Abstract

Conflict between parents is stressful and disruptive to children living in the midst of parental separation or divorce. Although some level of post-separation/divorce conflict is understandable in an emotionally-charged separation/divorce, it undermines the extent to which parents protect their children from short- and long-term problems. In this article, we weave together a synthesized perspective informed by our respective training and experience in prevention science and family law on the role of parent education programs for high-conflict separating/divorcing parents. To do so, we first describe the research on the effects of high interparental conflict on children’s outcomes and then discuss current approaches and challenges to reducing these negative effects by offering parent education programs for high-conflict separating/divorcing parents. Then, we propose and describe a new model for early, effective, and scalable parent education programs with the ultimate goal of protecting children after separation/divorce.

“The only childhood stress greater than having two married parents who fight all the time is having two divorced parents who fight all the time.”

Conflict between parents is stressful and disruptive to children living in the midst of parental separation or divorce. In some families, the conflict becomes an embedded pattern of behavior that has long-term negative implications for children. The conflict not only gives rise to an unhealthy environment for the children, it often results in recurrent family court litigation. When the revolving door of litigation becomes evident, these parents and their cases are often labeled as “frequent fliers” in family courts (Kreeger, 2008; Sullivan & Burns, 2020). Some parents experience systemic vilification based on stereotypes perpetuated by client-facing blog posts (e.g., Buie, 2022; Farias Family Law, P.C., n.d.; Stich, 2014) and popular press books (e.g., Behrman & Zimmerman, 2018; Eddy, 2020; Warshak, 2010). Illustratively, a parent recently penned an op-ed in the Boston Globe (Elton, 2020) asserting that mandatory parent education can be a shaming experience for parents and citing research by legal and feminists scholars who have described similar experiences (Charania & Simonds, 2018; Schaefer, 2010). Anecdotally, parents describe a wide range of reactions from legal professionals involved in their cases. Examples include having their struggles with their co-parent dismissed as two people who “just cannot get along,” receiving remarks about whether their love for their children pales in comparison to their commitment to the conflict, being accused of having low empathy, and being labeled with mental health or personality disorders. Although these characterizations may be accurate in certain cases, a large portion of this group is fully committed to their children and does not suffer from a diagnosable mental health condition (Mandarino et al., 2016; Smyth & Moloney, 2019). Instead, they have become enmeshed in a pattern of conflict behavior that, at its core, is an extension of the dysfunction that led to the break-up of the relationship.

Parental conflict is predictable in an emotionally-charged separation/divorce, but it often undermines parents’ goal of protecting their children from short- and long-term problems. Although high-conflict cases represent a small minority of all separating/divorcing parents (estimates range from 5–10%; Neff & Cooper, 2004; Schepard, 2004), these cases threaten children’s well-being and consume a disproportionate amount of court resources. From a public health and court resource perspective, these percentages translate into between 250,000 and 500,000 families each year based on the latest statistics from the National Center for State Courts that indicate nearly five million domestic relations cases are filed annually (Court Statistics Project, 2020). Thus, improving programs for high-conflict separated/divorcing parents is a critical step toward reducing the public health burden and community costs of parental separation/divorce. Prevention scientists and family court professionals share the goal of protecting and promoting the well-being of children whose parents are separating or divorcing and thus, effectively reducing interparental conflict among separating/divorcing parents is a shared priority of these disciplines.

In this article, we synthesize our perspectives as a prevention scientist (K. O’Hara) and a family court presiding judge (B. Cohen) on the role of parent education programs for high-conflict separating/divorcing parents. We advocate for early, effective, and scalable parent education programs designed specifically for high-conflict parents. These ideas were developed in the context of a larger project that includes team members from Arizona State University (Sharlene Wolchik, Irwin Sandler, Cady Berkel, Michele Porter), the National Center for State Courts (Alicia Davis) and Maricopa County Superior Court (Shawn Friend).

The following sections discuss the research on the effects of high interparental conflict on children’s outcomes and alternative approaches of brief and targeted parent education programs to reduce interparental conflict after separation/divorce. We highlight how existing programs often focus on challenging the parents’ feelings toward one another, instead of focusing on how specific behaviors can positively or negatively impact children. We underscore the importance of rigorous evaluation to ensure that programs meet their goal of protecting children from interparental conflict. We argue that without evidence that programs exert positive effects on children, implementing them in family court is likely to be ineffective and a drain on limited resources. We then propose a scalable model of high-conflict parent education that has the ultimate goal of protecting and promoting children’s mental health and well-being. Throughout, we weave together perspectives from prevention science and family law on the best way to promote the successful transition of families through the separation/divorce process while protecting children from the deleterious effects of exposure to interparental conflict.

What do we know about high-conflict divorce/separation?

Interparental conflict is harmful to children’s health and well-being

Decades of research have shown that exposure to conflict predicts poor outcomes for children across family structures (Harold & Sellers, 2018), socioeconomic status (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; El-Sheikh et al., 2008), and cultural and geographic lines (Bradford et al., 2003). Conversely, there is some evidence that the quality of co-parenting or co-parent cooperation (i.e., respect, communication, trust, valuing, agreement, and low conflict) after divorce predicts children’s post-divorce adjustment (Lamela & Figueiredo, 2016). Although cooperation and conflict dimensions of co-parenting quality are strongly correlated (e.g., r = .64; Saini et al., 2019; r = .78 - .83; Saini et al., 2022), they are not mutually exclusive. However, there are very few studies that have examined the unique effects of co-parenting dimensions, making it difficult to parse out how different patterns of conflict and cooperation contribute to children’s outcomes. Future studies will need to assess the unique effects of cooperative vs. conflictual co-parenting on children’s post-separation/divorce adjustment to better inform intervention strategies.

Although exposure to interparental conflict is a general risk factor, it is particularly salient for children from separated/divorced families. Exposure to frequent, intense, and persistent conflict between separating/divorcing parents is the most well-documented risk factor for children’s mental health and well-being following parental separation/divorce (Amato, 1993, 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991). Although after divorce most children return to pre-separation/divorce functioning within two years (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002), exposure to ongoing conflict can interrupt the adjustment process and confer risks for the development of long-lasting problems in multiple domains of a child’s life. These problems include physical (Fabricius & Luecken, 2007) and mental health problems (Elam et al., 2019; O’Hara et al., 2019), risky health behaviors, (O’Hara et al., 2019; Orgilés et al., 2015), low self-esteem (Noller et al., 2008), difficulties in social functioning (Forehand et al., 1994; Vandewater & Lansford, 1998), and academic underachievement (Long et al., 1988).

Chronic, frequent, and intense interparental conflict is especially harmful to children

Some degree of interparental conflict is common in the context of parental separation/divorce, which is not surprising given that many important decisions must be made when parents separate, and family life must be reorganized. Interparental conflict that is unrelated to the children, is expressed without animosity, and is successfully resolved is not particularly harmful to children. In some cases, it can even provide socialization to adaptive conflict resolution skills (Harold & Murch, 2005; Warmuth et al., 2019). However, conflict that endures with high frequency and intensity has deleterious effects on children’s post-separation/divorce adjustment (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Johnston et al., 2012). The most deleterious effects occur in child-centered conflict and unresolved conflict (Johnston, 1994). In particular, the degree to which parents express negative and hostile emotional tones and behaviors influences how the child experiences and makes sense of the conflict (Cummings & Wilson, 1999).

Scholars have described distinct types of conflict, the two most common being overt conflict (e.g., yelling, arguing) and covert conflict (e.g., triangulating the child into the conflict, denigrating or undermining the other parent) (Bradford & Barber, 2005). Overt conflict is often more obvious and intuitive to identify, as it is characterized by verbal and behavioral displays of disagreement and hostility between parents. Covert conflict is characterized by coercive behaviors that result in parent-child boundary violations and parental psychological control (Bradford & Barber, 2005). Illustratively, parents coerce children into conflict in passive-aggressive ways such as asking them to take sides or deliver or collect information while with the other parent and badmouthing or scapegoating the other parent. Although covert conflict has been less extensively studied, it is clear from research and clinical accounts that it can be just as, or even more, damaging to a child as exposure to overt conflict (Bradford et al., 2008; Bradford & Barber, 2005; Rowen & Emery, 2018). One group of researchers found that both covert and overt conflict was associated at a similar magnitude with children’s mental health problems (Buehler et al., 1998). However, covert conflict has been uniquely associated with children’s internalizing problems (i.e., depression, and anxiety) whereas overt conflict has been uniquely associated with children’s externalizing problems (Buehler et al., 1998; Buehler & Welsh, 2009).

For most families, interparental conflict declines as a function of time as agreements are reached and decisions are made about parenting time and decision-making. Often, parents adjust emotionally to their new family life. However, high levels of conflict continue, sometimes for many years, for a sizeable subgroup (estimates range from 15–39%; Fischer et al., 2005; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; O’Hara et al., 2019; Sbarra & Emery, 2005) of divorcing parents. Research shows that children do not become desensitized the longer they are exposed to interparental conflict. Rather, they become even more sensitive and reactive to conflict the more they experience it (Davies et al., 2006; Erath & Bierman, 2006; Goeke-Morey et al., 2013).

Interparental conflict is challenging and understandable

For most parents, involvement in family court is an adversarial process at its core. Parents are situated as opponents from the first filing to the final settlement, contested trial, or beyond. Despite the shift over the last several decades to a system that emphasizes a more collaborative approach (e.g., alternative dispute resolution; see Jacob, 1988; Lande, 2011; Singer, 2009; Teitelbaum & DuPaix, 1987), there is often a misplaced emphasis on being perceived as the winner or loser in the divorce or family-related proceedings. Thus, it is not surprising that interparental conflict as well as the strong emotions of anger and fear are a normative part of separation/divorce for many parents. Although emotions and beliefs surrounding divorce or contested proceedings are not legally relevant in the era of no-fault divorce, they do impact behavior and thus must not be discarded as extraneous.

What are the current approaches and challenges to parent education programs for high-conflict parents?

Parent education programs for separated/divorcing parents emerged in the late 1970s and proliferated in the 1990s (Salem et al., 2013). The most recent published survey of parent education programs in the United States shows that 46 states currently have mandated parent education provided by the family court (Mayhew, 2016). In Australia, Family Relationships Centres established in 2006 provide group information sessions for parents prior to entering mandatory mediation services (Parkinson, 2013). In Canada, all provinces and territories offer parent education in some form (McKenzie & Bacon, 2009), although mandated programs are implemented in only some places (e.g., Alberta; Family Law Practice Note: Parenting after Separation, 2015). In Denmark, a new law enacted in 2019 requires all parents seeking a separation/divorce to enroll in an online course (Hald et al., 2020). These parent education programs typically provide a general overview of the effects of divorce or separation on children and include a basic segment on the impact of conflict on children. Many jurisdictions offer a separate program for cases that have been identified to have high levels of conflict. These programs involve later intervention (i.e., after a period demonstrating ongoing conflict behaviors or serial litigation revolving around parenting issues), and a variety of approaches are utilized. Primarily, they are categorized by the extent to which they are either educational/didactic or skill-building focused.

Educational/didactic.

The vast majority of court-based programs for separating/divorcing parents, including those with high levels of conflict, are didactic. Some are group-based, and others are internet-delivered. Most didactic programs use lectures, videos, and written materials to convey information about topics, such as the effects of divorce on adults and children, family court procedures, community resources, benefits of parental cooperation, and common responses children at different developmental stages have to divorce (Braver et al., 1996; Schramm et al., 2018; Schramm & Becher, 2020). The effects of interparental conflict on children is one of the most commonly covered topics (Braver et al., 1996). The theory underlying didactic parent education is that information about the damaging effects of conflict will change parent conflict behaviors indirectly by motivating parents to stop engaging in conflict to protect their children. Although these programs are rated as highly acceptable by parents (e.g., Neff & Cooper, 2004), there have been but a few rigorous evaluations of whether they reduce children’s exposure to conflict between their parents, decrease legal conflict, or reduce children’s mental health problems (Fackrell et al., 2011; Salem et al., 2013; Sigal et al., 2011). There exist many barriers to systematic evaluation of programs in community settings, including adequate training in program evaluation, funding, and access to appropriate assessment tools. Notably, there is an ongoing recent initiative to develop a standardized divorce education evaluation tool as an initial step toward understanding the effects of programs across jurisdictions (Markham et al., 2021).

Skill-based programs.

There are also parenting programs for separating/divorcing families that focus on building and practicing parenting and conflict resolution skills (Cookston et al., 2007; Forgatch & Degarmo, 1999; Wolchik et al., 2009). In contrast to the didactic programs which are typically 1–2 sessions, skill-building programs are typically 8–12 sessions. These programs have been rigorously evaluated in randomized controlled trials and shown to have positive, lasting effects on their target outcomes, including positive parenting behaviors, reductions in interparental conflict, and child mental health problems (see recent review by Sandler et al., 2022).

Prominent challenges.

There have been significant challenges in getting effective programs for high-conflict parents into court systems for three main reasons. First, despite the proliferation of parent education programs, effective programs for high-conflict parents are expensive and time-consuming. That fact alone renders these programs unavailable to a large segment of this population. Second, court-ordered engagement in many of these programs is often implemented long after conflict behavior has become a regular part of the parents’ interactions, sometimes including an extended period of serial litigation and unresolved conflicts, and children have already suffered significant exposure. Third, in meeting its mandate to develop a parenting plan that is in the child’s best interests, the family court must be mindful of the time and autonomy infringement on parents. The latter is critical because of the dilemma integral to court-ordered parenting programs. Although the child’s best interests are always central to parenting-related decisions, courts must balance this principle with the fact that parents have a fundamental right to raise their children as they deem fit (Troxel v Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000). The interests in protecting children while also respecting parental autonomy are often at odds. Further, recent cases have tested the scope of ongoing authority of the court in mandating services, such as therapy, to improve the parenting climate for children.1

Key features of a new model for high-conflict parent education programs

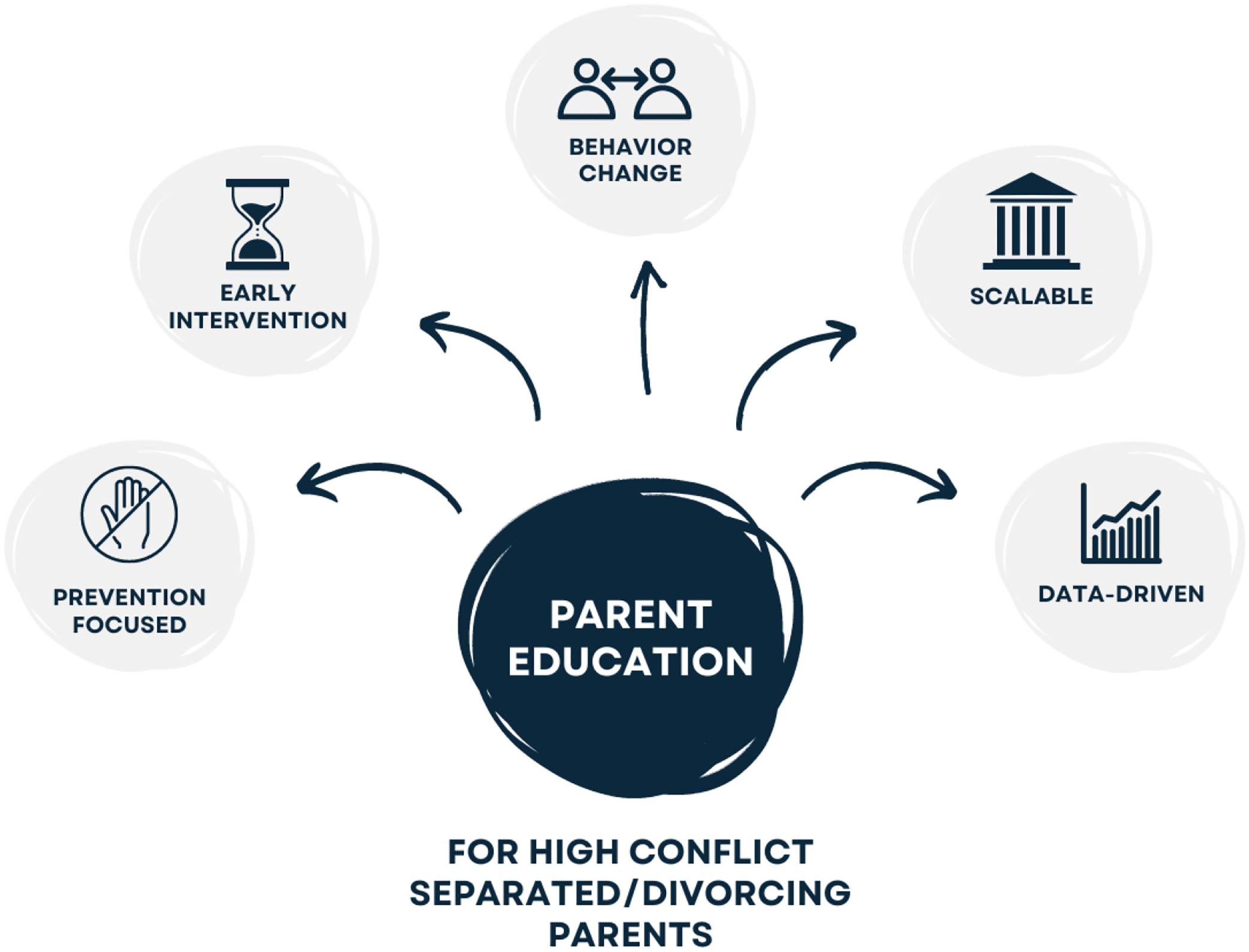

In the following sections, we describe key features of a new model for intervening with parents who have demonstrated high levels of conflict during and after separation/divorce or contested parenting-related litigation. In particular, this new model highlights the importance of a preventive program that is offered early in the separation/divorce process, focused on behavior change, and scalable to be widely implemented in family courts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Key features of a new model for high-conflict parent education programs.

Prevention-focused

Separating and divorcing parents are fundamentally families in transition. Fundamental principles of prevention science, including reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors, targeting individuals at higher levels of risk, and intervening early whenever possible (Harachi, 2002), and behavior change theoretical models (e.g., theory of planned behavior, Ajzen, 1991; psychological flexibility, Hayes, 2019) highlight key directions for intervening with high-IPC separating/divorcing parents. The focus of prevention-focused programs should be to guide high-IPC parents through this transition in a way that protects and promotes the well-being of their children as they navigate changes in their families. Programs must help parents develop a new vision for their family and outline their aspirations for moving forward to their new family situation. This likely involves helping parents identify what is important to them and to develop an intentional, result-based approach as to how to engage the other parent in ways that are consistent with their long-term goals for the children. Focusing on what is important to them can lead to a shift in their attitude towards conflict with their child’s other parent. We contend that the messaging must be forward-thinking to help parents appreciate their situation as a transition that involves change-induced stress and provides an opportunity to reconfigure their family life in ways that are important to them. Providing examples of how other parents in similar situations have found success, and reinforcing a message that small changes lead to important results will increase parents’ perceived behavioral control. As an example, programs could help parents understand that the steps they take to protect their children from conflict in day-to-day life are a worthwhile investment that will yield a return on their investment in the form of high-quality relationships for decades to come.

It is also important to stress that multiple changes or transitions in families over time are common. Although in some cases, the court’s involvement may have a clear beginning (e.g., filing a petition), middle (e.g., motions, status conferences, trials), and end (e.g., settlement conference, judicial hearing), many families require modifications to their parenting plans over time. Thus, an important goal is to navigate modifications as needed in a fashion that focuses on long-term goals rather than be seen as a continued battle with the other parent.

Offered early in the separation/divorce process

A critical question for courts interested in protecting children from the adverse effects of post-separation/divorce is – at what level and for what duration of conflict is conflict benign? How soon must courts intervene with high-conflict parents2 to have a protective effect on children? A precise answer to that question is not available. However, a recent study found that children exposed to high interparental conflict in the first few years after the divorce, regardless of whether the conflict diminished or increased over the next six years, were more than twice as likely to have diagnosable levels of mental disorder in adolescence as compared with those who have been exposed to relatively low (i.e., but not zero) levels of parental conflict over time since the divorce (O’Hara et al., 2019). To our knowledge, this is the only study that assessed how trajectories of conflict over time relate to children’s mental health problems after parental separation/divorce. These data make a strong argument for early intervention to reduce the long-term negative effects of post-separation/divorce interparental conflict. Although waiting to intervene after a long-term history of conflicted litigation is established may be seen as more efficient since conflict reduces as a function of time for many families, this method is not an effective way of protecting the children who are then subjected to prolonged exposure to conflict. Even in cases where the conflict dissipates over time, the damage may already be done. If feasible, early screening to identify families experiencing high levels of conflict before or during the separation/divorce process would be an effective strategy. In the absence of a systematic screening procedure, families should be referred to intervention as early as they are identified.

Focused on behavior change

Effective programs often have multiple elements that contribute to positive change in behavior. In our proposed model, the first element focuses on emotion regulation and emotion validation as a pathway to behavior change. Empirical findings, theoretical models, and clinical descriptions of high-conflict parents indicate that a primary barrier to reducing interparental conflict behaviors is trouble regulating complex and intense emotions (Low et al., 2019; Snyder et al., 2006). One study found that high levels of anger predicted less problem-solving and reduced the likelihood of reaching an agreement in divorce mediation (Bickerdike & Littlefield, 2000). In another study validating a measure of co-parenting difficulties, the item “I feel out of control when I am speaking to the other parent” predicted over 80% of the variation in the level of animosity (Saini et al., 2019).

Drawing from the vast body of evidence on emotion-driven behaviors, we highlight the usefulness of validation to reduce the emotional temperature of a situation to facilitate a parent’s ability to implement behavioral skills, such as resolving the conflict or shielding their children from the conflict. The ability to regulate emotion facilitates one’s ability to navigate emotionally charged situations while maintaining goal-directed behavior, such as protecting children from interparental conflict. Research shows that validation soothes intense emotions that are otherwise likely to impede the successful enactment of protective parenting skills (Maliken & Katz, 2013; Zalewski et al., 2018). Emotion validation strategies encourage parents to accept that strong emotions are understandable given the context and allow strong emotions to be present without them preventing taking actions that accord with their goals and values for parenting.

Reducing interparental conflict, without necessarily changing a parent’s feelings toward the other parent, is most likely to occur in the context of a program that recognizes and validates the strong emotions that often arise for parents navigating a high-conflict separation or divorce. The basic idea is that deeply-felt feelings of anger and fear are understandable and should be validated instead of exacerbated or dismissed. This stands in stark contrast to ineffective behavior change strategies, which may include explicit or implicit messages of invalidation (e.g., “just calm down”), changing how one feels (e.g., “you should not feel that way”), assignment of blame (“who is right?”). These strategies are sometimes used inadvertently as strong emotions are often treated as nefarious in the family court setting, without recognizing that intense emotional reactions during the divorce or contested parenting litigation process are natural. Thus, incorporating effective emotion regulation strategies into programs for high-conflict parents is particularly important. The specific strategies could be drawn from existing evidence-based programs and psychosocial research, and tailored to meet the needs of high-conflict parents.

Two other elements involve helping parents understand why changing their behavior to reduce interparental conflict matters. One element will provide psychoeducation about the impact of conflict on children. We expect that most parents understand, in general, abstract terms that exposure to conflict is harmful to children. However, providing them with scientific information about the long-lasting effects of interparental conflict on children’s mental and physical health, combined with powerful anecdotes, is a crucial element in reducing conflict behaviors. The other element will leverage motivational interviewing strategies to assist parents in identifying values and goals for their family and developing a new vision for their family moving forward.

The last element focuses on behavior change. It may seem unlikely to some that true behavior change can be accomplished by way of court-based interventions, which are very often limited in time and scope. However, there are numerous examples from psychological science that demonstrate behavior change is possible in the context of brief, even single-session, interventions (Schleider & Weisz, 2017). The theory underlying this approach to behavior change is referred to as “wise interventions” where precise and targeted strategies are used to intervene on psychological processes that maintain undesired behavior (Schleider et al., 2020; Walton, 2014; Walton & Wilson, 2018). Psychological processes to be targeted include shifting intentions, skill-building, and changing perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes. For example, researchers trained parents to articulate an explanation for their child’s behavior problems that was neither self- nor child-blaming. It led to a measurable increase in parent empowerment and decreased child health problems and rates of child abuse (Bugental et al., 2002; Bugental & Schwartz, 2009). Another example, from the marital conflict literature, demonstrated that adopting a third-party perspective when describing conflicts interrupted predicted declines in marital satisfaction over time (Finkel et al., 2013).

Court-based interventions focused on behavior change, like all “wise interventions,” rest on the underlying assumption that the intervention strategies will change an intermediary psychological process such as parents’ intentions and beliefs, or their knowledge and perceived efficacy in using conflict resolution skills. In turn, shifts in these psychological processes are expected to facilitate behavior change that ultimately results in reduced exposure to interparental conflict for the child. Thus, the ultimate outcomes of these interventions are often not observable until well after the intervention is over.

Our team is considering two approaches to inducing a change in conflict behavior. The first approach reflects a triage model, where the participating parents are provided with metaphors and imagery to show parents a new way of approaching their conflict. It is believed that the combination of validation, motivation, and anecdotes that model an effective internal mindset in dealing with the other parent can inspire behavior change.

A second approach focuses on skill-building. In this approach, parents will learn concrete behaviors to regulate strong emotions and shield their children from conflict and then practice and problem-solve difficulties using these skills. Prior research demonstrates that the at-home practice of new skills is the active ingredient underlying behavior change across intervention programs (Berkel et al., 2016; Ory et al., 2002). This approach will teach skills to decrease children’s exposure to interparental conflict (e.g., scheduling discussions when children are not present, asking others to refrain from speaking negatively about the other parent, talking to trusted adults about problems with the other parent), and de-escalation strategies to use when conflicts occur (e.g., anger management, managing nonverbal communication).

Scalable

Effective programs must be scalable (i.e., accessible, affordable, and deliverable) to impact public health. Estimates suggest that it takes almost two decades for effective programs to make their way into everyday service delivery systems (Estabrooks et al., 2018). In the last several years, there have been multiple advances in the field of implementation science that we can turn to for lessons on improving the scalability of new programs (Rudd & Beidas, 2021). Illustratively, these lessons include the importance of incorporating the perspectives of stakeholders (i.e., decision-makers about program adoption as well as eventual users of the program) (Lyon & Koerner, 2016), testing various delivery methods (Kazdin, 2017), and selecting effective implementation strategies (Powell et al., 2015). In developing effective programs for high-conflict parents, it is critical that they that can be used as part of the regular court service delivery system and effectively engage parents to use the information they learn in their daily lives. If courts decide to incorporate a preventive approach, imposing a court-ordered intervention would be done much earlier in the divorce process and would result in a far larger number of parents being referred. This highlights the need for any early intervention program to be scalable.

We considered several elements that are involved in designing a program that can be delivered at a large scale to all separating/divorcing parents who may benefit. The first element is making the program affordable. Prior research with key informants from 154 courts indicates that courts are interested in offering evidence-based services for separated/divorcing families, but the number one cited barrier (endorsed by 71% of counties represented) was access to funding (Cookston et al., 2002). Given this, we expect that the parent education element will need to be digitally delivered either in whole or in part. The second element is making the program sustainable. Sustainable court programs align with existing family court services workflow and legal requirements. Given that these programs are likely to be court-ordered or mandated in many jurisdictions, there must also be a system to track parents’ engagement. The third element is making the program contextually appropriate. Parents are unlikely to fully engage in a program if they do not feel it was designed to understand their experience. In a study of high-conflict parents’ experience with court-affiliated programs, a sizeable group of parents reported feeling unheard or not validated (Mandarino et al., 2016). Regardless of the intended audience, effective programs are designed to fit the needs of those they intend to benefit. In the case of high-conflict separated/divorcing parents, special attention must be paid to capturing the range of complex family structures that are seen in family court, including never-married parents, same-sex parents, stepfamilies, multi-generation families, and families with orders regarding grandparent visitation. Contextually appropriate programs also incorporate tailored design elements, such as relatable content and engagement strategies that fit with the wide range of experiences high-conflict parents have. In addition to leveraging best practices in digital program engagement, conducting mixed methods research aimed to gather critical information from parents themselves, as well as court service providers who work with high-conflict parents, can further our understanding of how to best engage and motivate high-conflict parents to change their behaviors and reduce interparental conflict. In particular, human-centered design research principles provide a framework to incorporate the voices of stakeholders throughout the program development and evaluation process (Lyon & Bruns, 2019; O’Hara et al., 2022).

Data demonstrating effectiveness

Programs for high-conflict families must be rigorously evaluated to truly understand their effects (Gottfredson et al., 2015). From a prevention science perspective, programs that do not demonstrate measurable change in key outcomes are a waste of time and resources. Thus, we must know whether the offered programs meet their intended objectives. Offering only programs with evidence of effectiveness will ensure that resources are allocated to promote the mission of the family court while also conserving court and parent resources.

Rigorous evaluation of programs involves two aspects of scientific standards of evidence. One aspect is a control group. The gold standard evaluation model is a randomized controlled trial where parents are randomly assigned to the program or control group. Quasi-experimental trials use a nonrandomized control group (e.g., an equivalent or historical control), and although this design is less rigorous than an RCT, it provides more reliable information about program effects than evaluations with no control group (e.g., pre/post measures). Although studies without a control may provide some insight about whether participation in an intervention is associated with change, possible third variable explanations undermine conclusions about whether the effects observed are truly due to the program, or to something else. This is particularly critical regarding conclusions about intervention-induced changes in IPC as it is well-documented that for many families, IPC decreases as a function of time (e.g., Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; O’Hara et al., 2019). The second aspect of rigorous evaluation involves thinking carefully about which outcomes to measure, when to measure them, and how to measure them. Measures such as parent satisfaction or intention to change behaviors may provide important information about how parents experience the program. However, they do not answer the question of whether the program is effective in protecting children from interparental conflict. If an objective is to protect children from the adverse outcomes of exposure to conflict, the evaluators must include measures of both conflict and children’s outcomes (e.g., mental health and behavior problems) before and after the program. Long-term follow-up evaluations should be considered to the extent they are feasible. Finally, data collected from multiple reporters offers several advantages, including access to different information (e.g., children’s observable behavior versus their internal experiences), increased reliability of key information (e.g., child’s perception of conflict versus parent’s report), and more robust effect size estimates (e.g., reduced impact of statistical bias that occurs when the same person provides all the data).

Developing and evaluating an early, effective, and scalable model for high-conflict parent education programs

We are in the process of developing and evaluating a parent education model for high-conflict separating/divorcing parents that is: (1) a preventive service; (2) offered early in the separation/divorce process; (3) that is focused explicitly on behavioral strategies parents can use to reduce conflict; and (4) is affordable and efficient as possible so that it can be easily implemented as a regular family court service. Our program development and evaluation plan includes (1) experimentally testing two approaches to behavior change (i.e., a triage model, where the participating parents are provided with metaphor and imagery to show parents a new way of approaching their conflict, versus a skill-building model, where parents are taught explicit behavioral skills and supported in implementing those skills over time), (2) working with key stakeholders and end-users (e.g., court administrators, judges, mental health professionals, separating/divorced parents) to incorporate their needs and preferences for program content and delivery throughout the program development process, and (3) conducting randomized trials to evaluate program effects on parents’ conflict behaviors and children’s mental health problems. Ultimately, we intend to offer the program in several modalities to support wide-scale use. Our goal is to ensure that high-conflict parents across jurisdictions have access to a program that helps them reduce their conflict and protect their children’s well-being.

Conclusion

There is compelling evidence that children exposed to high levels of post-divorce interparental conflict are more likely to develop mental health problems even if the conflict decreases over time. Thus, we maintain that parent education programs for high-conflict separating/divorcing parents must be offered early in the separation/divorce process. We also argue that to reduce the public health burden and community costs of parental separation/divorce, programs need to be demonstrably effective in reducing conflict and protecting children’s mental health, inexpensive and easy-to-access, and designed to target concrete and achievable goals within the family courts’ time and resource constraints.

Acknowledgments

Karey L. O’Hara’s work on this paper was supported by a career development award provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH120321). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor does it reflect the policies of the Maricopa County Superior Court. The authors would like to thank Sharlene Wolchik for her comments on a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

An example is Paul E. v Courtney F., 246 Ariz. 388 (2019).

The term “high-conflict divorce” is a label that describes a heterogenous group. Some divorces are characterized by high levels of legal conflict, including disputes over parenting time allocations, child support, and legal decision-making power. Others are characterized by frequent and intense interpersonal conflict, such as arguing and fighting, badmouthing one another, and putting their children in the middle, which spurs loyalty conflicts and alliances. Legal conflict and interpersonal conflict are correlated (r = .39; Goodman et al., 2004); parents identified by the court as “high-conflict” may engage in one or both types of conflict. Despite the vast literature on the effects of interpersonal conflict on children’s outcomes, there is a dearth of research on how legal conflict impacts children.

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (1993). Children’s adjustment to divorce: Theories, hypotheses, and empirical support. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55(1), 23–38. 10.2307/352954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(3), 355–370. 10.1037/0893-3200.15.3.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Keith B (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 26–46. 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman L, & Zimmerman J (2018). Loving Your Children More Than You Hate Each Other: Powerful Tools for Navigating a High-Conflict Divorce (1st edition). New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, Mauricio AM, & Jones S (2016). “Home practice is the program”: Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-016-0738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerdike AJ, & Littlefield L (2000). Divorce adjustment and mediation: Theoretically grounded process research. Mediation Quarterly, 18(2), 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K, & Barber BK (2005). Interparental conflict as intrusive family process. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 5(2/3), 143–167. 10.1300/J135v05n02_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K, Barber BK, Olsen JA, Maughan SL, Erickson LD, Ward D, & Stolz HE (2003). A Multi-National Study of Interparental Conflict, Parenting, and Adolescent Functioning: South Africa, Bangladesh, China, India, Bosnia, Germany, Palestine, Colombia, and theUnited States. Marriage & Family Review, 35(3–4), 107–137. 10.1300/J002v35n03_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K, Vaughn LB, & Barber BK (2008). When there is conflict: Interparental conflict, parent–child conflict, and youth problem behaviors. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 780–805. 10.1177/0192513X07308043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL, Salem P, Pearson J, & DeLusé SR (1996). The content of divorce education programs: Results of a survey. Family Court Review, 34(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, & Gerard JM (2002). Marital Conflict, Ineffective Parenting, and Children’s and Adolescents’ Maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(1), 78–92. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00078.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Anthony C, Pemberton S, Gerard J, & Barber BK (1998). Interparental Conflict Styles and Youth Problem Behaviors: A Two-Sample Replication Study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(1), 119–132. 10.2307/353446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, & Welsh DP (2009). A process model of adolescents’ triangulation into parents’ marital conflict: The role of emotional reactivity. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(2), 167–180. 10.1037/a0014976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, & O’Hara N (2002). A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 243–258. 10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, & Schwartz A (2009). A cognitive approach to child mistreatment prevention among medically at-risk infants. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 284–288. 10.1037/a0014031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buie E (2022, January 27). 4 Ways to Demonstrate That You Love Your Kids More Than You Hate Your Ex Elise Buie Family Law. Elise Buie Family Law. https://elisebuiefamilylaw.com/4-ways-to-demonstrate-that-you-love-your-kids-more-than-you-hate-your-ex/ [Google Scholar]

- Charania M, & Simonds W (2018). Governing the Divorcée: Gender and Sexuality in State-Mandated Parenting Classes. Feminist Studies, 44(3), 600–631. [Google Scholar]

- Cookston JT, Braver SL, Griffin WA, De Luse S, & Miles J (2007). Effects of the dads for life intervention on interparental conflict and coparenting in the two years after divorce. Family Process, 46(1), 123–137. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookston JT, Braver SL, Sandler I, & Genalo MT (2002). Prospects for Expanded Parent Education Services for Divorcing Families with Children. Family Court Review, 40(2), 190–203. 10.1111/j.174-1617.2002.tb00830.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Family law practice note: Parenting after Separation, § Divorce Act and the Family Law Act (2015). https://albertacourts.ca/docs/default-source/qb/family-law-practice-note-1---parenting-after-separation-(effective-july-20-2015).pdf?sfvrsn=b1acad80_4

- Court Statistics Project. (2020). State Court Caseload Digest: 2018 Data (Court Statistics Project). National Center for State Courts. https://www.courtstatistics.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/40820/2018-Digest.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, & Davies P (2010). Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, & Wilson A (1999). Contexts of marital conflict and children’s emotional security: Exploring the distinction between constructive and destructive conflict from the children’s perspective. Conflict and Cohesion in Families: Causes and Consequences, 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge‐Apple ML, Winter MA, Cummings EM, & Farrell D (2006). Child Adaptational Development in Contexts of Interparental Conflict Over Time. Child Development, 77(1), 218–233. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy B (2020). Don’t Alienate the Kids!: Raising Resilient Children While Avoiding High-Conflict Divorce (2nd edition). Unhooked Books. [Google Scholar]

- Elam KK, Sandler I, Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, & Rogers A (2019). Latent profiles of postdivorce parenting time, conflict, and quality: Children’s adjustment associations. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(5), 499–510. 10.1037/fam0000484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM, Kouros CD, Elmore-Staton L, & Buckhalt J (2008). Marital Psychological and Physical Aggression and Children’s Mental and Physical Health: Direct, Mediated, and Moderated Effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 138–148. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elton C (2020). Is Massachusetts Shaming Divorced Parents? Boston Magazine. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2020/11/25/state-parenting-classes/ [Google Scholar]

- Erath SA, & Bierman KL (2006). Aggressive marital conflict, maternal harsh punishment, and child aggressive-disruptive behavior: Evidence for direct and mediated relations. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Brownson RC, & Pronk NP (2018). Dissemination and Implementation Science for Public Health Professionals: An Overview and Call to Action. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, E162. 10.5888/pcd15.180525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius W, & Luecken L (2007). Postdivorce living arrangements, parent conflict, and long-term physical health correlates for children of divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 195–205. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackrell TA, Hawkins AJ, & Kay NM (2011). How Effective Are Court-Affiliated Divorcing Parents Education Programs? A Meta-Analytic Study. Family Court Review, 49(1), 107–119. 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2010.01356.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farias Family Law, P.C. (n.d.). Don’t hate your ex more than you love your kids. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://www.billfariaslaw.com/dont-hate-your-ex-more-than-you-love-your-kids/

- Finkel EJ, Slotter EB, Luchies LB, Walton GM, & Gross JJ (2013). A Brief Intervention to Promote Conflict Reappraisal Preserves Marital Quality Over Time. Psychological Science, 24(8), 1595–1601. 10.1177/0956797612474938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T, de Graaf P, & Kalmijn M (2005). Friendly and antagonistic contact between former spouses after divorce: Patterns and determinants. Journal of Family Issues, 26(8), 1131–1163. 10.1177/0192513X05275435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Neighbors B, Devine D, & Armistead L (1994). Interparental conflict and parental divorce: The individual, relative, and interactive effects on adolescents across four years. Family Relations, 43(4), 387. 10.2307/585369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch M, & Degarmo D (1999). Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 711–724. 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM, & Cummings EM (2013). Changes in marital conflict and youths’ responses across childhood and adolescence: A test of sensitization. Development and Psychopathology, 25(1), 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Bonds D, Sandler I, & Braver S (2004). Parent psychoeducational programs and reducing the negative effects of interparental conflict following divorce. Family Court Review, 42(2), 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FEM, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, & Zafft KM (2015). Standards of Evidence for Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Scale-up Research in Prevention Science: Next Generation. Prevention Science, 16(7), 893–926. 10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hald GM, Ciprić A, Øverup CS, Štulhofer A, Lange T, Sander S, Gad Kjeld S, & Strizzi JM (2020). Randomized controlled trial study of the effects of an online divorce platform on anxiety, depression, and somatization. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(6), 740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW (2002). Prevention science principles for intervention (UNAFEI Annual Report for 2000, pp. 195–202) [200232]. [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, & Murch M (2005). Inter-Parental Conflict and Children’s Adaptation to Separation and Divorce: Theory, Research and Implications for Family Law, Practice and Policy. Child and Family Law Quarterly, 17, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, & Sellers R (2018). Annual Research Review: Interparental conflict and youth psychopathology: an evidence review and practice focused update. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 374–402. 10.1111/jcpp.12893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Towards a unified model of behavior change. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 226–227. 10.1002/wps.20626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, & Kelly J (2002). Divorce reconsidered: For better or worse. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob H (1988). Silent revolution: The transformation of divorce law in the United States. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JR (1994). High-Conflict Divorce. The Future of Children, 4(1), 165. 10.2307/1602483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston N, Atlas L, & Wager T (2012). Opposing effects of expectancy and somatic focus on pain. PLoS ONE, 7(6). https://myasucourses.asu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-18099352-dt-content-rid-136519750_1/courses/2018Fall-T-PSY543-91687/Johnsonetal2012PLOSOpposingEffects.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2017). Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 88, 7–18. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreeger Hon. J. L. (2008). FAMILY COURT IMPROVEMENT AND THE ART OF GRANTSMANSHIP: A JUDGE’S PERSPECTIVE. Family Court Review, 46(2), 331–339. 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2008.00203.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamela D, & Figueiredo B (2016). Coparenting after marital dissolution and children’s mental health: A systematic review. Jornal de Pediatria, 92(4), 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande J (2011). The revolution in family law dispute resolution. J. Am. Acad. Matrimonial Law, 24, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Long N, Slater E, Forehand R, & Fauber R (1988). Continued high or reduced interparental conflict following divorce: Relation to young adolescent adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(3), 467. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.3.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low RST, Overall NC, Cross EJ, & Henderson AME (2019). Emotion regulation, conflict resolution, and spillover on subsequent family functioning. Emotion, 19(7), 1162–1182. 10.1037/emo0000519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, & Bruns EJ (2019). User-centered redesign of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to enhance implementation—Hospitable soil or better seeds? JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 3. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, & Koerner K (2016). User-Centered Design for Psychosocial Intervention Development and Implementation. Clinical Psychology, 23(2), 180–200. 10.1111/cpsp.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliken AC, & Katz LF (2013). Exploring the Impact of Parental Psychopathology and Emotion Regulation on Evidence-Based Parenting Interventions: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Improving Treatment Effectiveness. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(2), 173–186. 10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino K, Kline Pruett M, & Fieldstone L (2016). Co-parenting in a highly conflicted separation/divorce: Learning about parents and their experiences of parenting coordination, legal, and mental health interventions. Family Court Review, 54(4), 564–577. [Google Scholar]

- Markham MS, Ferraro AJ, Russell LT, Beckmeyer JJ, Zimmermann ML, Guyette E, & Pippert HD (2021). Lessons From the Field: Developing a Multisite Divorce Education Evaluation Tool. Family Relations, 70(5), 1657–1663. 10.1111/fare.12575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew Z (2016). Reforming Direct Evaluation of Court-Mandated Parenting Classes. Mich. St. L. Rev, 1147. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie B, & Bacon B (2009). Parent education after separation: Results from a multi-site study on best practices. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 21(S4), 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff R, & Cooper K (2004). Parental Conflict Resolution. Family Court Review, 42(1), 99–114. 10.1111/j.174-1617.2004.tb00636.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noller P, Feeney JA, Sheehan G, Darlington Y, & Rogers C (2008). Conflict in divorcing and continuously married families: A study of marital, parent–child and sibling relationships. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 49(1–2), 1–24. 10.1080/10502550801971223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara KL, Knowles LM, Guastaferro K, & Lyon AR (2022). Human-centered design methods to achieve preparation phase goals in the multiphase optimization strategy framework. Implementation Research and Practice, 3, 26334895221131052. 10.1177/26334895221131052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara KL, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, & Tein J-Y (2019). Coping in context: The effects of long-term relations between interparental conflict and coping on the development of child psychopathology following parental divorce. Development and Psychopathology, 31(5), 1695–1713. 10.1017/S0954579419000981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés M, Carratalá E, & Espada JP (2015). Perceived quality of the parental relationship and divorce effects on sexual behaviour in Spanish adolescents. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(1), 8–17. 10.1080/13548506.2014.911922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Jordan PJ, & Bazzarre T (2002). The Behavior Change Consortium: Setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Education Research, 17(5), 500–511. 10.1093/her/17.5.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson P (2013). The Idea of Family Relationship Centres in Australia. Family Court Review, 51(2), 195–213. 10.1111/fcre.12020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, & Kirchner JE (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1). 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowen J, & Emery R (2018). Parental denigration: A form of conflict that typically backfires. Family Court Review, 56(2), 258–268. 10.1111/fcre.12339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd BN, & Beidas RS (2021). Reducing the Scientific Bench to Judicial Bench Research-to-Practice Gap: Applications of Implementation Science to Family Law Research and Practice. Family Court Review, 59(4), 741–754. 10.1111/fcre.12606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saini MA, Pruett MK, & Alschech J (2022). The Short-Form of the Coparenting Across Family Structures Scale (CoPAFS-27): A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(10), 2785–2800. 10.1007/s10826-022-02359-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini M, Pruett MK, Alschech J, & Sushchyk AR (2019). A pilot study to assess Coparenting Across Family Structures (CoPAFS). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(5), 1392–1401. 10.1007/s10826-019-01370-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem P, Sandler I, & Wolchik S (2013). Taking Stock of Parent Education in the Family Courts: Envisioning a Public Health Approach. Family Court Review, 51(1), 131–148. 10.1111/fcre.12014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, O’Hara KL, Wolchik SA, & Salem P (2022). The Case for Evidence-Based Parent Education Programs.

- Sbarra DA, & Emery RE (2005). Coparenting conflict, nonacceptance, and depression among divorced adults: Results from a 12-year follow-up study of child custody mediation using multiple imputation. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(1), 63–75. 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer T (2010). Saving children or blaming parents-lessons from mandated parenting classes. Colum. J. Gender & L, 19, 491. [Google Scholar]

- Schepard A (2004). Children, courts, and custody: Interdisciplinary models for divorcing families. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, Mullarkey MC, & Chacko A (2020). Harnessing Wise Interventions to Advance the Potency and Reach of Youth Mental Health Services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(1), 70–101. 10.1007/s10567-019-00301-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Weisz JR (2017). Little Treatments, Promising Effects? Meta-Analysis of Single-Session Interventions for Youth Psychiatric Problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 107–115. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm DG, & Becher EH (2020). Common Practices for Divorce Education. Family Relations, 69(3), 543–558. 10.1111/fare.12444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm DG, Kanter JB, Brotherson SE, & Kranzler B (2018). An Empirically Based Framework for Content Selection and Management in Divorce Education Programs. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 59(3), 195–221. 10.1080/10502556.2017.1402656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal A, Sandler I, Wolchik S, & Braver S (2011). Do parent education programs promote healthy post-divorce parenting? Critical distinctions and a review of the evidence. Family Court Review, 49(1), 120–139. 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2010.01357.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JB (2009). Dispute Resolution and the Postdivorce Family: Implications of a Paradigm Shift1. Family Court Review, 47(3), 363–370. 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2009.01261.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth BM, & Moloney LJ (2019). Post-separation parenting disputes and the many faces of high conflict: Theory and research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 74–84. 10.1002/anzf.1346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK, Hughes JN, & Simpson JA (2006). Family Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Research and Intervention. In Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Stich B (2014, January 4). Children of Divorce Effects: Hate Your Ex More Than You Love Your Kids? https://benstich.com/effects-of-divorce-on-children-of-divorce/

- Sullivan M, & Burns A (2020). Effective Use of Parenting Coordination: Considerations for Legal and Mental Health Professionals. Family Court Review, 58(3), 730–746. 10.1111/fcre.12509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum LE, & DuPaix L (1987). Alternative dispute resolution and divorce: Natural experimentation in family law. Rutgers L. Rev, 40, 1093. [Google Scholar]

- Troxel v Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (U.S. Supreme Court June 5, 2000)

- Vandewater EA, & Lansford JE (1998). Influences of family structure and parental conflict on children’s well-being. Family Relations, 47(4), 323–330. 10.2307/585263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM (2014). The New Science of Wise Psychological Interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 73–82. 10.1177/0963721413512856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Wilson TD (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmuth KA, Cummings EM, & Davies PT (2019). Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Journal of Family Psychology. 10.1037/fam0000599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshak RA (2010). Divorce Poison New and Updated Edition: How to Protect Your Family from Bad-mouthing and Brainwashing (Revised ed. edition). William Morrow Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Schenck CE, & Sandler IN (2009). Promoting resilience in youth from divorced families: Lessons learned from experimental trials of the New Beginnings Program. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1833–1868. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski M, Lewis JK, & Martin CG (2018). Identifying novel applications of dialectical behavior therapy: Considering emotion regulation and parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 122–126. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]