Abstract

The heat shock response (HSR) is a crucial biochemical pathway that orchestrates the resolution of inflammation, primarily under proteotoxic stress conditions. This process hinges on the upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSPs) and other chaperones, notably the 70 kDa family of heat shock proteins, under the command of the heat shock transcription factor-1. However, in the context of chronic degenerative disorders characterized by persistent low-grade inflammation (such as insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular diseases) a gradual suppression of the HSR does occur. This work delves into the mechanisms behind this phenomenon. It explores how the Western diet and sedentary lifestyle, culminating in the endoplasmic reticulum stress within adipose tissue cells, trigger a cascade of events. This cascade includes the unfolded protein response and activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein-3 inflammasome, leading to the emergence of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype and the propagation of inflammation throughout the body. Notably, the activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein-3 inflammasome not only fuels inflammation but also sabotages the HSR by degrading human antigen R, a crucial mRNA-binding protein responsible for maintaining heat shock transcription factor-1 mRNA expression and stability on heat shock gene promoters. This paper underscores the imperative need to comprehend how chronic inflammation stifles the HSR and the clinical significance of evaluating the HSR using cost-effective and accessible tools. Such understanding is pivotal in the development of innovative strategies aimed at the prevention and treatment of these chronic inflammatory ailments, which continue to take a heavy toll on global health and well-being.

Keywords: HSP70, Heat shock response, Chronic inflammatory diseases, Obesity, Insulin resistance, Exercise

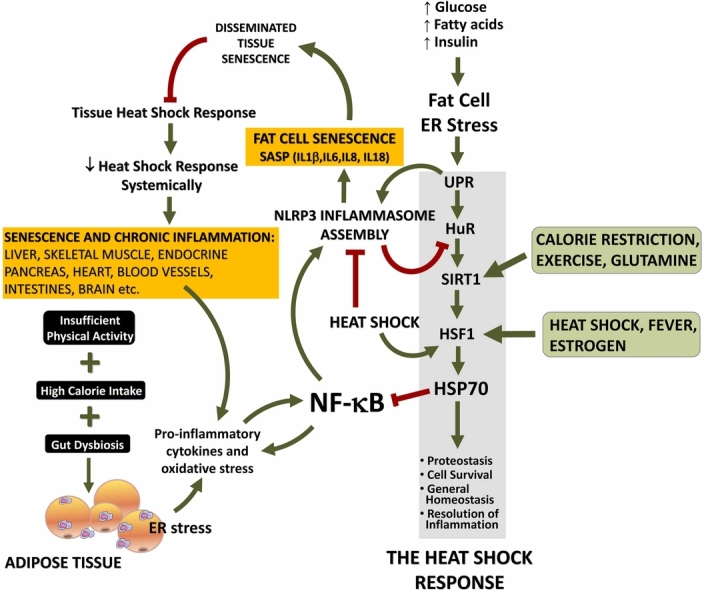

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Chronic metabolic diseases with inflammatory underpinnings have become prevalent due to the Western lifestyle characterized by high-calorie intake, intestinal dysbiosis, and sedentary behavior. Conditions like obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and neurodegenerative diseases now collectively account for a staggering 74% of global deaths.1

Transcriptional profiling studies have unveiled a prominent upregulation of genes associated with inflammatory and stress responses in the adipose tissue of obese individuals.2 In this Western lifestyle, excessive nutrient intake, coupled with insufficient energy expenditure3 or skeletal muscle-derived myokines4, 5, 6 to balance cell metabolism and appetite control,7 adipose cells experience endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Persistent ER stress perpetuates the unfolded protein response (UPR) and triggers the activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in adipose tissue. The ensuing release of inflammatory cytokines leads to a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), with NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent cytokines “seeding” inflammation throughout the body.3 This chronic ER stress-induced inflammation ultimately culminates in exacerbated insulin release, atherosclerotic vascular diseases, and other chronic inflammatory disorders due to the inability of the organism to resolve inflammation.3, 8 This begs the question: why does a state of low-grade inflammation persist in these metabolic diseases when vertebrates have evolved over millions of years to mount and resolve inflammatory responses? The answer lies in the progressive suppression of the heat shock response (HSR) by proliferative senescence in adipose tissue. The HSR, mediated by heat shock transcription factor-1 (HSF1)-dependent expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs) and other chaperones, is a potent anti-inflammatory pathway that becomes progressively suppressed by proliferative senescence under persistent ER stress and the succeeding NLRP3 inflammasome-driven SASP.3

In fact, proliferative senescence of adipose tissue precedes virtually all known forms of chronic degenerative diseases of inflammatory nature, whatever tissue location, from diabetes to CVD, from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to menopause-associated dysfunctions and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, Parkinson’s and most probably fibromyalgia, conditions in which the weakening of the HSR is always observed.9, 10 This story begins by exploring the convoluted link between intracellular chaperone-mediated protein quality control and inflammation. Over the course of billions of years, protein chaperones have evolved with the primary objective of preventing protein misfolding, averting the aggregation of misfolded proteins, and thus thwarting the accumulation of potentially cytotoxic complexes.11 Actually, although the lexicon “molecular chaperones” is widely recognized in the realm of HSPs, the term was originally coined by Laskey and co-workers12 to describe these proteins’ remarkable ability to prevent incorrect ionic interactions between histones and DNA. Anyway, in the context of a genuine HSR, molecular chaperones play a crucial role in guiding newly synthesized proteins to fold correctly into their functional three-dimensional structures. They effectively prevent aggregation and facilitate the precise localization of these polypeptides through transmembrane translocation. This function holds profound significance in the context of low-grade inflammation, as misfolded proteins or their aggregates exacerbate ER stress (referred to above), thereby triggering inflammatory signals throughout the body, as we shall elaborate upon.

When the HSR experiences irreparable dysfunction, such as when misfolded proteins cannot be salvaged or destroyed, cells have the option to enter apoptosis, effectively halting the generation of inflammatory signals originating from the ER. Conversely, in less severe scenarios where cells do not undergo apoptosis but persistently experience ER stress, they may enter a state of senescence and develop SASP. Therefore, the HSR emerges, on the one hand, as a safeguard of proper functioning within the chaperone machinery that serves to mitigate UPR and, on the other hand, as a potent anti-inflammatory pathway, as we shall elucidate below. Furthermore, the HSR intricately connects protein homeostasis with energy metabolism through interactions between HSF1 and 5'-adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an occurrence referred to as “caloristasis.”13 Disrupting this delicate equilibrium between proteostasis and energy metabolism can culminate in the formation of aberrant protein aggregates that serve as catalysts for chronic inflammation.

Within the HSP superfamily, the 70 kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) family, hereafter referred to as HSP70, plays a pivotal role in obviating protein misfolding and inflammation.10, 14, 15 For the sake of clarity, as outlined in Schroeder et al.,16 HSPs are currently categorized into gene families and superfamilies, aligning more consistently with the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee, as indicated by Kampinga et al.17 These include HSPA (e.g., HSP70s), HSPB (small HSPs), HSPC (e.g., HSP90), HSPD, and HSPE (HSP60 and HSP10 chaperonins), HSPH (e.g., HSP110), DNAJ (J-proteins, formerly HSP40 cochaperones18), alongside CCT and other chaperonin-related genes. In relation to HSP70s, up to now, the human genome has identified 13 different genes coding for members of the HSPA/HSP70 superfamily, such as cytoplasmic/nuclear HSPA1A/HSP72 and HSPA1B/HSP70-2, ER-based HSPA5/GRP78, and mitochondrial HSPA9/GRP75. Despite the considerable homology within this superfamily, HSPA/HSP70s members exhibit a high degree of specialization. For instance, the response to stress can vary significantly; HSPA8/HSC73 (formerly known as the cognate form of HSP70), expressed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus,19 primarily functions as a non-inducible housekeeping gene. In contrast, HSPA6/HSP70B’ demonstrates strictly inducible expression, with minimal or no basal expression in most cells. Actually, there is a vast repertoire of combinations of intracellular location and inducibility among HSP members.20 In this work, however, our primary focus will be on the HSPA1s/HSP70s-based anti-inflammatory HSR and its gradual suppression as chronic inflammatory diseases unfold unless stated otherwise.

HSR at the organismal level: Beyond cellular proteostasis to transcellular signaling, intermediate metabolism, and whole-body homeostasis regulation

The HSR serves primarily a protective function within cells, but it also evolved to encompass organism-level situations that threaten homeostasis. One such situation is the release of extracellular HSP70 (eHSP70) into the plasma during various stressful conditions (as described below). Indeed, eHSP70 is essentially a composite of both HSP72 (HSPA1A and HSPA1B) and HSP73 (HSPA8) proteins,21 which may be released in exosomes during stressful situations.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Unlike intracellular HSP70, which functions as a protein chaperone and anti-inflammatory factor inside the cells, eHSP70 acts as a danger signal and pro-inflammatory cytokine through its interaction with Toll-like 4 receptors outside the cells.25, 27, 28, 29, 30 In simple terms, eHSP70 may be produced by a stressed tissue (e.g., during exercise) but eventually acting in others, that is, brain and immune system cells.25, 26 This narrative, however, transcends its current boundaries. As expounded by Schroeder et al.,16 our present understanding of HSF1 activation encompasses four distinct mechanisms, with one of them being cell-nonautonomous (a process initiated not by the stressed cell itself, but rather originating externally, in contrast to the cell-autonomous mechanism) which unfolds within the cell in response to stress signals directed at the cell. This revelation gained prominence following the groundbreaking discovery by Professor Rick Morimoto’s research group, shedding light on a previously unforeseen avenue of HSR activation: the transcellular, cell-nonautonomous regulation of HSF1.31 Accordingly, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans exhibits HSR in a way dependent on thermosensory neurons that detect changes in ambient temperature. As with humans, these specialized neurons exist that play unique roles in controlling temperature-related behavior.10, 32 As a consequence of this relative loss of cellular autonomy in triggering HSF1 activation, the HSR can be attained by the integration of stress-related, metabolic, and behavioral responses of the animal in order to establish a coordinated organismal response to environmental fluctuations.31

Transcellular HSR activation is now accepted not to be a peculiarity of C. elegans, but a mechanism conserved among metazoans, including mammals.33, 34 This highly elaborated mechanism enables the integration of the HSR across multiple cellular compartments, including the cytoplasm, nucleus, ER, and mitochondria. This is achieved by metabolic adjustment of cell growth, insulin-dependent, and antioxidant factors, which help to compensate for changes in proteostatic load in response to environmental fluctuations.34 Hence, it became clear that multicellular organisms require the coordination between stress responses and the maintenance of proteostasis, which cannot be achieved through cell-autonomous mechanisms alone. Contrarily, they must be orchestrated in a cell non-autonomous manner through centralized control of the nervous system.35, 36, 37, 38 Remarkably, in C. elegans, upregulation of the HSP70 gene (hspa1a) through transcellular chaperone signaling (TCS) has been found to increase resilience to heat stress through a unique molecular mechanism. Specifically, TCS is not regulated by the canonical HSF1-dependent HSR, and upon TCS activation, HSF-1-mediated HSR is remarkably suppressed. This favors an intercellular route, enabling the animal to preserve its survival. TCS represents an organismal stress response that activates HSP70 expression in an HSF1-independent manner.38

While every eukaryotic cell has the necessary machinery for the expression of heat shock genes, the regulation of the HSR through non-autonomous neuronal signaling to somatic tissues and TCS between neurons and peripheral tissues is a significant evolutionary advancement. This guarantees the coordinated activation of the organismal HSR across various tissues and can supersede neuronal control to restore cell-specific and tissue-specific proteostasis, while maintaining the overall homeostasis, including energy balance. Actually, these mechanisms pungently pinpoint an evolutionarily preserved homeostasis-protecting system at the organismal level that is added to caloristasis,16 the latter at the cellular level, contributing to the preservation of homeostasis. The understanding of the different metabolic pathways as well as neurotransmitters involved in mammal TCS is still in its infancy. Considering the integrative role of the HSR in responding to diverse intracellular and extracellular stressors, further research endeavors hold the promise of illuminating novel avenues toward a more detailed comprehension of this phenomenon.

In addition to the triggering of the HSR through cell-autonomous and cell-non-autonomous (TCS) mechanisms, there are other well-known mechanisms of HSR activation at the organismal level that attach the autonomic nervous system to the stress responses. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) branch of the autonomic nervous system serves as the primary conduit for protective responses against disruptions to homeostasis. Remarkably, this role extends not only to vertebrates but also seemingly across the entire metazoan spectrum.39 As one would anticipate, the evolution of the SNS is intricately linked to the integration of energy sensing mechanisms, encompassing responses to situations ranging from the “fight-or-flight” stress response to the regulation of core temperature, glucose homeostasis, and fat storage. Consequently, all the known stimuli that enhance SNS tone indisputably dictate the activation of the anti-inflammatory HSR. Not unexpectedly, SNS plays a proactive role in the mitigation (“resolution”) of one of the pivotal defensive responses of the animals: inflammation.40

The multifaceted interplay of plasma glucose concentrations, energy sensing, HSR, and sympathetic activity takes place within the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH). This neural hub integrates diverse functions, including feeding regulation, fear response, blood pressure, thermoregulation, and sexual activity. Furthermore, the VMH is the site of a notable estrogen-induced HSR.41, 42 Additionally, mechanisms within the hypothalamus, particularly in the preoptic area, that induce fever (an activator of the HSR) can be modulated by norepinephrine.32 In the context of hypoglycemia, it is noteworthy that acute episodes trigger the release of eHSP72 and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6.43 Importantly, glucose ingestion effectively inhibits the exercise (stress)-induced secretion of eHSP7044 and abolishes the counterregulatory actions of the SNS during hypoglycemic episodes.45 These effects are intricately mingled in the neuronal circuitry within the VMH.46

HSP70 expression can be induced by α-adrenergic stimulation in numerous tissues. Conversely, the HSR is impeded by α1-adrenergic blockade.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 Furthermore, acute stress stimulates the secretion of exosomes containing eHSP70 and augments circulating levels of eHSP70, all in an α-adrenergic-dependent manner. This ultimately serves as a warning to physiological systems of the presence of homeostasis-threatening situations.22, 23, 24, 25 Indeed, the HSR pathway has general protective functions and involves pathways that couple exercise, energy balance, and proteostasis to inflammation via HSP70 (Figure 1). To put it differently, HSP70 expression is connected to other homeostatically stressful situations (i.e., homeostasis-threatening situations), not only heat or proteostasis-hostile conditions.3, 10, 25, 43 It is worth noting that the perspective depicted in Figure 1 provides insight into just one facet of the HSR. This aspect pertains to situations characterized by predominantly proteotoxic stress, where HSF1 takes precedence over AMPK pathways. In contrast, AMPK pathways are favored in scenarios primarily marked by predominantly metabolic stress, particularly energy scarcity.

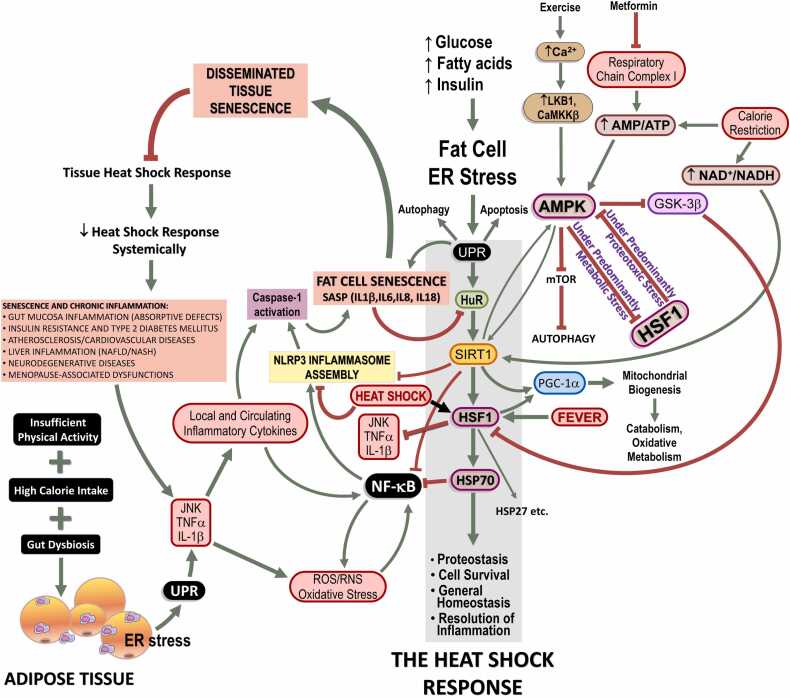

Fig. 1.

Heat shock response (HSR) failure in chronic inflammatory diseases: role of cellular senescence. Under normal nutrient supply (i.e., equivalent to energy expenditure, physical activity), glucose and fatty acids are utilized by adipose tissue upon physiological amounts of insulin. Any excess of demand is counteracted by enhanced HSR in order to supply the correct furnishing of chaperones thus avoiding misfolding or correcting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the resulting unfolded protein response (UPR). When circulating glucose and fatty acids (especially saturated) overcome energy expenditure and high amounts of surplus energetic metabolites should be stored in adipose tissue under a higher insulin command, ER stress develops. Should energy expenditure be still and chronically lower than energy intake, ER stress is followed by the UPR, a cellular strategy evolved in order to evaluate the capacity of the cell to arrange a physiological HSR (which conveys cells to protein/metabolite homeostasis). Of note, the illustration shows essentially one side of the HSR, that involving a predominantly proteotoxic stress in which HSF1 has prevalence over AMPK pathways, which is preferentially activated under predominantly metabolic stress conditions. In the case of irremediable HSR, cells may undergo apoptosis and irreversible cell death. On the other hand, if protein homeostasis (proteostasis) is not attained but cells still have conditions to avoid apoptosis, an alternative metabolic pathway may be taken in which cells do not dye but activate senescence, assuming a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). This is accomplished because adipocytes chronically challenged by excess fatty acids, cholesterol, high-fat diet, and hyperglycemia prepare an inflammatory response, which becomes chronic. Under the persistence of risk factors, cells develop an UPR that is diverted to the inflammatory branch since continuous inflammatory stimuli do not cease to activate NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to the activation of caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 determines, in adipocytes, a state of frank cellular senescence which culminates in SASP that can spread out to other tissues and cell types, including infiltrating macrophages of adipose tissue, skeletal muscle cells, pancreatic β cells, hepatocytes, vascular cells, and brain structures. In all these cell types, including adipocytes, SASP leads to cleavage of HuR, an mRNA-binding protein responsible for enhancing SIRT1 expression. As a consequence, HSF1 expression and transcribing activity becomes depressed, because SIRT1 enhances both. Therefore, HSR is hindered accordingly and a state of enhanced inflammation is noted because HSR is of crucial importance for the resolution of inflammation for many reasons, including, but not limited to, HSF1-dependent blockade of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and impairment of NF-κB activation. As a healthy HSR cannot resume, resolution of inflammation is more and more jeopardized thus impeding autophagy and an efficient resolution of UPR via HSR. Beside of this, senescent cells are resistant to undergo apoptosis, which should be an alternative to break this vicious cycle, so that chronically inflamed cells are likely to persist in tissues. Abbreviations used: AMP, adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, 5’-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; HSF1, heat shock transcription factor-1; HSP70, 70 kDa family of heat shock proteins; HuR, human antigen R; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; NF-κB, nuclear transcription factors of the kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (κB) family; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein-3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT1, NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase of class III family sirtuin-1; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α. Adapted and reused from: Ref. 9. Under an open access Creative Common CC BY license 4.0.

An intriguing facet to contemplate pertains to AMPK, the pivotal cellular energy sensor. In addition to its capacity to discern changes in AMP-to-ATP ratios, AMPK possesses a glycogen-binding domain within its β regulatory subunit.53 This unique feature endows it with the ability to function as a glycogen sensor. In addition, glucose can downregulate AMPK activity through protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) in various biological contexts, including rodent islets, β-cell strains,54 and yeast.55 The activation of PP2A by HSF1 results in the suppression of AMPK,56 subsequently promoting an increase in HSP70 expression.57 It is important to acknowledge, however, that, under specific circumstances, AMPK has the potential to inhibit HSF1, thereby promoting a pathway focused on safeguarding metabolic functions,58, 59 as proteostasis-saving functions depend on the energy of ATP to provide chaperone-assisted cytoprotection, a phenomenon known as caloristasis,13 as discussed in detail by Schroeder and colleagues.16

Exercise, as it can scarcely be otherwise, resembling a fight-or-flight stressor for the central nervous system (CNS), stands out as a potent inducer of the HSR and HSP70 expression across diverse tissues, rivaled only by heat. Notably, exercise prompts the release of eHSP70 into the bloodstream60, 61 and into the culture media of cells derived from exercised subjects.21, 26 This phenomenon is sophisticatedly linked to heightened immunosurveillance,62, 63 a process known to be orchestrated via α1-adrenergic signaling.23 Conversely, the consumption of glucose during exercise negates the expected surge in circulating eHSP70 levels.44 Notably, the expression of HSP70 and its release into the bloodstream are closely associated with indicators of cellular energy depletion. Accordingly, diminished glycogen levels are directly correlated with elevated expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels, of HSP72.64 Furthermore, this upregulation of HSP72 mRNA levels correlates with the onset of exhaustion, a stimulus integrated at the SNS level,65 while displaying an inverse relationship with lactate levels. Noteworthily, muscle temperature elevation primarily occurs at the outset of the exercise session.66

Following an acute bout of exercise, an increase in HSP70 and HSP90 levels is observed in plasma, mononuclear cells, and various organs and tissues, including muscle, liver, cardiac tissue, and brain. This specific response of HSP70 and HSP90 appears to be closely related to the exercise modality, with several dependent factors, such as exercise duration, intensity, type, the training status of the subjects, and environmental factors, such as temperature.67 Actually, as is the case of HSP70, HSP90 is also now considered a potential myokine (or exerkine68) and mediator of exercise-induced immune responses in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies.69 Interestingly, after repeated bouts of eccentric exercise, HSP70 and small HSPs accumulate in areas of myofibrillar disruption and sarcomeres, particularly in Z-disks.70

Still, regarding the connection between the HSR and the metabolic stress surveillance system, it is worth noting that, under predominantly proteotoxic stress conditions (Figure 1), AMPK plays a pivotal role in triggering the HSR by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), a protein that constitutively represses the activity of HSF1. GSK-3β serves as a negative regulator of glycogen synthase and is typically deactivated when the body is in an “energy plentiful” state, thereby liberating the conversion of glucose into glycogen. In contrast, AMPK serves as the primary “energy-sensing” kinase that responds to periods of “fuel scarcity” stress.3, 10, 71 It is also important to acknowledge that the impact of AMPK on the HSR is contingent on the prevailing caloristasis, meaning that during predominantly metabolic stress conditions, AMPK suppresses HSF1 activity, resulting in a dampened HSR. Conversely, under conditions characterized by predominantly proteotoxic stress, HSF1 can counteract the effects of AMPK, leading to a bona fide HSR.16

The AMPK-mediated alleviation of GSK-3β’s inhibitory influence on the HSR may occur through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), a nutrient-sensing pathway with extensive ties to energy metabolism and the HSR, beyond its role in glycogen synthesis.9, 72, 73 Glutamine, the primary amino acid released into the bloodstream by active skeletal muscle,9, 71, 74, 75 and a significant co-inducer of HSP70, enhances the HSR by increasing the HBP metabolic pathway which, in turn, leads to the inhibition of GSK-3β. Activated AMPK, in this situation, relieves the inhibition of HSF1, ultimately contributing to an anti-inflammatory HSR.9, 76 Notably, in the context of protein-aggregation disorders like Huntington’s disease, phosphorylation of Ser303 and Ser307 by GSK-3β results in the inactivation and degradation of HSF1.77

Turning our attention to the potential impact of exercise on homeostasis again, it becomes evident that exercise exerts a mechanical force, essentially a form of traction, on the skeletal structure. Given this, it was not unreasonable to anticipate that the physiological stress induced by exercise might extend to the bones. Intriguingly, this is rigorously the case. When bony vertebrates encounter immediate danger, stress signals in the basolateral amygdala of the brain trigger the release of glutamate by glutamatergic axons that contact osteoblasts in the bone. This triggers the secretion of osteocalcin, a bone-derived hormone (an osteokine78) that actively contributes to energy metabolism, reproductive processes, memory, and the capacity for exercise. These multifaceted functions are indispensable for thriving in unpredictable and hostile environments, such as the wilderness.79 Additionally and remarkably, osteocalcin plays a critical role in suppressing the tonus of the parasympathetic nervous system, which allows the stress response to occur because the sympathetic tone remains unopposed. As a result, osteocalcin is released from the osteoblasts as part of the acute stress response, which turns off the “rest-and-digest” arm of the autonomic nervous system and enables the acute stress response to proceed via the “fight-or-flight” sympathetic branch.79 Osteocalcin-mediated stress response results in a range of physiological manifestations, including increased body temperature and energy expenditure, elevated heart rate, and faster breathing.79 Bone-derived osteocalcin favors catecholamine synthesis in the brain, thus enhancing sympathetic tone which is the principal efference of the acute stress response80 and a major positive signal to trigger the HSR.

In concluding this discussion linking the stress responses among the SNS, metabolism, and exercise, it is crucial to highlight the pivotal role of the skeletal system as an endocrine organ in regulating glucose and energy metabolism. The interplay between bone and energy metabolism has long been a subject of interest, fueled by the observation of an inverse relationship between obesity and osteoporosis.81 Bone-derived osteocalcin stimulates insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and energy expenditure by upregulating the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), uncoupling protein-1, and mitochondrial biogenesis. Therefore, it is a typical homeostasis-protecting hormone. Also, its secretion and activity are modulated by various hormonal cues, including insulin, leptin, SNS activity, and glucocorticoids.82 Essentially, the effects of osteocalcin converge on the same metabolic pathways as those associated with the HSR. Furthermore, it is remarkable that serum osteocalcin levels are notably lower in obese children compared to their normal-weight counterparts, underscoring a negative correlation between osteocalcin levels and body fat mass.81

To summarize organismal HSR at this point, all known physiological responses to any kind of stress are definitely connected to the HSR. As inferred from the above findings, it is clear that the acute stress response of the skeleton involves metabolic signals similar to those managed in the HSR. Curiously, these pathways are also activated by osteocalcin under emotional stress (e.g., fear). They are the same metabolic routes activated under metabolic “fuel shortage” stress that triggers the expression and export of HSP70 to the extracellular milieu (eHSP70), as detailed above. Conversely, different HSPs influence the behavior of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes in the bone, thus participating in bone physiology. For example, although still a matter of debate, the chaperonin HSP60 (HSPD) stimulates osteoclast activity leading to bone resorption, as do HSP73 (HSPA8) and HSP90 (HSPCs).83 On the other hand, treatment of osteoblasts with HSR inducers, such as sodium arsenite or heat stress, led to the attenuation of osteocalcin synthesis induced by either bone morphogenetic protein-4 or the thyroid hormone T₃, along with an induction of HSP27 (HSPB1). Actually, current evidence strongly suggests that unphosphorylated HSPB1/HSP27 exerts an inhibitory effect on osteocalcin synthesis by a stimulatory effect on mineralization in osteoblasts.84 HSPB1/HSP27 is a molecular chaperone that operates independently of ATP and has been linked to tumorigenesis, metastasis, and protection against heat stress.85 Its function is influenced by its dynamic phosphorylation and heterogeneous oligomerization under varying conditions of stress. When unphosphorylated, HSP27 (HSPB1) can form large multimers of up to 800 kDa. However, phosphorylation triggers conformational changes resulting in significantly smaller oligomeric sizes, complex dissociation, and loss of chaperone activity. This indicates that HSP27 (HSPB1)’s reversible structural organization ultimately functions as a sensor that enables cells to adapt and overcome lethal conditions by interacting with appropriate protein partners.86 Therefore, it seems plausible that HSP27 (HSPB1) liberated by the skeletal muscle after exercise may be involved not only in tissue protein repair but also in disarming SNS after exercise. This signifies that evolution may have picked out this mechanism to say “danger has passed” and there is no longer a need to activate the fight-or-flight response.

In total, the HSR pertains to a general surveillance system that connects cellular proteostasis to physiological adjustments in blood pressure, cardiac output, temperature, glycogenolysis/glycogen synthesis (to correct glycemia), capacity to exercise (fight-or-flight), and affective (limbic) brain responses to already-experienced and unpredicted stresses, thereby anticipating such responses.

The HSR and the physiological resolution of inflammation

As stated in the Introduction section, there is a close association between intracellular quality control of proteins and inflammation. But what is the relation between protein aggregation and unresolved inflammation that permits the existence of chronic metabolic diseases of an inflammatory nature? The answer is that, because of many evolutionary reasons, activation of the HSR, does exert anti-inflammatory effects in animals, and, as we shall discuss here, HSR is progressively suppressed during the establishment of these chronic metabolic diseases, making inflammation perpetual.

Prior to acknowledging the significance of the HSR in the context of inflammation and exploring its role in the resolution of inflammation, it is essential to clarify a crucial point. When there is an excessive demand placed on ER functions, specifically concerning protein synthesis and proper folding, a cellular process known as the UPR is activated to prevent the accumulation of potentially cytotoxic misfolded protein aggregates. However, within the UPR framework, one of its branches, namely Inositol Requiring Enzyme-1 (IRE1)/c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 (JNK1) (discussed next), can physiologically incite an inflammatory response that depends on the nuclear transcription factors of the kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (κB) family (NF-κB) downstream pathways, ultimately triggering inflammation. Conversely, this same process also induces the expression of molecular chaperones. Consequently, the HSR emerges as a vital mechanism to counteract any excessive inflammatory response triggered by a potent UPR. This elucidates a significant aspect of the HSR in resolving inflammation. In essence, the HSR evolved as a potent anti-inflammatory tool, strategically harnessed to combat various forms of inflammation.

The HSR exerts cogent anti-inflammatory effects, primarily because HSP70s (HSPAs) act as natural inhibitors of NF-κB subsequent signaling cascades. NF-κB activation is sufficient and sine qua non to trigger inflammation since all known inflammatory cytokines and mechanisms involved in inflammation are NF-κB-dependent. HSP70s stabilize the inhibitors of κB (IκB) complexes with NF-κB, thus preventing the translocation of the active dimers (e.g., p50/p65) into the nucleus and the consequent transcribing activity.87, 88 Many other forms of HSP70-dependent anti-inflammatory activities have also been reported.89 They include induction of HSP70-dependent anti-inflammatory cytokines, modulation of dendritic cell phenotype favoring Th2-over-Th1 lymphocyte differentiation, and preferential activation of Treg cells.89

Inflammation is a well-preserved response intended to eliminate microorganisms or prepare tissue recovery during an aseptic injury. In a nutshell, inflammation evolved as an adaptive response for restoring homeostasis.90 Importantly, immune responses related to inflammation can be appreciated in all metazoans.91 These responses are usually acute, in that cells of the innate immune system are recruited to the site of sterile injury or to defeat microorganism invasions. Having achieved this objective, inflammation is rapidly dismantled. A successful acute inflammatory response culminates in the eradication of infectious agents (or the start of tissue remodeling), followed by a phase of resolution and tissue repair.90 That is to say, chronic inflammation was not part of the original evolutionary blueprint; much less chronic inflammatory diseases.

When an acute inflammatory response is activated in the body, a significant production of pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid-derived prostaglandins (PGs) occurs, along with other lipid mediators and vasoactive compounds.10 These signaling molecules play a decisive role in alerting immune cells and sensory pathways to the presence of an invader or tissue injury. They also increase vascular permeability, which allows more inflammatory cells to arrive and activate, leading to tissue repair.90 This process is initiated by a finely orchestrated expression of inducible proteins centered around NF-κB transcription factors, which drive inflammation during the initial phase.92 However, these same molecules also contribute to the resolution of inflammation.3, 10, 93, 94, 95 Additional polyunsaturated fatty acid-derived mediators, such as lipoxins and dietary ω3-fatty-acid-derived resolvins and protectins, further facilitate the resolution of inflammation and tissue repair.90

Within 2 h of the start of an inflammatory response, a powerful wave of NF-κB-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2, formally known as PGs endoperoxide H synthase) surges through the body tissues, synthesizing copious amounts of PGE2 from arachidonic acid. This early phase can be inhibited by both selective COX2 inhibitors (COXIBs) and traditional dual COX1/COX2 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, there is an unpredicted and serious risk here: using such inhibitors to alleviate fever, headache, or body pain, at any time during an inflammatory response, strongly exacerbates inflammation at later stages (after 48 h from the beginning), impeding its resolution phase and prolonging or perpetuating the inflammatory state.94 This occurs due to various causes. Firstly, PGE2 is a potent inducer of fever, by impeding the processing of thermosensory information at the preoptic area of the hypothalamus.32, 96, 97 This PGE2 signal then triggers autonomic heat-sparing mechanisms located at the rostral medullary raphe pallidus premotor nuclei, setting off a cascade of bodily responses, including cutaneous vasoconstriction, the feeling of cold and, prominently, elevation of core temperature (fever). Therefore, the initial phase of inflammation (PGE2-driven) tends to induce fever (the most potent physiological HSR inducer) precisely to prepare the termination phase (resolution) so that COXIBs or conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs gravely jeopardize the physiological resolution of inflammation. Strikingly, fever effectively orchestrates antimicrobial defenses and aids in controlling inflammation and tissue repair, even in cold-blooded vertebrates (!), where there is selectivity in the immune mechanisms activated by fever. In summary, fever inhibits inflammation and significantly enhances wound repair98 throughout the metazoan kingdom. Because the HSR is a multifaceted anti-inflammatory and antiviral mechanism that naturally resolves inflammation, selective manipulation of this pathway has the potential to control and prevent multifactorial diseases.99 Quite the contrary, however, long-term use of COXIBs obviates the physiological triggering of the HSR and, as a result, has been shown to be harmful to human health.100, 101 This harm has led to the withdrawal of rofecoxib and valdecoxib from the market due to their association with cardiovascular complications.101 Let us not forget: the HSR is also anti-inflammatory in the cardiovascular system. The second point regarding the negative impact of blocking COX activity is that PGE2 induces fever in the first step but, shortly after, it undergoes dehydration in the plasma into the highly electrophilic cyclopentenone PG (cyPG) PGA2,102 which is a powerful antiproliferative eicosanoid that can shut off NF-κB directly and also via HSF1 activation.103, 104, 105 In addition, heat induces HSF1-dependent COX2 expression, leading to explosive PG production and HSP70 synthesis, which inhibits NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory cascades.106 Please, see Figure 2 for the detailed involvement of COX-2 in the HSR.

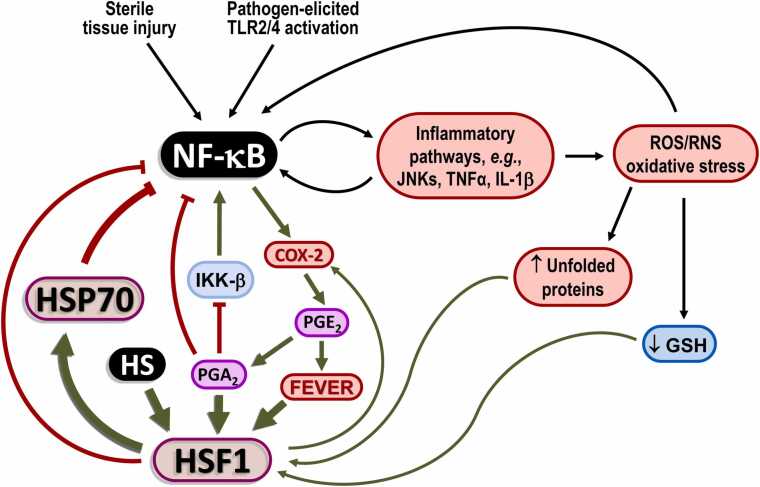

Fig. 2.

Heat shock response (HSR) dynamics in inflammatory responses. Highlighted is the dual function of NF-κB in promoting pro-inflammatory cytokine production and priming the resolution phase via COX-2 activation. Abbreviations used: COX2, cyclooxygenase-2; HSF1, heat shock transcription factor-1; HSP70, 70 kDa family of heat shock proteins; IKK-β, IκB kinase-β JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; NF-κB, nuclear transcription factors of the kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (κB) family; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α

Anti-inflammatory A-type PGs may also exert an antiproliferative effect by operating akin to statins, as they bind directly and covalently to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase.107 This enzyme serves as the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis. However, the inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase not only prevents the formation of cholesterol, the final product of this pathway but also hinders cell proliferation. This is because various isoprenoid intermediates, essential for cell proliferation, are synthesized between HMG-CoA and cholesterol. In essence, disrupting cholesterogenesis leads to the inhibition of cell proliferation.108, 109 Strikingly, inducers of the HSR, particularly anti-inflammatory cyPGs, at the same time, potently inhibit viral replication in various DNA and RNA viruses, including HIV-1, via HSF1-dependent inhibition of NF-κB activation and HSR activation.103, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117 Blocking virus replication by cyPGs depends on HSP70 synthesis, which explains why hyperthermic treatment is antiviral, including in the fever-like range.118 Beyond the intracellular effects against inflammatory pathways already discussed, the HSP70 family of chaperones is also involved in the response to viral infections. HSP70 plays an important role during virus internalization, replication, and gene expression.119

During the most important virus-elicited pandemic of this century, many research groups suggested a possible link between the major susceptibility to infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, in patients with metabolic diseases presenting chronic failure to trigger a robust HSR.120, 121, 122, 123 Administration of recombinant HSP70 in vitro and in vivo has been found to decrease inflammation and respiratory distress syndrome in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection.124 At the moment, only one study by our own team has assessed the HSR in COVID-19 patients. However, we did not find a difference in the HSR between critical COVID-19 patients with and without T2DM, because of a worsening of HSR in both groups, when these patients’ results were compared with normal never-infected individuals.125 HSR impairment in severe COVID-19 patients appears to be independent of previous metabolic status. However, we assessed only severe COVID-19 patients. Hence, further research is required to discern whether the severity of COVID-19 itself dampens the HSR and/or whether individuals with a robust HSR prior to infection are less likely to experience worsening outcomes.

One of the evolutionarily oldest mechanisms involved in the termination of inflammation is certainly the HSR. This is not a mere coincidence. During an inflammatory response, ER is highly demanded to give rise to and prepare immunoglobulins and pro-inflammatory cytokines in immune cells. This must be closely supervised by HSP chaperones. If a minimal imbalance between protein synthesis and chaperoning activity is perceived by ER molecular sensors, it is imperative for the cell to halt protein synthesis and increase its chaperoning capacity immediately to avoid the accumulation of potentially toxic protein aggregates. If this occurs, aggregates of unfolded proteins are conveyed to HSP70/HSPA1s (or HSP90/HSPCs) to be refolded or conduced to proteasome-dependent degradation in the case of irrecoverable misfolding. On the other hand, if ER is overburdened with excess unfolded proteins, UPR takes place in order to suspend protein synthesis and enhance the production of HSP70s (and other chaperones). Notwithstanding, UPR has an inflammatory branch that can be counteracted by the concomitant production of the anti-inflammatory HSP70 under physiological conditions. This closes the feedback loop between inflammation and the physiological resolution of inflammation through the control of proteostasis while opening a window to the understanding of the suppression of the HSR in chronic inflammatory diseases.

Impaired resolution of inflammation due to progressive suppression of HSR in chronic-degenerative inflammatory diseases

The connection between chronic inflammation and the HSR involves a very complex network that operates at the gene regulatory level. The tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) gene promoter, for example, contains an HSF1 binding site that represses TNFα transcription.126 Consequently, knockout of HSF1 gene is associated with a chronic augmentation of TNFα levels, increased susceptibility to endotoxin challenge,127, 128 and NF-κB/AP-1-mediated exacerbation of angiotensin-II-induced inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells.129 On the flip side, TNFα can temporarily inhibit HSF1 activation.130 Additionally, the pro-inflammatory kinase, JNK1, phosphorylates HSF1 in its regulatory domain, leading to the suppression of HSF1 transcriptional activity. On the other hand, HSP70 may inhibit the JNK pathway to prevent apoptosis.128, 131 Exposure of cells to heat shock and other protein-damaging conditions, including ethanol, arsenite, and oxidative stress, strongly decreases the rate of JNK dephosphorylation,132, 133 thus inhibiting JNK activity.

HSF1 suppresses IL-1β gene transcription by forming a complex with the nuclear transcription factor of interleukin-6 (NF-IL6), which directly inhibits IL-1β gene promoter activity.134 However, NF-IL6 can prevent HSF1 activation by blocking its transcriptional activity and displacing HSF1 from the heat shock elements in the promoters of heat shock genes.135 Additionally, IL-6 can depress HSF1 transcribing activity via GSK-3β activity.136 HSF1 and NF-IL6 have mutually antagonistic effects,137 and the preponderant effect depends on the most prevalent stimulus, as observed for several other pro-inflammatory genes.138 These interactions depend also on the degree of predominance of metabolic or proteotoxic stress (caloristasis), as approached in the previous sections. Therefore, a delicate balance is required to equilibrate pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses depending on the overall signals that converge to HSF1 and its regulators. In T2DM, the disruption of insulin signaling leads to HSF1 deactivation, as GSK-3β constitutively inhibits HSF1 through direct phosphorylation. This reduces HSR activity and subsequently fosters heightened activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, JNK, and IκB kinase (IKK)-β. These signals, in turn, lead to the phosphorylation of Ser307 of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), further impeding insulin signaling.139

Since T2DM and its complications have oxidative stress as an underlying mechanism, and considering that HSPs are major protective molecules against oxidative stress, Kurucz and colleagues tested and demonstrated, for the first time, the hypothesis that HSP72 (HSPA1s) mRNA contents should be undermined in the skeletal muscle of T2DM patients. In fact, they observed that decreased levels of HSP72 mRNA in the skeletal muscle of T2DM patients were correlated with a decreased rate of glucose uptake by cells and insulin resistance.140 In T2DM and obesity, decreased expression of both HSP70 and HSF1 is a common feature detected in adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, and vascular beds of patients.30, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149 Depressed HSR is also evident in menopause-related metabolic dysfunctions10, 150 and in tissues of obese151 and older adults,152, 153, 154 including those presenting neurodegenerative diseases.9, 155 Impaired HSR has also been reported in rodent models of obesity, insulin resistance, and CVD.153, 156, 157, 158 Of note, pharmacological159 as well as non-pharmacological interventions156, 160 intended to activate HSF1 have been evaluated to block or reverse such unhealthy conditions via enhancing HSR successfully. Additionally, protein aggregation-related neurodegenerative diseases are also directly linked to a deficiency in the expression and function of HSF1, particularly to its degradation and loss of DNA binding activity.77 HSP70s, on the other hand, provide protection against an array of brain disorders, including trauma and stroke,161, 162 not necessarily linked to protein aggregation directly.

As we discussed in the previous sections, ER stress can be resolved in various ways, such as increasing the capacity of protein chaperoning and decreasing protein synthesis. When the demand for ER functions exceeds its ability to cope with protein synthesis without accumulating misfolded proteins, the ER proteostasis surveillance system, under ER stress, triggers the UPR (to avoid undesirable tautology, please refer to the excellent review by Hetz et al.163). UPR, in turn, has two major biochemical pathways to resolve ER stress, the adaptive and the proapoptotic routes. The first was evolutionarily selected to protect cells from proteotoxic oxidative stress while increasing protein chaperoning and refolding. The second is activated when the capacity of UPR to sustain proteostasis is exceeded and cells enter apoptotic programs. Within the adaptive UPR, there are three known main routes responsible for the re-establishment of proteostasis without the need for condemnation of cells to die by apoptosis: the Protein kinase-like ER Kinase (PERK)-dependent pathway, the Activating Transcription Factor 6 (ATF6)-dependent pathway, and the IRE1α also known as ER-to-Nucleus Signaling-1)-dependent pathway. PERK route is in charge of translation attenuation to reduce protein folding load, selective translation, autophagy, and antioxidant responses. The ATF6 pathway regulates the transcription of genes that encode ER chaperones, enzymes that facilitate ER protein translocation, folding, maturation, and secretion, as well as proteins involved in the degradation (ER-associated protein degradation) of misfolded proteins. ATF6 functions transit between ER and Golgi apparatus. Finally, IRE1α-dependent pathways regulate protein loading in the ER, metabolic adaptation, autophagy, ER-associated protein degradation, and NF-κB-dependent inflammatory signals via the NLRP3 inflammasome. Furthermore, IRE1α can associate with adapter proteins to engage in crosstalk with other stress response pathways such as macroautophagy and the MAPK pathways.163

Hence, evolution selected a protein-folding correction system to resolve UPR with a momentary inflammatory profile, at the same time the HSR works as a sentinel to supervise both protein chaperoning activity and NF-κB-dependent signals to avoid unwanted inflammation from being triggered during UPR. For these reasons, when examining the low-grade inflammatory background that accompanies all chronic degenerative diseases of an inflammatory nature,3, 159, 164 the question arises: why does the HSR fail to eliminate UPR-elicited inflammatory signals caused by excessive ER stress? Why does the HSR not function to promote the physiological resolution of inflammation in these cases? The answer to these questions lies in the fact that metabolic stresses resulting from energy imbalance (surplus) and insufficient physical activity continually require providence from the ER. This leads to the sustained maintenance of ER stress and exacerbated UPR. Additionally, both the adaptive and proapoptotic UPR pathways ultimately have inflammatory branches that rely on the activation of NLR-family inflammasomes (including NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP6, and NLRC4), which promote the conversion of procaspase-1 to cysteine-aspartate protease-1 (caspase-1) (formerly known as interleukin-1 converting enzyme).

Inflammasomes are evolutionarily marvelous complexes of molecular platforms that sense and respond to danger signals. These large multimeric complexes are responsible for promoting the activation of caspase-1, a crucial enzyme involved in immune and inflammatory responses. In addition to activating caspase-1, inflammasomes also play a key role in cleaving inactive pro-interleukins and other target proteins, ultimately leading to the production of their active forms. Although all NLR-type inflammasomes can activate caspase-1, the NLRP3 inflammasome has been studied the most extensively.165, 166 Importantly, NLRP3 inflammasomes have proven to be involved in the noxious effects of permanent ER stress, as we shall discuss next.

Under chronic ER stress, PERK-elF2α-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-JNK pathways are activated from the lumen of ER to prepare the UPR or initiate apoptosis in mammalian cells.167 In particular, IRE1, which is a serine/threonine-protein kinase/endoribonuclease, connects ER stress to NF-κB-dependent inflammatory signals. Accordingly, in response to ER stress, maximum activation of NF-κB requires the presence of the IKK to address the IκB to proteasome degradation. However, unlike canonical activation of NF-κB, the activity of IKK does not increase during ER stress. Instead, the extent of NF-κB activation depends on the level of basal IKK activity, which is crucial for determining the response. In this way, IRE1, a critical initiator of the UPR, contributes to maintaining the basal activity of IKK through its kinase activity but not its RNAse activity.168 As a consequence of the above ER mechanisms, if the flow through the UPR overcomes the cellular ability to repair proteins, the inflammatory branch of the UPR overwhelms its anti-inflammatory capacity (via HSP70s) and a huge burst of NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokines begins. This is exactly what happens in adipose tissue when energy intake surpasses energy expenditure, as stated in the Introduction section. And more: an endless ER stress accompanied by strong UPR may occur in adipose tissue even without any apparent obesity. In other words, overburdened UPR and low-grade inflammation may ensue in apparently lean individuals, as is the case of lean T2DM patients.169 Indeed, the major point here is the “metabolic stress” to the adipose tissue (i.e., adipocytes and their satellite cells, such as macrophages), not overweight or obesity itself. Unfortunately, however, chronic degenerative diseases of an inflammatory nature are all associated with progressive UPR-dependent suppression of the HSR.

When ER stress in adipose tissue remains constantly utilizing the pro-inflammatory pathways of the UPR, the permanent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is inevitable. However, in this situation, various pro-inflammatory cytokines are activated (after cleavage of their respective pro-cytokines by caspase-1). This results in the incessant production of caspase-1, which in turn allows for the activation of large quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines.170, 171 These cytokines affect adipose tissue but are also released by it into its surroundings.3 Consequently, “aberrant” activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is implicated in various inflammatory disorders, such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and atherosclerosis that occur far from adipose tissue.3, 165, 172, 173, 174 The persistent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome has another facet: the establishment of a pattern of pro-inflammatory cytokine production known as the SASP, which was mentioned in the Introduction section. As shown in Figure 1, fat cell senescence and the associated SASP may be an alternative mechanism emanating from the UPR that cells employ to avoid apoptotic death when autophagy is not working and the anti-inflammatory HSR fails to operate.3 In fact, a senescent-like state can emerge in the fat cells of obese individuals (even young obese subjects), as an adaptation to the overutilization of such cells, which resembles cellular aging.175 Additionally, high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity can lead to vascular senescence through long-term activation of Akt1 and mTOR.176 As proliferative senescence serves as an alternative to apoptosis, it would represent an interesting evolutionary solution that could preserve dysfunctional cells, although at the expense of the organism. Teleologically, this may seem counterintuitive as it undermines the overall health of the organism. On the other hand, it appears clear that evolution did not anticipate the extent to which humans would challenge the biochemistry originally “designed” for the intermediary metabolism of an animal consuming a Paleolithic diet (consisting of lean meat, fruits, vegetables, and nuts, but not grains, dairy, or legumes) and engaging in hunter-gatherer levels of physical activity.3

Cellular senescence, or proliferative senescence, is a part of the cellular stress response. Senescent cells are identified by a combination of features and molecular markers, including essentially permanent growth arrest. However, no single characteristic is exclusive to the senescent state and not all senescent cells display all known markers. Therefore, senescent cells are typically identified by a conjunct of characteristics,177 which will not be approached here.

Now, we present evidence revealing how the HSR is profoundly obstructed by cellular senescence in response to the abundant activation of UPR. Human fibroblasts from adult segmental progeroid Werner syndrome undergo premature senescence that is associated with a strong positive feedback system in which overactivation of the p38-NF-κB pathway in these cells leads to SASP, which then attenuates the expression of the mRNA-binding protein human antigen R (HuR; also known as embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila, homolog-like protein-1). HuR is a critical factor for the activity of the NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase of class III family sirtuin-1 (SIRT1).178, 179 Indeed, the copious amount of NLRP3 inflammasome-originated caspase-1 progressively destroys the available quantities of HuR because caspase degrades HuR.180 Caspases can also mediate the cleavage of HuR under different situations.181 Of note, HuR enhances the stability of various target mRNAs, such as the one encoding SIRT1. This occurs through the association of HuR with the 3′-untranslated region of SIRT1 mRNA, leading to an increase in SIRT1 protein expression levels.178 However, oxidative stress, which is a potent activator of NLRP3,170 disrupts the interaction between HuR and SIRT1 mRNA. This leads to a decrease in cell survival through a cycle checkpoint kinase-2-dependent mechanism.178 SIRT1, on the other hand, enhances the expression of HSF1179 and, when activated, SIRT1 prolongs HSF1 binding to the promoters of heat shock genes by maintaining HSF1 in a deacetylated, DNA-binding competent state.126, 182 Furthermore, heat shock itself increases the cellular NAD+/NADH ratio and enhances the recruitment of SIRT1 to the HSP70 promoters.183 Conversely, SIRT1 knockdown attenuates the HSR,184 while SIRT1 modulators were found to also modulate HSF1 activity and the HSR in human cells.183

During caspase-mediated apoptosis, HuR undergoes a functional switch from pro-survival to pro-apoptotic.185 Interestingly, attenuation of HuR sensitizes adenocarcinoma cells to apoptosis.186 However, in the context of continuous NLRP3 inflammasome activation, the ability of HuR to induce apoptosis187 is inhibited. This is due to the caspase-dependent degradation of HuR, which triggers a process of senescence-associated SASP, ultimately preventing the cells from undergoing apoptosis. This is a regrettable circumstance since apoptosis of cells relaying inflammatory signals would have the potential to relieve the organism of the SASP that induces inflammation everywhere.

After a cellular insult, such as genotoxic stress, HuR binds to SIRT1 mRNA, triggering an anti-apoptotic and pro-survival gene expression program.188 However, the involvement of HuR in cellular homeostasis extends beyond this function. It plays a role in the differentiation of pre-adipocytes by regulating the translation and stability of GLUT1 mRNA, indicating its importance in muscle and adipose tissue differentiation processes.189 Reduced HuR levels are associated with increased cellular senescence. This is why HuR is considered the patron of the “young cell” phenotype.190 In addition, HuR works in synergy with heat shock and calorie restriction, which enhance SIRT1 deacetylase activity, to respond to heat shock.183

The tangled interplay between HuR-dependent HSR and the metabolic state of cells extends further. On the one hand, HuR regulates SIRT1 mRNA expression and stability, consequently influencing HSF1 expression and activity. On the other hand, HSF1 may fine-tune the transcription of HuR in a complex interplay involving AMPK, HuR, and SIRT1.59 Despite HuR may autoregulate its own expression through alternative polyadenylation site usage,191 HSF1 exerts tight control over HuR transcription.59, 192, 193, 194, 195 For HuR to operate adequately as an mRNA-binding protein, it has to be exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nevertheless, in predominantly metabolic stress conditions, AMPK robustly inhibits the translocation of HuR to the cytosol.196, 197 Therefore, in these cases, increased AMPK activity directly contributed to the implementation of the senescent phenotype, as opposed to that observed when HuR is free to operate onto target mRNAs in the cytosol. As a consequence, AMPK activation can cause premature fibroblast senescence through mechanisms involving reduced HuR function.190 During a predominantly proteotoxic stress (e.g., heat), however, inhibition of AMPK is beneficial to cell survival57 in part because HuR is freed to stabilize SIRT1 thereby increasing HSF1 activity and the HSR. In fact, during a bona fide HSR, PP2A-mediated AMPK inhibition upregulates HSP70 expression at least partially through stabilizing its mRNA.57

The tumor suppressor kinase LKB1, which typically activates AMPK, may suppress HSF1 activity through Ser121 phosphorylation, preventing its nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and transcriptional activity.198 To the contrary, HSF1 may reciprocally suppress AMPK by directly enforcing an inactive conformation. By physically evoking conformational switching of AMPK, HSF1 impairs AMP binding to the γ-subunits, enhances the PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation, and impedes the LKB1-mediated phosphorylation of Thr172, as well as retards ATP binding to the catalytic α-subunits.56 Curiously, activation of PP2A in the brains of zebrafish and mice does reverse age-related behavioral changes in senescent neurons.199 This is why, when there is predominantly proteotoxic stress (which releases HSF1 from chaperones), there is also a concomitant blockade of AMPK. In toto, the final destination and metabolic direction of the HuR-SIRT1 duet depends ultimately on the predominance of either proteotoxic or metabolic stress conditions, that is, caloristasis.13

Apart from the above findings, SIRT1 has also been shown to mitigate ER stress and insulin resistance triggered by saturated fatty acids in hepatocyte-like cells.200 Additionally, alongside SIRT1, histone deacetylase 6 can detect protein aggregation and, through its ubiquitin-binding domain, relieve HSF1 from repression, resulting in the disassembly of inhibitory HSP90–HSF1 complexes, thereby enabling HSF1 activation in the presence of protein aggregation.59 Resveratrol, a known inducer of SIRT1 metabolic action that obstructs NLRP3 inflammasome,201 can shift the metabolism of mammals from a high-calorie diet to that of animals maintained on a standard diet. This is achieved by increasing insulin sensitivity, AMPK activity, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), which in turn increases the mitochondrial number and oxidative metabolism.202, 203 Moreover, SIRT1 activates PGC-1α through deacetylation, which stimulates the production and secretion of the myokine Irisin. This myokine acts in white adipose cells, both in vitro and in vivo, promoting a brown-fat-like phenotype through the stimulation of uncoupling protein-1 expression.204 This link between calorie restriction, physical exercise, and protective energy-consuming oxidative metabolism is crucial for preventing metabolic syndrome and age-related diseases. Additionally, there is significant evidence highlighting the tight link between calorie restriction and exercise-induced HSR with metabolic stress, which is protective of metabolism. This is achieved by inducing chaperones during a healthy HSR, through the participation of anti-senescence SIRT1 pathways.205 Therefore, the interaction between HuR and SIRT1 is of critical importance for the beneficial effects of the anti-inflammatory and anti-senescence HSR.

As a whole, these findings indicate that the HSR is progressively suppressed under conditions that surpass the capacity of the UPR to operate in favor of proteostasis. Subsequently, this sets in motion a continuous activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which, in a cascading effect, culminates in caspase-1-induced degradation of HuR. This degradation, in turn, results in a reduction in HSF1 expression and DNA-binding activity, ultimately leading to the dismantling of the HSR in such scenarios. Therefore, the Western lifestyle that constantly drives ER stress in adipose tissue culminates in UPR-elicited SASP via continuous activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which triggers a limitless suppression of the HuR–SIRT1–HSF1 axis and the consequent abolishment of the HSR. By downregulating HSF1 expression (and its DNA-binding activity) and the consequent anti-inflammatory HSR, SASP contributes to its own initiation and perpetuation.179 Worse still, adipose tissue-emanated pro-inflammatory cytokines spread out through the organism, triggering SASP and suppression of the HSR in other tissues, as approached next.

SASP-mediated inflammatory response in non-adipose tissues: Evidence of systemic spread

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in adipocytes plays a deciding role in the onset of various metabolic diseases, such as atherosclerosis and insulin resistance.172 Interestingly, the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome seems to act as a “danger sensor” in response to injurious stimuli that induce senescence, such as UVB irradiation or metabolic stress from high extracellular glucose.206 In mononuclear cells of the immune system, including macrophages, NLRP3 inflammasome activation can be triggered by several signals, including glucose, palmitate, uric acid, ceramide, reactive oxygen species, and pancreatic islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP).207 In the context of Western HFD, the cleavage of SIRT1 induced by inflammation in adipose tissue is NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent.208 Additionally, genetic ablation of NLRP3-comprising its components or caspase-1 leads to improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in HFD animals.173, 209 Curiously, metformin, a known inducer of AMPK activity, reduces NLRP3 protein expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammatory macrophages,210 thus operating as a proteostasis-saving kinase facilitating HSF1 activity and the HSR.

Obesity triggers the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in response to modified low-density lipoprotein particles, free fatty acids (particularly saturated), and intracellular cholesterol crystals, thereby modulating adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity.173, 211 Actually, high cholesterol levels explain inflammation in the cardiovascular system due to NLRP3 inflammasome activation as well.212 Notably, glucose directly stimulates caspase-1 activity,207 adding yet another harmful consequence of hyperglycemia observed in diabetes mellitus of any type. NLRP3 inflammasome senses obesity-associated danger signals and contributes to obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance.213 Hyperglycemia, palmitate, uric acid, LPS, and IAPP all prime the activation of inflammasomes in target cells, such as adipocytes, macrophages, hepatocytes, and the islet of Langerhans cells, promoting the start of caspase-1 mRNA expression. Moreover, the aggregates of IAPP are toxic to pancreatic β-cells and associated with the pathogenesis of T2DM. IAPP is also able to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.214 One concerning aspect of this narrative is the extended and copious activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the resulting dissemination of SASP, which eventually leads to cellular senescence instead of apoptosis in target cells. Senescent cells resist apoptosis, perpetuating chronic inflammation in tissues and sustaining chronic inflammatory diseases throughout the body.172, 206, 215

In the context of feminine endocrinology, estrogen is a potent inducer of the HSR.10 Accordingly, estrogen depletion is linked to various inflammatory events in the CNS that are associated with NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, in menopause, estrogen replacement can potentially alleviate this scenario by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation through the type β estrogen receptor pathway.216 This has also been observed in reproductively senescent female rats.217 Similarly, after global cerebral ischemia, a condition that causes significant oxidative stress and inflammation, local estrogen administration has been found to completely inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its associated inflammatory pattern.218 Both estrogen and progesterone are known to modulate inflammasome activation and mediate anti-inflammation in the CNS.219 These findings align with estrogen’s anti-inflammatory effects, which mirror its anti-senescence actions. This lends support to the notion that some of estrogen’s protective effects stem from its ability to maintain a robust HSR by disrupting the destructive cycle that diminishes HSF1 availability due to SASP and cellular senescence. Notably, heat shock treatment impedes the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome,220 thereby overcoming the destruction of HuR and tissue senescence associated with depressed HSF1 expression and low HSR. Hence, paradoxically, heat shock alone can re-establish the HSR. These observations, alongside the findings described in Schroeder et al.,221 suggest that heat treatment should be evaluated in menopausal women.

The association between metabolic stress-induced ER stress in adipose tissue and unresolved inflammation centered on the continuous activation of NF-κB members is a causal factor for the progression of metabolic diseases and has, in essence, the overwhelmed UPR being ultimately responsible for the continuous secretory profile of cytokines.222, 223 This “seeding” of inflammation takes place initially in the adipose tissue and then spreads throughout all body tissues that work as SASP-relaying points.3 SASP-associated production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18, has been linked to a persistent DNA damage response224 and, consequently, to an antiapoptotic senescence state. This perpetuates SASP-induced inflammation in all body tissues. There is an interaction between genes that regulate intermediate metabolism and those of the immune system, such as TNFα, leptin, adiponectin, resistin, interleukins IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and C-reactive protein, just to cite a few examples, and all of them tend to impose a SASP and apoptosis-resistant senescence. In this regard, TNFα is known to activate signal transduction cascades, including some pathways strictly involved in inhibiting insulin action, such as the activation of JNKs. These kinases are particularly critical to insulin signaling in adipose tissue and striated muscle because they phosphorylate insulin receptors and other coupling proteins in serine residues, blocking the normal post-receptor insulin signals.225 Activation of Toll-like receptor 4 in the intestine, due to nutritional and energy imbalances, leads to a change in the microbiota (gut dysbiosis) that also results in insulin resistance.147, 226 TNFα is strongly expressed in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of obese individuals and, when administered in the circulation, induces insulin resistance.227 Conversely, inhibition of the action of this cytokine in a model of obesity in rats leads to an increase of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipose tissue.228 TNFα reduces insulin signaling by inducing phosphorylation of IRS-1 in Ser307 in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver, while in the liver, this cytokine acts dependently on JNKs.229, 230 Furthermore, in a remarkable evolutionary innovation, a distinct negative feedback mechanism was introduced into insulin signaling to disrupt excessive downstream signal transduction via insulin receptors. This involves the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent activation of the very JNKs, which disrupts insulin signals.231 TNFα also imposes a similar inhibition over IRS-1 in muscle and fat tissues from obese rats.230 Consequently, excessive insulin concentrations undeniably result in insulin resistance (i.e., insulin-dependent insulin resistance) and the generation of inflammatory signals in target tissues.

Since continuous activation of NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent and NF-κB-dependent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines become perpetual, pro-inflammatory kinases, such as JNKs, are rendered vigorously active inhibiting insulin signaling,225 which could be avoided by the direct binding of HSP70 to them.232 Studies from this laboratory with individuals undergoing bariatric surgery also show that the inflammatory process that begins in the adipose tissue spreads out to the liver, leading to a reduction in the expression of HSF1 and HSP70 with a significant increase in the expression of JNKs both in the liver and adipose tissue.144

As approached in the previous sections, GSK-3β, a serine/threonine protein kinase responsible for phosphorylating specific target serine and threonine amino acid residues, physiologically and constitutively inactivates HSF1 under normal cellular conditions.233 Conversely, GSK-3β inactivation is contingent upon the PI3K pathway, effectively making it dependent on the insulin signaling pathway.95 This elucidates why, during the development of insulin resistance, the mechanism for GSK-3β inactivation via AMPK and SIRT1 fails, resulting in the continuous suppression of HSF1 activity.234 The reduced activity of the HSR pathway is directly linked to insulin resistance and the worsening of type 2 diabetes.127, 151 Therefore, it is crucial to monitor the temporal progression of chronic inflammatory diseases with regard to impaired HSR.221

Since both HuR and SIRT1 are recognized as anti-senescent and anti-inflammatory proteins,10 senolytic therapies have been developed and are now in clinical trials. These therapies employ drugs (known as senolytics) that preferentially target senescent cells and selectively eliminate them by inducing apoptosis.235, 236 The aim is to stop the noxious ER-stress-SASP-inflammation vicious cycle and restore the physiological resolution of inflammation via HSR. Senescent cells can be dysfunctional, decreasing the survival rate even in young animals, whereas senolytics can enhance the lifespan of older ones.237 In fact, combinations of FDA-approved senolytic drugs, such as quercetin and azithromycin, have been proposed for treating COVID-19 patients,238 particularly those with chronic metabolic diseases of an inflammatory nature, which pose a significant threat to these patients.120

Although having underlying mechanisms not completely understood, aging may also be associated with deficient HSR. Aging is a complex process modulated by different molecular and cellular events, such as genome instability, epigenetic and transcriptional changes, molecular damage, cell death, proliferative senescence, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction.9 Particularly, protein quality control (i.e., chaperone systems) tends to be negatively affected by aging, thus leading to cellular senescence in metabolic tissues and, as a consequence, to the increased dissemination of inflammation throughout the body. Of particular note is the age-dependent increase in inhibitory signals directed to HSPs, as well as hyperacetylation that is associated with a significant reduction in the activity of HSF1 in binding to DNA.239 Hence, cellular senescence is a common link in the chain of chronic degenerative diseases, including during aging, because, as stated here, SASP-producing cells are extremely resistant to apoptosis and allow for a state of low-grade chronic inflammation all the way through the organism.3, 9

A substantial body of research has explored the link between activating the HSR and extending longevity. In the nematode C. elegans, the post-reproductive stage is marked by a sudden decline in protein quality control.9, 240 Consequently, the capacity to respond effectively to heat stress becomes a crucial characteristic of longer-lived animals. In C. elegans, overexpression of the HSF1 orthologue, hsf1, in all tissues enhances resilience to stress and retards aging. Overexpression of hsf1 in the CNS, on the other hand, is sufficient to enhance both protection against acute thermal stress and longevity,241 possibly because this maneuver triggers cell-nonautonomous regulation of proteostasis through TCS.34 Interestingly, a cold-sensitive strain of Hydra oligactis shifts from asexual budding to sexual reproduction when exposed to temperature stress (from 18 to 10 °C). This involves an upregulation not only of gametogenesis-related genes, but also of those related to cellular senescence, apoptosis, and DNA repair, as well as downregulation of genes involved in stem cell maintenance.242 Sexual reproduction in Hydra species, as in vertebrates, is typically triggered or impeded by environmental cues indicative of proteotoxic or metabolic stress conditions (caloristasis). Under favorable environmental circumstances, Hydra primarily reproduces through asexual budding and does not exhibit noticeable gametogenesis.243, 244 Sexual reproduction, characterized by increased sperm and/or egg production from interstitial stem cells, can be induced in Hydra by environmental stressors such as food scarcity, crowding, or low temperatures, akin to conditions associated with the onset of winter.245

As organisms age, they frequently encounter functional decline, giving rise to conditions such as sarcopenia, atherosclerosis, heart and kidney failure, osteoporosis, macular degeneration, pulmonary insufficiency, and neurodegeneration, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.177 These conditions all share a common thread: senescence and the SASP. For a comprehensive understanding of the role of SASP, readers are encouraged to consult the thorough review by Tchkonia and colleagues,246 which offers an in-depth perspective. Additionally, Zhu and collaborators have extensively detailed SASP’s involvement in age-related chronic diseases.224 It is noteworthy that Ames dwarf mice possess a 40–60% enhanced lifespan as compared to wild mice. Curiously, these animals concomitantly present an impressive insulin sensitivity in the skeletal muscle and liver.247 This abnormal longevity is associated with altered methionine metabolism in these tissues leading to a complete modification of cysteine metabolism and enhanced antioxidant metabolism as compared to wild mice.248 In contrast to typical aging patterns, it has been shown that the levels of HSF1 protein and mRNA in Ames dwarf mice actually increase as they age and can be further enhanced by exposure to stress! This suggests that exceptional longevity may be linked to compensatory and improved regulation of HSF1 as a response to age-related pressures that would otherwise suppress the heat shock axis,239 as previously pointed out.249 These findings corroborate once again that HSR is strongly linked to energy metabolism,16 as prophesied by Ritossa in his first papers on the effects of heat shock on polytene chromosomes of Drosophila spp.250, 251, 252 and recently confirmed.13, 58, 59