Abstract

Background and aims:

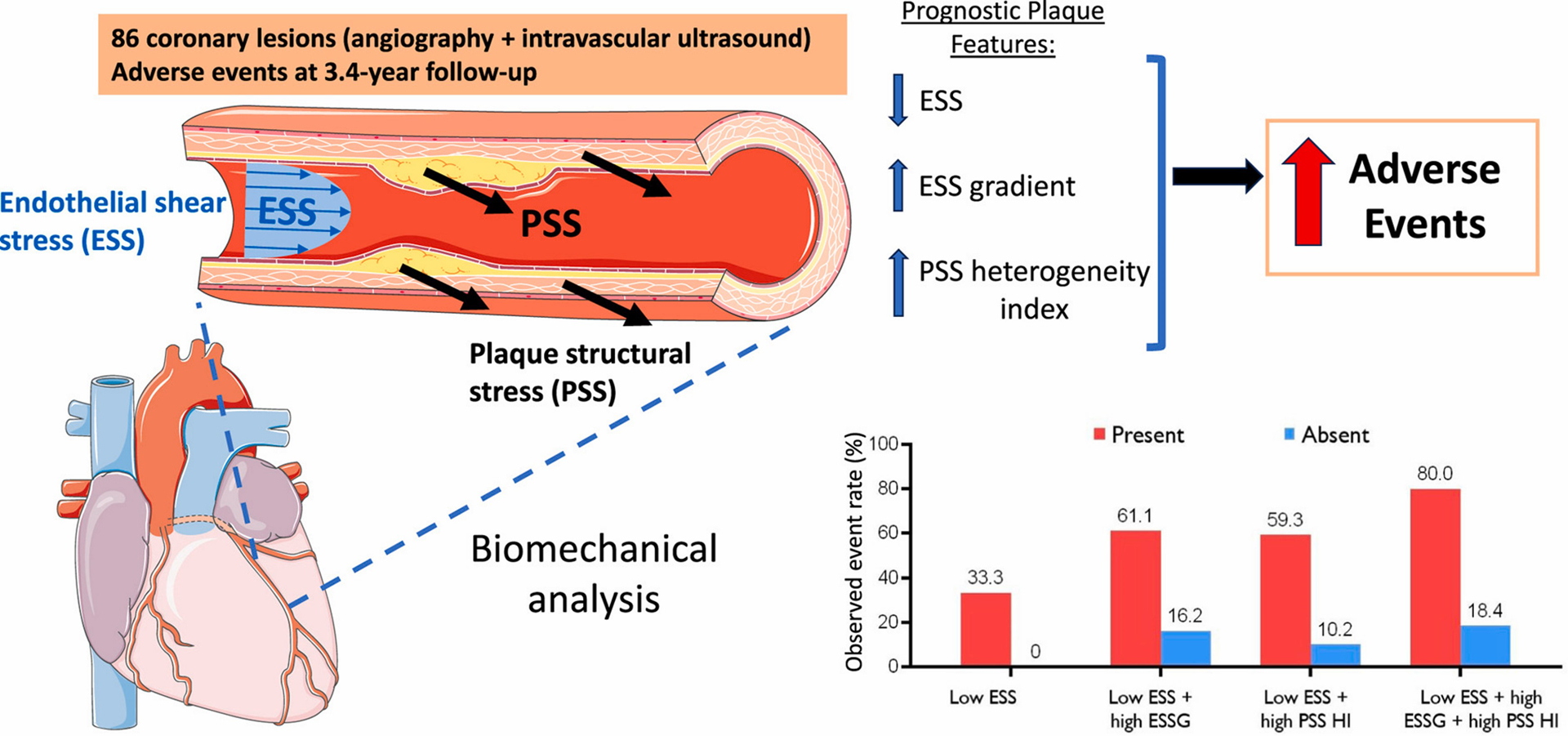

Anatomical imaging alone of coronary atherosclerotic plaques is insufficient to identify risk of future adverse events and guide management of non-culprit lesions. Low endothelial shear stress (ESS) and high plaque structural stress (PSS) are associated with events, but individually their predictive value is insufficient for risk prediction. We determined whether combining multiple complementary, biomechanical and anatomical plaque characteristics improves outcome prediction sufficiently to inform clinical decision-making.

Methods:

We examined baseline ESS, ESS gradient (ESSG), PSS, and PSS heterogeneity index (HI), and plaque burden in 22 lesions that developed subsequent events and 64 control lesions that remained quiescent from the PROSPECT study.

Results:

86 fibroatheromas were analysed from 67 patients. Lesions with events showed higher PSS HI (0.32 vs. 0.24, p<0.001), lower local ESS (0.56Pa vs. 0.91Pa, p = 0.007), and higher ESSG (3.82 Pa/mm vs. 1.96 Pa/mm, p = 0.007), while high PSS HI (hazard ratio [HR] 3.9, p = 0.006), high ESSG (HR 3.4, p = 0.007) and plaque burden>70 % (HR 2.6, p = 0.02) were independent outcome predictors in multivariate analysis. Combining low ESS, high ESSG, and high PSS HI gave both high positive predictive value (80 %), which increased further combined with plaque burden>70 %, and negative predictive value (81.6 %). Low ESS, high ESSG, and high PSS HI co-localised spatially within 1 mm in lesions with events, and importantly, this cluster was distant from the minimum lumen area site.

Conclusions:

Combining complementary biomechanical and anatomical metrics significantly improves risk-stratification of individual coronary lesions. If confirmed from larger prospective studies, our results may inform targeted revascularisation vs. conservative management strategies.

Keywords: Atherosclerotic plaques, Acute coronary syndrome, Patient outcomes, Risk stratification, Intravascular ultrasound

1. Introduction

Despite advances in medical and interventional therapies, future major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) such as cardiovascular death or re-infarction following intervention in acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are 8.1–15.8 % and 10.0–14.5 %, respectively, up to 5 years [1,2]. Many events are due to destabilisation of non-culprit lesions (NCLs), but the prognostic value of anatomy-based plaque risk assessment alone is disappointing. For example, combining high-risk anatomical features such as large plaque burden (PB), small minimum lumen area (MLA), thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA), and lipid core burden index predicts only 18.2–23.1 % of NCL MACE over 3.4 years by intravascular ultrasound [3–5], 18.9 % by optical coherence tomography [6], 19.3 % by near-infrared spectroscopy [7], and 4.1 % by coronary computed tomography angiography [8].

Endothelial shear stress (ESS) describes the frictional force of blood acting on arterial wall endothelial cells [9], and low ESS is associated with plaque development, progression, and destabilisation [10,11]. Similarly, high ESS, particularly high ESS gradient (ESSG) due to abrupt changes in plaque-lumen interface topography, can also promote plaque disruption [12]. High plaque structural stress (PSS), which is determined by material properties and spatial relationships of individual plaque components [9,13], and its longitudinal heterogeneity (PSS–HI) also promote plaque progression and vulnerability [14–17]. However, while single biomechanical plaque metrics enhance prognostication of individual coronary plaques, their predictive accuracy is not sufficient to guide clinical management.

We examined a unique and comprehensive combination of complementary biomechanical and anatomical plaque metrics to determine their prognostic synergy. Specific combinations of local ESS, ESSG, PSS, and PSS-HI with high-risk anatomical plaque features significantly improve NCL risk-stratification, potentially informing clinical decisions such as targeted revascularisation vs. conservative management strategies for individual lesions.

2. Patients and methods

The Providing Regional Observations to Study Predictors of Events in the Coronary Tree (PROSPECT; NCT00180466) trial is a prospective natural history study of coronary atherosclerosis [3]. 697 ACS patients underwent successful culprit lesion(s) intervention, followed by baseline angiography and 3-vessel virtual histology intravascular ultrasound (VH-IVUS) [3]. Vessel analysis was performed offline by an independent core laboratory, and patients followed for a median of 3.4 years. MACE comprised the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction or rehospitalization due to progressive or unstable angina. A clinical events committee adjudicated each suspected MACE with no knowledge of other patient data. Events were attributed to culprit lesions or NCLs based on follow-up angiography. The study protocol conforms to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines, was approved by each institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.1. VH-IVUS image acquisition and analysis

VH-IVUS image acquisition, analysis and plaque classification were as described previously [3] (Supplementary Methods). In brief, plaques were defined as ≥3 consecutive frames with PB ≥ 40 %. As thin and thick cap fibroatheromas (TFCA and ThCFA) caused 88 % of all MACE, we focused on these lesions.

2.2. Biomechanical analysis

2.2.1. Local endothelial shear stress computation

MACE and randomly-selected non-MACE NCLs were studied at ~1:3 ratio. Local plaque ESS was assessed using validated vascular profiling methods from coronary angiography and IVUS to reconstruct coronary artery lumens and perform computational fluid dynamics (CFD) calculations (Supplementary Methods) [10]. Coronary angiographic and IVUS centrelines were merged for 3D coronary artery reconstruction [11], and entire reconstructed arteries divided into serial 3-mm segments to calculate local ESS, ESSG, plaque area, external elastic membrane (EEM) area, lumen area, PB, and arterial remodelling index. The lowest and highest local ESS site was determined along the whole lesion in moving 90◦ arcs around the vessel circumference and related spatially to the MLA. Since developed flow is established after an entrance length of 3 mm, any lesion with a length less than 9 mm is considered too short for any meaningful ESS evaluation [11]. We excluded bifurcations and side branches from our CFD analyses, as do most investigators, because of technical limitations of their segmentation, quantification of blood flow, and 3D reconstruction necessary for CFD [18–20]. Our methods have been previously validated and have excellent reproducibility [21].

2.2.2. Local plaque structural stress computation

Vessel geometry and plaque composition were extracted from VH-IVUS data and imported into proprietary software (MATLAB R2022b, MathWorks, Inc, Massachusetts), allowing construction of 2D solid models. Frames containing side branches or immediately adjacent to bifurcations were excluded as they violated the plane strain assumption for 2D solids. PSS was calculated using dynamic finite element analysis (FEA) as described previously (Supplementary Methods) [13,22], with PSS heterogeneity index (HI) calculated as standard deviation/mean PSS across the whole plaque. Maximum peri-luminal region principal stress was used to indicate critical mechanical conditions.

Biomechanical analysis focused on lesion sites, but we also calculated ESSmin, ESSG, and PSS HI10mm at regions with PB<40 % adjacent to significant plaque sites. MACE during follow-up were analysed against baseline ESS, PSS and PROSPECT anatomical characteristics (PB, MLA, and morphology (TCFA and ThCFA)) [3]. Low ESS was defined as <1.3 Pa, a well-accepted definition for low/physiological ESS associated with NCL-MACE [11].

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Numerical variables were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests and categorical variables using chi-square tests. Outliers were removed using the median absolute deviation method with threshold 3.5. As each plaque had multiple VH-IVUS frames, linear mixed-effects (LME) models were used to account for hierarchical data structure and clustering in individual patients with results presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Model diagnostics were performed by inspecting residual and Q-Q plots to test model assumptions. Association between continuous variables was assessed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient and linear regression. Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed for pre-defined biomechanical variables to identify the best cut-off that predicted MACE, which was subsequently used to categorize low and high ESS, ESSG, and PSS heterogeneity. Time-to-event curves are presented as Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative hazard and compared using the log-rank method. Individual ESS and PSS predictors of MACE were identified using Cox regression analysis and statistically significant variables entered in a multivariable model to identify independent predictors. Proportional hazards assumption was tested by checking interaction between the time measure and covariates. Chi-square test was used for differences in frequency distribution of biomechanical metrics. Statistical significance was indicated by two-tailed p<0.05. Analyses were performed in SPSS (version 27, IBM, New York) and R (version 4.2.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline patient and anatomical lesion characteristics

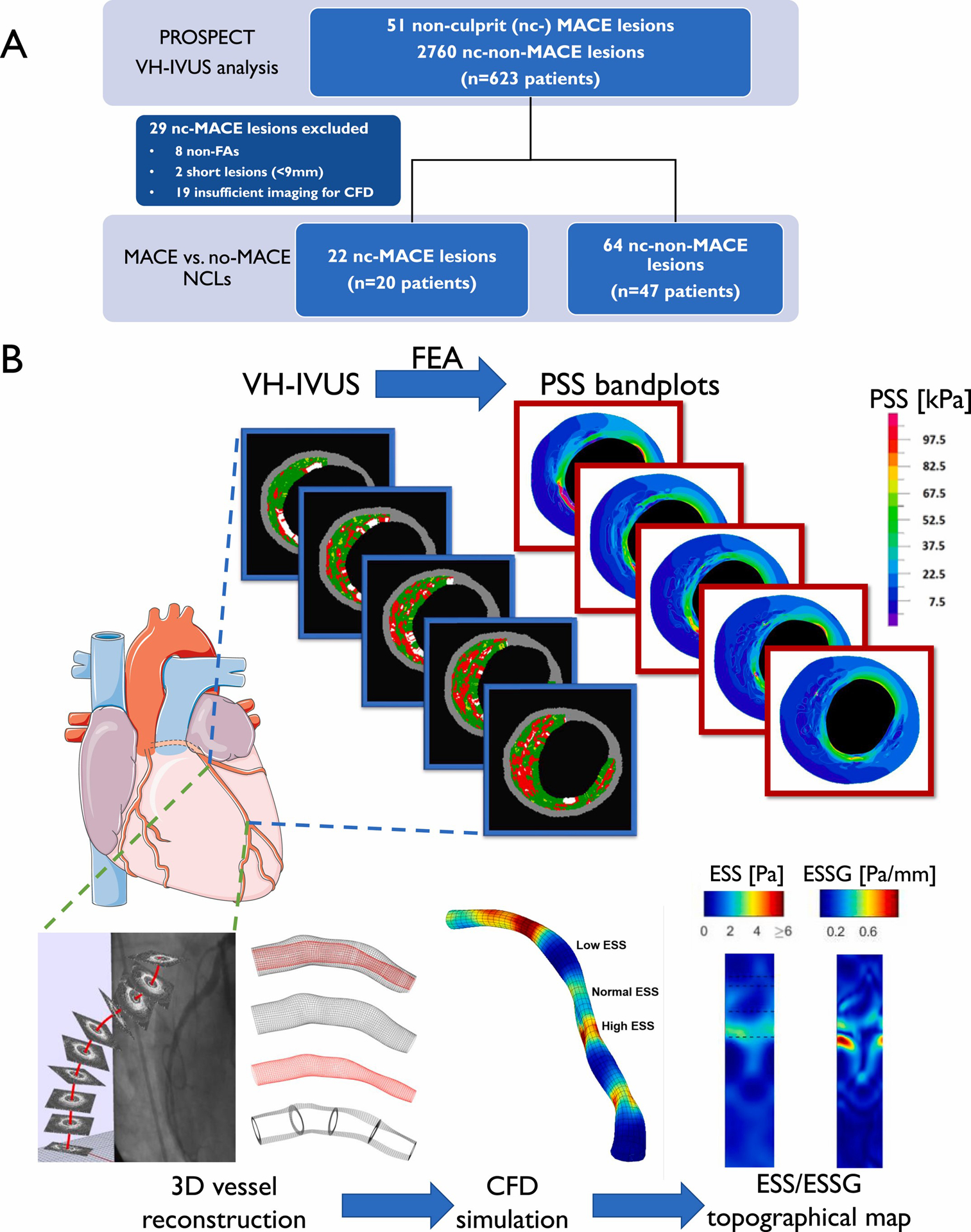

Fifty-one NCLs caused subsequent MACE in PROSPECT, including 8 non-fibroatheromas, which were excluded. Two lesions were too short (<9 mm) for any meaningful ESS or PSS heterogeneity evaluation. ESS vascular profiling CFD analyses require specific biplane coronary angiograms to reconstruct coronary 3D structure and to allow the merging of artery centreline with IVUS imaging. There were 19 (37 %) lesions with insufficient imaging to perform CFD [11] and were excluded (Fig. 1A). The final dataset comprised 86 NCLs (22 MACE plaques from 20 patients, 2 MIs, 4 unstable angina, 14 rehospitalization; 64 non-MACE plaques from 47 patients), and patient demographics were well matched with the full PROSPECT cohort, apart from more current smokers (63.6 % vs. 47.7 %, p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 1). Patients had a median age of 57.5 years, 83.6 % were male and patient demographics were well matched between MACE (n = 20) and non-MACE (n = 47) groups (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Study design workflow.

(A) Lesion selection, (B) plaque structural stress (PSS) and endothelial shear stress (ESS) calculation on co-registered coronary lesions. CFD = computational fluid dynamics; ESSG = ESS gradient; FA = fibroatheroma; FEA = finite element analysis; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; nc = non-culprit; NCL = nc lesion; VH-IVUS = virtual histology intravascular ultrasound.

Lesions were distributed across all main coronary arteries, with 51.2 % in the proximal vessel (Supplementary Table 3). Overall, 64 % were TCFAs, with similar TCFA and ThCFA proportions in MACE and non-MACE groups. MACE plaques had significantly smaller MLA (3.83 vs. 5.05 mm2, p = 0.002), larger PB at MLA (70.0 % vs. 59.4 %, p<0.001), and were longer (29.0 vs. 19.8 mm, p = 0.001). By VH-IVUS, MACE plaques had significantly larger overall PB (54.1 vs. 50.9 %, p = 0.02); otherwise, EEM, lumen or plaque areas or plaque composition were similar (Supplementary Table 3).

3.2. Association of baseline ESS, ESS gradient and PSS heterogeneity with future MACE

Baseline ESS and PSS parameters were calculated on 55 TCFA and 31 ThCFA co-registered lesions (Fig. 1B). MACE plaques had lower baseline local minimum ESS (ESSmin, 0.56 vs. 0.91Pa, p = 0.007), higher local maximum ESS (ESSmax, 5.81 vs. 4.37Pa, p = 0.011) and higher ESS gradient (ESSG, 3.82 vs. 1.96 Pa/mm, p = 0.007) compared to non-MACE plaques (Supplementary Table 4). MACE plaques had lower maximum PSS (PSSmax, 115.5 vs. 124.4 kPa, p = 0.038) in this unmatched cohort consistent with their higher PB and lower MLA (according to Laplace’s law), but higher PSS heterogeneity index (PSS HI, 0.321 vs. 0.241, p<0.001 (Supplementary Table 4).

ROC analysis was performed to identify ESS and PSS parameters thresholds that best predicted future MACE, and used to classify each parameter into ‘low’ and ‘high’ indices. Cumulative MACE probabilities were higher in plaques with lower local ESSmin (≤1.3Pa, p = 0.005), higher ESS gradient (ESSG, ≥4.0 Pa/mm, p< 0.001), or higher PSS HI (≥0.29, p< 0.001)(Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the ability to identify MACE lesions varied across different combinations of biomechanical parameters. For example, all MACE plaques had a baseline ESSmin <1.3 kPa, but so did many non-MACE plaques (Supplementary Fig. 2A). High PSS HI combined with low ESSmin best predicted MACE vs. non-MACE lesions (72.7 % vs. 17.2 %, p<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2A), compared with 50 % vs. 10.9 % (p<0.001) for low ESSmin/high ESSG, and 36.4 % vs. 3.1 % for high ESSG/high PSS HI (p<0.001) (Supplementary Figs. 2B–C). Similarly, combined high ESSG/high PSS HI identified fewer MACE vs. non-MACE lesions if only lesions with a low baseline ESS (<1.3Pa) were studied (36.4 % vs. 4.5 %, p = 0.002) (Supplementary Fig. 2D).

Of all biomechanical and anatomical parameters, only high ESSG, high PSS HI, smaller MLA and PB>70 % were associated with MACE on univariate analysis (Table 1). High ESSG (hazard ratio [HR] 3.36, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.40–8.07, p = 0.007), high PSS HI (HR 3.91, 95 % CI 1.47–10.4, p = 0.006), and large PB (HR 2.60, 95 % CI 1.07–6.31, p = 0.035) were also independent predictors of MACE in multivariable analyses. Similar results were seen in an age-, sex- and smoking-adjusted multivariate model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cox proportional hazard regression: Factors associated with MACE.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Adjusted Modela | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95 % CI) | p value | HR (95 % CI) | p value | HR (95 % CI) | p value | |

| Low ESSmin | 32.5 (0.57–1843) | 0.091 | – | - | - | - |

| High ESSmeanb | 2.27 (0.95–5.42) | 0.065 | – | - | - | - |

| High ESSG | 3.96 (1.71–9.18) | 0.001 | 3.36 (1.40–8.07) | 0.007 | 3.34 (1.39–8.01) | 0.007 |

| High PSS | 0.58 (0.20–1.70) | 0.316 | – | – | – | – |

| High PSS HI | 5.03 (1.96–12.9) | <0.001 | 3.91 (1.47–10.4) | 0.006 | 3.86 (1.45–10.27) | 0.007 |

| MLA≤4 mm2 | 2.89 (1.25–6.70) | 0.013 | – | - | - | - |

| PB ≥ 70 % at MLA | 4.35 (1.88–10.1) | <0.001 | 2.60 (1.07–6.31) | 0.035 | 2.59 (1.07–6.29) | 0.035 |

CI = confidence interval; ESS = endothelial shear stress; ESSG = ESS gradient; HI = heterogeneity index; HR = hazard ratio; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; MLA = minimum lumen area; PB = plaque burden; PSS = plaque structural stress.

Age, sex and smoking status adjusted model.

High ESSmean cut-off = 2.7Pa, determined by Youden index on receiver operating characteristic analysis.

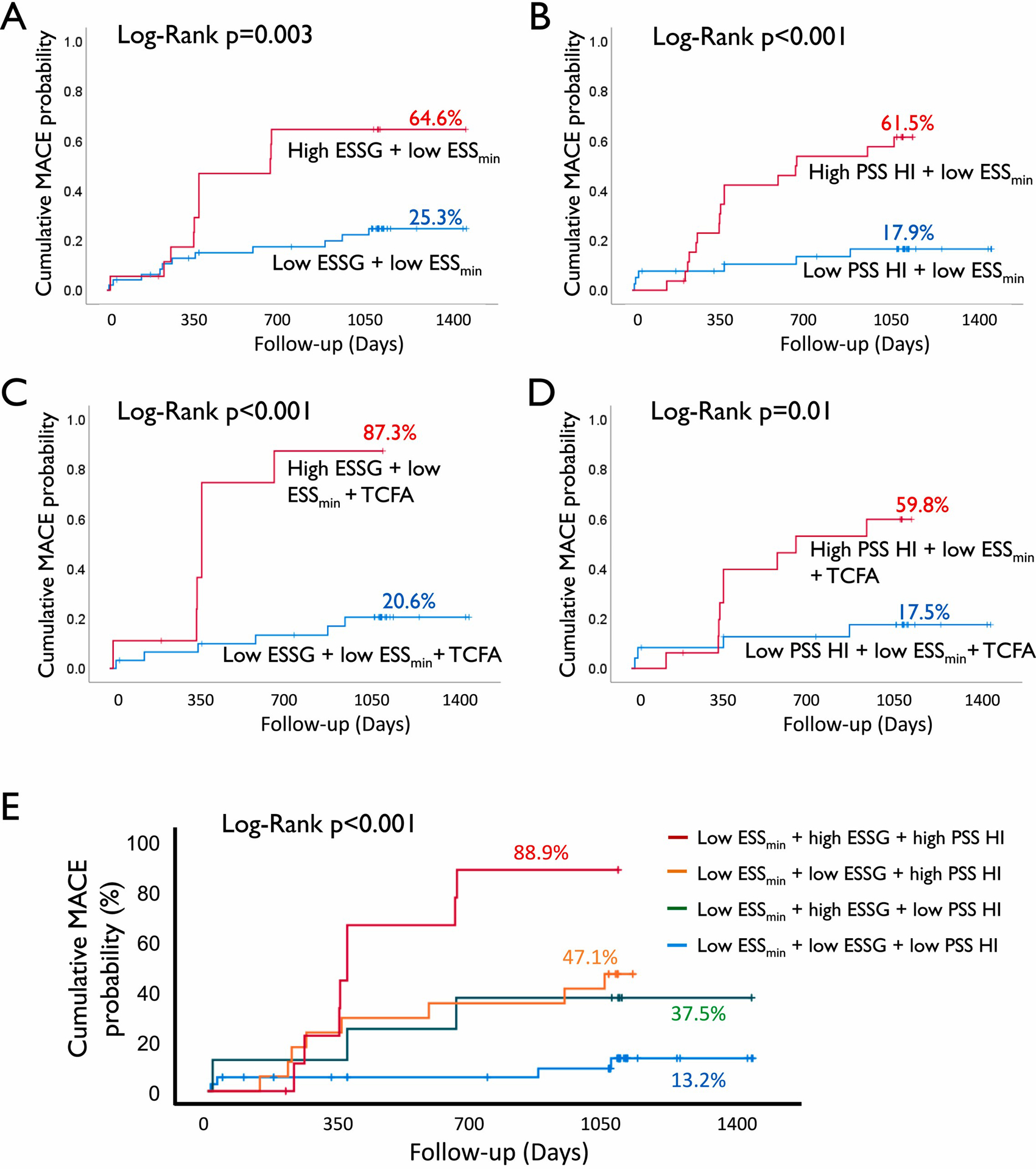

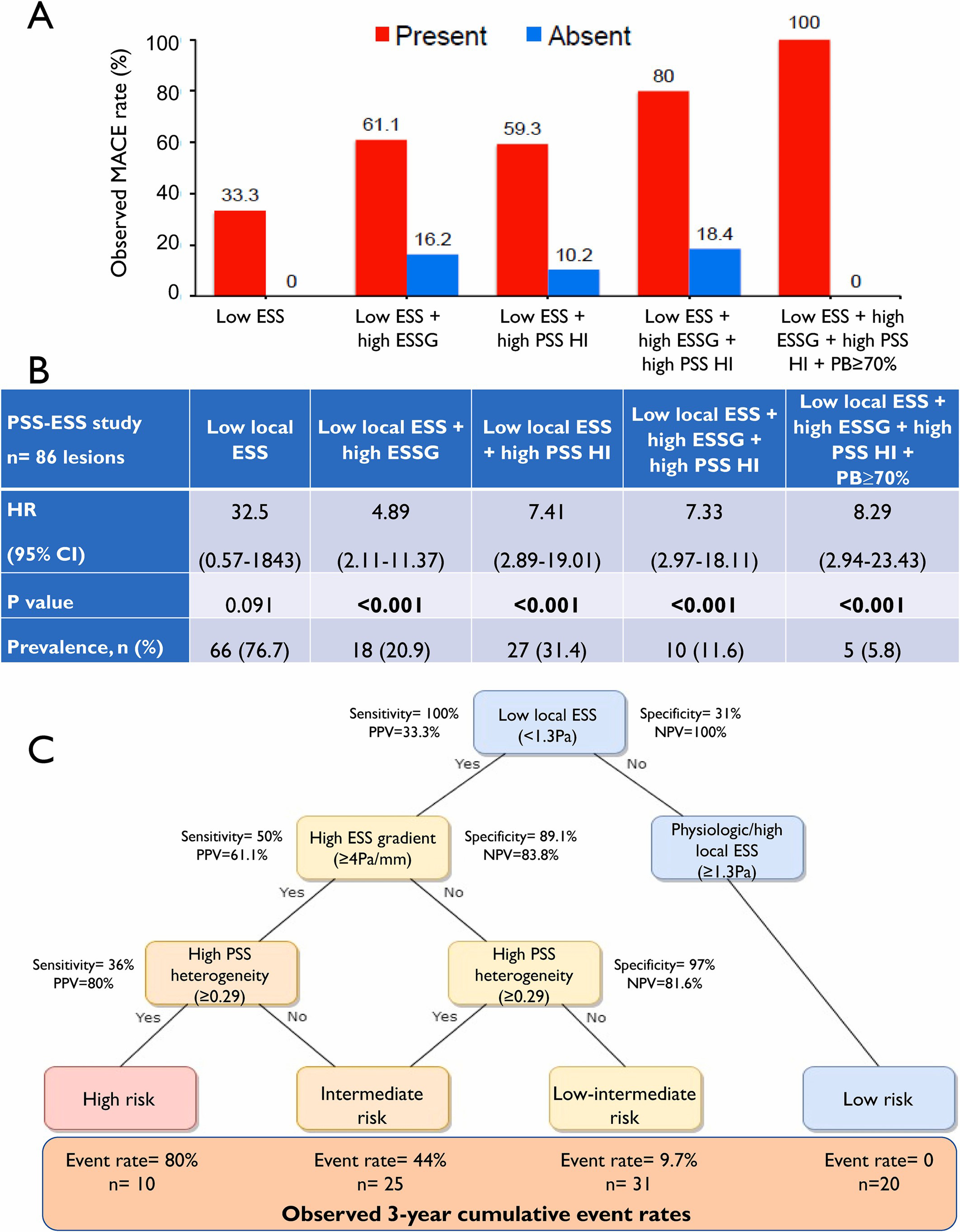

3.3. Incorporating PSS heterogeneity and ESSG improves prediction of MACE

While MACE only occurred in plaques with baseline low ESSmin (<1.3Pa), 77.2 % of non-MACE plaques had focal areas with low ESSmin (Supplementary Fig. 2A). However, combining high ESSG or high PSS HI individually with low ESSmin increased cumulative NCL-MACE probabilities from 33 % to 64.6 % and 61.5 %, respectively, in all NCL fibroatheromas (Fig. 2A–B), and from 32.5 % to 87.3 % and 59.8 %, respectively, in TCFAs (Fig. 2C–D). Combining high ESSG/high PSS HI with low ESSmin increased cumulative MACE probabilities further (Fig. 2E), with observed MACE rates of individual plaques increasing with number of high-risk metrics present. For example, NCL MACE rates (Fig. 3A) and plaque Hazard Ratios (HR) (Fig. 3B) were higher in plaques with a low baseline ESS combined with a high baseline ESSG, a high PSS HI, or both. Indeed, lesions containing these three biomechanical metrics showed 80 % MACE rates, and lesions containing all three biomechanical metrics plus PB ≥ 70 % had 100 % MACE rates (HR 8.29) (Fig. 3A–B). As expected, the prevalence of these progressively higher risk combinations was progressively less frequent.

Fig. 2.

Incorporation of high ESSG and high PSS HI improves risk stratification of low ESS lesions.

Cumulative MACE probability in lesions with low ESS and high or low (A) ESSG, (B) PSS HI, in TCFA lesions with high or low (C) ESSG, (D) PSS HI, or (E) combination of ESS, ESSG and PSS HI. ESS = endothelial shear stress; ESSG = ESS gradient; HI = heterogeneity index; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; PSS = plaque structural stress; TCFA = thin cap fibroatheroma.

Fig. 3.

Combined ESS, ESS gradient (ESSG) and plaque structural stress (PSS) heterogeneity index (HI) improves MACE prediction.

(A) Observed MACE rates in different combinations of biomechanical metrics. (B) Hazard Ratio (HR) and feature prevalence at lesion level. (C) Stepwise decision tree for plaque risk stratification based on predictive values. CI = confidence interval; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value.

3.4. Plaque risk stratification

The progressive increase in MACE rates in plaques with more biomechanical features provides a valuable platform to find the best sequence of metrics to predict MACE in NCLs. We developed a stepwise decision tree based on PPV and NPV to both identify and exclude high-risk plaques. Combining high ESSG and low ESSmin improved PPV to 61.1 % with a NPV of 83.8 % (Fig. 3C). Adding high PSS HI to low ESSmin increased PPV from 33.3 % to 59.3 %, maintaining a high NPV at 89.8 %, but combining PSS HI, ESSG, and ESSmin further improved PPV to 80 %, still maintaining a high NPV at 81.6 % (Fig. 3C). Similarly, different combinations of biomechanical features were associated with lesser or even no risk, with no events with physiologic/high local ESS (≥1.3Pa).

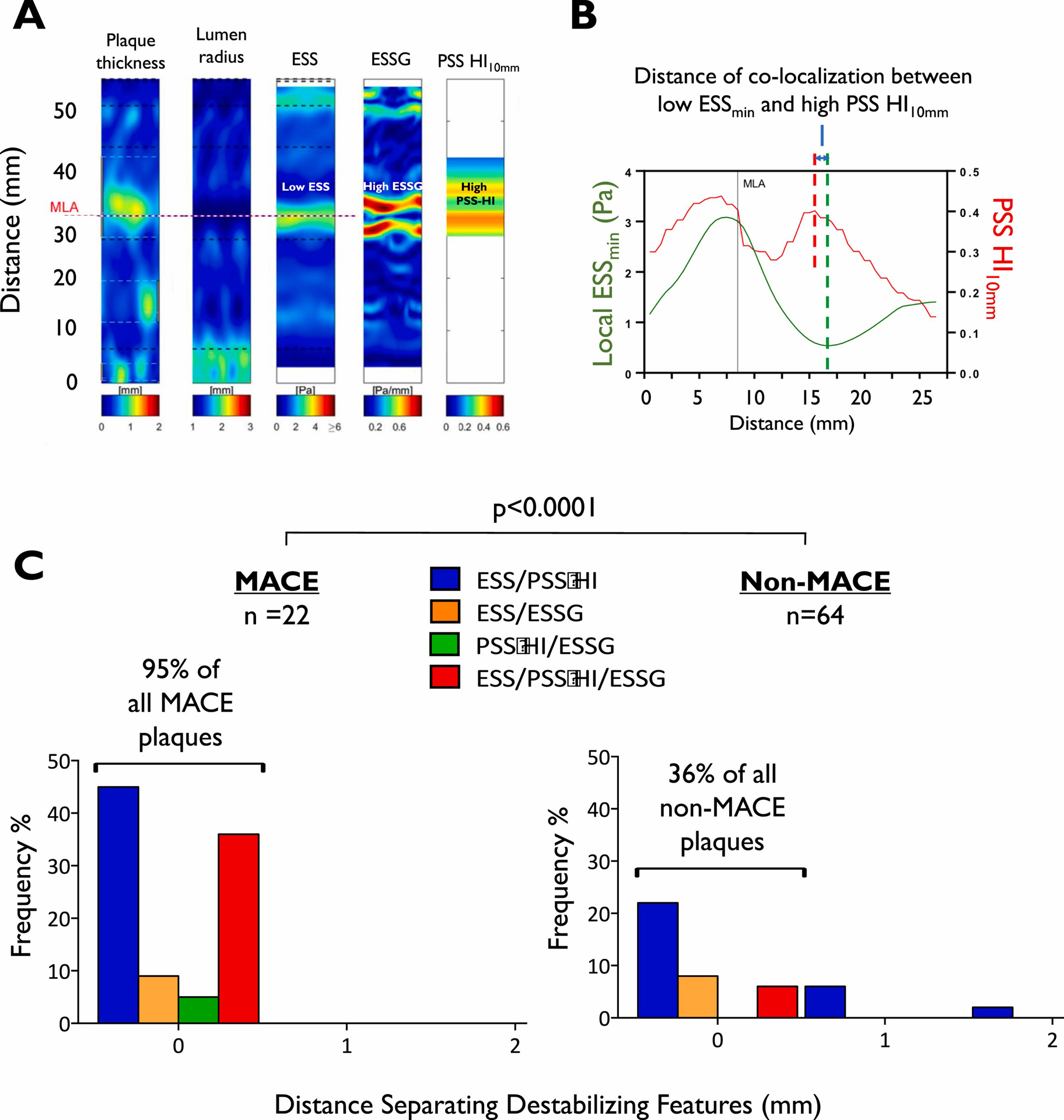

3.5. Spatial relationship of high-risk features in individual plaques and their relationship to the MLA

We further examined whether the 3 prognostic biomechanical metrics were clustered spatially or located distant from each other, and their relationship to the MLA, the site targeted by most percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). Low ESSmin and high ESSG sites were identified in each plaque, together with the highest PSS HI over a 10 mm plaque segment (PSS HI10mm) 5 mm proximal and distal to a reference point moving along each plaque (Fig. 4A–B). 95 % of MACE plaques exhibited two or more higher-risk features (low ESSmin, high ESSG, high PSS HI10mm) clustered within 1 mm of each other, compared with only 36 % of non-MACE plaques (p<0.0001) (Fig. 4C). Importantly, the mean distance between the colocalised high-risk features and the MLA was ≥13 mm in both MACE and non-MACE plaques.

Fig. 4.

MACE lesions exhibit more spatially colocalised biomechanical metrics.

(A) Example of a MACE plaque, showing the plaque thickness, lumen radius, ESS, ESSG and the PSS HI10mm profile. (B) Representative example of co-localization of low ESSmin and high PSS HI10mm in the same MACE plaque, with their spatial relationship indicated by the distance between the red and green dashed lines. (C) Different combinations of biomechanical features (low ESSmin<1.3Pa, high ESSG≥4 Pa/mm, and high PSS HI10mm > 0.29) clustering together in MACE plaques vs. no-MACE plaques. ESS = endothelial shear stress; ESSG = ESS gradient; HI = heterogeneity index; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; MLA = minimal lumen area; PSS = plaque structural stress.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to comprehensively examine the prognostic significance of multiple combinations of known baseline high-risk and mechanistically complementary biomechanical and anatomical metrics in non-culprit coronary plaques. We observed that: (1) each biomechanical parameter (ESSmin, ESSG, PSS HI) alone increased MACE prediction; (2) high ESSG, high PSS HI, and high PB were independent predictors of MACE; (3) combining baseline low ESS, high ESSG and high PSS HI provided the highest prediction (88.9 %) of future MACE, with even higher prediction if combined with high PB; (4) different metrics combinations segregated lesions into high-, intermediate- and low-risk groups that could guide clinical decisions for targeted revascularisation or conservative treatment, and (5) complementary and synergistic high-risk biomechanical features cluster within a plaque, which are typically located distant from the MLA.

Early prognostic studies found that anatomical characteristics, including large PB, small MLA, TCFA morphology, and large lipid core were associated with future MACE [3,7,23]. We similarly found that smaller MLA and PB>70 % were predictors in univariate analysis in our subgroup, and larger PB in multivariate analysis. TCFA morphology was not a significant event predictor, but this may be due to our excluding lower risk lesions (PIT, fibrocalcific and fibrotic plaques) and the generally low event rate of both TCFA and non-TCFA lesions (4.9 % vs. 1.3 %) in PROSPECT. We also found that low ESS was not an independent predictor of MACE, as observed in the PREDICTION study [10], which included lower-risk plaques and patients. Our current study was limited to non-culprit higher-risk fibroatheromas in ACS patients. In contrast to some studies [24,25], high ESS (i.e. high ESSmean, cut-off = 2.7Pa determined by Youden index on ROC analysis) was also not an independent predictor of future MACE. A luminal stenosis creates both high shear stress at the MLA and low shear stress up and down stream to the MLA. The metric of “average” plaque ESS used in those studies may miss highly focal areas of low ESS (<~1.0Pa), located adjacent to high ESS areas (>5Pa), which becomes subsumed by averaging. In contrast, the metric “ESSG” reflects both the combined pathobiology of high ESS and the adjacent low ESS, and thereby provides a powerful independent predictor.

Although previous studies have shown that individual biomechanical metrics (low ESS or high PSS HI) improve MACE prediction when combined with high-risk anatomical variables [10,11,17], their predictive accuracy was still low. Our current results show that incorporating mechanistically complementary biomechanical metrics together with anatomical large PB dramatically improves MACE prediction, identifying almost all future MACE plaques over 3.4 years of follow-up. The additive effect of these three biomechanical variables is mechanistically reinforced by their each being independent predictors of MACE. These destabilizing features are spatially located near each other in MACE plaques compared to similar no-MACE plaques, and likely represent a local “perfect storm” of high-risk features of both plaque anatomical vulnerability (PSS, PSS HI, PB) and local haemodynamic destabilizing influences (ESS, ESSG). Other biomechanical stresses, such as axial plaque stress [26] or other local flow disturbances [27,28], may further increase the prognostic ability of these combined biomechanical and anatomical plaque risk features. Higher-risk biomechanical features co-localised spatially, and our finding that these features are relatively distant from the MLA in most future MACE plaques is important clinically. Standard clinical practice deploying coronary stents around the MLA may not cover areas of adverse biomechanical and anatomical plaque features located substantially proximal or distal to the MLA [29].

Coronary atherosclerotic plaques are complex, lengthy, and heterogeneous, and accumulating evidence suggests that MACE are related less to flow-limiting stenosis than overall plaque burden, be it obstructive or non-obstructive [29]. Our findings suggest the potential value of screening all portions of atherosclerotic plaques for higher-risk biomechanical and anatomical features (Fig. 3D). No lesion with a physiological/high ESS (≥1.3Pa) alone led to MACE during a median follow-up of 3.4 years, suggesting that baseline ESS could act as the first screen. High ESS gradient and high PSS HI were additive in risk-stratifying lesions, leading to a stepwise decision tree to aid plaque risk-stratification. Plaques with low ESS, high ESSG and high PSS HI had a PPV of ≥80 %, whereas different combinations of parameters could identify intermediate-risk lesions. Heterogeneity is a consequence of the dynamic and variable plaque natural history and vascular remodelling along the course of each lesion [30], resulting in changes in plaque and lumen morphology [31], ESS, ESSG, and PSS within individual plaques. A comprehensive plaque risk assessment thus requires careful evaluation of multiple plaque and arterial wall features along the entire lesion, and the co-localised highest-risk portion of the plaque may be distant from the MLA.

4.1. Limitations

This study has some important limitations: (1) Although we studied one of the largest prospectively enrolled patient cohorts of the natural history of atherosclerosis, only 54 % of MACE NCLs were technically suitable for local ESS calculation, potentially introducing some selection bias. However, a large number of randomly selected, well-matched control (non-MACE) plaques were evaluated, and the additive value of combined biomechanical variables was consistently demonstrated in multiple analyses. In addition, patients in our study are well-matched with the main PROSPECT cohort (Supplementary Table 2). (2) This is a retrospective, post-hoc analysis of a specific patient population from the PROSPECT trial, limiting the generalisability of our results. Although it provides an invaluable proof-of-concept incorporating all of the currently available biomechanical and anatomical prognostic metrics, large-scale prospective studies involving a wider patient population with these or other biomechanical/anatomical metrics will be required, assessing both clinical and cost-effectiveness outcomes. (3) Side branches were not considered in our CFD analysis, which could alter the ESS calculation. However, such single-conduit models have reasonable test accuracy to rule out pathological ESS (sensitivity 67.7 %, specificity 90.7 %) [19], and the effect of side branches on ESS can be very localised, and generally <5 % if outflow difference is small [32]. (4) Both ESS and PSS can be calculated from fully-coupled fluid structure interaction (FSI) models, but this requires significantly higher computational power and may provide little incremental prognostic value. (5) Finally, ESS and PSS features were examined by co-registering plaque/artery segments and frames, potentially introducing co-registration errors. However, plaque outcome prediction analysis was performed on whole-plaque level data (i.e. minimum ESS, maximum ESSG, and PSS HI across the whole plaque) to minimize the effects of individual frame misalignment.

4.2. Conclusions

Comprehensive combinations of mechanistically synergistic ESS and PSS and anatomical parameters at baseline were associated with most future MACE from NCLs in PROSPECT (Fig. 5). Identification of the site and magnitude of these biomechanical and anatomical metrics may represent a new tool to guide revascularisation strategies to high-risk plaques, while also providing reassurance for more conservative management for low-risk lesions.

Fig. 5.

Graphical abstract.

Combined biomechanical parameters including endothelial shear stress (ESS), ESS gradient (ESSG) and plaque structural stress (PSS) heterogeneity index (HI) improves prediction of adverse events in patients.

Supplementary Material

Financial support

This work was funded by British Heart Foundation (BHF) grants FS/19/66/34658, PG/16/24/32090, RG71070, RG84554, the BHF Centre for Research Excellence (London, UK), the National Institute of Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (London, UK), National Institute of Health (US) grants R01 HL146144-01A1, R01 HL140498, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20200165), the Swedish Research Council (2021-00456), the Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS-961835), Erik and Edith Fernströms Foundation (FS-2021:0004), and Karolinska Institutet (FS-2020:0007), the Sweden-America Foundation, the Swedish Heart Foundation. We are grateful for the generous support of the Schaubert Family.

Footnotes

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00180466.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sophie Z. Gu: Formal analysis, Software, development, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mona E. Ahmed: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yuan Huang: Supervision, Software, development, Writing – review & editing. Diaa Hakim: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Charles Maynard: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Nicholas V. Cefalo: Writing – review & editing. Ahmet U. Coskun: Software, development, Writing – review & editing. Charis Costopoulos: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Akiko Maehara: Data collection, Writing – review & editing. Gregg W. Stone: Data collection, Writing – review & editing. Peter H. Stone: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Martin R. Bennett: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117449.

References

- [1].Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M, Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective, Eur. Heart J 36 (2015) 1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Steen DL, Khan I, Andrade K, Koumas A, Giugliano RP, Event rates and risk Factors for recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality in a contemporary post acute coronary syndrome population representing 239 234 patients during 2005 to 2018 in the United States, J. Am. Heart Assoc 11 (2022) e022198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, De Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS, Mehran R, McPherson J, Farhat N, Marso SP, Parise H, Templin B, White R, Zhang Z, Serruys PW, A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis, N, Engl. J. Med 364 (2011) 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Calvert PA, Obaid DR, O’Sullivan M, Shapiro LM, McNab D, Densem CG, Schofield PM, Braganza D, Clarke SC, Ray KK, West NEJ, Bennett MR, Association between IVUS findings and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 4 (2011) 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cheng JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, De Boer SPM, Kardys I, Heo JH, Akkerhuis KM, Oemrawsingh RM, Van Domburg RT, Ligthart J, Witberg KT, Regar E, Serruys PW, Van Geuns RJ, Boersma E, In vivo detection of high-risk coronary plaques by radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound and cardiovascular outcome: results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study, Eur. Heart J 35 (2014) 639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, La Manna A, Burzotta F, Ozaki Y, Marco V, Boi A, Fineschi M, Fabbiocchi F, Taglieri N, Niccoli G, Trani C, Versaci F, Calligaris G, Ruscica G, Di Giorgio A, Vergallo R, Albertucci M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Tamburino C, Crea F, Alfonso F, Arbustini E, On behalf of C. Investigators, Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: the CLIMA study, Eur. Heart J 41 (2019) 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Waksman R, Di Mario C, Torguson R, Ali ZA, Singh V, Skinner WH, Artis AK, Ten Cate T, Powers E, Kim C, Regar E, Wong SC, Lewis S, Wykrzykowska J, Dube S, Kazziha S, van der Ent M, Shah P, Craig PE, Zou Q, Kolm P, Brewer HB, Garcia-Garcia HM, Samady H, Tobis J, Zainea M, Leimbach W, Lee D, Lalonde T, Skinner W, Villa A, Liberman H, Younis G, de Silva R, Diaz M, Tami L, Hodgson J, Raveendran G, Goswami N, Arias J, Lovitz L, Carida II R, Potluri S, Prati F, Erglis A, Pop A, McEntegart M, Hudec M, Rangasetty U, Newby D, Identification of patients and plaques vulnerable to future coronary events with near-infrared spectroscopy intravascular ultrasound imaging: a prospective, cohort study, Lancet 394 (2019) 1629–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Williams MC, Moss AJ, Dweck M, Adamson PD, Alam S, Hunter A, Shah ASV, Pawade T, Weir-McCall JR, Roditi G, van Beek EJR, Newby DE, Nicol ED, Coronary artery plaque characteristics associated with adverse outcomes in the SCOT-HEART study, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 73 (2019) 291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brown AJ, Teng Z, Evans PC, Gillard JH, Samady H, Bennett MR, Role of biomechanical forces in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis, Nat. Rev. Cardiol 13 (2016) 210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, Makita Y, Nakamura S, Kawasaki T, Takahashi A, Katsuki T, Nakamura S, Namiki A, Hirohata A, Matsumura T, Yamazaki S, Yokoi H, Tanaka S, Otsuji S, Yoshimachi F, Honye J, Harwood D, Reitman M, Coskun AU, Papafaklis MI, Feldman CL, Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION study, Circulation 126 (2012) 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stone PH, Maehara A, Coskun AU, Maynard CC, Zaromytidou M, Siasos G, Andreou I, Fotiadis D, Stefanou K, Papafaklis M, Michalis L, Lansky AJ, Mintz GS, Serruys PW, Feldman CL, Stone GW, Role of low endothelial shear stress and plaque characteristics in the prediction of nonculprit major adverse cardiac events, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 11 (2018) 462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Thondapu V, Mamon C, Poon EKW, Kurihara O, Kim HO, Russo M, Araki M, Shinohara H, Yamamoto E, Dijkstra J, Tacey M, Lee H, Ooi A, Barlis P, Jang I-K, On behalf of the M.G.H.O.C.T.R. Investigators, High spatial endothelial shear stress gradient independently predicts site of acute coronary plaque rupture and erosion, Cardiovasc. Res 117 (2021) 1974–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gu SZ, Bennett MR, Plaque structural stress: detection, determinants and role in atherosclerotic plaque rupture and progression, Front. Cardiovasc. Med 9 (2022) 875413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Teng Z, Brown AJ, Calvert PA, Parker RA, Obaid DR, Huang Y, Hoole SP, West NEJ, Gillard JH, Bennett MR, Coronary plaque structural stress is associated with plaque composition and subtype and higher in acute coronary syndrome, Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 7 (2014) 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brown AJ, Teng Z, Calvert PA, Rajani NK, Hennessy O, Nerlekar N, Obaid DR, Costopoulos C, Huang Y, Hoole SP, Goddard M, West NEJ, Gillard JH, Bennett MR, Plaque structural stress estimations improve prediction of future major adverse cardiovascular events after intracoronary imaging, Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 9 (2016) 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Costopoulos C, Huang Y, Brown AJ, Calvert PA, Hoole SP, West NEJ, Gillard JH, Teng Z, Bennett MR, Plaque rupture in coronary atherosclerosis is associated with increased plaque structural stress, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 10 (2017) 1472–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Costopoulos C, Maehara A, Huang Y, Brown AJ, Gillard JH, Teng Z, Stone GW, Bennett MR, Heterogeneity of plaque structural stress is increased in plaques leading to MACE: insights from the PROSPECT study, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 13 (2020) 1206–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li Y, Gutíérrez-Chico JL, Holm NR, Yang W, Hebsgaard L, Christiansen EH, Mæng M, Lassen JF, Yan F, Reiber JHC, Tu S, Impact of side branch modeling on computation of endothelial shear stress in coronary artery disease, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 66 (2015) 125–135, 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Giannopoulos AA, Chatzizisis YS, Maurovich-Horvat P, Antoniadis AP, Hoffmann U, Steigner ML, Rybicki FJ, Mitsouras D, Quantifying the effect of side branches in endothelial shear stress estimates, Atherosclerosis 251 (2016) 213–218, 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].S. PH, C. A. Umit, P. Francesco, Ongoing methodological approaches to improve the in vivo assessment of local coronary blood flow and endothelial shear stress, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 66 (2015) 136–138, 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Coskun AU, Yeghiazarians Y, Kinlay S, Clark ME, Ilegbusi OJ, Wahle A, Sonka M, Popma JJ, Kuntz RE, Feldman CL, Stone PH, Reproducibility of coronary lumen, plaque, and vessel wall reconstruction and of endothelial shear stress measurements in vivo in humans, Catheter, Cardiovasc. Interv 60 (2003) 67–78, 10.1002/ccd.10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gu SZ, Costopoulos C, Huang Y, Bourantas C, Woolf A, Sun C, Teng Z, Losdat S, Räber L, Samady H, Bennett MR, High-intensity statin treatment is associated with reduced plaque structural stress and remodelling of artery geometry and plaque architecture, Eur. Hear. J. Open 1 (2021) oeab039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Erlinge D, Maehara A, Ben-Yehuda O, Bøtker HE, Maeng M, Kjøller-Hansen L, Engstrøm T, Matsumura M, Crowley A, Dressler O, Mintz GS, Fröbert O, Persson J, Wiseth R, Larsen AI, Okkels Jensen L, Nordrehaug JE, Bleie Ø, Omerovic E, Held C, James SK, Ali ZA, Muller JE, Stone GW, Ahlehoff O, Amin A, Angerås O, Appikonda P, Balachandran S, Barvik S, Bendix K, Bertilsson M, Boden U, Bogale N, Bonarjee V, Calais F, Carlsson J, Carstensen S, Christersson C, Christiansen EH, Corral M, De Backer O, Dhaha U, Dworeck C, Eggers K, Elfström C, Ellert J, Eriksen E, Fallesen C, Forsman M, Fransson H, Gaballa M, Gacki M, Götberg M, Hagström L, Hallberg T, Hambraeus K, Haraldsson I, Harnek J, Havndrup O, Hegbom K, Heigert M, Helqvist S, Herstad J, Hijazi Z, Holmvang L, Ioanes D, Iqbal A, Iversen A, Jacobson J, Jakobsen L, Jankovic I, Jensen U, Jensevik K, Johnston N, Jonasson TF, Jørgensen E, Joshi F, Kajermo U, Kåver F, Kelbæk H, Kellerth T, Kish M, Koenig W, Koul S, Lagerqvist B, Larsson B, Lassen JF, Leiren O, Li Z, Lidell C, Linder R, Lindstaedt M, Lindström G, Liu S, Løland KH, Lønborg J, Márton L, Mir-Akbari H, Mohamed S, Odenstedt J, Ogne C, Oldgren J, Olivecrona G, Östlund-Papadogeorgos N, Ottesen M, Packer E, Palmquist ÅM, Paracha Q, Pedersen F, Petursson P, Råmunddal T, Rotevatn S, Sanchez R, Sarno G, Saunamäki KI, Scherstén F, Serruys PW, Sjögren I, Sørensen R, Srdanovic I, Subhani Z, Svensson E, Thuesen A, Tijssen J, Tilsted H-H, Tödt T, Trovik T, Våga BI, Varenhorst C, Veien K, Vestman E, Völz S, Wallentin L, Wykrzykowska J, Zagozdzon L, Zamfir M, Zedigh C, Zhong H, Zhou Z, Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): a prospective natural history study, Lancet 397 (2021) 985–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].V Bourantas C, Zanchin T, Torii R, Serruys PW, Karagiannis A, Ramasamy A, Safi H, Coskun AU, Koning G, Onuma Y, Zanchin C, Krams R, Mathur A, Baumbach A, Mintz G, Windecker S, Lansky A, Maehara A, Stone PH, Raber L, Stone GW, Shear stress estimated by quantitative coronary angiography predicts plaques prone to progress and cause events, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 13 (2020) 2206–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tufaro V, Safi H, Torii R, Koo B-K, Kitslaar P, Ramasamy A, Mathur A, Jones DA, Bajaj R, Erdoğan E, Lansky A, Zhang J, Konstantinou K, Little CD, Rakhit R, V Karamasis G, Baumbach A, V Bourantas C, Wall shear stress estimated by 3D-QCA can predict cardiovascular events in lesions with borderline negative fractional flow reserve, Atherosclerosis 322 (2021) 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee JM, Choi G, Koo B-K, Hwang D, Park J, Zhang J, Kim K-J, Tong Y, Kim HJ, Grady L, Doh J-H, Nam C-W, Shin E-S, Cho Y-S, Choi S-Y, Chun EJ, Choi J-H, Nørgaard BL, Christiansen EH, Niemen K, Otake H, Penicka M, de Bruyne B, Kubo T, Akasaka T, Narula J, Douglas PS, Taylor CA, Kim H-S, Identification of high-risk plaques destined to cause acute coronary syndrome using coronary computed tomographic angiography and computational fluid dynamics, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 12 (2019) 1032–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Timmins LH, Molony DS, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Oshinski JN, Giddens DP, Samady H, Oscillatory wall shear stress is a dominant flow characteristic affecting lesion progression patterns and plaque vulnerability in patients with coronary artery disease, J. R. Soc. Interface 14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoogendoorn A, Kok AM, Hartman EMJ, de Nisco G, Casadonte L, Chiastra C, Coenen A, Korteland S-A, Van der Heiden K, Gijsen FJH, Duncker DJ, van der Steen AFW, Wentzel JJ, Multidirectional wall shear stress promotes advanced coronary plaque development: comparing five shear stress metrics, Cardiovasc. Res 116 (2020) 1136–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stone PH, Libby P, Boden WE, Fundamental pathobiology of coronary atherosclerosis and clinical implications for chronic ischemic Heart disease management—the plaque hypothesis: a narrative review, JAMA Cardiol 8 (2023) 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Antoniadis AP, Papafaklis MI, Takahashi S, Shishido K, Andreou I, Chatzizisis YS, Tsuda M, Mizuno S, Makita Y, Domei T, Ikemoto T, Coskun AU, Honye J, Nakamura S, Saito S, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH, Arterial remodeling and endothelial shear stress exhibit significant longitudinal heterogeneity along the length of coronary plaques, J Am Coll Cardiol Img 9 (2016) 1007–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gu SZ, Huang Y, Costopoulos C, Jessney B, Bourantas C, Teng Z, Losdat S, Maehara A, Räber L, Stone GW, Bennett MR, Heterogeneous plaque–lumen geometry is associated with major adverse cardiovascular events, Eur. Hear. J. Open 3 (2023) oead038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shi Y, Zheng J, Yang N, Chen Y, Sun J, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Gao Y, Li S, Zhu H, Acosta-Cabronero J, Xia P, Teng Z, The effect of subbranch for the quantification of local hemodynamic environment in the coronary artery: a computed tomography angiography–based computational fluid dynamic analysis, Emerg. Crit. Care Med 2 (2022). https://journals.lww.com/eccm/fulltext/2022/12000/the_effect_of_subbranch_for_the_quantification_of.2.aspx. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.