Abstract

Background

Population-level tracking of hospital use patterns with integrated care organizations in patients experiencing homelessness has been difficult. A California law implemented in 2019 (Senate Bill 1152) aimed to ensure safety for this population after discharge from the hospital by requiring additional documentation for patients experiencing homelessness, which provides an opportunity to evaluate hospital use by this population.

Methods

In a large integrated health system in California, patients experiencing homelessness were identified through documentation change requirements associated with this law and compared with a matched group from the general population.

Results

Patients experiencing homelessness had increased rates of hospital readmission after discharge compared to the general population matched on demographics and medical comorbidity in 2019 and 2020. Any address change in the prior year for patients was associated with increased odds of emergency department readmission. Patients experiencing homelessness, both enrolled in an integrated delivery system and not, were successfully identified as having higher readmission rates compared with their housed counterparts.

Conclusion

Documentation of housing status following Senate Bill 1152 has enabled improved study of hospital use among those with housing instability. Understanding patterns of hospital use in this vulnerable group will help practitioners identify timely points of intervention for further social and health care support.

Introduction

Homelessness is associated with some of the highest levels of cross-sectoral inequities, including health care outcomes, in high-income countries.1,2 Prior studies have shown that poor health outcomes are deeply intertwined with a lack of basic human needs, such as food and shelter.3 The illness burden among people experiencing homelessness results in the high health care costs incurred by this population, leading to higher levels of hospital spending compared with the general population.4,5 California has the largest population of people experiencing homelessness in the country.6 Senate Bill (SB) 1152 was passed to curb this crisis within hospitals. Effective January 1, 2019, this bill instructs hospitals to develop specific discharge protocols for patients experiencing homelessness who are discharged from hospitals, including discharges from the emergency department (ED).7 Hospital discharge is an opportune moment to intervene with integrated care to reduce low-value hospital use among patients experiencing homelessness.5,8 Prior research to identify hospital use by patients experiencing homelessness usually relied on data elements reported in the electronic medical record that indicated homelessness, and these data elements were frequently far from universal in identifying these vulnerable patients.6,9 This law therefore provides an opportunity to identify patients experiencing homelessness through hospitalization documentation changes.

There are limited data regarding hospital use by this vulnerable population, especially in integrated care settings, after the implementation of SB 1152. A recent study has shown high readmission rates for patients experiencing homelessness in another health system outside of California.10 Due to its requirements, SB 1152 prompted Kaiser Permanente Northern California to establish standardized electronic health record (EHR) documentation requirements for the care of patients experiencing homelessness who are discharged from its hospitals and EDs in association with workflow changes to ensure that patients who are experiencing homelessness have their medications filled free of charge at the time of discharge and are offered safe shelter options and clothing. This included requirements to have hospital medicine physicians and social workers add specific documentation to the hospital chart at the time of discharge. This standardized documentation provided an opportunity to identify patients who were clinically found to be experiencing homelessness but would otherwise not have had specific documentation identifying them as such. In addition, these interventions would, in theory, be an additional layer of support to reduce hospital use and improve outcomes for this vulnerable population. This study group has recently shown that a composite outcome using hospital discharge documentation as a result of SB 1152 in addition to other diagnoses related to homelessness has moderate sensitivity and specificity in predicting patient homelessness at the time of hospital discharge.11 There is scarce evidence about the effects of SB 1152. This study assessed readmission rates among hospitalized patients experiencing homelessness compared with a similar hospitalized population not experiencing homelessness within a large integrated health system, identified using documentation in the EHR after implementation of SB 1152 in California.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study following adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) hospitalized in Kaiser Permanente Northern California Medical Centers serving more than 4.1 million patients between January 1, 2019, and December 1, 2020. A control group was created from the general patient population at Kaiser Permanente Northern California without any documentation specific to homelessness using 1:2 propensity score matching on patient Elixhauser12 comorbidities and demographics (n = 8606). Patients were excluded if they died during their first hospitalization in the study period.

Measures

Patients were identified as experiencing homelessness if they had: 1) SB 1152–specific documentation signifying social worker and clinician care for patients who are unhoused, including the hospital medicine physician using in the discharge summary a specific dot phrase that is part of the regional standardized discharge summary dot phrase and flowsheet documentation by the social worker confirming resources given to the patient as stipulated in SB 1152, 2) a homelessness diagnosis code, or 3) homelessness documented in the address section of the patient’s health record within the extensive integrated Kaiser Permanente Northern California EHR (n = 4303). The primary outcome was 30-day readmission rate to the hospital or ED, and secondary outcomes included length of index hospitalization and time to any readmission. Patient address changes in the EHR could be a marker for potential housing instability. The number of address changes in the year preceding the study period (for both groups housed and unhoused), months of enrollment in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health system, and whether the index hospitalization occurred during the COVID-19 lockdown period were used as covariates in all models studied.

Statistical analyses

Counts for the primary and secondary outcomes were compared using χ2 and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between homelessness status and readmission rates. Negative binomial regression was used to analyze the association between homelessness and the length of the index hospitalization. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the risk associated with the time to first readmission for patients who were readmitted within the homelessness and control groups. Sensitivity analyses were performed for patients with index hospitalization occurring during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place period between March 1, 2020, and December 1, 2020. This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board and adhered to the STROBE reporting guidelines.

Results

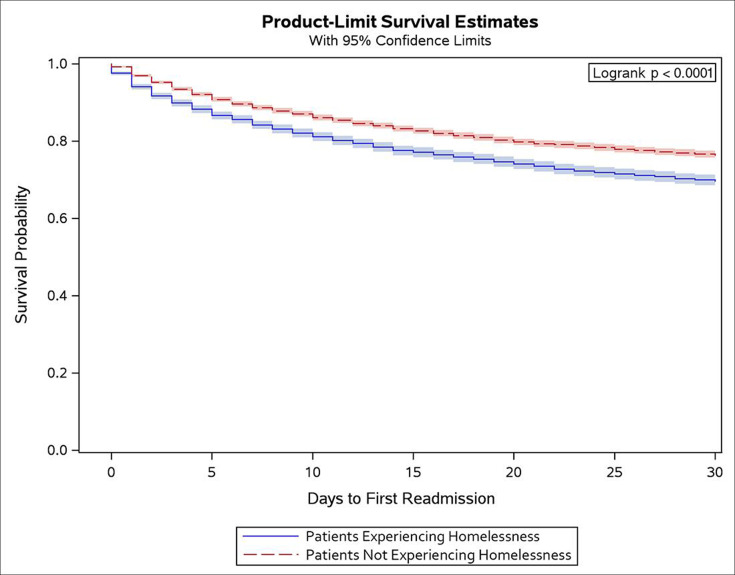

A total of 12,909 patients were included, with 4303 patients experiencing homelessness. Patients experiencing homelessness and the matched control group were relatively balanced across both demographics and medical diagnoses (Table 1). Supplemental table 1 shows the groups before the matching process. Patients experiencing homelessness had a higher rate of any 30-day readmissions, at 30.47% of the population, compared with 23.79% of the matched general population, which was largely driven by ED readmissions (Table 2). Patients experiencing homelessness had higher odds of having a readmission within 30 days of discharge (odds ratio [OR] = 1.47; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.33-1.63), and had higher odds of having both inpatient readmissions (OR =1.32; 95% CI = 1.14-1.54) and ED readmissions (OR = 1.49; CI = 1.35-1.66; Table 3). In addition, patients experiencing homelessness were more likely to have higher lengths of stay for their index hospitalization (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.14; 95% CI = 1.05-1.23; Table 3). Patients experiencing homelessness were also more likely to have shorter times to their first inpatient readmissions compared to the patients who were readmitted from the control group (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.32; 95% CI = 1.18-1.48; Figure 1). There was no difference in primary or secondary outcomes during the COVID-19 lockdown shelter-in-place period compared with the year before the start of the pandemic.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics of group experiencing homelessness and propensity score–matched control groupa

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 12,909) | Control (n = 8606) | Patients experiencing homelessness (n = 4303) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.1 (18.5) | 56.8 (19.0) | 54.5 (17.4) |

| Female | 4662 (36.1) | 3108 (36.1) | 1554 (36.1) |

| Race | |||

| Hispanic | 2070 (16.0) | 1380 (16.0) | 690 (16.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2643 (20.5) | 1762 (20.5) | 881 (20.5) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 120 (0.9) | 80 (0.9) | 40 (0.9) |

| Asian | 621 (4.8) | 414 (4.8) | 207 (4.8) |

| Indigenous | 132 (1.0) | 88 (1.0) | 44 (1.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 6813 (52.8) | 4542 (52.8) | 2271 (52.8) |

| Missing | 510 (4.0) | 340 (4.0) | 170 (4.0) |

| Anxiety | 3082 (23.9) | 2080 (24.2) | 1002 (23.3) |

| Asthma | 1982 (15.4) | 1342 (15.6) | 640 (14.9) |

| Intellectual disorder | 73 (0.6) | 45 (0.5) | 28 (0.7) |

| Alcohol abuse | 3475 (26.9) | 2320 (27.0) | 1155 (26.8) |

| Blood loss anemia | 388 (3.0) | 263 (3.1) | 125 (2.9) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4050 (31.4) | 2737 (31.8) | 1313 (30.5) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 4338 (33.6) | 2925 (34.0) | 1413 (32.8) |

| Coagulopathy | 1901 (14.7) | 1278 (14.9) | 623 (14.5) |

| Congestive heart failure | 2980 (23.1) | 2005 (23.3) | 975 (22.7) |

| Deficiency anemia | 1313 (10.2) | 856 (9.9) | 457 (10.6) |

| Depression | 3549 (27.5) | 2383 (27.7) | 1166 (27.1) |

| Diabetes, complicated | 2125 (16.5) | 1444 (16.8) | 681 (15.8) |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 3024 (23.4) | 2061 (23.9) | 963 (22.4) |

| Substance use disorder | 5931 (45.9) | 3973 (46.2) | 1958 (45.5) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 6083 (47.1) | 4110 (47.8) | 1973 (45.9) |

| HIV/AIDS | 239 (1.9) | 150 (1.7) | 89 (2.1) |

| Hypertension, complicated | 3439 (26.6) | 2345 (27.2) | 1094 (25.4) |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 6001 (46.5) | 4083 (47.4) | 1918 (44.6) |

| Hypothyroidism | 1218 (9.4) | 836 (9.7) | 382 (8.9) |

| Liver disease | 3268 (25.3) | 2201 (25.6) | 1067 (24.8) |

| Lymphoma | 88 (0.7) | 61 (0.7) | 27 (0.6) |

| Metastatic cancer | 418 (3.2) | 283 (3.3) | 135 (3.1) |

| Obesity | 2658 (20.6) | 1797 (20.9) | 861 (20.0) |

| Other neurologic disorders | 2780 (21.5) | 1870 (21.7) | 910 (21.1) |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 5739 (44.5) | 3895 (45.3) | 1844 (42.9) |

| Paralysis | 587 (4.5) | 408 (4.7) | 179 (4.2) |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 316 (2.4) | 209 (2.4) | 107 (2.5) |

| Psychoses | 1319 (10.2) | 826 (9.6) | 493 (11.5) |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 996 (7.7) | 671 (7.8) | 325 (7.6) |

| Renal failure | 2460 (19.1) | 1685 (19.6) | 775 (18.0) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen | 444 (3.4) | 310 (3.6) | 134 (3.1) |

| Tumor | 845 (6.5) | 567 (6.6) | 278 (6.5) |

| Valvular disease | 1245 (9.6) | 839 (9.7) | 406 (9.4) |

| Weight loss | 1494 (11.6) | 1002 (11.6) | 492 (11.4) |

All characteristics between the 2 groups were balanced.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2:

Hospital use outcomes in patients experiencing homelessness vs matched patients from the general population without documentation findings suggesting homelessness

| Outcome | Patients experiencing homelessness (n = 4303) | General population (n = 8606) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any 30-day readmission Count (%) |

1311 (30.47) | 2047 (23.79) | < 0.0001 a |

| Any 30-day ED readmission Count (%) |

1271 (29.54) | 1920 (22.31) | < 0.0001 a |

| Any 30-day inpatient readmission Count (%) |

472 (10.97) | 851 (9.89) | 0.0563a |

| Time to any readmission | 9.58 (8.51) | 10.39 (8.41) | 0.0003 b |

| Index hospitalization length Mean (SD) |

5.35 (9.52) | 4.76 (7.96) | < 0.0001 b |

Bolded values represent values significant at < 0.05.

Chi-square test p value.

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney p value.

ED, emergency department; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3:

Odds of hospital readmission and increased length of stay during the index hospitalization associated with patient housing characteristics, insurance coverage characteristics, and hospitalization during the COVID-19 lockdown

| Characteristic | Odds of any 30-day readmission including ED and inpatient stays | Odds of any 30-day ED readmission | Odds of any 30-day inpatient readmission | Odds of increased length of stay during index hospitalization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiencing homelessness | 1.47 | 1.33–1.63 | 1.49 | 1.35–1.66 | 1.32 | 1.14–1.54 | 1.14 | 1.05–1.23 |

| 1 change in patient address vs none | 1.28 | 1.12–1.47 | 1.31 | 1.14–1.51 | 0.97 | 0.79–1.20 | 0.94 | 0.87–1.01 |

| 2 changes in patient address vs none | 1.96 | 1.59–2.42 | 2.02 | 1.63–2.50 | 1.26 | 0.95–1.67 | 0.91 | 0.83–1.01 |

| 1–5 mo of enrollment in Kaiser Permanente Northern California vs none | 0.99 | 0.76–1.29 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.19 | 1.27 | 0.85–1.90 | 1.05 | 0.88–1.25 |

| 6–11 mo of enrollment in Kaiser Permanente Northern California vs none | 1.15 | 0.92–1.44 | 1.04 | 0.83–1.30 | 1.40 | 1.00–1.95 | 0.90 | 0.80–1.02 |

| Full enrollment in Kaiser Permanente Northern California for the year vs none | 1.28 | 1.12–1.46 | 1.21 | 1.06–1.39 | 1.6 | 1.33–1.97 | 0.98 | 0.90–1.07 |

| Hospitalization during COVID-19 lockdown vs prior | 0.89 | 0.80–0.99 | 0.88 | 0.79–0.98 | 0.97 | 0.83–1.12 | 0.94 | 0.89–1.00 |

Bolded values represent values significant at < 0.05.

ED, emergency department.

Figure 1:

Measures of association (odds ratios) for forms of hospital use for patients experiencing homelessness vs those who are not.

Any address change in the prior year compared with no address changes within the year prior to their index admission was associated with significantly increased odds for ED readmissions within 30 days [2+ address changes (OR = 2.02; 95% CI = 1.63-2.50); 1 address change (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.14-1.5)] but was not associated with any changes to inpatient admissions. Patients with address changes did not have a significantly increased length of hospital stay, but they did have a shorter time to any readmission compared to patients with no address changes [1 address change vs none (HR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.14-1.39); ≥ 2 address changes vs none (HR = 1.87; 95% CI = 1.63-2.15)].

Discussion

Documentation of housing status following SB 1152 can be used to study hospitalization among patients experiencing homelessness and can be useful in identifying patients who are at increased likelihood of frequent readmissions. In the study’s population, patients experiencing homelessness were seen to have higher rates of 30-day readmissions and longer lengths of stay. Patients experiencing homelessness were more likely to have both inpatient readmissions and ED presentations following a hospitalization, however the overall trend suggests that ED readmissions drive much of the observed difference. Patients experiencing homelessness were also more likely to have a shorter time to first readmission following discharge. A recent study showed increased identification of patients in 1 ED experiencing homelessness as a result of changes in SB 1152 documentation.13 However, this is the first study to show patterns of hospital and ED use across a large integrated health system after the implementation of SB 1152. Since SB 1152, there has been an increased interest in how the requirements of SB 1152 could improve post-discharge care for patients experiencing homelessness with the hope of reducing readmissions. However, results have been mixed in the limited recent evidence as there is a lack of comprehensive community availability of resources for these patients at the point of discharge.14

These results are consistent with prior evidence across the country that has shown higher rates of readmission following hospital discharge for populations experiencing homelessness.15,16 There have been limited data about hospital use by this population during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study did not find any changes in readmission rates during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

This study has limitations. The authors describe the patterns of hospital use following SB 1152 implementation, but this study is not designed to prove causality or identify any specific effects in hospital use patterns as a result of SB 1152. The use of specific documentation associated with SB 1152 may have introduced misclassification of homelessness status in this study. Due to variability in the documentation changes across Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the authors likely under-identified patients experiencing homelessness; thus, it is possible that some patients in the control group were experiencing homelessness. The authors expect that this misclassification of their exposure would have biased the results toward the null, in fact strengthening the conclusions of these findings. As the findings are within an integrated, capitated health care system, they may be less generalizable to other populations. However, the inclusion of patients who did not have Kaiser Permanente insurance and controlling for insurance status does suggest that the findings could be more generalizable. When controlling for length of enrollment in Kaiser Permanente insurance compared with not being Kaiser Permanente members, the authors see an increased chance of hospital use within their cohort for nonmembers, despite the data not capturing their use outside of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (Table 3). This study was not empowered to look at hospital-level differences in use due to the low numbers of patients experiencing homelessness among a few hospitals. As hospital readmissions and length of stay are affected by the cause of hospitalization, this study is limited in its ability to parse out the causes of readmissions based on the diagnosis of admission. The matching of patients based on their health conditions could control for part of this difference.

Difficulty with identifying the vulnerable population experiencing homelessness on a population health level has led to a lack of rich data regarding the health care use pattern of this population and difficulty with implementing health system–wide interventions.17 Understanding patterns of hospital use in this vulnerable group will help practitioners identify timely points of intervention for further social and health care support.

Conclusion

In California, EHR documentation changes associated with SB 1152 could be implemented to identify the population experiencing homelessness with frequent readmissions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank the members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, whose care is the guiding principle for this work and who were the source of the data for this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Somalee Banerjee, MD, MPH, and Julie Schmittdiel, PhD, developed the idea. Somalee Banerjee, Maher Yassin, MPH, Wendy T Dyer, MS, Tainayah W Thomas, PhD, MPH, Luis A Rodriguez, PhD, MPH, RD, and Julie Schmittdiel contributed to the design of the questions and to the writing of the paper. Somalee Banerjee, Maher Yassin, Wendy Dyer, and Julie Schmittdiel processed the data.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding: This study was funded by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefit Programs. Drs Rodriguez and Thomas received funding from The Permanente Medical Group Delivery Science Fellowship Program and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant T32DK11668401. Dr Schmittdiel received additional support from the NIDDK-funded Diabetes Research for Equity through Advanced Multilevel Science Center for Diabetes Translational Research (1P30 DK92924).

Data-Sharing Statement: The underlying data utilized in this study are HIPAA-protected and identifiable data cannot be shared.

References

- 1. Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):241–250. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Omerov P, Craftman ÅG, Mattsson E, Klarare A. Homeless persons’ experiences of health- and social care: A systematic integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(1):1–11. 10.1111/hsc.12857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koh KA, Racine M, Gaeta JM, et al. Health care spending and use among people experiencing unstable housing in the era of accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):214–223. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Treglia D, Johns EL, Schretzman M, et al. When crises converge: Hospital visits before and after shelter use among homeless New Yorkers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(9):1458–1467. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miyawaki A, Hasegawa K, Figueroa JF, Tsugawa Y. Hospital readmission and emergency department revisits of homeless patients treated at homeless-serving hospitals in the USA: Observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2560–2568. 10.1007/s11606-020-06029-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moulin A, Lopez-Gusman E. How a bill becomes a law, or how a truly terrible bill becomes less awful. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(4):549–551. 10.5811/westjem.2019.5.43666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Potter AJ, Wilking J, Nevarez H, Salinas S, Eisa R. Interventions for health: Why and how health care systems provide programs to benefit unhoused patients. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23(6):445–452. 10.1089/pop.2019.0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vickery KD, Shippee ND, Bodurtha P, et al. Identifying homeless medicaid enrollees using enrollment addresses. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1992–2004. 10.1111/1475-6773.12738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subedi K, Acharya B, Ghimire S. Factors associated with hospital readmission among patients experiencing homelessness. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(3):362–370. 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez LA, Thomas TW, Finertie H, et al. Identifying predictors of homelessness among adults in a large integrated health system in Northern California. Perm J. 2023;27(1):56–71. 10.7812/TPP/22.096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eakin M, Singleterry V, Wang E, Brown I, Saynina O, Walker R. Effects of California’s new patient homelessness screening and discharge care law in an emergency department. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35534. 10.7759/cureus.35534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taira BR, Kim H, Prodigue KT, et al. A mixed methods evaluation of interventions to meet the requirements of California Senate Bill 1152 in the emergency departments of a public hospital system. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):464–491. 10.1111/1468-0009.12563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Racine MW, Munson D, Gaeta JM, Baggett TP. Thirty-day hospital readmission among homeless individuals with medicaid in Massachusetts. Med Care. 2020;58(1):27–32. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khatana SAM, Wadhera RK, Choi E, et al. Association of homelessness with hospital readmissions-an analysis of three large states. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2576–2583. 10.1007/s11606-020-05946-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gordon SJ, Grimmer K, Bradley A, et al. Health assessments and screening tools for adults experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1).994. 10.1186/s12889-019-7234-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.