS, 24% glycerol, 10% (v/v) beta-mercapto ethanol (βME), and bromophenol blue] was then added to the sample and vortexed for 10 min. After centrifugation for 6 min at 21,000g, supernatant was loaded on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Imaging of the Western blots was performed using an Odyssey CLx imaging system and analyzed using the Image Studio Lite 4.0.21 software (LI-COR Biosciences). Fractional degradation of the GFP-tagged proteins was quantified by dividing the intensity of the GFP band from the sum of the intensities of the full-length and the cleaved-GFP bands.

Denaturation IP for ubiquitination assay

Ubiquitination of the CPS constructs was performed in a strain background of doa4∆ pep4∆ prb1∆. CPS constructs were integrated into this strain, and ubiquitin was overexpressed using a myc-Ub construct under the control of a copper promoter. The copper promoter was induced by adding 100 μM CuSO4 for 4 hours to mid-log cells. A 100-OD equivalent of cells was harvested and washed with Milli-Q water. Cells were resuspended in urea-containing buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1% SDS, 8 M urea, 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and 1× Roche protease inhibitor without EDTA]. Cells were lysed with zirconia beads from Biospec (about 500 μl of bead volume) by vortexing twice for 30 s at 4°C. Cells were then chilled on ice for 10 min. An equivalent volume of a high salt–containing buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mM NEM, and 0.2% Triton X-100] was added to the lysate and chilled again on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000g, supernatant was incubated with anti-GFP beads (at a volume ratio of 1:50 beads:solution). This mixture was rotated for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed with wash buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 4 M urea, 20 mM NEM, and 5% glycerol] three times equaling an 8000-fold dilution. Elution was performed by boiling the beads at 98°C for 3 min in 100 μl of sample buffer [150 mM tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 8 M urea, 10% SDS, 24% glycerol, 10% (v/v) βME, and bromophenol blue]. Samples were then blotted for GFP and ubiquitin.

Canavanine assay and Mup1 sorting assay

These assays were performed exactly as described before (21, 34, 35). Briefly, canavanine spot plates were performed on synthetic media with canavanine at various concentrations and imaged after 3 to 5 days. Mup1 sorting assay was performed on Mup1-pHluorin–integrated cells after addition of 20 μg/ml at various time points. Fluorescence measurements were done on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

Formation of lipid monolayers, liposomes, and supported lipid bilayers

Monolayers were formed as previously described (21, 34, 35). Supported lipid bilayers were formed as follows, following previous protocols (13, 36).

To form the supported bilayers, liposomes were first created by extrusion. Lipid mixtures of 2% Ni2+–nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) DOGS (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid)succinyl] (nickel salt) and 98% POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine) were created in chloroform. These lipid mixtures were allowed to evaporate overnight in a desiccator. The dried mixture was hydrated in 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl for about half an hour at room temperature with vortexing every 5 min. These multilamellar vesicles were used to create small unilamellar vesicles by extrusion through a 100-nm extrusion filter (Avanti).

To make supported lipid bilayers, 96-well plate glass-bottomed plates (Cellvis) were used. Plates were cleaned by treating with 5% Hellmanex solution and incubating at 42°C for 30 min. After thorough cleaning with Milli-Q water, the plates were then treated with 6 M NaOH at room temperature for 2 hours. The plates were again thoroughly washed with Milli-Q water. To make supported bilayers, the liposome mixture was warmed to 37°C and then applied to the cleaned glass-bottomed wells. After incubating at room temperature for 10 min, unabsorbed vesicles were washed with bovine serum albumin (BSA) buffer [25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% BSA]. The plates were allowed to sit in this buffer for 30 min. Proteins were then added to this buffer and incubated for various times as indicated in the text for analysis of assembly on the membrane surface. Imaging was performed with either Deltavision widefield or a Leica confocal microscope.

Protein purification

All proteins were expressed in the Rosetta strain. Lysis was performed by sonication on ice. Lysed cells were cleared by centrifugation at 26,000g for 40 min at 4°C. Affinity purification of His-tagged proteins was performed using the Talon cobalt beads.

Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin constructs had an N-terminal His6-SUMO tag, followed by a His6 tag and an N-terminal cysteine for maleimide dye conjugation. 1XUb was expressed with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37°C for 4 hours, and 4XUb was expressed with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18°C overnight. After affinity purification with cobalt beads and cleavage of His6-SUMO on beads, 4XUb was passed through a Hi-Trap S-Sepharose cation exchange column and the flow-through was collected. 1XUb was purified with cobalt beads and H6-Sumo cleaved. Subsequently, these ubiquitin proteins were treated with 1 mM fresh dithiothreitol and then ran though SD200 in buffer lacking reducing agent for labeling. Proteins were concentrated and incubated with Cy3 or Cy5 maleimide (Lumiprobe) at fivefold excess and room temperature to label the proteins. Excess dye was removed by running through a Hi-Trap Q column and dialysis then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Unlabeled proteins were similarly flash frozen right after the SD200 step.

ESCRT-0

Vps27 and Hse1 constructs for expression were made in the pET28a vector containing an N-terminal His6 and SUMO tags and a C-terminal S-tag. Proteins were expressed at 18°C overnight with 1 mM IPTG. After Co2+ column, the SUMO tag was cleaved on beads by the protease Ubl-specific protease 1 overnight at 4°C. The cleaved protein was then applied to an S-column. The flow-through from this step was then concentrated and ran through an SD200 column. A substantial fraction of the Vps27 protein comes out in the void volume, which is not used in the study as the nature of this fraction of protein is not clear, but it is possible that this population also reflects a fraction that is self-assembling. We collect the fraction that enters the column for our studies. Hse1-oregon green and Vps27-oregon green were made using the same labeling protocol as ubiquitin. In this case, the endogenous cysteines on Hse1 were used for labeling purposes. Our experiments contain 10% fluorescently labeled.

For initial experiments, the ESCRT-0 complex was purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae using GAL promoters. In this approach, Hse1 was tagged with GFP at the N terminus, followed by a Prescission cleavage site. GFP-prescission-Hse1 under a GAL promoter was expressed together with Vps27 (also under GAL promoter) in the same vector. This plasmid was integrated into a strain consisting of a Gal4-ER-VP16 system, whose expression can be induced by applying β-estradiol. This strain was grown at 30°C until mid-log and induced with 100 nM β-estradiol until saturation. Cells were collected and lysed using a freezer mill. GFP-prescission-Hse1 was affinity purified using a home-made GFP-nanobody agarose column. The Hse1-Vps27 complex was cleaved off by using Prescission protease on beads at 4°C for ~16 hours. Cleaved protein was concentrated and purified further using an SD200 column (GE Healthcare), in 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. Protein was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. This complex was used for the electron microscopy experiments.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

4XUb-Cy5 and Hse1-Oregon Green fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) were performed on a CSU-X spinning-disk confocal microscopy system (Intelligent Imaging Innovations), coupled to a DMI 6000B microscope (Leica), 100×/1.45-NA objective, and a QuantEMCCD camera. Analysis was performed on Slidebook and ImageJ. Three whole droplets were bleached with either the 647-nm or the 488-nm laser. Fluorescence values of unbleached droplets were taken to correct for photobleaching while imaging.

Electron microscopy

On the monolayer grids, proteins were incubated for 1 hour. Grids were stained with 2% ammonium molybdate. Electron microscopy of the monolayers associating proteins was performed on an FEI Morgagni 268 TEM.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the past and current members of the Emr lab for valuable discussions, Y. Mao for some initial ubiquitin constructs, and J. Baskin, B. White, A. Bretscher, and R. Gringas for imaging resource. S. Banjade was an HHMI fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. This work was also supported by a Cornell University Grant to S.D.E.

Funding: This work was supported by Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fellowship (through HHMI; DRG-2273-16) and Cornell University grant CU3704 to S.D.E.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: S.B. Methodology: S.B., L.Z., J.R.J., and S.W.S. Investigation: S.B. Funding acquisition: S.B. and S.D.E. Supervision: SDE. Writing–original draft: S.B. Writing–review and editing: S.B., S.W.S., and SDE.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The strains and plasmids can be provided by the corresponding authors pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for the strains and plasmids should be submitted to sde26@cornell.edu.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S10

Table S1

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Vietri M., Radulovic M., Stenmark H., The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 25–42 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kostelansky M. S., Schluter C., Tam Y. Y. C., Lee S., Ghirlando R., Beach B., Conibear E., Hurley J. H., Molecular architecture and functional model of the complete yeast ESCRT-I heterotetramer. Cell 129, 485–498 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCullough J., Clippinger A. K., Talledge N., Skowyra M. L., Saunders M. G., Naismith T. V., Colf L. A., Afonine P., Arthur C., Sundquist W. I., Hanson P. I., Frost A., Structure and membrane remodeling activity of ESCRT-III helical polymers. Science 350, 1548–1551 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang S., Henne W. M., Borbat P. P., Buchkovich N. J., Freed J. H., Mao Y., Fromme J. C., Emr S. D., Structural basis for activation, assembly and membrane binding of ESCRT-III Snf7 filaments. eLife 4, e12548 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flower T. G., Takahashi Y., Hudait A., Rose K., Tjahjono N., Pak A. J., Yokom A. L., Liang X., Wang H.-G., Bouamr F., Voth G. A., Hurley J. H., A helical assembly of human ESCRT-I scaffolds reverse-topology membrane scission. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 570–580 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katzmann D. J., Stefan C. J., Babst M., Emr S. D., Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J. Cell Biol. 162, 413–423 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurley J. H., Emr S. D., The ESCRT complexes: Structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 277–298 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollert T., Hurley J. H., Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature 464, 864–869 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayers J. R., Fyfe I., Schuh A. L., Chapman E. R., Edwardson J. M., Audhya A., ESCRT-0 assembles as a heterotetrameric complex on membranes and binds multiple ubiquitinylated cargoes simultaneously. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9636–9645 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel E. B., Audhya A., ESCRT-dependent cargo sorting at multivesicular endosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 74, 4–10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adell M. A. Y., Migliano S. M., Upadhyayula S., Bykov Y. S., Sprenger S., Pakdel M., Vogel G. F., Jih G., Skillern W., Behrouzi R., Babst M., Schmidt O., Hess M. W., Briggs J. A., Kirchhausen T., Teis D., Recruitment dynamics of ESCRT-III and Vps4 to endosomes and implications for reverse membrane budding. eLife 6, e31652 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald C., Payne J. A., Aboian M., Smith W., Katzmann D. J., Piper R. C., A family of tetraspans organizes cargo for sorting into multivesicular bodies. Dev. Cell 33, 328–342 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banjade S., Rosen M. K., Phase transitions of multivalent proteins can promote clustering of membrane receptors. eLife 3, e04123 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banani S. F., Lee H. O., Hyman A. A., Rosen M. K., Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 285–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li P., Banjade S., Cheng H.-C., Kim S., Chen B., Guo L., Llaguno M., Hollingsworth J. V., King D. S., Banani S. F., Russo P. S., Jiang Q.-X., Nixon B. T., Rosen M. K., Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 483, 336–340 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L., Jorgensen J. R., Li M., Chuang Y.-S., Emr S. D., ESCRTs function directly on the lysosome membrane to downregulate ubiquitinated lysosomal membrane proteins. eLife 6, e26403 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odorizzi G., Babst M., Emr S. D., Fab1p PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase function essential for protein sorting in the multivesicular body. Cell 95, 847–858 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katzmann D. J., Babst M., Emr S. D., Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 106, 145–155 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Zhang W., Wen X., Bulinski P. J., Chomchai D. A., Arines F. M., Liu Y.-Y., Sprenger S., Teis D., Klionsky D. J., Li M., TORC1 regulates vacuole membrane composition through ubiquitin- and ESCRT-dependent microautophagy. J. Cell Biol. 219, e201902127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M., Rong Y., Chuang Y.-S., Peng D., Emr S. D., Ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal membrane protein sorting and degradation. Mol. Cell 57, 467–478 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banjade S., Tang S., Emr S. D., Genetic and biochemical analyses of yeast ESCRT. Methods Mol. Biol. 1998, 105–116 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzmann T. M., Jahnel M., Pozniakovsky A., Mahamid J., Holehouse A. S., Nüske E., Richter D., Baumeister W., Grill S. W., Pappu R. V., Hyman A. A., Alberti S., Phase separation of a yeast prion protein promotes cellular fitness. Science 359, eaao5654 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banjade S., Shah Y. H., Tang S., Emr S. D., Design principles of the ESCRT-III Vps24-Vps2 module. eLife 10, e67709 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teis D., Saksena S., Judson B. L., Emr S. D., ESCRT-II coordinates the assembly of ESCRT-III filaments for cargo sorting and multivesicular body vesicle formation. EMBO J. 29, 871–883 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parrish W. R., Stefan C. J., Emr S. D., Essential role for the myotubularin-related phosphatase Ymr1p and the synaptojanin-like phosphatases Sjl2p and Sjl3p in regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3567–3579 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Votteler J., Ogohara C., Yi S., Hsia Y., Nattermann U., Belnap D. M., King N. P., Sundquist W. I., Designed proteins induce the formation of nanocage-containing extracellular vesicles. Nature 540, 292–295 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case L. B., Zhang X., Ditlev J. A., Rosen M. K., Stoichiometry controls activity of phase-separated clusters of actin signaling proteins. Science 363, 1093–1097 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stringer D. K., Piper R. C., A single ubiquitin is sufficient for cargo protein entry into MVBs in the absence of ESCRT ubiquitination. J. Cell Biol. 192, 229–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson L.-A., Briggs J. A. G., Glass B., Riches J. D., Simon M. N., Johnson M. C., Müller B., Grünewald K., Kräusslich H.-G., Three-dimensional analysis of budding sites and released virus suggests a revised model for HIV-1 morphogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 4, 592–599 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snead W. T., Gladfelter A. S., The control centers of biomolecular phase separation: How membrane surfaces, PTMs, and active processes regulate condensation. Mol. Cell 76, 295–305 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Appen A., LaJoie D., Johnson I. E., Trnka M. J., Pick S. M., Burlingame A. L., Ullman K. S., Frost A., LEM2 phase separation promotes ESCRT-mediated nuclear envelope reformation. Nature 582, 115–118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan F., Alimohamadi H., Bakka B., Trementozzi A. N., Day K. J., Fawzi N. L., Rangamani P., Stachowiak J. C., Membrane bending by protein phase separation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2017435118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIsaac R. S., Silverman S. J., McClean M. N., Gibney P. A., Macinskas J., Hickman M. J., Petti A. A., Botstein D., Fast-acting and nearly gratuitous induction of gene expression and protein depletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4447–4459 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banjade S., Tang S., Shah Y. H., Emr S. D., Electrostatic lateral interactions drive ESCRT-III heteropolymer assembly. eLife 8, e46207 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henne W. M., Buchkovich N. J., Zhao Y., Emr S. D., The endosomal sorting complex ESCRT-II mediates the assembly and architecture of ESCRT-III helices. Cell 151, 356–371 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su X., Ditlev J. A., Rosen M. K., Vale R. D., Reconstitution of TCR signaling using supported lipid bilayers. Methods Mol. Biol. 1584, 65–76 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S10

Table S1

Movies S1 to S3