Abstract

Purpose:

Genetic variants at the low end of the penetrance spectrum have historically been challenging to interpret since their high population frequencies exceed the disease prevalence of the associated condition, leading to a lack of clear segregation between the variant and disease. There is currently substantial variation in the classification of these variants, and no formal classification framework has been widely adopted. The Clinical Genome Resource Low Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group was formed to address these challenges and promote harmonization within the clinical community.

Methods:

The work presented here is the product of internal and community Likert-scaled surveys in combination with expert consensus within the Working Group.

Results:

We formally recognize risk alleles and low penetrance variants as distinct variant classes from those causing highly penetrant disease that require special considerations regarding their clinical classification and reporting. First, we provide a preferred terminology for these variants. Second, we focus on risk alleles and detail considerations for reviewing relevant studies and present a framework for the classification these variants. Finally, we discuss considerations for clinical reporting of risk alleles.

Conclusion:

These recommendations support harmonized interpretation, classification, and reporting of variants at the low end of the penetrance spectrum.

Keywords: Risk Allele, Variant Classification, Penetrance, Clinical Disease Risk Assessment, Association Studies

INTRODUCTION

Genetic variation can be associated with a range of effect sizes with a given phenotype or disease, from highly penetrant variants with near certainty of leading to disease to variants with an individually small effect on disease risk.1 Classic Mendelian conditions typically fall at the higher end of the effect size spectrum, where rare monogenic variation is associated with a high risk of disease. On the lowest end of the effect size spectrum are common genetic variants typically identified in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have a modest association to a given disease or phenotype.1

In the middle of the effect size spectrum reside variants that individually - or as a group of linked variants - are significantly associated with a substantial increased risk of disease, but that do not lead to disease in isolation. Rather, these variants require additional genomic or environmental context to develop disease. Collectively, this class of lower-effect variants have often been termed risk and/or low penetrance variants to distinguish them from highly penetrant variants causing Mendelian disease.2 While some of these variants have been identified by having an oversized effect in case-control studies and are associated with common conditions (e.g., Factor V Leiden3), others are a part of the spectrum of Mendelian disease leading to a substantially lower disease-risk than high-penetrant variants in the same gene.4 Since these variants can be detected in conventional clinical testing for Mendelian disease conditions, a standardized approach for laboratories to assess them is needed.

Recent guidelines have helped to standardize classifications for high penetrance variants,5,6 enabling more consistent terminology and approaches for variant classifications and a reduction in discordant classifications for the same variant across laboratories.7–9 While these guidelines recognized that lower penetrance variants and conditions needed special considerations - including in the context of evaluating association studies and familial segregations as evidence for pathogenicity and discussing decreased penetrance in the final report - the frameworks were not designed to work for risk alleles and low penetrance variants. Specifically, this class of variation is particularly difficult to assess given specific challenges in interpreting population frequency data, functional assessments, and non-segregation events. While there has been some work highlighting standardized approaches for variants at the lower end of the penetrance spectrum, this work has often been focused on GWAS data and meta-analyses to aid in the interpretation between any genetic locus and disease risk.10,11

There are limited available frameworks specifically designed for interpreting risk alleles and low penetrance variants, and there is non-uniformity in the terminology for categorizing these variants.2,12 Additionally, there are no clear guidelines establishing penetrance or risk thresholds for when a variant should be considered as low penetrance or as a risk allele versus a high penetrance variant, nor are there clearly defined boundaries between low penetrance variants and risk alleles. This lack of clarity is further complicated by the findings that many monogenic disease-implicated variants have lower penetrance in the general population than was originally estimated using affected patient cohorts.13 The impact of the lack of standardization has led to these low penetrance/risk variants having the highest rates of discordance between laboratories.14 A similar lack of clarity and standardization is seen in “protective” variants associated with a decrease in disease risk.

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen)15 started the Low-Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group16 to tackle the complexities and inconsistencies in classifying variants for given diseases that lie at the lower end of the penetrance spectrum. The efforts of this working group apply to clinically relevant genetic variation regardless of population frequency or variant type (SNV/indel, CNV, etc.), but exclude variants that are clinically significant only in the context of a polygenic risk score.

Here, we first present the recommendations of the Working Group that formally recognize standardized terminology used to describe variants at the lower end of the penetrance spectrum. Specifically, we define risk alleles and low penetrance variants as two distinct clinically-relevant variant classes that exist in addition to high penetrance variants. These variant classes are separated qualitatively by associated penetrance estimates and the predominant genetic evidence type.

Second, we further focus solely on risk alleles to outline recommendations regarding specific methodology for their assessment and classification when association studies are the primary evidence type by 1) providing guidance on how to interpret association studies in the context of risk alleles, 2) developing a framework for classifying risk alleles, and 3) highlighting important reporting considerations in the context of risk alleles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of Terminology Recommendations

To arrive at a consensus for terminology associated with variants at the low end of the penetrance spectrum, the ClinGen Low-Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group conducted internal Likert-scaled surveys and held discussions on working group calls. Numerous terms and potential thresholds separating variant classes were considered during the surveys and subsequently reduced using a modified Delphi approach. Additionally, data was gathered to assess current laboratory practices with respect to variants at the low end of the penetrance spectrum. Input from the broader genetics community was obtained through a Likert-scaled survey that closed on 4/12/19 with 124 respondents from 18 countries. The survey was distributed to the ClinGen community by email, and the respondents were genetics professionals, including laboratorians, clinicians, and genetic counselors.

RESULTS

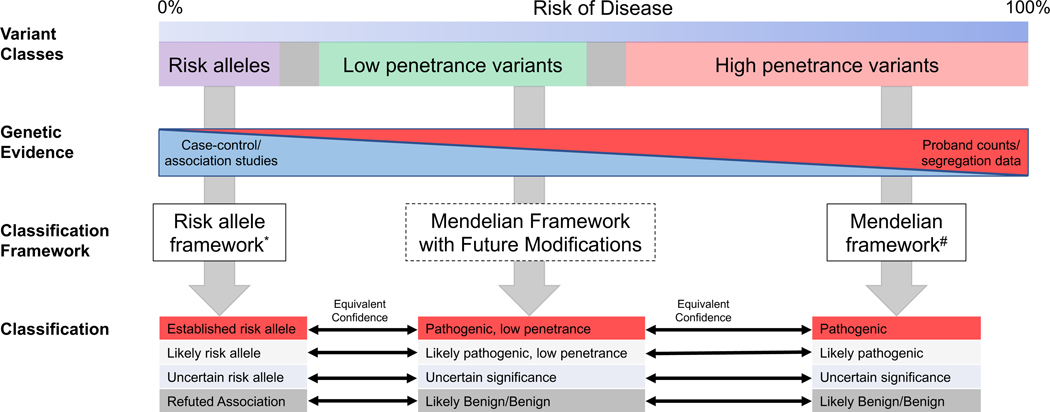

Our survey of the community and discussions within our working group identified three classes of variants separated by their penetrance that require distinct classification considerations: high penetrance variants, low penetrance variants, and risk alleles (Figure 1). High penetrance variants cause monogenic disorders and segregate with disease in families with Mendelian inheritance patterns. These variants are frequently assayed in clinical molecular diagnostic testing for rare disorders, and guidelines for their interpretation and classification have been widely adopted.5,6 Low penetrance variants may also show some evidence of segregation with disease in families. However, the penetrance associated with these variants is reduced such that the presence of the variant alone does not determine whether a disease will occur. In contrast, risk alleles may have appreciable allele frequencies in the population given that they do not cause disease with a high penetrance. These variants are unlikely to segregate with disease in families with a clear inheritance pattern as they explain only a portion of disease risk. While additional environmental and genetic factors affect the penetrance of disease for both low penetrant variants and risk alleles, it is likely that their contribution to the overall disease risk is greater with risk alleles. However, risk alleles still convey enough risk such that their presence or absence may be considered clinically significant.

Figure 1. Harmonization of Terminology and Classification Across the Penetrance Spectrum.

Risk alleles, low penetrance variants, and high penetrance variants are separated by their associated penetrance (e.g. absolute risk of disease associated with the variant). No definitive quantitative boundaries have yet been determined to separate these variant classes. These classes of variants can also be differentiated by their primary type of genetic evidence and therefore require different classification frameworks. Note that a framework for low penetrance variants has not yet been established. Classification tiers across these frameworks can be harmonized by equivalent confidence based on the supporting evidence. *This publication #5,6

Terminology recommendations for risk alleles and low penetrance variants

We use the term risk allele for variants associated with a very small increased risk of disease and the qualifying terms – Established risk allele, Likely risk allele, and Uncertain risk allele – corresponding to the three classification tiers initially suggested by the ACMG/AMP Mendelian sequence variant classification guidelines (Figure 1).5 We also use a parallel approach with classification terminology for a protective allele that is associated with a reduction rather than an increase in disease risk along with the classification tiers - Established protective allele, Likely protective allele, and Uncertain protective allele.

The term risk allele refers to variants with very low penetrance such that they typically do not segregate with disease in Mendelian pattern of inheritance. The term is currently in use with an established role in clinical genetic and laboratory genetic practice.5 Risk alleles have additional complexities not commonly seen in traditional Mendelian genetics. For instance, the risk allele may comprise multiple variants in cis; the risk may be modified due to zygosity; the risk may be modified due to variants in trans; the variant may not confer actual functional risk but is genetically linked to the causative variant; the variant may exist as part of a set of variants where the major contributing variant to disease risk cannot be separated from the other variants; and the risk allele may be environmentally dependent, including in response to other nongenetic risk factors. Although these variants may have a complex nature, especially when the disease risk is due to variants in trans or homozygous variants, the term risk allele can capture these complexities better than other terms considered.

Distinguishing Risk Alleles from High and Low Penetrance Variants

We define a low penetrance variant as a variant that may have evidence of segregating in a Mendelian pattern but for which most individuals harboring this variant do not develop features of the disease. Individuals with these variants manifest disease at a higher rate than the background prevalence for the associated condition, such that the presence of a low penetrance variant alone is clinically significant. We advocate for the use of classification categories with quantitative descriptors of post-test risk (i.e., Pathogenic, low penetrance, etc.) as opposed to less clear terms like “reduced penetrance” which may have different meanings depending on the typical penetrance level for a gene’s role in disease (Figure 1). Additional quantitative details can be included in clinical reports for a variant if population-level studies of individuals not ascertained for disease status have been performed. However, today this information is not always available and not possible to accurately determine in many scenarios.

The categorical descriptions of low penetrance variants, and risk alleles represent qualitative definitions (Figure 1). There is not a clear delineation between highly penetrant Mendelian variants and low penetrance variants, nor is there a clear delineation between low penetrance variants and risk alleles, and specific quantitative penetrance or risk cutoffs could not be defined at this time due to limited quantitative estimates of disease penetrance and variation in practice between different disease areas. For example, variants in some genes may not be associated with high penetrance but are often interpreted similarly to high penetrance variants in routine practice.17–19 However, there was still consensus when the working group asked for feedback from the clinical genomics community. For low penetrance variants, there was agreement with the lower bound of penetrance being in the 10–20% absolute risk range and the upper bound being in the 50% range, though more specificity is required as these results reflect a general response from a single community survey.

Harmonization of Terminology and Classifications Across Variant Classes

The Working Group recognized the potential challenge of multiple co-existing classification frameworks and sought to define precise terminology and harmonize classification tiers across the penetrance spectrum based on equivalent evidence strength (Figure 1). As the number of large-scale sequencing efforts accumulates, genetic evidence for disease-associated rare variants will increasingly come from association and case-control studies of unrelated individuals rather than familial segregation analysis. Toward that end, we propose a harmonized set of classification frameworks for determining the clinical significance of a variant (Figure 1).

This publication provides recommendations for terminology and classification for risk alleles. This new framework will need to be integrated with current practice, which primarily consists of the classification of high penetrance variants associated with Mendelian disease. We seek to align the classification frameworks through equivalent confidence between classification tiers (Figure 1). When deciding which classification framework to use to classify a variant, the genetic evidence type and estimated penetrance should be considered.

Figure 1 outlines a forward-looking scenario that demonstrates how the risk allele framework could be integrated with current practice. We recognize that some quantitative elements may be challenging to implement based on currently available evidence regarding the penetrance associated with a given variant.

Risk alleles and considerations for evaluating association studies

Association studies, where the frequencies of variants are assessed for statistical enrichment between populations with and without disease, represent the major source of evidence of pathogenicity for risk alleles. Thus, informed evaluation of these studies is critical for the interpretation and classification of these variants (Supplemental Table 1). Here we provide a brief overview of the features of these studies and note potential sources of error that should be evaluated to recognize an association as clinically significant.

Defining the Disease Phenotype –

The definition of what constitutes an affected individual (case) may vary considerably between studies. Cases may be defined as a highly specific disease entity or phenotype or as a broad group of individuals with partially overlapping or related phenotypes that constitute a set of potentially distinct conditions, such as developmental delay. The quality of phenotyping may also vary considerably, ranging from comprehensive medical evaluation of each case and control individual to computational assessment of electronic health record (EHR) data to self-reported phenotypes. When evaluating association studies for risk alleles, it is therefore critical to ensure disease phenotypes are consistent across studies and the disease for which the variant’s risk is classified is well-defined. While high penetrance CNVs have, in the past, been classified without association to a specific phenotype,6 we recommend all risk alleles including CNVs, be classified in association with a defined phenotype even if the phenotype is broad (e.g. neurodevelopmental syndrome).

Matching Cases and Controls –

The identification of a true association between a genetic variant and a phenotype relies on proper matching of cases and controls to remove the effect of confounding genetic, environmental, and demographic variables, including age and sex. The most important of these potentially confounding factors is population structure (or population stratification), which is defined as differences in allele frequencies related to ancestry or other factors11. It is critical that studies under evaluation match cases and controls based on ancestry. Studies that use genetically derived ancestry are superior to studies that use self-reported or geographically-defined ancestry in avoiding potential bias. For example, studies that match case and control individuals based on nationality or location that may be of different ancestries are at risk of confounding unless sophisticated methods are taken in data analysis to account for this possibility. Family-based study designs allow data from closely related individuals to be used in association studies and have a low risk for bias due to minimal differences in ancestry between cases and controls. The understanding of associations being primarily studied in the context of a single genetic ancestry also has important considerations for the reporting of risk alleles that is addressed further in this manuscript.

Variant(s) of Interest –

Common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been routinely evaluated in published association studies due to their frequency in the genome and ease with which they can be genotyped. Any genetic variant, regardless of variant type or frequency, may be tested in an association study; however, careful evaluation should be used for rare variants and small insertion/deletion variants assayed through array-based genotyping methods, as these have poorer accuracy.20,21 Additionally, technical variation can lead to error when there are systematic differences in the method by which the genotype is determined for cases and controls. For example, bias may be introduced when cases and controls may be genotyped separately on different platforms.

Genetic Model –

Most variants evaluated in association studies are carried on the autosomes. Genetic associations may be evaluated in an allelic manner where each individual contributes two alleles to the calculation of an allele frequency for cases or controls. Alternatively, associations may be evaluated based on the individual’s genotype, which involves both alleles as well as assumptions regarding how they interact. In a dominant genotype model, a genetic variant in the heterozygous or homozygous state is compared to the homozygous reference state in order to generate a 2×2 table for evaluation.22 In a recessive genotype model, a genetic variant in the homozygous state is compared to the sum of the heterozygous and homozygous reference states.22 It should be clear which genetic model is used in the association study for accurate determination of risk.

Statistical Significance –

In the classic association study design, a 2×2 table is composed of the allele or genotype frequencies for the cases and controls; however, regression analysis may serve as an alternative approach. A statistical test, such as a chi-square test, is used to determine whether a significant association is present that is unlikely to arise by random chance. Many known clinically significant risk alleles were identified in association studies involving one or a few genetic variants. In contrast, association studies may assess the association between many genetic variants and disease risk, which raises the potential for the detection of false positive associations. Thus, it is critical that statistical significance testing be appropriately corrected for multiple hypothesis testing in order to avoid the identification of false positive associations in these scenarios. Typically, the correction is performed by lowering the alpha value threshold from 0.05 based on the number of associations tested using established methods.23 In the case of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), millions of genetic markers may be tested in association with a disease phenotype, and a genome-wide significance threshold of p<5×10−8 is frequently used.24,25

Strength of Effect –

Odds or risk ratios are frequently provided along with 95% confidence intervals to quantify the strength of the observed effect attributable to a given variant. While a large effect size makes it easier to detect an association with statistical significance, an effect size estimate should only be accepted when the result is obtained with statistical significance. Although odds ratios are typically provided to describe the strength of effect observed in a particular study, they can be applied to calculate an estimated probability of disease over baseline for individuals carrying genetic variants with risk or protective effects.26

Replication –

Replication of the results of an association study in an independent population of cases and controls greatly increases the credibility of the association and is critical for developing evidence with clinical validity. Additionally, observing an association with a similar effect size in a replication study adds confidence that the effect size is accurate. For many associations, the initially reported effect size is reduced in replication studies.27

Framework for evaluating risk alleles with association studies as the primary evidence

We present a classification framework for risk alleles in Tables 1 and 2 with Table 1 listing the classification criteria and Table 2 listing the classification tiers. The working group considered all evidence types present in the guidelines for interpretation of high penetrance variants.5 However, many factors were not considered to be relevant to risk alleles since their validity is not influenced by population frequency or segregation evidence. Additionally, a risk allele may itself not be a causative variant but instead may be genetically linked to causative variant(s) present within the same haplotype, reducing the strength of functional association between the variant and the disease. Other sources of information, while potentially useful for risk allele evaluation, were considered by the working group but not included in the classification system, including computational prediction models and association studies that aggregate variants of a certain class (e.g. predicted loss of function variants).

Table 1.

Risk Allele Evidence Criteria

| Criteria Supporting Disease Association a | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Category | Evidence Strength |

|

| |

| Association Studied b | |

|

Very Strong • >1000 individuals studied (>500 cases, >500 controls) • Extensive replication (preferably at least one meta-analysis) with little between-study inconsistency • Bias could not reasonably affect the presence of the association |

|

|

Strong • >100 individuals studied (>50 cases, >50 controls) • Replication of the association result has been performed. Moderate between-study inconsistency is permitted • No obvious bias but there may be missing information regarding factors that could cause bias |

|

|

Limited/Conflicting • A statistically significant disease association assertion has been made. However, the level of evidence does not meet the requirements to be considered Strong or Very Strong due to any of the following: 1) Limited number of individuals studied 2) Lack of replication or large between-study inconsistency with approximately equal evidence for and against the presence of an association (ie, conflicting evidence) 3) Significant potential for bias in the study methodology |

|

| Functional Studies c |

Supporting • Well-established in vitro or in vivo functional studies suggest that the risk (or protective) allele alters gene function through a biologically plausible mechanism |

| Criteria Refuting Disease Association a | |

| Category | Evidence Strength |

| Association Studies a |

Refuting • Evidence suggesting a lack of association is substantially greater than the evidence supporting the association • >1000 individuals studied (>500 cases, >500 controls) refuting association • Replication of the result refuting association • Between study inconsistency representing conflicting evidence does not refute the presence of the association |

These criteria apply for risk alleles associated with increased risk of disease as well as protective alleles associated with decreased risk of disease.

These criteria result from the entire body of evidence associated with a candidate risk allele rather than any individual study.

Functional Studies for risk alleles may require appropriate controls to detected subtle functional effects and avoid false positive functional results.

Table 2.

Risk Allele Classification Framework

| Risk Allele Framework Classifications | Criteria |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Established Risk Allele or | Association Study_Very Strong Evidence |

| Established Protective Allele | +/− Functional Study |

| Likely Risk Allele or | Association Study_Strong Evidence |

| Likely Protective Allele | +/− Functional Study |

| Uncertain Risk Allele or | Association Study_Limited/Conflicting Evidence |

| Uncertain Protective Allele | +/− Functional Study |

| Refuted Association | Association Study_Refuting Evidence |

Criteria Supporting Risk Allele Disease Association

Association Studies –

Genetic evidence in the form of association studies serves as the key evidence item that links a risk allele with a disease phenotype (see above considerations for evaluating association studies). The genetic evidence from separate association studies should be considered as a whole for a risk allele to determine whether the evidence meets the limited, strong, or very strong evidence criteria. These levels of evidence are distinguished by number of individuals studied, the reproducibility of the result, and the likelihood that the study results could be affected by methodological bias. Very strong or strong association study evidence suggests that a clinically valid association is present. While statistical significance is often achieved in part by the presence of a large-effect size, these two concepts are distinct. The evidence strength of this framework is dependent upon statistical significance, independent of effect size, though a laboratory’s decision to report a risk allele may be influenced by the effect size (see reporting considerations below).

Very Strong Evidence

The very strong evidence criterion is applied when there is high confidence in the validity of the disease association and there is little reason to believe that larger studies of a similar design might generate a discordant result. Overall, the underlying studies are well-designed and involve a large number of individuals. Extensive replication (preferably at least one meta-analysis) is present with little between-study inconsistency. All these elements are required in order to apply this criterion.

Strong Evidence

The evidence for association with a disease phenotype is considered strong when a clinically valid association is present that does not meet all elements of the very strong criterion but still requires that a moderate number of individuals have been studied, the association study result has been replicated, and there is no obvious bias present that would confound the study result.

Limited/Conflicting Evidence

A risk allele may have limited evidence for association with a disease phenotype due to limitations of study methodology, a lack of replication, or a limited overall number of individuals examined. Additionally, conflicting evidence is present when there is large between study inconsistency with approximately equal evidence for and against the presence of an association.

Functional Studies –

The biological mechanism of action for a risk allele may be due to a direct effect of the variant assessed or may be due to the action of a potentially unknown, genetically linked variant (or variants). Care must be taken to ensure that functional assays for risk alleles are properly controlled, validated with benign variants, and sensitive enough to reliably detect subtle effects which are more likely to be observed for risk alleles relative to high penetrance variants. Additionally, the biological mechanism of action of a risk allele may differ from the mechanism of action for high penetrance variants in the same gene.

In contrast, experimental studies with negative results, which do not identify a functional effect associated with a variant, do not reduce the validity of an association given that the effect may be mediated by other linked variants or by an unknown biological mechanism.

Supporting Evidence

Functional studies demonstrating a direct effect of the variant identified can serve as supporting evidence for risk alleles as this information provides a mechanistic basis that supports the association study results.

Criteria Refuting Risk Allele Disease Association

Association Studies –

It is anticipated that true disease associations will not be discovered as statistically significant associations in all studies due to random chance or variations in study design (number of individuals, genetic ancestries of individuals, variation in phenotyping, etc.). Thus, there is a level of between-study inconsistency that is reasonable to observe that does not refute the presence of the association. However, multiple, well-designed studies showing a lack of effect or increased risk provide valuable evidence to question or refute a prior disease association assertion.

Refuting

The refuting evidence criterion should be applied when the evidence suggesting a lack of association is substantially greater than the evidence supporting the association. This requires studies of similar design with a greater number of participants that do not show evidence for the presence of the association. The studies refuting the presence of an association should contain a large number of individuals (>500 cases, >500 controls), and the result refuting the association should be replicated in an independent study or derive from a meta-analysis.

Classification

The criteria listed above can be used to generate classifications with levels of confidence ranging from uncertain to likely to established based on the strength of the genetic evidence in the form of association studies (Table 2). Additionally, the effect of the association may be to increase risk for a disease (risk allele) or to protect against a disease phenotype (protective allele). Functional studies demonstrating a direct effect of the variant identified are supporting evidence that increases confidence for the effect of a risk allele but does not elevate its classification beyond what was determined by the genetic evidence.

The classification of uncertain risk allele (or uncertain protective allele) is only assigned once an assertion has been made that has limited evidence. Thus, a variant that lacks any evidence of association with disease would not be classified as an uncertain risk allele (or uncertain protective allele). Risk alleles with limited or conflicting evidence as defined above are classified as uncertain risk allele (or uncertain protective allele).

If the evidence against the presence of an association is substantial and meets the refuting evidence criterion above, the classification of refuted association should be assigned which should be regarded as a benign/likely benign-equivalent classification for risk alleles.5,6

Examples of risk alleles considered by our working group across diverse disease associations are listed in Supplementary Table 2 along with classifications and supporting evidence. These examples are intended to demonstrate the implementation of our risk allele classification framework. Classifications are based on the evidence listed and may change over time with additional evidence.

Reporting considerations for risk alleles

To further advance the use of risk alleles in clinical and laboratory genetics, we used internal surveys and polling to generate consensus of working group members around reporting considerations within the existing processes of a laboratory. Our goal was to highlight important issues for a laboratory to consider when deciding whether to report this class of variants, as opposed to being prescriptive of how a laboratory should practice.

The important elements identified as being useful when determining a reporting strategy include the specifics of the testing scenario (diagnostic, screening, prenatal, cascade testing, etc.), variant classification strength (established or likely risk allele), variant zygosity, the absolute risk (penetrance), and the effect size (e.g. odds ratio or relative risk). There was no consensus within our working group with regards to the importance of secondary-level data elements, including disease information [baseline risk (i.e., prevalence), morbidity, etc.] and intervention information (risk and impact of intervention). Additionally, variant population frequency was determined not to be an important consideration, as these variants are often more common than the disease prevalence.

The working group attempted to find a consensus for the reporting of risk alleles across specific clinical scenarios. These results are dependent upon clinical context (Table 3) and highlight specific areas where uncertainty in the value of reporting risk alleles is still present. Our working group found it challenging to reach consensus for all clinical scenarios. In general, the lack of consensus was due to differences in laboratory policies, test definitions, and consents. Different preferences were generally felt to be acceptable as long as the reporting policy was clearly defined for the assay and communicated to the individual being tested.

Table 3.

Risk Allele Reporting Scenario Consensus

| Risk Allele | Testing Scenario | Working Group Consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Diagnostic Assay (Indication matches) | APC c.3920T>A (p.Ile1307Lys) | Testing an individual with colorectal cancer using a gene panel assay identified the APC c.3920T>A (p.Ile1307Lys) variant. This variant is associated with elevated risk (OR 1.5–2.5) for developing colorectal cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. | Report this variant type, but do NOT make the overall report result “Positive”. Suggest “Result Identified”. Document should include language explaining result and variant-specific evidence language, possibly in a separate section or in the main report clearly denoted as a Risk Allele. |

| Diagnostic Assay (Indication doesn’t match) | MITF c.952G>A (p.Glu318Lys) | Testing for an individual with hearing loss identified the MITF c.952G>A (p.Glu318Lys) variant. This variant is associated with elevated risk (OR 1.7–5.5) for melanoma. | No consensus to report risk alleles that have implications for risk of a disease outside of the indication for the intended diagnostic panel. |

| Prenatal Diagnostics | 15q11.2 recurrent region (BP1-BP2) deletion (arr [GRCh37] 15q11.2q11.2(22832519 23090897) xl) | A prenatal microarray was ordered on a fetus with a ventricular septal defect (VSD). The 15q11.2 recurrent region (BP1-BP2) deletion (arr [GRCh37] 15q11.2q11.2(22832519_23090897) x1) was identified. This variant is associated with elevated risk (OR 2–4) for a broad spectrum of cognitive disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 8% for cognitive defects. | No consensus was reached for this scenario. |

| Secondary Findings | APC c.3920T>A (p.Ilel307Lys) | Exome sequencing with opt-in for secondary findings identified the APC c.3920T>A p.Ile1307Lys variant in an individual without personal or family history of colorectal cancer. This variant is associated with elevated risk (OR 1.5–2.5) for developing colorectal cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. | No consensus to report this variant type when identified as a secondary finding. Many confounding factors, including uncertainty surrounding reported ancestries. |

| Genomic (Healthy) Screening |

AP0L1 G1 allele (homozygous) c.[1024A>G;1152T>G] p.[Ser342Gly;Ile384Met] |

Genome screening for a healthy individual identified the AP0L1 Gl variant in the homozygous state. This diplotype is associated with elevated risk (OR 9.6–47.4) for multiple renal diseases in African Americans, particularly focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). | The consensus of the group was to report the variant in this scenario. |

| Preconception Carrier Screening | GBA c.1226A>G (p.Asn409Ser) | Carrier screening for common, severe disease in a pregnant 20 yo identified the GBA c.1226A>G (p.Asn409Ser). This variant is pathogenic for Gaucher disease, but also is associated with elevated risk (OR 3.1–4.0) for Parkinson disease. | The consensus for this scenario would be to report the pathogenic association, but not the risk association given that the risk association is outside of the indication for testing. |

The working group reached consensus on the following general points regarding the reporting of risk alleles.

Working Group Consensus Opinions

Information regarding disease risk given the test result(s) should be included on clinical genetic reports when available. If accurate absolute risk information is available, it should be stated. This may be provided as aggregate gene-level penetrance or as penetrance for an individual variant if there is specific evidence for the reported variant. When penetrance information is limited or unavailable, or penetrance is being assumed based on gene-level information, this should be explicitly stated. In an ideal scenario, the report would include absolute risk estimates, though currently this is often not feasible. At this time, effect size estimates are most often available in the form of risk ratios (relative risk) or odds ratios calculated from association studies. Large, systematic studies in populations unbiased for their ascertainment of disease status, are often still needed to determine the disease penetrance associated with genetic variants to inform clinical care of patients at risk for genetic disorders.

The consensus lower-bound for including a risk allele on a report is a 2–3 fold increased risk of disease. As risk alleles are most often identified via case-control studies, the definition of a risk allele theoretically could extend to the scores of variants identified via GWAS studies as having a significant disease-association. However, these variants typically have such a low impact that clinical management would not change, and thus would not be clinically relevant findings outside of a polygenic risk score. In general, there was consensus to not consider a variant reportable as a risk allele unless there was a minimum 2–3-fold increased risk of disease, as defined by odds ratio or relative risk, with statistical significance.

In a diagnostic setting, the overall report result should NOT be considered “positive” when only a risk allele is identified. Genetic testing reports typically feature a top-line interpretation of the results. This overall result helps inform the practitioner and tested individual about the relevance of the variant to the indication for testing. For risk alleles, there was a consensus that if found in a diagnostic assay without other findings, this should not lead to an overall “positive” report and that identified risk alleles would warrant specific qualifying language or reporting in a separate section of the report compared to high penetrance variants.

For risk alleles primarily identified in individuals of a specific genetic ancestry group, the consensus of the working group is to report these variants when identified in any individual regardless of ancestry. There are limitations and uncertainties in the generalizability of risk allele associations when associations are identified in studies involving individuals of only a specific genetic ancestry group. This is especially true in instances where the risk allele is not the causative variant or when the background haplotype contributes to the risk effect. However, in most instances this information is unknown and the laboratory’s assay may not be designed to determine genetic ancestry. Therefore, the consensus is that it would be informative to return these variants regardless of the genetic background of the individual and to clearly detail the potential limitations of the risk association in the report.

If a risk allele only confers risk in the homozygous or compound heterozygous state, there is also consensus to not report the risk allele in heterozygous carriers. Note that this consensus contrasts with the practice of returning carrier status for genes associated with high penetrance disorders. The absolute risk of disease for an individual with a heterozygous risk allele carrier state is largely uncertain in the absence of additional genetic and environmental information. An exception to this consensus opinion occurs when the risk alleles are specifically being targeted for testing; for example, an assay only interrogating the G1 and G2 alleles in APOL1 for a possible kidney donor. In the case of targeted testing, the consensus is that the variants would always be returned regardless of zygosity.

In instances when functional or case studies have identified the true causative variant that is in linkage disequilibrium with the previously identified risk allele, the functional variant should be preferentially analyzed and reported. It is possible that upon further investigation, a true causative variant is identified that confers the disease risk associated with the risk allele. A recent example of this was identified in MYBPC3, where a large intronic deletion common in the South Asian population was associated with cardiomyopathy, but more detailed studies identified a deep intronic variant in linkage disequilibrium as the true functional allele associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.28 This variant was previously outside of the region of interest and/or capture for most assays, and thus was missed from testing. In these instances, the association with the risk allele is still valid, especially in the population(s) where the association was identified. However, laboratories are strongly encouraged to interrogate and report the causal variant and to indicate in their evidence summaries for the risk allele that the causative variant has been identified.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present recommendations from the ClinGen Low-Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group. We propose harmonized terminology for variants at the low end of the penetrance spectrum based on community input which formally recognizes three distinct classes of variants separated by penetrance that warrant different classification considerations. Specifically, we provide terminology for risk alleles and low penetrance variants to distinguish them from variants that are associated with a very high likelihood of disease Additionally, for risk alleles, we provide: 1) considerations when performing evidence curation when evaluating association studies, 2) a novel risk allele classification framework where the primary evidence type is association studies, and 3) considerations for the reporting of risk alleles. Further recommendations for the classification of low penetrance variants are being evaluated by this working group for dissemination to the community. The goal of this multi-pronged effort is to facilitate the appropriate evaluation of these variant types in clinical and laboratory practice. We hope that through consistent and standardized terminology and classification, the confusion and discrepancies around these variants can be lessened.

We recognize that different classification frameworks across the penetrance spectrum are needed and will operate in parallel. Indeed, recent efforts have acknowledged the need for developing or expanding classification frameworks to encompass risk alleles and low penetrance variants.29,30 These proposed classification systems emphasize functional evidence but do not provide a clear means for evaluating the strength of genetic evidence in the form of association studies. Our current work provides a framework for the classification of risk alleles primarily driven by genetic evidence in the form of association studies. Functional evidence can be supportive when present but does not serve as the primary driver for the classification of risk alleles as there are several scenarios where one could observe variable experimental results.

Our working group is actively evaluating how the existing frameworks apply to the classification of low penetrance variants. These variants are challenging in that their evidence for disease association has elements of both risk alleles and highly penetrant Mendelian variants. Modifying the existing frameworks to fit the evaluation of these variants is critical for both accurate classification and communication of the diagnostic and predictive strength of these variants.

In addition, the working group is tackling defining the penetrance boundaries separating risk alleles, low penetrance variants, and highly penetrant variants. As of now, there is no clear quantitative delineation between these groups. This is made more challenging by the continued recognition that observed penetrance is lower for many variants than previously thought.13,31,32 Nevertheless, the working group hopes to provide additional guidance on when to use the specific terminology outlined in this framework.

Our risk allele terminology and framework currently do not account for hypomorphic variants in recessive Mendelian disease that only cause disease in trans with a high penetrance allele. These variants are similar to risk alleles and low penetrance variants in that they are often found at frequencies higher than expected for Mendelian conditions. However, their evidence for disease association may be different than risk alleles and low penetrant variants, and thus, additional guidelines for the classification of these variants is likely to be needed.

The working group hopes that this manuscript can aid in the appropriate inclusion of risk alleles into clinical and laboratory genetics. As such, we are engaging the community, including ClinGen and its associated Clinical Domain Working Groups, to implement these new recommendations, and our recommended terminology has recently been made available in ClinVar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the ClinGen Low Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group and the ClinGen community as a whole for their contributions to the surveys and feedback during community presentations.

Funding Statement

This publication was supported by ClinGen, which is primarily funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) with co-funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), through the following grants: Baylor/Stanford - U24HG009649, Broad/Geisinger - U24HG006834, and UNC/Kaiser - U24HG009650. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethics Declaration

No human or animal data was used in this manuscript aside from data from previous publications.

ClinGen Low Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group Membership

Kayleigh Avello, Pinar Bayrak-Toydemir, Katherine Benson, Alicia Byrne, Wuyan Chen, Bradley Coe, Laura Conlin, Fergus Couch, Hannah Dziadzio, Yuxin Fan, Mythily Ganapathi, John Garcia, Michael Gollob, Emily Groopman, James Harraway, Vaidehi Jobanputra, Melissa Kelly, Matt Lebo, Jordan Lerner-Ellis, Minjie Luo, Elaine Lyon, Deqiong Ma, Glenn Maston, Kelly McGoldrick, Jessica Mester, Nifang Niu, Blake Palculict, Tina Pesaran, Toni Pollin, Erik Puffenberger, Emily Qian, Sarah Richards, Marcy Richardson, Erin Riggs, Samantha Schilit, Ryan Schmidt, Panagiotis Sergouniotis, Amanda Spurdle, Marcie Steeves, Nicholas Watkins, Lauren Zec, Wenying Zhang

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

The framework and any variants classified by ClinGen using the framework will be made available to the community on an on-going basis.

References

- 1.ssing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461(7265):747–753. 10.1038/nature08494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senol-Cosar O, Schmidt RJ, Qian E, et al. Considerations for clinical curation, classification, and reporting of low-penetrance and low effect size variants associated with disease risk. Genet Med. 2019;21(12):2765–2773. 10.1038/s41436-019-0560-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden Thrombophilia. In: Adam, Mirzaa, Pagon, et al. , eds. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA)1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thauvin-Robinet C, Munck A, Huet F, et al. The very low penetrance of cystic fibrosis for the R117H mutation: a reappraisal for genetic counselling and newborn screening. J Med Genet. 2009;46(11):752–758. 10.1136/jmg.2009.067215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet Med. 2020;22(2):245–257. 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amendola LM, Muenzen K, Biesecker LG, et al. Variant Classification Concordance using the ACMG-AMP Variant Interpretation Guidelines across Nine Genomic Implementation Research Studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107(5):932–941. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison SM, Austin-Tse CA, Kim S, et al. Harmonizing variant classification for return of results in the All of Us Research Program. Hum Mutat. 2022;43(8):1114–1121. 10.1002/humu.24317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison SM, Dolinksy JS, Chen W, et al. Scaling resolution of variant classification differences in ClinVar between 41 clinical laboratories through an outlier approach. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(11):1641–1649. 10.1002/humu.23643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschhorn JN, Lohmueller K, Byrne E, Hirschhorn K. A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet Med. 2002;4(2):45–61. 10.1097/00125817-200203000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis JP, Boffetta P, Little J, et al. Assessment of cumulative evidence on genetic associations: interim guidelines. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(1):120–132. 10.1093/ije/dym159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niehaus A, Azzariti DR, Harrison SM, et al. A survey assessing adoption of the ACMG-AMP guidelines for interpreting sequence variants and identification of areas for continued improvement. Genet Med. 2019;21(8):1699–1701. 10.1038/s41436-018-0432-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodrich JK, Singer-Berk M, Son R, et al. Determinants of penetrance and variable expressivity in monogenic metabolic conditions across 77,184 exomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3505. 10.1038/s41467-021-23556-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S, Lincoln SE, Kobayashi Y, Nykamp K, Nussbaum RL, Topper S. Sources of discordance among germ-line variant classifications in ClinVar. Genet Med. 2017;19(10):1118–1126. 10.1038/gim.2017.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehm HL, Berg JS, Brooks LD, et al. ClinGen--the Clinical Genome Resource. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2235–2242. 10.1056/NEJMsr1406261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ClinGen Low Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group. https://clinicalgenome.org/working-groups/low-penetrance-risk-allele-working-group/. Accessed 9 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consortium CBCC-C. CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10,860 breast cancer cases and 9,065 controls from 10 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(6):1175–1182. 10.1086/421251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(3):183–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laver TW, Colclough K, Shepherd M, et al. The Common p.R114W HNF4A Mutation Causes a Distinct Clinical Subtype of Monogenic Diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65(10):3212–3217. 10.2337/db16-0628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blout Zawatsky CL, Shah N, Machini K, et al. Returning actionable genomic results in a research biobank: Analytic validity, clinical implementation, and resource utilization. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108(12):2224–2237. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weedon MN, Wright CF, Patel KA, Frayling TM. Unreliability of genotyping arrays for detecting very rare variants in human genetic studies: Example from a recent study of MC4R. Cell. 2021;184(7):1651. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis CM, Knight J. Introduction to genetic association studies. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012;2012(3):297–306. 10.1101/pdb.top068163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So HC, Sham PC. Multiple testing and power calculations in genetic association studies. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011(1):pdb top95. 10.1101/pdb.top95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genomewide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(3):227–234. 10.1002/gepi.20297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pe’er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(4):381–385. 10.1002/gepi.20303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudley JTK KJ Exploring personal genomics. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioannidis JP. Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):640–648. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper AR, Bowman M, Hayesmoore JBG, et al. Reevaluation of the South Asian MYBPC3(Delta25bp) Intronic Deletion in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13(3):e002783. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Houge G, Laner A, Cirak S, de Leeuw N, Scheffer H, den Dunnen JT. Stepwise ABC system for classification of any type of genetic variant. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30(2):150–159. 10.1038/s41431-021-00903-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masson E, Zou WB, Genin E, et al. Expanding ACMG variant classification guidelines into a general framework. Hum Genomics. 2022;16(1):31. 10.1186/s40246-022-00407-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin CL, Wain KE, Oetjens MT, et al. Identification of Neuropsychiatric Copy Number Variants in a Health Care System Population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1276–1285. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld JA, Coe BP, Eichler EE, Cuckle H, Shaffer LG. Estimates of penetrance for recurrent pathogenic copy-number variations. Genet Med. 2013;15(6):478–481. 10.1038/gim.2012.164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The framework and any variants classified by ClinGen using the framework will be made available to the community on an on-going basis.