Trauma and the Health Care System

The US health care system faces unprecedented rates of burnout and employee turnover. Although burnout is conventionally viewed as a byproduct of unmanaged, occupational stress, its symptoms often overlap and coexist with manifestations of traumatic stress. Understanding the role of trauma in our health care environment may elucidate underlying causes of our current crisis and aid in finding solutions.

Trauma is one of the most underrecognized epidemics in the world, with nearly 90% of adults experiencing at least 1 trauma in their lifetime.1 Trauma can be any perceived harm with lasting, adverse effects on one’s functioning or well-being.2 Examples include physical or emotional abuse, neglect, discrimination, natural disasters, medical illness, or community violence. These often “unspeakable” events have far-reaching impacts on personal and public health. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including abuse, neglect, and household challenges, have been linked to future depression, substance use disorder, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.3 When individuals face life-threatening circumstances, their psychological response is often to deny, defend, and bury their experience without addressing it.4 Unfortunately, such responses can lead to intrapsychic suffering, physical illness, relational conflicts, and the perpetuation of systemic structures that allow everyday violence and trauma to recur.

Due to its ubiquitous nature, patients and communities are not the only ones affected by trauma; health care workers and systems that provide care are vulnerable, too. We have been expected to effortlessly suspend parts of ourselves to do our jobs and pick those parts back up when we leave. When the world unravels in the wake of a pandemic, systemic oppression, geopolitical turmoil, gun violence, and natural disasters, society expects us on the front lines. We are asked to be impervious to the strain, face the harsh realities of societal failures (eg, poverty, housing insecurity, severe unmet basic needs), and serve as containers for the pain. But we are humans first. We bring our beating hearts and tired souls to the job. We carry our own traumas, in addition to the secondary traumas and moral distress inherent to our professions.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, national experts in physician burnout asked health care workers what they needed. The response was loud and clear: “Hear me, protect me, prepare me, support me, and care for me.”5 Organizations are not machines. They are “biocratic.” They live, adapt, and experience pain just like all living organisms.6 This phenomenon was palpable as the pandemic unfolded across the globe. Uncertainty, weariness, fear, and loneliness among employees escalated and erupted into what has been referred to as the Great Resignation, but what might be better understood as the Great Reevaluation. Are our jobs in their present iteration sustainable and compatible with well-being? In order for us to continue, health care workers need to feel connected, less lonely, and seen, genuinely seen.

At this watershed moment, our health care system has a unique opportunity to harness this sense of urgency and chart a new course. In response to ACEs, socioeconomic inequities, and the ongoing impact of everyday discrimination, trauma-informed strategies represent a deliberate divergence from traditional dysfunction and disorder mindsets toward more strength-based adaptation pathways.7 We submit that the path to our own revival requires trauma- and resilience-informed leaders using knowledge of neurobiology to cultivate well-regulated organizations that center on healing and foster well-being for everyone within the health care system, for those of us who serve and for those whom we serve.

Trauma-Informed Organizational Leadership

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a framework that systematically applies current understanding of trauma and healing to practice, policy, and organizational culture. Evidence shows that TIC creates healing milieus, which lead to optimal outcomes in multiple core organizational objectives, such as worker well-being and satisfaction, systems functioning, and cost-effectiveness.8 Trauma-informed approaches are key in recognizing, alleviating, and preventing suffering in people, systems, and society, and in helping all of them thrive. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a trauma-informed organization strives to meet 4 criteria: 1) Realize the widespread impact of trauma, 2) Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma, 3) Respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into practice, and 4) actively Resist retraumatization.2

Translating SAMHSA’s 4 Rs into organizational change involves reviewing current practices, assessing organizational readiness, identifying priorities, and monitoring impact. A recently validated set of trauma-informed educational competencies may inform trauma-informed health care practices.9 Applying these concepts, one human service agency underwent a multiyear project by implementing employeewide TIC training, coaching TIC champions, and collaborating with leadership on trauma-informed policy review. Their interventions resulted in improved staff satisfaction and patient retention in treatment.10 https://traumainformedoregon.org/Trauma-Informed Oregon through Oregon Health Authority distributes an interactive roadmap to TIC,11 which includes a workgroup that reviews policies, practices, and environment with a trauma lens. The Institute for Trauma-Informed Care through University Health in Texas has developed systemwide interventions, including guides for trauma-informed performance improvement conversations, TIC onboarding modules, recharge rooms for staff, marketing materials from leadership describing TIC as a mission of their organization, policy language revision, and music and art therapy.12

Looking toward the business sector, non–health care organizations have begun to explore trauma-informed workplaces as a means to support employees in navigating uncertainty and instability, shortages and delays, and blurred work/home responsibilities. Several models of effective leadership already align with trauma-informed principles. For example, relational leadership emphasizes leader–member exchange, and interpersonal trust parallels trauma-informed ideals of safety, trustworthiness, and collaboration.13 Similarly, the emotional intelligence leadership framework highlights the importance of self-awareness and self-regulation in connecting with employees.14 Collectively, these skills align with TIC’s focus on empowerment, by engaging in self-reflection, drawing on others’ strengths, and making concerted efforts to hear all perspectives.

The authors of this commentary believe that a TIC framework can effectively guide health care leadership at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels. Trauma-informed leaders share key qualities, such as authentic warmth and nonjudgmentalism. They take necessary steps to promote physical and psychological safety and create a “culture of wellness” in their work ecosystem, which has been proposed to move organizations from burnout to resilience.15 Trauma-informed leaders act as “servant leaders,” who view their employees as resources to be developed rather than tools to be used.16 Ultimately, leaders can usher in a new era of posttraumatic growth by recognizing that all people, including themselves, can struggle as a result of past and ongoing traumatic experiences. They can acknowledge these responses are typical and go on to model self-compassion to stave off chronic symptoms of trauma in themselves and their team.17

In the following section, the authors provide specific actions for how trauma-informed leaders can advance organizational success and resist setbacks by proactively cultivating cultural change that emphasizes SAMHSA’s 6 core principles of TIC: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues.2 These principles help meet health workers’ stated needs to feel heard, protected, prepared, supported, and cared for. The authors of this commentary also developed the Table through an iterative process of describing actions aligned with SAMHSA’s 6 principles. These suggestions are based on the collective expertise of this group, developed over years of study and experience. The goal for this Table is to help TIC-oriented health care leaders keep employees connected to and supported by their institutions while working to create robust systems that can overcome emerging crises.

Table:

Interventions for leading trauma-informed organizational change at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels in alignment with SAMHSA’s 6 principles of trauma-informed care

| TIC principles | Levels of intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Description | Individual | Interpersonal | Structural |

| 1. Safety | Safety is a top priority. Aim to help staff and the people they serve feel physically, psychologically, and emotionally safe. | Recognize signs and symptoms of feeling personally unsafe. Utilize grounding skills to self-regulate (eg, square breathing, getting out in nature, mindful awareness). |

Recognize signs and symptoms of patients, families, and staff feeling unsafe or being hyper- or hypoaroused. Learn basic deescalation techniques to respond to agitated behavior in the workplace. Participate in trauma-informed incident debriefing after challenging events. Ensure that staff are trained in trauma-informed clinical skills for patient care. |

Commit to establishing a culture of safety that promotes healing and well-being throughout the system, with evaluation measures in place to work toward continual improvement.18

Create policy signage indicating that discrimination, threats, and/or violence will not be tolerated. Consider training for and implementation of trauma screening if appropriate referrals for care can be made. Implement an incident reporting system for disruptive behavior. Create private, quiet spaces where patients, families, and staff can find calm in otherwise stimulating environments. Make behavioral emergency response teams available, in addition to rapid response teams. Bolster physical safety in the workplace (eg, easy access to exit doors, metal detectors, panic buttons). Collaborate with security personnel for a shared understanding of threshold for public safety involvement if initial deescalation efforts are ineffective. Ask employees what they need to feel safe enough to do their job.6 |

| 2. Trustworthiness and transparency | Operations and decisions are conducted transparently with the goal of building and maintaining trust. | Bring your authentic self to your work. Be honest with yourself about how your experiences have impacted you. Acknowledge both your strengths and the areas in which you need to grow. Identify your own triggers so that you can respond productively and effectively rather than react. |

Explain why decisions are made both for patients (eg, a requested drug is unavailable) and for employees (eg, there are regulatory reasons why a clinic schedule cannot be changed). Inform patients about institutional responsibilities for confidentiality and obligatory reporting. Invest time to orient patients to the practice (eg, team members, trainee graduation timelines, expectations for timeliness of responses to requests). Acknowledge when you have reached a point of limitation and need additional support. |

Include a commitment to ensuring trauma-informed services and approaches to care in the institution’s mission statement and written policies. Publicly acknowledge the challenges of working in health care. Leaders should role model vulnerability and resilience for their employees. Clearly explain processes for hiring, firing, scheduling, and other aspects of human resource management. Provide advance notice of organizational changes with an opportunity for multidirectional input (eg, public commentary period). Make patient-facing policies clear, readily accessible, and available in multiple languages. Leaders should aim for clear, consistent messaging in written and verbal communication. Share patient and employee satisfaction data and indicate next steps to address dissatisfaction. |

| 3. Peer support | “Peers” refers to individuals with lived experiences of trauma. Peer support and mutual self-help are key vehicles for promoting recovery and healing. | Identify people doing similar work who can support you and whom you can support, too. | Share vulnerability to gain and inspire hope and healing. Support your peers in need. Create formal and informal opportunities for peers to connect, inside and outside of work. |

Encourage and support employee resource groups as a best practice to help bolster belonging in an organization. Provide employees with a list of active peer support networks and resources. Utilize social media (eg, Doximity, KevinMD) to promote peer engagement. Provide patients with a resource list of community groups that provide trauma-informed support (eg, shelters, bereavement groups, domestic violence support, diabetes support group, AA, NA, NAMI, Al-Anon). Offer financial and time-based support for employees to form their own academic groups or engage in others that can offer peer support (eg, TIHCER, AVA). Create peer support opportunities for leaders across and outside of health care systems. Engage in advocacy to support funding of prompt and confidential healing and recovery services for all staff. |

| 4. Collaboration and mutuality | Healing happens in relationships and the meaningful sharing of power and decision making. Everyone has a role to play in a trauma-informed approach. | Be mindful of your privileges and how you use your power and resources for the good of self and others. Develop awareness of your limitations and when collaboration may temper the effects of individual burnout. |

Work with others in decision-making processes. Recognize the hierarchical nature of many teams. Create inclusive learning and decision-making circles to reduce hierarchy and create community. Engage in and incorporate input from 360-degree feedback processes. Invite and integrate input from team members to gain insight about how to be more collaborative. Acknowledge and apologize for mistakes and develop a plan to address their impact. |

Develop organizational standards for interprofessional, team-based care. Provide training in how to establish collaborative working relationships and psychologically safe working environments. Provide coaching for individuals and teams in need of remediation. Develop partnerships between patients, staff, trainees, administrators, and leaders. Collaborate with mental and behavioral health and social services team members to ensure that patients have adequate access to these services as an integral component of care. Partner with community practitioners and referral agencies to foster a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach to trauma-informed services. Identify and work toward repairing any unhealthy power dynamics in care delivery and health education. |

| 5. Empowerment, voice, and choice | Offer patients and employees choice, recognize and build upon their experiences and strengths, and support their autonomy. | Acknowledge and celebrate your inner voice and knowing. Engage in self-reflection (eg, narrative medicine, reflective writing). Engage in restorative and healing practices (eg, exercise, yoga, music, dance, the arts). Learn how to share your perspectives clearly and forthrightly. |

Encourage patients to speak openly with their health care teams about needs for a trauma-informed approach. Give team members autonomy to make independent decisions. Elevate the voices of those who are not always heard in decision-making processes. Broaden perspective by recruiting new collaborators to existing projects. |

Include voices of all involved or affected by a course of action (including patients) in organizational committees. Whenever possible, provide choices and avoid unilateral edicts. Make quality improvement initiatives available to all employees. Encourage everyone to report medical errors and mistreatment. Make reporting safe, easy, and accessible. Compensate people (including patients who are serving on patient advisory boards) appropriately for their time. Create opportunities for clinical team members to design and undertake project improvement initiatives. Hold listening sessions to obtain data about the patient and employee experience and ideas for action, such as the Mayo Clinic’s Listen-Sort-Empower framework.19 |

| 6. Cultural, historical, and gender issues | Move past biases, leverage the healing power of cultural connections, and incorporate policies and processes that recognize and address historical trauma. | Develop an awareness of your unconscious biases (eg, Implicit Association Test) and the way they impact decision making. Develop strategies to mitigate unconscious biases. Recognize that trauma can be passed down through history and communicated through community dialogue. Be aware of how you show up in spaces and the impact of your presence. Ask yourself, “Do I help create safety for others in the spaces that I occupy?” |

Help people explore what they can do to contribute, and invite them in. Channel the desire to prevent needless suffering both in caring for patients and in caring for colleagues. |

Ensure diversity of teams across ages, races, abilities, genders, and nations of origin. Act with the understanding that we are better together. Conduct periodic institutional safety assessments with a focus on physical and psychological safety, as a part of environmental climate surveys.18 Participate in and integrate feedback from external organizational DEI evaluations (eg, White Coats for Black Lives, Racial Justice Report Card). Review and edit written policies and procedures to ensure that the language is inclusive and supportive. Codify inclusion, belonging, access, diversity, and justice in institutional policies. |

AA, Alcoholics Anonymous; AVA, Academy on Violence and Abuse; DEI, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; NA, Narcotics Anonymous; NAMI, National Alliance on Mental Illness; TIC, trauma-informed care; TIHCER, Trauma-Informed Health Care Education and Research.

Trauma-Informed Organizational Change

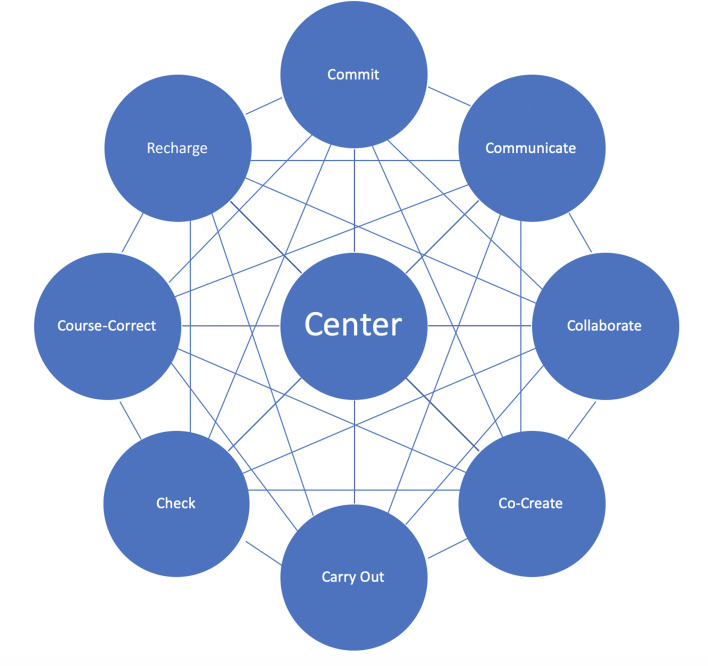

The Figure depicts the 9 Cs of trauma-informed organizational change, a conceptual model we have designed as TIC experts and health care professionals for anyone seeking to lead the health care system through trauma-informed, healing-centered transformation. This process is nonlinear, like the interconnected web in the Figure, and remains flexible and responsive to the changing climate within and outside of an organization over time. We describe one possible yet nonprescriptive sequence in the Figure.

Figure:

The 9 Cs of trauma-informed organizational change.

Centering: Emotion regulation is a key competence associated with trauma-informed and effective leadership.20 Periodically take a moment to breathe slowly and mindfully or use other grounding strategies to center yourself within your community in a place of calm. Acknowledge shared core values, the current state of your organization, and new perspectives as they emerge.

Commit: List the reasons why a commitment to a trauma-informed approach is part of your institution’s core mission.

Communicate: Engage in respectful, transparent, and reliable communication as key components in building a safe and trustworthy environment.

Collaborate: Invite ideas from diverse constituencies to ensure that action items meet the expressed needs of those who are learning, working at every level, and ultimately receiving care.

Co-create: Learners, patients, and staff who have not historically been engaged by leadership can be key contributors with lived experience and fresh ideas for change.

Carry Out: The Table outlines potential trauma-informed organizational change interventions at the individual, interpersonal, and structural levels. Additional resources for trauma-informed organizational change include the University of Buffalo Trauma-Informed Organizational Change Manual21 and the National Council for Mental Wellbeing’s Fostering Resilience and Recovery: A Change Package for Advancing Trauma-Informed Primary Care.7

Check: Assess subjective and objective measures in both process and outcomes, including changes in knowledge, policies, procedures, staff and patient satisfaction, health outcomes, and financial implications. Organizational assessments such as the TICOMETER22 and Survey for Trauma-Informed Systems Change20 can examine trauma-informed culture as a starting point and may complement existing assessments of workforce well-being.

Course-correct: Reflect and assess where your organization resides throughout this iterative process and recalibrate as needed. This may mean revisiting previous steps as part of the change process.

Recharge: Support staff in policies and practices that reinvigorate, mitigate burnout and secondary traumatic stress, and promote well-being and healing.

Current and Future Considerations

TIC has not yet become widely adopted as a standard practice, despite its basis in biologic science and its growing popularity in health care and non–health care industries alike. Adapting TIC to leadership and organizational well-being is a relatively new application of this framework, and TIC has not been broadly studied as a measure of healthy workplaces. Health care administrators might desire solid data that show financial benefits from TIC implementation; however, this research is still in progress.

Meaningful change takes time, particularly when recovering from collective trauma, ongoing burnout, and structural inequities. Interventions that have the highest impact occur at the organizational rather than the individual level, which requires thoughtful planning.23 Although most health care systems intend to support person-centered care, becoming trauma-informed necessitates a paradigm shift. Ultimately, for cultural transformation to take place, leadership must take initiative, engage employees, collaborate across stakeholders, and direct adequate resources to the efforts. The goal of this paper is to highlight and honor the exploratory nature of trauma-informed systems change and accommodate wide thought, creativity, and innovation to expand the framework of trauma-informed principles, meaningfully and sustainably.

Final Call to Action

Of all the longstanding and rising challenges currently facing the US health care system (staffing shortages, practitioner burnout, workplace violence, compassion crises, the Great Resignation, the “quality chasm,” health inequities, medical racism, medical mistrust, medical fear) no framework to date has been able to fully provide effective solutions. When Maxine Harris and Roger D Fallot coined the term “trauma-informed care,” they described it as a “vital paradigm shift” for treating patients with a history of trauma.24 More than 20 years later, applications of TIC continue to expand and offer innovative strategies for leaders and changemakers at all organizational levels. TIC can empower leaders to approach the practice and policies of health care in ways that nurture healthy and robust institutions, rebuild a dedicated and resilient workforce, and provide care that honors individuals’ dignity and human rights.

The path forward involves trauma- and resilience-informed systems of care, models that support the core mission of healing that compelled most of us to enter the health care profession. In the words of Sandra Bloom, psychiatrist and TIC leader, “To lead any organization in a time of significant change means leading a revolution in understanding human nature and the fundamental causes of human pathology that are endangering all life on this planet, and then helping organizational members develop skills to positively influence the changes necessary.”6

Acknowledgments

Trauma-Informed Health Care Education and Research Collaborative. Sadie Elisseou, MD, and Andrea Shamaskin-Garroway, PhD, are co-first authors.

Disclaimer.

The views expressed in this manuscript are the authors’ own and not an official position of their affiliated institutions.

Footnotes

Author Contributors: Each author, including Sadie Elisseou, MD, Andrea Shamaskin-Garroway, PhD, Avi Joshua Kopstick, MD, Jennifer Potter, MD, Amy Weil, MD, FACP, Constance Gundacker, MD, MPH, and Alisha Moreland-Capuia, MD, contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and drafting of the final manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

Funding: None declared

References

- 1. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537–547. 10.1002/jts.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman JL. Trauma and recovery. 2015th ed. New York: BasicBooks; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134. 10.1001/jama.2020.5893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bloom SL. A biocratic paradigm: Exploring the complexity of trauma-informed leadership and creating presence. Behav Sci. 2023;13(5):355. 10.3390/bs13050355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Council for Mental Wellbeing . Fostering resilience and recovery: A change package. 2019. Accessed August 2023. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/resources/fostering-resilience-and-recovery

- 8. Hambrick EP, Brawner TW, Perry BD, et al. Restraint and critical incident reduction following introduction of the neurosequential model of therapeutics (NMT). Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2018;35(1):2–23. 10.1080/0886571X.2018.1425651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berman S, Brown T, Mizelle C, et al. Roadmap for trauma-informed medical education: Introducing an essential competency set. Acad Med. 2023;98(8):882–888. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hales TW, Green SA, Bissonette S, et al. Trauma-informed care outcome study. Research on Social Work Practice. 2019;29(5):529–539. 10.1177/1049731518766618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trauma Informed Oregon . Home Page. Accessed December 2023. https://traumainformedoregon.org/

- 12.Sebton S, Trauma-Informed Health Care Education and Research Collaborative (TIHCER) . Trauma-Informed Care: Creating Safe and Supportive Environments.. Accessed 2 October 2023. https://www.pacesconnection.com/g/national-trauma-informed-health-care-education-and-research-tihcer-group/resource/tihcer-zoom-april-2023-sarah-sebton

- 13. Brower H, Schoorman F, Tan H. A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader–member exchange. Leadersh Q. 2000;11(2):227–250. 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00040-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence. Emotion. 2001;1(3):232–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Rodriguez A, Logan D. Wellness-centered leadership: Equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):641–651. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahon D. Trauma-informed servant leadership in health and social care settings. MHSI. 2021;25(3):306–320. 10.1108/MHSI-05-2021-0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koloroutis M, Pole M. Trauma-informed leadership and posttraumatic growth. Nurs Manage. 2021;52(12):28–34. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000800336.39811.a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moreland-Capuia A, Dumornay NM, Mangus A, Ravichandran C, Greenfield SF, Ressler KJ. Establishing and validating a survey for trauma-informed, culturally responsive change across multiple systems. J Public Health (Berl). 2023;31(12):2089–2102. 10.1007/s10389-022-01765-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swensen S. Listen-Sort-Empower: find and act on local opportunities for improvement to create your ideal practice. Accessed 18 January 2024. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767765

- 20. Haver A, Akerjordet K, Furunes T. Emotion regulation and Its iumplications for leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2013;20(3):287–303. 10.1177/1548051813485438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute on Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care (ITTIC), University at Buffalo School of Social Work . Trauma-Informed Organizational Change Manual. 2019–2022. Accessed 8 August 2023. https://socialwork.buffalo.edu/social-research/institutes-centers/institute-on-trauma-and-trauma-informed-care/Trauma-Informed-Organizational-Change-Manual0.html

- 22. Bassuk EL, Unick GJ, Paquette K, Richard MK. Developing an instrument to measure organizational trauma-informed care in human services: The TICOMETER. Psychology of Violence. 2017;7(1):150–157. 10.1037/vio0000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195–205. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris M, Fallot R. Using trauma theory to design service systems. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 2001;2001(89):3–22. 10.1002/yd.23320018903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]