Abstract

This study explores how conformational asymmetry influences the bulk phase behavior of linear-brush block copolymers. We synthesized 60 diblock copolymers composed of poly(trifluoroethyl methacrylate) as the linear block and poly[oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate] as the brush block, varying the molecular weight, composition, and side-chain length to introduce different degrees of conformational asymmetry. Using small-angle X-ray scattering, we determined the morphology and phase diagrams for three different side-chain length systems, mainly observing lamellar and cylindrical phases. Increasing the side-chain length of the brush block from three to nine ethylene oxide units introduces sufficient asymmetry between the blocks to alter the phase behavior, shifting the lamellar-to-cylindrical transitions toward lower brush block compositions and transitioning the brush block from the dense comb-like regime to the bottlebrush regime. Coarse-grained simulations support our experimental observations and provide a mapping between the composition and conformational asymmetry. A comparison of our findings to strong stretching theory across multiple phase boundary predictions confirms the transition between the dense comb-like regime and the bottlebrush regime.

Introduction

Block copolymers (BCPs) are versatile materials, as they exhibit self-assembly into ordered nanostructures that combine the properties of their constituent blocks. In linear AB BCPs, the volume fraction of the A component (fA) and segregation strength (χN), where χ is the Flory–Huggins interaction parameter and N the total degree of polymerization, determine the nanoscale equilibrium morphology and feature size by quantifying the competition between the energetic stretching penalties of the blocks.1−3 In the case of nonlinear AB BCPs where one block is linear and the other exhibits a branched topology, conformational asymmetry must also be considered, as it can have a profound influence on the phase boundaries.4,5

Branched polymer

architectures, such as bottlebrushes, barbed wires,

comb-like and Y-shaped structures offer a pathway to thermodynamically

tune feature size and phase behavior by introducing a high degree

of conformational asymmetry and creating curved interfaces at symmetric

volume fractions during self-assembly.6,7 The parameter  is commonly used as a measure of conformational

asymmetry, accounting for differences in molecular architecture and

in how the blocks fill space8,9 (β is the ratio

of segment length to segment volume of each block). For conformationally

symmetric AB BCPs, ε is equal to 1. While conformational asymmetry

can alter the phase behavior of linear BCPs, accessible values of

ε are typically limited and close to 1.

is commonly used as a measure of conformational

asymmetry, accounting for differences in molecular architecture and

in how the blocks fill space8,9 (β is the ratio

of segment length to segment volume of each block). For conformationally

symmetric AB BCPs, ε is equal to 1. While conformational asymmetry

can alter the phase behavior of linear BCPs, accessible values of

ε are typically limited and close to 1.

Conformationally asymmetric BCP structures can enable larger or smaller domain spacings than those of analogous linear AB BCPs,10,11 offering compositional flexibility surpassing that of conformationally symmetric BCPs. However, moving from linear AB BCPs to more complex macromolecular architectures complicates the mapping of the design parameter space to the phase separation behavior. Experimental efforts have therefore focused on investigating the phase behavior as a function of additional variables, such as side-chain length and graft density of the branched blocks, to determine morphology and feature size and build the corresponding phase diagrams.6,12−16

Theoretical studies have attempted to predict the magnitude

and

direction of the deflection of the phase boundaries for a variety

of comb and bottlebrush polymer architectures. In particular, strong

stretching theory (SST) provides boundaries for the order–order

transitions between lamellar, cylindrical and sphere-forming phases

for linear-bottlebrush BCPs.17,18 These studies characterize

the order–order transition as a function of two parameters: fB, the volume fraction of the bottlebrush block,

and  , a parameter coupling the asymmetry between

blocks and the morphology of the bottlebrush block, where ηA and ηB are architecture-dependent topological

ratios that quantify the relative energetic contributions of the blocks.

For linear polymers, the parameter ηA is defined

as 1, while the combined parameter

, a parameter coupling the asymmetry between

blocks and the morphology of the bottlebrush block, where ηA and ηB are architecture-dependent topological

ratios that quantify the relative energetic contributions of the blocks.

For linear polymers, the parameter ηA is defined

as 1, while the combined parameter  for copolymers with a linear block A and

bottlebrush block B is

for copolymers with a linear block A and

bottlebrush block B is

| 1 |

where lA is the monomer A length, bA is the Kuhn length, υA is the monomer volume, nB is the bottlebrush side-chain length, and α is a numerical prefactor, which must be adjusted and fixed according to the position of one of the phase boundaries. Alternatively, for a linear-comb architecture, the scaling behavior of the asymmetry is quantitatively different and given by

| 2 |

where q is the number of side chains per branch, n is the side-chain length, and m is the spacer degree of polymerization.18 We note that in an ideal test of the scaling theory, α would be used to determine the boundaries across multiple phase transitions for both comb-like and bottlebrush-like polymers, but achieving this comparison in experiments can be difficult.

In addition to SST, self-consistent field theory (SCFT) has been used to predict the deflection of phase boundaries caused by asymmetry and to identify the gyroid window for certain BCP systems, with some studies showing good agreement between experiments and theory.5,19−24 Other field-theoretic efforts have focused on investigating the phase behavior of statistical bottlebrushes and establishing a universal phase diagram based upon the relation between asymmetry and bottlebrush architectural parameters.25,26 In these studies, which examined linear-brush BCPs with varying degrees of asymmetry across both the comb-like and bottlebrush regimes, the authors did not observe a transition between the comb-like and bottlebrush scaling of the phase diagram as described by Zhulina et al.(18) Instead, they found that the polymers behaved as combs in all cases and attributed the absence of such a transition to the inherent limitations of SCFT.

The inherent structural complexity of branched BCPs makes particle-based simulations computationally expensive,27,28 as they require long equilibration times for side chains with a large number of repeat units. While numerous simulation studies have examined the melt state of bottlebrushes with a focus on their conformal properties,29−31 BCP systems require extended times to self-assemble. Consequently, coarse-grained simulations are preferred over atomistic simulations for studying self-assembly behavior, although accurately mapping coarse-grained simulations to phase behavior is also difficult because the necessary parameter spaces ε, f, and χN must be indirectly inferred.

Several attempts have been made to circumvent these issues. One well-developed approach for simulating the self-assembly of bottlebrush polymers utilizes an implicit potential for the polymer side chain, which reduces the computational intensity.32,33 This approach shows good agreement with the experimental structure factors but has yet to be tested against scaling theories for phase boundaries. Other methods for predicting phase behavior employ distinct bonded interactions between the backbone and the side chain to accelerate simulation.34 In studies on the self-assembly of bottlebrush polymers in solution, the solvent has been either modeled implicitly35 or explicitly in combination with dissipative particle dynamics type models.36−38 None of these efforts, however, have been used to compare the scaling in asymmetry between combs and bottlebrushes, as theoretically proposed by Zhulina et al.(18)

While experimental and simulation studies have explored the phase behavior of linear-brush BCP architectures with varying degrees of conformational asymmetry, quantification of the extent of overlap between side chains as a function of side-chain length is frequently absent in these investigations. In linear-brush BCPs such as linear-comb and linear-bottlebrush, the nature of the architecture is given by the graft density and side-chain length. These two variables enable systematic control of conformation and the degree of overlap and entanglement with neighboring molecules,30,31,39 which has significant implications for the physical properties of polymers in both melt and solution states.40 Precise control of graft density, side-chain length, molecular weight, and tailored functional groups can be achieved through controlled/living polymerization techniques [i.e., atom transfer radical polymerization, reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization (NMP)], anionic polymerization, ring-opening polymerization, ring-opening metathesis polymerization, and “click” coupling reactions.41−43 These branched polymers have potential applications in areas such as nanolithography,44−47 biomedicine,48−50 energy storage,51−53 and beyond, emphasizing the importance of gaining a comprehensive understanding of their behavior.54

Here, we investigate how conformational asymmetry affects the bulk phase behavior of linear-brush BCPs consisting of poly(trifluoroethyl methacrylate) (PTFEMA) as the linear block and poly[oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate] (POEM) as the brush block. We use RAFT polymerization to synthesize a library of 60 PTFEMA-b-POEM copolymers with varying degrees of polymerization, composition and POEM side-chain length. In this study, we alter the degree of conformational asymmetry between the blocks by changing the side-chain length and systematically study the phase behavior. BCP morphology and the corresponding phase diagrams are determined for three PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymer systems [x = 3, 5, or 9: number of ethylene oxide (EO) units in the POEM side chain] using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Coarse-grained simulations support our experimental observations and enable a more complete mapping of the relationship between the composition and the conformational asymmetry. We test whether we observe a transition between comb- and bottlebrush-like behavior in simulation and verify the results of SST for both linear-brush architectures. A comparison of our findings to SST predictions further demonstrates the potential for using the theory for the design of highly asymmetric BCP systems.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the Linear-Brush Diblock Copolymers

The synthesis of PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers involved two steps (Scheme 1). First, we conducted RAFT polymerization of 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (TFEMA) using 2-cyano-2-propyl benzodithioate (CPBD) as the RAFT agent to obtain a series of PTFEMA with average molecular weights (Mn) ranging from 5.2 to 24.7 kg mol–1 (Figure S1). The RAFT polymerization of TFEMA exhibited first-order kinetic behavior, characterized by a linear relationship between the polymerization rate and the logarithm of the monomer concentration over time (Figure S2a). As the polymerization proceeded, Mn increased linearly with monomer conversion, while dispersity (D̵) remained narrow (Figure S2b). These observations indicate a well-controlled RAFT polymerization.55,56

Scheme 1. RAFT Polymerization Scheme for the Synthesis of PTFEMA-b-POEMx Copolymers.

Second, we performed the sequential polymerization of oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (OEMx, x = 3, 5, or 9: number of EO units) using the PTFEMA homopolymers synthesized in step 1 as RAFT agents. Following this protocol, we prepared two sets of diblock copolymers with similar Mn (around 20 and 30 kg mol–1) and different compositions for each side-chain length (Figures S6, S8, and S10). In a later section, we discuss where the POEM side-chain length becomes sufficient to be considered bottlebrush-like. Based upon the theoretical framework by Dobrynin and co-workers,31 we believe this transition occurs roughly at x = 5.

The chemical composition, Mn, and dispersity (D̵) of the resulting polymers were determined using 1H NMR, 19F NMR, and SEC. Detailed structural characterization of the full set of polymers is provided in the Supporting Information. The 1H NMR and 19F NMR spectra of PTFEMA (Figures S3 and S4) and PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers (Figures S5, S7 and S9) exhibited the characteristic chemical shifts corresponding to the protons and fluorine atoms present in the chemical structures of these polymers.57−61 The chemical compositions of the diblock copolymers were determined from the molar ratios calculated from the 1H NMR peak integrals of the −CH2–CF3 (δ = 4.34 ppm: s, 2H) and −C(O)–O–CH2– (δ = 4.08 ppm: s, 2H) signals ascribed to the PTFEMA and POEMx blocks, respectively. Table 1 lists the compositions in mass fraction of the brush block (xPOEMx), as well as the corresponding Mn and D̵ values for a representative set of PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers with approximately 30 kg mol–1. Dispersity ranged from 1.13 to 1.33, within the typical values obtained for well-controlled RAFT polymerization.

Table 1. Characteristics of the PTFEMA-b-POEMx Copolymers.

| BCP | Mn (kg mol–1) | D̵ | xPOEMxa | NPOEMxb | Ntotalb | fPOEMb | morphologyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFEMA-b-POEM3 | 31.3 | 1.33 | 0.21 | 79 | 319 | 0.25 | hexagonal |

| 30.7 | 1.33 | 0.24 | 88 | 315 | 0.28 | hex + lam | |

| 29.3 | 1.33 | 0.30 | 106 | 305 | 0.35 | lamellar | |

| 27.8 | 1.21 | 0.40 | 134 | 296 | 0.45 | lamellar | |

| 28.1 | 1.19 | 0.57 | 193 | 310 | 0.62 | hexagonal | |

| 29.0 | 1.15 | 0.69 | 241 | 328 | 0.73 | hexagonal | |

| 28.9 | 1.15 | 0.82 | 285 | 335 | 0.85 | disordered | |

| PTFEMA-b-POEM5 | 27.1 | 1.27 | 0.09 | 30 | 269 | 0.11 | disordered |

| 25.7 | 1.19 | 0.23 | 72 | 264 | 0.27 | hexagonal | |

| 27.7 | 1.20 | 0.26 | 87 | 286 | 0.31 | hex + lam | |

| 27.5 | 1.20 | 0.28 | 93 | 286 | 0.33 | lamellar | |

| 26.7 | 1.19 | 0.37 | 120 | 283 | 0.42 | lamellar | |

| 24.1 | 1.14 | 0.54 | 158 | 266 | 0.59 | hexagonal | |

| 26.0 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 252 | 303 | 0.83 | disordered | |

| PTFEMA-b-POEM9 | 27.4 | 1.24 | 0.15 | 51 | 277 | 0.18 | disordered |

| 29.1 | 1.26 | 0.20 | 73 | 299 | 0.24 | lamellar | |

| 28.0 | 1.22 | 0.25 | 87 | 291 | 0.30 | lamellar | |

| 27.9 | 1.21 | 0.29 | 101 | 293 | 0.34 | lamellar | |

| 29.1 | 1.18 | 0.32 | 116 | 308 | 0.38 | lamellar | |

| 30.4 | 1.19 | 0.45 | 170 | 332 | 0.51 | lam + hex | |

| 30.2 | 1.16 | 0.48 | 180 | 333 | 0.54 | hexagonal | |

| 31.2 | 1.18 | 0.57 | 221 | 351 | 0.63 | hexagonal | |

| 30.3 | 1.18 | 0.64 | 241 | 347 | 0.70 | hexagonal | |

| 28.8 | 1.13 | 0.74 | 266 | 339 | 0.79 | disordered | |

| 30.0 | 1.14 | 0.82 | 306 | 359 | 0.85 | disordered |

Calculated from the molar ratio of both blocks determined by 1H NMR.

Calculated using a 118 Å3 reference volume and densities of ρ(PTFEMA) = 1.45 g/cm3, ρ(POEM3) = 1.17 g/cm3 (25 °C), ρ(POEM5) = 1.16 g/cm3 (25 °C), and ρ(POEM9) = 1.13 g/cm3 (25 °C).

Determined using SAXS.

The total degree of polymerization (N) and volume fraction (f) of the blocks were calculated using the standard definitions for monomer volume equivalents (see Supporting Information). We assumed a density of 1.45 g cm–3 for PTFEMA, based on previous reports,62,63 and estimated the densities for POEM3, POEM5, and POEM9 using the van Krevelen group contribution method64,65 (1.17, 1.16, and 1.13 g cm–3, respectively). Table 1 shows the N and f values for a set of PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers.

Experimental Phase Diagrams and Impact of Side-Chain Length

We employed SAXS to further characterize the diblock copolymers on samples annealed for 20 h at 150 °C to favor self-assembly. Figure 1 displays the SAXS patterns obtained at room temperature for the PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers listed in Table 1. The SAXS patterns acquired for all the diblock copolymers, along with the peak indexing, are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S11–S13). Analysis of the SAXS data enabled us to map the bulk morphologies as functions of f and N and construct the phase diagrams illustrated in Figure 2. Notably, N is the vertical axis in our phase diagrams rather than segregation strength (χN); there is currently no theoretical framework for χ that accurately accounts for the entropic restrictions caused by the presence of side chains in branched BCP architectures.14

Figure 1.

Room temperature SAXS patterns for a representative set of the PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers (approximately 30 kg mol–1) as a function of the volume fraction of the POEMx block (fPOEMx). DIS, HEX, and LAM denote disordered, hexagonal (cylindrical), and lamellar phases, respectively.

Figure 2.

Phase diagrams determined by SAXS for the PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers as a function of volume fraction of the POEMx block (fPOEMx) and the total degree of polymerization (N); x denotes the number or EO units in the side chain of the brush block. The star symbol in the PTFEMA-b-POEM5 phase diagram denotes the possible coexistence of hexagonal and gyroid phases. Colors used for phase regions and dashed lines are exclusively intended as visual aids and should not be interpreted as delineating actual phase boundaries.

We identified disordered, hexagonal ( ...), and lamellar (

...), and lamellar ( ) phases from the corresponding SAXS patterns.

Multiple sets of scattering reflections were also observed at several

POEM volume fractions (fPOEMx) across the three linear-brush systems, indicating phase coexistence

near the phase boundaries. The presence of sharp primary and higher-order

peaks in the SAXS patterns of samples exhibiting ordered phases suggests

strong phase separation and long-range order. We found significant

differences between the linear-brush systems as the POEM side-chain

length increases from 3 to 9 EO units. The PTFEMA-b-POEM3 phase diagram closely resembles the conventional

phase diagram for a linear AB BCP, with the lamellar region 0.26 ≲ fPOEM3 ≲ 0.60. In PTFEMA-b-POEM3, the polymer segments are not substantially different

in the ratio of the statistical segment length to segment volume and

do not introduce sufficient conformational asymmetry to significantly

shift the phase boundaries.

) phases from the corresponding SAXS patterns.

Multiple sets of scattering reflections were also observed at several

POEM volume fractions (fPOEMx) across the three linear-brush systems, indicating phase coexistence

near the phase boundaries. The presence of sharp primary and higher-order

peaks in the SAXS patterns of samples exhibiting ordered phases suggests

strong phase separation and long-range order. We found significant

differences between the linear-brush systems as the POEM side-chain

length increases from 3 to 9 EO units. The PTFEMA-b-POEM3 phase diagram closely resembles the conventional

phase diagram for a linear AB BCP, with the lamellar region 0.26 ≲ fPOEM3 ≲ 0.60. In PTFEMA-b-POEM3, the polymer segments are not substantially different

in the ratio of the statistical segment length to segment volume and

do not introduce sufficient conformational asymmetry to significantly

shift the phase boundaries.

Increasing the side-chain length

by 2 EO units in the PTFEMA-b-POEM5 system

shows a slight narrowing of the

lamellar region to fPOEM5 ∼ 0.54.

When fPOEM5 = 0.25 and N = 319 (star symbol in the phase diagram), indexing of the SAXS pattern

suggests the coexistence of hexagonally packed cylinders and the gyroid

phase (Figure S12, entry # 14). We note

that the (220) diffraction peak associated with the gyroid phase and

characterized by  exhibits very low intensity in the corresponding

SAXS pattern. This peak appears as a shoulder within the primary peak,

making it difficult to assert with absolute certainty the presence

of the gyroid phase in the PTFEMA-b-POEM5 phase diagram.

exhibits very low intensity in the corresponding

SAXS pattern. This peak appears as a shoulder within the primary peak,

making it difficult to assert with absolute certainty the presence

of the gyroid phase in the PTFEMA-b-POEM5 phase diagram.

In contrast, the PTFEMA-b-POEM9 phase diagram exhibits significant asymmetry and deviates from that of conventional linear AB BCPs. The lamellar phase region shifts to 0.18 ≲ fPOEM9 ≲ 0.5, while the cylindrical phase region spans 0.5 ≲ fPOEM9 ≲ 0.8. Linear AB BCPs exhibit cylindrical morphology at a minority block fraction of f < 0.3. The side-chain length of 9 EO units introduces a high degree of conformational asymmetry between the blocks, which changes the relative stretching penalties of the blocks and consequently affects phase behavior. Specifically, when the linear blocks are the minority, the system exhibits a thermodynamic preference for spontaneous curvature toward the linear blocks, resulting in the formation of hexagonally packed PTFEMA cylinders in a POEM9 matrix.

The influence of conformational asymmetry on the phase diagram of diverse branched diblock copolymer architectures have been investigated through SCFT in the strong segregation regime.4,5 Our experimental findings align with a recent SCFT computational study conducted by Park et al.,21 which focused on investigating the stability of double gyroid network phases in bottlebrush diblock copolymer melts. For linear-bottlebrush architectures, these SCFT calculations predict that when the linear blocks constitute the minority, increasing the side-chain length of the bottlebrush block leads to a shift in the phase boundaries toward higher compositions of the linear block.

Additionally, Liberman et al. conducted comprehensive experimental studies on norbornene-based linear-bottlebrush BCPs, systematically varying polarity of the linear block and side-chain length of the bottlebrush block.14,15 They observed hexagonally packed cylinders, double gyroid and lamellae phases in a set of 223 diblock copolymers with volume fractions of the linear block ranging from 0.30 to 0.70, total degrees of polymerization ranging from 30 to 140, and side-chain lengths from 1 to 9 ethylene-alt-propylene repeat units.15 These studies show that increasing the conformational asymmetry induces phase coexistence and shifts the phase boundaries toward lower compositions of the linear block, altering the double gyroid compositional window. As conformational asymmetry increases, the maximum values and ranges of N associated with the gyroid-forming copolymer decrease while the χ parameter increases, resulting in limited or no access to the order–disorder transition (ODT). The absence of gyroid phases in our phase diagrams may result from the narrowing of the compositional window derived from asymmetry, making it difficult to experimentally access that region, and the limited or no access to the ODT, as PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers likely exhibit a high χ value.

Assessment of POEMx Bottlebrush-like Behavior

The scaling model of graft polymers introduced by Dobrynin classifies comb-like and bottlebrush architectures in a melt based on the crowding parameter, Φ.30,31 This parameter quantifies the degree of interpenetration between side chains and the backbones of neighboring macromolecules by comparing the volume occupied by the side chains of a single polymer to the side chain pervaded volume. The transition from an unstretched state to the bottlebrush state occurs at Φ ≈ 1, although this transition is relatively broad. In the comb regime (Φ < 1), the side chains and backbones of adjacent macromolecules interpenetrate, causing comb-like architectures to behave similar to linear chain backbones. Conversely, in the bottlebrush regime (Φ ≥ 1), steric repulsion between side chains prevents interpenetration between macromolecules.30,31 Consequently, proper classification of polymers as comb-like or bottlebrush-like is critical because the calculation of asymmetry between these two regimes is different. To calculate Φ, we follow the work of Dobrynin and first estimate the volume pervaded by the side chain as

| 3 |

where Ns is the side-chain degree of polymerization and b is the statistical segment length.

The approximate amount of the pervaded volume filled by the chain itself is the sum of the backbone volume and side chain volume of a chain with a length equal to the backbone. The corresponding number of backbone monomers is given by

| 4 |

where NBB is the number of backbone monomers and bBB is the unperturbed statistical segment length of the backbone. The total volume is thus

| 5 |

where υBB and υs are the relevant monomer volumes. Note that up to this point, we have not assumed equivalent volume or flexibility between the backbone and side chains, which is particularly relevant in the case of POEM, where the PEO-like side chains and the PMMA-like backbone have drastically different volumes and flexibilities. Combining eqs 3–5, the expression of Φ is given by

| 6 |

which reduces to the expression given by Dobrynin30 if it is assumed the volumes and statistical segment lengths are equal between the backbone and the side chain.

Results from these calculations for the experimental and simulated systems are presented in Figure 3. Surprisingly, despite the low degree of polymerization of the side chains in the examined POEM blocks, we find both POEM5 and POEM9 to be at the threshold of transitioning into well-defined bottlebrush structures with Φ values very close to 1. While for POEM5 Φ is slightly below 1 (∼0.9), this value is sufficient for the polymer to begin exhibiting bottlebrush-like behavior in the first regime, in which crowding of side chains begins to stretch the polymer backbone. In contrast, Φ is < 1 for POEM3, which indicates that the polymer is in the comb regime. The simulated system also follows this trend, and brush blocks with side-chain lengths of five simulation beads or greater can reasonably be classified as bottlebrush-like. This is relevant as numerous experimental studies on bottlebrush architectures lack characterization of the comb-to-bottlebrush transition and often report the synthesis of longer brushes, usually involving side chains comprising tens or more monomer units.41,54 Our observations suggest that brushes of shorter length may be enough for certain systems to exhibit bottlebrush-like behavior. These findings emphasize the important role that side-chain length plays in the design of BCPs with branched architectures. It not only influences phase behavior but also governs the comb-to-bottlebrush transition, which has significant implications for the physical properties (e.g., rheological and mechanical)40,66 and processability of these polymers in both the melt and solution states.

Figure 3.

Crowding parameter Φ vs side-chain length for POEM. Circles represent the experimental systems chosen, and the green solid line represents the simulated systems. The blue solid line represents the value of Φ for other POEM side-chain lengths based on the experimental results. The dashed line is Φ = 1, bottlebrush regime. Φ values were calculated from eq 6. For the POEM system, bs was assumed to be equal to 0.56 nm, bBB = 0.65 nm, υBB = 0.14 nm3, and υs = 0.067 nm3. Discrepancy between simulation and experimental points is due to the discretization difference in the coarse-grained simulation.

Comparison of Experiments with Theoretical Order–Order Transitions

Subsequently, we aimed to compare the experimentally

observed order–order phase transitions for the three linear-bottlebrush

BCP systems with those predicted by SST. These order–order

transitions are described by the asymmetry parameter  and the volume fraction of the brush fB, as opposed to those used in the previous

phase diagrams described by N and fB. This comparison attempts to establish the relationship

between the polymer architecture and morphology. With larger values

of

and the volume fraction of the brush fB, as opposed to those used in the previous

phase diagrams described by N and fB. This comparison attempts to establish the relationship

between the polymer architecture and morphology. With larger values

of  , the brush-like block becomes more asymmetric,

and the tendency for the interface to curve away from the brush-like

block increases.

, the brush-like block becomes more asymmetric,

and the tendency for the interface to curve away from the brush-like

block increases.

To compare between theory and experiments,

we compute the parameter  for each architecture pairing. However,

this requires assigning a value to each constant in eq 1. While constants such as lA and bA in this

equation have reliable literature values, the parameter α is

a numerical prefactor not easy to measure experimentally. We followed

the methodology presented by Zhulina et al.,18 which utilizes the placement of one order–order

transition to determine the numerical prefactor and further calculates

it for the POEM9 system using the lamella-to-cylinder transition

where the major volume fraction is bottlebrush. This transition and

system best reflect the phase behavior because the majority bottlebrush

lamellar-to-cylindrical transition is the deepest in the ordered phase

with the longest blocks and thus closest to the conditions assumed

in SST. Using this prefactor alongside the ηB scaling,

we then determine the values of

for each architecture pairing. However,

this requires assigning a value to each constant in eq 1. While constants such as lA and bA in this

equation have reliable literature values, the parameter α is

a numerical prefactor not easy to measure experimentally. We followed

the methodology presented by Zhulina et al.,18 which utilizes the placement of one order–order

transition to determine the numerical prefactor and further calculates

it for the POEM9 system using the lamella-to-cylinder transition

where the major volume fraction is bottlebrush. This transition and

system best reflect the phase behavior because the majority bottlebrush

lamellar-to-cylindrical transition is the deepest in the ordered phase

with the longest blocks and thus closest to the conditions assumed

in SST. Using this prefactor alongside the ηB scaling,

we then determine the values of  for the other two systems.

for the other two systems.

Figure 4 plots the

order–order transitions as discussed previously as well as

morphology as a function of the POEM volume fraction for the series

of PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers listed in Table 1. The results are best understood

by comparing the majority bottlebrush lamella-to-cylinder transition

separately from the majority linear lamella-to-cylinder transition.

The lamella-to-cylinder transition in the majority bottlebrush region

shows excellent agreement between SST and the experimental results,

and both the POEM5 and POEM3 BCP systems scale

with n1/4B based on SST, even though POEM3 is not a bottlebrush

polymer. In contrast, the lamella-to-cylinder transition in the minority

bottlebrush region occurs earlier than would be otherwise predicted

by SST. It is noteworthy that changing how we determined the parameter  alone cannot resolve this discrepancy,

as the width between these points is determined solely by fB, which is known with high accuracy. Any shift

large enough to correct the issue would also introduce a correspondingly

large error in the majority of the bottlebrush transition. Instead,

we hypothesize that this phase diagram deviation arises from our system

not being in the strong-stretching segregation regime, as assumed

in the theory. The absence of a further spherical phase and the presence

of disorder in the experimental phase diagrams may suggest that we

are approaching an ODT. If so, this suggests that in the experimental

system, the degree of segregation is weaker than that required by

SST. While there does not exist in the literature a study that combines

the effects of conformational asymmetry and variable segregation strength,

we suspect that the behavior may be similar to the symmetric case,

where weaker segregation leads to a narrowing of the lamellar window.

alone cannot resolve this discrepancy,

as the width between these points is determined solely by fB, which is known with high accuracy. Any shift

large enough to correct the issue would also introduce a correspondingly

large error in the majority of the bottlebrush transition. Instead,

we hypothesize that this phase diagram deviation arises from our system

not being in the strong-stretching segregation regime, as assumed

in the theory. The absence of a further spherical phase and the presence

of disorder in the experimental phase diagrams may suggest that we

are approaching an ODT. If so, this suggests that in the experimental

system, the degree of segregation is weaker than that required by

SST. While there does not exist in the literature a study that combines

the effects of conformational asymmetry and variable segregation strength,

we suspect that the behavior may be similar to the symmetric case,

where weaker segregation leads to a narrowing of the lamellar window.

Figure 4.

Asymmetry phase diagram for the experimental PTFEMA-b-POEMx systems listed in Table 1. The x axis is the relative volume fraction of bottlebrush block fB, while the y axis is the asymmetry parameter. nB denotes the number of repeat units in the side chains. Yellow and green solid lines represent the cylinder-to-lamella and lamella-to-cylinder transitions predicted by the SST.

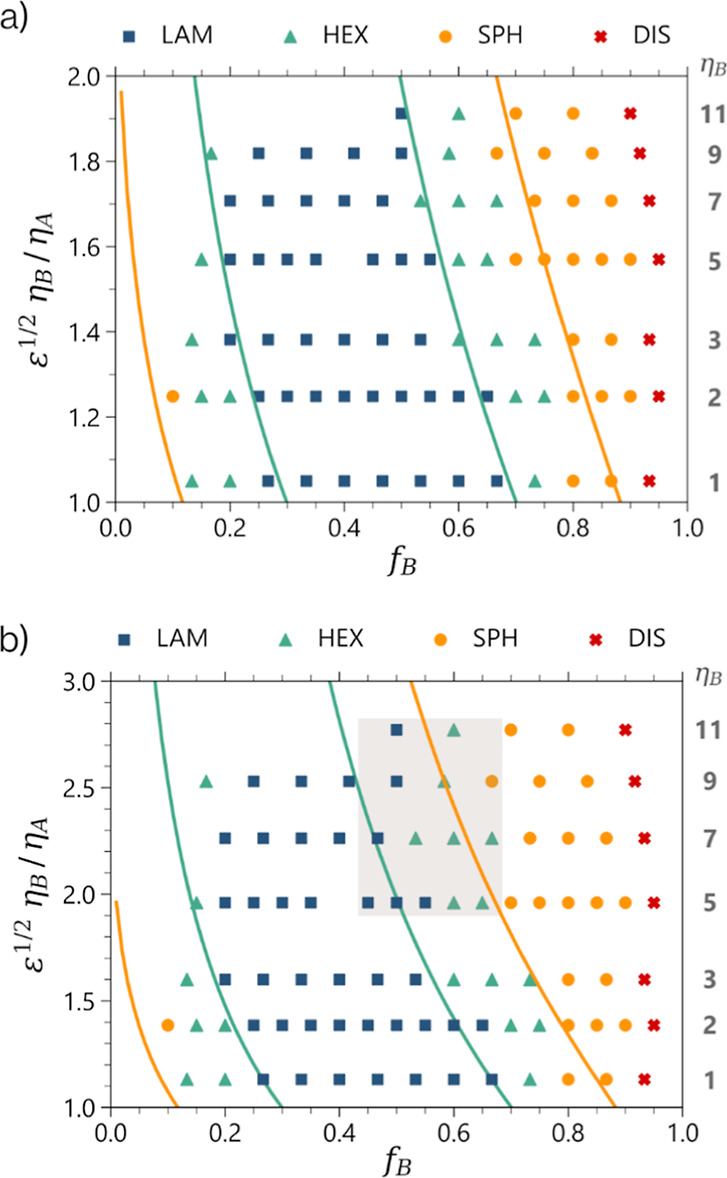

Comparison of Simulations with Theoretical Order–Order Transitions

Simulation methods enabled the exploration of the phase diagram for a variety of asymmetries to further investigate the effects of asymmetry and order–order transitions in the PTFEMA-b-POEMx systems. For all simulations, the diblock copolymer consisted of 120 total beads distributed between the linear block and the brush-like block. We changed the number of chains in the brush-like block while keeping the number of total beads constant, following a similar approach as Wessels and Jayaraman.36 This resulted in a significant variation in the volumetric degree of polymerization in the brush-like block, as in our experiments. Details on the architectures studied can be found in the Supporting Information (Tables S9 and S10).

The asymmetry parameter  can be calculated alongside the unperturbed

linear parameters for the simulated BCP system based on simulations

of the bottlebrush homopolymer for various side-chain lengths, where

α is used as an adjustable parameter. The resulting phase diagram

is displayed in Figure 5a. Intermediate phases are difficult to determine without resorting

to free energy methods and have not been resolved in this study. This

is especially true for the lamellar phase and the majority of bottlebrush

cylinder phases, which feature a substantial number of perforated

lamellar-like structures. The theoretical phase boundaries were calculated

as described by Zhulina et al.(17) and are depicted as solid lines.

can be calculated alongside the unperturbed

linear parameters for the simulated BCP system based on simulations

of the bottlebrush homopolymer for various side-chain lengths, where

α is used as an adjustable parameter. The resulting phase diagram

is displayed in Figure 5a. Intermediate phases are difficult to determine without resorting

to free energy methods and have not been resolved in this study. This

is especially true for the lamellar phase and the majority of bottlebrush

cylinder phases, which feature a substantial number of perforated

lamellar-like structures. The theoretical phase boundaries were calculated

as described by Zhulina et al.(17) and are depicted as solid lines.

Figure 5.

Simulated asymmetry phase diagrams for the PTFEMA-b-POEMx systems determined by using (a) bottlebrush and (b) comb scaling methods. The x axis is the relative volume fraction of bottlebrush block fB, while the y axis is the asymmetry parameter. nB denotes the number of beads in the side chains. Yellow and green solid lines represent the cylinder-to-lamella and lamella-to-cylinder transitions predicted by the SST. Note that these lines are the same in both plots, but the asymmetry parameter was calculated using either eq 1 (bottlebrush scaling) or eq 2 (comb scaling), respectively. The shaded area highlights the discrepancies observed in the lamella-to-cylinder transition for the comb-like scaling between the simulation data and SST for BCPs with side chains of 5 or more monomer units.

The comparison of the experimental and simulated phase diagrams affords several observations. First, contrary to previous literature,14,15,21 we surprisingly do not find a gyroid phase, which agrees with our experimental results. The gyroid phase is notoriously difficult to manifest in particle-based simulations due to the sensitive requirements of matching the unit cell dimension; even if a stable gyroid phase window exists, it is unlikely to be encountered. Additionally, χ is relatively high in the simulated system, resulting in a narrow gyroid region that can be easily overlooked. Second, we observe spherical phases at higher fB compositions in the simulated phase diagrams in contrast to the experimental ones. This discrepancy might be related to the fact that the spherical phase window is very narrow before the system disorders and may have been missed in the experimental systems, where the resolution of fB is lower. Moreover, the energy barrier could be large such that, at the temperature samples were measured, it would be difficult for the spherical phases to nucleate. Lastly, the phase boundaries shift to lower values of fB, in agreement with the SST, as the large bottlebrush monomer force increases the interfacial curvature to accommodate their conformations. The SST predictions for the order–order transitions show remarkable agreement with the simulation results in the transitions observed between each ordered phase. Moreover, it is worthwhile noting that even though all the polymers with Φ close to one fit well using eq 1 for the linear-bottlebrush BCP architectures, we see some deviation for the shorter side chain polymers, ns equal to one and two.

The theoretical model proposed by Zhulina et al.(18) predicts a difference in scaling of the asymmetry parameter between a comb-like and a more bottlebrush-like polymer architecture. To investigate this further, we calculated the asymmetry parameter for linear-comb BCP architectures with varying side-chain length according to eq 2.18 Upon plotting the phase behavior using eq 2 in Figure 5b, we observe a good fit for 1, 2, and 3 bead side chains. However, as side-chain length increases, the trend predicted by eq 2 overestimates the asymmetry of the bottlebrush polymers (1/2 scaling for combs versus 1/4 scaling for bottlebrushes). This overestimate results in an incorrect prediction for the lamella-to-cylinder transition for the more asymmetric bottlebrush polymers.

From this analysis, we conclude that BCPs with lower side-chain lengths are best described as linear-comb, while those with longer side-chain lengths exhibit proper bottlebrush behavior, in agreement with the findings by Zhulina.18 We believe that this behavior suggests that there does exist a transition in the phase behavior when moving from comb-like to bottlebrush-like side chains.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the phase behavior of a family of PTFEMA-b-POEMx copolymers. Alongside experiments, we performed simulations on a coarse-grained BCP system with a wide range of side-chain lengths to further explore the phase diagram as a function of conformational asymmetry. The experimental and simulated systems agree well with the SST, with the latter showing stronger agreement. We attribute discrepancies in the experimental system, particularly in the lamella-to-cylinder transition in the minority bottlebrush region, to its proximity to the ODT. Nevertheless, our study demonstrates that SST can be used to design highly asymmetric BCP systems that self-assemble into predictable morphologies, even at unconventional volume fractions.

A key aspect of our study is the comparison of the experimental and simulation data to SST predictions for the corresponding phase boundaries as the system transitions from a comb-like block to a bottlebrush block architecture. We find evidence that suggests that this transition occurs within the range of side-chain lengths studied. Our findings align with the argument of Fredrickson that the absence of predictions of bottlebrush behavior in their SCFT stems from modeling the system using a mean-field approach and highlight the importance of treating these two branched architectures differently when studied from a theoretical standpoint.

The close agreement between the simulation work in this study and the theory is quite remarkable. The use of a simulated polymer system with identical monomer volumes and bonds between monomers enabled a clean test of the SST and precluded speculation on certain asymmetries. By delineating the regime for which SST works, we show that this theoretical framework can be used to guide the future design of these systems to accelerate material development.

Experimental Section

Materials

TFEMA (99%), OEMx (x = 3, 5, or 9; Mn = 232.27 g mol–1, Mn = 300 g mol–1, and Mn = 500 g mol–1, respectively), CPBD (>97%), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), and deuterated chloroform [CDCl3, 99.8 atom % D, 0.03% (v/v) TMS] were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tetrahydrofuran (THF, HPLC grade) and hexanes were purchased from Fisher Chemical. TFEMA and OEMx monomers were purified before use to remove inhibitors by being passed through a column of basic alumina. AIBN was recrystallized in ethanol before use.

Synthesis of the PTFEMA Macro-Chain Transfer Agents

PTFEMA macro-chain transfer agents (macro-CTA) were synthesized via RAFT polymerization of TFEMA in THF using CPBD as the chain transfer agent and AIBN as the initiator. Number average molecular weights (Mn) of 10, 25, 35, 45, and 50 kg mol–1 were targeted to obtain a series of homopolymers with varying Mn while keeping TFEMA monomer conversion well below 75% to reduce prevalence of dead polymer chains.

To synthesize PTFEMA (Mn target = 10 kg mol–1), the following procedure was used. TFEMA (4 g, 23.8 mmol), CPBD (88.5 mg, 0.4 mmol), AIBN (6.6 mg, 0.04 mmol), and THF (2.985 mL, ∼ 8 M) were stirred in a reaction tube and purged with dry N2 for 20 min. Multiple tubes with the same reagent quantities were prepared and placed in a carousel reactor for conducting parallel kinetics experiments and polymerizations. The reaction temperature was maintained at 70 °C, and the reflux carousel head was cooled by using water at 5 °C. Polymerization reactions were quenched by rapidly immersing the tubes in liquid N2 at different times, followed by exposure to air. Aliquots were taken from the crude solutions to assess monomer conversion. The crude solutions were precipitated into excess hexanes, followed by redissolution in THF and precipitation in hexanes two more times. The resulting polymers were dried at 50 °C under vacuum overnight. The same experimental protocol and conditions were followed when targeting Mn of 25, 35, 45, and 50 kg mol–1.

Synthesis of the PTFEMA-b-POEMx Copolymers

PTFEMA-b-POEMx (x = 3, 5, or 9: number of EO side-chain units) copolymer series of ∼20 and 30 kg mol–1 were synthesized via RAFT polymerization of OEMx monomers with PTFEMA as the RAFT agent and AIBN as the initiator. For instance, PTFEMA-b-POEM9 (Table S4, entry # 6) was synthesized by mixing PTFEMA # 4 (Mn = 7.5 kg mol–1, 0.5 g, 67 μmol), OEM9 (1.55 g, 3.1 mmol), AIBN (1.1 mg, 6.7 μmol), and THF (2.83 mL, [OEM9] ∼ 1 M) in a reaction tube and purged with dry N2 for 20 min. The reaction temperature was 70 °C and the reflux carousel head was cooled using water at 5 °C. Polymerization reactions were quenched by rapidly immersing the tubes in liquid N2 at different time points, followed by exposure to air. The crude solutions were precipitated into excess hexanes, followed by redissolution in THF and precipitation in hexanes two more times. The resulting BCPs were dried at 50 °C under a vacuum overnight. PTFEMA-b-POEM5 and PTFEMA-b-POEM3 copolymers were synthesized following the same synthesis and purification protocols. 1H NMR spectra of representative sets of PTFEMA-b-POEMx are shown in Figures S5, S7, and S9. GPC traces for the complete series of the diblock copolymers are shown in Figures S6, S8, and S10, while a summary of the reaction parameters employed and their corresponding TFEMA mass fraction (xTFEMA), Mn, and D̵ are listed in Tables S2–S4.

Proton (1H) and Fluorine (19F) Nuclear Magnetic Spectroscopy

1H and 19F NMR experiments were performed on a 400 MHz Bruker AVANCE III HD Nanobay spectrometer equipped with an iProbe SmartProbe. Spectra were acquired at 25 °C using CDCl3 as a solvent and a polymer concentration between 10 and 15 mg mL–1. For 1H NMR spectra acquisition, 64 scans were collected at a relaxation delay time of 5 s to determine conversion and chemical composition; while for 19F NMR spectra, 32 scans were collected at a relaxation delay time of 1 s. Proton chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS), and all data were processed with Mnova NMR software.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) measurements were conducted on a Wyatt/Shimadzu instrument using THF as an eluent at a flow rate of 1 mL min–1. Polymer solutions were prepared at a concentration of 4 mg mL–1 and passed through 0.20 μm poly(tetrafluoroethylene) filters. Separation was achieved using two Agilent PLgel 5 μm Mix-D columns maintained at 27 °C after injection of 35 μL of polymer solution. Number average molecular weight (Mn) and dispersity (D̵) were determined by comparison with polystyrene standards.

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering

SAXS measurements were performed using the SAXSLAB GANESHA instrument at the University of Chicago X-ray Facility. Prior to the experiments, dry diblock copolymer samples were annealed in bulk under vacuum at 150 °C for 20 h and then slowly cooled to ambient temperature. Data was collected at ambient temperature for 30 min.

Simulation Details

The simulation utilized is a simple dissipative particle dynamic-like soft model. The bonded interactions between beads are governed by a potential

| 7 |

with k equal to 4.0. The nonbonded potential between beads is governed by

| 8 |

where the factor σ is equal to one and ϵii is equal to 25kBT. For unlike beads, the interaction is defined by ϵij = ϵii + αij. For the simulations present here, αAB has been set to 1.5kBT, which controls the free energy of mixing, with a higher value of α corresponding to a higher free energy of mixing and thus decreased contact between the A and B type beads. Molecular dynamics simulations are carried out in the NPT ensemble with T = 1.0 and P = 20.249 to achieve a bead density of approximately ρ = 3.0/σ3. In this ensemble, only the y and z dimensions are coupled to each other, while x is allowed to freely fluctuate to allow the box dimensionality to fluctuate and relax to be commensurate with the lowest free energy phase. All calculations were carried out using HOOMD-blue v2.9.3.67 All simulations were allowed to relax over 500τ60, where τ60 is the time for the linear part of the diblock to relax when it is composed of 60 beads or fA equal to 0.50.

For each linear block brush block architecture, chains were randomly placed and then allowed to equilibrate as listed above. In all cases, fA was varied from approximately 0.2 to 0.8, stopping at NB equal to 3, where NB is the degree of polymerization. The side-chain length was denoted as nB and varied from 1 all the way to 9. The bond constants were held the same in both blocks, and so the only changes in conformal asymmetry originate from the different monomer side-chain lengths and conformal changes due to stretching the bottlebrush. The asymmetries in this system are designed to span the range of those encompassed by the experimental system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, where the jobs for generating the lamellar data were run. This work also made use of the shared facilities at the University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, supported by the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-2011854. R.S. also thanks Pablo Zubieta, Benjamin Ketter, and Peter Bennington for helpful discussions and suggestions that improved the content and clarity of the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.macromol.3c02180.

1H NMR and 19F NMR spectra, SEC traces, SAXS patterns, molecular characteristics of the linear-bottlebrush BCPs, density estimation by the van Krevelen group contribution method, parameters setting for SCFT from experimental data, SCFT parameters, and simulation details (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ R.J.S.-L. and J.A.M. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bates F. S. Polymer-Polymer Phase Behavior. Science (1979) 1991, 251 (4996), 898–905. 10.1126/science.251.4996.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Fredrickson G. H. Block copolymer thermodynamics: Theory and Experiment. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1990, 41, 525–557. 10.1146/annurev.pc.41.100190.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Fredrickson G. H. Block Copolymers—Designer Soft Materials. Phys. Today 1999, 52 (2), 32–38. 10.1063/1.882522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen M. W.; Bates F. S. Conformationally Asymmetric Block Copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. B: Polym. Phys. 1997, 35, 945–952. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen M. W. Effect of Architecture on the Phase Behavior of AB-Type Block Copolymer Melts. Macromolecules 2012, 45 (4), 2161–2165. 10.1021/ma202782s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runge M. B.; Lipscomb C. E.; Ditzler L. R.; Mahanthappa M. K.; Tivanski A. V.; Bowden N. B. Investigation of the Assembly of Comb Block Copolymers in the Solid State. Macromolecules 2008, 41 (20), 7687–7694. 10.1021/ma8009323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runge M. B.; Bowden N. B. Synthesis of High Molecular Weight Comb Block Copolymers and Their Assembly into Ordered Morphologies in the Solid State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (34), 10551–10560. 10.1021/ja072929q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Fredrickson G. H. Conformational Asymmetry and Polymer-Polymer Thermodynamics. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (4), 1065–1067. 10.1021/ma00082a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Schulz M. F.; Khandpur A. K.; Förster S.; Rosedale J. H.; Almdal K.; Mortensen K. Fluctuations, Conformational Asymmetry and Block Copolymer Phase Behaviour. Faraday Discuss. 1994, 98 (0), 7–18. 10.1039/FD9949800007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J.; Bailey T. S.; Rzayev J. Large Pore Size Nanoporous Materials from the Self-Assembly of Asymmetric Bottlebrush Block Copolymers. Nano Lett. 2011, 11 (3), 998–1001. 10.1021/nl103747m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minehara H.; Pitet L. M.; Kim S.; Zha R. H.; Meijer E. W.; Hawker C. J. Branched Block Copolymers for Tuning of Morphology and Feature Size in Thin Film Nanolithography. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (6), 2318–2326. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gai Y.; Song D. P.; Yavitt B. M.; Watkins J. J. Polystyrene-Block-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Bottlebrush Block Copolymer Morphology Transitions: Influence of Side Chain Length and Volume Fraction. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (4), 1503–1511. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Nam J.; Seo M.; Li S. Side-Chain Density Driven Morphology Transition in Brush-Linear Diblock Copolymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11 (4), 468–474. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman L.; Coughlin M. L.; Weigand S.; Bates F. S.; Lodge T. P. Phase Behavior of Linear-Bottlebrush Block Polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (7), 2821–2831. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman L.; Coughlin M. L.; Weigand S.; Edmund J.; Bates F. S.; Lodge T. P. Impact of Side-Chain Length on the Self-Assembly of Linear-Bottlebrush Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (12), 4947–4955. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fei H. F.; Yavitt B. M.; Hu X.; Kopanati G.; Ribbe A.; Watkins J. J. Influence of Molecular Architecture and Chain Flexibility on the Phase Map of Polystyrene-Block-Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Brush Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (17), 6449–6457. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhulina E. B.; Sheiko S. S.; Borisov O. V. Theory of Microphase Segregation in the Melts of Copolymers with Dendritically Branched, Bottlebrush, or Cycled Blocks. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8 (9), 1075–1079. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhulina E. B.; Sheiko S. S.; Dobrynin A. V.; Borisov O. V. Microphase Segregation in the Melts of Bottlebrush Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2020, 53 (7), 2582–2593. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen M. W.; Schick M. Microphases of a Diblock Copolymer with Conformational Asymmetry. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (14), 4014–4015. 10.1021/ma00092a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Jiang Z.; Yang H.; Xue G. Side Chain Effect on the Self-Assembly of Coil-Comb Copolymer by Self-Consistent Field Theory in Two Dimensions. Polymer (Guildf) 2013, 54 (26), 7080–7087. 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.10.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. J.; Cheong G. K.; Bates F. S.; Dorfman K. D. Stability of the Double Gyroid Phase in Bottlebrush Diblock Copolymer Melts. Macromolecules 2021, 54 (19), 9063–9070. 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c01654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gadelrab K. R.; Alexander-Katz A. Effect of Molecular Architecture on the Self-Assembly of Bottlebrush Copolymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124 (50), 11519–11529. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c07941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsin S. J.; Rions-Maehren T. G.; Beam M. D.; Bates F. S.; Hillmyer M. A.; Matsen M. W. Bottlebrush Block Polymers: Quantitative Theory and Experiments. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (12), 12233–12245. 10.1021/acsnano.5b05473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R. K. W.; Matsen M. W. Field-Theoretic Simulations of Bottlebrush Copolymers. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149 (18), 184901. 10.1063/1.5051744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Quah T.; Delaney K. T.; Fredrickson G. H. Investigation of the Self-Assembly Behavior of Statistical Bottlebrush Copolymers via Self-Consistent Field Theory Simulations. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (20), 9324–9333. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c01622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil D. L.; Quah T.; Sun D.; Delaney K. T.; Fredrickson G. H. Self-Consistent Field Theory Predicts Universal Phase Behavior for Linear, Comb, and Bottlebrush Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (11), 4237–4244. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chremos A.; Theodorakis P. E. Morphologies of Bottle-Brush Block Copolymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3 (10), 1096–1100. 10.1021/mz500580f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chremos A.; Theodorakis P. E. Impact of Intrinsic Backbone Chain Stiffness on the Morphologies of Bottle-Brush Diblock Copolymers. Polymer (Guildf) 2016, 97, 191–195. 10.1016/j.polymer.2016.05.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.; Carrillo J. M. Y.; Sheiko S. S.; Dobrynin A. V. Computer Simulations of Bottle Brushes: From Melts to Soft Networks. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (14), 5006–5015. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H.; Cao Z.; Wang Z.; Sheiko S. S.; Dobrynin A. V. Combs and Bottlebrushes in a Melt. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (8), 3430–3437. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H.; Wang Z.; Sheiko S. S.; Dobrynin A. V. Comb and Bottlebrush Graft Copolymers in a Melt. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (10), 3942–3950. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T.; Patel B. B.; Walsh D. J.; Dutta S.; Guironnet D.; Diao Y.; Sing C. E. Implicit Side-Chain Model and Experimental Characterization of Bottlebrush Block Copolymer Solution Assembly. Macromolecules 2021, 54 (8), 3620–3633. 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c00336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T.; Dutta S.; Sing C. E. Interaction Potential for Coarse-Grained Models of Bottlebrush Polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156 (1), 14903. 10.1063/5.0076507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Thapar V.; Choe Y.; Padilla Salas L. A.; Ramírez-Hernández A.; De Pablo J. J.; Hur S. M. Coarse-Grained Simulation of Bottlebrush: From Single-Chain Properties to Self-Assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11 (9), 1167–1173. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubimov I.; Wessels M. G.; Jayaraman A. Molecular Dynamics Simulation and PRISM Theory Study of Assembly in Solutions of Amphiphilic Bottlebrush Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (19), 7586–7599. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels M. G.; Jayaraman A. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study of Linear, Bottlebrush, and Star-like Amphiphilic Block Polymer Assembly in Solution. Soft Matter 2019, 15 (19), 3987–3998. 10.1039/C9SM00375D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumus B.; Herrera-Alonso M.; Ramírez-Hernández A. Kinetically-Arrested Single-Polymer Nanostructures from Amphiphilic Mikto-Grafted Bottlebrushes in Solution: A Simulation Study. Soft Matter 2020, 16 (21), 4969–4979. 10.1039/D0SM00771D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Wang X.; Ji Y.; Qiang X.; He L.; Li S. Bottlebrush Block Polymers in Solutions: Self-Assembled Microstructures and Interactions with Lipid Membranes. Polymer (Guildf) 2018, 140, 304–314. 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paturej J.; Sheiko S. S.; Panyukov S.; Rubinstein M. Molecular Structure of Bottlebrush Polymers in Melts. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2 (11), e1601478 10.1126/sciadv.1601478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi M.; Faust L.; Wilhelm M. Comb and Bottlebrush Polymers with Superior Rheological and Mechanical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31 (26), 1806484. 10.1002/adma.201806484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Tang M.; Liang S.; Zhang M.; Biesold G. M.; He Y.; Hao S. M.; Choi W.; Liu Y.; Peng J.; Lin Z. Bottlebrush Polymers: From Controlled Synthesis, Self-Assembly, Properties to Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 116, 101387. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2021.101387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.; Bockstaller M. R.; Matyjaszewski K. Brush-Modified Materials: Control of Molecular Architecture, Assembly Behavior, Properties and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 100, 101180. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.101180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verduzco R.; Li X.; Pesek S. L.; Stein G. E. Structure, Function, Self-Assembly, and Applications of Bottlebrush Copolymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44 (8), 2405–2420. 10.1039/C4CS00329B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G.; Cho S.; Clark C.; Verkhoturov S. V.; Eller M. J.; Li A.; Pavía-Jiménez A.; Schweikert E. A.; Thackeray J. W.; Trefonas P.; Wooley K. L. Nanoscopic Cylindrical Dual Concentric and Lengthwise Block Brush Terpolymers as Covalent Preassembled High-Resolution and High-Sensitivity Negative-Tone Photoresist Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (11), 4203–4206. 10.1021/ja3126382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L. C.; Gadelrab K. R.; Kawamoto K.; Yager K. G.; Johnson J. A.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A. Templated Self-Assembly of a PS- Branch-PDMS Bottlebrush Copolymer. Nano Lett. 2018, 18 (7), 4360–4369. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Liu R.; Su T.; Huang H.; Kawamoto K.; Liang R.; Liu B.; Zhong M.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A.; Johnson J. A. Emergence of Layered Nanoscale Mesh Networks through Intrinsic Molecular Confinement Self-Assembly. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18 (3), 273–280. 10.1038/s41565-022-01293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto K.; Zhong M.; Gadelrab K. R.; Cheng L. C.; Ross C. A.; Alexander-Katz A.; Johnson J. A. Graft-through Synthesis and Assembly of Janus Bottlebrush Polymers from A-Branch-B Diblock Macromonomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (36), 11501–11504. 10.1021/jacs.6b07670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani M.; Daniel W. F. M.; Everhart M. H.; Pandya A. A.; Liang H.; Matyjaszewski K.; Dobrynin A. V.; Sheiko S. S. Mimicking Biological Stress-Strain Behaviour with Synthetic Elastomers. Nature 2017, 549 (7673), 497–501. 10.1038/nature23673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani M.; Keith A. N.; Cong Y.; Liang H.; Rosenthal M.; Sztucki M.; Clair C.; Magonov S.; Ivanov D. A.; Dobrynin A. V.; Sheiko S. S. Chameleon-like Elastomers with Molecularly Encoded Strain-Adaptive Stiffening and Coloration. Science (1979) 2018, 359 (6383), 1509–1513. 10.1126/science.aar5308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banquy X.; Burdyńska J.; Lee D. W.; Matyjaszewski K.; Israelachvili J. Bioinspired Bottle-Brush Polymer Exhibits Low Friction and Amontons-like Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (17), 6199–6202. 10.1021/ja501770y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennington P.; Sánchez-Leija R. J.; Deng C.; Sharon D.; de Pablo J. J.; Patel S. N.; Nealey P. F. Mixed-Polarity Copolymers Based on Ethylene Oxide and Cyclic Carbonate: Insights into Li-Ion Solvation and Conductivity. Macromolecules 2023, 56 (11), 4244–4255. 10.1021/acs.macromol.3c00540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C.; Zhang B.; Bates F. S.; Lodge T. P. Self-Assembly of Partially Charged Diblock Copolymer-Homopolymer Ternary Blends. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (11), 4766–4775. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butzelaar A. J.; Röring P.; Mach T. P.; Hoffmann M.; Jeschull F.; Wilhelm M.; Winter M.; Brunklaus G.; Théato P. Styrene-Based Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Side-Chain Block Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes for High-Voltage Lithium-Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (33), 39257–39270. 10.1021/acsami.1c08841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G.; Martinez M. R.; Olszewski M.; Sheiko S. S.; Matyjaszewski K. Molecular Bottlebrushes as Novel Materials. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20 (1), 27–54. 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moad G.; Rizzardo E.. RAFT Polymerization: Methods, Synthesis and Applications: Volume 1 and 2; Wiley, 2021; Vol. 1–2, pp 1–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Chiefari J.; Chong Y. K.; Ercole F.; Krstina J.; Jeffery J.; Le T. P. T.; Mayadunne R. T. A.; Meijs G. F.; Moad C. L.; Moad G.; Rizzardo E.; Thang S. H. Living Free-Radical Polymerization by Reversible Addition - Fragmentation Chain Transfer: The RAFT Process. Macromolecules 1998, 31 (16), 5559–5562. 10.1021/ma9804951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Wang W.; Wang Y.; Zhu J.; Uhrig D.; Lu X.; Keum J. K.; Mays J. W.; Hong K. Fluorinated Bottlebrush Polymers Based on Poly(Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate): Synthesis and Characterization. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7 (3), 680–688. 10.1039/C5PY01514F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- György C.; Derry M. J.; Cornel E. J.; Armes S. P. Synthesis of Highly Transparent Diblock Copolymer Vesicles via RAFT Dispersion Polymerization of 2,2,2-Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate in n-Alkanes. Macromolecules 2021, 54 (3), 1159–1169. 10.1021/acs.macromol.0c02646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M.; Alghassab T. S.; Twyman L. J. Increased Oxygen Solubility in Aqueous Media Using PEG-Poly-2,2,2-Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate Copolymer Micelles and Their Potential Application as Volume Expanders and as an Artificial Blood Product. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1 (3), 708–713. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M. M.; Stöver H. D. H. Well-Defined Amphiphilic Thermosensitive Copolymers Based on Poly(Ethylene Glycol Monomethacrylate) and Methyl Methacrylate Prepared by Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2004, 37 (14), 5219–5227. 10.1021/ma030485m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Peng H.; Whittaker A. K. NMR Investigation of Effect of Dissolved Salts on the Thermoresponsive Behavior of Oligo(Ethylene Glycol)-Methacrylate-Based Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2014, 52 (16), 2375–2385. 10.1002/pola.27252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi S.; Tadano K.; Tanaka Y.; Shimidzu T.; Kutsumizu S.; Yano S. Dielectric relaxations of poly(fluoroalkyl methacrylates) and poly(fluoroalkyl .alpha.-fluoroacrylates). Macromolecules 1992, 25 (24), 6563–6567. 10.1021/ma00050a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar B.; Fielding L. A.; Cunningham V. J.; Ning Y.; Mykhaylyk O. O.; Fowler P. W.; Armes S. P. Determining the Effective Density and Stabilizer Layer Thickness of Sterically Stabilized Nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (14), 5160–5171. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Krevelen D. W.; Hoftyzer P. J. Prediction of Polymer Densities. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13 (5), 871–881. 10.1002/app.1969.070130506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Krevelen D. W.Properties of Polymers: Their Correlation with Chemical Structure; Their Numerical Estimation and Prediction from Additive Group Contributions, 4th ed.; Elsevier, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liang H.; Morgan B. J.; Xie G.; Martinez M. R.; Zhulina E. B.; Matyjaszewski K.; Sheiko S. S.; Dobrynin A. V. Universality of the Entanglement Plateau Modulus of Comb and Bottlebrush Polymer Melts. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (23), 10028–10039. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. A.; Glaser J.; Glotzer S. C. HOOMD-Blue: A Python Package for High-Performance Molecular Dynamics and Hard Particle Monte Carlo Simulations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 173, 109363. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2019.109363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.