Abstract

Hyperpolarization modalities overcome the sensitivity limitations of NMR and unlock new applications. Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange (SABRE) is a particularly cheap, quick and robust hyperpolarization modality. Here, we employ SABRE for simultaneous chemical exchange of parahydrogen and a nitrile containing anti-cancer drugs (letrozole or anastrozole) to enhance 15N polarization. Distinct substrates require unique optimal parameter sets, including temperature, magnetic field, and the magnetic field profile. The fine tuning of these parameters for individual substrates is demonstrated here to maximize 15N polarization. After optimization, including usage of pulsed μT fields, the 15N nuclei on common anti-cancer drugs, letrozole and anastrozole, can be polarized within 1–2 minutes. The hyperpolarization can exceed 10%, corresponding to 15N signal enhancement of over 280,000-fold at the clinically relevant magnetic field of 1 T. This sensitivity gain enables polarization studies at natural abundant 15N enrichment level (0.4%). Moreover, the nitrile 15N sites enable long-lasting polarization storage with [15N]T1 over 9 minutes enabling signal detection from a single hyperpolarization cycle for over 30 minutes.

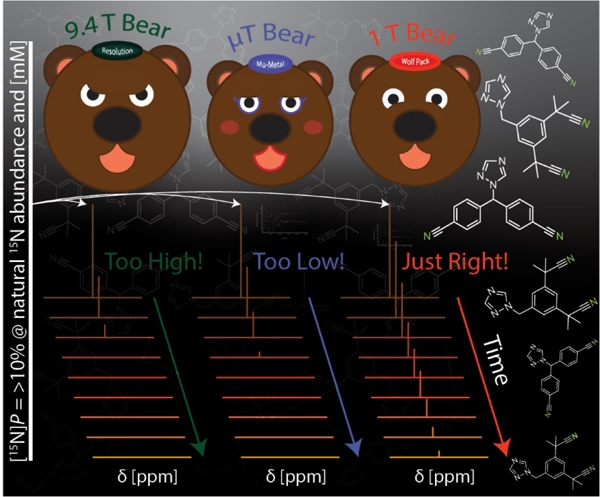

Graphical Abstract

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is a leading tool for qualifying, quantifying, and monitoring molecules and their dynamics. The advantage of this non-destructive technique stems from the inherent chemical shift resolution afforded by NMR, which offers functional and structural information. However, NMR has inherently low sensitivity compared to other spectroscopic methods. This is because of the minute thermal spin polarization (<10−5 at 3T for 15N), even at high magnetic fields. Hyperpolarization modalities increase the sensitivity of NMR by perturbing thermal spin polarization towards unity. Thus, the increase in signal afforded by hyperpolarization unlocks new doors for more sensitive applications using NMR.

Currently, the dominant hyperpolarization modality employed in tandem with NMR is Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP). 1–10 DNP generates high levels of hyperpolarization on a broad range of substrates, including water, and can directly hyperpolarize site specific locations on proteins. 11,12 However, in addition to being a lengthy process (on the order tens of minutes), instrumentation for DNP is expensive (>1M), requiring cryogenic temperatures, a superconducting magnet, and high powered microwave sources.13 In contrast, Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange (SABRE),14,15 a Para-Hydrogen Induced Polarization (PHIP) technique,16–18 can produce hyperpolarized (HP) substrates quickly (~1 minute or less) with little instrumentation cost (~$20k).

Nonetheless, SABRE often generates lower levels of hyperpolarization and has a more limited substrate scope compared to DNP. Thus, a significant effort has been made by the SABRE community to not only optimize the hyperpolarization process for distinct substrate groups but to expand the substrate scope to various biologically relevant molecules.19,20 Previous work has paved the way for SABRE methods to be employed as a tool for fast, simple and efficient sensitivity boosters that can readily pair with current analytical methods. For instance, in addition to pioneering ligand-protein studies with DNP, recently Hilty and colleagues demonstrated the utility of using SABRE for the determination of ligand-protein binding.21,22 In this work, ligands are first hyperpolarized in methanol. Then, the hyperpolarized solution is mixed with a protein solution at a Y-junction prior to entering an aqueous flow cell. Furthermore, work from Tessari and colleagues showed the feasibility of detecting amino acid and other metabolites in biological fluids (e.g., urine) using SABRE.23–25

SABRE utilizes a transition metal catalyst that simultaneously and reversibly binds parahydrogen (p-H2) and a target substrate. During the SABRE process, a temporary J-coupling network forms between the p-H2 derived hydrides and target nuclei on the substrate. The active SABRE complex and the corresponding J-coupling network is illustrated in Figure 1A. Spin order can be transferred to target nuclei through the J-coupling network by RF pulses26–30 or field cycling to low magnetic fields that approach level anti crossings (LACs).31–33 SABRE efficiency is controlled by exchange rates, J-couplings, and Larmor frequencies of the spin system. Therefore, distinct spin systems (different substrates) will have a unique optimal parameter set. Fine tuning these parameters for individual substrates is instrumental for efficient SABRE hyperpolarization with the primary key benchmark of level of attainable polarization, P (15N polarization is denoted as [15N]P in this document).

Figure 1.

[A] Illustration of parahydrogen and a drug reversibly binding to a transition metal complex forming a temporarily J-coupling network, and [B] the anti-cancer drugs, letrozole and anastrozole, with target 15N nuclei (at natural isotopic abundance) highlighted in orange.

A number of FDA-approved drugs have been HP via SABRE to date including: metronidazole34–36 ornidazole,37 nimorazole,38 pyrazinamide, isoniazid,39 clotrimazole, fluconazole, voriconazole40 and dalfampridine.41,42 These drugs target hypoxia, tuberculosis, fungal and bacterial infections, and multiple sclerosis. Moreover, they are HP via SABRE using five- or six-membered N-heterocyles rather than nitrile moiety studied in this work. Here, we utilize SABRE in Shield Enables Alignment Transfer to Heteronuclei (SABRE-SHEATH),43,44 and coherent SABRE-SEATH using pulsed μT fields, to extend the 15N heteronuclear scope to two bulky, nitrile45 containing anti-cancer drugs, letrozole and anastrozole, shown in Figure 1B. Both drugs are current generation aromatase inhibitors employed to combat breast cancer46 and are on the World Health Organizations Model List of Essential Medicine, making them highly attractive biological compounds. Heteronuclei, such as 15N, are attractive hyperpolarization targets because they have virtually no background signal and are associated with long T1 relaxation times.19,47 For a general overview mapping the progress of 15N hyperpolarization using SABRE, see the following review articles.20,48–50 Therefore, we envision the utility of these HP compounds to be used for more sensitive drug screening or as potential exogenous HP contrast agents. Moreover, because aromatase inhibitors (including letrozole and anastrazole studied here) are excreted via urine, we envision that these drugs and the products of their metabolism can potentially be detected in urine samples, paving the way to new applications in the context of cancer management.

Specifically, we perform hyperpolarization build-up and lifetime studies and then optimize the hyperpolarization process with respect to solution temperature and polarization transfer field (PTF), including pulsed μT-fields. At the optimum PTF, the hydride-substrate J-coupling is most efficient at transferring spin order from hydrides to substrates. The optimum PTF is dictated by a (Level Anti Crossing) LAC between hydride and substrate spin states. The LAC is established when the hydride-hydride J-coupling and the frequency difference between hydride and substrate spins are very close to each other. In the case of hydride-15N systems, like the one studied here, the optimal PTF is typically found at 0.3 µT.

The presented series of experimental optimization studies reaches high (>10%) and long lived ([15N]T1 over 9 mins) hyperpolarization on the anti-cancer drugs at natural isotopic abundance. This work not only broadens the scope of accessible substrates for SABRE-SHEATH, but also presents a methodical pathway for hyperpolarizing new SABRE substrates.

In this work, we focused on optimizing the hyperpolarization of chemically symmetric nitrile groups. Although 15N enhancements were observed on the triazole substituent (a triplet peak from the coordinating nitrogen) on both drugs, they were vastly overshadowed by the 15N enhancements observed on the nitrile substituents. In the present chemical system, the nitrile substituents hyperpolarize far more efficiently than the nitrogen containing heterocycles. First, we studied hyperpolarization build-up and the hyperpolarization lifetime (T1 constant) for the nitrile substituents on letrozole and anastrozole. We then optimized the hyperpolarization process with respect to solution temperature and PTF. Lastly, we applied a dynamic PTF, referred to as coherent SABRE-SHEATH,51 to yield maximum hyperpolarization. As the drugs were not isotopically enriched, polarization values were determined using a 15N enriched pyridine sample thermalized at 9.4 T (see SI for more advanced and complete details on [15N]P calculations) following a previously reported method.43

Hyperpolarization modalities are often associated with lengthy polarization build-up times that often bottleneck the hyperpolarization process.52 In SABRE, the polarization build-up time is relatively fast. Accordingly, we first conducted polarization build-up experiments on the nitrile substituents. Letrozole and anastrozole had similar build-up profiles, both reaching a steady state around 1 minute, with 15N Tb (build-up constant) of 21.7±1.4 seconds and 14.6±0.9 respectively, summarized in Table 1. The experimental build-up data was fit using a mono-exponential function and are shown together in Figure 2A. For experimental reproducibility, a bubbling time of 90 s was chosen for all succeeding experiments.

Table 1.

Hyperpolarization build-up and lifetime constants for 15N on the nitrile substituents of letrozole and anastrozole with errors given from the standard deviation of the individual mono-exponential fits.

| Anti-Cancer Drug | Build-up Constant, Tb [s] @ 0.3 μT | [15N]T1 [s] @ 9.4 T | [15N]T1 [s] @ 1 T | [15N]T1 [s] @ 0.3 μT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letrozole | 21.7 ± 1.4 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | 554.1 ± 12.7 | 34.7 ± 3.0 |

| Anastrozole | 14.6 ± 0.9 | 21.6 ± 0.2 | 420.8 ± 7.3 | 27.8 ± 2.9 |

Figure 2.

Optimization studies for the nitrile substituents nitrogen on letrozole and anastrozole. [A] Experimental polarization build-up data recorded at 40°C overlaid with mono-exponential fits. [B] Experimental [15N]T1 data, recorded at 40°C and stored at 1 T, overlaid with mono-exponential fits. [C] Temperature sweep from 25°C to 50°C with 5°C increments. The polarization is listed on the left axis while the molar polarization (the product of polarization and spin density) is listed on the right. Experiments were done at natural isotopic abundance (15N is ~0.4% naturally abundant) using a substrate concentration of 30 mM (see the methods section for more details on sample composition). [D] A static field sweep from 0 to 3.6 μT with 0.3 μT increments with PTFs both parallel (+) and antiparallel (−) to the detection field.

Long lifetimes of HP states are important for monitoring biological (in vivo) and biochemical processes (in vitro: e.g., protein and drug-protein studies) that have slower or downstream interactions of interest. Previous studies demonstrated that [15N]T1 constants can be extended by storage at an appropriate field.19,40,53 Often, using a storage field at an intermediate strength (relative to traditional PTFs and detection fields), around 1 T, can significantly extended [15N]T1 times, while noting that the relaxation properties and their field dependencies vary widely depending on the individual molecules and associated spin systems. Thus, in addition to hyperpolarization build-up times, we elucidate hyperpolarization lifetimes at three different fields. Hyperpolarization lifetime studies were investigated at high field (9.4 T), low field (0.3 μT) and an intermediate field (1 T).

Agreeing with trends characterized in literature, short lifetimes are observed at low and high fields, while longer lifetimes are observed at intermediate fields.19,40,53 At high field, the [15N]T1 for letrozole and anastrozole was measured to be 9.3±0.1 s and 21.6±0.2 s respectively, as reported in Table 1. These values are slightly lower than the [15N]T1 values at low field for both letrozole and anastrozole, which were measured to be 34.7±3.0 s and 27.8±2.9 s, respectively. Figure 2B shows the remarkably long 15N HP lifetime data recorded at 1 T overlaid with mono-exponential fits yielding [15N]T1 of 554.1±12.7 s (>9 minutes) and 420.8±7.3 s (>7 minutes) for letrozole and anastrozole, respectively.

Relaxation at high field is likely dominated chemical shift anisotropy (CSA), which scales quadratically with magnetic field. CSA is mitigated at low fields, which can explain why we observe longer [15N]T1’s when transitioning to a low storage field. However, other sources of relaxation become dominant at low field strengths. Specifically, when the system is not replenished with fresh p-H2 at 0.3 μT, spin mixing during binding events at low fields leads to relaxation (i.e. the hyperpolarization mechanism is reverted and the hydrides may act as a polarization sink). Evidence supporting this claim is found when comparing the [15N]T1 of letrozole and anastrozole at low field. The suspected faster exchanging substrate (experiencing more binding events), anastrozole, has a shorter [15N]T1 than the slower exchanging substrate (experiencing fewer binding events), letrozole.

At an intermediate field of 1 T, both CSA and spin mixing are mitigated. Instead, dipolar interactions between nuclei become the dominant sources of relaxation19, which are weak for the isolated 15N spin in nitriles. Nitrogen on a nitrile lacks nearby spin ½ nuclei that could induce strong dipolar relaxation. Thus, mitigating high and low field relaxation sources and selecting an isolated target nucleus gives rise to an exceptional environment for magnetization storage. Other methods used to extend T1’s have been shown in literature, for example isotopic labelling where protons are replaced for deuterium,47 or the usage of long-lived singlet states.54

In addition to relaxation parameters, another critical parameter in SABRE are the exchange rates on the SABRE complex. The chemical exchange of p-H2 and a target substrate need to be similar to the frequency of spin order transfer, governed by the temporary J-coupling network on the active SABRE catalyst, for efficient spin transfer.

There are several methods reported in literature that have been used to control the exchange of both p-H2 and a target substrate. These methods consist of either increasing or decreasing the electronic density on the metal centre or by increasing or decreasing the steric crowding around the metal centre.55,56 These strategies not only allow for more efficient spin order transfer, but also enable the hyperpolarization of new substrates. Work led by Duckett and colleagues demonstrated that SABRE can be used to hyperpolarize α-keto acids and nitrites by modulating exchange with the incorporation of a co-substrate.57,58 In addition to the referenced strategies, direct heating or cooling can be used to modulate exchange rates.40,59 Following these findings, a temperature sweep was performed on both target drugs. We chose to sweep from room temperature (25 °C) to 50 °C with 5 °C increments, shown in Figure 2C, to shed light on the exchange dynamics.

Prominently, we observed an increase in polarization as temperature was increased. Letrozole reaches maximum hyperpolarization at 50 °C (limited by experimental setup), while anastrozole reaches a maximum at 40 °C, but levels off at further elevated temperatures. The difference in observed maxima is likely due to the chemical environment around the nitrile substituents on both drugs. Anastrozole has additional steric bulk close to the nitrile substituent compared to letrozole, likely leading to faster exchange. Therefore, the faster exchanging substrate, anastrozole, will be expected to reach maximum hyperpolarization at lower temperatures relative to the faster exchanging substrate, letrozole. We note that the substrate exchange rate also controls the hydride exchange rate, as we have shown with ab initio calculations,60 because hydride exchange does require substrate exchange events for monodentate ligands. These findings not only support that temperature modulation represents a key hyperpolarization parameter, but additionally suggests that relative exchange rates can be unveiled through HP temperature studies.

In traditional SABRE-SHEATH experiments, the sample is subjected to a very low (<1 μT) static PTF. At sub µT fields, LACs between coupled spin states arise. At a LAC, spin mixing is most efficient, aiding in polarization build-up.31,43 For this reason, we investigated the μT regime to unveil the most efficient PTF. We swept from 0 to 3 μT with 0.3 μT increments with static PTFs aligned parallel (+) and antiparallel (−) to the detection field, as shown in Figure 2D. Hyperpolarization was most efficiently generated at ±0.3 μT for both drugs.

However, recent advances reported in literature demonstrate that a static field only generates a fraction of the hyperpolarization of a dynamic pulse (field). 61–64 The referenced work has shown significant boosts in hyperpolarization by applying shaped PTF to the sample during polarization build-up in a variety of distinct patterns.61–64 On this notion, we implemented a previously published pulse sequence referred to as coherent SABRE-SHEATH, originally used by Lindale et al. to increase hyperpolarization on acetonitrile (chemically similar to the nitrile substituents on letrozole and anastrozole).51

Coherent SABRE-SHEATH first evolves spin order using an efficient PTF, BP, for a short time, τP, and then quickly switches to an elevated storage field, BS, where little to no evolution is expected, for a lengthier duration, τS, that is pre-optimized (see SI for τS optimization) to allow fresh p-H2 to associate with the catalyst. A graphical representation of the pulse sequence is shown in Figure 3A. A plot sweeping through discrete τP values, while BP, BS, and τP remain constant, is shown in Figure 3C for both letrozole and anastrozole.

Figure 3.

[A] Graphical representation of coherent SABRE-SHEATH pulse sequence, [B] NMR signal of anastrozole when τP = 51 ms, and [C] applying coherent SABRE-SHEATH pulse sequence sweeping from τp = 0 to τp = 250 ms while keeping BP, BS, and τP constant (BP = 0.5 μT, BS = 30 μT and τS = 200 ms).

Notably, the pulse sequence drives higher polarization than what can be generated using a static field. Both compounds reach maximum enhancements when τP = 51 ms. For anastrozole, the maximum enhancement corresponds to [15N]P over 10% (at natural isotopic abundance and mM concentration) and the corresponding spectrum is shown in Figure 3B. The boost in [15N]P is due to more efficient spin order transfer generated by turning the usually incoherent spin order transfer into a coherently driven, unidirectional mechanism. In addition to boosting the hyperpolarization level, the coherent SABRE-SHEATH data of Figure 3B also elucidates the hyperpolarization transfer dynamics.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates a systematic optimization study for nitrile moieties of two bulky anti-cancer drugs achieving high degrees of [15N]P with long HP state lifetimes.

First, the polarization build-up was investigated for both letrozole and anastrozole. Both anti-cancer drugs had similar build-up constants, reaching a [15N]P steady state in ~1 minute. For comparison, DNP has a build-up time on the order of tens of minutes to an hour.13 Additionally, by exploring a clinically relevant field of 1 T, we were able to achieve [15N]T1 constants of ~9 minutes and ~7 minutes on letrozole and anastrozole, respectively. Next, we explored exchange dynamics of the SABRE system by modulating the solution temperature and swept through the μT regime to elucidate the optimal PTF. Maximum enhancements were measured at 50 °C for letrozole and 40 °C for anastrozole, corresponding to [15N]P of 8.3% and 7.6%, respectively, at the experimental optimal PTF of 0.3 μT. We also showed that controlling the solution temperature, in a small window (25 °C), can more than double the net [15N]P. Finally, we pushed the hyperpolarization to over 10% on anastrozole (at natural isotopic abundance and mM concentration), by applying coherent SABRE-SHEATH, showing the importance of exploring non-static fields.

The feasibility of studying SABRE hyperpolarization at natural abundance of 15N substantially streamlines the experimental workflow and potentially enables screening of many other nitrile-containing drugs, biomolecules, etc. This work lays a foundation for more sensitive drug screening and trace analysis using high-resolution NMR spectroscopy.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals:

Letrozole and anastrozole were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., LTD, and Sigma Aldrich, respectively, and used as delivered. Deuterated methanol was purchased through Cambridge Isotope Laboratories and degassed prior to experimental use. The pre catalyst, [Ir(IMes)(COD)Cl] (IMes = 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene, COD = 1,5-cyclooctadiene), was synthesized in lab with commercially available starting materials following a previously published procedure.65

Sample Preparation:

All samples are prepared using standard Schlenk line conditions, maintaining an oxygen free environment. Samples are prepared with 30 mM substrate (letrozole or anastrozole) and 3 mM pre-catalyst in 500 μL deuterated methanol. Samples are then transferred into a 7” medium wall NMR tube (Wilmad 524-PV-7) and connected to our in-house, fully automated, pneumatic shuttling system.66 Samples are then subjected to 100 psi of parahydrogen and allowed to activate, by bubbling, for 5 minutes prior to experimentation.

Hyperpolarization Build-up:

Samples are first shuttled above the detection field to a polarization transfer field (PTF = 0.3 μT) and are then subjected to bubbling for a distinct time before shuttling back down to high field (9.4 T) for detection.

Hyperpolarization Lifetime:

Samples are first shuttled above the detection field to a polarization transfer field (PTF = 0.3 μT) and were then subjected to 90 s of bubbling. Samples are then stored at a desired field for various times before detection. The PTF and detection field are used as low and high storage fields, respectively, while the fringe field from the detection field is used as an intermediate storage field (~1 T).

Temperature Dependence:

Samples are first heated to a desired temperature in the detection field using the Bruker VT interface. Samples are then shuttled to a PTF (0.3 μT) and are subjected to 90 s of bubbling. Samples are not actively heated while bubbling, thus the sample experiences light cooling towards room temperature during bubbling. Samples are then shuttled down to high field for detection.

Static Field Dependence:

Samples are shuttled to a desired PTF controlled by a DC power supply and house-built solenoid coil inside mu-metal shields. Samples are then subjected to 90 s of bubbling within the PTF and shuttled down to high field for detection.

Coherent SHEATH:

Samples are shuttled to a dynamic PTF controlled by a DC power supply and home-built solenoid coil inside mu-metal shields. The dynamic PTF alternates between two distinct fields, an “evolution field”, denoted Bp, and a “storage field”, denoted Bs, for different durations, τp and τs, respectively, n times for 90 seconds. The dynamic PTF is generated using a simple circuit board, TTL lines, and solid-state relays. In this method, a pulse sequence can be developed using Bruker software to automate the process. Largest signal enhancements were observed at Bp = 0.5 μT while maintaining a Bs of ~30 μT, which was the highest achievable field in our experimental design.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award Nos. NIH R21EB025313 and NIH R01EB029829. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, we acknowledge funding from the Mallinckrodt Foundation, the National Science Foundation under Award No. NSF CHE-1904780, from the National Cancer Institute under Award No. NCI 1R21CA220137, and from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center in the form of a Translational Research Grant. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the support from NCSU’s METRIC providing access to NMR instrumentation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Thomas Theis and Patrick TomHon holds stock in Vizma Life Sciences LLC (VLS) and is President of VLS. VLS is developing products related to the research being reported. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by NC State University in accordance with its policy on objectivity in research. Eduard Y. Chekmenev discloses a stake of ownership in XeUS Technologies, LTD

REFERENCES

- (1).Chappuis Q; Milani J; Vuichoud B; Bornet A; Gossert AD; Bodenhausen G; Jannin S Hyperpolarized Water to Study Protein-Ligand Interactions. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2015, 6 (9), 1674–1678. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang Y; Hilty C Amplification of Nuclear Overhauser Effect Signals by Hyperpolarization for Screening of Ligand Binding to Immobilized Target Proteins. Anal Chem 2020, 92 (20), 13718–13723. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Min H; Sekar G; Hilty C Polarization Transfer from Ligands Hyperpolarized by Dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization for Screening in Drug Discovery. ChemMedChem 2015, 10 (9), 1559–1563. 10.1002/cmdc.201500241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kim Y; Hilty C Applications of Dissolution-DNP for NMR Screening. Methods Enzymol 2019, 615, 501–526. 10.1016/BS.MIE.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Keshari KR; Kurhanewicz J; MacDonald JM; Wilson DM Generating Contrast in Hyperpolarized 13C MRI Using Ligand-Receptor Interactions. Analyst 2012, 137 (15), 3427–3429. 10.1039/c2an35406c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kress T; Walrant A; Bodenhausen G; Kurzbach D Long-Lived States in Hyperpolarized Deuterated Methyl Groups Reveal Weak Binding of Small Molecules to Proteins. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2019, 10 (7), 1523–1529. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Buratto R; Bornet A; Milani J; Mammoli D; Vuichoud B; Salvi N; Singh M; Laguerre A; Passemard S; Gerber-Lemaire S; Jannin S; Bodenhausen G Drug Screening Boosted by Hyperpolarized Long-Lived States in NMR. ChemMedChem 2014, 9 (11), 2509–2515. 10.1002/cmdc.201402214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hu J; Kim J; Hilty C Detection of Protein−Ligand Interactions by 19F Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Using Hyperpolarized Water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2022, 13, 4. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kim Y; Liu M; Hilty C Parallelized Ligand Screening Using Dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Anal Chem 2016, 88 (22), 11178–11183. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wang Y; Kim J; Hilty C Determination of Protein-Ligand Binding Modes Using Fast Multi-Dimensional NMR with Hyperpolarization. Chem Sci 2020, 11 (23), 5935–5943. 10.1039/d0sc00266f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gauto D; Dakhlaoui O; Marin-Montesinos I; Hediger S; De Paëpe G Targeted DNP for Biomolecular Solid-State NMR. Chemical Science. 2021, pp 6223–6237. 10.1039/d0sc06959k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hilty C; Kurzbach D; Frydman L Hyperpolarized Water as Universal Sensitivity Booster in Biomolecular NMR. Nat Protoc 2022, 17 (7), 1621–1657. 10.1038/s41596-022-00693-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Pinon AC; Capozzi A; Ardenkjær-Larsen JH Hyperpolarization via Dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization: New Technological and Methodological Advances. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine. 2021, pp 5–23. 10.1007/s10334-020-00894-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Adams RW; Duckett SB; Green RA; Williamson DC; Green GGR A Theoretical Basis for Spontaneous Polarization Transfer in Non-Hydrogenative Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization. Journal of Chemical Physics 2009, 131 (19). 10.1063/1.3254386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Adams RW; Aguilar JA; Atkinson KD; Cowley MJ; Elliott PIP; Duckett SB; Green GGR; Khazal IG; Lopez-Serrano J; Williamson DC Reversible Interactions with Para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science (1979) 2009, 323 (5922), 1708–1711. 10.1126/science.1168877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bowers CR; Weitekamp DP Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical Reaction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Phys Rev Lett 1986, 57 (21), 2645–2648. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bowers CR; Weitekamp DP Parahydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J Am Chem Soc 1987, 109 (18), 5541–5542. 10.1021/ja00252a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Eisenschmid TC; Kirss RU; Deutsch PP; Hommeltoft SI; Eisenberg R; York N; Lawler RG; Balch AL Para Hydrogen Induced Polarization in Hydrogenation Reactions. Americcan chemical society 1987, 109 (26), 8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Colell JFP; Logan AWJ; Zhou Z; Shchepin R. v.; Barskiy DA; Ortiz GX; Wang Q; Malcolmson SJ; Chekmenev EY; Warren WS; Theis T Generalizing, Extending, and Maximizing Nitrogen-15 Hyperpolarization Induced by Parahydrogen in Reversible Exchange. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121 (12), 6626–6634. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Barskiy DA; Knecht S; Yurkovskaya A v.; Ivanov, K. L. SABRE: Chemical Kinetics and Spin Dynamics of the Formation of Hyperpolarization. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 2019, 114–115, 33–70. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mandal R; Pham P; Hilty C Characterization of Protein-Ligand Interactions by SABRE. Chem Sci 2021, 12 (39), 12950–12958. 10.1039/d1sc03404a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Mandal R; Pham P; Hilty C Screening of Protein-Ligand Binding Using a SABRE Hyperpolarized Reporter. Anal Chem 2022, 94 (32), 11375–11381. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c02250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Reile I; Eshuis N; Hermkens NKJ; Van Weerdenburg BJA; Feiters MC; Rutjes FPJT; Tessari M NMR Detection in Biofluid Extracts at Sub-ΜM Concentrations: Via Para -H2 Induced Hyperpolarization. Analyst 2016, 141 (13), 4001–4005. 10.1039/c6an00804f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sellies L; Aspers RLEG; Feiters MC; Rutjes FPJT; Tessari M Parahydrogen Hyperpolarization Allows Direct NMR Detection of α-Amino Acids in Complex (Bio)Mixtures. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2021, 60 (52), 26954–26959. 10.1002/anie.202109588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fraser R; Rutjes FPJT; Feiters MC; Tessari M Analysis of Complex Mixtures by Chemosensing NMR Using Para-Hydrogen-Induced Hyperpolarization. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55 (13), 1832–1844. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Roy SS; Stevanato G; Rayner PJ; Duckett SB Direct Enhancement of Nitrogen-15 Targets at High-Field by Fast ADAPT-SABRE. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2017, 285, 55–60. 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Theis T; Truong M; Coffey AM; Chekmenev EY; Warren WS LIGHT-SABRE Enables Efficient in-Magnet Catalytic Hyperpolarization. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2014, 248, 23–26. 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lindale JR; Eriksson SL; Warren WS Phase Coherent Excitation of SABRE Permits Simultaneous Hyperpolarization of Multiple Targets at High Magnetic Field. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2022, 24 (12), 7214–7223. 10.1039/d1cp05962a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Theis T; Feng Y; Wu T; Warren WS Composite and Shaped Pulses for Efficient and Robust Pumping of Disconnected Eigenstates in Magnetic Resonance. Journal of Chemical Physics 2014, 140 (1). 10.1063/1.4851337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Pravdivtsev AN; Yurkovskaya AV; Vieth HM; Ivanov KL Spin Mixing at Level Anti-Crossings in the Rotating Frame Makes High-Field SABRE Feasible. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2014, 16 (45), 24672–24675. 10.1039/c4cp03765k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ivanov KL; Yurkovskaya AV; Vieth HM Coherent Transfer of Hyperpolarization in Coupled Spin Systems at Variable Magnetic Field. Journal of Chemical Physics 2008, 128 (15). 10.1063/1.2901019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Pravdivtsev AN; Yurkovskaya AV; Kaptein R; Miesel K; Vieth HM; Ivanov KL Exploiting Level Anti-Crossings for Efficient and Selective Transfer of Hyperpolarization in Coupled Nuclear Spin Systems. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15 (35), 14660–14669. 10.1039/c3cp52026a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pravdivtsev AN; Yurkovskaya AV; Vieth HM; Ivanov KL; Kaptein R Level Anti-Crossings Are a Key Factor for Understanding Para-Hydrogen-Induced Hyperpolarization in SABRE Experiments. ChemPhysChem 2013, 14 (14), 3327–3331. 10.1002/cphc.201300595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kiryutin AS; Yurkovskaya AV; Ivanov KL 15N SABRE Hyperpolarization of Metronidazole at Natural Isotope Abundance. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22 (14), 1470–1477. 10.1002/cphc.202100315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Barskiy DA; Shchepin RV; Coffey AM; Theis T; Warren WS; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY Over 20% 15N Hyperpolarization in under One Minute for Metronidazole, an Antibiotic and Hypoxia Probe. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138 (26), 8080–8083. 10.1021/jacs.6b04784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Shchepin RV; Birchall JR; Chukanov NV; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Theis T; Warren WS; Gelovani JG; Goodson BM; Shokouhi S; Rosen MS; Yen YF; Pham W; Chekmenev EY Hyperpolarizing Concentrated Metronidazole 15NO2 Group over Six Chemical Bonds with More than 15 % Polarization and a 20 Minute Lifetime. Chemistry - A European Journal 2019, 25 (37), 8829–8836. 10.1002/chem.201901192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Iali W; Moustafa GAI; Dagys L; Roy SS 15N Hyperpolarisation of the Antiprotozoal Drug Ornidazole by Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange in Aqueous Medium. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2021, 59 (12), 1199–1207. 10.1002/mrc.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Salnikov OG; Chukanov NV; Svyatova A; Trofimov IA; Kabir MSH; Gelovani JG; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY. 15N NMR Hyperpolarization of Radiosensitizing Antibiotic Nimorazole by Reversible Parahydrogen Exchange in Microtesla Magnetic Fields. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2021, 60 (5), 2406–2413. 10.1002/anie.202011698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zeng H; Xu J; Gillen J; McMahon MT; Artemov D; Tyburn JM; Lohman JAB; Mewis RE; Atkinson KD; Green GGR; Duckett SB; Van Zijl PCM Optimization of SABRE for Polarization of the Tuberculosis Drugs Pyrazinamide and Isoniazid. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2013, 237, 73–78. 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).MacCulloch K; Tomhon P; Browning A; Akeroyd E; Lehmkuhl S; Chekmenev EY; Theis T Hyperpolarization of Common Antifungal Agents with SABRE. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2021, 59 (12), 1225–1235. 10.1002/mrc.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Skovpin IV; Svyatova A; Chukanov N; Chekmenev EY; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV 15N Hyperpolarization of Dalfampridine at Natural Abundance for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Chemistry - A European Journal 2019, 25 (55), 12694–12697. 10.1002/chem.201902724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chukanov NV; Salnikov OG; Trofimov IA; Kabir MSH; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY. Synthesis and 15N NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange of [15N]Dalfampridine at Microtesla Magnetic Fields. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22 (10), 960–967. 10.1002/cphc.202100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Theis T; Truong ML; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Waddell KW; Shi F; Goodson BM; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY Microtesla SABRE Enables 10% Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Spin Polarization. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137 (4), 1404–1407. 10.1021/ja512242d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Truong ML; Theis T; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Waddell KW; Shi F; Goodson BM; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY 15N Hyperpolarization by Reversible Exchange Using SABRE-SHEATH. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119 (16), 8786–8797. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Mewis RE; Green RA; Cockett MCR; Cowley MJ; Duckett SB; Green GGR; John RO; Rayner PJ; Williamson DC Strategies for the Hyperpolarization of Acetonitrile and Related Ligands by SABRE. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2015, 119 (4), 1416–1424. 10.1021/jp511492q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Buzdar AU; Robertson JFR; Eiermann W; Nabholtz JM An Overview of the Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics of the Newer Generation Aromatase Inhibitors Anastrozole, Letrozole, and Exemestane. Cancer 2002, 95 (9), 2006–2016. 10.1002/cncr.10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Nonaka H; Hirano M; Imakura Y; Takakusagi Y; Ichikawa K; Sando S Design of a 15 N Molecular Unit to Achieve Long Retention of Hyperpolarized Spin State. Sci Rep 2017, 7 (40104), 1–6. 10.1038/srep40104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Hövener J; Pravdivtsev AN; Kidd B; Bowers CR; Glöggler S; Kovtunov K. v.; Plaumann M; Katz‐Brull R; Buckenmaier K; Jerschow A; Reineri F; Theis T; Shchepin R. v.; Wagner S; Bhattacharya P; Zacharias NM; Chekmenev EY Parahydrogen-Based Hyperpolarization for Biomedicine. Angewandte Chemie 2018, 130 (35), 11310–11333. 10.1002/ange.201711842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Park H; Wang Q State-of-the-Art Accounts of Hyperpolarized 15N-Labeled Molecular Imaging Probes for Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Imaging. Chemical Science. Royal Society of Chemistry May 17, 2022, pp 7378–7391. 10.1039/d2sc01264b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Rayner PJ; Duckett SB Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange (SABRE): From Discovery to Diagnosis. Angewandte Chemie 2018, 130 (23), 6854–6866. 10.1002/ange.201710406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lindale JR; Eriksson SL; Tanner CPN; Zhou Z; Colell JFP; Zhang G; Bae J; Chekmenev EY; Theis T; Warren WS Unveiling Coherently Driven Hyperpolarization Dynamics in Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. Nat Commun 2019, 10 (395). 10.1038/s41467-019-08298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Nikolaou P; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques for Biomedicine. Chem. Eur. J 2015, 21, 3156–3166. 10.1002/chem.201405253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Kiryutin AS; Yurkovskaya AV; Ivanov KL. 15N SABRE Hyperpolarization of Metronidazole at Natural Isotope Abundance. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22 (14), 1470–1477. 10.1002/cphc.202100315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Theis T; Ortiz GX; Logan AWJ; Claytor KE; Feng Y; Huhn WP; Blum V; Malcolmson SJ; Chekmenev EY; Wang Q; Warren WS Direct and Cost-Efficient Hyperpolarization of Long-Lived Nuclear Spin States on Universal 15N2-Diazirine Molecular Tags. Sci Adv 2016, 2 (3), 1–8. 10.1126/sciadv.1501438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fekete M; Ahwal F; Duckett SB Remarkable Levels of 15N Polarization Delivered through SABRE into Unlabeled Pyridine, Pyrazine, or Metronidazole Enable Single Scan NMR Quantification at the MM Level. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2020, 124 (22), 4573–4580. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c02583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Colell JFP; Logan AWJ; Zhou Z; Lindale JR; Laasner R; Shchepin RV; Chekmenev EY; Blum V; Warren WS; Malcolmson SJ; Theis T Rational Ligand Choice Extends the SABRE Substrate Scope. Chemical Communications 2020, 56 (65), 9336–9339. 10.1039/d0cc01330g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tickner BJ; Semenova O; Iali W; Rayner PJ; Whitwood AC; Duckett SB Optimisation of Pyruvate Hyperpolarisation Using SABRE by Tuning the Active Magnetisation Transfer Catalyst. Catal Sci Technol 2020, 10 (5), 1343–1355. 10.1039/c9cy02498k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Rayner PJ; Fekete M; Gater CA; Ahwal F; Turner N; Kennerley AJ; Duckett SB Real-Time High-Sensitivity Reaction Monitoring of Important Nitrogen-Cycle Synthons by 15N Hyperpolarized Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144, 8756–8769. 10.1021/jacs.2c02619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Tomhon P; Abdulmojeed M; Adelabu I; Nantogma S; Kabir MSH; Lehmkuhl S; Chekmenev EY; Theis T Temperature Cycling Enables Efficient 13C SABRE-SHEATH Hyperpolarization and Imaging of [1–13C]-Pyruvate. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144 (1), 282–287. 10.1021/jacs.1c09581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lin K; TomHon P; Lehmkuhl S; Laasner R; Theis T; Blum V Density Functional Theory Study of Reaction Equilibria in Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22 (19), 1947–1957. 10.1002/cphc.202100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Pravdivtsev AN; Kempf N; Plaumann M; Bernarding J; Scheffler K; Hövener JB; Buckenmaier K Coherent Evolution of Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange in Two Alternating Fields (Alt-SABRE). ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 2381–2386. 10.1002/cphc.202100543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Dagys L; Bengs C; Levitt MH Low-Frequency Excitation of Singlet-Triplet Transitions. Application to Nuclear Hyperpolarization. Journal of Chemical Physics 2021, 155 (154201). 10.1063/5.0065863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Li X; Lindale JR; Eriksson SL; Warren WS SABRE Enhancement with Oscillating Pulse Sequences. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2022, 24, 16462–16470. 10.1039/d2cp00899h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Eriksson SL; Lindale JR; Li X; Warren WS Improving SABRE Hyperpolarization with Highly Nonintuitive Pulse Sequences: Moving beyond Avoided Crossings to Describe Dynamics. Sci Adv 2022, 8. 10.1126/sciadv.abl3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Vázquez-Serrano LD; Owens BT; Buriak JM Catalytic Olefin Hydrogenation Using N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Phosphine Complexes of Iridium. Chemical Communications 2002, 21 (765), 2518–2519. 10.1039/b208403a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (66).TomHon P; Akeroyd E; Lehmkuhl S; Chekmenev EY; Theis T Automated Pneumatic Shuttle for Magnetic Field Cycling and Parahydrogen Hyperpolarized Multidimensional NMR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2020, 312, 106700. 10.1016/j.jmr.2020.106700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.