Abstract

Monitoring of bioinoculants once released into the field remains largely unexplored; thus, more information is required about their survival and interactions after root colonization. Therefore, specific primers were used to perform a long-term tracking to elucidate the effect of Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus on wheat and barley production at two experimental organic agriculture field stations. Three factors were evaluated: organic fertilizer application (with and without), row spacing (15 and 50 cm), and bacterial inoculation (H. diazotrophicus and control without bacteria). Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus was detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction on the roots (up to 5 × 105 copies g−1 dry weight) until advanced developmental stages under field conditions during two seasons, and mostly in one farm. Correlation analysis showed a significant effect of H. diazotrophicus copy numbers on the yield parameters straw yield (increase of 453 kg ha−1 in wheat compared to the mean) and crude grain protein concentration (increase of 0.30% in wheat and 0.80% in barley compared to the mean). Our findings showed an apparently constant presence of H. diazotrophicus on both wheat and barley roots until 273 and 119 days after seeding, respectively, and its addition and concentration in the roots are associated with higher yields in one crop.

Keywords: coating, detection, gum arabic, PGPR, qPCR, root colonization, seed inoculation, survival

Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus used for seed inoculation of winter wheat and spring barely was able to colonize crop roots and affect yield parameters in a field experiment.

Introduction

Since Kloepper and Schroth (1978) introduced the term plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs), a broad spectrum of research has focused on revealing the complexity of plant–microbial interactions and how they are able to induce beneficial effects on plant immunity, growth, and productivity (Kloepper 1981, Kirchhof et al. 1997, El Zemrany et al. 2006, Burns et al. 2015, Singh et al. 2022). PGPRs enhance plant performance through different mechanisms that have been widely reported over the years, such as nitrogen fixation (Hartmann et al. 1988), phosphorus solubilization (Wani et al. 2007), phytohormone production (Goswami et al. 2014), or triggering plant defense responses (Kloepper et al. 2004). These advances in PGPR research over the last decade have been linked to a paradigm shift toward sustainable agriculture (Singh et al. 2011, Backer et al. 2018). The current global attempt to reduce the use of mineral fertilizers and chemical pesticides has become an important issue, with special attention paid to most cultivated crops because of their environmental, economic, and social impacts (Thudi et al. 2021). The excessive use of mineral fertilizers contributes to not only the release of nitrous oxide (N2O) to the atmosphere but also soil erosion and nitrate (NO3−) leaching into groundwater. The latter has become a serious problem in Germany, reporting an excess of the maximum NO3− permissible value (50 mg l−1) in several groundwater-sampling sites in recent years (Sundermann et al. 2020).

Wheat and barley are among the six most produced cereals around the world, being fundamental in human nutrition, but at the same time, their cultivation may have a negative environmental impact due to the energy consumption for the production of fertilizers and pesticides, whose excessive use can lead to eutrophication and contaminated drinking water. Thus, several strategies have been considered to enhance yield from a sustainable perspective, including molecular breeding (Würschum et al. 2017), bioformulations (Yahya et al. 2022), or disease resistance (Skoppek et al. 2022). In this context, the use of PGPR has led to the release of several biofertilizers into the market. They aim to avoid soil degradation, reduce greenhouse emissions, and, at the same time, maintain soil fertility without reducing crop production (Aloo et al. 2022). However, PGPRs have to face and overcome many challenges. The effectiveness of PGPRs tested in vitro under field conditions is inconsistent (Cardinale et al. 2015, Owen et al. 2015), and in contrast to the laboratory or greenhouse, where several parameters, such as temperature, humidity, water availability, or light regime, are controlled, the field conditions vary depending on the season. Microorganisms that grow in gnotobiotic conditions have to adapt and survive in the new environment, compete with other microorganisms, and face different types of biotic and abiotic stresses (Backer et al. 2018). Understanding how these factors modulate and influence PGPR colonization is fundamental to extending the knowledge about plant–microbe interactions in situ as well as to improve the effectiveness of bioinoculants (Burns et al. 2015). However, there is scarce information regarding the tracking and monitoring of these inoculants once they are released in the field. In fact, < 25% of the studies used tracking methods, even though their development was not recent (for review, see Rilling et al. 2019). Among the different monitoring methods, the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is based on the design of specific primers that confer high accuracy, specificity, and reproducibility. In contrast to other methods for tracking PGPR, such as the use of reporter genes (beta-glucuronidase gene, green fluorescent protein) (Villegas and Paterno 2008, Krzyzanowska et al. 2012) or immunoassays (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) (Yegorenkova et al. 2010), which are semiquantitative, culture-dependent, or involve genetically modified bacteria, qPCR enables the quantitative analysis of nucleic acids used as templates. Most qPCR studies have been performed to detect Azospirillum spp. in roots (Faleiro et al. 2013, Stets et al. 2015, Coniglio et al. 2022) and bulk or rhizosphere soil (Bashan et al. 1995). Nevertheless, these studies were conducted under greenhouse conditions, considering short evaluation periods (mainly 14 days) and/or sterile/artificial environments that do not reflect field conditions. qPCR has been used to monitor the populations of various types of legume-nodulating rhizobia in the field (Maluk et al. 2022, 2023). Only a few long-term studies under field conditions have been performed to monitor the dynamics of PGPR in the rhizosphere soil (Zhang et al. 2020), roots (Soares et al. 2021, Urrea-Valencia et al. 2021), or stalks (Fernandes et al. 2014) of different plants, including maize, Brachiaria grasses, soybean, and sugarcane.

In this study, we inoculated the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus strain E19T on winter wheat (WW) (Triticum aestivum L., cv. Aristaro) and spring barley (SB) (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Odilia) seeds in order to evaluate its plant growth-promoting effects under field conditions. In addition, we developed specific primers to perform a long-term qPCR tracking of the bacterium at different stages in both plants, quantifying and correlating these results with the different yield parameters. Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, strictly aerobic bacterium, isolated from the rhizosphere of Plantago winteri (Suarez et al. 2014). Plant growth promoting (PGP) abilities in vitro and in vivo (greenhouse) have shown that H. diazotrophicus is able to fix nitrogen, solubilize insoluble phosphate, reduce stress through 1-amynocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase activity, and promote plant growth under salt stress conditions (Suarez et al. 2014, 2015). Previously, successful root colonization by H. diazotrophicus was identified using specific Fluorescence in-situ hybridisation (FISH) probes in barley grown under greenhouse conditions (Suarez et al. 2015, Rahman et al. 2018), indicating its accumulation on the root surface, except at the root tips.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

Field experiments were performed at the organic experimental stations Gladbacherhof (GH) (50°23′N, 8°15′E), Giessen University, central Germany, and Kleinhohenheim (KH) (48°44′N, 9°11′E), Hohenheim University, southwest Germany, during the seasons 2020–2021 (season I) and 2021–2022 (season II). The fields are located 185 and 444 m above sea level, with an average annual precipitation of 592 and 591 mm and an annual average temperature of 10.8 and 10.5°C, respectively (2020–2022). Both sites show Haplic Luvisol (IUSS Working Group WRB 2015) as soil type and have been organically managed since 1989 (GH) and 1994 (KH). The soil properties of both fields are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Additional soil properties have been described in detail by Elfadl et al. (2010), Chen et al. (2014), Schulz et al. (2014), and Binacchi et al. (2023). At Gladbacherhof, an 8-year crop rotation with 2-year alfalfa grass (Medicago sativa), winter rye (Secale cereale), potato (Solanum tuberosum), WW (T. aestivum), field beans (Vicia faba), spelt (T. aestivum ssp. spelta), and SB (H. vulgare) has been cultivated. Potato and spelt wheat were planted in the fields before seeding WW and SB, respectively. In contrast, a 5-year crop rotation at Kleinhohenheim with clover grass (Trifolium spp.), intensive vegetables, summer cereal, vegetables with low N-requirement, and emmer (T. dicoccum) was cultivated, with clover grass always planted before WW and SB.

Bacterial culture, seed coating, and field experiments

Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus strain E19T (LMG 27460T), from the culture collection of the Institute of Applied Microbiology (Justus Liebig University, Germany), was cultured in a half-concentrated marine bouillon (Carl Roth GmbH, Germany) and incubated on an orbital shaker at 27°C and 150 rpm for 48 h. Then, 2000 ml of the liquid culture was centrifuged at 17 700 × g for 20 min and re-suspended in 400 ml of 0.03 M MgSO4. The inoculation of H. diazotrophicus was based on and modified from the seed-coating technique described by Kloepper (1981). In our experiments, gum arabic 25% (Fisher Scientific, UK) and talc (Carl Roth GmbH, Germany) were autoclaved at 121.9°C for 25 min and pH adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.2 before coating. Subsequently, it was mixed with the bacterial re-suspension in a 1:1 ratio. Sterile MgSO4 solution was used as the control treatment. The gum inoculum (x̄ = 1.62 × 109 ± 4.89 × 108 bacteria ml−1) was gently placed and spread over WW (T. aestivum, cv. Aristaro) or SB (H. vulgare L., cv. Odilia) seeds, mixed well, and covered with talc (2.2 times the volume of the gum inoculum). The seeds were stored at 4°C until sowing. For colony-forming unit (CFU) determination, 0.1 g of the seed-coated powder was dissolved in 9.9 ml of 0.18% sodium pyrophosphate, followed by serial dilutions in 0.9 ml of NaCl (0.9%), obtaining an average concentration for both seasons of x̄ = 2.18 × 108 ± 9.56 × 107 CFU g−1 powder. A randomized complete block design with four replicates was performed under field conditions to evaluate the following factors: bacterial inoculation (strain E19T, ctrl without bacteria), row spacing (15 and 50 cm), and fertilization (with fertilizer, without fertilizer, only for WW). Approximately 400 seeds m−2 were sowed in plots of 7.5 m2 (5 m × 1.5 m). WW seeds were sowed between October and November 2020 (season I) and October 2021 (season II) and fertilized with organic manure in March 2021 (100.2 kg N ha−1, season I) and 2022 (107.1 kg N ha−1, season II) by the soil drenching method (Supplementary Table S2). SB seeds were sowed in April 2021 (season I) and March 2022 (season II). Fertilization of SB was not performed, as it is not common in organic farming.

Parallel greenhouse experiment to evaluate seed coating and strain E19T survival

Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus has previously proved to effectively colonize barley roots under salt stress conditions (Suarez et al. 2015). Therefore, in order to evaluate its root colonization abilities in WW, 700 g of soil from GH was milled, sieved (<4 mm), and placed in square plastic pots of 14 × 14 cm, containing 20 coated WW seeds used for seeding at GH during season I. In addition, we prepared pots with coated seeds with an initial concentration of 100 mM NaCl and then watered them three times with 50 mM NaCl, reaching a final concentration of 250 mM NaCl. All pots were maintained at 60% of their maximum water holding capacity (WHC = 239 ml). Coated seeds without bacterial inoculation (control samples) were also included in the experiments with and without salt stress, with three replicates per treatment.

Root sampling and DNA extraction

Field plants with soil at their roots were dug out from two different points in each plot (∼1 m into the plot from the edge) 120 days after seeding (DAS) (only at GH, season I), then at flowering (BBCH-60), milk ripe (BBCH-75, season I), and fully ripe (BBCH-89, season II) stages. Similarly, root samples from the greenhouse experiment were collected 10 DAS (BBCH-12) and 30 DAS (BBCH-30), considering the Zadoks growth scale (Zadoks et al. 1974). Thereafter, samples were collected in plastic bags and stored at 4°C. Once in the laboratory, the soil was discarded from the roots using sterilized forceps and scissors. Samples with seed inoculation were processed at separate locations compared to those without seed inoculation. Only the upper part of the roots was placed in sterile plastic centrifuge tubes of 15 ml and stored at −80°C. For the greenhouse experiment, the roots were cut immediately after removing the soil, and the lower, middle, and upper parts were frozen separately in sterile plastic centrifuge tubes at −80°C.

Prior to DNA extraction, the roots were rinsed two to three times with sterilized deionized water to remove the soil. They were then ground with liquid nitrogen using a sterilized mortar and pestle (180°C for 5 h). Approximately 100–200 mg of fresh root weight was placed into a 2-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge tube containing 700 mg of heat-sterilized zirconium beads (0.1 mm). For DNA extraction, 1 ml of extraction buffer (0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05 M EDTA, 25 g l−1 SDS, pH 8) was added to the tubes. Root tissue was disrupted with a homogenizer for 45 s at 5.5 m s−1 (Fastprep-24™, Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) and later centrifuged at 17 000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. RNA was digested by the addition of 2.5 µl RNAse (20 mg ml−1), followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. For DNA separation from lipids and cell debris, 1 ml of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added to the tubes, mixed by inversion, and centrifuged at 17 000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase from the tubes was recovered and transferred into a new 2 ml microcentrifuge tube. Subsequently, 1 ml of chloroform was pipetted into the tubes and centrifuged at 17 000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected in a new 2 ml microcentrifuge tube. DNA precipitation consisted of the addition of 1 ml of precipitation buffer (200 g l−1 polyethylene glycol 6000, 2.5 M NaCl), followed by incubation for 30 min at 4°C. The tubes were centrifuged at 17 000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatant was discarded by decanting. Finally, a washing step with 800 µl of ice-cold 75% ethanol was performed. The tubes were mixed by inversion and centrifuged at 17 000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. After ethanol removal, the DNA pellet was dried next to the Bunsen burner flame and dissolved in 30 µl of nuclease-free water.

Primer design

A specific primer pair (E19_F_932: 5′-GTCCGGCTATCCAGAGAGAT-3′; E19_R_1261: 5′-ATTAGCTGACCCTCGCAGGT-3′) targeting the 16S rRNA gene of strain E19T was designed by aligning the 16S rRNA gene of strain E19T and its closest relatives. The sequences were obtained from the SILVA database (Quast et al. 2012), aligned, and merged with the LTPs111 (February 2013) database (Munoz et al. 2011) using the ARB version 5.2 program (Ludwig et al. 2004). The specificity of the primer pair was checked using the online programs Probe Check (Loy et al. 2008) and SILVA TestPrime v1.0 (Klindworth et al. 2013). The specificity of the primers was also tested by cloning, using the method described by Kampmann et al. (2012a), with DNA isolated from the rhizosphere of different plants. The cloned DNA sequences from the vectors were sequenced (LGC, Berlin, Germany), and only sequences identical to the corresponding sequences of the strain E19T were found.

Quantitative PCR standard curve

The copy numbers of the standard 16S rRNA gene segments were calculated as described by Kampmann et al. (2012b). For qPCR, 5 µl of SYBR Green JumpStart™ Ready Mix (Sigma–Aldrich, USA), plus 0.2 µl of the primers 932F (10 µM) and 1261R (10 µM), 0.1 µl BSA (20 µg µl−1), 2 µl of PCR-water, and 2.5 µl of DNA were used for a total volume of 10 µl. The DNA for the standard curve was serially diluted 10-fold between the range in which H. diazotrophicus was detectable (from 6.88 × 105 copies µl−1 until 6.88 × 100 copies µl−1). Quantification of H. diazotrophicus in the samples was performed in four replicates with a Rotor Gene Q (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using the following program: 2 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 63°C, 45 s at 72°C, and 15 s at 84°C. Q-Rex software v1.1.04 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used for absolute quantification, normalization, and Cq calculation.

Harvesting, yields, and copy number g−1 DW

Harvesting of WW and SB took place in August in the years 2021 and 2022. Fresh and dry weights were determined from the seeds and straw and adjusted to 12% moisture for grain yield and straw yield calculations. In addition, the thousand-kernel weight was also included. To determine the crude protein concentration, the grain samples were dried and milled using a tube mill (MM301, Retsch, Haan, Germany). The DUMAS combustion method was used to determine the total N content in the individual flour samples using a Vario MACRO cube CHNS macro elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Finally, the N content was multiplied by a factor of 5.7 (Sosulski and Imafidon 1990).

The result of the qPCR in copies µl−1 was converted to copies g−1 DW soil using the following formula:

|

where C is the copies per dry weight sample (copies g−1 DW sample), Cr is the copies per qPCR reaction (copies µl−1), Vu is the dilution factor of the DNA in the qPCR (usually 1:10), Vt is the total volume of the DNA extract (30 µl), ms is the mass of the extracted environmental sample (g), and dm is the dry matter content of the extracted environmental sample (%).

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation of the copies g−1 DW was carried out using R studio software, v4.3.0 (R Core Team 2023). The qPCR data were log10 transformed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) were performed to compare significant differences between treatments. Eventually, data visualization was performed through R packages ggstatsplot v0.11.1 (Patil 2021), palmerpenguins v0.1.1 (Horst et al. 2020), and tidyverse v2.0 (Wickham et al. 2019).

A linear mixed-model approach was applied using the R package lme4 v1.1–26 (Bates et al. 2015). In order to assess the effect of seed inoculation with H. diazotrophicus, each crop was analyzed separately, and the factors bacterial inoculation (categorical variable and continuous variable as log10 copies g−1 DW sample), fertilizer management (for WW), and row spacing were assessed as fixed effects. On the other side, harvest season, field location, and experimental block were used as random effects for model creation. Initially, it was determined the level of variance explained by each one of the afore-mentioned factors. Subsequently, three models were created, as described by the following formulas:

Model 1:

|

|

Model 2:

|

|

Model 3:

|

|

where  is the yield or response of the ith plant with j bacterial inoculation, k fertilizer management, and l row spacing.

is the yield or response of the ith plant with j bacterial inoculation, k fertilizer management, and l row spacing.  is the overall fixed intercept,

is the overall fixed intercept,  is the intercept for bacterial inoculation,

is the intercept for bacterial inoculation,  is the intercept for fertilizer management, and

is the intercept for fertilizer management, and  is the intercept for row spacing.

is the intercept for row spacing.  corresponds to the intercept of the interaction between bacterial inoculation and fertilizer management.

corresponds to the intercept of the interaction between bacterial inoculation and fertilizer management.  is the intercept of the interaction between bacterial inoculation and row spacing.

is the intercept of the interaction between bacterial inoculation and row spacing.  corresponds to the intercept of the interaction between fertilizer management and row spacing.

corresponds to the intercept of the interaction between fertilizer management and row spacing.  is the intercept of the interaction of all fixed effects.

is the intercept of the interaction of all fixed effects.  is the intercept of hierarchical random effects for the ith plant,

is the intercept of hierarchical random effects for the ith plant,  and

and  are the random intercept and random bacterial inoculation slope effects for the ith plant, and e is the random error. With the typical assumption of mutual independence of random effects and random error and normally and identically distributed effects. Model 1 represented the dependent variable without fixed effects and with only random effects. Model 2 includes fixed effects but does not assume any interaction among them. Model 3 includes fixed effects, with the assumption of interaction among them.

are the random intercept and random bacterial inoculation slope effects for the ith plant, and e is the random error. With the typical assumption of mutual independence of random effects and random error and normally and identically distributed effects. Model 1 represented the dependent variable without fixed effects and with only random effects. Model 2 includes fixed effects but does not assume any interaction among them. Model 3 includes fixed effects, with the assumption of interaction among them.

Following, the models were compared using the function model.comparison from R package flexplot v0.19.1. (Fife 2022), using the Akiake information criterion, Bayesian information criterion, and Bayes factor as the criteria for model selection.

Later, the selected model was fitted using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and t-tests and Type III ANOVAs were performed by applying the Satterthwaite’s method for approximating the degrees of freedom for the t and F tests using the R package lmerTest v3.1–3 (Kuznetsova et al. 2017).

Results

Long-term qPCR detection of the strain E19T under field conditions at different developmental stages

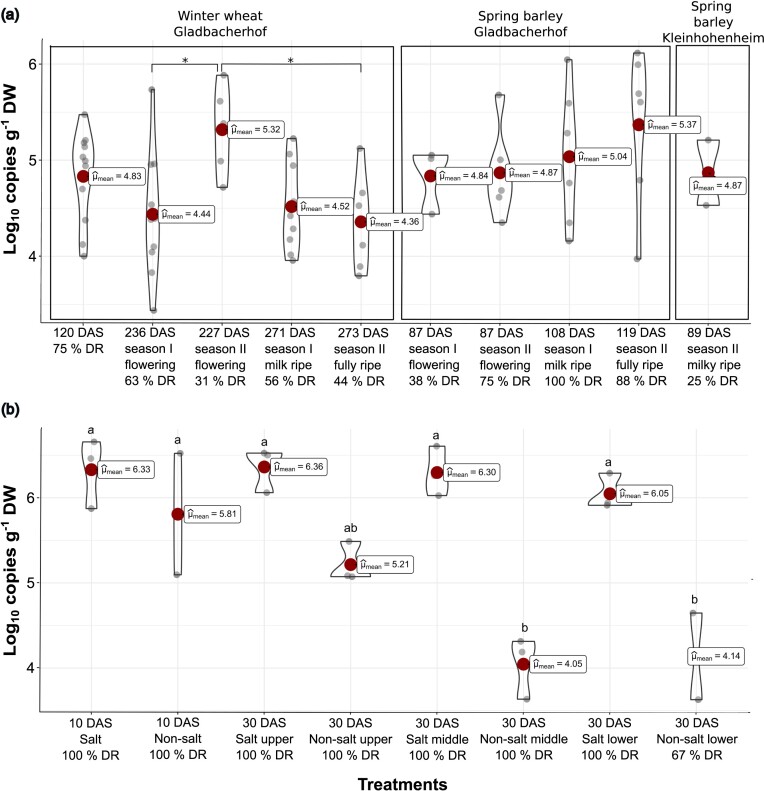

Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus was successfully detected in the roots of WW and SB during the two evaluated seasons, mostly at Gladbacherhof (Fig. 1a). As the E19T detection was not found in all the samples collected, treatments were clustered only by bacterial inoculation, and the detection rate was calculated to estimate which percentage of the root samples under field conditions were colonized by strain E19T. The highest copy number of H. diazotrophicus was observed during season II at the flowering stage for WW (x̄log10 copies = 5.32, x̄copies = 3.1 × 105 copies g−1 DW) and milk ripe for SB (x̄log10 copies = 5.37, x̄copies =5 × 105 copies g−1 DW). Although some significant differences between seasons or stages were found, no clear trend was observed in either plant species (Fig. 1a). Surprisingly, no significant reduction was observed in the number of copies in WW at 120 DAS (x̄ = 4.83, Fig. 1a) compared to the advanced developmental stages (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1a). However, the detection rate declined with the highest value recorded at 120 DAS (75%). Moreover, the strain E19T detected in samples at flowering was not necessarily found in the next stage, and vice versa. In contrast, the highest detection percentages in SB were observed at the milk/fully ripe stage (100% and 88% detection rates in seasons I and II, respectively). It is important to point out that in WW, strain E19T was detected after a longer period of time (up to 273 DAS, Fig. 1a) than in SB (up to 119 DAS, Fig. 1a). Furthermore, strain E19T was not detected in any of the control samples (roots of wheat and barley that were not seed-inoculated with E19T), showing the specificity of the primers and the non-native presence of H. diazotrophicus in the soil of both organic farms. As the number of copies g−1 DW was zero, they were not shown in Fig. 1. Intriguingly, in the other experimental field (Kleinhohenheim), strain E19T could not be detected during season I; it was only detected in two replicates of SB during season II (x̄ = 4.87, 25% detection rate, Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of the number of copies per gram of DW (log10) of strain E19T for wheat and barley during the two seasons under field conditions. Significance codes: < 0.05 '*'. Subsets for wheat (n = 5–12, Tukey’s HSD, α = 0.05) and barley (n = 3–8, ANOVA, α = 0.05) were used for statistical analysis. (b) Comparison of the number of copies per gram of DW (log10) of strain E19T for wheat under saline (salt) and non-saline conditions (non-salt). Different letters show significant differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD, α = 0.05). DR = detection rate (%); DAS = days after seeding; upper = upper section of the roots; middle = middle section of the roots; lower = lower section of the roots.

qPCR detection of the strain E19T under greenhouse conditions

In parallel to sowing WW to the field in season I and due to accessibility and better root examination, the same coated seeds were used for the detection of strain E19T in an early growth stage of the wheat plants in a greenhouse experiment. In addition to the optimal growth conditions for wheat, salt stress was applied to evaluate whether strain E19T could be detected under saline conditions in WW (Fig. 1b). Ten DAS, the copy number of strain E19T under salt stress (x̄ = 6.33) was higher than that of the strain E19T without salt stress (x̄ = 5.81). However, no significant differences were found between treatments (P = 0.78; Fig. 1b). Remarkably, the highest number of copies was detected in the upper part of the root under salt stress (x̄log10 copies = 6.36, x̄copies = 2.55 × 106 copies g−1 DW). Furthermore, no significant decrease over time was observed in the middle and lower root sections under this stress condition (Fig. 1b). This was in contrast with the results obtained without salt after 30 days, in which the concentration significantly decreased in the middle (x̄ = 4.05) and lower parts (x̄ = 4.14) of the roots but not in the upper part (x̄log10 copies = 5.21, x̄copies = 1.82 × 105 copies g−1 DW). The detection percentage was 100% in all treatments, except for the lower part of the roots after 30 days without salt stress (67%, Fig. 1b).

Influence on bacterial inoculation, fertilizer, and row spacing on plant parameters

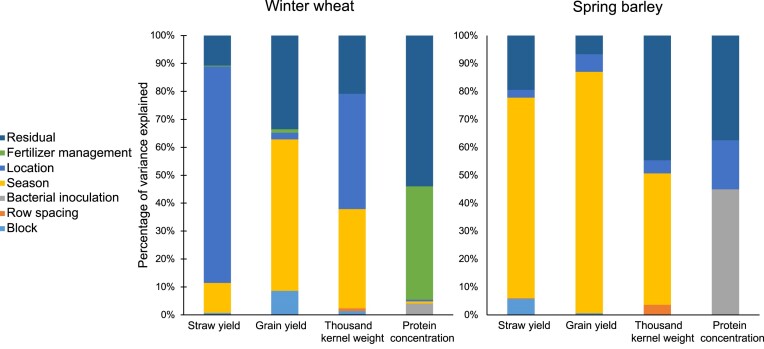

At first glance, yield parameters collected during the seasons 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 showed better performance in terms of grain yield, straw yield, and thousand-kernel weight in season II in both fields compared to the previous season, not being the case for crude protein concentration (Table 1). In fact, the linear mixed model revealed that most of the variation was determined not only by the season, but also by the location and the block (Fig. 2). The variance of these three factors varied depending on the yield parameters, with the season being the main source of variance in SB and the location the main source of variance in WW. Therefore, to control their contribution to the overall variance, season, location, and block were modeled as random effects for the linear mixed model.

Table 1.

Average and standard deviation of agronomic data for WW and SB at different locations during the seasons 2020–2021 and 2021–2022.

| Season | Plant | Location | Treatment | Grain yield (kg ha−1) | Straw yield (kg ha−1) | Thousand kernel weight (g) | Crude protein concentration (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020–2021 | WW | Gladbacherhof | Fertilizer | With | 4186 ± 331 | 8037± 1062 | 42.3 ± 1.3 | 13.6 ± 0.8 |

| Without | 3965 ± 367 | 7775± 749 | 42.4 ± 1.1 | 11.8 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Row spacing | 15 cm | 4136 ± 334 | 7693 ± 845 | 42.0 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 1.4 | |||

| 50 cm | 4014 ± 388 | 8120 ± 957 | 42.7 ± 1.1 | 12.8 ± 1.6 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 4105 ± 361 | 7583 ± 807 | 42.4 ± 1.2 | 12.1 ± 1.7 | |||

| E19 | 4045 ± 372 | 8230 ± 923 | 42.3 ± 1.2 | 13.2 ± 1.0 | ||||

| Kleinhohenheim | Row spacing | 15 cm | 3564 ± 1193 | 2552 ± 891 | 41.5 ± 2.2 | 9.8 ± 0.2 | ||

| 50 cm | 3552 ± 733 | 2554 ± 761 | 42.9 ± 1.4 | 9.7 ± 0.4 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 3263 ± 734 | 2737 ± 699 | 42 ± 2.4 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | |||

| E19 | 3809 ± 1055 | 2395 ± 877 | 42.4 ± 1.6 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | ||||

| SB | Gladbacherhof | Row spacing | 15 cm | 1414 ± 347 | 1050 ± 217 | 45.0 ± 0.5 | 11.8 ± 2.8 | |

| 50 cm | 1240 ± 644 | 939 ± 297 | 45.9 ± 1.0 | 12.8 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 1301 ± 417 | 1016 ± 249 | 45.5 ± 0.9 | 10.8 ± 1.5 | |||

| E19 | 1353 ± 614 | 972 ± 281 | 45.5 ± 0.9 | 13.8 ± 1.8 | ||||

| Kleinhohenheim | Row spacing | 15 cm | 1352 ± 125 | 2187 ± 382 | 45.3 ± 2.3 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | ||

| 50 cm | 1200 ± 146 | 1861 ± 391 | 44.9 ± 2.6 | 10.5 ± 0.7 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 1302 ± 178 | 2079 ± 334 | 45.2 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | |||

| E19 | 1250 ± 129 | 1969 ± 492 | 45 ± 3.2 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | ||||

| 2021–2022 | WW | Gladbacherhof | Fertilizer | With | 5212 ± 825 | 8865 ± 1324 | 49.5 ± 0.9 | 12.5 ± 1.1 |

| Without | 5061 ± 651 | 8883 ± 1154 | 49.3 ± 0.7 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | ||||

| Row spacing | 15 cm | 5310 ± 792 | 9135 ± 1231 | 49.2 ± 0.8 | 11.8 ± 1.4 | |||

| 50 cm | 4964 ± 653 | 8612 ± 1194 | 49.6 ± 0.9 | 12.1 ± 1.3 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 4997 ± 712 | 8735 ± 1273 | 49.2 ± 0.7 | 11.6 ± 1.5 | |||

| E19 | 5276 ± 754 | 9013 ± 1193 | 49.6 ± 0.9 | 12.3 ± 1.1 | ||||

| Kleinhohenheim | Fertilizer | With | 5045 ± 744 | 5323 ± 1018 | 42.8 ± 2.5 | 13.0 ± 0.4 | ||

| Without | 4913 ± 941 | 5187 ± 1340 | 41.2 ± 2.8 | 12.4 ± 0.9 | ||||

| Row spacing | 15 cm | 4690 ± 880 | 5556 ± 1374 | 41.5 ± 2.5 | 12.5 ± 0.8 | |||

| 50 cm | 5269 ± 703 | 4953 ± 871 | 42.5 ± 2.9 | 13.0 ± 0.6 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 5027 ± 920 | 5183 ± 1285 | 41.9 ± 2.9 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | |||

| E19 | 4931 ± 773 | 5326 ± 1086 | 42.1 ± 2.6 | 12.7 ± 0.8 | ||||

| SB | Gladbacherhof | Row spacing | 15 cm | 3832 ± 768 | 3597 ± 1249 | 48.7 ± 1.4 | 12.0 ± 1.3 | |

| 50 cm | 3692 ± 699 | 3599 ± 1209 | 49.4 ± 1.4 | 11.7 ± 1.3 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 3801 ± 783 | 3763 ± 1313 | 48.9 ± 1.6 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | |||

| E19 | 3723 ± 687 | 3433 ± 1111 | 49.2 ± 1.3 | 12.9 ± 0.5 | ||||

| Kleinhohenheim | Row spacing | 15 cm | 5794 ± 434 | 3659 ± 901 | 46.1 ± 2.3 | 11.3 ± 1.2 | ||

| 50 cm | 5576 ± 224 | 3229 ± 786 | 48.6 ± 2.8 | 11.3 ± 1.4 | ||||

| Bacterial inoculation | Ctrl | 5581 ± 386 | 3430 ± 1009 | 47.5 ± 2.4 | 10.3 ± 0.9 | |||

| E19 | 5790 ± 301 | 3458 ± 718 | 47.2 ± 3.3 | 12.3 ± 0.6 | ||||

Ctrl = control without bacteria, E19 = inoculation with H. diazotrophicus, 15 cm = row spacing of 15 cm, 50 cm = row spacing of 50 cm, and with = with fertilizer, without = without fertilizer.

Figure 2.

Percentage of variance of the different factors used for modeling the linear mixed model in WW and SB.

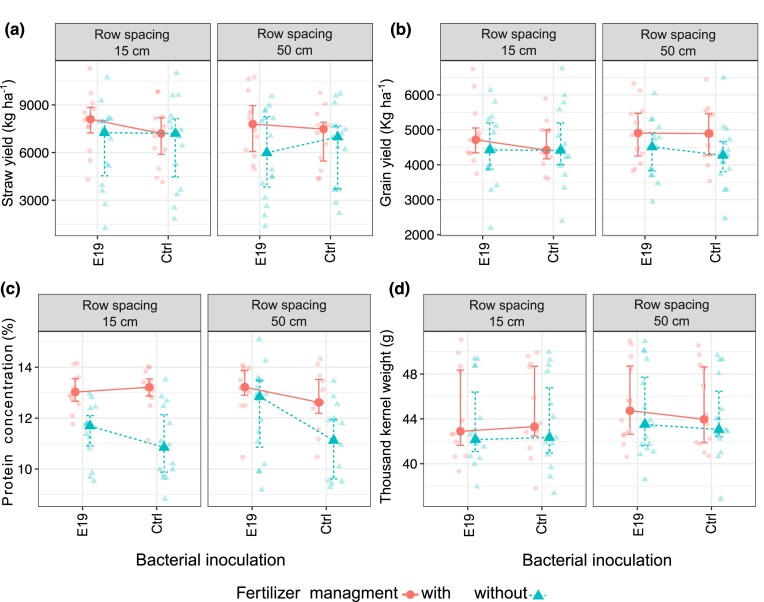

Type III ANOVA of the linear mixed models of WW showed a significant effect on straw yield, with only a significant interaction between bacterial inoculation and the addition of fertilizer (Table 2). Moreover, the t-test using Satterthwaite’s method showed that bacterial inoculation with strain E19T plus the addition of fertilizer significantly increased straw yield by 836 kg ha−1 compared to the mean (x̄ = 5915 kg ha−1, P = 0.045) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, in the absence of fertilizer, the bacterial inoculation could not perform properly, showing a significant decrease of 1080 kg ha−1 in straw yield compared to the mean (P = 0.048) (mostly caused by the absence of fertilizer, Fig. 3a). The grain yield results showed a similar trend to straw yield, but with non-significant results (Table 2, Fig. 3b). In addition, bacterial inoculation, fertilizer, and row spacing showed a significant effect on the thousand-kernel weight (fertilizer, row spacing, Table 2, Fig. 3d) and grain protein concentration (bacterial inoculation and fertilizer, Fig. 3c). The t-test using Satterthwaite’s method indicated that the absence of fertilizer significantly decreased by 0.5 g and 1.25% the thousand-kernel weight and protein concentration compared to their means (x̄ = 43.9 g, P = 0.017; x̄ = 12.34%, P = 3.41 × 10−8, respectively). Remarkably, bacterial inoculation significantly increased the protein concentration (Fig. 3c) of WW by 0.56% compared to the mean (x̄ = 12.34%, P = 5.80 × 10−8).

Table 2.

Type III ANOVA with Satterthwaite’s method based on linear mixed models of different yield parameters for WW and SB.

| Plant | Yield parameter | Factor | Bacterial inoculation | Fertilizer | Row spacing | Bacterial inoculation: fertilizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW | Straw yield | F value | 2.12 | 0.78 | 1.19 | 7.36 |

| Pr(>F) | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 8.08 × 10−3** | ||

| Grain yield | F value | 0.74 | 3.94 | 0.28 | 0.87 | |

| Pr(>F) | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.6 | 0.36 | ||

| Thousand kernel weight | F value | 0.74 | 6.13 | 14.44 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 0.39 | 1.51 × 10−2* | 2.58 × 10−4*** | - | ||

| Crude protein concentration | F value | 8.15 | 37.43 | - | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 5.40 × 10−3** | 2.08 × 10−8*** | - | - | ||

| SB | Straw yield | F value | 0.70 | - | 2.67 | - |

| Pr(>F) | 0.41 | - | 0.11 | - | ||

| Grain yield | F value | 0.14 | - | 4.03 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 0.71 | - | 0.05 | - | ||

| Crude protein concentration | F value | 39.07 | - | 0.37 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 5.92 × 10−8*** | - | 0.54 | - |

Empty spaces belong to factors that were not included for the linear mixed model. Numbers in bold indicate significant differences. Significance codes: “***”<0.001, “**”<0.01, “*”<0.05.

Figure 3.

Linear mixed models fit by REML for WW (a) straw yield, (b) grain yield, (c) protein concentration, and (d) thousand kernel weight.

Non-significant effect of the factors row spacing and bacterial inoculation was found in SB for the straw yield, grain yield, and thousand-kernel weight (reduced linear model with no interaction between the fixed effects, Table 2). Nevertheless, the analysis of protein concentration revealed that bacterial inoculation significantly increased its concentration by 1.80% compared to the mean (x̄ = 10.51%, P = 1.19 × 10−7, Supplementary Fig. S1b).

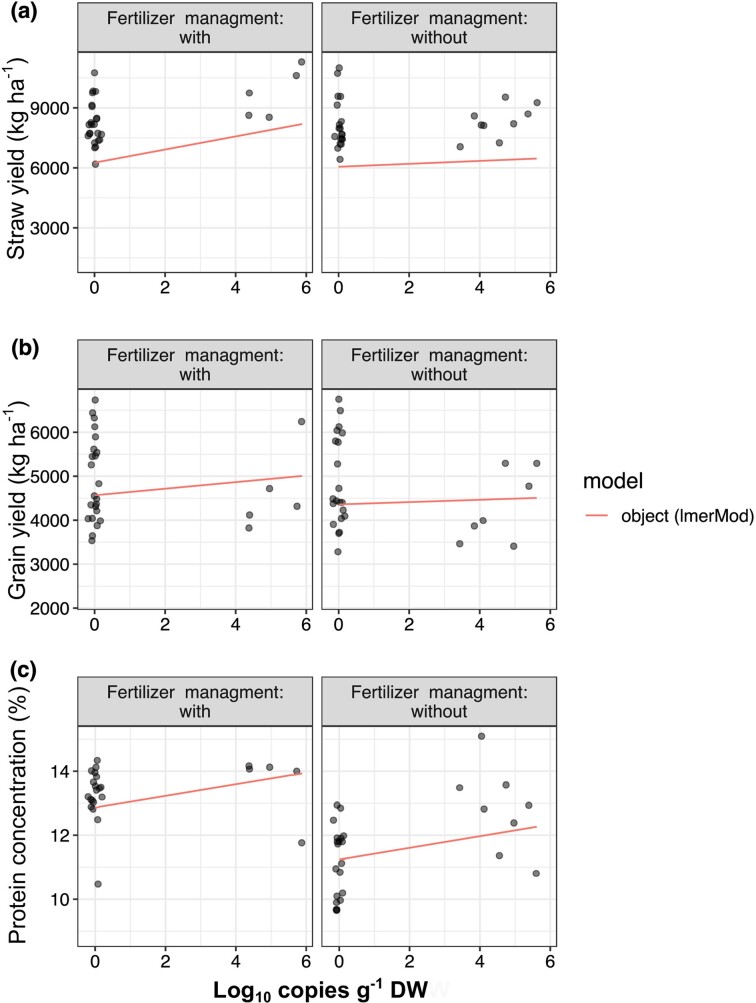

Similarly, mixed linear models were applied to correlate the copies g−1 DW of strain E19T obtained from qPCR with the different yield parameters. The flowering stage was the best indicator compared to the ripening stages for assessing the correlation between the concentration of H. diazotrophicus and crop yield parameters (Supplementary Table S3). Strain E19T copies g−1 DW showed the same significant effect on the straw yield of WW (Table 3), with an increment of 453 kg ha−1 (Fig. 4a) compared to the mean (x̄ = 6486 kg ha−1, P = 0.032, t-test using Satterthwaite’s method) and the same non-significant tendency for grain yield (Fig. 4b). Remarkably, in both WW and SB, the crude protein concentration clearly showed the effect of fertilizer application (only WW) and the number of copies g−1 DW of strain E19T, indicating that higher copies g−1 DW of strain E19T or fertilizer application were positively correlated with higher protein concentrations (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, higher concentrations of H. diazotrophicus detected in the soil were positively correlated with a significant increase of 0.30% and 0.80% in protein concentration compared to the mean of WW (x̄ = 12.96%, P = 0.0058, Fig. 4c) and SB (x̄ = 11.45%, P = 2 × 10−16, Supplementary Fig. S1a).

Table 3.

Type III ANOVA with Satterthwaite’s method based on linear mixed models of different yield parameters compared to the number of copies g−1 DW (log) of strain E19T for WW and SB.

| Plant | Yield parameter | Factor | Log copies E19 | Fertilizer | Row spacing | Log copies E19: fertilizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW | Straw yield | F value | 9.97 | 3.25 | 0.76 | 4.55 |

| Pr(>F) | 2.15 × 10−3** | 0.08 | 0.39 | 3.56 × 10−2* | ||

| Grain yield | F value | 1.73 | 4.76 | 0.21 | 0.23 | |

| Pr(>F) | 0.19 | 3.29 × 10−2* | 0.65 | 0.63 | ||

| Crude protein concentration | F value | 8.46 | 31.98 | 1.57 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 4.50 × 10−3** | 2.00 × 10−4*** | 0.21 | - | ||

| SB | Straw yield | F value | 0.87 | - | 2.42 | - |

| Pr(>F) | 0.35 | - | 0.13 | - | ||

| Grain yield | F value | 4.94 | - | 3.82 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 3.09 × 10−2* | - | 0.06 | - | ||

| Crude protein concentration | F value | 24.74 | - | 0.06 | - | |

| Pr(>F) | 5.34 × 10−6*** | - | 0.81 | - |

Empty spaces belong to factors that were not included for the linear mixed model. Numbers in bold indicate significant differences. Significance codes: “***”<0.001, “**”<0.01, “*”<0.05.

Figure 4.

Linear mixed models fit by REML considering the log copies g−1 DW of strain E19T for WW (a) straw yield, (b) grain yield, and (c) crude protein concentration.

Surprisingly, in the case of SB, the number of copies g−1 DW of strain E19T was negatively correlated with grain yield (Table 3). The t-test using Satterthwaite’s method indicated that by each increment in a unit of log copies g−1 DW, there was a significant decreased in the grain yield of SB by 171 kg ha−1 compared to the mean (x̄ = 3088 kg ha−1, P = 0.025). Nevertheless, it is important to note that rather low SB yields were obtained during the season 2020–2021 (<1500 kg ha−1, Table 1) due to weather conditions that caused fungal infection, affecting plant yield parameters and probably contributing to the negative effect observed by bacterial inoculation.

Discussion

In the last decade, bioinoculants have gained significant importance as a sustainable agricultural strategy. However, the lack of information on plant microbial interactions coupled with the reported inconsistency of their efficacy under agronomic conditions, as well as their persistence once released into the soil, is a current claim to be unveiled (for review, see Owen et al. 2015, Thilakarathna and Raizada 2017, Salomon et al. 2022). In this study, we developed specific primers to monitor the plant growth-promoting bacterium H. diazotrophicus, focusing on three important aspects: (i) bacterial root colonization after seed coating; (ii) early and long-term persistence and quantification of H. diazotrophicus under field experimental conditions; and (iii) the correlation between the number of copies g−1 DW of H. diazotrophicus, as well as the different factors evaluated with certain yield parameters of WW and SB.

We determined successful root colonization of H. diazotrophicus through qPCR at the greenhouse level, simulating field conditions (GH soil and coated seeds) for WW seeds. The bacterium was detected 10 DAS in 100% of the samples analyzed at a high concentration (Fig. 1b), indicating on one side the seed coating effectiveness technique and on the other side the root colonization ability of H. diazotrophicus, not only for barley but also for wheat. In the E19T genome, several genes have been related to rhizosphere/root colonization, such as those involved in quorum sensing (aiiA, lux, rhtB), chemotaxis (che, tsr), motility (flg, fli), secretory protein systems (tat, sec), and antibiotic resistance (acr, emr), which were described in the detailed gene list of Suarez et al. (2019) in their Supplementary Tables S12 and S15. Earlier, other groups, e.g. Compant et al. (2010) and Schikora et al. (2016), pointed out that the above-mentioned bacterial traits of PGPR are important for root colonization. Furthermore, in a recent metatranscriptomic study by Vannier et al. (2023), several genes have been associated with root colonization success of PGPR. All these genes are also present in the genome of E19T, like the PstABCS operon, which encodes the phosphate starvation system (Pst) and promotes phosphate assimilation of E19T. Similarly, the iron import gene exBD and the general stress response gene typA, which are important for root colonization (Vannier et al. 2023), were also present in the E19T genome.

In agreement with the results for barley seeds obtained by Suarez et al. (2015), salt stress proved to play a fundamental role in the performance and persistence of strain E19T on the roots of WW (x̄log10 copies = 6.33, Fig. 1b). To this point of evaluation, our results were in agreement with similar results obtained at a greenhouse level by qPCR in wheat roots (Stets et al. 2015) or maize roots (Couillerot et al. 2010, Faleiro et al. 2013) observed up to 18 days after inoculation with Azospirillum spp. Nevertheless, as time progressed, we observed at 30 DAS a significant decrease in the number of copies g−1 DW in the middle (x̄log10 copies = 4.05) and lower parts (x̄log10 copies = 4.14), but not in the upper part (x̄log10 copies = 5.21, Fig. 1b) of the WW root samples without salt stress, indicating that although the bacterium could be detected in all root sections, its survival began to decline (Fig. 1b). Xiang et al. (2010) propose three possible scenarios for introduced bacteria: a long-term persistence, a sharp decline some days/weeks after inoculation, or a gradual decrease of bacterial population. Based on our results, we observed that H. diazotrophicus was able to colonize the roots at an early stage (greenhouse results), gradually decrease its cell number, and stabilize over time (detected in advanced developmental stages), but not in 100% of the plants (Fig. 1a), showing lower detection percentages in WW (31%–63%, probably due to time lapse and hard climate conditions) and higher percentages in SB according to the results of field experiments (up to 100%). When an exogenous microorganism is introduced into a new habitat, it has to find or compete with native microorganisms for a niche that could be already occupied (niche overlapping), but it could also lead to dynamic character displacement, resulting in either competitive exclusion or coexistence with indigenous microorganisms (Hemmerle et al. 2022). Moreover, according to the “kill the winner” hypothesis (Thingstad 2000), resident viruses are able to maintain equilibrium and coexistence between bacterial communities, attacking the highly abundant microbial populations, especially when foreign bacteria are introduced (Russ et al. 2023). Bioinoculants usually contain highly concentrated inocula and mechanisms to ensure root colonization (Rocha et al. 2019), as previously described for E19T.

Monitoring of bioinoculants under field conditions has increased in the last few years, revealing the dynamics of introduced microorganisms (Zhang et al. 2020, Urrea-Valencia et al. 2021). Soares et al. (2021) found differences between Brachiaria cultivars after inoculation with Azospirillum baldaniorum. In our study, the location was a determinant of H. diazotrophicus detection. We cannot clearly explain its unsuccessful detection at KH during season I and only in very few samples in season II (Fig. 1a). Therefore, seed transportation, interference during DNA extraction, or qPCR must be reconsidered. Nevertheless, we speculate that, although the soils of both organic farms share the same type (Haplic Luvisol) and similar soil properties (Supplementary Table S1), the native soil microbial communities could be different and play a pivotal role in the survival of H. diazotrophicus (Thingstad 2000, Hemmerle et al. 2022).

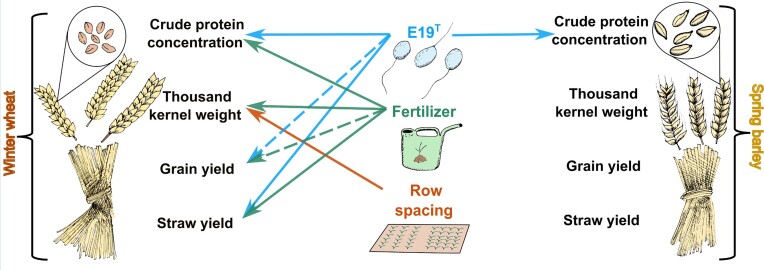

An illustrative summary of the correlation results is presented in Fig. 5. The addition of fertilizer to WW significantly improved the performance of H. diazotrophicus in terms of straw yield (836 kg ha−1 compared to the mean). This correlation was also observed with the copy number g−1 DW (453 kg ha−1). Previous crop fertilization (e.g. potato at GH) combined with the low fertilizer level applied (<110 kg N ha−1) could have contributed to the non-significant differences obtained in grain yield. The combination of PGPR and fertilizer could be related to better crop yield performance (Urrea-Valencia et al. 2021). Shaharoona et al. (2008) obtained similar results for wheat with the inoculation of Pseudomonas fluorescens and low levels of fertilizer, arguing that ACC deaminase producers (like H. diazotrophicus) reduced the inhibitory effect of the ethylene secreted in the roots at low nutrient levels, showing better growth and yield.

Figure 5.

Illustrative representation of the different correlations obtained from linear mixed model analysis of WW and SB. Solid lines represent a significant effect of the factor evaluated. Dashed lines show non-significant interactions but a positive trend with the factors.

Remarkably, H. diazotrophicus significantly increased the grain raw protein concentration in both crops (0.56% and 1.80% for wheat and barley, respectively, compared to the mean; Fig. 3c and Table 2), correlating higher number of copies g−1 DW with higher protein concentrations (0.30% and 0.80% for wheat and barley; Fig. 4c and Table 3). This increase could be indirectly related to the nitrogen fixation activity reported for H. diazotrophicus (Suarez et al. 2014) and the 14 nif genes and fixation-related genes identified in its genome (Suarez et al. 2019). Nevertheless, our approach will be corroborated by further experiments, such as the use of 15N isotope techniques that have been used to determine the nitrogen fixation activity of other diazotrophs (Urquiago et al 2012). In general, higher wheat grain protein concentrations, especially in the conditions of organic agriculture, are required to improve baking quality; however, relevant grain protein subunits should also be considered (Rekowski et al. 2020). In contrast, for a beer brewery, the barley protein concentration needs to be <11% in order to favor carbohydrate levels and reduce off-flavors (Díaz et al. 2022). In this context, inoculation with H. diazotrophicus is not recommended for the production of barley for brewery purposes, but for animal feed. Nevertheless, further research is required to confirm this finding. The lack of consistent positive effects of strain E19T on the other yield parameters of SB was hidden by the susceptibility of the cultivar Odilia to fungal infections (Federal Plant Variety Office 2021) and subsequently low yields. Strain E19T possesses genes that encode for phenazine biosynthesis and γ-aminobutyric acid (biocontrol agents) (Suarez et al. 2019). However, a threshold in the density of bioinoculants is required to show an effective response against phytopathogens (Raaijmakers et al. 1995). Similarly, the success of PGPR in controlling fungal infections is usually limited to low fungal density (Siddiqui and Shaukat 2002), which requires good fungal monitoring under field conditions. Future experiments shall explore the biocontrol potential, particularly because the genome of strain E19T contains a quorum quenching system with a gene for N-acetyl-homoserine lactone degradation. This system has the potential to influence both pathogen infection and defense mechanisms.

Conclusion

In summary, the development of specific primers to track H. diazotrophicus strain E19T has undoubtedly demonstrated its root colonization ability at early developmental stages, not only in barley as shown in previous research, but also in wheat, indicating its adaptability to colonize different plant species. We successfully detected the strain E19T through qPCR from the greenhouse level (30 DAS) until advanced developmental stages (milk/fully ripe) under field conditions. Although high concentrations and detection rates of strain E19T, with or without salt stress, were observed until 30 DAS, once beyond the greenhouse the detection rate was reduced. It gradually decreased but could be detected until advanced developmental stages, which suggests possible bacterial stabilization in the roots over time. These results also suggest that successful root colonization in the early stages does not directly imply high survival rates in later growth stages. Furthermore, the effect of exogenous bacterial inoculation on the native microbial soil communities needs to be evaluated in addition to interactions among each other, which help to elucidate the survival of strain E19T. Finally, WW straw yield and grain protein concentration were significantly enhanced by inoculation with H. diazotrophicus and addition of organic fertilizer. Furthermore, H. diazotrophicus favored an increase in the SB crude protein concentration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We warmly acknowledged to Rita Geissler-Plaum and Bellinda Schneider for their technical support. We are also grateful to Simon Schäfer for his support during field experiments at Kleinhohenheim. We acknowledge Elnaz Salehi-Mobarakeh for her help with qPCRs and Arizbeth Sevilla for her help with the illustration. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Santiago Quiroga, Institute of Applied Microbiology, IFZ, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany.

David Rosado-Porto, Institute of Applied Microbiology, IFZ, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany; Faculty of Basic and Biomedical Sciences, Simón Bolívar University, 080002 Barranquilla, Colombia.

Stefan Ratering, Institute of Applied Microbiology, IFZ, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany.

Azin Rekowski, Institute of Crop Science, Quality of Plant Products, 340e, University of Hohenheim, 70593 Stuttgart, Germany.

Franz Schulz, Department of Agronomy and Plant Breeding II, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35394 Giessen, Germany.

Marina Krutych, Institute of Applied Microbiology, IFZ, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany.

Christian Zörb, Institute of Crop Science, Quality of Plant Products, 340e, University of Hohenheim, 70593 Stuttgart, Germany.

Sylvia Schnell, Institute of Applied Microbiology, IFZ, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany.

Author contributions

Santiago Quiroga (Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft), David Rosado-Porto (Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft), Stefan Ratering (Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing), Azin Rekowski (Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft), Franz Schulz (Investigation), Marina Krutych (Investigation), Christian Zörb (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing), and Sylvia Schnell (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was fully funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) of Germany under the BONARES program (Rhizo4bio) BreadAndBeer 031B0906A and 031B0906B.

Data Availability

Yield parameters and qPCR data are available at the BONARES repository under the name “Production of wheat and barley under reduced input in organic farming.”

References

- Aloo BN, Tripathi V, Makumba BA et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial biofertilizers for crop production: the past, present, and future. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer R, Rokem JS, Ilangumaran G et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front Plant Sci. 2018;871:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y, Puente ME, Rodriguez-Mendoza MN et al. Survival of Azospirillum brasilense in the bulk soil and rhizosphere of 23 soil types. Appl Environ Microbial. 1995;61:1938–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Soft. 2015;67:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Binacchi F, Niether W, Brock C et al. Demystifying the agronomic and environmental N performance of grain legumes across contrasting soil textures of central Germany. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2023;356:108645. [Google Scholar]

- Burns JH, Anacker BL, Strauss SY et al. Soil microbial community variation correlates most strongly with plant species identity, followed by soil chemistry, spatial location and plant genus. AoB Plants. 2015;7:plv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale M, Ratering S, Suarez C et al. Paradox of plant growth promotion potential of rhizobacteria and their actual promotion effect on growth of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under salt stress. Microbiol Res. 2015;181:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Fan M, Kuzyakov Y et al. Comparison of net ecosystem CO2 exchange in cropland and grassland with an automated closed chamber system. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 2014;98:113–24. [Google Scholar]

- Compant S, Clément C, Sessitsch A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:669–78. [Google Scholar]

- Coniglio A, Larama G, Molina R et al. Modulation of maize rhizosphere microbiota composition by inoculation with Azospirillum argentinense Az39 (formerly A. brasilense Az39). J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22:3553–67. [Google Scholar]

- Couillerot O, Bouffaud ML, Baudoin E et al. Development of a real-time PCR method to quantify the PGPR strain Azospirillum lipoferum CRT1 on maize seedlings. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:2298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz AB, Durán-Guerrero E, Lasanta C et al. From the raw materials to the bottled product: influence of the entire production process on the organoleptic profile of industrial beers. Foods. 2022;11:3215. 10.3390/foods11203215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Zemrany H, Cortet J, Peter Lutz M et al. Field survival of the phytostimulator Azospirillum lipoferum CRT1 and functional impact on maize crop, biodegradation of crop residues, and soil faunal indicators in a context of decreasing nitrogen fertilisation. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:1712–26. [Google Scholar]

- Elfadl E, Reinbrecht C, Claupein W. Evaluation of phenotypic variation in a worldwide germplasm collection of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) grown under organic farming conditions in Germany. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2010;57:155–70. [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro AC, Pereira TP, Espindula E et al. Real time PCR detection targeting nifA gene of plant growth promoting bacteria Azospirillum brasilense strain FP2 in maize roots. Symbiosis. 2013;61:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes P, Simões-Arajo J, Varial de Melo L et al. Development of a real-time PCR assay for the detection and quantification of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus in sugarcane grown under field conditions. African J Microbiol Res. 2014;8:2937–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fife D. Flexplot: graphically-based data analysis.Psychol Methods. 2022;27:477–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D, Pithwa S, Dhandhukia P et al. Delineating Kocuria turfanensis 2M4 as a credible PGPR: a novel IAA-producing bacteria isolated from saline desert. J Plant Interact. 2014;9:566–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A, Fu HA, Burris RH. Influence of amino acids on nitrogen fixation ability and growth of azospirillum spp. Appl Environ Microb. 1988;54:87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerle L, Maier BA, Bortfeld-Miller M et al. Dynamic character displacement among a pair of bacterial phyllosphere commensals in situ. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2836. 10.1038/s41467-022-30469-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst A, Hill A, Gorman K. Palmerpenguins: palmer archipelago (antarctica) penguin data. R package version 0.1.0. 2020. 10.5281/zenodo.3960218 (23 February 2024, date last accessed). [DOI]

- IUSS Working Group WRB . World reference base for soil resources 2014, update 2015 international soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps.World Soil Resources Reports No 106 FAO, Rome. 2015. https://www.fao.org/3/i3794en/I3794en.pdf (13 February 2024, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann K, Ratering S, Baumann R et al. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens dominate in biogas reactors fed with defined substrates. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2012;35:404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann K, Ratering S, Kramer I et al. Unexpected stability of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes communities in laboratory biogas reactors fed with different defined substrates. Appl Environ Microb. 2012;78:2106–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhof G, Schloter M, Abmus B et al. Molecular microbial ecology approaches applied to diazotrophs associated with nonlegumes. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:853–62. [Google Scholar]

- Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper J, Schroth M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on radishes. IV international conference on plant pathogenic bacteria article. Proceedings of the 4th international conference on plant pathogenic bacteria, Angers, France. 1978;2:879–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper JW, Ryu CM, Zhang S. Induced systemic resistance and promotion of plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology. 2004;94:1259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper JW. Development of a powder formulation of rhizobacteria for inoculation of potato seed pieces. Phytopathology. 1981;71:590. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzanowska D, Obuchowski M, Bikowski M et al. Colonization of potato rhizosphere by GFP-tagged Bacillus subtilis MB73/2, Pseudomonas sp. P482 and ochrobactrum sp. A44 shown on large sections of roots using enrichment sample preparation and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Sensors. 2012;12:17608–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest Package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Soft. 2017;82:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Loy A, Arnold R, Tischler P et al. ProbeCheck—a central resource for evaluating oligonucleotide probe coverage and specificity. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2894–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluk M, Ferrando-Molina F, Lopez del Egido L et al. Fields with no recent legume cultivation have sufficient nitrogen-fixing rhizobia for crops of faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Plant Soil. 2022;472:345–68. [Google Scholar]

- Maluk M, Giles M, Wardell GE et al. Biological nitrogen fixation by soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.), a novel, high protein crop in Scotland, requires inoculation with non-native bradyrhizobia. Front Agron. 2023;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz R, Yarza P, Ludwig W et al. Release LTPs104 of the all-species living tree. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34:169–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office FPV. Descriptive list of varieties: cereals, maize, oil and forage plants, legumes, beet, cover crops. 2021;100–62. https://www.bundessortenamt.de/bsa/en/variety-testing/descriptive-variety-lists/downloading-descriptive-variety-lists (23 February 2024, date last accessed).

- Owen D, Williams AP, Griffith GW et al. Use of commercial bio-inoculants to increase agricultural production through improved phosphrous acquisition. Appl Soil Ecol. 2015;86:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Patil I. Visualizations with statistical details: the “ggstatsplot” approach. JOSS. 2021;6:3167. [Google Scholar]

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D590–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing,2023. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, Leeman M, Van Oorschot MM et al. Dose-response relationships in biological control of fusarium wilt of radish by Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology. 1995;85:1075–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Flory E, Koyro HW et al. Consistent associations with beneficial bacteria in the seed endosphere of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Syst Appl Microbiol. 2018;41:386–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekowski A, Wimmer MA, Hitzmann B et al. Application of urease inhibitor improves protein composition and bread-baking quality of urea fertilized winter wheat. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2020;183:260–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rilling JI, Acuña JJ, Nannipieri P et al. Current opinion and perspectives on the methods for tracking and monitoring plant growth‒promoting bacteria. Soil Biol Biochem. 2019;130:205–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha I, Ma Y, Souza-Alonso P et al. Seed coating: a tool for delivering beneficial microbes to agricultural crops. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10: 1357. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ D, Fitzpatrick CR, Teixeira PJPL et al. Deep discovery informs difficult deployment in plant microbiome science. Cell. 2023;186:4496–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon MJ, Demarmels R, Watts-Williams SJ et al. Global evaluation of commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculants under greenhouse and field conditions. Appl Soil Ecol. 2022;169: 104225. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schikora A, Schenk ST, Hartmann A. Beneficial effects of bacteria-plant communication based on quorum sensing molecules of the N-acyl homoserine lactone group. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;90:605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz F, Brock C, Schmidt H et al. Development of soil organic matter stocks under different farm types and tillage systems in the organic arable farming experiment Gladbacherhof. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2014;60:313–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shaharoona B, Naveed M, Arshad M et al. Fertilizer-dependent efficiency of Pseudomonas for improving growth, yield, and nutrient use efficiency of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;79:147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui IA, Shaukat SS. Resistance against the damping-off fungus rhizoctonia solani systemically induced by the plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa (IE-6S+) and P. fluorescens (CHA0). J Phytopathol. 2002;150:500–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh JS, Pandey VC, Singh DP. Efficient soil microorganisms: a new dimension for sustainable agriculture and environmental development. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2011;140:339–53. [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Chandra R, Purchase D. Unraveling the secrets of rhizobacteria signaling in rhizosphere. Rhizosphere. 2022;21:100484. [Google Scholar]

- Skoppek CI, Punt W, Heinrichs M et al. The barley HvSTP13GR mutant triggers resistance against biotrophic fungi. Mol Plant Pathol. 2022;23:278–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares IC, Pacheco RS, da Silva CGN et al. Real-time PCR method to quantify Sp245 strain of Azospirillum baldaniorum on Brachiaria grasses under field conditions. Plant Soil. 2021;468:525–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sosulski FW, Imafidon GI. Amino acid composition and nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors for animal and plant foods. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:1351–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stets MI, Campbell Alqueres SM, Souza EM et al. Quantification of Azospirillum brasilense FP2 bacteria in wheat roots by strain-specific quantitative PCR. Appl Environ Microb. 2015;81:6700–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez C, Cardinale M, Ratering S et al. Plant growth-promoting effects of Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus on summer barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under salt stress. Appl Soil Ecol. 2015;95:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez C, Ratering S, Geissler-Plaum R et al. Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus gen. nov., sp. nov., a phosphate-solubilizing and nitrogen-fixing alphaproteobacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of a natural salt-meadow plant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:3160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez C, Ratering S, Hain T et al. Complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Hartmannibacter diazotrophicus strain E19T. Int J Genomics. 2019;2019:1–12. 10.1155/2019/7586430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann G, Wägner N, Cullmann A et al. Nitrate pollution of groundwater long exceeding trigger value: fertilization practices require more transparency and oversight. DIW Weekly Report, ISSN 2568-7697, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 10, Iss. 8/9. 2020, pp. 61–72. https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.741058.de/publikationen/weekly_reports/2020_08_1/nitrate_pollution_of_groundwater_long_excceding_trigger_valu_tilization_practices_require_more_transparenca_and_oversight.html (23 February 2024, date last accessed).

- Thilakarathna MS, Raizada MN. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of diverse rhizobia inoculants on soybean traits under field conditions. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;105:177–96. [Google Scholar]

- Thingstad TF. Elements of a theory for the mechanisms controlling abundance, diversity, and biogeochemical role of lytic bacterial viruses in aquatic systems. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45:1320–8. [Google Scholar]

- Thudi M, Palakurthi R, Schnable JC et al. Genomic resources in plant breeding for sustainable agriculture. J Plant Physiol. 2021;257:153351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquiaga S, Xavier RP, de Morais RF et al. Evidence from field nitrogen balance and 15N natural abundance data for the contribution of biological N2 fixation to Brazilian sugarcane varieties. Plant Soil. 2012;356:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Urrea-Valencia S, Etto RM, Takahashi WY et al. Detection of Azospirillum brasilense by qPCR throughout a maize field trial. Appl Soil Ecol. 2021;160:103849. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2020.103849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vannier N, Mesny F, Getzke F et al. Genome-resolved metatranscriptomics reveals conserved root colonization determinants in a synthetic microbiota. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8274. 10.1038/s41467-023-43688-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas L, Paterno E. Growth enhancement and root colonization of sugarcane by plant growth-promoting bacteria. Philipp J Crop Sci. 2008;33:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wani PA, Khan MS, Zaidi A. Co-inoculation of nitrogen-fixing and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria to promote growth, yield and nutrient uptake in Chickpea. Acta Agron Hungarica. 2007;55:315–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. JOSS. 2019;4:1686. [Google Scholar]

- Würschum T, Langer SM, Longin CFH et al. A modern green revolution gene for reduced height in wheat. Plant J. 2017;92:892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang SR, Cook M, Saucier S et al. Development of amplified fragment length polymorphism-derived functional strain-specific markers to assess the persistence of 10 bacterial strains in soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microb. 2010;76:7126–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahya M, Rasul M, Sarwar Y et al. Designing synergistic biostimulants formulation containing autochthonous phosphate-solubilizing bacteria for sustainable wheat production. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegorenkova IV, Tregubova KV, Matora LY et al. Use of ELISA with antiexopolysaccharide antibodies to evaluate wheat-root colonization by the rhizobacterium paenibacillus polymyxa. Curr Microbiol. 2010;61:376–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadoks JC, Chang TT, Konzak CF. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974;14:415–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Ma Y, Jiang W et al. Development of a strain-specific quantification method for monitoring Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TF28 in the rhizospheric soil of soybean. Mol Biotechnol. 2020;62:521–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Horst A, Hill A, Gorman K. Palmerpenguins: palmer archipelago (antarctica) penguin data. R package version 0.1.0. 2020. 10.5281/zenodo.3960218 (23 February 2024, date last accessed). [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Yield parameters and qPCR data are available at the BONARES repository under the name “Production of wheat and barley under reduced input in organic farming.”