Abstract

Goal: Deep-seated tumors (DST) can be treated using thermoseeds exposed to a radiofrequency magnetic field for performing local interstitial hyperthermia treatment (HT). Several research efforts were oriented to the manufacturing of novel biocompatible magnetic nanostructured thermo-seeds, called magnetic scaffolds (MagS). Several iron-doped bioceramics or magnetic polymers in various formulations are available. However, the crucial evaluation of their heating potential has been carried out with significantly different, lab specific, variable experimental conditions and protocols often ignoring the several error sources and inaccuracies estimation. Methods: This work comments and provides a perspective analysis of an experimental protocol for the estimation methodology of the specific absorption rate (SAR) of MagS for DST HT. Numerical multiphysics simultions have been performed to outline the theoretical framework. After the in silico analysis, an experimental case is considered and tested. Results: From the simulations, we found that large overestimation in the SAR values can be found, due to the axial misplacement in the radiofrequency coil, while the radial misplacement has a lower impact on the estimated SAR value. Conclusions: The averaging of multiple temperature records is needed to reliably and effectively estimate the SAR of MagS for DST HT.

Keywords: Heating evaluation protocol, hyperthermia, magnetic biomaterials, specific absorption rate

I. Introduction

Cancer is a worldwide leading cause of death [1]. Malignant deep-seated tumors (DST - Fig. 1), such as cervix, colorectal, bladder carcinomas, brain malignancies or bone tumors, represent a class of neoplasms with peculiar clinical features [2], [3], [4]. The treatment of neoplasms grown in principal body cavities (e.g., abdomen, thorax, and skull) and deep sites is still challenging and demand for tumor- or patient-specific interventional strategies [4], [5]. DST gold standard treatments are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [5]. Despite the progresses, complementary techniques, such as immunotherapy [3], [5], have been investigated to control local recurrence rate, increasing the survival rate or enhance the quality of life. An emerging therapeutic strategy is the hyperthermia treatment (HT). HT proved to synergistically and significantly enhance the effectiveness of existing interventional strategies, such as chemio- and radiotherapy [2], [3], [4]. HT is a thermal therapy which aims to raise the temperature of a target tissue to 41–45  C for, at least, 30–60 min. This temperature range elicits the immune system response, increases the cytotoxicity and alters the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, it increases the permeability to chemotherapeutics and enhance the sensitivity to radiation therapy [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. The therapeutic heat can be administered to the DST through ultrasounds (US) [9], photothermal (PT) devices [10] and electromagnetic (EM) energy. However, US and PT approaches present technological issues, e.g., limited penetration depth, and are ineffective in targeting DST. EM energy has the advantages of being noninvasive, contacless and highly controllable. Hence, EM energy has been adopted in clinical practice to deliver HT to DST through apacitive electrodes (8, 13.5 or 27.12 MHz) or by using arrays of antenna systems (433, 915 or 2450 MHz) [11]. Despite showing interesting clinical perspectives, EM-based HT strategies require focusing techniques, optimization approaches and complex instrumentation [3], [4], [7], [12].

C for, at least, 30–60 min. This temperature range elicits the immune system response, increases the cytotoxicity and alters the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, it increases the permeability to chemotherapeutics and enhance the sensitivity to radiation therapy [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. The therapeutic heat can be administered to the DST through ultrasounds (US) [9], photothermal (PT) devices [10] and electromagnetic (EM) energy. However, US and PT approaches present technological issues, e.g., limited penetration depth, and are ineffective in targeting DST. EM energy has the advantages of being noninvasive, contacless and highly controllable. Hence, EM energy has been adopted in clinical practice to deliver HT to DST through apacitive electrodes (8, 13.5 or 27.12 MHz) or by using arrays of antenna systems (433, 915 or 2450 MHz) [11]. Despite showing interesting clinical perspectives, EM-based HT strategies require focusing techniques, optimization approaches and complex instrumentation [3], [4], [7], [12].

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the proposed experimental protocol for assessing the specific absorption rate (SAR) of biocompatible magnetic scaffolds (MagS) to be used as implants for local, interstitial hyperthermia treatment (HT) of deep-seated tumors (DST).

Therefore, different heat administration modalities in HT DST have been investigated. The treatment of colo-rectal cancers with ferromagnetic implants has been previously studied [13], [14], [15]. Ferromagnetic implants made of NiCu and PdCo alloy with low Curie temperature have been proposed [16]. In [17], the size and recurrence of liver neoplasms was managed with stainless steel thermoseeds, whilst in [18] nickel-copper thermoseeds against melanoma have been investigated. Recently, a spherical ferromagnetic composite implant for tumor bed hyperthermia has been numerically and experimentally characterized [19]. However, these metallic thermoseeds present some major drawbacks, namely the safety for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the biocompatibility and long-term stability issues. Furthermore, the heat is administered through the eddy currents dissipation mechanism, thus requiring relatively high working frequencies  MHz [13], [14], [15].

MHz [13], [14], [15].

Given the biocompatibility and post-operative, post-treatment aspects intrinsic of DST, ferromagnetic metal implant have been disregarded for the search of novel thermoseeds. To overcome such limitations, magnetic particle hyperthermia (MPH) for performing HT at these challenging tumor sites selectively has been proposed to treat regional and intra-tumoral regions with minimum intervention [20], [21], [22]. However, despite the expectations and potential of MPH, several aspects such as administration, treatable target volume, thermometry issues, potential toxicity and stability hinder its possible application against DST [23], [24], [25], [26].

The developement of new devices based on magnetic particles has been investigated. These solutions have been analyzed to maximize the heat delivered at the surgical bed site and control the local recurrence, while providing mechanical support to the injured tissue and provide a scaffold healthy tissue re-growth. So, the research focused on the development of multifunctional, theranostic platforms obtained by loading or doping an artificial tissue or a scaffold (bioceramic or polymeric) using magnetic particles (ferri-, ferro- or superparamagnetic) [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. Indeed, these magneto-responsive thermoseeds, called magnetic scaffolds (MagS), allow to perform the HT using a magnetic field in the kHz-range, after their implantation (Fig. 1). Then, following HT combined with chemio- or radiotherapy, MagS ensures a post-operative mechanical and biomimetic support for damaged tissue repair [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. The research is ongoing in this field. For instance, recently, a 3D printed superparamagnetic polymeric stent for treating tumors occurring in hollow organs was proposed and preliminary characterized [39]. In [40] poly-caprolactone (PCL) scaffolds have been drop-casted using iron oxide nanocrystals to obtain MagS for bone tumor treatment.

To push the forefront towards new clinical landscapes, a more definitive takeoff of using MagS for the DST HT is required. To this end, it is fundamental that MagS must satisfy the minimum quality assurance requirements of the interstitial hyperthermia treatment [49]. To treat DST, a given MagS should be capable of increasing the system temperature to the therapeutic level of 41–45  C and deposit a given amount of power per unit of mass (W/g) in the tumor volume in response to an alternating current (AC), radiofrequency (RF) magnetic field [11], [49]. The quantification of MagS hyperthermic potential is mandatory. When evaluating the hyperthermic efficiency we refer to the ability of a system to achieve hyperthermic conditions. So far, the heating efficiency of MagS has been reported in terms of the temperature increase (

C and deposit a given amount of power per unit of mass (W/g) in the tumor volume in response to an alternating current (AC), radiofrequency (RF) magnetic field [11], [49]. The quantification of MagS hyperthermic potential is mandatory. When evaluating the hyperthermic efficiency we refer to the ability of a system to achieve hyperthermic conditions. So far, the heating efficiency of MagS has been reported in terms of the temperature increase ( ) and time to reach it (

) and time to reach it ( ) [28], [33], [41]. However, in HT and, especially in MPH, the standardized and common metric of Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) has been adopted [49]. A discussion is in order. SAR is a measure of the energy, per unit time, absorbed by the target volume surrounding the thermoseed. Often, for MPH, the specific loss power (SLP) is considered. Even though these figure of merits have the same units (W/g), the SLP quantity describes the power achievable per gram of magnetic element in the material and refers to the energy dissipated by the MNPs to the system [50]. For MagS the adoption of SLP is not relevant, whilst the SAR as figure of merit is disregarded, or SAR has been evaluated with methodologically inappropriate means. As shown in Fig. 1, the way to quantify the heating response of a MagS is distinctly different from a typical MPH setup [50]. A different framework is needed. The proper setup to provide reliable heating evaluation will be rigorously explained and evaluated here. In the experimental estimation of the SAR several contributions must be considered. The factors affecting the SAR measurements are i) the AC magnetic field parameters (i.e. amplitude and frequency), ii) the exposure system features, iii) the thermometric aspects, but also iv) the MagS properties (e.g., the type of magnetic particle, their volume fraction, aggregation degree), as well as the biomaterial geometry and architecture. As a result, the comparison of different MagS is challenging. Recently, in [51], the influence of the geometry of a 3D-printed ferromagnetic MagS (i.e., pore size, distribution, porosity) on the HT performances have been investigated using three different experimental setups. While finding that architectural features of the MagS can impact on HT and heat diffusion, noticeable differences between calorimetric measurements carried out in air, deionized water and agar phantoms have been reported [50], [51]. Moving form these findings and considering the approach from [52], in [50] an accurate standardization protocol for determine the heating efficiency of 3D-printed MagS has been studied. In the current work, relying on an extensive analysis of the literature about the characterization of MagS for HT of DST, a thorough numerical study is carried out to identify the factors affecting the estimation of MagS SAR. Then, using ferromagnetic MagS samples [51], technical and methodological insights in the protocol proposed in [50] will be provided to drive an advanced characterization of the hyperthermic efficiency of MagS.

) [28], [33], [41]. However, in HT and, especially in MPH, the standardized and common metric of Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) has been adopted [49]. A discussion is in order. SAR is a measure of the energy, per unit time, absorbed by the target volume surrounding the thermoseed. Often, for MPH, the specific loss power (SLP) is considered. Even though these figure of merits have the same units (W/g), the SLP quantity describes the power achievable per gram of magnetic element in the material and refers to the energy dissipated by the MNPs to the system [50]. For MagS the adoption of SLP is not relevant, whilst the SAR as figure of merit is disregarded, or SAR has been evaluated with methodologically inappropriate means. As shown in Fig. 1, the way to quantify the heating response of a MagS is distinctly different from a typical MPH setup [50]. A different framework is needed. The proper setup to provide reliable heating evaluation will be rigorously explained and evaluated here. In the experimental estimation of the SAR several contributions must be considered. The factors affecting the SAR measurements are i) the AC magnetic field parameters (i.e. amplitude and frequency), ii) the exposure system features, iii) the thermometric aspects, but also iv) the MagS properties (e.g., the type of magnetic particle, their volume fraction, aggregation degree), as well as the biomaterial geometry and architecture. As a result, the comparison of different MagS is challenging. Recently, in [51], the influence of the geometry of a 3D-printed ferromagnetic MagS (i.e., pore size, distribution, porosity) on the HT performances have been investigated using three different experimental setups. While finding that architectural features of the MagS can impact on HT and heat diffusion, noticeable differences between calorimetric measurements carried out in air, deionized water and agar phantoms have been reported [50], [51]. Moving form these findings and considering the approach from [52], in [50] an accurate standardization protocol for determine the heating efficiency of 3D-printed MagS has been studied. In the current work, relying on an extensive analysis of the literature about the characterization of MagS for HT of DST, a thorough numerical study is carried out to identify the factors affecting the estimation of MagS SAR. Then, using ferromagnetic MagS samples [51], technical and methodological insights in the protocol proposed in [50] will be provided to drive an advanced characterization of the hyperthermic efficiency of MagS.

II. Literature Review

Several MagS have been manufactured, such as the hadrystonite chemically doped with Fe ions [53], or the magnetic bioceramic for enhancing radiotherapy [54], and the Fe O

O -akermanite scaffold with self-catalytic activity [55]. In this framework, it is fundamental to provide a reliable way to compare these different biomaterials from the HT point of view. Despite the adoption of shared metrics, it is mandatory to manage and solve the measurement issues related to the heating efficiency. These tests are strongly dependent on the sample geometry and the measurement conditions (e.g., type of apparatus, field homogeneity, thermometry, etc.), but also on the estimation methodology. Indeed, the development, validity and effectiveness of procedure for evaluating the SAR of MagS is a highly underestimated aspect in the literature. Here, we will analyze the literature about MagS for the DST HT focusing on the experimental setups and methodologies used for evaluating their hyperthermic performances.

-akermanite scaffold with self-catalytic activity [55]. In this framework, it is fundamental to provide a reliable way to compare these different biomaterials from the HT point of view. Despite the adoption of shared metrics, it is mandatory to manage and solve the measurement issues related to the heating efficiency. These tests are strongly dependent on the sample geometry and the measurement conditions (e.g., type of apparatus, field homogeneity, thermometry, etc.), but also on the estimation methodology. Indeed, the development, validity and effectiveness of procedure for evaluating the SAR of MagS is a highly underestimated aspect in the literature. Here, we will analyze the literature about MagS for the DST HT focusing on the experimental setups and methodologies used for evaluating their hyperthermic performances.

The calorimetric characterization of samples of poly-metilmetacrilate (PMMA) embedding Fe O

O particles have been carried out by recording with an infrared camera (IR) the temperature of the saline-sample system exposed to an RF magnetic field [42]. In [42], Kexiao et al. considered different amount of saline volume (0.1 mL–0.2 mL), demonstrating a variability of

particles have been carried out by recording with an infrared camera (IR) the temperature of the saline-sample system exposed to an RF magnetic field [42]. In [42], Kexiao et al. considered different amount of saline volume (0.1 mL–0.2 mL), demonstrating a variability of  C from the maximum recorded temperature. Furthermore, issues in the repeatability due to the MagS sample placement inside the coil are evident (see Fig. 3, pg. 4198 from [42]). The misalignment of thermoseed implants to the external heating device is a relevant aspect for estimating the temperature and power losses [56]. For the P

C from the maximum recorded temperature. Furthermore, issues in the repeatability due to the MagS sample placement inside the coil are evident (see Fig. 3, pg. 4198 from [42]). The misalignment of thermoseed implants to the external heating device is a relevant aspect for estimating the temperature and power losses [56]. For the P O

O -Fe

-Fe O

O -CaO-SiO

-CaO-SiO ferromagnetic glass ceramic for bone tumor HT a 0.26 W/g SAR value has been estimated. The linear slope method has been used. The sample has been exposed to a 0.5 mT magnetic field, produced by a custom coil apparatus working at 100 kHz [43]. The HT potential characterization was carried out on a test tube, filled with deionized water. The temperature has been recorded every 60 s for 3 min with an optical fiber (OF) thermometer. The 2–3 mm in diameter and 0.9 g samples of apatite wollastonite, heat-treated glass ceramic (29% CaO, 31% SiO

ferromagnetic glass ceramic for bone tumor HT a 0.26 W/g SAR value has been estimated. The linear slope method has been used. The sample has been exposed to a 0.5 mT magnetic field, produced by a custom coil apparatus working at 100 kHz [43]. The HT potential characterization was carried out on a test tube, filled with deionized water. The temperature has been recorded every 60 s for 3 min with an optical fiber (OF) thermometer. The 2–3 mm in diameter and 0.9 g samples of apatite wollastonite, heat-treated glass ceramic (29% CaO, 31% SiO , 40% Fe

, 40% Fe O

O , 3% BzO

, 3% BzO , 3% P

, 3% P O

O - wt%), synthesized by the group of Kokubo, have been implanted in rat tibial metaphysis and then characterized under the action of a 100 kHz, 30 mT external magnetic field produced by a C-type toroidal core of an induction generator [44]. The heating ability of the glass-ceramic implants has been assessed through fluoroptic thermometers (FT), recording a maximum temperature at the center of the thermoseed equal to 45

- wt%), synthesized by the group of Kokubo, have been implanted in rat tibial metaphysis and then characterized under the action of a 100 kHz, 30 mT external magnetic field produced by a C-type toroidal core of an induction generator [44]. The heating ability of the glass-ceramic implants has been assessed through fluoroptic thermometers (FT), recording a maximum temperature at the center of the thermoseed equal to 45  C after 50 min, resulting in an estimated SAR of 10 W/g. The temperature variation in the rat tibia was of about

C after 50 min, resulting in an estimated SAR of 10 W/g. The temperature variation in the rat tibia was of about  C in the extra-cortical regions, indicating a large variability due to the temperature probe positioning [44]. Calorimetric measurements performed with a magnetic induction furnace on sol-gel calcium zinc iron silicon oxide samples have been performed in [45], [57]. The measurements have been carried out by placing 2 g of glass ceramic, with ferromagnetic ZnFe

C in the extra-cortical regions, indicating a large variability due to the temperature probe positioning [44]. Calorimetric measurements performed with a magnetic induction furnace on sol-gel calcium zinc iron silicon oxide samples have been performed in [45], [57]. The measurements have been carried out by placing 2 g of glass ceramic, with ferromagnetic ZnFe O

O particles, in 20 ml deionized water in a quartz cuvette, positioned in the coil center. The temperature rise, recorded with a thermocouple (TC - 0.1

particles, in 20 ml deionized water in a quartz cuvette, positioned in the coil center. The temperature rise, recorded with a thermocouple (TC - 0.1  C resolution), starting from 24

C resolution), starting from 24  C, ranged from a minimum 29

C, ranged from a minimum 29  C to a maximum of 39

C to a maximum of 39  C in 3 min under the action of a 50 mT magnetic field working at 100 kHz. The estimated SAR varies in the range 5–9 W per gram of sample [45]. The 3D-printed, superparamagnetic PCL scaffolds embedding mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) and magnetite nanoparticles (Fe

C in 3 min under the action of a 50 mT magnetic field working at 100 kHz. The estimated SAR varies in the range 5–9 W per gram of sample [45]. The 3D-printed, superparamagnetic PCL scaffolds embedding mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) and magnetite nanoparticles (Fe O

O ) have been manufactured and characterized as tissue substitutes, drug delivery systems and hyperthermia agents [46]. The magnetic MBG-PCL, when exposed to a 409 kHz and 18 mT magnetic field (DM100 System - nB nanoScale Biomagnetics, Spain) increased the temperature of 1 ml of water up to 60

) have been manufactured and characterized as tissue substitutes, drug delivery systems and hyperthermia agents [46]. The magnetic MBG-PCL, when exposed to a 409 kHz and 18 mT magnetic field (DM100 System - nB nanoScale Biomagnetics, Spain) increased the temperature of 1 ml of water up to 60  C, starting from 20

C, starting from 20  C, for 8 min - 15 min of exposure [46]. The temperature has been recorded with an optical fiber, but the details about its placement and the effect on the measurement has not been evaluated. The intrinsic magnetic hydroxyapatite (HA) obtained by chemical doping could increase the temperature of distilled water of 40

C, for 8 min - 15 min of exposure [46]. The temperature has been recorded with an optical fiber, but the details about its placement and the effect on the measurement has not been evaluated. The intrinsic magnetic hydroxyapatite (HA) obtained by chemical doping could increase the temperature of distilled water of 40  C in 60 s, under the action of a 15 mT and 293 kHz magnetic field [41]. The magnetite loaded PCL scaffold from [41], under the same treatment parameter, reached only a 10

C in 60 s, under the action of a 15 mT and 293 kHz magnetic field [41]. The magnetite loaded PCL scaffold from [41], under the same treatment parameter, reached only a 10  C increase, after 3 min. SAR values ranging from 5 to 30 W/g have been obtained for the weakly supeparamagnetic tri-calcium phosphate (

C increase, after 3 min. SAR values ranging from 5 to 30 W/g have been obtained for the weakly supeparamagnetic tri-calcium phosphate ( -Ca

-Ca (PO

(PO ) co-substituted with Fe

) co-substituted with Fe -Co

-Co ions thermo-seeds exposed to a 335 kHz and 13.5 mT magnetic field, in 1 mL of distilled water, for 40 min (

ions thermo-seeds exposed to a 335 kHz and 13.5 mT magnetic field, in 1 mL of distilled water, for 40 min ( of 12-22.5

of 12-22.5  C, starting from 26

C, starting from 26  C, measured with a copper TC) [47]. More recently, the calorimetric response of injectable graphite-modified Fe

C, measured with a copper TC) [47]. More recently, the calorimetric response of injectable graphite-modified Fe O

O -calcium phosphate bone cement scaffolds (9 mm x 4 mm blocks) from the work of Zhang et al. has been tested under the action of a 340 kHz, 10 mT magnetic field. SAR values of 18.7–30.2 W/g have been obtained from the temperature increase after 200 s, acquired by means of an infrared thermometer [48].

-calcium phosphate bone cement scaffolds (9 mm x 4 mm blocks) from the work of Zhang et al. has been tested under the action of a 340 kHz, 10 mT magnetic field. SAR values of 18.7–30.2 W/g have been obtained from the temperature increase after 200 s, acquired by means of an infrared thermometer [48].

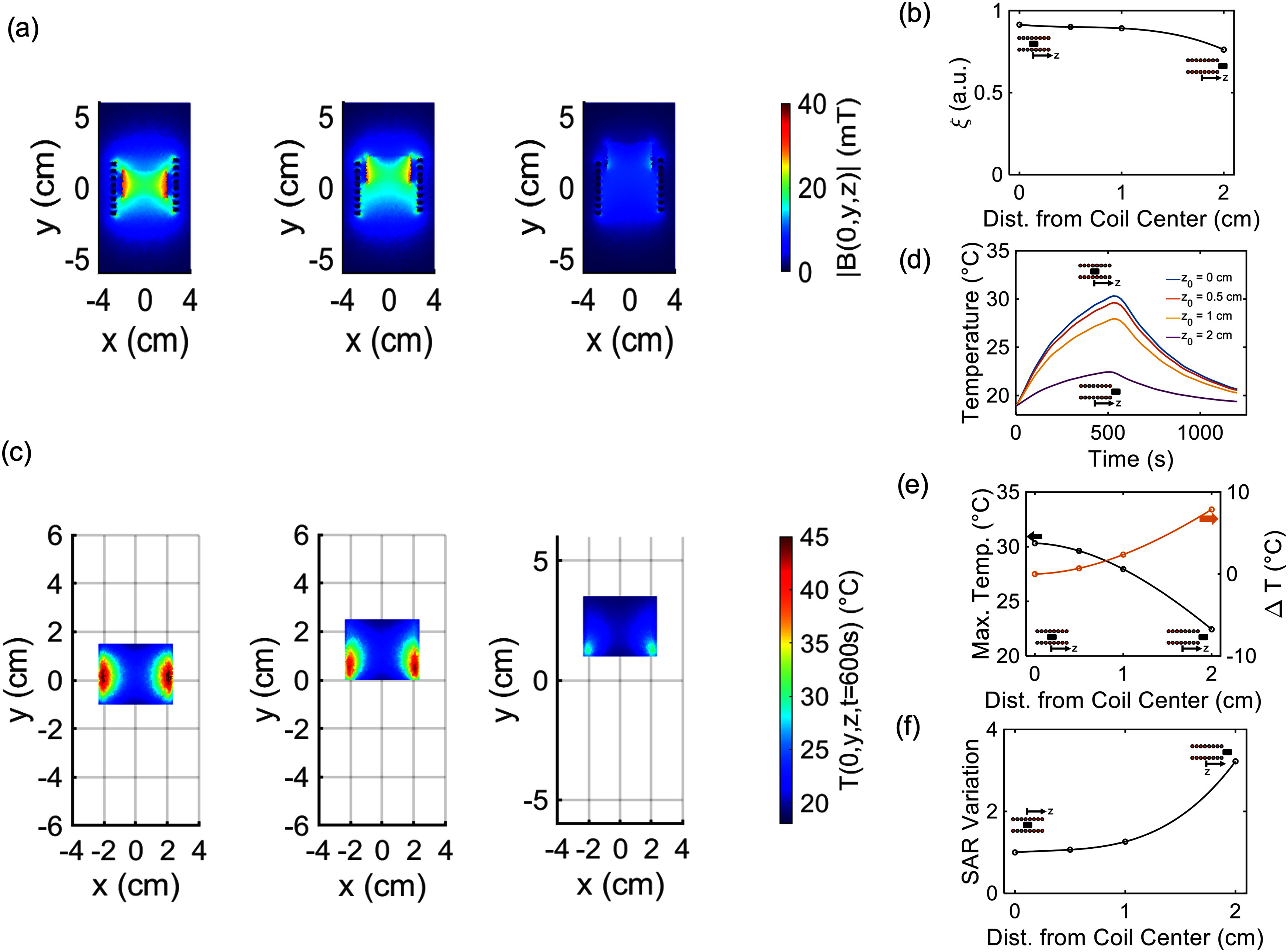

Fig. 3.

(a) Magnetic flux density distribution, in mT, for different position of the sample in the coil ( 0 cm,

0 cm,  1 cm,

1 cm,  2 cm). (b) Field homogeneity (

2 cm). (b) Field homogeneity ( ) for different sample placement. (c) Temperature distribution (

) for different sample placement. (c) Temperature distribution ( )), at

)), at  600 s, for different position of the sample in the coil (

600 s, for different position of the sample in the coil ( 0 cm,

0 cm,  1 cm,

1 cm,  2 cm). (d) Average magnetic scaffold (MagS) temperature versus time. (e) Peak temperatures, and relative differences between the initial condition for different coil axial positions. (f) Relative SAR variation, with respect to the initial condition, for different sample placement in the coil.

2 cm). (d) Average magnetic scaffold (MagS) temperature versus time. (e) Peak temperatures, and relative differences between the initial condition for different coil axial positions. (f) Relative SAR variation, with respect to the initial condition, for different sample placement in the coil.

Nowadays, noticeable research efforts are spent for defining standardized protocols for characterizing the hyperthermic potential of magnetic ferrofluid for MPH [26], [52], [58], raising issues about inter-laboratory variations ( 30% variation on the estimated SAR) and unveiling the various sources of uncertainties. This type of analysis and reasoning has not been carried out and applied to the experimental protocols for measuring the SAR of MagS. Indeed, by carefully looking at Table I, noticeable differences can be noticed in the characterization of MagS for HT. Very different working frequencies and field amplitudes have been used, as well as diverse thermometric approaches have been adopted. Also, the preferred media is deionized water, even though non-negligible convective contribution may influence the heat diffusion at the MagS interface [50], [51], [52]. Furthermore, it is worth stressing that, in the cited works, the external magnetic field is not turned off to investigate the effective heating and the thermal contribution of the background media (e.g., air, water, phantom or tissue) has not been taken into account properly [52]. Furthermore, SAR is not derived in most cases (Table I). Under these fuzzy experimental conditions, the effect of the variability of the experimental setups, combined with the neglection of uncertainty sources, is evident and results in SAR values in the range 0.2–30 W/g. This scenario is concerning and deserves a critical and engineering approach. With respect to the estimation of the SAR in the case of MPH, for MagS the situation is at an early stage and must be tackled immediately in order to set the limits, regulations and validity criteria for quantifying the hyperthermic potential of these innovative medicine tools for the HT of DTS.

30% variation on the estimated SAR) and unveiling the various sources of uncertainties. This type of analysis and reasoning has not been carried out and applied to the experimental protocols for measuring the SAR of MagS. Indeed, by carefully looking at Table I, noticeable differences can be noticed in the characterization of MagS for HT. Very different working frequencies and field amplitudes have been used, as well as diverse thermometric approaches have been adopted. Also, the preferred media is deionized water, even though non-negligible convective contribution may influence the heat diffusion at the MagS interface [50], [51], [52]. Furthermore, it is worth stressing that, in the cited works, the external magnetic field is not turned off to investigate the effective heating and the thermal contribution of the background media (e.g., air, water, phantom or tissue) has not been taken into account properly [52]. Furthermore, SAR is not derived in most cases (Table I). Under these fuzzy experimental conditions, the effect of the variability of the experimental setups, combined with the neglection of uncertainty sources, is evident and results in SAR values in the range 0.2–30 W/g. This scenario is concerning and deserves a critical and engineering approach. With respect to the estimation of the SAR in the case of MPH, for MagS the situation is at an early stage and must be tackled immediately in order to set the limits, regulations and validity criteria for quantifying the hyperthermic potential of these innovative medicine tools for the HT of DTS.

TABLE I. State-of-The-Art Analysis of Calorimetric Characterization of Magnetic Scaffolds.

| Biomaterial | Magnetic Phase |

(kHz) (kHz) |

(mT) (mT) |

( ( C) C) |

( ( C) C) |

(min) (min) |

Thermometry | Medium | SAR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | Fe  O O

|

270 | 3.7 | 16 | - | 15 | IR | Bile duct | - | [39] |

| HA | Fe  O O , Fe , Fe  O O

|

293 | 15 | 35 | 25 | 0.5 | OF | Deionized water | - | [41] |

| Gelatin | Fe  O O

|

293 | 15 | 17.5 | - | 1 | OF | Deionized water | - | [41] |

| PCL | Fe  O O

|

293 | 10 | - | - | 5 | OF | Deionized water | - | [41] |

| PMMA | Fe  O O

|

- | - | 70 | 25 | 3 | IR | Saline | - | [42] |

P  O O -CaO-SiO -CaO-SiO

|

Fe  O O

|

100 | 0.5 | 16 | 15 | 16 | OF | Deionized water | 0.2 | [43] |

CaO-SiO  -BzO -BzO -P -P O O

|

Fe  O O

|

100 | 30 | 15 | 32 | 50 | FT | Rat Tibia | 10 | [44] |

Ca-SiO

|

ZnFe  O O

|

100 | 50 | 27-39 | 20 | 3 | TC | Deionized water | 6.5-9 | [45] |

| MBG-PCL | Fe  O O

|

409 | 18 | 60-40 | 20 | 8-15 | OF | Deionized water | 1.4-4.7 | [46] |

Ca (PO (PO

|

Fe  O O , Fe , Fe  O O

|

335 | 13.5 | 12-22.5 | 26 | 40 | TC | Deionized water | - | [47] |

Ca (PO (PO

|

Fe  O O

|

340 | 10 | - | - |

3 3 |

IR | Air | 18.7-30.2 | [48] |

(FT = Fluoroptic Thermometer, IR = IR Camera, of = Optical Fiber, TC = Thermocouple).

III. Numerical Study

Given the lacks and flaws highlighted in reviewing the literature, in this work, we will perform numerical simulations and experiments to investigate the source of errors, the factors of influence and the most relevant aspects in the characterization of the hyperthermic potential of MagS for HT of DTS.

A. Numerical Model

The finite element method (FEM) commercial software Comsol Multiphysics v5.5 (Comsol Inc., Burlinghton, MA USA) has been used to simulate the experimental setup proposed in [50], [51] for the SAR measurements and analyze it in detail (Fig. 1). The geometry for the simulation is shown in Fig. 2. A homogeneous cylindrical scaffold having magnetic permeability  , dielectric permittivity

, dielectric permittivity  and elecrtical conductivity

and elecrtical conductivity  has been considered. In this work we will consider a homogeneous geometry, even though MagS architectures are porous structures that can present complex geometry and variable tortuosity. The cylinder has diameter

has been considered. In this work we will consider a homogeneous geometry, even though MagS architectures are porous structures that can present complex geometry and variable tortuosity. The cylinder has diameter  cm and height

cm and height  cm. The thermoseed is placed in an agar phantom (

cm. The thermoseed is placed in an agar phantom ( cm,

cm,  cm), as shown in Fig. 2.

cm), as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

(a) System geometry for the numerical simulations of the different experimental setup for the calorimetric characterization of magnetic scaffolds (MagS). The heating system has conductors mad of copper, whilst the light grey cylinder represent the agarose matrix and the dark grey cylinder is the MagS. (b) Representation of the possible misplacement of the scaffold in the agar phantom. (c) Screenshot of the system geometry in Comsol Multiphysics v5.5 (Comsol Inc., Burlinghton, MA USA).

The induction heating coil is a single layer coil having  turns. The coil is excited with a sinusoidal current (

turns. The coil is excited with a sinusoidal current ( ), working at

), working at  kHz, which is turn on at

kHz, which is turn on at  , and turned-off at specific time

, and turned-off at specific time  .

.

The calorimetric measurements is governed by the Ampere's law, in the time-harmonic fields formulation, so that

|

where  is the magnetic vector potential,

is the magnetic vector potential,  is the magnetic vector (Am

is the magnetic vector (Am  ),

),  is the electric field vector (Vm

is the electric field vector (Vm ), whilst

), whilst  is the electrical conductivity (in S

is the electrical conductivity (in S m

m ),

),  is the current density (A

is the current density (A  m

m ). The term

). The term  is the electric displacement field (C

is the electric displacement field (C  m

m ), being

), being  the vacuum dielectric permittivity. In (1)–(4),

the vacuum dielectric permittivity. In (1)–(4),  is the external current density (A

is the external current density (A  m

m ). The AC/DC module, in particular the Magnetic Field interface, has been used to solve (1)–(4). Once the magnetic field distribution has been computed, we evaluated the field homogeneity (

). The AC/DC module, in particular the Magnetic Field interface, has been used to solve (1)–(4). Once the magnetic field distribution has been computed, we evaluated the field homogeneity ( ) in the MagS volume by calculating

) in the MagS volume by calculating

|

where  and

and  are the mean value and the standard deviation of the magnetic field in the MagS sample volume.

are the mean value and the standard deviation of the magnetic field in the MagS sample volume.

The key aspect during SAR mesurements is the heat dissipation of MagS. Depending on their magnetic features different mechanisms hold. A clarification is in order. In MagS, the embedded magnetic particles are the main elements responsible for the heat dissipation. Magnetic particles are known to dissipate heat via different independent mechanisms, i.e. eddy currents, hysteresis loss, Brownian relaxation and Neél relaxation. The eddy currents thermal energy conversion can be neglected [52]. On the other hand, hysteresis losses are due to the shift of magnetic domain walls in multi-domain materials and occurs in magnetic particles with a diameter higher than 200 nm. For smaller particles, if the magnetic anisotropy of the particle is higher than the viscous resistance of the surrounding medium, then the particle can rotate and generate heat due to the shear with the carrier fluid. However, for the case of MagS, the magnetic particles are embeded in a solid or very viscous matrix, and hence the Brownian relaxation process would be negligible or completely blocked, as already studied in [59]. Finally, for smaller magnetic particles ( 15 nm), is the Neél mechanism that can be relevant. In this case, the heating is achieved by the dissipation due to the rearrangement during the rotation of the particle magnetic moment against its energy barrier [21]. From Table I, several MagS present ferromagnetic response. Therefore, in this work, we will focus on a ferromagnetic MagS. The exposure of a ferromagnetic scaffold to a time-varying magnetic field determines a dissipated power (

15 nm), is the Neél mechanism that can be relevant. In this case, the heating is achieved by the dissipation due to the rearrangement during the rotation of the particle magnetic moment against its energy barrier [21]. From Table I, several MagS present ferromagnetic response. Therefore, in this work, we will focus on a ferromagnetic MagS. The exposure of a ferromagnetic scaffold to a time-varying magnetic field determines a dissipated power ( in Wm

in Wm ) to be computed as

) to be computed as

|

where  is the hysteresis loop area of the MagS, scaled by the specific density of the sample. Therefore, the

is the hysteresis loop area of the MagS, scaled by the specific density of the sample. Therefore, the  curve, derived from static magnetic measurements, has been inserted in Comsol, interpolated linearly and used in the simulations [51]. Equation (6) is proportional to the mass of MagS sample. A remark is in order. For some of MagS reported in Table I, superparamagnetic nanoparticles have been used to functionalize the biomaterial and create a thermoseed. The proposed model can be applied to these systems by simply modifying (6) and substituing a suitable model for the power dissipation, as done in [60].

curve, derived from static magnetic measurements, has been inserted in Comsol, interpolated linearly and used in the simulations [51]. Equation (6) is proportional to the mass of MagS sample. A remark is in order. For some of MagS reported in Table I, superparamagnetic nanoparticles have been used to functionalize the biomaterial and create a thermoseed. The proposed model can be applied to these systems by simply modifying (6) and substituing a suitable model for the power dissipation, as done in [60].

In this work, we will focus on a ferromagnetic polymeric scaffold, which will be considered as a case study. For this kind of MagS, the term  is higher than the power dissipated due to the eddy currents in the ferromagnetic and in the agar material (

is higher than the power dissipated due to the eddy currents in the ferromagnetic and in the agar material ( ). However, the dielectric heating in the phantom cannot be neglected, being relevant to the measured temperature and the estimated SAR. Therefore, to investigate the heat transfer phenomena during the characterization of the heating efficiency of MagS, the following transient heat transfer equation has been solved

). However, the dielectric heating in the phantom cannot be neglected, being relevant to the measured temperature and the estimated SAR. Therefore, to investigate the heat transfer phenomena during the characterization of the heating efficiency of MagS, the following transient heat transfer equation has been solved

|

where  is the material density (kg

is the material density (kg  m

m ),

),  is the specific heat capacity (J

is the specific heat capacity (J  kg

kg K

K  ), and

), and  is the thermal conductivity (W

is the thermal conductivity (W m

m K

K  ). In (7), the term

). In (7), the term  is the heat flux due to convection, for which

is the heat flux due to convection, for which  is a velocity (in m

is a velocity (in m  s

s ). This term can be approximated through suitable boundary condition for air-solid interfaces, but cannot be neglected for heat transfer phenomena occuring in some fluids, such as water [50], [51], [52]. Therefore, in this work, to study also the different experimental setup and measurement environment found in the literature (Table I), we simulated the cases of MagS tested in air and in distilled water. More details about the simulations are given in the Supplementary Material (Supp. Mat.). The physical properties of the samples are reported in Table II. Equation (7) is solved assuming continuity of temperature and heat flux. At the agar-air interface the heat exchange is ruled by convection, so that

). This term can be approximated through suitable boundary condition for air-solid interfaces, but cannot be neglected for heat transfer phenomena occuring in some fluids, such as water [50], [51], [52]. Therefore, in this work, to study also the different experimental setup and measurement environment found in the literature (Table I), we simulated the cases of MagS tested in air and in distilled water. More details about the simulations are given in the Supplementary Material (Supp. Mat.). The physical properties of the samples are reported in Table II. Equation (7) is solved assuming continuity of temperature and heat flux. At the agar-air interface the heat exchange is ruled by convection, so that

|

where  is the normal vector and

is the normal vector and  C. The value of the heat transfer coefficient (

C. The value of the heat transfer coefficient ( ) reported in [51] has been used. The system was considered to be in thermal equilibrium at

) reported in [51] has been used. The system was considered to be in thermal equilibrium at  and a homogenous initial temperature distribution

and a homogenous initial temperature distribution  has been assumed. The Heat Transfer in Solid interface has been used.

has been assumed. The Heat Transfer in Solid interface has been used.

TABLE II. Material Properties.

The simulated temperature field is used to compute the SAR as [50], [51], [52]

|

where  is the specific heat is that of the agarose phantom, as taken from [61], [62], [63]. The term

is the specific heat is that of the agarose phantom, as taken from [61], [62], [63]. The term  is the initial slope of the heating curve.

is the initial slope of the heating curve.

The MagS was assumed to be placed in the middle of the coil ( , depoloyed at half of the coil height, i.e.,

, depoloyed at half of the coil height, i.e.,  ), initially. Then, we numerically investigated how the scaffold positioning in the induction heating system could affect the maximum temperature and the estimated SAR. In this framework, we considered two scenarios. We moved the MagS along the

), initially. Then, we numerically investigated how the scaffold positioning in the induction heating system could affect the maximum temperature and the estimated SAR. In this framework, we considered two scenarios. We moved the MagS along the  -axis of the system up to 2 cm from its initial position, while leaving unchanged its radial position. Then, we simulated the possibility that the scaffold position varies in the

-axis of the system up to 2 cm from its initial position, while leaving unchanged its radial position. Then, we simulated the possibility that the scaffold position varies in the  -plane by varying the sample center coordinates ranging from

-plane by varying the sample center coordinates ranging from  mm to 3 mm with a 1 mm step.

mm to 3 mm with a 1 mm step.

B. In-Silico Findings

In this work we numerically investigated the experimental setups used for measuring the SAR of MagS. As reported in Table I the sample can be placed in different environments and media. Under these conditions, adequate thermometric methods should be implemented. However, some limitations, source of errors and potential shrotcomings exists and must be considered. We simulated the cases of MagS placed in-air and in-distilled water for measuring their SAR, as described in the Supp. Mat.

For the in-air case, which is the easier setup to implementi in a laboratory, the sample is placed in an induction coil and exposed to the magnetic field. The temperature can be recorded using an IR camera. As a matter of fact, only surface temperature ( ) is acquired and can be post-processed to derive the SAR. By comparing the average surface temperature and the average volume temperature of a homogeneous cylindrical MagS exposed to a 30 mT and 400 kHz, a

) is acquired and can be post-processed to derive the SAR. By comparing the average surface temperature and the average volume temperature of a homogeneous cylindrical MagS exposed to a 30 mT and 400 kHz, a  C difference in the peak temperature exists (see Suppl. Mat.). Therefore, the SAR values which could be derived for the in-air experimental setup cannot be considered to be reliable. Hence, the results and the method reported in [48] cannot be used and applied. Furthermore, MagS are designed to present an architecture with a high interconncted porosity (

C difference in the peak temperature exists (see Suppl. Mat.). Therefore, the SAR values which could be derived for the in-air experimental setup cannot be considered to be reliable. Hence, the results and the method reported in [48] cannot be used and applied. Furthermore, MagS are designed to present an architecture with a high interconncted porosity ( %). The temperature patterns and the heat diffusion in the pores contributes to the heating in the surroundings [51]. Hence, for the in-air setup and IR thermometry, the role of the MagS porosity on the heat transfer could not be fully elucidated and properly accounted in the SAR estimation.

%). The temperature patterns and the heat diffusion in the pores contributes to the heating in the surroundings [51]. Hence, for the in-air setup and IR thermometry, the role of the MagS porosity on the heat transfer could not be fully elucidated and properly accounted in the SAR estimation.

As regards the methodologies and the findings from [43], [45], [46], [47], in which the MagS are placed in saline or deionized water, a discussion is in order. During the RF heating of the MagS placed in water, the presence and action of convective motion due to the temperature gradients and local variation of the fluid physical properties must be considered, Indeed, neglecting the aspects related to sample deployement and the issues linked to the temperature probe placement, by numerically studying the average-temperature of the MagS in presece of natural convection lead to  °C difference in the peak tempeature, while affecting the cooling rate (see Supp. Mat.). The non-linear effects of this natural convection on the heating and cooling dynamics cause this measurement setup to be difficult to implement, since the control of its conditions is not trivial. In this framework, the use of different temperature recording strategies (e.g., OF or TC- Table I) further stress the need of a standardized setup in the measurements MagS SAR.

°C difference in the peak tempeature, while affecting the cooling rate (see Supp. Mat.). The non-linear effects of this natural convection on the heating and cooling dynamics cause this measurement setup to be difficult to implement, since the control of its conditions is not trivial. In this framework, the use of different temperature recording strategies (e.g., OF or TC- Table I) further stress the need of a standardized setup in the measurements MagS SAR.

Moving from these findings and considerations, in [50], [51] it has been proposed to place the MagS in an agarose phantom, expose the sample to the RF magnetic field for heating it and then derive the SAR. Indeed, an agarose matrix can mimic the cellular environment, while providing a flexible option for calorimetric measurements [50]. Despite solving some potential critical aspects and shortcomings of the in-air and in-water setups, the in-agar SAR tests have not been deeply investigated in [50], [51]. Indeed, methodological details such as sample placement and the homogeneity of the magnetic field have never been considered.

As regards the numerical study of the MagS sample misplacement, in this study we considered two situations. A potential source of error in the SAR values can be related to the placement of the sample along the coil axis. We simualted some RF heating experiments for which the MagS is placed is deployed in different  positions. The findings are reported in Fig. 3. From Fig. 3(a), it can be noticed that as the sample is moved away from the initial position

positions. The findings are reported in Fig. 3. From Fig. 3(a), it can be noticed that as the sample is moved away from the initial position  , the magnetic flux density values and the field homogeneity

, the magnetic flux density values and the field homogeneity  lower (Fig. 3(b)). Coherently, the strength and the uniformity of the magnetic field over the sample is lower, therefore the temperature distribution inside the agar phantom and the MagS lowers too (Fig. 3(c)), and asymmetries in the heating pattern arise. The average temperature in the MagS cylinder for the different cases of sample placement is shown in Fig. 3(d). The most remarkable features that depends on the axial distance from the coil center (

lower (Fig. 3(b)). Coherently, the strength and the uniformity of the magnetic field over the sample is lower, therefore the temperature distribution inside the agar phantom and the MagS lowers too (Fig. 3(c)), and asymmetries in the heating pattern arise. The average temperature in the MagS cylinder for the different cases of sample placement is shown in Fig. 3(d). The most remarkable features that depends on the axial distance from the coil center ( ) is the peak temperature. In Fig. 3(e) it can be seen that, with respect to the sample placed in the center of the coil, more than 10

) is the peak temperature. In Fig. 3(e) it can be seen that, with respect to the sample placed in the center of the coil, more than 10  C of difference in the peak temperature can be recorded. As a matter of fact, considering (9), the different peak temperature would impact on the term

C of difference in the peak temperature can be recorded. As a matter of fact, considering (9), the different peak temperature would impact on the term  . Therefore, considering the ratio between the SAR at

. Therefore, considering the ratio between the SAR at  and the other cases, since the

and the other cases, since the  decreases, the estimated SAR would be higher. Even though these findings may appear trivial, considering the methodology and results reported in [42], these results demonstrate that the sample placement is a key factor for an accurate estimation of the SAR. The best condition for evaluating the heating efficiency of the MagS is to expose them to a magnetic field as homogeneous as possible.

decreases, the estimated SAR would be higher. Even though these findings may appear trivial, considering the methodology and results reported in [42], these results demonstrate that the sample placement is a key factor for an accurate estimation of the SAR. The best condition for evaluating the heating efficiency of the MagS is to expose them to a magnetic field as homogeneous as possible.

The previous simulations and in silico findings were derived considering a MagS placed perfectly centered in the coil ( ). However, it is likely that during the phantom preparation and the MagS incorporation, the sample can be placed incorrectly and could shift from the center. The homogeneity of the field would be slightly affected (in the measure of few % - see Supp. Mat.), but relevant effects on the estimated SAR could arise. Therefore, we simualated the SAR test for a MagS with initial position is moved away from the center in the range

). However, it is likely that during the phantom preparation and the MagS incorporation, the sample can be placed incorrectly and could shift from the center. The homogeneity of the field would be slightly affected (in the measure of few % - see Supp. Mat.), but relevant effects on the estimated SAR could arise. Therefore, we simualated the SAR test for a MagS with initial position is moved away from the center in the range  mm and

mm and  mm. The findings are given in Fig. 4. Considering the simulated volume-averaged temperature curves, slight differences in the peak temperature can be noticed, as shown in Fig. 4(a). In particular, a maximum difference of 1

mm. The findings are given in Fig. 4. Considering the simulated volume-averaged temperature curves, slight differences in the peak temperature can be noticed, as shown in Fig. 4(a). In particular, a maximum difference of 1  C has been found (see Supp. Mat.). However, less than 1

C has been found (see Supp. Mat.). However, less than 1  C of difference in the

C of difference in the  results in a large SAR variation (Fig. 4(b)). In terms of percentage variation, considering the initial position

results in a large SAR variation (Fig. 4(b)). In terms of percentage variation, considering the initial position  as reference (see Fig. 2), the SAR can be overestimate up to the 8%. Of course, given these findings, a combination of axial and radidal displacemtne can be key factors in the drastic misestimation of the SAR.

as reference (see Fig. 2), the SAR can be overestimate up to the 8%. Of course, given these findings, a combination of axial and radidal displacemtne can be key factors in the drastic misestimation of the SAR.

Fig. 4.

(a) Simulated average temperature of the magnetic thermossed as a function of time. There is a partial overlap of the curves. (b) Percentual variation of the SAR with respect to the values estimated for the scaffolds placed in  .

.

The findings of our numerical simulations highlight that the sample placement is crucial and must be carefully considered before applying the proposed methodology to estimate the SAR of MagS. The numerical study is preliminary and the experimental part cannot be disregarded.

IV. Experimental Setup

A. Magnetic Scaffold: Architecture and 3D-Printing

The scaffold samples considered in this study are made of PolyLactic Acid (PLA) filament loaded with iron particles (Proto-Pasta, USA - PP herein), with a 40 wt.% content of microparticles having an average size of  40

40  m. The scaffold architecture was created using Rhinoceros 7 (Mc Neel, Canada) modeling software, then the ideaMaker (Raise 3D Technologies, Inc., USA) was used to derive the stereolithography (STL) files and the g-code for printing them by using the Raise3D Pro2 Plus 3-D FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) printer. The extrusion temperature was set to 210

m. The scaffold architecture was created using Rhinoceros 7 (Mc Neel, Canada) modeling software, then the ideaMaker (Raise 3D Technologies, Inc., USA) was used to derive the stereolithography (STL) files and the g-code for printing them by using the Raise3D Pro2 Plus 3-D FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) printer. The extrusion temperature was set to 210  C for the 0.45 mm nozzle, with a 100% infill density and a 50 mm

C for the 0.45 mm nozzle, with a 100% infill density and a 50 mm  s

s printing speed. The bed temperature was kept at 45

printing speed. The bed temperature was kept at 45  C.

C.

B. Static Magnetic Measurements

The static magnetic properties of the ferromagnetic MagS have been characterized toto. In particular, the magnetic hysteresis loops of the iron-PLA have been acquired using an Oxford Instruments 1.2H/CF/HT Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM), at the system temperature of 300 K and by varying the magnetic field strengths in the range  T.

T.

The findings are reported in Fig. 6 and have been used to fed the numerical simulations.

Fig. 6.

Measured magnetization (Am  kg

kg ) of the ferromagentic poly-lactic acid (PLA) as a function of the applied magnetic flux density (T).

) of the ferromagentic poly-lactic acid (PLA) as a function of the applied magnetic flux density (T).

C. Magnetic Hyperthermia Characterization

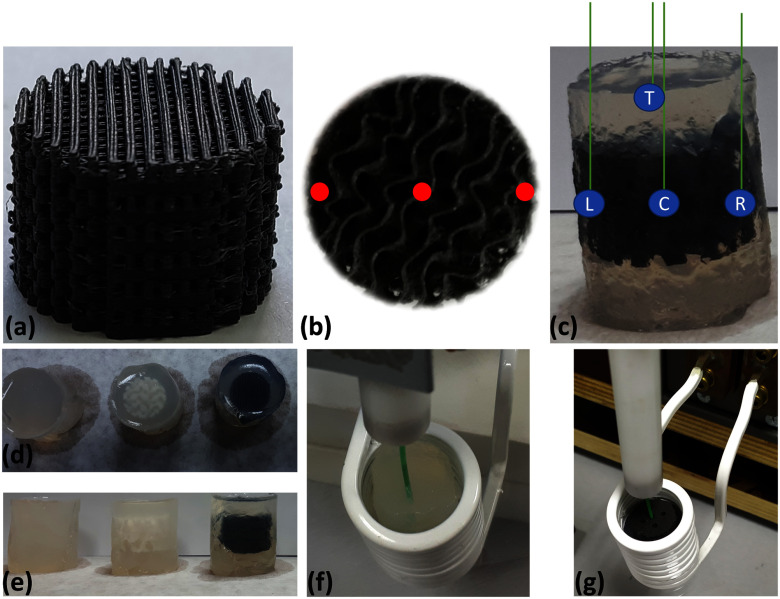

This work aims to specify the experimental steps on accurate measurement of heating efficiency of 3D printed MagS. To unravel this unexplored research field, an experimental protocol is depicted in Fig. 2. For 3D-printed MagS (Fig. 2(a)), conventional heating evaluation experimental approaches used on MNPs for MPH are not applicable. For this reason, a different methodological approach must be pursued. For MagS, three holes are opened from the top to the scaffold center, as shown with the red dots in Fig. 2(b). MagS are then placed in an agarose matrix to form a fluid surrounding mimicking the tissue environment and allowing the temperature probe (i.e., an optical fiber colored as green in Fig. 2(c), (f), (g)) to record the heat diffusion in four different positions (T - Top, L - Left, C - Center, and R - Right). The test gels have been prepared by mixing homogeneously, under magnetic stirring, the scaffolds with distilled water (50 ml in agarose concentration of 4 g  ml

ml ), at room temperature. The concentrations of gelling agents was 5.0 wt%. Similar samples of 3D printed PLA scaffolds and only agarose matrix (Fig. 2(e)) are the non-magnetic reference samples in this experimental procedure (Fig. 2(g)).

), at room temperature. The concentrations of gelling agents was 5.0 wt%. Similar samples of 3D printed PLA scaffolds and only agarose matrix (Fig. 2(e)) are the non-magnetic reference samples in this experimental procedure (Fig. 2(g)).

Heating efficiency under magnetic hyperthermia conditions is evaluated through calorimetric measurements using the Easyheat AC field induction heating system, provided by Ambrell, operating at the power of 2.4 kW and at a frequency of 400 kHz. The  product is 9.5

product is 9.5 Am

Am  s

s [68]. The applied magnetic flux density field intensity is 30 mT. The sample is deployed centered in the 8-turn induction heating coil with optical fibre placed in the corresponding positions (Fig. 5(f) and (g)). The magnetic field strength inside the coil has been measured by using a small coil probe having diameter of 7.3 mm, 2.5 turns, 3 cm of height. The coil has been placed inside the induction heating coil and connected with an oscilloscope to measure the peak-to-peak value of the electromotive force (in V) and convert it to H(kA/m) through the use of Faraday's law. The SAR is then estimated using (9). All samples' initial temperature (before turning the magnetic field on) was set at 19

[68]. The applied magnetic flux density field intensity is 30 mT. The sample is deployed centered in the 8-turn induction heating coil with optical fibre placed in the corresponding positions (Fig. 5(f) and (g)). The magnetic field strength inside the coil has been measured by using a small coil probe having diameter of 7.3 mm, 2.5 turns, 3 cm of height. The coil has been placed inside the induction heating coil and connected with an oscilloscope to measure the peak-to-peak value of the electromotive force (in V) and convert it to H(kA/m) through the use of Faraday's law. The SAR is then estimated using (9). All samples' initial temperature (before turning the magnetic field on) was set at 19  C, while coil cooling water temperature was kept stable during the procedure. Meanwhile, infrared (IR) camera (FLIR i3, FLIR Systems, USA) was used to have a global temperature recording of the experimental setup (i.e., not only sample's temperature), in order to control better possible non-magnetic heating losses and monitor the self-heating of the coil.

C, while coil cooling water temperature was kept stable during the procedure. Meanwhile, infrared (IR) camera (FLIR i3, FLIR Systems, USA) was used to have a global temperature recording of the experimental setup (i.e., not only sample's temperature), in order to control better possible non-magnetic heating losses and monitor the self-heating of the coil.

Fig. 5.

Preparation of (a) 3D printed magnetic scaffold (MagS) sample for magnetic hyperthermia experiment. (b) 3 symmetrical holes are opened to place the temperature probe-optical fiber in (c) three positions within the MagS and one background measurement. Control samples in agarose gel from (d) top and (e) side view. Heating evaluation experimental setup with (f) control and (g) MagS samples placed at the center of the induction heating coil with optical fiber (green).

V. Results

To evaluate the SAR of MagS the experimental setup shown in Fig. 5 and the methodology described in Section II.B have been used. The different temperature curves recorded during the magnetic hyperthermia test are shown in Fig. 7. From Fig. 7 it can be noticed that the highest temperatures are reached in the MagS center (C - black curve), as confirmed by the simulations. The difference between the simulated and measured values is due to the fact that, in silico, a homogeneous cylinder has been considered, whilst, in practice, MagS are heterogeneous and porous materials. The temperature dynamics in the measurement points R and L are quite similar between them, depsite the peak temperature is ∼2.5 °C lower than that measuered in the MagS center. The difference is due to the MagS architecture and its porosity, but also to the fact the probe is placed where the magnetic field is less homogeneous and the temperature is lower due to diminished deposited power (see Figs. 3 and 4). By relying on the findings form our numerical study, using only the temperature curves acquired in points L and R in (9) would result in a misleading estimation of the SAR value. Similarly, the temperature records at the MagS top (T - fuchsia curve in Fig. 7) and  1 cm outside the sample volume in the agar (O - green curve in Fig. 7) have a lower peak temperature value. This is due to the fact that lower values of magnetic field strenght and homogeneity are found at this location (see Fig. 3). Furthremore, for these probe locations, by observing the initial slope of the temperature vs. time curve, a clear decrease in the

1 cm outside the sample volume in the agar (O - green curve in Fig. 7) have a lower peak temperature value. This is due to the fact that lower values of magnetic field strenght and homogeneity are found at this location (see Fig. 3). Furthremore, for these probe locations, by observing the initial slope of the temperature vs. time curve, a clear decrease in the  must be noticed (Fig. 7). The different heat diffusion regime strongly affects the sape of the curve and can strongly impact on the final estimated SAR value. These findings are of relevance for cases in which the MagS is made of fragile or very hard material and the probe cannot be inserted in the sample volume to properly investigate the heating dynamics in the biomaterial volume (Table I). Furthermore, the numerical and experimental findings shine a light on the variability of the results reported in Table I.

must be noticed (Fig. 7). The different heat diffusion regime strongly affects the sape of the curve and can strongly impact on the final estimated SAR value. These findings are of relevance for cases in which the MagS is made of fragile or very hard material and the probe cannot be inserted in the sample volume to properly investigate the heating dynamics in the biomaterial volume (Table I). Furthermore, the numerical and experimental findings shine a light on the variability of the results reported in Table I.

Fig. 7.

Expeirmental temperature curves acquired in four different position (T = Top, C = Center, R = Right, L = Left) in the magnetic scaffold (MagS) and in the agarose phantom (O = Out). The simulated counterparts are reported in lighter colors. The shaded red area represents the typical temperature range for hyperthremia treatment.

The considerations done for the temperature curves are fundamental for the SAR estimation. Indeed, if the temperature curve in the agar phantom is considered, an SAR of  1 W/g is found for the MagS considered in this study. On the other hand, if the temperature curves acquired inside the MagS (i.e., C, R, L, T) are used to compute an average SAR, so that (9) is modified in

1 W/g is found for the MagS considered in this study. On the other hand, if the temperature curves acquired inside the MagS (i.e., C, R, L, T) are used to compute an average SAR, so that (9) is modified in

|

a value of 1.2  0.2 W/g is found. In (10),

0.2 W/g is found. In (10),  is the number of temperature curves, while the other symbols retain their usual meaning. This value is in agreement to the SAR value reported in [51] and [50] for MagS with similar architecture, weight and properties. Here, it is necessary to report a noticeable 20% SAR variation. As a matter of fact, from our analysis and from our findings, the SAR values reported in Table I could not be directly compared to the SAR values derived for our ferromagnetic PP scaffolds. Indeed, since the methodological details are missing for the MagS in Table I a fair comparison cannot be performed. Therefore, careful guidelines must be followed to obtain reliable and comparable results.

is the number of temperature curves, while the other symbols retain their usual meaning. This value is in agreement to the SAR value reported in [51] and [50] for MagS with similar architecture, weight and properties. Here, it is necessary to report a noticeable 20% SAR variation. As a matter of fact, from our analysis and from our findings, the SAR values reported in Table I could not be directly compared to the SAR values derived for our ferromagnetic PP scaffolds. Indeed, since the methodological details are missing for the MagS in Table I a fair comparison cannot be performed. Therefore, careful guidelines must be followed to obtain reliable and comparable results.

VI. Conclusion and Discussion

This work deals with the investigation of the experimental parameters and estimation methodology on the SAR of MagS for DST HT. In particular, this work thoroughly investigates through extensive numerical simulations the factors affecting the reliability of the measurements of MagS SAR. The SAR measurements of MagS are affected by i) the sample placement in the coil, ii) the magnetic field homogeneity, the temperature probe placement, and iv) the biomaterial architecture. Furthermore, we specify an experimental procedure to perform accurate measurement of heating efficiency of 3D printed MagS to reduce the influence of probe placement and the biomaterial archietecture. To unravel this unexplored research field and foster the design, characterization and evaluation of MagS as hyperthremia agents, the proposed experimental protocol could be adopted, as shared methodology, for the assessment of the heating potential of any innovative thermoseeds for DST treatment. In particular, how framework could be employed to evaluate the heating performances of ferromagnetic or superparamagnetic MagS. Future works will deal with the numerical and experimental investigation of how the geometric and architecture parameters of the MagS can affect the quality of the heating.

Acknowledgment

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Biographies

Matteo B. Lodi (Member, IEEE) received the bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy, in 2016, the master's degree in biomedical engineering from the Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, in 2018, and the Ph.D. (with Hons.) degree in electronic engineering and computer science from the University of Cagliari, in 2022.

He is currently an Assistant Professors with the Applied Electromagnetics Group, University of Cagliari. He was a Technologist. His research interests include modeling of bioelectromagnetic phenomena, especially hyperthermia treatment, the study, manufacturing, and synthesis of magnetic biomaterials for tissue engineering applications, and the use of microwaves for biotechnology and environmental applications, while working in the design and characterization of antennas for space and wearable applications.

He was the recipient of the Roberto Sorrentino Young Scientist Award in 2022 at the Italian URSI Assembly, Young Scientists at the General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of URSI in 2020 and 2021. He has been a member of the WG2: Better thermal-based EM therapeutics of the COST Action 17115 MyWave.

He has been appointed as the Chair of the IEEE Nanotechnology Council Young Professionals. He is a member of the Editorial Board of the IEEE Future Directions Technology Policy and Ethics Newsletter, Journal of Food Processing and Preservation and of the International Journal of RF and Microwave Computer-Aided Engineering, Frontiers in Antennas and Propagation, and Electronics (MDPI).

Antonios Makridis is currently a Postdoctoral Researcher. Being a member with MagnaCharta Group (magnacharta.physics.auth.gr) since 2010 resulted to his active participation to several projects related to magnetic nanomaterials and to his Ph.D. Thesis defense with title Magnetic Nanostructures and Nanomagnetism for Modern Biomedical Applications (defended on April 2019). As a material science and physics Researcher, he was with the synthesis of iron-based magnetic nanostructures and he has studied their use as agents in biological applications. He has authored or coauthored 20 manuscripts in peer-review journals. His research interests include chemical synthesis and characterization of diverse types of nanoparticles, either destined for specific applications or from sheer scientific curiosity. He is an Expert on standardizing and setting novel experimental protocols on modern nanoparticle applications. Since 2009, he has been a Reviewer of 19 international scientific journals.

Konstantina Kazeli received the graduation degree from the Physics Department, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece, and the master’s degree from the Medical Department, Democritus University of Thrace, Orestiada, Greece, in biomedical and molecular science in diagnosing and treating diseases with a thesis title? Antibacterial and oxidative stress study of bioceramic nanoparticles for bone regeneration. synthesis and characterization? She is currently working toward the Ph.D. degree. She is a member in MagnaCharta Group since 2020, as a Ph.D. candidate and Researcher with a dissertation title Synthesis and characterization of nanomagnetic bioceramics for biomedical applications. Her research interests include synthesis of innovative magnetic-bioceramic nanoparticles, in order to achieve the best possible biological efficiency and to expand the huge potential of multifunctional nanocomposites and scaffolds in the field of nanomedicine as multifunctional biomedical agents combining diverse therapeutic results in tumor treatments, bone regeneration, magnetic hyperthermia and drug delivery.

Theodoros Samaras (Member, IEEE) received the M.Sc. degree in medical physics (with distinction) from the University of Surrey, Guildford, U.K., and the Ph.D. degree from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. He joined the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he was involved in the computational dosimetry of electromagnetic fields. He later moved to the Erasmus Medical Centre of Rotterdam, where he worked on the quality assurance of superficial microwave hyperthermia with a Marie-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship from the European Commission. In December 1999, he returned to the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, where he is currently a Professor in bioelectromagnetics. His research interests include numerical techniques and computational multiphysics modeling with applications in biomedical technology and the safety of electromagnetic fields.

Makis Angelakeris received the Ph.D. degree in magnetic nanostructures from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, in 2000. He is currently a Professor with the School of Physics of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Since 2000, he has been involved in biomedical applicability schemes of magnetic nanostructures, such as magnetic particle hyperthermia and magnetomechanical actuation. He is the Group Leader of MagnaCharta Group. He has authored or coauthored 133 manuscripts in peer-review journals and received 3395 citations by 2424 document (Scopus 12/2021). His research interests include magnetic nanostructures initiating from synthesis of magnetic multilayers and magnetic nanoparticles and corresponding magnetic characterizations including static and dynamic magnetic measurements.

Giuseppe Mazzarella (Senior Member, IEEE) received the Laurea degree (summa cum laude) in electronic engineering from the Università Federico II of Naples, Naples, Italy, in 1984, and the Ph.D. degree in electronic engineering and computer science, in 1989. In 1990, he became an Assistant Professor with the Dipartimento di Ingegneria Elettronica, Università Federico II of Naples. Since 1992, he has been with the Dipartimento di Ingegneria Elettrica ed Elettronica, Università di Cagliari, first as an Associate Professor and then, since 2000, as a Full Professor, teaching courses in electromagnetics, microwave, antennas, and remote sensing. He is the author or coauthor of more than 100 papers in international journals and a reviewer for many EM journals. His research interests include efficient design of large arrays of slots, power synthesis of array factor, with emphasis on inclusion of constraints, microwave holography techniques for the diagnosis of large reflector antennas, use of evolutionary programming for the solution of inverse problems, in particular problems of synthesis of antennas and periodic structures.

Alessandro Fanti (Senior Member, IEEE) received the Laurea degree in electronic engineering and the Ph.D. degree in electronic engineering and computer science from the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy, in 2006 and 2012, respectively. From 2013 to 2016, he was a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Electromagnetic Group, University of Cagliari, where he is currently an Assistant Professor. He has authored or coauthored 63 articles in international journals. His research interests include numerical techniques for modes computation of guiding structures, optimization techniques, analysis and design of waveguide slot arrays, analysis and design of patch antennas, radio propagation in urban environment, modeling of bioelectromagnetic phenomena, and microwave exposure systems for biotechnology and bioagriculture. He is an Associate Editor for the IEEE Journal of Electromagnetics, rf and microwaves in medicine and biology. Since 2020, he has been a Principal Investigator of the IAPC Project, funded with e five million by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development (MISE), within the AGRIFOOD PON I&C during 2014–2020 (CUP: B21B1900064008 COR: 1406652).

Open Access funding provided by ‘Universit? degli Studi di Cagliari’ within the CRUI CARE Agreement

Funding Statement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the EuropeanUnion - NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University andResearch under PNRR - M4C2-I1.3 Project PE 00000019 “HEALITALIA” to Alessandro Fanti and Matteo Bruno Lodi CUP F53C22000750006 University of Cagliari. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors onlyand do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the EuropeanCommission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Contributor Information

Matteo B. Lodi, Email: matteob.lodi@unica.it.

Antonios Makridis, Email: anmakrid@physics.auth.gr.

Konstantina Kazeli, Email: kazeli.konstantina@gmail.com.

Theodoros Samaras, Email: theosama@auth.gr.

Makis Angelakeris, Email: agelaker@auth.gr.

Giuseppe Mazzarella, Email: mazzarella@diee.unica.it.

Alessandro Fanti, Email: alessandro.fanti@diee.unica.it.

References

- [1].Miller K. D. et al. , “Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics 2016,” CA: A Cancer J. Clinicians, vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 271–289, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Skandalakis G. P. et al. , “Hyperthermia treatment advances for brain tumors,” Int. J. Hyperthermia, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 3–19, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kuo I. et al. , “Potential enhancement of host immunity and anti-tumor efficacy of nanoscale curcumin and resveratrol in colorectal cancers by modulated electro-hyperthermia,” BMC Cancer, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Datta N. R., Kok H. P., Crezee H., Gaipl U. S., and Bodis S., “Integrating loco-regional hyperthermia into the current oncology practice: SWOT and TOWS analyses,” Front. Oncol., vol. 10, 2020, Art. no. 819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hurwitz M. and Stauffer P., “Hyperthermia, radiation and chemotherapy: The role of heat in multidisciplinary cancer care,” Seminars Oncol., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 714–729, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Oei A. et al. , “Molecular and biological rationale of hyperthermia as radio-and chemosensitizer,” Adv. Drug Del. Rev., vol. 163, pp. 84–97, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kok H. P. et al. , “Locoregional peritoneal hyperthermia to enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis: A simulation study comparing different locoregional heating systems,” Int. J. Hyperthermia, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 76–88, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee S.-Y., Fiorentini G., Szasz A. M., Szigeti G., Szasz A., and Minnaar C. A., “Quo vadis oncological hyperthermia (2020)?,” Front. Oncol., vol. 10, 2020, Art. no. 1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Izadifar Z., Izadifar Z., Chapman D., and Babyn P., “An introduction to high intensity focused ultrasound: Systematic review on principles, devices, and clinical applications,” J. Clin. Med., vol. 9, no. 2, 2020, Art. no. 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang J. et al. , “Gold nanobipyramid-loaded black phosphorus nanosheets for plasmon-enhanced photodynamic and photothermal therapy of deep-seated orthotopic lung tumors,” Acta Biomaterialia, vol. 107, pp. 260–271, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kok H. P. et al. , “Heating technology for malignant tumors: A review,” Int. J. Hyperthermia, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 711–741, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Baskaran D. and Arunachalam K., “Design and experimental verification of 434 MHz phased array applicator for hyperthermia treatment of locally advanced breast cancer,” IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag., vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 1706–1715, Mar. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stauffer P. R. et al. , “Observations on the use of ferromagnetic implants for inducing hyperthermia,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. BME-31, no. 1, pp. 76–90, Jan. 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]