SUMMARY

RNF168 plays a central role in the DNA damage response (DDR) by ubiquitylating histone H2A at K13 and K15. These modifications direct BRCA1-BARD1 and 53BP1 foci formation in chromatin, essential for cell cycle-dependent DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway selection. The mechanism by which RNF168 catalyzes the targeted accumulation of H2A-ubiquitin conjugates to form repair foci around DSBs remains unclear. Here, using cryo-EM, NMR spectroscopy and functional assays, we provide a molecular description of the reaction cycle and dynamics of RNF168 as it modifies the nucleosome and recognizes its ubiquitylation products. We demonstrate an interaction of a canonical ubiquitin-binding domain within full-length RNF168, which not only engages ubiquitin but also the nucleosome surface, clarifying how such site-specific ubiquitin recognition propels a signal amplification loop. Beyond offering mechanistic insights into a key DNA DDR protein, our study aids in understanding site specificity in both generating and interpreting chromatin ubiquitylation.

Keywords: DNA damage response, chromatin, nucleosome, ubiquitin ligase, RNF168, UbcH5c, BRCA1-BARD1, 53BP1, Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

RNF168 controls the chromatin recruitment of several DNA damage response (DDR) proteins, but its mechanisms of action remain unclear. Hu et al. unveil how RNF168 selectively ubiquitylates histone H2A in the nucleosome and reads its own ubiquitylation products, allowing propagation on chromatin of ubiquitin marks recognized by DDR proteins.

INTRODUCTION

The mono-ubiquitylation of histone H2A and its variant H2AX at lysine amino acids (aa) 13 and 15 (H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub), catalyzed by RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF168 and an E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, is central to DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair in vertebrates.1–7 RNF168 binds its reaction products, H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub, and spreads these post-translational modifications (PTMs) over kilobases from the initial site, as observed in the formation of ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF). Mutations in RNF168 that disrupt this signal propagation are associated with RIDDLE syndrome, a rare genetic disorder characterized by immunodeficiency, radiosensitivity and cancer predisposition.1,8–10 Ubiquitin signal amplification by RNF168 triggers the accumulation of several proteins on chromatin, including 53BP111–13 and BRCA1-BARD1,14–18 two functionally antagonistic factors regulating the DSB repair pathways of homologous recombination (HR) and classical non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).19,20 Dysregulation of RNF168 alters the balance of DNA repair pathway selection, compromising genomic stability.21 RNF168 also supports DNA repair independently of BRCA1, making inhibiting RNF168 a potential synthetic lethal strategy to treat patients with BRCA1-deficient cancer.22 Hence, there is considerable interest in unraveling the molecular mechanism for RNF168 target specificity.

Our understanding of how E3 and E2 enzymes ubiquitylate a given substrate is restricted by the transient nature of E3-E2-substrate associations, making it challenging to experimentally determine three-dimensional (3D) structures.15,23–25 How RNF168 catalyzes the selective modification of H2AK13 and H2AK15 and how it recognizes these PTMs with high specificity in the nucleosome core particle26 (NCP) for signal amplification is unclear.27,28 Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies with isotopically labeled histones in the NCP and chemical cross-linking coupled with mass spectrometry have provided useful information to model how the RING domain of RNF168 might be positioned on the NCP surface.29 However, 3D structures of RNF168 or RNF168-E2 complex bound to the NCP remain to be determined to help elucidate the mechanism for ubiquitin conjugation to H2A K13 and K15. Furthermore, there is no indication that RNF168 binds H2BK120ub, a modification adjacent to H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub in the NCP, which can also be triggered by DSBs.30,31 It is not known how RNF168 would selectively recognize nucleosomal H2AK13ub or H2AK15ub over H2BK120ub.

To address these outstanding questions, we investigated the interaction of RNF168, both full-length and shorter fragments, with various NCP constructs. Using an integrative approach that combines single-particle cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and functional assays, we provide a high-resolution dynamic view of RNF168-mediated H2A ubiquitylation. Furthermore, our studies demonstrate an unexpected context specificity for the recognition of H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub by RNF168 in the NCP, with implications for understanding ubiquitin signal amplification.

RESULTS

Context dependency of RNF168FL interaction with the ubiquitylated NCP

RNF168 controls ubiquitin signal amplification by generating and recognizing H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub. This process, best studied in cells treated with ionizing radiation, results in the formation of clusters or IRIF of these PTMs, which involve hundreds of NCPs in chromatin. It is unknown how RNF168 specifically identifies its own ubiquitylation products to form these IRIF. Previous studies have highlighted the NCP-recognition LR motif, or LRM,32 which, together with a canonical ubiquitin binding domain (UBD), directs various DNA damage response (DDR) proteins, including RNF168 with MIU2-LRM, to ubiquitylated NCPs in chromatin.32–34 LRM specifies the NCP as the ubiquitylated target. However, it is not understood how RNF168 specifically selects H2AK13ub or H2AK15ub over adjacent H2BK120ub, considering that ubiquitin is flexibly anchored to the NCP.34 To address this knowledge gap, we first examined the interaction of full-length human RNF168 (RNF168FL, aa 1–571) and RNF168 MIU2-LRM (aa 430–481) with both the unmodified NCP and the NCP carrying H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub (NCPub) (Figures 1A and 1B). RNF168FL binds the NCP and NCPub with dissociation constants (Kds) of ~0.12 μM and ~0.05 μM, respectively (Figure 1B). RNF168 MIU2-LRM does not bind the NCP and its affinity for NCPub is ~30 times lower than that of RNF168FL, with a Kd of ~1.4 μM (Figures 1B and 1C). The disparity in affinity may stem from additional contacts of RNF168FL, including its RING domain, with the NCP.

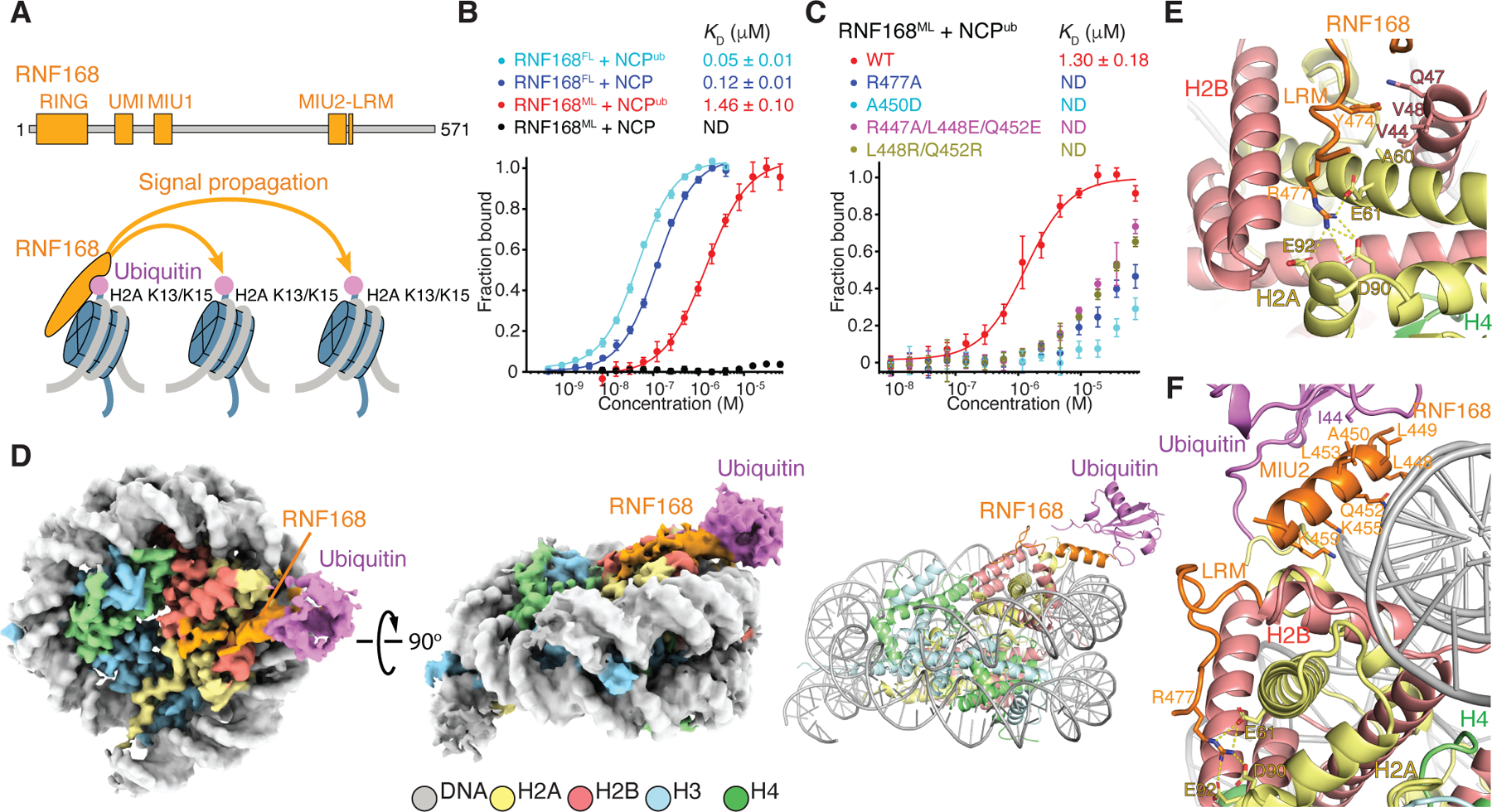

Figure 1. Interactions of RNF168 with the ubiquitylated NCP.

(A) Top: Domain structure of RNF168. Bottom: Schematics of nucleosomal H2A K13 and K15 ubiquitylation catalyzed by RNF168, illustrating signal amplification by recognition of H2AK13ub or H2AK15ub.

(B and C) Fluorescence polarization binding curves of fluorescently-labeled NCP or NCP carrying H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub (NCPub) with full-length RNF168 (RNF168FL) and RNF168 MIU2-LRM (aa 430–481) (RNF168ML) (B), and with WT RNF168ML and mutants (C). Data are mean ± s.d. for each data point (n = 3 technical replicates). Kd values are indicated. ND means not determined.

(D) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structural model (right) of the RNF168FL-NCPub complex displayed in two orientations. While the complex was assembled with RNF168FL, the only density detected was for RNF168 MIU2-LRM.

(E) Close-up view of polar interactions (yellow dashes) between RNF168 LRM R477 and indicated acidic patch residues in H2A, and hydrophobic interactions between LRM Y474 and indicated residues in H2A and H2B.

(F) Close-up view of RNF168 MIU2-LRM interactions with the NCP and ubiquitin linked to H2A K15, highlighting canonical interaction of ubiquitin with MIU2 and proximity of MIU2 to the NCP surface.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Next, we used single-particle cryo-EM to investigate how RNF168FL recognizes H2AK15ub within a di-NCP (di-NCPub). Because each NCPub in the di-NCPub behaves independently owing to inter-nucleosomal flexibility, the cryo-EM data were processed at the level of a single NCPub. We reconstructed three distinct 3D classes at resolutions of 3.6 Å, 3.7 Å and 3.8 Å after refinement in RELION35 (Figures 1D, S1, and S2; Table S1). We modeled RNF168 aa 446–461 (MIU2) and 465–478 (LRM) bound to NCPub. Other regions of RNF168FL, including the other two UBDs (UMI and MIU1) and the RING domain, were not identifiable in the density, presumably because of molecular flexibility. The 3D classes differ mainly in their conformations for ubiquitin, demonstrating that while ubiquitin retains some flexibility as illustrated by conformational variability analysis in Video S1, its motions are markedly restricted by RNF168FL. In the absence of RNF168FL, there is no clear density for ubiquitin in NCPub (data not shown). In the three classes, the LRM density is well-defined and the amino acid side chains could be modeled (Figure S1C). LRM adopts a curved fold, held together by several contacts with H2A and H2B. The guanidinium group of LRM R477 forms salt bridges with H2A E61, D90 and E92 in the NCP acidic patch26 (Figures 1E, 1F, S1B, and S1C). The aromatic ring of LRM Y474 inserts into a hydrophobic cavity formed by the side chains of H2A A60, H2B V44 and V48, and the aliphatic region of Q47 (Figure 1E). Consistent with the structure, the R477A mutation drastically weakened the interaction of MIU2-LRM with NCPub (Figure 1C). MIU2 appears α-helical in the 3.7-Å resolution class but lacks sufficient resolution for de novo side chain positioning. To better interpret the density, we generated a homology model using the available 3D structure of RNF169 MIU2 bound to ubiquitin as a template.33 Ubiquitin binding involves a canonical interface centered on ubiquitin I44 contacting RNF168 MIU2 L449, A450 and L453 (Figure 1F). As anticipated, the A450D mutation almost abolished MIU2-LRM binding to NCPub (Figure 1C). Surprisingly, MIU2 also contacts the NCP, with R447, L448, Q452, K455 and K459 on one side of the α-helix pointing toward the NCP surface (Figure 1F). Residues Q452, K455 and K459 probably interact with the DNA. Consistent with our model, the triple mutant R447A/L448E/Q452E had noticeably decreased affinity for NCPub (Figure 1C). The L448R/Q452R mutant, with positive charges to potentially enhance NCPub binding, unexpectedly diminished the affinity, possibly due to steric clashes (Figure 1C).

To our knowledge, no reported structure has a canonical UBD binding both ubiquitin and the substrate. The MIU2-NCP interaction, deemed transient, likely contributes to the reduced mobility of ubiquitin in NCPub in the presence of RNF168FL. In this specific MIU2 binding mode, ubiquitin linked to K15 or K13 in the flexible N-terminal tail of H2A is predicted to impose fewer constraints on NCPub-bound MIU2-LRM than when linked to K120 in the ordered C-terminal α-helix of H2B. Notably, while 53BP1 recognizes nucleosomal H2AK15ub, it does not recognize H2BK120ub.13 Therefore, if the three ubiquitylated sites coexist in chromatin in vivo, it is probable that RNF168 preferentially engages H2AK15ub or H2AK13ub over H2BK120ub.

Interaction of RNF168R-UbcH5c with the NCP in a pre-reaction state structure

In the density of RNF168FL bound to di-NCPub, the RING domain (RNF168R, aa 1–94), essential for substrate ubiquitylation, was not detectable. Nonetheless, RNF168R binds the NCP with a Kd of 0.4 μM (Figure 2A). Since RNF168R catalyzes ubiquitin transfer to the NCP or H2A-H2B in vitro in the presence of UbcH5c (also known as UBE2D3) and UBA133,36,37 (Figure 2B), we focused on this system for structure-function studies. To allow structure determination, we assembled two complexes of RNF168R-UbcH5c and the NCP in which RNF168R, UbcH5c, H2A and H2B are genetically tethered in different orders with intervening flexible linkers in a single protein chain. The two resulting chains (RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2B-H2A and H2B-H2A-RNF168R-UbcH5c) are then assembled into corresponding RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP and NCP-RNF168R-UbcH5c. Both systems were equally functional as verified by ubiquitylation assays, demonstrating appropriate interaction of RNF168R-UbcH5c with H2A-H2B (Figure S3A). With this approach, we determined the cryo-EM structure of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP using cryoSPARC,38 with a resolution of 3.2 Å (Figures 2C, S3B, and S4A–S4F; Table S2).

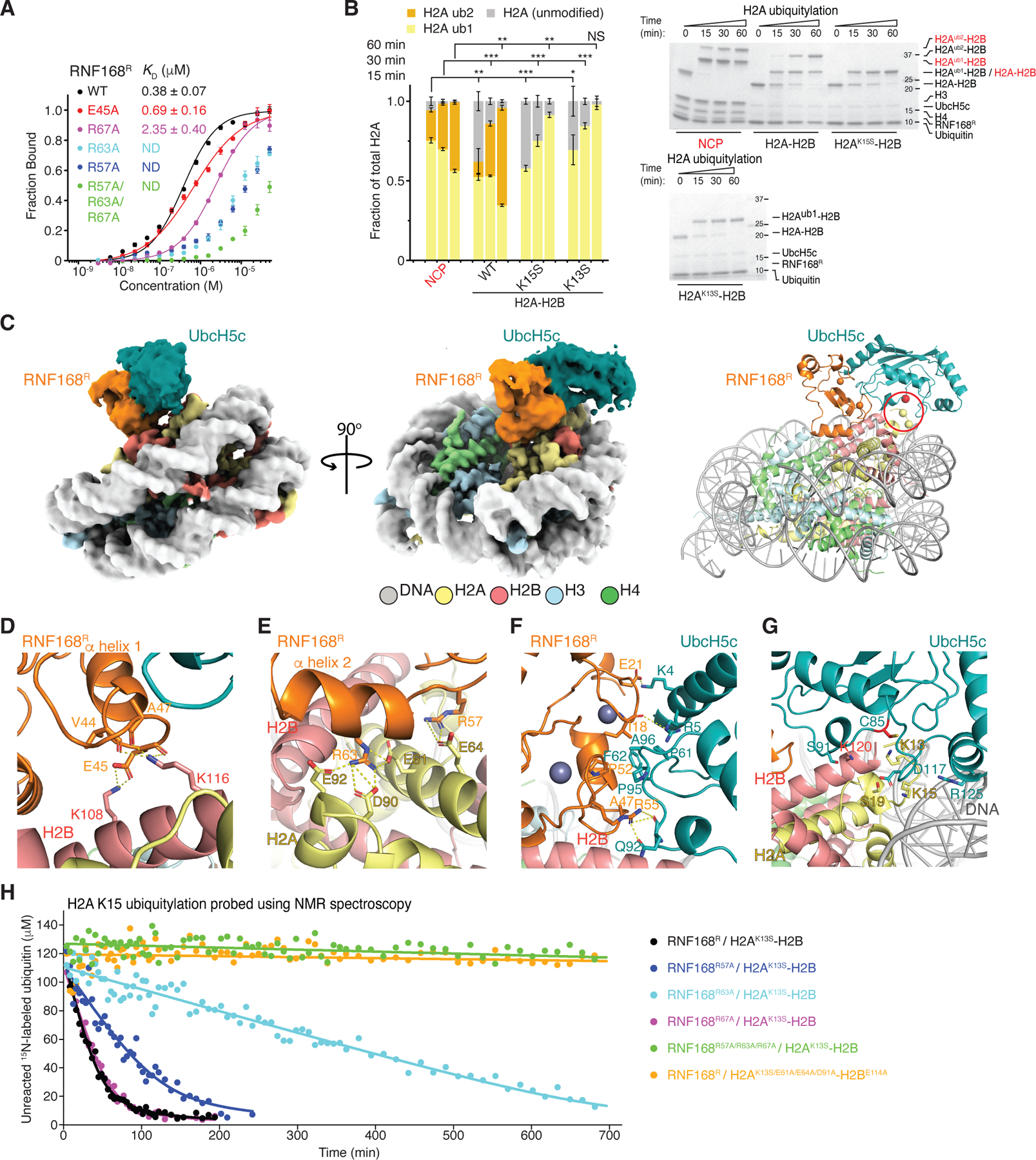

Figure 2. Structure and activity of RNF168R-UbcH5c with the NCP.

(A) Fluorescence polarization binding curves of RNF168R, WT and mutants, with fluorescently-labeled NCP. Data are mean ± s.d. for each data point (n = 3 technical replicates). Kd values are indicated. ND means not determined.

(B) Left: Quantification of the NCP or H2A-H2B (WT or mutants) ubiquitylation from n = 3 independent experiments. Bar graphs show the mean and s.d. for each data point. P values were calculated using a two-sample two-tailed Student t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS means not significant. Right: Representative SDS-PAGE gels of ubiquitylation assays of the NCP, WT H2A-H2B, H2AK13S-H2B and H2AK15S-H2B using UBA1, UbcH5c and RNF168R.

(C) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structural model (right) of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP complex displayed in two orientations. Locations of H2A K13 and K15 (yellow spheres) and active site C85 of UbcH5c (red sphere) are circled in red.

(D–G) Close-up views of the interactions between RNF168R and H2A-H2B (D and E), RNF168R and UbcH5c (F), and active site of UbcH5c and H2A-H2B (G). Relevant side chains, hydrogen bonds (yellow dashed lines) and Zn+2 (purple spheres) are highlighted.

(H) Ubiquitylation reaction profiles of H2AK13S-H2B and H2AE61A/E64A/D91A-H2BE114A catalyzed by WT RNF168R and mutants. Reactions were probed by monitoring the NMR signal intensity changes of unreacted 15N-labeled ubiquitin.

See also Figures S3–S6.

The interface between RNF168R and the NCP is well defined in the cryo-EM density (Figures 2C and S4G–S4H). At the C-terminal end of RNF168R α-helix 1 (aa 37–48), the carbonyl groups of V44, E45 and A47 establish helix-capping ion-dipole interactions with the ε-ammonium group of H2B K116 (Figure 2D). In addition, the carboxyl group of E45 forms a salt bridge with the ε-ammonium group of H2B K108 (Figure 2D). There are two side chain conformations for H2B K108 and K116, with only one conformation of each residue interacting with the NCP (Figure S4I). In another interaction involving RNF168R α-helix 2 (aa 59–67), the guanidinium group of R63 forms salt bridges with the carboxylate groups of H2A E61, D90 and E92 in the H2A-H2B acidic patch26 (Figure 2E). The side chain of R67 points toward H2A E91 and E92 in the acidic patch and probably participates in charge-charge interactions with these residues (Figure S4J). In the Zn2+-binding loop joining α-helices 1 and 2, the guanidinium group of RNF168R R57 forms a salt bridge with the carboxylate group of H2A E64 (Figures 2E and S4J). Together, the ion-dipole interactions mediated by α-helix 1 and charge-charge interactions involving R63 in α-helix 2 define the orientation of RNF168R relative to the NCP surface.

To further evaluate the structure, we used NMR spectroscopy to probe the interaction of RNF168R with histone H2A-H2B in solution (Figure S5A). Titration of 15N-labeled RNF168R with unlabeled H2A-H2B resulted in marked changes in the 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of RNF168R. Several signals were exchange broadened or shifted or both, reflecting direct as well as long-range effects (Figure S5A). The signals most affected by exchange broadening were those of E45 and R63. The most shifted signals were those of R57 and T66, which is near R63. As expected, based on the cryo-EM structure there were only minute changes in chemical shifts when the RNF168R R57A and R63A mutants were titrated with H2A-H2B (Figure S5B). Overall, the NMR characterization agrees well with residues from α-helices 1 and 2 of RNF168R interacting directly with H2A and H2B as seen in the RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP cryo-EM structure.

The complementary NMR titration of 15N,2H-labeled H2A-H2B with unlabeled RNF168R caused spectral changes on the fast to intermediate chemical shift timescale for H2A E61 and E64 in the acidic patch and in several H2A and H2B residues nearby, consistent with the binding interface in the cryo-EM structure (Figure S5C). The marked signal perturbations observed in the C-terminal helix of H2B (residues G104-T122) including K108 and K116 are likewise consistent with the structure (Figures S5C and S5D). We also performed titrations of 13C-methyl-enriched H2A-H2B, alone and as part of the NCP, with unlabeled RNF168R-UbcH5c using methyl-TROSY NMR spectroscopy.39 Although the methyl probes are limited to isoleucine, leucine and valine residues, the spectral perturbations detected in free and nucleosomal H2A-H2B agree well with the RNF168R-H2A-H2B interface revealed in the cryo-EM structure (Figure S5E).

In agreement with the cryo-EM structure and NMR data, the RNF168R mutants E45A, R57A, R63A and R67A exhibited weaker NCP binding. Specifically, R57A and R63A almost abolished binding while the E45A and R67A mutations resulted in 2- and 7-fold increases in Kd, respectively (Figure 2A). These RNF168R mutations diminished or prevented the ubiquitylation of H2A K15 in H2A-H2B harboring the H2A K13S mutation as shown using NMR spectroscopy and SDS-PAGE-monitored ubiquitylation assays (Figures 2H and S6A). R57A and R63A are the single point mutations that had the strongest effects (Figure S6A). Similarly, individual H2A-H2B mutations in the acidic patch such as H2A E61A and different combinations of mutations including H2A E61A, E64A and D90A, and H2B E106A and E114A strongly inhibited ubiquitylation (Figure S6B). In H2B, the K108A, K108D and K116D single point mutations also markedly decreased the ubiquitylation of H2A-H2B (Figure S6C).

In the cryo-EM structure, the interaction between RNF168R and UbcH5c is canonical and centered on a shallow cleft delimited by the two Zn2+-binding loops (aa 16–22 and 51–55) and α-helix 1 of RNF168R and two loops (aa 56–64 and 91–97) of UbcH5c (Figures 2C and 2F). There are hydrophobic contacts, with the side chains of RNF168R I18, S42 and T43 interacting with those of UbcH5c A96, F62 and P95, respectively. There are also predicted polar contacts, with the carboxylate group of E21, guanidinium group of R55 and hydroxyl group of S94 in RNF168R interacting with the ε-ammonium group of K4, amide group of Q92 and carbonyl group of P52 in UbcH5c, respectively (Figure 2F).

Through its interaction with UbcH5c, RNF168R orients UbcH5c toward the N-terminal tail of H2A in the NCP, adopting a pre-reaction conformation favorable for ubiquitin transfer to K13 and K15 (Figure 2G). The active site groove of UbcH5c, delimited by a 310 helix (aa 87–91) and a loop (aa 114–120), is proximate to the flexible side chains of H2A K13 and K15, with their α-carbons equidistant from that of UbcH5c catalytic cysteine C85 by ~10 Å (Figure 2G). There are possible contacts between UbcH5c and H2A-H2B in the NCP, which could stabilize the pre-reaction conformation of RNF168R-UbcH5c. The side chains of UbcH5c S91 and D117 in the structure may interact transiently with H2B K120 and H2A S19, respectively. UbcH5c R90 may also interact with H2A S19. However, only the D117A mutation markedly diminished the ubiquitylation of H2A-H2B and the NCP (Figures S6D and S6E). The R90A and S91A mutations had no effect on H2A-H2B ubiquitylation (Figure S6D). D117 may also play a gating role in lysine substrate ubiquitylation, as previously suggested for E2-mediated SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation.40–43

UbcH5c R125 and K128 are adjacent to nucleosomal DNA and probably contribute to the binding interface of RNF168R-UbcH5c with the NCP via electrostatic interactions. This would explain differences in ubiquitylation efficiency; the NCP being a better substrate than H2A-H2B (Figure 2B). In line with the cryo-EM structure, the UbcH5c double mutations R125E/K128E and R125S/K128S reduced NCP ubiquitylation (Figure S6E) without affecting H2A-H2B ubiquitylation (Figure S6D). As a negative control, mutating UbcH5c at K66, a residue unrelated to NCP binding, showed no impact on H2A-H2B or NCP ubiquitylation (Figures S6D and S6E). For a positive control, the UbcH5c S22R mutation, preventing ubiquitin binding to a β-sheet surface opposite active site C85, markedly reduced the efficiency of H2A-H2B and NCP mono-ubiquitylation44,45 (Figures S6D and S6E).

Interactions of RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub with the NCP in ubiquitin-loaded and pre-transfer transient state structures

We initially resorted to NMR spectroscopy to probe the RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub assembly in which Ub is the “donor” ubiquitin. We used the UbcH5c C85K mutant to produce an isopeptide bond-linked UbcH5c~Ub mimic (referred to as UbcH5c~Ub), which is more stable than the native thioester-linked conjugate.42 We prepared UbcH5c~Ub with isotopically labeled UbcH5c or ubiquitin to delineate possible interaction interfaces by NMR signal perturbations (Figure S7A). These experiments were done using UbcH5c S22R to minimize line broadening attributed to self-assembly of UbcH5c~Ub via the so-called backside interaction of UbcH5c with ubiquitin.46 As expected, ubiquitin is highly mobile in UbcH5c~Ub.47,48 The only significant changes in ubiquitin resonances are assigned to the linkage region with UbcH5c (Figure S7A). Similarly, the chemical shift perturbations in UbcH5c caused by ubiquitin attachment are restricted to the linkage site area with ubiquitin (Figure S7A). The addition of RNF168R to UbcH5c~Ub resulted in distinct chemical shift changes and line broadening in both UbcH5c and ubiquitin spectra, indicating their transient interaction triggered by RNF168R (Figure S7B). Notably, in UbcH5c, besides perturbations at the RNF168R-UbcH5c interface, allosteric changes were observed for D16 and residues S100, K101, V102, S105, N114 and D117 in the second α-helix (aa 99–111) (Figure S7B). These spectral changes support our structural model of RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub, developed using the crystal structure of RNF4 RING domain bound to UbcH5a~Ub as a template42 (Figure S7C). The ubiquitin spectrum showed signal perturbations for residues K6, I13, Q31, G35, A46, G47, K48, H68, V70, L71, R74 and G75, further supporting the RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub model (Figures S7B and S7C). Additionally, certain perturbations in the UbcH5c spectrum suggested residual ubiquitin binding to the backside surface (l37, F51) and transient binding to the C-terminus of UbcH5c (T70, Y74, H75, N77) (data not shown). Noticeably, the ubiquitin-loaded RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub structural model is compatible with the RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP cryo-EM structure, and there are no contacts between ubiquitin and the NCP surface (Figure S7D).

Next, we used cryo-EM to explore how the “donor” ubiquitin molecule in RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub might be positioned relative to the NCP surface as it is transferred to H2A K13 and K15 in a reaction catalyzed by RNF168R. We adapted a method to chemically trap a mimic of this transient or transition state where E3-E2~Ub is bound to its substrate.49,50 We first produced a proxy for UbcH5c~Ub in which K119 in the UbcH5c L119K mutant was conjugated to ubiquitin via an isopeptide bond in a reaction catalyzed by UBA1.50 The β-carbon atom of L119 only lies ~3.5 Å away from active site C85, and K119ub is expected to be sufficiently flexible to simulate the conformational freedom of ubiquitin in native UbcH5c~Ub. Assessment of this system using NMR spectroscopy was consistent with ubiquitin-conjugated UbcH5c L119K sampling the “loaded” state described above for the UbcH5c C85K-based UbcH5c~Ub mimic (Figures S7E and S7F). RNF168R addition caused UbcH5c NMR signal perturbations for D16, I99, S100, K101, V102, L104, S105, I106 and C107, all near ubiquitin in the model (Figures S7F and S7G). Similarly, there were spectral changes for ubiquitin K6, I13, Q31, E34, G35, A46, G47, K48, Q49, H68 and V70, supporting the ubiquitin-loaded RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub model (Figures S7F and S7G). Furthermore, a few spectral perturbations for UbcH5c pointed to residual backside surface ubiquitin binding (I37, F51) and transient binding to the C-terminus of UbcH5c (T70, Y74, I123) (data not shown).

We then used a bifunctional thiol crosslinker to covalently link UbcH5c C85 (in UbcH5c~Ub generated with linkage to L119K) to C15 in H2A carrying the K15C mutation in the NCP (see Methods). To ensure selectivity, the other three cysteines of UbcH5c were mutated. The standard replacement of cysteine by unreactive serine drastically diminished the activity of UbcH5c (Figure S8A). However, an optimized UbcH5c variant with the C21I, C107A and C111D mutations50 was as effective as wild type UbcH5c for RNF168R-catalyzed ubiquitin transfer to H2A K13 and K15 and was therefore used for our structural studies (Figure S8A). After addition of RNF168R to reconstituted UbcH5c~Ub-NCP, we characterized the RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP complex using cryo-EM (Figures 3A, S9, and S10; Tables S3 and S4). From these cryo-EM data, fourteen distinct structural classes ranging in resolution from 3.2 to 4.0 Å could be discerned, providing unique information about the dynamics of the system (see below). Following the same approach, we also prepared a control RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP complex in which UbcH5c is not loaded with ubiquitin and determined its cryo-EM structure at a resolution of 3.6 Å (Table S3). This structure closely matches that of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP obtained using a fusion method (Figure 2C).

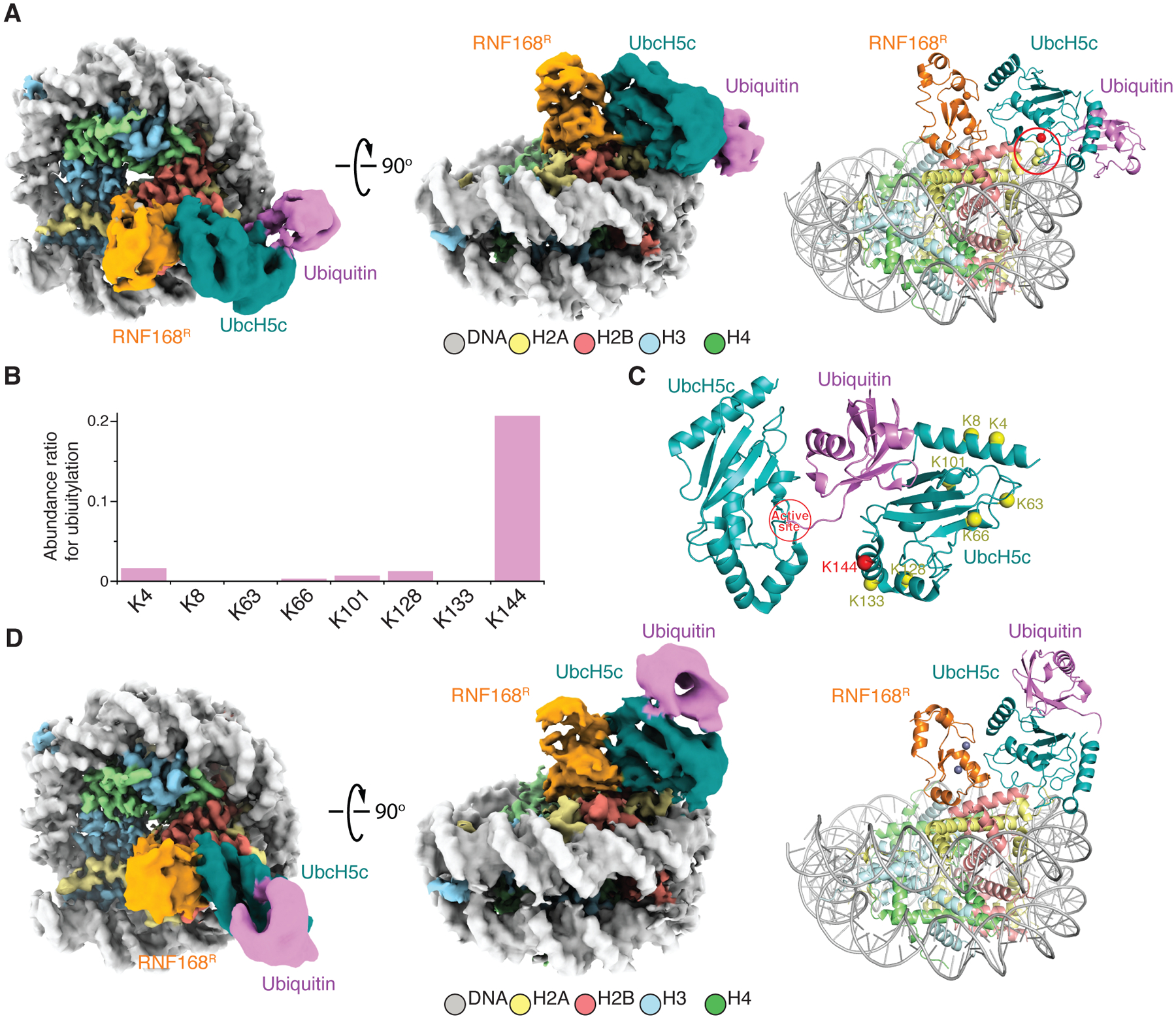

Figure 3. Cryo-EM characterization of RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP.

(A) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structural model (right) of RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP complex displayed in two orientations. Locations of H2A K13 and C15 (yellow spheres) and active site C85 of UbcH5c (red sphere) are circled in red.

(B) Self-ubiquitylation of UbcH5c at indicated lysine residues detected by mass spectrometry. An abundance ratio for each site was determined by comparing the number of fragments containing the specific lysine with ubiquitylation to the total number of fragments containing the same lysine, both with and without ubiquitylation.

(C) Proposed mechanism for UbcH5c self-ubiquitylation at K144 based on the crystal structure of UbcH5b~Ub self-assembly mediated by ubiquitin backside interaction46 (PDB 3A33). K144 in red is proximal to the UbcH5c active site.

(D) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structural model (right) of RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP complex displayed in two orientations. Zn+2 ions are purple spheres.

See also Figures S6–S10.

In six of the RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP classes, there was clear density for ubiquitin (Table S4). This transient state captured by cryo-EM suggests a preferred conformation where in the NCP context ubiquitin contacts the C-terminus of UbcH5c and nucleosomal DNA (Figures 3A and S9; Table S4). Interestingly, NMR signal perturbations noted above for the C-terminus of UbcH5c suggest that ubiquitin already samples this conformation in RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub. This state is different from the ubiquitin “loaded” state in which the donor ubiquitin does not bind the NCP surface (Figure S7D). We speculate that the interaction between ubiquitin and the NCP in the transient state “pulls” ubiquitin away from UbcH5c for facilitated transfer to H2A K13 and K15.

UbcH5c self-ubiquitylation at K144 causes ubiquitin backside binding that enhances RNF168R-catalyzed H2A ubiquitylation

When conducting NCP ubiquitylation assays with RNF168R, UbcH5c and UBA1, we discovered that UbcH5c also underwent mono-ubiquitylation at K144 (Figures 3B and S8B). While not previously reported, this self-ubiquitylation can be explained by the ubiquitin-driven self-assembly of UbcH5c~Ub,46 which, we noted, positions K144 near the “donor” ubiquitin in UbcH5c~Ub (Figure 3C). Remarkably, cryo-EM structural classes refined to resolutions of 3.9 Å and 4.0 Å revealed that the K144-linked ubiquitin molecule interacts with the backside surface of UbcH5c (UbcH5c-UbB), opposite the active site region, to form an RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP complex (Figures 3D and S9; Table S4). The cryo-EM samples were prepared without any chemical fixation, which underscores the stability of the backside interaction. Backside binding of free ubiquitin to UbcH5c or related E2s is known to allosterically stimulate ubiquitin discharge from E2~Ub and to facilitate ubiquitin transfer to the substrate by stabilizing E3-E2~Ub conformations that favor catalysis.45,51 These effects were demonstrated by using large excess of ubiquitin due to its low affinity for UbcH5c or other E2s (~300 μM Kd).44 The Kd for backside binding of free ubiquitin is significantly lowered for E3-E2~Ub complexes (~5–13 μM).45,51 As previously proposed, such backside interactions probably happen in cells, considering that the total cellular concentration of free ubiquitin is ~20–85 μM.45,51,52 Our discovery of a covalent linkage between ubiquitin and UbcH5c K144 that stabilizes backside binding suggested that K144 ubiquitylation would also enhance substrate ubiquitylation. Indeed, with this system in which ubiquitin binds UbcH5c with exactly 1:1 stoichiometry since the two are covalently linked, UbcH5c-UbB exhibited markedly higher activity than UbcH5c in generating RNF168R-catalyzed H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub in H2A-H2B (Figure S8C). Our results suggest that the activity enhancement brought about by K144 ubiquitylation could also occur in cells and be of physiological significance for the mechanism of action of RNF168. It is noteworthy that mono-ubiquitylation of UbcH5c K144 was detected in human cells using proteomics approaches53 and that this PTM was shown to be required for maintaining KRAS protein stability.54

Interaction of RNF168R-UbcH5c with NCPub in post-reaction state structures

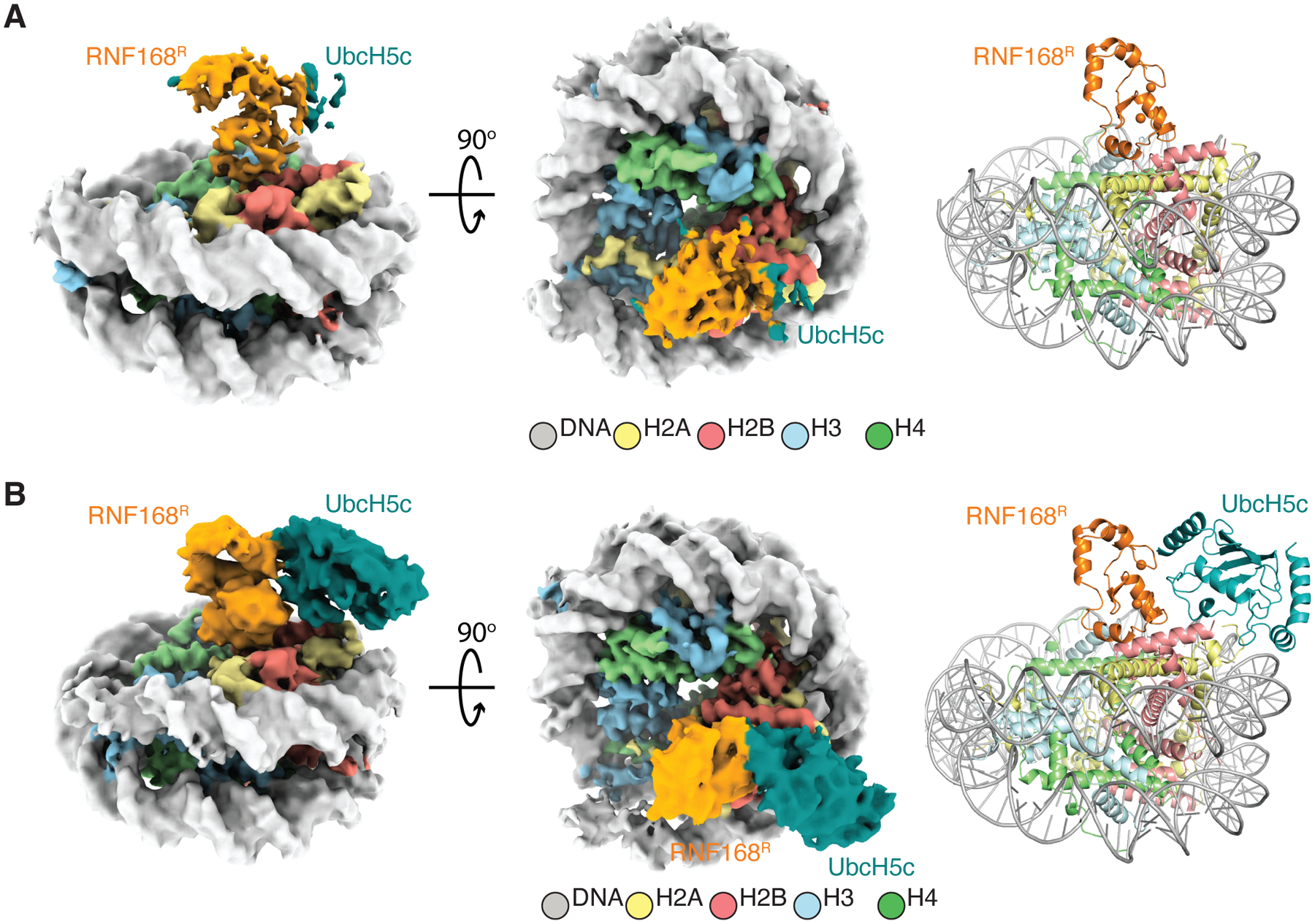

Next, we probed the structure of RNF168R-UbcH5c in the context of product NCP where H2A K15 is already ubiquitylated (NCPub). To prevent ubiquitylation of the other site, H2A K13 was changed to a serine. For structural characterization using cryo-EM, we assembled an NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c fusion complex to approximate the post-reaction state. We derived two final 3D classes at resolutions of 3.8 Å and 3.9 Å that we interpreted as two transient conformational states of NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c (Figures 4 and S11; Table S2). Noticeably, in both classes, RNF168R remains docked to the NCP akin to the pre-reaction state, but UbcH5c fluctuates. For the first NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c class, the density of RNF168R is quite broad, indicative of conformational heterogeneity. The extremely faint density of UbcH5c also highlights conformational heterogeneity and suggests that ubiquitin in NCPub destabilizes the RNF168R-UbcH5c interaction (Figure 4A). For the second class, the densities of RNF168R and UbcH5c are clearly discernible, revealing that RNF168R-UbcH5c binds NCPub akin to the pre-reaction state (Figures 4B and 2C). In both classes, there is no visible density for ubiquitin, indicating that ubiquitin is flexible even if it influences the positioning of UbcH5c in the NCP. These two dynamic NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c assemblies where UbcH5c oscillates between a ubiquitylation-proficient conformation and a “free” conformation suggest that a single ubiquitin molecule favors the release of UbcH5c from the NCP. That pre-reaction and dissociated states co-exist in the post-reaction sample makes sense considering that RNF168R-UbcH5c catalyzes ubiquitin transfer to two sites: H2A K13 and K15.

Figure 4. Cryo-EM structures of post-reaction states where the NCP has been ubiquitylated by RNF168R-UbcH5c.

(A) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structure (right) of post-reaction state 1 (class 1) of the NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c complex. Density is visible for RNF168R, but barely noticeable for UbcH5c.

(B) Cryo-EM reconstruction (left and middle) and structure (right) of post-reaction state 2 (class 2) of the NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c complex. UbcH5c density matches that in the pre-reaction state in Figure 2C.

See also Figure S11.

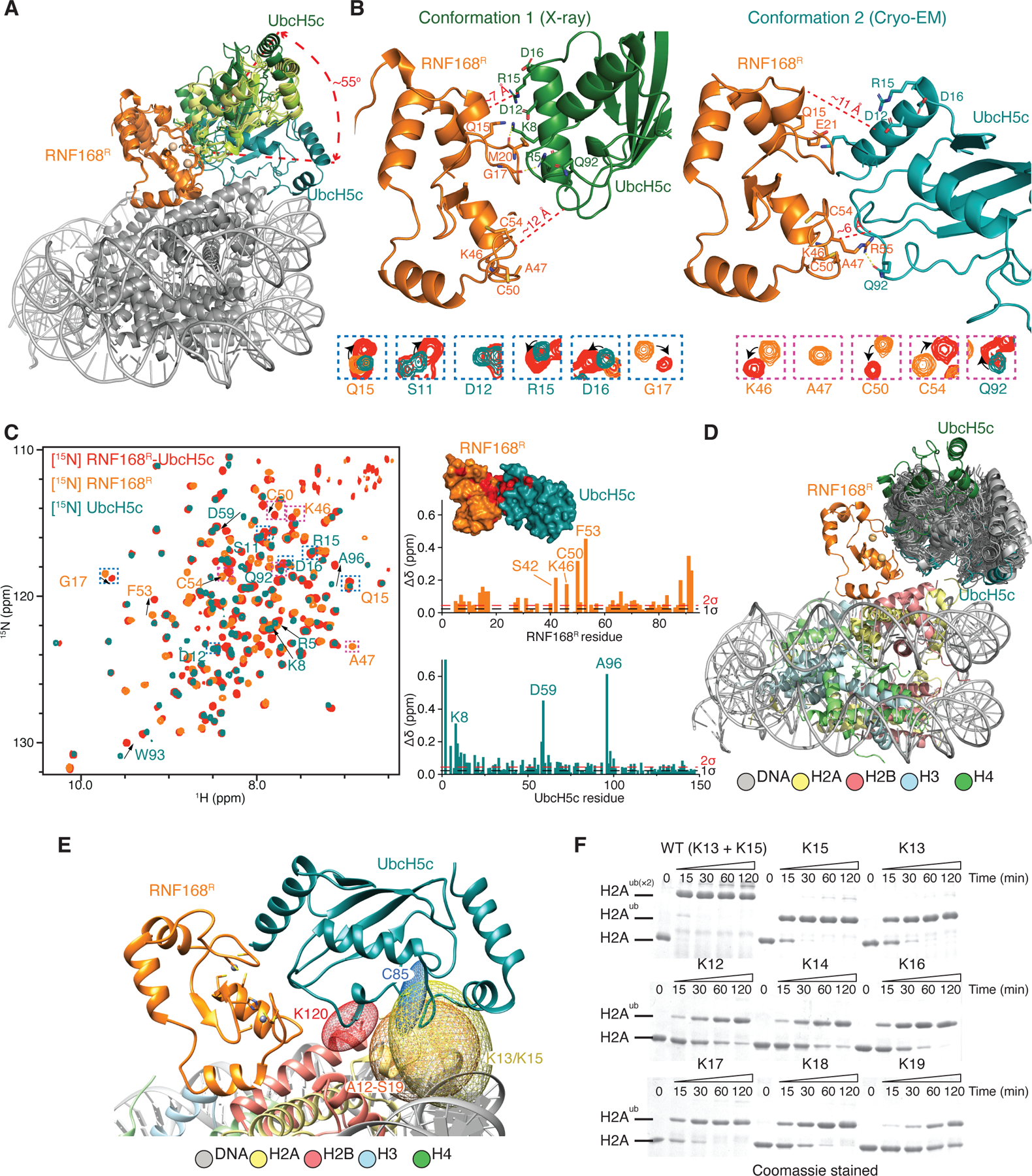

RNF168-UbcH5c samples multiple conformations underlying its ubiquitylation zone

Molecular flexibility must contribute to the specificity of NCP ubiquitylation by RNF168R-UbcH5c, transiently positioning UbcH5c near the two ubiquitylation sites, H2A K13 and K15. Moreover, structural fluctuations probably facilitate the displacement of UbcH5c from the NCP surface once ubiquitylation is completed.

We have evidence that RNF168R-UbcH5c alone adopts a wide range of conformations, suggesting that conformational selection55 drives its interaction with H2A-H2B or the NCP. Five different crystal structures we determined for RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B fusion constructs varying only in linker lengths between UbcH5c and H2A-H2B revealed three different relative orientations of RNF168R and UbcH5c, while two additional crystal structures showed no density for RNF168R (Figure 5A; Table S5). These structures could not recapitulate how RNF168R-UbcH5c binds H2A-H2B in solution due to steric hindrance caused by crystal packing contacts (data not shown). Nevertheless, the variability in the orientation of RNF168R with respect to UbcH5c or the lack of density for RNF168R highlights conformational flexibility. In comparison to the RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP cryo-EM structures, in the crystal structures UbcH5c pivots by up to 55° relative to the NCP circular surface (Figure 5A). These more open conformations are caused by rearrangements at the RNF168R-UbcH5c interface. For example, the hydrogen bonds in one of the cryo-EM structures bridging RNF168R E21 and R55 with UbcH5c K4 and Q91, respectively, are replaced by new hydrogen bonds involving the carbonyls of RNF168R M20 and G17 and the ε-ammonium and guanidinium groups of UbcH5c K8 and R5, respectively (Figure 5B). When superimposed with respect to RNF168R, these cryo-EM and crystal structures suggest a spectrum of conformations that may reflect dynamic fluctuations at the RNF168R-UbcH5c interface in solution (Figure 5A). In agreement with different RNF168R-UbcH5c conformations co-existing in solution, chemical shift changes in the 1H-15N NMR correlation signals of RNF168R and UbcH5c upon complex formation agree with the presence of at least two interfacial conformations that would match the crystal structure with the most “open state” and the cryo-EM structure representing a “closed state” relative to the NCP circular surface (Figures 5B and 5C). Noticeably, these pre-existing open and closed states of RNF168R-UbcH5c bracket a continuum of conformations obtained from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations initiated using RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B in the cryo-EM structure (Figure 5D). Related conformational variability is also seen in the overlay of 16 different crystal structures of other E3-E2 pairs with conserved interfacial residues (Figures S12A and S12B). MD simulations of RNF168R-UbcH5c using the crystal (open and closed states) and cryo-EM structures as starting models also reveal a wide range of conformations (Figures S12C and S12D). These results are consistent with a conformational selection mechanism55 in substrate recognition, where the conformations of RNF168R-UbcH5c when bound to the NCP represent a subset of its conformations in the absence of substrate.

Figure 5. Conformational dynamics of RNF168R-UbcH5c.

(A) Overlay of three RNF168R-UbcH5c structures (from crystal structures of RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B and the cryo-EM structure of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP), aligned with respect to RNF168R. UbcH5c samples multiple conformations, pivoting by as much as ~55° from the N-terminus of UbcH5c α-helix 1.

(B) Top: Representative crystal structure (conformation 1 or open state) of RNF168R-UbcH5c and cryo-EM structure (conformation 2 or closed state) of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP both from A showing only the RNF168R-UbcH5c moiety. Selected residues are labeled and approximate distances between RNF168R and UbcH5c in both conformations are indicated. Bottom: RNF168R-UbcH5c NMR signals that are affected by the RNF168R and UbcH5c interaction (see spectral overlay in C (left)) define interfaces consistent with both X-ray and cryo-EM structures.

(C) Left: Overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R and UbcH5c. RNF168R-UbcH5c signals that differ from corresponding signals in isolated RNF168R and UbcH5c are highlighted by arrows or boxed (and enlarged in B (bottom)). Right: Plot of the chemical shift differences between the spectra of RNF168R-UbcH5c and RNF168R (top) and between the spectra of RNF168R-UbcH5c and UbcH5c (bottom). One and two standard deviations (1σ and 2σ) above the mean chemical shift are indicated. Inset: Surface representation of RNF168R-UbcH5c. RNF168R-UbcH5c residues with ≥ 0.1 ppm chemical shift deviation from those in isolated RNF168R and UbcH5c are colored red.

(D) Summary of a 1-μs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of RNF168R-UbcH5c bound to H2A-H2B using the cryo-EM structure of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP as starting model. Fifty simulated RNF168R-UbcH5c models (gray) are overlaid relative to their E3 components. For comparison, RNF168R-UbcH5c conformations 1 (open state from a crystal structure) and 2 (closed state in the cryo-EM structure) are also included.

(E) Determination of the ubiquitylation zone of RNF168R-UbcH5c using the MD simulations in D. Five-hundred atomic coordinates sampled from the 1-μs MD simulation were used to evaluate changes in atomic positions and predict which residues could be ubiquitylated if they were lysines. Ellipsoids generated using the “measure inertia” function of Chimera were used to approximate the spatial distributions of atoms from selected residues in the MD simulation. The ellipsoids shown are for UbcH5c active site C85 SG (blue), H2A K13 and K15 NZ (yellow), H2A non-lysine residues A12 to S19 CA (orange), and H2B K120 NZ (red).

(F) H2A-H2B ubiquitylation by RNF168R, UbcH5c and UBA1 at indicated H2A lysine residues monitored using SDS-PAGE.

See also Figure S12.

Structural variability analysis56 of the cryo-EM data shows a scanning motion of UbcH5c relative to the NCP surface (Video S2). Despite the flexibility of RNF168R-UbcH5c, R63 of RNF168R stays in place in the NCP acidic patch region in 14 cryo-EM classes for RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP, RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP (Figures S12E and S12F; Video S3). From the MD simulations of RNF168R-UbcH5c bound to H2A-H2B, we could estimate the extent of motion accessible to RNF168R, UbcH5c and H2A N-terminal within the NCP context (Figure 5D). This analysis defines the ubiquitylation zone of RNF168R-UbcH5c, where substrate ubiquitylation can occur under certain criteria (Figure 5E). Histone H2B K120, which does not get ubiquitylated by RNF168R-UbcH5c, lies outside the ubiquitylation zone. We predicted that several H2A residues within this ubiquitylation zone would be modified if they were lysines. Testing this prediction, we incorporated a lysine at H2A positions 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 one at a time, and performed ubiquitylation assays on H2A-H2B. All these sites could be modified by RNF168R-UbcH5c, albeit less efficiently than wild type H2A (Figure 5F). Therefore, the specificity of ubiquitylation by RNF168R is determined by a restricted area of action and the presence of only two lysines within this area, H2A K13 and K15. The MD simulations were conducted without ubiquitin loaded onto UbcH5c; ubiquitin may further restrict the motions of RNF168R-UbcH5c.

DISCUSSION

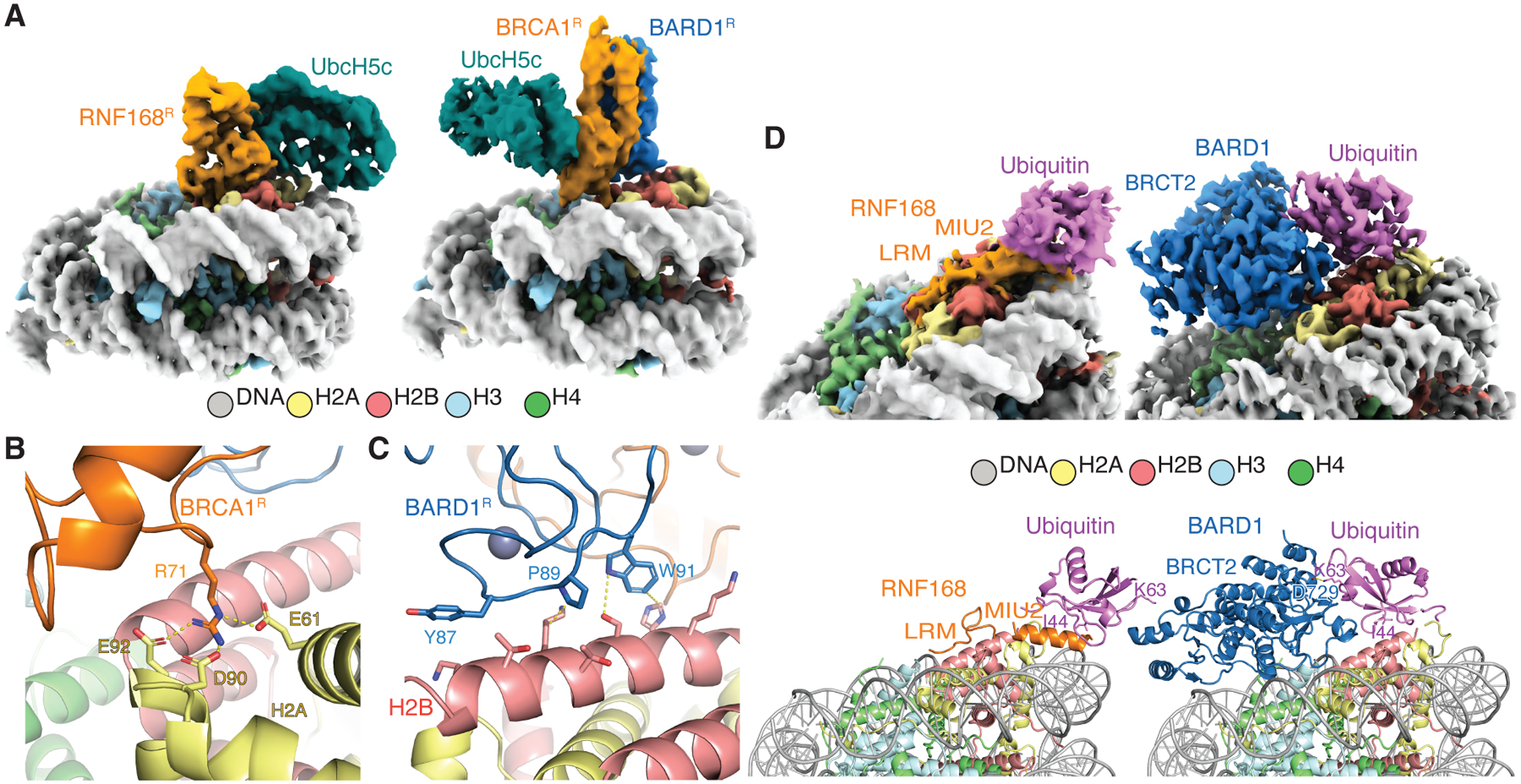

Origin of the distinct ubiquitylation site specificities of RNF168 and BRCA1-BARD1

RNF168 and BRCA1-BARD1 are E3 ubiquitin ligases using a common E2 (UbcH5c) to target opposite regions of histone H2A. A RING domain heterodimer in BRCA1-BARD1 (BRCA1R-BARD1R) binds UbcH5c via BRCA1R to ubiquitylate the C-terminal tail of H2A at K125, K127 and K129 in the NCP (Figure 6A). BRCA1R-BARD1R is anchored to the NCP by BRCA1R R71 which, like RNF168R R63, interacts with the NCP acidic patch residues H2A E61, D90 and E92 (Figures 2E and 6B).15,25,57 RNF168R and BRCA1R-BARD1R orient UbcH5c toward the N- and C-terminal tails of H2A, respectively, explaining their distinct specificities. These ~180° opposite orientations of UbcH5c in RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP and BRCA1R-BARD1R-UbcH5c-NCP originate from direct contacts between RNF168R or BARD1R and histone H2B (Figures 2D and 6C). For RNF168R, the interaction is mainly electrostatic with its first α-helix binding the C-terminal α-helix of H2B (Figure 2D). For BRCA1R-BARD1R, a loop in BARD1R (aa 87–91) participates in polar and hydrophobic contacts with the C-terminal α-helix of H2B15 (Figure 6C). This highlights how a single RING domain in RNF168 and two RING domains in BRCA1-BARD1 mediate E3-E2 anchoring in a defined orientation on the NCP surface.

Figure 6. NCPub recognition and ubiquitylation by RNF168 and BRCA1-BARD1.

(A) Cryo-EM structures of RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP and BRCA1R-BARD1R-UbcH5c-NCP.15 The NCPs are oriented similarly to highlight the opposite positioning of UbcH5c by ~180° in the two complexes.

(B and C) Close-up views of the interactions between BRCA1R and H2A-H2B acidic patch (B), and between BARD1R and H2B C-terminal α-helix (C).

(D) Cryo-EM reconstructions (top left and right) and structural models (bottom left and right) illustrating ubiquitin recognition in NCPub by RNF168 and BARD1.15 The side chains of ubiquitin I44 and K63 are shown to highlight the radically different ubiquitin recognition modes. The side chain of D729 in BARD1 forms a polar interaction with K63 (yellow dashed line).

Similar to RNF168R-UbcH5c, BRCA1R-BARD1R-UbcH5c exhibits dynamic conformational variability, likely influencing the targeting of lysine residues in the flexible tails of H2A through a “fly-casting mechanism.” Notably, there is a difference in the number of residues separating the folded NCP core from the first modified lysine in the N- and C-terminal H2A tails: one versus six, respectively. The amplitudes of motion are smaller for RNF168R-UbcH5c than for BRCA1R-BARD1R-UbcH5c (Video S2). RNF168R binds more tightly to the NCP (Kd ~0.4 μM) than BRCA1R-BARD1R (Kd ~8 μM),15 aligning with the latter’s more dynamic interaction. This difference in affinities underscores the distinct dynamic behaviors of these ubiquitylation systems.

Ubiquitin recognition in the NCP by RNF168 and BRCA1-BARD1

RNF168 binds H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub via the MIU2-LRM region. The shared acidic patch binding interface between RNF168 RING domain and MIU2-LRM precludes simultaneous occupation on the same NCP surface. MIU2-LRM interaction with a ubiquitylated NCP likely promotes ubiquitylation of neighboring NCPs, enhancing RNF168 recruitment to chromatin following DNA damage. The NCPub binding mode of MIU2-LRM illustrates how a canonical UBD, the MIU motif,58 which can recognize free ubiquitin in an interaction centered on ubiquitin residue I44, also transiently interacts with the NCP surface (i.e., the target), supporting ubiquitin site specificity. This novel mechanism for site-specific recognition of a ubiquitylated target implies that other canonical UBDs may similarly encode target site specificity.

The NCPub binding mechanism of RNF168 contrasts with that of BRCA1-BARD1, which also recognizes H2AK13ub or H2AK15ub.15,16 BARD1, through its second BRCT domain (BRCT2), interacts with the NCP acidic patch and ubiquitin in NCPub, stabilizing a conformation where ubiquitin I44 interacts with the C-terminal α-helix of H2B (Figure 6D).15,16 Unlike RNF168, BARD1 lacks a UBD and cannot bind free ubiquitin. In its binding interface with ubiquitin in NCPub, BARD1 BRCT2 interacts with ubiquitin K63, inhibiting the extension of ubiquitin chains at K63 in vitro15 (Figure 6D). This distinguishes it from RNF168, which leaves K63 accessible (Figure 6D). The physiological significance of this inhibition by BRCA1-BARD1 is not known; it may regulate the BRCA1-A (ARISC-RAP80) DNA repair complex59 present at replication forks. Future work is needed to test this hypothesis. RNF168, by not inhibiting ubiquitin chain extension, may partner with other E2 enzymes for ubiquitin chain formation,60 while maintaining its signal amplification capability.

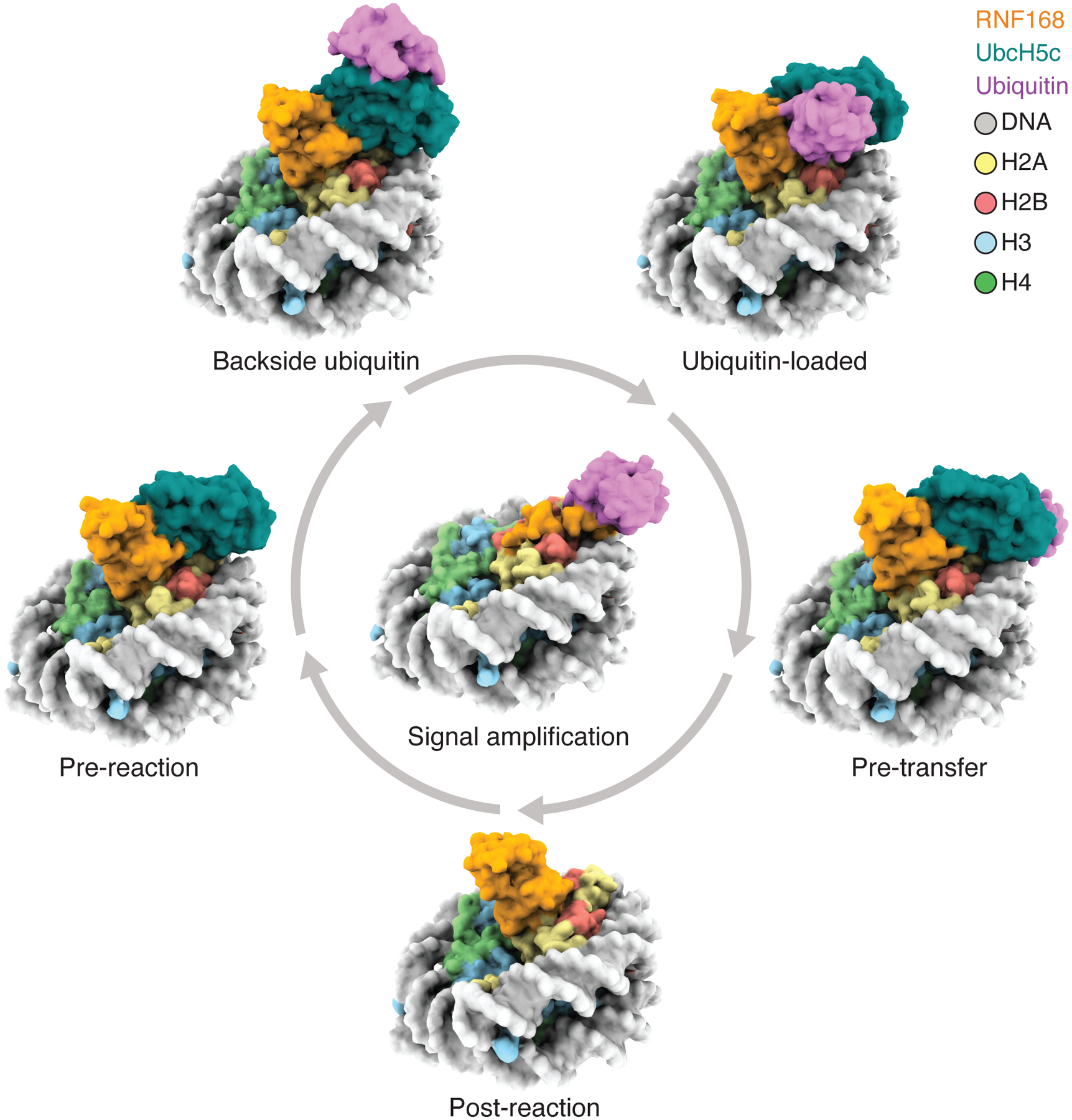

The reaction cycle of RNF168

We have explored the reaction mechanism of RNF168R-UbcH5c in chromatin ubiquitylation. The different approaches we used to capture RNF168R and UbcH5c in their association with the NCP converge to a similar binding mode of RNF168R, wherein atop the NCP, RNF168R dynamically orients UbcH5c toward an N-terminal segment of H2A, effectively priming ubiquitin transfer to K13 and K15. We determined multiple structures, interpreted as distinct steps or states contributing to the reaction cycle of RNF168R-UbcH5c in H2A ubiquitylation. We distinguish four states— pre-reaction, ubiquitin-loaded, pre-transfer and post-reaction states. These states illustrate transient inter-molecular interactions driving ubiquitin from the thioester linkage with UbcH5c to the isopeptide bonds with the amine ends of H2A K13 and K15 (Figure 7). We also report a step where RNF168 recognizes its own ubiquitylation products, promoting signal amplification (Figure 7). Notably, the structural basis for the initial recruitment of RNF168 to damaged chromatin remains to be established. This step likely involves the recognition, via RNF168 UMI and MIU1 domains, of ubiquitin chain-modified chromatin components such as histone H1.61–63 Additionally, we discovered a self-ubiquitylated form of UbcH5c at K144 that stabilizes a backside ubiquitin-bound conformation of UbcH5c and enhances RNF168R-catalyzed ubiquitin transfer from UbcH5c to H2A K13 and K15 (Figure 7). We speculate that this activating conformation of UbcH5c is an integral part of the reaction mechanism in cells, not only for RNF168 but also for other UbcH5c cognate E3 ubiquitin ligases like BRCA1-BARD1.

Figure 7. Reaction cycle of RNF168.

Reaction cycle of RNF168. Various modes of interactions of RNF168, RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub or RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB with the NCP or NCPub are interpreted as different steps or states of the reaction cycle, leading to H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub signal amplification in chromatin.

Limitations of the study

We determined the structure of MIU2-LRM bound to NCPub within the context of full-length RNF168 (RNF168FL). Despite the ~30-fold stronger binding of RNF168FL to NCPub compared to MIU2-LRM, no additional RNF168FL regions were observed in the cryo-EM density. This suggests that MIU2-LRM acts as a chromatin anchor region, while the RING domain and possibly other segments of RNF168FL transiently bind to NCPub. These segments collectively contribute to the overall affinity of RNF168FL for NCPub, influencing the ubiquitylation reaction. We used genetic and chemical linking approaches to visualize RNF168R or RNF168R-UbcH5c binding in various states, interpreting them as steps along the reaction path. However, to visualize the dynamic stages of NCP recognition and ubiquitylation within the context of RNF168FL, novel methods will be necessary.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further Information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Georges Mer (mer.georges@mayo.edu).

Material availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

The structural data including atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and/or Protein Data Bank (PDB). The EMDB/PDB identification codes for the cryo-EM-related data are: EMD-41706/8TXV, EMD-41707/8TXW, EMD-41708/8TXX (for RNF168-NCPub classes); EMD-42446/8UPF (for RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP); EMD-40604/8SMW, EMD-40605/8SMX, EMD-40606/8SMY, EMD-40607/8SMZ, EMD-40608/8SN0, EMD-40609/8SN1 (for RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP classes with no ubiquitin in density); EMD-40610/8SN2 (for RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP); EMD-40611/8SN3, EMD-40612/8SN4, EMD-40613/8SN5, EMD-40614/8SN6, EMD-40615/8SN7, EMD-40616/8SN8 (for RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP classes); EMD-40617/8SN9, EMD-40618/8SNA (RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP); EMD-41800/8U13, EMD-41801/8U14 (for NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c). The PDB identification codes for the different crystal structures of RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B are 8UQ8, 8UQ9, 8UQA, 8UQB, 8UQC, 8UQD and 8UQE. Raw image data have been deposited at Mendeley Data under: https://doi.org/10.17632/nz8sknt9zj.1

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

METHOD DETAILS

Protein expression and purification

The proteins used for this work have the human sequences. Various mutations were introduced by standard site-directed mutagenesis. The proteins include histones H2B (aa 33–123)-H2A (aa 12–105) (designated as H2A-H2B), H2B (aa 1–123)-H2A (aa 12–129) (designated as H2A-H2BL), H3 (aa 1–135), and H4 (aa 1–102), all with an N-terminal His6-tag cleavable by human rhinovirus 3C (HRV3C) protease (in pHISPP vector), N-terminally His6-tagged ubiquitin or Ub (non-cleavable in pT7 and cleavable in pHISPP vectors), UbcH5c (aa 1–147) (in pT7 and pHISPP vectors), UBA1 (in pET21d vector), RNF168R (aa 1–94) (in pET22b vector), and full-length RNF168 (aa 1–571) with non-cleavable C-terminal His6-tag and an N-terminal MBP-tag cleavable by HRV3C protease (designated as MBP-RNF168FL), and RNF168 MIU2-LRM (aa 430–481) with N-terminal His6-tag cleavable by TEV protease (in pTEV vector). RNF168R (aa 1–94) is more stable and as efficient in ubiquitylating H2A-H2B and H2A-H2BL as the longer RNF168 RING constructs used in previous crystallography studies (data not shown). 64,65 In H2A-H2B and H2A-H2BL, a serine residue bridges H2A and H2B. 33

For single-particle cryo-EM experiments, a chimeric RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL construct, with 6- and 26-aa linkers between RNF168R and UbcH5c, and between UbcH5c and H2A-H2BL, respectively, was engineered. A second chimeric construct, H2A-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c, with 10- and 6-aa linkers between H2A-H2BL and RNF168R, and between RNF168R and UbcH5c, respectively, was likewise made. Both constructs were cloned in the pDB.His.MBP vector, conferring to the proteins an N-terminal His6-MBP-tag that can be cleaved by TEV protease. The RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL and H2A-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c proteins, with or without ubiquitylation at H2A K15, were used to reconstitute NCP samples for cryo-EM experiments. Additional NCP samples containing a mimic of UbcH5c~Ub were also prepared. All NCPs prepared in this study have the longer H2A-H2B version (i.e., H2A-H2BL).

For crystallization trials, multiple chimeric constructs of RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B and H2A-H2B-RNF168R-UbcH5c linking RNF168R (aa 1–94), UbcH5c (aa 1–147), and H2A-H2B were cloned in the pDB.His.MBP vector, conferring to the proteins an N-terminal His6-MBP-tag cleavable by TEV protease. Additionally, chimeric constructs of RNF168R-UbcH5c (cloned in pDB.His.MBP) and UbcH5c-H2A-H2B (cloned in pHISPP) were also prepared. In these constructs, the lengths of the linkers (n), consisting of glycine and serine residues, and placed between RNF168R and UbcH5c (n=6), and between UbcH5c and H2A-H2B (n= 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20 and 26) were varied. Samples with both non-ubiquitylated and C85K ubiquitylated UbcH5c moieties were tested in the trials. Seven crystal structures were successfully determined.

Full-length RNF168 was produced in Rosetta(DE3) E. coli cells. All other proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells. Cells transformed with histones H2A-H2B, H2A-H2BL, H3 or H4 constructs were grown at 37 °C in LB or isotope-enriched M9 media to OD600 ~0.6 and induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 3 h. Cells transformed with the other plasmids were grown similarly but induced at 15 °C for ~16 h. For RNF168R-containing constructs, 100 μM ZnCl2 was added to the culture media prior to induction.

Harvested cells were lysed using an Emulsiflex C5 homogenizer (Avestin). H2A-H2B, H2A-H2BL, H3, H4, UBA1, UbcH5c, RNF168R, RNF168 MIU2-LRM and ubiquitin were purified following published protocols.15,65–69. MBP-RNF168FL was initially purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni+2-NTA) agarose chelation chromatography (Qiagen) using solutions of 50 mM sodium phosphate (NaPi), 1 M NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), pH 7.5, with 5, 20 and 250 imidazole to bind, wash, and elute the proteins, respectively. HRV3C was added to the eluted protein and the mixture was dialyzed overnight in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. Upon MBP cleavage, sample was injected into a HiPrep Heparin FF 16/10 column (Cytiva) and RNF168FL was collected in the flow through. RNF168FL was further purified with a 5-mL HisTrap Ni Sepharose column (Cytiva) using a gradient of 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.5, with 0 mM imidazole and 250 mM imidazole. Finally, RNF168FL was buffer-exchanged in 50 mM NaPi, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, and concentrated using Amicon centrifugal tubes (MilliporeSigma). For the various chimeric constructs cloned in pDB.His.MBP (e.g. RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL, H2A-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B, H2A-H2B-RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c), or in pHISPP (e.g. UbcH5c-H2A-H2B and UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL), the proteins were likewise initially purified by Ni+2-NTA chelation chromatography using solutions of 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5, with 5, 10 and 250 mM imidazole to bind, wash, and elute the proteins, respectively. Eluted proteins were next concentrated and then digested with TEV or HRV3C proteases. UbcH5c-H2A-H2B and UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 column (Cytiva) equilibrated with 50 mM NaPi, 300 mM NaCl, pH 6.0. On the other hand, RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL, H2A-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B, H2A-H2B-RNF168R-UbcH5c and RNF168R-UbcH5c were further purified with a 5-mL HisTrap Ni Sepharose column using a gradient of 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5, with 5 mM imidazole and 250 mM imidazole. Proteins of interest eluted at ~30 mM imidazole. The NaCl concentration in the purified proteins were lowered to ~100 mM before using for ubiquitylation reactions or adjusted to 2 M before using for octamer reconstitutions. Samples used for crystallization trials were buffer exchanged in 10 mM HEPES, 600 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. Samples used for NMR experiments were buffer exchanged in 50 mM NaPi, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP, pH 7.5.

Ubiquitylation reactions

Ubiquitylation of H2AK13S-H2B (likewise for H2AK13S-H2BL, RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2AK13S-H2BL, H2AK13S-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2AK13S-H2B and H2AK13S-H2B-RNF168R-UbcH5c) at a final concentration of 80 μM was carried out in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1.6–3.2 μM UBA1, 120 μM ubiquitin and 3 mM ATP. The reaction mixture was incubated at 32 °C for 1 h, reaching 100% ubiquitylation, and then quenched by addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 1 M. The resulting ubiquitylated sample was purified with a 5-mL HisTrap Ni Sepharose column using a gradient of 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5, with 5 mM imidazole and 250 mM imidazole.

UbcH5c-H2A-H2B and UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL proteins containing C85K in UbcH5c were also ubiquitylated. Typically, the reaction mixture containing 80 μM UbcH5c-H2A-H2B or UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL protein, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1.6–3.2 μM UBA1, 120 μM pT7 ubiquitin and 3 mM ATP was incubated at 32 °C for 24 h. The reaction was quenched with 1 M NaCl and the ubiquitylated protein purified using a 5-mL HisTrap Ni Sepharose column as described above. The ubiquitylation efficiencies were ~70%.

A mimic of UbcH5c~Ub was prepared by enzymatic ubiquitylation of K119 in UbcH5c harboring the C21I/C107A/C111D/L119K mutations. Ubiquitylation was carried out by combining 2 μM UBA1, 100 μM mutated UbcH5c, 120 μM ubiquitin (with cleavable His6-tag) and 3 mM ATP in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2 and 1 mM TCEP, and incubating the mixture at 32°C for 1 h. The reaction was quenched by addition of 1 M NaCl. The mixture was passed through a SEC Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M NaCl, pH 7.5. Fractions with UbcH5c~Ub were then pooled, buffer-exchanged in 50 mM NaPi, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5, and concentrated. Next, the UbcH5c~Ub mimic active site cysteine C85 was covalently linked via the bifunctional thiol cross-linker 1,3-dichloroacetone (DCA)70 to C15 of H2A carrying the K15C mutation in H2A-H2BL, producing UbcH5c~Ub-H2A-H2BL. In such reaction, 100 μM each of UbcH5c~Ub mimic and H2A-H2BL were combined in 50 mM sodium borate, pH 8.5, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min and then in ice for 5 min. The reaction was initiated by adding 120 μM DCA from a freshly prepared 2 mM stock in dimethylformamide. After a 30 min incubation in ice, the reaction was quenched with 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. The sample was next purified by SEC using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (Cytiva) equilibrated with 50 mM NaPi, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. Fractions containing UbcH5c~Ub-H2A-H2BL were then pooled and further purified using a 5-mL HisTrap HP and a gradient of 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.5 buffers, without and with 250 mM imidazole. Eluted UbcH5c~Ub-H2A-H2BL fractions were pooled and incubated with HRV3C protease at 4°C overnight to cleave the His6-tag on the Ub moiety.

Covalent linkage via DCA was also used for the preparation of H2A-H2BL (with K15C mutation) linked to UbcH5c (with C21I/C107A/C111D/L119K mutations), producing UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL. Similar steps as above were followed except that the cleavable His6-tag that was cut was on the H2A-H2BL portion.

When using the purified H2A-H2BL-containing products above to make octamers, the NaCl concentration was increased to 2 M prior to addition of H3-H4.

Preparation of nucleosomes

To form the H3-H4 tetramer, individually purified H3 and H4 were mixed and renatured as reported.71,72 The refolded H3-H4 tetramer was next digested with HRV3C protease and then purified by SEC using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5 (octamer buffer).

To form the octamer, H3-H4 tetramer and H2A-H2BL were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 in the octamer buffer and injected into a HiLoad 16/60 SEC Superdex 200 or Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL columns equilibrated with the octamer buffer. Following published procedures, the mono-NCP was reconstituted by gradient dialysis of the 1:1 mole ratio mixture of the octamer and the 147-bp Widom 601 DNA, and then purified using a 6-mL Resource Q column (Cytiva).33,73 Finally, the NCP was dialyzed in 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5, and stored in ice for immediate use. Similar steps were followed for the preparation of the di-NCP. A mixture containing 2:1 mole ratio of the octamer and the 309-bp L15 DNA (two 147-bp Widom 601 linked by 15-bp)74 was assembled for gradient dialysis.

To prepare NCPs ubiquitylated at H2A K15, H2A-H2BL harboring a K13S mutation was first enzymatically ubiquitylated (see the ubiquitylation reactions section above) prior to octamer and subsequent NCP reconstitution. To prepare NCPs ubiquitylated at both K13 and K15, wild type (WT) H2A-H2BL was used. The NCP or di-NCP ubiquitylated at H2A K15 is referred to as NCPub or di-NCPub (unless specified otherwise).

Using RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL, H2A-H2BL-RNF168R-UbcH5c, UbcH5c~Ub-H2A-H2BL or UbcH5c-H2A-H2BL in lieu of H2A-H2BL (with or without mutation) above, various other unmodified or ubiquitylated NCP complexes (e.g., RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP, NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c, UbcH5c~Ub-NCP or UbcH5c-NCP) were reconstituted.

X-ray crystallography

RNF168R-UbcH5c-H2A-H2B, H2A-H2B RNF168R-UbcH5, RNF168R-UbcH5c and UbcH5c-H2A-H2B constructs, with WT sequence or K13S/R mutation in H2A or S22R/C85K mutations in UbcH5c (without or with ubiquitylation), were subjected to crystallization trials. In the end, crystals of RNF168R-UbcH5c-2aa-H2A-H2B, RNF168R-UbcH5c-4aa-H2A-H2B, RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-12aa-H2A-H2B, RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-20aa-H2A-H2B, and RNF168R-UbcH5cS22R/C85K-26aa-H2A-H2B (n=2, 4, 12, 20 and 26 between UbcH5c and H2A-H2B) were produced by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method carried out at 15 °C. Crystals of RNF168R-UbcH5c-2aa-H2A-H2B (9.5 mg/mL) and RNF168R-UbcH5c-4aa-H2A-H2B (8.8 mg/mL) were obtained by mixing 2 μL of the protein in 10 mM HEPES, 600 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5, and 2 μL of the reservoir solution containing 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5, 2.4 M NaCl. Other crystals were obtained similarly but with the following reservoir solutions: 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5, 2.4 M NaCl for RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-12aa-H2A-H2B (8.0 mg/mL); 50 mM BIS-TRIS propane, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl (condition 1) and 4% tacsimate, pH 6.0, 13.5% PEG 3350 (condition 2) for RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-20aa-H2A-H2B (12 mg/mL); and 0.1 M imidazole, pH 6.5, 1.0 M sodium acetate for RNF168R-UbcH5cS22R/C85K-26aa-H2A-H2B (10 mg/mL). All crystals were cryoprotected with 30% (v/v) glycerol, mounted in loops and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the 19BM beamline of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Crystallographic datasets were indexed, integrated and scaled with HKL200075, and the structures solved by molecular replacement using PHENIX PHASER76,77 with the crystal structures of RNF168R (PDB 4GB0)69, UbcH5c (PDB 5EGG),78 and fused H2A-H2B (unpublished data) serving as search models. The space group was P 31 for the RNF168R-UbcH5c-2aa-H2A-H2B and RNF168R-UbcH5c-4aa-H2A-H2B crystals, with 2 copies of the molecule in the asymmetric unit. For RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-12aa-H2A-H2B, RNF168R-UbcH5cC85K-20aa-H2A-H2B and RNF168R-UbcH5cS22R/C85K-26aa-H2A-H2B crystals, the space groups were all P 32 2 1, with one molecule each in the asymmetric unit. The structures were refined using PHENIX REFINE79 and COOT.80 The structures were validated with MolProbity and through the PDB validation website (https://validate-rcsb-1.wwpdb.org). All molecular graphic representations were generated using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Versions 2.3.2 Schrodinger, LLC) and UCSF Chimera81 or ChimeraX.82

Cryo-EM sample preparation

For cryo-EM characterization, the RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP and NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c samples were stabilized using mild on-column glutaraldehyde cross-linking.15,83 A SEC Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column was first equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5, and then 200 μL of a 0.25% (v/v) glutaraldehyde solution was injected. Six mL of this buffer was passed through the column at a rate of 0.3 mL/min before the run was halted. The loading loop was cleaned extensively and 500 μL solution of 6.9 μM RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP (or 4.8 μM NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c) was then injected. The run was continued at a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. Fractions of interest were concentrated to 0.4 mg/mL. Cross-linking efficiency was assessed using 12% SDS-PAGE and 5% native PAGE. Following cross-linking, grids were prepared by applying 3.5 μL of the sample to a glow-discharged holey Cu grid (Quantifoil R 1.2/1.3, 300 mesh, EMS Acquisition Corporation) mounted in the chamber of an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV maintained at 4 °C and 100% humidity. The grids were blotted for 4 sec at a blotting force of 0 followed by plunging into liquid ethane.

The cryo-EM samples in which RNF168R was added to UbcH5c~Ub-NCP or UbcH5c-NCP were prepared without cross-linking, adding 36- and 20-fold molar excess of RNF168R to corresponding 1 μM UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and 1 μM UbcH5c-NCP in 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5. After incubating in ice for 20 min, 4 μL of the mixture was applied on a grid as above.

For the RNF168FL-di-NCP sample, a mixture of 337 μL of 14.4 μM MBP-RNF168FL and 63 μL of 4.77 μM di-NCPub in 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5, was first incubated in ice for 20 min and then mildly cross-linked by adding 8 μL of 5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and incubating in ice for 5 min. After quenching the reaction with 100 μL of 0.8 M glycine, pH 7.5, the mixture was immediately injected into a SEC Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5. Fractions containing RNF168FL-di-NCP were pooled and concentrated to ~1 μM. Grids were prepared as above using 4 μL of the sample for each grid.

Cryo-EM data processing

Cryo-EM data for RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP were acquired using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Titan Krios electron microscope operated at 300 kV with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector in super-resolution mode, nominal magnification of 22,500, pixel size of 0.51375 Å/pixel and total dose of 50 e−/Å2 over 50 frames. The images were recorded with a defocus in the −1 to −3.5 μm range.

Data were processed using cryoSPARC v2.14. 38 Movies were first patch motion-corrected and then contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were estimated with GCTF. 84 For RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP, a total of 4,867 super resolution movies were collected. Initial evaluation produced 4,644 micrographs, 470 of which were used to pick 796,242 particles with blob picker. 2D class averages were next calculated and used as templates for particle picking on the entire dataset. In total, 7,889,111 particles were picked and after subjecting these to two rounds of 2D classification, 2,640,819 particles were retained for 3D classification. Using 3D ab initio reconstruction, three initial class constructions were generated. The best class, which contained 1,241,185 particles and exhibited distinguishable nucleosome shape, was subjected for further 3D classification. Two rounds of 3D classification produced 184,451 particles which exhibited well-defined RNF168R-UbcH5c density atop the NCP. A final 3D classification led to retention of 58,264 particles, which were then used for CTF refinement, beam tilt correction, consensus refinement, non-uniform refinement, and local refinement. The final reconstructed map obtained has a resolution of 3.2 Å.

With the same instrumentation and parameters as above, 5,697 super resolution movies were recorded for NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c. Using cryoSPARC v4.1.1, 5,503 micrographs were retained after motion correction and CTF estimation. Using 200 of these micrographs, 38,837 particles were picked, generating 2D class averages which were then used as templates for automatic particle picking on the entire dataset. A total of 9,989,935 particles were picked. These were then extracted with Fourier cropping to one-fourth the extraction box size of 256 pixels. Two rounds of 2D classification were done reducing the number of particles to 696,485. These particles were re-extracted without Fourier cropping and subsequently used for ab initio reconstruction and 3D classifications. The resulting 151,300 particles displayed features of RNF168R-UbcH5c and were exported to RELION 3.0.735 for masked 3D classification (mask applied on RNF168R-UbcH5c). From the eight classes generated, one class (with 27,986 particles and with intact density for RNF168R-UbcH5c) was set aside while the rest were collectively subjected for further masked 3D classification. Eight classes were again generated with five exhibiting intact but weak density for RNF168R, and patchy density for UbcH5c. These five classes, with combined particle count of 84,664, were refined achieving a resolution of 3.8 Å for the final reconstructed map. For the class with 27,986 particles, a resolution of 3.9 Å for the final reconstructed map was achieved following similar refinement.

Cryo-EM data for RNF168R bound to UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and to UbcH5c-NCP were acquired using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Titan Krios electron microscope operated at 300 kV with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector in super-resolution mode and at nominal magnification of 130,000, pixel size of 0.664 Å/pixel, total dose of 50 e−/Å2 over 50 frames, and defocus range of −0.5 and −3.0 μm. Using the same electron microscope and parameters, data were also collected for the RNF168FL-di-NCP complex. The datasets were processed using cryoSPARC v4.1.138 and RELION 3.0.7.35

For RNF168R bound to UbcH5c~Ub-NCP, a total of 14,179 movies were recorded. After patch motion correction and CTF estimation, 14,113 micrographs were curated of which 537 were used to pick 371,332 particles with blob picker. The particles were subjected to two rounds of 2D classification, producing the templates used for particle picking on the entire dataset. In total, 16,063,830 particles were extracted and then Fourier cropped to one-fourth the extraction box size of 256 pixels. The particles were then subjected to a series of 2D classifications leading to a selection of 1,864,076 particles used for ab initio reconstruction. Two rounds of 3D classification produced clean 925,730 particles with well-defined RNF168R-UbcH5c density on the NCP. These particles were then re-extracted without Fourier cropping and exported to RELION 3.0.7 for masked 3D classification (mask applied on RNF168R-UbcH5c), resulting in eight classes from which six classes representing six different conformations for the RNF168R-UbcH5c moiety were obtained after further refinement without additional masking. The six classes are referred to as RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP and have final map resolutions from 3.2 to 3.3 Å. With ubiquitin masking applied to two of the eight classes, refinement produced another set of six classes with clear densities for ubiquitin close to the C-terminus of UbcH5c (referred to as RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP), and with resolutions ranging from 3.7 to 4 Å. Similar ubiquitin masking applied during refinement of one of the eight classes resulted in two classes. These two classes have clear ubiquitin density at the backside (close to S22) of UbcH5c (referred to as RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP) and have resolutions of 3.9 and 4.0 Å.

For RNF168R bound to UbcH5c-NCP, 11,501 movies were recorded. Following patch motion correction and CTF estimation, 11,333 micrographs were kept from which, 12,545,249 particles were extracted and then Fourier cropped to one-fourth the extraction box size of 256 pixels. From a series of 2D classifications, 3,217,741 of clean particles were retained for re-extraction without Fourier-cropping. The particles exhibited preference for a top-view orientation of the nucleosome. Nonetheless, with sufficient numbers of particles in various other orientations also present, ab initio reconstruction was done without any problem of orientational bias. After 3D classification, most of the particles with the dominant top-view orientation were removed. The 105,854 particles left have balanced orientations and generated a map bearing good densities for both nucleosome and RNG168R-UbcH5c. The particles were then imported to RELION 3.0.7 for masked 3D classification (mask applied on RNF168R-UbcH5c) following a similar procedure used for RNF168R bound to UbcH5c~Ub-NCP. Six classes were generated, two of which exhibited clear density for RNG168R-UbcH5c. Refinement of one of the classes, with final particle count of 22,664, led to a map with a resolution of 3.6 Å.

For the RNF168FL-di-NCPub sample, a total of 11,712 movies were recorded. After motion correction and CTF estimation, 10,993 micrographs were retained for template-based particle picking in cryoSPARC v4.1.1. The resulting 9,619,981 particles of single NCPs picked were extracted and then Fourier cropped to one-fourth the extraction box size of 256 pixels. After two rounds of 2D classification to remove junk particles, 1,068,286 particles were obtained. These particles were then re-extracted without Fourier cropping for subsequent ab initio reconstruction and 3D classification. A total of 315,649 particles displaying clear density for the LRM were then exported to RELION 3.0.7 for masked 3D classification (mask applied on ubiquitin). The results produced eight classes of RNF168FL-di-NCPub. Three of the classes showed intact and distinct conformations for ubiquitin, with one of the classes additionally exhibiting clear density for the MIU2 motif of RNF168. Further refinement of the three classes resulted in resolutions from 3.6 to 3.8 Å.

Model building

For building the RNF168R-UbcH5c-NCP model, we used previously reported crystal structures of RNF168R and UbcH5c (PDB identification codes indicated in Table S2) and a crystal structure of the NCP reconstituted with H3-H4 and H2A-H2BL (unpublished). The RNF168R, UbcH5c and NCP structures were each docked into the reconstructed density map using PHENIX. The protein structures were extended using COOT in regions where the electron density allowed. Each model was then subjected to manual adjustment in COOT and iterative real-space refinement in PHENIX. The reconstruction resolution was calculated using the gold-standard FSC criterion of 0.143. Model-map FSC was calculated using the criterion of 0.5.

Model buildings of NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c, RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP were done following similar above steps of docking structures (PDB identification codes indicated in the relevant tables) into density maps and refining the fit iteratively in PHENIX and COOT. For NCPub-RNF168R-UbcH5c, for lack of or weak density, ubiquitin was not modeled in both classes while UbcH5c was only modeled in class 2. For RNF168R-UbcH5c~Ub-NCP and RNF168R-UbcH5c-UbB-NCP, the ubiquitin structure was docked in the density using the “Fit in Map” function in Chimera. For RNF168FL-di-NCPub, only the LRM and MIU2 motifs of RNF168, ubiquitin and NCP were identifiable in the maps. Thus, an NCP structure (PDB 7LYA) and a structure of RNF168 (MIU2 domain) bound to ubiquitin generated by homology modeling using the structure of RNF169 (MIU2 domain) bound to ubiquitin (PDB 5VEY)33 were docked in the cryo-EM density. The LRM was also modeled de novo in this density.

Each refined structure was validated using the other half-map (mapfree) and the full map (mapfull).85 The FSC was determined between the model and each of the two half maps (FSCwork and FSCfree) and the full map (FSCfull). The computed FSC between the model and the second half-map (not used for refinement) (FSCfree) agrees well with that between the model and the first half-map (used for refinement) (FSCwork). The final structure was also assessed by Molprobity.86 Figures of the cryo-EM density maps and models were prepared using Chimera, COOT and PyMOL.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were carried out on a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe. NMR spectra were processed with NMRPipe/NMRDraw87 and analyzed using Sparky 3.115 (T.D. Goddard and D.G. Kneller, University of California). For backbone assignments, 15N,13C-labeled samples of RNF168R and UbcH5c in 50 mM NaPi, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP, pH 7.0, were prepared, and standard triple-resonance spectra were collected at 25 °C.

For chemical shift perturbation experiments, 0.1 to 0.3 mM of the following labeled samples were incrementally titrated with up to 2- to 5-fold molar excess of non-labeled samples. Typically, 5 to 10 spectra were collected at 25 °C or 30 °C for the titrations of 15N,2H-labeled H2AK13S-H2B (i.e., H2B (aa 13–123)-H2A K13S (aa 12–105)) with non-labeled RNF168R (WT, R57A and R57A/R63A/R67A), UbcH5c (S22R) or RNF168R-UbcH5c; 15N-labeled RNF168R (WT, R57A and R63A) with non-labeled H2AK13S-H2B (with and without H2A E61A mutation); 15N-labeled RNF168R with non-labeled UbcH5cS22R/C85Kub (in the absence or presence of H2AK13S-H2B); UbcH5cS22R/C85Kub (15N-labeled UbcH5c or ubiquitin) with non-labeled RNF168R (in the absence or presence of H2AK13S-H2B); and UbcH5cS22R/L119Kub (15N-labeled UbcH5c or 15N, 2H-labeled ubiquitin) with non-labeled RNF168R.

For methyl-TROSY titration experiments, 0.05 mM Val/Leu-[13CH3, 12CD3] and/or Ile-δ1-[13CH3] selectively labeled H2A-H2B was titrated with non-labeled RNF168R-UbcH5c up to 4-fold molar excess. Similarly, 0.05 mM of the NCP with Val/Leu-[13CH3, 12CD3] and/or Ile-δ1-[13CH3] selectively labeled H2A-H2BL and fully deuterated H3 and H4, was also titrated with up to equimolar amount of non-labeled RNF168R-UbcH5c. Titrations with selectively labeled H2A-H2B and NCP were performed at 30 °C and 40 °C, respectively.

The NMR spectroscopy-monitored ubiquitylation reactions were carried out at 22 °C using a mixture containing 0.12 mM 15N-labeled ubiquitin, 1–3 μM UBA1, 3 μM UbcH5cS22R, 1–10 μM RNF168R and 0.13 mM H2AK13S-H2B. A SOFAST-HMQC88 spectrum was first acquired. After addition of ATP at a final concentration of 3 mM, a series of 50–200 SOFAST-HMQC spectra were acquired. Subsequently, other reaction mixtures were prepared wherein a mutation in either RNF168R or H2A-H2B was incorporated. For all spectra, changes in signals of the last two residues of ubiquitin (Gly75 and Gly76) were analyzed. These signals have distinct shifts before and after isopeptide bond formation, making them suitable indicators for the amounts of unreacted and reacted ubiquitin. By tracking the ubiquitin consumption rate, i.e., plotting the concentration of unreacted ubiquitin versus time, we were able to monitor the progress of the different ubiquitylation reactions.

Mass spectrometry

A sample of UbcH5c-Ub was prepared by self-ubiquitylation of UbcH5c at a final concentration of 100 μM in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 3 μM UBA1, 120 μM ubiquitin and 3 mM ATP. Ubiquitylation was performed at 32 °C for 22 h and the UbcH5c-Ub product was purified by SEC using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Aliquots, each containing 60 pmol of UbcH5c-Ub, were digested with trypsin and chymotrypsin following reduction with TCEP and alkylation with chloroacetamide. After acidification, the digested mixtures were combined and analyzed by nanoLC-tandem mass spectrometry using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Exploris 480 mass spectrometer coupled to a Vanquish Neo chromatography system. Mass spectrometry data were acquired in data dependent mode with MS1 scans at 120,000 resolution and MS2 scans at 15,000 resolution (at 200 m/z). Data were then analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer 3.0 software programmed to search a database that includes the amino acid sequence of UbcH5c, with carbamidomethylation of cysteines set as a fixed modification, and oxidation of methionine and ubiquitylation of lysines set as variable modifications. Matched spectra were filtered by fixed value peptide spectral match (PSM) validation with delta Cn of 0.05 and manually inspected afterwards.

Fluorescence polarization