Summary

Mechanisms governing the maintenance of blood-producing hematopoietic stem and multipotent progenitor cells (HSPC) are incompletely understood; particularly, those regulating fate, ensuring long-term maintenance, and preventing aging-associated stem cell dysfunction. We uncovered a role for transitory free cytoplasmic iron as a rheostat for adult stem cell fate control. We found that HSPCs harbor comparatively small amounts of free iron and show activation of a conserved molecular response to limited iron - particularly during mitosis. To study the functional and molecular consequences of iron restriction, we developed models allowing for transient iron bioavailability limitation and combined single-molecule RNA quantification, metabolomics, single-cell transcriptomic analyses with functional studies. Our data reveal that activation of the limited iron response triggers coordinated metabolic and epigenetic events establishing stemness-conferring gene regulation. Notably, we find that aging-associated cytoplasmic iron loading reversibly attenuates iron-dependent cell fate control, explicating intervention strategies for dysfunctional aged stem cells.

eTOC Blurb

Preservation of adult stem cell identity following cell division is essential for sustained tissue maintenance and repair. Will, Kao and colleagues identify iron as a crucial regulator allowing hematopoietic stem cells to orchestrate metabolic and gene regulatory control during regenerative fate determination.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Bone marrow resident hematopoietic stem and multipotent progenitor cells (HSPC) sustain life-long blood formation1–4, but their function declines during aging.5,6 Accumulation of genetic and epigenetic gene-regulatory alterations occur in hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) over time and multiple cell replications.7,8 Albeit DNA repair-inflicted epigenetic infidelity has emerged as an important and reversible driver of aging9, clinically attainable strategies resetting this epigenetic attrition are unknown. Several mechanisms controlling stem cell identity and fate ensure long-term maintenance. How these programs are coordinated, particularly during cell division, and what triggers their aging-associated dysfunction10,11 has been unresolved. HSPC, as several other somatic stem cells, reside mostly in a quiescent state;3 infrequently dividing only when cued by distinct intrinsic12 and extrinsic signals13 to undergo cell division and contribute to mature blood cell production or replenish the stem cell pool.14,15 Each cell division demands wide-ranging molecular adaptations to meet the changing energetic and structural demands of mitosis.16–20 As these adaptations are largely incompatible with their sustained long-term function, stem cells must counteract mitosis-related molecular alterations - the processes at play have remained elusive thus far.

Our previous work uncovered the ability of iron chelating compounds to enhance the regenerative activity of human and mouse HSPC.21,22 The mechanistic driver had not been unresolved but our data suggested that intracellular labile iron restriction may play a critical role. Readily available iron catalyzes electron transfer reactions governing fundamental cellular processes, particularly those key for cell division.23 Eukaryotic cells contain numerous proteins relying on iron as a cofactor (e.g. in iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters) which are essential for DNA replication and repair, as well as metabolic catalysis and cell cycle progression24. However, cells limit the size of the intracellular labile iron pool (LIP), making up 0.1–3% of the total amount of cellular iron25, which curtails Fenton reaction-mediated ROS generation.26,27 Mechanisms defining LIP sizes are not well understood but may, at least partially, arise from a defined equilibrium of iron demand, storage capacity and local availability. Perturbations in LIP size rapidly trigger cellular iron homeostasis mechanisms, such as the activation of a highly conserved limited iron response restoring the LIP upon insufficient iron availability.27,28 Whether LIP size or iron homeostasis pathway activation change during hematopoiesis, and particularly cell division, has been unknown.

This study aimed at delineating the role and consequences of LIP restriction in the context of stem cell-specific metabolic and gene regulation, as well as in fate determination.

Results

HSPC contain the most restricted LIP among immature hematopoietic cells

The size of readily accessible functional intracellular LIP is influenced by the cellular state and function of cells.29,30 We employed a ferrous iron chemisensor (FeRhoNox) and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis to quantify cytoplasmic labile iron in cells of bone marrow (BM) derived immature hematopoietic cell compartments in young (2–3 months (mos.) old) mice.31,32 Compared with highly proliferative Lineage− (Lin−) and myeloid-restricted progenitor cells (Lin− cKit+ Sca-1−, LK), HSPC which are comprised of HSC (CD48− CD150+ 33 or CD34− 34 LSK (Lin−Sca-1+cKit+)) and multipotent progenitor (CD48−CD150− LSK33; MPP) cells harbor well detectable but smaller LIP (Fig. 1A), consistent with their lower energetic requirements.35–39 Moreover, key regulators of iron sensing, transport and storage are detectable at the protein level in HSPC (Fig. S1A). We found robust expression of iron importer CD71 (transferrin receptor, Tfrc) in HSC (Fig. S1A,B), albeit only a small fraction was presented at the cell surface (Fig. S1B’) as reported before40–42. HSC showed low expression of iron responsive protein 2 (IRP2; Ireb2) (Fig. S1A), an iron sensor degraded by the proteasome in iron replete conditions.43,44 These data show that young HSPC curtail their LIP under steady state conditions, and suggested iron homeostasis activation in at least a subpopulation of stem cells.

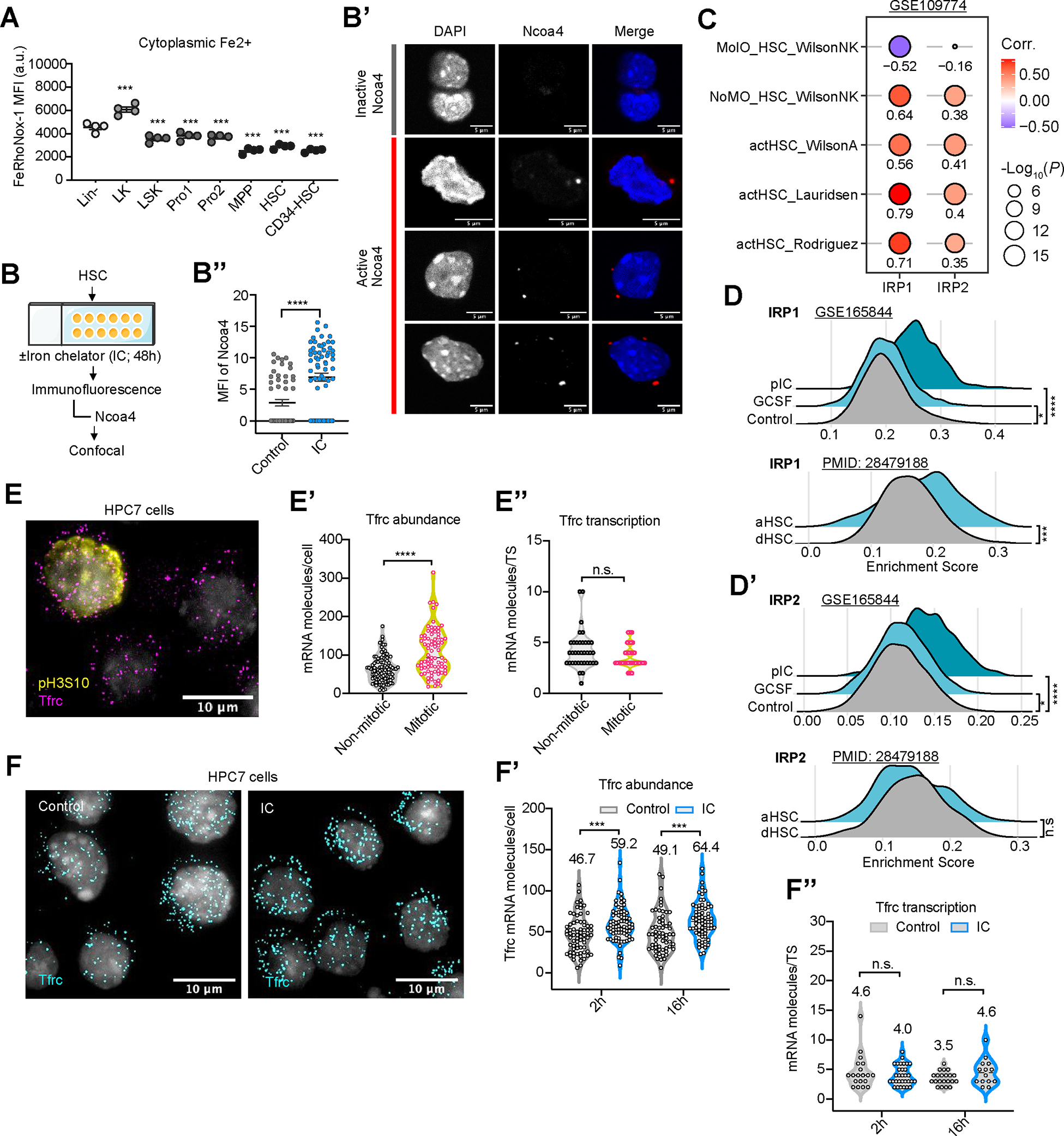

Figure 1. LIP restriction activates the limited iron response in HSC.

(A) Fe2+ LIP measurements in BM stem (HSC, CD150+CD48− LSK) and progenitor (LK, Lin− c-Kit+) cells using FeRhoNox and analysis by flow cytometry. n=4.

(B-B’’) Scheme of measuring ferritinophagy in HSC (B). Representative images (B’) and number of cells with activated Naco4 are shown (B’’). n=55 (Control), 66 (IC) cells.

(C) Correlation of enrichment score (ES) of IRP1 and IRP2 targets with ES of signatures for activated or quiescent HSC (using GSE109774). HSC activation signatures from Rodriguez et al (PMID: 32669716), Lauridsen et al (PMID: 30021172), Wilson A et al (PMID: 19062086), no molecular overlap (NoMO) from PMID:26004780. Signatures for quiescent HSC were defined by PMID:26004780 as the molecular overlapping population (MolO). Correlation estimated using Pearson coefficient R and linear regression t-test.

(D,D’) ES of IRP1 (D) and IRP2 (D’) targets in activated vs. quiescent HSC in scRNA-seq datasets GSE165844 (HSC activation after 2hr exposure to G-CSF or poly(I:C)); PMID 28479188: GFP label-retaining dormant HSC (dHSC) or GFP-negative activated HSC (aHSC).

(E-E’’) Filtered and overlaid images of treated HPC7 stained with Tfrc smRNA FISH, phosphoSer10 Histone H3 (E) and DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm; Violin plots of absolute numbers of cytoplasmic Tfrc mRNA molecules per cell (E’), pS10H3+ (mitotic; n=80) and pS10H3− (non-mitotic; n =104) cells; Violin plot of Tfrc nascent mRNA per transcription start site (TS) in non-mitotic (n=36) and mitotic (n=34) cells (E’’).

(F-F’’) Filtered and overlaid images of cells stained with smRNA FISH for Tfrc, control vs. IC-treated HPC7 cells. Violin plots of Tfrc mRNA molecules per cell after 2hrs (n=71 (Control); n=74 (IC)) or 16hs (n=62 (control); n=66 (IC)) (F); or nascent Tfrc mRNA per TS after 2hrs (n=19 (Control); n=31 (IC)); or 16hrs (n=21 (control); n=14 (IC)) (F’’).

If not specified otherwise, data are mean ± SEM (A, B’’). Significance indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 was calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: B’’, D, D’, E’, E’’, F’, and F’’; paired: A).

HSPC activate a limited iron response during mitosis

We next probed how HSPC would respond to acute experimental iron limitation (Fig. S1C). Compared with controls, iron chelator (IC)-exposed primary HSPC showed elevated CD71 cell surface presentation (Fig. S1D), and increased uptake of transferrin (Fig. S1E–E’’) upon IC treatment. IC exposure further led to stabilization Ncoa4, a rate-limiting ferritinophagy effector45 (Fig. 1B–B’’; S1F); it also prompted rapid decrease of iron-soring ferritin (Fig. S1G,H) in HPC7 cells, a well-established mouse HSPC cell line46.

Restriction of intracellular labile iron is sensed and corrected by iron responsive proteins 1 and 2 (IRP1, IRP2). These proteins bind RNA stem loops formed by iron responsive elements (IRE) in transcripts encoding proteins driving iron-, oxygen- and energy metabolism, including CD71-encoding Tfrc, to post-transcriptionally control protein translation.47 Single cell gene expression data set analysis of murine BM cells showed a strong, positive correlation of experimentally validated IRP-targets in regenerating (activated) HSPC (Fig. 1C). Similarly, IRP targets were significantly enriched in activated primary HSC (Fig. 1D,D’). Short-term exposure to IC triggered differential transcript expression of known IRP targets in purified HSC (Fig. S1I). We hypothesized that metabolic changes in the lead-up to cell division increase iron demand and stimulate the IRP/IRE system which is experimentally phenocopied by exposure to IC. To test this prediction, we quantified Tfrc abundance and transcription at single cell and single-molecule resolution using single-molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smRNA-FISH)48 (Fig. S1J–K’’). We performed Tfrc smRNA-FISH on cell cycle-synchronized HPC7 cells along with detection of pH3S10 to allow for the identification of mitotic cells (Fig. 1E). Compared with non-mitotic (pH3S10neg) cells, mitotic (pH3S10pos) cells showed an increase in cytoplasmic mRNA levels (Fig. 1E’) without elevated transcriptional activity (Fig. 1E’’; S1L,L’). Consistently, IC exposure of only 2hrs sufficed to significantly augment cytoplasmic Tfrc (Fig. 1F–F’). At the same time, IC-exposed cells displayed no signs of increased transcriptional activity at the Tfrc locus (Fig. 1F’’; S1M). In further support, Tfrchigh expressing primary HSPC showed significantly higher enrichment of gene signatures of activated stem cells than Tfrclow expressing cells (Fig. S1N).

These observations demonstrate that HSPC sense and counteract acute iron limitation by mounting a canonical limited iron response.

Activation of the limited iron response increases HSPC regeneration

To gain better insights into the acute molecular effects of experimental iron limitation in stem cells from young animals, we conducted single cell transcriptomic analysis of primary HSPC (CD150+CD48− LSK (Lin−Sca-1+cKit+)) following ex vivo IC (or vehicle control) treatment for 48hrs (Fig. S2A). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis uncovered seven clusters (C0–6) in control and IC-treated specimen (Fig. 2A); latent time prediction identified C0 and C1 as the least, and C4–6 as more differentiated cell entities (Fig. 2A’). Gene set enrichment analysis (Fig. S2B; Table S1) allowed the inference of cell identities denominating cell in C0–3 as HSC-like, and C4–6 as megakaryocytic (Mk) lineage-primed multipotent progenitor cells (Fig. 2B). We found 9.6% more stem-like cells (C0–3) at the expense of Mk-primed HSPC (C4–6) following IC exposure compared with controls (Fig. 2B’; S2C,D).

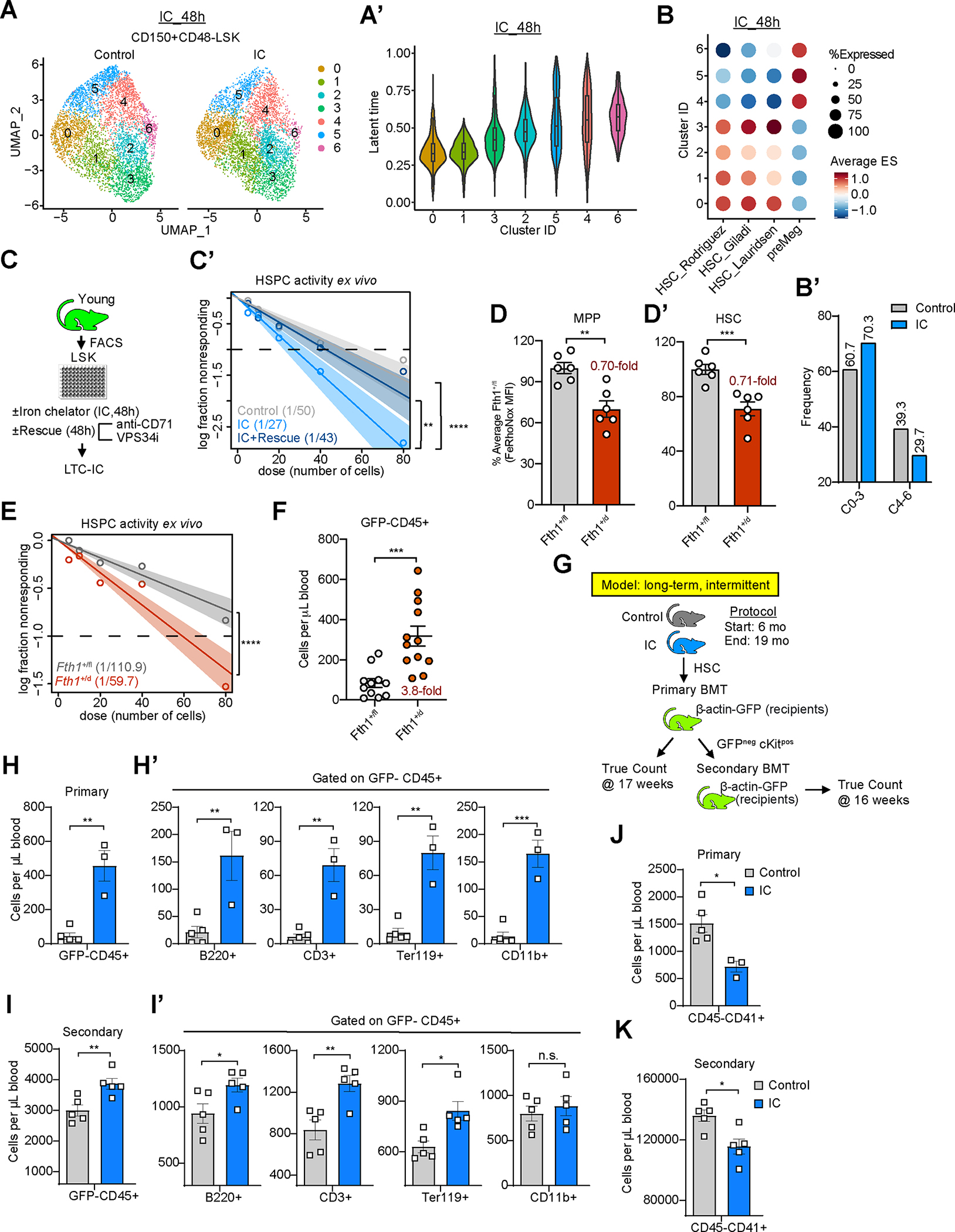

Figure 2. Activation of the labile iron response enhances regenerative activity of HPSC.

(A-A’) UMAP plot of cell clustering of HSC 48hrs after ex vivo treatment with DFO (IC) or vehicle control. Equal numbers of cells (4000) shown for IC and control (A). Latent time analysis of HSC clusters. Latent time of 0 represents least differentiated state (A’).

(B-B’) Score of HSC signatures from Rodriguez et al. (PMID: 32669716), Giladi et al. (PMID: 29915358), and Lauridsen et al. (PMID: 30021172), as well as pre-meg (Mk-primed) signature from Rodriguez et al. (PMID: 32669716) in induced clusters (B). Proportion of HSC-like (C0, C1, C2, C3) and Mk-primed (C4, C5, C6) clusters in IC vs. control (B’).

(C-C’) Experimental strategy to quantify regenerative HSC activity upon IC exposure alone or with Vps34 inhibitor and a CD71 blocking antibody (C). LTC-IC frequencies (shown in parentheses) by ELDA (C’). n=5

(D,D’) Fe2+ LIP measurements in MPP (D) and HSC (D’) cells comparing heterozygous Fth1 (Fth1+/d) or wild-type (Fth1+/fl) BM by FeRhoNox and flow cytometry. n=6

(E) Quantification of functional HSPC in heterozygous Fth1 (Fth1+/d) or wild-type (Fth1+/fl) LSK cells using LTC-IC assay. LTC-IC frequencies were shown in parentheses. n=7

(F) 6-week engraftment after intra-femural transplantation of Fth1+/d or Fth1+/fl HSC into beta-actin-GFP expressing recipients. n=11 (control) or 12 (+/d). Overall donor cell (GFP−CD45+) chimerism.

(G) Experimental strategy.

(H-I’) Multi-lineage cell output of HSC after LT-Int IC. Donor cell engraftment of control or IC-treated HSC in recipient mice upon primary (H, H’) and secondary (I, I’) transplantation. (H,I) CD45+ donor (GFP−) cells; (H’,I’) B220+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, Ter119+ erythroid cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells.

(J,K) Donor-derived cells derived platelets (GFP−CD45− CD41+ FSC/SSClow) in recipient mice of primary (J) and secondary (K) transplantation.

If not specified otherwise, data are mean ± SEM (D, D’, F and H-K). Significance indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 was calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: D, D’, F, and H-K), or Poisson statistics (C’, E).

To test whether acute activation of the limited iron response has functional consequences in HSPC, we pulse-treated purified young LSK cells with IC alone or in combination with pharmacological blockade of iron import and intracellular iron mobilization. We then measured stem cell activity in long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) assays (without any further treatment), which showed that inhibition of iron homeostasis pathway activation reversed the stem cell-stimulatory phenotype of transient acute iron limitation (Fig. 2C,C’; S2E). Moreover, heterozygous deletion of Fth1 (Fth1flox)49 by Vav-Cre (referred to as Fth1d/wt; Fig. S2F,G; Fig. 2H–H’’’)50, restricting Fe2+ in MPP and HSC by ~30% (Fig. 2D,D’), increased LTC-IC activity of Fth1d/wt LSK cells (Fig. 2E) and multilineage regeneration capacity of HSC six weeks after transplantation (Fig. 2F; Fig. S2I–J’’’’) compared with controls. These results demonstrate that activation of the limited iron response is important for regenerating HSPC.

Development of a model of controlled iron restriction

We next established in vivo mouse models of controlled transient experimental iron limitation using deferoxamine (DFO), an extracellular IC.51 DFO is extensively used for mitigating pathological iron accumulation in patients; it is safe and precisely adjustable to the degree of iron overload in pediatric and adult patients52,53; and does not lead to iron deficiency in adults54–56 or children57,58 with appropriate total body iron content. To monitor acute effects of IC-mediated LIP restriction on HSPC in vivo, we subjected young mice (2–3-mos. old) for 14 days to daily injections of IC (or vehicle) (Fig. S2K; referred to as short-term IC intervention). This regimen effectively reduced body and cellular iron levels without causing overt iron deficiency phenotype (Fig. S2K’–M’’). While we did not observe a change in phenotypical HSPC numbers (Table S2), we found an increase in regenerative capacity (LTC-IC activity) of LSK cells isolated from IC-treated mice compared with vehicle control-treated cells (Fig. S2N).

Regenerative capacity of HSPC gradually declines over time in humans and mice.59–62 We next probed for the consequences of experimental iron restriction on long-term HSPC regeneration for which we subjected 6-month-old mice to a 13-month intermittent IC regimen (Fig. S2O; referred to as long-term intermittent (LT-Int) IC treatment). This treatment was well tolerated (S2P–Q’’) and restricted LIP size by 13.4% ± 7.1% (p<0.01) in HSC and 14.3% ± 8% (p<0.05) in myeloid-biased CD41+ HSC compared with mock treated control animals (Fig. S2R–R’’). We did not observe quantitative changes of phenotypical HSPC or mature hematopoietic cells upon this treatment (Table S2). However, HSC isolated from LT-Int IC-treated mice showed a remarkably augmented regenerative capacity evidenced by an almost 10.1 ± 3.4-fold (p=0.001) increase in total donor-derived hematopoietic cells along with robust and balanced multi-lineage output (Fig. 2G–H’) following adoptive cell transfer. The enhanced regenerative capacity of LT-Int IC-exposed HSPC persisted upon secondary transplantation (in absence on continued IC treatment) (Fig. 2I,I’). We also found reduced donor HSPC-originating platelets (Fig. 2J,K) and Mk-progenitors (Fig. S2S) in recipients of LT-IC HSC, in line with the observed reduction of Mk-biased HPSC following long-term LIP restriction (Fig. 2B,B’).

Together, this set of data strongly supports that intracellular iron limitation enhances the regenerative capacity of HSC and suggested long-term LIP restriction may be beneficial to safeguard HSPC function during aging.

Labile iron pool restriction improves the regenerative capacity of aged HSPC

Loss of iron homeostasis can occur during aging and manifests as iron deficiency anemia63; perturbed intracellular iron partition; decreased Fe-S cluster and heme biosynthesis64–68; or intracellular iron loading in terminally differentiated cells of several tissues69–73. We next assessed whether aging-associated impairment of iron homeostasis may contribute to the functional attrition of aged HSPC.

Comparative analysis of differential gene expression in aged mouse HSC and plasma protein levels in elderly humans (vs. young controls) uncovered a substantial overlap of dysregulated molecular pathways;74,75 which resembled genetically-induced iron overload76 (Fig. S3A). Gene expression alterations in aged HSC were inversely correlated with those found upon short-term IC exposure; particularly genes upregulated during aging were detected at lower abundance upon pharmacological LIP restriction (Fig. S3B,B’; Table S3). These affected genes with roles in megakaryopoiesis, and were enriched in mostly dormant Mk lineage-biased, von Willebrandt factor positive (Vwf+) HSC (Mk-HSC; known to expand and confer a platelet-bias during aging)77,78,79 (Fig. S3C). We also found an expanded LIP in HSC (by 34% ± 24.6%, p=0.024), and lineage-committed progenitors (by 23% ± 5%, p=0.018) isolated from aged mice compared with control cells from young animals (Fig. 3A,A’); a similar expansion of the LIP was detected in aged multipotent and committed progenitor cells (Fig. S3D). Assessment of peripheral blood iron parameters of aged mice showed no signs of an overt systemic iron overload (Fig. S3E).

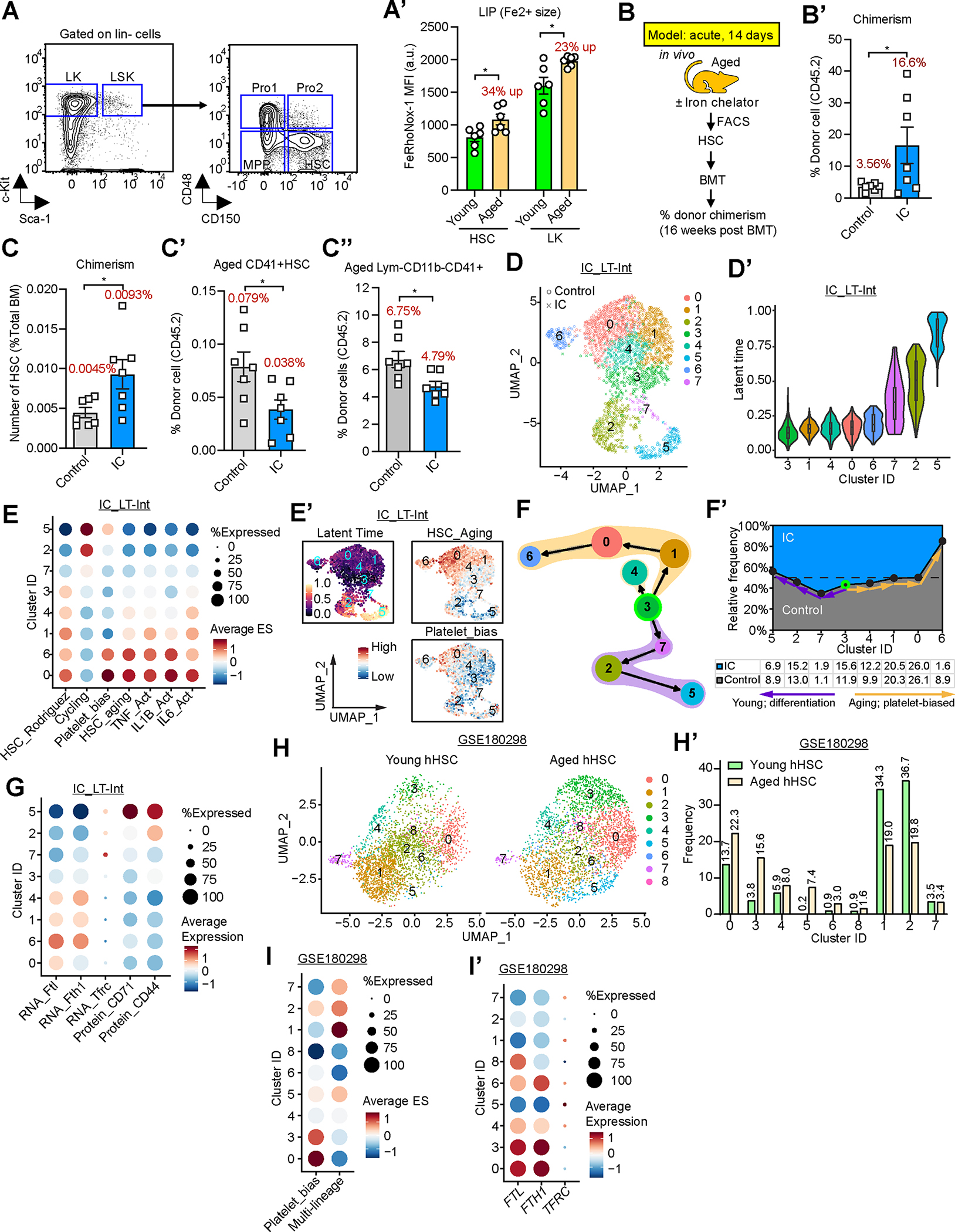

Figure 3. LIP restriction protects HSC regeneration during aging.

(A) Gating strategy for HSPC.

(A’) Fe2+ measurements in BM stem (HSC, CD150+CD48− LSK) and progenitor (LK, Lin−c-Kit+) cells (as in (A) from young (2–3mos.) and aged (22–24mos.) mice using FeRhoNox and FACS analysis. n 6.

(B-C’’) Donor-derived cells in recipient bone marrow 16 weeks after transplantation. (B) Experimental strategy to evaluate the effect of acute iron chelation on aged HSC. (B’) total CD45.2+ cells in BM of recipients; (C) CD45.2+ HSC; (C’) CD41+ HSC; (C’’) Mk-progenitors (CD41+CD3−CD4−CD8−B220−CD11b−). n=7.

(D-G) CITE-seq analysis of HSPC from LT-Int mice IC at 19 mos. of age. (D) UMAP plot of HSC clustering; (D’) Latent time analysis; (E) Average signature score of different gene sets across HSC clusters. (E’) UMAP plot with scores of the latent time, signature of HSC aging and platelet bias gene sets across different clusters. (F,F’) Trajectory inference of HSC clusters determined by scVelo latent time and PAGA. Arrows indicate differentiation direction between clusters with highest connectivity (F). Relative frequency of HSC clusters in IC vs. control groups; frequencies of different clusters shown underneath (F’). Relative frequencies stacked onto a 100% scale. (G) Average abundance of Tfrc, Ftl, and Fth1, as well as CD44 and CD71 on the cell across clusters.

(H-I’) Analysis of scRNA-seq data from human HSPC (GSE180298). (H) UMAP plot of clustering aged vs. young human cells. HSC cluster defined by positive expression of CD34, CRHBP, and HOPX. (H’) Proportion of clusters found altered in aged donors. (I,I’) Average signature scores of gene signatures for HSC with platelet bias or multi-lineage potential (I); average expression of FTL, FTH1, and TFRC across HSC clusters (I’).

If not specified otherwise, data are mean ± SEM (A’ and B’-C’’). Significance indicated as *p<0.05 was calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: A’, B’-C’’).

Chronic iron overload can be detrimental for cells,80 and is known to compromise HSC maintenance76,81. To test whehter modest intracellular iron loading contributes to the dysfunction of aged HSPC, we subjected aged mice to short-term in vivo iron limitation and subsequently assessed stem cell function by competitively transplanting equal numbers of purified phenotypical HSC into lethally irradiated young congenic recipients (Fig. 3B). The treatment was well tolerated in these cohorts (Fig. S3F; Table S2). All recipients showed an overall low donor cell chimerism, in line with previous work82; notably, recipients of short-term IC-treated aged donor stem cells showed an increase in overall donor cell chimerism (Fig. 3B’; S3G), and a 2.1 ± 1.1-fold (p=0.028) increase in donor-derived phenotypical HSC (Fig. 3C). We detected a concomitant 0.49 ± 0.31-fold (p=0.033) decrease in HSC and progenitors with cell surface presentation of glycoprotein (Gp) IIb/IIIa integrin (CD41) (Fig. 3C’). CD41+ HSC harbor a Mk-lineage differentiation bias and expand during aging.77 Recipients of IC-treated aged HSC showed reduced Mk-cell generation compared with control cell recipients (Fig. 3C’’). Consistently, ex vivo IC treatment of purified HSC followed by quantification of Mk-progenitors showed alleviation of the Mk-differentiation bias of aged stem cells (Fig. S3H) upon iron limitation (Fig. S3H’, H’’) consistent with a cell-autonomous effect. These data support that a moderately expanded LIP contributes to reversible aging-associated HSC dysfunction.

CITE-seq analysis of purified LSK populations isolated from aged mice having undergone LT-Int IC treatment (Fig. S3I) suggested that long-term LIP restriction can attenuate HSPC aging. We identified eight clusters (C0–7) (Fig. 3D) within CD150-presenting CD48-negative HSC (Fig. S3J); latent time analysis predicted C3, 1, 4, 0 and 6 as the least differentiated- and clusters 7, 2, and 5 as more differentiated stem cells (Fig. 3D’). Clusters 0, 1, and 6 showed higher enrichment scores of signatures for HSC aging and pro-inflammatory pathways, while gene expression of C3 cells resembled that of the young (Fig. 3E; S3K,K’); C0 and 6 were found likely to be platelet-biased HSC, and C5 Mk/platelet-biased progenitors (Fig. 3E,E’). LT-Int IC treatment increased lineage-unbiased HSC (C3) and actively cycling HSPC (C2) while reducing aged Mk/platelet-biased stem (C6) and progenitor (C5) cell populations (Fig. 3F–F’; Table S4).

Together, these observations show that iron loading and LIP expansion occur in aging HSPC and raised the possibility of iron-mediated fate determination.

Iron dependent stem cell fate control

We next quantified mRNA levels of Tfrc and Ftl and Fth1, as well as cell surface abundance of iron importers, CD71 and CD44 across C0–7 mouse HSC (Fig. 3G); and similarly analyzed published human single HSPC data (Fig. 3H–I’). Molecularly “young”, lineage-unbiased HSC seem to curtail their LIP as efficiently as chronologically young stem cells. Low-output/quiescent and high(er)-output/moderately cycling mouse HSC (C3 and 7, respectively) lacked the molecular tell-tale signs of aging, inflammation and platelet bias (Fig. 3E) and showed low Ftl and Fth1 expression and CD71 and CD44 cell surface presentation (Fig. 3G), in agreement with an iron-limited status. Aged human HSPC (Fig. 3H,H’) also harbored “young-like” subpopulations hallmarked by a lack of Mk-lineage bias (Fig. 3I; S3L) and low levels of FTL and FTH (C1, 2, 7; Fig. 3I’; S3M,N); notably, relative frequencies of some of these cell populations (C1, C2) markedly decline in the elderly (Fig. 3H’). This strongly suggests that LIP expansion does not uniformly occur in the aging HSPC population.

We collected evidence that primary dividing stem cells activate the limited iron response in vivo. Cycling mouse HSPC which lack aging and inflammation-associated signatures (C2, 5, 7; Fig. 3E) show the highest presentation of CD71 and/or CD44 on their cell surface; some of these cells also harbored high Tfrc expression alongside low abundance of Ftl and Fth1 (Fig. 3G). C2, 5 and 7 together constitute 20% of the HSC and consistent with the size of non-quiescent stem cell pools at steady state83. The HSC activation signature also strongly correlated with gene expression in stem cells with high Tfrc abundance (Fig. S3O,O’). We found similar subsets of cells showing an increase in TFRC abundance in a distinct subset of human HSPC (C1, 5 and 7; Fig. 3I’) with multilineage reconstitution capacity (Fig. 3I) in concomitant functional assays79.

Furthermore, we found evidence for an aged, Mk-biased HSC population to be sensitive to experimental LIP restriction. We observed a marked reduction of molecularly defined dormant Mk-primed mouse HSC (dMk-HSC) (C6) upon in vivo iron limitation (1.6% vs. 8.9% in controls) (Fig. 3F’). HSC subpopulations, unified by molecular features of stem cell aging and inflammation (Fig. 3E; C0, 1, 4 and 6), showed increased Ftl abundance with concomitantly low CD71 and CD44 presentation (Fig. 3G) consistent with an elevated intracellular iron load in these cells. Particularly C6 cells showed the highest levels of Ftl and Fth1 and lower abundance of CD71 and CD44 on their cell surface across all clusters. In support, young Vwf+ stem cells (enriched for dMk-HSC)84,85 also harbor increased expression of Ftl1 mRNA levels compared with Vwf-negative HSC (which are highly regenerative and lack Mk-bias84) (Fig. S3P–P’’). Elevated Ftl mRNA levels in Vwf+ HSC vs. Vwf− HSC and upon aging strongly suggest that mouse dMk-HSC have a higher labile iron content86,87 than other stem cell populations. Consistently, Mk-biased human HSC (C0, C3) not only expand during aging (Fig. 3H’,I) they also share the highest FTL and FTH levels among all HSPC subpopulations (Fig. 3I’).

These observations strongly support that iron homeostasis is essential for HSC fate control during long-term regeneration, and that iron-responsive gene regulation preserves stemness-programs in HSC. We next set out to characterize the underlying molecular mechanism at play.

Iron-responsive gene regulation is controlled by Tip60

Compared with controls, short-term ex vivo IC exposed HSPC showed signs of lysine acetyl transferase 5 / HIV-1 Tat-interacting protein 60 kD (Tip60) activation (Fig. 4A,B; Fig. S4A,B). Upon nuclear localization, Tip60 acts as the catalytic subunit of the NuA4 (nucleosome acetyltransferase of histone 4) complex; its chromatin binding activity increases due to co-factor independent autoacetylation upon elevated acetyl-CoA levels.88,89 Tip60/NuA4 activates select genes through acetylation of core histone (H) 4 at lysines (K) 5, 8 and 12, H2A at K5,90,91 and histone variants H2AX and H2AZ.92 We found a positive enrichment of H2AZac, H4K5ac, H4K8ac, H4K12ac, or H4K16ac-decorated genes in HSC following IC exposure (Fig. 4C); and noted enrichment of genes with transcription-activating mono- and tri methylation marks on H3K493, and transcriptional fidelity-enhancing trimethylated H3K3694 in HSC following IC treatment, which appeared to be concentrated at Tip60-occupied genes (Fig. 4C). Nuclear abundance of Tip60 (Fig. 4D,D’) and its chromatin recruitment (Fig. 4E) increased upon LIP restriction in young HSPC.

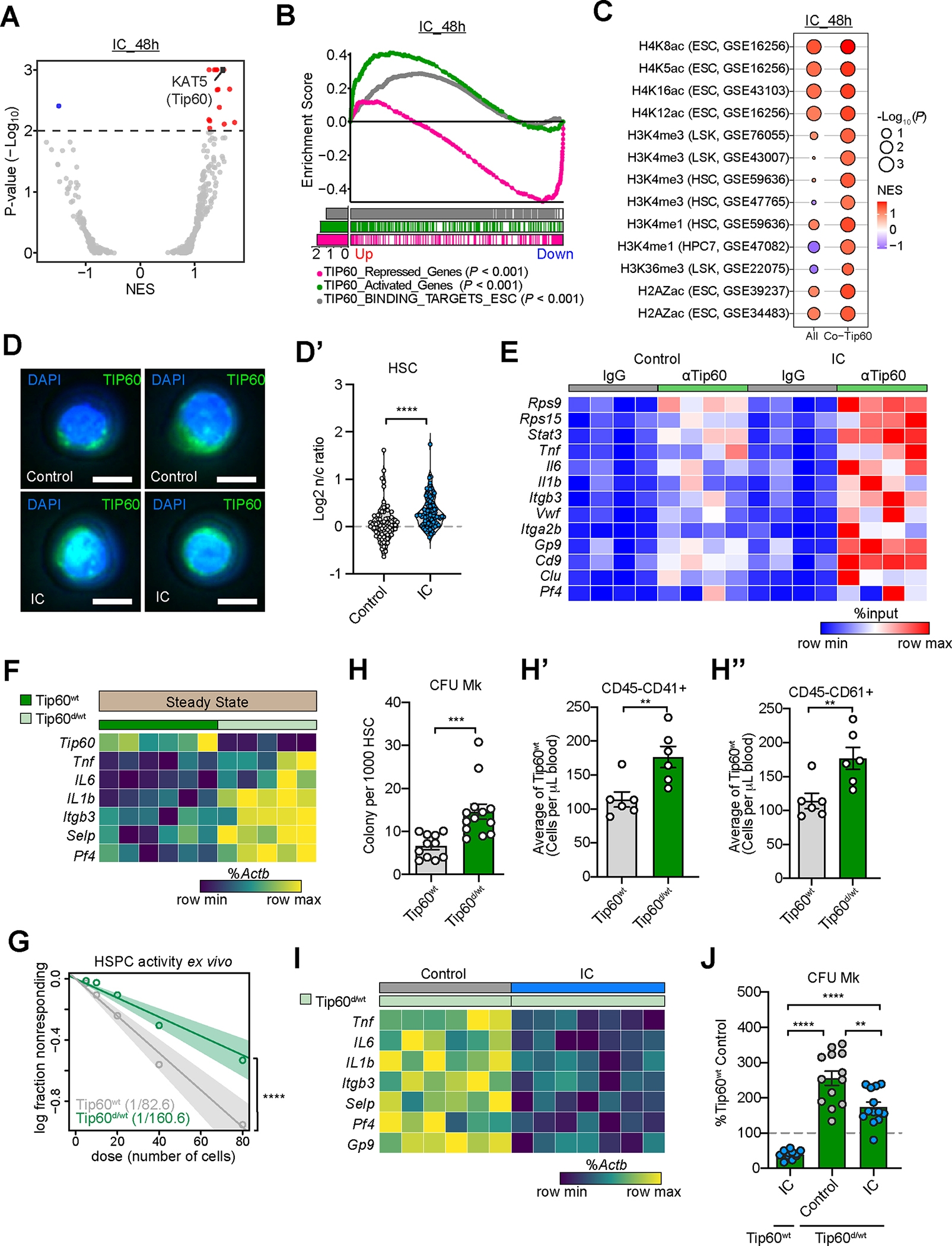

Figure 4. LIP restriction enhances Tip60-dependent fatty acid turn-over in HSPC.

(A-C) scRNA-seq of HSC following ex vivo IC (or vehicle) treatment for 48hrs. (A) Volcano plot of normalized enrichment scores (NES) of transcription factor targets (C3 GTRD transcription factor targets) by GSEAPreranked analysis. (B) GSEAPreranked analysis with Tip60-related up-regulated (Up) and down-regulated (Down) gene sets. (C) Balloon plot showing GSEAPreranked analysis of IC-associated expression profile in HSC with histone modifications and Tip60 binding-associated gene sets.

(D,D’) Nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (n/c) of Tip60 protein upon IC stimulation ex vivo for 16hrs in young HSC. Immunofluorescence images (D) and quantification (D’) are shown. n=79 or 94. Scale bars, 5μm.

(E) Tip60 occupancy in gene promoters by CUT&RUN using LSK cells ex vivo cultured with IC or vehicle control for 48hrs, followed by qPCR with pull-down DNA. Data presented as % of input; color was scaled relative to the minimal (blue) and maximum (red) values of each gene. Significantly different (p<0.05) gene occupancy by Tip60 (IC vs. Control) are shown. n=4

(F) Expression of Tip60 regulated iron dependent genes in purified HSC from Tip60 wildtype (Tip60wt) and Tip60 haploinsufficient (Tip60d/wt) mice by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as % of Actb, color was scaled relative to the minimal (dark teal) and maximum (yellow) values of each gene. Significantly different (p<0.05) gene expression (wt vs. d/wt) are shown. n=6

(G) Quantification of functional HSPC in Tip60d/wt or Tip60wt LSK cells using LTC-IC assay. LTC-IC frequencies shown in parentheses. n=7 or 8

(H-H’’) Megakaryocytic output of purified HSC (CD150+CD48− LSK) fromTip60d/wt mice compared with Tip60wt controls. Ex vivo colony formation in MegaCult assays (H, n=11 or 13); in vivo platelet generation (CD45− CD41+ (H’) and CD45−CD61+ (H’’); n=6) upon transplantation.

(I) Expression of Tip60-regulated iron-dependent genes in activated (2-month continuous low-dose lipopolysaccharide treatment in vivo) Tip60d/wt HSC treated with vehicle or intermittent IC (LPS+IC; rescue). n=6 or 7

(J) Quantification of CFU-Mk colonies from Tip60wt or Tip60d/wt HSC, and their response to IC normalized to percent of wildtype control. n=11–13

If not specified otherwise, data are mean (H-H’’ and J) ± SEM. Significance indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 was calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: D’ and H-H’’; paired: J), or Poisson statistics (G).

See also Figure S4.

Gene-specificity of the Tip60/NuA4 complex is conferred by several transcription factors, including Myc95,96,92. In the absence of elevated cMyc in the majority of stem cells upon IC exposure (Fig. S4C), Myc target genes were differentially expressed upon IC treatment (Fig. S4D), consistent with increased Myc activity in regenerating HSC97,98 (Fig. S4E,E’). HSPC isolated from a mouse model of iron overload76 further showed a substantial overlap of pathways shared with differential gene expression found in Myc or Tip60 deficient HSC (Fig. S4F). Moreover, we discovered that transient inhibition of Tip60 or Myc99 curtailed the gene regulatory and functional effects of acute iron limitation in HSPC (Fig. S4G–H’’). These data show that Tip60 and Myc cooperate in the regulation of functionally relevant iron-responsive gene expression in HSPC.

Tip60 is essential for sustained HSC maintenance; its homozygous loss in hematopoietic cells leads to rapid BM failure in mice.92 We next assessed, whether reduced Tip60 levels would be sufficient to compromise HSC function. HSPC derived from young hematopoietic cell-specific Tip60 haploinsufficient mice (Tip60flx/wt CAGGCre-ER™; referred to as Tip60d/wt)100 (Fig. S4I,I’) exhibited loss of Tip60 dependent gene regulation, particularly the de-repression of Mk and inflammation-associated genes (Fig. 4F; S4I’’). LTC-IC activity was reduced upon deletion Tip60 (Fig. 4G) alongside increased platelet production in vivo (Fig. 4H–H’’; S4J,J’). While acute iron limitation did not rescue the compromised function of Tip60-null (Tip60d/d) HSC (Fig. S4K–K’’), it restored Tip60-dependent gene regulation and curtailed the aberrant Mk-bias in regenerating Tip60d/wt HSC (Fig. 4I,J; S4L,L’).

Labile iron pool restriction augments fatty acid turnover

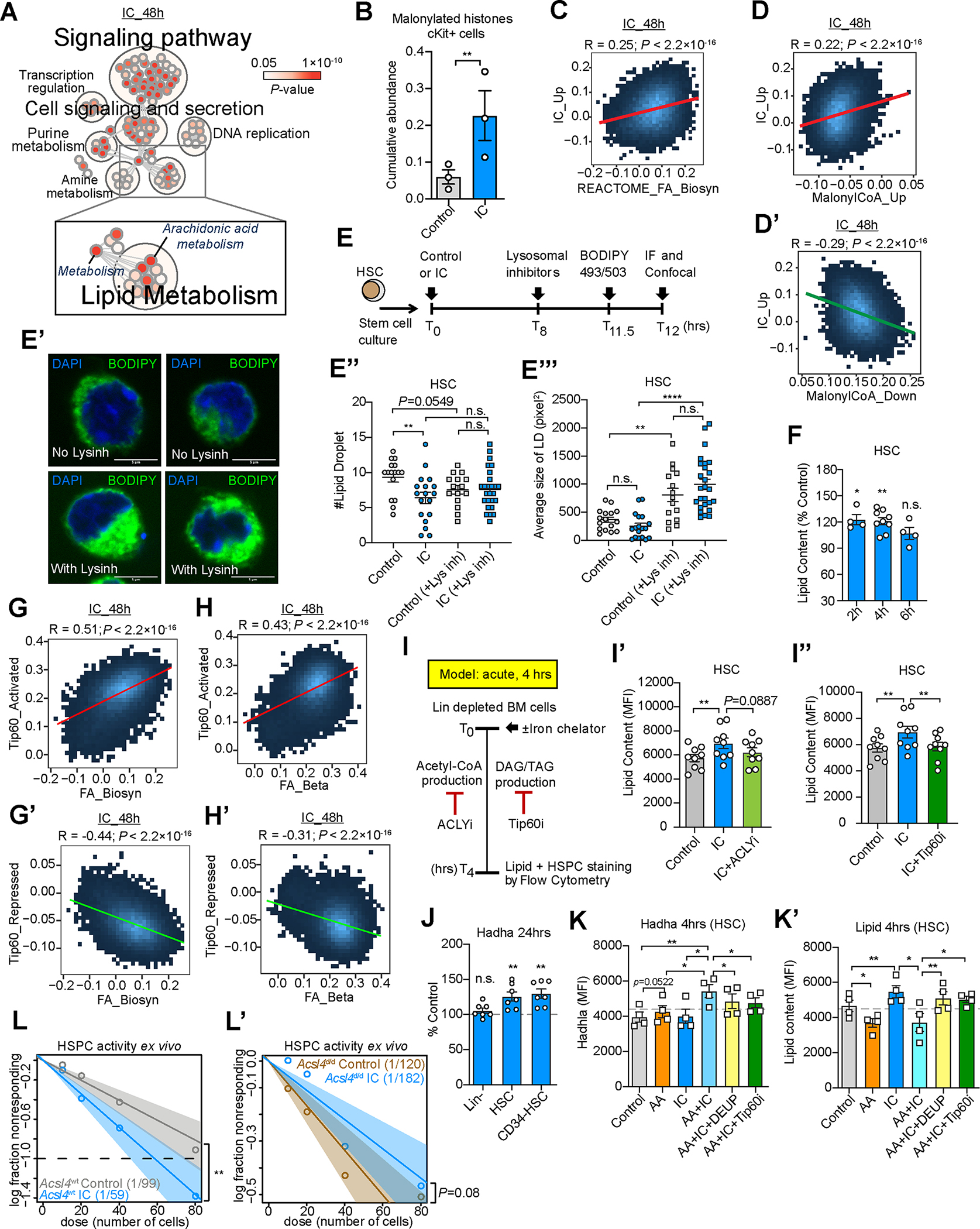

In support of LIP restriction impinging on metabolic control in stem cells, we found that primary mouse HSPC showed activation of gene expression of programs associated with lipid- and arachidonic acid metabolism, as well as fatty acid (FA) biosynthesis following LIP restriction compared with controls (Fig. 5A); and metabolomics analysis uncovered changes consistent with elevated lipid metabolism and acetyl-CoA levels following acute experimental iron limitation in HSPC (Fig. S5A; Table S5).

Figure 5. LIP restriction protects regenerative capacity of HSC during aging.

(A) Pathway network analysis of differential genes in mouse HSC upon 48 hours IC in vitro exposure. Significantly enriched pathways (p<0.05) by NetworkAnalyst analysis. Each circle represents a pathway, the color intensity is a mapping of enrichment significance p-value.

(B) Abundance of malonylated histones in control versus IC (DFO, 10 μM) treated c-Kit+ BM cells for 12hrs. n=3

(C-D’) Correlation of enrichment score of up-regulated genes in IC-treated HSC (CD150+CD48− LSK), with fatty acid biosynthesis (C) and up-regulated (D) or down-regulated (D’) DEG in malonyl-CoA treated LSK cells (GSE173256) in scRNA-seq of 48h IC-treated HSC.

(E-E’’’) LD turnover in young HSC upon a 12hr IC (or vehicle) treatment. Scheme illustrating introduction of iron chelator (IC, DFO), lysosomal inhibitors (leupeptin, NH4Cl) and lipid labeling dye (BODIPY 493/503) (E). Representative immunofluorescence images (control) are shown (E’), along LD numbers (E’’) and size (E’’’). n=18–39

(F) Quantification of neutral lipid content in young HSC after acute IC for 2, 4 or 6hrs in culture using LipiGreen and analysis by flow cytometry. n=4–9

(G-G’) Correlation of enrichment scores of genes activated (G) and repressed (G’) by Tip60 and associated with FA anabolism.

(H-H’) Correlation of enrichment scores of genes activated (H) and repressed (H’) by Tip60 and associated with FA catabolism.

(I-I’’) Scheme illustrating quantification of neutral lipid content in young HSC upon 4hrs in culture in the presence of an iron chelator alone, in combination with ATP citrate lyase inhibition (ACLYi, 20 μM SB 204990), or a Tip60 inhibitor (TH1834, 10 μM) (I). Neutral lipid content after acute IC alone or in combination with ACLYi (I’). n=9. Lipid content after acute iron chelation alone or in combination with Tip60i (I’’). n=9.

(J) Quantification of Hadha levels in Lin− BM cells, HSC and CD34− HSC populations 24hrs after IC exposure compared with vehicle controls. n=7

(K-K’) Quantification of Hadha levels (K) and lipid content (K’) by flow cytometry analysis in aged HSC after a 4hr exposure to arachidonic acid (AA, 40 μM) or IC (DFO, 20μM) alone, or in combination with inhibition of lipase (DEUP, 20μM) or Tip60 (TH1834, 10 μM). n=4

(L-L’) HSPC enumeration by LTC-IC following IC treatment with LSK cells from Acsl4 wildtype (Acsl4wt, L) or Acsl4 KO (Acsl4d/d, L’). Estimated LTC-IC frequencies in parentheses. n=4

If not specified otherwise, data are mean (B, E’’, E’’’, F, I’, I’’, and J-K’) ± SEM. Significance indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 were calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: E’’, E’’’; paired: B, F, I’, I’’, and J-K’), Poisson statistics (L and L’), or Pearson coefficient R and linear regression t test (C-D’ and G-H’).

FA metabolism is required for stem cell self-renewal101. In support of ongoing fatty acid synthesis (FAS), we found increased global histone acetylation, a highly sensitive and reversible sensor for fluctuating acetyl-CoA levels102; especially a gain in malonyl marks (Fig. 5B), activation of FAS (Fig. 5C), and malonyl-CoA associated gene expression programs (Fig. 5D,D’) in HSPC following IC treatment. FA can be subjected to de novo lipogenesis (DNL) of storage lipids (such as triacylglycerides (TAG) and diacylglycerides (DAG)) budding off the endoplasmic reticulum as lipid droplets (LD).103 We next quantified LD-formation and turnover104 in primary HSC (Fig. 5E,E’). Compared with controls, IC-treated HSC showed a lower number of LD (Fig. 5E’’) with a modestly reduced average size (Fig. 5E’’’). Inhibition of LD turnover105 increased LD size while modestly reducing LD numbers in control cells, consistent with increased fusion events103. LD-turnover inhibition similarly affected IC and control HSC (Fig. 5E’’,E’’’). Together, this indicated constitutive lipid mobilization in HSC at steady state which increases upon acute iron limitation. Next, we quantified neutral lipid abundance106 longitudinally following acute iron limitation. Compared with vehicle-cultured HSC (Fig. S5B), IC exposure acutely increased neutral lipid content at 2 and 4hrs, which became indistinguishable at 6hrs after treatment (Fig. 5F), indicating augmented DNL following iron restriction. As we also found strong correlation of Tip60-dependent gene regulation with FA oxidation (FAO) and biosynthesis-associated gene expression programs (Fig. 5G–H’), we speculated that Tip60, an activator of DNL in adipocytes107, partakes in the control of lipid metabolism in HSPC. In support, we found that acute impairment of Tip60 attenuated acute neutral lipid accumulation upon IC in primary HSC (Fig. 5I–I’’). This implicates Tip60 in HSPC FA metabolism and revealed that synthesized FA are primarily subjected to TAG/DAG production.

Under nutrient deprivation, cells mobilize FA from LD to increase FAO108,109. We next tested whether acute iron limitation increased FA flux to enhance mitochondrial β-oxidation in HSPC. In line, compared with control HSPC, we found elevated levels of hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase trifunctional multienzyme complex subunit alpha (Hadha), a rate limiting enzyme catalyzing long-chain FA oxidation,110 24hrs after IC treatment (Fig. 5J; S5C), or upon heterozygous deletion of Fth1 (Fig. S5D–D’’’). Furthermore, we observed increased abundance of Hadha in IC-treated HPC7 cells (Fig. S5E–E’’) which showed a concomitant increase in long-chain polyunsaturated FA arachidonic acid (20:4; AA) levels (Fig. S5F). We speculated that increasing extracellular AA abundance may augment IC-triggered lipid turnover and FAO. In support, combined AA supplementation and IC treatment increased Hadha levels in primary HSC (Fig. 5K,K’), as well as lineage-committed progenitor cells (Fig. S5G) compared with single agent controls. Notably, purified primary HSC showed a concomitantly decreased LD content when exposed to AA alone or in combination with IC, which could be abrogated by blocking either lipolysis or TAG synthesis (Fig. 5K’). This indicates that DNL and AA uptake synergistically enhance FAO upon acute iron limitation in HSC. In contrast, lineage-restricted progenitor cells increased Hadha upon IC and AA single agent treatment, but did not show a further elevation upon co-treatment (Fig. S5G), indicating that progenitor cells increase FAO predominantly through extracellular FA uptake.

We furhter found that inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-1a), mediating long-chain FA import into mitochondria111, prevented LTC-IC activity stimulation upon acute IC treatment of HSPC compared with single agent and mock treatment controls (Fig. S5H–H’’). Genetic ablation of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (Acsl4), which preferentially activates AA112 for mitochondrial import and whose abundance increased upon IC treatment (Fig. S5I), also attenuated the stem cell stimulatory effects of IC treatment in primary HSPC (Fig. 5L,L’; Fig. S5J–L’’).

Together, these data show that regenerative HSPC activity is supported by iron-dependent augmentation of FA metabolism.

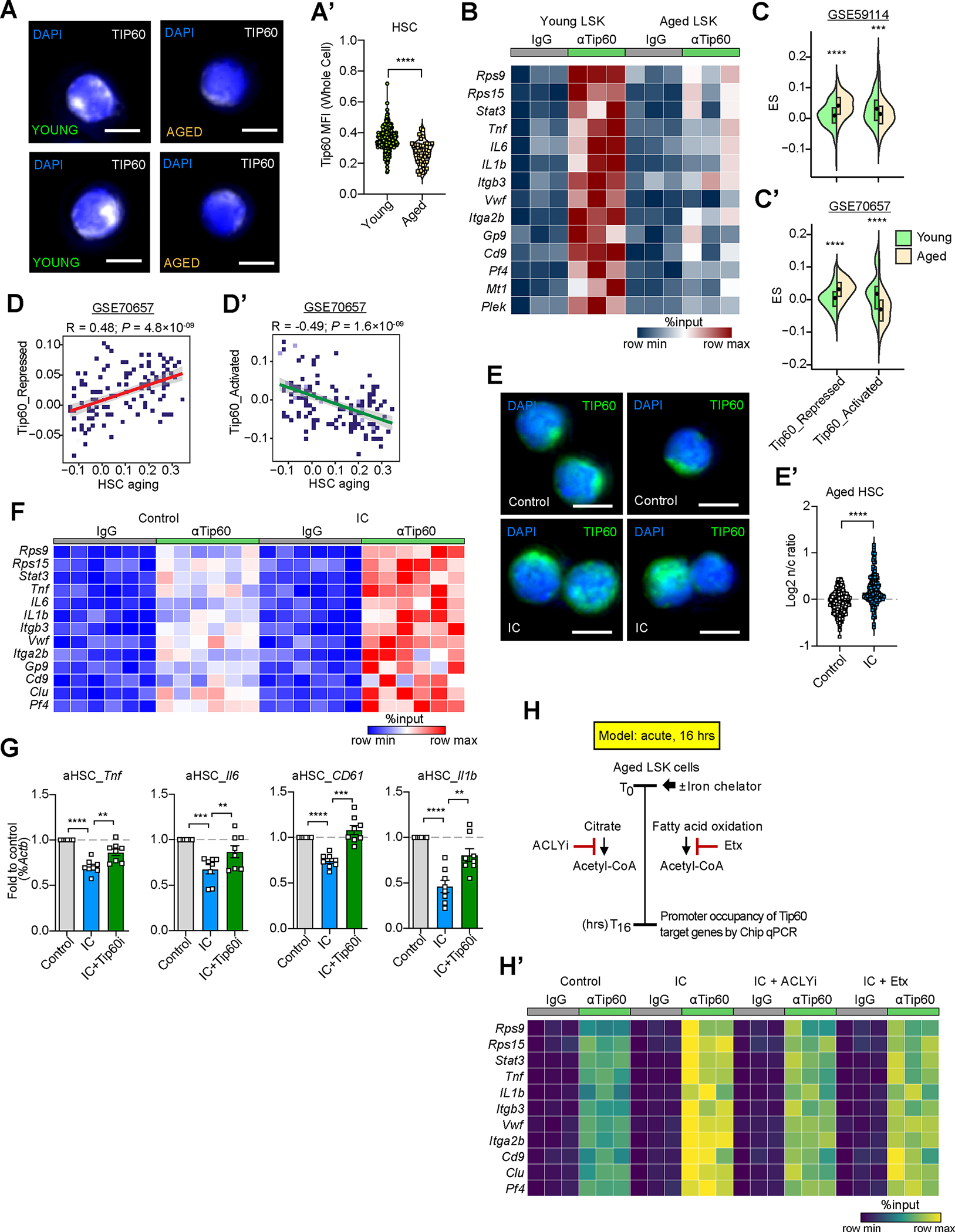

Mitigating intracellular iron loading restores Tip60 activity in aged HSC

We next predicted that aging-associated LIP expansion may blunt Tip60 activation. In support, we found that gene signatures of Tip60 impairment strongly correlated with HSC aging (Fig. S6A–B), or genetically-induced iron overload (Fig. S6B). Compared with young counterparts, aged HSC showed reduced Tip60 protein abundance (Fig. 6A,A’), chromatin recruitment (Fig. 6B) and loss of Tip60-dependent gene regulation (Fig. 6C–D’). Platelet-biased HSC with inferior peripheral blood contribution (“low-output”) (Fig. S6C–D’) showed loss of Tip60-dependent gene repression and activation compared with high-output HSC (Fig. S6E–F’). These observations suggested loss of iron-dependent Tip60-mediated gene expression as a functional driver of HSC aging. In line, ex vivo IC treatment increased Tip60’s nuclear abundance (Fig. 6E,E’), chromatin occupancy (Fig. 6F) and target gene expression (Fig. 6G; S6G) in aged stem cells compared with vehicle treated control stem cells. Notably, we found that iron-dependent Tip60-mediated gene regulation relied on FA metabolism (Fig. 6H,H’), and appears to be a driver of IC-mediated Mk-differentiation restriction in aged HSC (Fig. S6H–H’’). Together, these data establish Tip60 activation as an important mechanistic component of the enhanced regenerative capacity of aged HSC following LIP restriction.

Figure 6. Iron chelator-mediated labile iron pool restriction restores Tip60 activity and mitigates aging-associated HSC dysfunction.

(A,A’) Tip60 protein abundance (MFI) in young and aged HSC (CD150+CD48− LSK). Immunofluorescence images of Tip60 protein abundance and subcellular localization in young and aged HSC (A). Tip60 MFI in young and aged HSC (A’). n=297 (young) and 51 (aged). Scale bars, 5μm.

(B) Tip60 occupancy in gene promoters in young and aged LSK. Significantly different (p<0.05) gene occupancy by Tip60 (young LSK vs. aged LSK) is shown. n=3

(C,C’) Scores of Tip60 regulated genes in aged versus young HSC scRNAseq datasets GSE59114 (C) and GSE70657 (C’). Up-regulated (Tip60 repressed) and down-regulated (Tip60 activated) genes upon Tip60 knockout in LSK cells used as gene sets.

(D,D’) Correlation of Tip60 regulated genes with HSC aging signature, using single cell expression data from GSE70657. Up-regulated (D) and down-regulated (D’) genes upon Tip60 knockout in LSK cells were used as gene sets. Correlation using Pearson coefficient R and linear regression t test.

(E,E’) Nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (n/c) of Tip60 protein in aged HSC upon IC stimulation ex vivo for 16hrs. Immunofluorescence images (E) and quantification (E’) are shown. Scale bars, 5μm. n=299 or 160.

(F) Tip60 occupancy in gene promoters in aged LSK cells cultured for 48hrs with vehicle or IC. Significantly different (p<0.05) gene occupancy by Tip60 (IC vs. Control) are shown. n=6

(G) Expression changes of Tip60/Myc target genes in aged HSC after IC treatment alone or in combination with inhibition of Tip60 (Tip60i) by qPCR analysis. Fold changes of genes across treatment groups are shown. Data are mean ± SEM. n=8.

(H,H’) Scheme for assessing IC-mediated Tip60 dependent acetyl-CoA production in increasing Tip60 promoter occupancy of target genes (H). (H’) Heatmap showing ChIP-qPCR of aged LSK cells ex vivo cultured for 16hrs with vehicle or IC alone, or IC in combination with inhibitors for ACLY (SB 204990, 20 μM) or CPT1a (Etomoxir, 10 μM). Significantly different (p<0.05) gene occupancy by Tip60 (IC vs. Control, ACLYi or CPT1i) are shown. n=3

Significance indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 was calculated using Student’s t test (unpaired: A’, C, C’, and E’; paired: G and H’).

See also Figure S6.

Collectively, our study’s findings establish the pool of readily accessible cytoplasmic iron as a key cellular rheostat allowing HSC to enable and orchestrate metabolic and gene regulatory fate control at steady state and during regeneration; they further suggest that cytoplasmic iron loading is a key factor in driving HSC dysfunction via Tip60 perturbation during aging (Fig. S6I).

Discussion

Intact iron homeostasis is known to ensure proper hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion and differentiation,113 and limit oxidative damage-induced elimination of hematopoietic stem cells.76 Here, we have delineated four additional molecular principles governing iron-dependent adult stem cell function.

We uncovered that HSPC limit their LIP and show an ongoing limited iron response at steady state which is augmented during mitosis and by experimental acute iron limitation. This demonstrates that the size of the LIP is tightly regulated and closely linked with the functional state of quiescent and metabolically less active stem cells35–39. It also reveals that metabolic demands during mitosis provide an effective trigger for enhancing iron homeostasis pathway activation in HSPC.

We show increased lipid carbon-associated epigenetic regulation to follow iron homeostasis pathway activation in HSC; and discovered a central role for lysine acetyl transferase Tip60/KAT5 in HSPC lipid synthesis, likely via acetylation and activation of Lipin1107. Our data support that Tip60 constitutes a gene-regulatory switch in HSPC - following acute iron limitation, presumably following autoacetylation114 in response to increasing cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA levels, which enhances Tip60-dependent gene regulation. The mechanism behind the observed locus-specific gene regulatory effects of Tip60 in HSPC involves cooperating factor cMyc92,115, which may counteract TFEB-dependent lysosomal activation to allow for HSC activation42. While the exact drivers of Tip60-dependent gene regulation in HSPC remain to be elucidated, our findings strengthen the emerging paradigm of a tight interconnection between lipid metabolism and epigenetic control in stem cells116,117 - a circuit also hijacked by malignant stem cells establishing therapy resistance 118. Given that many somatic stem cells share principle regulatory mechanisms,119 it is possible that LIP serves as a general rheostat in various adult stem cells.

Our data show that LIP restriction serves as a unique molecular relay, licensing specific metabolic pathways under regenerative stress - particularly FAO which is known to expand the HSC pool37. In contrast to highly proliferative progenitor cells, HSPC appear to employ DNL to fuel mitochondrial FAO. Simultaneous activation of anabolic along with catabolic FA metabolism is a unique metabolic circuit which is typically suppressed in most cells120. However, a reduced redox state (such as during iron limitation121) appears to allow HSPC to establish and enforce this peculiar metabolic circuit.122–124

Lastly, we demonstrate that cytoplasmic iron loading underpins stem cell aging through impairing FA metabolism and Tip60-dependent gene regulation; and that mitigating LIP expansion safeguards HSC function during aging. This finding is in line with health benefits of frequent blood donations125 which reduce body iron,126,127 select against pre-leukemic HSPC clones,128 and curtail the risk of acute myeloid leukemia129. Future work needs to delineate the exact trigger(s) increasing the LIP in aging hematopoietic (stem) cells. As loss of iron homeostasis is observed in a large fraction of the elderly,130 in patients with chronic inflammation131 or cancer,132 our findings will have implications in understanding and therapeutic mitigation of altered stem cell function in a wide range of degenerative and malignant pathologies.

Limitations of the study

In previous work21 and herein, we have corroborated all key observations on acute iron limitation in HSPC using several clinically available IC. The use of genetic models to impair central metabolic regulators of cellular homeostasis come with the caveat of permanent metabolic adaptation to the absence of key enzymes which trigger a cache of compensatory metabolic effects we cannot control for. This makes testing the acute effects of metabolic pathway interference essential. We accomplished this through chemical impairment of enzymes using specific and validated pharmacologic modulators. This study identified mice with hematopoietic Fth1 haploinsufficiency as promising models for genetic LIP restriction; yet, future efforts are needed to firmly establish the mode and long-term consequences of LIP restriction through Fth1 dose reduction.

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Britta Will (britta.will@einsteinmed.edu).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in the study are available from the lead contact under material transfer request.

Data and code availability

NGS data generated during this study have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Key Resources Table.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Hadha Unconjugated; Anti-mouse [Clone: EPR17940] | Abcam | Cat#ab203114; RRID:AB_3083611 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A21245; RRID:AB_2535813 |

| biotinylated anti-CD44 | Invitrogen | Cat#13-0441-82; RRID:AB_466442 |

| Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A-11037; RRID:AB_2534095 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A-11008; RRID:AB_143165 |

| CD3e eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: 145-2C11] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0031-82; RRID:AB_10735092 |

| CD4 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: GK1.5] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0041-82; RRID:AB_10718983 |

| CD8a eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: 53-6.7] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0081-82; RRID:AB_1272198 |

| CD19 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBio1D3(1D3)] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0193-82; RRID:AB_2734905 |

| B220 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: RA3-6B2] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0452-82; RRID:AB_1548761 |

| Ter119 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: TER-119] | eBioscience | Cat#48-5921-82; RRID:AB_1518808 |

| Gr1 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: RB6-8C5] | eBioscience | Cat#48-5931-82; RRID:AB_1548788 |

| Sca-1 APC; Anti-mouse [Clone: D7] | eBioscience | Cat#17-5981-82; RRID:AB_469487 |

| c-Kit APC-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: 2B8] | eBioscience | Cat#A15423; RRID:AB_2534436 |

| CD150 PE; Anti-mouse [Clone: TC15-12F12.2] | Biolegend | Cat#115904; RRID:AB_313683 |

| CD48 PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: HM48-1] | Biolegend | Cat#103424; RRID:AB_2075049 |

| CD34 FITC; Anti-mouse [Clone: RAM34] | eBioscience | Cat#11-0341-82; RRID:AB_465021 |

| CD41 eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBioMWReg30 ] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0411-82; RRID:AB_1582238 |

| CD3e PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: 145-2C11] | eBioscience | Cat#15-0031-82; RRID:AB_468690 |

| CD4 PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: GK1.5] | eBioscience | Cat#15-0041-82; RRID:AB_468695 |

| CD8a PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: 53-6.7] | eBioscience | Cat#15-0081-82; RRID:AB_468706 |

| CD19 PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBio1D3(1D3)] | eBioscience | Cat#15-0193-82; RRID:AB_657672 |

| B220 PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: RA3-6B2] | eBioscience | Cat#15-0452-82; RRID:AB_468755 |

| Ter119 PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: TER-119] | eBioscience | Cat#15-5921-82; RRID:AB_468810 |

| Gr1 PE-Cy5; Anti-mouse [Clone: RB6-8C5] | eBioscience | Cat#15-5931-82; RRID:AB_468813 |

| CD3e Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: 145-2C11] | eBioscience | Cat#13-0031-82; RRID:AB_466319 |

| CD4 Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: GK1.5] | eBioscience | Cat#13-0041-82; RRID:AB_466325 |

| CD8a Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: 53-6.7] | eBioscience | Cat#13-0081-82; RRID:AB_466346 |

| CD19 Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBio1D3(1D3)] | eBioscience | Cat#13-0193-82; RRID:AB_657656 |

| B220 Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: RA3-6B2] | eBioscience | Cat#13-0452-82; RRID:AB_466449 |

| Ter119 Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: TER-119] | eBioscience | Cat#13-5921-82; RRID:AB_466797 |

| Gr1 Biotin; Anti-mouse [Clone: RB6-8C5] | eBioscience | Cat#13-5931-82; RRID:AB_466800 |

| Sca-1 Brilliant Violet 421; Anti-mouse [Clone: D7] | eBioscience | Cat#404-5981-82; RRID:AB_2929076 |

| c-Kit Brilliant Violet 605; Anti-mouse [Clone: 2B8] | Biolegend | Cat#105847; RRID:AB_2783047 |

| CD150 PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: TC15-12F12.2] | Biolegend | Cat#115914; RRID:AB_439797 |

| CD48 APC-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: HM48-1] | Biolegend | Cat#103432; RRID:AB_2561463 |

| CD41 FITC; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBioMWReg30 ] | eBioscience | Cat#11-0411-82; RRID:AB_763481 |

| CD45.1 PerCP-Cy5.5; Anti-mouse [Clone: A20] | eBioscience | Cat#A14794; RRID:AB_2534309 |

| CD45.2 BV510; Anti-mouse [Clone: 104] | BD Biosciences | Cat#740131; RRID:AB_2739888 |

| cKit PE; Anti-mouse [Clone: 104D2] | BioLegend | Cat#105807; RRID:AB_313216 |

| CD48 APC-eFluor 780; Anti-mouse [Clone: HM48-1] | eBioscience | Cat#47-0481-82; RRID:AB_2573962 |

| CD3e PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: 145-2C11] | eBioscience | Cat#25-0031-82; RRID:AB_469572 |

| CD4 PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: GK1.5] | eBioscience | Cat#25-0041-82; RRID:AB_469576 |

| CD8 PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: 53-6.7] | eBioscience | Cat#A15385; RRID:AB_2534399 |

| B220 APC-eFluor 780; Anti-mouse [Clone: RA3-6B2] | eBioscience | Cat#47-0452-82; RRID:AB_1518810 |

| CD11b Alexa Fluor 488; Anti-mouse [Clone: M1/70] | eBioscience | Cat#53-0112-82; RRID:AB_469901 |

| CD41 PE; Anti-mouse [Clone: eBioMWReg30 ] | eBioscience | Cat#12-0411-82; RRID:AB_763485 |

| CD71 APC; Anti-mouse [Clone: R17217] | eBioscience | Cat#17-0711-82; RRID:AB_1834355 |

| CD45.2 APC-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: 104] | eBioscience | Cat#47-0454-82; RRID:AB_1272175 |

| CD61 APC; Anti-mouse [Clone: 2C9.G3] | eBioscience | Cat#17-0611-82; RRID:AB_2848288 |

| B220 BV510; Anti-mouse [Clone: RA3-6B2] | BD Horizon | Cat#563103; RRID:AB_2738007 |

| CD11b PE-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: M1/70] | eBioscience | Cat#25-0112-82; RRID:AB_469588 |

| CD11b eFluor 450; Anti-mouse [Clone: M1/70] | eBioscience | Cat#48-0112-82; RRID:AB_1582236 |

| Sca1 APC; Anti-mouse [Clone: E13-161.7] | BioLegend | Cat#122512; RRID:AB_756197 |

| c-kit APC-Cy7; Anti-mouse [Clone: ACK2] | BioLegend | Cat#135136; RRID:AB_2632809 |

| TotalSeq™-C Mouse Universal Cocktail, V1.0 | BioLegend | Cat#199903; RRID:AB_2924498 |

| TotalSeq™-C0098 anti-mouse CD135 [Clone: A2F10] | BioLegend | Cat#135321; RRID:AB_2832480 |

| TotalSeq™-C0857 anti-mouse CD34 [Clone: HM34] | BioLegend | Cat#128623; RRID:AB_2888791 |

| TotalSeq™-C0229 anti-mouse/rat CD62P [Clone: RMP-1] | BioLegend | Cat#148313; RRID:AB_2892302 |

| TotalSeq™-C0301 anti-mouse Hashtag 1 (Control) [Clone: M1/42; 30-F11] | BioLegend | Cat#155861; RRID:AB_155861 |

| TotalSeq™-C0302 anti-mouse Hashtag 2 (IC) [Clone: M1/42; 30-F11] | BioLegend | Cat#155863; RRID:AB_2800694 |

| Anti-ACSL4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-365230; RRID:AB_10843105 |

| Anti ferritin light chain (FTL) | abcam | Cat#ab109373; RRID:AB_10862715 |

| Anti ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) | abcam | Cat#ab65080; RRID:AB_10564857 |

| Anti actin | abcam | Cat#ab3280; RRID:AB_303668 |

| Anti Tip60 for CUT&RUN | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12058S; RRID:AB_2797811 |

| IgG control for CUT&RUN | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2729S; RRID:AB_1031062 |

| Anti-Ncoa4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-15984; RRID:AB_2151209 |

| Anti-Tip60 | Thermo Fisher | Cat#10827-1-AP; RRID:AB_2128431 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Deferoxamine mesylate salt | Sigma | Cat#D9533-1G |

| Deferoxamine Mesylate | Calbiochem | Cat#25275 |

| Eltrombopag | Novartis | N/A |

| 10058-F4 | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S7153 |

| TH1834 | Axon | Cat#2339 |

| SB 204990, ACLY inhibitor | Tocris | Cat#49-621-0R |

| Etomoxir | Sigma | Cat#E1905 |

| VPS34 | Reagency | Cat#RGNCY-0041/0042 |

| BODIPY 493/503 | Invitrogen | Cat#D3922 |

| BSA-arachidonate polyunsaturated fatty acid complex | Cayman Chemical | Cat#34931 |

| Diethylumbelliferyl phosphate | Sigma | Cat#D7692 |

| CD71-blocking antibody | Bio-Rad | Cat#MCA2396EL |

| Recombinant mouse SCF | R&D Systems | Cat#455-MC-050/CF; 455-MC-050 |

| Recombinant mouse TPO | R&D Systems | Cat#488-TO-025/CF; 488-TO-025 |

| Recombinant mouse IL-3 | R&D Systems | Cat#403-ML-050 |

| Recombinant mouse Flt3 Ligand | R&D Systems | Cat#427-FL-025 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| HSC007 methylcellulose media | R&D Systems | Cat#HSC007 |

| Trucount™ tubes | Becton Dickinson | Cat#663028 |

| Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer | Becton Dickinson | Cat#554714 |

| Lipi-Green | Dojindo | Cat#LD-02 |

| FeRhoNox-1 | Goryo Chemical | Cat#GC901 |

| MegaCult®-C medium | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#4960 |

| Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits | 10x Genomics | Cat#PN-1000268 |

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5’ Reagent Kit v2 | 10x Genomics | Cat#PN-1000265 |

| Mouse Transferrin ELISA kit | Abcam | Cat#ab157724 |

| Mouse Ferritin (FTL) ELISA kit | Abcam | Cat#ab157713 |

| CUT&RUN Assay Kit | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#86652 |

| Deposited data | ||

| scRNAseq of HSC with 48hours treatment with IC | This study | GSE157821 |

| CITE-seq of LSK cells from long-term intermittent treatment study | This study | GSE232022 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of HSPC isolated from young and old mice | Kowalczyk et al.153 | GEO: GSE59114 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of HSC isolated from young and old mice | Grover et al.91 | GEO: GSE70657 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of mouse bone marrow cells | Tabula Muris Consortium154 | GEO: GSE109774 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of human HSC isolated from young and old donors | Ainciburu et al.155 | GEO: GSE180298 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of activated versus quiescent mouse HSC | Fast et al.156 | GEO: GSE165844 |

| Single cell RNA-seq of activated versus label-retaining dormant mouse HSC | Cabezas-Wallscheid et al.157 | ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-4547 |

| Microarrays of mRNA composition from IRP1 and IRP2 immunoprecipitation | Sanchez et al.158 | GEO: GSE17096; GSE17097 |

| Expression profiling of Fbxl5-KO vs WT mouse HSC | Muto et al.66 | GEO: GSE93649 |

| ChIP-seq of Tip60 in mouse ESC | Ravens et al.159 | GEO: GSE69671 |

| Expression profiling of Tip60 KO vs WT mouse LSK | Numata et al.109 | GEO: GSE120705 |

| Expression profiling of c-Myc/N-Myc DKO vs WT mouse HSC | Laurenti et al.115 | GEO: GSE12538 |

| ChIP-seq of H2AZac in ESC | Hu et al.160 | GEO: GSE34483 |

| ChIP-seq of H2AZac in ESC | Ku et al.161 | GEO: GSE39237 |

| ChIP-seq of H4K5ac in ESC | Roadmap162 | GEO: GSE16256 |

| ChIP-seq of H4K8ac in ESC | Roadmap162 | GEO: GSE16256 |

| ChIP-seq of H4K12ac in ESC | Roadmap162 | GEO: GSE16256 |

| ChIP-seq of H4K16ac in ESC | Taylor et al.163 | GEO: GSE43103 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me1 in HSC | Lara-Astiaso et al.164 | GEO: GSE59636 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me1 in HPC7 cells | Org et al.165 | GEO: GSE47082 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me3 in HSC | Lara-Astiaso et al.164 | GEO: GSE59636 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me3 in LSK cells | Hasemann et al.166 | GEO: GSE43007 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me3 in HSC | Sun et al.167 | GEO: GSE47765 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K4me3 in LSK cells | Aranda-Orgilles et al.168 | GEO: GSE76055 |

| ChIP-seq of H3K36me3 in LSK cells | Adli et al.169 | GEO: GSE22075 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HPC-7 | Dr. Omar Abdel-Wahab, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center61 | RRID:CVCL_RB19 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57/BL6 mouse | Jackson Laboratories | stock number: 000664 |

| Pepc/BoyJ mouse | Jackson Laboratories | stock number: 002014 |

| beta-actin-GFP mouse | Jackson Laboratories | strain number: 006567 |

| CAGGCre-ER™ mouse | Jackson Laboratories | stock number: 004682 |

| Tip60LoxP mouse | Drs. Susumu Kobayashi and Daniel Tenen (Harvard Medical School)109 | N/A |

| Vav-iCre mouse | Jackson Laboratories | Stock No. 008610 |

| Fth1 mouse | Jackson Laboratories | Stock number: 018063 |

| Acsl4 mouse | Dr. Andrew Greenberg(Tufts University)170 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers | This study | Table S6 |

| TaqMan assays | This study | Table S6 |

| Tfrc smFISH probe | This study | Table S6 |

| pGFP-C-shLenti vector | OriGene | Cat#TR30021 |

| Short hairpin RNA targeting Acsl4 #3 | OriGene | Cat#TL502838C |

| Short hairpin RNA targeting Acsl4 #4 | OriGene | Cat#TL502838D |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo V10.2 | Becton Dickinson | https://www.flowjo.com/; RRID:SCR_008520 |

| FISHquant v2 | Imbert et al.171 | https://fish-quant.github.io/ |

| MATLAB R2020b | MathWorks | RRID:SCR_001622 |

| ELDA: Extreme Limiting Dilution Analysis | Hu et al. 172 | https://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/; RRID:SCR_018933 |

| Transcriptome Analysis Console 3.0 | Affymetrix | RRID:SCR_016519 |

| limma v3.54.0 | Ritchie et al.173 | DOI: 10.18129/B9.bioc.limma; RRID:SCR_010943 |

| NetworkAnalyst 3.0 | Zhou et al.174 | https://www.networkanalyst.ca/; RRID:SCR_016909 |

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | Qiagen | RRID:SCR_008653 |

| Cell Ranger v7.0.1 | 10x Genomics | RRID:SCR_017344 |

| Loupe Browser v6.4.0 | 10x Genomics | RRID:SCR_018555 |

| R v4.2.2 | R Core Team | https://www.R-project.org/; RRID:SCR_001905 |

| Seurat v4.3.0 | Satija et al.175 | https://satijalab.org/seurat/; RRID:SCR_007322 |

| escape v1.4.0 | Borcherding et al.176 | DOI: 10.18129/B9.bioc.escape |

| scVelo v0.2.5 | Bergen et al.177 | https://scvelo.readthedocs.io; RRID:SCR_018168 |

| velocyto.py v0.17.17 | La Manno et al.178 | https://velocyto.org/velocyto.py/; RRID:SCR_018167 |

| ImageJ 1.52r | Schneider et al.179 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; RRID:SCR_003070 |

| CellProfiler v4.2.1 | Stirling et al.180 | https://cellprofiler.org/; RRID:SCR_007358 |

| Wave v2.6.0.31 | Agilent | RRID:SCR_014526 |

| SRA Toolkit 2.10.7 | The NCBI | https://hpc.nih.gov/apps/sratoolkit.html; RRID:SCR_024350 |

| Salmon 1.2.1 | Patro et al.181 | https://combine-lab.github.io/salmon/; RRID:SCR_017036 |

| DESeq2 1.28.0 | Love et al.182 | https://github.com/mikelove/DESeq2; RRID:SCR_015687 |

| tximeta 1.6.2 | Love et al.183 | https://github.com/mikelove/tximeta |

| BioRender | BioRender.com | RRID:SCR_018361 |

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Protocol# 0000–1015). All procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Wild type as well as genetically modified mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (JAX) and housed in animal facilities at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; commercial strains included C57/BL6 (stock number 000664), Pepc/BoyJ (JAX stock number: 002014), beta-actin-GFP (JAX stock number: 006567), and Fth1flox mice (stock number: 018063). Acsl4LoxP mice were kindly provided by Dr. Andrew Greenberg (Tufts University) and crossed with Vav-iCre (JAX stock number: 008610) mice to generate Vav-iCre; Fth1LoxP mice. Tip60LoxP mice were kindly provided by Dr. Susumu Kobayashi (Harvard Medical School), and crossed with CAGGCre-ER™ (JAX stock number: 004682)100 mice to generate Cre-ER™; Tip60LoxP mice. Male and female mice at the age of 6–12 weeks (young) or 18–24 months (aged) were utilized for the experiments. For gene knockout experiments, Cre expression was induced by 4 consecutive, daily doses of tamoxifen of 0.2 mg/g body weight of tamoxifen by oral gavage.

Cell lines

HPC-7 cells were passaged in IMDM with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% sodium pyruvate, 6.9 ng/mL monothioglycerol (Sigma) and 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse (rm) SCF.133 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin.

Primary cell culture

Primary HSC and progenitor cells were isolated by cell sorting on a Moflo Astrios EQ (Beckman Coulter). Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48− (HSC) or Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−CD34− (CD34−HSC) populations were cultured in Myelocult M5300 (STEMCELL Technologies) with 100 μg/ml Primocin (Invivogen) supplemented with 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse (rm) SCF (R&D Systems) and 50 ng/ml rmTPO (R&D Systems). For lineage-negative (Lin−) and Lin−c-kit+ (LK) cells, 50 ng/ml of rmSCF and rmTPO were used, with 20 ng/ml rmIL-3 (R&D Systems), 50 ng/ml Flt3-Ligand (R&D Systems) supplemented to the culture. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 unless otherwise specified. HPC-7 cells were passaged in IMDM with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% sodium pyruvate, 6.9 ng/mL monothioglycerol (Sigma) and 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse (rm) SCF.133 BA/F3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, 2 ng/ml rmIL-3 and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.134 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 unless otherwise specified.

Methods Details

Chemicals and Reagents

Eltrombopag (EP, pure compound provided by Novartis) was reconstituted in sterile distilled water as 1 mg/ml stock and was stored at ambient temperature, light-protected for up to 2 weeks. Deferoxamine (DFO, Sigma) was freshly prepared with sterile distilled water for every experiment. Etomoxir (Sigma) was stored at −20°C in aliquots of 10 mM stocks. Inhibitors for VPS34 (RGNCY-0041/0042, Reagency), Myc (10058-F4, Selleck) and Tip60 (TH1834, Axon) were reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −80°C until use. Iron chemo-sensors FeRhoNox-1 (Goryo Chemical) were stored light-protected at −20°C and were freshly reconstituted in DMSO for every experiment. ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) inhibitor SB 204990 (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) was reconstituted in DMSO with a stock concentration of 10 mM and stored at −80°C until use. BSA-arachidonate polyunsaturated fatty acid complex (Cayman Chemical) is composed of arachidonic acid and bovine serum albumin (BSA), at a 6:1 molar ratio of arachidonate:BSA and stored with a stock concentration of 1 mM and stored at −20°C until use.

Models for acute iron limitation

Ex vivo acute iron limitation

Murine HSPC were freshly isolated from bone marrow and FACS purified based on cell surface markers against lineage, Sca1 and c-Kit. LSK (Lin− Sca1+ c-kit+) cells were cultured in Myelocult M5300 based conditioned media, supplemented with recombinant thrombopoietin (TPO, 50 ng/ml), SCF (50 ng/ml) and hydrocortisone (1 μM), as we have previously described (LTC-IC media).21 Limiting dilutions of LSK cells were incubated with iron chelators such as deferoxamine (10 μM, Sigma) and eltrombopag (10 μg/ml , Novartis) for 48 hrs to elicit an acute iron limitation response. Cells were re-cultured in the absence of chelators for 4 weeks in LTC-IC media followed by a 1-week culture in complete methylcellulose media (HSC007, R&D). Long-term stem and progenitor cell function is read out as the number of LTC-IC units as predicted by Poisson statistics.135

Acute iron limitation in vivo

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Protocol# 0000–1015). All procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Young (2–3 months) and aged (20–22 months) mice were given one dose of deferoxamine (Calbiochem) daily for 14 consecutive days. Vehicle (HBSS) or iron chelator were administered through intraperitoneal injection at 50 mg per kilogram of body weight. Animals were weighed before and after the 14-day treatment regimen, no noticeable changes to body weight were found. Complete blood count (CBC) was performed before and after treatment to monitor changes in blood parameters. Blood sera were subjected to ferritin and transferrin measurements using the ELISA assay kits (Abcam) to monitor changes in systemic iron level.

Long-term intermittent iron chelation in vivo

Young mice (6 months) were subjected to either vehicle (HBSS) or deferoxamine (Calbiochem) daily for 5 consecutive days every 4 weeks for a period of 13 months. Dosing and route of drug delivery used were as described in the in vivo acute iron limitation model. Body weights were monitored every 4 weeks and blood were drawn for CBC every 2 months. Experimental mice were at least 19 months old at the time of sacrifice. The labile iron pool size in phenotypical HSPC was measured using FeRhoNox-1 (Goryo Chemical).

Iron chelation in activated Tip60d/wt HSC in vivo

Tip60d/wt mice of 2–3 months old were assigned randomly into lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or control treatment groups and subjected to either continuous low dose of LPS (0.1μg per g of body weight) or vehicle (HBSS) injection intraperitoneally 3 times per week for 10 weeks. Mice from the LPS cohort were randomly selected to receive deferoxamine (Calbiochem) daily for 14 consecutive days every 4 weeks for 10 weeks. Mice receiving iron limitation protocol were put on deferoxamine (50mg per kilogram of body weight) for 14 days before subjected to continuous LPS challenge.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting

Cell preparation and sorting.

Isolation of mononuclear cells (MNC) from mouse bone marrow was performed as previously described.21 Briefly, MNC were lineage-depleted using 1:200 dilution of anti-mouse CD4, CD8, B220, CD19, Ter119 and Gr-1, all biotin-conjugated, rotating at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed and then stained with triple-washed anti-IgG magnetic beads (Untouched Mouse T Cells Kit, Thermo Fisher) rotating at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed and then depleted of lineage-positive cells by passing through a magnetic separation column (MACS LD Column, Miltenyi Biotec) loaded on a DynaMag-5 Magnet (Invitrogen). Lineage-negative cells were then stained for 30 min on ice with stem and progenitor cell markers (Sca-1, c-Kit, CD150, CD48, CD34; 1:100). A detailed description of mouse antibodies can be found in Table S6. Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48− (HSC) or Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−CD34− (CD34−HSC) and Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells were sorted on MoFlo Astrios EQ (Beckman Coulter).

Absolute cell counting.

Quantification of absolute numbers of hematopoietic cell lineage populations in peripheral blood was performed with Trucount™ tubes (BD) following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μL of blood was transferred to Trucount™ tubes by reserve pipetting, and 10 μL of antibody mix was carefully added to the tube without touching the beads pellet. After gentle mixing, cells were incubated with bead and antibody mix for 15 minutes in the dark at RT. Thereafter, 450μL of 1X BD FACS lysing solution was added for 15 minutes in the dark at RT before FACS analysis. A total of 5000–10,000 beads were recorded on BD FACS Aria II (Becton Dickinson) for absolute quantification of lineage output. The absolute cell number per μL of blood was calculated by:

Quantification of Hadha.

For primary cells, lineage-depleted MNC were treated with iron chelators (10 μM DFO) for 24 hours, followed by staining with FACS antibodies against surface markers for HSPC. Thereafter, stained cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer for 20 min on ice. For HPC7, cells were treated with iron chelators (10 μM DFO or 5 μg/ml EP) for 24 hours before fixation and permeabilization with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer. Intracellular staining with anti-Hadha antibody (abcam, ab203114) for 1 hour at RT, followed by secondary staining with Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen, A21245) for 30 min at RT.

Quantification of lipid droplet.

Lineage-depleted MNC were cultured in the presence of iron chelator (10 μM DFO) or vehicle (ddH2O) for 4 hours, followed by incubation with 1 μM of Lipi-Green (LD-02, Dojindo) for 30 min. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the culture and labelling of lipid droplets. Thereafter, Lipi-Green labeled cells were washed with PBS, incubated with antibody cocktail for HSPC surface staining for 30 min on ice, light protected. Cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to FACS analysis. Unless otherwise specified, fluorescent signals were acquired with BD FACS Aria II system (Becton Dickinson) and analysed with FlowJo V10.2.

Quantification of labile iron pools.

Intracellular iron levels were also measured with FeRhoNox-1 fluorescent imaging probe specific for ferrous iron (Goryo Chemical). For primary cells, lineage-depleted MNC were incubated with 20 μM FeRhoNox-1 at 37°C for 1 hour. Antibody cocktail for HSPC surface staining was added in the last 10 min of FeRhoNox-1 incubation. For HPC-7, cells were pre-treated with VPS34 inhibitor (Reagency, RGNCY-0042) for 2 hours before exposure to vehicle or iron chelator (10 μg/ml eltrombopag) for 1 hour at 37°C. Thereafter, treated cells were washed with PBS, and incubated with 20 μM FeRhoNox-1 at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to FACS analysis. Unless otherwise specified, fluorescent signals were acquired with BD FACS Aria II system (Becton Dickinson) and analysed with FlowJo V10.2.

Single molecule RNA FISH

To design Tfrc mRNA-specific probes for sequential single molecule FISH (smFISH), full length transcript of Tfrc (NM_011638) was used as input for PaintSHOP136 to retrieve 22 primary targeting sequences (30–40bp, Table S6), separated by at least 10bp. Putative sequences were then screened for off-target activity using NCBI Blast (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against mouse transcriptome. Selected sequences were then concatenated on the 5′ and 3′ end with flanking readout 20mer sequences (GTTTGAAGATTCGACCTGGA), generating a final ‘primary probe’. SmFISH immunofluorescence staining procedure and analysis were performed as described previously.48,137 Briefly, treated and control cells were attached to coverslips using biotinylated anti-CD44 coating.138 Residual media was washed with PBS, and cells were fixed in 3.2% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences), diluted in PBS with 1 mM MgCl2 (PBSM), for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBSM for 10 minutes. After washing with PBSM, cells were incubated at room temperature with 30% prehybridization buffer (30% formamide, 2X saline-sodium citrate buffer) for 30 minutes. Primary hybridization was done in 30% hybridization buffer consisting of 10% dextran sulfate, 30% formamide, 2X saline-sodium citrate (SSC), 2 mM VRC, 10 μg/ml sheared ssDNA from salmon sperm, 10 μg/ml E. coli tRNA, 10 μg/ml molecular grade bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 200 ng of primary probe mixes, overnight at 37 °C. Thereafter, cells were washed twice with 30% pre-hybridization buffer for 20 min at 37 °C and once with 2X SSC. Cells were then post fixed in 3.2% PFA in PBSM for 10 min, followed by washing in 2X SSC. Primary stained cells were incubated with 10% prehybridization buffer (10% formamide, 2X SSC) for 10 min at 37 °C and stained with 10% dextran sulfate, 10% formamide, 2X SSC, 2 mM VRC, 10 μg/ml sheared ssDNA from salmon sperm, 10 μg/ml E. coli tRNA, 10 μg/ml molecular BSA, and 10 ng Cy5-labelled readout probe of 20mer readout probe (RO2-Cy5) for Tfrc gene for 3 hrs at 37 °C. Cells were then washed twice for 10 min in 10% prehybridization buffer, followed by a final wash in 2X SSC. Before the immunostaining for pS10H3, cells were again fixed with 3.2% PFA in PBS for 10 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were washed once with PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Blocking was performed in blocking buffer (PBS, 1% RNAse-free BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 30 min at room temperature. Next, cells were incubated with the primary antibody (1:200 mouse anti-pS10H3, Cell Signaling Technology) in antibody dilution buffer (PBS, 0.1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100) overnight at 4°C. On the next day, cells were washed thrice with PBS for 5 min at RT before incubation with the secondary antibody (1:200 rabbit anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488, Cell Signaling Technology) in antibody dilution buffer for 1 hour at RT. Excess antibody was removed by washing cells with 1xPBS for 5 min at RT. Cells were then mounted in Prolong Diamond Antifade reagent plus DAPI (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using oil immersion 100X objective on an epifluorescence Olympus Digital Station 6 microscope. Exposure times were 1000 ms, 50 ms, 100 ms for Cy5, AlexaFluor 488 and DAPI respectively. Z stacks spanning the entire volume of the cells were acquired by imaging every 300 nm along the z-axis. Acquisition control of the microscope was achieved using IPLab software. For data analysis, single molecule mRNA and transcription site detection was performed using freely available and MATLAB-written software FISHquant, by 3D Gaussian fitting of thresholded spots, implemented in MATLAB R2020b.138 Further experimental details, validation, and discussion of this methodology in the hematopoietic system can be found in Wheat et al.48.

Stroma-free long-term culture-initiating cell assay