Abstract

High concentrations of cobalt chloride (CoCl2) can induce the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) in various tumors, which can produce daughter cells with strong proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities via asymmetric division. To study the role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α in the formation of PGCCs, colon cancer cell lines Hct116 and LoVo were used as experimental subjects. Western blotting, nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction and immunocytochemical experiments were used to compare the changes in the expression and subcellular localization of HIF1α, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4 (PIAS4) and von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor (VHL) after treatment with CoCl2. The SUMOylation of HIFα was verified by co-immunoprecipitation assay. After inhibiting HIF1α SUMOylation, the changes in proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of Hct116 and LoVo were compared by plate colony formation, wound healing and Transwell migration and invasion. In addition, lysine sites that led to SUMOylation of HIF1α were identified through site mutation experiments. The results showed that CoCl2 can induce the formation of PGCCs with the expression level of HIF1α higher in treated cells than in control cells. HIF1α was primarily located in the cytoplasm of control cell. Following CoCl2 treatment, the subcellular localization of HIF1α was primarily in the nuclei of PGCCs with daughter cells (PDCs). After treatment with SUMOylation inhibitors, the nuclear HIF1α expression in PDCs decreased. Furthermore, their proliferation, migration and invasion abilities also decreased. After inhibiting the expression of MITF, the expression of HIF1α decreased. MITF can regulate HIF1α SUMOylation. Expression and subcellular localization of VHL and HIF1α did not change following PIAS4 knockdown. SUMOylation of HIF1α occurs at the amino acid sites K391 and K477 in PDCs. After mutation of the two sites, nuclear expression of HIF1α in PDCs was reduced, along with a significant reduction in the proliferation, migration and invasion abilities. In conclusion, the post-translation modification regulated the subcellular location of HIF1α and the nuclear expression of HIF1α promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of PDCs. MITF could regulate the transcription and protein levels of HIF1α and participate in the regulation of HIF1α SUMOylation.

Keywords: polyploid giant cancer cells, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, SUMOylation, colorectal cancer, proliferation, migration and invasion

Introduction

Our previous studies confirmed that cobalt chloride (CoCl2), chemical reagents, radiotherapy and Chinese herbal medicines can induce the formation of polyploid giant tumor cells (PGCCs) by internal replication or cell fusion (1–3). PGCCs are a subpopulation of cancer cells that contribute to solid tumor heterogeneity. The size of PGCCs is at least three times larger than that of regular-sized diploid cancer cells and PGCCs are multinucleated or have giant nuclei. PGCCs can produce daughter cells with high proliferation, migration and invasion abilities via asymmetric division (budding, splitting and bursting). These daughter cells have strong proliferation, infiltration and migration abilities (3,4). PGCCs have been observed in a number of malignant tumors such as breast (5), ovarian (6,7), colorectal (CRC) (4), non-small cell lung (8) and prostate cancers (9). Clinically, PGCCs have been more frequently observed in high-grade malignancies and metastatic foci than in low-grade tumors and primary sites. For the same patients, the number of PGCCs in the recurrent cancer was higher than that in the original cancer. The number of PGCCs is associated with a poor prognosis and metastatic recurrence in patients with malignant tumors (4).

Hypoxia is important in the progression of malignant tumors and is associated with the formation and maintenance of cancer stem cells (10,11). CoCl2 is a hypoxia mimic that stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF1α). HIF1α is a key factor activated in response to hypoxia and mediates the transcriptional response of local hypoxia in cancer and promotes tumor progression by altering cellular metabolism (12) and stimulating angiogenesis (13). Our previous results confirmed that HIF1α is significantly upregulated in PGCCs and their daughter cells (PDCs) (14). Under conditions of normal oxygen saturation, HIF1α is rapidly degraded by ubiquitin protease hydrolysis complex after translation, resulting in a low HIF1 expression level (15). However, in hypoxic microenvironments, HIF1α degradation is inhibited. HIF1α and HIF1β subunits combine to form complexes, which are then transferred to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of multiple genes and promote cell adaptation to hypoxia (16). SUMOylation is an important post-translational modification (PTM) characterized by the covalent and reversible binding of a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to the target protein, changing the subcellular location of the protein and maintaining its stability. SUMOylation plays an important role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastasis, therapeutic resistance and antitumor immune responses (17).

The present study demonstrated that SUMOylation could regulate the subcellular location of HIF1α and that nuclear expression of HIF1α promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion of PDCs. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), but not the protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4 (PIAS4), regulated the transcription and protein levels of HIF1α and participates in the regulation of HIF1α SUMOylation, which occurs at the K391 and K477 amino acid sites of HIF1α in PDCs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human colon cancer cells (Hct116 and LoVo) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The medium used was RPMI-1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, streptomycin and penicillin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) (complete medium). Cells were cultured in a constant-temperature incubator containing 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C.

Induction of the formation of PGCCs by CoCl2

When the cell confluency reached ~80%, 450 µM of CoCl2 was added to the flask. After treatment for 48 h (Hct116) and 36 h (LoVo), most regular-sized diploid cancer cells died and only a few cells with large nuclei (PGCCs) survived. The surviving cells exhibited multinucleated and mononuclear giant cell morphology and were highly resistant to hypoxia. Following treatment, the remaining cells were cultured in a complete medium without CoCl2. After ~15 days of recovery, the PGCCs produced daughter cells via asymmetric division. Following three repeated treatments, 30% of PGCCs and 70% of daughter cells appeared in the flask and the cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted by RIPA Buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentration was determined using Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein samples from control cells and PDCs were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel for electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 80 V. After separating the protein bands, the voltage was adjusted to 120 V. After the membrane transfer, 5% skimmed milk was added to the membrane for 1 h at room temperature. According to the molecular weight of proteins, PVDF membrane was cut prior to hybridization with different primary antibodies (detailed information regarding the antibodies is provided in Table I) at 4°C overnight. For the target proteins with similar molecular weight, a membrane regeneration solution was used to elute. After washing, the corresponding secondary antibodies were added and the mixture was shaken at room temperature for 1 h. After the ECL developer (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was added, a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was used for development and observation. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; 1.54D) was used to analyze and calculate the gray value of the corresponding strip and the expression index of the target protein. The experiment was independently repeated thrice.

Table I.

Detailed information of the antibodies utilized in this study.

| Antibody | Company (cat. no.) | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia inducible factor 1 α | Abcam (ab51608) | 1:1,000 (western blotting); 1:500 |

| (immunocytochemical); 1:50 | ||

| (co-immunoprecipitation) | ||

| Microphthalmia-associated transcription | Proteintech Group, Inc. | 1:1,000 (western blotting); |

| factor | (13092-1-AP) | 1:1,000 (immunocytochemical) |

| von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor | Proteintech Group, Inc. | 1:1,000 (western blotting); |

| (24756-1-AP) | 1:1,000 (immunocytochemical) | |

| Protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4 | Proteintech Group, Inc. | 1:1,000 (western blotting); |

| (14242-1-AP) | 1:1,000 (immunocytochemical) | |

| Small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 | CST (4930S) | 1:1,000 (western blotting) |

| Small ubiquitin-like modifier 23 | CST (4971T) | 1:1,000 (western blotting) |

| β-actin | OriGene Technologies, | 1:3,000 (western blotting) |

| Inc. (TA-09) | ||

| GAPDH | Affinity (AF7021) | 1:3,000 (western blotting) |

| H3 | Affinity (BF9211) | 1:1,000 (western blotting) |

| Anti-Mouse IgG HRP-linked | CST (7074F) | 1:5,000 (western blotting) |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG HRP-linked | CST (7076F) | 1:5,000 (western blotting) |

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

The primers were designed by Primer 5 (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/primerdesign/). A total of 2.5×106 cells were collected and total RNA was extracted using an RNA extraction kit (cat. no. 9190; Takara Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Transcription levels of MITF and HIF1α were detected by qPCR. The PCR conditions were set according to the instructions provided in the SYBR Green Kit (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The amplification was performed for 40 cycles (95°C 2 min, 95°C 10 sec and 60°C 30 sec). The relative amount of each mRNA level was normalized to that of the β-actin level and the difference in mRNA level was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (18). Detailed information on the primers used is provided in Table II. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Table II.

List of primers used.

| Name | Sense (5′-3′) | Antisense (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia inducible factor 1 α | GAACGTCGAAAAGAAAAGTCTCG | CCTTATCAAGATGCGAACTCACA |

| Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor | ACCTGTTACAACAACTCTCGATCTCA | CTCAGTCCCAGTTCCGAGGTT |

| β-actin | TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA | CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA |

Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction

After an appropriate amount of cell precipitation from Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs, 200 µl cytoplasmic protein extraction reagent A was added to the nuclear protein and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit (cat. no. P0027, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and was placed on ice for lysis for 15 min. Then, 10 µl cytoplasmic protein extraction reagent B was added, placed on ice for cracking for 1 min, vortex-oscillated for 5 sec and then centrifuged at 4°C using centrifuge at 16.2 × g for 15 min. The supernatant comprised the cytoplasmic protein solution, which was then transferred to a pre-cooled Eppendorf tube. The remaining precipitate was rinsed with 500 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) thrice and centrifuged at 0.6 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Subsequently, 50 µl of nuclear protein extraction reagent was added and the precipitation was dissolved on ice for 30 min. After vortex-oscillation every 1 min for 30 sec and centrifugation at 16.2 × g at 4°C for 15 min, the resultant supernatant comprised the nuclear protein solution. The two parts of the supernatant were mixed with 1/4 volume of 5× protein loading buffer and then the protein was denatured at 100°C for 10 min and stored in the refrigerator at −20°C for subsequent experiments.

Immunocytochemical (ICC) staining

Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs were inoculated onto a cover slide. When the cell density reached ~70%, the cells were fixed with methanol at room temperature for 30 min. Hydrophobic circles were drawn with a neutral oil pen. A peroxidase-blocking agent was used to treat the cells in the dark for 15 min and then goat serum-containing working solution was added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 20 min. The corresponding primary antibodies (Table I) were added and incubated at 4°C overnight. The next day, one-to-two drops of biotin-labeled goat anti-rat/rabbit IgG polymer were added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. A DAB color-developing solution was prepared to observe brown particles under a microscope at room temperature for 1–2 min. The color development reaction was stopped after brown staining. Hematoxylin was used to stain at room temperature for 30 sec, followed by alcohol gradient-mediated dehydration, the addition of dimethylbenzene and final mounting with neutral gum.

Plate colony formation assay

The cell samples were diluted to obtain samples with 50, 100 and 150 cells/ml and cultured in 24-well plates with three repeated pores in each group for 2 weeks. Cells were fixed with anhydrous methanol for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature. Cell colonies were counted at ×100 magnification (a single colony was defined as that containing >50 cells). The cell colony formation efficiency was assessed using the following formula: formation efficiency=number of clones/number of inoculated cells.

Wound healing assay

A wound healing assay was used to detect cell migration. Cells (1×105) in the logarithmic growth stage were cultured in a 6-well plate and three repeat pores were set. Single-layer cells were scratched uniformly using sterile pipette tips to create wounds. PBS was used to wash away the detached cells. The cells were then incubated in serum-free RPMI 1640. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; 1.54D) was used to outline the migration area and calculate the wound-healing index according to the following formula: [(the wound area at 0 h)-(the wound area at the indicated time)]/(the wound area at 0 h). A high score indicated stronger migration ability.

Transwell migration and invasion assay

For the Transwell migration assay, 200 µl of serum-free cell suspension containing 1×105 cells was added to the upper chamber of the Transwell chamber and 600 µl of medium containing 20% serum was added to the lower chamber, which was cultured in an incubator for 24 h. The cells were fixed with methanol for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min. The cells were observed under an inverted microscope and three fields (magnification, ×100) were randomly selected, images captured and cells counted. A total of three duplicate wells were set for each group of cells. The procedure for the Transwell invasion experiment was the same as that for the Transwell migration experiment. The difference was that the Transwell invasion experiment required a 200 µl sample containing 5×105 cells and the invasion chamber contained Matrigel (cat. no. 354480; Corning, Inc.). After the cells were added into the chamber with Matrigel, the plates were incubated for 12 h at 37°C.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Co-IP was used to determine the interactions of SUMO1, SUMO2 and HIF1α in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PGCs according to the manufacturer's protocols. When the cell density of the T25 flask reached 80%, the cells were collected in EP tubes. The cells were lysed using 500 µl IP lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing a halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (1:100 dilution) for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 16.2 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to an EP tube containing A/G agarose homogenate of agar glycoprotein beads and shaken at 4°C for 30 min. After incubation, the supernatant was divided into three parts: one part was used to detect the total protein level (input). Primary antibodies corresponding to rabbit IgG and the target protein were added to the other two tubes, respectively and maintained at 4°C overnight. The next day, A/G agarose homogenates of the agar glycoprotein beads were adsorbed by a magnetic grate and washed by lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The samples containing rabbit IgG and primary antibodies (Table I) of the target protein were transferred to the newly washed column and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. After incubation, the supernatant was discarded and washed five times with 500 µl IP-specific cracking buffer. Finally, western blotting was performed to analyze the samples.

Ginkgolic acid (GA) treatment

CoCl2-treated cells were seeded in six-well plates until they reached 80% confluence. Approximately 20 µM of GA (15:1, MedChem Express, USA) was added to control cells and PDCs for 24 h, and the samples were evaluated using western blotting analysis and other assays described.

Cell viability assay

Methyl linoleate (ML), the main active ingredient of Sageretia thea, is a major anti-melanin-producing compound that downregulates MITF expression. To assess cell viability before and after ML treatment, Hct116 and LoVo PDCs were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells per well into 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. The cells were divided into five groups and each group was independently analyzed in triplicate. The cells were treated with ML at concentrations of 40, 80, 160 and 320 µM for 12, 24, 48 and 72 h. After incubation, 10 µl of CCK8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) reagent was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. After adding the CCK8 reagent, the wells were analyzed using a Bio-Rad microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Optical density data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean.

Transient short interfering (si)RNA and plasmid vector transfection

The BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (https://rnaidesigner.thermofisher.com/rnaiexpress/) was used to design the siRNA of MITF. A total of three different siRNA sequences targeting MITF, PIAS4 and negative control siRNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. The K391R, K477R and empty vector was purchased from Genewiz, Inc. The cells were inoculated into a 6-well plate and transfected when the cell confluence reached ~50% at 37°C. According to the manufacturer's experimental protocol, 5 µl of transfect-Mate (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and 5 µl of interfering sequence or plasmids were added to 100 µl of Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to formulate the transfection complexes at room temperature. After 48 h of transfection, cell samples were collected to detect the targeted proteins using western blotting. Detailed information on the siRNA oligonucleotide sequences is provided in Tables III and IV.

Table III.

List of MITF short interfering RNA used.

| Name | Sense (5′-3′) | Antisense (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| MITF-708 | GCUAUGCUUACGCUUAACUTT | AGUUAAGCGUAAGCAUAGCTT |

| MITF-1215 | GUGGACUAUAUCCGAAAGUTT | ACUUUCGGAUAUAGUCCACTT |

| MITF-1303 | GCAUUUGUUGCUCAGAAUATT | UAUUCUGAGCAACAAAUGCTT |

| MITF-PC | UGACCUCAACUACAUGGUUTT | AACCAUGUAGUUGAGGUCATT |

| MITF-NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor.

Table IV.

List of PIAS4 short interfering RNA used.

| Name | Sense (5′-3′) | Antisense (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PIAS4-315 | GCCCUGAGCUGUUCAAGAATT | UUCUUGAACAGCUCAGGGCTT |

| PIAS4-493 | GCUCUACGGAAAGUACUUATT | UAAGUACUUUCCGUAGAGCTT |

| PIAS4-1134 | UCAUCUGUCCGCUGGUGAATT | UUCACCAGCGGACAGAUGATT |

| PIAS4-PC | UGACCUCAACUACAUGGUUTT | AACCAUGUAGUUGAGGUCATT |

| PIAS4-NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

PIAS4, protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4.

Statistical analyses

All data and statistical charts were processed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (Dotmatics) or SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp.) software. Statistical significance was assessed by comparing mean values using the Student's t-test for independent groups. An ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction was used among different groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

CoCl2 can induce the formation of PGCCs

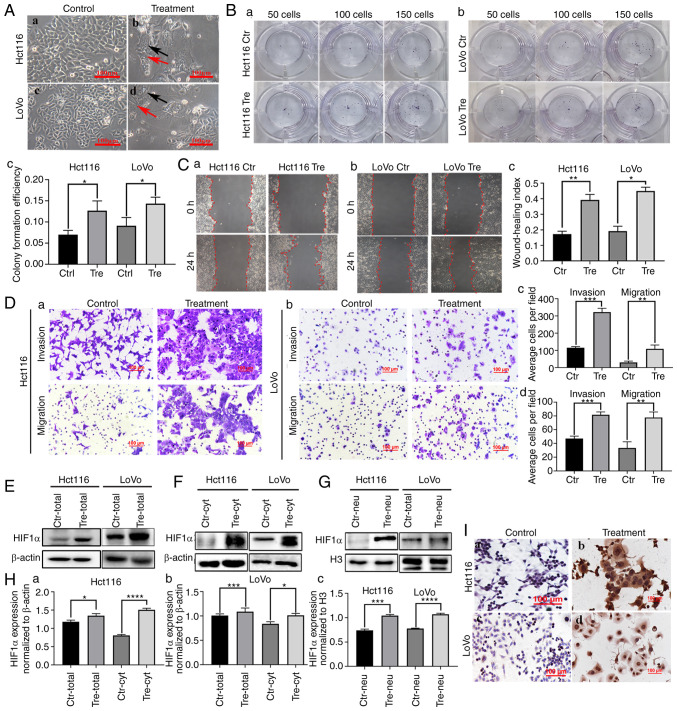

Hct116 and LoVo cells were cultured in a complete medium and their morphologies are shown in Fig. 1A a and c. Control cells were epithelioid and oval in shape, with uniform cell distribution and size. When 450 µM of CoCl2 was added to the flask, most of the regular-sized diploid cancer cells died and only a few cells with large nuclei (PGCCs) survived. After ~15 days of recovery, PGCCs produced daughter cells through asymmetric division (Fig. 1A b and d; Control represents cells without CoCl2 treatment and treatment represents cells with CoCl2 treatment).

Figure 1.

HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo cells before and after CoCl2 treatment. (A) Control cells and PDCs derived from Hct116 and LoVo (magnification, ×100). (a) Hct116 control cells. (b) Hct116 PGCCs and daughter cells. (c) LoVo control cells. (d) LoVo PGCCs with daughter cells. The black arrow indicates PGCCs; the red arrow indicates PDCs. (B) Colony formation of 50, 100 and 150 (a) Hct116 control cells and PDCs, (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs and (c) statistiacal analysis of Colony formation efficiency of Hct116 and LoVo cells before and after CoCl2 treatment. (C) Wound healing assay of (a) Hct116 control cells and (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs at 0 h and 24 h (magnification, ×100). (c) Statistical analysis of wound healing index of Hct116 and LoVo cells before and after CoCl2 treatment. (D) The invasion and migration abilities of (a) Hct116 control cells and PDCs and (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs. Comparison of the average cell number in invasion and migration assay of (c) Hct116 PDCs and (d) LoVo PDCs before and after CoCl2 treatment. (E) Total HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs. (F) Cytoplasmic and (G) nuclear HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs. (H) Statistical analysis of total and cytoplasmic HIF1α expression in (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs and (c) nuclear HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo control cells. (I) Immunocytochemical staining of HIF1α in (a) Hct116 control cells, (b) Hct116 PDCs, (c) LoVo control cells and (d) LoVo PDCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; PDCs, daughter cells; PGCCs, polyploid giant cells; Tre, PGCCs with PDCs; Ctr, control.

Daughter cells derived from PGCCs had strong proliferation, migration and invasion abilities

The results of the plate cloning assay demonstrated that Hct116 and LoVo PDCs had greater proliferative ability than the control cells (Fig. 1B a and b) and the differences were statistically significant (Fig. 1Bc). The wound healing assay showed a significantly higher migration ability of LoVo and HCT116 PDC compared with that of control cells (Fig. 1C a and b) and the differences were statistically significant (Fig. 1Cc), indicating that the migration ability of PGCCs and their progeny cells was stronger than that of the control group. Additionally, Transwell migration and invasion experiments showed that PDC had stronger migration and invasion abilities than the control cells (Fig. 1D).

The expression of HIF1α was upregulated and the subcellular location was altered in PDCs

In the present study, western blotting and ICC were used to detect the expression and subcellular location of HIF1α in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs. The expression of HIF1α was higher in PDCs than in the control cells (Fig. 1E). In the control cells, HIF1α was detected only in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1F). In PDCs, HIF1α was detected in both the cytoplasm (Fig. 1F) and the nucleus (Fig. 1G). Total, cytoplasmic and nuclear HIF1α expression levels were significantly higher in PDCs than in control cells (Fig. 1H). In addition, immunocytochemical staining demonstrated the expression and subcellular localization of HIF1α in control cells and PDCs (Fig. 1I).

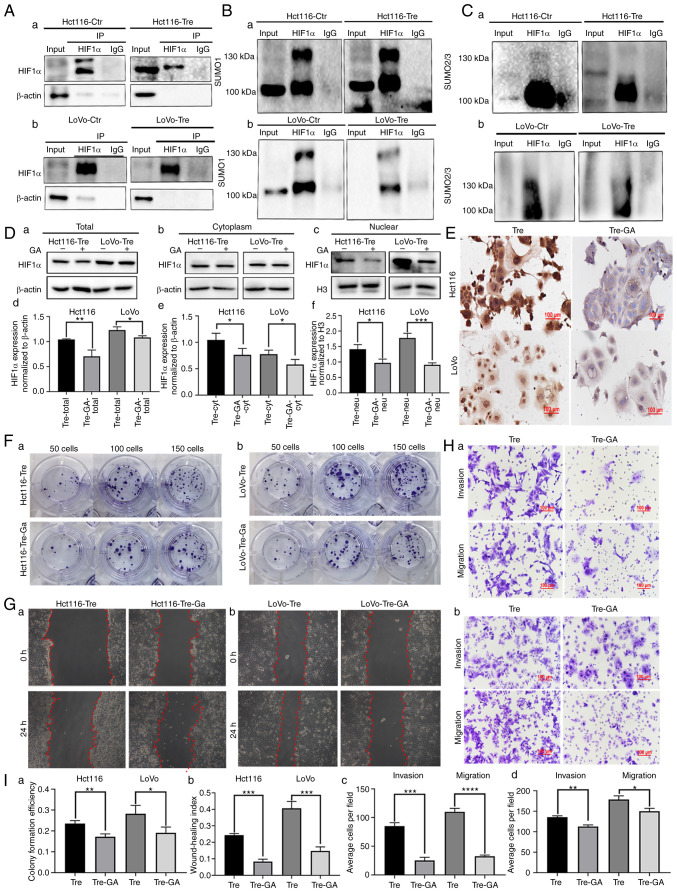

HIF1α is modified by SUMOylation in PDCs

Co-IP was used to detect the interactions between SUMO1, SUMO2/3 and HIF1α. The total cell lysates of control and PDCs were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HIF1α antibody (Fig. 2A) and then immunoblotted with anti-SUMO1 and anti-SUMO2/3 antibodies. The results showed that HIF1α could bind to SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 in PDCs (Fig. 2B and C).

Figure 2.

The nuclear location of HIF1α modified by SUMOylation regulated the migration, invasion and proliferation of PDCs. (A) Results of HIF1α co-immunoprecipitation in (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs (anti-HIF1α was used to perform immunoprecipitation). Total lysates of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HIF1α and immunoblotted with (B) anti-SUMO1 and (C) anti-SUMO2/3. (D) (a) Total, (b) cytoplasmic and (c) nuclear HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after 20 µM GA treatment. Statistical analysis of (d) total, (e) cytoplasmic and (f) nuclear HIF1α expression in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs befoer and after GA treatment. (E) Immunocytochemical staining of HIF1α in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment. (F) Colony formation of 50, 100 and 150 (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment. (G) Wound-healing assay of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment at 0 h and 24 h (magnification, ×100). (H) The invasion and migration abilities of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment. (I) (a) The differences in colony formation efficiency of Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment. (b) Statistical analysis of wound healing index of Hct116 and LoVo cells before and after GA treatment. (c) Comparison of the average cell number in invasion and migration assay of Hct116 PDCs before and after GA treatment. (d) Comparison of the average cell number in invasion and migration assay of LoVo PDCs before and after GA treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, ns, no significance. HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; PDCs, daughter cells; PGCCs, polyploid giant cells; GA, ginkgolic acid; Tre, PGCCs with PDCs; Ctr, control.

Ginkgolic Acid (GA) treatment decreased the nuclear expression of HIF1α and inhibited the migration, invasion and proliferation of PDCs

GA can inhibit the SUMOylation of important proteins that are critical during the development and progression of malignant tumors (19). GA directly binds to the SUMO E1 activating enzyme to inhibit the formation of the E1-SUMO thioester complex (20). After GA treatment, the total, cytosolic and nuclear fractions were collected to detect the expression of HIF1α. In the cytosolic fraction, the expression of HIF1α in PDCs was slightly inhibited after GA treatment compared with that in PDCs without GA treatment (Fig. 2D b and e). The total and nuclear localization of HIF1α was inhibited by GA treatment and the differences before and after GA treatment in PDCs were statistically significant (Fig. 2D a, c, d and f), indicating that SUMOylation might play an important role in the nuclear localization of HIF1α. Additionally, ICC staining was performed on the cells before and after GA treatment. Staining results showed that GA treatment inhibited the nuclear expression of HIF1α (Fig. 2E).

Functional cell experiments were performed to assess the effect of GA on PDC migration, invasion and proliferation before and after GA treatment. Cloning experiments showed that the number of PDCs decreased after GA treatment (Fig. 2F). The number of colonies of 50, 100 and 150 GA-treated PDCs was reduced compared with that of untreated Hct116 and LoVo PDCs (Fig. 2F and Ia). Wound healing experiments showed that the scratched areas of PDCs before GA treatment were significantly narrower than those after GA treatment (Fig. 2G and Ib). The results of the Transwell assay showed that the migratory and invasive abilities of PDCs treated with GA were inhibited compared with those of PDCs without GA treatment (Fig. 2H and I c and d).

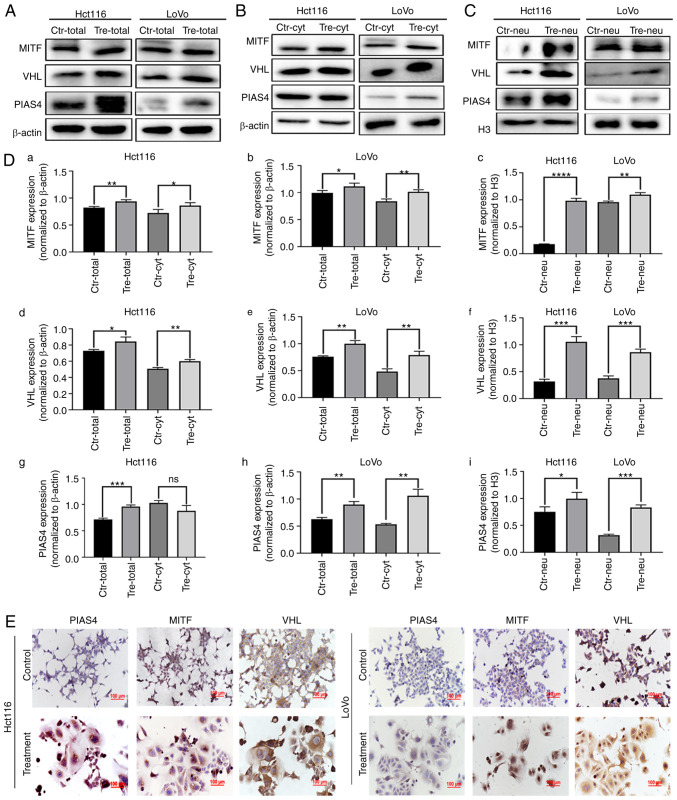

Total, cytosolic and nuclear expression of MITF, PIAS4 and von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor (VHL) in control and PDCs

The expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL is an important indicator influencing the expression and subcellular location of HIF1α. Total, cytosolic and nuclear fractions were collected to detect the expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL in control cells and PDCs. The total protein levels of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL were elevated in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs compared with those in control cells (Fig. 3A and D). In the cytosolic fraction, the expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL in LoVo PDCs was upregulated (Fig. 3B and D). After CoCl2 treatment, the expression levels of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL in the nucleus were also higher than those in control cells (Fig. 3C and D). For further verification, ICC staining was performed and the results showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL. The staining intensity of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL in PDCs was stronger than that of control cells (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Total, cytosolic and nuclear expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL in control cells and PDCs. Western blotting showing the (A) total (B) cytoplasmic and (C) nuclear protein ex pression of PIAS4, MITF and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs. (D) Statistical analysis of the expression differences of (a) total, (b) cytoplasmic and (c) nuclear MITF expression; (d) total, (e) cytoplasmic and (f) nuclear VHL expression; (g) total, (h) cytoplasmic and (i) nuclear PIAS4 expression in Hct116 and LoVo control and PDCs. (E) Immunocytochemical staining of PIAS4, MITF and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo control cells and PDCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. PIAS4, protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4; MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor PDCs, daughter cells; Tre, polyploid giant cells PDCs.

MITF regulates the SUMOylation of HIF1α

MITF can bind to the HIF1α promoter and stimulate its transcriptional activity (21). To confirm whether MITF interacts with HIF1α, Co-IP was performed. When HIF1α was used as a bait protein and incubated with MITF, MITF bands appeared in the input and IP groups, indicating that HIF1α interacted with MITF (Fig. 4A). Additionally, MITF was knocked down using siRNAs. Following MITF knockdown, the mRNA expression levels of MITF and HIF1α were detected by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 4B, the mRNA expression levels of MITF and HIF1α were significantly decreased in PDCs.

Figure 4.

MITF regulates the SUMOylation of HIF1α. (A) The interaction between HIF1α and MITF was verified by Co-IP in (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo control cells and PDCs. (B) mRNA expression levels of (a and c) MITF and (b and d) HIF1α were detected in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs following MITF knockdown. (C) (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs were treated with ML at different concentrations (40, 80, 160 and 320 µM). At each time point (0, 20, 40, 60 and 80 h), cell viability was assessed using CCK8 assay. (D) Western blotting showing the (a) total, (b) cytoplasmic and (c) nuclear expression of MITF, HIF1α, SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs following treatment with different concentrations of ML. (d) Western blotting showing the expression of VHL in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs following treatment with differernt concentrations of ML. (E) Colony formation of 50, 100 and 150 (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment. (F) Wound healing assay of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment at 0 h and 24 h (magnification, ×100). (G) (a) The differences in colony formation efficiency of Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment. (b) Statistical analysis of wound healing index of Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment. (H) The invasion and migration abilities of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment. (I) Comparison of the average cell number in invasion and migration assay of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after ML treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; Co-IP, co-immunoprecipitation; PDCs, daughter cells; ML, methyl linoleate; PGCCs, polyploid giant cells; Tre, PGCCs with PDCs; Ctr, control.

ML, the main active ingredient in S. thea, is a major anti melanin-producing compound that downregulates MITF expression. CCK8 was used to screen the appropriate concentration of ML and 40, 80 and 160 µM were finally selected (Fig. 4C). After ML treatment, the western blotting results showed that the total, cytosolic and nuclear expression of HIF1α, SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 was inhibited to varying degrees. Nuclear expression of HIF1α in PDCs was inhibited, suggesting that MITF may play an important role in the nuclear localization of HIF1α. Compared to the control cells, the expression levels of nuclear SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 also decreased after ML treatment, indicating that MITF can regulate SUMOylation of HIF1α and further affect the nuclear location of HIF1α (Fig. 4Da-c). Following ML treatment, the western blotting results showed that the expression of VHL was inhibited (Fig. 4Dd). Functional experiments were also performed on the PDCs before and after ML treatment. The proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of PDCs were inhibited after ML treatment, as demonstrated by plate cloning (Fig. 4E and Ga), wound healing (Fig. 4F and Gb) and Transwell experiments (Fig. 4H and I).

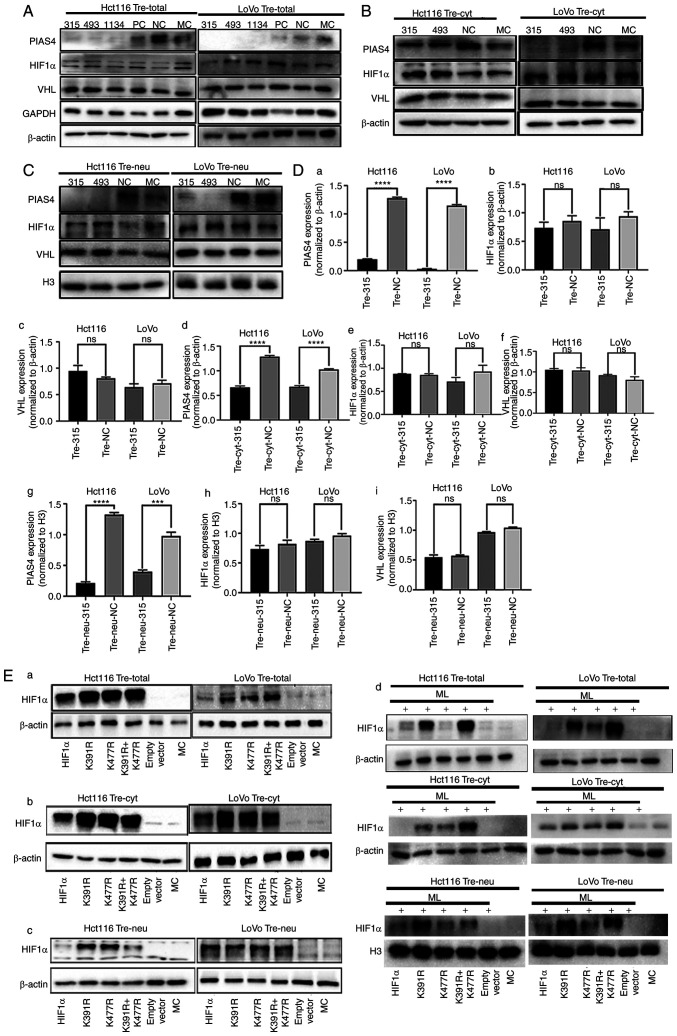

The expression of PIAS4 is not associated with HIF1α or VHL expression in PDCs

PIAS4 belongs to the PIAS protein family, which are protein inhibitors that activate STAT proteins. PIAS4 is often involved in PTM as it acts as a SUMO E3 ligase. VHL is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. PIAS4 mediates the SUMOylation of VHL and reduces the activity of its ubiquitin E3 ligase, contributing to the stabilization of HIF1α (22). The present study demonstrated no significant change in the protein expression levels of VHL, HIF1α and MITF following the knockdown of PIAS4 using siRNA (Fig. 5A and Da-c and Fig. S1). In addition, no significant differences were observed in the expression of cytoplasmic and nuclear VHL and HIF1α after PIAS4 knockdown (Figs. 5B, C and Dd-i and S1).

Figure 5.

HIF1α is modified by SUMOylation at different lysine sites. (A) Expression of total PIAS4, HIF1α and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs transfected with siRNA PIAS4-315, 493, 1134, PC, NC and MC, respectively. (B) Expression of cytoplasmic PIAS4, HIF1α and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs transfected with siRNA PIAS4-315, 493, NC and MC, respectively. (C) The expression of nuclear PIAS4, HIF1α and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs transfected with siRNA PIAS4-315, 493, NC and MC, respectively. (D) Histograms showing the expression of total, plasma and nuclear PIAS4, HIF1α and VHL in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs and PDCs after PIAS knockdown. (E) The expression of total, cytoplasmic and nuclear HIF1α was detected by western blotting Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with wild type HIF1α, K391R, K477R, K391R and K477R double mutants. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, ns, no significance. PIAS4, protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4; HIF1α, Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor; si, short interfering; PDCs, daughter cells; PC, positive control; NC, negative control; MC, mock control; PGCCs, polyploid giant cells; Tre, PGCCs with PDCs.

HIF1α is modified by SUMOylation at k391 and k477 sites

The proteins that can undergo SUMOylation have a known consensus motif: ΨKXE (Ψ: a hydrophobic amino acid, K: lysine residue, X: a variable residue amino acid, E or D: a glutamic acid) (23). Two lysine sites, K391 and K477, were revealed by the GSP-SUMO1.0 (The Cuckoo Workgroup) computer analysis software and the amino acid sequences of the two sites were 390–393 (LKKE) and 476–479 (LKLE), which met the characteristics of SUMOylation (Table V).

Table V.

GSP-SUMO1.0 prediction of candidate SUMOylation sites of HIF-1α.

| No. | Position | Peptide | Score | Cutoff | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 220-224 | KKPPMTC LVLIC EPIPHPS | 61.735 | 59.29 | SUMO interaction |

| 2 | 391 | SSLFDKLKKEPDALT | 29.24 | 16 | SUMOylation |

| 3 | 408-412 | APAAGDT IISLD FGSNDTE | 59.572 | 59.29 | SUMO interaction |

| 4 | 477 | LNQEVALKLEPNPES | 27.474 | 16 | SUMOylation |

| 5 | 635-639 | TKDRMED IKILI ASPSPTH | 68.227 | 59.29 | SUMO interaction |

| 6 | 771-775 | NGMEQKT IILIP SDLACRL | 65.589 | 59.29 | SUMO interaction |

Italic type shows the amino acids which are modified by the SUMOylation in the peptide. SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier.

To determine whether HIF1α is SUMOylated at K391 and K477 sites, the plasmid with mutated lysine to arginine was transiently transfected. Compared with the empty plasmid and blank control groups, the expression level of HIF1α was higher in the HIF1α overexpression and the mutant groups. The expression level of HIF1α in the HIF1α overexpression group was lower than that in the mutant group, which indicated that HIF1α was not degraded in the mutation group because lysine was mutated to arginine and ubiquitination could not bind the lysine sites (Fig. 5Ea). The expression level of cytoplasmic HIF1α in different groups was consistent with that of total protein (Fig. 5Eb). However, the expression level of nuclear HIF1α in the K391R+K477R group decreased, indicating that HIF1α with mutated arginine sites cannot be modified by SUMOylation or enter the nucleus (Fig. 5Ec). The expression levels of HIF1α with K391R, K477R, K391R and K477R double mutants in ML-treated cells are shown in Fig. 5Ed.

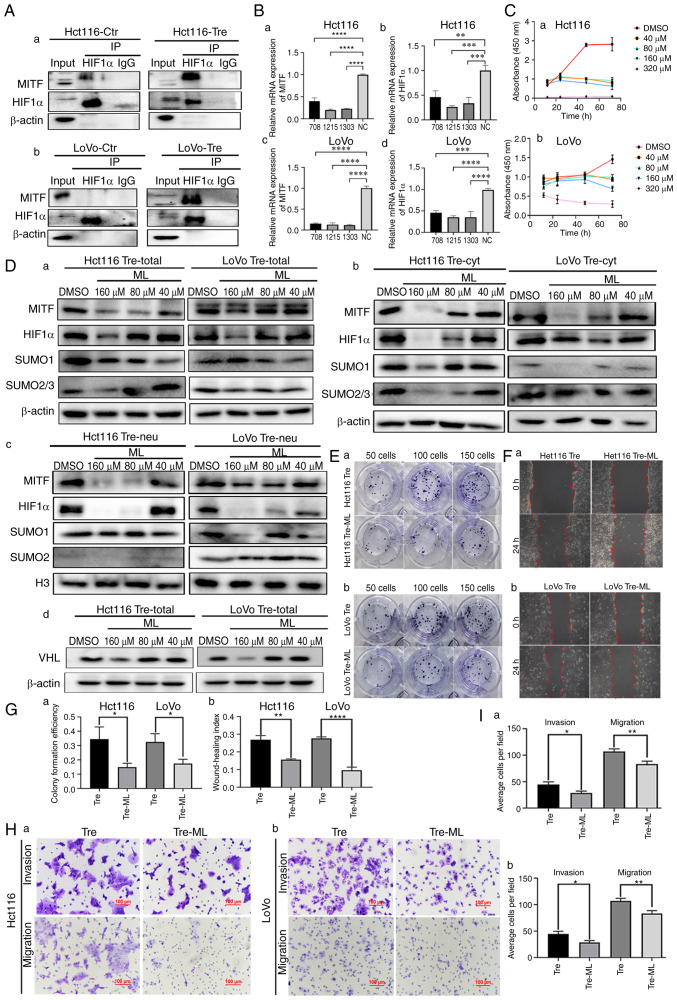

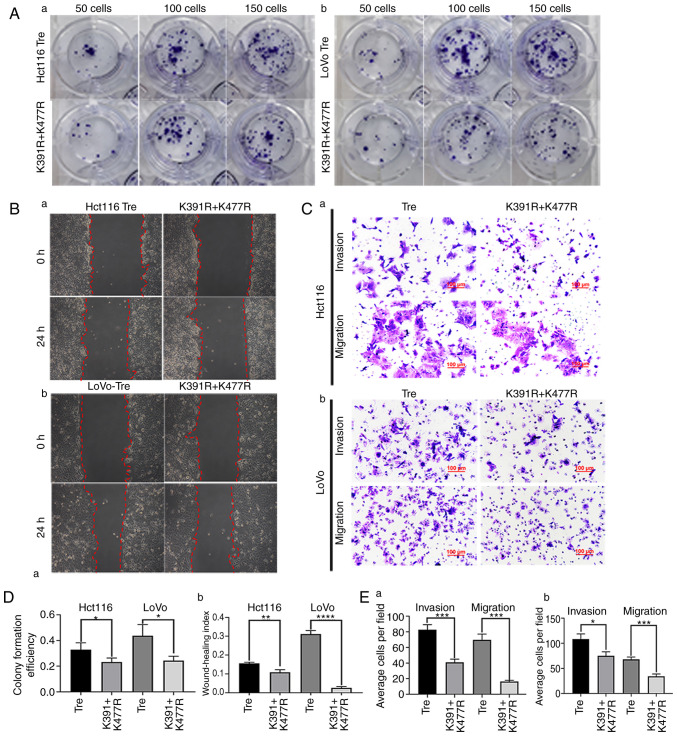

To further investigate the effects of mutation of HIF1α at sites K391 and K477 on cell proliferation, migration and invasion in PDCs, cell functional experiments, including plate cloning, wound healing, Transwell migration and invasion assays, were performed. The results showed that the proliferation (Fig. 6A and Da), migration (Fig. 6B and Db) and invasion (Fig. 6C and E) abilities of Hct116 and LoVo PDCs after mutation were significantly lower than those in the non-mutation group.

Figure 6.

The mutation of HIF1α at different lysine sites is associated with the proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of PDCs. (A) Colony formation of 50, 100 and 150 (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with K391R and K477R double mutants. (B) Wound healing assay of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with K391R and K477R double mutants at 0 h and 24 h (magnification, ×100). (C) Invasion and migration abilities of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with K391R and K477R double mutants. (D) (a) Differences in colony formation efficiency and (b) statistical analysis of wound healing index in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with K391R and K477R double mutants. (E) Comparison of the average cell number in invasion and migration assay of (a) Hct116 and (b) LoVo PDCs before and after transfection with K391R and K477R double mutants. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 ns, no significance. PDCs, daughter cells; PGCCs, polyploid giant cells; Tre, PGCCs with PDCs.

Discussion

CoCl2, chemical reagents, radiotherapy and Chinese herbal medicines can induce PGCC formation and the daughter cells derived from these PGCCs have strong proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities. PGCCs are more frequently observed in high-grade malignancies and metastatic foci than in low-grade tumors and primary sites. PDCs with daughter cells can exert important effects on the progression of malignant tumors, including induction of metastasis, chemoresistance and tumor relapse (24–26). The present study demonstrated that the expression and subcellular location of HIF1α changed in the treated cells compared with the control cells. SUMOylation can affect the stable expression and nuclear localization of HIF1α. HIF1α modified by SUMOylation could enter the nucleus and play an important role in regulating the proliferation, migration and invasion of PDCs. The protein expression level of HIF1α decreased and nuclear localization was weakened after the use of SUMOylation inhibitors.

SUMOylation is an important PTM involved in the development and progression of malignant tumors, such as B-cell lymphoma (27), multiple myeloma (28), bladder cancer (29) and CRC (4). The target protein modified by SUMOylation can regulate the protein-protein interaction and subcellular location and promote the stability of the target protein (30). Abnormal regulation of SUMOylation promotes cancer metastasis, angiogenesis, invasion and proliferation (31). SUMOylation is also an important anti-stress mechanism and high levels of SUMOylation are required for cancer cells to survive internal and external stresses. Tumor cells become more aggressive in response to both internal and external stresses. Prevention of tumor metastasis, recurrence and radiochemotherapy resistance can be partially achieved by attenuating SUMOylation (32).

In addition, the expression of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL is a crucial factor affecting the expression and subcellular location of HIF1α. The total protein levels of MITF, PIAS4 and VHL were elevated in Hct116 and LoVo PDCs compared with those in control cells. The qPCR results showed that the mRNA expression level of HIF1α decreased after MITF knockdown, indicating that MITF can regulate the expression of HIF1α at the transcriptional level. MITF has been extensively studied. After inhibiting the expression of MITF, the expression of HIF1α reduced. MITF can regulate the SUMOylation modification of HIF1α by affecting the expression of SUMO1 and SUMO2/3. In addition, MITF can bind to the HIF1α promoter as a transcription factor to mediate the cAMP effects on the expression of HIF1α (21). MITF silencing clearly inhibited the cAMP-induced HIF1α promoter transactivation (21). MITF is positively associated with melanocyte survival, proliferation and differentiation and is involved in cancer progression (33). MITF expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (34). Additionally, MITF is involved in autophagy and cellular homeostasis in lung cancer (35). The overexpression of MITF in human melanoma cells stimulates the expression of HIF1α mRNA, which plays a pro-survival role in melanoma (21).

PIAS4 belongs to the PIAS protein family and has been implicated in a number of biological activities, such as regulating the DNA-binding activity of transcription factors, recruiting coactivators and participating in PTM through its SUMO E3 ligase activity (36). In synovial sarcoma, PIAS4 mediates SUMOylation, leading to the overexpression of nuclear receptor coactivator 3, which is critical for tumor formation (37). In hepatocellular carcinoma, PIAS4 regulates the SUMOylation of NEMO (an essential regulator of NF-κB) and activation of NF-κB in response to DNA damage (38). The important role of PIAS4 in regulating the growth of pancreatic cancer cells and enhancing HIF1-α activity by regulating VHL SUMOylation has garnered our interest (39). The present study proved that the expression of PIAS4 was not associated with the expression or subcellular localization of HIF1α in PDCs. Therefore, SUMO E3 ligase PIAS4 may not play a role in regulating the expression of HIF1α. Additionally, HIF1α was degraded through a VHL-dependent mechanism. PIAS4 mediates the SUMOylation of VHL and reduces the activity of its ubiquitin E3 ligase, contributing to the stabilization of HIF1α (22). In the present study, the expression levels of total, plasma and nuclear VHL proteins showed no significant downward trends following PIAS4 knockdown.

HIF1α can be SUMOylated at K391R and K477R (23). Site-mutated plasmids based on lysine in the amino acid sequence of HIF1α were designed and the transfected plasmids were subjected to distinct lysine site modifications within cellular environments employing a transient plasmid transfection methodology. The results confirmed that the total and nuclear protein expression of HIF1α with double mutations K391R and K477R was lower than that with single mutations K391R and K477R in PDCs. The proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of PDCs were weakened when the K391R and K477R sites of HIF1α were mutated.

In conclusion, the expression of HIF1α increased and its subcellular localization was altered, which was associated with the proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of CoCl2-induced PDCs. HIF1α can undergo SUMOylation at the lysine residues K391 and K477. MITF can regulate the transcription and protein levels of HIF1α and participate in the regulation of HIF1α SUMOylation, but PIAS4 does not regulate HIF1α SUMOylation. However, molecular mechanism by which HIF1α locates in the nucleus and regulates the migration and invasion of PDCs is still unclear and requires further research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CoCl2

cobalt chloride

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- PTM

post-translational modification

- Co-IP

co-immunoprecipitation

- GA

ginkgolic acid

- HIF1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha

- ICC

immunocytochemical

- MITF

microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

- MC

mock control

- NC

negative control

- PC

positive control

- PGCCs

polyploid giant cells

- ML

methyl linoleate

- PIAS4

protein inhibitor of activated STAT protein 4

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor

Funding Statement

The present study was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82173283 and 82103088) and Foundation of the Committee on Science and Technology of Tianjin (grant nos. 21JCZDJC00230, 21JCYBJC00190 and 21JCYBJC01070).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision was by SZ. Research was performed by MZhe, ST and XZ. MZho, YY, YZ, XW, MY and NL confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. MZhe and ST wrote the manuscript. Reviewing and editing was by LR and SZ. Funding acquisition was by SZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fan L, Zheng M, Zhou X, Yu Y, Ning Y, Fu W, Xu J, Zhang S. Molecular mechanism of vimentin nuclear localization associated with the migration and invasion of daughter cells derived from polyploid giant cancer cells. J Transl Med. 2023;21:719. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04585-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z, Zheng M, Zhang H, Yang X, Fan L, Fu F, Fu J, Niu R, Yan M, Zhang S. Arsenic trioxide promotes tumor progression by inducing the formation of PGCCs and embryonic hemoglobin in colon cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2021;11:720814. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.720814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Xing Z, Sun B, Kuang J, Liu J. Generation of cancer stem-like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:116–128. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Q, Zhang K, Li Z, Zhang H, Fu F, Fu J, Zheng M, Zhang S. High migration and invasion ability of PGCCs and their daughter cells associated with the nuclear localization of S100A10 modified by SUMOylation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:696871. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.696871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nehme Z, Pasquereau S, Haidar Ahmad S, El Baba R, Herbein G. Polyploid giant cancer cells, EZH2 and Myc upregulation in mammary epithelial cells infected with high-risk human cytomegalovirus. EBioMedicine. 2022;80:104056. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv H, Shi Y, Zhang L, Zhang D, Liu G, Yang Z, Li Y, Fei F, Zhang S. Polyploid giant cancer cells with budding and the expression of cyclin E, S-phase kinase-associated protein 2, stathmin associated with the grading and metastasis in serous ovarian tumor. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:576. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowers RR, Andrade MF, Jones CM, White-Gilbertson S, Voelkel-Johnson C, Delaney JR. Autophagy modulating therapeutics inhibit ovarian cancer colony generation by polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) BMC Cancer. 2022;22:410. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09503-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pustovalova M, Blokhina T, Alhaddad L, Chigasova A, Chuprov-Netochin R, Veviorskiy A, Filkov G, Osipov AN, Leonov S. CD44+ and CD133+ non-small cell lung cancer cells exhibit DNA damage response pathways and dormant polyploid giant cancer cell enrichment relating to their p53 status. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:4922. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilé-Silva A, Lopez-Beltran A, Rasteiro H, Vau N, Blanca A, Gomez E, Gaspar F, Cheng L. Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the prostate: Clinicopathologic analysis and oncological outcomes. Virchows Arch. 2023;482:493–505. doi: 10.1007/s00428-022-03481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wicks EE, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors: Cancer progression and clinical translation. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e159839. doi: 10.1172/JCI159839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konopleva MY, Jordan CT. Leukemia stem cells and microenvironment: Biology and therapeutic targeting. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:591–599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paredes F, Williams HC, San Martin A. Metabolic adaptation in hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;502:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Wang X, Fang B. HIF1A promotes miR-210/miR-424 transcription to modulate the angiogenesis in HUVECs and HDMECs via sFLT1 under hypoxic stress. Mol Cell Biochem. 2022;477:2107–2119. doi: 10.1007/s11010-022-04428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Mercado-Uribe I, Hanash S, Liu J. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of polyploid giant cancer cells and budding progeny cells reveals several distinct pathways for ovarian cancer development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei J, Yang Y, Lu M, Lei Y, Xu L, Jiang Z, Xu X, Guo X, Zhang X, Sun H, You Q. Recent advances in the discovery of HIF-1α-p300/CBP inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2018;18:296–309. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160630124938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du L, Liu W, Rosen ST. Targeting SUMOylation in cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2021;33:520–525. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itokawa H, Totsuka N, Nakahara K, Takeya K, Lepoittevin JP, Asakawa Y. Antitumor principles from ginkgo biloba L. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1987;35:3016–3020. doi: 10.1248/cpb.35.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu K, Wang X, Li D, Xu D, Li D, Lv Z, Zhao D, Chu WF, Wang XF. Ginkgolic acid, a SUMO-1 inhibitor, inhibits the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma by alleviating SUMOylation of SMAD4. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;16:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buscà R, Berra E, Gaggioli C, Khaled M, Bille K, Marchetti B, Thyss R, Fitsialos G, Larribère L, Bertolotto C, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1{alpha} is a new target of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) in melanoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:49–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai Q, Verma SC, Kumar P, Ma M, Robertson ES. Hypoxia inactivates the VHL tumor suppressor through PIASy-mediated SUMO modification. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae SH, Jeong JW, Park JA, Kim SH, Bae MK, Choi SJ, Kim KW. Sumoylation increases HIF-1alpha stability and its transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haidar Ahmad S, El Baba R, Herbein G. Polyploid giant cancer cells, cytokines and cytomegalovirus in breast cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23:119. doi: 10.1186/s12935-023-02971-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casotti MC, Meira DD, Zetum ASS, Araújo BC, Silva DRCD, Santos EVWD, Garcia FM, Paula F, Santana GM, Louro LS, et al. Computational biology helps understand how polyploid giant cancer cells drive tumor success. Genes (Basel) 2023;14:801. doi: 10.3390/genes14040801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alhaddad L, Chuprov-Netochin R, Pustovalova M, Osipov AN, Leonov S. Polyploid/multinucleated giant and slow-cycling cancer cell enrichment in response to X-ray irradiation of human glioblastoma multiforme cells differing in radioresistance and TP53/PTEN status. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1228. doi: 10.3390/ijms24021228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoellein A, Fallahi M, Schoeffmann S, Steidle S, Schaub FX, Rudelius M, Laitinen I, Nilsson L, Goga A, Peschel C, et al. Myc-induced SUMOylation is a therapeutic vulnerability for B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;124:2081–2090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-584524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Driscoll JJ, Pelluru D, Lefkimmiatis K, Fulciniti M, Prabhala RH, Greipp PR, Barlogie B, Tai YT, Anderson KC, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, et al. The sumoylation pathway is dysregulated in multiple myeloma and is associated with adverse patient outcome. Blood. 2010;115:2827–2834. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia QD, Sun JX, Xun Y, Xiao J, Liu CQ, Xu JZ, An Y, Xu MY, Liu Z, Wang SG, Hu J. SUMOylation pattern predicts prognosis and indicates tumor microenvironment infiltration characterization in bladder cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:864156. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.864156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai X, Zhang T, Hua D. Ubiquitination and SUMOylation: Protein homeostasis control over cancer. Epigenomics. 2022;14:43–58. doi: 10.2217/epi-2021-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bettermann K, Benesch M, Weis S, Haybaeck J. SUMOylation in carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2012;316:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han ZJ, Feng YH, Gu BH, Li YM, Chen H. The post-translational modification, SUMOylation, and cancer (review) Int J Oncol. 2018;52:1081–1094. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: Master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nooron N, Ohba K, Takeda K, Shibahara S, Chiabchalard A. Dysregulated expression of MITF in subsets of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2017;242:291–302. doi: 10.1620/tjem.242.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Qin X, Wang B, Xu G, Zhang J, Jiang X, Chen C, Qiu F, Zou Z. MiTF is associated with chemoresistance to cisplatin in A549 lung cancer cells via modulating lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:6563–6573. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S255939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Mechanisms, regulation and consequences of protein SUMOylation. Biochem J. 2010;428:133–145. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Y, Perera J, Rubin BP, Huang J. SYT-SSX1 (synovial sarcoma translocated) regulates PIASy ligase activity to cause overexpression of NCOA3 protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mabb AM, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Miyamoto S. PIASy mediates NEMO sumoylation and NF-kappaB activation in response to genotoxic stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:986–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chien W, Lee KL, Ding LW, Wuensche P, Kato H, Doan NB, Poellinger L, Said JW, Koeffler HP. PIAS4 is an activator of hypoxia signalling via VHL suppression during growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1795–1804. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in the present study are included in the figures and/or tables of this article.