Abstract

Atherosclerosis constitutes a proverbial pathogenic mechanism for cardio-cerebrovascular disease that accounts for the most common cause of disability and morbidity for human health worldwide. Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are the key contributors to the progression of atherosclerosis. Glutaredoxin 2 (GLRX2) is abundantly existed in various tissues and possesses a range of pleiotropic efficacy including anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory responses. However, its role in atherosclerosis is still undefined. Here, down-regulation of GLRX2 was validated in lipopolysaccha (LPS)-induced vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). Moreover, elevation of GLRX2 reversed the inhibition of cell viability in LPS-treated HUVECs and decreased LPS-induced increases in cell apoptosis and caspase-3 activity. Additionally, enhancement of GLRX2 expression antagonized oxidative stress in HUVECs under LPS exposure by inhibiting ROS, lactate dehydrogenase and malondialdehyde production and increased activity of anti-oxidative stress superoxide dismutase. Notably, GLRX2 abrogated LPS-evoked transcripts and releases of pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β), chemokine MCP-1 and adhesion molecule ICAM-1 expression. Furthermore, the activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling was demonstrated in LPS-stimulated HUVECs. Importantly, blockage of the Nrf2 pathway counteracted the protective roles of GLRX2 in LPS-triggered endothelial cell injury, oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Thus, these data reveal that GLRX2 may alleviate the progression of atherosclerosis by regulating vascular endothelial dysfunction and inflammation via the activation of the Nrf2 signaling, supporting a promising therapeutic approach for atherosclerosis and its complications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10616-023-00606-x.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Vascular endothelial cell, LPS, Oxidative injury, Inflammation

Introduction

Atherosclerosis ranks as a multifocal, smoldering, chronic immunoinflammatory disease and constitutes a proverbial underlying cause of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (Libby 2021). Epidemiological studies highlight that the risk of developing atherosclerosis is no longer concentrated in Western countries, but is also widespread in Eastern Europe and Asia (Herrington et al. 2016). Currently, atherosclerosis remains a frequent cause of death worldwide because of high morbidity of its complications, such as myocardial infarctions, ischemic stroke, and disabling peripheral arterial disease (Libby 2021). In 2017, cardiovascular disease has accounted for approximately 30% of deaths worldwide (Benjamin et al. 2017). Atherosclerosis majorly prevails in older individuals; however, increasingly prevalent is also validated in younger people, more women and individuals from a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds (Bergstrom et al. 2021; Libby 2021). Though abundant studies have tried to discern the onset of arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis remains a great challenge for global health (Song et al. 2020).

Chronic inflammation is a known hallmark of atherosclerosis and exerts critical roles in the onset and progression of atherosclerosis and its complications (Chrysohoou et al. 2018; Hansson et al. 2006). It is widely held that the long-term inflammatory state in blood vessel walls will incur an increase in endothelial cell permeability and vascular endothelial dysfunction (Chrysohoou et al. 2018; Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardena 2016). Endothelium usually exerts indispensable roles in maintaining vascular homeostasis including permeability, integrity and adhesiveness. Under persistent exposure to inflammatory environment, endothelial cells, the major components of the endothelium, will injure and release abundant pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules, thereby exacerbating the progression of atherosclerosis (Chrysohoou et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2017). Actually, dysfunction of vascular endothelium presents with chronic inflammatory response, heightened oxidative stress, hyper-permeability and leukocyte infiltration (Lahera et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2021). Therefore, targeting vascular endothelial injury and inflammatory response represents a promising approach against atherosclerosis (Duan et al. 2021; Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardena 2016; Lahera et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2017).

Glutaredoxins are glutathione-dependent oxidoreductases that are widely present in almost all living organisms. Glutaredoxin-1 is one of the well-studied family members and involves in the progression of ischemic injury, inflammation and atherosclerosis (Burns et al. 2020). As a newly identified member of glutaredoxin family, glutaredoxin 2 (GLRX2) is abundantly existed in various tissues and exerts key roles in regulating redox homeostasis. Accumulated preclinical evidence supports the protective efficacy of GLRX2 in multiple injury processes (Wen et al. 2020). For instance, overexpression of GLRX2 alleviates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis and oxidative injury in neurons, indicating the important roles in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury (Diotte et al. 2009; Wen et al. 2020). Moreover, a recent study confirms the benefic effects of GLRX2 elevation against doxorubicin-evoked cardiac injury (Diotte et al. 2009). Noticeably, increasing evidence supports the anti-inflammatory effects of GLRX2 on various pathogenic processes (Li et al. 2021; Wohua and Weiming 2019). A deficiency of GLRX2 exacerbates high-fat diet-induced inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in brain injury (Wohua and Weiming 2019). Additionally, GLRX2 reduces hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury, inflammation (Li et al. 2021) and asthma-like acute airway inflammation in mice (Hanschmann et al. 2020). Up to now, the roles of GLRX2 in atherosclerosis remain undefined. In the current study, we investigated the effects of GLRX2 in lipopolysaccha (LPS)-induced oxidative injury and inflammatory response in vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). The underlying molecular mechanism was also explored.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM) medium containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2.5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). For cell stimulation, HUVECs were exposed to 1 µg/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for the indicated times. All cells were housed at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2.

Construction of recombinant expression plasmid

Total RNA from HUVECs under various treatments was prepared using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen). Subsequently, 2 µg RNA samples were used as the template to prepare the first-strand cDNA according to the protocols from the commercial cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Then, the GLRX2 cDNA was prepared by PCR amplification according to GLRX2 gene sequence (GenBank: AF290514.1) and using the specific primers (sense, 5′-CCAGAGGCGGGGCTCGGATGA-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTTATTAGTATAAACATCACTGA-3′). Then, the prepared GLRX2 cDNA was cloned to the expression plasmids of pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen) to prepare the recombinant vector of pcDNA-GLRX2.

Cell transfection

Before the transfection, cells were plated in 6-well plates and allowed to grow to 60-80% confluence. Then, the recombinant pcDNA-GLRX2, empty vector, and siRNAs targeting nuclear factor (erythroid 2)-related factor 2 (Nrf2), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), or scramble control (si-NC) were transfected into HUVECs using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (5 µL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The specific siRNA sequences were obtained from Invitrogen. All procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Forty-eight hours later, cells were harvested and the final transfected efficiency was evaluated by qRT-PCR and western assay.

Cell counting kit (CCK)-8 assay for cell viability detection

HUVECs were transfected with si-Nrf2 or si-NC under LPS exposure. Then, cell viability was monitored by the CCK-8 assay (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). After the indicated treatments, cells were incubated with 10 µl of CCK-8 solution for 4 h according to the instructions of CCK-8 Kits. Then, a measurement wavelength of 450 nm was performed to assess cell viability.

RNA extract and qRT-PCR assay

The transcripts levels of GLRX2, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA were quantified using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa) on an ABI (QuantStudio 6) instrument (Applied Biosystems). All genes were normalized to GAPDH and analyzed using the formula of 2−ΔΔCt. The specific primer sequences were used as follows: GLRX2 (sense, 5′- GGTCTCGACCAATTGCCTAAT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-AGTGGTGCCTCAGATGTTTC-3′), IL-6 (sense, 5′-GAGAGCCAGAACACAGAAGAA-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTGAGTTTCCTCTGACTCCATC-3′), TNF-α (sense, 5′-TTCTGCCTGCTGCACTTT − 3′; anti-sense, 5′-CCTCTCTTGCGTCTCTCATTTC-3′), IL-1β (sense, 5′- CTCTCACCTCTCCTACTCACTT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-TCAGAATGTGGGAGCGAATG-3′), ICAM-1 (sense, 5′- GTAGCAGCCGCAGTCATAAT-3′; anti-sense, 5′- GGGCCTGTTGTAGTCTGTATTT-3′), MCP-1 (sense, 5′-TCATAGCAGCCACCTTCATTC-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTCTGCACTGAGATCTTCCTATTG-3′) and GAPDH (sense, 5′-CAAGAGCACAAGAGGAAGAGAG-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTACATGGCAACTGTGAGGAG-3′).

Western blotting analysis

After the harvesting from cells under the indicated treatments, the RIPA lysis buffer was added to extract the total protein. Following the quantification using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), approximately 30 µg of protein was subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE gels to separate protein, and then was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After that, 5% no-fat milk was used to interdict the non-specific binding in membranes. The primary antibodies were added to membranes at 4 °C overnight, including anti-human GLRX2 (1:2000; ab191292), Nrf2 (1:1000; ab137550) and HO-1 (1:2000; ab189491) (all from Abcam, Cambridge, UK, USA). After rinsing with TBST buffer, membranes were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the binding proteins were visualized using the ECL reagent (Invitrogen), followed by the quantification by the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, USA).

Cell apoptosis assay by flow cytometer

HUVECs under the indicated conditions were collected, centrifuged, and re-suspended in Annexin V-FITC binding buffer (195 µl). Then, cells were further incubated with 10 µl Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI (Beyotime) avoiding light. All protocols were conducted in line with the instructions of the Annexin V Apoptosis Kits (Beyotime). Ultimately, all specimens were harvested at 15 min-post incubation and analyzed by a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) with CellQuest software.

Caspase-3 activity

To detect the activity of caspase-3, HUVECs were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer. Then, a commercial Caspase-3 Activity Detection Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) was used to evaluate the activity of caspase-3 in cell lysates. During this process, 10 µl of the specific caspase-3 substrates, Ac-DEVD-pNA, was added to lysates for 4 h at 37 °C. Finally, the absorbance at 405 nm was captured.

Detection of intracellular ROS levels

For the detection of ROS levels, cells were collected and then maintained in a serum-free DMEM medium supplemented with 10 µM DCFH-DA (Beyotime) for 0.5 h under dark to yield fluorescent DCF. The final fluorescence intensity was evaluated by a fluorescence microscope and a fluorometric microplate reader at the excitation wavelength of 490 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Assay of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) contents

The contents of LDH, MDA and SOD in HUVECs under various conditions were measured using the commercial Detection Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). For the detection of LDH and SOD, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured. To analyze the contents of MDA, the absorbance at 532 nm was captured. All detailed protocols were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ELISA assay

The levels of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and MCP-1) in supernatants were detected using the commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Detailed steps were performed about the manufacturers’ recommendations. All specimens were ultimately determined using a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio Rad, Hercules CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data were prepared from at least three individual experiments and shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were analyzed via two-sided Student’s t test for two groups or ANOVA with post-hoc SNK test for multiple groups. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

Results

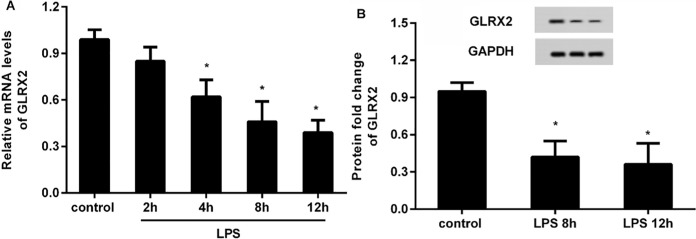

Expression of GLRX2 decrease in vascular endothelial cells in response to LPS stimulation

To elucidate the function of GLRX2 in atherosclerosis in vitro, we first detected the expression of GLRX2 in HUVECs under LPS simulation. qRT-PCR assay revealed that the transcripts of GLRX2 decreased significantly after 1 µg/ml of LPS treatment for 4 h, 8 and 12 h relative to the control group, indicating the time-dependent decrease of GLRX2 mRNA. Notably, no obvious difference in GLRX2 transcript was observed between 8 and 12 h-treated groups (Fig. 1A). Therefore, LPS exposure for 8 h was chosen for the following experiments. Moreover, the protein expression of GLRX2 was reduced in HUVECs in response to LPS stimulation for 8 h (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Expression of GLRX2 was reduced in endothelial cells under LPS exposure. A HUVECs were exposed to 1 µg/ml LPS at various times. Then, the mRNA levels of GLRX2 were analyzed by qRT-PCR. B The protein expression of GLRX2 was determined in HUVECs at 8 h-post incubation with LPS. *P < 0.05 vs. control group

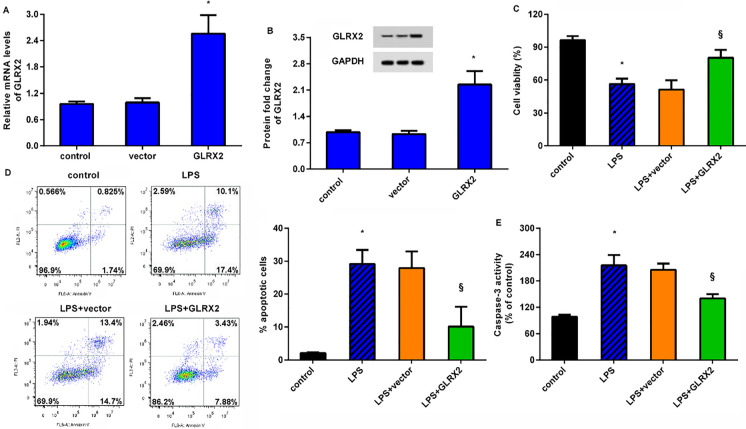

Enhancement of GLRX2 ameliorates LPS-induced inhibition of cell viability

As shown in Fig. 2A, transfection with recombinant pcDNA-GLRX2 plasmids dramatically induced a 2.56-fold increase in GLRX2 mRNA relative to control groups. Concomitantly, the protein expression of GLRX2 was also enhanced after the recombinant plasmid transfection (Fig. 2B). Importantly, LPS exposure restrained HUVEC viability, compared with the control groups (Fig. 2C). Noticeably, overexpression of GLRX2 reversed the inhibitory effects of LPS on cell viability (Fig. 2C). Additionally, HUVECs under LPS conditions exhibited higher cell apoptosis (Fig. 2D) and caspase-3 activity (Fig. 2E) than that in control groups. However, GLRX2 elevation antagonized LPS-evoked above increases in cell apoptosis and caspase-3 activity.

Fig. 2.

GLRX2 up-regulation alleviates LPS-evoked suppression of endothelial cell viability. A HUVECs were transfected with GLRX2 plasmids or empty plasmids. Then, qRT-PCR was carried out to analyze the transcript levels of GLRX2. B The protein expression of GLRX2 was detected. C–E Cells were treated with GLRX2 plasmid transfection and LPS exposure. Then, cell viability (C), apoptosis (D) and caspase-3 activity were measured by CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry and commercial kits, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group

GLRX2 up-regulation restrains oxidative injury of HUVECs under LPS exposure

Endothelial cell oxidative injury constitutes a major contribution to the development of atherosclerosis (Xu et al. 2021; Yao et al. 2019). We therefore investigated the roles of GLRX2 in LPS-induced oxidative injury in HUVECs. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, LPS exposure enhanced ROS production, which was inhibited after GLRX2 overexpression. At the same time, the increased contents of LDH (Fig. 3B) and MDA (Fig. 3C) were validated in LPS-treated HUVECs; however, GLRX2 elevation abrogated these increases. Additionally, the down-regulation of SOD content under LPS simulation was overturned following GLRX2 overexpression (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

LPS-induced oxidative injury was abrogated after GLRX2 overexpression. HUVECs transfected with GLRX2 plasmids were simulated with LPS. Then, the contents of ROS (A), LDH (B), MDA (C) and SOD activity (D) were determined. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group

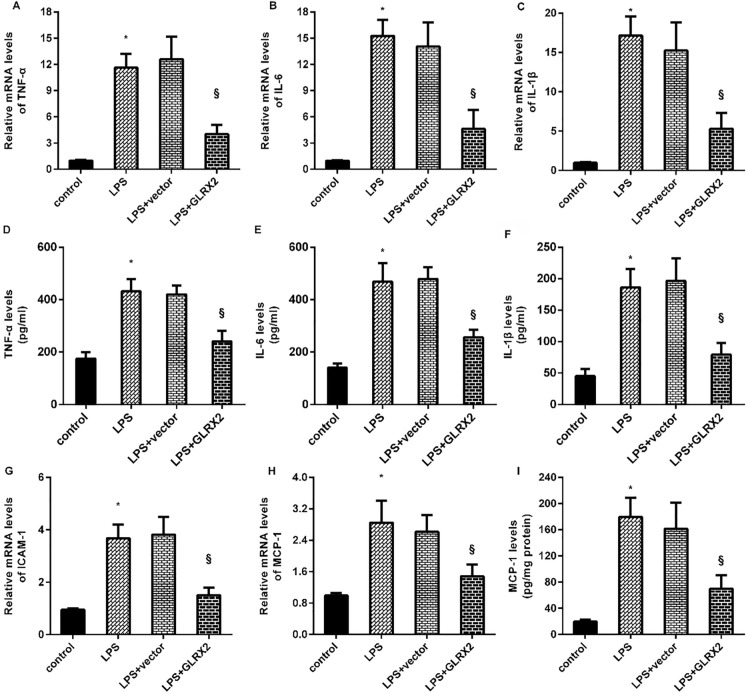

Overexpression of GLRX2 mitigates inflammatory response in LPS-treated HUVECs

Next, we elucidated the roles of GLRX2 in LPS-triggered inflammatory response in HUVECs and found that exposure to LPS enhanced the transcripts of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α (Fig. 4A), IL-6 (Fig. 4B), and IL-1β (Fig. 4C). However, enhancement of GLRX2 attenuated LPS-induced above increases. Moreover, GLRX2 overexpression inhibited LPS-induced releases of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Fig. 4D), IL-6 (Fig. 4E), and IL-1β (Fig. 4F) from HUVECs. Concomitantly, stimulation with LPS elevated the mRNA levels of adhesion cytokine ICAM1 (Fig. 4G) and chemokine MCP-1 (Fig. 4H), which were inhibited after GLRX2 elevation. The increased release of MCP-1 from cells in response to LPS was also ameliorated following GLRX2 plasmid transfection (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4.

The pro-inflammatory response was inhibited in LPS-treated endothelial cells. A–C Following the exposure under LPS and GLRX2 overexpression, the transcripts of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), and IL-1β (C) were analyzed by qRT-PCR. D–F The releases of these cytokines from endothelial cells were determined by ELISA kits. Then, the mRNA levels of adhesion cytokine ICAM1 (G) and the content of chemokine MCP-1 (H) were evaluated. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group

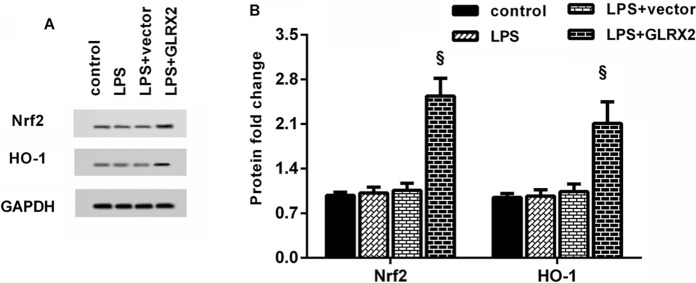

GLRX2 elevation activates the Nrf2/HO-1 axis in HUVECs under LPS conditions

A large body of evidence confirms the key roles of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in the progression of atherosclerosis (Zhang et al. 2021). As present in Fig. 5A and B, GLRX2 overexpression enhanced the protein expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 relative to the LPS-treated cells. Thus, these data indicate the activation of Nrf2/HO-1 axis in GLRX2-overexpressed HUVECs under LPS exposure.

Fig. 5.

The pathway of NRf2/HO-1 was activated in LPS-stimulated HUVECs after GLRX2 overexpression. A Following the treatment with GLRX2 vector and LPS, the protein expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 was measured. B The bands were quantified using the Image J software. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group

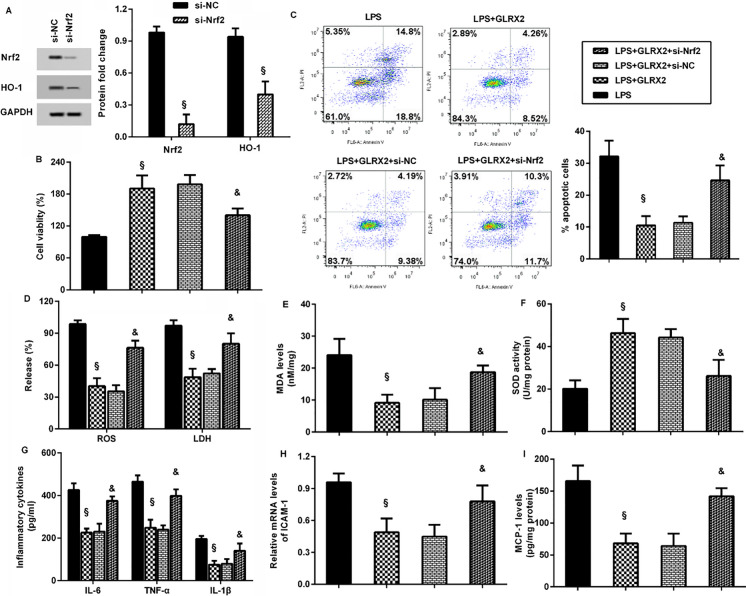

Targeting the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling mutes the protective efficacy of GLRX2 against LPS-induced endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory response

Before further discern of the involvement of Nrf2 signaling in LPS-evoked endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, we silenced this pathway by si-Nrf2 transfection (Fig. 6A). Intriguingly, GLRX2 elevation attenuated LPS-induced inhibition in cell viability (Fig. 6B) and LPS-evoked increases in cell apoptosis (Fig. 6C), which were reversed when blockage of the Nrf2 signaling. Moreover, overexpression of GLRX2 abrogated the increases in ROS, LDH levels (Fig. 6D) and MDA levels (Fig. 6E) and decreases in SOD activity (Fig. 6F). However, blocking the Nrf2 axis muted the protective efficacy of GLRX2 against LPS-induced oxidative injury. In addition, GLRX2-mediated suppression in pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Fig. 6G), ICAM-1 transcript (Fig. 6H) and MCP-1 release (Fig. 6I) in LPS-treated cells were ameliorated after si-Nrf2 transfection.

Fig. 6.

GLRX2 regulated LPS-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammatory response via the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis. A The effects of si-Nrf2 transfection were assessed by western blotting. B–F Cells were transfected with si-NRf2 or GLRX2 vector, before LPS conditions. Then, cell viability (B), apoptosis (C), the levels of ROS and LDH (D), MDA (E) and SOD (F) were detected. The contents of pro-inflammatory cytokines (G) and pro-inflammatory mediators (H, I) were also tested. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group. &P < 0.05 vs. LPS and GLRX2 group

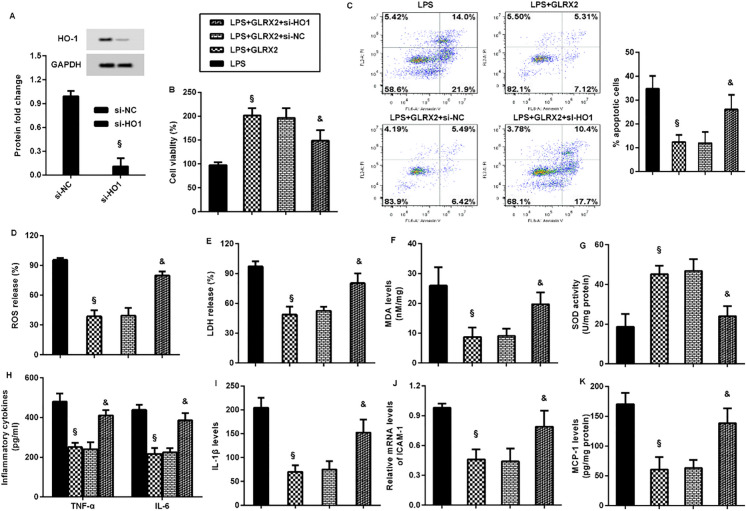

To further whether HO-1 involves in GLRX2-mediated protection against LPS-induced endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory response, the expression of HO-1 was silenced by si-HO-1 transfection (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, GLRX2-mediated increase in cell viability (Fig. 7B) and decrease in cell apoptosis (Fig. 7C) were reversed after HO-1 inhibition in LPS-treated cells. The suppressive effects of GLRX2 overexpression on LPS-induced ROS (Fig. 7D), LDH (Fig. 7E) and MDA (Fig. 7F) levels were offset by HO-1 knockdown. Moreover, GLRX2-mediated increases in SOD activity was inhibited following si-HO-1 transfection into LPS-treated cells (Fig. 7G). Notably, overexpression of GLRX2 restrained LPS-induced increases in TNF-α, IL-6 (Fig. 7H), IL-1β levels (Fig. 7I), ICAM-1 transcript (Fig. 7J) and MCP-1 production (Fig. 7K), which were reversed after HO-1 down-regulation.

Fig. 7.

HO-1 was involved in the protective efficacy of GLRX2 on LPS-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammatory response. A The effects of si-HO-1 transfection were analyzed by western blotting. B–G Cells were treated with si-HO-1, GLRX2 vector and LPS. Then, the effects on cell viability (B), apoptosis (C), ROS (D) and LDH release (E), MDA (F) and SOD (G) levels were subsequently determined. H–K Then, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6 (H), IL-1β (I), ICAM-1 transcript (J), and MCP-1 production (K) were also evaluated. §P < 0.05 vs. LPS group. &P < 0.05 vs. LPS and GLRX2 group

Discussion

Cardio-cerebrovascular disease constitutes the most common cause of disability and morbidity resulting from atherosclerosis. Long-term inflammatory environment results in vascular endothelial dysfunctions that will further aggravate the progression of atherosclerosis (Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardena 2016; Horio et al. 2014; Lahera et al. 2007). LPS is a gram-negative bacterial endotoxin and is usually used as a simulator to investigate the underlying mechanism of atherosclerosis in vitro (Chang et al. 2021; Li et al. 2017; Meng et al. 2021). In the present study, we corroborated the down-regulation of GLRX2 in LPS-treated HUVECs, indicating the potential roles of GLRX2 in the progression of atherosclerosis.

The dysfunction within endothelium ranks as the critical early contributor in the initiation of atherosclerosis due to the disruption of vascular homeostasis (Xu et al. 2021). As the major components of endothelium, vascular endothelial cells form the lining of blood vessels between plasma and vascular tissue and are important for maintaining vascular function. Occurrence of oxidative injury in vascular endothelial cells under the chronic inflammatory environment will weaken vascular barrier function and increases the possibility of lipids and leukocyte deposit in the intima of blood vessels, ultimately aggravating atherosclerotic plaque formation and instability (Xu et al. 2021; Yao et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2021). Currently, protecting endothelial cells from oxidative stress injury is a promising approach for the treatment of atherosclerosis (Liang et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021). To elucidate the possibility of GLRX2 as a therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis, this study elaborated on its function in LPS-evoked oxidative injury. As expected, the elevation of GLRX2 restrained LPS-induced oxidative stress by decreasing ROS, LDH and MDA levels and increasing anti-oxidative stress SOD activity. Moreover, GLRX2 overexpression antagonized the inhibitory efficacy of LPS in HUVEC viability and apoptosis, indicating the anti-oxidative injury roles of GLRX2 in LPS-stimulated HUVECs. A previous study substantiated that knockdown of GLRX2 increased the sensitivity of lens epithelial cells to oxidative stress (Wu et al. 2011). Moreover, GLRX2 up-regulation protected against oxygen-glucose deprivation-reoxygenation-induced oxidative injury in neurons, supporting a promising approach against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury (Wen et al. 2020). Similarly, overexpression of GLRX2 alleviates hypoxia/reoxygenation-evoked oxidative stress damage in cardiomyocytes (Li et al. 2021).

Inflammatory response orchestrates each stage of atherosclerotic plaques (Hansson et al. 2006). Multiple pathogenic conditions (e.g. Inflammation) will stimulate pro-inflammatory endothelial activation to release abundant pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules to evoke vascular endothelium inflammation. Accumulating evidence confirms that endothelial inflammation is a key contributor to the progression of atherosclerosis (Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardena 2016; Horio et al. 2014; Jian et al. 2020; Li et al. 2017). Similar to previous findings (Chang et al. 2021; Li et al. 2017), this study substantiated that exposure to LPS induced pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β), chemokine MCP-1 and adhesion molecule ICAM-1 expression. Analogously, GLRX2 elevation protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-evoked inflammation in cardiomyocytes (Li et al. 2021). It is believed that abundant pro-inflammatory cytokines will aggravate inflammation in atherosclerosis, while chemokine and adhesion molecules contribute to monocyte recruitment and leukocyte accumulation that accelerates the development of atherosclerosis (Hansson et al. 2006; Lahera et al. 2007). Therefore, these data suggest that GLRX2 may ameliorate the progression of atherosclerosis by affecting LPS-evoked endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in vascular endothelial cells.

Noticeably, the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis was observed in LPS-simulated vascular endothelial cells. The Nrf2/HO-1 signaling is a known adaptive defense mechanism and its activation exerts a range of pleiotropic effects, such as anti-oxidative stress, anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammatory response. Intriguingly, emerging evidence supports that the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is associated with the development of atherosclerosis (Fiorelli et al. 2019; He et al. 2021). For example, activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling protects vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress, indicating the benefic efficacy in the treatment of atherosclerosis (Zhang et al. 2021). Furthermore, activating the Nrf2 pathway attenuates endothelial inflammation and the subsequent development of smoking-induced atherosclerosis (Zhao et al. 2021). Of note, the present data confirmed that blocking the Nrf2 signaling reversed the protective effects of GLRX2 on LPS-evoked endothelial oxidative injury and inflammatory response. Thus, the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway may account for GLRX2-mediated endothelial dysfunction under LPS exposure.

Conclusions

The current data revealed the down-regulation of GLRX2 in LPS-simulated vascular endothelial cells. Importantly, GLRX2 enhancement suppressed LPS-induced endothelial cell oxidative stress injury and inflammation via the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. Thus, these findings highlight that GLRX2 may be involved in the progression of atherosclerosis by regulating endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, indicating a promising therapeutic target for atherosclerosis-evoked cardio-cerebrovascular diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 10 (JPG 168.9 kb)

Supplementary material 11 (JPG 174.4 kb)

Acknowledgements

No.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing—original draft. JG: Formal analysis; Software; Data curation, Validation, review & editing. QW: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Formal analysis; Resources; Software; Validation; Writing—review & editing. NW: Data curation; Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis; Validation; Resources. LZ: Data curation; Software; Methodology; Formal analysis; Validation. ZW: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Validation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom G, Persson M, Adiels M, et al. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis in the general population. Circulation. 2021;144:916–929. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M, Rizvi SHM, Tsukahara Y, et al. Role of glutaredoxin-1 and glutathionylation in cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6803. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X, Zhang T, Liu D, et al. Puerarin attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory responses and oxidative stress injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells through mitochondrial quality control. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:6659240. doi: 10.1155/2021/6659240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Chrysohoou C, Kollia N, Tousoulis D. The link between depression and atherosclerosis through the pathways of inflammation and endothelium dysfunction. Maturitas. 2018;109:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diotte NM, Xiong Y, Gao J, Chua BH, Ho YS. Attenuation of doxorubicin-induced cardiac injury by mitochondrial glutaredoxin 2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Zhang Q, Liu J, Li R, Wang D, Peng W, Wu C. Suppression of apoptosis in vascular endothelial cell, the promising way for natural medicines to treat atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Res. 2021;168:105599. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorelli S, Porro B, Cosentino N, et al. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and human atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability: an in vitro and in vivo study. Cells. 2019 doi: 10.3390/cells8040356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone MA, Jr, Garcia-Cardena G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:620–636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanschmann EM, Berndt C, Hecker C, Garn H, Bertrams W, Lillig CH, Hudemann C. Glutaredoxin 2 reduces asthma-like acute airway inflammation in mice. Front Immunol. 2020;11:561724. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.561724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK, Robertson AK, Soderberg-Naucler C. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:297–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Yang G, Sun L, et al. SIRT6 inhibits inflammatory response through regulation of NRF2 in vascular endothelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99:107926. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington W, Lacey B, Sherliker P, Armitage J, Lewington S. Epidemiology of atherosclerosis and the potential to reduce the global burden of atherothrombotic disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:535–546. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio E, Kadomatsu T, Miyata K, et al. Role of endothelial cell-derived angptl2 in vascular inflammation leading to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:790–800. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian D, Wang Y, Jian L, et al. METTL14 aggravates endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis by increasing FOXO1 N6-methyladeosine modifications. Theranostics. 2020;10:8939–8956. doi: 10.7150/thno.45178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahera V, Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Miana M, de Heras N, Cachofeiro V, Luno J. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis: beneficial effects of statins. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:243–248. doi: 10.2174/092986707779313381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Xin H, Shi Y, Mu J. Glutaredoxin 2 protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury by suppressing apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation via enhancing Nrf2 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;94:107428. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Zhang GY, He JP, Zhang DD, Kong XX, Yuan HM, Chen FL. Ufm1 inhibits LPS-induced endothelial cell inflammatory responses through the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:1119–1126. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Zhang J, Ning R, et al. The critical role of endothelial function in fine particulate matter-induced atherosclerosis. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17:61. doi: 10.1186/s12989-020-00391-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2021;592:524–533. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Fan Y, Qiao C, et al. TFEB inhibits endothelial cell inflammation and reduces atherosclerosis. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaah4214. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aah4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q, Pu L, Lu Q, Wang B, Li S, Liu B, Li F. Morin hydrate inhibits atherosclerosis and LPS-induced endothelial cells inflammatory responses by modulating the NFkappaB signaling-mediated autophagy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;100:108096. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, et al. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e721–e729. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Li X, Zheng S, Xiao Y. Upregulation of glutaredoxin 2 alleviates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis and ROS production in neurons by enhancing Nrf2 signaling via modulation of GSK-3beta. Brain Res. 2020;1745:146946. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohua Z, Weiming X. Glutaredoxin 2 (GRX2) deficiency exacerbates high fat diet (HFD)-induced insulin resistance, inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in brain injury: a mechanism involving GSK-3beta. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:108940. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Lin L, Giblin F, Ho YS, Lou MF. Glutaredoxin 2 knockout increases sensitivity to oxidative stress in mouse lens epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:2108–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: from mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:924–967. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.120.000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G, Qi J, Zhang Z, et al. Endothelial cell injury is involved in atherosclerosis and lupus symptoms in gld.apoE(-) (/) (-) mice. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:488–496. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Liu J, Duan H, Li R, Peng W, Wu C. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: an important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J Adv Res. 2021;34:43–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang X, Zhang R, et al. Melatonin attenuates smoking-induced atherosclerosis by activating the Nrf2 pathway via NLRP3 inflammasomes in endothelial cells. Aging. 2021;13:11363–11380. doi: 10.18632/aging.202829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 10 (JPG 168.9 kb)

Supplementary material 11 (JPG 174.4 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.