SUMMARY

Pneumocystis jirovecii is a ubiquitous opportunistic fungus that can cause life-threatening pneumonia. People with HIV (PWH) who have low CD4 counts are one of the populations at the greatest risk of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). While guidelines have approached the diagnosis, prophylaxis, and management of PCP, the numerous studies of PCP in PWH are dominated by the 1980s and 1990s. As such, most studies have included younger male populations, despite PCP affecting both sexes and a broad age range. Many studies have been small and observational in nature, with an overall lack of randomized controlled trials. In many jurisdictions, and especially in low- and middle-income countries, the diagnosis can be challenging due to lack of access to advanced and/or invasive diagnostics. Worldwide, most patients will be treated with 21 days of high-dose trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, although both the dose and the duration are primarily based on historical practice. Whether treatment with a lower dose is as effective and less toxic is gaining interest based on observational studies. Similarly, a 21-day tapering regimen of prednisone is used for patients with more severe disease, yet other doses, other steroids, or shorter durations of treatment with corticosteroids have not been evaluated. Now with the widespread availability of antiretroviral therapy, improved and less invasive PCP diagnostic techniques, and interest in novel treatment strategies, this review consolidates the scientific body of literature on the diagnosis and management of PCP in PWH, as well as identifies areas in need of more study and thoughtfully designed clinical trials.

KEYWORDS: HIV, PCP, PWH, Pneumocystis carinii, Pneumocystis jirovecii

BACKGROUND

Introduction

Pneumocystis jirovecii is a ubiquitous opportunistic fungus that can cause life-threatening pneumonia. People who are immune suppressed are at greatest risk of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) (1). Typical at-risk populations include people with HIV (PWH); transplant recipients (both solid organ and hematologic); use of long-term higher dose corticosteroids; and/or the receipt of treatment with other immunosuppressive medications, such as chemotherapies and biologics, for cancer or auto-immune conditions (2). Research into the diagnosis and management of PCP had a renaissance during the 1980s, concomitant with the recognition of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (3). Although numerous studies of PCP have taken place, by virtue of the 1980s and 1990s predominance, most have included younger male populations despite PCP affecting both sexes and a broad age range. Many studies have been small and observational in nature, with a lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and few head-to-head treatment trials (4). While guidelines (5–7) have addressed the diagnosis, prophylaxis, and management of PCP, it is clear that more research is needed. With the advent of modern-day antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) for the treatment of HIV and improved PCP diagnostic techniques, we set out to craft a review to consolidate the scientific body of literature on the diagnosis and management of PCP and to highlight areas in need of more study and thoughtfully designed clinical trials. To avoid confusion, we have used the abbreviation PCP (and not PJP) (8) throughout this review, as it is still a preferred term of many organizations.

Classification and naming

PCP was first described in the literature in 1909 by Carlos Chagas, who found cyst-like structures within the lungs of marmosets and guinea pigs and thought these might represent the cyst-like stage of Trypanosoma cruzi, a protozoan (9, 10). By 1912, it was determined that the cysts were not related to trypanosomes and, furthermore, that they could be found in street rats (9). The organism was eventually named Pneumocystis carinii in honor of Antonio Carini, director of the Pasteur Institute. It was only much later that human cases were recognized, including those reported by Vanek and Jírovec (11) in the 1950s in premature and malnourished children, which inspired the name Pneumocystis jirovecii for the human variant (proposed in 1994 and adopted in 1999) (8). Additionally, following the advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, pneumocystis species were eventually definitively classified as ascomycetous fungi in 1988 (12).

Epidemiology

Prior to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, PCP was more commonly associated with pediatric oncology cases and malnourished populations (13). In the early 1980s, literature emerged describing a community outbreak of PCP, linking the relationship between the opportunistic fungus and populations with both acquired and congenital deficits in T-cell immunity (14). Ultimately, this discovery heralded the recognition of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Transmission models remained unclear. For a long time, it was hypothesized that initial pneumocystis infection occurred in childhood (13, 15) with clinically relevant infection only developing later in life secondary to reactivation in the presence of an immunocompromising event (e.g., HIV, solid organ and/or stem cell transplant, and glucocorticoid use). There is some evidence that supports a hypothesis of childhood infection followed by reactivation (16). For example, pneumocystis antibodies were detected by 7 months of age in 83% of children included in one study, with titers of at least 1:16 developing by the age of 4 (13). A small study by Huang et al. (17) also found that up to 69% of PWH may be colonized with P. jirovecii. However, it should be noted that patients with a prior history of PCP were numerically more likely to be colonized, possibly representing clearing infection, as opposed to colonization. Along those lines, following treatment for PCP, studies have shown that PWH may be asymptomatic with persistent P. jirovecii cysts (18, 19). A systematic review of adults with HIV in Africa detected P. jirovecii (by any PCR or microscopy technique) in 9% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0%–45%] of 140 asymptomatic adults, compared to 19% (95% CI 12%–27%) of 3,583 individuals with respiratory symptoms (20). It has also been noted that in the setting of immune competence, people may be colonized and act as potential reservoirs through onward transmission (21).

More recent literature evaluated the potential for both human-to-human transmission and the existence of possible environmental reservoirs. In animal models, both immunocompromised (22) and immunocompetent (23) mice transmitted the organism to each other when in close proximity. Arguments have been made that results from mouse models cannot be extrapolated to humans, given different pneumocystis species; however, similar findings have been found in human renal transplant recipients (24). Other evidence in support of this theory is a more recent study that detected P. jirovecii DNA in the air surrounding patients with confirmed PCP, adding to the notion that airborne transmission can occur (25, 26).

Environmental reservoirs of P. jirovecii include water (27) and soil; PWH who contract PCP are more likely to participate in activities such as gardening, camping, and hiking (28), compared to age and CD4+ cell count matched controls [odds ratio (OR) 5.38, 95% CI 1.39–20.8 for gardening, and OR 7.68, 95% CI 1.34–44.1 for hiking/camping]. Urban infrastructure has also been shown to play a role, with transmission rates and genotypes of PCP varying by location (29, 30).

A further argument against the theory of reactivation as the primary or sole mechanism of infection relates to recurrent infections. In one study, immunosuppressed rodents with PCP had undetectable P. jirovecii PCR levels after immune reconstitution and did not develop PCP again after immunosuppression was resumed (31, 32). One small study in humans found that five patients with two episodes of PCP separated by three or more months had different gene sequences when isolates were compared; PCR testing did not suggest that gene switching was the cause (33, 34). This study supports that repeated acquired infections are possible.

PCP and advanced HIV

PCP is one of the most common opportunistic infections (OIs) in PWH (35) and, outside of HIV detected through screening, can still serve as the primary presentation leading to a diagnosis of advanced HIV (1, 36). Before ART therapy and PCP prophylaxis were available, between 70% and 80% of patients with AIDS developed the infection; it was associated with a significantly high mortality rate (~20% to 40%), and relapse rates were as high as 50% within the first 11 months of diagnosis (36). Early on, PCP rates were as high as 20 per 100 person years for those with a CD4 count below 200 cells/µL (37). Classically, PCP would present when the CD4 cell count fell below 200 cells/µL (37), particularly among people presenting with recurrent bacterial pneumonia, oral thrush, unintentional weight loss, higher viral loads (VLs), and/or CD4 percentage of <14% (38, 39). About 5% of PCP would occur with a CD4 count above 200 cells/µL (39), often in the context of a rapid decline in CD4 count and a high VL.

With the introduction of HIV screening, ART, and PCP prophylaxis, infections with P. jirovecii have declined steeply. A large American multicenter saw a 3.4% decrease in PCP incidence from 1992 to 1995 and a 21.5% decrease per year from 1996 to 1998 (40). Data from a systematic review and meta-analysis found that the pooled percentage of PCP among inpatients declined from 28% (4 studies, n = 192, 95% CI 21–34) in the 1990s to 27% between 2000 and 2004 (8 studies, n = 633, 95% CI 23–30), and from 2005 onward was 9% (11 studies, n = 1,768, 95% CI 8–10) (41). In this population, PCP tends to be more commonly diagnosed among inpatients due to increased access to more robust testing. From this same meta-analysis, uptake of PCP prophylaxis appeared to be low (34.4% or 1,377/4,002 PWH from 21 studies) (41). Other multicenter prospective cohort studies have also shown a marked improvement in the risk of PCP as the presenting OI for AIDS, with a relative hazard of 0.06 between 1996 and 1998, compared to 1990–1992 as the reference period (P < 0.001) (42). Long-term survival following a diagnosis of PCP has also substantially increased among patients who receive ART; however, in-hospital mortality for PCP remains similar, despite substantial improvements in critical care, highlighting how severe the infection can be (43).

DIAGNOSIS

The clinical presentation of PCP can be variable, depending on concomitant predisposing conditions (e.g., hematologic malignancy and corticosteroid exposure), the use and timing of ART and PCP prophylaxis, and the duration of illness prior to seeking medical attention. However, the most common presenting signs and symptoms are fever, cough, and progressive dyspnea, with the presence of ground-glass opacities on lung imaging (44). Based on these presenting clinical factors, coupled with typical imaging in an at-risk patient, the diagnosis of PCP may be suspected.

All studies of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical, radiological, and laboratory factors are constrained by limitations in the reference standard for PCP, partly due to difficulties in distinguishing colonization from infection (16, 45), and/or inadequate sensitivity of the available tests. The staining of autopsy specimens for the organism is probably the most robust way to confirm a diagnosis but is obviously not of any clinical utility. In some studies, even prior to the HIV epidemic, open lung biopsy was used to obtain large specimens of tissue to stain for organism identification (46). Moreover, while this may be another very robust reference standard, such an invasive test is rarely performed even in diagnostic accuracy studies.

Clinical predictors

To reiterate, common symptoms include the sub-acute onset of dyspnea, non-productive cough, and fever. While there are few formal studies describing the duration of symptoms in patients with HIV and PCP, it is generally considered to be a sub-acute condition with symptoms typically being present for a minimum of 1–2 weeks prior to presentation. Patients are classically tachypneic and tachycardic and have a paucity of signs on lung auscultation.

A systematic review and meta-regression of patients investigated for PCP in tropical and low- and middle-income countries found seven studies in adults (N = 701; 177 patients with PCP) and five studies in pediatric populations (N = 550; 192 patients with PCP) (47); clinical symptoms predictive of PCP with a high sensitivity (82%–100%) and high negative predictive value were the absence of cough and dyspnea on presentation; however, when these were present, they had poor specificity (6%–76%) and low positive predictive values. The authors also found that hemoptysis should prompt a search for alternative diagnoses, as it is a presenting symptom in only 3%–18% of cases.

While not all patients will require oxygen at presentation, several studies have suggested that the absence of exercise-induced changes in oxygen saturation using various methods could provide increased sensitivity for excluding PCP (48–51).

Extrapulmonary pneumocystosis is a rare presentation now that ART is more widely available. Most cases that have been described have occurred in advanced cases of HIV in patients who were not on PCP prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (52). The presentation depends on the involved organ and can present with or without the typical pulmonary findings (53).

Radiological predictors

Chest X-ray

Chest X-ray descriptions most associated with PCP in adults in the previous systematic review were “interstitial shadowing,” “fine shadowing,” “minimally abnormal not tuberculosis,” and “diffuse shadowing” (47). Chest X-ray descriptions least commonly associated with PCP in adults were “cavities,” “hilar lymph nodes,” and “classical TB.” In a high-income setting, Hsu et al. (44) attempted to discern chest X-ray findings associated with cytologically proven PCP in patients with and without HIV. In this case-control study of 69 patients with PCP and 270 controls who had bronchoscopy to exclude PCP, following multivariable analysis of chest X-ray features, only the radiologist’s impression that PCP was possible or likely (OR 4.5, 95% CI 1.8–10.9) and the presence of “increased interstitial markings” (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.6–5.1) remained independently associated with the diagnosis of PCP (adjusted c-statistic 0.64) (44).

It is important to note that the initial chest X-ray may be normal (44, 54–56) and that radiographic features progress and become homogeneous over time. Consequently, follow-up imaging [chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan] may be indicated. Additionally, PCP may also rarely present with unilateral or bilateral pneumothoraces (57) or pneumomediastinum (58), and it is reasonable to include untreated HIV complicated by PCP in the differential diagnosis. PCP can co-exist with other infecting pathogens that are responsible for a nodular appearance or can rarely present itself as nodules in the absence of other detected pathogens (59, 60).

CT scan of the thorax

High-resolution CT scan of the thorax offers increased sensitivity compared to chest X-ray (44, 54–56). The most common findings in PCP are increased patchy ground-glass opacities (44, 54, 55, 61, 62), particularly bilateral, and with a predilection for the upper lobes. While not entirely specific for PCP, the absence of ground-glass opacities strongly argues against the diagnosis. Other findings, such as the presence of pleural effusions or pulmonary nodules, reduce the probability of PCP; however, these findings are inadequate to exclude the diagnosis (44). Overall, Hsu et al. found that CT thorax offered fair discrimination (c-statistic 0.75), and a prediction model based on a combination of radiographic features was proposed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

CT scan findings and probability of PCP based on Hsu et al. (44)

| CT scan feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Absence of nodular disease | 5 |

| Absence of pleural effusion | 5 |

| Ground glass opacities | 9 |

| Increased interstitial markings | 10 |

| Scores | Probability of PCP |

| 5 or less | <5% |

| 9 or 10 | 5-10% |

| 14 | 10-15% |

| 15 | 15-20% |

| 19 or 20 | 25-30% |

| 24 | 40-45% |

| 29 | 60-65% |

Laboratory testing

Estimating the pre-test probability

A recent South African study looked to develop a risk prediction model for PCP in a low resource setting (63). Participants had a cough of any duration and met the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for being seriously ill. Independent predictors of PCP were a compatible chest X-ray as determined by an expert thoracic radiologist (likely/possible PCP = 3 points), low oxygen saturation (<94% = 2 points), and the absence of severe anemia (>9 g/L =1 point). The c-statistic for this model was 0.797 (95% CI 0.725–0.868), suggesting acceptable discrimination. A score of 0 (135 of 500 patients) was associated with a 0% risk of PCP; 1 point, 3.9%; 2 points, 7.7%; 3 points, 14.8%; 4 points, 26.4%; 5 points, 42.6%; and 6 points, 60.6%. Whether this model would generalize to well-resourced practice environments and how it might be affected by the receipt of ART and/or PCP prophylaxis (especially with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) are unclear.

Indirect testing

Lactate dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a ubiquitous intracellular enzyme involved in metabolism. The detection of extracellular LDH in the serum suggests cell death or damage. However, it is a non-specific marker which can be elevated in a variety of conditions including malignancies, hemolytic anemias, and ischemia. Serum LDH is frequently elevated in cases of PCP, and consequently, it has been proposed as a sensitive and inexpensive assay for PCP (64). However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that serum LDH alone had little diagnostic value for PCP, owing to a pooled sensitivity of 67% (95% CI 59%–75%) and specificity of 54% (95% CI 48%–61%) (65). However, this was based on only two studies: one study used a cut-off of 350 U/L (66), and the second study used a rise above the institutional upper limit of 250 U/L, or a 30% peak above the patient’s baseline value, most often measured upon presentation with symptoms (67). Whether LDH may have some diagnostic value with a modified cutoff (68), in combination with other tests (68), or as part of a multivariable clinical prediction rule (69) remains to be demonstrated.

(1,3)-Beta-D-glucan

(1,3)-Beta-D-Glucan (BDG) is a cell wall constituent in the ascus life-form of P. jirovecii and multiple other fungal pathogens. Various assays that detect BDG in the serum have been developed. The assay can be positive due to the presence of other fungal infections, in patients with bacteremia, in patients on certain medications, in patients receiving albumin or immunoglobulin therapy, and in patients undergoing hemodialysis with cellulose-based membranes and filters (70). Notwithstanding this, a recent meta-analysis found that the test performed reasonably well in PWH suspected to have PCP, with a pooled sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 83% corresponding to pooled negative and positive likelihood ratios of 0.07 and 5.5, respectively. Most studies (15 of 23) used the Fungitell assay and the manufacturer-recommended cut-off of 80 pg/mL. This suggests that a negative BDG is associated with a post-test probability of disease of ≤5%, provided that the pre-test probability is below 50% (70). Unfortunately, a positive test may only be associated with a moderate probability of disease unless the pre-test probability is very high. It is possible that a higher BDG cutoff (e.g., 400 pg/mL) may better correlate with PCP, allowing for a higher specificity and positive likelihood ratios at the expense of sensitivity and the negative likelihood ratio (71), but this requires further examination.

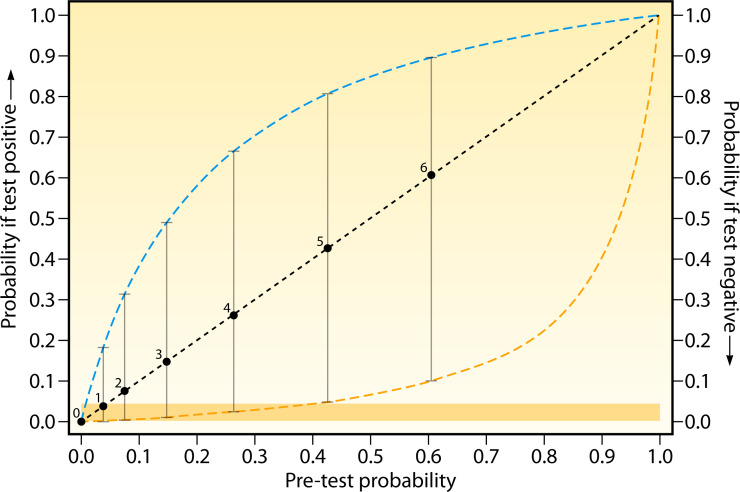

Another promising approach could be to integrate the BDG into a testing algorithm based on the pre-test probability of disease established though a clinical (63) or radiographic (44) prediction rule. An example based on the prediction rule by Maartens et al. (63) is provided in Fig. 1. Figure 1 suggests that BDG could be a reasonable “rule-out” test for scores 2–4 if a clinician is comfortable with a probability of ≤5% as a threshold for taking any further action. The major caveat being that one should be very careful in using BDG as a definitive “rule-in” test, as even with a score of 6, the diagnosis is not rendered “certain.”

Fig 1.

Leaf plot for the diagnosis of PCP in seriously ill patients with HIV. Pre-test probability (diagonal line) with boxes showing scores as determined by Maartens et al.’s PCP prediction rule (63) and using test characteristics from Del Corpo et al. (70). Vertical lines represent the change in probability following a positive (upward intersection with blue dashed line) or negative (downward intersection with yellow dashed line) BDG test. The yellow shaded area represents the area where a negative test establishes a post-test probability of 5% or below.

Direct testing

Confirmatory testing involves staining and/or molecular testing of respiratory samples [e.g., bronchioalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), nasopharyngeal swab, nasopharyngeal aspirate, and induced sputum]. Currently, BALF is considered the criterion standard with the highest sensitivity and specificity (72–76). However, to truly determine which respiratory sample is the criterion standard would require a study comparing the yield from different respiratory samples, from the same patient(s), while employing a consistent laboratory detection method. The lack of a standardized sampling technique can impact the sensitivity and specificity of any chosen respiratory sample. Limitations of BALF also include the fact that this invasive procedure is expensive, carries some risk to the patient, may not always be feasible for patients with more advanced pulmonary disease, and may not be available in resource-constrained settings (63) or in facilities without trained personnel. Non-directed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) may deserve further study, as it does not require use of a bronchoscope.

Prior to (or instead of) performing a BAL, induced sputum offers a less invasive alternative (65). Nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirate and oral washes also represent promising less invasive techniques for obtaining specimens; however, evidence of their operating characteristics is more limited (65). Detection in respiratory specimens can be of the trophic form and/or the cystic form with tests including conventional staining with microscopy, immunofluorescence, or PCR (73, 77, 78).

Cytology

To a great extent, cytologic staining has been supplanted by fluorescent monoclonal antibody staining because of higher sensitivity in induced sputum samples and because they stain both trophic forms and cysts (79–81).

There are a variety of stains which can detect P. jirovecii in pathologic specimens such as BALF cytology. Giemsa, Diff-Quik, and Wright stains can detect the cyst but do not stain its wall, whereas the Gomori-methenamine-silver (GMS) stain, Gram-Weigert, cresyl echt violet, toluidine blue O (TBO), and calcofluor white (CW) do stain the cell wall (82). Trophic forms can be detected with Wright-Giemsa, Diff-Quik (83), modified Papanicolaou, or Gram-Weigert stains (80). Head-to-head comparisons of different techniques are limited in size, the number of stains being compared, and in the reference standard being used, to evaluate sensitivity and specificity. In one of the largest comparisons (310 slides, 65 considered positive by more than one test), GMS and CW performed similarly and had greater sensitivity than Diff-Quick (79.4% and 73.8% vs 49.2%) but with reduced sensitivity compared to a fluorescent stain (90.8%) (84).

The major limitation of any cytologic examination is sensitivity due to sample and processing quality combined with variable observer performance. Additionally, sensitivity may be decreased with increasing durations of empiric therapy. False-negative cytology is less common in PWH when compared to people without HIV (85); however, it has been reported in up to 35% of patients when using a composite reference standard for diagnosis (86).

Induced sputum offers a less invasive option than bronchoscopy but with lower sensitivity (50%) in a meta-analysis combining all modalities of cytology (65). Specificity remained high (~100%), yielding a negative likelihood ratio of 0.5 and an infinite positive likelihood ratio (65).

Immunofluorescence

There are a variety of antibody products available for immunofluorescence. In general, they have been found to have higher sensitivity than conventional stains and offer the advantage of staining both cyst and trophic forms (79–81).

In a meta-analysis of 316 PWH who underwent both bronchoscopy and sputum induction, induced sputum immunofluorescence provided a 74% sensitivity and 100% specificity with a corresponding negative likelihood ratio of 0.26 and infinite positive likelihood ratio (65). Like cytology, sensitivity may be decreased with increasing durations of empiric therapy.

PCR

The advantage of PCR is its high sensitivity, with the concomitant challenge of distinguishing colonization from infection. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of BALF PCR for the diagnosis of PCP, the pooled sensitivity was 98.3%; the specificity was 91.0%; the negative likelihood ratio was 0.02; and the positive likelihood ratio was 10.8 (73). DNA levels above 1,000 copies/mL of fluid have been suggested as a cut-off to distinguish colonization from infection in two studies (87, 88) that used a composite of clinical and microbiological endpoints; however, there is no universally accepted standard. Additionally, variations in BAL technique (e.g., volume and type of fluid) and between commercial and “home-brew” assays are likely to further complicate this distinction. Targeted application of PCR testing to patients who have a reasonable pre-test probability of PCP based on clinical and radiographic factors is likely essential to aid in the distinction between colonization and infection. Importantly, very early disease might be associated with lower levels of DNA, suggesting colonization; however, clinical progression can be an important indicator that testing may need to be repeated. The impact of prior therapy on PCR sensitivity may be less than for cytology or immunofluorescence; however, it is also probable that longer durations of prior treatment in the context of fewer organisms would diminish sensitivity.

Induced sputum is the most well studied non-invasive specimen for PCR and likely should be considered the preferred non-invasive method with a pooled sensitivity of 99% and specificity of 96% in a meta-analysis (65) corresponding to a negative likelihood ratio of 0.01 and positive likelihood ratio of 24.8.

Nasopharyngeal aspirates or swabs offer the opportunity for quick and non-invasive sampling, and a variety of other diagnostic tests can potentially be performed on the same sample (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing). For PWH in a systematic review (65), nasopharyngeal aspirate PCR had a sensitivity of 95%, a specificity of 100%, a negative likelihood ratio of 0.12, and an infinite positive likelihood ratio. A subsequent study of 35 patients (HIV status unknown) who underwent both nasopharyngeal (NP) swab testing and bronchoscopy found that NP PCR specimens had 72.2% positive agreement and 100% negative agreement with BALF PCR (89). Thus, larger studies are absolutely required to confirm these estimates, as sample sizes were relatively small.

P. jirovecii may be found in oral washes if the organism has been coughed or recently inhaled into the oropharyngeal tract. Oral washes can be obtained quickly and non-invasively, and positive tests of oral washes may reflect an even higher fungal burden in the lower respiratory tract. However, there are theoretical disadvantages, such as increased degree of PCR inhibition due to dilution from pharyngeal secretions and the inability of organisms to reach the oral cavity in low fungal burden infections. In a systematic review, oral wash PCR had a sensitivity of 74%, a specificity of 95%, a negative likelihood ratio of 0.27, and a positive likelihood ratio of 14.8 (65).

Consensus definitions of definitive and probable PCPs

Consensus definitions have been proposed to guide the diagnosis of PCP in people without HIV for the purposes of epidemiologic studies, diagnostic evaluations and RCTs (90, 91). These include a combination of host factors and clinical features, compatible radiological findings, and microbiological evidence of infection. A definitive diagnosis of PCP was defined as compatible clinical and radiological features, with identification of the organism microscopically in tissue, BAL fluid, or expectorated sputum, by either conventional or immunofluorescence staining. A probable diagnosis was defined as an appropriate host, with clinical features, in conjunction with mycological evidence (such as an elevated serum level of BDG of ≥80 ng/L or detection by PCR).

In the context of HIV, it could be reasonable to consider the following as host factors supporting the diagnosis:

PWH who are not on ART with a CD4 count of <200 cells/µL (37) or CD4 percentage of <14% (39), particularly with a history of unintentional weight loss, thrush, and/or elevated plasma RNA levels (38).

PWH who have recently started ART where immune reconstitution PCP is a concern (92).

PWH who have additional non-HIV-associated host factors for PCP (e.g., renal transplant or a hematologic malignancy).

Stage 4 HIV per the WHO classification system (93).

Novel tests

Studies have performed RNAseq after antibiotic pressure with echinocandins that targeted the ascus life form and revealed unique genes that are expressed in trophs that may serve as novel diagnostics (94) which may offer the advantage of better discerning colonization from infection.

Additionally, urine antigen testing has proven valuable in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, and preliminary studies have shown that other fungal infections such as cryptococcosis, blastomycosis, and aspergillosis may be detectable by urine lateral-flow assay testing (95–102). Urine testing for PCP may represent a new frontier for development of non-invasive molecular diagnostic techniques, but studies are needed to ascertain feasibility.

Evidence gaps

There are a variety of areas where further work would be beneficial. The estimation of pre-test probability seems to be underdeveloped. Clinical prediction scores which outperform the WHO model and are also validated for resource-rich practice settings could help better refine diagnostic algorithms. Exercise-induced hypoxemia as a predictive of disease seems to be a low-cost, widely accessible, and inexpensive test which would also be worthy of more exploration. All diagnostic schemata will need to account for the reality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which can have similar chest radiograph appearances. An emphasis on timely non-invasive diagnosis (with or without BDG) would likely be appropriate.

Another interesting area of research would be to risk stratify patients with newly diagnosed PCP for the development of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome to reduce the risk of hospitalization, modulate the dose and duration of corticosteroids, and avoid potentially unnecessary delays in initiating ART.

PROPHYLAXIS

Indications for primary prophylaxis

Compared to placebo, PCP prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the incidence of PCP (risk ratio [RR] 0.39, 95% CI 0.23–0.46) and PCP-related mortality (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.1–1.34) among PWH (103). PCP prophylaxis is recommended when the absolute CD4 count is below 200 cells/µL or when the percentage of CD4 cells among total lymphocytes is <14%, regardless of whether ART has been initiated (104). This is supported by a strong correlation between absolute and relative CD4 counts and the incidence of PCP, and the fact that up to 95% of PWH have a CD4 count of <200 cells/µL at the time of PCP diagnosis (37, 39). However, it is worth noting that most cases occur with a CD4 count of <100 cells/µL, and most data predate modern ART, particularly integrase inhibitor-based regimens which can achieve rapid virologic control.

Although not mentioned in the current Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines (104), prior versions recommended PCP prophylaxis for patients with a history of AIDS-defining illness or oropharyngeal candidiasis (5, 37). European HIV guidelines advise to start PCP prophylaxis in the presence of oropharyngeal candidiasis (7). Indeed, oropharyngeal candidiasis is a predictive factor for PCP that is independent of CD4 count (105). Decisions to initiate prophylaxis in these contexts need to be made on a case-by-case basis.

PCP prophylaxis may also be considered in patients with CD4 counts between 200 and 250 cells/µL who are delaying the start of ART and are unable to present for frequent monitoring of CD4 counts. It is also relevant to note that guidance from the WHO recommends prophylaxis in an all adults (including pregnant people) with advanced HIV and/or a CD4 count of <350 cells/µL (106). It is unclear that this recommendation generalizes outside of resource-limited settings.

Prophylaxis is not indicated for those receiving treatment or maintenance therapy with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine for toxoplasmic encephalitis as this regimen cross-protects against PCP (107). However, per a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, TMP-SMX appeared to be as effective and safer than pyrimethamine-containing regimens for toxoplasmic encephalitis; in this context, TMP-SMX may be an ideal choice for treatment of toxoplasmic encephalitis and PCP prophylaxis crossover (107).

Prophylactic regimens

Table 2 compares different regimens for prophylaxis, doses, and adverse events (AEs) of note.

TABLE 2.

Prophylactic regimens for PCPa

| Drug name | Dose | Notes | Adverse drug events and side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole | One single- or double-strength tab po daily or one double-strength tab po three times a week | Drug-drug interactions with ACEi/ARB/spironolactone Doubles as prophylaxis against other pathogens (e.g., toxoplasma) and several bacterial infections (respiratory, enteric, and urinary pathogens); if used for this dual purpose, 1 DS tab daily may be considered. When selecting the regimen, balance toxicity vs efficacy. |

Rash (including Stevens-Johnson syndrome), hyperkalemia, increased creatinine, transaminase elevation, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia |

| Atovaquone | 1,500 mg po daily | Should be taken with a fatty meal to increase absorption Can be expensive and has an unpleasant taste |

Gastrointestinal upset, diarrhea, fever, transaminase elevation, and rash |

| Dapsone | 100 mg po daily (if toxoplasma serology is negative) Up to 200 mg daily combined with pyrimethamine and folinic acid (if toxoplasma serology is positive) |

Option to combine with pyrimethamine for cross-protection against toxoplasmosis Screen for G6PD deficiency prior to use. |

Rash, fever, nausea/vomiting, hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, and transaminase elevation |

| Aerosolized pentamidine | 300 mg monthly via nebulizer Biweekly dosing has also been studied |

Requires specialized personnel and equipment Potential to transmit respiratory pathogens Risk of isolated apical disease or extrapulmonary disease |

Bronchospasm and cough |

1823 G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; ACEi, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DS, double strength; po, per os.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

TMP-SMX is recommended as the first-line agent for PCP prophylaxis (7, 104). Several reasons support this recommendation, including the cost, accessibility, and efficacy, as well as cross-protection against other pathogens. A meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrated that in the prevention of PCP in PWH, TMP-SMX was superior to aerosolized pentamidine (AP) (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45–0.75) and was potentially superior when compared to dapsone-based regimens (DBRs) (RR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.34–1.10, 95% probability of superiority) (103).

Prophylaxis with TMP-SMX cross-protects against several other infections. Like DBRs, it cross-protects against toxoplasmosis (103), which occurs in PWH with CD4 counts of <100 cells/µL (108). TMP-SMX also has broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, including activity against many respiratory, enteric, and urinary pathogens, which DBRs, AP, and atovaquone lack (6). Indeed, a large RCT demonstrated that TMP-SMX PCP prophylaxis also significantly reduced the incidence of bacterial infections compared to DBRs and AP (109).

There exist several dosing strategies of TMP-SMX for PCP prophylaxis with conflicting evidence. European HIV guidelines (7) recommend daily single-strength (SS) (400/80 mg), daily double-strength (DS) (960/160 mg), or thrice weekly DS TMP-SMX tablets as first line. In contrast, the DHHS HIV guidelines recommend the daily SS or DS tablets as first line and the thrice weekly regimen as second line (104). The rationale for this recommendation is that there is more RCT evidence for higher doses of TMP-SMX in the prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis and bacterial infections. Two RCTs comparing daily DS vs SS TMP-SMX tablets found similar efficacy in prevention of PCP and one RCT showed an increased incidence of AEs in the DS arm (110, 111). One RCT found a similar incidence of PCP but reduced discontinuation due to AEs between daily vs thrice weekly DS TMP-SMX tablets (112). The largest trial conducted to date on PCP prophylaxis, consisting of 2,625 patients, compared daily vs thrice weekly DS TMP-SMX tablets (113). They found a similar incidence of PCP and all-cause mortality, but an increased risk of discontinuation due to toxicity and incidence of any AE with daily administration. However, in the thrice weekly arm, there was an increased incidence of the combined outcome of PCP and bacterial pneumonia, and an increased incidence of PCP among patients on-treatment or discontinuing treatment within the preceding 30 days. For these reasons, the study’s authors recommended daily over thrice weekly DS TMP-SMX among PWH.

AEs are frequent in patients receiving PCP prophylaxis with TMP-SMX. The pooled incidence of discontinuation due to AEs among PWH is 19 per 100 patient-years (103). In contrast, among people without HIV, TMP-SMX is much better tolerated, with an incidence of discontinuation due to toxicity of 1.6 per 100 patient-years (114). The risk of discontinuation due to toxicity is reduced by half when thrice weekly compared to daily DS TMP-SMX tablets are used (103, 113). The most common AEs leading to discontinuation are rashes, hypersensitivity reactions, fever, and hematologic, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and renal complications (113, 115). Patients experiencing mild AEs should temporarily discontinue prophylaxis. Reinstitution of TMP-SMX prophylaxis should be strongly considered when symptoms resolve. Cases of hypersensitivity reactions to TMP-SMX are recommended to receive desensitization using a graded protocol. Various protocols exist for TMP-SMX desensitization, and up to 80% of patients can successfully be desensitized (116–118). However, severe cutaneous adverse reactions to TMP-SMX (e.g., Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis) are an absolute contraindication to restarting, and these patients should receive a second-line regimen. Of note, if TMP-SMX is stopped following desensitization, repeat desensitizing is thought to be necessary prior to restarting, and it is unknown how quickly tolerance is lost (119).

Outside of the HIV context, some RCTs have been exploring half-strength regimens (e.g., 200/40 mg) and report similar efficacy in PCP prevention with less discontinuation due to side effects (120). This might represent an interesting option for patients with CD4 counts above 100 cells/µL, where the risk of PCP and toxoplasmic encephalitis is lower, and the improved tolerability could prove net beneficial; however, prospective studies would be warranted.

Dapsone

Dapsone is recommended as a second-line agent for PCP prophylaxis in patients with an intolerance to TMP-SMX (7, 104). There is heterogeneous RCT evidence comparing DBRs vs TMP-SMX in the prevention of PCP among PWH. Some suggest that the incidence of PCP is comparable between the two groups (121–123), while others suggest that TMP-SMX is superior (124, 125). A meta-analysis found that they were comparable; however, the odds of prevention of PCP for TMP-SMX compared to DBRs was 0.61 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.10) (103), which corresponds to a 95.1% probability of TMP-SMX superiority. DBRs have comparable efficacy compared to AP (103, 121, 122, 126, 127). However, dapsone is advantageous over AP because the option to combine with pyrimethamine confers cross-protection against toxoplasmosis (125, 127) with similar efficacy as TMP-SMX (124, 126).

Several DBRs exist for PCP prophylaxis. Dapsone 100 mg daily or 50 mg twice a day are options for patients with negative toxoplasma serology (7, 104, 121). If the patient has a positive serology for toxoplasmosis, then dapsone 200 mg, pyrimethamine 75 mg, and folinic acid 25 mg/week are recommended by both the DHHS and European HIV guidelines (7, 104), based on a study comparing this regimen to aerosolized pentamidine (126). There appeared to be a reduced incidence of toxoplasmosis among those who tolerated the high-dose dapsone regimen (<70% of participants).The DHHS guidelines also list dapsone 50 mg, pyrimethamine 50 mg, and folinic acid 25 mg weekly as an option, based on a study that compared this regimen to aerosolized pentamidine (104, 128). There is a paucity of data directly comparing DBRs head-to-head. One RCT found that breakthrough PCP was more frequent among patients on dapsone who decreased their dose from 100 to 50mg because of toxicity (121). Indirect comparisons of RCTs using different dosages of DBRs suggest that higher doses of dapsone are more efficacious but less well tolerated (103). The pooled incidence of discontinuation due to toxicity of DBRs is 15 per 100 patient-years (but may be as high as 29 per 100 patient-years for 100 mg daily), which is significantly lower than that of TMP-SMX but significantly higher than AP (103). The most common AEs associated with DBRs are rash, fever, nausea/vomiting, and hematologic or hepatic toxicity (103, 127). Screening for glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is required prior to dapsone use as it can precipitate hemolytic anemia in susceptible patients. Another rare but potentially lethal side effect is methemoglobinemia, which can present as cyanosis with a relatively normal oxygen saturation with or without symptoms (e.g., confusion, headache, dyspnea, or chest pain). As dapsone and dapsone metabolites have a long half-life (exceeding 30 hours and in some cases several days); cases have also been observed after stopping dapsone, particularly with exposure to a second oxidizing agent (e.g., chloroquine or primaquine) in PWH (129). While it is outside the scope of this review to discuss the diagnosis and management methemoglobinemia, it is prudent for those who prescribe dapsone to be prepared (130).

Atovaquone

Atovaquone is another second-line agent for PCP prophylaxis. Typically, dapsone is preferred over atovaquone because of favorable cost (104). There is also less RCT evidence for atovaquone as PCP prophylaxis compared to other regimens. One large RCT did compare atovaquone to dapsone and found no differences in all-cause mortality or PCP incidence (131). The overall rates of discontinuation because of an inability to tolerate the study drug also did not differ significantly between treatment groups (relative risk 0.94, 95% CI 0.74–1.19); however, among patients who were receiving (and presumably tolerating) dapsone at entry into the study, the switch to atovaquone was less well tolerated (RR 3.78; 95% CI 2.37–6.01). In another study, compared to AP, there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality or the incidence of PCP with atovaquone (132); however, there was an increased risk of discontinuation due to toxicity with atovaquone, predominantly related to rash or diarrhea.

Atovaquone is recommended by the guidelines at a dosage of 1,500 mg daily, although an RCT comparing 1,500 mg vs 750 mg of atovaquone found no significant differences in all-cause mortality, incidence of PCP, and discontinuation due to toxicity (132). It is postulated that atovaquone with or without adjunctive pyrimethamine will cross-protect against toxoplasmosis; however, this is largely extrapolated from trials using atovaquone as treatment for toxoplasmosis (133). It is worth noting that there have been reports of prophylaxis failure in cases of solid organ transplant that have been related to regional pockets of resistance (134). For optimal absorption, atovaquone should be prescribed with a moderately fatty meal (135), and notably, some drugs can decrease its absorption (e.g., rifabutin or efavirenz). It may not be an ideal agent for prophylaxis among people who have food insecurity, due to poor bioavailability.

The overall tolerability of atovaquone is inferior to AP (131, 132). As previously mentioned, the most common AEs on atovaquone are gastrointestinal, including nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, and hypersensitivity reactions (131, 132).

Aerosolized pentamidine

AP is the final guideline-recommended second-line agent for the prophylaxis of PCP (7, 104). AP has similar efficacy to DBRs and atovaquone but inferior efficacy to TMP-SMX in the prevention of PCP, especially when used as secondary prophylaxis or in patients with CD4 counts of <100 cells/µL (103, 110, 121, 126, 132, 136, 137). Unlike TMP-SMX, AP does not cross-protect against toxoplasmosis nor bacterial infections (110, 136, 137). The only guideline-recommended AP regimen is 300 mg monthly administered via a nebulizer (7, 104). Doses smaller than 300 mg have inferior efficacy in the prevention of PCP (138). There is one RCT that suggested that biweekly dosing of AP had superior efficacy compared to monthly, without a significant difference in AEs (139).

The compliance and tolerability of AP are superior to other regimens for PCP prophylaxis. Indeed, the risk ratios of discontinuation due to toxicity of TMP-SMX and DBRs compared to AP are 7.2 (95% CI 5.2–9.8) and 4.3 (95% CI 2.2–8.3), respectively (103, 121). Bronchospasm and cough during administration are the most common AEs (127). Despite these advantages, practical considerations, such as the need for specialized personnel and equipment, and the potential for transmission of respiratory pathogens during administration (140) limit the utility of AP. Moreover, because the effect of AP is local to the lung parenchyma, there is an increased risk of isolated apical disease or extrapulmonary PCP compared to systemic regimens (52).

Other regimens

Intravenous pentamidine

The use of monthly infusions of pentamidine (4 mg/kg maximum 300 mg) as pneumocystis prophylaxis has been explored in people without HIV, particularly allogeneic stem cell transplantation. This regimen offers the advantages of less hematologic toxicity compared to some other regimens and avoids the challenges of aerosolized delivery. In a systematic review and meta-analysis within a population without HIV (141), the pooled incidence of breakthrough PCP was 0.7% (of 3,025 patients); AEs were 11.3% (of 2,068 patients); and discontinuation due to AEs was 2.0% (of 1,182 patients).

The data for PWH are much more limited (142, 143). In the largest case series of 37 patients who received at least three doses of intravenous (IV) pentamidine as primary prophylaxis (387 patient-months of follow-up), there were no cases of PCP, nor any severe side effects. A similar case series was conducted for 47 patients who received intramuscular pentamidine monthly for primary prophylaxis where there were no episodes of breakthrough PCP in 350 patient-months of exposure (144).

Rezafungin

The recently approved long-acting echinocandin, rezafungin, has shown promise in preventing pneumocystis in murine models (145) and is the subject of a currently recruiting RCT for the prevention of invasive fungal infection (including PCP) in patients with allogeneic blood and marrow transplants (NCT04368559). As PWH are excluded from this study, it may be worth replicating in this population if it proves to be efficacious.

Discontinuing primary prophylaxis

Many HIV guiding bodies now suggest that discontinuation of primary PCP prophylaxis is possible when the CD4 count is >100 cells/µL; the HIV VL is undetectable for 3–6 months, and there is adherence with ART (5, 7). These recommendations are based on the understanding that lower VLs reflect a more robust immune system function and decreased risk or OIs, independent of CD4 count (38, 146). A large cohort study, the Opportunistic Infections Project Team of the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research in Europe (COHERE) (147) studied data from 23,412 patients (12 cohorts) who were taking ART after 1997. The authors used Poisson regression to model incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of primary PCP according to VL and CD4 count of ≤100 cells/µL or 100–200 cells/µL. There were 253 cases of PCP during 107,016 person-years of follow-up. Prophylaxis reduced the incidence of PCP among patients with a CD4 cell count of ≤100 cells/µL (adjusted IRR 0.41, 95% CI 0.27–0.60) but not among those with CD4 counts of 101–200 cells/µL (adjusted IRR 0.63, 95% CI 0.34–1.17). Among patients who discontinued prophylaxis after starting ART, there were 0 cases of PCP per 1,000 patient-years of follow up among those with a current CD4 cell count of 101–200 cells/µL and who were receiving ART. A recent target trial emulation using the COHERE data suggested that one might even discontinue primary prophylaxis regardless of CD4 count when the VL was suppressed on two consecutive measurements (148).

There has been at least one small RCT which randomized 74 patients with suppressed VLs and CD4 of <200 cells/ µL (149). In this non-inferiority study, participants were randomized to either continue or discontinue prophylaxis. One episode occurred in the discontinuation group (1.57 per 1,000 patient-months) vs 0 in the continuation group. This met the pre-specified 10% non-inferiority margin at 1 year. However, there is likely a need for further RCTs in this domain.

Clinical judgment and patient-centered care decision models are required. This is especially important in the context of patients who may have difficulty adhering to ART secondary to side effects, polypharmacy, drug interactions, and certain psychosocial determinants of health. This is also relevant for those PWH whose CD4 count at the time of ART initiation is expected to never recover above >200 cells/µL, making timing of discontinuation of prophylaxis uncertain. In some settings, there may be additional benefits afforded by TMP-SMX prophylaxis, such as the prevention of malaria and diarrheal infections (150, 151).

Discontinuing secondary prophylaxis

It has been observed that PWH who have had a prior episode of PCP may be at an increased risk of acquiring the infection again; prior to ART, past infection was described as a risk factor for recurrent infection (38). In 1991, among a population of patients on no ART or receiving zidovudine monotherapy, recurrent PCP occurred in 27 of 78 (35%) of patients who received placebo secondary prophylaxis compared to 5 of 84 (6%) of patients who received aerosolized pentamidine secondary prophylaxis (152).

PCP may recur among PWH who have been treated for an initial infection due to the presence of residual P. jirovecii cysts (18, 19). Alternatively, patients who do not adhere to prophylaxis and/or to ART may develop a new infection. Some studies have looked at the risk of recurrent PCP following discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis. One study included 660 PWH who sought care between 1997 and 2007 at a university affiliated hospital in Taiwan with a CD4 count of <200 cells/µL (153). From this sub-population, 216 patients received secondary prophylaxis against PCP; 145 stopped the prophylaxis prior to achieving a CD4 count of 200 cells/µL or greater; and 6 patients developed recurrent PCP [incidence of 2.49 (95% CI 0.91–5.42) per 100 person-years]. All six cases were among patients with poor adherence to ART and with evidence of virologic failure. Among the 71 patients who continued prophylaxis until their CD4 count was greater than 200 cells/µL, there was 1 case of PCP [incidence of 0.48 [95% CI 0.01–2.65) per 100 person-years, P value 0.13], suggesting an increased risk from stopping prophylaxis early. That said, this was a retrospective study with several limitations and potential confounders including immortal time bias.

Other studies have not observed an increased risk of PCP infection upon discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis, though always under specific and ideal clinical circumstances. One case series out of Spain included 29 patients who had their secondary PCP prophylaxis discontinued following introduction of ART for 3 months when their CD4 count was ≥100 cells/µL and their VL was <500 copies; during a follow-up period of 18 months, only one person developed PCP, in the context of discontinuing ART for 6 weeks (154). A prospective observational multicenter study looked at discontinuing secondary prophylaxis among 79 PWH treated with ART with a CD4 count of at least 200 cells/mm3 and 14% of total lymphocytes, measured twice and at least 3 months apart (155). Over a median follow-up of 40.2 months, there were no cases of PCP. A larger prospective study derived from eight European cohorts by Ledergerber et al. was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2001 (156). The study included 325 PWH on ART (three drugs) and a CD4 count of at least 200 cells/mm3 on one occasion. No cases of PCP were diagnosed following discontinuation of prophylaxis during a median follow-up of 13 months, while the CD4 count was maintained at or above 200 cells/mm3. Another small prospective cohort study also found zero cases in a similar population of patients who had secondary prophylaxis discontinued (157). A particularly large cohort study of 10,476 patients across Europe (from COHERE) with a follow up time of 74,295 patient-years at risk of secondary PCP reported an overall incidence of 5 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI 4.5–5.6 per 1,000 person-years) (158). There were 373 secondary PCP events between 1998 and 2015. Patients with a CD4 count of 100–200 cells/µL plus low VL (<400) experienced a comparable incidence of recurrent PCP, irrespective of whether they had been receiving secondary prophylaxis (3.9 person-years, 95% CI 2.0–5.8 not on prophylaxis compared to 1.9 person-years, 95% CI 0.1–3.7 on prophylaxis).

An RCT was published in 2001 (159) wherein 113 patients receiving secondary prophylaxis were randomized to continuation (N = 63) or discontinuation (N = 60). All patients were receiving ART, had a CD4 count of 200 cells/µL or greater, and a VL less than 5,000 copies/mL for 3 months. There were no cases of PCP over a median of 12 months of follow-up (95% CI 0–4.57 per 100 patient-years). Another RCT published in 2003 (160) examined discontinuation of PCP prophylaxis with a longer follow-up period. To be included, patients had to have a CD4 count of >200 cells/µL and to be receiving ART for at least 3 months. This study included 146 patients, of whom 77 were randomized to the discontinuation arm. Recurrent PCP was rare, with only two cases over 2 years of follow-up both occurring in the discontinuation arm. As discussed earlier, a small (N = 74) RCT randomized patients to discontinuation of prophylaxis for OIs if the CD4 count was <200 cells/µL, so long as the VL was suppressed on ART for at least 6 months (149). A sub-group was randomized to discontinuing secondary prophylaxis for PCP (N = 10) or continuing (N = 15). One patient in the study developed PCP while off prophylaxis, but it was not mentioned whether this was in the sub-group who stopped primary or secondary prophylaxis, nor what the baseline CD4 count was.

Overall, the recent data support a risk-stratified approach based on VL and CD4 count, aiming to balance the harms and benefits from available prophylaxis options. Discontinuing secondary prophylaxis for patients on ART with an adequate immune response (CD4 count of ≥200 cells/µL for ~3 months) or ≥100 cells/µL with a sustained suppressed VL appears reasonable. Recurrence in this population appears to be rare but has been described, so symptomatic patients may still require investigation, especially if ART has been interrupted.

While this recommendation may be suitable in a well-resourced environment (e.g., high-income countries) with sufficient access to ART and supportive care, it may not be applicable to resource-limited settings where the context of HIV epidemiology and OIs is different. Again, there may be specific additional benefits afforded by TMP-SMX against malaria and severe bacterial infections according to local prevalence (150, 151).

Restarting prophylaxis

With the above evidence base in mind, re-initiation of primary/secondary prophylaxis can be considered when the CD4 count drops below <100–200 cells/µL and depending on whether the VL is suppressed or not. Clinical judgment is needed for periods where ART may be stopped, and/or there is an increasing VL, to assess when prophylaxis should be restarted.

The preferred option for secondary prophylaxis is TMP-SMX with alternatives as discussed in the primary prophylaxis section.

TREATMENT

Estimating the therapeutic threshold

In general, attempts should be made to confirm the diagnosis of PCP prior to the initiation of therapy. This is because (i) all drugs have some toxicity, and (ii) patients with PCP may worsen before they get better, and an incorrect PCP diagnosis could delay arriving at a timely correct diagnosis. Nonetheless, it is recognized there will be cases where empiric therapy is required. In such cases, some form of quality diagnostic testing will ideally be pending at the time therapy is initiated (see Diagnosis).

Likewise, there will be cases where missing or delaying the diagnosis will have greater harm than incorrectly initiating empiric therapy. In such cases, the threshold to stop investigating may be different. For instance, a post-test probability of 10% may be acceptable to stop investigating for the disease in patients who are on minimal or no oxygen, whereas a threshold of 3%–5% may be more appropriate in patients who are critically ill. Often decisions surrounding empiric therapy and cessation of testing will be similar.

Antifungal therapies

Table 3 compares different regimens for treatment, doses, and adverse events of note.

TABLE 3.

Treatment regimens for PCPa

| Drug name | Dose | Notes | Adverse drug events and side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole | 15–20 mg/kg/day of the trimethoprim component po or IV (divided) | 10 mg/kg/day (divided) of the trimethoprim component may offer similar efficacy and reduced toxicity | Rash (including Stevens-Johnson syndrome), hyperkalemia, increased creatinine, transaminase elevation, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia |

| Clindamycin with primaquine | Primaquine: 30 mg po once daily Clindamycin: 900 mg IV or 600 mg po every 8 hours |

Screen for G6PD deficiency prior to use | Primaquine: rash, fever, GI distress, methemoglobinemia, and hemolytic anemia Clindamycin: rash, diarrhea (including, Clostridium difficile), and abdominal pain |

| Dapsone with trimethoprim | Trimethoprim: 5 mg/kg po every 8 hours Dapsone: 100 mg po daily |

Availability of single formulationtrimethoprim may limit use; N.B. dapsone is a sulfone. Screen for G6PD deficiency prior to use |

Trimethoprim: rash, gastrointestinal upset, transaminase elevation, neutropenia, increased creatinine, and hyperkalemia Dapsone: rash, fever, nausea/vomiting, methemoglobinemia, hemolytic anemia, and transaminase elevation |

| Atovaquone | 750 mg po twice daily | Take with a fatty meal to increase absorption. Pockets of resistance are described. Can be expensive and has an unpleasant taste. Increased mortality compared to TMP-SMX. Drug-drug interactions can lower the efficacy |

Gastrointestinal upset, diarrhea, fever, transaminase elevation, and rash |

| Pentamidine | 4 mg/kg IV once daily | Can be toxic to pancreatic islet cells. Toxicity appears to be dose and duration dependent (over 1 g cumulative, occurs after about 3 weeks of treatment) |

Pancreatitis, abdominal pain, acute kidney injury, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia |

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IV, intravenous; N.B., nota bene; po, per os; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

TMP-SMX is the mainstay of therapy for PCP (4). TMP-SMX works in combination to inhibit the folic acid pathway; sulfamethoxazole accomplishes this through direct competition of p-aminobenzoic acid during the synthesis of dihydrofolate via inhibition of the enzyme dihydropteroate synthetase. Similarly, TMP competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, an enzyme further down the pathway, ultimately halting the transformation of tetrahydrofolate to its active form of folate. Thus, in synergy, the two agents block the bacterial biosynthesis of essential nucleic acids and proteins. Sulfamethoxazole is hepatically metabolized by the CYP450 system, whereas TMP is primarily excreted in the urine (161, 162).

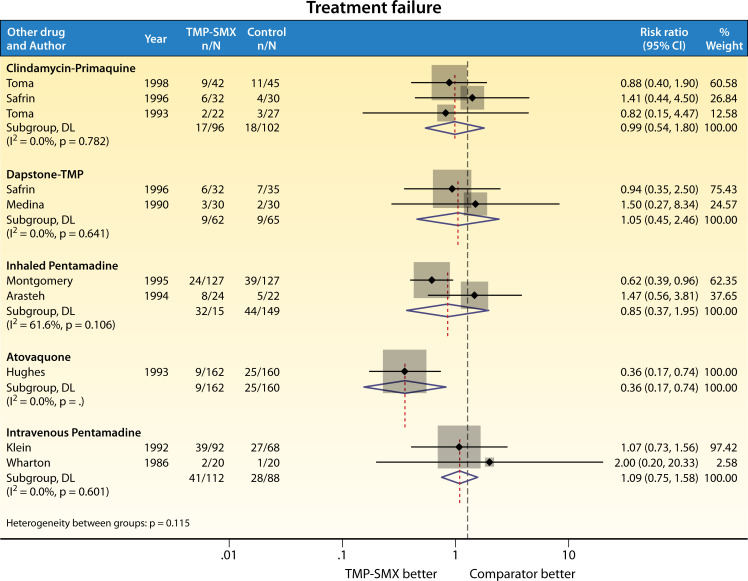

One of the earliest studies of TMP-SMX for the treatment of PCP was conducted in 1975 among 14 children with leukemia (163). Since then, the therapeutic efficacy of TMP-SMX has been tested in RCTs, almost exclusively in the HIV population (Fig. 2 and 3). Most of these trials were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s (4), with the most recent trial published in 1998 (164). The first head-to-head clinical trial took place in 1986, included 40 patients with AIDS, and compared TMP-SMX (20 mg/kg of TMP component) with intravenous pentamidine (165). Wharton et al. reported a mortality rate of 25% in the TMP group and 5% in the pentamidine group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = 0.09). Following this, three other trials compared pentamidine to TMP-SMX; Arasteh et al. (166) (inhaled pentamidine) and Klein et al. (167) (intravenous pentamidine) reported similar rates of survival between the two groups. One other study (168) compared a lower dose of TMP-SMX (15 mg/kg of TMP) to aerosolized pentamidine; the authors found no difference in mortality, and while fewer patients in the TMP-SMX group required a change in therapy due to lack of efficacy, it was more common for TMP-SMX to be discontinued because of toxicity.

Fig 2.

RCT comparison of TMP-SMX vs other agents for treatment of PCP: treatment failure.

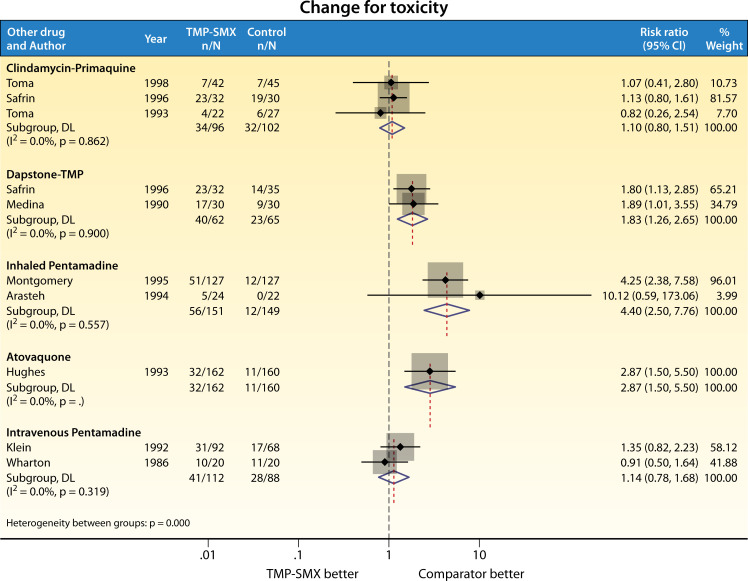

Fig 3.

RCT comparison of TMP-SMX vs other agents for treatment of PCP: change of therapy due to toxicity.

Compared to dapsone-TMP, two RCTs found no mortality difference between dapsone-TMP and TMP-SMX (169, 170). The same was noted for clindamycin-primaquine (164, 170, 171). By contrast, atovaquone was less effective in a multicenter trial of 322 patients with AIDS (172) [RR for treatment failure 0.36 (95% CI 0.17–0.74), favoring TMP-SMX]. In this study, mortality was also reduced with TMP-SMX [RR 0.09 (95% CI 0.01–0.69)], despite a greater proportion of patients (20% vs 7%) requiring a change in therapy due to treatment-limiting adverse effects of TMP-SMX.

While TMP-SMX is the de facto treatment of choice at a dose of 15–20 mg/kg/day in divided dosing, this regimen has not been proven to be superior to other dosing regimens, nor other standard of care therapies, and treatment at the guideline recommended dose can be limited by toxicities (Fig. 2 and 3). Treatment failure in these studies was defined variably but included elements such as clinical deterioration, change in therapy for failure to respond, progression to mechanical ventilation, and/or death (4). Of note, patients with severe PCP were poorly represented. Among 9 RCTs comparing TMP-SMX with other standard of care treatment regimens for PWH (clindamycin-primaquine, dapsone-TMP, or pentamidine), one trial was stopped early due to toxicity in the TMP-SMX group (168). Among all trials that compared TMP-SMX to other treatments, toxicity rates requiring change in therapy for TMP-SMX ranged between 20% and 57% (Fig. 3). Common treatment-limiting AEs from TMP-SMX include neutropenia, hyperkalemia, and rash (173, 174).

No randomized trial to date has compared efficacy, toxicity, and tolerability between lower dose (e.g., 10 mg/kg/day divided) and standard dose (e.g., 15–20 mg/kg/day divided) TMP-SMX; however, a systematic review of observational studies assessing safety and tolerability of lower-dose TMP-SMX found lower AEs without increased mortality (175). Of note, there was little representation of patients with severe organ dysfunction among the included patients. Adding leucovorin to mitigate hematologic toxicity is not advisable as the one RCT of this strategy showed increased mortality compared to TMP-SMX alone (176)

Clindamycin-primaquine

Clindamycin-primaquine was first investigated for tolerability and efficacy as primary treatment of PCP in the late 1980s and early 1990s (177–179). Three independent head-to-head RCTs have since assessed the efficacy of clindamycin with primaquine for the treatment of mild/moderate PCP among PWH (164, 169, 171). Toma and colleagues compared 45 patients receiving clindamycin-primaquine with 42 receiving TMP-SMX and reported no difference in efficacy or mortality, but fewer side effects were reported with the use of clindamycin-primaquine (171). Similarly, Safrin and colleagues noted no difference in the efficacy of clindamycin-primaquine as compared to either dapsone or TMP-SMX, but did note a greater degree of hematologic toxicity among those treated with clindamycin-primaquine (169). Combined AEs of grade III or IV neutropenia or anemia, platelet count less than 50 × 109 /L, or methemoglobin levels of 15% or greater occurred in 11% of patients treated with TMP-SMX, 12% of dapsone-TMP recipients, and 28% of clindamycin-primaquine recipients. Use of clindamycin-primaquine as salvage therapy following failure of TMP-SMX (due to either toxicity or lack of efficacy) has not been evaluated in RCTs; however, retrospective cohort studies do suggest this is a viable option. In a meta-analysis of salvage therapies for PCP (trials, case series, and case reports), clindamycin-primaquine was a commonly used second-line treatment, and there was a good response observed in most of the 48 patients who were treated with it (180). A more recent retrospective analysis of patients who had failed first-line treatment of PCP with TMP-SMX or atovaquone also found that clindamycin-primaquine was effective in 16 out of 18 (89%) of patients treated. Of note, the drug is not licensed for the treatment of PCP in some countries (including Japan, where the study took place, and the drug was imported for compassionate use) (181). Testing for G6PD deficiency should be performed, given the risk of hemolytic anemia. Methemoglobinemia due to primaquine can also rarely occur and should be recognized.

Dapsone-trimethoprim

Dapsone (diaminodiphenyl sulfone), used in combination with TMP, is another second-line agent for mild-to-moderate PCP. Dapsone was initially used as an antibacterial treatment for leprosy in the 1940s and was later used to treat PCP and toxoplasmosis (182). The mechanism of action of dapsone is similar to SMX, whereby dapsone inhibits folate synthesis by competing with para-aminobenzoic acid for the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase (183). Two RCTs conducted in the 1990s found that dapsone-TMP exhibited similar efficacy to TMP-SMX or clindamycin-primaquine in PWH with mild-to-moderate PCP (169, 170). Patients treated with dapsone-TMP exhibited higher rates of asymptomatic methemoglobinemia but lower occurrences of adverse effects including hepatitis, neutropenia, and hyperkalemia, when compared to the group treated with TMP-SMX (30% vs 57%) (170). Additionally, Safrin et al. found that dapsone-TMP treatment was associated with less frequent hematologic toxicity than the clindamycin-primaquine treated group (12% vs 28%) (169). Despite demonstrated efficacy and few side effects, dapsone is less often used as an alternative therapy for PCP due to the limited availability of single-formulated TMP and concerns surrounding sulfa-allergy. G6PD deficiency testing should be performed, and the risk of methemoglobinemia should be recognized (130).

Pentamidine

Prior to the use of TMP-SMX, intravenous pentamidine was used as the initial treatment option for moderate-to-severe PCP (182). The use of pentamidine is often limited to cases of severe PCP after failure to respond to first-line therapies due to its perceived toxicities. Pentamidine is an aromatic diamidine compound consisting of pentane-1,5-diol. It disrupts polyamine synthesis, inhibits RNA polymerase activity, penetrates the protozoal cell by binding to transfer RNA, and hinders the production of proteins, nucleic acids, phospholipids, and folate. Since its mechanism of action involves protein and RNA synthesis inhibition, pentamidine exerts toxic effects on multiple organs (184).

RCTs have shown that intravenous pentamidine is comparably effective to alternative therapies for treating PCP in PWH. Specifically, when compared with TMP-SMX, intravenous pentamidine demonstrated similar efficacy and safety to 20 mg/kg of TMP-SMX in two head-to-head trials (165, 167). Furthermore, pentamidine has exhibited comparable clinical efficacy to oral atovaquone, although it has significantly higher rates of adverse effects (185). Daily use is associated with a risk of pancreatitis after about 3 weeks and a cumulative dose of 1 g (186). Pancreatitis may be preceded by hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, renal insufficiency, and/or non-specific abdominal pain (187).

Comparatively, the use of pentamidine in the aerosolized form is associated with fewer side effects due to its lower systemic absorption. However, it may be less effective than alternative treatments, particularly in patients with severely impaired respiratory function (188). RCTs comparing aerosolized and intravenous pentamidine have demonstrated that aerosolized pentamidine is either comparable or slightly inferior in terms of effectiveness for mild-to-moderate PCP (189, 190). Other RCTs have shown that patients treated with aerosolized pentamidine have fewer side effects compared to those treated with TMP-SMX (166, 168). However, aerosolized pentamidine was less efficacious than TMP-SMX in terms of clinical response in the trial by Montgomery et al. (168). Due to its reduced efficacy and increased risk of relapse, aerosolized pentamidine is not frequently used to treat PCP.

Atovaquone

Atovaquone, administered orally, is a second-line therapy for mild-to-moderate PCP.

Atovaquone works by inhibiting the binding of ubiquinone to cytochrome c, thus disrupting the electron transport chain and leading to mitochondrial breakdown (191). Atovaquone has a favorable side-effect profile in that it can be used for G6PD-deficient patients who cannot tolerate primaquine, sulfamethoxazole, or dapsone (182). However, in the one head-to-head RCT that included PWH with mild-to-moderate PCP, atovaquone exhibited lower efficacy compared to TMP-SMX, as indicated by a higher rate of treatment failure [20% vs 7%; RR 0.36 (95% CI 0.17–0.74), in favor of TMP-SMX] and higher mortality [7% vs 0.06%; RR 0.09 (95% CI 0.01–0.69), in favor of TMP-SMX] (172).

When compared to intravenous pentamidine in another RCT, atovaquone had a non-significantly higher rate of treatment failure [27% vs 17%; RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.23–1.23), in favor of pentamidine] but not mortality [7% vs 13% RR 1.85 (95%CI 0.57–6.0), in favor of atovaquone], with fewer side effects (185).

Successful PCP treatment outcomes with atovaquone in HIV patients have been positively correlated with atovaquone serum levels, whereas its effectiveness has been observed to be reduced in patients with diarrhea or conditions that reduce atovaquone absorption (172). It is therefore recommended to take the medication with food containing moderate fat content to improve the bioavailability and to ensure an adequate serum concentration (135, 192). It is not an ideal choice for patients who are on nil per os orders, for example. Additionally, it is not recommended to combine atovaquone with medications that lower the serum levels such as rifampicin, rifabutin, boosted atazanavir, and efavirenz (182).

Echinocandins

While TMP-SMX is highly efficacious even for severe PCP, not all patients tolerate it well (see Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole under Treatment above). There is now emerging evidence based on small observational studies and case reports on the efficacy of echinocandin antimicrobials in treating HIV-associated PCP (193) in combination with another agent (194, 195) or as monotherapy (196, 197). Echinocandins target cell membrane BDG, both in fungi (the usual indication for echinocandins) and potentially in P. jirovecii (see (1,3)-Beta D-Glucan under Indirect testing). Importantly, they are well tolerated by patients and have few interactions with other medications (198). However, while this could represent an interesting new approach to PCP treatment, the data remain sparse, and randomized trials are required before adoption.

Duration of treatment

While treatment with TMP-SMX (and indeed all regimens) is generally for 21 days, this is mainly based on historical practice. A single retrospective study conducted in 1984 compared 49 episodes of PCP in PWH to 39 episodes in patients with other immunosuppressive diseases and found that PWH were symptomatic for longer (a median of 28 days vs 5 days) (199). Treatment duration in this study varied (typically 10–14 days but in some cases longer), and 40% of patients were changed from TMP-SMX to pentamidine, or else pentamidine was added, for suspected treatment failure or adverse drug events. This study was not designed to compare treatment durations; however, it has been referenced in the guidelines to support a treatment duration of 21 days. All RCTs of PCP treatment have only ever studied a 21-day course (for all agents). A shorter course (14 days) or a dose reduction for days 15–21 might be reasonable, especially if the patient is clinically improved and/or there is concern for toxicity (200).

Adjunctive steroids

The rationale for using adjunctive corticosteroids stems from pulmonary inflammation which occurs during infection and can indeed worsen early in the treatment of PCP. Systemic corticosteroids are often prescribed to limit possible progression to respiratory insufficiency, intubation, and death. For a long time, clinicians have prescribed adjunctive steroids early in the course of the disease for patients with moderate to severe PCP who meet certain criteria, including a PaO2 of <70 mmHg or a widened A-a gradient.

A Cochrane systematic review (with a published update in 2015) analyzed the efficacy of adjunctive corticosteroids compared to placebo or standard of care (201). The review comprised seven studies of PWH who exhibited moderate-to-severe PCP and substantial hypoxemia, and six of the studies were meta-analyzed, totaling 489 adults. Combined analysis revealed that adjunctive corticosteroid therapy significantly reduced 1-month mortality when combined with standard treatment (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32–0.98). Analysis of the three largest trials, involving a total of 388 adults, found the need for mechanical ventilation was reduced through the use of adjunctive corticosteroids at 1 month (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.2–0.73). The usual steroid chosen is prednisone, which is prescribed as 40 mg orally twice daily for days 1–5, 40 mg once daily for days 6–10, and 20 mg once daily for days 11–21 (202). It is unclear whether other steroids [e.g., hydrocortisone, which has proven effective for severe community-acquired pneumonia (203) or dexamethasone, proven effective for severe COVID-19 (204)] might be as good as or better than prednisone or if the full 21-day regimen is required if the patient has substantially recovered.

Timing of antiretroviral therapy in PCP

An important consideration in the treatment of PCP in patients with untreated HIV is to determine the optimal time to start ART. The largest trial comparing early ART (within 14 days of OI diagnosis) to deferred ART was the A5164 trial (205). It comprised 283 participants of whom 177 had PCP at enrollment. At 48 weeks of follow-up, the combined outcome of AIDS progression or death happened in 14.2% of early ART recipients, and in 24.1% of deferred ART recipients (P = 0.035). Viral load and CD4 counts did not differ in either arms of the trial, and there were no differences in rates of ART interruptions/switches, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromes, hospitalizations (and length of hospitalization), or other AEs. Not surprisingly, early ART also led to shorter time to CD4 count above 50 cells/µL. Hence, the results of A5164 support an early ART start in cases of PCP, in contrast with other OIs such as cryptococcal meningitis (206–208) and tuberculous meningitis (209), in which early ART has been associated with worse outcomes.