Abstract

Regulation of mRNA translation by eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) is crucial for cell survival. In humans, eIF3 stimulates translation of the JUN mRNA which encodes the transcription factor JUN, an oncogenic transcription factor involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. Previous studies revealed that eIF3 activates translation of the JUN mRNA by interacting with a stem loop in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) and with the 5′ -7-methylguanosine cap structure. In addition to its interaction site with eIF3, the JUN 5′ UTR is nearly one kilobase in length, and has a high degree of secondary structure, high GC content, and an upstream start codon (uAUG). This motivated us to explore the complexity of JUN mRNA translation regulation in human cells. Here we find that JUN translation is regulated in a sequence and structure-dependent manner in regions adjacent to the eIF3-interacting site in the JUN 5′ UTR. Furthermore, we identify contributions of an additional initiation factor, eIF4A, in JUN regulation. We show that enhancing the interaction of eIF4A with JUN by using the compound Rocaglamide A (RocA) represses JUN translation. We also find that both the upstream AUG (uAUG) and the main AUG (mAUG) contribute to JUN translation and that they are conserved throughout vertebrates. Our results reveal additional layers of regulation for JUN translation and show the potential of JUN as a model transcript for understanding multiple interacting modes of translation regulation.

Introduction

Protein translation is one of the most energetically expensive cellular processes and is highly regulated, especially during translation initiation [1–5]. Translation initiation is a complex process which regulates expression of eukaryotic genes and employs over a dozen eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIFs) [6–9]. These include eIF1, eIF1A, eIF3, eIF5, eIF2 and the eIF4F complex, which is composed of eIF4E, eIF4A and eIF4G [7, 9]. During eukaryotic translation initiation, a ternary complex made up of initiator methionyl-tRNA (Met-tRNAi), eIF2, and GTP is formed [10, 11]. The 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC) then comes together by recruitment of the ternary complex, the 40S ribosomal subunit, and eukaryotic initiation factors 1, 1A, 3 and 5 [12–16]. After adopting an open conformation, the 43S PIC joins eIF4F at the mRNA 5′ cap in order to recruit the mRNA to form the 48S PIC [11]. This newly formed 48S PIC is then capable of scanning the mRNA through its 5′ untranslated region (5’ UTR) until it locates a start codon [17]. Once the start codon is recognized, several initiation factors are released in order for the ribosome to begin elongation [9, 11]. During initiation, the roles of several eIFs have been linked to translation regulation of subsets of mRNAs. For example, experiments performed in human cells revealed that eIF3 regulates the translation of specific mRNAs by direct interactions [18–20]. These eIF3-mRNA interactions are important for homeostasis but also play essential roles upon nutrient deprivation and drive the integrated stress response, among other functions [18–30]. eIF4A, an RNA helicase, has also been associated with translation regulation of a subset of mRNAs in human cells, more specifically by unwinding 5′ UTRs that are highly structured and polypurine rich and many of which are related to cell-cycle progression and apoptosis [31–34]. Moreover, eIF1 and eIF5 play important roles in the selection of translational start sites, depending not only on the AUG translational context, but also on the abundance of these initiation factors and specific cellular conditions [35–41].

Translation initiation factor eIF3 is a crucial player in protein expression regulation through its roles in bridging the 43S PIC and eIF4F complexes, and also by performing specialized regulatory roles [15, 42, 43]. eIF3 specifically binds to and regulates translation of a subset of mRNAs, many of which are involved in cell cycle regulation, cell growth, differentiation, and other crucial cellular functions. The interaction between eIF3 and mRNAs was shown to be mediated by RNA structural elements in the 5′ UTR of specific mRNAs in human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells and to cause translational activation or repression of these mRNAs [18]. eIF3 has also been shown to have cell-specific regulatory roles in T cells, with eIF3 interactions throughout the entire length of the transcript for specific mRNAs, such as the ones encoding the T cell receptor alpha and beta subunits (TCRA and TCRB, respectively), mediating a translational burst essential for T cell activation [20]. In yeast, eIF3 has also been linked to mRNA recruitment and scanning as a mediator of mRNA-PIC interactions [44–46]. Furthermore, in zebrafish eIF3 subunit H (EIF3H) was shown to regulate translation of mRNAs encoding the eye lens protein crystallin during embryogenesis [47]. These examples demonstrate that eIF3 plays a variety of mRNA-specific regulatory roles.

One of the reported eIF3-target mRNAs in human cells, JUN, encodes the transcription factor JUN, also known as c-Jun, which regulates gene expression in response to different stimuli [48, 49]. As a component of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) complex, JUN regulates transcription of a large number of genes and acts mainly as a transcriptional activator [50]. JUN is therefore highly involved in various cellular processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, tumorigenesis, and it was the first oncogenic transcription factor discovered [49, 51, 52]. Regulation of JUN expression is particularly important because its downregulation can lead to cell cycle defects and its upregulation can lead to accelerated cell proliferation, which occurs in some cancers [53]. Therefore, it is not surprising for JUN expression regulation to be complex and to occur at both the transcriptional and translational levels. At the transcriptional level, JUN mRNA expression is regulated by its own protein product, which binds a high-affinity AP-1 binding site in the JUN promoter region and in turn induces its transcription [54–56]. JUN expression regulation at the translational level is mediated by its mRNA interaction with eIF3. Binding of eIF3 subunits EIF3A, EIF3B, EIF3D, and EIF3G to a stem loop in the JUN 5′ UTR results in activation of translation [18]. Moreover, eIF3 subunit D (EIF3D) acts as a 5’ cap-binding protein on the JUN mRNA, mediated by a cis-acting RNA element located in the 153 nucleotides immediately downstream of the JUN 5′-7-methylguanosine cap structure [19]. This RNA element is also thought to block recruitment of the eIF4F complex [19]. JUN expression regulation at the translational level has also been shown to be affected by m6A methylation by METTL3 in its 3′ UTR and by contributions of an RNA structural element which activates its translation in glioblastoma [53, 57].

JUN possesses a longer than average 977-nucleotide 5′ UTR that is highly GC rich. Due to its length and complexity, JUN’s 5′ UTR might present additional layers of translational regulation of its mRNA through novel structural and/or sequence elements. Previously reported involvement of several initiation factors, including eIF3 and eIF4A, in the recruitment of mRNAs with long and structurally complex 5′ UTRs further supports a 5′ UTR-mediated mechanism for JUN translation regulation and suggests that additional factors may be involved in JUN regulation [58]. For example, JUN was recently shown to be sensitive to RocA, an anti-cancer drug that clamps eIF4A onto specific polypurine sequences in the 5′ UTRs of a subset of mRNAs [33, 34]. However, the implications of this interaction on JUN translation have not been previously evaluated. JUN also possesses two potential translational start sites, an upstream start codon (uAUG) located 4 codons upstream of the main start codon (mAUG). However, translational start site selection for the JUN mRNA has not been previously explored. Therefore, we further investigated JUN translation regulation in human cells by exploring different regions of the JUN 5′ UTR and how mRNA features and the interaction of initiation factors in these regions contribute to JUN translation. Firstly, we applied mutagenesis to the JUN 5′ UTR near the eIF3 binding site. We also further investigated the contributions of eIF4A to JUN translation both by mRNA mutagenesis and through cellular treatment with RocA. Finally, we explored how the translational context of both of the JUN start codons affect start site selection. Our results demonstrate that JUN translation regulation is a complex multilayered process that involves various initiation factors, including eIF3 and eIF4A, and mRNA features such as secondary structures in the 5’ UTR.

Results

JUN translation is regulated by 5’ UTR sequence and structural elements

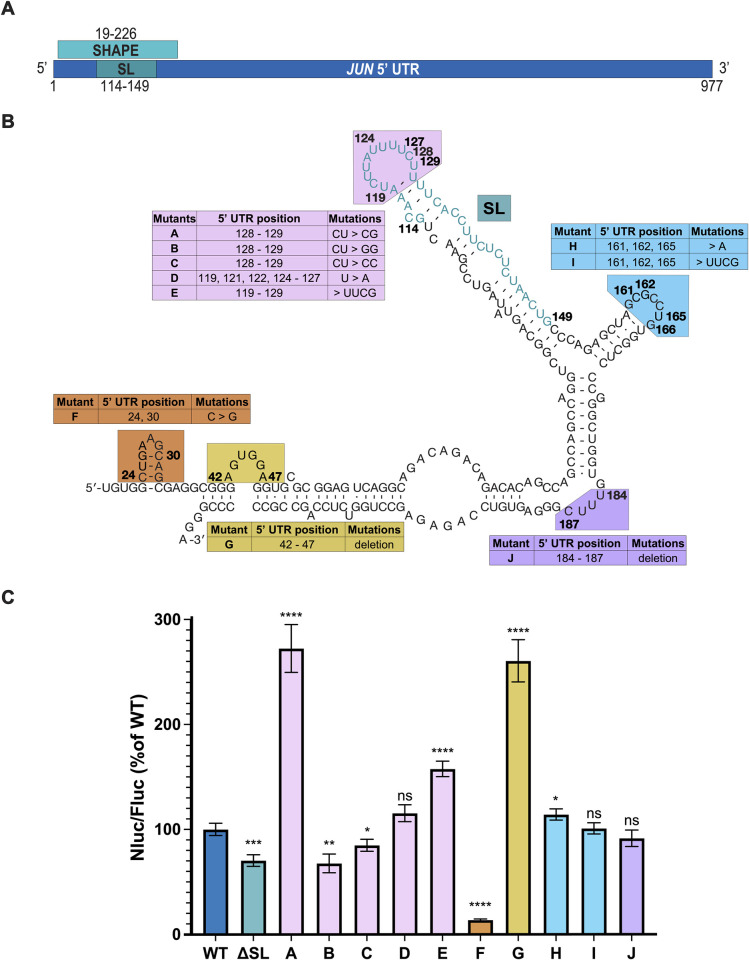

Binding of eIF3 to a stem-loop in the 5’ UTR of the JUN mRNA leads to its translational activation [18]. Mutations in this stem loop have been shown to disrupt the interaction with eIF3 and to repress JUN translation [18]. However, the effects of other mutations in the JUN 5′ UTR remain to be explored. We first tested whether mutations in other regions within and near the JUN-eIF3 interacting stem loop (SL) affect JUN translation. We generated mRNA reporter constructs containing the full-length JUN 5′ UTR and Nanoluciferase (Nluc) coding sequence (CDS) that included mutations in a 208 nucleotide (nt) SL proximal region whose secondary structure was previously determined [18] by selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension, also known as SHAPE (Fig 1A, SHAPE). All of the mutations disrupt either the secondary structure or the sequence of highly structured regions within the SL proximal region (Fig 1B). For each of these constructs transfected into HEK293T cells, together with an mRNA reporter with the Hemoglobin Beta Subunit (HBB) 5′ UTR and a Firefly luciferase (Fluc) CDS as an internal control, we assessed translation using luciferase assays.

Fig 1. JUN translation is regulated by 5’ UTR sequence and structural elements.

(A) Depiction of the full JUN 5’ UTR. The locations of the 208-nt region studied by SHAPE (SHAPE) and the eIF3-interacting stem loop (SL) are marked, along with the nucleotides involved in each region. (B) Secondary structure of the 208-nt region in the JUN 5’ UTR mapped by SHAPE is shown. Nucleotides are numbered according to their position in the 5′ UTR. Mutant JUN 5′ UTR mRNA constructs and their corresponding mutations are described in their associated tables. (C) Luminescence measured from HEK293T cells transfected with the JUN 5′ UTR reporter mRNAs expressing Nanoluciferase (Nluc). Translation was assessed using a dual-luciferase assay and normalized to a control mRNA harboring an HBB 5′ UTR and a Firefly luciferase (Fluc) CDS. Nluc/Fluc ratios were normalized to the WT JUN 5′ UTR, set as 100%. Technical triplicates for each biological replicate, and a total of at least three biological replicates were taken for each measurement. P values determined using a one-sample t test versus a hypothetical value of 100 are shown as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. The mean value of the replicates and standard error of the mean are shown.

As expected, deletion of the JUN-eIF3 interacting stem loop (Fig 1C, mutant ΔSL) significantly represses JUN reporter translation when compared to the WT construct. Mutations to SL loop nucleotides C128-U129, previously shown to be unreactive by SHAPE mapping in vitro and therefore likely to be involved in RNA-RNA contacts, also significantly affected JUN reporter translation, with U129G dramatically increasing translation (Fig 1C, mutant A) [18]. Interestingly, replacing the SL loop with a much smaller and possibly more stable UUCG tetraloop substantially increased JUN reporter translation (Fig 1C, mutant E) [59]. However, replacing all of the U’s with A’s in the loop sequence had little effect on JUN translation (Fig 1C, mutant D). As a whole, these findings support the importance of the SL loop in JUN translation regulation, yet reveal a complexity in its role maintaining and stabilizing the secondary structure of the SL region. Mutations in other structured regions of the JUN 5′ UTR near the eIF3 binding site also significantly affected JUN translation. For example, disrupting the stem loop between nucleotides 23 and 33 with point mutations in nucleotides 24 and 30 repressed JUN reporter translation (Fig 1C, mutant F). By contrast, deleting the bulge loop formed by nucleotides 42 to 47 increased JUN reporter translation (Fig 1C, mutant G). These findings suggest that these secondary structure features in the JUN 5′ UTR outside the originally identified eIF3 binding site play opposing roles in regulating JUN translation. However, mutations to two other loop and bulge regions near the SL (nts 160–166 and 184–187) had little or no effect on JUN reporter translation (Fig 1C, mutants H-J).

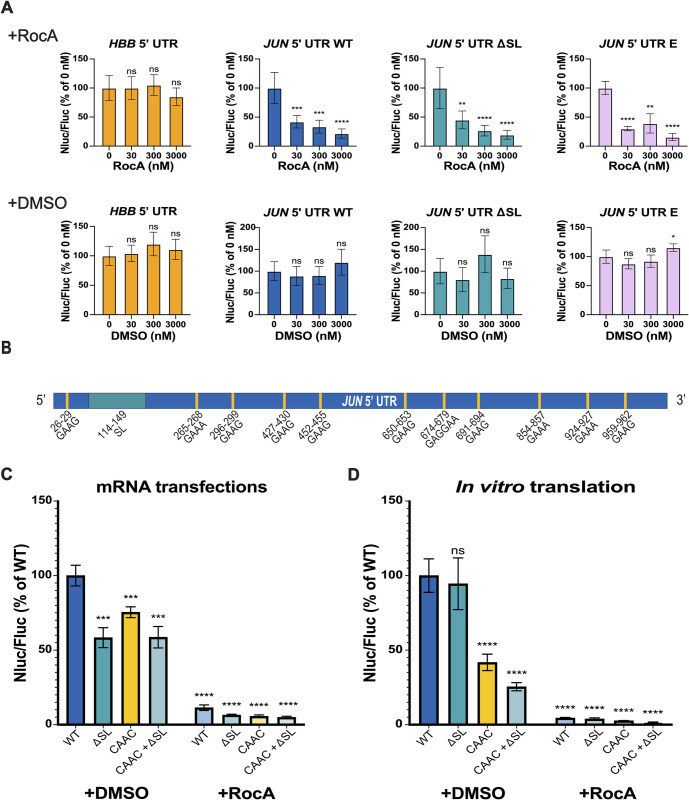

JUN is highly sensitive to RocA treatment

Rocaglamide A (RocA) is an anti-cancer compound that specifically clamps eIF4A onto polypurine sequences in a subset of mRNAs, in an ATP-independent manner. This clamping of eIF4A blocks 43S scanning, leading to premature, upstream translation initiation and reducing protein expression from transcripts containing RocA–eIF4A target sequences [33, 34]. Interestingly, JUN is one of the mRNAs identified as highly sensitive to RocA treatment [33]. However, little is known about how promoting or disrupting the JUN interaction with eIF4A affects JUN translation. To this end, we first transfected JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc mRNA reporter constructs designed above (Fig 1B) together with the HBB 5′ UTR and Fluc CDS control mRNA, into HEK293T cells and treated these with increasing concentrations of RocA or DMSO (as a negative control). In all the cases we tested, including the WT, ΔSL, and the UUCG tetraloop mutation in the SL loop, treatment with RocA strongly suppressed JUN reporter translation (Fig 2A). This effect was not observed for the control Nluc reporter mRNA harboring the HBB 5′ UTR, which has not been reported as RocA sensitive. The fact that constructs with mutations that affect the eIF3-interacting stem loop in the JUN 5′ UTR were still highly sensitive to RocA treatment suggests that the RocA-mediated effects on the JUN 5′ UTR are independent of eIF3 regulation. The persistent repressive trend of RocA treatment on JUN translation also suggests that eIF4A serves an important role in JUN translation regulation.

Fig 2. JUN is highly sensitive to RocA treatment.

(A) HEK293T cells co-transfected with JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS reporter mRNAs (WT, ΔSL or mutant G, Fig 1) and with an HBB 5’ UTR and Fluc mRNA as an internal control, were treated with increasing concentrations of RocA (+RocA) or DMSO control (+DMSO) 3 hours post-transfection, as previously reported [33]. An mRNA with the HBB 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS mRNA was also used as a RocA-insensitive control. Translation was assessed using a dual-luciferase assay as in Fig 1. Nluc/Fluc measurements were normalized to the corresponding untreated condition (0 nM RocA) and reported as a percentage of this measurement. (B) The location of polypurine (GAA(G/A)) sequences in the JUN 5′ UTR are indicated with yellow lines. Each of these 11 sequences was mutated to CAAC. (C) Luminescence of HEK293T cells transfected with JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS reporter mRNAs (WT, ΔSL, CAAC or CAAC + ΔSL), together with the HBB 5′ UTR and Fluc CDS mRNA control. Transfected cells were treated with 300 nM RocA (+RocA) or DMSO (+DMSO) 3 hours post-transfection. Translation was assessed using a dual-luciferase assay as in Fig 1, and Nluc/Fluc measurements were normalized to the WT JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS +DMSO measurements, reported as percentages. (D) Luminescence from in vitro translation reactions using the JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS reporter mRNAs (WT, ΔSL, CAAC or CAAC + ΔSL). Reactions were treated with 300 nM RocA (+RocA) or DMSO (+DMSO). Luminescence values of each mutant were normalized to the WT JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS +DMSO measurements and reported as percentages. In panels A, C, and D, technical triplicates for each biological replicate, and a total of at least three biological replicates were taken for each measurement. P values determined using a one-sample t test versus a hypothetical value of 100 are shown as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. The mean value of the replicates and standard error of the mean are shown.

RocA-sensitive mRNAs are enriched in the polypurine sequence GAA(G/A) [33]. As shown in Fig 2B, JUN possesses 11 of these polypurine sequences across the entire length of its 5′ UTR, with none present in the eIF3-interacting stem loop. In order to evaluate the effect of disrupting these sequences in the JUN 5′ UTR, we mutated these polypurine (GAA(G/A)) sequences to the mixed purine/pyrimidine sequence CAAC, previously reported to disrupt RocA-mediated eIF4A binding to mRNAs [34]. Interestingly, the JUN reporter mRNAs with these mutations (mutants CAAC or CAAC + ΔSL) remained highly sensitive to RocA (Fig 2C). This indicates that there are additional eIF4A target sequences in the JUN 5′ UTR that are not necessarily equivalent to the reported predominant GAA(G/A) motif. Moreover, deleting the eIF3 interacting stem loop, together with the GAA(G/A) mutations (mutant CAAC + ΔSL), has no further effect on translation. We observed similar effects with the JUN mRNA reporters in vitro using HEK293T cell extracts (Fig 2D). Taken together, these results support a model in which eIF4A regulates JUN translation in an eIF3 independent manner, pointing to further layers of regulation for JUN translation, mediated by additional initiation factors.

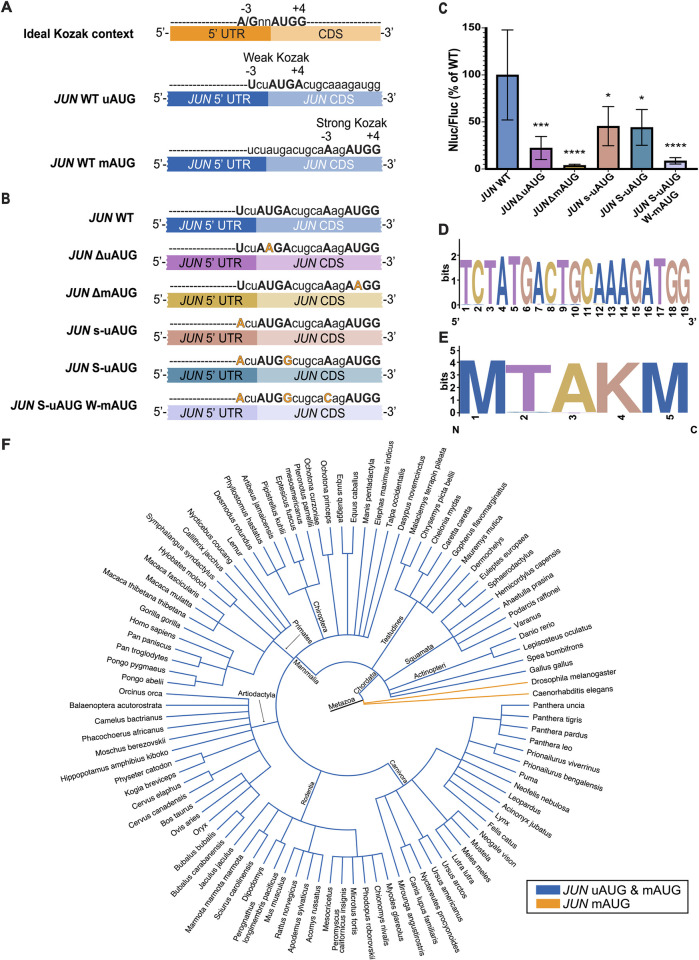

Two start codons contribute to JUN translation in cells

Start codon selection regulates the translation of many transcripts [38–41, 60, 61]. Recently, it was reported that the translational context of start codons on transcripts with an upstream open reading frame (uORF) and a main open reading frame (mORF) affects which of these is preferentially selected for translation, mediated by eukaryotic initiation factor 1 (eIF1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 5 (eIF5) [41]. While eIF1 promotes skipping of weak translational start sites, eIF5 increases initiation at these sites. The relative abundance of these two factors determines which start codon is used. The strongest translational context, also known as the ideal Kozak sequence context, contains a purine at the -3 position, preferably an adenosine (A), and a guanosine (G) at the +4 position, relative to the AUG start codon (Fig 3A). A weak translational context results when either of these purines at the -3 and +4 positions is substituted by a pyrimidine. The JUN mRNA possesses two AUG start codons, an in-frame upstream AUG (uAUG) four codons before a main AUG (mAUG), with different translational contexts (Fig 3A). The JUN uAUG possesses a weak translational context, with a uridine (U) at the -3 position and an adenosine (A) at the +4 position. By contrast, the JUN mAUG has a strong translational context, with an adenosine (A) at the -3 position and a guanosine (G) at the +4 position. It is not known which of these JUN AUGs is preferentially selected for translation and there currently is no evidence of JUN peptides that initiate at the uAUG.

Fig 3. Two start codons contribute to JUN translation.

(A) Diagram depicting the ideal Kozak context for a generic open reading frame (A/GnnAUGG). Below, diagrams depicting each of the JUN start codons (AUG) and their translational contexts. (B) Diagram depicting JUN mRNA reporter constructs, with their corresponding mutations in each of the JUN start codons and their translational contexts. The constructs contained the full JUN 5′ UTR sequence along with the first 51 nucleotides of the JUN CDS, upstream of the full Nluc CDS. (C) Luminescence from HEK293T cells transfected with JUN 5′ UTR and 51nt JUN CDS and Nluc CDS reporter mRNAs (WT, ΔuAUG, ΔmAUG, s-uAUG, S-uAUG or S-uAUG W-mAUG), together with an HBB 5′ UTR and Fluc CDS control, assessed using a dual-luciferase assay as in Fig 1. Nluc/Fluc measurements of each mutant were normalized to the WT JUN 5′ UTR and 51nt JUN CDS and Nluc CDS measurements and reported as percentages. Technical triplicates for each biological replicate, and a total of at least three biological replicates were taken for each measurement. P values determined using a one-sample t test versus a hypothetical value of 100 are shown as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. The mean value of the replicates and standard error of the mean are shown. (D) Sequence logo depicting the conservation of the 19 nucleotide JUN sequence spanning both start codons and their translational context amongst 100 species. (E) Sequence logo depicting the conservation of the 5 amino acid JUN sequence containing both start codon methionines amongst 100 species. (F) Phylogenetic tree depicting the conservation of both JUN AUGs amongst 100 species. Species with both the JUN uAUG and the JUN mAUG are depicted with blue branches, while species with only one JUN mAUG are depicted in orange.

To investigate whether JUN translation can initiate at either AUG or whether one is preferentially selected, we designed mRNA reporter constructs containing the JUN 5′ UTR and the first 51 nucleotides of the JUN CDS (corresponding to 17 amino acids), followed by the full Nluc CDS (Fig 3B). The WT version of this construct therefore contains both JUN AUG start codons and their intact translational contexts. We then mutated start codons individually or their translational context to test their roles in JUN translation. We transfected these mRNA reporters into HEK293T cells, together with the HBB 5′ UTR and Fluc CDS control, and monitored translation using luciferase assays. In general, disrupting either AUG or changing their translational context significantly represses JUN translation, which in turn suggests that translation can initiate at both AUGs (Fig 3C). We found that disrupting either AUG by mutation to AAG repressed JUN reporter translation, consistent with both AUGs contributing to JUN translation (Fig 3B and 3C). The more substantial decrease in JUN reporter translation due to the mAUG (JUN ΔmAUG, 95% reduction) compared to mutation of the uAUG (JUN ΔuAUG, 75% reduction) suggests that the mAUG start codon may be preferred in our experimental conditions.

Changing the translational context of either AUG also repressed JUN translation. Interestingly, making the sequence context for the uAUG stronger–either by introducing an A in the -3 position of the upstream AUG (Fig 3B) or by also including a G mutation in the +4 position to make it an ideal Kozak sequence–resulted in a 50% decrease in translation (Fig 3C). Moreover, using the uAUG in a strong Kozak context while weakening the translational context of the mAUG further represses JUN translation, to about 10% of the WT levels (Fig 3C, mutant S-uAUG W-mAUG). Taken together, these results strongly support the hypothesis that both AUGs are used for translation, and that the preference for which AUG is selected for initiation depends partly on its translational context.

JUN uAUG and mAUG are conserved in vertebrates

To further investigate whether both JUN AUGs contribute to its translation, we examined sequence conservation of the JUN 5′ UTR and early CDS region that contains both AUG start codons and their translational context. We searched the 19-nucleotide region spanning the Kozak contexts of both AUGs in 100 species using the Genome Data Viewer (NLM-NCBI) and Ensembl for sequence confirmation (S1 Table). Remarkably, sequences in this region are conserved both at the nucleotide and at the amino acid level in the species examined (Fig 3D and 3E). Conservation of both JUN AUGs is present in all vertebrates [62], whereas only the mAUG is present in the invertebrates we investigated (Fig 3F). This conservation of both of JUN’s AUGs and their translational context suggests an ancient mechanism for JUN translation regulation and highlights the importance of both JUN AUGs.

Discussion

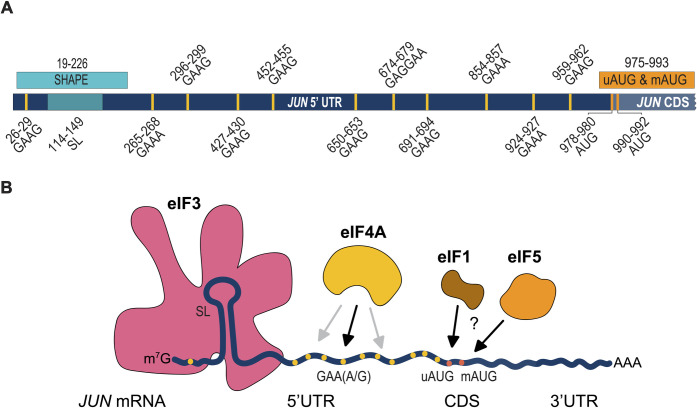

Given that JUN was the first oncogenic transcription factor identified [51, 52] it is notable how little is known mechanistically about how JUN expression is controlled at the translational level. In this work we probed the contributions of mRNA features and initiation factors to JUN translation regulation in human cells. Our study reveals that JUN translation regulation is a complex process that is mediated by mRNA target sequences and structural elements spanning the entire JUN 5′ UTR (Fig 4A). Moreover, we provide evidence that initiation factors in addition to eIF3 [18] contribute to JUN translation regulation (Fig 4B). We also found that both the uAUG and mAUG contribute to JUN translation. Given that the JUN 5′ UTR has a length that exceeds the average 218 nt human 5′ UTR [63], a high level of secondary structure [18], and a GC rich sequence, our hypothesis is that many features within its 5′ UTR that participate in its regulation are still unknown.

Fig 4. JUN translation regulation is mediated by 5’ UTR features and multiple translation initiation factors.

(A) Diagram showing all JUN regions investigated in this study. (B) Diagram depicting different contributors to JUN translation regulation. These factors include: JUN mRNA secondary structure (depicted as a stem loop in the 5′ UTR), JUN sequences (such as the GAA(A/G) polypurine sequences depicted in yellow), JUN AUGs (depicted in orange), and initiation factors (such as eIF3, eIF4A, and potentially eIF1 and eIF5). EIF3 (depicted in pink) interacts with structured regions of the JUN 5’ UTR. EIF4A (depicted in yellow) interacts with GAA(A/G) sequences (black arrow) and with other unknown sequences (gray arrows) in the JUN 5’ UTR. EIF1 (depicted in brown) and eIF5 (depicted in orange) may play roles in JUN start codon selection.

Previous results found that eIF3 can directly bind structures in the 5’ UTR of specific mRNA transcripts to regulate their translation, with JUN serving as a prototypical example [18]. Here we explored the regulatory roles of RNA structural elements within or near the eIF3-interacting stem loop (SL) region of the JUN 5’ UTR (Fig 1). In addition to the importance of this SL for enhancing JUN translation in cells, we found that replacing the SL loop by a highly-stable UUCG tetraloop [59] increases JUN translation. It is possible that significant local rearrangements may be required for the canonical JUN SL loop sequence to bind eIF3 or that the canonical SL loop is highly dynamic, and insertion of the UUCG tetraloop locks this structure in the most favorable conformation for eIF3 binding. Additionally, there may be some sequence specificity in the SL loop, as mutation of two nucleotides in the context of the wild-type loop at positions 128 and 129 also affect JUN translation levels (Fig 1). Interestingly, the ability of this eIF3-interacting SL structure to promote translation is shown by the fact that it can be inserted in a modular way into the 3′ UTR of reporter mRNAs to promote translation, as shown in activated T cells [20]. We also found additional structural elements besides the eIF3-interacting SL that contribute to JUN translation. Most notably, these are a stem loop between nucleotides 23 and 33 of the JUN 5′ UTR and a bulge loop between nucleotides 42 and 47, which enhance or repress translation, respectively (Fig 1). These secondary structure elements may serve potential regulatory roles, similar to the one shown for the eIF3-interacting SL. These results are consistent with previous findings which have correlated long and highly structured 5′ UTRs with complex regulation mediated by eIF3 [58]. However, it remains to be determined whether eIF3 interacts directly with these regions. It is also possible these secondary structure elements mediate additional regulatory interactions [63]. Further evidence will be required to determine whether additional initiation factors interact with the structural elements studied in this SL-proximal region. Moreover, it would be interesting to investigate the effect of combinations of mutations in the structure and sequence elements found to influence JUN translation, and how these combinations affect eIF3 binding to the JUN 5’ UTR. Regarding the eIF3-binding region, it is important to note that in vitro experiments with the JUN 5’ UTR ΔSL construct have consistently shown less robust translational repression when compared to experiments done in cells (Fig 2). Because of this, we hypothesize that the mechanism that regulates translation of this mRNA reporter construct requires elements predominantly active in vivo.

We also found evidence for a role for eIF4A in JUN translation regulation. We demonstrated that JUN is highly sensitive to RocA, consistent with prior transcriptome-wide experiments [33] and with JUN being a target of eIF4A regulation (Fig 2). Interestingly, RocA sensitivity is independent of JUN interactions with eIF3, since mutations in the JUN eIF3-interacting SL did not affect its sensitivity to RocA (Fig 2). RocA sensitivity of additional JUN mRNA mutations near the eIF3-binding site in the 5’ UTR is an area of interest for future studies. RocA was shown to clamp eIF4A onto GAA(G/A) polypurine sequences in a subset of RocA sensitive mRNAs and these mRNAs are in fact rich in these tetramer motifs [33]. Notably, JUN possesses 11 of these GAA(G/A) motifs in its 5’ UTR; however, mutating these sequences to CAAC did not overcome JUN sensitivity to RocA, suggesting that RocA may clamp eIF4A onto additional polypurine sequences in the JUN 5′ UTR different from the predominant motif previously identified [33]. A potential polypurine sequence present in the JUN 5′ UTR and to which RocA might clamp eIF4A is AGAG [34]. Within eIF3, subunit EIF3D can bind to the JUN mRNA 5′-7-methylguanosine cap structure, while an RNA structural element adjacent to the cap blocks recruitment of the eIF4F complex [19]. However, our results with RocA treatment suggest that at least some of the eIF4F components may contribute to JUN mRNA recruitment and scanning. This suggests that there may be a novel mRNA recruitment complex for JUN, in which eIF4A is present despite the absence of eIF4E, with EIF3D possibly acting as the cap-binding protein in this context. Our results on the involvement of eIF4A in JUN translation are surprising when compared to results shown in a previous study [19]. This discrepancy could be due to differences on the experimental approach. In previously reported experiments, 48S-like complexes were isolated using sucrose gradients. It is possible that these complexes represent a late stage of translation initiation and that eIF4A plays a role at an earlier stage. Future studies evaluating this will be required to dissect the step-to-step mechanism of JUN translation initiation.

Although JUN possesses a 5’ UTR nearly 1 kb in length, it also has two closely-spaced potential start codons, an upstream start codon (uAUG) 4 codons away from a downstream “main” AUG (mAUG). However, which of these start codons is preferentially selected and whether they both contribute to JUN translation is currently unknown. Notably, experimental evidence for usage of the uAUG would be missed in published mass spectrometry experiments due to presence of a lysine at codon -1 relative to the mAUG, which would lead to removal of the leading peptide in commonly-used trypsin digests. Using reporters with the full-length JUN 5’ UTR and both AUGs, we find that both AUGs likely contribute to JUN translation, albeit in a complex way (Fig 3). For example, deleting each AUG individually, repressed JUN translation significantly, with deletion of the mAUG causing a more severe reduction. However, the contexts of the uAUG and mAUG do not always correlate with translational output. For example, changing the weak context of the uAUG seen in WT JUN into a strong context decreased translation by 50% rather than increasing it. In this case, the mAUG is also likely used, as weakening the translational context of the mAUG in the strong uAUG context background further repressed translation to about 10% of WT levels. These results suggest that while both AUGs contribute to JUN translation, perhaps the mAUG plays a major role. These results also raise the possibility that translational efficiency of the first 4 codons including the uAUG may be lower than that of the mAUG, which would result in a lower translational output from the uAUG when it is used.

The fact that both AUGs may contribute to JUN translation suggests they may be part of a regulatory switch in varying cellular conditions. For example, unwinding of an RNA secondary structure downstream of an uAUG in an immune response promotes translation initiation at the mAUG of specific mRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana [64]. Other cellular conditions, such as stress, starvation, or polyamine abundance could influence start codon selection [35, 39, 65, 66]. Finally, the relative abundance of eIF1 and eIF5 –which regulate the stringency of start codon selection [38, 40, 41]–could influence which JUN start codon is used, and thus the translational output of the JUN mRNA. Further experiments will be needed in order to test this hypothesis.

When exploring the evolution of JUN’s AUGs we found that both are conserved in vertebrates, which suggests an ancient mechanism of regulation for JUN by means of translational start site selection. Importantly, the translational context is also conserved for most of the examined species (Fig 3D and 3E, S1 Table), suggesting that the translational context plays a significant role in determining which start codon is selected. Our observations align with previous reports which showed that uAUGs are highly conserved in higher eukaryotes due to their roles in regulating translation initiation under regulatory circumstances [67, 68]. In addition, the evolutionary conservation suggests that more than one JUN polypeptide may be expressed by initiation of translation at both the uAUG and the mAUG. This type of alternative initiation has been shown previously by leaky scanning of uAUGs in a weak translational context, especially of those that are close to their downstream mAUG which allows for backward oscillation of the ribosome [69, 70]. Further studies are needed in order to test whether JUN leads to expression of more than one polypeptide, depending on the start codon selected. For example, this would require using a different protease for mass spectrometry besides trypsin to avoid cleavage after the lysine at position -1 relative to the mAUG, to retain N-terminal peptides originating at the uAUG.

It is notable that many different mechanisms regulate JUN expression at the translational level. Our study demonstrates the potential of the JUN mRNA as a model transcript for understanding new mechanisms of mRNA translation regulation. It opens the doors for further exploration of the regulatory roles of long and highly structured 5′ UTRs and the initiation factors that participate in translation regulation. It also points to possible new roles for JUN mRNA translation levels in mediating cellular response to a wide array of physiological conditions.

Materials and methods

Reporter plasmids

To generate the JUN 5′ UTR and the HBB 5′ UTR Nluc reporter plasmids, the JUN 5′ UTR (ENST00000371222.4) previously generated by amplification from human cDNA [18] and the HBB 5′ UTR (ENST00000335295.4) commercially generated (IDT) sequences were each inserted into the pNL1.1 NanoLuc luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega, GenBank Accession Number JQ437370) downstream of a T7 promoter using overlap-extension PCR with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) and InFusion cloning (Takara Bio). For the JUN AUG mutants, the first 51 nucleotides of the JUN CDS were inserted downstream of the full JUN 5′ UTR sequence and upstream of the full Nluc CDS in the pNL1.1 plasmid. For the Fluc reporter plasmid, the HBB 5′ UTR Nluc reporter plasmid was amplified and the NanoLuc luciferase sequence was replaced by a commercially generated Firefly luciferase sequence (IDT) [71]. Subsequent mutant versions of the JUN reporter plasmids were made by amplifying the plasmid using overlap-extension PCR with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) and primers containing the corresponding mutations, insertions, or deletions, followed by InFusion cloning (Takara). All primers used for amplification can be found in S2 Table. All sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing. Protocol available: http://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.kqdg3xoyzg25/v1.[PROTOCOL DOI].

In vitro transcription

All RNA reporters were made by in vitro transcription with a standard T7 RNA polymerase protocol using DNA template gel extracted using the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo), 1x T7 RNA Polymerase buffer (NEB), 5 mM ATP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 mM CTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 mM GTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5mM UTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 μg BSA (NEB), 9 mM DTT, 25 mM MgCl2, 200U T7 RNA polymerase (NEB), 50U Murine RNAse inhibitor (NEB) and incubating for 4 hours at 37°C. The DNA template used for in vitro transcription was generated by PCR amplification from the corresponding reporter plasmid using the Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) with a reaction including a forward primer containing the T7 promoter sequence and a 60T reverse primer for polyadenylation. Primers used for each transcript can be found in S2 Table. After in vitro transcription, RNAs were treated with DNAse (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol and precipitated with 7.5 M lithium chloride. RNAs were then capped using Vaccinia D1/D2 (Capping enzyme) (NEB) and 2′ O-methylated using Vaccinia VP39 (2′ O Methyltransferase) (NEB) in a reaction that also included 1X capping buffer (NEB), 10 mM GTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4 mM SAM (NEB). RNAs were then purified with the RNA Clean and Concentrator-5 Kit (Zymo). In order to verify the integrity of the in vitro transcribed mRNAs, 6% polyacrylamide TBE-Urea denaturing gels were run using 1X TBE (Invitrogen), a ssRNA ladder (NEB) and SYBR safe stain (see representative gel in S1 Fig). Protocol available: http://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.ewov1qwxpgr2/v1.[PROTOCOL DOI.

HEK293T cells and mRNA transfections

HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (VWR) and 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco). Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide and 100% humidity. Luciferase reporter mRNAs were transfected into these cells using the TransIT-mRNA Transfection Kit (Mirus), with the following protocol modifications. HEK293T cells were seeded into opaque 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) about 16 hours prior to transfections. The next day, once the cells reached 80% confluency, transfections were performed by adding the following to each well: 7 μL of pre-warmed OptiMEM media (Invitrogen), 500 ng of the corresponding 5′ -capped and 3′ -polyadenylated JUN 5’ UTR and Nluc CDS reporter mRNA, 150 ng of 5′ -capped and 3′ -polyadenylated HBB 5’ UTR and Fluc CDS reporter mRNA, 2 μL of Boost reagent (Mirus Bio) and 2 μL of TransIT mRNA reagent (Mirus Bio). In this context, the HBB 5’ UTR and Fluc CDS construct serves as an internal control to account for transfection efficiency and mRNA stability. Transfection reactions were incubated at room temperature for 3 minutes prior to drop-wise addition into each well. For experiments presented in Fig 2A, transfected cells were treated with increasing concentrations of RocA (+RocA) or DMSO control (+DMSO) 3 hours post-transfection, as previously reported [33]. An mRNA with the HBB 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS mRNA was used as a RocA-insensitive control. Transfected cells were incubated at 37°C for 8 hours, after which luciferase assays were performed using the NanoGlo Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Luminescence was then measured independently for the Nluc construct and for the Fluc construct in each sample using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN). Nluc/Fluc ratios were calculated and normalized to the corresponding control condition, set as 100%. Technical triplicates for each biological replicate, and a total of at least three biological replicates were taken for each measurement. P values were determined using a one-sample t test versus a hypothetical value of 100. The mean value of the replicates and standard error of the mean were plotted. Protocol available: http://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.36wgq3zyklk5/v1.[PROTOCOL DOI].

HEK293T pSB-HygB-GADD34-K3L cells and extract preparation

HEK293T pSB-HygB-GADD34-K3L cells were maintained in DMEM media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Tet-system approved FBS (Gibco) and 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco) [72]. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide and 100% humidity. Cells were grown for extract preparation as follows. The day after plating cells from a frozen stock into a T25 flask (Cell Star), media was exchanged and supplemented with 200 μg/mL Hygromycin B (Invitrogen). The following day, cells were transferred to a T75 flask (Corning) with media supplemented with 200 μg/mL Hygromycin B. Once cells reached 100% confluency, half of the cells were transferred to a T175 flask (Falcon) with media supplemented with 200 μg/mL Hygromycin B. Once cells reached 100% confluency, cells were passaged onto 25 150 mm plates (Corning) at a 1 to 25 ratio. The next day, cells were treated overnight with 20 μg Doxycycline (Takara Bio) per plate.

In vitro translation extracts were made from HEK293T pSB-HygB-GADD34-K3L cells using a previously described protocol [72]. Cells were placed on ice, scraped and collected by centrifugation at 1000 xg for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed once with ice-cold DPBS (Gibco) and collected once again by centrifugation at 1000 xg for 5 minutes at 4°C. After this, cells were homogenized with an equal volume of freshly made ice-cold hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 10 mM KOAc, 0.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 5 mM dithiothreitol). After hypotonic-induced swelling for 45 minutes on ice, cells were homogenized using a syringe attached to a 26G needle (BD). Extract was then centrifuged at 15000 xg for 1 minute at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was aliquoted, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C. Protocol available: http://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.eq2lyjr2mlx9/v1.[PROTOCOL DOI].

In vitro translation

In vitro translation reactions were performed using HEK293T pSB-HygB-GADD34-K3L translation-competent cell extract, as previously described [72]. Translation reactions contained 50% translation-competent cell extract, 52 mM HEPES pH 7.4 (Takara), 35 mM potassium glutamate (Sigma), 1.75 mM Mg(OAc)2 (Invitrogen), 0.55 mM spermidine (Sigma), 1.5% Glycerol (Fisher Scientific), 0.7 mM putrescine (Sigma), 5 mM DTT (Thermo Scientific), 1.25 mM ATP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.12 mM GTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mM L-Arg; 6.7 mM each of L-Gln, L-Ile, L-Leu, L-Lys, L-Thr, L-Val; 3.3 mM each of L-Ala, L-Asp, L-Asn, L-Glu, Gly, L-His, L-Phe, L-Pro, L-Ser, L-Tyr; 1.7 mM each of L-Cys, L-Met; 0.8 mM L-Trp, 20 mM creatine phosphate (Roche), 60 μg/mL creatine kinase (Roche), 4.65 μg/mL myokinase (Sigma), 0.48 μg/mL nucleoside-diphosphate kinase (Sigma), 0.3 U/mL inorganic pyrophosphatase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 μg/mL total calf tRNA (Sigma), 0.8 U/μL RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific), and 1000 ng of the corresponding mRNA. Reactions were then incubated for 60 minutes at 32°C, and Nanoluciferase activity was monitored using the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega) using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN). The average of each biological replicate was normalized to the control condition, set as 100%. Technical triplicates for each biological replicate, and a total of at least three biological replicates were taken for each measurement. P values determined using a one-sample t test versus a hypothetical value of 100 are shown as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. The mean value of the replicates and standard error of the mean were plotted. Protocol available: http://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bp2l6x6yklqe/v1.[PROTOCOL DOI].

Conservation analysis for JUN AUGs

The 19-nucleotide JUN 5′ UTR and JUN CDS region that spans both AUG start codons and their translational context was searched in 100 species. Species were selected randomly, starting with Homo sapiens and increasing the evolutionary distance throughout the vertebrates up to the invertebrates (S1 Table). Species sequences were compiled using the Genome Data Viewer (NLM-NCBI) and Ensembl. Sequence logos for the conserved nucleotide and amino acid sequences were created using WebLogo (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) [73, 74]. Taxonomy analysis for the species of interest was performed using the NCBI Taxonomy Browser [62, 75]. Phylogenetic tree was generated using FigTree v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Supporting information

6% TBE-Urea gel for in vitro transcribed mRNA for the WT or ΔSL JUN 5′ UTR and Nluc CDS reporter constructs. nt, nucleotide.

(TIF)

Compilation of species investigated for JUN AUGs conservation analysis, including the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the 19-nucleotide JUN 5′ UTR and JUN CDS region that spans both AUG start codons and their translational context for each species, the corresponding Reference Sequence (RefSeq) accession numbers for each sequence, and the percent similarity of each sequence to the human JUN sequence.

(XLSX)

Compilation of primer sequences used for cloning and in vitro transcription amplification of each reporter construct used in this study.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Cate laboratory for helpful discussions; Amy S. Y. Lee and Wenfei Li for sharing plasmids encoding JUN 5’UTR and JUN 5’ UTR ΔSL; Nikolay Aleksashin for HEK293T pSB-HygB-GADD34-K3L cells; Wenfei Li, Dasmanthie De Silva, Amy S. Y. Lee, and Nicholas T. Ingolia for experimental suggestions and advice; Sona Trika and Cameron Baker for contributions to initial experiments and data exploration; Amos Nissley, Santiago Mestre-Fos, and Pooja Mukherjee for critical reading of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data are in the manuscript and/or supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01-GM065050 and R35-GM148352) to J.H.D.C. https://reporter.nih.gov/ The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Buttgereit F, Brand MD. A hierarchy of ATP-consuming processes in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1995;312(Pt 1):163–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1136240/ doi: 10.1042/bj3120163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of Translation Initiation in Eukaryotes: Mechanisms and Biological Targets. Cell. 2009;136(4):731–45. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3610329/ doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N. mRNA translation and energy metabolism in cancer: the role of the MAPK and mTORC1 pathways. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:355–67. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershey JWB, Sonenberg N, Mathews MB. Principles of translational control: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(12):a011528. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leibovitch M, Topisirovic I. Dysregulation of mRNA translation and energy metabolism in cancer. Adv Biol Regul. 2018;67:30–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5993950/ doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachs AB, Varani G. Eukaryotic translation initiation: there are (at least) two sides to every story. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(5):356–61. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nsb0500_356 doi: 10.1038/75120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson RJ, Hellen CUT, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(2):113–27. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm2838 doi: 10.1038/nrm2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinnebusch AG. Molecular Mechanism of Scanning and Start Codon Selection in Eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75(3):434–67. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/mmbr.00008-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aitken CE, Lorsch JR. A mechanistic overview of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(6):568–76. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nsmb.2303 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen DS, Savner EM, Mathew A, Zhang F, Krishnamoorthy T, Phan L, et al. Domains of eIF1A that mediate binding to eIF2, eIF3 and eIF5B and promote ternary complex recruitment in vivo. EMBO J. 2003;22(2):193–204. Available from: https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1093/emboj/cdg030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinnebusch AG. The Scanning Mechanism of Eukaryotic Translation Initiation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83(1):779–812. Available from: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asano K, Shalev A, Phan L, Nielsen K, Clayton J, Valášek L, et al. Multiple roles for the C-terminal domain of eIF5 in translation initiation complex assembly and GTPase activation. EMBO J. 2001;20(9):2326–37. Available from: https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1093/emboj/20.9.2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Algire MA, Maag D, Savio P, Acker MG, Tarun SZ, Sachs AB, et al. Development and characterization of a reconstituted yeast translation initiation system. RNA. 2002;8(3):382–97. Available from: http://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/8/3/382 doi: 10.1017/s1355838202029527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumdar R, Bandyopadhyay A, Maitra U. Mammalian Translation Initiation Factor eIF1 Functions with eIF1A and eIF3 in the Formation of a Stable 40 S Preinitiation Complex*. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(8):6580–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021925820866605 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210357200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolupaeva VG, Unbehaun A, Lomakin IB, Hellen CUT, Pestova TV. Binding of eukaryotic initiation factor 3 to ribosomal 40S subunits and its role in ribosomal dissociation and anti-association. RNA. 2005;11(4):470–86. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1370736/ doi: 10.1261/rna.7215305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pestova TV, Borukhov SI, Hellen CUT. Eukaryotic ribosomes require initiation factors 1 and 1A to locate initiation codons. Nature. 1998;394(6696):854–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/29703 doi: 10.1038/29703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG. The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev. 2002;16(22):2906–22. Available from: http://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/16/22/2906 doi: 10.1101/gad.1020902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee ASY, Kranzusch PJ, Cate JHD. eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature. 2015;522(7554):111–4. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14267 doi: 10.1038/nature14267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee ASY, Kranzusch PJ, Doudna JA, Cate JHD. eIF3d is an mRNA cap-binding protein that is required for specialized translation initiation. Nature. 2016;536(7614):96–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature18954 doi: 10.1038/nature18954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Silva D, Ferguson L, Chin GH, Smith BE, Apathy RA, Roth TL, et al. Robust T cell activation requires an eIF3-driven burst in T cell receptor translation. Malissen B, Taniguchi T, editors. eLife. 2021;10:e74272. Available from: doi: 10.7554/eLife.74272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu TR, Lu RF, Romano D, Pitt A, Houslay MD, Milligan G, et al. Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3, Subunit a, Regulates the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(1):88–95. Available from: doi: 10.1128/MCB.05770-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pulos-Holmes MC, Srole DN, Juarez MG, Lee ASY, McSwiggen DT, Ingolia NT, et al. Repression of ferritin light chain translation by human eIF3. eLife. 2019;8:e48193. Available from: doi: 10.7554/eLife.48193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tacca LMA de Pulos-Holmes MC, Floor SN Cate JHD. PTBP1 mRNA isoforms and regulation of their translation. RNA. 2019;25(10):1324–36. Available from: doi: 10.1261/rna.070193.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cate JHD. Human eIF3: from ‘blobology’ to biological insight. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;372(1716):20160176. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2016.0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomes-Duarte A, Lacerda R, Menezes J, Romão L. eIF3: a factor for human health and disease. RNA Biol. 2017;15(1):26–34. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5785978/ doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1391437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamper AM, Fleming RH, Ladd KM, Lee ASY. A phosphorylation-regulated eIF3d translation switch mediates cellular adaptation to metabolic stress. Science. 2020;370(6518):853–6. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abb0993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Li F, Huang L, Polte C, Duan H, Fang J, et al. eIF3 Associates with 80S Ribosomes to Promote Translation Elongation, Mitochondrial Homeostasis, and Muscle Health. Mol Cell. 2020;79(4):575–587.e7. Available from: https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/abstract/S1097-2765(20)30388-9 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf DA, Lin Y, Duan H, Cheng Y. eIF-Three to Tango: emerging functions of translation initiation factor eIF3 in protein synthesis and disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2020;12(6):403–9. Available from: 10.1093/jmcb/mjaa018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukhopadhyay S, Amodeo ME, Lee ASY. eIF3d controls the persistent integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2023;83(18):3303–3313.e6. Available from: https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/abstract/S1097-2765(23)00643-3 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mestre-Fos S, Ferguson L, Trinidad MI, Ingolia N, Cate JHD. eIF3 engages with 3′-UTR termini of highly translated mRNAs in neural progenitor cells. bioRxiv; 2023. [cited 2023 Nov 14]. p. 2023.11.11.566681. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.11.11.566681v1 37986910 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svitkin YV, Pause A, Haghighat A, Pyronnet S, Witherell G, Belsham GJ, et al. The requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) in translation is in direct proportion to the degree of mRNA 5′ secondary structure. RNA. 2001;7(3):382–94. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S135583820100108X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio CA, Weisburd B, Holderfield M, Arias C, Fang E, DeRisi JL, et al. Transcriptome-wide characterization of the eIF4A signature highlights plasticity in translation regulation. Genome Biol. 2014;15(10):476. Available from: doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwasaki S, Floor SN, Ingolia NT. Rocaglates convert DEAD-box protein eIF4A into a sequence-selective translational repressor. Nature. 2016;534(7608):558–61. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature17978 doi: 10.1038/nature17978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwasaki S, Iwasaki W, Takahashi M, Sakamoto A, Watanabe C, Shichino Y, et al. The Translation Inhibitor Rocaglamide Targets a Bimolecular Cavity between eIF4A and Polypurine RNA. Mol Cell. 2019;73(4):738–748.e9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1097276518309961 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hann SR, Sloan-Brown K, Spotts GD. Translational activation of the non-AUG-initiated c-myc 1 protein at high cell densities due to methionine deprivation. Genes Dev. 1992;6(7):1229–40. Available from: http://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/6/7/1229 doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fletcher CM, Pestova TV, Hellen CUT, Wagner G. Structure and interactions of the translation initiation factor eIF1. EMBO J. 1999;18(9):2631–7. Available from: https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1093/emboj/18.9.2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonenberg N, Dever TE. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors and regulators. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13(1):56–63. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X03000095 doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loughran G, Sachs MS, Atkins JF, Ivanov IP. Stringency of start codon selection modulates autoregulation of translation initiation factor eIF5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):2898–906. Available from: doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ivanov IP, Loughran G, Atkins JF. uORFs with unusual translational start codons autoregulate expression of eukaryotic ornithine decarboxylase homologs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(29):10079–84. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0801590105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivanov IP, Loughran G, Sachs MS, Atkins JF. Initiation context modulates autoregulation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1 (eIF1). Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(42):18056–60. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1009269107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanov IP, Saba JA, Fan CM, Wang J, Firth AE, Cao C, et al. Evolutionarily conserved inhibitory uORFs sensitize Hox mRNA translation to start codon selection stringency. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(9):e2117226119. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2117226119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinnebusch AG. eIF3: a versatile scaffold for translation initiation complexes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31(10):553–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valášek L, Mathew AA, Shin BS, Nielsen KH, Szamecz B, Hinnebusch AG. The yeast eIF3 subunits TIF32/a, NIP1/c, and eIF5 make critical connections with the 40S ribosome in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17(6):786–99. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC196014/ doi: 10.1101/gad.1065403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jivotovskaya AV, Valášek L, Hinnebusch AG, Nielsen KH. Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 (eIF3) and eIF2 Can Promote mRNA Binding to 40S Subunits Independently of eIF4G in Yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(4):1355–72. Available from: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1355-1372.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiu WL, Wagner S, Herrmannová A, Burela L, Zhang F, Saini AK, et al. The C-terminal region of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3a (eIF3a) promotes mRNA recruitment, scanning, and, together with eIF3j and the eIF3b RNA recognition motif, selection of AUG start codons. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(18):4415–34. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00280-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell SF, Walker SE, Algire MA, Park EH, Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR. The 5′-7-Methylguanosine Cap on Eukaryotic mRNAs Serves Both to Stimulate Canonical Translation Initiation and to Block an Alternative Pathway. Mol Cell. 2010;39(6):950–62. Available from: https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/abstract/S1097-2765(10)00631-3 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choudhuri A, Maitra U, Evans T. Translation initiation factor eIF3h targets specific transcripts to polysomes during embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(24):9818–23. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1302934110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisdom R, Johnson RS, Moore C. c-Jun regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. EMBO J. 1999;18(1):188–97. Available from: https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1093/emboj/18.1.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meng Q, Xia Y. c-Jun, at the crossroad of the signaling network. Protein Cell. 2011;2(11):889–98. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1113-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smeal T, Binetruy B, Mercola DA, Birrer M, Karin M. Oncogenic and transcriptional cooperation with Ha-Ras requires phosphorylation of c-Jun on serines 63 and 73. Nature. 1991;354(6353):494–6. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/354494a0 doi: 10.1038/354494a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bohmann D, Bos TJ, Admon A, Nishimura T, Vogt PK, Tjian R. Human proto-oncogene c-jun encodes a DNA binding protein with structural and functional properties of transcription factor AP-1. Science. 1987;238(4832):1386–92. doi: 10.1126/science.2825349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryder K, Lau LF, Nathans D. A gene activated by growth factors is related to the oncogene v-jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85(5):1487–91. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC279796/ doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blau L, Knirsh R, Ben-Dror I, Oren S, Kuphal S, Hau P, et al. Aberrant expression of c-Jun in glioblastoma by internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-mediated translational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(42):E2875–84. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1203659109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakamura T, Datta R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Regulation of jun and fos gene expression in human monocytes by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Cell Growth Differ Mol Biol J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1991;2(6):267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angel P, Hattori K, Smeal T, Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988;55(5):875–85. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0092867488901432 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamph WW, Wamsley P, Sassone-Corsi P, Verma IM. Induction of proto-oncogene JUN/AP-1 by serum and TPA. Nature. 1988;334(6183):629–31. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/334629a0 doi: 10.1038/334629a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suphakhong K, Terashima M, Wanna-udom S, Takatsuka R, Ishimura A, Takino T, et al. m6A RNA methylation regulates the transcription factors JUN and JUNB in TGF-β-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(11):102554. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9619186/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stanciu A, Luo J, Funes L, Galbokke Hewage S, Kulkarni SD, Aitken CE. eIF3 and Its mRNA-Entry-Channel Arm Contribute to the Recruitment of mRNAs With Long 5′-Untranslated Regions. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2021.787664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Antao VP, Lai SY, Tinoco I Jr. A thermodynamic study of unusually stable RNA and DNA hairpins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(21):5901–5. Available from: doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ivanov IP, Wei J, Caster SZ, Smith KM, Michel AM, Zhang Y, et al. Translation Initiation from Conserved Non-AUG Codons Provides Additional Layers of Regulation and Coding Capacity. mBio. 2017;8(3):10.1128/mbio.00844-17. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/mbio.00844-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44(2):283–92. Available from: https://www.cell.com/cell/abstract/0092-8674(86)90762-2 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schoch CL, Ciufo S, Domrachev M, Hotton CL, Kannan S, Khovanskaya R, et al. NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database. 2020;2020:baaa062. Available from: doi: 10.1093/database/baaa062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leppek K, Das R, Barna M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(3):158–74. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm.2017.103 doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang Y, Huang W, Tan L, Chen T, He Y, Irving PS, et al. Pervasive downstream RNA hairpins dynamically dictate start-codon selection. Nature. 2023;621(7978):423–30. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06500-y doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06500-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:407–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Starck SR, Tsai JC, Chen K, Shodiya M, Wang L, Yahiro K, et al. Translation from the 5′ untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response. Science. 2016;351(6272):aad3867. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aad3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chew GL, Pauli A, Schier AF. Conservation of uORF repressiveness and sequence features in mouse, human and zebrafish. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):11663. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms11663 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang H, Wang Y, Wu X, Tang X, Wu C, Lu J. Determinants of genome-wide distribution and evolution of uORFs in eukaryotes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1076. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21394-y doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21394-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith E, Meyerrose TE, Kohler T, Namdar-Attar M, Bab N, Lahat O, et al. Leaky ribosomal scanning in mammalian genomes: significance of histone H4 alternative translation in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(4):1298–308. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC552952/ doi: 10.1093/nar/gki248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matsuda D, Dreher TW. Close spacing of AUG initiation codons confers dicistronic character on a eukaryotic mRNA. RNA. 2006;12(7):1338–49. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1484435/ doi: 10.1261/rna.67906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giacomelli AO, Yang X, Lintner RE, McFarland JM, Duby M, Kim J, et al. Mutational processes shape the landscape of TP53 mutations in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2018;50(10):1381–7. Available from: https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC6168352 doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0204-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aleksashin N, Chang STL, Cate J. A highly efficient human cell-free translation system. RNA. 2023;rna.079825.123. Available from: http://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/early/2023/10/04/rna.079825.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–90. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC419797/ doi: 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(20):6097–100. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC332411/ doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sayers EW, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Karsch-Mizrachi I. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D94–9. Available from: 10.1093/nar/gky989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]