Abstract

Context:

As Muslim populations in non-Muslim majority nations grow and age, they will increasingly require culturally appropriate healthcare. Delivering such care requires understanding their experiences with, as well as preferences regarding, end-of-life healthcare.

Objectives:

To examine the experiences, needs, and challenges of Muslim patients and caregivers with end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care.

Methods:

A systematic literature review using five databases (MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, Cochrane Library) and key terms related to Islam and end-of-life healthcare. Papers were limited to English-language empirical studies of adults in non-Muslim majority nations. After removing duplicates, titles, abstracts, and articles were screened for quality and reviewed by a multidisciplinary team.

Results:

From an initial list of 1867 articles, 29 articles met all inclusion criteria. Most studies focused on end-of-life healthcare not related to palliative or hospice services and examined Muslim patient and caregiver experiences rather than their needs or challenges. Content analysis revealed three themes: (i) the role of family in caregiving as a moral duty and as surrogate communicators; (ii) gaps in knowledge among providers related to Muslim needs and gaps in patient/family knowledge about advance care planning; and (iii) the influence of Islam on Muslim physicians’ perspectives and practices.

Conclusion:

There is scant research on Muslim patients’ and caregivers’ engagement with end-of-life healthcare in non-Muslim majority nations. Existing research documents knowledge gaps impeding both Muslim patient engagement with end-of-life care and the delivery of culturally appropriate healthcare.

Keywords: Islam, community health, minority health, dying, death

Muslims are the world’s fastest-growing religious community, representing over a quarter of the world’s eight billion persons (1). While most (75%) live in Muslim-majority nations, the population in non-Muslim majority nations is large and growing. Illustratively, Muslims comprise more than 10% of the population of 10 European nations (2). Relatedly, there are 3–5 million Muslims in the United States, and the population is projected to double by 2050 (3). As with any majority immigrant community, the number of Muslim older adults is expected to rise with the natural aging of the native-born and migrant population and an increased number of elderly individuals from abroad emigrating to be near family.

As the Muslim population ages, chronic disease morbidity and mortality impact health and wellness and underscores the need for specialized healthcare services such as palliative and hospice care. In Muslim-majority countries, especially in low- and middle-income countries, there are few palliative care programs and even fewer hospice care programs (2, 4, 5). Within non-Muslim majority nations, culturally tailored end-of-life care programs are also scarce. Hence, Muslims, in general, may lack awareness about specialized end-of-life healthcare services, and the perceived cultural acceptability of such models of healthcare delivery may be low.

Notwithstanding the racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic diversity among Muslim populations, a growing body of literature demonstrates that the Muslim community’s health and healthcare-seeking behaviors are strongly, and similarly, shaped by their religious beliefs and values (6, 7). For example, Islamic beliefs inform conceptions of health, healing, illness, and cure (8, 9), and Islamic law and ethics influence choices regarding treatment options (10). Accordingly, there is ample evidence to suggest that religious beliefs and values may inform how Muslims engage with end-of-life healthcare services. Hence, studying Muslim experiences in this area of healthcare can assist in addressing unmet needs and challenges and inform the tailoring of services to their held values.

Assessing Muslim engagement with end-of-life healthcare is doubly important because of the potential healthcare inequities. In the United States, for example, Muslims appear to underutilize hospice services (11). Research further suggests that Muslim Americans lack knowledge about palliative and hospice programs (12), have concerns about religious discrimination and lack of religious accommodations within these programs (12, 13), face financial barriers in accessing specialized end-of-life healthcare (14), and may have ethical concerns with extant healthcare delivery models (5, 15). Muslims are also generally under-represented in end-of-life healthcare research (16).

Hence this systematic literature review appraises the state of the healthcare research literature on the question, “What are the experiences, needs, and challenges of Muslim patients and caregivers within non-Muslim majority nations with regard to end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care?” While scholars have conducted systematic literature reviews assessing end-of-life healthcare through the lens of religion (17–19), on studies conducted in one country (e.g., Iran (20); United Kingdom (21)), and on end-of-life care issues faced by Muslim patients in Muslim-majority countries (22, 23), there has been no systematic review, to our knowledge, addressing the aforementioned focus question.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to organize this systematic review (24). Studies were included if they were empirical (either quantitative or qualitative), conducted in high-income, non-Muslim majority nations, focused on adults (18 years or older), and published in English. The list of high-income, non-Muslim majority countries was derived from the World Bank’s list of high-income countries (25) and information from the Pew Research Center regarding the percentage of population by religion (1) [see Appendix A for a list of countries eligible for inclusion in this review]. This review was not registered.

Five bibliographic databases containing health research studies were searched (Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library) in March 2022. MeSH headers and exploded terms were used to uncover pertinent articles. The general search string covered two areas: (1) Islam or Muslims, and (2) terms related to end-of-life, hospice, or palliative care [See Appendix B for greater details]. In this review, “end-of-life” refers to end-of-life care without specific reference to specialized hospice or palliative care services.

Duplicates were removed from this initial list of retrieved papers before title and abstract review, which was conducted by four members of the research team. Two members reviewed each record for relevance to the research question independently. After removing studies that did not meet inclusion criteria or were irrelevant, full-text review of each article was performed by two team members independently. For both title and abstract review, as well as full-text review, any discrepancies on whether a paper met inclusion criteria or was relevant were resolved by team consensus. Rayyan software was used to facilitate the review (26).

The team used the Qualsyst rubric for quality assessment (27). Each article was rated independently by two team members; if there was a large discrepancy in the scores given to an article by the original two reviewers, two further team members rated the article. The scores for each article were averaged; only high-quality studies (i.e., those with an average score of 0.75 or higher (23)) were included in the final review.

Data abstraction from the final slate of included papers was performed by two members of the research team. They gathered information on the location of study, research design (quantitative or qualitative), population studied, the age range of participants, sample size, percentage of males/females, end-of-life healthcare topic studied (end-of-life, hospice, palliative), as well as the healthcare domain that the findings spoke to (28). We used domains from the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care practice guidelines. These categories refer to the (1) structure and processes of care, (2) physical aspects of care, (3) psychological and psychiatric aspects of care, (4) social aspects of care, (5) spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care, (6) cultural aspects of care, (7) care of the patient nearing the end of life, and (8) ethical and legal aspects of care. Additional notes about the paper’s findings and how Islam/religion was discussed within the paper were also captured in the data collection spreadsheets and informed qualitative thematic content analysis (described below).

To synthesize the studies quantitatively, the articles were categorized in four different ways. First, the articles were categorized by whether patients or caregivers were studied. Caregivers included family as well as healthcare professionals (HCPs) such as physicians, chaplains, nurses, and social workers. Second, the articles were categorized by whether they principally examined healthcare experiences, needs, or challenges (see Table 1 for definitions). Third, they were categorized according to whether the research examined general end-of-life healthcare (i.e., not including hospice or palliative care services), hospice care, or palliative care. Fourth, the articles were categorized by healthcare domain from the NCP guidelines. Importantly, a study could belong to multiple categories within each division (e.g., it could describe experiences and needs with regard to hospice and palliative care and cover providers and patients).

Table 1:

Definitions of experiences, needs, challenges, and other.

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Experiences | The accounts of individuals and groups in healthcare settings, including the involvement and participation with the healthcare system from both patient and healthcare provider perspectives. |

| Needs | The wants and requirements for healthcare practices and healthcare resources disclosed by study participants; they could be from the patient or the healthcare provider perspective. |

| Challenges | Specific barriers that participants faced regarding end-of-life healthcare; for example, a patient might find it difficult to access end-of-life healthcare, a health care provider may be unsure how to meet patient needs, or both parties might face challenges with communication and understanding. |

| Other | Attitudes and beliefs of individuals and groups outside of the healthcare setting; these attitudes included the opinions that society—outside of current patients and healthcare providers—has about end-of-life healthcare |

The research team developed qualitative findings by analyzing repeated themes contained within the results, findings, and discussion sections of the studies (29) in a team-based manner. Each article was read independently by two team members, and these reviewers noted how the findings related to the core research question. These main ideas (codes) were discussed at team meetings as each reviewer summarized the articles along with their main ideas by referencing the papers’ results and discussion sections. The presentations were followed by team discussions to derive generalizable themes across the set of articles by grouping these ideas into higher-order salient themes. Team-based consensus building was used to resolve any differences in article ideas and themes.

Results

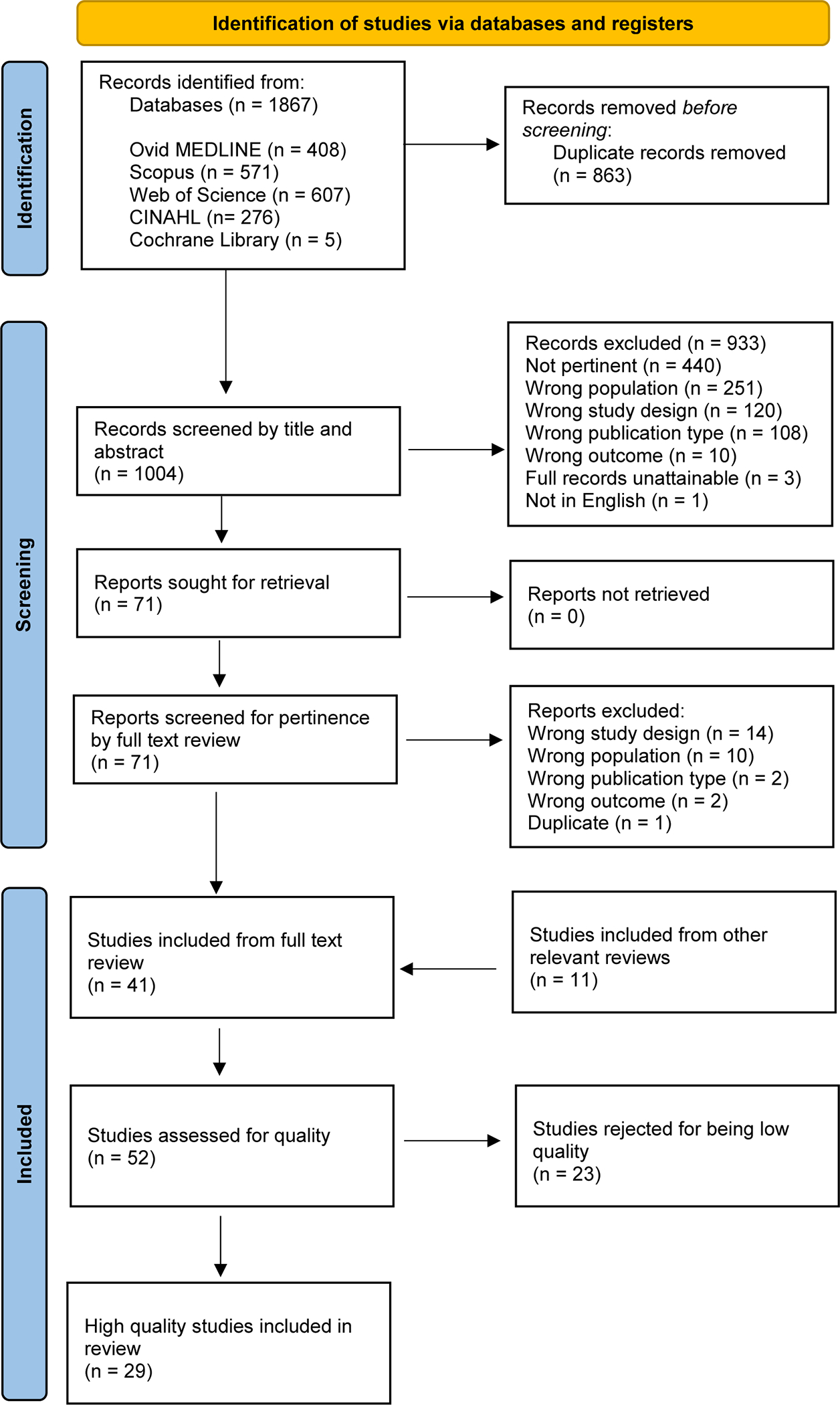

A total of 1867 articles were identified by the database searches, of which 1004 were unique articles. Based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 933 articles were excluded, and 71 full-text articles were retained for review. After reviewing these articles for pertinence to our study question, a further 30 were excluded. An additional 11 articles were retrieved from a hand search of the bibliography of related systematic reviews (17, 18, 21, 30–32), leading to a total of 52 articles in our review. Of these, 29 were assessed to be of high quality, and our findings build up from these articles [See Figure 1 for flowchart and Table 2 for the final articles; quality ratings are in Appendix C].

Figure 1:

Flowchart of article selection.

Table 2:

Articles included in the systematic review.

| Citation | Location | Research Design | Population | Patients or Caregivers | Care Type | Care Domain | Experience, Need, or Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Ahaddour, Van den Branden, & Broeckaert (40) | Belgium | Qualitative (interviews) | Middle-aged/elderly Moroccan Muslim women (n = 30) | Patients | EOL | Spiritual, Ethical | Other |

| Ahaddour, Van den Branden, & Broeckaert (55) | Belgium | Qualitative (interviews) | Middle-aged/elderly Moroccan Muslim women (n = 30) | Patients | EOL | Spiritual, Care of Patient | Other |

| Ashana et al. (42) | United States | Qualitative (interviews) | Clinicians (n = 74); female: n = 36, male: n = 30 | Patients, Caregivers | EOL | Structure, Spiritual, Cultural, Ethical | Challenges |

| Baeke, Wils, & Broeckaert (41) | Belgium | Qualitative (interviews) | Muslim women from Morocco or Turkey (n = 30) | Patients | EOL | Spiritual | Other |

| Bani Melhem et al. (44) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim adults in the community (n = 148); female: n = 62, male: n = 85 | Patients | EOL | Ethical | Challenges, Other |

| Bani Melhem et al. (45) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim adults in the community (n = 148); female: n = 62, male: n = 85 | Patients | EOL | Ethical | Challenges, Other |

| Curlin et al. (56) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Physicians (n = 1144); female: n = 300, male: n = 842 | Caregivers | EOL | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| de Graaff et al. (34) | Netherlands | Qualitative (interviews) | Cancer patients with Turkish or Moroccan background (n = 33); family members (n = 30); care providers (n = 47) | Patients, Caregivers | Palliative | Structure, Cultural | Experiences, Needs |

| Duffy et al. (12) | United States | Qualitative (focus groups); quantitative (survey) | Adults 50 and over (n = 73); female: n = 39, male: n = 34 | Patients | EOL | Cultural | Other |

| Duivenbode, Hall, & Padela (48) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim physicians (n = 255); female: n = 74, male: n = 172 | Caregivers | EOL | Ethical | Experiences |

| Gaveras et al. (57) | Scotland | Qualitative (interviews) | South Asian Muslim patients with a life-limiting illness and children under 18 (n = 8); caregivers (n = 6); healthcare professionals | Patients, Caregivers | EOL, Palliative | Social | Experiences |

| Hamouda, Emanuel, & Padela (47) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim physicians (n = 255); female: n = 74, male: n = 172 | Caregivers | EOL | Spiritual, Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Ho et al. (58) | Singapore | Quantitative (data from EMRs) | Patients admitted to home hospice (n = 25,065); female: n = 13,198, male: n = 11,863l | Patients | Hospice | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Hong et al. (59) | Singapore | Quantitative (data from cancer registry) | Deceased cancer patients (n = 52,120); female: n = 23,133, male: n = 28,987 | Patients | EOL | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Kristiansen et al. (38) | Scotland | Qualitative (interviews) | South Asian Muslims and Sikhs with life-limited illnesses (n = 25); family members (n = 15), healthcare professionals (n = 20) | Caregivers | EOL, Palliative | Spiritual | Experiences |

| Lewis, Kitamura, & Padela (54) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim allied healthcare professionals (n = 92); female: n = 56, male: n = 36 | Caregivers | EOL | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Moale et al. (43) | United States | Quantitative (pre-/post-test) | Clinicians (n = 73) | Caregivers | EOL | Structure | Other |

| Muishout et al. (51) | Netherlands | Qualitative (interviews) | Muslim physicians (n = 10); female: n = 2, male: n = 8 | Caregivers | EOL, Palliative | Physical, Spiritual | Experiences |

| Muishout et al. (50) | Netherlands | Qualitative (interviews) | Muslim physicians (n = 10); female: n = 2, male: n = 8 | Caregivers | EOL, Palliative | Physical, Ethical | Experiences |

| Nayfeh et al. (60) | Canada | Quantitative (survey) | Family members of recently deceased patients (n = 1,543) | Patients | EOL | Structure | Challenges |

| Popal, Hall, & Padela (53) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim physicians (n = 255); female: n = 74, male: n = 172 | Caregivers | EOL | Ethical | Experiences |

| Saeed et al. (52) | United States, United Kingdom, Muslim countries | Quantitative (survey) | Muslim physicians (n = 461); female: n = 116, male: n = 345 | Caregivers | EOL | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Sprung et al. (33) | 17 European countries | Quantitative | Adult patients admitted to ICU who died or had limitations on life-saving interventions (n = 3,086) | Patients, Caregivers | EOL | Care of Patient, Ethical | Experiences |

| Tay, Mohamad Zam, & Cheng (37) | Singapore | Quantitative (survey) | Patients or hospital visitors (n = 300); female: n = 86, male: n = 185 | Patients | Palliative | Structure | Needs |

| Venkatasalu, Arthur, & Seymour (35) | United Kingdom | Qualitative (focus groups and interviews) | Older South Asians (n = 55); female: n = 31, male: n = 24 | Patients | EOL | Care of Patient | Other |

| Venkatasalu, Seymour, & Arthur (36) | United Kingdom | Qualitative (focus groups and interviews) | Older South Asians (n = 55); female: n = 31, male: n = 24 | Patients | EOL | Social, Spiritual, Cultural | Needs |

| Wesley, Tunney, & Duncan (46) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Social workers (n = 62); female: n = 55, male: n = 7 | Caregivers | Hospice | Care of Patient | Experiences, Needs |

| Wolenberg et al. (49) | United States | Quantitative (survey) | Physicians (n = 1,156); female: n = 400, male: n = 756 | Caregivers | EOL | Care of Patient | Experiences |

| Worth et al. (39) | Scotland | Qualitative (interviews) | South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life-limiting illness (n = 25); family carers (n = 18); healthcare professionals (n = 20) | Patients | EOL, Hospice, Palliative | Structure, Spiritual, Cultural, Care of Patient, Social | Challenges |

Structure = Structure and processes of care; Physical = Physical aspects of care; Psychological = Psychological and psychiatric aspects of care; Social = Social aspects of care; Spiritual = Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care; Cultural = Cultural aspects of care; Care of patients = Care of patients nearing the end of life; Ethical = Ethical and legal aspects of care

The 29 articles were published between 2004 and 2022, and 17 were quantitative studies while 13 were qualitative investigations. The studies were conducted in six countries: United States (n = 14), United Kingdom (n = 6), Belgium (n = 3), the Netherlands (n = 3), Singapore (n = 3), and Canada (n = 1). One study took place in 17 unspecified European countries (33).

Quantitative Results

Among the 29 articles, 17 articles studied patients, and 16 articles studied caregivers. Among the articles that studied patients, most focused on general end-of-life healthcare excluding palliative and hospice services (n = 14), followed by palliative care (n = 4) and hospice care (n = 2). In this group of patient-focused studies, experiences (n = 5) and challenges (n = 5) were more studied than needs (n = 3). Among the articles that studied caregivers, the focus of most articles was similarly on general end-of-life healthcare (n = 13), followed by palliative care (n = 5) and hospice care (n = 1). Again, caregiver experiences (n = 13) were more studied than needs (n = 2) or challenges (n = 1).

Concerning the domain of healthcare, the greatest number of articles were categorized under the domain of care of patients nearing the end of life (n = 10), spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care (n = 8), and ethical and legal aspects of care (n = 8). The least studied domains were physical aspects of care (n = 2) and psychological and psychiatric aspects of care (n = 0). More information about the above categorizations of the articles included in this systematic review can be seen in Appendices D–F.

Qualitative Results

Three main themes, with several subthemes, emerged from reviewing individual study findings. These themes are presented below through recourse to data contained within the individual studies [see Table 3 for a list of themes and subthemes].

Table 3:

Themes and subthemes

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| The family’s role | Familial caregiving as a moral duty The family as surrogate communicators and protectors of hope |

| Lack of knowledge | Lack of provider knowledge and comfort surrounding religious dimensions of end-of-life healthcare Lack of patient and family knowledge on the role of palliative care and/or advance care planning Lack of educational resources to facilitate Muslim engagement with palliative care |

| Muslim physician perspectives and practices | The influence of provider religiosity on healthcare delivery Variability among Muslim physician practices in end-of-life healthcare |

The Family’s Role

The first theme revolves around the role of family in end-of-life healthcare with two subthemes: (i) familial caregiving as a moral duty, and (ii) the family as surrogate communicators and conveyors of hope.

Familial Caregiving as a Moral Duty.

Caregiving of relatives at the end of life was often voiced as a familial obligation (12, 34–36). The term “family” was not restricted to one’s nuclear family; rather it could cover one’s neighbors or local religious community (12, 34). Indeed, in a qualitative study of various racial/ethnic groups in Michigan, Arab Muslim participants expressed that one should be cared for by one’s family when close to death (12).

High-quality care was envisaged to have family involvement, as voiced by a participant in a study of Muslim cancer patients of Turkish or Moroccan background living in the Netherlands: “Good care implies that you can call on your family. Your family is obliged to care for their sick relative properly…The rule is – a devoted family cares for the ‘seriously ill’ patient” (34).

Furthermore, the vision for a ‘good death’ included one’s family providing support to the patient at home. As one participant in a study of older South Asians in East London states, “A true Muslim should die at Mecca, or Medina, and facing east. The Day of Judgment comes there. If it is not possible, then he should die at home with his family around him” (Amir, Pakistani male, age 58 years) (36).

Dying at home was generally preferred, as Arab Muslim participants in the aforementioned study done in Michigan indicated that they would prefer to be at home with their families at the end of life (12). Muslims’ desire to die at home was also reflected in a study of 300 cancer patients in Singapore, where 89.9% of Muslim respondents wanted to die at home compared to 70.7% of respondents overall (37). With the inability of most immigrant populations studied to return to “their homeland”, being at home in the presence of family was viewed as conveying respect for the dying person’s comfort (36). As authors of a qualitative study on the perspectives of South Asians living in the United Kingdom, which included Muslims and members of other religious groups, surrounding end-of-life healthcare in the home note:

Views of home as a place where religious needs at the point of death could be met contrasted sharply with most participants’ perceptions of what death might be like in the hospital. There was a belief that dying in hospital would restrict the family in their ability to perform caring and religious tasks and in providing comfort (36).

As part of the familial obligation to care, there was an expectation that one’s family would be aware of their responsibilities when the time came to care for their loved one, but also that financial considerations could waive this obligation. As noted by the authors of a study on end-of-life healthcare perspectives of older South Asians living in East London, which included Muslims and members of other religious groups:

Many believed that their family would “know what to do” and would do what they could for them when it was their time to face death and dying. Moreover, it was clearly indicated by some that pre-planning is unnecessary, since any decisions will depend on “family circumstances” (35).

The Family as Surrogate Communicators and Protectors of Hope.

In addition to serving as caretakers, patients’ families serve as surrogate communicators to healthcare teams and sustainers of a patient’s hope. Studies noted that one’s interactions with family and friends during serious and/or life-limiting illness impact one’s notions of hope (34, 38). Three studies reported that, for Muslims, talking about death and dying can contribute to the patient “giving up” and thus hastening one’s death (34, 38, 39). Accordingly, and given their religious belief in God’s control over disease and cure, there appears to be a reluctance to disclose prognosis or discuss terminal state as a factual certainty. As noted in a study of cancer patients in the Netherlands of Turkish or Moroccan background: “Some respondents also say that they cannot take away the patient’s hope for religious reasons. According to them, it is for Allah to decide when someone is going to die; life and the possibility of recovery are in Allah’s hands” (34). Furthermore, “relatives and friends encourage(d) participants to keep an optimistic attitude and expressed their belief in future improvement in their foundation either through medical care or a divine miracle” (38). Aside from giving hope to the patient, the skirting of matter-of-fact prognostication served to protect the family from anxiety and stress (35). Studies reported that Muslim patients worried about being a burden on relatives, both emotionally and practically (35, 38–41).

In a qualitative study of South Asian patients with life-limiting illnesses in Scotland, the lack of discussions about death and dying among Muslim participants was said to be a barrier to accessing hospice and palliative care (39). The control of information from family to patient, especially in the context of language barriers and families serving as interpreters also creates tension for health professionals (39). As the wife of a South Asian Muslim patient shared, “I said to them ‘don’t tell him how long [he has to live]’ but they said if he asks any questions, they’ll have to tell him. He never asked” (Carer 20, wife of Muslim patient with cancer, Stage 1 interview) (39).

Lack of Knowledge

The second theme relates to a lack of knowledge of both the religious and biomedical contexts on the part of many stakeholders. Specific subthemes were (i) a lack of provider knowledge and comfort surrounding religious dimensions of end-of-life healthcare, (ii) a lack of patient and family knowledge on the role of palliative care and/or advance care planning, and (iii) a lack of educational resources to facilitate Muslim engagement with palliative care.

Lack of Provider Knowledge and Comfort Surrounding Religious Dimensions of End-of-life Healthcare.

Barriers to advance care planning (ACP) and goals of care discussions with Muslim patients and families were attributed to preconceived notions of patients’ preferences and/or a lack of understanding of Islamic cultural/religious practices. In a study of 74 interdisciplinary healthcare workers, clinicians appear to avoid ACP discussions with certain religious beliefs, highlighting Muslims, assuming patients would be reluctant to participate (42); clinicians also voiced a lack of awareness of teachings and traditions around ACP and end-of-life healthcare among Muslims. Illustratively, a study assessing healthcare workers’ knowledge of teachings around end-of-life healthcare of the three major monotheistic religions (Christianity, Judaism, Islam) reported that providers had the least perceived understanding of Islamic traditions, regardless of provider specialty or seniority (43).

Further exploring the impact of limited cultural knowledge, healthcare workers interviewed as part of a study of South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients in Scotland and their caregivers described a fear of making a “cultural blunder” as a contributing factor to the avoidance of providing palliative care (39):

Most healthcare and social care professionals expressed good intentions in striving to provide equitable care but were concerned by their lack of cultural understanding and were uncertain about how to adapt their usual care. “Not knowing much about the religion . . . that is sometimes difficult because you don’t really know what you are talking about . . . maybe if I had known more about that then I could have been more help to him” (Patient 20, interview with professional after death) (39).

Lack of Patient and Family Knowledge on the Role of Palliative Care and/or Advance Care Planning.

For Muslim patients and families, there appear to be significant knowledge gaps surrounding palliative care and ACP. In a study of 148 Muslim adults living in the United States, about half (46.6%) of participants had not heard about ACP (44). This was associated with low rates of engagement in ACP, evidenced by a lack of ACP documents and formal ACP conversations (44). In another study using the same dataset, awareness and knowledge of ACP predicted engagement in ACP, as did immigration status and level of acculturation, suggesting that increased years of residency in non-Muslim majority nations may afford more opportunity for ACP engagement and foster understanding (45).

Lack of Educational Resources to Facilitate Muslim Engagement with Palliative Care.

The apparent lack of knowledge could be related to a lack of educational resources, as noted in a national survey consisting of 62 hospice social workers. In this study, almost all identified the importance of religion and spirituality amongst their patients, and more than half (68%) requested more education about the religious and spiritual needs of their patients, especially Muslims (46). Other professionals recognized a lack of training in diversity and cultural awareness as a problem, or that existing training was ineffective (39, 46). One study piloted an educational intervention consisting of a 60-minute video podcast as a resource. That intervention significantly increased provider understanding of Christian, Jewish, and Islamic teachings around end-of-life healthcare (43).

Muslim Physician Perspectives and Practices.

The third theme focused on Muslim physician experiences in end-of-life healthcare delivery. Two subthemes emerged: (i) the influence of provider religiosity on healthcare delivery and (ii) variability among Muslim physician practices in end-of-life healthcare.

The Influence of Provider Religiosity on Healthcare Delivery.

Physician religion and spirituality impacted views surrounding the provision of spiritual care at the end of life (33, 47, 48). In a study of Muslim physicians in the United States, higher physician religiosity was associated with lower odds of addressing non-Muslim patients’ religious or spiritual needs (47). In that study, more than half of participants believed it was never or rarely appropriate to encourage non-Muslim patients at end-of-life to seek forgiveness of those they have wronged or to seek reconciliation with God, which may signal further discomfort in engaging in religiously laden end-of-life care conversations with patients with a different religious background (47).

Another analysis of the same dataset revealed that more religious physicians struggled ethically and psychologically with withdrawing life-sustaining therapy in competent adults (48). A study of the palliative care attitudes and practices of Muslim doctors in the Netherlands echoed these findings; Muslim physicians were more likely to oppose withholding or withdrawing artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH) when compared to non-evangelical Protestant or Catholic physicians (49).

In a qualitative study of 15 Muslim physicians, also in the Netherlands, palliative care was described as “serving the ultimate goal in medicine: avoiding suffering” (50). In another study of 10 Muslim physicians in the Netherlands, palliative sedation was noted as alleviating suffering and a professional duty. Indeed, even though Islamic law views palliative sedation as a prohibited act, some Muslim physicians participated in this practice as they viewed alleviating suffering as a professional obligation: “As far as I am concerned, as a physician I am there to put the patient first and also to protect them, and in this pain relief is a must” (Khadidja) (51).

In both studies, however, interviewees spoke of the potential conflict that palliative care (and palliative sedation) could have with the Islamic perspectives on suffering, especially as a means of expiation of sins (50, 51). Muslim physicians struggled to reconcile these views. As one participant shared:

“Some views within Islam say: well suffering is a kind of penance, a means by which you expiate your sins. But this is contrary to the steps you would normally take as a doctor [to alleviate suffering/pain]…” (quote 19, participant 6, line 167–170) (51).

Variability Among Muslim Physician Practices in End-of-Life Healthcare.

Overall, the opinions of Muslim physicians surrounding the end of life were not uniform. A study of 461 Muslim physicians practicing in both Muslim-majority and non-Muslim majority countries surveyed perspectives about Islamic views surrounding resuscitation. Notably, physicians graduating from or practicing in non-Muslim majority countries were more likely to agree that do not resuscitate (DNR) was acceptable in Islam compared to their counterparts in Muslim-majority nations (52).

This variability was further exemplified when looking at Muslim physician views surrounding death by neurologic criteria (DNC). The results of a study of 255 Muslim American physicians highlight differing perspectives. While the majority (90%) agreed that cardiac death was considered death, participants were divided on whether ‘brain death’ and cardiac death were equivalent states (54% in agreement) (53). In contrast, a survey of 92 Muslim American health professionals found that 84% of respondents believed that if a person is determined to be dead by neurologic criteria, they are considered dead; yet half of respondents felt family should have choice in whether evaluation for DNC is performed and whether organ support is discontinued after DNC (54).

When compared to other physician groups, other differences may appear. For example, a study of end-of-life healthcare decisions of 3086 patients over 18 months in various European intensive care units found that end-of-life healthcare varied depending on the physician’s religious affiliation; life-sustaining therapy was withheld more often than withdrawn if the physician was Muslim (63%, total n=24), Jewish or Greek Orthodox (33).

Discussion

Our systematic literature review sought to identify the experiences, needs, and challenges of Muslim patients and caregivers within non-Muslim majority nations with regard to end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care. While we obtained some insights from the extant studies, the research literature, by and large, is too scant to provide substantive details; 29 empirical studies cannot ground definitive conclusions about Muslim experiences, needs, and challenges related to end-of-life healthcare. As such, the principal finding from our review is that greater research is needed.

Nonetheless, our research reveals several important themes about Muslim engagement with end-of-life healthcare and describes specific gaps in the literature. Principally, studies highlight profound knowledge gaps among Muslim patients and family members about the importance of advance care planning as well as decisional points of import and religious and ethical dimensions of such decisions. Simultaneously, end-of-life healthcare providers struggle with a lack of understanding of Muslim cultural or religious mores and have few resources to fill in this knowledge. Knowledge and research gaps, in our view, may contribute to the lack of access and utilization of palliative and hospice care among Muslim populations, and to a poor quality of care delivered for those who do obtain such services. The scant research literature likely exacerbates this gap as few investigators appear to be focusing on investigating Muslim patient and caregiver experiences, needs, and challenges. Thus, knowledge cannot be generated and the goal of improving healthcare quality at the end of life is frustrated.

Accordingly, there is an urgent need to build research platforms to fill in such educational and resource gaps. Academic healthcare systems should partner with Muslim communities to conduct community-engaged research that maps out specific knowledge gaps and community concerns, and subsequently design and test interventions to address them. It is noteworthy that only a handful of studies examined Muslim experiences and needs related to palliative and hospice care. Without detailed research into Muslim values, needs, and perspectives on palliative and hospice care, the ability to tailor these services is out of reach. Moreover, the lack of research may exacerbate underutilization and healthcare inequities. Hence, we call on healthcare research funders, both local and national, to support descriptive research focused on assessing Muslim Americans’ understanding of, values related to, and need for palliative and hospice care. Lastly, given the importance of religion in the healthcare decision-making of Muslims, and the ethical challenges that appear to arise in end-of-life healthcare, it would be prudent for researchers and educators to partner with Islamic authorities in such efforts.

There are several limitations to this study. We limited our review to published articles, so expert opinion, conference proceedings, and other commentary pieces were not included. Though studies in all high-income, non-Muslim majority countries were included, due to the paucity of published studies in this population, a relatively small number of countries were represented: the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Canada, Belgium, and Singapore. The exclusion of non-English publications may have contributed to this limited capture. Furthermore, our development of themes rested on the results sections of the papers reviewed and not the participant data itself; as such, our findings may not fully reflect participant experiences. Finally, it is critical not to overgeneralize our findings because the literature is quite limited, and Muslims are quite diverse. While we hazard that the shared religious identity of Muslims, as well the common features of healthcare systems in mid- to high-income countries, allow for aggregating the experiences, needs, and challenges of the Muslims living in non-Muslim majority nations together, other aspects of identity (e.g., ethnicity) and other contextual circumstances (e.g., immigrant status) may more significantly shape end-of-life healthcare experiences, needs, and challenges of participants in the studies we reviewed. Again, further research may be able to disentangle these various intersectional factors and provide more actionable data on how to better attend to the shared values among Muslim communities whilst also honoring the individual unique qualities inherent to anyone who calls themselves a Muslim. Despite our study’s limitations, our work, nonetheless, provides the foundation for future directed and targeted studies that begin to fill in knowledge around Muslim engagement with end-of-life healthcare in non-Muslim majority nations.

Key message:

Few studies examine the experiences, needs, and challenges of Muslim patients and caregivers in non-Muslim majority nations with end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care. Yet, studies highlight the importance of family involvement in end-of-life care and significant knowledge gaps for patients and providers that impede quality care delivery.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Elizabeth Suelzer for her help with the literature search, Farrukh Chaudhry for his help with title and abstract review, and Raudah Yunus for her help with quality assessment.

Funding:

This project was partially supported by the CTSI Team Science-Guided Integrated Clinical and Research Ensemble, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number 2UL1 TR001436.

Appendix A: List of countries included in the systematic review.

| Andorra | Denmark | Japan | San Marino |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Estonia | Korea | Seychelles |

| Aruba | Faroe Islands | Latvia | Singapore |

| Australia | Finland | Liechtenstein | Sint Maarten (Dutch part) |

| Austria | France | Lithuania | Slovak Republic |

| Bahamas | French Polynesia | Macao | Slovenia |

| Barbados | Germany | Malta | Spain |

| Belgium | Gibraltar | Monaco | St. Kitts and Nevis |

| Bermuda | Greece | Nauru | St. Martin (French part) |

| British Virgin Islands | Greenland | Netherlands | Sweden |

| Canada | Guam | New Caledonia | Switzerland |

| Cayman Islands | Hong Kong | New Zealand | Taiwan |

| Channel Islands | Hungary | N. Mariana Islands | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Chile | Iceland | Norway | Turks and Caicos |

| Croatia | Ireland | Palau | United Kingdom |

| Curacao | Isle of Man | Poland | United States |

| Cyprus | Israel | Portugal | Uruguay |

| Czech Republic | Italy | Puerto Rico | U.S. Virgin Islands |

Appendix B: Search strategy.

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to March 24, 2022> | ||

| 1 | Islam/ or Islam*.mp. or Muslim*.mp. | 13700 |

| 2 | Palliative Care/ or “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”/ or Palliative Medicine/ or exp Terminal Care/ or Hospices/ or exp Advance Care Planning/ or Terminally Ill/ or exp Withholding Treatment/ or Right to Die/ | 121408 |

| 3 | (palliative or hospice* or end-of-life or terminal care or (terminal* adj3 ill*) or dying or (advance* adj3 plan*) or (advance* adj3 directive*) or living will* or euthanasia or resuscitat* or assisted suicide* or assisted death or right to die or death with dignity or DNR order* or ((treatment or care) adj3 (withhold* or cessation*))).mp. | 291838 |

| 4 | 2 or 3 | 292207 |

| 5 | 1 and 4 | 431 |

| 6 | limit 5 to english | 408 |

| Scopus | ||

| #1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY(Islam* OR Muslim*) | 443533 |

| #2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY((palliative OR hospice* OR end-of-life OR “terminal care” OR (terminal* W/3 ill*) OR dying OR (advance* W/3 plan*) OR (advance* W/3 directive*) OR “living will*” OR euthanasia OR resuscitat* OR “assisted suicide*” OR “assisted death” OR “right to die” OR “death with dignity” OR “DNR order*” OR ((treatment OR care) W/3 (withhold* OR cessation*)))) | 106421 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 717 |

| Limits: publication types - article, review, note letter, conference paper, short survey; language - English | 571 | |

| Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities, Emerging Sources Citation Index | ||

| #1 | TS=(Islam* OR Muslim*) | 64708 |

| #2 | TS=((palliative OR hospice* OR end-of-life OR “terminal care” OR (terminal* NEAR/3 ill*) OR dying OR (advance* NEAR/3 plan*) OR (advance* NEAR/3 directive*) OR “living will*” OR euthanasia OR resuscitat* OR “assisted suicide*” OR “assisted death” OR “right to die” OR “death with dignity” OR “DNR order*” OR ((treatment OR care) NEAR/3 (withhold* OR cessation*)))) | 754902 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 715 |

| Limits: publication types - articles, review articles, proceedings papers, early access, editorial materials; language - English | 607 | |

| CINAHL | ||

| S1 | TI (Islam* OR Muslim*) OR AB (Islam* OR Muslim*) OR (MH “Islam”) | 7705 |

| S2 | TI (((palliative OR hospice* OR end-of-life OR “terminal care” OR (terminal* N3 ill*) OR dying OR (advance* N3 plan*) OR (advance* N3 directive*) OR “living will*” OR euthanasia OR resuscitat* OR “assisted suicide*” OR “assisted death” OR “right to die” OR “death with dignity” OR “DNR order*” OR ((treatment OR care) N3 (withhold* OR cessation*))))) OR AB (((palliative OR hospice* OR end-of-life OR “terminal care” OR (terminal* N3 ill*) OR dying OR (advance* N3 plan*) OR (advance* N3 directive*) OR “living will*” OR euthanasia OR resuscitat* OR “assisted suicide*” OR “assisted death” OR “right to die” OR “death with dignity” OR “DNR order*” OR ((treatment OR care) N3 (withhold* OR cessation*))))) OR ((MH “Palliative Care”) OR (MH “Palliative Medicine”) OR (MH “Terminal Care+”) OR (MH “Hospice Care”) OR (MH “Advance Care Planning”) OR (MH “Terminally Ill Patients+”) OR (MH “Euthanasia, Passive”) OR (MH “Right to Die”)) | 136710 |

| S3 | S1 AND S2 | 318 |

| Limits: source type - Academic Journals; language - English | 279 | |

| Cochrane Library | ||

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Islam] explode all trees | 80 |

| #2 | (islam* or muslim*):ti,ab,kw | 811 |

| #3 | #1 or #2 | 811 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Palliative Care] explode all trees | 1748 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Hospices] explode all trees | 43 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor: [Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing] explode all trees | 40 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor: [Terminal Care] explode all trees | 506 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Palliative Medicine] explode all trees | 2 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Terminal Care] explode all trees | 506 |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Advance Care Planning] explode all trees | 288 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor: [Terminally Ill] explode all trees | 95 |

| #12 | MeSH descriptor: [Withholding Treatment] explode all trees | 437 |

| #13 | MeSH descriptor: [Right to Die] explode all trees | 4 |

| #14 | (((palliative OR hospice* OR end-of-life OR “terminal care” OR (terminal* NEAR/3 ill*) OR dying OR (advance* NEAR/3 plan*) OR (advance* NEAR/3 directive*) OR “living will*” OR euthanasia OR resuscitat* OR “assisted suicide*” OR “assisted death” OR “right to die” OR “death with dignity” OR “DNEAR/R order*” OR ((treatment OR care) NEAR/3 (withhold* OR cessation*))))):ti,ab,kw | 23475 |

| #15 | {OR #4-#14} | 23475 |

| #16 | #3 AND #15 | 5 |

Appendix C: Information about article quality ratings.

| Article | Qualsyst rating |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Ahaddour, Van den Branden, & Broeckaert (40) | 0.90 |

| Ahaddour, Van den Branden, & Broeckaert (56) | 0.95 |

| Ashana et al. (42) | 0.76 |

| Baeke, Wils, & Broeckaert (41) | 0.80 |

| Bani Melhem et al. (44) | 0.95 |

| Bani Melhem et al. (45) | 0.98 |

| Curlin et al. (57) | 0.95 |

| de Graaff et al. (33) | 0.79 |

| Duffy et al. (12) | 0.78 |

| Duivenbode, Hall, & Padela (48) | 1.00 |

| Gaveras et al. (58) | 0.80 |

| Hamouda, Emanuel, & Padela (47) | 1.00 |

| Ho et al. (59) | 0.95 |

| Hong et al. (37) | 1.00 |

| Kristiansen et al. (38) | 0.88 |

| Lewis, Kitamura, & Padela (55) | 0.85 |

| Moale et al. (43) | 0.86 |

| Muishout et al. (52) | 0.83 |

| Muishout et al. (51) | 0.79 |

| Nayfeh et al. (60) | 0.98 |

| Popal, Hall, & Padela (54) | 0.95 |

| Saeed et al. (53) | 0.81 |

| Sprung et al. (49) | 0.93 |

| Tay, Mohamad Zam, & Cheng (36) | 0.83 |

| Venkatasalu, Arthur, & Seymour (34) | 0.85 |

| Venkatasalu, Seymour, & Arthur (35) | 0.78 |

| Wesley, Tunney, & Duncan (46) | 0.77 |

| Wolenberg et al. (50) | 0.93 |

| Worth et al. (39) | 0.79 |

Appendix D: Number of papers addressing the experiences, needs, and challenges of patients according to different types of care (n = 17).

| Total* | Experiences | Needs | Challenges | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| End-of-life | 14 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Hospice | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Palliative | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 17 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

The number of articles adds up to more than what is listed in the Total row and column because some articles discussed more than one area of experiences, needs, and challenges or included more than one type of care.

Appendix E: Number of papers addressing the experiences, needs, and challenges of caregivers according to different types of care (n = 16).

| Total* | Experiences | Needs | Challenges | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| End-of-life | 13 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hospice | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Palliative | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 16 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

The number of articles adds up to more than what is listed in the Total row and column because some articles discussed more than one area of experiences, needs, and challenges or included more than one type of care.

Appendix F: Number of articles addressing healthcare domains by population studied (n=29).

| Total* | Structure | Physical | Psychological | Social | Spiritual | Cultural | Care of Patients | Ethical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 17 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Caregivers | 16 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 29 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 8 |

Structure = Structure and processes of care; Physical = Physical aspects of care; Psychological = Psychological and psychiatric aspects of care; Social = Social aspects of care; Spiritual = Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care; Cultural = Cultural aspects of care; Care of patients = Care of patients nearing the end of life; Ethical = Ethical and legal aspects of care

The number of articles adds up to more than what is listed in the Total row and column because some articles included both patients and caregivers as the populations studied or included multiple healthcare domains.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center. 2015. The future of world religions: population growth projections, 2010–2050. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/.

- 2.Harford JB, Aljawi DM. The need for more and better palliative care for Muslim patients. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(1):1–4. 10.1017/S1478951512000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pew Research Center. 2017. U.S. Muslims concerned about their place in society, but continue to believe in the American dream. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/.

- 4.Al-Shahri M. The future of palliative care in the Islamic world. West J Med. 2002;176(1):60–61. 10.1136/ewjm.176.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaly M, Diamond RR, El-Akoum M, Hassan A. Palliative care and Islamic ethics: exploring key issues and best practice: special report in collaboration with the Research Center for Islamic Legislation and Ethics. Qatar Foundation: World Innovation Summit for Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padela AI, Curlin FA. Religion and disparities: considering the influences of Islam on the health of American Muslims. J Relig Health. 2013;52(4):1333–1345. 10.1007/s10943-012-9620-y/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padela AI, Zaidi D. The Islamic tradition and health inequities: A preliminary conceptual model based on a systematic literature review of Muslim health-care disparities. Avicenna J Med. 2018;8(01):1–13. 10.4103/ajm.AJM_134_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arozullah AM, Padela AI, Volkan Stodolsky M, Kholwadia MA. Causes and means of healing: an Islamic ontological perspective. J Relig Health. 2020;59(2):796–803. 10.1007/s10943-018-0666-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padela AI, Killawi A, Forman J, DeMonner S, Heisler M. American Muslim perceptions of healing: key agents in healing, and their roles. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(6):846–858. 10.1177/1049732312438969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yacoub AAA. The fiqh of medicine: responses in Islamic jurisprudence to developments in medical science. London: Ta-Ha Publishers, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasnain R, Rana S. Unveiling Muslim voices: aging parents with disabilities and their adult children and family caregivers in the United States. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2010;26(1):46–61. 10.1097/TGR.0b013e3181cd6988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy SA, Jackson FC, Schim SM, Ronis DL, Fowler KE. Racial/ethnic preferences, sex preferences, and perceived discrimination related to end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):150–157. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boucher NA, Siddiqui EA, Koenig HG. Supporting Muslim patients during advanced illness. Perm J. 2017;21:16–190. 10.7812/TPP/16-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Heeti RM. Why nursing homes will not work: Caring for the needs of the aging Muslim American population. Elder Law J. 2007;15:205–231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choong KA. Islam and palliative care. Glob Bioeth. 2015;26(1):28–42. 10.1080/11287462.2015.1008752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodríguez Del Pozo P, Fins JJ. Death, dying and informatics: misrepresenting religion on MedLine. BMC Med Ethics. 2005;6(1):6. 10.1186/1472-6939-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Sinclair S, Horst G. A knowledge synthesis of culturally- and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: findings from a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:107. 10.1186/s12877-016-0282-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakraborty R, El-Jawahri AR, Litzow MR, et al. A systematic review of religious beliefs about major end-of-life issues in the five major world religions. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(5):609–622. 10.1017/S1478951516001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudry M, Latif A, Warburton KG. An overview of the spiritual importances of end-of-life care among the five major faiths of the United Kingdom. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;18(1):23–31. 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheraghi MA, Payne S, Salsali M. Spiritual aspects of end-of-life care for Muslim patients: experiences from Iran. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(9):468–474. 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.9.19781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skinner M, Cowey E. Recognizing and responding to the spiritual needs of adults from minority religious groups in acute, chronic and palliative UK healthcare contexts: an explorative review. HSCC. 2019;7(1):37–56. 10.1558/hscc.36718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asadi-Lari M, Madjd Z, Goushegir SA. Gaps in the provision of spiritual care for terminally ill patients in Islamic societies - a systematic review. Advances in Palliative Medicine. 2008;7(2):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdullah R, Guo P, Harding R. Preferences and experiences of Muslim patients and their families in Muslim-majority countries for end-of-life care: a systematic review and thematic analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(6):1223–1238.e4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;(372):n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519. Accessed March 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. 2004. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Available from: https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/48b9b989-c221-4df6-9e35-af782082280e.

- 28.National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th ed. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, 2018. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp/. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. London: SAGE Publishers, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gustafson C, Lazenby M. Assessing the unique experiences and needs of Muslim oncology patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care: an integrative review. J Palliat Care. 2019;34(1):52–61. 10.1177/0825859718800496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masoud B, Imane B, Naiire S. Patient awareness of palliative care: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Published online October 11, 2021:bmjspcare-2021–003072. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephenson P, Hebeshy M. The delivery of end-of-life spiritual care to Muslim patients by non-Muslim providers. Medsurg Nurs. 2018;27(5):281–285. 10.1177/0825859718800496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH, et al. The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1732–1739. 10.1007/s00134-007-0693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Graaff FM, Francke AL, van den Muijsenbergh ME, van der Geest S. “Palliative care”: a contradiction in terms? A qualitative study of cancer patients with a Turkish or Moroccan background, their relatives and care providers. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9(1):19. 10.1186/1472-684X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatasalu MR, Arthur A, Seymour J. Talking about end-of-life care: the perspectives of older South Asians living in East London. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2013;18(5):394–406. 10.1177/1744987113490712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkatasalu MR, Seymour JE, Arthur A. Dying at home: a qualitative study of the perspectives of older South Asians living in the United Kingdom. Palliat Med. 2014;28(3):264–272. 10.1177/0269216313506765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tay KJ, Mohamad Zam NA, Cheng CWS. Prevailing attitudes towards cancer: a multicultural survey in a tertiary outpatient setting. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2013;42(10):492–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristiansen M, Irshad T, Worth A, Bhopal R, Lawton J, Sheikh A. The practice of hope: a longitudinal, multi-perspective qualitative study among South Asian Sikhs and Muslims with life-limiting illness in Scotland. Ethn Health. 2014;19(1):1–19. 10.1080/13557858.2013.858108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, et al. Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338:b183. 10.1136/bmj.b183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahaddour C, Van den Branden S, Broeckaert B. Between quality of life and hope. Attitudes and beliefs of Muslim women toward withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Med Health Care and Philos. 2018;21(3):347–361. 10.1007/s11019-017-9808-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baeke G, Wils JP, Broeckaert B. “It’s in God’s hands”: the attitudes of elderly Muslim women in Antwerp, Belgium, toward active termination of life. AJOB Primary Research. 2012;3(2):36–47. 10.1080/21507716.2011.653471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashana DC, D’Arcangelo N, Gazarian PK, et al. “Don’t talk to them about goals of care”: understanding disparities in advance care planning. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(2):339–346. 10.1093/gerona/glab091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moale AC, Rajasekhara S, Ueng W, Mhaskar R. Educational intervention enhances clinician awareness of Christian, Jewish, and Islamic teachings around end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(1):62–70. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bani Melhem GA, Wallace DC, Adams JA, Ross R, Sudha S. Advance care planning engagement among Muslim community-dwelling adults living in the United States. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(6):479–488. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bani Melhem GA, Wallace DC, Adams JA, Ross R, Sudha S. Predictors of advance care planning engagement among Muslim Americans. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2023;25(4):204–214. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wesley C, Tunney K, Duncan E. Educational needs of hospice social workers: spiritual assessment and interventions with diverse populations. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21(1):40–46. 10.1177/104990910402100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamouda MA, Emanuel LL, Padela AI. Empathy and attending to patient religion/spirituality: findings from a national survey of Muslim physicians. J Health Care Chaplain. 2021;27(2):84–104. 10.1080/08854726.2019.1618063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duivenbode R, Hall S, Padela AI. Assessing relationships between Muslim physicians’ religiosity and end-of-life health-care attitudes and treatment recommendations: an exploratory national survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(9):780–788. 10.1177/1049909119833335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolenberg KM, Yoon JD, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA. Religion and United States physicians’ opinions and self-predicted practices concerning artificial nutrition and hydration. J Relig Health. 2013;52(4):1051–1065. 10.1007/s10943-013-9740-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muishout G, de la Croix A, Wiegers G, van Laarhoven HWM. Muslim doctors and decision making in palliative care: a discourse analysis. Mortality. 2022;27(3):289–306. 10.1080/13576275.2020.1865291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muishout G, van Laarhoven HWM, Wiegers G, Popp-Baier U. Muslim physicians and palliative care: attitudes towards the use of palliative sedation. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(11):3701–3710. 10.1007/s00520-018-4229-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saeed F, Kousar N, Aleem S, et al. End-of-life care beliefs among Muslim physicians. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(4):388–392. 10.1177/1049909114522687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popal S, Hall S, Padela AI. Muslim American physicians’ views on brain death: Findings from a national survey. Avicenna J Med. 2021;11(02):63–69. 10.4103/ajm.ajm_51_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis A, Kitamura E, Padela AI. Allied Muslim healthcare professional perspectives on death by neurologic criteria. Neurocrit Care. 2020;33(2):347–357. 10.1007/s12028-020-01019-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahaddour C, Van den Branden S, Broeckaert B. “God is the giver and taker of life”: Muslim beliefs and attitudes regarding assisted suicide and euthanasia. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018;9(1):1–11. 10.1080/23294515.2017.1420708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Curlin FA, Nwodim C, Vance JL, Chin MH, Lantos JD. To die, to sleep: US physicians’ religious and other objections to physician-assisted suicide, terminal sedation, and withdrawal of life support. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(2):112–120. 10.1177/1049909107310141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaveras EM, Kristiansen M, Worth A, Irshad T, Sheikh A. Social support for South Asian Muslim parents with life-limiting illness living in Scotland: a multiperspective qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004252. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho BJ, Akhileswaran R, Pang GSY, Koh GCH. An 11-year study of home hospice service trends in Singapore from 2000 to 2010. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):461–472. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong CY, Chow KY, Poulose J, et al. Place of death and its determinants for patients with cancer in Singapore: an analysis of data from the Singapore Cancer Registry, 2000–2009. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(10):1128–1134. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nayfeh A, Yarnell CJ, Dale C, et al. Evaluating satisfaction with the quality and provision of end-of-life care for patients from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):145. 10.1186/s12904-021-00841-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]