Abstract

Several neurochemical systems converge in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) to regulate cognitive and motivated behaviors. A rich network of endogenous opioid peptides and receptors spans multiple PFC cell types and circuits, and this extensive opioid system has emerged as a key substrate underlying reward, motivation, affective behaviors, and adaptations to stress. Here, we review the current evidence for dysregulated cortical opioid signaling in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders. We begin by providing an introduction to the basic anatomy and function of the cortical opioid system, followed by a discussion of endogenous and exogenous opioid modulation of PFC function at the behavioral, cellular, and synaptic level. Finally, we highlight the therapeutic potential of endogenous opioid targets in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, synthesizing clinical reports of altered opioid peptide and receptor expression and activity in human patients and summarizing new developments in opioid-based medications.

Keywords: plasticity, interneurons, electrophysiology, addiction, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), rodent models

1. The Prefrontal Cortex

The conceptualization of the cerebral cortex as the seat of human cognition first originated in the early nineteenth century with the idea that particular physiological functions could be ascribed to discrete areas of the brain (Funahashi, 2022; Zola-Morgan, 1995). Shortly thereafter, early ablation studies began to demonstrate specific functions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), showing that prefrontal lesions resulted in distinct deficits in decision-making and mnemonic processes (Anderson et al., 1976; CF, 1936; Funahashi, 2022; Gross and Weiskrantz, 1962; Mishkin, 1957). Within the last few decades, PFC research has seen a renaissance of interest, fueled by a collection of fundamental studies that established an exciting role for the PFC in multiple facets of working memory and higher-order cognitive processing (Funahashi et al., 1989; Fuster and Alexander, 1971; McCarthy et al., 1994; Pardo et al., 1991; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Zola-Morgan, 1995). In addition to these executive functions, the PFC regulates reward, motivation, and affective processing—dysfunction of which is a core feature of psychiatric disorders. Patients with psychiatric disorders commonly demonstrate altered resting-state connectivity of cortical networks (Chai et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2011; Kaiser et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2010; Moningka et al., 2019) and structural alterations in frontal cortex gray matter (Almeida et al., 2009; Ancelin et al., 2019; Vita et al., 2012), consistent with pathological changes to PFC function. For example, conceptual frameworks for the development and maintenance of drug addiction, including opioid use disorder (OUD), have positioned the PFC as a key circuit element contributing to drug-related executive dysfunction (Koob, 2020; Koob and Volkow, 2010). Indeed, repeated opioid use is associated with reduced behavioral flexibility, increased decisional and motor impulsivity and loss of inhibitory control (Jones et al., 2016; Lee and Pau, 2002), which functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have consistently correlated with reduced activity of cortical cognitive control regions (Ceceli et al., 2023; Fu et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2013).

1.1. General Organization

In humans and nonhuman primates, the PFC can be functionally organized into anatomically distinct compartments: the medial PFC (mPFC)-- consisting of the cingulate cortex and dorsal and ventral mPFC, the lateral PFC, and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) which sits on the ventral side of the frontal lobe (Kolk and Rakic, 2022). Reciprocal connectivity with sensory, motor, and various subcortical structures confers the PFC with “top-down” control of cognitive and decision-making processes. The lateral PFC is closely associated with multiple sensory cortices, and has been found to be critical for various aspects of executive control (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Tanji and Hoshi, 2008). The mPFC and OFC form direct connections with other limbic structures through which they regulate motivational and affective processing (Fuster, 2000; Miller and Cohen, 2001). Though subdivisions of the PFC display loose localization of function, dense connections between different areas of the PFC allow for information transfer across cytoarchitectonic boundaries. Historically, anatomical differences between rodent and primate prefrontal areas have generated contention around the cross-species expansion of PFC research to include rodent PFC. The rodent PFC can be similarly divided into orbital and cingulate cortices, along with medial dorsal and ventral areas known as prelimbic cortex (PL-PFC) and infralimbic cortex (IL-PFC), respectively (Anastasiades and Carter, 2021). Concerns that an area directly homologous to the primate dorsolateral PFC does not exist within the agranular rodent PFC (Brown and Bowman, 2002; Carlén, 2017; Laubach et al., 2018) have sparked a long-standing debate concerning the relevance of rodent PFC studies for understanding the primate PFC. Despite the consensus that there are some important anatomical differences across species, the rodent PFC exhibits core functional commonalities with primate PFC, particularly the agranular cingulate cortex.

1.2. Cortical Cell Types

The PFC consists of excitatory glutamatergic pyramidal cells and a smaller, yet highly diverse, network of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons INs that interact within cortical microcircuitry to exert fine control over PFC function. Pyramidal cells comprise approximately 80% of all cortical neurons and project to many other brain areas. Cells within superficial layers are more likely to project to contralateral cortex and the basolateral amygdala, whereas pyramidal cells in deeper layers send extensive projections to striatum, thalamic nuclei, and various midbrain centers (Anastasiades and Carter, 2021; Gabbott et al., 2005; Harris and Shepherd, 2015). Pyramidal cells also form recurrent local connections, producing reverberating excitation that is thought to be important for information processing within cortical circuits (Harris and Shepherd, 2015; Morishima and Kawaguchi, 2006). In rodent studies, three main classes of neocortical INs have been identified based on the mutually exclusive expression of the molecular markers somatostatin (SST), parvalbumin (PV), or vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (Tremblay et al., 2016). Each IN population harbors a unique set of morphological and electrophysiological properties that collectively facilitate distinct motifs of cortical inhibition. Most SST-INs target the dendritic region of pyramidal cells where they provide feedback inhibition and regulate synaptic plasticity (Donato et al., 2023; Tremblay et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2019). By contrast, PV cells mainly innervate the perisomatic region of nearby pyramidal cells and participate in rapid feedforward inhibition to control PN spike-timing, excitability, and ensemble activity (Fish and Joffe, 2022; Nahar et al., 2021). VIP-INs primarily provide disinhibition, preferentially synapsing onto other GABAergic INs to relieve pyramidal cells from inhibition. While SST, PV, and VIP neurons span all cortical layers, the relative composition of IN subtypes varies by layer. PV-INs are more abundant in deeper layers (L4–6), whereas VIP-INs reside primarily in superficial layers (L1–3) (Rudy et al., 2011). Overall, SST-INs are expressed with comparable abundance across all layers, but there are important differences in subtype-specific expression patterns (Nigro et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2023). For example, the disinhibitory X94 SST-IN subtype is highly expressed in L4/5a. Finally, neurogliaform cells and canopy cells are unique types of INs that appear only within L1(Schuman et al., 2019). Thus, the diversity of cells and circuit motifs within PFC and across cortical layers indicates that cellular expression patterns of opioid system components play an important role in dictating function at a network level.

2. The Endogenous Opioid System

Naturally occurring opioid peptides and their cognate receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, forming what is collectively known as the endogenous opioid system (Trigo et al., 2010). This system is widely expressed throughout the brain and plays a major role in regulating physiological processes related to cognition, sensation, and behavior (Le Merrer et al., 2009; Trigo et al., 2010). While the idea of multiple opioid receptors was proposed in the 1960’s as a plausible explanation for the varied actions of opioid drugs (Snyder and Pasternak, 2003), it was not until the 1970’s that radioligand binding assays revealed endogenous binding sites through which opioid drugs exert their effects (Box 1) (Goldstein et al., 1971; Pert et al., 1973; Simon et al., 1973).

Box: History and pharmacology of natural and synthetic opioid compounds.

References to the extraction of opium from the opium poppy plant date back to around 3000 BC in Mesopotamia where the pleasurable effects of the “joy plant” were first recorded (Shafi et al., 2022). The use of opium for the treatment of pain and various ailments continued to diffuse throughout Asian, European, and eventually Western cultures, culminating in the isolation of morphine by Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Serturner at the beginning of the 19th century (Aragón-Poce et al., 2002; Krishnamurti and Rao, 2016). Originally called “Morphium” after the Greek god of sleep and dreams (Krishnamurti and Rao, 2016), morphine was the first alkaloid to be extracted from the opium plant, quickly followed by codeine and thebaine (Shafi et al., 2022). Shortly thereafter, the early 1900s saw the development of highly potent semi-synthetic and synthetic opioid drugs which are manufactured from naturally occurring opioid compounds or man-made chemicals. Some semi-synthetic opioids include buprenorphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and heroin (diacetylmorphine), whereas common synthetic opioids include methadone, fentanyl, and fentanyl analogues (Carelli et al., 2022). Synthetic opioids generally act at the same receptor targets as natural opioids to elicit their pharmacological effects, though they are dangerously more potent. For example, fentanyl is approximately 50–100 times more potent than morphine (Shafi et al., 2022), leading to high abuse potential and increased risk of drug-related death. Opioid drugs usually bind with high affinity to MOR as full or partial agonists, though several opioids demonstrate receptor promiscuity through which they may produce different effects (Pathan and Williams, 2012). Measurements of binding affinity can be obtained through competitive binding assays that yield a dissociation constant (Ki), a commonly used metric of how strongly a drug binds to a particular type of receptor (inverse relationship).

Cloning studies identified genes for the three main subtypes of opioid receptors, mu (MOR), kappa (KOR), and delta (DOR), each distinct in their physiology and selectivity for endogenous opioid peptides and exogenous opiates (Table 1) (Evans et al., 1992; Kieffer et al., 1992; Snyder and Pasternak, 2003; Stein, 2016; Valentino and Volkow, 2018). The endogenous ligands for the classical opioid receptors consist of three families of opioid peptides: β-endorphins, enkephalins (Enks), and dynorphins (Dyns), which are derived from the respective precursor molecules pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), pro-enkephalin (Penk), and pro-dynorphin (Pdyn) (Shenoy, 2022; Gerrits, 2003). While each opioid receptor type can be activated by more than one opioid peptide (Gomes et al., 2020), β-endorphins generally exhibit the highest affinity for MOR, Enks for DOR and MOR, and Dyns for KOR (Fricker et al., 2020; Stein, 2016). In contrast to fast neurotransmission, neuropeptide release is usually precipitated by intense bouts of neuronal activity and can diffuse to distant sites to modulate GPCR activity on a slower timescale (Van Den Pol, 2012). Shortly after the discovery of the three classical opioid receptors, a fourth member of the opioid receptor family was cloned. Originally described as an orphan receptor, this receptor was termed the nociceptin/orphanin FQ opioid peptide receptor (NOP), following the discovery of its endogenous ligand, a dynorphin-like neuropeptide nociception/orphanin FQ (Toll et al., 2016; Zaveri, 2016). The NOP receptor is expressed throughout the central nervous system and has been extensively reviewed (Bigoni et al., 2000; Toll et al., 2016); however, characterization of the NOP receptor system within PFC circuitry is less well developed and will not be discussed further in this review.

Table 1.

Binding affinity of common opioid drugs for MOR, DOR, and KOR.

| Compound | MOR Ki (nM) | DOR Ki (nM) | KOR Ki (nM) | Rank Potency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine1 | 0.9 | 34 | 27 | MOR >> DOR=KOR |

| Codeine2 | 79 | >10,000 | >10,000 | MOR > DOR=KOR |

| Fentanyl2 | 0.39 | >1,000 | 255 | MOR >> KOR >> DOR |

| Hydrocodone1 | 1,800 | >2,000 | >10,000 | MOR > DOR=KOR |

| Hydromorphone1 | 9.4 | 310 | >1,600 | MOR > DOR > KOR |

| Methadone2 | 0.72 | >1,000 | >1,000 | MOR >> DOR=KOR |

| Morphine1,2 | 14–74 | 2,500 | 538–2,000 | MOR > DOR=KOR |

| Naloxone1 | 0.93–14 | 17–520 | 2.3–270 | MOR > KOR > DOR |

| Oxycodone1 | 780 | >10,000 | >2,000 | MOR > DOR=KOR |

| Oxymorphone1 | 11 | >2,000 | >2,000 | MOR >> DOR=KOR |

Data obtained from selected comparative studies included in the Psychoactive Drug Screening Program Ki database (Roth et al., 2000). As published Ki values may vary based on preparation, species, and radioligand, we selected references that assessed multiple drugs to enable comparisons across compounds: (Olson et al., 2019)1; (Raynor et al., 1994)2. Additional studies are available in the Ki database that largely corroborate the rank potencies displayed here.

Opioid receptors belong to the seven transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. Upon activation by exogenous opioids or endogenous opioid peptides, these receptors generally engage canonical “inhibitory” Gai/o-dependent signaling to inhibit cAMP production, dampen neuronal activity, and suppress neurotransmitter release. Opioid receptors can be located postsynaptically where they can attenuate neural activity by somatic hyperpolarization, or presynaptically in axon terminals where they modulate intracellular signaling pathways and ion channels to alter neurotransmitter release (Reeves et al., 2022). All three opioid receptors negatively regulate cell excitability by reducing activity of pre-and postsynaptic Ca2+ channels and activating G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels (Law et al., 2000; Reeves et al., 2022; Stein, 2016; T Lamberts and R Traynor, 2013; Trigo et al., 2010). Indeed, opioid-induced membrane hyperpolarization and decreased Ca2+ influx have been demonstrated by several ex vivo and in vitro electrophysiological studies performed in rodent cortical tissue (Férézou et al., 2007; Grudt and Williams, 1993; Johnson and North, 1992; Svoboda and Lupica, 1998; Tanaka and North, 1994). In addition to G protein-dependent signaling, GPCRs can also activate β-arrestin pathways that mediate G protein-independent signaling (Che et al., 2021). While this is an ongoing area of research, it has been hypothesized that β-arrestin signaling promotes several adverse side effects associated with current opioids (Manglik et al., 2016), motivating a search for novel compounds that preferentially recruit G protein-coupled signaling with minimal β-arrestin activity.

2.1. Cortical Opioid Peptide and Receptor Systems

Receptor localization studies in humans and rodents have found highly homologous distributions of the three opioid receptor systems across cortical and subcortical structures (Mansour et al., 1987; Valentino and Volkow, 2018). High expression within motivational and affective hubs supports an important role for the endogenous opioid system in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders. All three opioid receptors and their cognate peptide ligands are interspersed throughout the neocortex (Mansour et al., 1988), and electrophysiological and immunohistochemical evidence shows that cortical opioid receptors are expressed on different subsets of inhibitory and excitatory cells (Figure 1). Immunolabeling and autoradiography have been integral to the initial characterization of opioid receptor expression patterns. Though these methods are powerful tools for determining the distribution and density of receptors, their utility is limited by several notable caveats that are important to consider. Radioligand binding, historically, does not have the resolution to discern whether binding sites are expressed locally or on afferents (but, see (Prokop et al., 2021) for contemporary advancements in subcellular resolution). Radioligands may also face competition with endogenous ligands, and agonist radioligands have a higher affinity for GPCRs in the activated state over in the inactive G protein-bound state. Thus, there are several reasons why radioligand binding experiments may not consistently capture the entire receptor population.

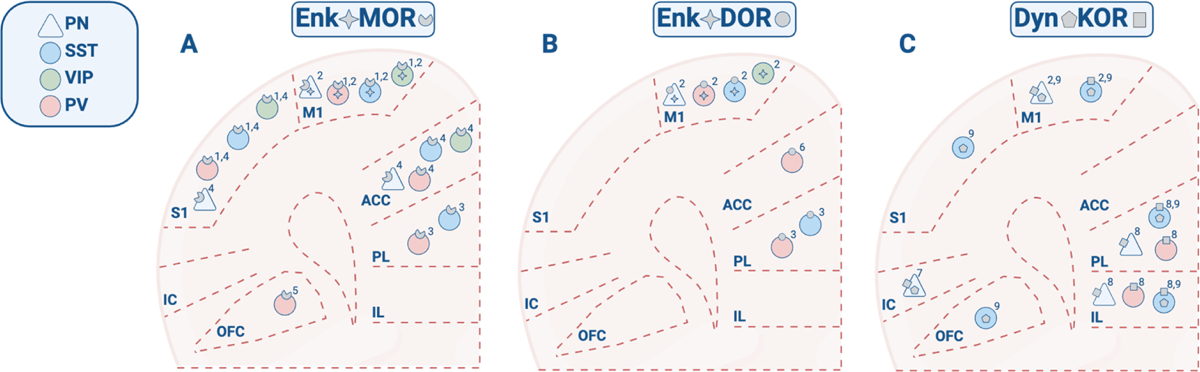

Figure 1. Cell type-specific expression of cortical opioid receptors and peptides.

Cortex-wide receptor and peptide expression patterns were reconstructed from studies reporting discrete brain regions and cell types. Note that the absence of a peptide or receptor in this diagram does not necessarily indicate complete lack of cortical expression. Peptide/receptor symbols represent mRNA, gene, or protein expression. A) MOR and Enk expression. B) DOR and Enk expression. C) KOR and Dyn expression. Data obtained from: (Taki et al., 2000)1; (Smith et al., 2019)2; (Jiang et al., 2021)3; (Zamfir et al., 2023)4; (Lau et al., 2020)5; (Birdsong et al., 2019)6; (Pina et al., 2020)7; (Yarur et al., 2022)8; (Sohn et al., 2014)9. Sections of cortex are compressed along the anterior-posterior axis for stylistic purposes.

Antibody binding is generally not thought to be affected by receptor state or endogenous ligands, but achieving adequate selectivity with anti-GPCR antibodies is notoriously difficult, particularly for immunohistochemistry. Genetic approaches can also be taken to examine GPCR function, but these studies must be performed in rodents and there can be strain-specific considerations to keep in mind. For example, the only commercially available MOR-Cre mice display reduced MOR expression (Liu et al., 2021a).(Liu et al., 2021b)(Liu et al., 2021)(Liu et al., 2021) The recent development of MOR promotor-based viral constructs (Salimando et al., 2023) circumvents several of these obstacles, enabling cell type-specific genetic access to MOR-expressing cells and providing an exciting avenue for high-fidelity labeling and manipulation of opioid system components. Analogous tools to manipulate KOR and DOR would provide further advantages for mechanistic studies to examine opioid neurobiology in any model species.

2.1.1. Mu-Opioid Receptor Expression and Signaling

In rodents, cortical MOR expression is largely confined to GABAergic INs, showing very limited expression in pyramidal cells (Férézou et al., 2007; Taki et al., 2000). MOR signaling is therefore thought to be disinhibitory, indirectly augmenting pyramidal cell activity through a suppression of IN inhibitory output. A growing literature suggests that cellular expression patterns vary across cortical areas and potentially by species. In humans, autoradiography of postmortem tissue shows that in frontal, insular, and cingulate cortices, MORs are located primarily in L3, followed by L1 and L2 (Hiller and Fan, 1996). Double immunolabeling of the rat neocortex has shown that MOR protein expression is scattered across L2–4 and primarily localized to VIP-expressing INs and detected at very low levels in other GABAergic subpopulations such as PV and SST cells (Taki et al., 2000). In contrast, recent analysis of mouse visual and motor cortex single-cell RNA sequencing data has revealed that the Oprm1 gene, encoding for MOR, is significantly expressed in both VIP- and SST-INs, and in PV-INs and deep layer pyramidal cells to a lesser extent (Smith et al., 2019). Interestingly, recent behavioral studies have demonstrated behaviorally relevant actions for MORs on PV-INs in the PL-PFC (Jiang et al., 2021), indicating an essential role for MOR-containing PV-INs specifically in the PL cortex in opioid-related behavior, despite low levels of MOR/PV colocalization in frontoparietal regions (Taki et al., 2000).

More recent reports suggest that cell-specific MOR expression patterns differ by cortical area and layer. In superficial L1, MOR-expressing INs show high expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY), yet lack Enk co-expression like MOR-containing VIP-INs, suggesting that L1 NPY and MOR co-expressing cells represent a functionally distinct cell population (Férézou et al., 2007). MOR-positive SST cells are most prominent in the ACC, while other cortical areas, like S1, contain a greater population of MOR-expressing PV-INs, (Zamfir et al., 2023),. Importantly, female mice show a higher density of MOR+ neurons compared to males in both PFC and S1. In addition to expression with GABAergic INs, MOR is also expressed within neocortical excitatory circuits. In the ACC and S1, MOR expression assessed via genetically engineered Oprm1-mCherry fluorescence can be observed in deep-layer L6b cells, providing a potential anatomical substrate for MOR-mediated modulation of cortico-thalamic circuitry (Zamfir et al., 2023). Excitotoxic lesioning of afferents arriving to the ACC reduces DAMGO binding, as does nonspecific ablation of cortical neurons, indicating that MOR is expressed at pre- and postsynaptic sites in ACC (Vogt et al., 1995).

β-Endorphins are primarily produced by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland and by pro-opiomelanocortic cells in the hypothalamus (Pilozzi et al., 2020). Thus, POMC, encoding for pro-opiomelanocortin, is weakly expressed in human cortex (Fricker et al., 2020; Uhlén et al., 2015), and detailed observations of cortical β-Endorphin expression are sparse. In human postmortem brain tissue, β-Endorphin immunoreactivity has been detected in several regions of the cerebral cortex, though most densely in the cingulate and frontal cortex (Bernstein et al., 1996). The majority of these cells presented morphologically as GABAergic INs and were surrounded by β-Endorphin reactive terminals, yet lacked intracellular immunoreactivity, suggesting that cortical INs are heavily innervated by β-endorphinergic cells yet do not produce the peptide themselves. In addition, circulating β-endorphin may be directed to cortical areas via cerebrospinal fluid (Veening et al., 2012). Early studies in the rat brain, did not detect β-Endorphin in the cerebral cortex by radioimmunoassay (Rossier et al., 1977), but Lau et al. have provided recent evidence of β-Endorphin expression in the lateral and medial regions of the mouse OFC using immunohistochemistry (Lau et al., 2020). These discrepancies could represent potential species and/or regional differences in β-Endorphin production, or inadequate sensitivity of radioimmunoassay for detecting low levels of β-Endorphin.

Based on the limited cortical expression of β-Endorphins, Enk peptides seem positioned to be the primary endogenous agonist for neocortical MOR. Enk protein expression has been observed across superficial and deep layers of the rodent cortex in both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons (Casello et al., 2022; McGinty, 1985; McGINTY et al., 1984). Matching reports of cortical MOR expression, the Penk gene, encoding for pro-enkephalin, is detected at high levels in VIP-INs and lower levels in PV-INs, SST-INs, and IT glutamatergic cells in mouse visual and motor cortex (Casello et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2019). Consistent with reports of Penk expression, Enk peptides are frequently co-expressed by MOR-containing INs (Férézou et al., 2007; Taki et al., 2000), suggesting MOR-containing cells are equipped to negatively regulate presynaptic activity in a cell-autonomous manner.

2.1.2. Delta-Opioid Receptor Expression and Signaling

Evidence of diffuse DOR expression throughout the cortex has been shown by an array of genetic and molecular approaches. In human frontal cortex tissue, histology and receptor binding assays have indicated a strong presence of DORs (Olianas et al., 2009; Peckys and Landwehrmeyer, 1999). In accordance with receptor protein expression patterns, in-situ hybridization of human postmortem tissue shows intense OPRD1 mRNA labeling across L2–5 of the cerebral cortex in both pyramidal and non-pyramidal cells (Peckys and Landwehrmeyer, 1999), though autoradiography of human postmortem tissue reports that peak levels of DOR binding are in L1 and L2 (Hiller and Fan, 1996). In rodent cortex, DOR exhibits similar expression patterns to MOR. Double-fluorescent knock-in mice expressing DOR-eGFP and MOR-mCherry have shown DOR/MOR co-expression in multiple cortical areas, including OFC, PL-PFC, IL-PFC, insular cortex, cingulate cortex, and sensory and motor cortices (Erbs et al., 2015). These findings are consistent with reports of Oprd1 mRNA in rodent insular, cingulate, and frontal areas (Mansour et al., 1994).

DOR localization on specific GABAergic subpopulations has been observed in several limbic areas (He et al., 2021), yet published accounts of cell-specific DOR expression in the cortex are less common. RNA sequencing of neurons harvested from mouse visual and motor cortex indicates that expression of Oprd1 is enhanced in SST and PV-expressing INs and weakly present in IT-type pyramidal cells (Smith et al., 2019). Studies have also shown that between 90–95% of PV-INs in the ACC express Oprd1 (Birdsong et al., 2019), though a recent study by Jiang et al. describes an essential role for DOR signaling in PL-PFC SST cells in morphine-induced plasticity and behavior (Jiang et al., 2021). In cultured cortical cells, double immunolabeling has revealed that approximately half of dopamine D1 receptor-expressing cells also show immunoreactivity for DOR (Olianas et al., 2012). Finally, excitotoxic ablation of cortical neurons – but not afferent axons – reduces DPDPE binding, suggesting that, unlike MOR and KOR, DOR is not significantly expressed at presynaptic glutamatergic synapses within PFC (Vogt et al., 1995).

While overlapping distributions of Oprd1 and Penk mRNA can be observed across cortex, Penk transcripts are present at higher levels in areas of the paleocortex such as the piriform cortex, while Oprd1 mRNA is enriched in neocortex (Mansour et al., 1993). Within cortical areas, Oprd1 and Penk mRNA diverge in their laminar distribution. For example, Penk mRNA is primarily localized to layers 2 and 6 of the neocortex while Oprd1 mRNA and DOR binding can be found in layers 2, 3, 5, and 6 (Mansour et al., 1993). This dissociation between peptide and receptor expression has been observed in several other forebrain and hindbrain structures (Mansour et al., 1993), indicating that DORs may be primarily targeted by long-range enkephalinergic terminals or other locally expressed opioid peptides such as endorphins (Gomes et al., 2020).

2.1.3. Kappa-Opioid Receptor Expression and Signaling

Though present in only a small subset of cortical neurons, Dyn/KOR signaling exerts significant neuromodulatory influence over cortical circuitry (thoroughly reviewed in (Tejeda et al., 2021)). In the PFC, KOR-immunoreactive axon terminals have been observed at excitatory and inhibitory-type synapses. A subset of KOR-immunoreactive axon terminals also resemble catecholaminergic terminals, consistent with reports of KOR actions on local dopamine transmission (Svingos and Colago, 2002). Recent work from Yarur and colleagues has shown that in the mPFC, Oprk1 mRNA is largely expressed in excitatory cells, with very limited expression in IN subpopulations (Yarur et al., 2022). KOR+ cells were primarily observed in deeper layers of the mPFC, consistent with reports of KOR expression in L4 and L5 in humans (Hiller and Fan, 1996).

Dyn immunoreactivity has been noted across the cerebral cortex (Khachaturian et al., 1982; Lewis et al., 1984). In primary somatosensory areas, Pdyn mRNA has been almost exclusively observed in SST-INs (Sohn et al., 2014), consistent with recent reports of high Pdyn gene expression in SST-INs of the mouse visual and motor cortices (Smith et al., 2019). In contrast, PFC Pdyn-expressing cells are mainly glutamatergic projection neurons (Abraham et al., 2021; Baird et al., 2021; Pina et al., 2020; Sohn et al., 2014; Tejeda et al., 2021). Thus, PFC Dyn signaling is positioned to regulate local KOR-expressing neurons and KOR-expressing cells within subcortical areas, notably including the extended amygdala and midbrain (Baird et al., 2021; Pina et al., 2020).

3. Opioid Modulation of Behavior

Our understanding of opioid function in health and disease has been informed by in vivo studies dissecting the behavioral effects of separate opioid receptor systems. While all three opioid receptors modulate pain (Millan, 1990; Quirion et al., 2020; Sprouse-Blum et al., 2010), a patchwork of studies have elucidated important, yet far from isolated, roles for MOR and DOR in reward-related behaviors, DOR and KOR in affective behaviors, and KOR in responses to stress (Chung and Kieffer, 2013; Feng et al., 2012). In addition, emerging evidence suggests the opioid system regulates cognitive processing and decision-making (Abraham et al., 2021; van Steenbergen et al., 2019).

3.1. Valence and Motivated Behavior

3.1.1. Reward

Drugs targeting the MOR system carry high abuse liability compared to other exogenous opioids. The rewarding and reinforcing properties of MOR agonists have been demonstrated in several animal models. Animals will self-administer intracranial morphine and other MOR agonists into the VTA (Bozarth and Wise, 1981; Devine and Wise, 1994), and MOR activation facilitates intracranial self-stimulation (Duvauchelle et al., 1997). PFC function is critical for modulating these reward behaviors, as well as opioid’s stimulant properties assessed in rodents via locomotor activation. For example, expression of plasticity-related transcription factors in PL- and IL-PFC was associated with morphine sensitization (Kaplan et al., 2011), and bilateral mPFC lesion prevents the induction of morphine-induced locomotor sensitization (Hao et al., 2007). Furthermore, selective chemogenetic inhibition of PFC neurons that project to VTA prevented morphine-induced locomotor activation yet failed to disrupt the expression of morphine-induced place preference (Yang et al., 2020). Similarly, cell type- and site-specific knockdown of MOR within PL-PFC PV-INs dampened initial locomotor responses and sensitization following morphine (Jiang et al., 2021). Morphine-induced CPP was not affected, illustrating that loss of PV-IN PFC MOR signaling regulates opioid sensitivity but not reward-processing, similar to VTA-projecting cells.

A handful of rodent studies have linked aberrant PFC MOR signaling with a loss of inhibitory control over motivated behavior (Baldo, 2016). In a preclinical animal model relevant to binge eating, IL-PFC and OFC MOR activation evoked hyperphagia for palatable food and locomotor hyperactivity, while KOR and DOR stimulation did not (Mena et al., 2011). Conversely and consistent with this finding, mPFC MOR blockade attenuated consumption and motivation to obtain highly palatable food (Blasio et al., 2014). More recent studies using site-specific DAMGO infusions revealed that MOR regulates distinct appetitive behaviors across PFC areas. IL-PFC MOR signaling regulated sucrose intake and anticipatory behaviors, mOFC and AIC MOR signaling regulated intake but not anticipation, and localized PL-PFC and lOFC MOR stimulation had little effect on sucrose-seeking (Giacomini et al., 2021). Interestingly, recent work suggests that ovarian hormones modulate opioid-induced feeding responses, showing that stimulation of feeding behavior by intra-IL-PFC MOR activation is blunted in intact females compared to ovariectomized females and intact males (Diaz et al., 2023). In accordance with reports implicating MOR signaling in natural reward seeking, animals identified as “high drinkers” in a limited access drinking paradigm showed elevated mRNA levels of Penk and Oprm1 but not Oprd1 in the mPFC during an anticipatory period prior to ethanol access (Morganstern et al., 2012). Increased Penk expression was site-specific, where high drinkers showed dense Penk labeling in the PL-PFC. Furthermore, PL-PFC infusion of DAMGO, but not DOR agonist DALA, increased ethanol consumption, suggesting that Enk signaling through MOR promotes alcohol-seeking. Collectively, these findings raise the possibility that MOR signaling within the PL-PFC might be targeted to selectively modulate drug-seeking without affecting food-motivated behaviors. Just recently, it has been shown that fentanyl recruits frontal-projecting claustral neurons that elicit behavioral inhibition over fentanyl intake (Terem et al., 2023), providing a discrete anatomical target through which MOR signaling controls fentanyl consumption in mice.

DOR has been implicated in opioid sensitization and dependence. DOR antagonism attenuates the reinforcing effects of MOR agonists and also suppresses physiological and affective signs of withdrawal (Funada et al., 1996; Shippenberg et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 1997; Suzuki et al., 1994), implicating this system at both ends of hedonic processing. While the literature primarily ascribes these behavioral effects to signaling within subcortical structures where DOR can attenuate presynaptic dopamine release (Klenowski et al., 2015), recent findings have implicated the PFC, as DOR knockdown in PL-PFC SST-INs inhibited morphine-induced CPP and hyperlocomotion (Jiang et al., 2021).

KOR system manipulations can alter drug-seeking behavior in multiple models (reviewed in (Banks, 2020)). In general, KOR activation decreases drug-seeking and KOR inhibition has mixed effects on reward-related behavior. mPFC-directed or systemic activation of KOR prevents the development of cocaine sensitization (Chefer et al., 1999) and decreases intake of multiple drugs including ethanol, cocaine, and heroin (Glick et al., 1995; Lindholm et al., 2001). Moreover, KOR activation dose-dependently increases brain stimulation thresholds (Todtenkopf et al., 2004), suggesting that KOR signaling elevates the reward threshold for pleasurable stimuli. On the other hand, studies of KOR antagonism have yielded inconsistent findings based on drug, model of exposure, and species, as is thoroughly discussed in (Banks, 2020).

3.1.2. Aversion

In general, MORs mediate the rewarding properties of natural and drug stimuli, while DORs fill a complex regulatory role related to emotional processing, and KORs are associated with both pleasure and aversion (Darcq and Kieffer, 2018). Studies focused on PFC using site-directed pharmacology have revealed that PFC KOR signaling is necessary and sufficient for KOR-mediated conditioned place aversion (Bals-Kubik et al., 1993; Tejeda et al., 2013). Unique among opioid receptors, KOR and Dyn have been intimately associated with endogenous stress systems. Stress exposure elicits Dyn release in the mouse mPFC (Abraham et al., 2021). Repeated-swim stress increases the expression of KOR mRNA isoforms within PFC and other cortical areas (Flaisher-Grinberg et al., 2012), suggesting the KOR system responds to stress through changes in both peptide release and receptor signaling. Consistent with this idea, earlier studies demonstrated that intracerebroventricular injection of corticotropin releasing factor caused increased in KOR phosphorylation (Land et al., 2008), and pharmacological and genetic ablation of both KOR and Dyn function prevent behavioral responses associated with forced swim, social defeat, and conditioned place aversion (Land et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2006; McLaughlin et al., 2003). Similarly, bilateral intra-mPFC KOR antagonism dose-dependently reduced anxiety-like behavior in an open field assay (Tejeda et al., 2015). In addition, sustained KOR activation and arrestin signaling following repeated swim stress drives phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase within GABAergic cortical neurons (Bruchas et al., 2007). A p38 inhibitor blocked U50,488 place aversion and stress-induced immobility, providing one molecular mechanism through which KOR may regulate avoidance and affective behaviors. All three opioid receptor systems have shown antidepressant-like potential in preclinical animal models of depression that assess avoidance or escape behaviors (Berrocoso et al., 2013; Carlezon et al., 2006; Lutz and Kieffer, 2013; Peciña et al., 2019; Torregrossa et al., 2006; Vergura et al., 2008; Zomkowski et al., 2005). While PFC inhibitory circuits are important for antidepressant-like effects of other mechanisms (Ali et al., 2020; Gerhard et al., 2020), additional research is needed to test the link between PFC function and opioid system regulation of stress and affective behaviors.

3.2. Cognition

Disordered cognitive processing is a common feature of several psychiatric disorders, including SUD. A meta-analysis of observational studies revealed that chronic opioid exposure, through recreational or therapeutic use, is associated with a host of cognitive deficits related to memory, impulsivity, and cognitive flexibility (Baldacchino et al., 2012). However, due to limitations inherent to observational studies, it is not entirely clear whether these deficits emerged from pre-existing traits, chronic pain, opioid exposure, or a combination of these factors.

Several lines of evidence point towards the Dyn/KOR system as a biological substrate underlying opioid-induced alterations in cognition. Recent evidence suggests that in addition to promoting aversive behavior, KOR mediates stress-induced deficits in executive functioning. Specifically, systemic administration of NMRA-140, a KOR antagonist, prevents working memory impairments induced by the pharmacological stressor FG7142 in rhesus macaques (Wallace et al., 2022). In mice, PFC KOR activation by endogenous or artificially evoked Dyn release disrupted cognitive performance in a delayed alternation working memory task (Abraham et al., 2021). Likewise, direct site infusions of the KOR agonist U50,488 into the PFC decreased correct responses on a delayed nonmatching-to-sample task in rats (Wei et al., 2022). Chronic exposure to opioids can also precipitate long-term changes in working memory. Self-administration of the synthetic opioid remifentanil produced deficits in cognitive flexibility assessed by an operant-based attentional set-shifting task in mice (Anderson et al., 2021). Considering remifentanil’s high selectivity for MOR, an intriguing possibility is that changes in cognitive flexibility stem from crosstalk between MOR and KOR systems. To that point, naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal can increase Dyn release and facilitate KOR activation in the PFC (Abraham et al., 2021). Impaired reversal learning during prolonged withdrawal from morphine has been associated with an increase in cFos in the mPFC and decrease in the OFC (Piao et al., 2017), suggesting that cognitive deficits during opioid withdrawal emerge from dysregulated activity across cortical regions. Finally, ethanol dependence upregulated PFC KOR sensitivity and direct KOR blockade rescued associated deficits in a delayed nonmatching-to-sample task (Wei et al., 2022), highlighting the potential of the KOR system as a tangible target for counteracting drug-induced changes in cognition.

4. Opioid Modulation of PFC Circuit Function

Electrophysiology is a powerful tool for assessing opioid receptor function in cortical circuits. Used in tandem with animal models of drug exposure, we can glean insight into opioid-induced adaptations to intact neural circuits. Ex vivo stimulation of opioid receptor systems in acute slices enables direct observation of opioid regulation of PFC physiology. Below, we discuss the effects of both acute and systemic opioid exposure on PFC physiology, drawing parallels between studies when possible. It is crucial to acknowledge that we must exercise caution in doing so, keeping in mind that systemic opioid administration may modify PFC function through indirect actions on other brain networks and neurochemical systems.

4.1. Glutamate Transmission

The preponderance of available evidence indicates that presynaptic opioid signaling depresses glutamatergic release probability within neocortical areas, including the PFC. In slices from somatosensory cortex of young rats, selective pharmacological stimulation of MOR and DOR depressed stimulus-evoked EPSPs, AMPA receptor EPSCs, and NMDA receptor EPSCs (Ostermeier et al., 2000). By contrast, responses to exogenous glutamate were not affected by MOR or DOR activation, suggesting that these receptors reduce presynaptic release probability. More recent studies in young adult male mice have shown that DOR activation by the selective agonist KNT-127 dampens glutamatergic transmission onto PL-PFC pyramidal cells and decreases neuronal excitability (Yamada et al., 2021) KNT-127 also increased the paired-pulse ratio of evoked responses, pointing towards a presynaptic locus. Likewise, KOR activation in the rat mPFC decreases the frequency, but not amplitude, of miniature EPSPs, suggesting that presynaptic KORs can inhibit glutamate transmission onto L5 pyramidal cells (Tejeda et al., 2013). Recent work by Yarur et al. has built upon these findings to describe how KOR signaling selectively gates information arriving to the PFC from several limbic inputs. Dyn signaling through presynaptic KORs inhibits excitatory afferents from the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), basolateral amygdala (BLA), and the contralateral PFC (clPFC) (Yarur et al., 2022). These findings are consistent with results obtained from earlier in vivo electrophysiological recordings in which KOR signaling attenuated BLA inputs to PFC but did not modify hippocampal inputs to the PFC (Tejeda et al., 2015). The PFC afferents regulated by MOR generally contrast with those sensitive to KOR activation. Morphine administration to anesthetized rats decreased PFC pyramidal cell responses to MDT, BLA, and hippocampal stimulation (Giacchino and Henriksen, 1998). More recent studies using optogenetics and slice preparations have corroborated these findings, as MOR activation acutely inhibits MDT inputs to ACC pyramidal cells (Birdsong et al., 2019). Thus, the MDT and hippocampal inputs are sensitive to MOR activation, the PVT and clPFC inputs to KOR activation, and the BLA inputs to both. Opioid signaling is thereby positioned as a local mediator that can differentially modulate discrete inputs to PFC. Additional in vivo recordings of PFC circuit activity are necessary to confirm the validity of these observations in awake behaving animals.

Experimenter-delivered opioid exposure in vivo also alters glutamatergic synaptic strength within PFC. In the rat ACC, both acute and chronic opioid signaling decrease extracellular glutamate concentrations assessed by microdialysis (Hao et al., 2005). While opioids acutely act via presynaptic mechanisms, persistent changes in glutamate transmission may be consolidated through postsynaptic mechanisms. Acute and chronic morphine treatment decrease GluA1 surface expression in the rat PFC (Herrold et al., 2013; Mickiewicz and Napier, 2011), and decreased mEPSC amplitude on PL-PFC SST-INs and PV-INs has been observed following a single morphine injection (Jiang et al., 2021). In contrast to these reductions in synaptic strength, chronic morphine administration increased total dendritic length and complexity in PFC SST-INs and PV-INs, an effect that persisted following 7 days of abstinence (Wang et al., 2019). Jiang et al. also observed that morphine administration increased neurite complexity and length in PFC SST-INs but did not detect changes in PV-INs (Jiang et al., 2021). Viral-mediated knockdown of cortical MOR and DOR reduced basal dendritic development in SST cells of opioid-naïve mice and decreased the morphine-induced increase in SST-IN dendritic length and complexity (Wang et al., 2019), suggesting that the mechanism of opioid-induced changes to SST-IN structural plasticity involves both MORs and DORs. It is unclear whether DOR is activated by morphine at physiologically relevant concentrations or whether DOR signaling is enhanced via MOR-dependent crosstalk. Previous studies in cultured cortical neurons have shown that morphine upregulates DOR surface expression, and that this effect is blocked by a selective MOR antagonist (Cahill et al., 2001). The selective MOR agonist fentanyl also recapitulated changes to DOR surface expression, reinforcing that MOR activation is sufficient to promote DOR signaling.

Studies employing opioid self-administration have yielded mixed results regarding excitatory drive on PFC pyramidal cells. Following 2-weeks abstinence after 4-weeks self-administration of remifentanil, L5/6 PL-PFC pyramidal cells from female mice displayed reduced AMPA receptor currents (Anderson et al., 2021). In the same study, pyramidal cells from male mice displayed reduced excitability without reduced glutamate transmission, suggesting latent sex differences in the mechanisms through which long-term opioid self-administration alters PFC function in mice. By contrast, heroin self-administration in male rats has been reported to increase postsynaptic strength onto L5 Drd1+ PL-NAc projection neurons but not Drd2+ PL-NAc projection neurons (Kokane et al., 2023). These data indicate that anatomical and/or molecular variation in pyramidal cells may be critical in guiding long-term adaptations following opioid self-administration. Interestingly, in this study, cue-induced reinstatement reduced postsynaptic strength onto Drd1+ PL-NAc projection neurons. This finding is reminiscent of Van den Oever et al., who showed that synaptic AMPA receptor expression and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the PFC are reduced upon re-exposure to heroin-associated cues (Van den Oever et al., 2008). These data emphasize that additional research is required to better understand cell type-specific mechanisms underlying opioid-induced alterations to synaptic strength on pyramidal cells and whether similar or opposing changes occur on various subtypes of PFC INs.

4.2. GABA Transmission

A primary mechanism through which opioids alter cortical networks is by attenuating GABAergic transmission from local INs (Tejeda et al., 2021; Dutkiewicz and Morielli, 2020). In slices of ACC, DAMGO and DPDPE each reduced feedforward inhibitory currents evoked by thalamic stimulation on L2/3 and L5 pyramidal cells (Birdsong et al., 2019). DAMGO also reduced monosynaptic thalamic EPSCs, while DPDPE did not. By contrast, DPDPE reduced optogenetically evoked IPSCs from PV-INs onto pyramidal cells, whereas DAMGO had no effect. Together, these findings suggest that MOR and DOR attenuate thalamic feedforward inhibition in ACC through actions on glutamatergic thalamic terminals and local GABA synapses, respectively. By contrast, Lau and colleagues reported that DAMGO suppresses PV-IN-mediated IPSCs onto L2/3 pyramidal cells in the medial but not lateral OFC (Lau et al., 2020). These studies illustrate that opioid receptor modulation of GABA transmission may vary critically across frontal cortex subregions. Finally, studies using nicotinic pharmacology to stimulate putative VIP-INs implicated MOR in PFC disinhibition (Férézou et al., 2007). Importantly, these studies were performed in 14–21-day rats, so future work should leverage contemporary genetic tools to assess opioid receptor disinhibitory motifs across development and into adulthood.

Systemic opioid administration can similarly attenuate PFC inhibitory transmission onto pyramidal cells. Using a combination of electrophysiological and genetic approaches, recent work from Jiang et al. demonstrated that morphine disinhibits pyramidal cell activity in the mouse PL-PFC through dissociable cell type-specific opioid receptor signaling mechanisms (Jiang et al., 2021). The authors found that acute morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p., mice sacrificed 12 hours following dose) reduced mIPSCs onto pyramidal cells but increased mIPSCs onto PV-INs. Further studies revealed that DOR signaling in SST-INs is required for morphine to potentiate inhibitory input onto PV-INs and disinhibit pyramidal cells. By contrast, Anderson et al. observed an increase in inhibitory transmission that emerged in PL-PFC PNs from female mice following 10–16 days of self-administration of the MOR agonist remifentanil (Anderson et al., 2021). Notably, mIPSC frequency returned to levels comparable to saline treated animals following 25–30 days of remifentanil exposure, suggesting that remifentanil dynamically alters GABAergic transmission in a dose-dependent fashion. Finally, chronic morphine administration may desensitize MOR within ACC circuits. Morphine delivery for 7 days via osmotic minipump sex-dependently attenuated MOR actions on MDT-ACC feedforward inhibition (Jaeckel et al., 2023). Future studies will be needed to assess underlying cell type and molecular mechanisms.

4.3. Membrane Physiology

Opioid-induced adaptations to cell membrane physiology have been reported across the PFC in inhibitory and excitatory cell populations. In GABAergic INs, MOR stimulation generates membrane hyperpolarization, decreasing cell excitability (Madison and Nicoll, 1988; Tanaka and North, 1994). Several studies have expanded upon this finding in the rodent cortex, demonstrating that MOR signaling regulates sodium and potassium ion conductance to modulate cell excitability. For example, electrophysiological studies indicate that MOR negatively regulates sodium currents while enhancing potassium channel conductance (Férézou et al., 2007; Witkowski and Szulczyk, 2006). Additionally, recent patch-clamp experiments revealed that a subset of cultured neocortical INs, identified by mRuby2 fluorescence under the Dlx promoter, show DAMGO-induced adaptations to firing frequency and action potential kinetics that are mediated in-part by actions on voltage-gated potassium channels (Dutkiewicz and Morielli, 2020).

In accordance with its acute actions, non-contingent opioid administration in vivo generally decreases the excitability of PFC pyramidal cells. One week following repeated morphine injections, pyramidal cells in L5 of the rat IL-PFC, but not PL-PFC, exhibited decreased neuronal excitability (Qu et al., 2020). Expression of the small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channel SK3 subunit was enhanced in the mPFC, providing a potential mechanism through which prolonged morphine exposure enhances potassium conductance to decrease pyramidal cell excitability. Upregulated SK expression was accompanied by an increase in Rac1 signaling. Conversely, Rac1 inhibition disrupted SK current and increased pyramidal cell excitability, suggesting that Rac1 regulation of SK channels mediates some of morphine’s physiological effects in IL-PFC. Importantly, hyperactivity of the mPFC, indicated by an increase in cFos expression, was observed after 6 weeks but not 2 weeks of morphine withdrawal (Piao et al., 2017), indicating that adaptations to PFC cell excitability may differ across acute and protracted stages of withdrawal. An important consideration is that morphine likely alters pyramidal cell physiology in a cell type-specific manner. For example, in mouse mPFC, Type B intratelencephalic pyramidal cells, which are anatomically defined by axonal projections to other forebrain regions, showed decreased current-evoked spiking and spike amplitude following 5-days of non-contingent heroin administration (Leyrer-Jackson et al., 2021a). Heroin did not significantly impact Type A cells which target midbrain and hindbrain structures, suggesting that heroin may selectively alter connectivity between mPFC and other cortical regions. In the rat AIC, an identical heroin administration protocol decreased the excitability of NAc-projecting neurons (Leyrer-Jackson et al., 2021b), consistent with the possibility that opioids preferentially alter intratelencephalic cells across cortical regions. Additional studies are needed to test this hypothesis and characterize opioid actions in additional subpopulations of cortical pyramidal cells.

In line with opioid effects on broader neurotransmission, in vivo opioid exposure generally dampens cell excitability through multiple molecular mechanisms. Recent work from Anderson et al. offers two sex-dependent cellular mechanisms underlying the emergence of opioid-induced pyramidal cell hypoexcitability in the PL-PFC. Following 2-weeks abstinence after 4-weeks self-administration of Remifentanil, L5/6 PL pyramidal cells from male and female mice each display a hypoexcitable state. In male mice, hypoexcitability was driven by an increase in GABAB receptor function, whereas hypoexcitability in females was associated with a reduction in AMPA receptor currents (Anderson et al., 2021). In female mice, this hypoexcitable state is mirrored on a shorter timescale, following only 10–16 days of Remifentanil self-administration, while pyramidal cells from male mice show a significant decrease in rheobase and trend towards increased current-evoked spiking, reflective of increased cell intrinsic excitability. In males, this dose-dependent shift in cell excitability could, perhaps, reflect a compensatory plasticity mechanism to downregulate PFC cell excitability following prolonged drug exposure, similar to what is seen following extended cocaine exposure (Chen et al., 2013; Sun and Rebec, 2006).

5. Cortical Opioid Interactions with Neuromodulatory Systems

Opioid signaling interacts with multiple neuromodulatory systems (Table 2), the best characterized of which is the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Acute and long-lasting effects of opioid drugs on dopamine transmission have been documented in striatal and limbic regions, as well as in the PFC (Acquas and Di Chiara, 1992 Tjon, 1994 #235; Corre et al., 2018; Kokane et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2015; Nakagawa et al., 2011). In mouse cortical neurons, concomitant activation of MOR or DOR potentiated responses to the D1-like receptor agonist SKF 81297, including cAMP formation and phosphorylation of CREB and AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits (Olianas et al., 2012). Reverse dialysis of DAMGO in the rat PFC also increases dopamine overflow (Tejeda et al., 2013), although the molecular and circuit mechanisms of this phenomenon are unknown. KOR, by contrast, is positioned upstream to negatively regulate DA transmission. Using in vivo microdialysis and Cre-mediated knockout of KOR in DA neurons, Tejeda et al. have shown that intra-mPFC KOR signaling decreases extracellular DA in the mPFC via direct inhibition of DA release (Tejeda et al., 2013). In addition to presynaptic KORs that regulate DA release within PFC, KORs on the cell bodies of midbrain projection neurons can also attenuate PFC DA transmission. KOR activation induces membrane hyperpolarization and inhibits VTA neurons that project to the mPFC, and decreases mPFC DA levels (Margolis et al., 2006). In stark contrast, electrical or pharmacological stimulation of VTA MORs increases extracellular DA and DA metabolites in the ACC (Narita et al., 2010). Systemically delivered MOR agonists have shown dose-dependent effects on prefrontal DA transmission. Subcutaneously delivered 1, 3, or 5 mg/kg doses of morphine failed to alter PFC extracellular DA levels in rats (Bassareo et al., 1996), while intraperitoneal injection of 10 or 20 mg/kg morphine increased PFC dopamine and norepinephrine (NE) in mice (Ventura et al., 2005). These findings suggest complex, dose-dependent relationships between the PFC opioid and catecholamine systems.

Table 2.

Summary of opioid receptor modulation of cortical neuromodulatory systems.

| Neuromodulator | Compound | Effect | Location | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | DAMGO ⇑ MOR +DPDPE ⇑ DOR |

Potentiation of D1-like receptor signaling1 | Cortical neurons | Culture |

| DAMGO ⇑ MOR | Increased DA release/DA metabolites2 | ACC | Rat | |

| Increased DA3 | PFC | Rat | ||

| Morphine ⇑ MOR (10, 20 mg/kg, i.p.) (1, 3, 5 mg/kg, s.c.) |

PFC | Mouse | ||

| Increased DA release5 | PFC | Rat | ||

| No effect on extracellular DA6 | ||||

| U69,593 ⇑ KOR | Decreased extracellular DA3 | PFC | Rat, mouse | |

| Decreased extracellular DA4 | PFC | Rat | ||

| No effect on D1-like receptor signaling1 | Cortical neurons | Culture | ||

| Nor-BNI ⇓ KOR | Increased DA release3 | PFC | Rat | |

| Serotonin | DAMGO ⇑ MOR | Decreased 5HT-evoked EPSCs7 | PFC | Rat |

| Endomorphin-1 ⇑ MOR | Decreased 5HT-evoked EPSCs7 | PFC | Rat | |

| Met-enkephalin ⇑ MOR | Decreased 5HT-evoked EPSCs7 | PFC | Rat | |

| DPDPE ⇑ DOR | No effect on 5HT-evoked EPSCs7 | PFC | Rat | |

| U50,488 ⇑ KOR | No effect on 5HT-evoked EPSCs7 | PFC | Rat | |

| Norepinephrine | DAMGO ⇑ MOR | Decreased NE-evoked EPSCs8 | PFC | Rat |

| Increased delta and alpha power9 | PFC | Rat |

Data obtained from: (Olianas et al., 2012)1; (Narita et al., 2010)2; (Tejeda et al., 2013)3; (Margolis et al., 2006)4; (Ventura et al., 2005)5; (Bassareo et al., 1996)6; (Marek and Aghajanian, 1998)7; (Marek and Aghajanian, 1999)8; (Guajardo & Valentino, 2021)9.

A small, yet growing, body of literature has implicated several other monoaminergic systems in the central actions of opioid drugs. MOR is frequently co-expressed with choline acetyltransferase in neurons from rat frontoparietal cortex (Taki et al., 2000), where MOR and KOR agonists have been shown to negatively regulate acetylcholine transmission (Lapchak et al., 1989). Similarly, MOR activation attenuates 5-HT transmission in PFC (Marek and Aghajanian, 1998). NE transmission in the mPFC appears to play a critical role in morphine-induced mesoaccumbal DA transmission and morphine-related behavior. Selective depletion of PFC NE prevented morphine-induced DA release in the NAc following a morphine challenge and blocked the expression of morphine-induced CPP (Ventura et al., 2005). MOR activation in PFC slices of male rats strongly suppressed NE-induced EPSCs onto L5 pyramidal cells (Marek and Aghajanian, 1999). Considering NE-induced EPSCs are mediated by α1 adrenergic receptors (Marek and Aghajanian, 1998; Marek and Aghajanian, 1999), MOR and α1 receptors may co-localize at glutamatergic afferents and exert opposing actions through Gi/o and Gq signaling, respectively. Though speculative, Marek and Aghajanian propose the thalamus as a potential site for these afferents, as Oprm1 mRNA and mRNA encoding for multiple adrenoreceptor subtypes have been observed in thalamus. The PFC receives primary NE projections from the locus coeruleus (LC), and MOR within the cell bodies of locus coeruleus neurons can also shape PFC function. In freely behaving rats, locus coeruleus MOR activation increased delta and alpha power in mPFC (Guajardo and Valentino, 2021). These effects were observed in male but not female rats, consistent with sexually divergent patterns of MOR mRNA and protein expression in the locus coeruleus (Guajardo et al., 2017). The density of α2 receptors is decreased in the frontal cortex of OUD patients that had detectable levels of morphine in their system at time of death (Gabilondo et al., 1994), suggesting that adrenoreceptor desensitization might also occur as a functional consequence of MOR signaling.

7. Evidence Linking the Cortical Opioid System with Psychiatric Disorders

Dysfunction of the opioid system has been proposed in biological hypotheses related to disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and addiction (Bandelow et al., 2010; New and Stanley, 2010; Puryear et al., 2020; Schmauss and Emrich, 1985; Trigo et al., 2010). As described below, postmortem observations and scattered reports of symptom relief with opioid drugs, provide preliminary construct validity and excitement for the development of novel opioid-based treatments for psychiatric diseases.

A role for aberrant opioid signaling in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia was first proposed in the 1980s based on a series of studies demonstrating elevated opioid peptide expression in schizophrenia patients (Brambilla et al., 1984; Lindström et al., 1986; Wiegant et al., 1988). Additionally, several studies have shown rapid and efficacious treatment of positive and negative symptoms with nonspecific opioid receptor antagonists, as well as buprenorphine, a MOR partial agonist and KOR antagonist (reviewed in Clark, 2019 #174). KOR activation is psychotomimetic in healthy individuals (Pfeiffer et al., 1986), suggesting that Dyn/KOR signaling may promote positive symptoms in some individuals with schizophrenia. However, definitive evidence for pathological Dyn/KOR expression in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia is limited. While elevated Dyn has been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with schizophrenia (Heikkilä et al., 1990), in-situ hybridization of PFC and ACC tissue from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and MDD patients showed no differences in PDYN or OPRK1 mRNA levels (Peckys and Hurd, 2001). Altered MOR function has also been identified in a recent PET study finding reduced MOR availability in OFC and cingulate cortex in subjects with schizophrenia (Ashok et al., 2019). Studies examining MOR function in the context of MDD raise the possibility that these changes may be related to negative affective symptoms.

Substantial preclinical evidence, thoroughly reviewed by (Peciña et al., 2019), identifies endogenous opioid signaling as a therapeutic target in the treatment of MDD. Both depression and anxiety are associated with reductions in MOR availability in OFC and cingulate cortex (Nummenmaa et al., 2020). Notably, MOR density and mRNA is increased in the frontal cortex of patients that died by suicide and had a history of depression (Escribá et al., 2004; Gabilondo et al., 1995; Gross-Isseroff et al., 1990), though it is impossible to disentangle effects of suicide/suicidality from MDD from those results alone. In neurotypical female subjects, induction of a sustained sadness state increased [C11]carfentanil binding within the rostral ACC, suggesting that sadness can decrease Enk/endorphin tone in this region (Kennedy et al., 2006; Zubieta et al., 2003). By contrast, female patients with treatment-resistant MDD displayed a decrease in MOR binding potential during sadness (Kennedy et al., 2006). These findings suggest that MDD is associated with major differences in PFC opioid responses to mood and emotional experiences. Other studies in neurotypical subjects have revealed that ACC KOR binding potential is inversely correlated with an index of social status based on education and occupation of individuals and their close relatives (Matuskey et al., 2019), suggesting that KOR may contribute to depression by mediating negative emotional states associated with environmental stressors, consistent with findings from animal models. Buprenorphine, which has dual activity at MOR and KOR, has emerged as a potential antidepressant agent. At doses subthreshold to euphoric responses, numerous studies have demonstrated significant improvement in symptoms of treatment-resistant depression (Peciña et al., 2019), suggesting that buprenorphine may dampen KOR-mediated negative affect and activate MOR-mediated hedonic processing. Considering the extensive preclinical literature linking changes in PFC transmission with rapid antidepressant-like responses, it is tempting to speculate that antidepressant actions of buprenorphine may be mediated, at least in part, by actions within PFC.

In contrast to depression and schizophrenia, repeated drug use is generally associated with an upregulation in opioid receptor availability in the frontal cortex. Observations of upregulated MOR signaling following drug administration in animals (Morganstern et al., 2012; Unterwald et al., 1994) suggest that enhanced MOR activity promotes drug-seeking behavior. Consistent with this idea, increased MOR binding in the cortex positively correlated with craving intensity in men who met the DSM-III criteria for cocaine dependence (Zubieta et al., 1996). Genetic variations in OPRK1 and PDYN are associated with increased risk for alcohol dependence (Xuei et al., 2006), and changes in PDYN mRNA (Bazov et al., 2013; Bazov et al., 2018) and KOR availability (Vijay et al., 2018) have been reported in the frontal cortex of individuals with AUD. The effects of naltrexone, an approved therapeutic for AUD, have been correlated with reduced KOR availability in the PFC and cingulate (de Laat et al., 2019). Further, altered levels of PDYN mRNA have been associated with recent stimulant use and a lifelong history of marijuana use (Peckys and Hurd, 2001). Thus, there is significant construct validity for targeting the cortical KOR system as a novel treatment for AUD and other addictive disorders.

8. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

In this review, we have summarized what is known regarding the basic biology and function of the cortical opioid system. Endogenous opioid receptors and peptides are embedded within cortical circuits and have been causally linked with motivational and affective phenotypes throughout an extensive preclinical literature. Further, we have outlined evidence for altered opioid transmission in psychiatric diseases in human studies, building a compelling case for cortical opioid signaling as a promising therapeutic target. While the MOR system has traditionally been the main target of clinically used opioids for the treatment of pain, we describe therapeutic potential for all three classical receptor systems across several additional symptom domains. Though multiple receptor systems often converge to regulate similar facets of behavior, MORs have emerged as an attractive target for the treatment of SUDs whereas KORs and DORs may be leveraged to develop breakthrough treatments for stress-related and affective disorders.

Current opioid-based medications are plagued by several deleterious side effects ranging from physical discomfort caused by constipation, nausea, and vomiting, to physical dependence, tolerance, and respiratory depression and death in severe cases (Edinoff et al., 2021). The escalating opioid crisis has initiated a race towards developing safer and more effective alternatives. One promising avenue of research involves leveraging biased signaling at opioid receptors. This concept of biased agonism, also known as functional selectivity, refers to the ability of particular ligands to preferentially direct receptor signaling towards certain intracellular pathways (Azzam et al., 2019). In recent years, a surge of research has focused on the development of biased MOR agonists with the goal of promoting therapeutic effects (primarily analgesia) while avoiding adverse side effects. Considering KOR activation produces several negative effects such as dysphoria, psychotomimetic effects, and anhedonia (Cahill et al., 2021), biased KOR agonism has also been proposed for the treatment of pain and mood disorders (Dogra and Yadav, 2015). Allosteric modulators of opioid receptors have received significant attention as safer therapeutic options, appearing amongst NIDA’s top ten “medication development priorities” in response to the opioid crisis (Rasmussen et al., 2019). Allosteric compounds modulate GPCR activity through actions distal to the orthosteric ligand-binding site. A series of MOR potentiators have already been developed that enhance the antinociceptive effects of orthosteric MOR agonists in preclinical studies (Kandasamy et al., 2021; Pryce et al., 2021). Overall, rapid advancements in pharmacology and drug development have been transformative for the evolution of opioid-based medications towards increased safety, selectivity, and efficacy. While precise targeting of cell-types and circuits remains a challenge, ongoing research efforts focused on innovative drug delivery methods show great promise for targeted brain interventions. In the meantime, a basic understanding of endogenous opioid function in healthy and diseased states will be essential for informing novel treatment approaches and targets.

Highlights.

Opioid signaling in prefrontal cortex is understudied relative to subcortical areas

PFC opioid receptors are enriched within diverse types of inhibitory interneurons

Exogenous opiates induce acute and long-term changes in PFC synaptic transmission

Changes in opioid peptides and receptors are observed in psychiatric diseases

Funding and Declaration of Interest

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R00AA027806 amd R00DA048085], the Whitehall Foundation [grant number 2022-08-005], and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. RHC was supported by the Center for Neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham AD, Casello SM, Schattauer SS, Wong BA, Mizuno GO, Mahe K, Tian L, Land BB, Chavkin C, 2021. Release of endogenous dynorphin opioids in the prefrontal cortex disrupts cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 2330–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acquas E, Di Chiara G, 1992. Depression of mesolimbic dopamine transmission and sensitization to morphine during opiate abstinence. Journal of neurochemistry 58, 1620–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F, Gerhard DM, Sweasy K, Pothula S, Pittenger C, Duman RS, Kwan AC, 2020. Ketamine disinhibits dendrites and enhances calcium signals in prefrontal dendritic spines. Nature communications 11, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida JR, Akkal D, Hassel S, Travis MJ, Banihashemi L, Kerr N, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML, 2009. Reduced gray matter volume in ventral prefrontal cortex but not amygdala in bipolar disorder: significant effects of gender and trait anxiety. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 171, 54–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiades PG, Carter AG, 2021. Circuit organization of the rodent medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in neurosciences 44, 550–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancelin M-L, Carrière I, Artero S, Maller J, Meslin C, Ritchie K, Ryan J, Chaudieu I, 2019. Lifetime major depression and grey-matter volume. Journal of psychiatry and neuroscience 44, 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EM, Engelhardt A, Demis S, Porath E, Hearing MC, 2021. Remifentanil self-administration in mice promotes sex-specific prefrontal cortex dysfunction underlying deficits in cognitive flexibility. Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 1734–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, Hunt SC, Vander Stoep A, Pribram KH, 1976. Object permanency and delayed response as spatial context in monkeys with frontal lesions. Neuropsychologia 14, 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Poce F, Martıínez-Fernández E, Márquez-Espinós C, Pérez A, Mora R, Torres L, 2002. History of opium. International Congress Series. Elsevier, pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok AH, Myers J, Reis Marques T, Rabiner EA, Howes OD, 2019. Reduced mu opioid receptor availability in schizophrenia revealed with [11C]-carfentanil positron emission tomographic Imaging. Nature communications 10, 4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam AA, McDonald J, Lambert DG, 2019. Hot topics in opioid pharmacology: mixed and biased opioids. British journal of anaesthesia 122, e136–e145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird MA, Hsu TY, Wang R, Juarez B, Zweifel LS, 2021. κ opioid receptor-dynorphin signaling in the central amygdala regulates conditioned threat discrimination and anxiety. eneuro 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacchino A, Balfour D, Passetti F, Humphris G, Matthews K, 2012. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic opioid use: a quantitative review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 36, 2056–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, 2016. Prefrontal cortical opioids and dysregulated motivation: a network hypothesis. Trends in neurosciences 39, 366–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bals-Kubik R, Ableitner A, Herz A, Shippenberg TS, 1993. Neuroanatomical sites mediating the motivational effects of opioids as mapped by the conditioned place preference paradigm in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 264, 489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Schmahl C, Falkai P, Wedekind D, 2010. Borderline personality disorder: a dysregulation of the endogenous opioid system? Psychological review 117, 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, 2020. The rise and fall of kappa-opioid receptors in drug abuse research. Substance Use Disorders: From Etiology to Treatment, 147–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassareo V, Tanda G, Petromilli P, Giua C, Di Chiara G, 1996. Non-psychostimulant drugs of abuse and anxiogenic drugs activate with differential selectivity dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens and in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Psychopharmacology 124, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazov I, Kononenko O, Watanabe H, Kuntić V, Sarkisyan D, Taqi MM, Hussain MZ, Nyberg F, Yakovleva T, Bakalkin G, 2013. The endogenous opioid system in human alcoholics: molecular adaptations in brain areas involved in cognitive control of addiction. Addiction Biology 18, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazov I, Sarkisyan D, Kononenko O, Watanabe H, Karpyak VM, Yakovleva T, Bakalkin G, 2018. Downregulation of the neuronal opioid gene expression concomitantly with neuronal decline in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of human alcoholics. Translational psychiatry 8, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein H-G, Henning H, Seliger N, Baumann B, Bogerts B, 1996. Remarkable β-endorphinergic innervation of human cerebral cortex as revealed by immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience letters 215, 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocoso E, Ikeda K, Sora I, Uhl GR, Sánchez-Blázquez P, Mico JA, 2013. Active behaviours produced by antidepressants and opioids in the mouse tail suspension test. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 16, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigoni R, Rizzi A, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Regoli D, 2000. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor ligands. Peptides 21, 935–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong WT, Jongbloets BC, Engeln KA, Wang D, Scherrer G, Mao T, 2019. Synapse-specific opioid modulation of thalamo-cortico-striatal circuits. Elife 8, e45146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasio A, Steardo L, Sabino V, Cottone P, 2014. Opioid system in the medial prefrontal cortex mediates binge-like eating. Addiction Biology 19, 652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA, 1981. Intracranial self-administration of morphine into the ventral tegmental area in rats. Life sciences 28, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla F, Facchinetti F, Petraglia F, Vanzulli L, Genazzani A, 1984. Secretion pattern of endogenous opioids in chronic schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry 141, 1183–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VJ, Bowman EM, 2002. Rodent models of prefrontal cortical function. Trends in neurosciences 25, 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Land BB, Aita M, Xu M, Barot SK, Li S, Chavkin C, 2007. Stress-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation mediates κ-opioid-dependent dysphoria. Journal of Neuroscience 27, 11614–11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill C, Tejeda HA, Spetea M, Chen C, Liu-Chen L-Y, 2021. Fundamentals of the dynorphins/kappa opioid receptor system: From distribution to signaling and function. The Kappa Opioid Receptor. Springer, pp. 3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill CM, Morinville A, Lee M-C, Vincent J-P, Collier B, Beaudet A, 2001. Prolonged morphine treatment targets δ opioid receptors to neuronal plasma membranes and enhances δ-mediated antinociception. Journal of Neuroscience 21, 7598–7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli C, Radogna A, Bolcato V, Moretti M, Vignali C, Merli D, Morini L, 2022. Old and new synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids analysis in hair: A review. Talanta Open 5, 100108. [Google Scholar]

- Carlén M, 2017. What constitutes the prefrontal cortex? Science 358, 478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Beguin C, DiNieri JA, Baumann MH, Richards MR, Todtenkopf MS, Rothman RB, Ma Z, Lee DY-W, Cohen BM, 2006. Depressive-like effects of the κ-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 316, 440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casello SM, Flores RJ, Yarur HE, Wang H, Awanyai M, Arenivar MA, Jaime-Lara RB, Bravo-Rivera H, Tejeda HA, 2022. Neuropeptide system regulation of prefrontal cortex circuitry: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Neural Circuits 16, 796443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceceli AO, King SG, McClain N, Alia-Klein N, Goldstein RZ, 2023. The neural signature of impaired inhibitory control in individuals with heroin use disorder. Journal of Neuroscience 43, 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CF J, 1936. Studies of cerebral function in primate. I. The functions of the frontal association areas in monkeys. Comp Psychol Monog 13, 1–60. [Google Scholar]