SUMMARY

Over recent decades, the global burden of fungal disease has expanded dramatically. It is estimated that fungal disease kills approximately 1.5 million individuals annually; however, the true worldwide burden of fungal infection is thought to be higher due to existing gaps in diagnostics and clinical understanding of mycotic disease. The development of resistance to antifungals across diverse pathogenic fungal genera is an increasingly common and devastating phenomenon due to the dearth of available antifungal classes. These factors necessitate a coordinated response by researchers, clinicians, public health agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry to develop new antifungal strategies, as the burden of fungal disease continues to grow. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the new antifungal therapeutics currently in clinical trials, highlighting their spectra of activity and progress toward clinical implementation. We also profile up-and-coming intracellular proteins and pathways primed for the development of novel antifungals targeting their activity. Ultimately, we aim to emphasize the importance of increased investment into antifungal therapeutics in the current continually evolving landscape of infectious disease.

KEYWORDS: antifungal, clinical therapeutics, fungal pathogen, drug resistance mechanisms, drug development, clinical trials, Candida, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus

INTRODUCTION

Fungal infections represent a pressing yet neglected threat to public health. Broadly, fungal disease affects approximately a billion people worldwide through pathologies ranging from allergic syndrome, to local mucocutaneous infection, to life-threatening systemic disease (1, 2). Global socio-economic and environmental changes, in addition to the increased prevalence of immunocompromised individuals, have resulted in a growing population at risk for fungal infection (1, 3). This coupled with clinical reliance on just four classes of systemically acting antifungals and the continuous evolution of antifungal resistance to these drugs necessitates a prompt and sustained response to tackle these deadly pathogens (2). Fortunately, recent calls to action, including the development of the World Health Organization’s first Fungal Priority Pathogens list, have driven research and policy interventions to address fungal disease (2, 4, 5). Included on this list in the “critical priority” category are two Candida species, Candida albicans and Candida auris, as well as Aspergillus fumigatus and Cryptococcus neoformans. Critical importance was assigned to these organisms due to their rates of antifungal resistance, mortality, incidence, sequelae, diagnostic access, and treatment viability and affordability.

Of the key opportunistic invaders that are of gravest concern, Candida species are among the most prevalent human fungal pathogens, partly due to their global distribution and the fact that they are members of the human microbiota (5, 6). C. albicans is the leading cause of systemic fungal infections in North America (6), while C. auris is associated with outbreaks and demonstrates striking antifungal resistance patterns, namely, to the azoles, with cases of pan-resistance to the azoles, echinocandins, polyenes, and flucytosine reported in the clinic (7–9). The ubiquitous environmental mold A. fumigatus is linked to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and can present as a comorbidity of respiratory viral infections including COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza (5, 10, 11). The prevalence of azole resistance in A. fumigatus is increasing due to the widespread use of azoles in agriculture, which is linked to concerning increases in mortality, as azoles are the mainstay therapy for aspergillosis (5). C. neoformans is a leading cause of infection-related mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS (12, 13). It is particularly detrimental in low-resource regions where access to antiretroviral drugs and first-line antifungals is limited, resulting in mortality rates greater than 50% (14).

Accompanying these critically important pathogens, dimorphic fungi including Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, and Paracoccidioides represent a growing threat to public health, as they are capable of causing infection in healthy hosts (15, 16). Although believed to be restricted to distinct ecological niches, climate, environmental, and behavioral changes all pose a danger for the altered distribution of these fungi, broadening the susceptible population (17). Pathogenic molds including Mucorales, Fusarium, Scedosporium, and Lomentospora also pose an under-appreciated risk to the world’s growing immunocompromised population (18). Over recent years, clinical understanding of these pathogens has improved through advancements in diagnostics, sequence databases, and taxonomic overhaul. While data have been collected to outline the susceptibility of these genera to clinically available antifungal drugs, definitive clinical breakpoints delineating susceptibility versus resistance are missing, complicating treatment guidelines as well as our understanding of what constitutes resistance in these organisms (19, 20).

The dearth of antifungal therapeutic strategies makes the threat of resistance increasingly dire. Our current armamentarium of antifungal drugs could be improved by a greater emphasis on rapid fungicidal activity, broad-spectrum efficacy, and improved patient tolerability (21). Fortunately, the development and expansion of structurally-diverse compound collections, combined with advances in structure-guided drug design and a growing number of functional genomic resources across the fungal kingdom, have allowed for more efficient discovery and characterization of candidate antifungals (22). Currently, there are a number of antifungal therapeutics in pre-clinical and clinical development that show promise to address key challenges facing our existing antifungal arsenal. These include both new members of existing antifungal drug classes, as well as novel molecules targeting previously unexploited target pathways, and immunotherapies. This review will present an up-to-date overview of the antifungal development pipeline, new therapies currently in pre-clinical or active clinical development, and promising antifungal targets that warrant further exploration.

CLINICALLY AVAILABLE ANTIFUNGALS

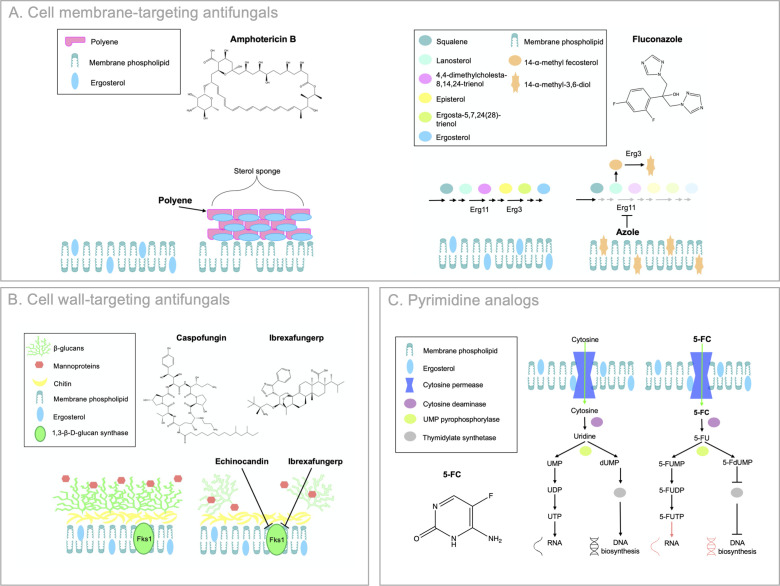

For invasive systemic fungal infections, there exist only four major classes of antifungal agents [polyenes, azoles, echinocandins, and the pyrimidine analog 5-flucytosine (5-FC)], with a fifth class (the triterpenoid ibrexafungerp) in advanced-stage clinical trials. The polyenes were first developed in the 1950s and include nystatin and amphotericin B. These fungicidal natural products exert broad-spectrum activity against most clinically relevant fungal genera (Fig. 1). For decades, the prevailing theory was that these molecules elicited their toxic effects by intercalating into ergosterol-containing membranes to form membrane-spanning channels that cause leakage of cellular components and, ultimately, cell death. However, recent detailed structural and biophysical studies highlighted that polyenes act more like an “ergosterol sponge” forming large extramembranous aggregates that extract the essential membrane-lipid ergosterol from the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A) (23, 24). The polyene class remains the most potent and broad-spectrum antifungal, although it is disfavored due to poor oral bioavailability and significant host toxicities (21). Notably, recent additions of lipid formulations of amphotericin, such as amphotericin B lipid complex and AmBisome, and fungal-specific structural derivatives of amphotericin have been successful at reducing host toxicity (21). Once the azoles were introduced into the clinic in the 1980s, they quickly became the gold standard for the treatment of invasive mycoses (25). These synthetic molecules, composed of triazole or imidazole moieties, block the biosynthesis of ergosterol by inhibiting lanosterol 14-α-demethylase (encoded by ERG11), causing the accumulation of a toxic sterol, 14-α-methyl-3,6-diol (Fig. 2A) (25, 26). Although azoles possess favorable safety and oral bioavailability profiles, the fungistatic activity of most azoles against Candida and Cryptococcus spp., coupled with the widespread emergence of resistance, threatens their clinical lifespan (Fig. 1) (27, 28). The echinocandins, developed in the early 2000s, are semi-synthetic natural product derivatives that inhibit 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase (encoded by FKS1), a glucosyltransferase enzyme necessary for the synthesis of an essential component of the fungal cell wall—a structure completely absent in mammalian cells (Fig. 2B) (29). Despite being clinically ineffective against Cryptococcus spp. (Fig. 1), this class has a favorable safety profile, making it an appealing choice as a first-line treatment for invasive candidiasis (3, 30). Finally, the pyrimidine analog 5-fluorocytosine was first approved for use in the 1960s; however, the rapid onset of resistance prevents its use as a monotherapy. Upon administration, 5-fluorocytosine is converted by a fungal-specific cytosine deaminase to 5-fluorouracil, a toxic compound that interferes with DNA and RNA metabolism (Fig. 2C). When used in combination with amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine offers an effective treatment for cryptococcosis and other rare invasive mycoses (Fig. 1) (25).

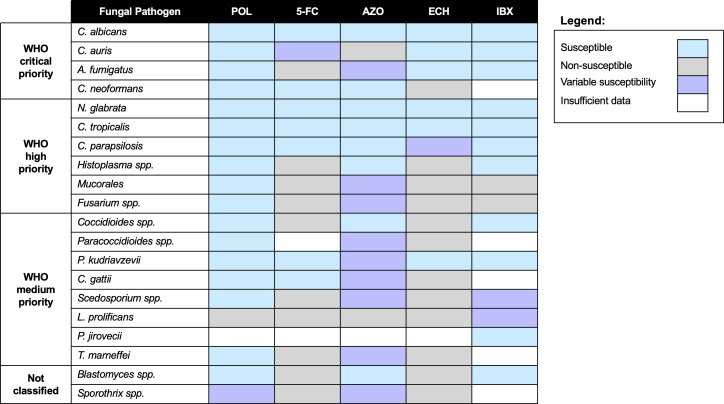

Fig 1.

Antifungal susceptibility patterns of fungal pathogens highlighted on the WHO fungal priority pathogen list. Fungal pathogens are categorized by the WHO fungal priority pathogen list, ranging from critical priority to not classified. Broad susceptibility of each fungal species/genus to polyenes (POL), 5-FC, azoles (AZO), echinocandins (ECH), and ibrexafungerp (IBX) is defined as susceptible (blue), non-susceptible (gray), variably susceptible based on strain or individual drug properties (purple), or undefined (white) due to insufficient data.

Fig 2.

Mechanisms of action of current clinically available antifungals. Cell membrane-targeting antifungals are depicted in (A). Polyenes act as fungicidal “sterol sponges” by forming extramembranous aggregates that extract ergosterol from lipid bilayers at the cell membrane. Amphotericin B (pictured) is an example of a polyene. Azoles exert fungistatic activity by inhibiting lanosterol 14-α-demethylase (Erg11), which blocks ergosterol biosynthesis and causes the accumulation of toxic sterol intermediates, including 14-ɑ-methyl-3,6-diol produced by Erg3. Fluconazole (pictured) is an example of an azole. Cell wall-targeting antifungals are depicted in (B). Echinocandins prevent the synthesis of (1,3)-β-D-glucan, by inhibiting the (1,3)-β-D-glucan synthase (Fks1), resulting in a loss of cell wall integrity and severe cell wall stress. Caspofungin (pictured) is an example of an echinocandin. Ibrexafungerp inhibits Fks1 by a divergent mechanism to the echinocandins. The pyrimidine analog 5-FC is depicted in (C). 5-FC is imported (green arrows) by cytosine permease where it interferes with RNA and DNA synthesis following conversion to 5-fluorouridine (5-FU) by cytosine deaminase. 5-FU is converted by uridine monophosphate (UMP) pyrophosphorylase to 5-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate (5-FdUMP), which inhibits thymidylate synthesis and downstream DNA biosynthesis. 5-FU is also converted by uridine UMP pyrophosphorylase to 5-FU monophosphate (5-FUMP), 5-FU diphosphate (5-FUDP), and finally 5-FU triphosphate (5-FUTP), which incorporates into RNA and interferes with translation. Adapted from reference (24).

The most recent addition to the antifungal repertoire is the first-in-class triterpenoid, ibrexafungerp, which is a fungicidal semi-synthetic derivative of enfumafungin (31, 32). Although it has the same target as the echinocandins, binding 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, some key differences include its oral bioavailability and chemical structure (Fig. 2B). Ibrexafungerp’s binding site also appears to be partially divergent from that of the echinocandins, allowing it to maintain activity against echinocandin-resistant Candida isolates (33, 34). Ibrexafungerp is currently only approved as an oral agent for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis; however, it is in several advanced-stage clinical trials for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, as well as invasive aspergillosis in combination with voriconazole (31).

ANTIFUNGAL THERAPEUTICS IN CLINICAL DEVELOPMENT

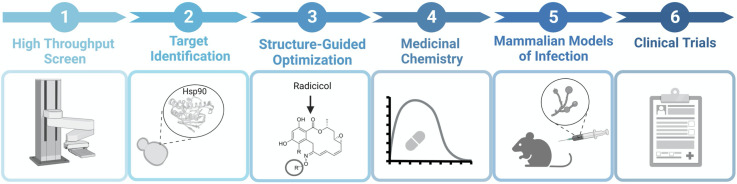

Although the development of new antifungals remains a considerable challenge, numerous approaches in the drug discovery and development pipeline seek to overcome these obstacles. These include both target-based drug development and screening of existing chemical matter, both natural products and synthetic molecules, for novel antifungal activity (Fig. 3) (21, 35). Fortunately, there are several antifungal agents in different phases of clinical trials that hold considerable promise for downstream approval and implementation.

Fig 3.

Antifungal drug development timeline. Drug development can begin with a high-throughput chemical screen of a structurally-diverse chemical library (1). This is followed by the identification of the drug target through various, biochemical, genetic, and genomic approaches (2). To attain fungal selectivity, structure-guided optimization is conducted (3). Next, medicinal chemistry modifications to core scaffolds can be made to obtain optimal pharmacokinetic properties (4). Conducting mammalian models of infection (5) to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the drug is critical before reaching clinical trials (6). The figure was generated using BioRender.

Cell wall-targeting molecules

Fosmanogepix

Fosmanogepix (APX001, previously E1211) is an inhibitor of the essential fungal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored wall transfer protein 1 (Gwt1), which is highly conserved across the fungal kingdom (Fig. 4) (36, 37). This water-soluble phosphate prodrug is the first in the novel “gepix” class of antifungals (Table 1). Upon oral or intravenous administration, fosmanogepix is metabolized by systemic alkaline phosphatases to its active moiety, manogepix (APX001A, previously E1210) (37). While manogepix inhibits Gwt1 activity, blocking inositol acylation of GPI early in the GPI biosynthesis pathway, it does not inhibit the function of the closest human Gwt1 ortholog, PigW (38). Experimental evolutionary studies in Candida spp. revealed that single-nucleotide polymorphisms leading to substitutions in the transmembrane helices of Gwt1 in C. albicans (V162A) and Nakaseomyces glabrata (formerly Candida glabrata; V163A) confer resistance to manogepix, highlighting the importance of the transmembrane region of Gwt1 for manogepix binding (36).

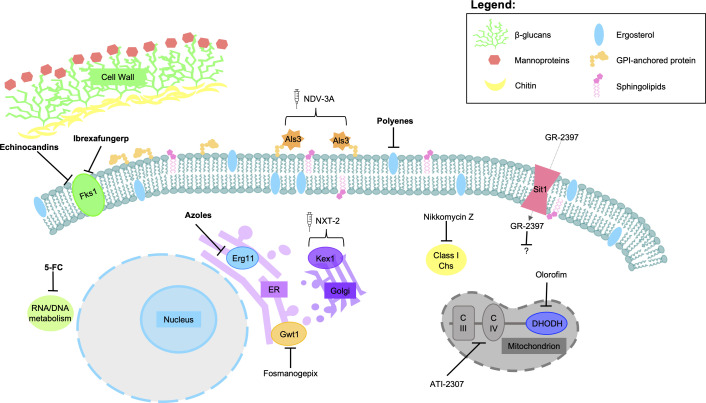

Fig 4.

Schematic of antifungal therapeutics and their mode of action. Antifungal drugs or drug classes currently approved for clinical use are in bold, while those in various stages of development are reported in plain text. Arrows with flat bases denote inhibition while brackets are used to denote proteins used in antifungal vaccinations. Generic names for fungal targets were used for consistency as not all therapies are active against one specific species. Adapted from reference (39).

TABLE 1.

Antifungal therapeutics in development

| Class | Novel antifungal agent | Mode of action | Spectrum of activity | Advantages | Stage of development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPI inhibitor | Fosmanogepix (APX001)

|

Inhibits the GPI-anchored cell wall transfer protein 1 (Gwt1) | C. albicans, N. glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, C. auris, Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp., Coccidioides spp., Rhizopus arrhizus | Active against resistant C. auris and C. albicans strains | Phase III trial |

| Nucleoside peptide natural product | Nikkomycin Z

|

Inhibits fungal type 1 chitin synthases | C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. auris, C. neoformans, Coccidioides spp., Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Sporothrix globosa | Synergizes with echinocandins and itraconazole against C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. neoformans | Phase I/II trial |

| Orotomide | Olorofim (F901318)

|

Inhibits the pyrimidine biosynthesis enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) | Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Fusarium spp., Trichophyton spp., Coccidioides spp., B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum, Lomentospora prolificans, Pseudallescheria boydii, Scedosporium apiospermum, Sporothrix schenckii, Microsporum gypseum | Active against resistant molds | Phase III trial |

| Natural product siderophore-like molecule | GR-2397 (formerly ASP2397 and VL-2397)

|

Mechanism of action unknown, uptake is mediated through Sit1 transporter | Aspergillus spp., N. glabrata, C. neoformans, Fusarium solani, Candida kefyr, and Trichosporon asahii | Active against azole-resistant Aspergillus strains | Phase II trial |

| Arylamidine | ATI-2307 (formerly T-2307)

|

Inhibits the enzymatic activity of mitochondrial complexes III and IV, suppressing ATP production | Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., Aspergillus spp., F. solani, Malassezia furfur | Active against all critical priority pathogens with comparable in vitro bioactivity to conventional antifungals | Phase I trial |

| Tetrazole | Oteseconazole (VT-1161)

|

Inhibits lanosterol 14-α-demethylase, disrupting ergosterol biosynthesis | C. neoformans, Candida spp., Coccidioides immitis/posadasii, and Trichophyton spp. | More specific to fungal Cyp51. Active against fluconazole- and echinocandin-resistant N. glabrata | Phase III trial |

| Tetrazole | VT-1598

|

Inhibits lanosterol 14-α-demethylase, disrupting ergosterol biosynthesis | C. neoformans spp., Candida spp., Aspergillus spp, Coccidioides spp., H. capsulatum, R. arrhizus, and B. dermatitidis | More specific to fungal Cyp51 | Phase I trial |

| Polyene analog | BSG005

|

Forms extramembranous aggregates that extract ergosterol from fungal cell membranes | Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., Cryptococcus spp., Mucor spp., and Pneumocystis spp. | Fungicidal activity against resistant Aspergillus and Candida isolates. Less nephrotoxicity than amphotericin B | Phase I trial |

| Polyene | Encochleated amphotericin B (CAmB)

|

Forms extramembranous aggregates that extract ergosterol from fungal cell membranes | Candida spp., C. neoformans, A. fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus terreus, Histoplasma spp., Coccidioides spp., Fusarium spp., Paracoccidioides, Blastomyces spp., Scedosporium spp. | Enhances amphotericin B bioavailability | Phase III trial |

| Polyene | AM-2–19

|

Forms extramembranous aggregates that selectively extract ergosterol from fungal cell membranes | Aspergillus spp. (including highly resistant amphotericin B strains), Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., Coccidioides spp., and H. capsulatum | Does not bind to cholesterol and is renal-sparing | In vivo studies |

| Echinocandin | Rezafungin

|

Inhibits the enzyme β−1,3-D-glucan, disrupting fungal cell wall biosynthesis | Candida spp. and some Aspergillus spp. | Increased solubility, stability, and half-life of the echinocandin drug class | Clinically approved |

| Vaccine | NVD-3A | Inhibits Als3-mediated virulence traits. Activates and increases innate phagocytic effectors | Candida spp. | Cost-effective means of prophylactic protection | Phase II trial |

| Vaccine | NXT-2 | Generates anti-NXT-2 antibodies that bind to fungal cells and facilitate opsonophagocytic killing | Pneumocystis jirovecii, A. fumigatus, C. albicans, and C. neoformans | Cost-effective means of broad-spectrum prophylactic protection | Phase I trial |

Manogepix demonstrates promising in vitro antifungal activity against pathogenic yeasts, including C. neoformans, Aspergillus species (A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. terreus, and A. flavus), and numerous Candida species (C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. auris) as well as N. glabrata (40–42). Interestingly, Pichia kudriavzevii (formerly Candida krusei) demonstrates intrinsic resistance to manogepix (42). Mouse models of invasive candidiasis with azole-susceptible and -resistant C. albicans or C. auris demonstrated decreases in fungal burden and improved survival when animals were given manogepix compared to untreated controls, with the benefits comparable or superior to established antifungal regimens (43, 44). Furthermore, treatment with fosmanogepix or manogepix alone was able to ameliorate infectious burdens in mouse models of pulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary mucormycosis (45), and disseminated fusariosis (43). Additionally, successful treatment with fosmanogepix of a human patient infected systemically with azole-recalcitrant Aspergillus calidoustus provided additional evidence that fosmanogepix is an auspicious strategy for the treatment of diverse fungal infections. Interestingly, structure activity relationship investigations undertaken at Amplyx Pharmaceuticals produced several analogs of manogepix that demonstrated up to 32-fold increased activity against C. neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, while maintaining similar toxicity and pharmacokinetic properties to manogepix (46, 47). This highlights not only the promise for the advancement of fosmanogepix through clinical development but also the promise of closely related Gwt1 inhibitors as treatment options for fungal infections that may not respond as well to fosmanogepix itself.

As fosmanogepix demonstrated excellent performance throughout preliminary studies in vitro, as well as in mouse models of fungal infection, it has been advanced through a series of clinical trials. A preliminary phase 1b investigation (NCT03333005) revealed that fosmanogepix was safe and well tolerated in acute myeloid leukemia patients with excellent intravenous and oral elimination half-lives of 60.9 and 47.4 hours, respectively (48). NCT04148287 (Pfizer) was an open-label phase II study used to determine the safety and efficacy of fosmanogepix for invasive C. auris infection (49). The study determined that fosmanogepix was safe and well tolerated by patients, demonstrating an 88.9% survival rate following the end of the study date, with all deaths considered unrelated to drug treatment (49). An additional phase II trial, NCT04240886 (Pfizer), began in 2020 to evaluate the safety and efficacy of fosmanogepix for the treatment of invasive mold infections caused by Aspergillus spp. and other molds. It was terminated in 2022 to prioritize a randomized comparative phase III trial in the same indication, which, however, reported lower all-cause mortality than the expected rate for an antifungal efficacy study (50). Finally, another phase III trial, NCT05421858 (Pfizer), has been scheduled for 2023 to determine fosmanogepix’s efficacy in adults with candidemia or invasive candidiasis as administered intravenously followed by an oral treatment course, compared to that of intravenous caspofungin followed by oral fluconazole. The results of this study are expected in 2026 (51).

Nikkomycin Z

Nikkomycin Z was initially identified in 1976 from a Streptomyces tendae culture supernatant (52). This nucleoside peptide natural product inhibits fungal growth through the inhibition of fungal type 1 chitin synthases (52, 53). Structurally similar to UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-N-GlcNAc), which is converted by chitin synthase into growing chitin polymers, nikkomycin Z competitively interacts with the binding site of UDP-N-GlcNAc and facilitates rearrangements of the chitin synthase active site (Table 1; Fig. 4) (54, 55). The inhibition of β-glucan production by the echinocandins commonly results in compensatory upregulation of chitin at the cell wall; therefore, chitin synthase inhibitors including nikkomycin Z display synergy with the echinocandins (56, 57).

Since its discovery, nikkomycin Z has been investigated for its bioactivity against diverse organisms, with some of the most promising data arising from studies with dimorphic, endemic fungi (58–62). When tested against opportunistic yeasts and molds, nikkomycin Z inhibits C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. auris, and C. neoformans growth at a wide range of concentrations and synergizes with itraconazole against C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. neoformans (57, 59, 63, 64). Most notably, nikkomycin Z is active against diverse endemic fungal pathogens including Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Coccidioides species (C. immitis, C. posadasii), which are particularly susceptible to nikkomycin Z (58, 65, 66). Mouse models of meningocerebral, pulmonary, and disseminated coccidioidomycosis demonstrated that nikkomycin Z improves the survival of infected animals and reduces fungal burden (58, 65, 67). A small-scale study on dogs with naturally acquired respiratory coccidioidomycosis showed that nikkomycin Z is well tolerated and improves disease status in seven of nine animals that finished the treatment course (68).

Clinical trials have been attempted with nikkomycin Z for the treatment of Coccidioides infection; however, lack of funding and challenges associated with participant recruitment have hindered the progress of this compound through the developmental pipeline. A phase I/II study, NCT00614666 (University of Arizona), commenced in 2007 with the aim of testing pharmacokinetics, safety, and preliminary effectiveness of nikkomycin Z against Coccidioides pneumonia, which, however, was prematurely terminated in 2009. Currently, Valley Fever Solutions, Inc. is working on scaling up syntheses of nikkomycin Z to accommodate clinical trials for coccidioidomycosis, as well as other fungal infections (69).

Intracellular-acting molecules

Olorofim

Olorofim, formerly F901318, is a synthetic molecule whose scaffold was identified from a large-scale screen against Aspergillus spp. (Table 1) (70). Medicinal chemistry efforts developed olorofim to optimize potency and pharmacokinetics, and a combination of genetic and biochemical approaches was used to determine its mode of action (70). DHODH is an essential mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of dihydroorotate to orotate during pyrimidine biosynthesis and is the proximal target of olorofim (Fig. 4). Olorofim selectively inhibits the A. fumigatus enzyme (PyrE) over human DHODH and is hypothesized to compete with DHODH’s cofactor, coenzyme Q, at the quinone channel (70). In A. fumigatus, resistance to olorofim can arise as a result of mutations to the drug target, PyrE, similar to how mutations in the proximal target of other conventional antifungals can result in resistance (3, 71). Experimental evolution in A. fumigatus uncovered that resistance to olorofim arises at a slower frequency than that observed with itraconazole, however more rapidly than resistance to voriconazole (71).

The spectrum of activity of olorofim is sequence-driven (70). Phylogenetic analysis of DHODH across the fungal kingdom revealed that species susceptible to in vitro growth inhibition by olorofim, including other Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Fusarium spp., Trichophyton spp., B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum, C. immitis, C. posadasii, Scedosporium apiospermum, and Sporothrix schenckii, clustered together (70, 72, 73). Olorofim is not active against Candida spp.; however, the efficacy of olorofim against Aspergillus spp., as well as other opportunistic molds associated with high levels of antifungal resistance, makes it a promising therapeutic that warrants concerted efforts toward progression into the clinic (5). Olorofim demonstrates excellent in vivo efficacy in mouse models of aspergillosis (74). Thus, clinical trials have been initiated to assess the efficacy of olorofim in human fungal infection. A phase IIb trial NCT03583164 (F2G Biotech GmbH) is currently underway to evaluate its efficacy against invasive infections by Aspergillus spp. and other resistant molds in patients lacking suitable alternative treatment options. A New Drug Application for olorofim was filed in 2022 with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration based on preliminary data from this study; however, additional analysis and data supporting olorofim’s efficacy were requested before an approval decision can be made (75, 76). Currently, a phase III study (NCT05101187) is currently recruiting to determine the safety and efficacy of olorofim compared to AmBisome (liposomal amphotericin B) for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis (77).

GR-2397

GR-2397 (formerly ASP2397 and VL-2397) is a molecule produced by Acremonium persicinum that is structurally related to the siderophore, ferrichrome (Table 1) (78). It was first characterized as a fungicidal inhibitor of A. fumigatus in a silkworm model of infection during a screen of natural products, with comparable activity to voriconazole (79). Mutagenesis experiments in A. fumigatus revealed that loss of the siderophore iron transporter 1 (Sit1) resulted in a reduction in GR-2397 susceptibility, indicating that Sit1-mediated transport is important for compound uptake (Fig. 4) (80, 81). The absence of a human Sit1 ortholog helps to explain why GR-2397 does not demonstrate significant toxicity against human cells (82). A. fumigatus susceptibility to the molecule is dependent on low iron conditions, with excess iron resulting in increased resistance to GR-2397 (46). Conversely, genetic alterations causing derepression of the siderophore system or increased iron starvation result in hypersensitivity to GR-2397 (46). Although GR-2397 has been shown to chelate aluminum, the cellular import of this metal is not critical for the bioactivity of this molecule (46). Thus, a more precise delineation of the mechanism of action of GR-2397 is required to determine how it exerts its antifungal activity.

To date, in vitro evaluations of GR-2397 efficacy revealed potent bioactivity against Aspergillus spp., N. glabrata, C. neoformans, and other fungal pathogens (80). Mouse models of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, as well as disseminated aspergillosis, demonstrated that GR-2309 improved overall mouse survival as well as disease burden over the treatment course (79, 80). As such, clinical trials have been initiated to evaluate the potential of this molecule against Aspergillus infection. A phase II study, NCT03327727, was initiated by Vical Inc. in 2018 to assess GR-2397 as a first-line invasive aspergillosis treatment for adult patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, or allogenic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, following the success of a phase I trial confirming the safety and tolerability of the drug (82). This study was terminated as Vical Inc. abandoned further development of GR-2397; however, it has since been acquired by Gravitas Therapeutics, which aims to advance its development for the treatment of aspergillosis (83).

ATI-2307

The arylamidine ATI-2307 (formerly T-2307) is structurally similar to other aromatic diamidines like pentamidine and was first evaluated by Toyama Chemical Co. for its broad-spectrum antifungal activity (Table 1) (84). Early investigations into its mechanism of action revealed that ATI-2307 results in a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in C. albicans and the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, while exerting negligible effects on isolated rat liver mitochondria (85). ATI-2307 is internalized by yeast through a high-affinity spermine/spermidine carrier thought to be regulated by Agp2 (86) and subsequently inhibits the enzymatic activity of mitochondrial complexes III and IV, suppressing ATP production (Fig. 4) (87).

In vitro data highlighted that ATI-2307 inhibits the growth of numerous fungal pathogens, including Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Aspergillus spp. (84, 88, 89). Multiple models of invasive Candida infection demonstrated that ATI-2307 treatment is efficacious in improving survival and reducing fungal burden when mice were challenged with C. albicans, N. glabrata, or C. auris (84, 89–91). Similarly, in models of systemic C. neoformans infection or pulmonary cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii, ATI-2307 displayed favorable in vivo activity (84, 88, 92). Systemic A. fumigatus infection was also markedly improved by ATI-2307; however, the molecule is not as potent against Aspergillus spp. compared to yeasts in vivo (84). ATI-2307 has progressed through phase I clinical trials to evaluate the pharmacokinetics and tolerability of the molecule; however, the results have not yet been deposited in a publicly available database (85, 93). In 2019, ATI-2307 was acquired by Appili Therapeutics, a Canadian drug development company that indicated their intention to evaluate this molecule as a treatment for cryptococcal meningitis as well as refractory and resistant Candida infections (93). However, as of 2023, ATI-2307 does not appear in Appili’s current long-term pipeline, suggesting that the status of its continued investigation is uncertain (94).

Next-generation antifungals

Tetrazoles (oteseconazole/VT-1161, VT-1598)

First-generation azoles (i.e., miconazole and ketoconazole) and second-generation triazoles (i.e., itraconazole and voriconazole) are effective against a range of yeasts and molds but are also associated with off-target inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes. This is due to the high homology of a common heme-iron motif in both fungal CYP51 and human P450 proteins, where off-target binding can result in liver toxicity (95). Oteseconazole (also known as VT-1161), VT-1598, and VT-1129 are next-generation azoles developed by Mycovia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (previously Viamet Pharmaceuticals), where the 1-(1,2,4-triazole) metal-binding group has been replaced with a tetrazole (95, 96). Furthermore, to maintain fungal selectivity, the side chains of these inhibitors have been modified (Table 1) (96, 97).

Oteseconazole and VT-1598 have in vitro activity against C. neoformans and most Candida spp. (96). While VT-1598 has activity against Aspergillus spp., oteseconazole is not active alone against these pathogenic molds (98, 99). VT-1598 arguably has the broadest spectrum of activity with additional activity against Coccidioides spp., H. capsulatum, Rhizopus arrhizus, and B. dermatitidis (100). In terms of in vivo activity, oteseconazole demonstrated potent activity in mouse models of vulvovaginal candidiasis against fluconazole-sensitive and -resistant clinical isolates, whereas VT-1598 showed promising efficacy in murine models of central nervous system coccidioidomycosis (101–104). A phase I clinical trial of single VT-1598 doses in healthy adults resulted in no serious adverse effects among the 48 subjects (NCT04208321). Additional clinical trials revealed that oral oteseconazole has promising efficacy in a phase III study for the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VMT-VT-1161-CL-012). Specifically, oteseconazole was superior to fluconazole and placebo groups, with a significantly lower likelihood of achieving ≥1 culture-verified acute vulvovaginal candidiasis episode through week 50 (102), and has, therefore, been approved for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis treatment in the USA (105).

BSG005

Over the last 20 years, both semi-synthetic and genetically engineered polyene analogs have been generated to overcome the drug class’ nephrotoxicity and suboptimal pharmacokinetics (106, 107). One such example is a nystatin analog BSG005 (Table 1) (108). BSG005 is effective against all the critical priority fungal pathogens with a 20-fold increase in activity compared to nystatin (106). Importantly, a significant decrease in nephrotoxicity and an improved toxicological profile was observed for BSG005 when compared to amphotericin B (106, 108). BSG005 also displays fungicidal activity against azole- and echinocandin-resistant Aspergillus and Candida isolates (109). Finally, in a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis, treatment with BSG005 led to a decrease in renal fungal burden, more so than amphotericin B treatment (106). A phase I trial (NCT04921254) investigating the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of intravenous formulations of BSG005 commenced in August 2021 with 72 participants and is estimated to be completed in May 2023. Thus far, BSG005 displayed a low risk for the development of resistance, an extensive therapeutic window encompassing multidrug-resistant strains of Candida and Aspergillus, and no reported adverse cases of central nervous, respiratory, or cardiovascular effects (109). Biosergen AS, the Swedish biotechnological company spearheading these clinical trials, alongside SINTEF, has commenced developing nanoformulations of BSG005, including BSG005 Nano Oral, a pill intended for easy home follow-up treatments or prophylactic use, and BSG005 Nano Lung, an intravenous formulation specifically targeting the lungs. These nanoformulations are projected to enter clinical trials in 2024/2025 (109). BSG005 is regarded as a strong candidate for the gold standard treatment for invasive pathogenic fungal infections, potentially replacing azoles and echinocandins (110).

Encochleated AmB (CAmB)

Due to molecular characteristics such as amphiphilicity, structural asymmetry, and zwitterionic nature, amphotericin B displays poor permeability in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in bioavailability challenges with oral administration of the drug (111). Several drug delivery systems such as lipid conjugates, self-emulsifying drug delivery systems, solid lipid nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes have been investigated to enhance amphotericin B bioavailability; however, many have not surpassed in vitro studies (110, 112–114). Amphotericin B-loaded cochleates and emulsions offer promising approaches to improve drug efficacy. MAT2203, a novel encochleated amphotericin B formulation (CamB), was developed for oral administration by Matinas BioPharma (North Carolina, USA) (115). The cochleate is composed of solid phospholipid bilayer vesicles that are rolled up in sheets, encompassing amphotericin B molecules with the divalent cation precipitates calcium and phosphatidylserine (110). It is hypothesized that the cochleate is taken up by phagocytic cells and delivered to the cytoplasm of the target cell through membrane fusion, where amphotericin B is released in the presence of low intracellular calcium (18, 115). Alternatively, amphotericin B may be released after cochleate–lysosome fusion (18).

CamB has potent in vitro activity against most Candida spp., C. neoformans, A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus (18). Furthermore, animal studies showed extensive tissue penetration and distribution to target organs after a single dose of CamB; mouse models of disseminated candidiasis resulted in 100% survival for all administered doses (0.5 to 20 mg/kg/day) and a significant dose-dependent reduction in organ colonization (116). CamB has also been successful in reducing fungal burdens in mouse models of oropharyngeal candidiasis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and cryptococcal meningitis in combination with 5-FC (117, 118).

In a phase IA clinical trial (NCT04031833), 4 to 6 daily doses of CamB (up to 2.0 g/day) were safe and well tolerated, with only mild adverse effects observed at higher doses in HIV-positive patients (115). Furthermore, in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, CamB was well tolerated by all patients enrolled in a phase II clinical trial NCT02629419, with no reported renal, hepatic, or hematologic toxicity, reaching clinical efficacy in both esophageal and oropharyngeal candidiasis after 2 weeks of treatment with 200 or 400 mg twice-daily dosing (117, 118). Based on the above successes of phase I and II clinical trials, Matinas BioPharma plans to continue to test CamB in a phase III antifungal efficacy trial, NCT05541107, for cryptococcal meningitis. The results of this study are expected in 2025 (119).

AM-2-19

The sterol sponge mechanism of amphotericin B drives renal toxicity as the structurally similar sterol cholesterol is also susceptible to extraction by large extramembranous amphotericin B aggregates. Recently, a cholesterol-sparing structural derivative of amphotericin B was generated to overcome this liability. This approach was guided by high-resolution structures of amphotericin sponges in sterol-free and bound states, followed by selective tuning of sterol extraction kinetics (120). The resulting hybrid derivative, AM-2–19, paired a toxicity-eliminating C2 epimerization with a potency-promoting serinol side chain (Table 1) (120). AM-2-19 rapidly extracts ergosterol with potency that surpasses or matches amphotericin B (AmBisome), across a panel of pathogenic fungi, including Aspergillus spp. (including highly-resistant amphotericin B strains), Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., Coccidioides spp., and H. capsulatum (120). Furthermore, the addition of distearoyl-rac-glycerol-polyethylene glycol 2000 (DP2K) helped generate a stable and plasma-compatible aqueous formulation. AM-2-19_DP2K was proven to be renal-sparing in mice, with an observed dose-dependent decrease in fungal burden in disseminated and pulmonary models of aspergillosis. Additionally, improved survival was noted in candidiasis and mucormycosis mouse models of infection after AM-2-19_DP2K treatment (120). The development of AM-2-19 highlights the power of leveraging biochemical and biophysical insights to generate significant improvements to current antifungal classes. While still in its infancy, AM-2-19 has the potential to be a significant and ground-breaking addition to the antifungal arsenal pending further investigation and clinical trials.

Rezafungin

Currently, the echinocandins have poor oral absorption and stability, disfavoring oral, topical, or subcutaneous drug preparations of this class (121, 122). Rezafungin, formerly known as SP3025 and CD101 (Cidara Therapeutics, San Diego, CA), is a second-generation echinocandin with favorable pharmacokinetic properties due to structural modifications of the anidulafungin scaffold, including replacing the hemiaminal region with a modified choline anima ether (Table 1) (121, 122). While rezafungin still exerts antifungal activity by inhibiting the β-1,3-D-glucan synthase, the chemical modifications allow for increased stability, solubility, and half-life (122). This novel echinocandin displays activity against Candida spp. (including resistant strains of C. albicans), C. tropicalis, N. glabrata, and some Aspergillus spp., with limited activity against Cryptococcus (123). Furthermore, phase II clinical trials, where rezafungin efficacy was evaluated during a once-weekly I.V. formulation for candidemia and as a topical formulation for acute and recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, also yielded favorable results (NCT02733432; NCT02734862). In a phase III clinical trial, rezafungin was not inferior to caspofungin for the treatment of invasive candidiasis and candidemia, with no serious adverse events (124). As of 2023, rezafungin was approved by the FDA for the treatment of invasive candidiasis and candidemia (125). Future clinical trials are recruiting to investigate the efficacy of rezafungin in comparison to standard antimicrobials for the prevention of invasive fungal diseases in adults undergoing allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation (ReSPECT; NCT04368559) as well as the treatment of pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-infected adults (NCT05835479) (126).

Antifungal vaccines and immunotherapies

Despite the devastating impact pathogenic fungi have on human health, there are no pan-fungal or single-pathogen antifungal vaccines (127, 128). While antifungal vaccines and immunotherapies will not replace antifungal drugs, they can be among the most cost-effective means to offer protection against diverse infectious diseases (129). Currently, despite the extensive challenges with developing a successful antifungal vaccine, there are some candidates that show promise as a therapeutic.

NDV-3A

NDV-3A is an immunotherapeutic formulated with the N-terminus of the recombinant agglutinin-like sequence 3 protein (Als3), with an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant in phosphate-buffered saline (Fig. 4) (130). Als3 is an immunodominant C. albicans cell wall protein that is characterized by three domains: an N-terminal region, which is conserved among Als proteins; a central portion containing variable tandem repeats; and a serine-rich C-terminal region containing a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor (131, 132). Als3 is a critical mediator of diverse virulence traits required for the establishment of infection and disease, such as mediating adherence and invasion of human vascular endothelial and epithelial cells, biofilm formation, and iron acquisition (128, 130, 133). A C. albicans als3Δ/als3Δ mutant displayed a 90% reduction in endothelial and epithelial endocytosis compared to a wild-type strain, as well as a significant reduction in the number of hyphae associated with endothelial cells, with almost no host cell damage (134). Interestingly, homozygous deletion of ALS3 in C. albicans did not result in a loss of pathogenicity in in vivo mouse models. The mechanism of protection mediated by the NDV-3A vaccine is, thus, likely not solely due to the inhibition of Als3-mediated virulence traits but rather the activation and increase in innate phagocytic effectors at the site of infection (135).

NDV-3A demonstrated favorable pre-clinical activity in animal models of disseminated hematogenous and vaginal candidiasis (128). The vaccine was successful in preventing disseminated candidiasis in mice infected with C. auris or C. albicans (135). When NDV-3A vaccinated and control mice were infected with C. albicans via tail-vein injection 2 weeks after boost, renal fungal burden revealed a ~10-fold reduction in kidney fungal burden relative to unvaccinated mice (135). Furthermore, when coupled with complete or incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, a common water-in-oil emulsion with or without killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis, NDV-3A protected mice from other sources of disseminated infection caused by C. parapsilosis, N. glabrata, or P. kudriavzevii highlighting its activity against diverse fungal species (135). NDV-3A was also proven to be efficacious in mouse models of vulvovaginal candidiasis resulting in a 15-fold reduction in vaginal fungal burden compared to controls (136).

Following a successful phase I clinical trial, a phase Ib/IIa trial (NCT01926028) was conducted in women <40 years of age to evaluate the efficacy of NDV-3A vaccine against recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (128, 137). Most vaccinated patients had their first recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis at 94 days (median), in contrast to placebo patients who had their first recurrence at 53 (median) days post-vaccination (136). In another recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis phase II trial, one intramuscular dose of NDV-3A was safe, generating rapid and robust B and T cell responses, resulting in a significant increase in symptom-free patients 12 months after vaccination and a doubling in median time to first symptomatic episode (210 days vaccinated vs 105 days placebo) for patients aged <40 years (128). To date, no adverse effects of NDV-3A have been reported suggesting a promising antifungal vaccine.

NXT-2

Alarmingly, patients at risk for multiple pathogenic fungal infections have no viable cross-protective treatments. The NXT-2 vaccine builds on research that previously employed recombinant Kex1 proteins as vaccine candidates against Pneumocystis (PC.KEX1) and Aspergillus (AF.KEX1) (138–140). To generate a broad-spectrum antifungal vaccine, a pan-fungal protein, based on consensus amino acid sequences in the conserved KEX1 regions of multiple fungal pathogens, was generated and tested for efficacy using models of aspergillosis, candidiasis, and pneumocystis (Fig. 4) (140). The pan-fungal consensus sequence of KEX1 was generated through sequence identity and similarity of multisequence alignments of the peptide sequence from Pneumocystis jirovecii, A. fumigatus, C. albicans, and C. neoformans (140). This resulted in a 90-mer pan-fungal sequence that was used to generate the NXT-2 vaccine (140).

NXT-2 was highly immunogenic in non-human primates and mice, generating anti-NXT-2 antibodies that function by binding to fungal cells and facilitating opsonophagocytic killing (140). Seeing that kexin is primarily associated with the trans-Golgi network, the broad-spectrum activity of the NXT-2 vaccine and localization of anti-KEX1 and anti-NXT-2 antibodies on the surface of multiple fungal pathogens is surprising (140). Likely explanations include surface or transmembrane localization of kexin due to intracellular molecular trafficking through the cell wall, shedding of protein from dead or dying cells, or epitopes recognized by the protective antibodies present in a surface protein that shares sequence homology with the internal kexin peptidase (140). NXT-2 vaccination significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in severely immunosuppressed animal models (mouseand non-human primate) of pneumocystosis, aspergillosis, and candidiasis, compared to controls (140). Furthermore, immunization with NXT-2 inhibited C. albicans biofilm formation and reduced associated mortality, resulting in a greater than double the average survival time of immunosuppressed mice after lethal challenge with C. albicans (140). Excitingly, anti-NXT-2 polyclonal antibodies were shown to be cross-reactive with recombinant Kex1 homologs from other fungal pathogens, including C. neoformans and C. auris, broadening the number of pathogens from which NXT-2 may provide protection (140). Additional clinical research on the NXT-2 vaccine will address optimal vaccine formulations, dosing, and routes (130). As of 2023, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the U.S. National Institute of Health was contracted for process development and formulation of the NXT-2 pan-fungal vaccine.

Antifungal-specific T cell therapy

T cell-based immunotherapy has shown promise as a prophylactic or treatment measure to prevent invasive fungal infection in nosocomial settings, particularly following immunosuppressive procedures like solid organ transplants or allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) where invasive fungal disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality (141, 142). The T cell response is an essential component of the immune response to fungal invaders. CD4+ T cells facilitate the release of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of innate immune cells and work in concert with CD8+ T cells in antibody generation from B cells. CD8+ T cells also stimulate the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and can be induced to retain long-term immunological memory (141). Initial evaluations using adoptive transfer of A. fumigatus-specific donor T cell clones resulted in successful transfer of immunity to Aspergillus spp. in patients who had undergone HSCT, suggesting that T cell therapy may be an auspicious avenue to prevent infectious mortality in transplant patients (143). Subsequent studies have endeavored to develop facile generation methods for fungal-specific T cells on a clinical scale. Successful expansion of third-party donor-derived T cells has been completed to generate A. fumigatus-specific cell populations, which are well-tolerated by mice when tested in vivo (144). Pan-fungal T cell populations that target Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Scedosporium, and Lomentospora species as well as Mucorales were generated following stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells or hematopoietic progenitor cells with fungal lysates (144–147). Currently, two clinical trials are underway to evaluate the efficacy of fungal-specific T cell treatment in HSCT patients. The first (EudraCT Nr. 2013-002914-11) is a phase I/II trial designed to specifically evaluate the adoptive transfer of Aspergillus Th1 cells to treat HSCT patients with confirmed invasive aspergillosis (147). Another open-label phase I trial (NCT02779439) was completed to evaluate prophylactic multipathogen T cells targeting a variety of viral pathogens, as well as A. fumigatus (148). Following infusion, most patients demonstrated increased peripheral blood T cell counts within 30 days, which consisted primarily of antigen-experienced activated effector memory CD8+ T cells (148). Additionally, none of the patients evaluated required systemic antifungal treatment for a proven or likely fungal infection post-HSCT (148). Interestingly, a recent case report from Inam and colleagues (149) determined that an HSCT patient with an invasive Scedosporium aurantiacum infection was effectively treated with third-party fungal-specific T cells originally produced via stimulation with A. terreus and P. kudriavzevii. In addition to the clinical trials discussed, this case investigation highlights the feasibility and therapeutic promise of antifungal T cell therapy, as well as the cross-protectivity of fungal-specific T cells against naïve organisms (149).

EMERGING MOLECULAR SCAFFOLDS AND ANTIFUNGAL TARGETS

While our current antifungal arsenal targets either β-glucans in the cell wall or ergosterol in the cell membrane, significant efforts are underway to discover novel antifungal targets. In this section, we will highlight promising new targets and antifungal molecules that are currently in the pre-clinical phase of drug development.

Calcineurin

Calcineurin is the serine threonine-specific Ca2+-calmodulin-activated protein phosphatase that is highly conserved across eukaryotes (26, 150). It is a heterodimer composed of a regulatory B subunit [calcineurin B (CnB)] and catalytic subunit [calcineurin A (CnA)] (151). In mammalian T cells, calcineurin regulates the activity of transcription factors (such as nuclear factor of activated T cells) that are involved in immune interleukin-2 transcription and T cell activation (150). In fungal cells, calcineurin is a key mediator of many stress response signaling pathways that have important impacts on growth, drug resistance, and virulence in diverse pathogenic fungi (150–152). Calcineurin can be targeted by two widely used immunosuppressive agents: tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine A (CsA). Both these inhibitors are bioactive in C. neoformans, Candida spp., and A. fumigatus (153–155). However, exploiting FK506 and CsA for antifungal drug development has been limited by their immunosuppressive effects on the host. One approach to overcome these limitations includes synthesizing FK506 antagonists that are permeative to mammalian cells but not fungal cells (156). This results in the retention of antifungal selectivity of FK506, while minimizing the immunosuppressive activity exerted on the host when used in combination with the antagonists (156). This combination of antagonists with FK506 has shown promising preliminary results, with expected proof-of-principle studies in a mouse model of aspergillosis (156).

Recently, the crystal structures of the CnA and CnB subunits complexed with FK506 and the FK506-binding protein (FKBP12) from A. fumigatus, C. albicans, and C. neoformans were solved. While fungal calcineurin complexes are similar to the mammalian complex, a comparison of fungal and human FKBP12 (hFKBP12) revealed conformational differences in the 40s and 80s loops (157). This allowed for the development of a more fungal-selective, less immunosuppressive FK506 analog, APX879 (157). Comparatively, APX879 exhibited reduced immunosuppressive activity in a mouse cryptococcosis model, while retaining broad-spectrum antifungal activity against A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. neoformans, and other fungal pathogens (157). An additional FK506 analog, JH-FK-08, displayed promising in vivo results in a mouse cryptococcosis model, significantly reducing fungal burden and prolonging survival (158). These studies highlight the promise of developing a fungal-selective calcineurin inhibitor in large part due to the insights obtained from solving crystal structures.

Hsp90

Hsp90 is a highly conserved heat shock protein that uses the energy created by ATP binding and hydrolysis to fold and stabilize many client proteins, such as kinases and signal transducers (159). The appeal of targeting Hsp90 lies in its function as a core hub in many signal transduction cascades, thus serving as a key regulator of growth, drug resistance, stress response, and virulence in diverse fungal pathogens (159). Structurally unrelated natural product inhibitors of Hsp90, including geldanamycin and radicicol, displace ATP and block Hsp90 function. In a Galleria mellonella model of C. albicans infection, the combination of fluconazole with clinically- relevant Hsp90 inhibitors resulted in a profound therapeutic benefit (160). Unfortunately, due to the highly conserved nature of Hsp90, toxicity associated with Hsp90 inhibition limits the use of current inhibitors in mammalian models of fungal infection (159).

To help identify exploitable differences between fungal and human Hsp90, researchers solved the crystal structure of the C. albicans Hsp90 N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain alone and in complex with Hsp90 inhibitors. These structural studies identified increased conformational flexibility in C. albicans Hsp90 when bound to inhibitors, relative to human Hsp90 (161). This enabled the rational design of various compounds including CMLD013075, the first fungal-selective Hsp90 inhibitor, which showed >25-fold biochemical selectivity for C. albicans Hsp90, compared to the human homolog (Fig. 3) (161). CMLD013075 had low toxicity to mammalian cell lines and enhanced azole efficacy against resistant C. albicans isolates.

Similarly, the crystal structure of the C. neoformans N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain has been solved and has led to the continued development of additional fungal-selective inhibitors. Aminopyrazole-substituted resorcylate amides (like Compound 112) display improved potency and selectivity for C. neoformans Hsp90 compared to the human homolog (162). The next steps in the development of fungal-selective Hsp90 inhibitors include developing compounds with improved whole-cell activity against fungal pathogens and sufficient metabolic stability to allow for systemic administration in mammalian models of infection. (147)

Lipid biosynthesis

Evolutionary divergence of lipid metabolic pathways between fungi and humans, beyond the sterols, has yet to be fully exploited for antifungal development. Given the importance of fatty acid biosynthesis across all life forms, the fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex has emerged as an attractive antifungal target (163, 164). Although the FAS complex is conserved in humans, it has been suggested that fungal-selective FAS inhibitors can be identified (163). Specifically, two metabolites from Penicillium solitum, CT2108A and CT2108B, were discovered that selectively inhibit purified C. albicans FAS compared to the human complex, resulting in an attenuation in Candida spp. growth (163). Another study uncovered a small triazenyl indole FAS inhibitor, NPD6433, which was bioactive in vitro against Candida spp. (C. albicans, C. auris), N. glabrata, C. neoformans, and A. fumigatus. NPD6433 was shown to target the enoyl reductase (ER) domain of fungal Fas1, covalently inhibiting flavin mononucleotide-dependent NADPH oxidation (165). The mammalian FAS ER domain does not require flavin mononucleotide to facilitate NADPH oxidation, thus highlighting a fungal-selective mechanism of FAS inhibition by NPD6433. Unfortunately, NPD6433 displayed some non-specific toxicity against human cell lines in vitro, precluding it from being tested in systemic models of fungal disease (165).

In addition to the fatty acids, sphingolipids are key players in growth, morphogenesis, and virulence in pathogenic fungi (166). Inhibitors of sphingolipid biosynthesis have shown promise as putative antifungals, including the synthetic N′-(3-bromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene-2-methylbenzohydrazide (BHBM) and 3-bromo-N′-(3-bromo-4-hydroxybenzylidene) benzohydrazide (D0) (167, 168). Both molecules demonstrated strong in vitro potency against Cryptococcus spp. and improved host survival rates in mouse models of cryptococcosis and candidiasis (167). The development of the BHBM acylhydrazone scaffold continues to uncover related molecules with improved fungal selectivity, spectra, and potency (169, 170). While most enzymes required for de novo synthesis of sphingolipids have mammalian homologs, inositol phosphorylceramides (IPCs) and the essential IPC synthase enzyme (termed Ipc1 or Aur1) are not present in mammals (166, 168). Natural-product inhibitors of IPC synthase have been identified, including aureobasidin A, galbonolide A, and khafrefungin (168), with aureobasidin A demonstrating broad-spectrum growth inhibition against Candida spp., C. neoformans, and other fungal pathogens in vitro (171, 172). In vivo studies also demonstrated that this molecule is well tolerated and efficacious in a mouse model of candidiasis (172, 173). Furthermore, modification of aureobasidin A through borylation to functionalize its phenylalanine residues has generated derivatives with a wider spectrum of activity against Aspergillus and Trichophyton spp. (174). These findings prompt us to question why this molecule has not been pushed further through the drug development pipeline as exploiting the distinctions in fungal sphingolipid biosynthesis by targeting IPC synthase presents an auspicious path to expand the clinical repertoire antifungals.

Kinases

Due to their importance in fungal growth, proliferation, signaling, and stress responses, kinases are attractive drug targets despite their broad conservation. While no kinase inhibitors are currently approved to treat fungal infection, their future use as either single agents or potentiators of existing antifungals remains a possibility (21, 175–177). Foundational work in C. albicans has supported this ideal. For example, pharmacological inhibition of the protein kinase Pkc1 attenuates C. albicans virulence and sensitizes C. albicans to the azoles and echinocandins (177–179), while inhibition of the TOR protein kinase with the natural product beauvericin sensitizes C. albicans to the azoles and prevents the evolution of azole resistance (176). Additionally, a screen of human kinase inhibitors revealed a synthetic small molecule with single-agent and echinocandin-potentiating activities against C. albicans and C. auris, termed GW (175). This 2,3-aryl-pyrazolopyridine targets the C. albicans casein kinase Yck2, where it binds proximally to a glycine-rich loop in the protein’s ATP-binding pocket that is not conserved in the evolutionarily-related human CK1 family (175). Therefore, GW demonstrates fungal selectivity and low toxicity to human cells in vitro. In vivo testing has been delayed due to the metabolic liabilities of the GW scaffold; however, medicinal chemistry efforts are currently underway to generate equipotent, metabolically stable Yck2 inhibitors for progression to in vivo efficacy studies. In addition to inhibiting fungal growth, kinase inhibitors can have profound effects on fungal virulence traits. Specifically, 1-acetyl-β-carboline, secreted by Lactobacillus rhamnosus, alongside related β-carbolines, represses the induction of filamentation in C. albicans by targeting the DYRK (dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase) Yak1 (180). Thus, β-carbolines present a novel antivirulence strategy as they are capable of blocking Candida biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo using a rat catheter model of C. albicans infection (180).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Recent innovations in the antifungal drug space have made notable progress in expanding the clinical arsenal of antifungals. Ibrexafungerp’s approval for clinical use in 2021 signifies the first new antifungal class approved for clinical use in two decades (32). Moreover, the continued advance through the drug discovery pipeline of many drugs, including fosmanogepix, highlights the significant breakthroughs that are currently being made in the quest for the discovery of novel antifungals. It is important to continue the collective efforts between academic researchers, clinicians, public health professionals, and industrial partners to work to expand the antifungal arsenal through the development of drugs that both improve current compound classes, as well as represent completely novel therapies. Furthermore, academic research has also unveiled auspicious molecular targets such as calcineurin, Hsp90, lipid biosynthesis, and kinases that warrant rapid, concerted, target-based innovation for the next generation of antifungal candidates. There is great potential to generate novel antifungal drugs, especially considering advances in structure-guided drug design and genomic technologies, which will undoubtedly be required to translate potential antifungal compounds into clinical candidates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all current and past Cowen lab members for helpful discussions.

L.E.C. is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation grant (FDN-154288) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grants (R01AI127375, R01AI165466, and R01AI162789). L.E.C. is a Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Microbial Genomics & Infectious Disease and co-director of the CIFAR Fungal Kingdom: Threats & Opportunities program.

Biographies

Emily Puumala completed her integrated master’s degree at Durham University’s Department of Biosciences in Durham, UK, and recently completed her Ph.D. at the University of Toronto with Dr. Leah Cowen. Emily joined the Cowen lab in late 2018 and leveraged small molecule screening libraries to identify and characterize the antifungal activity of previously unexploited chemical matter.

Sara Fallah completed her Honours Bachelor of Science degree at Queen’s University. As of 2021, she is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Toronto in Dr. Leah Cowen’s laboratory. Sara’s research is focused on chemical biology, where she screens structurally-diverse small molecule libraries against Candida albicans to identify new chemical probes for antifungal research and development.

Nicole Robbins pursued her doctoral research in Dr. Leah Cowen’s lab at the University of Toronto from 2007-2012 where she focused on mechanisms by which the molecular chaperone Hsp90 governed fungal drug resistance in C. albicans. She then worked as a postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Gerry Wright where she used high-throughput screening methodologies to look for novel compound combinations with efficacy against diverse fungal pathogens. Nicole is now a Senior Research Associate at the University of Toronto where she is involved in many projects that aim to provide a global view of the circuitry in fungal pathogens that governs drug resistance, morphogenesis, and virulence.

Leah E. Cowen completed her doctoral research with Jim Anderson and Linda Kohn at the University of Toronto focused on the genomic architecture of adaptation to antifungal drugs. As a postdoctoral fellow with Susan Lindquist at the Whitehead Institute, she then investigated how the molecular chaperone Hsp90 impacts on fungal evolution and phenotypic diversity. Since 2007, she has been a Canada Research Chair in Microbial Genomics and Infectious Disease in the Department of Molecular Genetics at the University of Toronto. Her research has been recognized with a myriad of awards including a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences, a Merck Irving S. Sigal Memorial Award, an E. W. R. Steacie Award from the Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council, a Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher Award, and a Grand Challenges Canada Star in Global Health Award. She is an elected Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, American Association for the Advancement of Science, and Canadian Academy of Health Sciences.

Contributor Information

Leah E. Cowen, Email: leah.cowen@utoronto.ca.

Graeme N. Forrest, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele R, Denning D. 2017. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases: estimate precision. J Fungi 3:57. doi: 10.3390/jof3040057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fisher MC, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Berman J, Bicanic T, Bignell EM, Bowyer P, Bromley M, Brüggemann R, Garber G, Cornely OA, Gurr SJ, Harrison TS, Kuijper E, Rhodes J, Sheppard DC, Warris A, White PL, Xu J, Zwaan B, Verweij PE. 2022. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:557–571. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee Y, Puumala E, Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2021. Antifungal drug resistance: molecular mechanisms in Candida albicans and beyond. Chem Rev 121:3390–3411. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burki T. 2023. WHO publish fungal priority pathogens list. The Lancet Microbe 4:e74. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . 2022. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241.

- 6. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2010. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol 36:1–53. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacobs SE, Jacobs JL, Dennis EK, Taimur S, Rana M, Patel D, Gitman M, Patel G, Schaefer S, Iyer K, Moon J, Adams V, Lerner P, Walsh TJ, Zhu Y, Anower MR, Vaidya MM, Chaturvedi S, Chaturvedi V. 2022. Candida auris pan-drug-resistant to four classes of antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0005322. doi: 10.1128/aac.00053-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Turnidge JD, Castanheira M, Jones RN. 2019. Twenty years of the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program: results for Candida species from 1997-2016. Open Forum Infect Dis 6:S79–S94. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eyre DW, Sheppard AE, Madder H, Moir I, Moroney R, Quan TP, Griffiths D, George S, Butcher L, Morgan M, Newnham R, Sunderland M, Clarke T, Foster D, Hoffman P, Borman AM, Johnson EM, Moore G, Brown CS, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Jeffery KJM. 2018. A Candida auris outbreak and its control in an intensive care setting. N Engl J Med 379:1322–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rutsaert L, Steinfort N, Van Hunsel T, Bomans P, Naesens R, Mertes H, Dits H, Van Regenmortel N. 2020. COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intensive Care 10:71. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00686-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nam H, Ison MG. 2020. Aspergillosis complicating severe influenza and RSV pneumonia in ICU patients: a retrospective cohort study. Transplantation 104:S315–S316. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000700108.90238.7b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Specht CA, Lee CK, Huang H, Tipper DJ, Shen ZT, Lodge JK, Leszyk J, Ostroff GR, Levitz SM. 2015. Protection against experimental cryptococcosis following vaccination with glucan particles containing Cryptococcus alkaline extracts. mBio 6:e01905-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01905-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rajasingham R, Govender NP, Jordan A, Loyse A, Shroufi A, Denning DW, Meya DB, Chiller TM, Boulware DR. 2022. The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: a modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 22:1748–1755. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00499-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bermas A, Geddes-McAlister J. 2020. Combatting the evolution of antifungal resistance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol 114:721–734. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Dyke MCC, Teixeira MM, Barker BM. 2019. Fantastic yeasts and where to find them: the hidden diversity of dimorphic fungal pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol 52:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spallone A, Schwartz IS. 2021. Emerging fungal infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 35:261–277. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benedict K, Richardson M, Vallabhaneni S, Jackson BR, Chiller T. 2017. Emerging issues, challenges, and changing epidemiology of fungal disease outbreaks. Lancet Infect Dis 17:e403–e411. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30443-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rauseo AM, Coler-Reilly A, Larson L, Spec A. 2020. Hope on the horizon: novel fungal treatments in development. Open Forum Infect Dis 7:ofaa016. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . 2020. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs for antifungal agents. Eucast. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . 2022. European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing overview of antifungal ECOFFs and clinical breakpoints for yeasts, moulds and dermatophytes using the EUCAST E.Def 7.3, E.Def 9.4 and E.Def 11.0 procedures. Eucast. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perfect JR. 2017. The antifungal pipeline: a reality check. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16:603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xue A, Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2021. Advances in fungal chemical genomics for the discovery of new antifungal agents. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1496:5–22. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson TM, Clay MC, Cioffi AG, Diaz KA, Hisao GS, Tuttle MD, Nieuwkoop AJ, Comellas G, Maryum N, Wang S, Uno BE, Wildeman EL, Gonen T, Rienstra CM, Burke MD. 2014. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat Chem Biol 10:400–406. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shapiro RS, Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2011. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75:213–267. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00045-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Day JN, Chau TTH, Wolbers M, Mai PP, Dung NT, Mai NH, Phu NH, Nghia HD, Phong ND, Thai CQ, Thai LH, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, Duong VA, Hoang TN, Diep PT, Campbell JI, Sieu TPM, Baker SG, Chau NVV, Hien TT, Lalloo DG, Farrar JJ. 2013. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med 368:1291–1302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2022. Antifungal discovery. Curr Opin Microbiol 69:102198. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2022.102198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allen D, Wilson D, Drew R, Perfect J. 2015. Azole antifungals: 35 years of invasive fungal infection management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 13:787–798. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1032939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berkow EL, Lockhart SR. 2017. Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: a current perspective. Infect Drug Resist 10:237–245. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S118892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robbins N, Wright GD, Cowen LE, Heitman J. 2016. Antifungal drugs: the current armamentarium and development of new agents. Microbiol Spectr 4:903–922. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0002-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nett JE, Andes DR. 2016. Antifungal agents: spectrum of activity, pharmacology, and clinical indications. Infect Dis Clin North Am 30:51–83. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Neoh CF, Jeong W, Kong DCM, Slavin MA. 2023. The antifungal pipeline for invasive fungal diseases: what does the future hold? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 21:577–594. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2023.2203383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee A. 2021. Ibrexafungerp: first approval. Drugs 81:1445–1450. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01571-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamoth F. 2023. Novel therapeutic approaches to invasive candidiasis: considerations for the clinician. Infect Drug Resist 16:1087–1097. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S375625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiménez-Ortigosa C, Perez WB, Angulo D, Borroto-Esoda K, Perlin DS. 2017. De novo acquisition of resistance to SCY-078 in Candida glabrata involves FKS mutations that both overlap and are distinct from those conferring echinocandin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00833-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00833-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang F, Zhao M, Braun DR, Ericksen SS, Piotrowski JS, Nelson J, Peng J, Ananiev GE, Chanana S, Barns K, Fossen J, Sanchez H, Chevrette MG, Guzei IA, Zhao C, Guo L, Tang W, Currie CR, Rajski SR, Audhya A, Andes DR, Bugni TS. 2020. A marine microbiome antifungal targets urgent-threat drug-resistant fungi. Science 370:974–978. doi: 10.1126/science.abd6919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kapoor M, Moloney M, Soltow QA, Pillar CM, Shaw KJ. 2019. Evaluation of resistance development to the Gwt1 inhibitor manogepix (APX001A) in Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:1–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01387-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hodges MR, Ople E, Wedel P, Shaw KJ, Jakate A, Kramer WG, Marle S van, van Hoogdalem E-J, Tawadrous M. 2023. Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral fosmanogepix, a first-in-class antifungal agent, in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 67:e0162322. doi: 10.1128/aac.01623-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watanabe NA, Miyazaki M, Horii T, Sagane K, Tsukahara K, Hata K. 2012. E1210, a new broad-spectrum antifungal, suppresses Candida albicans hyphal growth through inhibition of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:960–971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00731-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iyer KR, Revie NM, Fu C, Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2021. Treatment strategies for cryptococcal infection: challenges, advances and future outlook. Nat Rev Microbiol 19:454–466. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00511-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miyazaki M, Horii T, Hata K, Watanabe N-A, Nakamoto K, Tanaka K, Shirotori S, Murai N, Inoue S, Matsukura M, Abe S, Yoshimatsu K, Asada M. 2011. In vitro activity of E1210, a novel antifungal, against clinically important yeasts and molds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4652–4658. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00291-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]