Abstract

Background:

Nicotine-containing electronic cigarette vaping (EC) has become popular worldwide and our understanding about effects of vaping on stroke outcome is elusive. Employing a rat model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO), the current exploratory study aims to evaluate the sex-dependent effects of EC exposure on brain energy metabolism and stroke outcomes.

Methods:

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats of both sexes were randomly assigned to air/EC vapor (5% nicotine Juul pods) exposure for 16 nights followed by randomization into three cohorts. The first cohort underwent exposure to air/EC preceding randomization to tMCAO (90 min) or sham surgery followed by survival for twenty-one days. During the survival period, rats underwent sensorimotor and Morris water maze (MWM) testing. Subsequently, brains were collected for histopathology. A second cohort was exposed to air/EC after which brains were collected for unbiased metabolomics analysis. The third cohort of animals was exposed to air/EC and received tMCAO/sham surgery and brain tissue was collected twenty-four hours later for biochemical analysis.

Results:

In females, EC significantly increased (p<0.05) infarct volumes by 94% as compared to air-exposed rats, 165 ± 50 mm3 in EC-exposed and 85 ± 29 mm3 in air-exposed, respectively, while in males such a difference was not apparent. MWM data showed significant deficits in spatial learning and working memory in EC sham or tMCAO groups compared to respective air groups in rats of both sexes (p<0.05). Thirty-two metabolites of carbohydrate, glycolysis, TCA cycle, and lipid metabolism were significantly altered (p≤0.05) due to EC, twenty-three of which were specific for females. Steady-state protein levels of hexokinase significantly decreased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed females; however, these changes were not seen in males.

Conclusion

Even brief EC exposure over two weeks impacts brain energy metabolism, exacerbates infarction, and worsens post-stroke cognitive deficits in working memory more in female than male rats.

Keywords: Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), metabolomics, estrogen receptor-beta, glycolysis, phospholipids

Graphical Abstract

Brief Summary:

Study Finds Disturbing Impact of #E-Cigarette Vaping on #Stroke Outcome in Female Rats. Brief Exposure Worsens Brain Energy Metabolism and Cognition After Stroke Emphasizing Urgent Need For Awareness

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (EC) are battery-powered nicotine delivery devices that have rapidly gained popularity as alternatives to conventional tobacco cigarettes for young never-smokers, current smokers, and smokers seeking to cease 1,2. Tobacco smoking remains a significant and preventable risk factor for ischemic stroke. On average, smokers experience strokes a decade earlier than non-smokers 3. Strikingly, among women, both the incidence and severity of ischemic strokes increase in those who smoke; furthermore, ischemic stroke among young women continues to rise 4,5. Corroborating these epidemiological findings, laboratory studies on adult female rats have shown that as short as two weeks of smoking-attributed nicotine exposure exacerbates ischemic brain damage 6.

In the brain, nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors which are ligand-gated ion channels that are highly permeable to calcium7. Under diseased conditions, excessive calcium buildup and mitochondrial dysfunction results in neuronal death 8. In a model of ischemia-reperfusion, nicotine exposure decreased glucose transport across the blood-brain barrier 9. Using an unbiased global metabolomics approach, studies now confirm that even two to three-week-long nicotine exposure alters metabolite levels in glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and lipid pathways, thus hindering energy metabolism in rat brains 6,10. Neurons derive most of their energy from oxidative metabolism and the reported defects in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) proteins and respiration after nicotine exposure likely aggravate defects in mitochondrial function and energy metabolism 6,11. These findings point to the fact that glucose metabolism and energy production could be altered due to nicotine exposure. Therefore, a logical question arises – Will EC-attributed nicotine exposure have similar effects on brain energy metabolism, and will it worsen stroke outcomes? Since continuing smoking after ischemic stroke increases the risk of recurrent and more disabling strokes 12–14, cessation of smoking is recommended to lower the risk of recurrence 14–16. Therefore, the current study evaluates the effects of EC vaping prior to induction of tMCAO on stroke outcomes in rats.

Cognitive impairment and dementia are major consequences of ischemic stroke and whether EC exposure will induce severe cognitive deficits requires investigation 17,18. Sex differences in post-stroke cognitive outcomes are well-documented, with women experiencing more severe cognitive effects than men 17,19. The current study, using transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) in adult rats, aims to investigate the sex-specific effects of EC exposure on post-ischemic brain damage and cognition.

Methods

Ethics Approval:

Animal usage and experimentation were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami and was in accordance with the US Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals:

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines 20. The details of animal handling, study design, randomization, blinding, sample size determination, estrous cycle monitoring, EC exposure, metabolomics data acquisition and analysis 6,10,21, tMCAO22, neurological deficit scoring 23, sensorimotor function testing using cylinder test 24, infarct volume evaluation 25, and Morris water maze24 testing are provided in Supplemental Materials.

Briefly, adult Sprague-Dawley rats of both sexes were randomly exposed to either air or EC vapor (5% nicotine Virginia tobacco Juul pods) for 16 days (Figure 1A). Subsequently, animals were divided into three cohorts. The first cohort of rats exposed to EC or air was further randomized to tMCAO (90 min) or sham surgery followed by survival for twenty-one days 22. During the survival period, rats underwent sensorimotor testing and Morris water maze (MWM) behavioral testing followed by brain collection for histopathological analysis 24. A second cohort was exposed to EC or air after which brains were collected and sent to Metabolon Inc. (Durham, North Carolina) for unbiased metabolomics analysis 6. The third cohort of animals was exposed to EC or air and received tMCAO or sham surgery after which they were sacrificed twenty-four hours post-surgery and brain tissue was collected for Western blot biochemical analysis 6.

Figure 1:

(A) Experimental design including the EC exposure paradigm delineated in the triangular diagram underneath the exposure period. (B) Cotinine levels in the brain of rats exposed to air or EC. (C, E) Representative images of cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the ipsilateral cortex before, during, and after tMCAO. (D, F) Ipsilateral CBF (presented as percentage of baseline) in tMCAO groups significantly decreases (p<0.05) during the occlusion period compared to baseline in both (D) female and (F) male cohorts. (n=7, “*” = p<0.05).

Statistical analysis:

Rats were randomized to EC or air exposures and the only a priori exclusion criterion was surgical failures. Sample sizes are indicated in the figure legends and Table S1. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Prism 9, CA, USA) and RStudio software (R version 4.1.1) and all data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used for MWM probe trial, hippocampal CA1 neuronal count, and metabolomics analysis26. A three-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used for CBF, cylinder test. MWM hidden platform and working memory. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses details are presented in Table S2 and in Supplemental Methods.

Availability of supporting data:

Data are available upon request.

Results

Confirming EC exposure in rat model:

First, we confirmed that nicotine is reaching the brain of rats following EC exposure. Cotinine, the main metabolite of nicotine, has a longer half-life and is a reliable marker of nicotine exposure27. Figure 1B shows presence of cotinine in male and female rat cortexes, confirming delivery of nicotine to the brain after EC exposure. Results did not show any sex-difference in brain cotinine levels. In the brains of air-exposed rats, cotinine levels were below detectable levels, and a negative output was received.

Since nicotine exposure reduces body weight and suppresses appetite, we determined the effects of EC exposure on body weight 28. As compared to pre-exposure body weight, EC-exposed female and male rats lost 7% and 6% of body weight (p<0.05), respectively, validating the physiological effects of nicotine-containing EC exposure (Figure S1). In contrast to EC-exposed animals, air-exposed rats showed continuous weight gain over the 16-day exposure period. Furthermore, nicotine-containing EC-exposure decreases estrogen receptor-β (ER-β) in the brain of female rats (Figure S2), as shown previously11.

EC exposure significantly worsens post-stroke infarction in female rats:

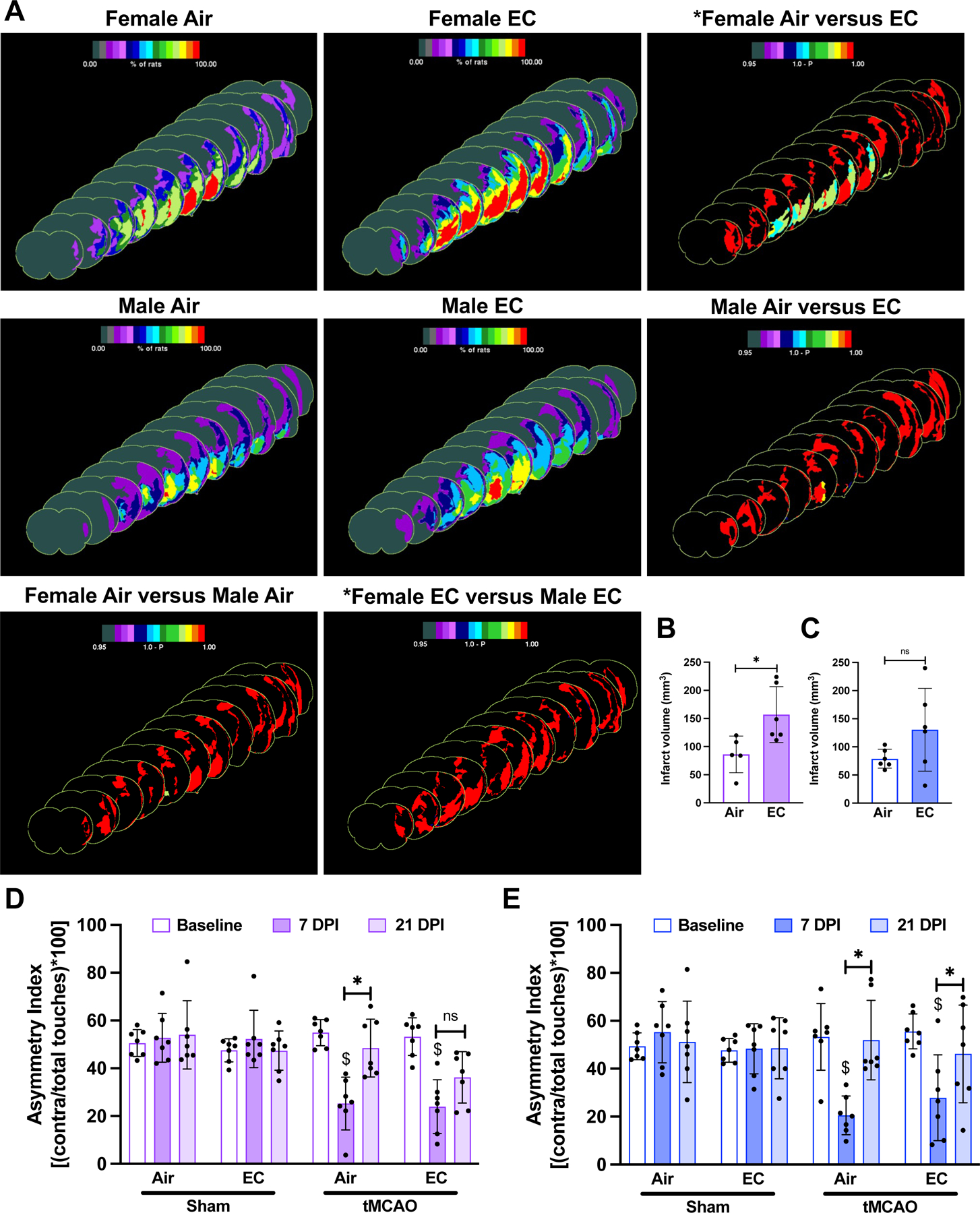

Next, we evaluated the effects of EC exposure on stroke outcomes. Animals exposed to EC or air underwent tMCAO or sham surgery and physiological variables such as pH, pCO2, pO2, plasma glucose concentration, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and cerebral blood flow (CBF) were monitored prior, during, and after surgery (Table S3). Post suture-insertion, we observed around 50% reduction from baseline CBF, confirming induction of ischemia. The CBF recovered to baseline at reperfusion in female, but not in male rats (Figure 1C-F). Twenty-one days after tMCAO/sham surgery, brains were collected for histopathological analysis. In female rats, EC exposure significantly increased infarct volume by 94% as compared to air-exposed animals. The mean infarct volumes were 85 ± 29 mm3 and 165 ± 50 mm3 for air and EC groups, respectively, a significant difference (p<0.05). In male rats, we observed a 57% increase in infarct volume after EC exposure as compared to air-exposed rats, however, the increase was not significantly different. The mean infarct volumes were 79 ± 15 mm3 and 124 ± 69 mm3 for air and EC groups, respectively (Figure 2A-C).

Figure 2:

(A) Infarct frequency heatmaps show the area of infarcted tissue as denoted by color intensity. The third heatmap in each row shows the within-sex significant difference (p<0.05) in infarct frequency between air-exposed and EC-exposed cohorts as determined by a Fisher’s exact test and color intensity represents 1.0 – p-value. (B) EC significantly exacerbates (p<0.05) ischemic infarction after stroke in female animals and (C) shows a trend of increased infarct volume in male animals as depicted in the shown graphs of infarct volume (mm3), respectively. (D-E) Cylinder test quantification is presented as asymmetry index and shows that at 7 DPI, tMCAO-exposed females exhibit significantly impaired sensorimotor function. EC- and tMCAO-exposed females do not significantly improve asymmetry by 21 DPI. tMCAO-exposed males exhibit significantly impaired sensorimotor function at 7 DPI. Air- and EC-exposed males significantly improve asymmetry index at 21 DPI compared to 7 DPI. (n=7 except for infarct volume of air- and tMCAO-exposed females where n=6; “*” = p<0.05, “$” = p<0.05 compared to baseline).

Post-stroke sensorimotor function did not recover in EC-exposed animals:

Since tMCAO impairs sensorimotor function, we conducted cylinder testing to assess function prior to EC or air exposure and 7- and 21-days post-ischemia (DPI) 24. At 7 DPI, mean asymmetry indexes were significantly decreased compared to baseline in animals of both sexes, indicating impaired unilateral sensorimotor function. Asymmetry indexes at 21 DPI were significantly increased compared to 7 DPI for all groups except for the female EC-exposed cohort, suggesting that EC exposure significantly impaired recovery of sensorimotor function in female rats (Figure 2D-E).

EC exposure resulted in significant deficits in learning and memory in both female and male rats:

Since cognitive decline after ischemic stroke is a major concern, we investigated effects of EC exposure on post-stroke cognition by using the MWM test. Figure 3A depicts latencies to find the hidden platform over the four days of acquisition trials. The results show a significant decrease in latency in finding the hidden platform on the fourth day in air sham and air-tMCAO in female rats, and only in air-sham male rats. However, such a phenomenon was absent in EC-exposed sham or tMCAO rats of both sexes, suggesting impaired spatial learning due to EC.

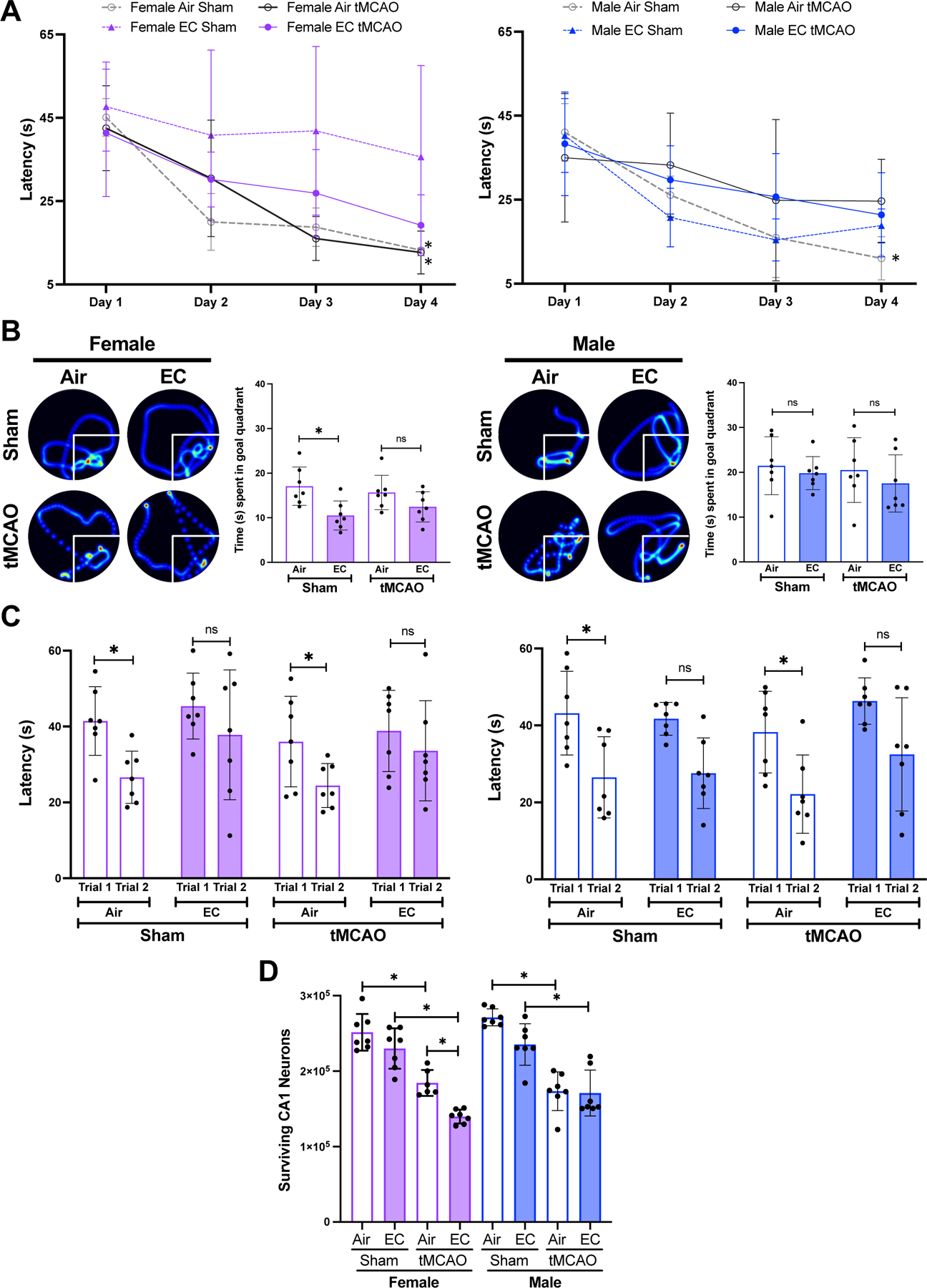

Figure 3:

(A) Line graph depicts latency (in seconds) to find the hidden platform. EC exposure did not reduce latency to find the hidden platform over the period of four day trial period, suggesting spatial learning deficits in animals of both sexes. (B) EC-exposed female rats spent significantly less time in the goal quadrant on probe trial testing (Day 5) than air-exposed, though only in sham cohort. EC-exposure did not significantly affect time spent in the goal quadrant in male rats. (C) Female and male rats exposed to EC did not significantly decrease the latency to find the platform in the second of paired trials in both sham and tMCAO cohorts, suggesting EC-induced impairment of working memory. (D) tMCAO in EC-exposed females significantly decreased CA1 neuronal survival compared to respective air-exposed rats, but not in males. (n=7 and “*” = p<0.05).

After the four-day learning period, probe trial testing showed that the EC- and sham-exposed female rats spent significantly less time in the goal quadrant as compared to the air-sham group. However, such a difference was not apparent in EC-exposed males, suggesting a possible sex difference in the effects of EC on spatial memory (Figure 3B). EC exposure did not alter post-tMCAO spatial memory in either sex.

On days six and seven, working memory testing data demonstrated that rats of both sexes exposed to air took significantly less time to locate a new platform location on the second of paired trials whereas EC-exposed animals failed to do so (Figure 3C). Importantly, in contrast to air-exposed rats, tMCAO in EC-exposed rats failed to reduce latency at second trial in animals of both sexes.

Overall, the observed deficits in learning and memory due to EC exposure could contribute to severe/long-term cognitive decline following stroke.

Since spatial learning and memory functions are dependent on the hippocampus and tMCAO affects neuronal survival 29,30, we quantified CA1 neuronal survival after tMCAO/sham in air/EC-exposed rat brains. EC exposure significantly decreased the number of surviving neurons in the hippocampal CA1 after tMCAO in females but not males compared to the respective air-exposed tMCAO groups (Figure 3D).

EC exposure significantly altered carbohydrate and energy metabolism in a sex-dependent manner:

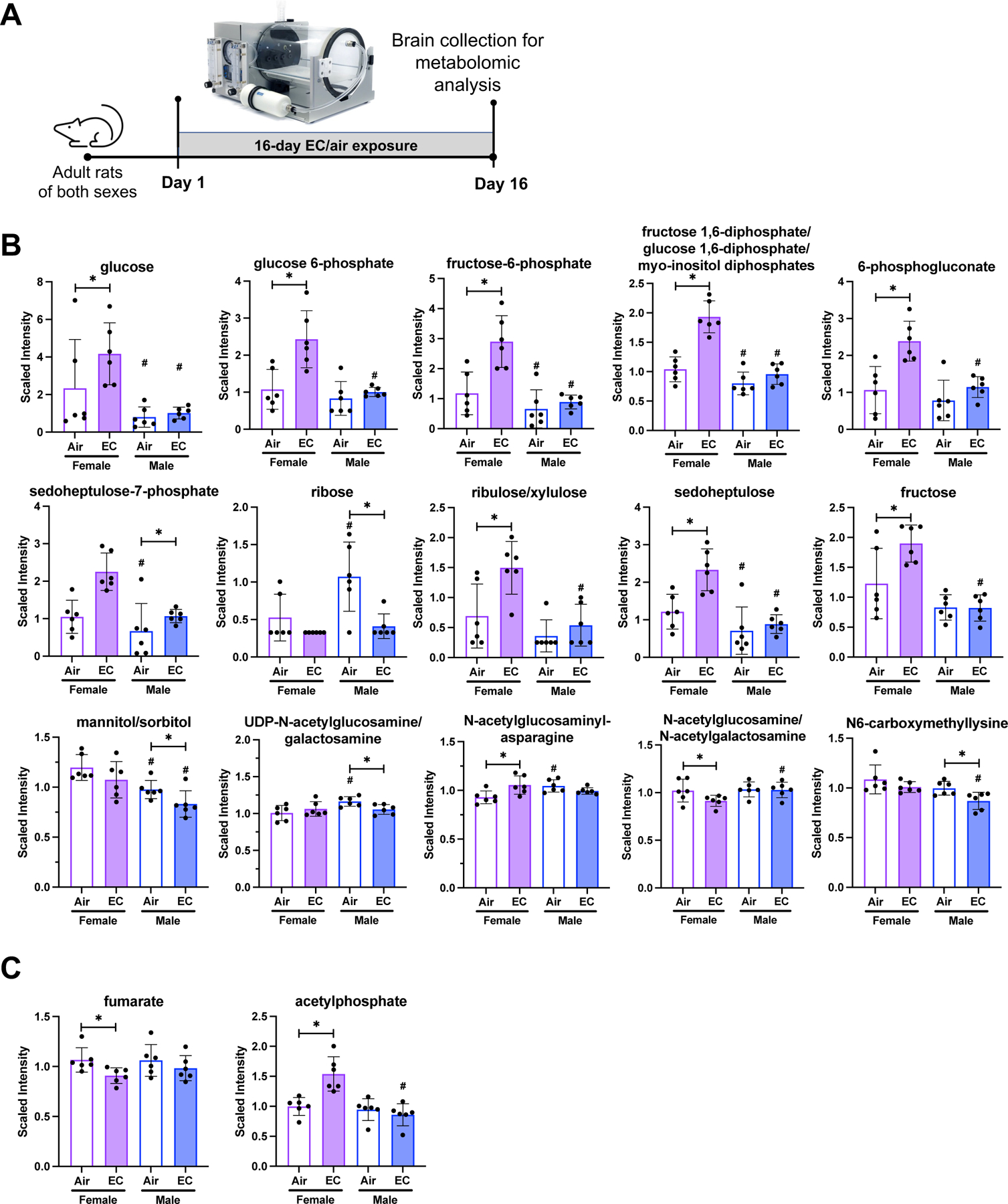

Since brain energy metabolism is a vital component of post-stroke mitigation of ischemic tissue damage and recovery of peri-infarct region tissue, we investigated carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in rat brains after EC exposure using an unbiased metabolomics approach (Figure 4A). Pathway analysis showed that EC exposure significantly increased (p<0.05) levels of glucose, glucose 6-phosphate, fructose 6-phosphate, and fructose 1,6-diphosphate/glucose 1,6-diphosphate/myo-inositol diphosphates only in the female EC cohort compared to female air-exposed rats. These data suggest changes in glycolysis in the female brain due to EC exposure; however, similar changes were not observed in EC-exposed male rat brains (Figure 4B; Tables S4a-g; Figures S3).

Figure 4:

(A) Experimental design indicates that brains were collected for metabolomics 16-days after air/EC exposure. (B) Glycolytic and carbohydrate metabolite levels significantly altered due to EC exposure include 10 metabolites only changing in females and 5 metabolites only changing in male animals compared to respective air-exposed group. (C) The TCA cycle metabolites fumarate and acetylphosphate were only significantly altered (p<0.05) in female rats exposed to EC compared to female air controls, and no TCA metabolite levels were significantly altered due to EC exposure in males. Metabolite levels are depicted as means with error bars denoting SD and individual values represented as dots. (n=6, “*” = p<0.05, “#” = p<0.05 compared to same exposure condition of the other sex).

In the pentose phosphate pathway and pentose metabolism, EC exposure in females significantly increased (p<0.05) 6-phosphogluconate, ribulose/xylulose, and sedoheptulose compared to air-exposed females. Sedoheptulose-7-phosphate was significantly increased (p<0.05) and ribose was significantly decreased (p<0.05) in male EC-exposed rats compared to male air-exposed rats (Figure S4).

In EC-exposed females, fructose was significantly increased (p<0.05) while mannitol/sorbitol significantly decreased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed males compared to respective air controls. Levels of the nucleotide sugar UDP-N-acetylglucosamine/galactosamine significantly decreased (p<0.05) in male EC-exposed rats when compared to the male air-exposed group. Aminosugar metabolism was altered in female EC-exposed rats with the metabolite N-acetylglucosaminylasparagine significantly increased (p<0.05) and N-acetylglucosamine/N-acetylgalactosamine significantly decreased (p<0.05) due to EC exposure.

Among the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) metabolites, fumarate was significantly decreased (p<0.05; Figure 4C; Tables S5a-b; Figure S5) in female EC-exposed animals compared to air-exposed female rats, and no significant TCA cycle alterations due to EC exposure were observed in the male cohort. Similarly, oxidative phosphorylation was only affected in female EC-exposed animals with the metabolite acetylphosphate significantly increased (p<0.05).

EC exposure significantly altered lipid metabolism in a sex-dependent manner:

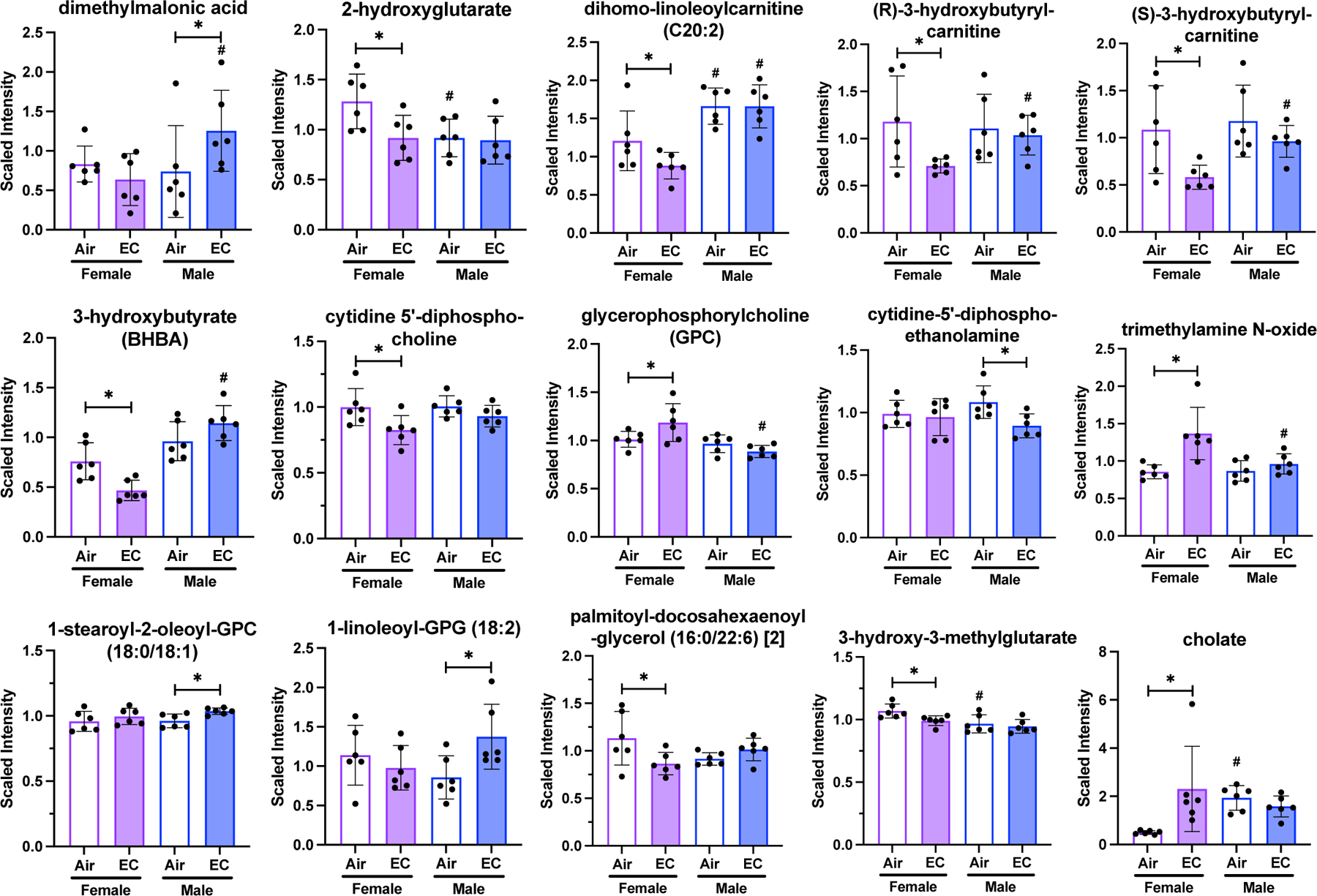

In a published study, we reported that nicotine exposure significantly alters lipid metabolism in female rats 10. Here, we present data showing that EC exposure results in significant changes in levels of lipid metabolites in fatty acid, phospholipid, phosphatidylcholine, lysophospholipid, diacylglycerol, mevalonate, and primary bile acid metabolic sub-pathways (Figure 5; Tables S6a-u; Figures S6-S8).

Figure 5:

Lipid metabolite levels are differentially altered in female and male animals exposed to EC compared to respective air-exposed animals. 11 metabolites were significantly changed in only female EC-exposed rats and 4 metabolites were significantly altered in only in EC-exposed male rats. Metabolite levels are depicted as means with error bars denoting SD and individual values represented as dots. (n=6, “*” = p<0.05, “#” = p<0.05 compared to same exposure condition of the other sex).

The fatty acid metabolites 2-hydroxyglutarate, dihomo-linoleoylcarnitine (C20:2), (R)-3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine, and (S)-3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine were significantly decreased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed females compared to air-exposed females. The only significant fatty acid metabolite change in EC-exposed male animals was an increase in dimethylmalonic acid. The ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) significantly decreased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed female animals compared to air-exposed females and no significant difference was found in EC-exposed male rats.

The phospholipid metabolite cytidine 5’-diphosphocholine significantly decreased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed females compared to air-exposed females. In contrast, other phospholipid metabolites, viz - glycerophosphorylcholine (GPC) and trimethylamine N-oxide were significantly increased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed females. Among EC-exposed males, cytidine-5’-diphosphoethanolamine was the only phospholipid metabolite that significantly changed, with a significant decrease (p<0.05). 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-GPC (18:0/18:1) and 1-linoleoyl-GPG (18:2), metabolites in the phosphatidylcholine and lysophospholipid pathways, were significantly increased (p<0.05) only in EC-exposed males compared to air-exposed. Phosphatidylcholine and lysophospholipid metabolites did not change in EC-exposed females. Palmitoyl-docosahexaenoyl-glycerol (16:0/22:6) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate, diacylglycerol and mevalonate metabolites, respectively, were significantly decreased in level in EC-exposed females, but not males. Lastly, the primary bile acid metabolite, cholate, was markedly and significantly increased (p<0.05) in EC-exposed females compared to air-exposed females.

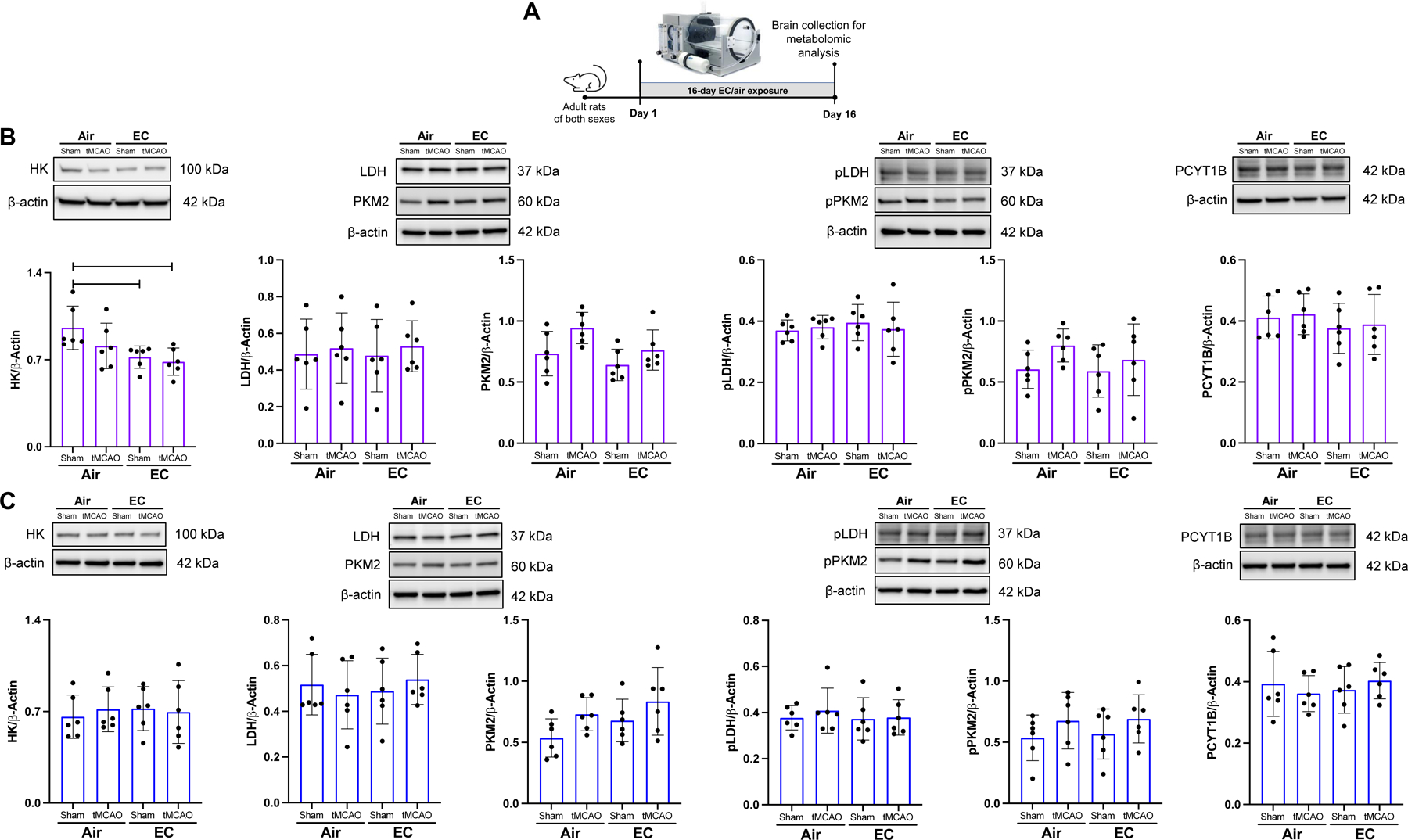

Effects of EC exposure on the enzymes of glycolysis and lipid metabolic pathways:

Since EC exposure altered cortical glycolytic and phospholipid pathway metabolites significantly, we evaluated steady-state protein levels of key enzymes of these pathways using Western blotting (Figure 6A). Hexokinase (HK) levels were significantly decreased (p<0.05) in the cortex of EC-exposed sham and tMCAO female rats, suggesting that EC exposure affects the rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis in female rats. HK levels were not altered by EC in the male cohort. We did not see any changes in phosphorylated or non-phosphorylated forms of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) under any experimental conditions. PCYT1B levels were not altered due to EC-exposure in female or male animals exposed to sham or tMCAO (Figure 6B-C).

Figure 6:

(A) Experimental design for Western blotting of glycolytic and phospholipid enzymes. (B) Graphs depict Western blot analysis of key enzymes. EC exposure significantly decreased levels of hexokinase in the cortex of female rats. (C) EC exposure did not change protein levels of glycolytic or lipid metabolism enzymes in the cortex of male rats. (n=6, “*” = p<0.05).

Discussion

Studies on ischemic stroke outcomes have highlighted sex-based differences, with women experiencing a disproportionate burden of stroke-related mortality, disability, and severity 31. Recent research surprisingly indicates higher ischemic stroke incidence in young women compared to young men, emphasizing the need to investigate sex-specific risk factors 5. Factors unique to women, such as menstruation, pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, and menopause, significantly impact ischemic stroke outcomes. The current study demonstrates that even sex-neutral factors like nicotine-containing EC exposure result in severe ischemic brain damage, decreased CA1 neuronal survival, and worsened post-stroke working memory in female rats compared to air-exposed females or age-matched air- or EC-exposed males. Although we observed a large infarction in EC-exposed female rats, CBF increased back to baseline at reperfusion in female, but not in male rats. The observed recovery in CBF at reperfusion in female rats may not be stable as a study using a model of global ischemia showed that nicotine exposure caused severe hypoperfusion one day after ischemia32. The chosen paradigm of EC exposure and achieved brain cotinine level were selected based on plasma or brain cotinine levels associated with impaired endothelial function in rats33.

At the achieved cotinine level in the brain, metabolomic pathway analysis revealed substantial changes in glycolytic metabolites in EC-exposed female rats compared to air-exposed controls, suggesting altered brain energetics. Notably, increased levels of glucose, glucose 6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, and fructose 1–6 diphosphate were observed. EC exposure also increased metabolites of fatty acids, phospholipids, phosphatidylcholines, lysophospholipids, diacylglycerols, mevalonate, and primary bile acids. Conversely, fewer changes were observed in EC-exposed male rats. The current findings that even a brief two-week EC exposure disproportionately affects energy metabolism and worsens post-stroke cognitive deficits in working memory in females prompts questions about the heightened vulnerability of female brains to EC and the underlying mechanisms. Although the current study lacks a mechanistic approach, potential mechanisms contributing to the observed severe ischemic damage in females due to EC based on prior literature are discussed below.

The literature consistently demonstrates the influence of female sex hormones on nicotine metabolism, with nicotine metabolizing faster in women than in men 34. Conversely, nicotine inhibits the activity of the steroidogenic aromatase enzyme, reducing circulating estrogen levels and instigating an early onset of menopause in women 35. In female rats, chronic nicotine exposure also reduces endogenous 17β-estradiol (E2) levels36. Endogenous or exogenous E2 mediates its neuroprotective effects through activation of estrogen receptors alpha (ER-α) and beta (ER-β). Activation of ER-β after tMCAO improves cognition and reduces infarction in female rats 30.

Nicotine exposure notably decreases membrane-bound and mitochondrial ER-β levels, directly impacting mitochondrial function11. Data presented in Figure S2 further confirms the deleterious effect of nicotine-containing EC on cortical ER-β protein levels. In rat brains, silencing of ER-β was found to reduce protein levels of mitochondria-encoded CIV subunits, while the activation of ER-β in isolated mitochondria increased CIV enzyme activity 11. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a significant contributor to ischemic brain damage, may worsen in EC-exposed female rats due to CIV subunits abnormalities. Additionally, decreased brain glycolysis potentially deteriorates neural function in EC-exposed females. Altered glycolytic processes and the accumulation of metabolites in the female brain due to EC exposure may lead to severe or prolonged hypoperfusion after tMCAO, necessitating further investigation.

The observed changes in lipid metabolism are important as lipids account for 50% of dry brain weight, the second-highest lipid-containing tissue after adipose tissues. Lipids contribute to the structural integrity and physical characteristics of cell and organelle membranes, act as bioactive signaling molecules, function in energy storage, and maintain homeostasis 37,38. Brain lipids mainly consist of cholesterol, phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and sphingolipids. Two major changes in phospholipid metabolism in females because of EC exposure include: the decrease in cytidine 5’-diphosphocholine and increase in GPC and trimethylamine N-oxide. Glycerophospholipids, including PC and PE, are the main phospholipid components of cell membranes 39. Alterations in the composition of PC and PE affects the stability, permeability, and fluidity of neural membranes, leading to neurodegenerative diseases. These alterations may be responsible for the observed severe infarction in EC-exposed female brains. Like other tissues, PC and PE of brain cells often control anchoring of membrane proteins, which may be responsible for nicotine-induced loss of ER-β in the female brain thus causing loss of E2-mediated ischemic neuroprotection. Secondarily, ischemia-induced activation of phospholipases causes degradation of phospholipids and produces arachidonic acid and prostaglandins, aggravating post-ischemic inflammation 40.

Ischemia is known to activate the innate immune response mediated by the inflammasome, causing pyroptosis41. Inhibiting inflammasome activation after oxygen-glucose deprivation improves post-ischemic neuronal survival in nicotine-exposed organotypic slice cultures 42. In a prior study, silencing of ER-β increased inflammasome activation, whereas ER-β-specific agonist treatment reduced inflammasome activation and ischemic cell death, suggesting that ER-β plays a role in regulating inflammasome activation 43. While it is necessary to confirm these findings, the aforementioned study suggests that nicotine-containing EC may increase pyroptosis by reducing ER-β, thus exacerbating ischemic brain damage in females.

Conclusion

The study indicates that brief exposure to nicotine-containing EC adversely affects brain energy metabolism and exacerbates ischemic brain damage in female rats, with potential implications for increased susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases. Key questions for future consideration include whether: (1) prolonged EC exposure could nullify sex differences in stroke outcomes, (2) EC effects in aged animals could have severe consequences, and (3) EC withdrawal might reduce severity of ischemia. The duration needed for EC withdrawal to mitigate ischemic effects warrants investigation. Future research should employ comprehensive, multidisciplinary approaches to tackle challenges posed by the EC epidemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Dr. Kunjan R. Dave for scientific discussion, Ms. Sophie B. Sinder for technical assistance, and Ms. Isha S. Shirvaikar for conducting statistical analyses using RStudio.

Funding:

This study was supported by funding to APR including AHA https://doi.org/10.58275/AHA.23TPA1142407.pc.gr.172288, Florida Department of Health # 20K09, and an Endowment from Drs. Chantal and Peritz Scheinberg.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BHBA

3-hydroxybutyrate

- CA1

cornu Ammonis 1

- CBF

Cerebral blood flow

- CC

Conventional tobacco cigarettes

- CIV

Complex IV

- DPI

Days post-ischemia

- E2

17β-estradiol

- EC

Electronic nicotine delivery system/Electronic cigarettes

- ER-β

Estrogen receptor-beta

- GPC

Glycerophosphorylcholine

- MWM

Morris Water Maze

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation system

- PC

Phosphatidylcholine

- PE

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- tMCAO

Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion

Footnotes

Consent for Publication: Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Raval reports employment by American Heart Association.

Supplemental Materials

Checklist

References

- 1.Siegel J, Patel SH, Mankaliye B, Raval AP. Impact of Electronic Cigarette Vaping on Cerebral Ischemia: What We Know So Far. Transl Stroke Res 2022. doi: 10.1007/s12975-022-01011-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose JJ, Krishnan-Sarin S, Exil VJ, Hamburg NM, Fetterman JL, Ichinose F, Perez-Pinzon MA, Rezk-Hanna M, Williamson E, American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary CCP, et al. Cardiopulmonary Impact of Electronic Cigarettes and Vaping Products: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank JA, Swafford KJ, Roberts JM, Trout AL, Stowe AM, Lukins DE, Grupke S, Pennypacker KR, Fraser JF. Smoking-Induced Sex Differences in Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy for Stroke. World Neurosurg 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.06.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah RS, Cole JW. Smoking and stroke: the more you smoke the more you stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010;8:917–932. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leppert MH, Ho PM, Burke J, Madsen TE, Kleindorfer D, Sillau S, Daugherty S, Bradley CJ, Poisson SN. Young Women Had More Strokes Than Young Men in a Large, United States Claims Sample. Stroke 2020;51:3352–3355. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz F, Raval AP. Simultaneous nicotine and oral contraceptive exposure alters brain energy metabolism and exacerbates ischemic stroke injury in female rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021;41:793–804. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20925164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007;47:699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toman J, Fiskum G. Influence of aging on membrane permeability transition in brain mitochondria. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes 2011;43:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s10863-011-9337-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sifat AE, Vaidya B, Kaisar MA, Cucullo L, Abbruscato TJ. Nicotine and electronic cigarette (E-Cig) exposure decreases brain glucose utilization in ischemic stroke. J Neurochem 2018;147:204–221. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SH, Timon-Gomez A, Pradhyumnan H, Mankaliye B, Dave KR, Perez-Pinzon MA, Raval AP. The Impact of Nicotine along with Oral Contraceptive Exposure on Brain Fatty Acid Metabolism in Female Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. doi: 10.3390/ijms232416075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raval AP, Dave KR, Saul I, Gonzalez GJ, Diaz F. Synergistic inhibitory effect of nicotine plus oral contraceptive on mitochondrial complex-IV is mediated by estrogen receptor-beta in female rats. J Neurochem 2012;121:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin X, Wang D. Five-Year Risk of Stroke after TIA or Minor Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1579–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1808913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Li S, Zheng K, Wang H, Xie Y, Xu P, Dai Z, Gu M, Xia Y, Zhao M, et al. Impact of Smoking Status on Stroke Recurrence. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e011696. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh NS, Parasram M, White H, Merkler AE, Navi BB, Kamel H. Smoking Cessation in Stroke Survivors in the United States: A Nationwide Analysis. Stroke 2022;53:1285–1291. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein KA, Viscoli CM, Spence JD, Young LH, Inzucchi SE, Gorman M, Gerstenhaber B, Guarino PD, Dixit A, Furie KL, et al. Smoking cessation and outcome after ischemic stroke or TIA. Neurology 2017;89:1723–1729. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong L, Briceno E, Morgenstern LB, Lisabeth LD. Poststroke Cognitive Outcomes: Sex Differences and Contributing Factors. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016683. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gall S, Phan H, Madsen TE, Reeves M, Rist P, Jimenez M, Lichtman J, Dong L, Lisabeth LD. Focused Update of Sex Differences in Patient Reported Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke 2018;49:531–535. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine DA, Gross AL, Briceno EM, Tilton N, Giordani BJ, Sussman JB, Hayward RA, Burke JF, Hingtgen S, Elkind MSV, et al. Sex Differences in Cognitive Decline Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e210169. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020;40:1769–1777. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20943823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford L, Kennedy AD, Goodman KD, Pappan KL, Evans AM, Miller LAD, Wulff JE, Wiggs BR, Lennon JJ, Elsea S, et al. Precision of a Clinical Metabolomics Profiling Platform for Use in the Identification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism. J Appl Lab Med 2020;5:342–356. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfz026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belayev L, Alonso OF, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat by intraluminal suture. Neurological and pathological evaluation of an improved model. Stroke 1996;27:1616–1622; discussion 1623. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ley JJ, Vigdorchik A, Belayev L, Zhao W, Busto R, Khoutorova L, Becker DA, Ginsberg MD. Stilbazulenyl nitrone, a second-generation azulenyl nitrone antioxidant, confers enduring neuroprotection in experimental focal cerebral ischemia in the rat: neurobehavior, histopathology, and pharmacokinetics. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2005;313:1090–1100. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr N, Sanchez J, Moreno WJ, Furones-Alonso OE, Dietrich WD, Bramlett HM, Raval AP. Post-stroke low-frequency whole-body vibration improves cognition in middle-aged rats of both sexes. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:942717. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.942717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao W, Ginsberg MD, Prado R, Belayev L. Depiction of infarct frequency distribution by computer-assisted image mapping in rat brains with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Comparison of photothrombotic and intraluminal suture models. Stroke 1996;27:1112–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.6.1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan X, Vrana K, Ding ZM. Cotinine: Pharmacologically Active Metabolite of Nicotine and Neural Mechanisms for Its Actions. Front Behav Neurosci 2021;15:758252. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.758252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Audrain-McGovern J, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking, nicotine, and body weight. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:164–168. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortin NJ, Agster KL, Eichenbaum HB. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nat Neurosci 2002;5:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nn834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pradhyumnan H, Reddy V, Bassett ZQ, Patel SH, Zhao W, Dave KR, Perez-Pinzon MA, Bramlett HM, Raval AP. Post-stroke periodic estrogen receptor-beta agonist improves cognition in aged female rats. Neurochem Int 2023;165:105521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2023.105521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rexrode KM, Madsen TE, Yu AYX, Carcel C, Lichtman JH, Miller EC. The Impact of Sex and Gender on Stroke. Circ Res 2022;130:512–528. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.d’Adesky N, Diaz F, Zhao W, Bramlett HM, Perez-Pinzon MA, Dave KR, Raval AP. Nicotine Exposure Along with Oral Contraceptive Treatment in Female Rats Exacerbates Post-cerebral Ischemic Hypoperfusion Potentially via Altered Histamine Metabolism. Transl Stroke Res 2021;12:817–828. doi: 10.1007/s12975-020-00854-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao P, Liu J, Springer ML. JUUL and Combusted Cigarettes Comparably Impair Endothelial Function. Tob Regul Sci 2020;6:30–37. doi: 10.18001/TRS.6.1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, Jacob P, 3rd. Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006;79:480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raval AP. Nicotine Addiction Causes Unique Detrimental Effects on Women’s Brains. J Addict Dis 2011;30:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raval AP, Hirsch N, Dave KR, Yavagal DR, Bramlett H, Saul I. Nicotine and estrogen synergistically exacerbate cerebral ischemic injury. Neuroscience 2011;181:216–225.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornemann T Mini review: Lipids in Peripheral Nerve Disorders. Neurosci Lett 2021;740:135455. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon JH, Seo Y, Jo YS, Lee S, Cho E, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Shin YS, Moon MH, An HJ, Wenk MR, et al. Brain lipidomics: From functional landscape to clinical significance. Sci Adv 2022;8:eadc9317. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc9317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. Glycerophospholipids in brain: their metabolism, incorporation into membranes, functions, and involvement in neurological disorders. Chem Phys Lipids 2000;106:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00128-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muralikrishna Adibhatla R, Hatcher JF. Phospholipase A2, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation in cerebral ischemia. Free Radic Biol Med 2006;40:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kigerl KA, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dietrich WD, Popovich PG, Keane RW. Pattern recognition receptors and central nervous system repair. Experimental neurology 2014;258:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.d’Adesky ND, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Bhattacharya P, Schatz M, Perez-Pinzon MA, Bramlett HM, Raval AP. Nicotine Alters Estrogen Receptor-Beta-Regulated Inflammasome Activity and Exacerbates Ischemic Brain Damage in Female Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Rivero Vaccari JP, Patel HH, Brand FJ, 3rd, Perez-Pinzon MA, Bramlett HM, Raval AP. Estrogen receptor beta signaling alters cellular inflammasomes activity after global cerebral ischemia in reproductively senescence female rats. J Neurochem 2016;136:492–496. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones J, Magri R, Rios R, Jones M, Plate C, Lewis D. The detection of caffeine and cotinine in umbilical cord tissue using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods 2011;3:1310–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raval AP, Saul I, Dave KR, DeFazio RA, Perez-Pinzon MA, Bramlett H. Pretreatment with a single estradiol-17beta bolus activates cyclic-AMP response element binding protein and protects CA1 neurons against global cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience 2009;160:307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.