Abstract

Glutamate is a neurotransmitter that can cause excitatory neurotoxicity when its extracellular concentration is too high, leading to disrupted calcium balance and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Cordycepin, a nucleoside adenosine derivative, has been shown to protect against excitatory neurotoxicity induced by glutamate. To investigate its potential neuroprotective effects, the present study employed fluorescence detection and spectrophotometry techniques to analyze primary hippocampal-cultured neurons. The results showed that glutamate toxicity reduced hippocampal neuron viability, increased ROS production, and increased intracellular calcium levels. Additionally, glutamate-induced cytotoxicity activated acetylcholinesterase and decreased glutathione levels. However, cordycepin inhibited glutamate-induced cell death, improved cell viability, reduced ROS production, and lowered Ca2+ levels. It also inhibited acetylcholinesterase activation and increased glutathione levels. This study suggests that cordycepin can protect against glutamate-induced neuronal injury in cell models, and this effect was inhibited by adenosine A1 receptor blockers, indicating that its neuroprotective effect is achieved through activation of the adenosine A1 receptor.

Keywords: Cordycepin, Neuroprotection, Apoptosis, Glutamate, Adenosine A1 receptor

Introduction

Glutamate, a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS), is a key player in regulating normal neural transmission, development, differentiation, and plasticity.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 However, when cells release too much glutamate or the glutamate metabolic cycle is affected, the glutamate present in excessive amounts is capable of inducing toxicity via molecular pathways that may ultimately lead to neurodegeneration and cell death.8, 9 Pathological conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke, and traumatic brain injury,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 typically cause elevations in glutamate release, which results in overactivation of glutamate receptors and becoming oversensitive to glutamate, resulting in a consequent increase in intracellular Ca2+ influx. The resulting excessive Ca2+ concentration represents a central mediator of glutamate toxicity through the overactivation of glutamate receptors,17 and launches a cascade of signaling pathways that leads to neuronal nitric oxide synthase upregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative phosphorylation deregulation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, glutathione (GSH) depletion, and lysosomal enzyme release.18, 19 As an important cause of oxidative stress, excessive ROS production is a major mechanism underlying nervous system disorders.20, 21 The brain has the highest oxygen consumption levels among all organs, which greatly contributes to excessive ROS formation. However, due to its limited antioxidant enzyme activity, the nervous system possesses a weak antioxidant capacity, rendering it vulnerable to oxidative stress.21 Hence, developing drugs that are specifically designed to protect the nervous system from oxidative stress is a promising target for the treatment of neurological diseases.

Cordycepin, an active ingredient in Cordyceps militaris, is also known as 3-deoxyadenosine. For nearly five decades, C militaris has been utilized in health care practices throughout China, Korea, and Japan, and its efficacy in treating a range of ailments has garnered widespread recognition.22, 23, 24, 25 C militaris can benefit the circulatory, immune, respiratory, and glandular systems,26, 27 which possesses beneficial properties including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and hepatoprotective.28, 29, 30, 31 Additionally, cordycepin has been shown to exhibit neuroprotective effects and inhibit excitatory glutamate synaptic transmission.32, 33 Recent evidence suggests that cordycepin can protect against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity,32 and significantly reduce ROS levels while increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes in PC12 cells, thus preventing cells from neurotoxicity.34 These findings suggest that cordycepin exhibits both antioxidant and antiexcitatory effects. Given the close relationship between excitotoxicity and glutamate-induced oxidative stress in the CNS, cordycepin might have a neuroprotective effect against damage induced by glutamate and may prevent the onset of neurodegenerative diseases. Nevertheless, the precise extent of its neuroprotective effects is still unclear and warrants further investigation.

The aim of this investigation was to examine the potential neuroprotective properties of cordycepin against cytotoxicity induced by glutamate in hippocampal neurons and explore the mechanisms underlying this effect.

Results

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced neuronal death

The impact of glutamate concentrations within the range of 0.625–40 mM on the primary neurons' viability was assessed, and a decrease in cell survival rates was observed. As displayed in Figure 1(a), 10, 20, and 40 mM concentrations yielded similar inhibition rates (10 mM: 79.4 ± 4.8%, 20 mM: 77.5 ± 4.6%, 40 mM: 70.2 ± 6.5%, P < 0.01 compared to control group). According to these results, 20 mM glutamate was chosen to establish the model for subsequent experiments. With regards to cordycepin treatment (10–80 μM), Figure 1(b) depicts that the viability of cells treated with different concentrations was comparable to that of the control group. The findings indicated that cordycepin, administered at doses ranging from 10–80 μM, can result in a reduction of cell viability when used alone. However, the viability of the cells remained at a level above 95% when administered at doses of 10–40 μM. In the next phase, the impact of cordycepin on the glutamate-induced neuron injury model was established by studying the impact of different concentrations of cordycepin (10–40 μM) on the glutamate-induced neuron injury model. The results indicated that cordycepin exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in cell viability in the glutamate-induced neuron injury model. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1(c), the cell viability measurements indicated that glutamate at 20 mM decreased cell viability to 78.9 ± 2.5% (P < 0.0001, compared to the control group). However, cordycepin at 10–40 μM significantly prevented glutamate-induced cell death, increasing viability rates to 84.8 ± 1.8%, 85.7 ± 1.3%, and 89.1 ± 1.0%, respectively (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.001, compared to the glutamate-treated group). Unless otherwise stated, cordycepin at a concentration of 40 μM was utilized in subsequent experiments due to its enhanced efficacy in preventing glutamate-induced cell death. Overall, these results suggest that cordycepin could exert a neuroprotective effect on the glutamate-induced neuron injury model.

Fig. 1.

Protective effects of cordycepin on glutamate-induced hippocampal neuronal death. (a) Effect of glutamate concentration on cell viability. (b) Effect of cordycepin concentration on cell viability. (c) Cordycepin treatment significantly prevented glutamate-induced cell death in a concentration-dependent manner. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 versus the control group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus the glutamate-treated group.

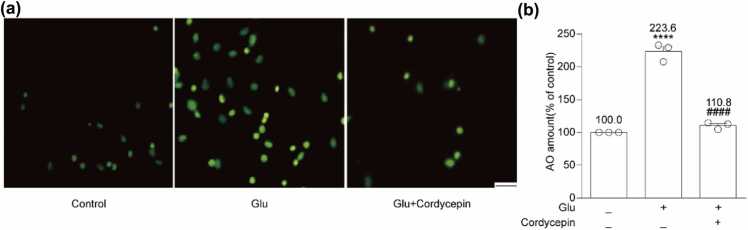

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis

Glutamate exposure can negatively impact neurons and elicit cell apoptosis, which was evident through AO staining. As depicted in Figure 2, the glutamate-treated group evidenced a higher intensity of yellow-green fluorescence relative to the control group (223.6 ± 7.9%, P < 0.0001), indicating that glutamate was capable of inducing cell apoptosis. Nevertheless, the combined action of cordycepin and glutamate produced a considerable reduction in the yellow-green fluorescence intensity compared to the glutamate treatment group (110.8 ± 3.0%, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2). These outcomes suggest that cordycepin has the potential to reduce glutamate-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis. (a) Fluorescence of apoptosis induced by glutamate on hippocampal neurons using AO staining. Scale bar, 200 µm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the histograms expressed as the ratio of AO staining observed by fluorescence microscope in the same field. **** versus the control group; ####P < 0.0001 versus the glutamate-treated group.

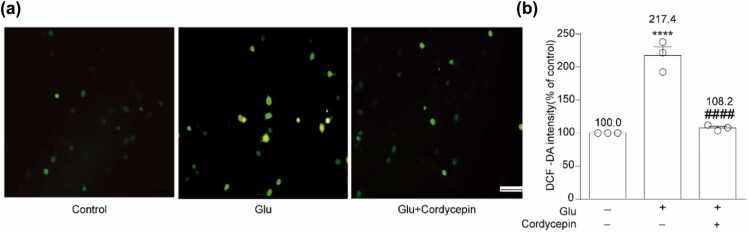

Cordycepin inhibited glutamate-induced ROS production

ROS levels in cells can be utilized to demonstrate the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin. As depicted in Figure 3, 20 mM glutamate substantially increased ROS production compared to the control (217.4 ± 13.2%, P < 0.0001). Nevertheless, cotreatment with cordycepin and glutamate significantly inhibited this induction to 108.2 ± 2.4% (P < 0.0001, compared to the glutamate-treated group). These findings suggest that cordycepin can reverse glutamate-induced neuronal death through an effective reduction of ROS production.

Fig. 3.

Cordycepin inhibited glutamate-induced ROS production. (a) DCF fluorescence, an indicator of the amount of ROS in different treatment group was observed under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar, 200 µm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the histograms expressed as the ratio of DCFH-DA-positive cells observed in the same field. and ****P < 0.0001 versus the control group; ####P < 0.0001 versus the glutamate-treated group. DCFH-DA, 2,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. DCF, dichlorodihydrofluorescein.

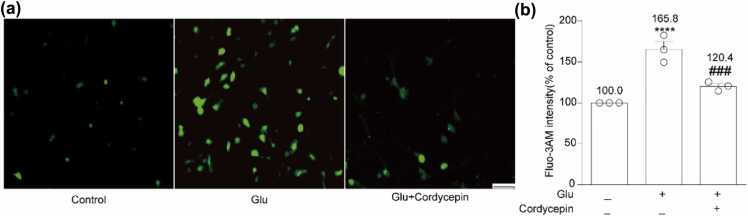

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx

Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity is known to disturb the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, resulting in changes in mitochondrial permeability and function, ultimately leading to cell death. Therefore, we assessed the changes in intracellular calcium concentration. As illustrated in Figure 4, glutamate exposure elevated Ca2+ influx to 165.8 ± 9.5% of the control (P < 0.0001), whereas cotreatment of cordycepin and glutamate significantly reduced Ca2+ influx (120.4 ± 3.2%, P < 0.001) compared to the glutamate group. These results indicate that cordycepin can effectively reverse glutamate-induced apoptosis by inhibiting Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 4.

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx. (a) The cells were treated with Fluo-3AM for 30 min, and Ca2+ fluorescence of different treatment group was observed under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar, 200 µm. (b) Quantitative analysis of the histograms expressed as the ratio of Ca2+ fluorescence intensity observed in the same field. ****P < 0.0001 versus the control group; ###P < 0.001 versus the glutamate-treated group.

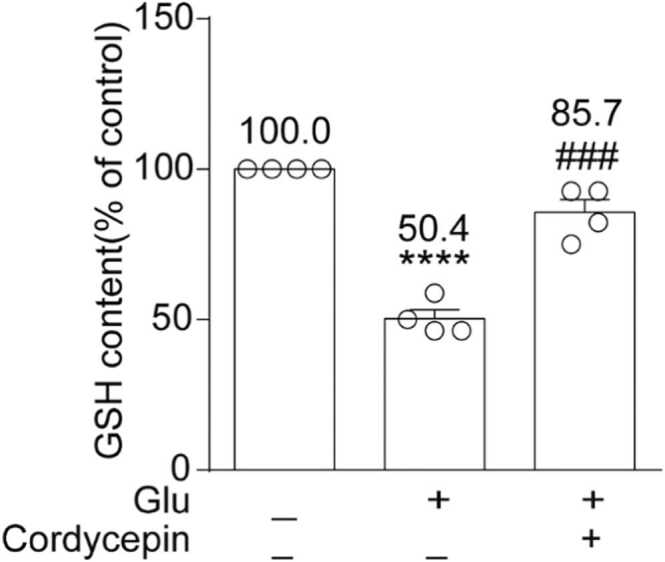

Cordycepin inhibited glutamate-induced GSH consumption

GSH content was estimated by measuring the increasing trend at 420 nm absorbance. After incubating mature neurons with 20 mM glutamate for 6 h, GSH content decreased to 50.4 ± 3.0% of the control (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5). Nonetheless, cordycepin treatment increased GSH content in cells (85.7 ± 4.3%, P < 0.001, compared to the glutamate-treated group). These findings suggest that cordycepin has a neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by limiting GSH consumption.

Fig. 5.

Cordycepin inhibited glutamate-induced GSH consumption. Quantitative analysis of the histograms is expressed as the ratio of the content of GSH in the same field. ****P < 0.0001 versus the control group; ###P < 0.001 versus the glutamate-treated group.

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced AChE overactivity

AChE activity was determined by measuring the increasing trend at 412 nm absorbance. After incubating mature neurons with 20 mM glutamate for 6 h, AChE activity increased to 153.9 ± 17.4% of the control (P < 0.05) (Figure 6). Nevertheless, cordycepin treatment considerably reduced AChE activity in cells (95.7 ± 9.5%, P < 0.05, compared to the glutamate-treated group). These findings suggest that cordycepin exerts a protective effect against glutamate-induced neuron injury by inhibiting excessive AChE activity.

Fig. 6.

Cordycepin reduced glutamate-induced AChE overactivity. Quantitative analysis of the histograms expressed as the ratio of the enzyme activity of AChE in the same field. *P < 0.05 versus the control group; #P < 0.05 versus the glutamate-treated group.

Neuroprotective effects of cordycepin were dependent on adenosine A1 receptor activation

To investigate the connection between cordycepin and adenosine receptors, we mix the specific antagonists of adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) (8 Cyclopentyl 1,3 dipropylxanthine, DPCPX), A2AAR (caffeine), A2BAR (N-(4-cyanophenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipr-opyl-1H-purin-8-yl)-phenoxy]acetamide, MRS 1754), and A3AR (3-Ethyl-5-benzyl-2-methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-phenyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, MRS 1191) with glutamate and cordycepin in the culture medium beforehand and adjust the concentrations for usage. The assessment of cordycepin-mediated neuroprotection using colorimetric and fluorometric methods. As revealed in Figure 7(a), the protective effect of cordycepin on glutamate-induced neuron injury was significantly attenuated by DPCPX (78.8 ± 1.5%), while caffeine (86.8 ± 3.0%), MRS 1754 (88.2 ± 0.9%), and MRS 1191 (89.4 ± 1.0%) had no significant effect. Cordycepin-increased GSH level following glutamate treatment was inhibited upon cotreatment with DPCPX (73.7 ± 5.4%), as shown in Figure 7(b). Moreover, DPCPX blocked cordycepin-induced cytoprotection against excessive AChE activity (156.0 ± 8.0%) (Figure 7[c]). Finally, fluorescence microscopy was used to monitor the fluorescence intensity of intracellular Ca2+ after cotreatment of cordycepin and DPCPX with glutamate, DPCPX hindered the effect of cordycepin in reducing glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx (161.6 ± 6.7%) (Figure 7[d]). Altogether, these observations suggest that cordycepin exerts neuroprotection against glutamate-induced neuron damage by activating A1AR.

Fig. 7.

Neuroprotective effects of cordycepin were dependent on adenosine A1 receptor activation. Adenosine antagonists including DPCPX (adenosine A1 antagonist), caffeine (adenosine A2A antagonist), MRS 1754 (adenosine A2B antagonist), and MRS 1191 (adenosine A3 antagonist) were used. (a) DPCPX prevented the neuroprotection of cordycepin on cell viability in glutamate and cordycepin co-treated cells. (b) DPCPX blocked the protective effect of cordycepin against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by decreasing GSH content. (c) DPCPX blocked the protective effect of cordycepin against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by decreasing AChE overactivity. (d) DPCPX hindered the effect of cordycepin in reducing glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx. *P < 0.05, versus the control group; #P < 0.05 versus the glutamate-treated group. +P < 0.05 versus the glutamate and cordycepin-treated group.

Discussion

Glutamate is a crucial excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS of mammals and plays an important role in the control of motor function, cognition, and emotion. However, under pathological stimuli, the over-release of glutamate can induce oxidative toxicity and oxidative stress, which are major contributors to neurodegenerative diseases.18, 37 Oxidative glutamate toxicity can decrease cellular GSH contents and increase ROS production. To explore the mechanisms behind oxidative toxicity, 20 mM glutamate was adopted to induce oxidative toxicity, which is consistent with previous studies of primary cortical neurons,38 the crayfish neuromuscular junction,39 and mouse hippocampal cell line HT22.40 Also, 40 μM cordycepin was employed to provide reliable evidence for its neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity.

The findings showed that 20 mM glutamate exerted a significant stimulating effect on cell excitotoxicity, primarily characterized by a decline in cell survival rate, an elevation in cell apoptosis (reflected by an increase in AO levels), an enhancement in ROS production (measured by elevated Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) fluorescence intensity), an improvement in cell activity (indicated by increased Fluo-3AM fluorescence intensity), and a depletion of GSH reserves. However, when cordycepin (40 μM) was administered in conjunction with glutamate stimuli, it was observed to inhibit glutamate-induced cell death, enhance cell viability (Figure 1), and reduce apoptosis rates (Figure 2). Moreover, cordycepin exhibited the ability to mitigate ROS production (as evidenced in Figure 3), restore disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis caused by glutamate (Figure 4), and increase GSH content (Figure 5), and reduce excessive AChE activity (Figure 6), thus protecting primary neurons. Additionally, A1R antagonists hindered the protective effect of cordycepin against glutamate-induced neuronal damage (Figure 7), indicating that the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin on the primary neuron injury model depends on the activation of A1Rs. Taken together, these results suggest that cordycepin exerts a prominent protective effect against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by activating A1AR.

Glutamate-induced excitatory toxicity increases intracellular Ca2+ levels, and triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS generation, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Furthermore, dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration is associated with the late cell death pathway induced by glutamate toxicity. Neurons have a weak antioxidant defense system and low endogenous antioxidant enzyme content, rendering them susceptible to ROS-induced damage.41, 42 Besides ROS, Ca2+ influx plays a crucial role in oxidative glutamate toxicity.43 Developing efficient neuroprotective agents through sustained molecular targeting of ROS generation and Ca2+ influx has emerged as a promising approach.44 In this study, we established a neuronal oxidative toxicity model using glutamate as an inducer. Cordycepin was found to effectively reduce oxidative toxicity induced by glutamate and restore Ca2+ homeostasis (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Furthermore, cordycepin mitigated glutamate-induced downstream events, such as a decrease in GSH content (Figure 5), AChE overactivation (Figure 6), and an increase in apoptosis (Figure 2). This suggests that oxidative damage and calcium homeostasis imbalances resulting from ROS can trigger neuronal death or apoptosis.

GSH serves as a vital regulator in the maintenance and control of the intracellular redox status in the brain and plays a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, protecting against oxidative injury.45, 46, 47 Depletion of brain GSH levels disrupts short-term spatial recognition, cognitive flexibility, learning, and memory processes in rodents.48, 49 Moreover, reduced brain GSH concentrations are associated with an increase in oxidative damage, neuron death, nitrogen monoxide (nitrogen monoxide toxicity, and neuroinflammation.48, 50 Our findings reveal that cordycepin can prevent the reduction of GSH content induced by glutamate, substantiating the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin in neurodegenerative diseases (Figure 5).

AChE plays a crucial role in memory and learning, and understanding its function may facilitate the development of effective therapies for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease.47 Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by progressive memory loss and mental deterioration, as evidenced by the excessive activation of AChE. As the AchE level increases, the cognitive function of the nervous system gradually decreases. Oxidative stress may enhance AchE expression, while glutamate can induce oxidative stress. Therefore, the oxidative toxicity of glutamate may cause AchE overactivation.51 Cholinesterase inhibitors prolong the presence of Ach released into the synaptic cleft and improve cholinergic function, resulting in improved cognitive function in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. They can also activate the inhibited cerebral AChE to attenuate the glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and neuropathology caused by high cholinergic activity induced by organophosphorus.52 Additionally, cholinesterase inhibitors such as Donepezil, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as first-line drugs for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. However, people with certain types of cardiac arrhythmias should not take cholinesterase inhibitors, as they may cause side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, cramps, insomnia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, nightmares, or depression,53 while taking these medications with food might help minimize these side effects. Memantine (Namenda) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. It works by regulating the activity of glutamate, the common side effects include dizziness, headache, confusion, and agitation.54, 55 Cordycepin is extracted from cordyceps as food and has no toxicity or side effects.56, 57 Thus, the inhibitory effect of cordycepin on AChE overactivity is considered a critical neuroprotective mechanism against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity.

In this study, we investigated the protective effect and mechanism of cordycepin against glutamate-induced neuron damage and revealed that cordycepin's antiapoptotic effect partly occurs through an adenosine receptor-dependent pathway. Furthermore, this effect appears to require adenosine A1AR but not other adenosine receptors (A2AAR, A2BAR, or A3R). Notably, A1Rs are expressed and extensively distributed in various regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex.37, 58 In the CNS, adenosine activates A1ARs to induce presynaptic inhibition, decrease neuronal excitability and inhibitory neurotransmitter release, reduce Ca2+ influx, and increase the conductance of K+ and Cl−.59 A1AR also plays a critical role in regulating glutamate uptake to prevent excitatory toxicity induced by glutamate accumulation in the brain. A1AR activation can reduce glutamate release and promote ischemic tolerance.60 Moreover, Hao et al35 have demonstrated that the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin on Aβ25-35-induced hippocampal cell injury model can be reversed by an A1AR blocker, implying that the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin on hippocampal cells depends on the activation of A1AR. In this study, we elucidated the mechanism underlying the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin via A1AR-dependent pathways. Our results indicated that DPCPX, a specific A1R antagonist, partially reduced the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin against glutamate-induced neuronal death and inhibited the effects of cordycepin on increasing GSH content and reducing AChE overactivation and Ca2+ influx (Figure 7). Overall, our study suggests that the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin against glutamate-induced hippocampal neuron death partly depends on the activation of A1AR.

To conclude, our study sheds light on the mechanisms behind cordycepin's neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced toxicity in primary hippocampal-cultured neurons. Glutamate-induced apoptosis is associated with oxidative stress and aberrant calcium homeostasis, and cordycepin can mitigate these damages. Cordycepin was able to prevent the depletion of GSH content and overactivity of AChE resulting from glutamate exposure. Notably, the neuroprotective effect of cordycepin on the neuronal injury cell model was partially inhibited by DPCPX, an A1AR antagonist. These findings suggest that cordycepin may safeguard hippocampal neurons from glutamate-induced death via the activation of A1AR.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

All cell culture media and supplements were procured from Gibco, unless stated otherwise. L-Glutamic acid monosodium salt hydrate was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, while cordycepin was purchased from Aladdin. KeyGen Biotech supplied the Acridine Orange Detection Kit and Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit, while Solarbio provided the Acetylcholinesterase Assay Kit. The GSH kit was procured from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute.

Cell culture and drug treatment

The handling and experimentation involving animals in this study were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University (Approval no. SCXK [Shanghai] 2017-0005). Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons were obtained from neonatal SD rats within 72 h of birth, according to a previously described protocol.35 Briefly, hippocampal tissue was separated in precooled Hank's solution, then dissociated with trypsin. The resulting neurons were seeded onto poly-d-lysine-coated (100 μg/mL) Petri dishes at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. After 4–6 h of incubation, the neurobasal medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum was replaced with a neurobasal medium supplemented with B27. The cells were then cultured for 7–14 days at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 before being used for experiments. All experiments were conducted between 7 and 14 days after cell seeding.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay, according to Hu et al.36 Following treatment with the drug, the cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT reagent at 37 °C for 4 h in the dark. Subsequently, the culture medium containing MTT was removed and replaced with dimethyl sulfoxide, which was then incubated at 37 °C for 10 min in the dark. Cell viability was assessed by measuring colorimetric changes with a Thermo Scientific microplate reader (Thermo Lab Systems) at a test wavelength of 492 nm.

Acridine orange staining assay

Morphological changes indicative of apoptosis in glutamate-treated cells were assessed using acridine orange (AO) staining, as described previously.35 Following 7 days of incubation in the culture medium, the cells were treated with drugs for 6 h. Subsequently, they were exposed to 10 μg/mL AO and incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Unbound dye was eliminated by washing the cells three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fluorescence images were then captured using a fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Intracellular levels of ROS were determined using the nonfluorescent probe 2,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. After 7 days of incubation, the neurons were exposed to 20 mM glutamate for 6 h in the presence or absence of 40 μM cordycepin to assess intracellular ROS levels. Next, 2,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate was added to each well in an appropriate volume of culture medium (5 μM) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and fluorescence intensity was assessed using a fluorescence microscope.

Estimation of intracellular Ca2+

The intracellular concentration of Ca2+ was ascertained using Fluo-3AM stock solution in this study. The neurons were cultured with 20 mM glutamate in the presence or absence of 40 μM cordycepin for 6 h and then treated with the prepared working solution (5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min. All procedures were conducted in a dark environment. The cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS, and fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of GSH content

GSH content was assessed using a colorimetric method following drug treatment. After washing the cells three times with PBS, they were incubated with trypsin for 3 min, gently scraped, and collected in a centrifuge tube for centrifugation. The resulting supernatant was discarded, and 0.5–1 mL of PBS was added to the cell pellet. After gentle mixing, the sample was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed, washed 1–2 times, and kept at 4 °C. Next, 0.2 mL of the cell homogenate was mixed thoroughly with 2 mL of reagent I solution (provided in the kit) and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. Subsequently, 1 mL of the supernatant was used for colorimetric reaction, and GSH content was measured using a GSH assay kit.

Measurement of acetylcholinesterase activity

Following drug treatment, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was assessed using the acetylthiocholine iodide substrate colorimetric technique, as reported previously.35 The cells were lysed with buffer that contained 100 mM NaHPO4 (pH = 8.0), ATCh (Adrenocorticotropic Hormone, 75 mM as the substrate), and 10 mM 5,5′-Dithio-bis-(2nitrobenzoic acid) at a ratio of 100:2:5, and then sonicated in an ice bath using an ultrasonic instrument for a duration of 3 s at intervals of 7 s, with a total sonication time of 3 min and a power setting of 300 W. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the supernatant was kept on ice for subsequent analysis. The OD values of the control and test tubes were measured according to the AChE kit instructions, and AChE activity was calculated accordingly.

Statistical analysis

Fluorescence data were analyzed using Image-J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), while SPSS17.0 statistical software (SPSSInc., Chicago, Ill., USA) was utilized for data comparison. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and comparisons between the two or three groups were evaluated by student’s t-test or 1-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance).

Declarations of interest

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31960193, 31660275), Jiangxi “Double Thousand Plan” Cultivation Program for Distinguished Talents in Scientific and Technological Innovation to Lihua Yao (jxsq2019201011), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20202ACBL206029), Key Construction Laboratory Program of Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University (2017ZDPYJD004), The Academic Leader Project of Jiangxi Province (20182BCB22005).

Contributor Information

Chong Chen, Email: Frankeeeechan@outlook.com.

Lihua Yao, Email: yaolh7905@163.com.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Meldrum B.S. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: Review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130:1007S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitney N.P., Peng H., Erdmann N.B., Tian C., Monaghan D.T., Zheng J.C. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors containing Q/R-unedited GluR2 direct human neural progenitor cell differentiation to neurons. FASEB J. 2008;22:2888–2900. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-104661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wegner F., Kraft R., Busse K., Bornschein G., Schwarz J. Glutamate receptor properties of human mesencephalic neural progenitor cells: NMDA enhances dopaminergic neurogenesis in vitro. J Neurochem. 2009;111:204–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06315.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471- 4159.2009.06315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattson M.P. Glutamate and neurotrophic factors in neuronal plasticity and disease. Ann N Y Acad. 2010;1144:97–112. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansson L.C., Åkerman K.E. The role of glutamate and its receptors in the proliferation, migration, differentiation and survival of neural progenitor cells. J Neural Transm. 2014;121:819–836. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampe CS, Mitoma H, Manto M. GABA and Glutamate: Their Transmitter Role in the CNS and Pancreatic Islets [Internet]. GABA And Glutamate - New Developments In Neurotransmission Research. InTech; 2018. 10.5772/intechopen.70958. [DOI]

- 7.Pal M.M. Glutamate: The master neurotransmitter and its implications in chronic stress and mood disorders. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.722323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong X., Wang Y., Qin Z. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:379–387. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J., Wang F., Mai D., Qu S. Molecular mechanisms of glutamate toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.585584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ossowska K., Lorenc-Koci E., Konieczny J., Wolfarth S. The role of striatal glutamate receptors in models of Parkinson’s disease. Amino Acids. 1998;14:11–15. doi: 10.1007/bf01345236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minagar A., Alexander J.S., Kelley R.E., Jennings H.M.H. Proteomic analysis of human cerebral endothelial cells activated by glutamate/MK-801: Significance in ischemic stroke injury. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;38:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong G.S., Li B., Lee D.S., Kim K.H., Lee I.K., Lee K.R., et al. Cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of spinasterol via the induction of heme oxygenase-1 in murine hippocampal and microglial cell lines. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:1587–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J., Chua K.W., Chu C.C., Yu H., Liu C.F. Antioxidant activity of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone provides neuroprotection against glutamate-induced toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blasco H., Mavel S., Corcia P., Gordon P.H. The glutamate hypothesis in ALS: Pathophysiology and drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:3551–3575. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140916120118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerriero R.M., Giza C.C., Rotenberg A. Glutamate and GABA imbalance following traumatic brain injury. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15 doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0545-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang R., Reddy P.H. Role of glutamate and NMDA receptors in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;57:1–7. doi: 10.3233/jad-160763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kritis A.A., Stamoula E.G., Paniskaki K.A., Vavilis T.D. Researching glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in different cell lines: A comparative/collective analysis/study. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng J.J., Lin S.H., Liu Y.T., Lin H.C., Yao C.K. A circuit-dependent ROS feedback loop mediates glutamate excitotoxicity to sculpt the Drosophila motor system. eLife Sci. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/elife.47372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villa K.L., Nedivi E. Glutamate receptors: Not just for excitation. Neuron. 2019;104:1025–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brieger K., Schiavone S., Miller F.J., Krause K.H. Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13659. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinh T.A., Seo Y.H., Choi S., Lee J., Kang K.S. Protective effect of osmundacetone against neurological cell death caused by oxidative glutamate toxicity. Biomolecules. 2021;11:328. doi: 10.3390/biom11020328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Won S.Y., Park E.H. Anti-inflammatory and related pharmacological activities of cultured mycelia and fruiting bodies of Cordyceps militaris. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:555–561. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das S.K., Masuda M., Sakurai A., Sakakibara M. Medicinal uses of the mushroom Cordyceps militaris: Current state and prospects. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui J.D. Biotechnological production and applications of Cordyceps militaris, a valued traditional Chinese medicine. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2015;35:475–484. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2014.900604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai-Hong D., Wen-Jia L.I., Zeng-Zhi L.I., Wen-Juan Y., Tai-Hui L.I., Xing-Zhong L. Cordyceps industry in China: Current status, challenges and perspectives——Jinhu declaration for cordyceps industry development. Mycosystema. 2016;1:1–15. doi: 10.13346/j.mycosystema.150207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joo J.C., Hwang J.H., Jo E., Kim Y.R., Kim D.J., Lee K.B., et al. Cordycepin induces apoptosis by caveolin-1-mediated JNK regulation of Foxo3a in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12211–12224. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das G., Shin H.S., Leyva-Gómez G., Prado M.L.D., Leyva C.P. Cordyceps spp.: A review on its immune-stimulatory and other biological potentials. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:1–31. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.602364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang C.W., Hong T.W., Wang Y.J., Chen K.C., Shen T.L. Ophiocordyceps formosana improves hyperglycemia and depression-like behavior in an STZ-induced diabetic mouse model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J., Li Y.Z., Hylemon P.B., Zhang L.Y., Zhou H.P. Cordycepin inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses by modulating NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:1777–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y., Guo Z., Meng Q., Lu J., Wang N. Cordycepin affects multiple apoptotic pathways to mediate hepatocellular carcinoma cell death. Anti-cancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17:143–149. doi: 10.2174/1871520616666160526114555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng Y., Lian S., Li D., Lin X., Chen B., Wei H., et al. Anti-hepatocarcinoma effect of cordycepin against NDEA-induced hepatocellular carcinomas via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Nrf2/HO-1/NF-κB pathway in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:1868–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin M.L., Park S.Y., Kim Y.H., Oh J.-I., Lee S.J., Park G. The neuroprotective effects of cordycepin inhibit glutamate-induced oxidative and ER stress-associated apoptosis in hippocampal HT22 cells. NeuroToxicology. 2014;41:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao L.H., Huang L.P., Xiong Q.P., Peng H.L., Yuan C.H. Modulation effects of cordycepin on voltage-gated cation channels on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron. Latin Am J Pharm. 2014;33:954–959. doi: 10.1155/2017/2459053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olatunji O.J., Feng Y., Olatunji O., Tang J., Ouyang Z., Su Z. Cordycepin protects PC12 cells against 6-hydroxydopamine induced neurotoxicity via its antioxidant properties. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;81:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hao S., Huang L.P., Li Y., Chao L., Wang S., Wei M., et al. Neuroprotective effects of cordycepin inhibit Aβ-induced apoptosis in hippocampal neurons. NeuroToxicology. 2018;68:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu S., Cui W., Mak S., Tang J., Choi C., Pang Y., et al. Bis(propyl)-cognitin protects against glutamate-induced neuro-excitotoxicity via concurrent regulation of NO, MAPK/ERK and PI3-K/Akt/GSK3β pathways. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobaben S., Grohm J., Seiler A., Conrad M., Plesnila N., Culmsee C. Bid-mediated mitochondrial damage is a key mechanism in glutamate-induced oxidative stress and AIF-dependent cell death in immortalized HT-22 hippocampal neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:282–292. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y.M., Bhavnani B.R. Glutamate-induced apoptosis in primary cortical neurons is inhibited by equine estrogens via down-regulation of caspase-3 and prevention of mitochondrial cytochrome c release. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsch L, Ishizaki S, Frasca A. Preliminary evidence that riluzole protects against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. Pioneering Neuroscience. 2020;18:3944. https://ojs.grinnell.edu/index.php/pnsj/article/view/491.html [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J., Feng J., Ma D., Wang F., Wang Y., Li C., et al. Neuroprotective mitochondrial remodeling by AKAP121/PKA protects HT22 cell from glutamate-induced oxidative stress. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:5586–5607. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia J., Xiao Y., Wang W., Qing L., Xu Y., Song H., et al. Differential mechanisms underlying neuroprotection of hydrogen sulfide donors against oxidative stress. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cobley J.N., Fiorello M.L., Bailey D.M. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2018;15:490–503. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng J., Wang P., Ge H., Qu X., Jin X. Effects of cordycepin on the microglia-overactivation-induced impairments of growth and development of hippocampal cultured neurons. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh P.O. Ischemic injury decreases parvalbumin expression in a middle cerebral artery occlusion animal model and glutamate-exposed HT22 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2012;512:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Currais A., Maher P. Functional consequences of age-dependent changes in glutathione status in the brain. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013;19:813–822. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ronaldson P.T., Davis T.P. Targeting transporters: Promoting blood-brain barrier repair in response to oxidative stress injury. Brain Res. 2015;1623:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavalcante S.Fd.A., Simas A.B.C., Barcellos M.C., de Oliveira V.G.M., Sousa R.B., Cabral P.Ad.M., et al. Acetylcholinesterase: The "Hub" for neurodegenerative diseases and chemical weapons convention. Biomolecules. 2020;10:E414. doi: 10.3390/biom10030414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gf A., Lb B., Cif B., Ll A., Ts A., Jlf C. Glutathione depletion: Starting point of brain metabolic stress, neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2018;137:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J.J., Thiyagarajah M., Song J., Chen C., Herrmann N., Gallagher D., et al. Altered central and blood glutathione in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2022;14 doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-00961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aquilano K., Baldelli S., Cardaci S., Rotilio G., Ciriolo M.R. Nitric oxide is the primary mediator of cytotoxicity induced by GSH depletion in neuronal cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1043–1054. doi: 10.1242/jcs.077149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang C., Cai X., Hu W., Li Z., Kong F., Chen X., et al. Investigation of the neuroprotective effects of crocin via antioxidant activities in HT22 cells and in mice with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Mol Med. 2019;43:956–966. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olajide O., Gbadamosi I., Yawson E., Arogundade T., Lewu S., Ogunrinola K., et al. Hippocampal degeneration and behavioral impairment during Alzheimer-like pathogenesis involves glutamate excitotoxicity. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71:1205–1220. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01747-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winblad B. Review: Donepezil in severe Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dement. 2009;24:185–192. doi: 10.1177/1533317509332094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danysz W., Quack C.G.P. NMDA channel blockers: Memantine and amino-aklylcyclohexanes: In vivo characterization. Amino Acids. 2000;19:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s007260070045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nikvarz A.G., Padideh Comparing efficacy and side effects of memantine vs. risperidone in the treatment of autistic disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50:19–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim Si K., Kim Sung W.O.N., Lee Su C., Kim Il W. European Patent Office Publ. of Application with search report EP200708330029.; 2007. A Pharmaceutical Composition Comprising Cordycepin for the Treatment and Prevention of Obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong IP, Kim KY, Nam SH, Lee MK. Composition for improving obesity including compounds from Cordyceps militaris having anti-obesity activity. 2013:KR20130049304A.

- 58.Paul S., Khanapur S., Rybczynska A.A., Kwizera C., Sijbesma J.W.A., Ishiwata K., et al. Small-animal PET study of adenosine A1 receptors in rat brain: Blocking receptors and raising extracellular adenosine. J Nuclear Med. 2011;52:1293–1300. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.088005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vincenzi F., Pasquini S., Gessi S., Merighi S., Romagnoli R., Borea P.A., et al. The detrimental action of adenosine on glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells can be shifted towards a neuroprotective role through A1AR positive allosteric modulation. Cells. 2020;9:1242. doi: 10.3390/cells9051242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou X., Li Y., Huang Y., Zhao H., Gui L. Adenosine receptor A1-A2a heteromers regulate EAAT2 expression and glutamate uptake via YY1-induced repression of PPAR γ transcription. PPAR Res. 2020;2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/2410264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.