Abstract

Most available data evaluating childhood cancer survivorship care focus on the experiences of high-income Western countries, whereas data from Asian countries are limited. To address this knowledge deficit, we aimed to characterize survivorship care models and barriers to participation in long-term follow-up (LTFU) care among childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) and health care providers in Asian countries. Twenty-four studies were identified. Most institutions in China and Turkey adopt the oncology specialist care model, whereas in Japan, India, Singapore, and South Korea, after completion of therapy LTFU programs are available in some institutions. In terms of survivor barriers, findings highlight the need for comprehensive age-appropriate education and support and personalized approaches in addressing individual preferences and challenges during survivorship. Health care professionals need education about potential late effects of cancer treatment, recommended guidance for health surveillance and follow-up care, and their role in facilitating the transition from pediatric to adult-focused care. To optimize the delivery of cancer survivorship care, efforts are needed to increase patient and family awareness about the purpose and potential benefits of LTFU care, improve provider education and training, and promote policy change to ensure that CCSs have access to essential services and resources to optimize quality of survival.

INTRODUCTION

Survival rates for pediatric cancers have improved dramatically over the past 5 decades.1 By 2040, this population will reach an estimated 580,000 childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) in the United States alone, and long-term survivor populations are similarly emerging globally.2 This progress has led to a rapidly increasing population of long-term CCSs who are highly vulnerable to adverse outcomes from cancer treatment-related late effects.3 Health problems related to cancer treatment that emerge during therapy and persist (long-term) or develop five or more years after completion of therapy (ACT) (late-onset) may include impairment of growth and development (both physical and intellectual), organ dysfunction, risk of subsequent neoplasms, and deficits in many aspects of psychosocial functioning and quality of life.3,4 Multimorbidity from cancer treatment effects are common and can adversely affect quality and duration of survival after pediatric cancer.3 Hence, addressing the health challenges experienced by CCSs is essential for enhancing their long-term well-being.

Risk-based care, which considers personal health risks associated with cancer and its treatment, is recommended for all survivors to facilitate early detection and opportunities for intervention to remediate or prevent long-term and late-onset effects (termed late effects hereafter).4,5 This approach is facilitated by clinical practice guidelines6-8 and various survivorship care models.9 Although several cooperative groups have published exposure-based health surveillance recommendations for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer,6-8 their feasibility of implementation across global settings has not been established. Similarly, models of survivorship care vary widely on the basis of differences in culture and health care systems and resources.9

Among pediatric oncology centers in high-income countries (HICs), most CCSs have access to long-term follow-up (LTFU) care by their primary oncology team or a dedicated LTFU clinic, but these services are often age-restricted requiring a transition of care during adulthood.10 In some centers, pediatric survivors can transition their care to LTFU programs serving adolescents and young adults, which provide some continuity of care within a cancer center.10 Shared care between oncology and primary care providers has been promoted as the ideal model of care but may not be feasible in practice settings lacking a strong primary care infrastructure.11,12 After CCSs leave pediatric cancer programs, reports largely from HICs indicate that few survivors receive risk-based follow-up care that addresses their unique cancer-related health risks.13-16 These deficits persist despite efforts to educate both survivors and health care providers (HCPs) about cancer treatment-related morbidity associated with childhood cancer.17-19

Research suggests that survivors who attend LTFU care programs have better long-term physical and psychosocial health outcomes than nonattendees.20 However, survivors experience numerous barriers that can challenge adherence to participation in care, including lack of awareness about risks of late effects, fear of transitioning from oncology providers, and financial or geographical constraints in accessing care.21,22 Similarly, both oncology and primary HCPs may be unfamiliar with cancer-related health risks and recommended exposure-based health surveillance and the complexities of the health care system may challenge delivery of LTFU care.23-25

According to a report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Asia shares the largest proportion of the global childhood cancer burden and accounts for approximately 50% of all cases worldwide.26 The improving survival rates of childhood cancer in Asia imply that the number of CCSs will increase in the coming decades. Most available data focusing on childhood cancer survivorship care are from HICs, whereas clinical data from Asian populations that address surveillance and management of long-term side effects in this population are limited. This literature review aimed to characterize models of survivorship care and identify barriers to adherence to LTFU care among survivors in Asian countries and key areas for future action.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.27 We developed a strategy to search PubMed and Web of Science to identify articles published between database inception and May 31, 2023. The scope of our review focused on survivorship care, including different models of care, survivorship care resources, and barriers to survivorship care. Search terms included CCSs (eg, “childhood cancer survivors,” “pediatric cancer survivorship,” “adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of childhood cancer,” and “adult survivors of childhood cancer”), models for delivering survivorship care, and implementation outcomes (eg, “barrier,” “challenges,” “priorities,” “practices,” “influencing,” “identification,” “guideline,” “recommendation,” “optimizing”). Eligibility criteria included studies that (1) were published in English; (2) focused on survivors of childhood cancer, defined as those diagnosed with cancer between age 0 and 18 years and had completed treatment during the time of assessment for complications; (3) were conducted in Asia, and (4) reported survivorship clinical practices. Bibliographies from publications meeting eligibility criteria were reviewed to identify additional relevant citations. We excluded (1) case reports, (2) studies focused on acute oncology care, and (3) those limited to descriptions of late effects. J.C. performed the initial screening of titles and abstracts. All authors participated in the full-text review of identified publications. J.C. and M.M.H. abstracted data about care models and barriers to LTFU care. Y.T.C. provided a third level of review to adjudicate discrepant categorizations.

We adopted the United Nations Geoscheme for Asia for categorization of studies, which included countries in Central Asia (eg, Uzbekistan,28 Kazakhstan29), Eastern Asia (eg, China, Japan, South Korea), Southeast Asia (eg, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore), Southern Asia (eg, India, Nepal, Pakistan), and Western Asia (eg, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey).30

RESULTS

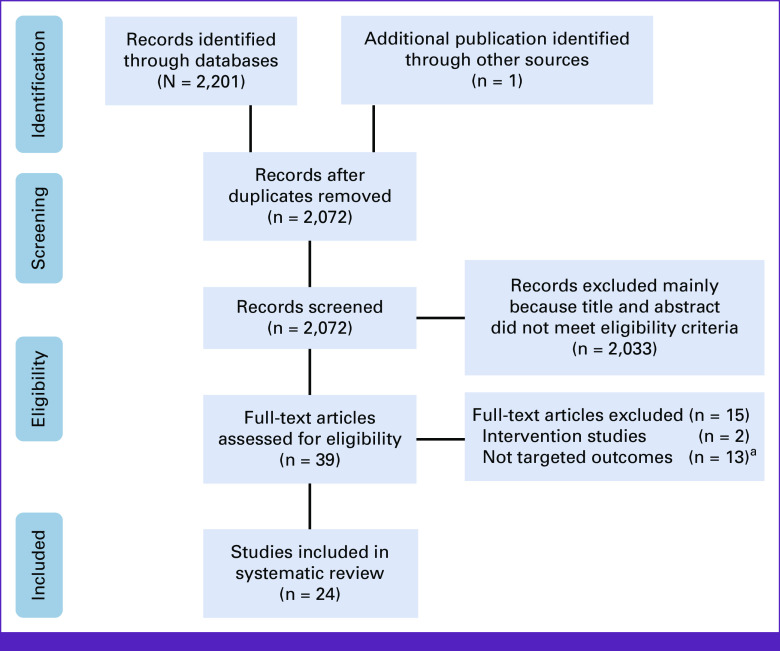

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart for the study screening process. We initially identified 2,202 articles. After removal of duplicates and initial screening of titles and abstracts, 39 articles remained for full-text assessment of which 23 met the inclusion criteria. One additional publication was identified from the references of the selected papers resulting in a total of 24 publications that described models of survivorship care and/or perspectives and preferences for survivorship care in seven countries/regions (China, Japan, India, Israel, Singapore, South Korea, and Turkey).

FIG 1.

PRISMA flowchart. aNot targeted outcomes refer to studies that described childhood cancer outcomes but not childhood cancer survivorship clinical practices in Asia. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.

Models of Survivorship Care

Among eight studies that described survivorship care models,9,31-37 only three provided sufficient details to characterize the model of care and services.33-35 Characteristics of selected programs are summarized in Table 1 in alphabetical order by United Nations Geoscheme for Asia.30 Established in 1991, the ACT Clinic at Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai is the first LTFU program in India. The Tata ACT Clinic serves CCSs who are more than 2 years post-treatment. The specialized LTFU program at Tata offers holistic survivorship care including risk-based assessment for late effects and psychosocial assessment, extended beyond medical care to encompass psychosocial, financial, transportation, education, and career guidance. Their model incorporates a multidisciplinary team including pediatric oncologists, psychologists, social workers, and pediatric subspecialists using a mixture of clinical practice guidelines.34

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of LTFU Care in Selected Asian Countries

| Country | Center | Eligibility for Entry Into LTFU Services | Upper Age Limit for LTFU | Type of Providers Involved | Type of Services Offered | Model of Survivorship Care | Use of Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China37 | Chinese Children cancer group institutions | 5-10 years after treatment | 18 years in some institutions or not specified | Pediatric oncologists Multidisciplinary teams in few centers |

Late-effects screening | Oncology specialist care | No standardized guidelines |

| India33 | Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India | ≥2 years after treatment | Not specified | Multidisciplinary including pediatric oncologists, psychologists, social workers, pediatric subspecialists | Risk-based assessment for late effects and psychosocial assessment Holistic support including medical, psychosocial financial, transportation, education, and career guidance |

Specialized LTFU clinic | Mixture of clinical practice guidelines, not specified |

| India34,a | All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India | After completion of treatment, time not specified | Not specified | Multidisciplinary including pediatric oncologists, nurses, counselors, dieticians, and nongovernmental organization staff | Comprehensive medical, neuro-psychologic, and social evaluation Provision of bilingual after treatment completion Card |

Specialized LTFU clinic | Not specified |

| India34,a | Cankids Hospital Support Units and Cankids Care Centers | Completed treatment | Not specified | Not specified | Education about late effects Advocacy for survivorship clinics and services |

Not applicable | Not applicable |

| India34,a | Partnership In Cancer Survivorship Optimization (PICASSO) | Not specified | Not specified | Pediatric oncologist | Medical assessments and psychosocial care | Holistic rehabilitation module being implemented in pediatric cancer units | Not applicable |

| South Korea35 | Severance Hospital, South Korea | ≥2 years after treatment | Not specified | Not specified | Risk-based assessment for late effects Follow-up of disease status Psychological assessment |

Specialized LTFU clinic | Adopted/modified from COG, SIGN, UKCCSG clinical practice guidelines |

| Turkey32 | Pediatric oncology institutions registered in the Turkish Pediatric Oncology group | Not specified | From up to age 18 years to the end of life in different institutions. | Not specified | Not specified | Oncology specialist model (21 centers) Specialized LTFU clinic (one center) |

None of the centers used standardized, risk-based, survivor-focused guidelines. |

Abbreviations: COG, Children's Oncology Group; LTFU, long-term follow-up; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; UKCCSG, UK Children's Cancer Study Group.

Reference 34 provides an overview of multiple childhood cancer survivorship programs in India.

In New Delhi, India, the Pediatric Cancer Survivor Clinic in All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) offers LTFU care to patients who have completed therapy. The team, comprising pediatric oncologists, nurses, counselors, and dietitians, provides both acute oncology care and facilitates the transition from acute oncology care to survivorship care. AIIMS offers comprehensive medical, neuro-psychologic, and social evaluations in their specialized LTFU clinic.34

In South Korea, the LTFU clinic at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System was established in 2005 targeting individuals who had survived at least 2 years postcancer therapy.35 The LTFU clinic's primary focus areas include late effects follow-up, ongoing monitoring of disease status, and psychological assessment. Their follow-up protocol is adopted and modified from other published guidelines and tailored to be cost-effective and suitable for regional implementation.35

Two reports provided aggregated information about survivorship care obtained through national surveys.31,32 Kurosawa et al31 undertook a nationwide survey to characterize Japanese LTFU clinic operations for survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). They found that nearly two thirds (62%) of the participating centers had a LTFU clinic. Services more often focused on survivors of allogeneic versus autologous HCT. Most (92%) centers offered LTFU care without a specific termination point; most pediatric centers did not routinely refer survivors to adult programs for continued LTFU. Investigators from the Turkish Pediatric Oncology Group (TPOG) surveyed directors of 33 pediatric oncology centers to determine the current status of LTFU care for CCSs. Of 21 (64%) respondents of 33 active TPOG institutions, only one had a LTFU clinic independent of the oncology treatment clinic. None used LTFU guidelines to standardize survivorship care.32

Tonorezos distributed a survey to stakeholders from 18 countries to assess models of care from countries with varying levels of resources and health care systems.9 Representatives from four Asian countries participated including Israel, India, Japan, and Turkey. Findings, in addition to those previously noted from individual countries, included variations in national health care coverage, composition of LTFU staff, location of LTFU clinic location, source of LTFU guidelines, use of risk-stratified care delivery, and transition practices. The results across all of the countries that responded to the survey indicate that LTFU care resources are generally available for pediatric-aged survivors of childhood cancer with most having limited transition services when survivors reach adulthood. Asian survivorship programs endorsed that a large proportion of survivors receive LTFU care from providers who are not trained in managing late effects; however, this deficit was also reported by programs in several HICs.

Investigators from India are pursuing innovative models of service delivery led by not-for-profit organizations to address survivorship needs.34 Cankids, a national Indian society focused on Change for Childhood Cancer developed Cankids Passport2Life (P2L) to provide survivors with information about late effects risks and support their adherence to LTFU care. Cankids collaborates with treating hospitals that offer LTFU care to run P2L clinics and workshops and also conducts P2L clinics and workshops for survivors who do not have access to a hospital with a LTFU program or prefer not to return to a pediatric unit.

The Indian Cancer Society developed a holistic rehabilitation survivorship module called Partnership In Cancer Survivorship Optimization that is being implemented in partnership with pediatric cancer units.34 Hospital-based LTFU clinics perform medical assessments for late effects, and the Indian Cancer Society offers rehabilitation and psychosocial services with the goal of reducing nonadherence to LTFU care, improving survivor quality of life, and providing support networks for survivors. Such collaborations with nonprofit organizations are perceived to represent a means to extend access to survivorship care in centers with limited or no special services and resources, which represents a large portion of pediatric cancer centers in India.36

Finally, in a study evaluating priorities for harmonizing LTFU surveillance guidelines among pediatric cancer programs, Cheung et al37 reported that most institutions within the Chinese Children's Cancer Group adopt the oncology specialist care model, where follow-up care occurs in an oncology setting and is provided by the oncology treatment team. Late-effects screening of CCSs did not follow specific guidelines, motivating the objective of this study, but details about survivorship services within Chinese programs were not elaborated.

Perspectives and Preferences

Six Asian countries have conducted studies to understand survivors'/caregivers' or HCPs' perspectives about survivorship care including their preferences for and barriers to participation in LTFU care.31,32,36,38-53 Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of these studies in alphabetical and chronological order of countries/regions according to the United Nations Geoscheme for Asia.30

TABLE 2.

Barriers to LTFU Care After Childhood Cancer

| Country/Region | Study Population | Study Design | Objective | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China (Hong Kong)49 | 155 CCSs 45 caregivers (93% response rate) |

Cross-sectional structured questionnaire | To evaluate cancer-specific knowledge about diagnosis, treatment, and risk of late effects | 73.5% recalled diagnosis 88%-92% recalled major treatment modalities 45% recognized more than a quarter of late effects risks |

| China (Hong Kong)48 | 200 CCSs (94% response rate) | Cross-sectional structured questionnaire | To investigate factors associated with health behaviors To examine survivor expectations of a survivorship program |

67% reported ≥1 suboptimal practice of health-protective behaviors Late-effects screening (78%) and psychosocial services (77%) endorsed as essential components of a survivorship program |

| China (Taiwan)50 | 1,411 patients with cancer diagnosed before age 18 years | Review of claims data in national Longitudinal Health Insurance database | To investigate transition from pediatric to adult health care for patients with cancer in Taiwan's medical system | 98.1% received adult-oriented therapy before age 18 years while 1.9% received pediatric-oriented therapy during adolescence Age at the first visit significantly associated with adult-oriented care Significantly lower proportion of children receiving adult-oriented care in facilities designated superior in hospital accreditation and excellence in teaching hospital |

| India36 | 86 pediatric cancer centers (68.6% response rate) | Cross-sectional online survey | To evaluate survivorship care services in India | 91% provided survivorship care within routine oncology clinics, without upper age limit (61%) or time period limit (63%) for follow-up Barriers to participation in LTFU care: follow-up are distance, lack of knowledge, lack of adequate facilities, and patient priority for follow-up |

| India47 | 79 AYA survivors of childhood cancer | Semistructured interviews | To evaluate barriers to participation in LTFU among AYA CCSs | Survivor and caregiver barriers to participation in LTFU care: feeling well, competing demands related to school, work and family, increased time since treatment |

| Japan40 | 74 CCSs 40 caregivers (77% response rate) |

Cross-sectional survey | To assess socioeconomic status, knowledge about diagnosis, treatment, and late effects, and hospital attendance patterns | 75% recalled diagnosis 30% knew about late effects risks Reasons for not returning for LTFU included physician in charge advised that follow-up was not necessary and survivors thought that they were in good health. |

| Japan38 | 185 CCSs 72 siblings 1,000 general population controls (72% response rate) |

Cross-sectional survey | To evaluate medical visits of survivors compared with control groups | 95% visited a medical facility during previous year 29% had a treatment summary Previous oncology care hospitals were most commonly visited medical facilities (64%-74%) 67% endorsed preference for medical visits at previous treatment facility and 26% at a LTFU clinic |

| Japan42 | 533 pediatric oncologists (56% response rate) and 325 pediatric surgeons (32% response rate) from Japanese Society of Pediatric Oncology | Cross-sectional survey | To examine self-reported preferences and knowledge about health care needs of young adult CCSs among pediatric oncologists and surgeons | 62% of pediatric oncologists and 43% of surgeons responded correctly to vignettes about survivorship care Most shared information about cancer diagnosis with adults treated for childhood cancer Both groups endorsed the importance of Japanese-adapted LTFU guidelines and collaborations with adult-based general physicians for care transitions |

| Japan44 | 631 Japanese CCSs (age 15-26 years) in Heart Link mutual-aid health insurance 108 Canadian childhood cancer survivors (42.5% response rate) |

Cross-sectional survey | To examine transition barriers and facilitators in Japanese survivors and compare to those of survivors in Canada | Compared with Canadian survivors, Japanese survivors Showed greater preference for self-management (eg, access to care, medication management, medical insurance) Showed lower levels of expectation concerning adult care (eg, knowing cancer history, reminders before appointment, relationship with doctor) Preferred to see same doctor for LTFU care as adults |

| Japan43 | 30 CCSs (53% response rate) and 27 caregivers (47% response rate) returning for LTFU care | Cross-sectional survey | To determine survivor and family lifestyle, healthcare practices, understanding of late effects, and anxieties related to survivorship | 20%-30% of CCS survivors endorsed experiencing problems when receiving care at facility other than cancer treatment facility Fewer survivors (33%) compared with caregivers (67%) knew about late effects Both groups had comparable levels of anxiety related to challenges associated with survivorship |

| Japan31 | 271 HCT centers (189 adult and 82 pediatric) from national transplant registry database (69% response rate) | Cross-sectional survey | To characterize LTFU clinic operations in Japan | 62% reporting having a LTFU clinic Lack of human resources (especially nurses) was most frequent reason for not operating a LTFU clinic 92% did not have age or time criteria for terminating LTFU 56% recommended continuing LTFU care 5 years after transplant 75% of pediatric centers did not routinely refer survivors to an adult HCT center for LTFU care |

| Japan46 | 183 councilors (137 institutions) of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology (95% response rate) | Cross-sectional survey | To ascertain the current status of transitional care in childhood and AYA cancer survivors | 91% endorsed experience in medical care for cancer patients and 63% with experience in transitional care 43.5% of institutions had a LTFU clinic but only 7.6% had transition support programs or support Despite 89% reporting access to adult clinics, the number of patients referred to adult clinics was small Barriers to providing survivorship care: staff and time shortages, lack of definition of staff roles, insufficient knowledge about cancer and therapy, differences in patient physician relationships in pediatric and adult clinics, insufficient information about late effects, and lack of clinical experience Patient-related barriers: need to manage multisystem morbidity, financial burdens, time-related burdens, lack of awareness regarding health-related issues, and failure to recognize importance of LTFU |

| Japan39 | 1,305 specialists (192 pediatric and 1,109 adult) from Japanese cancer-related professional societies | Cross-sectional internet survey | To investigate the medical care of AYA adult cancer patients To compare approaches toward AYA cancer care by pediatric and adult cancer specialists |

Providers endorsed importance of multidisciplinary collaboration among pediatric and adult specialists For pediatric cancer AYA survivors, 34.9% of pediatric specialists and 36.2% of adult specialists preferred transition to corresponding adult medicine department Only 2.4%-5.3% of specialists considered that primary care physicians would serve as primary clinicians for AYA survivors |

| Japan41 | 121 CCSs (69.4% response rate) | Cross-sectional survey | To identify factors responsible for discontinuing LTFU To define the support needs of CCSS |

80% reported late complications LTFU decreased over time related to provider reasons (35.6%, eg, electively discontinued after 5 years) and patient reasons (64.4%, eg, not experiencing problems) Survivors endorsed need for support for financial and medical expenses (29.8%), assistance in returning to work (26.2%), and improvement of societal understanding of survivorship challenges (22.6%) Survivors related need for a treatment summary and peer support tailored to the different stages of life |

| Singapore51 | 23 AYA cancer survivors (diagnosed 16-39 years) and 18 health care providers | Focus group discussions | To explore perceptions of survivorship services in Singapore To propose service design and delivery strategies |

AYA survivors perceived that currently available care fails to address needs of their needs Preferred services: age-specific services addressing employment challenges, introducing care navigators to assist with challenges across cancer care continuum Implementation strategies proposed: provider training on communication techniques with AYA, leveraging social media platforms to promote health information and publicity, consolidating services from multiple providers |

| South Korea52 | 680 parent caregivers of CCSs | Cross-sectional survey | To investigate satisfaction with survivorship care and preferences for survivorship care provider | 80% recognized that shared care promotes health of survivors 68.7%-90.9% preferred oncologists to provide follow-up care of primary cancer than primary care physicians Caregivers with multiple comorbidities and higher fear of cancer recurrence endorsed preference for oncology v primary care providers |

| Turkey32 | 33 pediatric oncology centers in the Turkish Pediatric Oncology Group (TPOG) (64% response rate) |

Cross-sectional survey | To determine the current status and challenges of LTFU for CCSs at pediatric oncology institutions in Turkey | Only one center had a separate LTFU clinic independent of acute care Most centers provided LTFU care at the acute care pediatric oncology outpatient clinic None used standardized, risk-based, survivor-focused guidelines Challenges in LTFU care: difficulty in the pediatric to adult care transition, insufficient care providers, and insufficient time and transportation problems |

| Turkey53 | 16 survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Semistructured, in-depth interviews | To explore adolescent survivors' views and expectations about LTFU care | Survivors endorsed need for psychosocial support related to self-esteem, body image, school, peer relations, and social activities Survivors identified school absence and limitations in participation in social activities as barriers to LTFU care Survivors recognized health promotion as potential benefits of LTFU care |

| International45 | 58 medical specialists (67.2% pediatric oncologists) | Cross-sectional survey | To explore priorities and perspectives for survivorship care and research | 48.3% respondents from Asia and 39.7% from Europe/North America LTFU care priorities: physical care (35.9%-39.3%), multidisciplinary providers and transition support (26.0%-29.4% ≤18 years) Asian clinicians primarily prioritized physical care aspects of follow-up care, whereas European/North American clinicians prioritized health care structure Obstacles to LTFU care are lack of financial resources, workforce, knowledge of importance of LTFU, cooperation, time, support by the hospital, communication with primary care and difficulties in reaching survivors |

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adult; CCSs, childhood cancer survivors; CCSS, Childhood Cancer Survivor Study; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; LTFU, long-term follow-up.

Survivor/Caregiver Perspectives and Preferences

Studies targeting survivors and caregivers largely involved cross-sectional surveys administered to convenience samples of survivors and caregivers during clinic visits or via online platforms.32,36,41-46,48,49,52 Two studies that focused on AYA survivors used qualitative methods such as semistructured interviews47 and focus group discussions.51

Across all studies from Asian countries, themes identified related to potential barriers to adherence to participation in LTFU care included knowledge deficits (about cancer diagnosis, cancer treatment, risk of late effects),40,43,49 lack of endorsement of need for LTFU care by the treating physician,40 perception that LTFU was not necessary because they felt well and were not experiencing problems,40,41,47 and competing demands related to school, work, or family.47,53

Despite these challenges with adherence to LTFU care, a few studies supported that survivors and their caregivers have strong preferences about survivorship care and services that could benefit them. In a survey examining expectations of a survivor program, Cheung et al48 reported that 78.5% and 77.0% of CCSs from Hong Kong advocated for late-effects screening and psychosocial services to address psychological distress, respectively, as essential components of a survivorship program. In another study, Japanese CCSs endorsed need for support of financial and medical expenses (29.8%); assistance in returning to work (26.2%); and improvement of societal understanding of survivorship challenges (22.6%), especially related to employment.41 Finally, leukemia survivors from Turkey had similar perceptions about the need for assistance to address psychosocial challenges during survivorship.53

Several studies examined health care utilization patterns among CCSs.38,41,43,44,50 Terada et al41 observed a decline in LTFU evaluations among Japanese survivors, but most respondents (86.9%) appreciated the need for a treatment summary and explanation of late complications by a physician. Japanese survivors in other studies expressed preference to have LTFU evaluations at their previous treatment facility38 or with their treating oncologist,44 with 20%-30% of Japanese survivors and caregivers in a study by Iwai et al43 reporting they experienced problems when receiving care at a facility other than where they received cancer treatment. In a survey evaluating preferences for survivorship care among Korean caregivers of CCSs, oncologists were perceived as the preferred provider for management of late effects (88.5%), and screening for second primary cancers than primary care physicians (68.7%).52 Finally, two studies evaluated aspects of care transitions among CCSs in Japan44 and Taiwan, China.50 In the study by Ishida et al,44 Japanese CCSs survivors endorsed lower levels of expectation-related topics relevant to adult care transition (eg, knowing cancer history, reminders before appointment, relationship with doctor) compared with Canadian CCSs. Jin et al highlighted health care system factors that affected receipt of care in adult- versus pediatric-oriented settings in Taiwanese CCSs.50

HCP Perspectives and Preferences

Most studies evaluating HCP perspectives and preferences related to LTFU care for CCSs used online surveys of HCPs identified through cooperative groups or professional society affiliations.31,36,39,42,45,46 The exception was the study by Ke et al51 that included HCPs in the focus group discussions exploring AYA cancer survivors' preferences for services. These studies highlighted perspectives of multidisciplinary survivorship HCPs including pediatric oncologists, surgeons, transplanters, endocrinologists, and other pediatric and medical subspecialists.

Across all studies from Asian countries, HCPs reported potential barriers to delivery of LTFU care including knowledge deficits (about oncology history [among nononcology specialists], late effects, and recommended health surveillance),32,36,42,45,46 lack of experience with survivorship care, especially with management of survivors with multisystem morbidity,46 lack of resources (time, personnel, adequate facilities),32,36,45 lower priority for survivorship versus acute oncology care,36 and suboptimal communication among providers.45

Related to communication, the culturally relevant issue of truth telling about a cancer diagnosis was explored among HCPs in the Japanese Society of Pediatric Oncology as a potential barrier to participation in LTFU care.42 Survey results in this study demonstrated variability in the proportion of pediatric oncologists (70%) and pediatric surgeons (62%) who disclosed information about a cancer diagnosis to adult survivors of childhood cancer, but overall, 80%-100% of respondents reported truth telling.

Several studies reported the need for improving access to resources and infrastructure to support the delivery of survivorship care and care transitions from acute oncology to LTFU and primary care. Physicians in the Japanese Society of Pediatric Oncology and TPOG endorsed the importance of nationally adapted LTFU guidelines.32,42 Other investigators observed that inadequate attention to survivorship care transitions resulted in survivors struggling to find informed providers, particularly during the transition from pediatric- to adult-focused care or dropping out of LTFU care altogether.39,45 The lack of standards-for-care transitions, differences in the patient-physician relationship in pediatric versus adult clinics, and suboptimal collaboration among multidisciplinary providers were perceived to contribute to ongoing transition challenges.46 To overcome these challenges, Ke et al proposed introducing care navigators to guide AYA survivors during these transitions.51

DISCUSSION

This review identified various models of childhood cancer survivorship care in Asia, with the oncology specialist care representing the most prevalent model followed by dedicated LTFU programs9,31-37 staffed by multidisciplinary providers that offer services including risk-based surveillance for late effects and psychosocial support. Barriers to adherence to pediatric cancer LTFU care in Asian exist at the patient/caregiver40,43,49 and HCP level32,36,42,45,46 with knowledge deficits about cancer-related adverse outcomes and the potential benefits of LTFU services common to both. In addition to knowledge deficits, survivors and caregivers endorsed practical and financial challenges that reduced priority for participation in care.40,41,47,53 Similarly, HCPs related that lack of time, resources, and personnel limited their ability to offer LTFU services.32,36,45 Study findings provide important information to guide the development of LTFU programs that are valued, culturally appropriate, and feasible to implement.

Studies from HICs have described models of survivorship care, including models led by primary care providers, care shared between oncology specialists and primary care providers, and care led by oncology nurses.1,11,54 However, several barriers impede implementation of such care models in Asia. For example, the shared-care model or community generalist model was endorsed as challenging by HCPs in Japan38,39,42,46 and Turkey32 because of lack of communication and referral pathways between oncologists and primary care providers. HCPs involved in survivorship care also varied regionally, with many lacking expertise to address the medical and psychosocial consequences of childhood cancer. Generally, the most feasible care model used in a given region depends on patient-level factors (such as risk of late effects, individual preferences, and capacity to self-manage), the availability of local medical and psychosocial services, and health care infrastructure and policy to support delivery of such services. As with HICs, future work is needed to identify effective and sustainable survivorship care models and create recommendations and metrics for evaluation of successful transitional care for CCSs across Asian countries with diverse health care systems and resources.

Findings from this review emphasize the need for survivor/caregiver educational programs to improve their knowledge about late effects, benefits of participation in LTFU care, and methods of risk mitigation. These programs must first address cultural barriers to disclosing the diagnosis of childhood cancer to patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Chinese49 and Japanese42 studies support that some survivors, albeit declining in prevalence from previous years,55 remain unaware of their diagnosis. More frequently observed were knowledge deficits about late effects of cancer treatment, which were endorsed by survivors and/or caregivers in many of the countries/regions represented in our review, regardless of the country's income level.23-25,32,36,42,45,46 These results align with earlier reports from HICs observing lack of awareness of past cancer diagnosis and treatment56,57 and late effects58 among CCSs. More recent studies suggest that disclosure of a cancer diagnosis is a standard of care in HICs, but knowledge deficits about late effects risks among survivors across the globe remain prevalent.59,60

Providing personalized education and support is important to address individual survivor preferences and challenges especially as they transition from oncology care. Some programs use the cancer treatment summary and survivorship care plan33,34 as a means to educate survivors about their personal health history and risks and promote their participation in LTFU care.17,61 Among Children's Oncology Group (COG) affiliated practices, 88% provide a treatment summary to survivors with more highly resourced programs organizing a more detailed care plan.10,61 Among Asian pediatric cancer programs, the results of our review suggest that few programs routinely use these tools.33,34

However, in some settings, survivors and their families may benefit from additional support other than the provision of a personalized survivorship care plan. Indeed, intervention trials implemented in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) demonstrated superior adherence to cardiomyopathy18 and breast cancer19 surveillance among survivors receiving motivational interviewing and psychosocial support in addition to a survivorship care plan. These strategies may be useful in addressing the behavioral and practical barriers to participation in LTFU care endorsed by Asian CCSs such as fear of transition, competing demands of family, school, and work, and the financial burden of traveling and paying for LTFU care.47,53 Emerging evidence also suggests the important role that patient navigators can play in the journey of a patient with cancer through education, support, and assistance in accessing resources from both within and outside the health care system.62 A recent review suggests that patient navigation interventions can effectively enhance accessibility and continuity of care and adherence to surveillance appointments.62 The development of accredited training programs in Asia may help to promote the role of childhood cancer–specific patient navigators in survivorship care.

Studies evaluating HCPs perspectives and preferences related to survivorship care highlighted knowledge deficits about late effects and recommended surveillance measures as well as lack of training and resources to support implementation of LTFU care.32,36,45,46 This scenario is not exclusive to Asia as similar knowledge deficits about late effects risks and surveillance recommendations were prevalent in studies of pediatric oncologists,23 general internists,24 and family physicians25 from HICs despite the availability of evidence-based survivorship guidelines and survivorship resources through cooperative groups (COG),63 professional oncology societies (ASCO),54 and nonprofit oncology advocacy (National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society) groups. In addition, HCPs endorsed time and resource limitations that reduced priority for survivorship care compared with acute oncology care.32,36,45 These factors also challenge implementation of survivorship care in HICs. For example, Essig et al64 observed variability in the availability of survivorship care across European regions ranging between 9% and 83%, with barriers including lack of time, resources, personnel, and funding. Collectively, these findings suggest the need for global efforts to improve HCP access to readily available resources to facilitate CCSS care.

The COG and the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group provide exposure-based recommendations for screening of long-term side effects for survivors of childhood cancer to support risk-based survivorship care.7,63 This review identified the need for nationally adapted guidelines as have been developed in HICs.32,42 The diversity of languages, cultures, and health care systems in Asia requires collaboration with local hospitals, clinics, and health organizations to adapt and translate these evidence-based guidelines into culturally appropriate surveillance recommendations and educational resources to other countries. Specific to the childhood cancer survivorship landscape in Asia, it is important to recognize that duplication of efforts to develop country or institution guidelines is not necessary as many authoritative and comprehensive recommendations for LTFU care and late effects screening are already in place.6,7 However, more work is needed to create resource-stratified, evidence-based guidelines to guide the implementation of these recommendations in global settings. Such consensus and recommendations will assist policy makers and stakeholders to identify effective and sustainable transition models for CCSs on the basis of the unique resources and settings of each country.

This review is subject to the following limitations. First, on the basis of the limited currently available studies, it was difficult to characterize models of survivorship care across Asia. Furthermore, we were not able to assess other variables that may influence access to survivorship care. For example, socioeconomic factors are powerful determinants of health-related outcomes. Finally, our systematic review found no data for many Asian countries, although this may be attributable to the inclusion of only studies written in English because it is methodologically difficult to conduct search and translation processes for literature written in the multiple languages represented in Asia.

In summary, to optimize delivery of high-quality pediatric cancer survivorship care in Asia, efforts to increase patient and family education, improve provider education and training, and promote policy change to ensure access to survivorship services are essential. Unfortunately, not all pediatric oncology programs have designated survivorship programs, guidelines, or sufficient dedicated staff to address the unique needs of long-term CCSs. Barriers to survivorship care are numerous and include knowledge deficits among survivors about late effects and benefits of follow-up, distance to survivor clinics, lack of access to a treatment summary, and fear of transitioning care from the pediatric oncology center. For providers, improving knowledge and access to resources to support survivorship care represent the primary challenges. This review provides important information to guide the development of interventions and resources for CCSs and HCPs in Asia to support their participation in LTFU care.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by the Master of Science in Global Child Health Program from St Jude Children's Research Hospital Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, USA, The Shanghai Health Commission Clinical Research Project (202140161) and Shanghai Pudong New Area Science and Technology Development Fund Livelihood Scientific Project (PKJ2021-Y43), China. Dr M.M.H is supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Melissa M. Hudson

Collection and assembly of data: Jiaoyang Cai, Melissa M. Hudson

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Melissa M. Hudson

Employment: Consolidated Medical Practices of Memphis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Oncology Research Information Exchange Network, Princess Máxima Center, VIVA Foundation Singapore

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ehrhardt MJ, Krull KR, Bhakta N, et al. : Improving quality and quantity of life for childhood cancer survivors globally in the twenty-first century. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 20:678-696, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piñeros M, Mery L, Soerjomataram I, et al. : Scaling up the surveillance of childhood cancer: A global roadmap. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:9-15, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. : The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: An initial report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet 390:2569-2582, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon SB, Bjornard KL, Alberts NM, et al. : Factors influencing risk-based care of the childhood cancer survivor in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin 68:133-152, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies : From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. : Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The Children's Oncology Group long-term follow-up guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group late effects committee and nursing discipline. J Clin Oncol 22:4979-4990, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. : A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: A report from the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:543-549, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Kalsbeek RJ, van der Pal HJH, Kremer LCM, et al. : European PanCareFollowUp recommendations for surveillance of late effects of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer. Eur J Cancer 154:316-328, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonorezos ES, Barnea D, Cohn RJ, et al. : Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer from across the globe: Advancing survivorship care in the next decade. J Clin Oncol 36:2223-2230, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Effinger KE, Haardörfer R, Marchak JG, et al. : Current pediatric cancer survivorship practices: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Cancer Surviv 17:1139-1148, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaauwbroek R, Tuinier W, Meyboom-de Jong B, et al. : Shared care by paediatric oncologists and family doctors for long-term follow-up of adult childhood cancer survivors: A pilot study. Lancet Oncol 9:232-238, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, et al. : Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 21:1447-1451, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. : Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 26:4401-4409, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. : Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Ann Fam Med 2:61-70, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casillas J, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, et al. : Identifying predictors of longitudinal decline in the level of medical care received by adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Health Serv Res 50:1021-1042, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan AP, Chen Y, Henderson TO, et al. : Adherence to surveillance for second malignant neoplasms and cardiac dysfunction in childhood cancer survivors: A childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 38:1711-1722, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landier W, Chen Y, Namdar G, et al. : Impact of tailored education on awareness of personal risk for therapy-related complications among childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 33:3887-3893, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson MM, Leisenring W, Stratton KK, et al. : Increasing cardiomyopathy screening in at-risk adult survivors of pediatric malignancies: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 32:3974-3981, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oeffinger KC, Ford JS, Moskowitz CS, et al. : Promoting breast cancer surveillance: The EMPOWER study, a randomized clinical trial in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 37:2131-2140, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, et al. : The impact of long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 114:131-138, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klosky JL, Cash DK, Buscemi J, et al. : Factors influencing long-term follow-up clinic attendance among survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2:225-232, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller KA, Wojcik KY, Ramirez CN, et al. : Supporting long-term follow-up of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Correlates of healthcare self-efficacy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64:358-363, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson TO, Hlubocky FJ, Wroblewski KE, et al. : Physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of childhood cancer survivors: A mailed survey of pediatric oncologists. J Clin Oncol 28:878-883, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski K, et al. : General internists' preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med 160:11-17, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathan PC, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski KE, et al. : Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 7:275-282, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. : Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209-249, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. : The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reference deleted.

- 29.Reference deleted.

- 30.United Nations : Geospatial, Location Data for a Better World. https://www.un.org/geospatial/mapsgeo/generalmaps [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurosawa S, Mori A, Tsukagoshi M, et al. : Current status and needs of long-term follow-up clinics for hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: Results of a nationwide survey in Japan. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26:949-955, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.İncesoy Özdemİr S, Taçyıldız N, Varan A, et al. : Cross-sectional study: Long term follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors in a developing country, Turkey: Current status, challenges, and future perspectives. Turk J Med Sci 50:1916-1921, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurkure PA, Achrekar S, Uparkar U, et al. : Surviving childhood cancer: What next? Issues under consideration at the after completion of therapy (ACT) clinic in India. Med Pediatr Oncol 41:588-589, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora RS, Arora PR, Seth R, et al. : Childhood cancer survivorship and late effects: The landscape in India in 2020. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67:e28556, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han JW, Kwon SY, Won SC, et al. : Comprehensive clinical follow-up of late effects in childhood cancer survivors shows the need for early and well-timed intervention. Ann Oncol 20:1170-1177, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathore VT, Taluja A, Arora PR, et al. : Delivery of services to childhood cancer survivors in India: A national survey. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 41:707-717, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung YT, Zhang H, Cai J, et al. : Identifying priorities for harmonizing guidelines for the long-term surveillance of childhood cancer survivors in the Chinese Children Cancer Group (CCCG). JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.20.00534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishida Y, Ozono S, Maeda N, et al. : Medical visits of childhood cancer survivors in Japan: A cross-sectional survey. Pediatr Int 53:291-299, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto K, Yamamoto K, Ozono S, et al. : Differences in the approaches of cancer specialists toward adolescent and young adult cancer care. Pediatr Int 64:e15119, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda N, Horibe K, Kato K, et al. : Survey of childhood cancer survivors who stopped follow-up physician visits. Pediatr Int 2:806-812, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terada K, Kakuda H, Iida N, et al. : A questionnaire study of support for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Int 64:e15047, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishida Y, Takahashi M, Maru M, et al. : Physician preferences and knowledge regarding the care of childhood cancer survivors in Japan: A mailed survey of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Oncology. Jpn J Clin Oncol 42:513-521, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwai N, Shimada A, Iwai A, et al. : Childhood cancer survivors: Anxieties felt after treatment and the need for continued support. Pediatr Int 59:1140-1150, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishida Y, Tezuka M, Hayashi M, et al. : Japanese childhood cancer survivors' readiness for care as adults: A cross-sectional survey using the transition scales. Psychooncology 26:1019-1026, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakker ME, Pluimakers VG, van Atteveld JE, et al. : Perspectives on follow-up care and Research for childhood cancer survivors: Results from an international SIOP meet-the-expert questionnaire in Kyoto, 2018. Jpn J Clin Oncol 51:1554-1560, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyoshi Y, Yorifuji T, Shimizu C, et al. : A Nationwide Questionnaire survey targeting Japanese pediatric endocrinologists regarding transitional care in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol 29:55-62, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prasad M, Goswami S: Barriers to long-term follow-up in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Perspectives from a low-middle income setting. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68:e29248, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung YT, Yang LS, Ma JCT, et al. : Health behaviour practices and expectations for a local cancer survivorship programme: A cross-sectional study of survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 28:33-44, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang LS, Ma CT, Chan CH, et al. : Awareness of diagnosis, treatment and risk of late effects in Chinese survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Health Expect 24:1473-1486, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin YT, Chen CM, Chien WC: Factors influencing transitional care from adolescents to young adults with cancer in Taiwan: A population-based study. BMC Pediatr 16:122, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ke Y, Tan CJ, Ng T, et al. : Optimizing survivorship care services for Asian adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A qualitative study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 9:384-393, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeon KH, Shin DW, Lee JW, et al. : Parent caregivers' preferences and satisfaction with currently provided childhood cancer survivorship care. J Cancer Surviv, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arpaci T, Altay N, Yozgat AK, et al. : Trying to catch up with life': The expectations and views of adolescent survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia about long-term follow-up care: A qualitative Research. Eur J Cancer Care 31:e13667, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Society of Clinical Oncology : ASCO Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Care Plans. https://www.cancer.net/survivorship/follow-care-after-cancer-treatment/asco-cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-care-plans [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parsons SK, Saiki-Craighill S, Mayer DK, et al. : Telling children and adolescents about their cancer diagnosis: Cross-cultural comparisons between pediatric oncologists in the US and Japan. Psychooncology 16:60-68, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. : Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA 287:1832-1839, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bashore L: Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors' knowledge of their disease and effects of treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21:98-102, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hudson MM, Tyc VL, Srivastava DK, et al. : Multi-component behavioral intervention to promote health protective behaviors in childhood cancer survivors: The protect study. Med Pediatr Oncol 39:2-1, 2002; discussion 2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Syed IA, Klassen AF, Barr R, et al. : Factors associated with childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their diagnosis, treatment, and risk for late effects. J Cancer Surviv 10:363-374, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee JL, Gutierrez-Colina A, Williamson Lewis R, et al. : Knowledge of late effects risks and healthcare responsibility in adolescents and young adults treated for childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol 44:557-566, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hudson MM: The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital after completion of therapy clinic. J Cancer Surviv 18:23-24, 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan RJ, Milch VE, Crawford-Williams F, et al. : Patient navigation across the cancer care continuum: An overview of systematic reviews and emerging literature. CA Cancer J Clin 73:565-589, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Children’s Oncology Group : Long-term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 6.0. http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Essig S, Skinner R, von der Weid NX, et al. : Follow-up programs for childhood cancer survivors in Europe: A Questionnaire Survey. PLoS One 7:e53201, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]