Abstract

Background

The incorporation of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) into the management of operable breast cancer (BC) has been hampered by the heterogeneous results from different studies. We aimed to assess the prognostic value of ctDNA in patients with operable (non metastatic) BC.

Materials and methods

A systematic search of databases (PubMed/Medline, Embase, and CENTRAL) and conference proceedings was conducted to identify studies reporting the association of ctDNA detection with disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with stage I-III BC. Log-hazard ratios (HRs) were pooled at each timepoint of ctDNA assessment (baseline, after neoadjuvant therapy, and follow-up). ctDNA assays were classified as primary tumor-informed and non tumor-informed.

Results

Of the 3174 records identified, 57 studies including 5779 patients were eligible. In univariate analyses, ctDNA detection was associated with worse DFS at baseline [HR 2.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.92-4.63], after neoadjuvant therapy (HR 7.69, 95% CI 4.83-12.24), and during follow-up (HR 14.04, 95% CI 7.55-26.11). Similarly, ctDNA detection at all timepoints was associated with worse OS (at baseline: HR 2.76, 95% CI 1.60-4.77; after neoadjuvant therapy: HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.44-5.14; and during follow-up: HR 9.19, 95% CI 3.26-25.90). Similar DFS and OS results were observed in multivariate analyses. Pooled HRs were numerically higher when ctDNA was detected at the end of neoadjuvant therapy or during follow-up and for primary tumor-informed assays. ctDNA detection sensitivity and specificity for BC recurrence ranged from 0.31 to 1.0 and 0.7 to 1.0, respectively. The mean lead time from ctDNA detection to overt recurrence was 10.81 months (range 0-58.9 months).

Conclusions

ctDNA detection was associated with worse DFS and OS in patients with operable BC, particularly when detected after treatment and using primary tumor-informed assays. ctDNA detection has a high specificity for anticipating BC relapse.

Key words: breast neoplasms, circulating tumor DNA, liquid biopsy, prognosis, disease-free survival, sensitivity and specificity, tumor biomarker

Highlights

-

•

Studies evaluating ctDNA in early breast cancer (BC) had heterogeneous results.

-

•

In this meta-analysis, ctDNA detection was associated with an increased risk of BC recurrence and death.

-

•

The association with worse outcomes was stronger when ctDNA was detected after treatment and by primary tumor-informed assays.

-

•

ctDNA detection had a high specificity for anticipating BC relapse.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide.1 Although screening and treatment advancements have improved the chances of cure for patients with newly diagnosed BC, a significant number still experience incurable metastatic disease relapse.2 Regrettably, clinical, pathological, and molecular tools currently available are not accurate enough to identify patients who will experience a relapse.

The assessment of cell-free circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in plasma has been studied as a prognostic biomarker, as well as a tool for detecting minimal residual disease and monitoring response to treatment.3 Recent advances in ctDNA detection and characterization methodologies have been supporting its incorporation into clinical practice in several types of cancer, including metastatic BC.4,5 However, the integration of ctDNA assessment into the management of operable BC has been challenging, mainly due to the heterogeneity of methodologies and results obtained by different studies and the absence, so far, of a clear demonstration of the clinical value of this biomarker for decision making.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to evaluate the value of ctDNA as a biomarker for BC recurrence and death, as well as to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, and time window between ctDNA detection and the diagnosis of BC recurrent disease.

Materials and methods

This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.6 The study protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021286591).

Search strategy and data extraction

A systematic literature review was carried out in PubMed/Medline, CENTRAL, and Embase databases searching for studies published up to 23 November 2022 that evaluated the association between the ctDNA and clinical outcomes in patients with operable BC. Conference proceedings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, ESMO Breast Cancer Annual Congress, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), and American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) 2000-2022 were also searched for eligibility. The search strategy included domains related to ‘breast cancer’, ‘circulating tumor DNA’, and outcomes (‘prognosis’ or ‘survival’) and was adapted for each bibliographic database and to cover word variations, synonyms, and related terms. The complete search string is presented in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390.

Two investigators (GNM and EA) independently screened records for inclusion. In case of disagreement, consensus was obtained after consultation with another investigator (SDC). When available, data extracted included (i) general information (author, title, publication date, journal, and study type); (ii) patient and primary tumor characteristics; (iii) ctDNA methods, and (iv) outcomes [overall survival (OS); disease-free survival (DFS); lead time between ctDNA detection and the clinical manifestation of disease relapse; and true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative rates]. The tumor-informed assay was defined as ctDNA evaluation based on initial genomic profiling of the primary tumor tissue samples to identify tumor-derived alterations. Timepoints of ctDNA assessment were classified as baseline (before any local or systemic therapy), after the completion of neoadjuvant therapy (before or after surgery), and follow-up (during the adjuvant or follow-up period).

Study selection

To be included, eligible records should fulfill the following criteria: (i) randomized clinical trials or observational studies (prospective or retrospective); (ii) include patients with operable (non metastatic) BC treated with curative intent; (iii) assess ctDNA in blood samples; and (iv) provide data on the association between ctDNA and outcomes (OS and DFS). There were no restrictions on the methods of ctDNA detection and analysis.

Objectives and endpoints

The main objective was to evaluate whether patients with detected ctDNA in blood samples at baseline, after treatment, or during follow-up have worse outcomes (DFS and OS) compared with those without ctDNA. DFS definition was based on the studies and included any type of relapse event, such as event-free survival, relapse-free survival, distant disease-free survival, and invasive disease-free survival events. Secondary objectives were (i) evaluation of different ctDNA methods [primary tumor-informed versus non tumor-informed (agnostic)]; (ii) evaluation of ctDNA sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing relapse; and (iii) lead time between ctDNA detection and the diagnosis of disease relapse.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two authors (MM and MC) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool recommended by the Cochrane Prognosis Methods Group to assess the risk of bias in prognostic studies.7 Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion. Funnel plots were used for publication bias assessment.

Statistical analysis

For time-to-event outcomes (DFS and OS), log-hazard ratios (log-HRs) and their standard error were pooled using a random-effects inverse of variance model and were reported as HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) at each timepoint (baseline, after neoadjuvant therapy, and follow-up) in the ‘tumor-informed’ and ‘non tumor-informed’ groups. ctDNA was treated as a binary variable (present/absent) for the analyses. When available, both univariate and multivariate HRs were extracted and then pooled separately. Multivariate HRs were extracted regardless of the variables included in each study’s models. Heterogeneity was analyzed by the I2 statistic (with I2 values ≥60% considered as ‘substantial heterogeneity’) and the chi-square test (statistically significant for P value <0.10). To assess the accuracy of ctDNA in assessing the presence or absence of disease relapse, true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative rates were collected whenever available. Then, forest plots pooling the sensitivity and specificity of all the selected studies were created. All analyses were carried out using RevMan 5.4.1 software (Cochrane, London, UK).8

Results

From 3174 records identified, 57 studies with data from 5779 patients were included in this systematic review and 42 (N = 4729) in the meta-analysis (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390). Most studies included (42/57) were prospective (clinical trials or prospective cohorts). Distribution according to BC staging was reported for 44.1% (2548/5779) of included patients, with 18.3% (466/2548), 60.2% (1534/2548), and 21.5% (548/2548) classified as stages I, II, and III, respectively. The majority of studies (63.2%, 36/57) included all BC subtypes. Treatment strategies in the included studies consisted of upfront surgery followed by adjuvant therapy in 45.6% (26/57) of studies and 54.2% (3131/5779) of patient cases. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the studies and patients included and Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390, describes the characteristics of each study included. Among the evaluable studies, the risk of bias was classified as low in 18 studies, moderate in 6, and high in 15 studies. Publication bias assessment and a detailed description of the risk of bias for each study are reported in the Supplementary Appendix (Table S3 and Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390). Substantial heterogeneity was identified in the multivariate analyses at the end of neoadjuvant therapy and in the analyses assessing the follow-up period. The association between ctDNA detection and survival outcomes at different timepoints is described in the subsequent sections and summarized in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390.

Table 1.

Studies and patients’ characteristics

| Studies included (N = 57), n (%) | Number of patients (N = 5779), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Prospective cohort | 31 (54.4) | 244 (42.3) |

| Retrospective | 15 (26.3) | 1981 (34.3) |

| Clinical trial | 11 (19.3) | 1351 (23.6) |

| Circulating tumor DNA methodology | ||

| Tumor-informed | 34 (59.6) | 2381 (41.2) |

| Non tumor-informed | 23 (40.4) | 3398 (58.8) |

| Breast cancer subtype | ||

| Mixed | 36 (63.2) | 3870 (67.0) |

| TNBC | 12 (21.0) | 1329 (23.0) |

| HR-positive/HER2-negative | 6 (10.5) | 450 (7.8) |

| HER2-positive | 1 (1.8) | 69 (1.2) |

| NA | 2 (3.5) | 61 (1.0) |

| Setting | ||

| Adjuvant | 26 (45.6) | 3131 (54.2) |

| Neoadjuvant | 23 (40.3) | 1601 (27.9) |

| Neoadjuvant and adjuvant | 8 (14.0) | 997 (17.5) |

| Type of treatment | ||

| ChT | 20 (35.1) | 1425 (24.0) |

| ET + ChT | 14 (24.6) | 2013 (34.8) |

| ET | 3 (5.3) | 270 (4.7) |

| ICI ± ChT | 1 (1.8) | 141 (2.4) |

| PARPi ± other | 1 (1.8) | 38 (0.7) |

| Other | 9 (15.8) | 897 (15.5) |

| NA | 9 (15.8) | 995 (17.2) |

Of the 57 studies included in the systematic review, 42 provided sufficient data for the meta-analysis.

ChT, chemotherapy; ET, endocrine therapy; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NA, not available; PARPi, poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Figure 1.

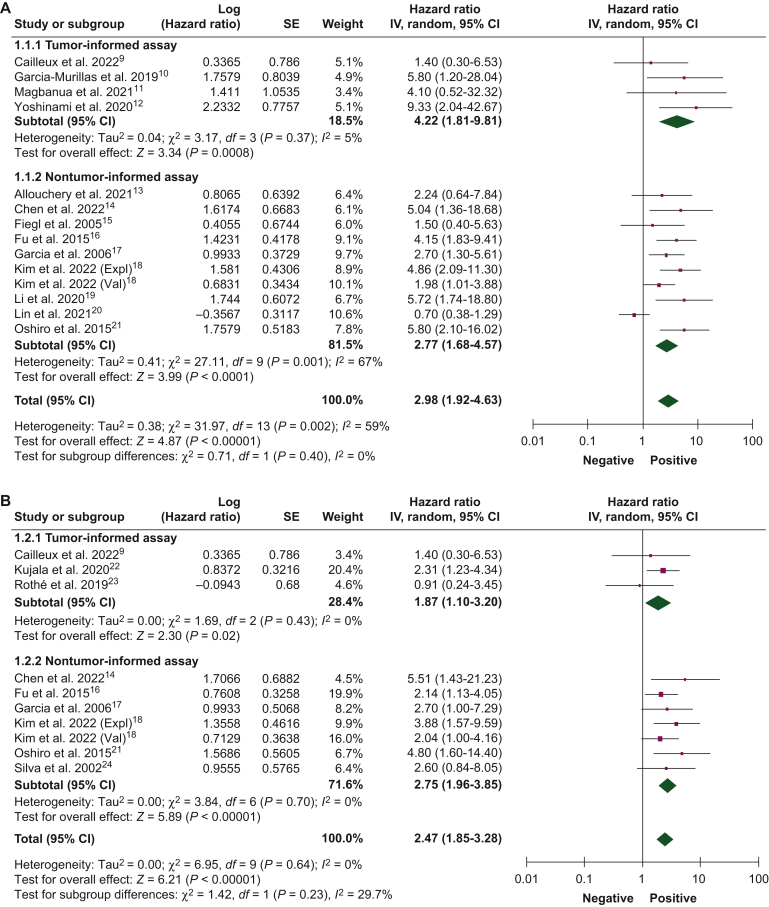

Association of circulating tumor DNA detection at baseline with disease-free survival.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate analyses, and overall survival, (C) univariate and (D) multivariate analyses, using tumor-informed and non tumor-informed assays.

CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

Figure 2.

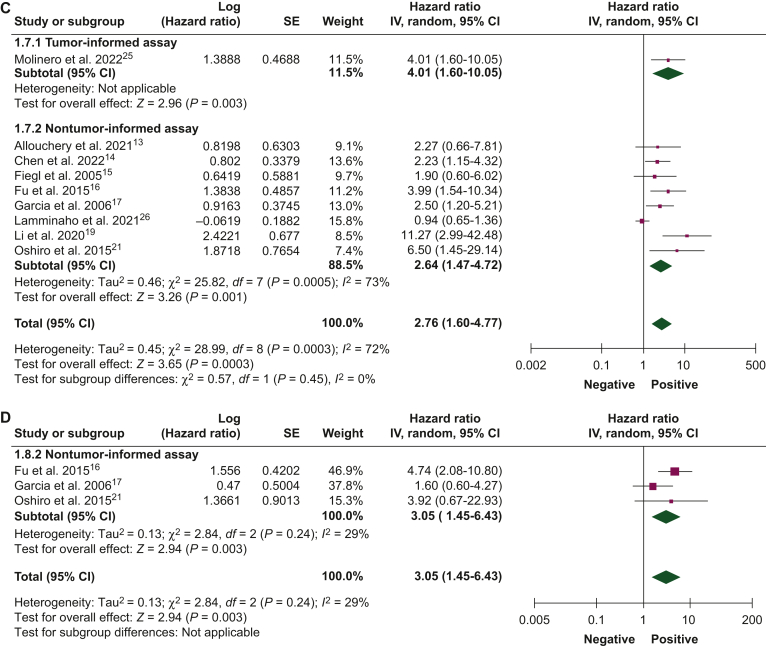

Association of circulating tumor DNA detection after neoadjuvant therapy with disease-free survival.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate analyses, and overall survival, (C) univariate and (D) multivariate analyses, using tumor-informed and non tumor-informed assays.

CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

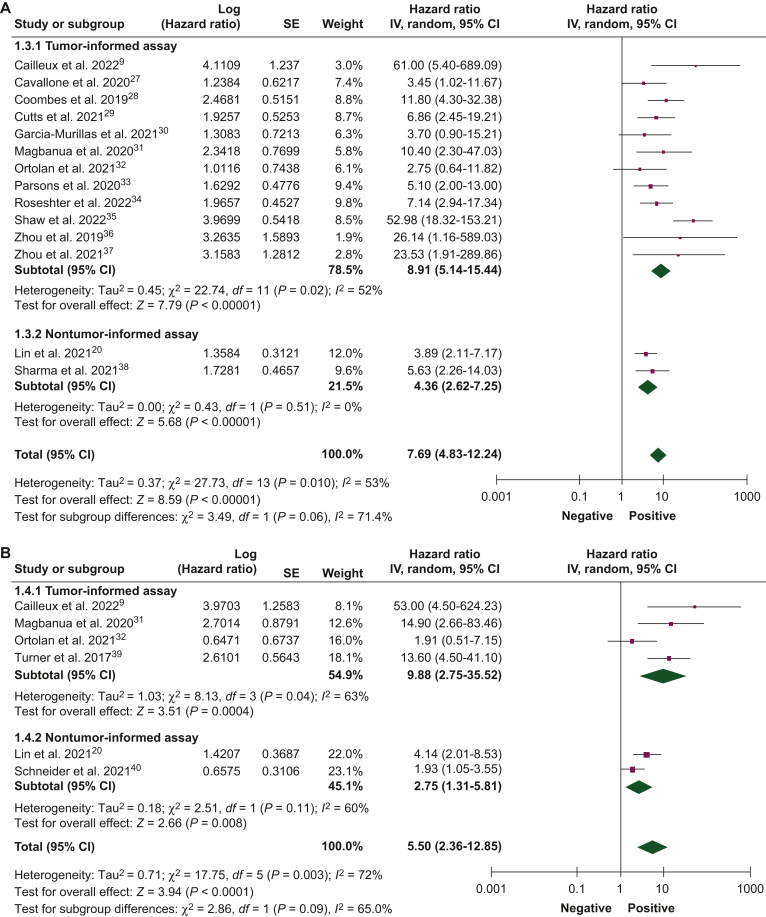

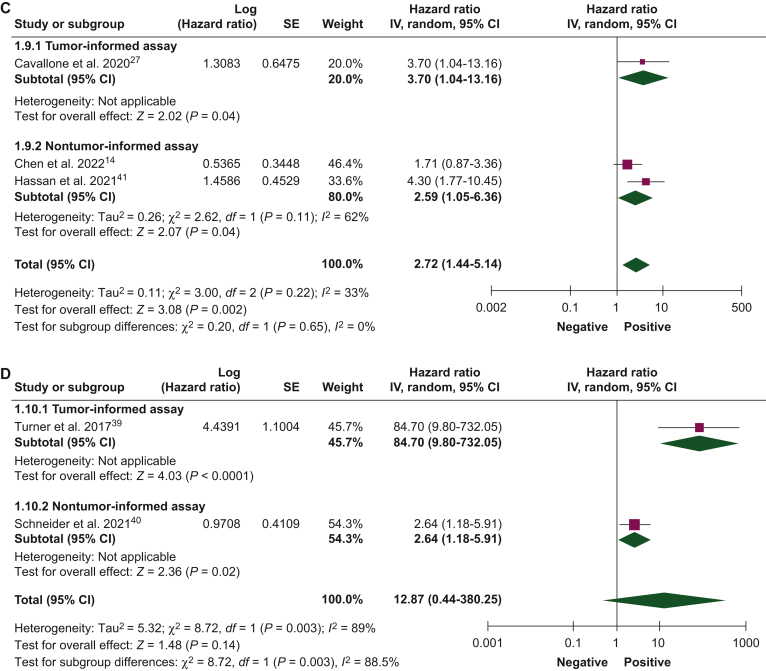

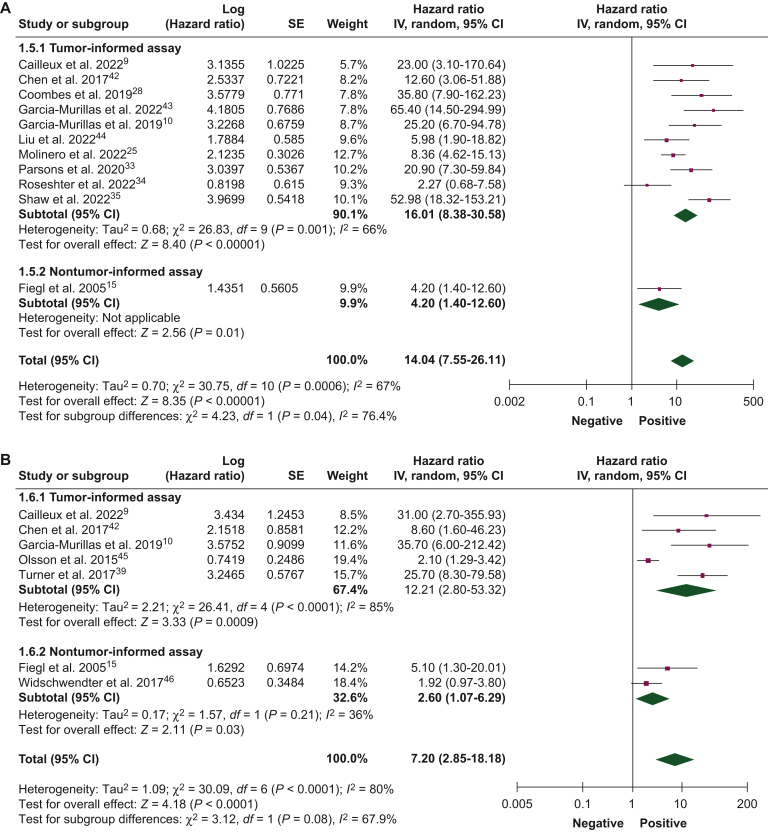

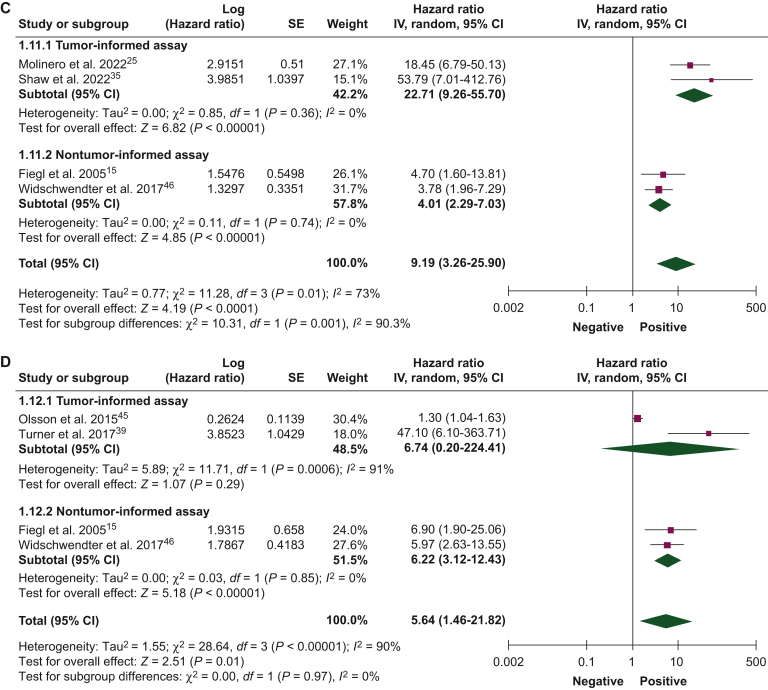

Figure 3.

Association of circulating tumor DNA detection during follow-up with disease-free survival.42, 43, 44, 45, 46 (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate analyses, and overall survival, (C) univariate and (D) multivariate analyses, using tumor-informed and non tumor-informed assays.

CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; SE, standard error.

ctDNA detection at baseline

The association between ctDNA detection at baseline with DFS and OS was reported by 17 studies (N = 2192 patients) and 9 studies (N = 1457 patients), respectively. ctDNA detection at baseline was associated with worse DFS in both univariate (HR 2.98, 95% CI 1.92-4.63) and multivariate (HR 2.47, 95% CI 1.85-3.28) analyses. Similar results were obtained when analyzing studies using tumor-informed and non tumor-informed assays, both in univariate and in multivariate analyses (Figure 1A and B). An increased risk of death was observed when ctDNA was detected at baseline in both univariate (HR 2.76, 95% CI 1.60-4.77) and multivariate (HR 3.05, 95% CI 1.45-6.43) analyses (Figure 1C and D). Table 2 summarizes the association between ctDNA detection at different timepoints and survival outcomes.

Table 2.

Association of circulating tumor DNA detection at different timepoints with survival outcomes

| Timepoint | Endpoint | Number of studies (number of patients) | HR (95% CI) | Tumor informed, HR (95% CI) | Non tumor-informed, HR (95% CI) | Overall HR, (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | DFS | 17 (2192) | Univariate | 4.22 (1.81-9.81) | 2.77 (1.68-4.57) | 2.98 (1.92-4.63) |

| Multivariate | 1.87 (1.10-3.20) | 2.75 (1.96-3.85) | 2.47 (1.85-3.28) | |||

| OS | 9 (1457) | Univariate | 4.01 (1.60-10.05) | 2.64 (1.47-4.72) | 2.76 (1.60-4.77) | |

| Multivariate | — | 3.05 (1.45-6.43) | 3.05 (1.45-6.43) | |||

| After neoadjuvant therapy | DFS | 16 (1122) | Univariate | 8.91 (5.14-15.44) | 4.36 (2.62-7.25) | 7.69 (4.83-12.24) |

| Multivariate | 9.88 (2.75-35.52) | 2.75 (1.31-5.81) | 5.50 (2.36-12.85) | |||

| OS | 5 (325) | Univariate | 3.70 (1.04-13.16) | 2.59 (1.05-6.36) | 2.72 (1.44-5.14) | |

| Multivariate | 84.70 (9.80-732.05) | 2.64 (1.18-5.91) | 12.87 (0.44-380.25) | |||

| Follow-up period | DFS | 14 (1809) | Univariate | 16.01 (8.38-30.58) | 4.20 (1.40-12.60) | 14.04 (7.55-26.11) |

| Multivariate | 12.21 (2.80-53.32) | 2.60 (1.07-6.29) | 7.20 (2.85-18.18) | |||

| OS | 6 (984) | Univariate | 22.71 (9.26-55.70) | 4.01 (2.29-7.03) | 9.19 (3.26-25.90) | |

| Multivariate | 6.74 (0.20-224.41) | 6.22 (3.12-12.43) | 5.64 (1.46-21.82) |

CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

ctDNA detection after neoadjuvant therapy

The association between ctDNA detection after neoadjuvant therapy and DFS and OS was reported by 16 studies (1122 patients) and 5 studies (325 patients), respectively. ctDNA detection after neoadjuvant therapy was associated with an increased risk of relapse in both univariate (HR 7.69, 95% CI 4.83-12.24) and multivariate analyses (HR 5.50, 95% CI 2.36-12.85). Pooled HR of studies that used tumor-informed assays were numerically higher than those that used non tumor-informed assays in univariate and multivariate analyses (Figure 2A and B). ctDNA detection was associated with worse DFS when measured either before (HR 3.45, 95% CI 1.82-6.56) or after surgery (HR 9.55, 95% CI 2.13-42.87) and the pooled HRs were numerically higher when ctDNA was collected after surgery in both univariate and multivariate analyses (Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102390). ctDNA detection after neoadjuvant therapy was associated with worse OS in univariate (HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.44-5.14) and multivariate analyses (HR 12.87, 95% CI 0.44-380.25; Figure 2C and D). Pooled HRs were numerically higher when ctDNA was detected at the end of neoadjuvant therapy than at baseline.

ctDNA detection during the follow-up period

The association between ctDNA detection during the follow-up period and DFS and OS was reported by 14 studies (1809 patients) and 6 studies (984 patients), respectively. The presence of ctDNA during follow-up was associated with worse DFS in univariate (HR 14.04, 95% CI 7.55-26.11) and multivariate analyses (HR 7.20, 95% CI 2.85-6.29; Figures 3A and B). Similarly, patients with ctDNA detection during follow-up experienced worse OS in univariate (HR 9.19, 95% CI 3.26-25.90) and multivariate analyses (HR 5.64, 95% CI 1.46-21.82; Figure 3C and D). Pooled HRs were numerically higher when ctDNA was detected during the follow-up period than at baseline. In univariate and multivariate analyses for DFS and OS, pooled HRs were numerically higher for tumor-informed than for noninformed assays.

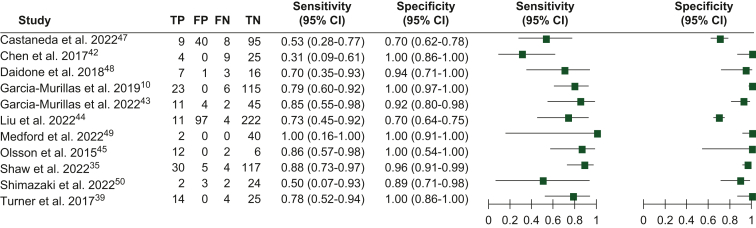

Sensitivity, specificity, and lead time

Eleven studies, comprising 1043 patients, provided data on ctDNA detection during follow-up after completing treatment with curative intent. True-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative rates were derived from these studies to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of ctDNA detection for the diagnosis of BC relapse.

The sensitivity of ctDNA ranged from 0.31 to 1.00 (0.31-1.00 for studies using tumor-informed assays and 0.50-0.53 for non tumor-informed assays). The specificity ranged from 0.70 to 1.00 (0.70-1.00 for studies using tumor-informed assays and 0.70-0.89 for non tumor-informed assays; Figure 4). Fourteen studies, including data from 1415 patients, reported data on the time elapsed between the first ctDNA detection and the diagnosis of clinical/radiological relapse. The mean lead time to radiological recurrence was 10.81 months (range 0-58.9 months).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection for the diagnosis of overt recurrent disease.47, 48, 49, 50

CI, confidence interval; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

Discussion

This is the most extensive systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between ctDNA detection and clinical outcomes in patients with operable BC. In contrast to previous reports,51,52 we assessed a remarkable sixfold increase in the number of included studies, and we included both patients undergoing neoadjuvant and patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Our findings demonstrate that ctDNA detection at any stage during operable BC is associated with an increased risk of relapse and mortality. This risk is particularly elevated when ctDNA detection occurs after neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, using tumor-informed assays. Moreover, ctDNA precedes the diagnosis of overt metastases by an average of 11 months, with a specificity of up to 100%.

In BC, ctDNA has become part of metastatic disease management, serving as a screening method for detecting molecular alterations to assign specific therapies (e.g. PIK3CA mutations, ESR1 mutations, microsatellite instability, NTRK fusions, and ERBB2 amplifications).4 As a pioneer study showed that ctDNA is associated with an increased risk of relapse when detected at baseline or during follow-up,53 numerous subsequent studies were conducted, most of which included retrospective cohorts, including all subtypes of non metastatic BC, with various ctDNA methodologies and time schedules. In this context, the present meta-analysis adds value by demonstrating, through both univariate and multivariate analyses, that patients with BC with detectable ctDNA consistently have a worse prognosis.

The risk associated with detectable ctDNA increases over time, as post-treatment ctDNA detection is numerically more than two times as detrimental as baseline ctDNA, emphasizing the value of longitudinal ctDNA assessments. Indeed, while detection of ctDNA at diagnosis provides some important prognostic information, its continued positivity at subsequent timepoints (i.e. absence of ctDNA clearance) likely reflects some degree of treatment resistance. Importantly, the value of ctDNA detection after neoadjuvant treatment appears to be maintained even when considering other major prognostic factors, such as the residual cancer burden.54

ctDNA detection after treatment with curative intent anticipates overt recurrent disease with a specificity of up to 100%. However, the implementation of this information for modifying the BC course raises several considerations. First, the timing of ctDNA assessment during follow-up varied among the studies. Second, due to the retrospective nature of pooled studies, some patients with positive ctDNA results might have omitted imaging assessments. As a result, it is uncertain whether ctDNA detected during follow-up is indicative of minimal residual disease or rather of asymptomatic metastases not yet diagnosed. An illustrative example of this has been recently offered by the TRAK TN study. In this trial, out of 161 patients with triple-negative BC undergoing ctDNA surveillance, 44 (27%) had ctDNA detection at 12 months. Interestingly, at the time of ctDNA detection, 72% (23/32) of patients already had metastases detected on imaging.55 Lastly, the window of time that ctDNA offers for intervention—a maximum of 11 months—and our ability to modify the natural course of the disease are uncertain. It remains unclear whether ctDNA detection allows for therapeutic interventions that can significantly alter disease outcomes. In this context, several ongoing studies are focusing on the use of ctDNA to guide interventions, including LEADER (NCT03285412), TRAK-ER (NCT04985266), and DARE (NCT04567420), which aim to assess whether the addition of a CDK4/6 inhibitor to endocrine therapy may reduce the risk of recurrence in patients with hormone receptor-positive BC who have a ctDNA detection in the adjuvant period. The MiRaDoR (NCT05708235) is a proof-of-concept study evaluating treatment efficacy by monitoring minimal residual disease using ctDNA in patients with luminal-like early BC and offers treatment with either salvage endocrine therapy alone or its combination with CDK4/6 or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors.

There is still no consensus on the ideal strategy for detecting ctDNA in patients with early BC.4 Tumor-agnostic (non tumor-informed) assays are developed without prior knowledge of tumor characteristics, whereas tumor-informed assays track key mutations previously identified in tumor tissue sequencing.4 While the former has the potential advantage of detecting acquired alterations, not present in the original tumor, the latter may have greater sensitivity for detecting already known mutations.4 In our study, patients with ctDNA detected by tumor-informed assays were at a numerically higher risk of recurrence and death compared with non tumor-informed assays. Although head-to-head comparisons between the two strategies are scarce, Santonja et al.56 compared the detection of ctDNA using different tumor-informed and non tumor-informed assays designed to detect somatic copy-number aberrations, single-nucleotide variants, and/or structural variants, by multiplex PCR, hybrid capture, and different depths of whole-genome sequencing in patients with early and advanced BC. Indeed, in the overall population, including patients with early and metastatic disease, the investigators demonstrated highly concordant results between both types of assays.56 In line with our findings, tumor-informed assays were more sensitive at low concentrations of ctDNA,56 as is often the case in patients with localized disease.57 Tumor-informed ctDNA assays have also been shown to outperform non tumor-informed methods in ctDNA studies conducted in other cancer types.58

Our results should be analyzed considering some limitations, including the heterogeneity of studies regarding ctDNA methodologies, populations, tumor characteristics, and timing of ctDNA evaluation. Analyzes according to BC subtypes were not possible due to a lack of data for each specific subtype. The high statistical heterogeneity found in some of our analyses was probably due to the high clinical diversity and methodological heterogeneity between studies, which was minimized using random effects models. The broad definition we used for DFS, accepting the definitions used in different studies and including relapse-free survival, event-free survival, and distant disease-free survival, hindered the harmonization of endpoints because these are not completely interchangeable. Our decision to evaluate the ctDNA result in a binary way prevented the evaluation of other factors that may be important prognostic determinants such as quantitative ctDNA levels and the dynamics of ctDNA clearance.

Conclusion

The detection of ctDNA in patients with operable BC is associated with a higher risk of relapse and death, particularly with the use of tumor-informed assays and in case of ctDNA detection after local and systemic treatments. The high specificity and the lead time between ctDNA detection during follow-up after treatment with curative intent hold the potential for designing risk-adapted treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Lombardy Region Italy [grant agreement number RR33] as part of the project ‘I controlli periodici (follow-up) dopo la diagnosi e le terapie in pazienti liberi da malattia e asintomatici: verso una personalizzazione delle strategie di follow-up’.

Disclosure

GNM reports meeting/travel grants from AstraZeneca. EA reports consultancy fees/honoraria from Eli Lilly, Sandoz, and AstraZeneca; research grant to the institution from Gilead; meeting/travel grants from Novartis, Roche, Eli Lilly, Genetic, Istituto Gentili, Daiichi Sankyo, and AstraZeneca (all outside the submitted work). DMB reports full time employment at European Society for Medical Oncology since September 1, 2023; speaker’s engagement from Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca; participation as medical research fellow in research studies with institutionally funded by Eli Lilly, Novartis, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd to Institut Jules Bordet; non-financial interest as member of the board of directors for Associaҫão de Investigaҫão e Ciudados de Suporte em Oncologia; non-remunerated prior leadership role as Portuguese Young Oncologists Committee Chair from Sociedade Portuguesa de Oncologia (all outside the submitted work). ALC reports leadership role at Eisai, Celgene, Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, and MSD; intellectual property for MEDSIR; a consulting role for Lilly, Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Pierre-Fabre, Exact Sciences, Seagen, and GSK; to be part of the speaker bureau for Lilly, AstraZeneca, and MSD; to receive research funding from Pfizer, Roche, Foundation Medicine, Exact Sciences, Pierre-Fabre, and Agendia; and travel compensation from Roche, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. JC reports consulting/advisor role for Roche, Celgene, Cellestia, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, Erytech, Athenex, Polyphor, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, GSK, Leuko, Bioasis, Clovis Oncology, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ellipses, HiberCell, BioInvent, GEMoaB, Gilead, Menarini, Zymeworks, Reveal Genomics, Expres2ion Biotechnologies, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and AbbVie; honoraria from Roche, Novartis, Celgene, Eisai, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca; research funding to the institution from Roche, Ariad pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Baxalta GMBH/Servier Affaires, Bayer healthcare, Eisai, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Guardant Health, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, PIQUR Therapeutics, IQVIA, and Queen Mary University of London; stocks from MAJ3 Capital and Leuko (relative); travel, accommodation, and other expenses covered by Roche, Novartis, Eisai, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Gilead, and Merck Sharp & Dohme; patents ‘Pharmaceutical Combinations of A Pi3k Inhibitor And A Microtubule Destabilizing Agent’—Javier Cortés Castán, Alejandro Piris Giménez, Violeta Serra Elizalde, WO 2014/199294 A (issued) and ‘Her2 as a predictor of response to dual HER2 blockade in the absence of cytotoxic therapy’—Aleix Prat, Antonio Llombart, Javier Cortés, US 2019/ 0338368 A1 (licensed). MI reports honoraria from Novartis and Seattle Genetics; research support to the institution from Natera Inc, Inivata, Roche, and Pfizer; and travel grants from Roche and Gilead. GP reports being part of the advisory board/speaker bureau for Roche, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Illumina, and ADS Biotech; and grants from Candriam and Thermo Fisher. EA reports honoraria and/or being part of the advisory board for Roche/GNE, Novartis, Seagen, Zodiac, Libbs, Pierre Fabre, Lilly, and Astra-Zeneca; travel grants from Roche/GNE and AstraZeneca; research grant to the institution from Roche/GNE, Astra-Zeneca, and GSK/Novartis. SDC reports being on the speaker’s bureau for AstraZeneca; and on the advisory board for Pierre-Fabre, IQVIA, and MEDSIR. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

†Present address: Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, USA.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohler B.A., Sherman R.L., Howlader N., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv048. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignatiadis M., Sledge G.W., Jeffrey S.S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic — implementation issues and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):297–312. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascual J., Attard G., Bidard F.C., et al. ESMO recommendations on the use of circulating tumour DNA assays for patients with cancer: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2022;33(8):750–768. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.05.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein H.J., DeMichele A., Somerfield M.R., Henry N.L. Biomarker Testing and Endocrine and Targeted Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer Expert Panels. Testing for ESR1 mutations to guide therapy for hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer: ASCO guideline rapid recommendation update. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2023;41(18):3423–3425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden J.A., van der Windt D.A., Cartwright J.L., Côté P., Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.4.1. revman.cochrane.org The Cochrane Collaboration. Available at. Accessed February 29, 2024.

- 9.Cailleux F., Agostinetto E., Lambertini M., et al. Circulating tumor DNA after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer is associated with disease relapse. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;(6) doi: 10.1200/PO.22.00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Murillas I., Chopra N., Comino-Méndez I., et al. Assessment of molecular relapse detection in early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):1473–1478. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magbanua M.J.M., Swigart L.B., Wu H.T., et al. Circulating tumor DNA in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer reflects response and survival. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2021;32(2):229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshinami T., Kagara N., Motooka D., et al. Detection of ctDNA with personalized molecular barcode NGS and its clinical significance in patients with early breast cancer. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(8):100787. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allouchery V., Perdrix A., Calbrix C., et al. Circulating PIK3CA mutation detection at diagnosis in non-metastatic inflammatory breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):24041. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02643-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X., Lin Y., Jiang Z., et al. HER2 copy number quantification in primary tumor and cell-free DNA provides additional prognostic information in HER2 positive early breast cancer. The Breast. 2022;62:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiegl H., Millinger S., Mueller-Holzner E., et al. Circulating tumor-specific DNA: a marker for monitoring efficacy of adjuvant therapy in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1141–1145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu D., Ren C., Tan H., et al. Sox17 promoter methylation in plasma DNA is associated with poor survival and can be used as a prognostic factor in breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(11):e637. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia J.M., Garcia V., Silva J., et al. Extracellular tumor DNA in plasma and overall survival in breast cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45(7):692–701. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M., Kim G., Kim S.G., et al. Copy number aberration burden on circulating tumor DNA predicts recurrence risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: posthoc analysis of phase III PEARLY trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S., Lai H., Liu J., et al. Circulating tumor DNA predicts the response and prognosis in patients with early breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020:4. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin P.H., Wang M.Y., Lo C., et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a predictive marker of recurrence for patients with stage ii-iii breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:736769. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.736769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshiro C., Kagara N., Naoi Y., et al. PIK3CA mutations in serum DNA are predictive of recurrence in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150(2):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kujala J., Hartikainen J.M., Tengström M., Sironen R., Kosma V.M., Mannermaa A. High mutation burden of circulating cell-free DNA in early-stage breast cancer patients is associated with a poor relapse-free survival. Cancer Med. 2020;9(16):5922–5931. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothé F., Silva M.J., Venet D., et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in HER2-amplified breast cancer: a translational research substudy of the NeoALTTO phase III Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(12):3581–3588. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva J.M., Silva J., Sanchez A., et al. Tumor DNA in plasma at diagnosis of breast cancer patients is a valuable predictor of disease-free survival. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2002;8(12):3761–3766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molinero L., Renner D., Wu H.T., et al. ctDNA prognosis in adjuvant triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82(12) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamminaho M., Kujala J., Peltonen H., Tengström M., Kosma V.M., Mannermaa A. High cell-free DNA integrity is associated with poor breast cancer survival. Cancers. 2021;13(18) doi: 10.3390/cancers13184679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavallone L., Aguilar-Mahecha A., Lafleur J., et al. Prognostic and predictive value of circulating tumor DNA during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14704. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71236-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coombes RC, Page K, Salari R, et al. Personalized detection of circulating tumor DNA antedates breast cancer metastatic recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(14):4255 LP - 4263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cutts RJ, Coakley M, Garcia-Murillas I, et al. Molecular residual disease detection in early stage breast cancer with a personalized sequencing approach. Cancer Res. 2021;81(13 Suppl).

- 30.Garcia-Murillas I, Cutts RJ, Ulrich L, et al. Detection of ctDNA following surgery predicts relapse in breast cancer patients receiving primary surgery. Cancer Res. 2022;82(4 Suppl).

- 31.Magbanua M.J.M., Brown-Swigart L., Hirst G., et al. Personalized monitoring of circulating tumor DNA during neoadjuvant therapy in high-risk early stage breast cancer reflects response and risk of metastatic recurrence. Cancer Res. 2020;80(4) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortolan E., Appierto V., Silvestri M., et al. Blood-based genomics of triple-negative breast cancer progression in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. ESMO Open. 2021;6(2):100086. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons H.A., Rhoades J., Reed S.C., et al. Sensitive Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in Patients Treated for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2556–2564. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roseshter T, Klemantovich A, Cavallone L, et al. Abstract P2-11-26: The prognostic role of circulating tumor DNA after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer with residual tumor. Cancer Res. 2023;83(5_Supplement):P2-11-26.

- 35.Shaw J., Page K., Ambasger B., et al. Serial postoperative ctDNA monitoring of breast cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y., Xu Y., Gong Y., et al. Serial circulating tumor DNA analysis indicating the efficacy and prognosis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019:37. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y., Xu Y., Wang C., et al. Serial circulating tumor DNA identification associated with the efficacy and prognosis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;188(3):661–673. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06247-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma P, Stecklein SR, Kimler BF, et al. Impact of post-treatment ctDNA and residual cancer burden (RCB) on outcomes in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and residual disease. Cancer Res. 2022;82(4 Suppl).

- 39.Turner N.C., Garcia-Murillas I., Chopra N., et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis to predict relapse and overall survival in early breast cancer-Longer follow-up of a proof-of-principle study. Cancer Res. 2017;77(4) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider B.P., Jiang G., Ballinger T.J., et al. BRE12-158: A postneoadjuvant, randomized phase II trial of personalized therapy versus treatment of physician’s choice for patients with residual triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2021:JCO2101657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassan F., O’Leary D.P., Ita M., Corrigan M., Wang J.H., Redmond H.P. Perioperative liquid biopsy may help predict the risk of recurrence in breast cancer patients. Br J Surg. 2021;108(Suppl 1):i22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y.H., Hancock B.A., Solzak J.P., et al. Next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA to predict recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:24. doi: 10.1038/s41523-017-0028-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Murillas I, Walsh-Crestani G, Phillips E, et al. Abstract P5-05-01: Personalized Cancer Monitoring (PCM): a novel ctDNA tool to detect molecular residual disease in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83(5_Supplement):P5-05-01.

- 44.Liu Q, Wu M, Li S, et al. Abstract P4-02-07: A large real-world study of circulating tumor DNA in early breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2023;83(5_Supplement):P4-02-07.

- 45.Olsson E., Winter C., George A., et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(8):1034–1047. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widschwendter M., Evans I., Jones A., et al. Methylation patterns in serum DNA for early identification of disseminated breast cancer. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0499-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castaneda C.A., Castillo M., Bernabe L.A., et al. Association between PIK3CA mutations in blood and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in peruvian breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2022;23(10):3331–3337. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.10.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daidone M.G., Di Cosimo S., Veneroni S., et al. Circulating tumor DNA detection anticipates disease recurrence in early stage breast cancer: A pilot study generating an observational confirmatory trial. Cancer Res. 2018;78(4) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medford AJ, Scarpetti L, Niemierko A, et al. Abstract PD17-03: Cell-free DNA monitoring in a phase II study of adjuvant endocrine therapy with CDK 4/6 inhibitor ribociclib for localized HR+/HER2- breast cancer (LEADER). Cancer Res. 2023;83(5_Supplement):PD17-03.

- 50.Shimazaki A., Kubo M., Kurata K., et al. CCND1 Copy number variation in circulating tumor DNA from luminal B breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(8):4071–4077. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cullinane C., Fleming C., O’Leary D.P., et al. Association of circulating tumor DNA with disease-free survival in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papakonstantinou A., Gonzalez N.S., Pimentel I., et al. Prognostic value of ctDNA detection in patients with early breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;104 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Murillas I., Chopra N., Comino-Méndez I., et al. Assessment of molecular relapse detection in early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):1473–1478. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magbanua M.J.M., Brown Swigart L., Ahmed Z., et al. Clinical significance and biology of circulating tumor DNA in high-risk early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(6):1091–1102.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner N.C., Swift C., Jenkins B., et al. Results of the c-TRAK TN trial: a clinical trial utilising ctDNA mutation tracking to detect molecular residual disease and trigger intervention in patients with moderate- and high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(2):200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santonja A., Cooper W.N., Eldridge M.D., et al. Comparison of tumor-informed and tumor-naïve sequencing assays for ctDNA detection in breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med. 2023;15(6) doi: 10.15252/emmm.202216505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bettegowda C., Sausen M., Leary R.J., et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan H.T., Nagayama S., Otaki M., et al. Tumor-informed or tumor-agnostic circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for risk of recurrence in resected colorectal cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2023;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1055968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.