Abstract

Gene expression is a complex process requiring many control mechanisms to achieve a desired phenotype. DNA accessibility within chromatin is well established as an important determinant of gene expression. In contrast, while mRNA also associates with a complement of proteins, the exact nature of messenger ribonucleoprotein(mRNP) packaging and its functional relevance is not as clear. Recent reports indicate that exon junction complex (EJC)-mediated mRNP packaging renders exon junction-proximal regions inaccessible for m6A methylation, and that EJCs reside within the inaccessible interior of globular TREX-associated nuclear mRNPs. We propose that “mRNA accessibility” within mRNPs is an important determinant of gene expression that may modulate the specificity of a broad array of regulatory processes including but not limited to m6A methylation.

Keywords: m6A RNA methylation, mRNA accessibility, exon junction complex (EJC), TREX, messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP), RNA binding proteins

mRNA accessibility within messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP)s Nucleic acids encode genetic information that specify the complex system of chemical processes that are required to sustain living organisms. For gene expression to occur, DNA and RNA must interact with a variety of proteins that enable transcription, mRNA processing and translation. Essential to this process are the architectural proteins bind to nucleic acids, which regulate the availability of specific regions of nucleic acids to the rest of the gene expression machinery. DNA accessibility (see Glossary) within chromatin, also called chromatin accessibility, is well established as a major determinant of eukaryotic gene expression [1]. Nucleosomes, which comprise an octamer of histone proteins encircled by ~ 147 bp of DNA, are the core structural elements of chromatin [2]. Nucleosomes sterically hinder access to packaged DNA, broadly suppressing accessibility of bound DNA regions to regulatory factors, such as transcription factors (TF). Chromatin that is loosely packaged, i.e. “open” chromatin, is permissive for TF binding [2]. Conversely, chromatin that is tightly packaged, i.e. “closed” chromatin, is not permissive for TF binding [3]. Displacement of nucleosomes by chromatin remodelers creates regions of open chromatin that enable physical access to active DNA elements by regulatory factors [4]. While there are certainly exceptions to this model, as evidenced by TFs that preferentially bind to heterochromatic DNA and pioneer TFs that open chromatin, the majority of TFs bind to and function on accessible chromatin [2].

In contrast to DNA accessibility, an analogous concept of “mRNA accessibility” within messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP)s as an important determinant of gene expression has not been well established. Though mRNA is often simplistically depicted in schematics as a ‘free’ strand of nucleic acid, mRNA is heavily associated with protein, forming RNA-protein complexes termed mRNPs. Indeed, mRNPs have been estimated to exhibit an average RNA:protein weight ratio of ~ 1:3, calculated based on the equilibrium buoyant densities of mRNPs in a CsCl gradient [5,6]. Pre-mRNA and mRNA are bound by a complement of associated RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that varies between genes and changes over the lifetime of the RNA [7], and it is estimated that over one thousand human proteins can bind to mRNA in some capacity [8-12]. Some of these RBPs, such as heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) and exon junction complexes (EJCs), have been reported to play architectural roles and shape the higher order organization of mRNPs by packaging mRNA into more compact particles [7,13]. An additional layer of complexity is the secondary and tertiary structures driven by RNA base-pairing, which may also drive mRNA compaction [14,15]. Altogether, in comparison to DNA, the exact three-dimensional organization of mRNPs and its functional relevance for gene expression is not as well understood.

While previous reports have shed light on the role of the EJC as an architectural component of mRNPs, the functional importance of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging has until recently remained unclear. Here, we propose that “mRNA accessibility” within mRNPs is an important determinant of gene expression, focusing on recent evidence suggesting an important role of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging in the regulation of m6A specificity. In this Opinion, we first review the role of the exon junction complex in mRNP packaging of pre-translational mRNPs. We then discuss the recently identified role for the EJC as a central regulator of m6A specificity, functioning to suppress m6A installation [16-18]. Next, we outline evidence supporting that the mechanism by which the EJC controls m6A specificity is through its role in mRNP packaging; EJC-mediated mRNP packaging renders exon junction-proximal regions inaccessible, but exon junction-distal regions accessible, to the m6A methyltransferase complex [16]. These results appear to dovetail with recent structural work that has clarified the structure of nuclear mRNPs associated with EJCs and transcription and export (TREX) complexes [19]. Finally, we discuss evidence suggesting that EJC-mediated mRNP packaging may modulate the specificity of a broad array of regulatory processes including but not limited to m6A methylation.

EJCs and mRNP packaging

EJCs are central players in the packaging and compaction of mRNPs. EJCs are composed of three core proteins, EIF4A3, RBM8A, and MAGOH, and a complement of peripheral components that vary according to the stage of mRNA biogenesis and cellular context. EJCs are deposited ~24 nt upstream of exon-exon junctions during pre-mRNA splicing and play a diverse array of roles in gene expression regulation [20-22]. EJCs promote mRNA export, direct mRNA localization of certain mRNAs, enhance translation, and activate nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). In addition to these roles, EJCs have also been reported to play an architectural role in the organization of pre-translational mRNPs [7,20,21].

EJCs initially form high molecular weight mRNP complexes in which EJCs multimerize and interact with a wide variety of other proteins, including serine/arginine-rich (SR) and SR-like proteins such as the peripheral EJC component RNPS1 [23,24]. EJCs, in the context of these high molecular weight mRNPs, have been proposed to package proximal RNA based on their ability to protect long RNA footprints from in vitro nuclease digestion [23]. Using a proximity ligation approach, another study reported that mRNAs associated with EJCs are compacted into linear rodlike structures [25]. The organization of this packaging appears to be dynamic and evolves over the lifetime of the mRNA. As the mRNP transits from nucleus to cytoplasm for translation, EJC composition shifts from this higher order mRNP complex to a lower molecular weight SR protein-devoid monomeric form that lacks RNPS1 and contains the EJC subunit CASC3 [24]. While these previous reports shed light on the role of the EJC as an architectural component of mRNPs, the functional importance of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging has until recently remained unclear.

mRNP packaging is critical for regulation of m6A specificity

Recent work suggests that the mRNP packaging function of the EJC is crucial to enforce m6A methylation specificity and prevent widespread m6A-mediated decay [16]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent mRNA modification and regulates gene expression by influencing numerous aspects of mRNA metabolism, including pre-mRNA processing, nuclear export, mRNA stability, and translation [26]. The METTL3-METTL14 methyltransferase complex installs m6A methylation on mRNA in a common DRACH (where D = A, G, or U; R = A or G; and H = A, C, or U) sequence motif, but only ~5% of DRACH sequences are selected for methylation [26]. Additionally, m6A exhibits a strong bias in its transcriptomic distribution, being strongly enriched in long internal exons and near stop codons [27,28]. Despite the central importance of specific m6A deposition in m6A-mediated gene regulation, the mechanistic basis for m6A specificity until recently was poorly understood.

In a recent study, we found that regulation of m6A methylation specificity is a critical function of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging [16]. In our search for factors that controlled m6A specificity, we unexpectedly found evidence for widespread suppression of aberrant m6A sites across the transcriptome using a massively parallel reporter assay that we termed MPm6A. Interestingly, using minigene reporter assays, we found that splicing suppressed m6A methylation at m6A sites in an exon length-dependent manner. Splicing of average length internal exons suppressed m6A, but this suppressive effect was lost in longer internal exons. Further investigation revealed that this length-dependent suppressive effect was mediated by the EJCs deposited by spliceosomes near exon boundaries. We found that knockdown of either EIF4A3 or RBM8A, two core EJC subunits, resulted in pervasive aberrant m6A methylation near exon junctions transcriptome-wide. EJCs locally suppress m6A deposition at proximal RNA, which prevents m6A deposition in average length exons. EJC suppression of m6A accounts for the hallmark enrichment of m6A in long internal exons, as well as the sharp increase of m6A upstream stop codons (which generally correspond to the region after the last exon-exon junction).

Indeed, two contemporaneous studies also reported that depletion of EJC components resulted in widespread aberrant m6A methylation [17,18]. Uzonyi et al. also used a massively parallel reporter assay and minigene reporter experiments to conclude that splicing was important to prevent m6A methylation near exon junctions. They showed that a simple predictive model in which all DRACH motifs >100 nt away from exon junctions are methylated performed well in reproducing the distribution of m6A methylation across the transcriptome. They propose that m6A-mediated mRNA decay contributes substationally to previously reported correlations between mRNA exon density and mRNA degradation rates [29]. Finally, they also found that depletion of RBM8A results in increased m6A in exon junction-proximal regions. Yang et al. also concluded from minigene reporter experiments that splicing suppresses m6A methylation. They found that depletion of EIF4A3 results in increased METTL3 binding and m6A methylation near exon junctions transcriptome-wide, and that tethering of eIF4A3 to a reporter construct decreases local METTL3 occupancy. Based on these data, they proposed that the EJC blocks local METTL3 binding and thus m6A methylation. Interestingly, both we and others find evidence for the existence of m6A suppressors beyond the EJC (Box 1). Altogether, these studies support the importance of the EJC in governing m6A specificity.

Box 1. Beyond the EJC: more m6A suppressors?

Interestingly, there may be more m6A suppressors beyond the EJC. We identified thousands of suppressed m6A sites in 3’UTRs, downstream of stop codons, that are not suppressed by the EJC [43]. While the mechanism that suppresses these sites is unclear, we believe the mechanism is likely related to alternative polyadenylation. It has previously been reported transcript isoforms generated from proximal 3’UTR polyadenylation sites tend to be methylated, while isoforms generated from distal 3’UTR polyadenylation sites tend to be unmethylated [44]. Many of the identified suppressed 3’UTR sites we identified reside in 3’UTR regions only present on the transcript isoforms generated from distal polyadenylation sites [16]. Therefore, additional m6A suppressing pathways likely exist that prevent m6A deposition on transcript isoforms generated from distal polyadenylation sites, contributing to the lack of m6A downstream of stop codons and the start of terminal exons. Interestingly, Uzonyi et al. also noted a connection between m6A and polyadenylation, but proposed a different model that the decline past stop codons could be explained by incorrect annotation of 3’ UTR ends, and that computational modelling of suppression of m6A near polyadenylation sites using reannotation of gene ends reproduced the decline of m6A within terminal exons [18]. The exact identity of these suppressive mechanisms, and whether they also act via control of mRNA accessibility and mRNP packaging or by other distinct mechanisms remains to be established. Note that another study also used computational modeling to suggest that exon-intron boundaries suppress m6A methylation, and proposed that additional factors beyond the EJC contribute to the effect of exon structure on m6A suppression [45].

Regarding the specific mechanism by which the EJC suppresses m6A methylation, we found evidence suggesting that the EJC suppresses m6A deposition by sterically hindering accessibility to the m6A methyltransferase complex via its packaging of proximal RNA. While the core EJC itself only protects 8-10 nucleotides of RNA from nuclease accessibility in the context of in vitro splicing reactions [22], the ability of EJCs to protect longer stretches of proximal RNA from nuclease digestion within cellular mRNA is thought to be due to their ability to multimerize and associate with a large complement of other proteins within the context of compacted nuclear mRNPs, sterically hindering access to the bound RNA [23]. This suggests that other proteins associated with the core EJC within compacted mRNPs may be important for blocking access of exon junction-proximal RNA by the methyltransferase complex. Consistent with this notion, we found that the EJC peripheral factor RNPS1, which associates with EJCs in megadalton-scale, higher-order nuclear mRNPs [24], contributes to the ability of the EJC to suppress proximal m6A methylation. We found that similarly to depletion of EIF4A3 and RBM8A, depletion of RNPS1 led to hypermethylation of transcript regions in average-length internal exons within coding sequences. While there were less hypermethylated regions when depleting RNPS1 than the core factors, approximately half of these regions were shared with the core EJC factors [16]. Overall, the ability of the EJC to prevent accessibility of long stretches of nearby RNA appears to rely on other associated factors within compacted nuclear mRNPs, such as RNPS1.

Next, we probed whether the ability of EJC to package long stretches of proximal RNA is sufficient to prevent m6A methylation. Consistent with previous work [23], we found that EJCs protected tens to hundreds of nucleotides of proximal RNA from RNase accessibility in vitro. Notably, the extended range of protection EJCs confer to proximal RNA from nuclease digestion matches nicely with the the extended range of protection EJCs confer for m6A methylation. We found that these inaccessible long RNA footprints are strongly depleted of m6A, indicating that these inaccessible RNA regions are largely protected from cellular m6A deposition [16]. Further, these long RNA footprints, when associated with EJCs and other bound proteins, were resistant to in vitro methylation by recombinant METTL3-METTL14. In contrast, deproteinized RNA footprints were robustly methylated by recombinant METTL3-METTL14 in vitro, suggesting that packaging of proximal RNA by the EJC and associated proteins protects these footprints from access by the methyltransferase complex [16]. These experiments collectively suggest that the ability of the EJC to collaborate with associated factors and package long stretches of nearby RNA underlies its ability to suppress m6A methylation of exon junction-proximal RNA. In this way, exon architecture determines mRNP accessibility to the m6A methyltransferase complex, which consequently regulates m6A methylation. Loss of this suppression resulted in aberrant methylation of transcripts and subsequent decay by the m6A reader YTHDF2. Interestingly, this transcript stability regulation through the exon architecture appears to be co-evolved with YTHDF2 in animals [16]. Altogether, these results revealed that one function of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging is to sterically hinder access of the m6A methyltransferase complex, thus ensuring specificity of m6A mRNA methylation and preventing aberrant m6A-mediated decay.

Structural insights into TREX-EJC interactions within packaged mRNP globules

Interestingly, the findings that EJCs suppress m6A deposition via their mRNP packaging function dovetail with recent structural work suggesting that the TREX complex and EJCs collaborate to package nuclear mRNPs into a compact globular structure, with EJCs sequestered within the interior of the globule. The TREX complex, which mediates the export of nuclear mRNPs, has also been implicated in the packaging of nuclear mRNPs [30-32]. A recent study used cryo-EM to visualize the structure of endogenous human mRNPs bound to the export factor TREX in native conditions and found that these mRNPs form compact, non-uniform globules [19]. They report that these TREX-associated mRNPs have a median diameter of ~450 Å, representing an approximately ~50-fold compaction of the mRNA. Interestingly, their results support a TREX-mRNP architecture in which TREX complexes reside at the surface of mRNP globules while the EJCs reside within the less accessible interior. They further probed the ability of an anti-GFP nanobody to bind to GFP-tagged THOC5 TREX subunits or GFP-tagged EIF4A3 EJC subunits within the context of the mRNPs [32]. Using nuclear extracts, they found that while TREX was equally accessible in the mRNP or free protein state, EIF4A3 was much less accessible to the nanobody within the context of the mRNP. Consistent with a lower degree of compaction in cytoplasmic mRNPs, they found that using cytoplasmic extracts, EIF4A3 was equally accessible in the context of the mRNP and free protein. Using recombinant TREX, EJC and RNA, they found that TREX binds mRNA-bound EJCs through multivalent interactions with the mRNA binding protein ALYREF [33], with one molecule of ALYREF bridging three EJC-RNA complexes. The authors propose that ALYREF brings EJC complexes into close proximity, with the intervening mRNA between exon junctions looped out [32].

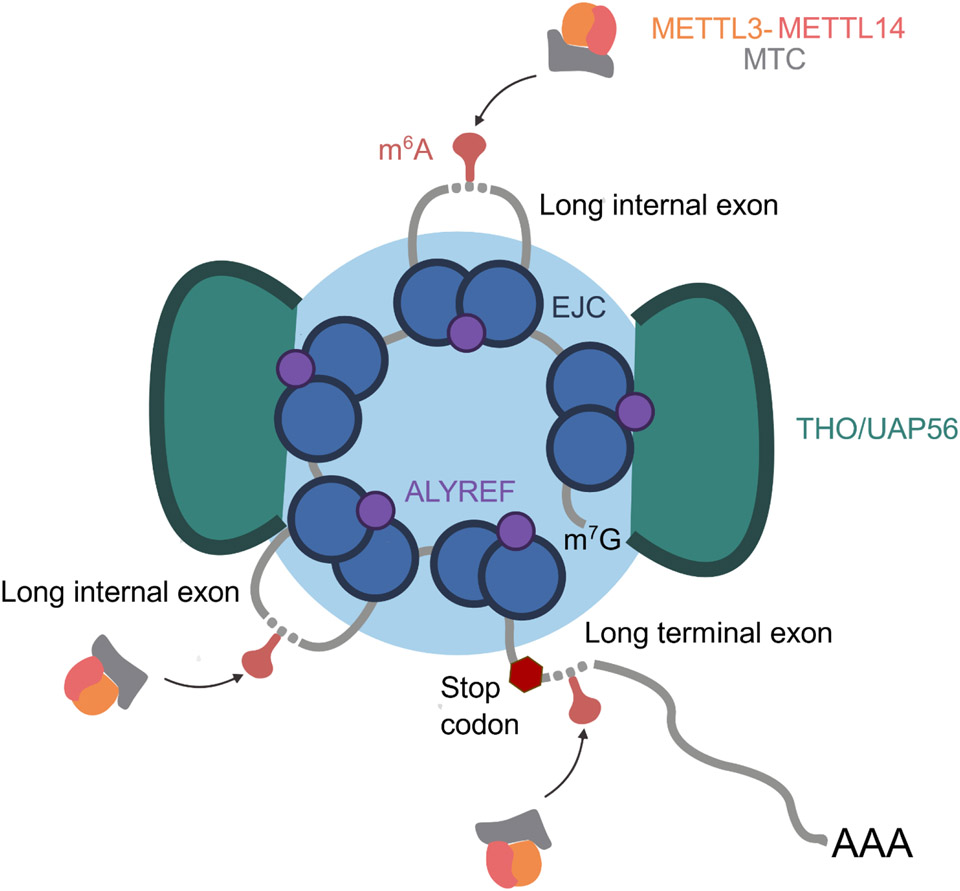

Altogether, we believe these structural insights dovetail with recent work on EJC-mediated m6A suppression [16-18]. The structure of TREX-associated nuclear mRNP globules offers a potential explanation for how exactly EJC-mediated mRNP packaging suppresses m6A deposition at proximal RNA (Fig. 1). mRNA regions most proximal to exon junctions are packaged deep inside the mRNP globule and are inaccessible for methylation. Conversely, longer exons with long stretches of intervening RNA between EJC binding sites are looped out and more accessible for methylation. Therefore, mRNP structure and the physical accessibility of specific regions are intimately linked to m6A methylation and gene expression.

Key Figure - Fig. 1.

mRNA accessibility within nuclear mRNP globules as an important determinant of gene expression. Schematic model of how the structure of TREX-associated nuclear mRNPs may impact accessibility of mRNA to m6A methylation. Within nuclear TREX-associated mRNPs, EJCs are sequestered along with proximal RNA within the interior of the globule. Conversely, RNA in long exons escapes sequestration within the interior of the globule and is freely accessible. mRNP accessibility controls availability of mRNA regions for m6A methylation and is thus an important determinant of gene expression. We propose that mRNP accessibility may also broadly control access of RNA to splicing machinery, nucleases and other RNA regulatory factors. We note that mRNAs within these mRNPs are also bound by many additional RNA-binding proteins that are not depicted in the figure for clarity.

Beyond m6A methylation: a broader role for EJC regulation of mRNP accessibility

The nature of the mechanism by which the EJC suppresses m6A suggests that EJCs may suppress a broader range of processes beyond m6A methylation, as many different RNA regulators could theoretically be impacted by steric hindrance. Indeed, it had previously been reported in earlier publications that EJC locally suppresses splicing in a distance-dependent manner reminiscent of what we observe for m6A methylation [34,35]. We noticed that EJC-suppressed methylation sites colocalize with EJC-suppressed splice sites, suggesting that EJCs and exon architecture broadly determine accessibility of local mRNA to regulatory machineries through packaging of exon junction-proximal mRNA [16]. Notably, RNPS1 has been implicated in both processes [16,34,35]. We also observed that a number of RBPs beyond the m6A methyltransferase complex also exhibit preferential binding at long internal exons, suggesting that the accessibility of these RBPs to mRNA may also be modulated by EJC packaging [34].

EJCs exhibit several distinctive characteristics that endow them with a unique capacity to control gene expression via regulating mRNP accessibility. Unlike many other RBPs, EJCs bind RNA in a largely sequence-independent manner, with their binding positions specified instead by the splice site usage of a particular mRNA [20,36]. Additionally, most human genes are multiexon and contain short internal exons and long terminal exons. This stereotypical gene structure means that most mRNAs across the transcriptome are bound by multiple EJCs at closely spaced intervals within CDS regions [36]. Further, EJCs are stably bound to mRNAs after their initial deposition, as the EIF4A3 subunit is a helicase that tightly clamps onto RNA in an ATP-dependent manner. This may contribute to the ability of the EJC to package mRNA and prevent local accessibility to other factors, as the EJCs, once deposited onto mRNAs, do not dissociate from the RNA until the pioneer round of translation [37-39]. Altogether, the multitude of EJCs that stably bind spliced mRNAs are well positioned to package large swaths of mRNA into mRNPs.

Notably, there are some interesting parallels between EJC-mediated mRNP packaging to DNA and chromatin. EJCs, like histone octamers, extensively bind their respective nucleic acids at closely-spaced intervals without strict sequence requirements. The average distance between nucleosome midpoints in humans is ~185 bp, and the average exon length (and thus the average spacing between EJC binding sites) is around 140 nt [40,41]. These properties appear to collectively enable the EJC to robustly protect large swaths of the transcriptome from methylation and perhaps other processes such as splicing or binding by large RBPs. While there are certainly many notable differences between nucleosomes and EJCs, it appears that they are both major players in the regulation of the accessibility of their respective nucleic acids. Notably, some of the earliest work on RNA packaging was on the packaging of pre-mRNA by hnRNP proteins into hnRNP particles, which were termed ribonucleosomes due to their structural resemblance to nucleosomes within DNA (Box 2). Altogether, architectural proteins on pre-mRNA/RNA, such as the EJC and hnRNPs, may broadly control accessibility of RNA to abroad array of gene expression machineries in a manner reminiscent to the packaging of DNA into nucleosomes within chromatin.

Box 2. hnRNPs and RNA nucleosomes.

Early reports on pre-mRNA/mRNA packaging focused on the packaging of nascent heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA), more commonly referred to as pre-mRNA today, by heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP) into hnRNP particles [13]. These studies reported parallels between the packaging of hnRNA into hnRNP particles and the packaging of DNA into nucleosomes. Visualization of newt oocyte and Drosophila embryo hnRNA by electron microscopy revealed a “beads-on-a-string” repeating subunit structure of 200-300 angstrom spherical protein-associated particles connected by ribonuclease-sensitive regions [46,47]. These oligomeric arrays of particles converted to 20 nm monomers in the presence of nuclease activity and were termed “hnRNP particles”. hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2, hnRNPB1, hnRNPB2, hnRNPC1, hnRNPC2 were identified as the packaging proteins within these particles [48]. These proteins assemble in a defined molar ratio and package pre-mRNA into repeating arrays [49,50]. hnRNPC1/C2 (hnRNPC) act as protein rulers that define the length of RNA to be packaged and form tetrameric complexes that bind ~150-230 nt of RNA with high cooperativity [51]. Due to the notable parallels between the packaging of DNA by histones and the packaging of pre-mRNA by hnRNPs, these hnRNP particles were termed “RNA nucleosomes”, or “ribonucleosomes” [50,52,53].

It is notable that few studies appear to have specifically examined the extent to which the pre-mRNA packaging function of hnRNPs, as opposed to non-packaging functions, contributes to their importance in gene expression regulation. One study examining the role of hnRNP packaging in gene expression mapped hnRNPC RNA binding sites and found that the RNA recognition motif domains of hnRNPC bind uridine-rich tracts; consistent with the role of hnRNPC in packaging RNA in hnRNP particles, a subset of these binding sites are spaced at regular intervals of ~ 165 nt and 300 nt [18]. This study proposed that hnRNP packaging plays an important role in alternative splicing regulation. A subset of alternative exons appear to be silenced by incorporation of the exonic sequence into the hnRNP particles, whereas the usage of a subset of alternative exons are enhanced by incorporation of the preceding intronic sequence into hnRNP particles [18]. Overall, while there is some evidence for functional roles of hnRNP particles in gene expression, more detailed investigation is needed to fully elucidate their significance.

Dynamics in mRNP accessibility over the lifetime of an mRNA

The breadth of processes that are suppressed by the EJC may be dependent on the temporal window in which mRNA resides in this tightly packaged state. EJC mRNP composition is thought to shift from an initially high molecular weight, highly packaged form, to a lower molecular weight, loosely packaged form as the mRNA proceeds from transcription within the nucleus to translation in the cytoplasm [24]. Pre-mRNA splicing and m6A methylation are nuclear processes that generally occur quickly after transcription, likely coinciding with the time when EJCs initially form highly packaged mRNP structures. Further, since EJCs are displaced from mRNAs upon the pioneer round of translation, regulatory machineries that interact with mRNAs following translation are unlikely to be impacted by EJC-mediated mRNA packaging. Indeed, single molecule resolution FISH experiments that suggest that while nuclear mRNPs are highly compacted, ribosomes decompact mRNPs during translation [42]. Given that EJC composition may shift over time, events in mRNA metabolism that occur at later stages in the mRNA lifetime may evade EJC-suppression. Thus, dynamic changes in mRNP accessibility over the lifetime of an mRNP may have important implications for their expression and metabolism.

Dynamic mRNP structural remodeling may account for the contrasting shapes of EJC-associated mRNPs obtained through different methods. The globular structure reported for TREX-associated mRNPs differs from the linear rod-like structure previously reported for EJCs using a proximity ligation approach [25]. This could potentially be due to different accessibilities of the EJC in each of these structures; Metkar et al. obtained mRNPs by immunoprecipitating EJC components, thus enriching for particles with EJCs accessible to antibody binding. In contrast, the EJCs within the TREX-mRNPs are sequestered within the interior of the globule and inaccessible to nanobody binding. Dynamic changes in mRNP structure could affect mRNA accessibility. An interesting future line of research will be to understand the dynamics and mechanisms underlying mRNP remodeling, and whether there may be analogous machinery on RNA to the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes that enable dynamic regulation of chromatin accessibility [4]. While recent advances have shed light on the mRNP architecture of nuclear/ pre-translational mRNPs and its relevance for gene expression, further work will be needed to define dynamic changes in mRNP structure over time, the structure of cytoplasmic and post-translational mRNPs, and factors involved in regulating structural changes of mRNPs.

Concluding remarks

Altogether, these recent studies enable an emerging appreciation for the importance of higher order mRNP architecture for the regulation of mRNP accessibility. These findings support our hypothesis that mRNA accessibility within mRNPs could represent an important determinant of gene expression by controlling the local accessibility of mRNA to regulatory machineries. Future work should explore the extent to which mRNA accessibility within mRNPs represents an important general determinant of gene expression.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the full complement of RNA regulatory processes impacted by mRNA accessibility?

Beyond the EJC, are there other proteins required for the regulation of mRNA accessibility?

Do mRNAs with long internal exons have different EJC-ALYREF-TREX multivalent interactions that alter mRNP structure?

How do secondary and tertiary RNA structures established by RNA base pairing interact with the higher order organization driven by TREX-EJC binding?

How might remodeling of EJC composition throughout the lifetimes of mRNPs change accessibility of mRNA to regulatory factors?

Highlights.

mRNA accessibility within mRNPs, in contrast to DNA accessibility within chromatin, has not yet been well established as an important determinant of gene expression.

Recent work has revealed the importance of the EJC as an architectural protein complex that controls mRNP packaging.

An important function of EJC-mediated mRNP packaging is to regulate m6A specificity.

Structures of nuclear mRNP globules reveal an architecture in which EJCs reside within the inaccessible interior of globules.

mRNA exon architecture may be a determinant of mRNA accessibility due to EJC-mediated mRNP packaging

Acknowledgements

We thank Steve Buratowski for discussion of terminology. Our research has been supported by National Institute of Health T32 HD007009 (P.C.H) and National Institute of Health HG008935 (C.H.). C.H. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Glossary

- DNA accessibility

the degree to which regulatory factors can access, i.e. physically contact, chromatinized DNA. Also called chromatin accessibility

- Exon Junction Complex (EJC)

Consists of the core proteins EIF4A3, RBM8A, MAGOH that are deposited 20-24 nucleotides upstream exon junctions during splicing

- messenger ribonucleoproteins (mRNPs)

Complex of mRNA and associated proteins. m6A- Methylation of adenosine at the N6 position. The most prevalent mRNA modification, regulates pre-mRNA processing, mRNA export, localization, decay and translation

- mRNA accessibility

the degree to which regulatory factors can access, i.e. physically contact, mRNA within mRNPs

- Pioneer transcription factors

Transcription factors that bind to closed chromatin and mediate its conversion to open chromatin

- Transcription and export complex (TREX)

Consists of THO–UAP56/DDX39B–ALYREF, mediates nuclear export of mRNPs

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

P.C.H declares no competing interests. C.H. is a scientific founder, a member of the scientific advisory board and equity holder of Aferna Green, Inc. and AccuraDX Inc., and a scientific cofounder and equity holder of Accent Therapeutics, Inc.

References

- [1].Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-Five Years of the Nucleosome, Fundamental Particle of the Eukaryote Chromosome. Cell 1999;98:285–94. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thurman RE, Rynes E, Humbert R, Vierstra J, Maurano MT, Haugen E, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature 2012;489:75–82. 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Soufi A, Donahue G, Zaret KS. Facilitators and Impediments of the Pluripotency Reprogramming Factors’ Initial Engagement with the Genome. Cell 2012;151:994–1004. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Clapier CR, Iwasa J, Cairns BR, Peterson CL. Mechanisms of action and regulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:407–22. 10.1038/nrm.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Perry RP, Kelley DE. Buoyant densities of cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein particles of mammalian cells: Distinctive character of ribosome subunits and the rapidly labeled components. Journal of Molecular Biology 1966;16:255–68. 10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Spirin AS. Messenger ribonucleoproteins (informosomes) and RNA-binding proteins. Mol Biol Rep 1979;5:53–7. 10.1007/BF00777488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Singh G, Pratt G, Yeo GW, Moore MJ. The Clothes Make the mRNA: Past and Present Trends in mRNP Fashion. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2015;84:325–54. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-080111-092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhäusser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, et al. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 2012;46:674–90. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bao X, Guo X, Yin M, Tariq M, Lai Y, Kanwal S, et al. Capturing the interactome of newly transcribed RNA. Nat Methods 2018;15:213–20. 10.1038/nmeth.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Queiroz RML, Smith T, Villanueva E, Marti-Solano M, Monti M, Pizzinga M, et al. Comprehensive identification of RNA–protein interactions in any organism using orthogonal organic phase separation (OOPS). Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:169–78. 10.1038/s41587-018-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Trendel J, Schwarzl T, Horos R, Prakash A, Bateman A, Hentze MW, et al. The Human RNA-Binding Proteome and Its Dynamics during Translational Arrest. Cell 2019;176:391–403.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Urdaneta EC, Vieira-Vieira CH, Hick T, Wessels H-H, Figini D, Moschall R, et al. Purification of cross-linked RNA-protein complexes by phenol-toluol extraction. Nat Commun 2019;10:990. 10.1038/s41467-019-08942-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dreyfuss G, Swanson MS, Pinol-Roma S. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles and the pathway of mRNA formation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1988;13:86–91. 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Khong A, Parker R. The landscape of eukaryotic mRNPs. RNA 2020;26:229–39. 10.1261/rna.073601.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zhang QC, Crisalli P, Lee B, Jung J-W, et al. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature 2015;519:486–90. 10.1038/nature14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].He PC, Wei J, Dou X, Harada BT, Zhang Z, Ge R, et al. Exon architecture controls mRNA m6A suppression and gene expression. Science 2023;379:677–82. 10.1126/science.abj9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang X, Triboulet R, Liu Q, Sendinc E, Gregory RI. Exon junction complex shapes the m6A epitranscriptome. Nat Commun 2022; 13:7904. 10.1038/s41467-022-35643-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Uzonyi A, Dierks D, Nir R, Kwon OS, Toth U, Barbosa I, et al. Exclusion of m6A from splice-site proximal regions by the exon junction complex dictates m6A topologies and mRNA stability. Molecular Cell 2023;83:237–251.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pacheco-Fiallos B, Vorländer MK, Riabov-Bassat D, Fin L, O’Reilly FJ, Ayala FI, et al. mRNA recognition and packaging by the human transcription-export complex. Nature 2023;616:828. 10.1038/s41586-023-05904-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Boehm V, Gehring NH. Exon Junction Complexes: Supervising the Gene Expression Assembly Line. Trends Genet 2016;32:724–35. 10.1016/j.tig.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hir HL, Saulière J, Wang Z. The exon junction complex as a node of post-transcriptional networks. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2016;17:41–54. 10.1038/nrm.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Le Hir H, Izaurralde E, Maquat LE, Moore MJ. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20–24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon–exon junctions. The EMBO Journal 2000;19:6860–9. 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Singh G, Kucukural A, Cenik C, Leszyk JD, Shaffer SA, Weng Z, et al. The Cellular EJC Interactome Reveals Higher Order mRNP Structure and an EJC-SR Protein Nexus. Cell 2012;151:750–64. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mabin JW, Woodward LA, Patton RD, Yi Z, Jia M, Wysocki VH, et al. The Exon Junction Complex Undergoes a Compositional Switch that Alters mRNP Structure and Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay Activity. Cell Rep 2018;25:2431–2446.e7. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Metkar M, Ozadam H, Lajoie BR, Imakaev M, Mirny LA, Dekker J, et al. Higher-Order Organization Principles of Pre-translational mRNPs. Mol Cell 2018;72:715–726.e3. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].He PC, He C. m6A RNA methylation: from mechanisms to therapeutic potential. The EMBO Journal 2021;n/a:el05977. 10.15252/embj.2020105977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012;485:201–6. 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ke S, Alemu EA, Mertens C, Gantman EC, Fak JJ, Mele A, et al. A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3′ UTR regulation. Genes Dev 2015;29:2037–53. 10.1101/gad.269415.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Spies N, Burge CB, Bartel DP. 3′ UTR-isoform choice has limited influence on the stability and translational efficiency of most mRNAs in mouse fibroblasts. Genome Res 2013;23:2078–90. 10.1101/gr.156919.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Strässer K, Masuda S, Mason P, Pfannstiel J, Oppizzi M, Rodriguez-Navarro S, et al. TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 2002;417:304–8. 10.1038/nature746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Müller-McNicoll M, Neugebauer KM. How cells get the message: dynamic assembly and function of mRNA-protein complexes. Nat Rev Genet 2013;14:275–87. 10.1038/nrg3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xie Y, Gao S, Zhang K, Bhat P, Clarke BP, Batten K, et al. Structural basis for high-order complex of SARNP and DDX39B to facilitate mRNP assembly. Cell Rep 2023;42:112988. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shi M, Zhang H, Wu X, He Z, Wang L, Yin S, et al. ALYREF mainly binds to the 5’ and the 3’ regions of the mRNA in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:9640–53. 10.1093/nar/gkx597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Boehm V, Britto-Borges T, Steckelberg A-L, Singh KK, Gerbracht JV, Gueney E, et al. Exon Junction Complexes Suppress Spurious Splice Sites to Safeguard Transcriptome Integrity. Molecular Cell 2018;72:482–495.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Blazquez L, Emmett W, Faraway R, Pineda JMB, Bajew S, Gohr A, et al. Exon Junction Complex Shapes the Transcriptome by Repressing Recursive Splicing. Mol Cell 2018;72:496–509.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Saulière J, Murigneux V, Wang Z, Marquenet E, Barbosa I, Le Tonquèze O, et al. CLIP-seq of eIF4AIII reveals transcriptome-wide mapping of the human exon junction complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012;19:1124–31. 10.1038/nsmb.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dostie J, Dreyfuss G. Translation is required to remove Y14 from mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Curr Biol 2002;12:1060–7. 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lejeune F, Ishigaki Y, Li X, Maquat LE. The exon junction complex is detected on CBP80-bound but not eIF4E-bound mRNA in mammalian cells: dynamics of mRNP remodeling. EMBO J 2002;21:3536–45. 10.1093/emboj/cdf345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gehring NH, Lamprinaki S, Kulozik AE, Hentze MW. Disassembly of exon junction complexes by PYM. Cell 2009;137:536–48. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schwartz S, Meshorer E, Ast G. Chromatin organization marks exon-intron structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009;16:990–5. 10.1038/nsmb.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tilgner H, Nikolaou C, Althammer S, Sammeth M, Beato M, Valcárcel J, et al. Nucleosome positioning as a determinant of exon recognition. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2009;16:996–1001. 10.1038/nsmb.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Adivarahan S, Livingston N, Nicholson B, Rahman S, Wu B, Rissland OS, et al. Spatial Organization of Single mRNPs at Different Stages of the Gene Expression Pathway. Molecular Cell 2018;72:727–738.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].He PC, Wei J, Dou X, Harada BT, Zhang Z, Ge R, et al. Exon architecture controls mRNA m6A suppression and gene expression. Science 2023;379:677–82. 10.1126/science.abj9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Molinie B, Wang J, Lim KS, Hillebrand R, Lu Z, Van Wittenberghe N, et al. m 6 A-LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m 6 A epitranscriptome. Nature Methods 2016;13:692–8. 10.1038/nmeth.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Luo Z, Ma Q, Sun S, Li N, Wang H, Ying Z, et al. Exon-intron boundary inhibits m6A deposition, enabling m6A distribution hallmark, longer mRNA half-life and flexible protein coding. Nat Commun 2023; 14:4172. 10.1038/s41467-023-39897-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Malcolm DB, Sommerville J. The structure of chromosome-derived ribonucleoprotein in oocytes of Triturus cristatus carnifex (Laurenti). Chromosoma 1974;48:137–58. 10.1007/BF00283960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McKnight SL, Miller OL. Ultrastructural patterns of RNA synthesis during early embryogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell 1976;8:305–19. 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Beyer AL, Christensen ME, Walker BW, LeStourgeon WM. Identification and characterization of the packaging proteins of core 40S hnRNP particles. Cell 1977; 11:127–38. 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Barnett SF, Northington SJ, LeStourgeon WM. Isolation and in vitro assembly of nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles and purification of core particle proteins. Methods in Enzymology, vol. 181, Academic Press; 1990, p. 293–307. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81130-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Conway G, Wooley J, Bibring T, LeStourgeon WM. Ribonucleoproteins package 700 nucleotides of pre-mRNA into a repeating array of regular particles. Mol Cell Biol 1988;8:2884–95. 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2884-2895.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].McAfee JG, Shahied-Milam L, Soltaninassab SR, LeStourgeon WM. A major determinant of hnRNP C protein binding to RNA is a novel bZIP-like RNA binding domain. RNA 1996;2:1139–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].König J, Zarnack K, Rot G, Curk T, Kayikci M, Zupan B, et al. iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010;17:909–15. 10.1038/nsmb.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Weighardt F, Biamonti G, Riva S. The roles of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP) in RNA metabolism. BioEssays 1996;18:747–56. 10.1002/bies.950180910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]