Abstract

Uterine contractions during labor and preterm labor are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including hormones and inflammatory mediators. This complexity may contribute to the limited efficacy of current tocolytics for preterm labor, a significant challenge in obstetrics with 15 million cases annually and approximately 1 million resulting deaths worldwide. We have previously shown that the myometrium expresses bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs) and that their activation leads to uterine relaxation. Here, we investigated whether the selective TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline can induce relaxation across a spectrum of human uterine contractions and whether the underlying mechanism involves changes in intracellular Ca2+ signaling. We performed experiments using samples from pregnant women undergoing scheduled cesarean delivery, assessing responses to various inflammatory mediators and oxytocin with and without phenanthroline. Our results showed that phenanthroline concentration-dependently inhibited contractions induced by PGF2α, U46619, 5-HT, endothelin-1 and oxytocin. Furthermore, in hTERT-infected human myometrial cells exposed to uterotonics, phenanthroline effectively suppressed the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by PGF2α, U46619, oxytocin, and endothelin-1. These results suggest that the selective TAS2R5 agonist may not only significantly reduce uterine contractions but also decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels. This study highlights the potential development of TAS2R5 agonists as a new class of uterine relaxants, providing a novel avenue for improving the management of preterm labor.

Keywords: Bitter taste receptors, phenanthroline, uterine contraction, preterm birth, uterine relaxant

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Appropriate uterine contraction is vital for normal reproduction, encompassing processes that include menstruation, embryo implantation, and parturition (Bulletti and de Ziegler, 2005; Bulletti et al., 2000; Rosen and Yogev, 2023; Smith, 2007). Abnormalities in uterine contraction underlie or contribute to a wide range of gynecological and obstetric disorders, including endometriosis, adenomyosis, dysmenorrhea, uterine dystocia, and preterm birth (LeFevre et al., 2021; Leyendecker and Wildt, 2011; MacGregor et al., 2023; Romero et al., 2014). Consequently, the identification of uterine contraction agonists and relaxants holds critical importance in both gynecology and obstetrics.

Preterm birth presents a significant challenge in obstetrics, with fifteen million cases annually and approximately one million resultant deaths worldwide (Blencowe et al., 2013; Chawanpaiboon et al., 2019). Tocolysis, the relaxation of uterine smooth muscle, is commonly employed to manage spontaneous preterm labor/birth (Arman et al., 2023; Coler et al., 2021; Di Renzo et al., 2018; Hanley et al., 2019; Munoz-Perez et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2022; Wray et al., 2023), which accounts for 50% of all preterm births. While existing tocolytics do not directly improve neonatal outcomes, they serve three critical purposes: 1) providing the fetus additional developmental and maturation time in utero, 2) permitting time for the administration of prenatal corticosteroids, which facilitate fetal organ maturation, and 3) enabling the transfer of the pregnant woman to a hospital equipped for higher level neonatal care (Arman et al., 2023; Coler et al., 2021; Di Renzo et al., 2018; Hanley et al., 2019; Munoz-Perez et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2022; Wray et al., 2023). Despite these benefits, current tocolytic agents demonstrate limited effectiveness, particularly beyond providing a 48-hour delay. This underscores a significant unmet need and offers an opportunity to identify new classes of uterine relaxants.

The development of effective tocolytics is challenged by the complex biological processes entailed in parturition. Successful parturition necessitates the activation of at least four common pathways: cervical ripening, membrane decidual activation, rupture of the fetal membranes, and the transition from a quiescent uterus during pregnancy to a powerfully contractile organ during labor (Challis et al., 2000; Leimert et al., 2021; Menon et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2014). Evidence suggests that premature activation of uterine transition can instigate preterm labor (Challis et al., 2000; Leimert et al., 2021; Menon et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2014). Moreover, research over recent decades has revealed that, alongside hormonal influences and mechanical stretch, intrauterine inflammation plays a pivotal role in catalyzing the uterine transition in both term and preterm labor (Bonney and Johnson, 2019; Gilman-Sachs et al., 2018; Gimeno-Molina et al., 2022; Leimert et al., 2021; Tersigni et al., 2020; Zhang and Wei, 2021).

Throughout late gestation and labor, the uterus experiences an influx of immune cells that release a variety of cytokines and chemokines (Bonney and Johnson, 2019; Gilman-Sachs et al., 2018; Gimeno-Molina et al., 2022; Tersigni et al., 2020; Zhang and Wei, 2021). These mediators activate signaling cascades that augment the expression of contractile proteins, such as connexin43, prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2α) receptor, and oxytocin receptor. Additionally, certain inflammatory mediators can directly induce uterine contractions. Compounds such as prostaglandins, endothelin-1, and serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) have been implicated as key contributors to both term and preterm labor (Breuiller-Fouche et al., 2005; Bytautiene et al., 2008; Chibbar et al., 1993; Cordeaux et al., 2008; Fischer et al., 2008; Garfield et al., 2006; Hirst et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2017; Koren et al., 1965; Olund et al., 1980; Osada et al., 1997; Peiris et al., 2021; Romero et al., 1994; Romero et al., 1987; Uvnas-Moberg et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2008; Yallampalli and Garfield, 1994).

Given the pivotal role of inflammatory responses in parturition, it has become an attractive target for research into the prevention of preterm labor prevention. Hypothetically, blocking uterine contractions instigated by inflammatory mediators could halt the progression of spontaneous preterm labor. However, due to the array of inflammatory mediators that induce uterine contractions, preventing preterm uterine activity would likely necessitate an agent capable of reversing or preventing uterine contractions caused by various inflammatory mediators.

Bitter taste, one of five basic taste qualities, is critical to the survival of animals including humans, as it promotes avoidance of harmful toxins and noxious substances (Behrens and Meyerhof, 2009; Chandrashekar et al., 2000). It was long believed that bitter taste receptors, also known as Taste 2 receptors (TAS2Rs) which initiate the sensation of bitterness, were only present in the specialized epithelial cells in the taste buds of the tongue (Chandrashekar et al., 2000; Wong et al., 1996). However, these receptors have increasingly been found in extra-oral organs and participate in a variety of biological activities (Avau and Depoortere, 2016; Behrens and Lang, 2022; Bloxham et al., 2020; Carey et al., 2016; Harmon et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2017; Tuzim and Korolczuk, 2021).

We recently discovered that TAS2Rs and their downstream signaling components are expressed in uterine smooth muscle (Zheng et al., 2017). Strikingly, we found that chloroquine, an agonist of multiple TAS2Rs, more effectively relax mouse and human uterine smooth muscle - which has been pre-contracted by membrane depolarization or oxytocin - than other clinically-used tocolytics like the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin and the calcium channel blocker nifedipine. In mice, chloroquine also provides better prevention of preterm labor induced by lipopolysaccharide and the progesterone receptor antagonist RU486 than other tocolytics (Zheng et al., 2017).

However, bitter tastants, such as chloroquine which activates multiple TAS2Rs (Meyerhof et al., 2010), might lead to increased side effects. This is because TAS2Rs are widely expressed across various organs, encompassing both reproductive and non-reproductive systems (Avau and Depoortere, 2016; Behrens and Lang, 2022; Bloxham et al., 2020; Carey et al., 2016; Harmon et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2017; Tuzim and Korolczuk, 2021). Interestingly, we have found that phenanthroline, a bitter tastant that selectively activates TAS2R5 agonist (Meyerhof et al., 2010), can reverse human uterine contractions induced by membrane depolarization and oxytocin (Zheng et al., 2017). In this study, we tested whether phenanthroline can relax uterine contraction mediated by different inflammatory mediators, considering their significant role in uterine contraction during parturition and/or preterm labor. If this selective TAS2R5 agonist proves effective, we aimed to determine whether a common process underpins this broad uterine relaxation effect. We focused on PGF2α, oxytocin, U46619 (a thromboxane A2 (TP) receptor agonist), 5-HT, and endothelin-1 as uterotonics due to the well-established roles these compounds or their receptors play in the term and/or preterm labor pathway. Furthermore, we delved into Ca2+ signaling as a potential unified mechanism for the uterine relaxation effect of bitter tastants, given that Ca2+ is the primary signal for uterine contraction (Aguilar and Mitchell, 2010; Sanborn, 2000; Wray and Arrowsmith, 2021).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and cohort

Pregnant women who underwent a scheduled cesarean delivery for clinical indications at UMass Memorial Medical Center were screened and consented to participate in uterine specimen donation. Patients with blood-borne infections, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV, were excluded. At the time of surgery, none of the women had used tocolytics. This study was approved by the UMass Chan Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB#: H00014516).

2.2. Specimen collection

Uterine tissues, approximately 5 cm × 1.5 cm × 3 cm in size, were excised from the upper edge of the lower segment transverse uterine incision following the delivery of the infant and placenta, and before the closure of the hysterotomy. These uterine biopsies were immediately placed in DMEM/F-12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) kept at 4°C, and transported to the laboratory within 2 hours of collection.

2.3. Measurement of uterine smooth muscle contraction

Once the samples were transferred to the laboratory, the endometrium and connective tissue were removed under a dissecting microscope in a petri dish containing ice-cold, oxygenated Krebs physiological solution (KPS). The KPS consisted of (mM): 118.07 NaCl, 4.69 KCl, 2.52 CaCl2, 1.16 MgSO4, 1.01 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 11.10 glucose. The remaining myometrium was then placed in the oxygenated and ice-cold KPS until processed for force measurement. Experiments were conducted on the same day, typically within 8 hours of surgery. Previous studies have demonstrated that uterine samples stored, up to 48 hours, under similar conditions generate robust contractile responses to agonists (Ko et al., 1990; Yu et al., 1995). Hence, the uterine tissues used in this study were likely healthy without any significant deterioration.

Uterine specimens were cut into longitudinal strips (5 mm × 1.5 mm × 1.0 mm), which were then transferred to 5 ml muscle baths containing oxygenated KPS at 37°C. The strips were mounted on a wire myograph chamber (610-M; Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark), and tension was measured with a PowerLab recorder (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Each smooth muscle strip was equilibrated for 60 minutes, following which a 0.1 g load was applied.

To assess the contractile response, each strip was stimulated twice with KCl (60 mM), with each stimulation lasting approximately 5 minutes. There was a 10-minute interval between these KCl stimuli before proceeding with other treatments. Each treatment involving a test compound had a duration exceeding 5 minutes to ensure the full development of the response. The order and duration of the test compound treatments are indicated in the accompanying figures and their respective captions.

To analyze the contractile response to each test compound, we used the response produced by the second KCl treatment as the reference. This approach was necessitated by three factors: (1). KCl and contractile agonists did not consistently induce sustained, uniform contractions across strips obtained from different donors. (2). There were variations in treatment durations between KCl and contractile agonists. (3). Variations in treatment times occurred due to manual administration and washout procedures.

To address these considerations, we first calculated the average force produced by each treatment by taking the area under the force curve (AUC) (which has units of millinewtons (mN) x minutes) and dividing it by the treatment duration in minutes (resulting in final units of mN). Subsequently, we normalized the average force for each test compound to the average force produced by the second KCl treatment in the same strip x100. We call the final (unitless) result the 'unitary AUC’.

2.4. hTERT-HM cell culture

The hTERT-infected human myometrial (hTERT-HM) cells, an immortalized cell line that maintains the characteristics of primary human uterine smooth muscle cells (as they express smooth muscle cell contractile markers and functional receptors including TAS2Rs and the oxytocin receptor (Condon et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2017), were cultured in DMEM/F-12 containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The culture medium was changed every other day. When the cells reached 90% confluence, they were detached with 0.25% (w/v) trypsin and then reseeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2.

2.5. Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i)

hTERT-HM cells, whose intracellular [Ca2+]i can be increased by various contractile agonists (Condon et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2017), were loaded with 2 μM Cal-520 acetoxymethyl ester calcium indicator (AAT Bioquest, Pleasanton, CA) in DMEM/F-12 for 40 minutes at 37°C, followed by 30 minutes of de-esterification in indicator-free culture medium. Fluorescence Ca2+ images in hTERT-HM cells were captured using a custom-built wide-field digital imaging system (Qu et al., 2021). The camera was interfaced with an IX71, Olympus inverted microscope with a 20x 1.3 NA objective (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The 488 nm line of an argon ion laser served as a fluorescence excitation source, with a shutter controlling exposure time; emission of the Ca2+ indicator was observed at wavelengths greater than 500 nm. Images were captured at a rate of 1 Hz, with subsequent image processing and analysis conducted using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). [Ca2+]i was expressed as (Ft − F0)/F0*100, i.e., ΔF/F0(%), where Ft represents the fluorescence intensity of the entire cell at a given time point and F0 represents the average Ft at rest, determined by averaging the Ft of the first 20 images before the application of the test agents.

2.6. Protocols of phenanthroline treatment in Ca2+ measurement

Our preliminary studies indicated that oxytocin, U46619, and PGF2α could repeatedly increase [Ca2+]i following a 15-minute recovery period. However, endothelin-1 only increased [Ca2+]i upon its first application, and 5-HT did not result in a detectable increase in [Ca2+]i. Consequently, we employed two different protocols to evaluate the effect of phenanthroline on contractile agonist-induced increases in [Ca2+]i. For oxytocin, U46619, and PGF2α, hTERT-HM cells were stimulated with two pulses of an agonist, with phenanthroline applied for 15 minutes prior to the second pulse. In the absence of phenanthroline, the calcium response to the second pulse of the agonist was not as substantial as the response to the first pulse - this decreased response is referred to as a “rundown.” The effect of phenanthroline was quantified by comparing the peak [Ca2+]i induced by the second pulse to that induced by the first pulse. For endothelin-1, hTERT-HM cells were stimulated with a pulse of the agonist, either with or without a 15-minute pretreatment with phenanthroline. The effect of phenanthroline on the endothelin-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is expressed as the ratio of the peak [Ca2+]i. with and without phenanthroline, respectively.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SEM, with ‘n’ indicating the number of uterine sample donors or myometrial cells. All concentration-response curves were subjected to ANOVA. When results reached statistical significance, post hoc Dunnett’s tests were performed. To assess the effect of phenanthroline on basal [Ca2+]i, we used a paired t-test. The significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of human subjects and uterine samples

In this study, we obtained consent from 14 pregnant women, with gestations ranging from 37 to 40 weeks, to donate their uterine samples. On the day of their scheduled cesarean delivery, we collected uterine tissues, approximately 5 cm × 1.5 cm × 3 cm in size, excised from the upper edge of the lower uterine segment transverse hysterotomy incision from each participant. These patients were not in labor at the time of cesarean delivery and tissue collection. Uterine tissues were promptly delivered to the laboratory within two hours following the procedure. All specimens were processed and assessed for contractile responses on the same day as their respective surgeries.

3.2. Effects of the TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline on human uterine contractions induced by inflammatory contractile mediators and the hormone oxytocin

To minimize potential variability in contractions arising from factors such as differences in uterine strip size, patient health conditions, and tissue decomposition, we conducted contraction experiments with two reference control components. First, we normalized agonist-induced contractions relative to KCl-induced contractions in the same strip. Second, we tested each contractile agonist for its response in the presence of phenanthroline in one strip and in its absence in another strip from the same patient.

When normalizing relative to KCl, each strip underwent two treatments with 60 mM KCl before being tested with contractile agonists. We normalized the contractile responses relative to the second KCl treatment because it produced a stable contraction compared to the first KCl treatment.

As detailed in the results below, KCl and contractile agonists induced either phasic or biphasic contractions, with the latter involving a peak contraction followed by a sustained contraction. As previously mentioned, the treatment durations with KCl and contractile agonists differed, and there were variations in the treatment durations for contractile agonists due to manual administration and washout. Therefore, to better quantify these dynamic changes in contraction and minimize errors, we compared unitary AUC for each test compound, as described in the Methods section.

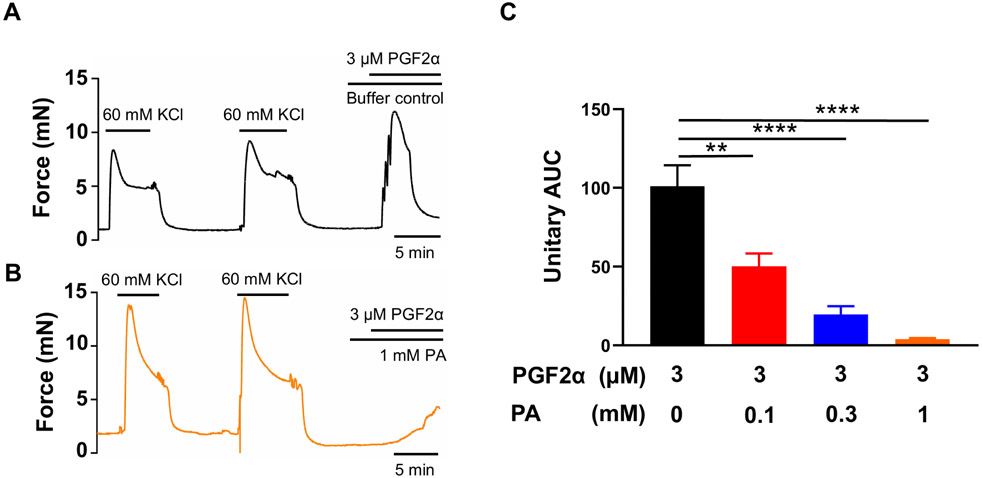

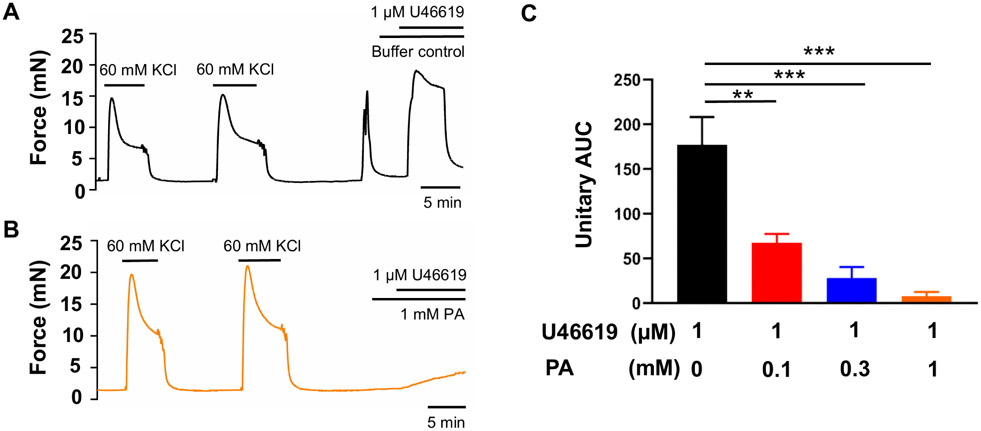

An increase in cyclooxygenase-2 expression and the resulting increase in prostaglandin levels are key processes in the uterine transition from quiescence to parturition (Fischer et al., 2008; Hirst et al., 1995; Olund et al., 1980; Peiris et al., 2021; Romero et al., 1994; Romero et al., 1987). Therefore, we examined the effect of the TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline on prostaglandin-induced contractions. Figure 1 shows that 3 μM PGF2α generated a force similar to that produced by 60 mM KCl, and phenanthroline reduced PGF2α-induced contraction in a concentration-dependent manner. Specifically, 100 μM phenanthroline reduced PGF2α-induced contraction by approximately 50%, whereas 1 mM phenanthroline essentially abolished it (Figure 1B and 1C). U46619, a TP receptor agonist, at 1 μM caused a ~1.7-fold increase in contraction compared to 60 mM KCl. Phenanthroline at 100 μM suppressed ~65% of the contraction induced by U46619, and at 1 mM, it abolished it (Figure 2).

Figure 1. TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits PGF2α-induced human uterine contractions.

Representative traces of uterine strip tension changes in response to 3 μM PGF2α in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 1 mM (B). (C) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of PGF2α-induced contraction. Data are represented as means ± SEM (n= 6 strips from 6 donors) and expressed as unitary AUC, i.e., AUC/treatment duration for PGF2α /AUC/treatment duration for 2nd KCl x 100. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

Figure 2. Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits U46619-induced human uterine contractions.

Representative traces of uterine strip tension changes in response to 1 μM U46619 in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 1 mM (B). (C) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of U46619-induced contraction. Data are represented as means ± SEM (n= 6 strips from 6 donors) and expressed as unitary AUC as defined in the Methods and Figure 1. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

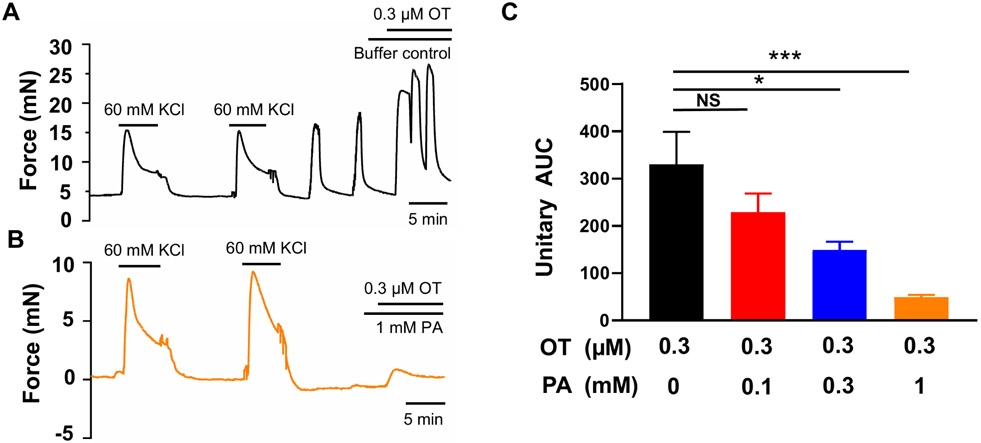

Oxytocin (OT) plays a significant role at the onset of labor and during parturition (Chibbar et al., 1993; Fuchs et al., 1982; Kim et al., 2017; Uvnas-Moberg et al., 2019). As shown in Figure 3, 0.3 μM oxytocin induced a contraction approximately 3-fold greater than that elicited by 60 mM KCl. Phenanthroline at 100 μM reduced the contraction induced by OT by around 20%, although this reduction was not statistically significant. However, 300 μM phenanthroline significantly suppressed the OT-induced contraction, and at 1 mM, it suppressed approximately 90% of the contraction.

Figure 3. Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits oxytocin (OT)-induced human uterine contractions.

Representative traces of uterine strip tension changes in response to 0.3 μM OT in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 1 mM (B). (C) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of OT-induced contraction. Data are means ± SEM (n= 5 strips from 5 donors) and expressed as unitary AUC as defined in the Methods and Figure 1. NS, P>0.05; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

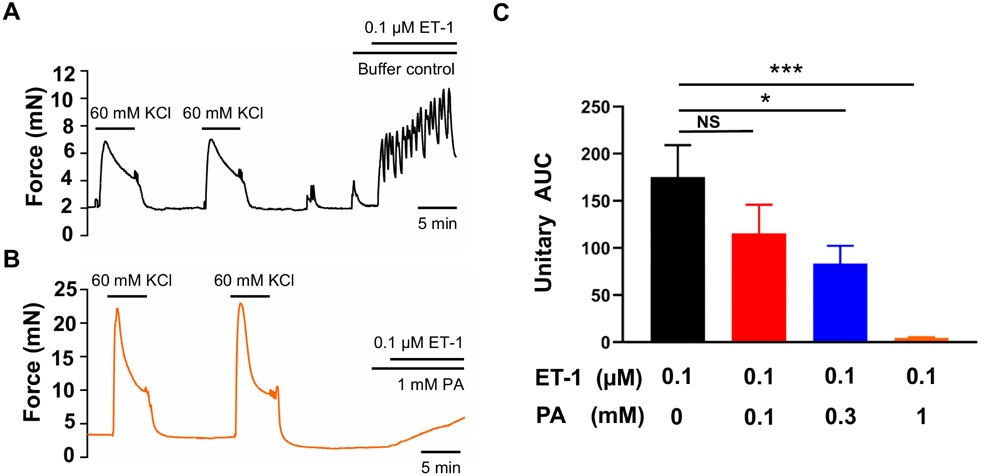

Endothelin is significantly elevated and causes uterine contraction during labor in humans (Breuiller-Fouche et al., 2005; Heluy et al., 1995; Osada et al., 1997; Yallampalli and Garfield, 1994) and may play a critical role in inflammation-associated preterm labor based on animal studies (Wang et al., 2008). We found that 0.1 μM ET-1 induced uterine contraction by 1.7-fold compared to 60 mM KCl. This contraction was significantly inhibited by 300 μM phenanthroline and abolished by 1 mM phenanthroline (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits ET-1-induced human uterine contractions.

Representative traces of uterine strip tension changes in response to 0.1 μM ET-1 in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 1 mM (B). (C) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of ET-1-induced contraction. Data are means ± SEM (n= 5 strips from 5 donors) and expressed unitary AUC as defined in the Methods and Figure 1. NS, P>0.05; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

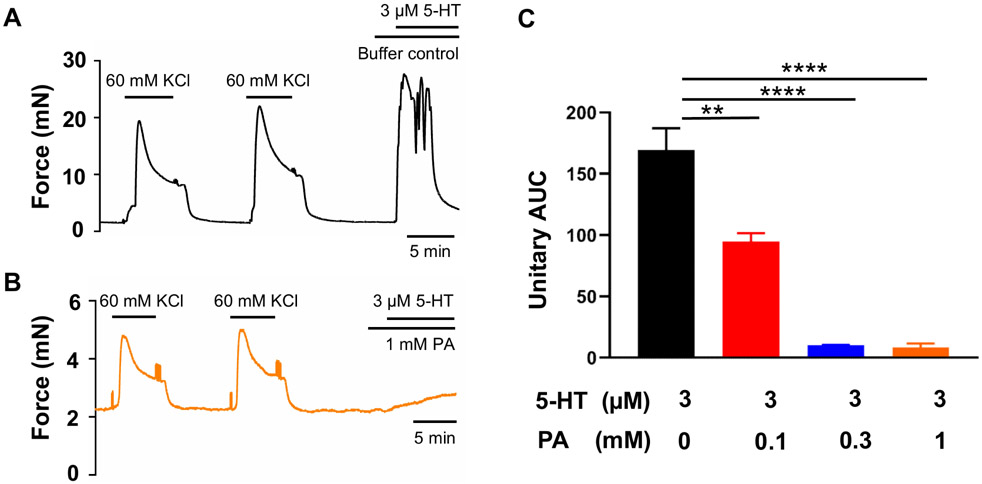

5-HT contracts human uterine smooth muscle at term and aberrant serotonin signaling has been implicated as a contributor to preterm labor (Bytautiene et al., 2008; Cordeaux et al., 2009; Garfield et al., 2006; Koren et al., 1965). Figure 5 shows that 3 μM 5-HT robustly contracted uterine smooth muscle, and phenanthroline concentration-dependently suppressed 5-HT-induced contraction and abolished it at both 300 μM and 1 mM.

Figure 5. Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits 5-HT-induced human uterine contractions.

Representative traces of uterine strip tension changes in response to 3 μM 5-HT in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 1 mM (B). (C) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of 5-HT-induced contraction. Data are means ± SEM (n= 5 strips from 5 donors) and expressed unitary AUC as defined in the Methods and Figure 1. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

3.3. Effects of phenanthroline on increase in intracellular Ca2+ induced by inflammatory contractile mediators and oxytocin

Having characterized the phenanthroline-induced relaxation of contractions induced by various inflammatory contractile mediators and oxytocin, we sought to identify a common cellular signal underlying this diverse relaxation. Because Ca2+ is the primary determinant of uterine smooth muscle contraction (Aguilar and Mitchell, 2010; Sanborn, 2000; Wray and Arrowsmith, 2021), we investigated whether phenanthroline interferes with Ca2+ signaling as a possible common mechanism. We employed hTERT-HM cells for this purpose because they are an immortalized cell line derived from human uterine smooth muscle cells (Condon et al., 2002), and express abundant TAS2R5 mRNA (Zheng et al., 2017).

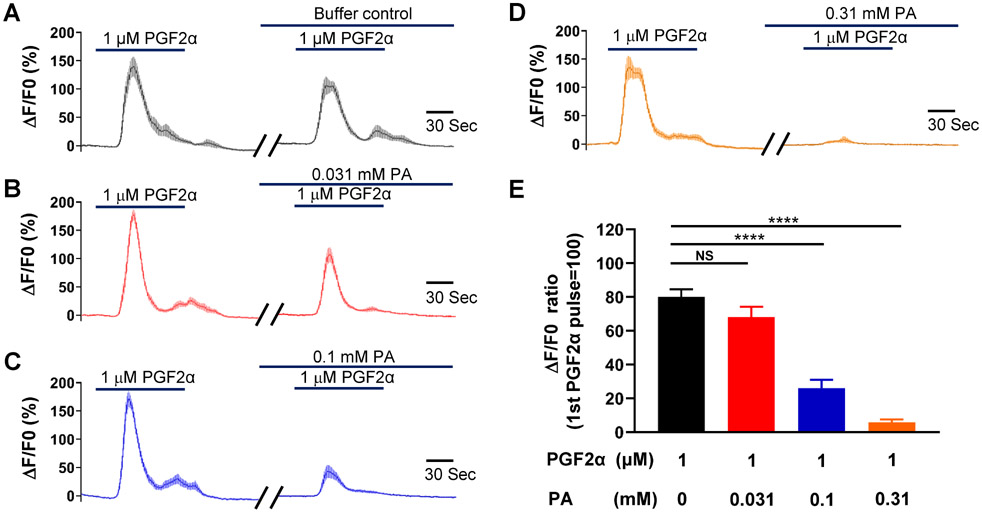

Because activation of TAS2R is likely to increase [Ca2+]i (Chandrashekar et al., 2000), we first examined the effect of phenanthroline on [Ca2+]i in hTERT-HM cells. We observed that 1 mM phenanthroline did not alter the basal [Ca2+]i (0.4±0.5% ΔF/F0(%); n=10; P>0.05 in a paired t-test comparing with vs without phenanthroline). Using a dual-pulse protocol, we noted a robust increase in [Ca2+]i upon the first stimulation of PGF2α, with approximately a 20% reduction upon the second stimulation (Figure 6). Phenanthroline did not alter the [Ca2+]i following the washout of PGF2α (Figure 6B-C) or other agonists (see Figures 7 and 8 below). However, when hTERT-HM cells were pretreated with phenanthroline, there was a concentration-dependent inhibition of the Ca2+ increase triggered by the second PGF2α application. At 1 mM, phenanthroline completely abolished the PGF2α-induced increase in [Ca2+]i.

Figure 6: Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits PGF2α-induced increase in intracellular calcium in hTERT-HM cells.

Time courses of calcium concentration changes in response to 1 μM PGF2α in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 0.031 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), and 0.31 mM (D). The gaps between two PGF2α treatments were 15 min. (E) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of PGF2α-induced increase in cytosolic calcium level. Data are means ± SEM (n = 20-28 cells) and expressed as the ratio of calcium increase peak induced by the second PGF2α application to that induced by the first PGF2α in A-D. NS, P >0.05; ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

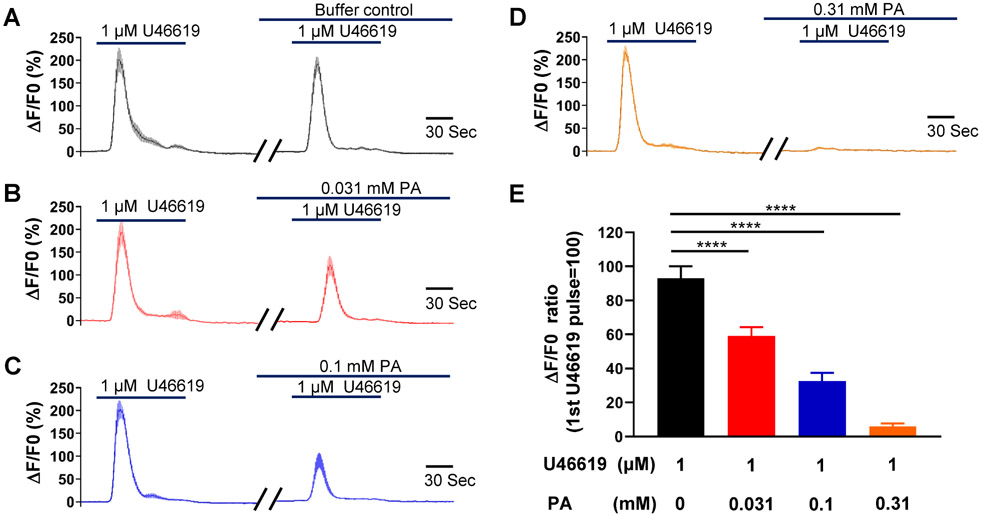

Figure 7: Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits U46619-induced increase in intracellular calcium in hTERT-HM cells.

Time courses of calcium concentration changes in response to 1 μM U46619 in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 0.031 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), and 0.310 mM (D). The gaps between two U46619 treatments are 15 min. (E) Summarized results on PA’s inhibition of U46619-induced increase in cytosolic calcium level. Data are means ± SEM (n = 20-30 cells) and expressed as the ratio of calcium increase peak by the second U46619 application to that by the first U46619 application in A-D. ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

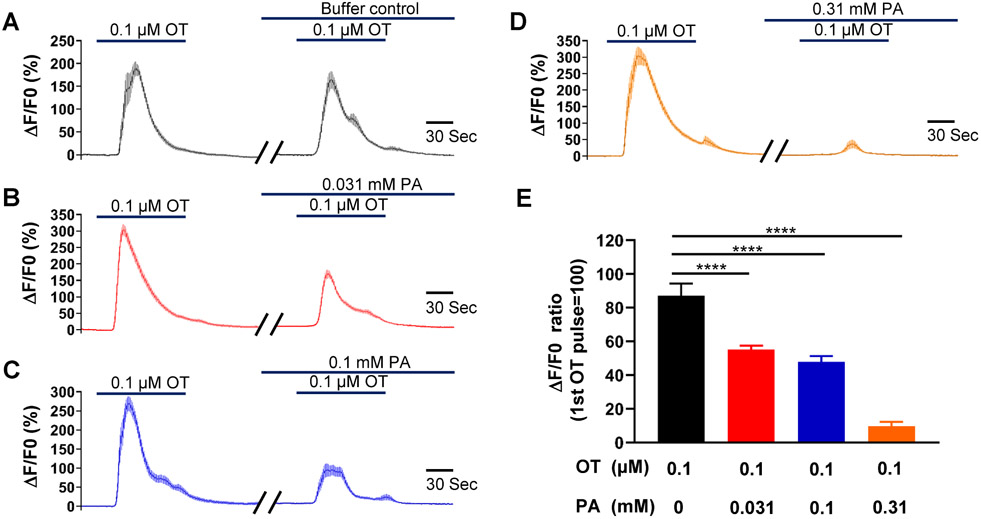

Figure 8: Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits oxytocin (OT)-induced increase in cytosolic calcium concentration in hTERT-HM cells.

Time courses of calcium concentration changes in response to 0.1 μM OT in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 0.031 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), and 0.31 mM (D). (E) Summarized results of PA’s inhibition of OT-induced increase in cytosolic calcium level. Data are means ± SEM (n = 20-28 cells) and expressed as the ratio of calcium increase peak induced by the second OT application to that induced by the first OT application in A-D. ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test following ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

Similar to PGF2α, U46619 robustly increased cytosolic Ca2+ during its first stimulation but did not cause as much Ca2+ rundown in its second application (Figure 7). As with PGF2α, phenanthroline concentration-dependently inhibited the Ca2+ increase induced by the second application of U46619, and at 1 mM, it abolished the U46619-induced increase in [Ca2+]i.

Figure 8 shows that oxytocin robustly increased [Ca2+]i during its first stimulation, with the response experiencing approximately a 10% rundown during its second stimulation. Phenanthroline concentration-dependently inhibited the oxytocin-induced rise in [Ca2+]i, and it was abolished at a phenanthroline concentration of 1 mM.

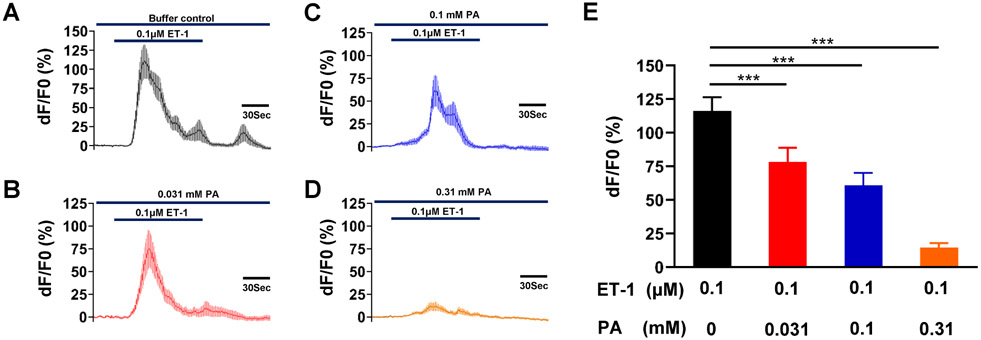

ET-1 increased cytosolic Ca2+ (Figure 9) but failed to increase it when reapplied after a 15-minute recovery. Therefore, to assess the effect of phenanthroline on the ET-1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i, we compared responses to a single application of ET-1 either with or without phenanthroline. Figure 9 shows that phenanthroline prevented ET-1 from increasing cytosolic Ca2+ in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 9: Phenanthroline (PA) concentration-dependently inhibits ET-1-induced increase in cytosolic calcium concentration in hTERT-HM cells.

Time courses of calcium concentration changes in response to 0.1 μM ET-1 in the absence of PA (A), and in its presence at 0.031 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), and 0.310 mM (D). (E) A comparison of the averaged calcium peaks calculated from the cells similar to those shown in A-D. Data are means ± SEM; n = 20 cells. *P<0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by the post hoc dunnett's test after ANOVA at the statistically significant level.

4. Discussion

Phenanthroline possesses two distinct known properties: it acts as a selective TAS2R5 agonist (Meyerhof et al., 2010) and inhibits Zn2+ metallopeptidases (Granato et al., 2015). The latter property stems from its ability to bind metal ions in enzymes. Our experiments indicated that phenanthroline neither affects basal Ca2+ levels in myometrial cells at rest nor after the washout of contractile agonists (see Figures 6-8). This is consistent with the fact that this compound has a much higher stability constant for Zn2+ (K= 2 x 106 M) compared to Ca2+ (K = 5 M) (Frederick et al., 1984). Moreover, the inhibition of metallopeptidases has been shown to potentiate uterine contraction induced by oxytocin and bradykinin (Ottlecz et al., 1991; Schriefer and Molineaux, 1993). This stands in contrast to our findings, where phenanthroline relaxed precontracted myometrial strips. Thus, it is more plausible that phenanthroline activates TAS2R5, leading to uterine relaxation.

Recent studies have highlighted the widespread distribution of TAS2Rs and their downstream components within the reproductive system, suggesting their potential importance in reproductive functions. In the male reproductive system, TAS2Rs have been identified in testicular tissues and sperm cells. Their activation has been implicated in the regulation of sperm chemotaxis, motility, and spermatogenesis (Fehr et al., 2007; Governini et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Luddi et al., 2019; Roemer et al., 2012). In the female reproductive system, TAS2Rs have been found in the myometrium, cervix, vagina, ovary, and placenta (Liu et al., 2017; Semplici et al., 2021; Wolfle et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2017). Their physiological roles in female reproduction remain largely unknown. Our previous study (Zheng et al., 2017) suggested that chloroquine, an agonist of several TAS2Rs, can relax uterine strips pre-contracted by membrane depolarization and oxytocin in both mice and humans. Moreover, chloroquine can prevent lipopolysaccharide- or RU486-induced preterm labor in mice, suggesting that TAS2R activation may be a promising strategy for treating preterm labor. Our present study provides additional evidence in support of this concept by showing that the selective TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline can also induce significant relaxation in pre-contracted uterine strips. This finding is significant as it underscores the potential of targeting a single TAS2R. This may result in fewer side effects compared to a multi-TAS2R agonist, given the widespread distribution of different TAS2Rs in extra-oral tissues throughout the entire human body including the respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, and urinary system (Avau and Depoortere, 2016; Behrens and Lang, 2022; Bloxham et al., 2020; Carey et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Tuzim and Korolczuk, 2021).

Given the complex and interactive nature of the mechanisms underlying both preterm and term labor, resulting from parallel and sequential changes in the endocrine system, uterine mechanics, and inflammation (Challis et al., 2000; Leimert et al., 2021; Menon et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2014; Vidal et al., 2022), it is improbable that a single treatment will suffice to prevent or reverse preterm labor (Keelan et al., 1997). Many agents, including beta-2 agonists and oxytocin receptor antagonists, have been studied but were found to be clinically ineffective in preventing or treating preterm birth (Wilson et al., 2022). The available tocolytics, such as nifedipine and indomethacin, only delay delivery by a few days (Wilson et al., 2022). We need to explore new classes of agents, beyond calcium channel blockers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, to expand our understanding of possible treatments for preterm labor. In light of our findings, TAS2R5 emerges as a potential target for the development of a new uterine relaxant.

Interestingly, the TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline can inhibit uterine contractions induced by various contractile agonists, including membrane depolarization (Zheng et al., 2017), oxytocin, and various contractile inflammatory mediators. This suggests that potential activation of TAS2R5 by phenanthroline may stimulate a common molecular mechanism that can counteract different receptor-mediated contractions. Our study reveals that one such mechanism is a decrease in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. However, further experiments are needed to determine the molecular basis for this decrease in the cytosolic Ca2+ level. It is plausible that this change is mediated by multiple mechanisms such as the activation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Deshpande et al., 2010), inhibition of inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptors (Tan and Sanderson, 2014), enhanced uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria (Talmon et al., 2019), or beta-gamma subunit-induced inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Zhang et al., 2013), because each of these mechanisms has been proposed to mediate relaxation in other smooth muscle tissues.

5. Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. We utilized human uterine biopsies from term gravidas, thereby deepening our understanding of human uterine physiology and pharmacology. Moreover, by employing a human myometrial cell line that expresses TAS2Rs and the corresponding downstream signaling components present in fresh human uteri, we were able to uncover the underlying Ca2+ signal by which the TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline induces relaxation of uterine contractions elicited by oxytocin and various inflammatory mediators. It is crucial to investigate TAS2R5 in human tissues, given this receptor is absent in other mammals (Grau-Bove et al., 2022). This unique expression does not rule out the potential use of animal models in future research. Tissue and cell-specific knock-in techniques could be applied to introduce this receptor into animals, enabling in vivo studies of its reproductive role.

Yet, our study has certain limitations. We focused on myometrial samples from term gravidas. Although we anticipate that phenanthroline can induce relaxation in preterm uteri, its efficacy or potency could vary if the expression of TAS2R5 and its downstream signaling components is reduced or altered. Moreover, our conclusion concerning TAS2R5’s involvement in phenanthroline-induced responses in myometrial cells is based on findings that phenanthroline activates only this receptor within the TAS2R family (Meyerhof et al., 2010). To solidify our conclusion, it would be beneficial to replicate our results in myometrial cells with TAS2R5 knocked out using advanced techniques like CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Lastly, although hTERT-HM cells enable us to identify Ca2+ signaling as a common mechanism for phenanthroline's broad-spectrum relaxation, this cell line lacks functional serotonin receptors or their downstream signaling components. Future studies should explore and validate Ca2+ hypothesis using freshly dissociated uterine smooth muscle cells from both term and preterm uteri.

6. Conclusion

In summary, the selective TAS2R5 agonist phenanthroline effectively inhibits contractions of term uterine strips in response to inflammatory contractile mediators and the contractile hormone oxytocin. Furthermore, this agonist is capable of suppressing the Ca2+ increase elicited by these bioactive contractile substances. This suggests that TAS2R agonists may operate through a common mechanism of interfering with the Ca2+ signaling pathway to produce uterine relaxation. Considering the critical role of various contractile bioactive substances in both parturition and preterm labor, a comprehensive understanding of TAS2R5 function and its agonists could significantly contribute to the development of innovative and effective broad-spectrum uterine relaxants aimed at preventing preterm birth.

Acknowledgments

hTERT-HM cells were provided by Dr. Jenifer Condon in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Wayne State University. Hannah Brewster participated in patient consent and coordinated uterine sample collections and transfer. Mary Beauregard and Linda Benson provided administrative help for the study.

Funding

The study by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIHR01HD095539).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

MQ performed the in vitro uterine contraction experiments and data analysis. PL conducted the in vitro calcium experiments and data analysis. LML supervised data analysis and edited the manuscript. TAMS conducted cesarean deliveries, collected uterine tissue, and edited the manuscript. ED performed cesarean deliveries, collected uterine tissue, edited the manuscript, and provided supervision. RZ was responsible for the conceptualization, provided supervision, and participated in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript, as well as providing resources. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with the content of this paper.

References

- Aguilar HN, Mitchell BF, 2010. Physiological pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating uterine contractility. Hum Reprod Update 16, 725–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arman BM, Binder NK, de Alwis N, Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Hannan NJ, 2023. Repurposing existing drugs as a therapeutic approach for the prevention of preterm birth. Reproduction 165, R9–R23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avau B, Depoortere I, 2016. The bitter truth about bitter taste receptors: beyond sensing bitter in the oral cavity. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 216, 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M, Lang T, 2022. Extra-Oral Taste Receptors-Function, Disease, and Perspectives. Front Nutr 9, 881177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M, Meyerhof W, 2009. Mammalian bitter taste perception. Results Probl Cell Differ 47, 203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller AB, Kinney M, Lawn J, Born Too Soon Preterm Birth Action, G., 2013. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reproductive health 10 Suppl 1, S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloxham CJ, Foster SR, Thomas WG, 2020. A Bitter Taste in Your Heart. Front Physiol 11, 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney EA, Johnson MR, 2019. The role of maternal T cell and macrophage activation in preterm birth: Cause or consequence? Placenta 79, 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuiller-Fouche M, Moriniere C, Dallot E, Oger S, Rebourcet R, Cabrol D, Leroy MJ, 2005. Regulation of the endothelin/endothelin receptor system by interleukin-1beta in human myometrial cells. Endocrinology 146, 4878–4886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulletti C, de Ziegler D, 2005. Uterine contractility and embryo implantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 17, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulletti C, de Ziegler D, Polli V, Diotallevi L, Del Ferro E, Flamigni C, 2000. Uterine contractility during the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod 15 Suppl 1, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bytautiene E, Vedernikov YP, Saade GR, Romero R, Garfield RE, 2008. IgE-independent mast cell activation augments contractility of nonpregnant and pregnant guinea pig myometrium. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 147, 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, Lee RJ, Cohen NA, 2016. Taste Receptors in Upper Airway Immunity. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology 79, 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ, 2000. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev 21, 514–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, Guo W, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ, 2000. T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100, 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, Landoulsi S, Jampathong N, Kongwattanakul K, Laopaiboon M, Lewis C, Rattanakanokchai S, Teng DN, Thinkhamrop J, Watananirun K, Zhang J, Zhou W, Gulmezoglu AM, 2019. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 7, e37–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibbar R, Miller FD, Mitchell BF, 1993. Synthesis of oxytocin in amnion, chorion, and decidua may influence the timing of human parturition. J Clin Invest 91, 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coler BS, Shynlova O, Boros-Rausch A, Lye S, McCartney S, Leimert KB, Xu W, Chemtob S, Olson D, Li M, Huebner E, Curtin A, Kachikis A, Savitsky L, Paul JW, Smith R, Adams Waldorf KM, 2021. Landscape of Preterm Birth Therapeutics and a Path Forward. J Clin Med 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon J, Yin S, Mayhew B, Word RA, Wright WE, Shay JW, Rainey WE, 2002. Telomerase immortalization of human myometrial cells. Biol Reprod 67, 506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeaux Y, Missfelder-Lobos H, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GC, 2008. Stimulation of contractions in human myometrium by serotonin is unmasked by smooth muscle relaxants. Reprod Sci 15, 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeaux Y, Pasupathy D, Bacon J, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GC, 2009. Characterization of serotonin receptors in pregnant human myometrium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328, 682–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande DA, Wang WC, McIlmoyle EL, Robinett KS, Schillinger RM, An SS, Sham JS, Liggett SB, 2010. Bitter taste receptors on airway smooth muscle bronchodilate by localized calcium signaling and reverse obstruction. Nat Med 16, 1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo GC, Tosto V, Giardina I, 2018. The biological basis and prevention of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 52, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr J, Meyer D, Widmayer P, Borth HC, Ackermann F, Wilhelm B, Gudermann T, Boekhoff I, 2007. Expression of the G-protein alpha-subunit gustducin in mammalian spermatozoa. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 193, 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DP, Hutchinson JA, Farrar D, O'Donovan PJ, Woodward DF, Marshall KM, 2008. Loss of prostaglandin F2alpha, but not thromboxane, responsiveness in pregnant human myometrium during labour. J Endocrinol 197, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick JM, Hollyfield JG, Strittmatter WJ, 1984. Inhibitors of metalloendoprotease activity prevent K+-stimulated neurotransmitter release from the retina of Xenopus laevis. J Neurosci 4, 3112–3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR, Fuchs F, Husslein P, Soloff MS, Fernstrom MJ, 1982. Oxytocin receptors and human parturition: a dual role for oxytocin in the initiation of labor. Science 215, 1396–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RE, Irani AM, Schwartz LB, Bytautiene E, Romero R, 2006. Structural and functional comparison of mast cells in the pregnant versus nonpregnant human uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman-Sachs A, Dambaeva S, Salazar Garcia MD, Hussein Y, Kwak-Kim J, Beaman K, 2018. Inflammation induced preterm labor and birth. J Reprod Immunol 129, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno-Molina B, Muller I, Kropf P, Sykes L, 2022. The Role of Neutrophils in Pregnancy, Term and Preterm Labour. Life (Basel) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Governini L, Semplici B, Pavone V, Crifasi L, Marrocco C, De Leo V, Arlt E, Gudermann T, Boekhoff I, Luddi A, Piomboni P, 2020. Expression of Taste Receptor 2 Subtypes in Human Testis and Sperm. J Clin Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato MQ, Massapust Pde A, Rozental S, Alviano CS, dos Santos AL, Kneipp LF, 2015. 1,10-phenanthroline inhibits the metallopeptidase secreted by Phialophora verrucosa and modulates its growth, morphology and differentiation. Mycopathologia 179, 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Bove C, Grau-Bove X, Terra X, Garcia-Vallve S, Rodriguez-Gallego E, Beltran-Debon R, Blay MT, Ardevol A, Pinent M, 2022. Functional and genomic comparative study of the bitter taste receptor family TAS2R: Insight into the role of human TAS2R5. FASEB J 36, e22175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley M, Sayres L, Reiff ES, Wood A, Grotegut CA, Kuller JA, 2019. Tocolysis: A Review of the Literature. Obstetrical & gynecological survey 74, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon CP, Deng D, Breslin PAS, 2021. Bitter Taste Receptors (T2Rs) are Sentinels that Coordinate Metabolic and Immunological Defense Responses. Curr Opin Physiol 20, 70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heluy V, Germain G, Fournier T, Ferre F, Breuiller-Fouche M, 1995. Endothelin ETA receptors mediate human uterine smooth muscle contraction. Eur J Pharmacol 285, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst JJ, Teixeira FJ, Zakar T, Olson DM, 1995. Prostaglandin endoperoxide-H synthase-1 and -2 messenger ribonucleic acid levels in human amnion with spontaneous labor onset. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80, 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keelan JA, Coleman M, Mitchell MD, 1997. The molecular mechanisms of term and preterm labor: recent progress and clinical implications. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology 40, 460–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Bennett PR, Terzidou V, 2017. Advances in the role of oxytocin receptors in human parturition. Mol Cell Endocrinol 449, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JC, Hsu WH, Evans LE, 1990. The effects of xylazine and alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonists on bovine uterine contractility in vitro. Theriogenology 33, 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren Z, Pfeifer Y, Sulman FG, 1965. Serotonin Content of Human Placenta and Fetus during Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 93, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre NM, Krumm E, Cobb WJ, 2021. Labor Dystocia in Nulliparous Women. Am Fam Physician 103, 90–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimert KB, Xu W, Princ MM, Chemtob S, Olson DM, 2021. Inflammatory Amplification: A Central Tenet of Uterine Transition for Labor. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 11, 660983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyendecker G, Wildt L, 2011. A new concept of endometriosis and adenomyosis: tissue injury and repair (TIAR). Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 5, 125–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Lu S, Xu R, Atzberger A, Gunther S, Wettschureck N, Offermanns S, 2017. Members of Bitter Taste Receptor Cluster Tas2r143/Tas2r135/Tas2r126 Are Expressed in the Epithelium of Murine Airways and Other Non-gustatory Tissues. Front Physiol 8, 849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Gong T, Shi F, Xu H, Chen X, 2022. Taste receptors affect male reproduction by influencing steroid synthesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 10, 956981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Zhang CH, Lifshitz LM, ZhuGe R, 2017. Extraoral bitter taste receptors in health and disease. J Gen Physiol 149, 181–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luddi A, Governini L, Wilmskotter D, Gudermann T, Boekhoff I, Piomboni P, 2019. Taste Receptors: New Players in Sperm Biology. Int J Mol Sci 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor B, Allaire C, Bedaiwy MA, Yong PJ, Bougie O, 2023. Disease Burden of Dysmenorrhea: Impact on Life Course Potential. Int J Womens Health 15, 499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Bonney EA, Condon J, Mesiano S, Taylor RN, 2016. Novel concepts on pregnancy clocks and alarms: redundancy and synergy in human parturition. Hum Reprod Update 22, 535–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhof W, Batram C, Kuhn C, Brockhoff A, Chudoba E, Bufe B, Appendino G, Behrens M, 2010. The Molecular Receptive Ranges of Human TAS2R Bitter Taste Receptors. Chemical Senses 35, 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Perez VM, Ortiz MI, Carino-Cortes R, Fernandez-Martinez E, Rocha-Zavaleta L, Bautista-Avila M, 2019. Preterm Birth, Inflammation and Infection: New Alternative Strategies for their Prevention. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 20, 354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olund A, Kindahl H, Oliw E, Lindgren JA, Larsson B, 1980. Prostaglandins and thromboxanes in amniotic fluid during rivanol-induced abortion and labour. Prostaglandins 19, 791–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada K, Tsunoda H, Miyauchi T, Sugishita Y, Kubo T, Goto K, 1997. Pregnancy increases ET-1-induced contraction and changes receptor subtypes in uterine smooth muscle in humans. Am J Physiol 272, R541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottlecz A, Walker S, Conrad M, Starcher B, 1991. Neutral metalloendopeptidase associated with the smooth muscle cells of pregnant rat uterus. J Cell Biochem 45, 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris HN, Romero R, Vaswani K, Reed S, Gomez-Lopez N, Tarca AL, Gudicha DW, Erez O, Maymon E, Mitchell MD, 2021. Preterm labor is characterized by a high abundance of amniotic fluid prostaglandins in patients with intra-amniotic infection or sterile intra-amniotic inflammation. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 34, 4009–4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Lu P, Bellve K, Lifshitz LM, ZhuGe R, 2021. Mode Switch of Ca(2 +) Oscillation-Mediated Uterine Peristalsis and Associated Embryo Implantation Impairments in Mouse Adenomyosis. Front Physiol 12, 744745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer RB, Booth D, Bhavsar AA, Walter GH, Terry LI, 2012. Mathematical model of cycad cones' thermogenic temperature responses: inverse calorimetry to estimate metabolic heating rates. J Theor Biol 315, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Baumann P, Gonzalez R, Gomez R, Rittenhouse L, Behnke E, Mitchell MD, 1994. Amniotic fluid prostanoid concentrations increase early during the course of spontaneous labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171, 1613–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ, 2014. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Emamian M, Wan M, Quintero R, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD, 1987. Prostaglandin concentrations in amniotic fluid of women with intra-amniotic infection and preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 157, 1461–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H, Yogev Y, 2023. Assessment of uterine contractions in labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 228, S1209–S1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn BM, 2000. Relationship of ion channel activity to control of myometrial calcium. J Soc Gynecol Investig 7, 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriefer JA, Molineaux CJ, 1993. Modulatory effect of endopeptidase inhibitors on bradykinin-induced contraction of rat uterus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 266, 700–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semplici B, Luongo FP, Passaponti S, Landi C, Governini L, Morgante G, De Leo V, Piomboni P, Luddi A, 2021. Bitter Taste Receptors Expression in Human Granulosa and Cumulus Cells: New Perspectives in Female Fertility. Cells 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, 2007. Parturition. N Engl J Med 356, 271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmon M, Rossi S, Lim D, Pollastro F, Palattella G, Ruffinatti FA, Marotta P, Boldorini R, Genazzani AA, Fresu LG, 2019. Absinthin, an agonist of the bitter taste receptor hTAS2R46, uncovers an ER-to-mitochondria Ca(2+)-shuttling event. J Biol Chem 294, 12472–12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Sanderson MJ, 2014. Bitter tasting compounds dilate airways by inhibiting airway smooth muscle calcium oscillations and calcium sensitivity. Br J Pharmacol 171, 646–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tersigni C, Vatish M, D'Ippolito S, Scambia G, Di Simone N, 2020. Abnormal uterine inflammation in obstetric syndromes: molecular insights into the role of chemokine decoy receptor D6 and inflammasome NLRP3. Mol Hum Reprod 26, 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuzim K, Korolczuk A, 2021. An update on extra-oral bitter taste receptors. J Transl Med 19, 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvnas-Moberg K, Ekstrom-Bergstrom A, Berg M, Buckley S, Pajalic Z, Hadjigeorgiou E, Kotlowska A, Lengler L, Kielbratowska B, Leon-Larios F, Magistretti CM, Downe S, Lindstrom B, Dencker A, 2019. Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during physiological childbirth - a systematic review with implications for uterine contractions and central actions of oxytocin. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal MS Jr., Lintao RCV, Severino MEL, Tantengco OAG, Menon R, 2022. Spontaneous preterm birth: Involvement of multiple feto-maternal tissues and organ systems, differing mechanisms, and pathways. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13, 1015622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yen H, Chen CH, Soni R, Jasani N, Sylvestre G, Reznik SE, 2008. The endothelin-converting enzyme-1/endothelin-1 pathway plays a critical role in inflammation-associated premature delivery in a mouse model. Am J Pathol 173, 1077–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Hodgetts-Morton VA, Marson EJ, Markland AD, Larkai E, Papadopoulou A, Coomarasamy A, Tobias A, Chou D, Oladapo OT, Price MJ, Morris K, Gallos ID, 2022. Tocolytics for delaying preterm birth: a network meta-analysis (0924). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8, CD014978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfle U, Elsholz FA, Kersten A, Haarhaus B, Schumacher U, Schempp CM, 2016. Expression and Functional Activity of the Human Bitter Taste Receptor TAS2R38 in Human Placental Tissues and JEG-3 Cells. Molecules 21, 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GT, Gannon KS, Margolskee RF, 1996. Transduction of bitter and sweet taste by gustducin. Nature 381, 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S, Arrowsmith S, 2021. Uterine Excitability and Ion Channels and Their Changes with Gestation and Hormonal Environment. Annu Rev Physiol 83, 331–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S, Arrowsmith S, Sharp A, 2023. Pharmacological Interventions in Labor and Delivery. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 63, 471–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallampalli C, Garfield RE, 1994. Uterine contractile responses to endothelin-1 and endothelin receptors are elevated during labor. Biol Reprod 51, 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Zhuge R, Hsu WH, 1995. Lysine vasopressin-induced increases in porcine myometrial contractility and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations of myometrial cells: involvement of oxytocin receptors. Biol Reprod 52, 584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C-H, Lifshitz LM, Uy KF, Ikebe M, Fogarty KE, R. Z, 2013. The Cellular and Molecular Basis of Bitter Tastant-induced Bronchodilation. PLOS Biology 11(3):e1001501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wei H, 2021. Role of Decidual Natural Killer Cells in Human Pregnancy and Related Pregnancy Complications. Front Immunol 12, 728291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng K, Lu P, Delpapa E, Bellve K, Deng R, Condon JC, Fogarty K, Lifshitz LM, Simas TAM, Shi F, ZhuGe R, 2017. Bitter taste receptors as targets for tocolytics in preterm labor therapy. FASEB J 31, 4037–4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]