Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To summarize the effectiveness of implementation strategies for ICU execution of recommendations from the 2013 Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium (PAD) or 2018 PAD, Immobility, Sleep Disruption (PADIS) guidelines.

DATA SOURCES:

PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from January 2012 to August 2023. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020175268).

STUDY SELECTION:

Articles were included if: 1) design was randomized or cohort, 2) adult population evaluated, 3) employed recommendations from greater than or equal to two PAD/PADIS domains, and 4) evaluated greater than or equal to 1 of the following outcome(s): short-term mortality, delirium occurrence, mechanical ventilation (MV) duration, or ICU length of stay (LOS).

DATA EXTRACTION:

Two authors independently reviewed articles for eligibility, number of PAD/PADIS domains, quality according to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute assessment tools, implementation strategy use (including Assess, prevent, and manage pain; Both SAT and SBT; Choice of analgesia and sedation; Delirium: assess, prevent, and manage; Early mobility and exercise; Family engagement and empowerment [ABCDEF] bundle) by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) category, and clinical outcomes. Certainty of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

Among the 25 of 243 (10.3%) full-text articles included (n = 23,215 patients), risk of bias was high in 13 (52%). Most studies were cohort (n = 22, 88%). A median of 5 (interquartile range [IQR] 4–7) EPOC strategies were used to implement recommendations from two (IQR 2–3) PAD/PADIS domains. Cohort and randomized studies were pooled separately. In the cohort studies, use of EPOC strategies was not associated with a change in mortality (risk ratio [RR] 1.01; 95% CI, 0.9–1.12), or delirium (RR 0.92; 95% CI, 0.82–1.03), but was associated with a reduction in MV duration (weighted mean difference [WMD] −0.84 d; 95% CI, −1.25 to −0.43) and ICU LOS (WMD −0.77 d; 95% CI, −1.51 to 0.04). For randomized studies, EPOC strategy use was associated with reduced mortality and MV duration but not delirium or ICU LOS.

CONCLUSIONS:

Using multiple implementation strategies to adopt PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations may reduce mortality, duration of MV, and ICU LOS. Further prospective, controlled studies are needed to identify the most effective strategies to implement PAD/PADIS recommendations.

Keywords: critical care, delirium, implementation, intensive care, pain, practice guidelines, sedation

Adult ICU patients frequently experience pain, agitation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption (PADIS) (1–6). These interrelated conditions are foundational to the postintensive care syndrome and remain of great concern to patients, their families, and clinicians well after ICU discharge (7, 8). In 2013, the Society of Critical Care Medicine published clinical practice guidelines addressing the recognition, prevention, and management of pain, agitation, delirium (PAD). Updated 2018 guidelines were expanded to also include ICU immobility and sleep disruption (PADIS) (9, 10).

Although the PAD/PADIS clinical practice guidelines provide more than 40 evidence-based recommendations, patient-centered outcomes may not be improved unless robust implementation strategies are used to facilitate clinical practice change focused on routine recommendation adoption (9, 10). Unfortunately, widespread application of best practice recommendations as a standard-of-care clinical practice model often does not reach anticipated goals. Successful guideline recommendation implementation requires overcoming multiple barriers including organizational constraints, a lack of dedicated resources as well as trained personnel to support practice change, and instilling a paradigm shift in the acceptance and behavior of key stakeholders (11, 12). In particular, the implementation of the PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations necessitates a highly comprehensive, coordinated strategy involving multiple aspects of the interprofessional critical care practice model, such as a bundled approach to target multiple aspects of these recommendations (13, 14).

The ICU liberation bundle provides an evidence-based framework to promote an interprofessional, coordinated approach to daily PAD/PADIS recommendation use. This bundle and several other strategies have been used to implement PAD/PADIS recommendations in the ICU (13, 15–18). However, limited data exists in published reports on the relationship between the specific number as well as types of implementation strategies used and the impact on relevant ICU outcomes. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to summarize the number and types of strategies used to implement PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations and evaluate the impact on ICU patient outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis 2020 statement (Supplemental Digital Content [SDC] 1; Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) (19). The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42020175268).

Eligibility Criteria

Study eligibility for inclusion consisted of the following criteria: 1) the study design was either a randomized trial, quasi-experimental or cohort/case–control study (referred to as cohort studies for the rest of the article), 2) study population consisted of adult (≥ 18 yr) patients admitted to the ICU, 3) the intervention group used recommendations from greater than or equal to two PAD/PADIS domains (i.e., pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption) or the ICU liberation bundle (9, 10), 4) the comparator group did not have a clearly defined implementation strategy for PAD/PADIS element recommendations (note: nonprotocolized pain and/or sedation therapy was allowed), 5) the study intervention incorporated greater than or equal to 1 of 17 Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) implementation taxonomy implementation strategies (SDC 2, Supplemental Table 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) (7–10, 20), 6) reported outcomes included greater than or equal to 1 of the following: short-term mortality, days of mechanical ventilation (MV) (or days without), ICU days with delirium (or days spent without), and ICU length of stay (LOS). Exclusion criteria included: 1) studies only available as an abstract, 2) full-text articles published in non-English languages, and 3) studies evaluating patients in non-ICU areas such as step-down units or long-term care hospitals.

The study eligibility criteria are presented in SDC 3, Supplemental Table 3 (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Short-term mortality was defined as death within 45 days of ICU admission (21). Using a 45-day window provides information about how the implementation of the PAD/PADIS domains impacts the survival of the patients throughout hospital admission.

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, CINAHL on the EBSCO platform, Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and Web of Science (Clarivate, London, United Kingdom) from January 1, 2012 (the PAD guidelines became publicly available in early 2012) to August 7, 2023, with an English language restriction (SDC 4, Supplemental Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). The strategy retrieved the cited reference articles for the PAD/PADIS guidelines, along with those of the executive summaries. An additional search within the acquired reference’s listed citations in Scopus was completed to identify any additional articles. The MEDLINE database was searched using Boolean Logic with both text words and medical subject headings-controlled vocabulary to retrieve studies that referenced PAD/PADIS implementation but were too new to be cited. The Web of Science database allowed us to identify relevant proceedings papers, conference papers, and meeting abstracts. All retrievals were downloaded to an EndNote Library (Clarivate) and duplicates were removed. Due to a university’s decision not to relicense Scopus, the search omitted it from January 15, 2021, to August 7, 2023. A research librarian (M.K.F.) with a healthcare background designed and executed all searches.

Data Collection and Analysis

Reference screening and data extraction were completed using DistillerSR (Version 2.43.0) Distiller SR; 2022 (https://www.distillersr.com). Two reviewers (N.H., I.Z.) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies, and then evaluated full-text articles for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (S.K.G.) when necessary. The same two reviewers (N.H., I.Z.) independently and in duplicate, used a predesigned data abstraction form to extract data on study design, study environment, patient population, PAD/PADIS domains implemented, EPOC implementation strategies used, outcomes, and other relevant information. When multiple study periods were included within the study, data were preferentially collected between baseline (i.e., no formal implementation) and the period when full implementation was completed. Missing or unclear information was reported as “not reported.” Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and included a third reviewer (S.K.G.) as necessary. Authors were not contacted for missing data given the studies were all pre-post cohort analyses.

Methodological Quality

Risk-of-bias/study quality for observational cohort and cross-sectional, and before-after (pre-post) studies was assessed using Study Quality Assessment Tools from the National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute (SDC 5 and 6, Supplemental Appendices 2 and 3, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) (22). Randomized controlled trials were evaluated using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (SDC 7, Supplemental Appendix 4, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) (23). Two reviewers (N.H., I.Z.) independently assessed risk of bias, and disagreements over risk of bias and quality assessment were resolved by discussion. A third reviewer (S.K.G.) resolved discrepancies through discussion.

Statistical Analysis

Effectiveness of PAD/PADIS guideline implementation was assessed using appropriate statistical tests to determine whether outcomes significantly improved following implementation. The primary outcome was short-term mortality, which was evaluated using a risk ratio (RR). Secondary outcomes were evaluated using a weighted mean difference (WMD), or RR, as appropriate. Data from randomized and cohort studies for each outcome were evaluated separately. Given the expected heterogeneity in outcomes evaluated in the studies, a random effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was used for analyses (24). Inverse-variance weights were used to weigh studies by sample size. When continuous data were only presented as a median, the sample mean was estimated based on the provided median and interquartile range (IQR) (25). Publication bias was evaluated via examination of funnel plots (SDC 8, Supplemental Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) (26). A two-sided p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with STATA (version 18) (STATA Statistical Software; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Heterogeneity, Subgroup Analysis, and Certainty

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and by visual inspection of forest plots, with an I2 greater than 50% suggesting substantial heterogeneity (27). In cases of substantial heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed using meta-regression to evaluate for potential effect modification. Subgroup analyses for the primary outcome, developed a priori, including type of ICU (only medical vs. other), and use of the Assess, prevent, and manage pain; Both SAT and SBT; Choice of analgesia and sedation; Delirium: assess, prevent, and manage; Early mobility and exercise; Family engagement and empowerment (ABCDEF) bundle. Based on a median of five EPOC strategies used among the included studies, a subgroup analysis compared all outcomes between studies using greater than or equal to five (vs. < 5) EPOC strategies. A post hoc analysis included a subgroup analysis evaluating the number of PADIS domains evaluated by the intervention (two vs. three or more). These subgroup analyses were performed only with data from cohort studies, given only three (12%) of the included articles were randomized trials. Certainty of evidence for each outcome was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (28).

RESULTS

Study Identification and Characteristics

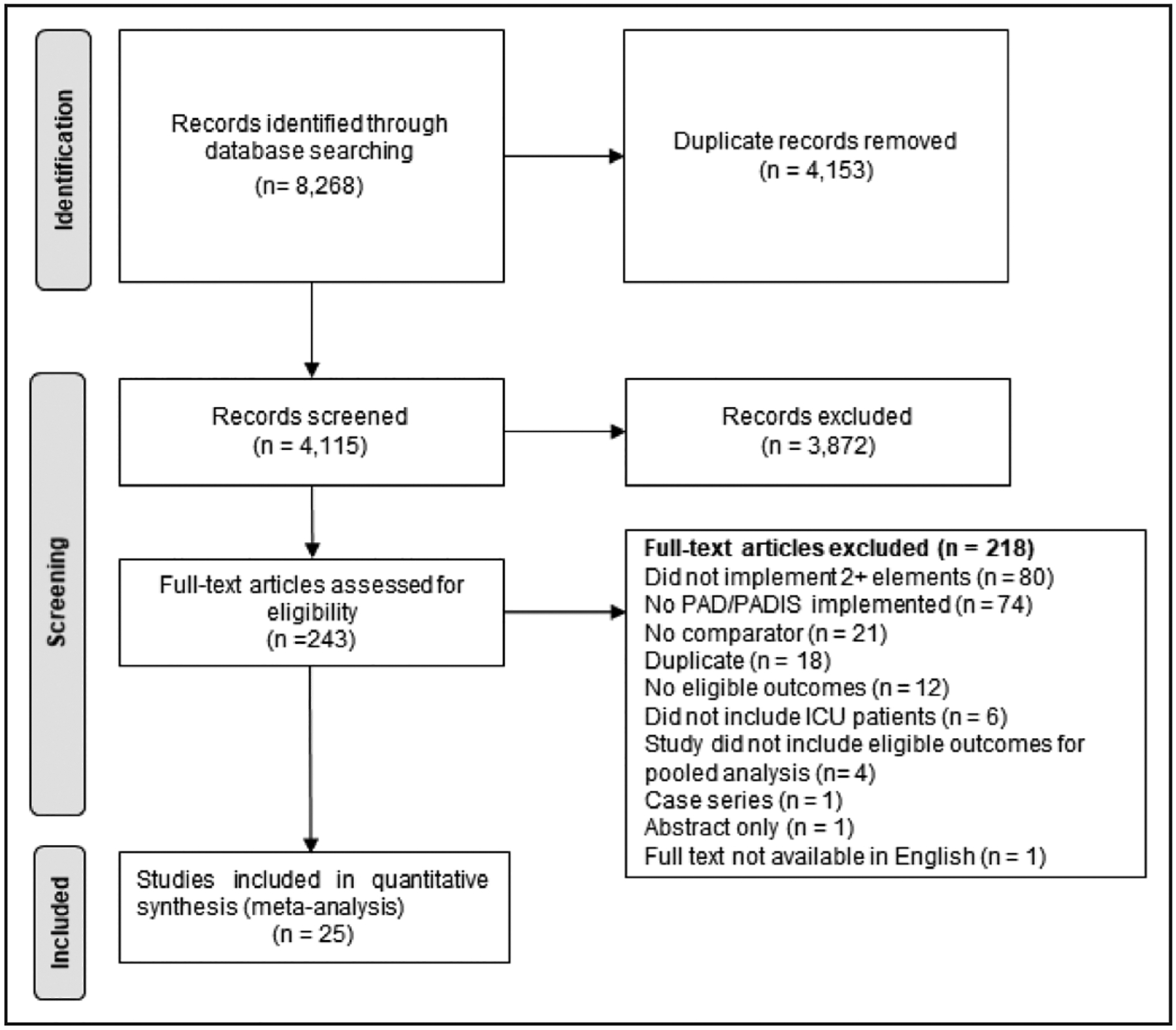

Our literature searches identified 8268 citations. Among the 4115 citations remaining after removal of duplicates, 243 articles were selected for full-text review with 218 articles being excluded (Fig. 1). A total of 25 studies involving 23,215 patients (12,459 and 10,756 in the intervention and control groups, respectively) met our meta-analysis inclusion criteria (29–53). Three studies had a randomized study design (31, 32, 52).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. PAD = Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, PADIS = PAD, Immobility, Sleep disruption.

Characteristics of the 25 included studies are summarized in SDC 9, Supplemental Table 4 (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Academic medical centers represented 84% of all patients included in our meta-analysis with the most common ICU type being the medical ICU (44% of patients). Forty percent of these studies included only mechanically ventilated patients. Baseline severity of illness was not reported in 52% of the studies; among those that did, severity of illness was variable. The median number of PAD/PADIS guideline elements reported per study was two (IQR 2–3). The median number of EPOC strategies used per study was 5 (IQR 4–7). Although all included studies incorporated at least one EPOC professional and one organizational intervention strategy, only one study adopted an EPOC financial incentive; no studies used an EPOC regulatory-based strategy (SDC 10, Supplemental Table 5, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). The most commonly used EPOC strategies among the included studies were educational meetings (92%), provider-oriented methods (88%), local opinion leader input (72%), and educational materials (68%). Ten studies specifically used the ABCDE(F) bundle. Study data for each outcome are presented in SDC 11, Supplemental Table 6 (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478).

Study Quality

The risk of bias for all included studies is summarized in SDC 5, 6, and 7 (Supplemental Appendices 2, 3, and 4, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Thirteen studies had a high risk of bias, whereas two studies were determined as low risk of bias. The remaining studies (n = 10) were found to have moderate bias risk. The most common sources of bias were a lack of blinding, study intervention adherence, time series utilization, and power calculation to determine study sample size adequacy. Among the pre-post studies (n = 21), risk of bias associated with the intervention equity (i.e., the study intervention was clearly described and consistently delivered to study participants) was low in ten studies, high in six studies, and unclear in five. The GRADE certainty assessments are summarized in SDC 12, Supplemental Table 7 (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478).

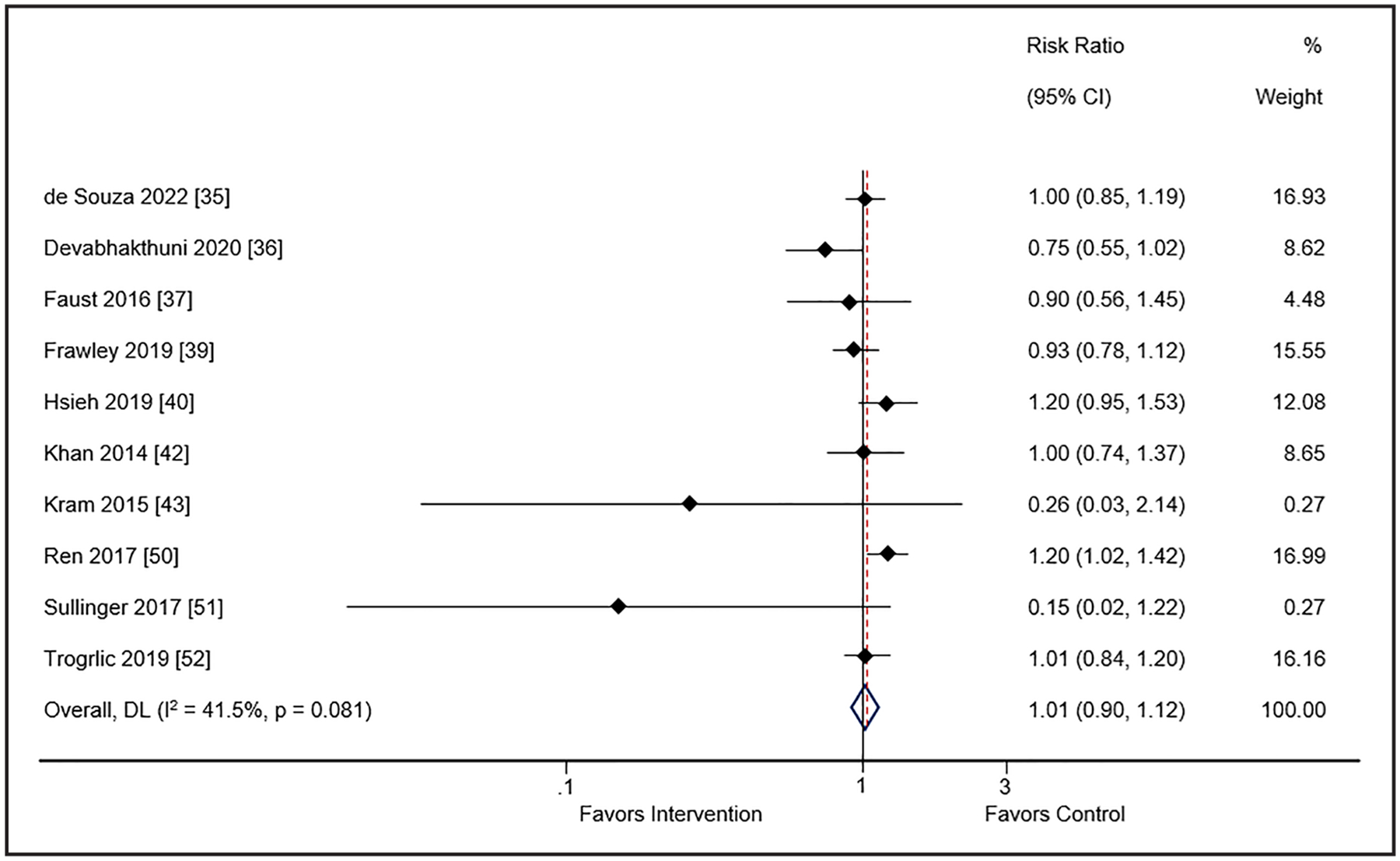

Short-Term Mortality

Thirteen studies (n = 8 pre-post, n = 2 cohort, n = 3 randomized) involving 17,625 patients reported short-term mortality (31, 32, 34–36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 49–52). For the cohort studies, there was no difference in short-term mortality between the intervention and comparator groups (RR 1.01; 95% CI, 0.9–1.12; I2 = 41.5%; low certainty of evidence) (Fig. 2). However, for the randomized trials a decrease in short-term mortality was found (RR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.71–0.89; I2 = 0%; low certainty of evidence) (SDC 13, Supplemental Fig. 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Subgroup analyses with cohort studies for type of ICU (only medical ICU vs. other) (SDC 14, Supplemental Fig. 3, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478), use of the ICU liberation bundle (SDC 15, Supplemental Fig. 4, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478), using greater than or equal to 5 (vs. <5) EPOC strategies (SDC 16, Supplemental Fig. 5, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478), and number of PADIS domains (two vs. greater than two) (SDC 17, Supplemental Fig. 6, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) were also not associated with a reduction in short-term mortality.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis and pooled effect sizes for short-term mortality for implementation intervention(s) compared with usual care in cohort studies. DL = DerSimonian and Laird method.

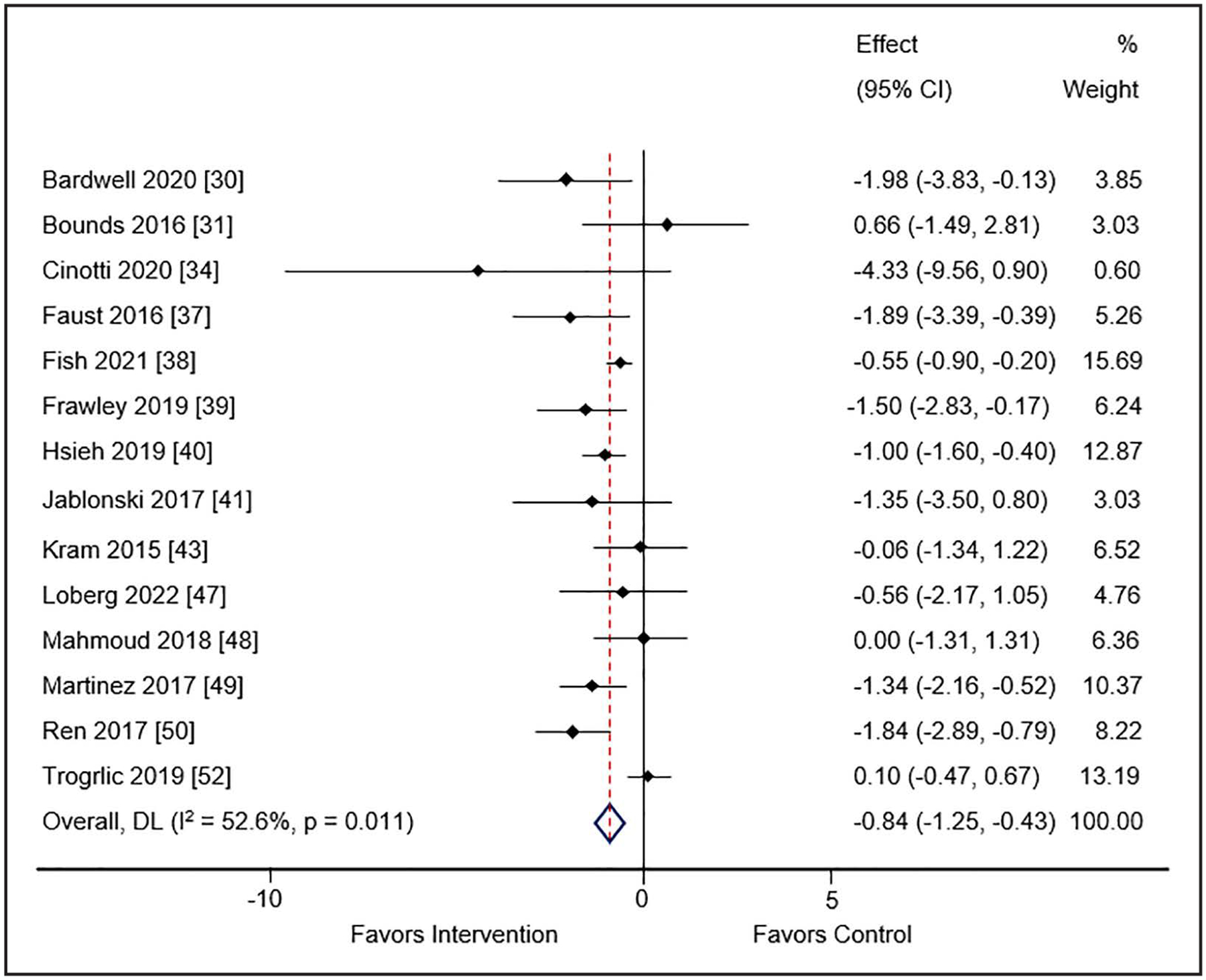

Duration of Mechanical Ventilation

Sixteen studies (n = 13 pre-post, n = 1 observational cohort, n = 2 randomized) enrolling 16,544 patients reported the duration (d) of MV (29, 30, 32, 33, 36–40, 42, 46–49, 51, 52). Use of the guideline implementation intervention(s) compared to usual care was associated with reduced days of MV in both the cohort (WMD −0.84; 95% CI, −1.25 to −0.43; I2 = 52.6%; low certainty of evidence) (Fig. 3) and randomized (WMD −1.32; 95% CI, −2.39 to −0.26; I2 = 90.1%; low certainty of evidence) (SDC 18, Supplemental Fig. 7, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) trials. Subgroup analysis with cohort studies of duration of MV was not affected by number of EPOC interventions (SDC 19, Supplemental Fig. 8, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478) or number of PADIS domains (SDC 20, Supplemental Fig. 9, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Use of meta-regression did not find a characteristic that accounted for the substantial heterogeneity among studies for this outcome (SDC 21, Supplemental Table 8, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis and pooled effect sizes for days of mechanical ventilation for implementation intervention(s) compared with usual care in cohort studies. DL = DerSimonian and Laird method.

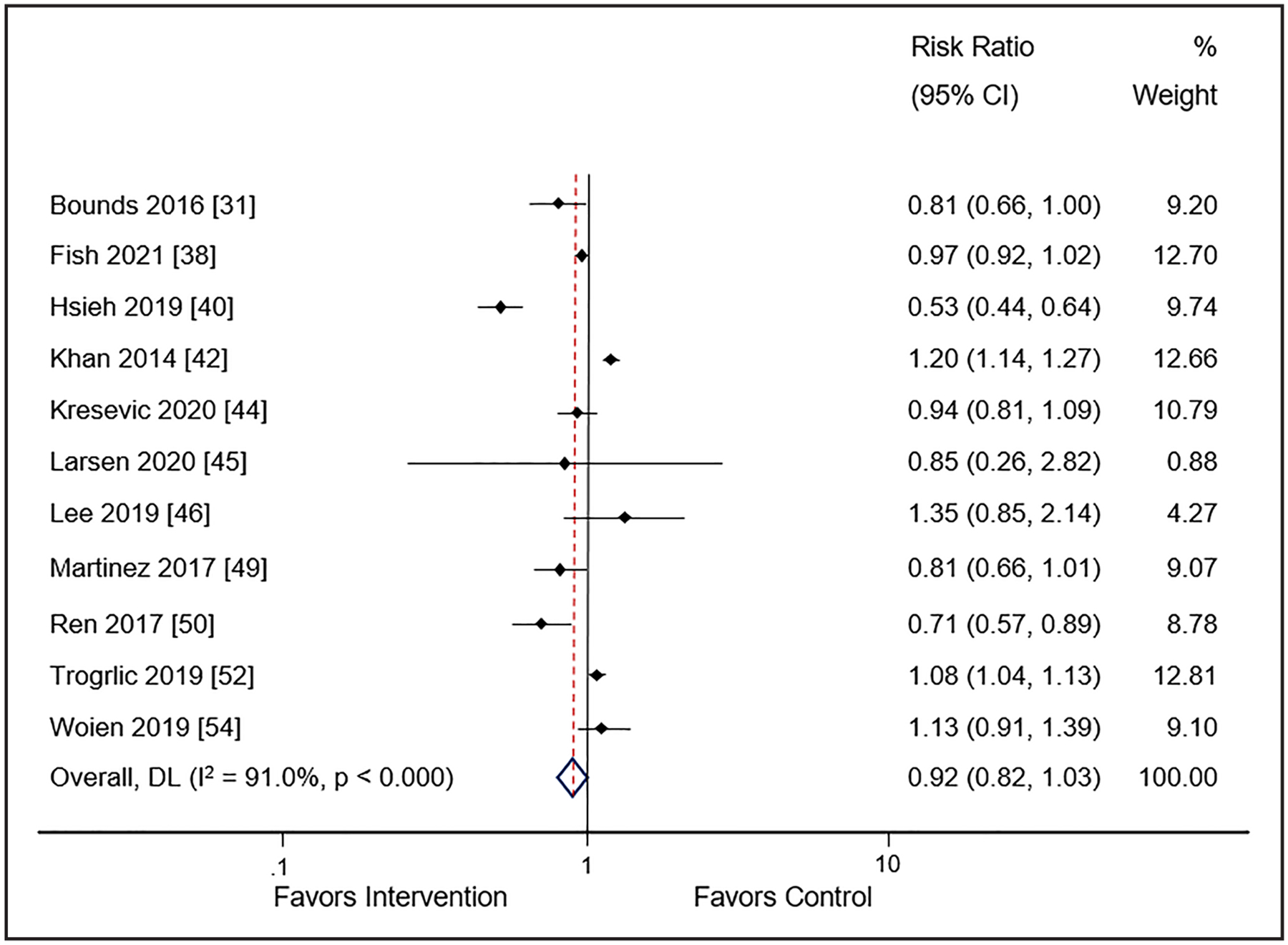

Delirium Occurrence

Delirium occurrence (i.e., days spent with [or without] was reported in 13 studies [n = 10 pre-post, n = 1 observational cohort, n = 2 randomized]) enrolling 10,748 patients (30, 31, 37, 39, 41, 43–45, 48, 49, 51–53). Use of the guideline implementation intervention(s) was not associated with a reduction in delirium occurrence in either the cohort studies (RR 0.92; 95% CI, 0.82–1.03; I2 = 91%; low certainty of evidence) (Fig. 4) or the randomized trials (RR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89–1.00; I2 = 36.1%; low certainty of evidence) (SDC 22, Supplemental Fig. 10, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). There was no difference in delirium occurrence by number of EPOC interventions (SDC 23, Supplemental Fig. 11, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). All studies included at least three PADIS domains so no subgroup analysis was completed. Use of meta-regression did not identify a characteristic that accounted for the substantial heterogeneity among studies for this outcome (SDC 24, Supplemental Table 9, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis and pooled effect sizes for delirium occurrence for implementation intervention(s) compared with usual care. DL = DerSimonian and Laird method.

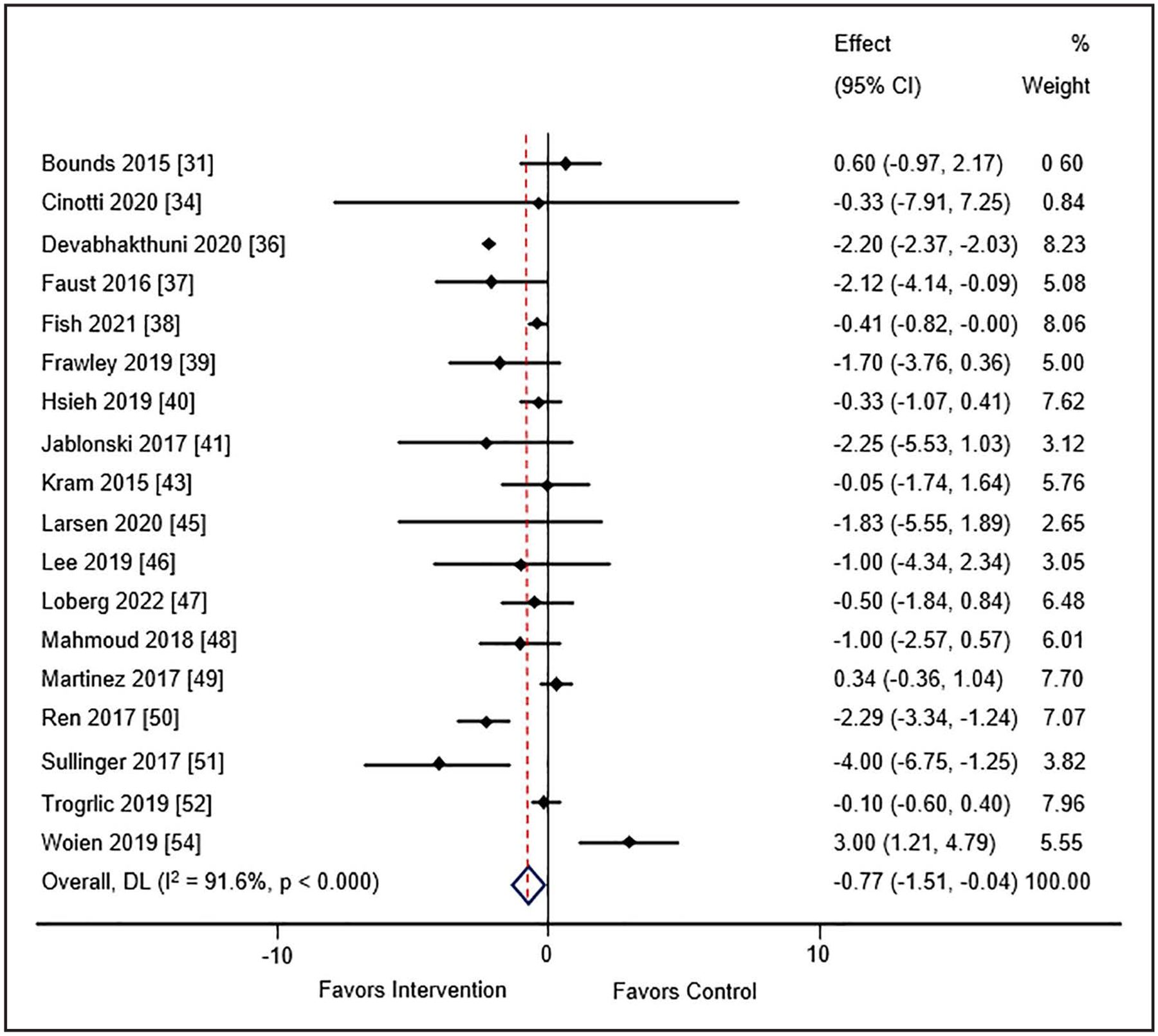

ICU Length of Stay

Twenty-one studies (n = 17 pre-post, n = 1 observational cohort, n = 3 randomized) consisting of 19,942 patients (30–33, 35–40, 42, 44–53) evaluated ICU LOS. Use of guideline implementation strategies was associated with decreased ICU LOS in cohort studies (WMD: −0.77; 95% CI, −1.51 to −0.04; I2 = 91.6%; very low certainty of evidence) (Fig. 5). However, this benefit of implementation was not associated with a decrease in ICU LOS in the randomized trials (WMD: −0.50; 95% CI, −1.05 to 0.06; I2 = 93.3%; very low certainty of evidence) (SDC 25, Supplemental Fig. 12, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). With this very low certainty of evidence, the relationship between implementation strategy use of ICU LOS remains unclear. For the cohort studies, ICU LOS was significantly reduced in studies using one to four EPOC strategies (WMD −1.27; 95% CI, −2.25 to −0.30; I2 =90.7%); significance was lost when studies using greater than or equal to five strategies were compared (WMD −0.22; 95% CI, −0.92 to 0.47; I2 = 64.6%) (SDC 26, Supplemental Fig. 13, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). The subgroup analysis by number of PADIS domains found a significant reduction in ICU LOS with implementation strategies (SDC 27, Supplemental Fig. 14, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478). Use of meta-regression did not identify a characteristic that accounted for the substantial heterogeneity among studies for this outcome (SDC 28, Supplemental Table 10, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H478).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis and pooled effect sizes for ICU length of stay for implementation intervention(s) compared with usual care. DL = DerSimonian and Laird method.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first published report evaluating the clinical impact of the number and types of intervention strategies used to implement PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations into ICU clinical practice. Our meta-analysis including a wide variety in the number and types of implementation strategies, and research designs, found approaches aimed at the implementation of greater than or equal to two elements of the PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations may be associated with reductions in short-term mortality, duration of MV, and ICU LOS. However, the degree of heterogeneity we report for all pooled estimates is high. Furthermore, all evidence was deemed to be of either low or very low certainty. Therefore, our ability to make strong conclusions about the impact of intervention strategy(s) use and on each of the clinical outcomes considered remains limited.

The number of implementation strategies that should be delivered for PAD/PADIS recommendations remains unclear. The number of implementation strategies used does not appear to influence short-term mortality or delirium occurrence. However, the clinical impact of implementing PAD/PADIS recommendations on MV duration was independent of the number of intervention strategies used. The number of intervention strategies used was found to be inversely associated with ICU LOS. Clearly more research is needed on the number and types of implementation strategies that should be used when adopting PAD/PADIS recommendations in the ICU.

Four published meta-analyses evaluating the impact of bundled interventions grounded in PAD/PADIS recommendations on ICU clinical outcomes used a narrower assessment than ours by either only evaluating one PAD/PADIS domain or not including implementation strategies besides the ICU liberation bundle (18, 54–56). Trogrlić et al (18) completed a meta-analysis of 21 studies that assessed one domain of the PAD, specifically delirium, but provided an expansive appraisal of implementation strategies for delirium screening, prevention and management with consideration to process, and clinical outcomes. This group noted that reduced mortality was associated with a greater number of implementation strategies used (≥ 6); a finding in-consistent with our results. In line with the emphasis on delirium, a larger meta-analysis by Deng et al (54) inclusive of 26 studies that implemented nonpharmacologic delirium recommendations, with or without application of the other domains of the PAD/PADIS guidelines, reported multicomponent interventions were most effective at reducing delirium occurrence and ICU LOS.

Interestingly, a finding in our meta-analysis requiring further research is that the use of fewer EPOC implementation strategies (i.e., 2–4 compared with > 4 bundled interventions) may have greater impact on reducing ICU LOS. We also found a reduction in short-term mortality only in randomized studies, while cohort studies were associated with a reduction in ICU LOS and there were no differences in our subgroup analyses by PADIS domains. Again, our study was inclusive of all PADIS domains and multiple implementation strategies which may suggest that simplicity may have some advantages compared with executing multifaceted and more complex implementation interventions. An alternative viewpoint is that while our meta-analysis was inclusive of randomized controlled trials, it yielded mostly quasi-experimental and cohort studies with low certainty of evidence. Other meta-analyses contained more randomized controlled trials than ours and reported a greater number of implementation strategies associated with improved outcomes (18, 54). Implementation strategy adherence is likely to be greater in controlled trials (vs uncontrolled studies) may explain the unexpected inverse relationship we identified.

Another meta-analysis of 11 studies focused on the application of greater than or equal to three elements of the ICU liberation bundle, not tied to specific PAD/PADIS domains, found in-hospital mortality was not significantly altered, but 28-day mortality was decreased by 18% (56). Although these findings on short-term mortality are in contrast to our pooled estimates, a few differences should be noted. We carefully considered the use of individual EPOC implementation strategies rather than simply evaluating the adoption or lack thereof the ICU liberation bundle. Also, our mortality definition was based on an assessment of death out to 45 days after ICU admission. With continued emphasis on the ICU liberation bundle, either fully or partially implemented, another meta-analysis of 20 qualitative and quantitative studies demonstrated a lower delirium occurrence, a shorter time on MV and in the ICU, increased early mobility, and decreased mortality in both the ICU and hospital compared with patients who received usual care (55). Collectively, none of the previous aforementioned meta-analyses evaluated the association of all PAD/PADIS domains on process and clinical outcomes, in fact, our meta-analysis is the only one that considered all five PADIS elements; the other three meta-analyses (54–56) considered only the PAD domains. We were also comprehensive of outcome associations and implementation interventions beyond the ICU liberation bundle which could explain some of the discordance between our results and those of the other meta-analyses.

Based on the results of our meta-analysis, clinicians should adopt a multifaceted implementation strategy when implementing PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations into practice. Although provider-oriented interventions, educational meetings, distribution of educational materials, and local opinion leader engagement were the most commonly used EPOC strategies in the studies reviewed, the quality improvement literature suggests that these may not represent all of the EPOC strategies that are most effective (13, 57). High-priority implementation strategies include local opinion leader engagement, audit and feedback, local consensus processes, and structural interventions.

Our meta-analysis has limitations. Confounding bias from the inclusion of uncontrolled studies may exist. Practices in the comparator group of included studies may have been influenced by the implementation strategies used at the study site (i.e., also known as the “rising tide” phenomenon) (58). Adherence to intervention protocols was frequently not reported, which is important considering implementation and adherence are closely linked. Even among those studies reporting intervention adherence, gaps in care even after intervention implementation were often reported (59). During ICU implementation efforts, it is recommended that intervention acceptability, appropriateness, penetration, and sustainability be prospectively collected and reported; data on these important implementation science-related outcomes were lacking (60). These factors contributed to the low certainty of evidence found. Most of the identified studies were conducted in academic medical centers, limiting the generalizability of their results to nonacademic medical centers where implementation expertise and resources may be lower and ICU delivery models may be different. The specific recommendations implemented in each study for each PADIS domain were rarely reported. Even if these had been reported, we suspect neither recommendation strength nor strength of evidence would have influenced our results given only three PADIS 2018 recommendations were strong and the strength of evidence was low or very low for most recommendations and is only one consideration during the GRADE evidence-to-decision recommendation generation process (61).

Areas for future research on this subject include assessing guideline adherence and impact of the guideline implementation over time. Since the last PAD/PADIS update was published in 2018, longitudinal assessments of the impact of these guidelines are now possible.

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous PAD/PADIS guideline recommendation implementation strategies may be used in the ICU. Our meta-analysis demonstrated a multifaceted implementation approach aimed at greater than or equal to two elements of the PAD/PADIS guidelines was associated with a significant reduction in ICU LOS and MV duration although no differences in short-term mortality or delirium occurrence were observed. Future research is warranted on the optimal number and types of implementation strategies impacting clinical outcomes associated with PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations in critically ill adults.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question:

What strategies have been used to implement the 2013 Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium (PAD) or 2018 PAD, Immobility, Sleep disruption guidelines and what are their effects on clinical outcomes?

Findings:

This systematic review and meta-analysis found several strategies have been used to implement PAD/PADIS guideline recommendations. A multifaceted approach including greater than or equal to two PAD/PADIS elements was associated with decreased ICU length of stay and mechanical ventilation duration. No differences in short-term mortality or delirium occurrence were observed with this approach.

Meaning:

The number of implementation strategies used to implement the PAD/PADIS guidelines appears to matter for some clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Devlin disclosed he has received research funding from BioExcel, Sedana Medical, and the National Institute of Aging (R13185760, R33HL23452, and R21/R33 AG05797) and that he serves as a consultant to BioExcel, La Jolla Pharmaceuticals, and Ceribell. Dr. Kane-Gill received funding from the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fraser GL, Prato BS, Riker RR, et al. : Frequency, severity, and treatment of agitation in young versus elderly patients in the ICU. Pharmacotherapy 2000; 20:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gélinas C: Management of pain in cardiac surgery ICU patients: Have we improved over time? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007; 23:298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW: Delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2008; 12(Suppl 3):S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honarmand K, Rafay H, Le J, et al. : A systematic review of risk factors for sleep disruption in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:1066–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamdar BB, Combs MP, Colantuoni E, et al. : The association of sleep quality, delirium, and sedation status with daily participation in physical therapy in the ICU. Crit Care 2016; 19:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reade MC, Finfer S: Sedation and delirium in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:444–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ely EW: The ABCDEF bundle: Science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:321–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morandi A, Brummel NE, Ely EW: Sedation, delirium and mechanical ventilation: The ‘ABCDE’ approach. Curr Opin Crit Care 2011; 17:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. ; American College of Critical Care Medicine: Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:263–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, et al. : Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:e825–e873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, et al. : Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel) 2016; 4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinkle M, Kimball R, Haozous EA, et al. : Dissemination and implementation research funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 2005–2012. Nurs Res Pract 2013; 2013:909606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balas MC, Weinhouse GL, Denehy L, et al. : Interpreting and implementing the 2018 pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption clinical practice guideline. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:1464–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pun BT, Balas MC, Davidson J: Implementing the 2013 PAD guidelines: Top ten points to consider. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 34:223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotfis K, Zegan-Barańska M, Żukowski M, et al. : Multicenter assessment of sedation and delirium practices in the intensive care units in Poland—is this common practice in Eastern Europe? BMC Anesthesiol 2017; 17:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leone M, Ragonnet B, Alonso S, et al. ; AzuRéa Group: Variable compliance with clinical practice guidelines identified in a 1-day audit at 66 French adult intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:3189–3195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mo Y, Zimmermann AE, Thomas MC: Practice patterns and opinions on current clinical practice guidelines regarding the management of delirium in the intensive care unit. J Pharm Pract 2017; 30:162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, et al. : A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care 2015; 19:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. : The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC): EPOC taxonomy. Available at: epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy. Accessed 2015

- 21.Al-Qadheeb NS, Balk EM, Fraser GL, et al. : Randomized ICU trials do not demonstrate an association between interventions that reduce delirium duration and short-term mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:1442–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute Study Quality Assessment Tools: Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed January 6, 2023

- 23.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools: Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed January 6, 2023

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. : Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. : Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. (Eds): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023) Cochrane, 2022. Available at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S, et al. ; GRADE Working Group: GRADE Guidelines: 9 rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64:1311–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bardwell J, Brimmer S, Davis W: Implementing the ABCDE bundle, critical-care pain observation tool, and Richmond agitation-sedation scale to reduce ventilation time. AACN Adv Crit Care 2020; 31:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bounds M, Kram S, Speroni KG, et al. : Effect of ABCDE bundle implementation on prevalence of delirium in intensive care unit patients. Am J Crit Care 2016; 25:535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan K, Sanchez D, Hedges S, et al. : A nurse-led intervention to reduce the incidence and duration of delirium among adults admitted to intensive care: A stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial. Aust Crit Care 2023; 36:441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown JC, Querubin JA, Ding L, et al. : Improving ABCDEF bundle compliance and clinical outcomes in the ICU: Randomized control trial to assess the impact of performance measurement, feedback, and data literacy training. Crit Care Explor 2022; 4:e0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cinotti R, Besnard N, Desmedt L, et al. : Feasibility and impact of the implementation of a clinical scale-based sedation-analgesia protocol in severe burn patients undergoing mechanical ventilation: A before-after bi-center study. Burns 2020; 46:1310–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Souza RLP Sr., Abrão J, Garcia LV, et al. : Impact of a multi-modal analgesia protocol in an intensive care unit: A pre-post cohort study. Cureus 2022; 14:e22786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devabhakthuni S, Kapoor K, Verceles AC, et al. : Financial impact of an analgosedation protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in a cardiovascular intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 77:14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faust AC, Rajan P, Sheperd LA, et al. : Impact of an analgesia-based sedation protocol on mechanically ventilated patients in a medical intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 2016; 123:903–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fish JT, Baxa JT, Draheim RR, et al. : Five-year outcomes after implementing a pain, agitation, and delirium protocol in a mixed intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 2022; 37:1060–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frawley A, Hickey J, Weaver C, et al. : Introducing a new sedation policy in a large district general hospital: Before and after cohort analysis. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 2019; 51:4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsieh SJ, Otusanya O, Gershengorn HB, et al. : Staged implementation of awakening and breathing, coordination, delirium monitoring and management, and early mobilization bundle improves patient outcomes and reduces hospital costs. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:885–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jablonski J, Gray J, Miano T, et al. : Pain, agitation, and delirium guidelines: Interprofessional perspectives to translate the evidence. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2017; 36:164–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan BA, Fadel WF, Tricker JL, et al. : Effectiveness of implementing a wake up and breathe program on sedation and delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:e791–e795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kram SL, DiBartolo MC, Hinderer K, et al. : Implementation of the ABCDE bundle to improve patient outcomes in the intensive care unit in a rural community hospital. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2015; 34:250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kresevic DM, Miller D, Fuseck CW, et al. : Assessment and management of delirium in critically ill veterans. Crit Care Nurse 2020; 40:42–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen LK, Møller K, Petersen M, et al. : Delirium prevalence and prevention in patients with acute brain injury: A prospective before-and-after intervention study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2020; 59:102816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Y, Kim K, Lim C, et al. : Effects of the ABCDE bundle on the prevention of post-intensive care syndrome: A retrospective study. J Adv Nurs 2020; 76:588–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loberg RA, Smallheer BA, Thompson JA: A quality improvement initiative to evaluate the effectiveness of the ABCDEF bundle on sepsis outcomes. Crit Care Nurs Q 2022; 45:42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahmoud L, Zullo AR, Thompson BB, et al. : Outcomes of pro-tocolised analgesia and sedation in a neurocritical care unit. Brain Inj 2018; 32:941–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martínez F, Donoso AM, Marquez C, et al. : Implementing a multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium among critically ill patients. Crit Care Nurse 2017; 37:36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren XL, Li JH, Peng C, et al. : Effects of ABCDE bundle on hemodynamics in patients on mechanical ventilation. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23:4650–4656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullinger D, Gilmer A, Jurado L, et al. : Development, implementation, and outcomes of a delirium protocol in the surgical trauma intensive care unit. Ann Pharmacother 2017; 51:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Lingsma H, et al. : Improved guideline adherence and reduced brain dysfunction after a multi-center multifaceted implementation of ICU delirium guidelines in 3,930 Patients. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang XP, Lv D, Chen YF, et al. : Impact of pain, agitation, and delirium bundle on delirium and cognitive function. J Nurs Res 2022; 30:e222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wøien H: Movements and trends in intensive care pain treatment and sedation: What matters to the patient? J Clin Nurs 2020; 29:1129–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng LX, Cao L, Zhang LN, et al. : Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce the incidence and duration of delirium in critically ill patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2020; 60:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moraes FDS, Marengo LL, Moura MDG, et al. : ABCDE and ABCDEF care bundles: A systematic review of the implementation process in intensive care units. Medicine (Baltim) 2022; 101:e29499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang S, Han Y, Xiao Q, et al. : Effectiveness of bundle interventions on ICU delirium: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2021; 49:335–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Curtis JR, Cook DJ, Wall RJ, et al. : Intensive care unit quality improvement: A “how-to” guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen YF, Hemming K, Stevens AJ, et al. : Secular trends and evaluation of complex interventions: The rising tide phenomenon. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:303–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tan CM, Camargo M, Miller F, et al. : Impact of a nurse engagement intervention on pain, agitation and delirium assessment in a community intensive care unit. BMJ Open Qual 2019; 8:e000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McNett M, O’Mathúna D, Tucker S, et al. : A scoping review of implementation science in adult critical care settings. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2:e0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Rochwerg B, et al. : Methodologic innovation in creating clinical practice guidelines: Insights from the 2018 society of critical care medicine pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption guideline effort. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:1457–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.