Abstract

Lipid emulsion has been shown to effectively relieve refractory cardiovascular collapse resulting from toxic levels of nonlocal anesthetics. The goal of this study was to examine the effect of lipid emulsions on neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity using relevant case reports of human patients, with a particular focus on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and corrected QT interval, to analyze drugs that frequently require lipid emulsion treatment. The following keywords were used to retrieve relevant case reports from PubMed: “antidepressant or antipsychotic drug or amitriptyline or bupropion or citalopram or desipramine or dosulepin or dothiepin or doxepin or escitalopram or fluoxetine or haloperidol or olanzapine or phenothiazine or quetiapine or risperidone or trazodone” and “lipid emulsion or Intralipid.” Lipid emulsion treatment reversed the corrected QT interval prolongation and decreases in Glasgow Coma Scale scores caused by toxic doses of neuropsychiatric drugs, especially lipid-soluble drugs such as amitriptyline, trazodone, quetiapine, lamotrigine, and citalopram. The log P (octanol/water partition coefficient) of the group which required more than 3 lipid emulsion treatments was higher than that that of the group which required less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments. The main rationale to administer lipid emulsion as an adjuvant was as follows: hemodynamic depression intractable to supportive treatment (88.3%) > lipophilic drugs (8.3%) > suspected overdose or no spontaneous breathing (1.6%). Adjuvant lipid emulsion treatment contributed to the recovery of 98.30% of patients with neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity. However, further analyses using many case reports are needed to clarify the effects of lipid emulsion resuscitation.

Keywords: Glasgow Coma Scale, lipid emulsion, lipid solubility, lipid soluble, neuropsychiatric drugs, QTc, toxicity

1. Introduction

Currently, local anesthetic-induced systemic toxicity is treated with lipid emulsion, which is primarily used for parenteral nutrition.[1] Supportive treatments, which are used to alleviate central nervous and cardiovascular symptoms caused by toxicity due to other substances (including neuropsychiatric drugs without a specific antidote), include charcoal, gastric lavage, fluid administration, sodium bicarbonate, inotropic agents, vasopressors, anti-arrhythmic drugs, and defibrillation.[2,3] However, when supportive treatment does not improve the symptoms caused by neuropsychiatric drugs toxicity, lipid emulsion as adjuvant drug has been reported to be effective in ameliorating intractable central nervous system and cardiovascular system symptoms caused by toxic doses of antipsychotics and antidepressants.[2–4] In 2008, Siriari et al[5] reported a clinical case regarding lipid emulsion resuscitation of intractable cardiac arrest due to toxic doses of bupropion (an antidepressant) and lamotrigine (an anticonvulsant); this was the first successful lipid emulsion resuscitation for nonlocal anesthetic toxicity. Antidepressants, including amitriptyline and fluoxetine, and antipsychotics, such as quetiapine and haloperidol, produce corrected QT interval (QTc) prolongation, which leads to Torsade de Pointes, ventricular fibrillation, and cardiac arrest.[6] SMOFlipid was reported to reverse the decreased Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and QTc prolongation induced by clozapine (an atypical antipsychotic) toxicity.[7] Intralipid increased the GCS scores of patients with acute toxicity caused by various nonlocal anesthetic drugs.[8] In addition, the time required to recovery from sevoflurane and isoflurane anesthesia was shortened by lipid emulsion in rats, and appeared to be mediated by lipid emulsion-mediated reduction of sevoflurane and isoflurane concentrations.[9] However, a systemic analysis of case reports regarding the effect of lipid emulsion on neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines (sedatives), and anticonvulsants, has not previously been reported. Moreover, a randomized controlled study regarding the effect of lipid emulsion on neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity in humans is impossible due to ethics concerns.[10] Thus, in this review, we analyzed case reports on lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity retrieved from PubMed until December 20, 2023. The goal of this review was to investigate the effect of lipid emulsion on symptoms caused by neuropsychiatric drug toxicity, with a particular focus on QTc prolongation, decreased GCS scores, and the lipophilicity of drugs that more frequently require lipid emulsion treatment.

2. Methods

Institutional review board approval was not needed because this was a narrative review using case reports.

2.1. Case search

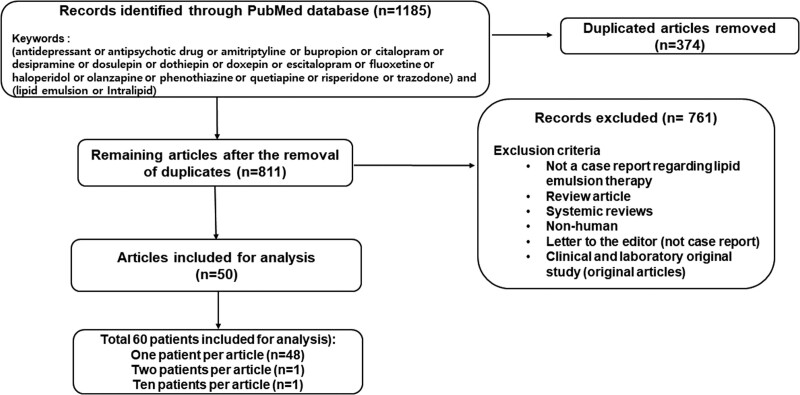

Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline,[11] the following terms were used to search for relevant case reports involving humans regarding the effect of lipid emulsion on drug toxicity caused by neuropsychiatric drugs until December 20, 2023: “antidepressant or antipsychotic drug or amitriptyline or bupropion or citalopram or desipramine or dosulepin or dothiepin or doxepin or escitalopram or fluoxetine or haloperidol or olanzapine or phenothiazine or quetiapine or risperidone or trazodone” and “lipid emulsion or Intralipid.” We retrieved a total of 1185 articles from PubMed (Fig. 1), which is Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for retrieving clinical case reports on lipid emulsion treatment as an adjuvant therapy for systemic neuropsychiatric (antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and anticonvulsants) drug toxicity based on a PubMed keyword search. “n” indicates the number of articles.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

After removing duplicate articles (n = 374), 811 articles remained. A further 761 articles were excluded for the following reasons: no case report regarding lipid emulsion therapy, review article, systemic review, nonhuman cases, letter to the editor (not case report), and/or an original clinical and laboratory research article (Fig. 1). Finally, 50 articles were included in the analysis. As 1 article contained 2 patients and another article contained 10 patients, the 50 articles included 60 patients (Fig. 1).

2.3. Data extraction

Pre- and post-lipid emulsion treatment QTc intervals and GCS scores were obtained from each case report based on measurements just before and after the administration of lipid emulsion, respectively. QTc intervals were calculated using the Bazett formula (QTc = QT/RR1/2).[6] All other data, including age, sex, underlying diseases, neuropsychiatric drugs, dosage, lipid emulsion treatment information, improvement of symptoms, and outcomes, were obtained from the case reports. Log P (octanol/water partition coefficient) was obtained from PubChem.[12]

2.4. Statistical analysis

Normality tests for all data, which included log P of the drug, GCS score, and QTc, were performed using Shapiro–Wilk tests (Prism 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The effect of lipid emulsion on GCS score was analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. The effect of lipid emulsion on QTc prolongation was analyzed using paired Student’s t tests. The log P values of the groups which required more than or less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. P values below .05 indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Sex, age, underlying disease, and drugs

The numbers of male and female patients (total patients: 60) with systemic neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity who underwent lipid emulsion treatment as an adjuvant drug were 20 (33.33%) and 37 (61.66%), respectively (Table 1). The age distribution was as follows (Table 1): 20–29 years (16 patients, 26.6%), 10–19 years (10 patients, 16.6%), 30–39 years (10 patients, 16.6%), 50–59 years (9 patients, 15%), 40–49 years (8 patients, 13.3%), 60–69 years (3 patients, 5%), and <10 years (2 patients, 3.3%). The incidence of underlying diseases were as follows (Table 1): depression (18 patients, 30%), bipolar disorder (5 patients, 8.33%), schizophrenia (3 patients, 5%), and epilepsy (2 patients, 3.33%). Two patients did not have any underlying diseases. The drugs that caused toxicity, which were mainly neuropsychiatric drugs, were as follows (n = 39; Table 1): antidepressants including amitriptyline, nortriptyline, dosulepine (dothiepine), doxepine, citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, bupropion, mirtazapine, and trazodone; antipsychotics including olanzapine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, aripiprazole, amisulpride, zopiclone, and paliperidone; benzodiazepines including diazepam, clonazepam, bromazepam, and alprazolam; anticonvulsants including pregabalin, gabapentin, and lamotrigine; and other drugs including metoprolol, propranolol, cyclobenzapine, hydroxyzine, nifedipine, quinapril, aspirin, valsartan, ibuprofen, insulin, amoxicillin, and clonidine. The specific drugs which most frequently caused neuropsychiatric drug toxicity (total number of drugs including duplicates: 109) and required lipid emulsion treatment as an adjuvant drug were as follows (Table 1): amitriptyline (19.2%) > quetiapine (11%) > venlafaxine (6.4%) > citalopram or olanzapine (5.5%) > lamotrigine or bupropion (4.6%) > trazodone (3.7%) > dosulepin or sertraline or fluoxetine (2.8%) > zopiclone or escitalopram or cyclobenzaprine or diazepam or metoprolol or gabapentin (1.8%) > others (0.9%).

Table 1.

Lipid emulsion treatment for toxicity caused by neuropsychiatric drugs (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and anticonvulsants).

| Case no. | Sex | Age | Underlying disease | Drug | Dosage | Log P | Pre-LE QTc | Pre-LE GCS | Kind of LE | Post-LE QTc | Post-LE GCS | Improved symptoms | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1[13] | F | 28 | Depression | Amitriptyline | 3.7 g | 4.92 | 475 ms | N/A (coma) | 20% LE | 441 ms | WNL | CNS, CV | R |

| 2[14] | F | 77 | Depression | Trazodone | 4.5 g | 2.68 | 540 ms | 3 | 20% Intralipid | 411 ms | 10 | CNS, CV | R |

| 3[15] | F | 15 | N | Bupropion | 1650–9000 mg | 3.6 | 461 ms | 11 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 4[16] | N/A | 25 | Depression | Amitriptyline Quetiapine |

5.5 g 10 g |

4.92 2.81 |

650 ms | 3 | 20% SMOFlipid | 509 ms | N/A | CNS, CV Normothermia |

R QTc Prolongation state (120%) |

| 5[17] | F | 19 | N | Quetiapine Citalopram Bromazepam |

6000 mg 400 mg 45 mg |

2.81 3.76 2.05 |

570 ms | 11 | 20 % Lipofundin MCT/LCT | 370 ms | 15 | CNS, CV | R |

| 6[18] | F | 14 | N/A | Bupropion Hydroxyzine Citalopram |

9 g N/A N/A |

3.6 2.36 3.76 |

527 ms | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 7[19] | M | 21 | Depression | Citalopram Clonazepam Olanzapine |

11.6 g 5 mg 600 mg |

3.76 2.41 3.0 |

487 ms | N/A | 10% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 8[20] | F | 42 | Schizoaffective disorder | Quetiapine | 24 g | 2.81 | 467 ms | 3 | 20% Intralipid | normal | N/A | CV | R |

| 9[21] | F | 34 | N/A | Amitriptyline Citalopram |

5600 mg 2400 mg |

4.92 3.76 |

550 ms | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 10[22] | F | 13 | N/A | Amitriptyline Nortriptyline |

N/A | 4.92 3.9 |

477 ms | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 11[23] | F | 25 | Anorexia Depression |

Amitriptyline Fluoxetine Escitalopram Olanzapine Quetiapine Gabapentin |

N/A | 4.92 4.05 3.74 3.0 2.81 1.25 |

611 ms | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 12[24] | M | 51 | Depression IHD |

Amitriptyline Quetiapine Citalopram Metoprolol Quinapril Aspirin |

3250 mg N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A |

4.92 2.81 3.76 2.15 .86 1.18 |

570 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 500 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 13[25] | F | 36 | N/A | Dothiepin | 2250 mg | 4.49 | 502 ms | N/A | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 14[26] | F | 36 | Schizophrenia | Dosulepin | 5.25 g | 4.49 | 520 ms | 10 | 20% Intralipid | 506 ms | N/A | N/A | R |

| 15[5] | F | 17 | Bipolar disorder | Bupropion Lamotrigine |

4 g 7.95 g |

3.6 2.57 |

485 ms | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | CNS sequelae |

| 16[27] | F | 45 | Anxiety Depression Hypertension |

Haloperidol | 5 g | 4.3 | 545 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 385 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 17[28] | M | 54 | Anxiety Depression CAD CHF COPD type II DM |

Trazodone | 100 mg | 2.68 | 539 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 485 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 18[29] | F | 45 | N/A | Amisulpride Diazepam Valsartan Aripiprazole Paliperidone |

28 g 250 mg 2240 mg 45 mg 21 mg |

1.06 2.82 1.499 5.30 1.8 |

547 ms | N/A | 20% SMOFlipid | 541 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 19[30] | M | 36 | Bipolar disorder | Lamotrigine | 13.5 g | 2.57 | 458 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 392 ms | N/A | CV | CNS sequelae |

| 20[31] | F | 25 | N/A | Amitriptyline Propranolol Pregabalin |

N/A | 4.92 3.48 1.3 |

503 ms | 3 | 20% Intralipid | 444 ms | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 21[32] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Amitriptyline Zopiclone Venlafaxine Alcohol |

4.8 g N/A N/A N/A |

4.92 .8 3.20 – |

Prolonged QTc | 3 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 22[33] | F | Young | Depression | Bupropion Sertraline |

N/A | 3.6 5.51 |

525 ms | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 23[34] | F | 53 | Depression | Venlafaxine Amitriptyline Citalopram |

N/A | 3.2 4.92 3.76 |

Prolonged QT | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | CNS sequelae |

| 24[35] | F | 35 | N/A | Quetiapine | 36 g | 2.81 | 558 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 440 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 25[35] | F | 64 | Bipolar disorder CKD stage III COPD Hypertension |

Quetiapine | 8.7 g | 2.81 | N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | CNS sequelae |

| 26[36] | F | 25 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 2.5 g | 4.92 | 475 ms | 10 | 20% LE | 400 ms | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 27[37] | F | 19 | Depression | Venlafaxine | 18 g | 3.2 | N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 28[38] | N/A | 45 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 50 mg | 4.92 | 589 ms | coma | 20% LE | 503 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 29[39] | M | 18 | Depression ADHD |

Amitriptyline Venlafaxine |

N/A | 4.92 3.2 |

410 ms | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | N/A | R |

| 30[40] | F | 28 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 5 g | 4.92 | N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 31[41] | F | 24 | Depression | Chlorpromazine Mirtazapine |

3000 mg 990 mg |

5.41 2.9 |

N/A | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 32[42] | F | 51 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 925 mg | 4.92 | N/A | 10 | 20% LE | N/A | 14 | CNS, CV | R |

| 33[42] | F | 24 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 875 mg | 4.92 | N/A | 7 | 20% LE | N/A | 9 | CNS, CV | R |

| 34[42] | F | 32 | N/A | Metoprolol | 475 mg | 2.15 | N/A | 15 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 35[42] | F | 32 | N/A | Fluoxetine Alprazolam Nifedipine |

N/A | 4.05 2.12 2.2 |

N/A | 8 | 20% LE | N/A | 8 | CNS, CV | R |

| 36[42] | M | 28 | N/A | Quetiapine | 2400 mg | 2.81 | N/A | 13 | 20% LE | N/A | 15 | CNS, CV | R |

| 37[42] | F | 18 | Epilepsy | Lamotrigine Sertraline |

N/A | 2.57 5.51 |

N/A | 12 | 20% LE | N/A | 15 | CNS | R |

| 38[42] | M | 17 | N/A | Bonsai | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9 | 20% LE | N/A | 14 | CNS, CV | R |

| 39[42] | F | 24 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 520 mg | 4.92 | N/A | 12 | 20% LE | N/A | 14 | CNS, CV | R |

| 40[42] | F | 18 | N/A | Amitriptyline α-lipoic acid |

N/A | 4.92 – |

N/A | 8 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | N | D |

| 41[42] | F | 23 | N/A | Amitriptyline | N/A | 4.92 | N/A | 8 | 20% LE | N/A | 13 | CNS | N/A |

| 42[43] | M | 44 | N/A | Amitriptyline | 2.25 g | 4.92 | 509 ms | N/A | 20% LE | 379 ms | N/A | CV | R |

| 43[44] | F | 29 | N/A | Quetiapine Ibuprofen Escitalopram Amoxicillin |

9 g 4 g 280 mg 5 g |

2.81 3.97 3.74 .87 |

N/A | 2T | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 44[45] | M | 50 | N/A | Trazodone Cyclobenzaprine Doxepin |

N/A | 2.68 5.2 4.29 |

N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 45[46] | F | 20M | N/A | Dosulepin | 450 mg | 4.49 | N/A | N/A | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 46[47] | M | 4 | Epilepsy | Olanzapine | N/A | 4.09 | N/A | N/A | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 47[48] | F | 39 | N/A | Olanzapine | 100 mg | 4.09 | N/A | 7 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 48[49] | M | 50 | Bipolar disorder Type II DM |

Lamotrigine | 3.5 g | 2.57 | 521 ms | 7 | 20% LE | 455 ms | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 49[50] | F | 44 | Depression | Diazepam Lamotrigine Venlafaxine |

200 mg 20 g 4.5 g |

2.82 2.57 3.2 |

N/A | 6 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 50[51] | M | 52 | Depression Alcoholic liver disease Osteoporosis Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency Peptic ulcer disease B12 deficiency |

Amitriptyline Liraglutide |

N/A 36 mg |

4.92 – |

N/A | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 51[52] | M | 49 | Depression | Trazodone | 5000 mg | 2.68 | 489 ms | 11 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 52[53] | M | 21 | N/A | Amitriptyline | N/A | 4.92 | N/A | 3 | 20% LE | N/A | 10 | CNS, CV | CNS sequelae |

| 53[54] | M | 55 | Depression | Zopiclone Venlafaxine |

N/A 1.8 g |

.8 3.2 |

Normal | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 54[55] | F | 30 | N/A | Olanzapine | 250 mg | 4.09 | Normal | 9 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS | R |

| 55[56] | M | 22 | N/A | Cyclobenzaprine | N/A | 5.2 | N/A | 3 | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CV | R |

| 56[57] | M | 61 | Bipolar disorder Depression | Quetiapine Sertraline | 4.3 g 3.1 g |

2.81 5.51 |

Normal | 3 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | 15 | CNS | R |

| 57[58] | M | 33 | schizoaffective disorder | Quetiapine Venlafaxine |

12 g 4.5 g |

2.81 3.2 |

510 ms | 4 | 20% Intralipid | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 58[59] | M | 48 | ADHD Migraine Hypertension Cervical radiculopathy |

Amitriptyline | N/A | 4.92 | N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 59[60] | F | 53 | Depression Bipolar disorder ADHD Chronic pain syndrome |

Clonidine Fluoxetine Bupropion gabapentin Quetiapine |

6 g 1.2 g 13.5 g 9 g 6 g |

1.59 4.05 3.6 1.25 2.81 |

N/A | N/A | 20% LE | N/A | N/A | CNS, CV | R |

| 60[61] | M | 20 | Intellectual disability ADHD |

Olanzapine | 840 mg | 4.09 | Normal | 5 | Clinoleic | Normal | N/A | CNS | R |

ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, CAD = coronary artery disease, CHF = congestive heart failure, CKD = chronic kidney disease, CNS = central nervous system, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CV = cardiovascular, D = death, DM = diabetes mellitus, F = female, GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale, IHD = ischemic heart disease, LE = lipid emulsion, Log P = log (octanol/water partition coefficient), M = male, N = none, N/A = not available, QTC = corrected QT interval, R = recovery, T = intubation, WNL = within normal limits.

3.2. Log P, QTc, and GCS score

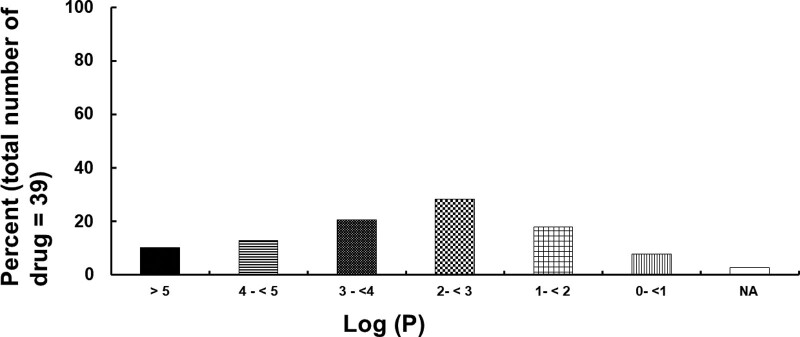

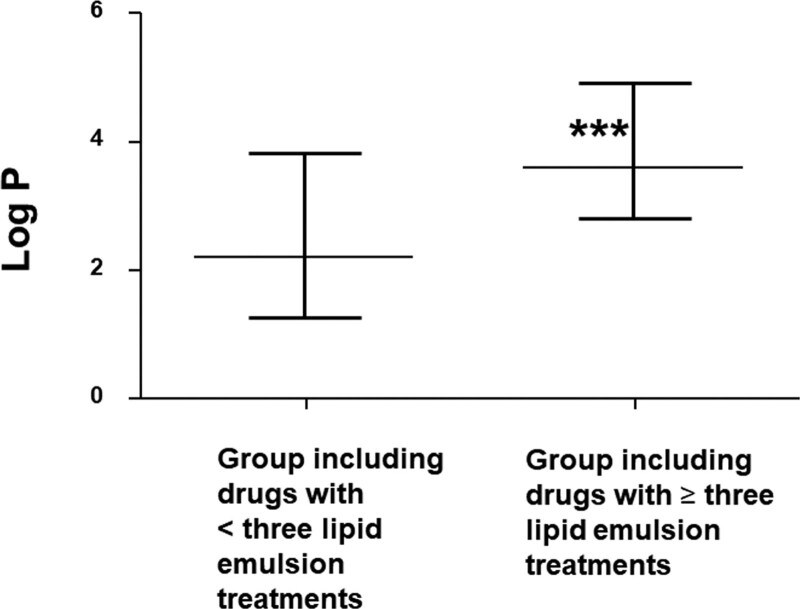

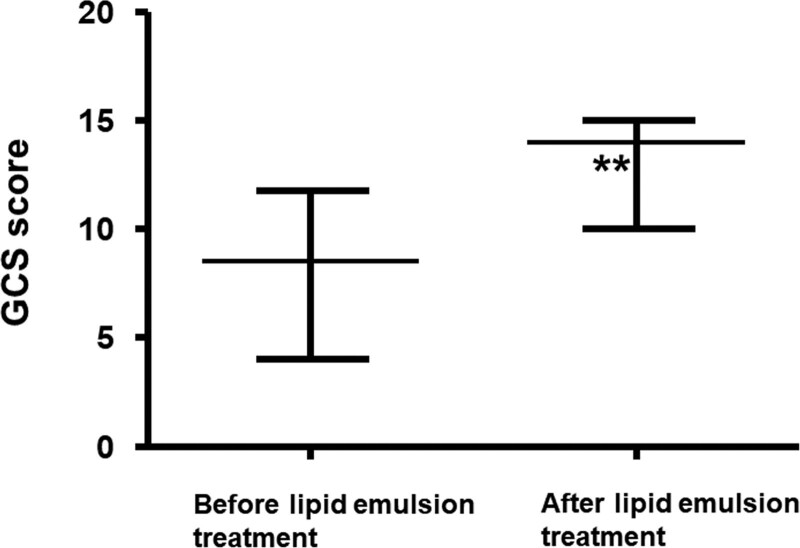

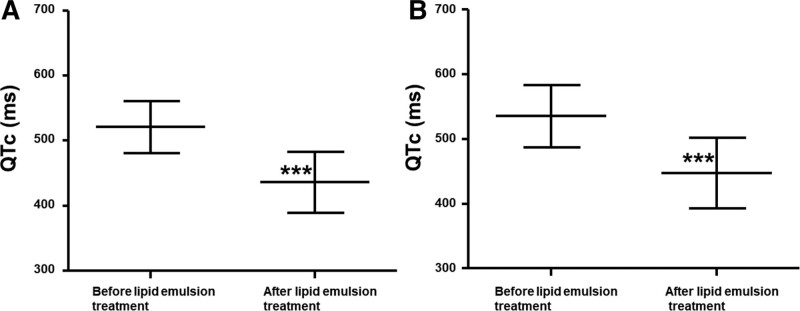

Toxicity due to a single drug or by multiple drugs occurred in 33 (55%) and 27 (45%) patients, respectively (Table 1). The distribution of the lipid solubility (log P) of neuropsychiatric drugs is shown in Figure 2. Of 39 drugs, 11 (28.21%) had a log P ≥ 2 to <3, while 28 (71.79%) had a log P of >2, and were considered highly lipid soluble.[62] In addition, of 39 drugs, 7 (17.94%) and 3 (7.69%) had a log P of ≥1 to <2 and <1, respectively, and were considered less lipid soluble. In addition, the log P (median [interquartile range: 25–75%]: 3.6 [2.81–4.92]) of the group which required more than 3 lipid emulsion treatments was higher than that (log P: 2.2 [1.28–3.82]) of the group which required less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments (P < .001; Fig. 3). Lipid emulsion significantly increased the GCS from 8.5 [4–11.75] (median [interquartile range: 25–75%]) to 14 [10–15] in 12 patients (Fig. 4, P = .0037). Lipid emulsion also significantly shortened single drug-induced prolonged QTc (QTc: mean ± standard deviation [SD]; before lipid emulsion treatment = 520.8 ± 39.5 ms, after lipid emulsion treatment = 436.1 ± 46.8 ms) in 11 patients (Fig. 5A, P < .001). It also significantly shortened single and multiple drug-induced prolonged QTc from 535 ± 48 to 447 ± 54 ms (Fig. 5B, P < .001) in 16 patients.

Figure 2.

Distribution of lipid solubility (log P: log [octanol/water partition coefficient]) of neuropsychiatric drugs (total number of drugs: 39) that caused toxicity in patients undergoing lipid emulsion treatment. N/A = not available.

Figure 3.

Comparison of lipid solubility (log P: log [octanol/water partition coefficient]) for the groups (including duplicates) that required more than or less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments; the total numbers of drugs in each group were 75 and 33, respectively. Data are shown as the median ± interquartile range (25–75%); ***P < .001 vs group which required less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments.

Figure 4.

Effect of lipid emulsion on the GCS scores in patients (n = 12) undergoing lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug toxicity. Data are shown as the median ± interquartile range (25–75%); n indicates the number of patients and **P = .0037 vs before lipid emulsion treatment. GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale.

Figure 5.

Effect of lipid emulsion on the prolonged corrected QTc interval (QTc) in patients undergoing lipid emulsion treatment for drug toxicity related to a single neuropsychiatric drug (A, n = 11) or single and multiple drugs (B, n = 16). Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation; n indicates the number of patients. ***P < .001 vs before lipid emulsion treatment.

3.3. Lipid emulsion treatment

Intralipid, which contains 100% long-chain fatty acids, was the most commonly used lipid emulsion (17 patients; 28.3%) for the treatment of neuropsychiatric drug toxicity (Table 1). However, many case reports (38 patients, 63.33%) described only 20% lipid emulsions. The method of administration of lipid emulsions in neuropsychiatric drug toxicity was as follows (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/L976): bolus administration followed by continuous infusion (40 patients, 66.6%), bolus administration only (8 patients, 13.38%), and continuous infusion only (7 patients, 11.6%). Among patients who underwent most commonly employed administration method (bolus administration followed by continuous infusion; 40 patients), a 1.5 mL/kg bolus of 20% lipid emulsion followed by 0.25 mL/kg/min continuous infusion of 20% lipid emulsion was most frequently used (12/40, 30%). Patients also commonly received a 100 mL bolus followed by 0.5 mL/kg/min continuous infusion of the lipid emulsion (10/40, 25%) (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/L976). The main rationale to administer lipid emulsion as an adjuvant drug for toxicity caused by neuropsychiatric drugs was as follows (Table 1): hemodynamic depression intractable to supportive treatment (53 patients, 88.3%) > lipophilic drugs (5 patients, 8.3%; Case No.: 43, 46, 47, 53, 56) > no spontaneous breathing and alertness (1 patient, 1.6%; Case No.: 60) or suspected overdose (1 patient, 1.6%, Case No.: 51; Table 1).

3.4. Symptom improvement and side effects

The frequency of symptom improvement after lipid emulsion administration was as follows (Table 1): cardiovascular and central nervous system symptoms (24 patients, 40%), cardiovascular symptoms alone (23 patients, 38.3%), and central nervous system symptoms alone (10 patients, 16.7%). However, lipid emulsion did not improve symptoms in 1 patient (1.61%; Table 1). Lipid emulsion generally improved symptoms rapidly (within 5 minutes, 10–30 minutes, and 30–60 minutes after lipid emulsion administration in 14 (23.3%), 2 (3.3%), 10 (16.7%), and 8 (13.3%) patients, respectively) (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/L976). The total volume of lipid emulsion administered was as follows (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/L976): ≤500 mL (21 patients, 35%), >3000 to ≤4000 mL (7 patients, 11.7%), >500 to ≤1000 mL (7 patients, 11.7%), >1000 to ≤2000 mL (3 patients, 5%), >4000 to ≤5000 mL (1 patient, 1.6%), or >5000 mL (1 patient, 1.6%). The administration of lipid emulsion as an adjuvant drug resulted in full recovery from neuropsychiatric drug toxicity in 52 patients (86.7%; Table 1). In addition, 5 patients recovered with central nervous sequelae, and another recovered but with sustained prolonged QTc (Table 1). One patient died despite receiving lipid emulsion treatment (Table 1). Residual central nervous system sequelae after lipid emulsion treatment for drug toxicity caused by an overdose of multiple drugs (bupropion and lamotrigine or venlafaxine, amitriptyline, and citalopram) or a single drug (lamotrigine, quetiapine, and amitriptyline) included slight tremors, altered mental status, neurocognitive dysfunction, and lack of alertness (Case No.: 15, 19, 23, 25, 52; Table 1). The side effects of lipid emulsion resuscitation included hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, lung infiltration, pancreatitis, increased amylase and lipase levels, ground-glass opacities of the lungs, and increased aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels.

3.5. Posttreatment symptom recurrence

In some cases, symptoms initially improved following the administration of lipid emulsion but later deteriorated. These later-onset symptoms included altered mental status, a widened QRS interval, hypotension, pulseless wide-complex tachycardia, apnea, pupil dilation, decreased GCS scores, tachycardia, and somnolence. The drugs associated with these recurrent symptoms included bupropion, amitriptyline, fluoxetine, escitalopram, olanzapine, quetiapine, pregabalin, gabapentin, and propranolol.

4. Discussion

The results of this review show that administering lipid emulsion as an adjuvant drug shortens QTc prolongation and improves GCS scores in patients with intractable drug toxicity caused by toxic doses of lipid-soluble neuropsychiatric drugs, leading to improved recovery.

Phase 3 of the cardiac action potential involves inactivation of inward calcium currents and activation of rapid outward potassium currents with slow potassium currents and inward rectifying potassium currents.[6] QT prolongation may occur when the outward potassium current is decreased or inward calcium or sodium currents is increased during phase 3 of the cardiac action potential.[6] Antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, fluoxetine, imipramine, and doxepine) and antipsychotics (e.g., quetiapine, haloperidol, chloropromazine, amisulpride, and risperidone) cause QT prolongation, leading to ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest.[6] Local anesthetic inhibits human ether-a-go-go-related gene cardiac potassium channels, which codes for rapid delayed rectified potassium channels.[63] Bupivacaine (log P: 3.41) is a highly lipid-soluble local anesthetic which induces QTc prolongation, and lipid emulsion reversed bupivacaine-related increased Tpeak-to-Tend intervals (transmural dispersion).[64] A randomized controlled study reported that lipid emulsion reversed clozapine (log P: 2.41) toxicity-related QTc prolongation.[7] In addition, lipid emulsion reversed QTc prolongation and inhibited myocardial cell death caused by amitriptyline toxicity in rats.[65] Similar to these previous reports,[7,64,65] lipid emulsion ameliorated QTc prolongation caused by toxic doses of neuropsychiatric drugs, including amitriptyline (log P: 4.92), trazodone (log P: 2.68), desulepin (log P: 4.49), haloperidol (log P: 4.3), lamotrigine (log P: 2.57), and quetiapine (log P: 2.81). The above-mentioned neuropsychiatric drugs (log P: 3.55 [2.65–4.59]) are highly lipid-soluble (log P: >2; Table 1). In addition, lipid emulsion alone has positive inotropic and lusitropic effects.[66,67] Considering previous reports, this lipid emulsion-mediated reversal of QTc prolongation and positive inotropy may contribute to the reversal of neuropsychiatric drug toxicity-induced cardiac depression.[1,6,7,63–67] However, retrospective analyses of case reports using lipid emulsion as an adjuvant drug have suggested that lipid emulsion does not significantly improve QTc prolongation caused by antihistamine diphenhydramine toxicity.[68] This difference may reflect the small sample size of the lipid emulsion group in the previous study, and differences in experimental methods (with vs without a control group).

Local anesthetic-related systemic toxicity usually involves the central nervous system, followed by symptoms associated with the cardiovascular system.[1] Early lipid emulsion administration in patients with bupivacaine- or ropivacaine-induced central nervous system symptoms prior to the onset of cardiac symptoms treated perioral numbness, restlessness, agitation, dizziness, and dysarthria.[69,70] In addition, a randomized controlled study suggested that lipid emulsion shortened the recovery time from isoflurane anesthesia, leading to improved recovery quality.[71,72] An animal study also corroborated that lipid emulsion shortened the time from isoflurane anesthesia to recovery, and decreased the proportion of the delta-band in the electroencephalogram during anesthesia, which appears to be mediated by lipid emulsion-induced reduction of isoflurane concentrations.[9] Lipid emulsion and supportive treatment improved the GCS of patients with drug toxicity due to nonlocal anesthetic drugs or clozapine alone.[7,8] Consistent with previous reports,[7,8,72] in our analysis, lipid emulsion reversed the decreased GCS score related to overdoses of the following: amitriptyline (log P: 4.92), trazodone (log P: 2.68), quetiapine (log P: 2.81), citalopram (log P: 3.76), bromazepam (log P: 2.05), fluoxetine (log P: 4.05), alprazolam (log P: 2.12), lamotrigine (log P: 2.57), and sertraline (log P: 5.51), which are all highly-soluble (log P: 3.38 ± 1.24). Moreover, lipid emulsion treatment in intravenous amitriptyline toxicity increased arterial plasma amitriptyline concentrations but reduced brain amitriptyline concentrations, suggesting lipid emulsion-induced sequestration of amitriptyline from the brain to the blood.[73] Thus, considering these previous laboratory reports, the increase in GCS after lipid emulsion administration may be associated with increased partitioning of highly lipid-soluble neuropsychiatric drugs into the blood from the brain.[9,73] However, further studies are needed to examine the detailed mechanism responsible for this phenomenon.

The magnitude of lipid emulsion-induced decreases in serum drug concentrations was reported to be strongly correlated with the lipid solubility of drugs.[74] Lipid emulsion inhibited the decreased blood pressure caused by toxic doses of verapamil, which has high lipid solubility (log P: 3.79), but had no effect on that caused by diltiazem, which has relatively low lipid solubility (log P: 2.8).[75] Moreover, lipid emulsion inhibited the decreased cell viability caused by verapamil toxicity in rat cardiomyoblasts more than that induced by diltiazem toxicity.[76] Lipid emulsion inhibited propranolol-induced hypotension, which is highly lipid-soluble (log P: 3.48).[77] However, it exerted no effect on metoprolol-related hypotension, which is less lipid-soluble (log P: 2.15).[78] Taken together, these previous results suggest that lipid emulsion-mediated treatment is dependent on the lipid solubility of the offending drugs.[74–78] Lipid emulsion resuscitation is believed to be mediated by a lipid shuttle which forms via binding of the lipid emulsion to the offending drugs, allowing for their redistribution.[79] Intravenously-administered lipid emulsions generate a lipid phase component in the blood, which adsorbs lipid-soluble drugs from the heart and brain, which receive high blood flows.[79] The drug-containing lipid emulsion is then delivered to the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue for detoxification and storage.[79] When lipid emulsions were given 30 minutes after intravenous amitriptyline toxicity, amitriptyline concentrations in the heart and brain decreased while that in the arterial plasma increased, suggesting lipid emulsion-mediated partitioning from organs with high blood flow to the arterial blood.[73] Consistent with previous reports, 71.79% (28/39) of drugs that underwent lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug toxicity were highly lipid-soluble (log P: >2).[62] Moreover, the lipid solubility (log P) of the drugs for the group which required more than 3 lipid emulsion treatments were higher than that of the group which required less than 3 lipid emulsion treatments (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results suggest that highly lipid-soluble drugs which produce neuropsychiatric drug toxicity require more lipid emulsion treatments than less lipid-soluble drugs.[74–78] Furthermore, as the log P of all drugs to produce improved QTc and GCS was more than 2, the high lipid solubility of these drugs may have contributed to the recovery of 96.66% (58/60) of patients from neuropsychiatric drug toxicity by shortening QTc prolongation and increasing GCS score. Bolus administration of 1.5 mL/kg lipid emulsion (20%) followed by 0.25 mL/kg/min continuous infusion of 20% lipid emulsion was most frequently employed (12/60, 20%), which is the recommended dosing regimen to treat local anesthetic-related systemic toxicity.[1] However, local anesthetic systemic toxicity mostly occurs via inadvertently intravenous administration, whereas neuropsychiatric drug toxicity most occurs via oral administration. Thus, the toxicokinetics of drug toxicity due to toxic doses of local anesthetic and nonlocal anesthetic drugs are different. Furthermore, intravenous lipid emulsion administered 30 minutes after amitriptyline toxicity via orogastric administration increased blood amitriptyline concentrations, suggesting lipid emulsion-induced increased absorption from the gastrointestinal tract.[80] Thus, further studies are needed to determine the optimal dosing regimen of lipid emulsion treatment for nonlocal anesthetic drug toxicity via oral administration. Studies have shown that 1% plasma triglyceride has both scavenging and positive inotropic and lusitropic effects.[66,67,81] In addition, the maximum Intralipid (10%) clearing capacity (K1) has been reported to be 110 ± 4 μM/L/min.[82] One previous report suggested the following dosing regimen for 20% lipid emulsion treatment for nonlocal anesthetic drug toxicity via oral administration, which produced a 1% plasma triglyceride concentration: 1.5 mL/kg bolus administration, then 0.25 mL/kg/min continuous infusion for 3 minutes, followed by 0.025 mL/kg/min continuous infusion.[66,67,80–83]

Previous studies have suggested that lipid emulsion treatment improves various symptoms caused by nonlocal anesthetic drug toxicity in the following order of frequency: symptoms of the cardiovascular system alone > symptoms of the central nervous system alone > symptoms associated with both the cardiovascular and central nervous systems.[2,3] However, in the present study, lipid emulsion treatment most commonly improved symptoms associated with the cardiovascular and central nervous systems, followed by the cardiovascular system alone, followed by the central nervous system alone. This difference may be due to differences in the involved drugs.[2,3] Consistent with a previous report, the main reason for prescribing lipid emulsion treatment in neuropsychiatric drug toxicity was hemodynamic depression (53/60, 88.3%) that was resistant to supportive treatment.[2] A meta-analysis of lipid emulsion treatment for nonlocal anesthetic-induced toxicity reported that lipid emulsion treatment reduced the odds ratio of mortality to 0.43.[84] After lipid emulsion treatment, most patients (52/60, 86.6%) fully recovered from neuropsychiatric drug toxicity which was intractable to supportive treatment. Similar to previous reports, lipid emulsion treatment produced the following side effects: lipemia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, pancreatitis, and hypertriglyceridemia.[85,86] On the other hand, these side effects may be partially due to underlying conditions rather than lipid emulsion treatment itself (protopathic bias).[87] Consistent with previous reports, Intralipid was commonly used for the treatment of neuropsychiatric drug toxicity.[2,3] However, the availability of Intralipid is limited because linoleic acid, which is the main long-chain fatty acid in Intralipid, produces pro-inflammatory mediators and induces lipid perioxidation.[88] However, alternative lipid emulsion preparations can be used in the treatment of cardiovascular depression related to local anesthetic systemic toxicity, such as Lipofundin MCT/LCT, SMOFlipid, and Clinoelic.[89] Thus, other alternative lipid emulsions such as Lipofundin MCT/LCT, SMOFlipid, and Clinoelic, can be used as adjuvant drugs with supportive treatment in treating nonlocal anesthetic drug toxicity involving critical cardiovascular depression. In the current analysis, lipid emulsion administration led to full recovery from some cases of neuropsychiatric drug toxicity. However, other patients with toxicity induced by the same drug did not fully recover. These contrasting results may be due to the dosage of the neuropsychiatric drug, predisposing factors, lipid emulsion dosage, timing of lipid emulsion administration, and additional supportive treatments used.

4.1. Limitations of this study

We examined the effect of lipid emulsion as an adjuvant drug on toxicity related to various neuropsychiatric drugs. However, examining the effect of lipid emulsions on drug toxicity caused by a single antidepressant or antipsychotic is more appropriate for reaching clear conclusions. Second, negative results (no beneficial effect of supportive treatment plus lipid emulsion compared with supportive treatment alone) regarding lipid emulsion treatment of neuropsychiatric drug toxicity are relatively more difficult to publish compared with positive results, which skews the results of case-based analysis. Third, this analysis only used case reports of patients treated with both lipid emulsion and supportive treatment, and an analysis comparing lipid emulsion and supportive treatment with supportive treatment alone is needed to confirm our findings. Despite these limitations, our study results hold value as it is impossible to perform a completely randomized clinical study to examine the effects of lipid emulsions on drug toxicity in humans for various reasons, including ethical issues. In addition, several case reports regarding lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug toxicity are available. The present study is a comprehensive systemic review of case reports regarding lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug toxicity, with a particular focus on GCS scores, QTc, and the lipophilicity of the offending drugs. Thus, this analysis may be helpful in guiding lipid emulsion treatment for neuropsychiatric drug toxicity. Further analysis using additional case reports accumulated through the lipid emulsion resuscitation registry is needed to reach clearer conclusions.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, lipid emulsion treatment as an adjuvant drug induces the reversal of decreased GCS scores and QTc prolongation caused by toxic doses of highly lipid-soluble neuropsychiatric drugs (amitriptyline, trazodone, quetiapine, lamotrigine, and citalopram) which are resistant to supportive treatment, leading to improved recovery from neuropsychiatric drug toxicity. However, more studies on large cohorts and analyses using many case reports are needed to clarify the effects of lipid emulsion resuscitation on neuropsychiatric drug toxicity and its underlying mechanisms.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Data curation: Yeran Hwang.

Formal analysis: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Funding acquisition: Ju-Tae Sohn.

Investigation: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Methodology: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Project administration: Ju-Tae Sohn.

Resources: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Software: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Supervision: Ju-Tae Sohn.

Validation: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Visualization: Ju-Tae Sohn.

Writing – original draft: Ju-Tae Sohn.

Writing – review & editing: Yeran Hwang, Ju-Tae Sohn.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- GCS

- Glasgow Coma Scale

- QTc

- corrected QT interval

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1I1A3040332). Ju-Tae Sohn is currently receiving NRF-2021R1I1A3040332 by the NRF.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Hwang Y, Sohn J-T. Effect of lipid emulsion on neuropsychiatric drug-induced toxicity: A narrative review. Medicine 2024;103:11(e37612).

References

- [1].Lee SH, Sohn JT. Mechanisms underlying of lipid emulsion resuscitation for drug toxicity: a narrative review. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2023;76:171–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lee SH, Kim S, Sohn JT. Lipid emulsion treatment for drug toxicity caused by nonlocal anesthetic drugs in pediatric patients: a narrative review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2023;39:53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ok SH, Park M, Sohn JT. Lipid emulsion treatment of nonlocal anesthetic drug toxicity. Am J Ther. 2020;28:e742–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cao D, Heard K, Foran M, et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion in the emergency department: a systematic review of recent literature. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sirianni AJ, Osterhoudt KC, Calello DP, et al. Use of lipid emulsion in the resuscitation of a patient with prolonged cardiovascular collapse after overdose of bupropion and lamotrigine. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:412–5, 415.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Niimi N, Yuki K, Zaleski K. Long QT syndrome and perioperative torsades de pointes: what the anesthesiologist should know. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36:286–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elgazzar FM, Elgohary MS, Basiouny SM, et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion as an adjuvant therapy of acute clozapine poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40:1053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Taftachi F, Sanaei-Zadeh H, Sepehrian B, et al. Lipid emulsion improves Glasgow Coma Scale and decreases blood glucose level in the setting of acute non-local anesthetic drug poisoning – a randomized controlled trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(suppl 1):38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hori K, Matsuura T, Tsujikawa S, et al. Lipid emulsion facilitates reversal from volatile anesthetics in a rodent model. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bhide A, Shah PS, Acharya G. A simplified guide to randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Available at: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [access date February 12, 2024].

- [13].Angel-Isaza AM, Bustamante-Cristancho LA, Uribe-B FL. Successful outcome following intravenous lipid emulsion rescue therapy in a patient with cardiac arrest due to amitriptyline overdose. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e922206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Warnant A, Gerard L, Haufroid V, et al. Coma reversal after intravenous lipid emulsion therapy in a trazodone-poisoned patient. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2020;43:31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bornstein K, Montrief T, Anwar Parris M. Successful management of adolescent bupropion overdose with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2019;8:242–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Otte S, Fischer B, Sayk F. Successful lipid rescue therapy in a case of severe amitriptyline/quetiapine intoxication. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2018;113:305–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Purg D, Markota A, Grenc D, et al. Low-dose intravenous lipid emulsion for the treatment of severe quetiapine and citalopram poisoning. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2016;67:164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bucklin MH, Gorodetsky RM, Wiegand TJ. Prolonged lipemia and pancreatitis due to extended infusion of lipid emulsion in bupropion overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51:896–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lung DD, Wu AH, Gerona RR. Cardiotoxicity in a citalopram and olanzapine overdose. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bartos M, Knudsen K. Use of intravenous lipid emulsion in the resuscitation of a patient with cardiovascular collapse after a severe overdose of quetiapine. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51:501–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nair A, Paul FK, Protopapas M. Management of near fatal mixed tricyclic antidepressant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor overdose with Intralipid®20% emulsion. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41:264–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Levine M, Brooks DE, Franken A, et al. Delayed-onset seizure and cardiac arrest after amitriptyline overdose, treated with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kiberd MB, Minor SF. Lipid therapy for the treatment of a refractory amitriptyline overdose. CJEM. 2012;14:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harvey M, Cave G. Case report: successful lipid resuscitation in multi-drug overdose with predominant tricyclic antidepressant toxidrome. Int J Emerg Med. 2012;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Blaber MS, Khan JN, Brebner JA, et al. “Lipid rescue” for tricyclic antidepressant cardiotoxicity. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:465–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Boegevig S, Rothe A, Tfelt-Hansen J, et al. Successful reversal of life threatening cardiac effect following dosulepin overdose using intravenous lipid emulsion. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:337–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Weinberg G, Di Gregorio G, Hiller D, et al. Reversal of haloperidol-induced cardiac arrest by using lipid emulsion. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:737–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Taylor R, Burg J, Mullen J. A case of trazodone overdose successfully rescued with lipid emulsion therapy. Cureus. 2020;12:e10864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Avcil M, Kapçi M, Yavaşoğlu I, et al. Simultaneous use of intravenous lipid emulsion and plasma exchange therapies in multiple drug toxicity. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:577–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chavez P, Casso Dominguez A, Herzog E. Evolving electrocardiographic changes in lamotrigine overdose: a case report and literature review. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2015;15:394–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Le Fevre P, Gosling M, Acharya K, et al. Dramatic resuscitation with intralipid in an epinephrine unresponsive cardiac arrest following overdose of amitriptyline and propranolol. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016218281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Radley D, Droog S, Barragry J, et al. Survival following massive amitriptyline overdose: the use of intravenous lipid emulsion therapy and the occurrence of acute respiratory distress. J Intensive Care Soc. 2015;16:181–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Herrman NWC, Kalisieski MJ, Fung C. Bupropion overdose complicated by cardiogenic shock requiring vasopressor support and lipid emulsion therapy. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:e47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Scholten HJ, Nap A, Bouwman RA, et al. Intralipid as antidote for tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs: a case report. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:1076–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hieger MA, Peters NE. Lipid emulsion therapy for quetiapine overdose. Am J Ther. 2020;27:e518–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sabah KMN, Chowdhury AW, Islam MS, et al. Amitriptyline-induced ventricular tachycardia: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schroeder I, Zoller M, Angstwurm M, et al. Venlafaxine intoxication with development of takotsubo cardiomyopathy: successful use of extracorporeal life support, intravenous lipid emulsion and CytoSorb®. Int J Artif Organs. 2017;40:358–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Berthe G, Tonglet M, Bertrand X, et al. How I treat … a poisoning with tricyclic antidepressants: potential role of a treatment with lipid emulsion. Rev Med Liège. 2017;72:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Odigwe CC, Tariq M, Kotecha T, et al. Tricyclic antidepressant overdose treated with adjunctive lipid rescue and plasmapheresis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:284–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ramasubbu B, James D, Scurr A, et al. Serum alkalinisation is the cornerstone of treatment for amitriptyline poisoning. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016214685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Matsumoto H, Ohnishi M, Takegawa R, et al. Effect of lipid emulsion during resuscitation of a patient with cardiac arrest after overdose of chlorpromazine and mirtazapine. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:1541.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Eren Cevik S, Tasyurek T, Guneysel O. Intralipid emulsion treatment as an antidote in lipophilic drug intoxications. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Agarwala R, Ahmed SZ, Wiegand TJ. Prolonged use of intravenous lipid emulsion in a severe tricyclic antidepressant overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10:210–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Arslan ED, Demir A, Yilmaz F, et al. Treatment of quetiapine overdose with intravenous lipid emulsion. Keio J Med. 2013;62:53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Perza MN, Schneider LA, Rosini JM. Suspected tricyclic antidepressant overdose successfully treated with lipids. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39:296–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hendron D, Menagh G, Sandilands EA, et al. Tricyclic antidepressant overdose in a toddler treated with intravenous lipid emulsion. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McAllister RK, Tutt CD, Colvin CS. Lipid 20% emulsion ameliorates the symptoms of olanzapine toxicity in a 4-year-old. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1012.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yurtlu BS, Hanci V, Gür A, et al. Intravenous lipid infusion restores consciousness associated with olanzapine overdose. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:914–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Castanares-Zapatero D, Wittebole X, Huberlant V, et al. Lipid emulsion as rescue therapy in lamotrigine overdose. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Dagtekin O, Marcus H, Müller C, et al. Lipid therapy for serotonin syndrome after intoxication with venlafaxine, lamotrigine and diazepam. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:93–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bowler M, Nethercott DR. Two lessons from the empiric management of a combined overdose of liraglutide and amitriptyline. A A Case Rep. 2014;2:28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bowler M, Nethercott DR. Intravenous lipid emulsion in a case of trazodone overdose. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022;24:21cr–02994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nishimura T, Maruguchi H, Nakao A, et al. Unusual complications from amitriptyline intoxication. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017219257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hillyard SG, Barrera-Groba C, Tighe R. Intralipid reverses coma associated with zopiclone and venlafaxine overdose. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:582–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yeniocak S, Kalkan A, Metin DD, et al. Successful intravenous lipid emulsion therapy: olanzapine intoxication. Acute Med. 2018;17:96–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Westrol MS, Awad NI, Bridgeman PJ, et al. Use of an intravascular heat exchange catheter and intravenous lipid emulsion for hypothermic cardiac arrest after cyclobenzaprine overdose. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2015;5:171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Finn SD, Uncles DR, Willers J, et al. Early treatment of a quetiapine and sertraline overdose with intralipid. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cobilinschi C, Mirea L, Andrei CA, et al. Biodetoxification using intravenous lipid emulsion, a rescue therapy in life-threatening quetiapine and venlafaxine poisoning: a case report. Toxics. 2023;11:917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Laffin RC, Cunningham AM, Fitzgerald SA, et al. Use of iatrogenic lipid emulsion and subsequent plasmapheresis for the treatment of amitriptyline overdose. Case Rep Crit Care. 2022;2022:1090795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Eid F, Takla A, Eid MM, et al. Successful management of severe bupropion toxicity with lipid emulsion therapy: a complex case report and literature review. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2023;10:004025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Şimşek M, Yildirim F, Şahin H, et al. Succesful use of lipid emulsion Theraphy in a case of extremely high dose olanzapine intoxication. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2023;51:65–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Weinberg GL. Lipid emulsion infusion: resuscitation for local anesthetic and other drug overdose. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Siebrands CC, Schmitt N, Friederich P. Local anesthetic interaction with human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) channels: role of aromatic amino acids Y652 and F656. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].De Diego C, Zaballos M, Quintela O, et al. Bupivacaine toxicity increases transmural dispersion of repolarization, developing of a Brugada-like pattern and ventricular arrhythmias, which is reversed by lipid emulsion administration. Study in an experimental porcine model. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2019;19:432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bora S, Erdoğan MA, Yiğittürk G, et al. The effects of lipid emulsion, magnesium sulphate and metoprolol in amitriptyline-induced cardiovascular toxicity in rats. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2018;18:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Fettiplace MR, Ripper R, Lis K, et al. Rapid cardiotonic effects of lipid emulsion infusion*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:e156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shin IW, Hah YS, Kim C, et al. Systemic blockage of nitric oxide synthase by L-NAME increases left ventricular systolic pressure, which is not augmented further by Intralipid®. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10:367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Clemons J, Jandu A, Stein B, et al. Efficacy of lipid emulsion therapy in treating cardiotoxicity from diphenhydramine ingestion: a review and analysis of case reports. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60:550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Spence AG. Lipid reversal of central nervous system symptoms of bupivacaine toxicity. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:516–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lee SH, Park M, Ok SH, et al. Early lipid emulsion treatment of central nervous system symptoms induced by ropivacaine toxicity: a case report. Am J Ther. 2020;28:e736–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zhou JX, Luo NF, Liang XM, et al. The efficacy and safety of intravenous emulsified isoflurane in rats. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Li Q, Yang D, Liu J, et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion improves recovery time and quality from isoflurane anaesthesia: a double-blind clinical trial. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Heinonen JA, Litonius E, Backman JT, et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion entraps amitriptyline into plasma and can lower its brain concentration – an experimental intoxication study in pigs. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;113:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].French D, Smollin C, Ruan W, et al. Partition constant and volume of distribution as predictors of clinical efficacy of lipid rescue for toxicological emergencies. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:801–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ok SH, Shin IW, Lee SH, et al. Lipid emulsion alleviates the vasodilation and mean blood pressure decrease induced by a toxic dose of verapamil in isolated rat aortae and an in vivo rat model. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2018;37:636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ok SH, Choi MH, Shin IW, et al. Lipid emulsion inhibits apoptosis induced by a toxic dose of verapamil via the delta-opioid receptor in H9c2 rat cardiomyoblasts. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17:344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Harvey MG, Cave GR. Intralipid infusion ameliorates propranolol-induced hypotension in rabbits. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Browne A, Harvey M, Cave G. Intravenous lipid emulsion does not augment blood pressure recovery in a rabbit model of metoprolol toxicity. J Med Toxicol. 2010;6:373–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Fettiplace MR, Weinberg G. The mechanisms underlying lipid resuscitation therapy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:138–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Perichon D, Turfus S, Gerostamoulos D, et al. An assessment of the in vivo effects of intravenous lipid emulsion on blood drug concentration and haemodynamics following oro-gastric amitriptyline overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51:208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Fettiplace MR, Lis K, Ripper R, et al. Multi-modal contributions to detoxification of acute pharmacotoxicity by a triglyceride micro-emulsion. J Control Release. 2015;198:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Robin AP, Nordenström J, Askanazi J, et al. Plasma clearance of fat emulsion in trauma and sepsis: use of a three-stage lipid clearance test. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1980;4:505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Fettiplace MR, Akpa BS, Rubinstein I, et al. Confusion about infusion: rational volume limits for intravenous lipid emulsion during treatment of oral overdoses. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Fettiplace MR, Pichurko AB. Heterogeneity and bias in animal models of lipid emulsion therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Levine M, Skolnik AB, Ruha AM, et al. Complications following antidotal use of intravenous lipid emulsion therapy. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10:10–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Turner-Lawrence DE, Kerns W. Intravenous fat emulsion: a potential novel antidote. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4:109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Fettiplace MR, Weinberg G. Lipid emulsion for xenobiotic overdose: PRO. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;89:1708–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wanten GJ, Calder PC. Immune modulation by parenteral lipid emulsions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1171–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].AAGBA. AAGBI safety. Available at: http://p-h-c.com.au/doc/Local_Anaesthesia_Toxicity.pdf [access date January 30, 2023].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.