Abstract

Aims

Atrial fibrillation (AF) increases the risk of heart failure (HF); however, little is known regarding the risk stratification for incident HF in AF patients, especially with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Methods and results

The Fushimi AF Registry is a community-based prospective survey of AF patients. From the registry, 3002 non-valvular AF patients with preserved LVEF and with the data of antero-posterior left atrial diameter (LAD) at enrolment were investigated. Patients were stratified by LAD (<40, 40–44, 45–49, and ≥50 mm) with backgrounds and HF hospitalization incidences compared between groups. Of 3002 patients [mean age, 73.5 ± 10.7 years; women, 1226 (41%); paroxysmal AF, 1579 (53%); and mean CHA2DS2-VASc score, 3.3 ± 1.7], the mean LAD was 43 ± 8 mm. Patients with larger LAD were older and less often paroxysmal AF, with a higher CHA2DS2-VASc score (all P < 0.001). Heart failure hospitalization occurred in 412 patients during the median follow-up period of 6.0 years. Larger LAD was independently associated with a higher HF hospitalization risk [LAD ≥ 50 mm: hazard ratio (HR), 2.36; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.75–3.18; LAD 45–49 mm: HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.37–2.46; and LAD 40–44 mm: HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.01–1.78, compared with LAD < 40 mm) after adjustment by age, sex, AF type, and CHA2DS2-VASc score. These results were also consistent across major subgroups, showing no significant interaction.

Conclusion

Left atrial diameter is significantly associated with the risk of incident HF in AF patients with preserved LVEF, suggesting the utility of LAD regarding HF risk stratification for these patients.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Left atrial enlargement, Echocardiography

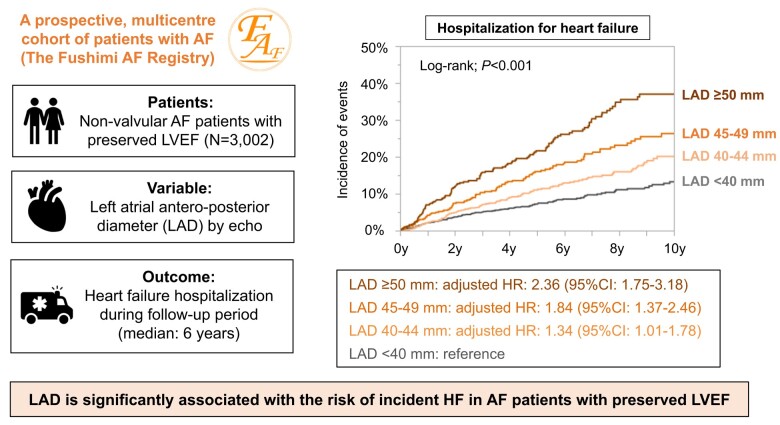

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with the risk of adverse outcomes, such as thromboembolism and heart failure (HF).1 Despite thromboembolism being a well-recognized and preventable complication of AF, HF incidences remain high and are now more common than thromboembolism in the modern anticoagulation era.2,3 Furthermore, HF accounted for a substantial proportion of deaths among patients with AF, far exceeding that of deaths due to thromboembolism.4,5 Therefore, comprehensive incident HF risk stratification and prevention is warranted for AF management in daily practice. We previously reported the utility of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) for predicting HF events in AF patients; however, further risk stratification is required for AF patient management, especially with preserved LVEF.6

Recently, interest has grown in the assessment of left atrial structure and function for the management of patients with AF.7 Our previous study demonstrated that a larger left atrial diameter (LAD), the simplest left atrial enlargement parameter, was significantly associated with thromboembolism risk in patients with non-valvular AF.8 Left atrial enlargement is a proposed diastolic dysfunction marker in HF with preserved ejection fraction9 and is a proven independent predictor of incident HF in the general population.10,11 Left atrial enlargement may predict future HF events in AF patients with preserved LVEF; however, reports of LAD utility in a selected AF cohort are scarce and conflicting.7,12–15

Accordingly, the present study investigated the relationship between LAD and the risk of future HF events among AF patients with preserved LVEF, using data from a large-scale community-based prospective survey of AF patients in Japan, the Fushimi AF Registry.

Methods

Data source

The Fushimi AF Registry is a community-based multicentre prospective observational study of AF patients who visited the participating medical institutions in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, Japan. The details of the Fushimi AF Registry are previously described (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000005834).16,17 In brief, the registry inclusion criterion is documentation of AF on a 12-lead electrocardiogram or Holter monitoring at any time. There were no exclusion criteria. A total of 81 institutions participated in the Fushimi AF Registry, comprising 2 cardiovascular centres (National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center and Ijinkai Takeda Hospital), 10 small- and medium-sized hospitals, and 69 primary care clinics. We attempted to enrol all consecutive patients with AF under regular outpatient care or during admission. Annual collection of the follow-up information was primarily conducted through electronic and/or paper medical record review, with follow-up information collected through contact with patients, relatives, and/or referring physicians by mail or telephone at the discretion of the investigators. Patient enrolment began in March 2011 and ended in May 2017. Patient clinical data were registered on an Internet Database System by the doctors in charge at each institution. Data were automatically checked for missing or contradictory entries and outlying values. Additional checks were performed by clinical research coordinators at the general office of the registry. The study protocol conformed to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines and was approved by the ethical committees of the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center and Ijinkai Takeda Hospital.

Study population and definitions

In the present analysis, patients were investigated whose follow-up data were available as of February 2022. First, we excluded valvular AF patients, which were defined as AF with mitral stenosis or mechanical valve replacement. Then, patients with LVEF < 50% measured by transthoracic echocardiography at enrolment were excluded, since our previous study revealed that LVEF < 50% was independently associated with the higher risk of incident HF.6 Thereafter, patients with LAD data among non-valvular AF patients with preserved LVEF were investigated. Transthoracic echocardiography data, including LAD, LVEF, left ventricular diameter, thickness, and asynergy, were collected at the time of registry enrolment. We did not obtain other echocardiographic data, such as left atrial volume, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, or right ventricular function in the registry. The decision to perform echocardiography was at the discretion of the attending physicians. Left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated by the biplane Simpson method or the Teichholz method using transthoracic echocardiography at each participating institution.6 Left atrial diameter was measured using M-mode or two-dimensional echocardiography, from the posterior aortic wall to the posterior left atrial wall, in the parasternal long-axis view at the end-ventricular systole according to the guideline.18 Patients were divided into four groups, stratified by LAD (<40, 40–44, 45–49, and ≥50 mm) based on our previous study.8 As LAD was not significantly different between males and females in our registry, LAD was not categorized as a sex-specific variable.

Atrial fibrillation type was classified into two groups: paroxysmal AF and sustained AF, defined as the combination of persistent AF and permanent AF.19 Pre-existing HF was defined as the presence of one of the following at enrolment: (i) HF hospitalization history prior to enrolment, (ii) symptom presence due to HF (New York Heart Association functional class ≥2) in association with heart disease, or (iii) reduced LVEF < 40%.20 B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) levels were obtained at the discretion of the attending physicians and measured using the clinical assay of each participating site. For standardization purposes, BNP was converted to NT-proBNP using the following conversion formula: ‘log10(NT-proBNP) is equal to 1.1 × log10(BNP) + 0.570’ based on our previous report.21

Outcomes

The endpoint in this study was HF hospitalization during the follow-up period. Heart failure hospitalization was determined based on history, clinical presentation (symptoms and physical examinations), natriuretic peptide levels, imaging findings including chest X-ray and echocardiography, cardiac catheterization findings, response to HF therapy, and in-hospital course judged by the attending physicians according to the HF guidelines.22,23 Follow-up was continued until death with clinical outcomes defined as the time to the first event.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation when normally distributed and as the median and interquartile range when non-normally distributed. Distribution was assessed using a histogram. Comparisons of differences among groups were performed by the unpaired Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, one-way analysis of variance, or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2 test for dichotomous variables as appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidences of outcomes, and log-rank testing was performed to assess differences among groups. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed to investigate the association between LAD and the incidence of HF hospitalization. Covariates included in multivariable Model 1 were age, sex, AF type (paroxysmal or sustained), and CHA2DS2-VASc score (multivariable Model 1).6 Multivariable Model 2 was adjusted by covariates included in Model 1 and the prescription of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.6 Multivariable Model 3 was adjusted by covariates included in Model 1 and those significantly differed among patients stratified by LAD (i.e. body mass index, history of HF, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and LVEF). Patients were excluded if one or more values were missing in these analyses. The unadjusted and adjusted risks of three LAD groups (LAD: 40–44, 45–49, and ≥50 mm) relative to the LAD < 40 mm for the incidence of HF hospitalization were expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Also, HR per 5 mm increase in LAD was calculated as a continuous variable. Subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, AF type, pre-existing HF, or CHA2DS2-VASc score (≤2 vs. ≥3) were also performed. According to our previous report,8 the association of LAD ≥ 45 mm relative to LAD < 45 mm with incident HF was investigated in this subgroup analysis. Interaction P-values were calculated by univariable Cox regression analysis to examine subgroup heterogeneity. Lastly, the association of LAD with HF hospitalization among patients with data on natriuretic peptide levels (BNP or NT-proBNP) was investigated. Relationships between LAD and log-transformed NT-proBNP were determined by Pearson correlation analysis. A multivariable Cox regression analysis adjusted by covariates included in Model 1 and log-transformed NT-proBNP levels (multivariable Model 4) was performed. Additionally, patients were stratified into four groups according to LAD (≥ or <45 mm) and NT-proBNP levels (≥ or <median value) with the outcomes between these four groups examined. All tests were two-tailed, with a value of P < 0.05 considered significant. All analyses were performed using JMP version 14.2.0.

Results

Study flowchart

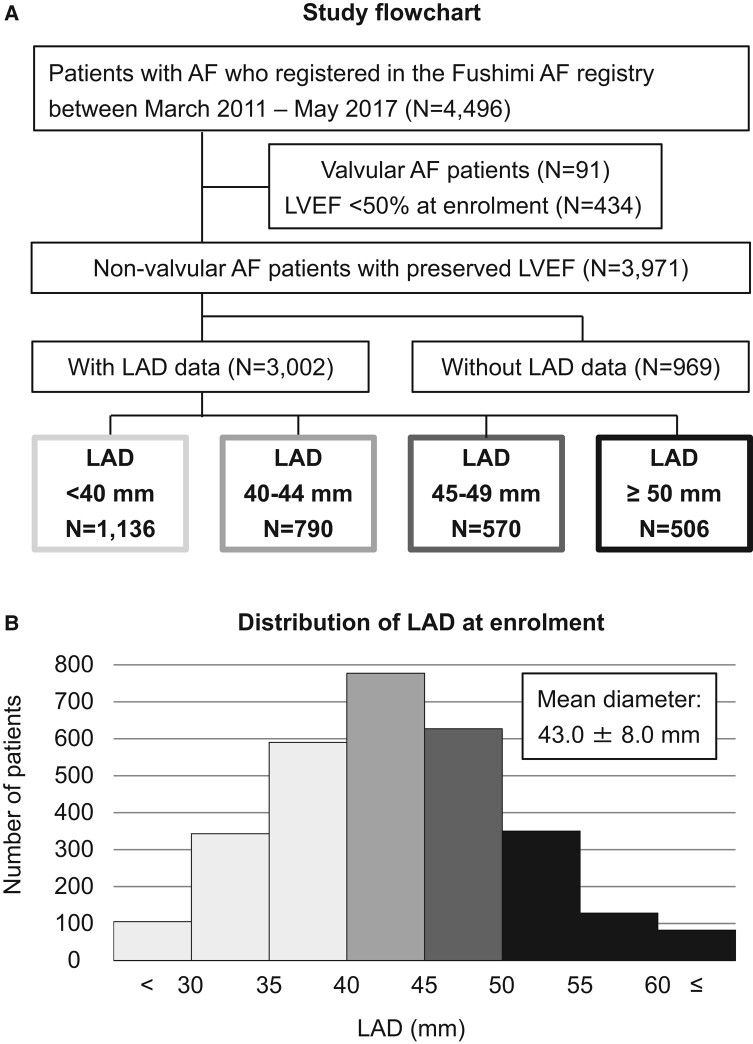

A study flowchart of this analysis is presented in Figure 1A. At enrolment, 91 patients with valvular AF and 434 patients with LVEF < 50% were excluded. Among 3971 non-valvular AF patients with preserved LVEF, at enrolment, LAD data were available for 3002 patients (76% of the total). Table 1 shows the characteristics and outcomes among patients with or without LAD data at enrolment. Patients with LAD data had a higher prevalence of paroxysmal AF, a history of HF, valvular heart disease, and chronic kidney disease, and a higher prescription of oral anticoagulants and HF drugs than those without LAD data. Heart failure hospitalization tended to be higher in patients with LAD data compared with those without it (14% vs. 11%; P = 0.057) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Study flowchart. (B) Distribution of LAD at enrolment in AF patients with preserved LVEF. AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among patients with or without left atrial diameter data among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

| Variables | With LAD data | Without LAD data | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3002 | n = 969 | ||

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 73.5 ± 10.7 | 73.8 ± 11.3 | 0.55 |

| Age ≥ 75 years, n (%) | 1505 (50%) | 506 (52%) | 0.26 |

| Women, n (%) | 1226 (41%) | 401 (41%) | 0.76 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.2 ± 3.9 | 23.2 ± 3.8 | 0.62 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 19 | 129 ± 17 | <0.001 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 78 ± 16 | 79 ± 18 | 0.094 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 1579 (53%) | 458 (47%) | 0.004 |

| Prior catheter ablation, n (%) | 226 (8%) | 43 (4%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| CHADS2 score | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 0.47 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 0.50 |

| Pre-existing HF, n (%) | 701 (23%) | 177 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 366 (12%) | 126 (13%) | 0.51 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 514 (17%) | 47 (5%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 67 (2%) | 12 (1%) | 0.054 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1892 (63%) | 618 (64%) | 0.67 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 1300 (43%) | 438 (45%) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 705 (23%) | 209 (22%) | 0.22 |

| History of stroke/SE, n (%) | 596 (20%) | 194 (20%) | 0.91 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 107 (4%) | 43 (4%) | 0.22 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 1079 (36%) | 258 (27%) | <0.001 |

| COPD, n (%) | 166 (6%) | 40 (4%) | 0.087 |

| Prescription at baseline | |||

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 1684 (56%) | 461 (48%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 1218 (41%) | 353 (37%) | 0.024 |

| DOAC, n (%) | 466 (16%) | 108 (11%) | <0.001 |

| ACEi/ARB, n (%) | 1306 (44%) | 388 (40%) | 0.062 |

| β-blocker, n (%) | 898 (30%) | 219 (23%) | <0.001 |

| MRA, n (%) | 228 (8%) | 52 (5%) | 0.020 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 618 (21%) | 125 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| BNP (ng/L) | 101 (44, 216) | 98 (42, 213) | 0.85 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 739 (260, 1614) | 520 (179, 1234) | 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 60.4 (47.7, 73.2) | 62.5 (50.3, 74.6) | 0.009 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

| Events during follow-up period | |||

| HF hospitalization | 412 (14%) | 110 (11%) | 0.057 |

Categorical data are presented as numbers (%). Continuous data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (25%, 75%).

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-BNP; SE, systemic embolism.

Baseline characteristics stratified by left atrial diameter

Among 3002 non-valvular AF patients with preserved LVEF and LAD data [mean age, 73.5 ± 10.7 years; women, 1226 (41%); paroxysmal AF, 1579 (53%); and mean CHA2DS2-VASc score, 3.3 ± 1.7], LAD distribution at enrolment is shown in Figure 1B. The mean LAD at enrolment was 43 ± 8 mm [LAD < 40 mm, 1136 (38%); LAD 40–44 mm, 790 (26%), LAD 45–49 mm, 570 (19%); and LAD ≥ 50 mm, 506 (17%)]. Median LAD at enrolment was 43 mm (interquartile range: 38–47 mm). Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics according to the four LAD strata. Patients with larger LAD were older, had a lower prevalence of paroxysmal AF, and had higher CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores (all P < 0.001). N-terminal pro-BNP levels were higher and LVEF lower in patients with larger LAD strata (both P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics stratified by left atrial diameter at enrolment

| LAD | LAD | LAD | LAD | P-value | Data missing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 mm | 40–44 mm | 45–49 mm | ≥50 mm | |||

| n = 1136 | n = 790 | n = 570 | n = 506 | |||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 72.1 ± 11.5 | 73.4 ± 10.3 | 74.6 ± 9.7 | 75.9 ± 9.6 | <0.001 | 0 |

| Age ≥ 75 years, n (%) | 513 (45%) | 380 (48%) | 305 (54%) | 307 (61%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Women, n (%) | 483 (43%) | 307 (39%) | 225 (39%) | 211 (42%) | 0.36 | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.9 ± 3.5 | 23.7 ± 3.8 | 24.0 ± 3.8 | 24.2 ± 4.5 | <0.001 | 391 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 18 | 125 ± 19 | 126 ± 20 | 125 ± 19 | 0.62 | 19 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 78 ± 15 | 78 ± 17 | 78 ± 16 | 77 ± 15 | 0.75 | 36 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 840 (74%) | 425 (54%) | 218 (38%) | 96 (19%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Prior catheter ablation, n (%) | 105 (9%) | 67 (8%) | 37 (6%) | 17 (3%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| CHADS2 score | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 0 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | 0 |

| Pre-existing HF, n (%) | 169 (15%) | 175 (22%) | 140 (25%) | 217 (43%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 121 (11%) | 103 (13%) | 78 (14%) | 64 (13%) | 0.23 | 0 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 96 (8%) | 129 (16%) | 122 (21%) | 167 (33%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 15 (1%) | 17 (2%) | 11 (2%) | 24 (5%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 649 (57%) | 528 (67%) | 381 (67%) | 334 (66%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 486 (43%) | 362 (46%) | 259 (45%) | 193 (38%) | 0.033 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 223 (20%) | 212 (27%) | 147 (26%) | 123 (24%) | 0.001 | 0 |

| History of stroke/SE, n (%) | 204 (18%) | 156 (20%) | 109 (19%) | 127 (25%) | 0.009 | 0 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 36 (3%) | 23 (3%) | 23 (4%) | 25 (5%) | 0.20 | 0 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 342 (30%) | 289 (37%) | 215 (38%) | 233 (46%) | <0.001 | 0 |

| COPD, n (%) | 72 (6%) | 39 (5%) | 29 (5%) | 26 (5%) | 0.51 | 0 |

| Prescription at enrolment | ||||||

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 530 (47%) | 427 (54%) | 369 (65%) | 358 (71%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 342 (30%) | 297 (38%) | 272 (48%) | 307 (61%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| DOAC, n (%) | 188 (17%) | 130 (17%) | 97 (17%) | 51 (10%) | 0.003 | 17 |

| ACEi/ARBs, n (%) | 419 (37%) | 352 (45%) | 273 (48%) | 262 (52%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| β-blockers, n (%) | 277 (24%) | 250 (32%) | 196 (35%) | 175 (35%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| MRAs, n (%) | 62 (5%) | 47 (6%) | 53 (9%) | 66 (13%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 133 (12%) | 145 (18%) | 150 (27%) | 190 (38%) | <0.001 | 17 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| BNP (ng/L) | 56 (28, 121) | 93 (38, 194) | 161 (73, 290) | 150 (73, 314) | <0.001 | 2557 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 426 (132, 1145) | 751 (300, 1742) | 983 (536, 2031) | 1160 (564, 2066) | <0.001 | 1995 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 64 (52, 78) | 60 (47, 73) | 58 (47, 70) | 55 (42, 69) | <0.001 | 148 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 12.6 ± 2.1 | <0.001 | 136 |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 44 ± 5 | 46 ± 5 | 46 ± 5 | 48 ± 6 | <0.001 | 12 |

| LVEF (%) | 67 ± 7 | 66 ± 7 | 66 ± 7 | 65 ± 7 | <0.001 | 24 |

| LAD (mm) | 35 ± 4 | 43 ± 1 | 47 ± 1 | 55 ± 5 | <0.001 | 0 |

Categorical data are presented as numbers (%). Continuous data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (25%, 75%).

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-BNP; SE, systemic embolism.

Association of left atrial diameter with the incidence of heart failure among atrial fibrillation patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

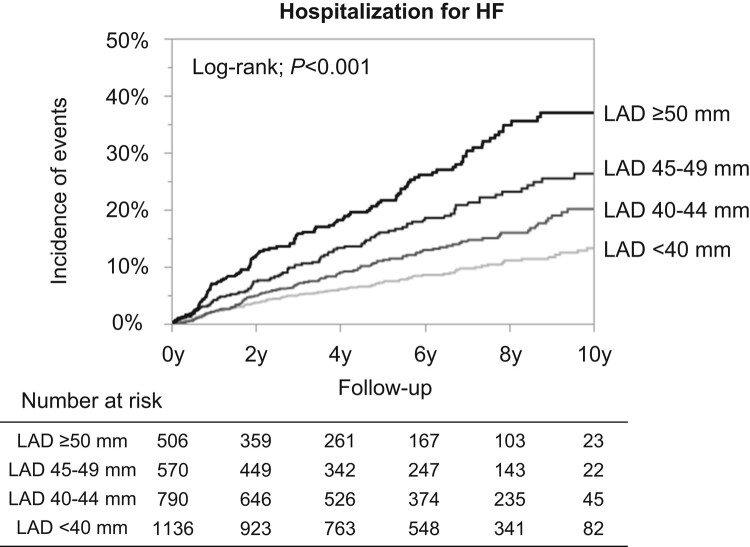

During a median follow-up period of 6.0 years (interquartile range: 3.0–9.0 years), a total of 412 HF hospitalization cases developed among AF patients with preserved LVEF, corresponding to an annual incidence of 2.6% per person-year. Patients with larger LAD strata had a higher incidence of HF hospitalization during the follow-up period (Table 3). Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated that the four LAD strata stratified the incidence of HF hospitalization during the follow-up period (log-rank; P < 0.001) (Figure 2). A larger LAD was significantly associated with a higher HF hospitalization risk in a ‘dose–response’ manner. Cox regression analyses revealed that larger LAD was independently associated with increased HF hospitalization risk, even after multivariable Model 1 adjustment (Table 3). Larger LAD was significantly associated with the risk of incident HF even after adjustment by the prescription at enrolment, or covariates significantly differed among the patients stratified by LAD (Table 3). Left atrial diameter remained an independent determinant of HF hospitalization even when analysed as a continuous variable. When LAD was indexed by body surface area, indexed LAD remained significantly associated with a higher HF hospitalization risk (HR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.46–1.69 per 5 mm/m2; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis for the incidence of heart failure hospitalization

| Events/no. at risk | Incidence ratea | Univariable | Multivariable Model 1 | Multivariable Model 2 | Multivariable Model 3 | Multivariable Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| LAD < 40 mm | 95/1136 | 1.5 | Reference | <0.001 | Reference | <0.001 | Reference | <0.001 | Reference | 0.003 | Reference | 0.005 |

| LAD 40–44 mm | 101/790 | 2.3 | 1.52 (1.15–2.02) | 1.34 (1.01–1.78) | 1.34 (1.01–1.78) | 1.24 (0.92–1.67) | 1.41 (0.98–2.03) | |||||

| LAD 45–49 mm | 98/570 | 3.3 | 2.21 (1.67–2.94) | 1.84 (1.37–2.46) | 1.68 (1.25–2.26) | 1.62 (1.19–2.22) | 1.73 (1.19–2.51) | |||||

| LAD ≥ 50 mm | 118/506 | 5.1 | 3.39 (2.59–4.44) | 2.36 (1.75–3.18) | 2.22 (1.64–2.99) | 1.77 (1.27–2.46) | 1.95 (1.32–2.87) | |||||

| As continuous variablesb | — | — | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.15–1.30) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.05–1.21) | <0.001 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) | 0.001 |

Multivariable Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, type of AF, and CHA2DS2-VASc score. Multivariable Model 2 was adjusted for covariates included in Model 1 and the prescription of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Multivariable Model 3 was adjusted for covariates included in Model 1 and covariates significantly differed across the patients stratified by LAD (body mass index, history of HF, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and left ventricular ejection fraction). Multivariable Model 4 was adjusted for covariates included in Model 1 and log-transformed N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide levels.

CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; LAD, left atrial diameter.

aPercent per person-year.

bHazard ratio was calculated per 5 mm LAD increase.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidences of HF hospitalization according to the LAD strata. HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter.

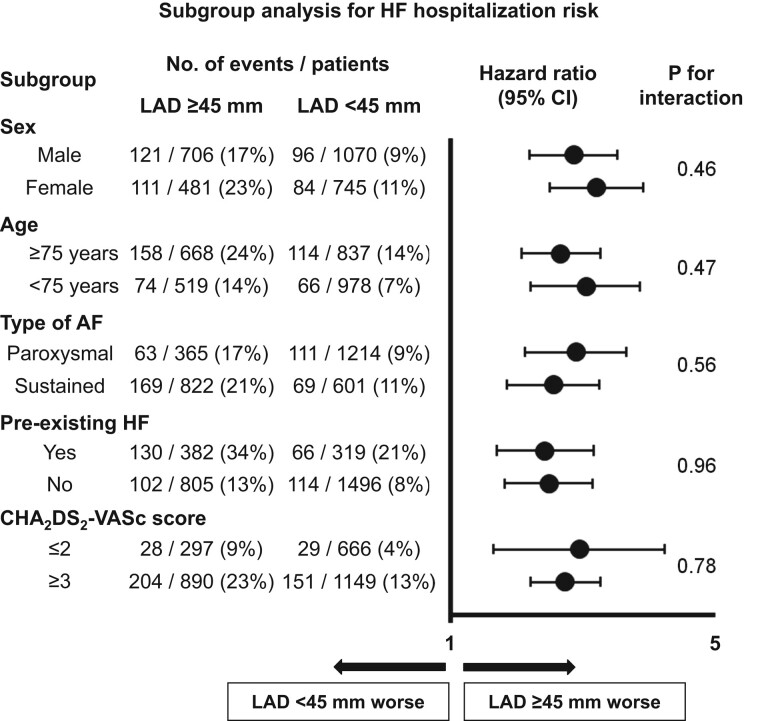

The association between LAD ≥ 45 mm and the incidence of HF hospitalization stratified by major patients’ characteristics is shown in Figure 3. Left atrial diameter ≥ 45 mm was significantly associated with a higher HF hospitalization risk across all major subgroups without significant interaction (P for interaction; all P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Association of LAD ≥ 45 mm with HF hospitalization among major subgroups. AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter.

Patients with the data of natriuretic peptide levels

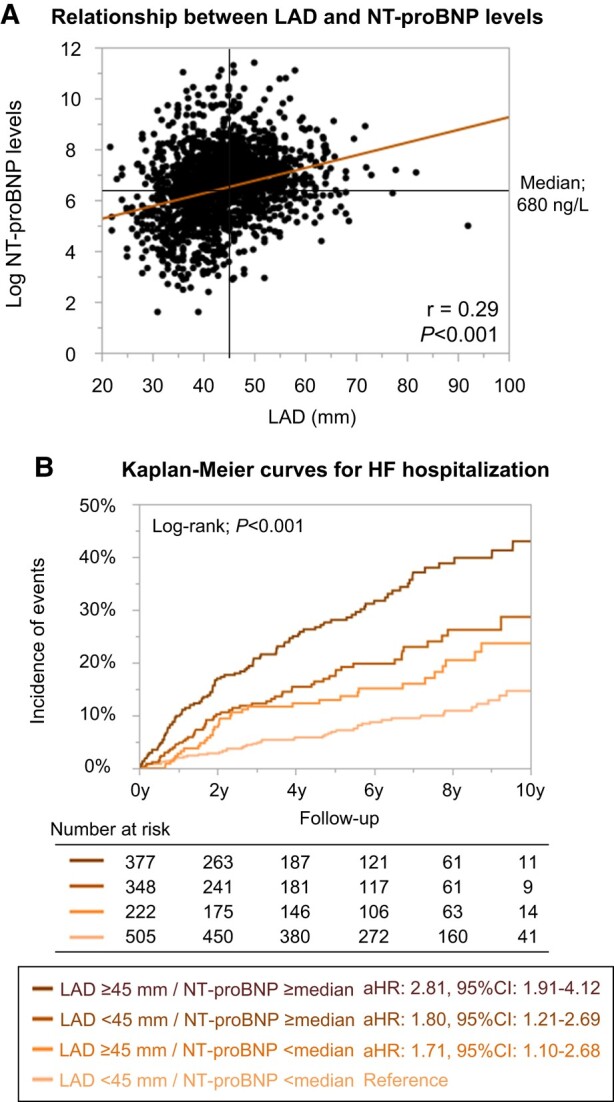

Among 3002 AF patients with preserved LVEF, natriuretic peptide levels were available for 1452 (445 with BNP levels and 1007 with NT-proBNP levels). The NT-proBNP levels had positive correlation with LAD (r = 0.29, P < 0.001) (Figure 4A). The four LAD strata (<40, 40–44, 45–49, and ≥50 mm) were significantly associated with HF hospitalization risk even after multivariable analysis adjustment including NT-proBNP levels (multivariable Model 4) (Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier curves among patients divided by LAD (≥ or <45 mm) and NT-proBNP levels [≥ or <median value (680 ng/L)] revealed these four groups stratified the HF hospitalization risk during the follow-up period (log-rank; P < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Relationship between LAD and NT-proBNP levels. (B) Kaplan–Meier curves for HF hospitalization incidences stratified by LAD and NT-proBNP levels. Log-transformed NT-proBNP had positive correlation with LAD (log-transformed NT-proBNP = 4.27 + 0.05*LAD). aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; LAD, left atrial diameter; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

In the present study, a significant association between LAD and increased HF event risk in AF patients with preserved LVEF was demonstrated. This association was consistent across major subgroups. Left atrial diameter yielded an independent and incremental prognostic value for HF hospitalization in addition to natriuretic peptide levels in AF patients with preserved LVEF.

The association between left atrial size and heart failure events in atrial fibrillation patients

The incidence of HF has recently increased, despite advances in AF patient management.2 Thus, to improve AF patient outcomes, risk stratification and prevention of incident HF is of clinical importance. Echocardiography is central in screening and management among AF patients and may be useful for HF event risk stratification in these patients. We previously demonstrated that reduced LVEF is an independent incident HF predictor for AF patients.6 However, the majority of AF patients had preserved LVEF,6 and further risk stratification is strongly warranted for these patients.

Left atrial diameter is a simple and reproducible measure of left atrial size and has been widely used and routinely measured in daily practice.24 Although left atrial volume is recommended for the assessment of left atrial size,18 LAD showed high reproducibility and was reported to have a strong correlation with left atrial volume.24–26 Thus, we believe that the exploration for the relationship between LAD and incident HF is of significance in clinical practice of patients with AF.

Our previous report using a machine learning technique found LAD to be an important variable for HF risk stratification in AF patients.27 A previous multicentre cohort study demonstrated a significant association between a mildly dilated left atrium (LAD: 40–44 mm) and incident HF in AF patients without left atrial enlargement (LAD ≥ 45 mm).13 On the other hand, another study reported that LAD was not a significant predictor of future cardiovascular events including HF in patients with AF, despite it being an independent predictor in patients with sinus rhythm.14 A recent systematic review reported conflicting results between studies regarding the association of LAD with HF events in AF patients, as well as those regarding left atrial volume.15 Of note, these previous studies were small (with <1000 participants) and with a relatively short duration follow-up period, limiting the ability to evaluate the association between left atrial enlargement and HF events in AF patients. The strength of this study is that our registry included over 3000 patients and had a long-term follow-up period (the median follow-up period was over 5 years). The present results using a large-scale registry with a long-term follow-up period demonstrated that LAD is an important echocardiographic parameter for incident HF risk stratification among AF patients with preserved LVEF.

Potential mechanisms and clinical implications

The left atrium is commonly considered a buffer chamber between pulmonary circulation and the left ventricle. Chronic exposure to high left ventricular filling pressure initiates an adaptive process leading to left atrial enlargement.28 Thus, left atrial size is thought to be related to left ventricular filling pressure and severity of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, which is strongly associated with the risk of future HF events.29,30 Indeed, left atrial enlargement is a proposed parameter for HF diagnosis with preserved ejection fraction.

Besides, AF itself reportedly causes atrial fibrosis, leading to left atrial structural remodelling.31,32 Thus, patients with high AF burden may develop progressive left atrial enlargement independent of impaired left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Considering this, left atrial size is thought to be a marker not only of diastolic dysfunction but also of AF burden in patients with AF. Previous studies, including ours, reported a significant association between sustained AF, strongly related to AF burden, and a higher HF event risk in patients with AF.19,33 In this regard, left atrial enlargement may be related to HF development susceptibility through the representation of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and/or AF burden.

Although out of the scope of our analysis, reducing HF events in AF patients with left atrial enlargement requires future evaluation. Recently, novel HF drugs became available in clinical practice and may be an option for these patients.34,35 Additionally, catheter ablation for AF, shown to improve HF outcomes in selected AF patients with reduced LVEF, may also be an attractive therapy.36 However, whether these treatments can improve outcomes in AF patients with dilated LAD requires further study. Notably, left atrial enlargement is another parameter for AF recurrence after rhythm control therapy.37 Thus, the decision to perform rhythm control therapy in AF patients with preserved LVEF and left atrial enlargement requires case-by-case determination.

Value of left atrial diameter in addition to natriuretic peptide levels

Natriuretic peptide levels are the strongest outcome predictor in patients with HF.34,35 Also, we previously demonstrated a significant association between natriuretic peptide levels and risk of future HF events in AF patients, even without pre-existing HF.21 Natriuretic peptide levels may be a confounder regarding the association between LAD and HF events, but no prior study has been able to adjust for natriuretic peptide concentrations. Our study demonstrated that LAD is independent and incremental in predicting incident HF in addition to natriuretic peptide levels. Our previous studies combined with this analysis suggest the utility of combining natriuretic peptide levels, LVEF, and LAD for HF event risk stratification and prevention in AF patients.6,21

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, this was an observational study and provided only associative evidence, not causative. The possibility of unmeasured or residual confounding factors cannot be ruled out. Besides, this registry was started before the launch of direct oral anticoagulants and had low prescription rates of oral anticoagulants. Thus, the generalizability of the results may be limited. Second, the decision to perform echocardiography was entirely at the discretion of the attending physicians. Indeed, there are some differences between patients with or without LAD data, resulting in unavoidable selection bias. Third, only the left atrial anterior–posterior diameter was measured in the registry. Left atrial volume is a more reliable estimator of left atrial size and was recommended in the current guideline when assessing left atrial size, as left atrial dilatation can be eccentric. Unfortunately, left atrial volume was not obtained in the registry and lack of this important data was a major limitation of this study. Fourth, diastolic dysfunction data, such as tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient or E/e′, right ventricular function, or the details of valvular heart diseases were not obtained. Also, there were some missing data regarding the drug prescription and laboratory data. Although our results were consistent even after excluding the corresponding institution with many missing data, the missing data unavoidably led to some selection bias and this was another major limitation of the study. Fifth, echocardiographic data were not obtained at the incidence of HF hospitalization nor during follow-up period. Thus, it was not possible to address the change of LAD and classify HF hospitalization type according to LVEF. Sixth, there was no data about cardiac rhythm at the time of index echocardiography and echocardiographic data were site reported. Thus, the possibility exists for measurement error or echocardiographic measurement variation.

Conclusions

Left atrial enlargement at enrolment is significantly associated with HF hospitalization risk in AF patients with preserved LVEF, suggesting the utility of LAD for future HF event risk stratification.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the efforts of the clinical research coordinators (T. Shinagawa, M. Mitamura, M. Fukahori, M. Kimura, M. Fukuyama, C. Kamata, and N. Nishiyama).

Contributor Information

Yasuhiro Hamatani, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Moritake Iguchi, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Keita Okamoto, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Yumiko Nakanishi, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Kimihito Minami, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Kenjiro Ishigami, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Syuhei Ikeda, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Kosuke Doi, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Takashi Yoshizawa, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Yuya Ide, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Akiko Fujino, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Mitsuru Ishii, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Nobutoyo Masunaga, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Masahiro Esato, Department of Arrhythmia, Ogaki Tokushukai Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Hikari Tsuji, Tsuji Clinic, Kyoto, Japan.

Hiromichi Wada, Division of Translational Research, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan.

Koji Hasegawa, Division of Translational Research, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan.

Mitsuru Abe, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Masaharu Akao, Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, 1-1, Mukaihata-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, 612-8555, Japan.

Lead author biography

Yasuhiro Hamatani graduated from Kyoto University and started his career at Kyoto Medical Center. Thereafter, he trained at the National Cardiovascular Center. Currently, he works at Kyoto Medical Center as a staff cardiologist. His research interests are heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and echocardiography.

Yasuhiro Hamatani graduated from Kyoto University and started his career at Kyoto Medical Center. Thereafter, he trained at the National Cardiovascular Center. Currently, he works at Kyoto Medical Center as a staff cardiologist. His research interests are heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and echocardiography.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contribution

Y.H. is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. Y.H. led the study design and data analysis and wrote the manuscript. Mo.I., K.O., Y.N., K.M., K.I., S.I., K.D., T.Y., Y.I., A.F., Mi.I., N.M., M.E., H.T., H.W., K.H., H.W., and Mi.A. contributed substantially to data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Ma.A. is a chief investigator of the registry, is a supervisor of the manuscript, and had full access to all of the data in the study.

Funding

The Fushimi AF Registry is supported by research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis Pharma, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. This study was partially supported by the Practical Research Project for Life-Style related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (19ek0210082h0003 and 18ek0210056h0003) (Ma.A.).

References

- 1. Odutayo A, Wong CX, Hsiao AJ, Hopewell S, Altman DG, Emdin CA. Atrial fibrillation and risks of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;354:i4482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akao M, Ogawa H, Masunaga N, Minami K, Ishigami K, Ikeda S, Doi K, Hamatani Y, Yoshizawa T, Ide Y, Fujino A, Ishii M, Iguchi M, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Tsuji H, Esato M, Abe M. 10-year trends of antithrombotic therapy status and outcomes in Japanese atrial fibrillation patients - the Fushimi AF Registry. Circ J 2022;86:726–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piccini JP, Hammill BG, Sinner MF, Hernandez AF, Walkey AJ, Benjamin EJ, Curtis LH, Heckbert SR. Clinical course of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the importance of cardiovascular events beyond stroke. Eur Heart J 2014;35:250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. An Y, Ogawa H, Yamashita Y, Ishii M, Iguchi M, Masunaga N, Esato M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Abe M, Lip GYH, Akao M. Causes of death in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: the Fushimi Atrial Fibrillation Registry. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2019;5:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gómez-Outes A, Lagunar-Ruíz J, Terleira-Fernández AI, Calvo-Rojas G, Suárez-Gea ML, Vargas-Castrillón E. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2508–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamatani Y, Iguchi M, Minami K, Ishigami K, Esato M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Ogawa H, Abe M, Lip GYH, Akao M. Utility of left ventricular ejection fraction in atrial fibrillation patients without pre-existing heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2023;10:3091–3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inciardi RM, Giugliano RP, Claggett B, Gupta DK, Chandra A, Ruff CT, Antman EM, Mercuri MF, Grosso MA, Braunwald E, Solomon SD. Left atrial structure and function and the risk of death or heart failure in atrial fibrillation. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1571–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamatani Y, Ogawa H, Takabayashi K, Yamashita Y, Takagi D, Esato M, Chun Y-H, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Abe M, Lip GYH, Akao M. Left atrial enlargement is an independent predictor of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep 2016;6:31042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF III, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Alexandru Popescu B, Waggoner AD. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;17:1321–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gupta S, Matulevicius SA, Ayers CR, Berry JD, Patel PC, Markham DW, Levine BD, Chin KM, de Lemos JA, Peshock RM, Drazner MH. Left atrial structure and function and clinical outcomes in the general population. Eur Heart J 2013;34:278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoit BD. Left atrial size and function: role in prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taniguchi N, Miyasaka Y, Suwa Y, Harada S, Nakai E, Kawazoe K, Shiojima I. Usefulness of left atrial volume as an independent predictor of development of heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2019;124:1430–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Potpara TS, Polovina MM, Licina MM, Marinkovic JM, Lip GY. Predictors and prognostic implications of incident heart failure following the first diagnosis of atrial fibrillation in patients with structurally normal hearts: the Belgrade Atrial Fibrillation Study. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsang TS, Abhayaratna WP, Barnes ME, Miyasaka Y, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Seward JB. Prediction of cardiovascular outcomes with left atrial size: is volume superior to area or diameter? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Froehlich L, Meyre P, Aeschbacher S, Blum S, Djokic D, Kuehne M, Osswald S, Kaufmann BA, Conen D. Left atrial dimension and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with and without atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2019;105:1884–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akao M, Chun YH, Wada H, Esato M, Hashimoto T, Abe M, Hasegawa K, Tsuji H, Furuke K. Current status of clinical background of patients with atrial fibrillation in a community-based survey: the Fushimi AF Registry. J Cardiol 2013;61:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akao M, Chun YH, Esato M, Abe M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K. Inappropriate use of oral anticoagulants for patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ J 2014;78:2166–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt J-U. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. An Y, Ogawa H, Esato M, Ishii M, Iguchi M, Masunaga N, Aono Y, Ikeda S, Doi K, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Abe M, Lip GYH, Akao M. Age-dependent prognostic impact of paroxysmal versus sustained atrial fibrillation on the incidence of cardiac death and heart failure hospitalization (the Fushimi AF Registry). Am J Cardiol 2019;124:1420–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iguchi M, Tezuka Y, Ogawa H, Hamatani Y, Takagi D, An Y, Unoki T, Ishii M, Masunaga N, Esato M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Abe M, Lip GYH, Akao M. Incidence and risk factors of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure - the Fushimi AF Registry. Circ J 2018;82:1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamatani Y, Iguchi M, Ueno K, Aono Y, Esato M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Ogawa H, Abe M, Morita S, Akao M. Prognostic significance of natriuretic peptide levels in atrial fibrillation without heart failure. Heart 2021;107:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. JCS Joint Working Group . Guidelines for treatment of acute heart failure (JCS 2011). Circ J 2013;77:2157–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsutsui H, Isobe M, Ito H, Ito H, Okumura K, Ono M, Kitakaze M, Kinugawa K, Kihara Y, Goto Y, Komuro I, Saiki Y, Saito Y, Sakata Y, Sato N, Sawa Y, Shiose A, Shimizu W, Shimokawa H, Seino Y, Node K, Higo T, Hirayama A, Makaya M, Masuyama T, Murohara T, Momomura S-i, Yano M, Yamazaki K, Yamamoto K, Yoshikawa T, Yoshimura M, Akiyama M, Anzai T, Ishihara S, Inomata T, Imamura T, Iwasaki Y-k, Ohtani T, Onishi K, Kasai T, Kato M, Kawai M, Kinugasa Y, Kinugawa S, Kuratani T, Kobayashi S, Sakata Y, Tanaka A, Toda K, Noda T, Nochioka K, Hatano M, Hidaka T, Fujino T, Makita S, Yamaguchi O, Ikeda U, Kimura T, Kohsaka S, Kosuge M, Yamagishi M, Yamashina A. JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure - digest version. Circ J 2019;83:2084–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Canciello G, de Simone G, Izzo R, Giamundo A, Pacelli F, Mancusi C, Galderisi M, Trimarco B, Losi M-A. Validation of left atrial volume estimation by left atrial diameter from the parasternal long-axis view. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iliadis C, Baldus S, Kalbacher D, Boekstegers P, Schillinger W, Ouarrak T, Zahn R, Butter C, Zuern CS, von Bardeleben RS, Senges J, Bekeredjian R, Eggebrecht H, Pfister R. Impact of left atrial diameter on outcome in patients undergoing edge-to-edge mitral valve repair: results from the German TRAnscatheter Mitral valve Interventions (TRAMI) registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mills H, Espersen K, Jurlander R, Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Raja AA. Prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: risk assessment using left atrial diameter predicted from left atrial volume. Clin Cardiol 2020;43:581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamatani Y, Nishi H, Iguchi M, Esato M, Tsuji H, Wada H, Hasegawa K, Ogawa H, Abe M, Fukuda S, Akao M. Machine learning risk prediction for incident heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. JACC Asia 2022;2:706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Appleton CP, Galloway JM, Gonzalez MS, Gaballa M, Basnight MA. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressures using two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography in adult patients with cardiac disease. Additional value of analyzing left atrial size, left atrial ejection fraction and the difference in duration of pulmonary venous and mitral flow velocity at atrial contraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1972–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leung DY, Boyd A, Ng AA, Chi C, Thomas L. Echocardiographic evaluation of left atrial size and function: current understanding, pathophysiologic correlates, and prognostic implications. Am Heart J 2008;156:1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takemoto Y, Barnes ME, Seward JB, Lester SJ, Appleton CA, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Tsang TSM. Usefulness of left atrial volume in predicting first congestive heart failure in patients > or = 65 years of age with well-preserved left ventricular systolic function. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dzeshka MS, Lip GY, Snezhitskiy V, Shantsila E. Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:943–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allessie M, Ausma J, Schotten U. Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 2002;54:230–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pandey A, Kim S, Moore C, Thomas L, Gersh B, Allen LA, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Hylek E, Peterson ED, Piccini JP, Fonarow GC. Predictors and prognostic implications of incident heart failure in patients with prevalent atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Bohm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A, de Boer RA, Christian Schulze P, Abdelhamid M, Aboyans V, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Arbelo E, Asteggiano R, Bauersachs J, Bayes-Genis A, Borger MA, Budts W, Cikes M, Damman K, Delgado V, Dendale P, Dilaveris P, Drexel H, Ezekowitz J, Falk V, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Fraser A, Frey N, Gale CP, Gustafsson F, Harris J, Iung B, Janssens S, Jessup M, Konradi A, Kotecha D, Lambrinou E, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Leclercq C, Lewis BS, Leyva F, Linhart A, Løchen M-L, Lund LH, Mancini D, Masip J, Milicic D, Mueller C, Nef H, Nielsen J-C, Neubeck L, Noutsias M, Petersen SE, Sonia Petronio A, Ponikowski P, Prescott E, Rakisheva A, Richter DJ, Schlyakhto E, Seferovic P, Senni M, Sitges M, Sousa-Uva M, Tocchetti CG, Touyz RM, Tschoepe C, Waltenberger J, Adamo M, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gardner RS, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Piepoli MF, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Skibelund AK. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR, Fang JC, Fedson SE, Fonarow GC, Hayek SS, Hernandez AF, Khazanie P, Kittleson MM, Lee CS, Link MS, Milano CA, Nnacheta LC, Sandhu AT, Stevenson LW, Vardeny O, Vest AR, Yancy CW. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022;145:e895–e1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens L, Merkely B, Pokushalov E, Sanders P, Proff J, Schunkert H, Christ H, Vogt J, Bänsch D. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Potpara TS, Polovina MM, Licina MM, Mujovic NM, Marinkovic JM, Petrovic M, Vujisic-Tesic B, Lip GYH. The impact of dilated left atrium on rhythm control in patients with newly diagnosed persistent atrial fibrillation: the Belgrade atrial fibrillation project. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:1202–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.