Summary

Background

Knowledge of gestational age (GA) is key in clinical management of individual obstetric patients, and critical to be able to calculate rates of preterm birth and small for GA at a population level. Currently, the gold standard for pregnancy dating is measurement of the fetal crown rump length at 11–14 weeks of gestation. However, this is not possible for women first presenting in later pregnancy, or in settings where routine ultrasound is not available. A reliable, cheap and easy to measure GA-dependent biomarker would provide an important breakthrough in estimating the age of pregnancy. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the accuracy of prenatal and postnatal biomarkers for estimating gestational age (GA).

Methods

Systematic review prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020167727) and reported in accordance with the PRISMA-DTA. Medline, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, and other databases were searched from inception until September 2023 for cohort or cross-sectional studies that reported on the accuracy of prenatal and postnatal biomarkers for estimating GA. In addition, we searched Google Scholar and screened proceedings of relevant conferences and reference lists of identified studies and relevant reviews. There were no language or date restrictions. Pooled coefficients of correlation and root mean square error (RMSE, average deviation in weeks between the GA estimated by the biomarker and that estimated by the gold standard method) were calculated. The risk of bias in each included study was also assessed.

Findings

Thirty-nine studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria: 20 studies (2,050 women) assessed prenatal biomarkers (placental hormones, metabolomic profiles, proteomics, cell-free RNA transcripts, and exon-level gene expression), and 19 (1,738,652 newborns) assessed postnatal biomarkers (metabolomic profiles, DNA methylation profiles, and fetal haematological components). Among the prenatal biomarkers assessed, human chorionic gonadotrophin measured in maternal serum between 4 and 9 weeks of gestation showed the highest correlation with the reference standard GA, with a pooled coefficient of correlation of 0.88. Among the postnatal biomarkers assessed, metabolomic profiling from newborn blood spots provided the most accurate estimate of GA, with a pooled RMSE of 1.03 weeks across all GAs. It performed best for term infants with a slightly reduced accuracy for preterm or small for GA infants. The pooled RMSEs for metabolomic profiling and DNA methylation profile from cord blood samples were 1.57 and 1.60 weeks, respectively.

Interpretation

We identified no antenatal biomarkers that accurately predict GA over a wide window of pregnancy. Postnatally, metabolomic profiling from newborn blood spot provides an accurate estimate of GA, however, as this is known only after birth it is not useful to guide antenatal care. Further prenatal studies are needed to identify biomarkers that can be used in isolation, as part of a biomarker panel, or in combination with other clinical methods to narrow prediction intervals of GA estimation.

Funding

The research was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-000368). ATP is supported by the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre with funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health, or the Department of Biotechnology. The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, in writing the paper or the decision to submit for publication.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Gestational age, Screening, Growth, Preterm, Diagnostic accuracy, Metabolomics, Hormones

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Gestational age (GA) estimation is essential for optimal maternity care, but is often inaccurate, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Existing methods, such as last menstrual period (LMP), symphysis-fundal height (SFH), and late trimester ultrasound have limitations, including inaccuracy and the gold standard, first-trimester ultrasound, is often unavailable in LMICs. As a result, GA is unknown in a large proportion of women worldwide. This review explores potential biomarkers to enhance GA estimation.

A comprehensive search of databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, LILACS, medRxiv, Science Citation Index and other databases was conducted with no language restrictions from inception to September 15, 2023, employing terms related to GA, estimation, and biomarkers. The inclusion criteria encompassed studies reporting biomarker accuracy during the antenatal or immediate postnatal period, using ultrasound or LMP as comparators, and involving healthy mothers/newborns with relevant statistical assessments.

Added value of this study

This is the first systematic review of biomarkers for GA estimation, identifying promising candidates that could be useful in settings without early ultrasound access. Metabolomic profiling from heel-prick blood spot emerges as the most accurate, exhibiting a pooled RMSE of 1.03 weeks across all GAs, with optimal performance in term infants. Other biomarkers, such as cord blood metabolomic profiling and DNA methylation, exhibit lesser accuracy compared to newborn blood spot metabolomic profiling. During the prenatal period, hCG measured between 4 and 9 weeks had the highest correlation with the reference standard GA among the placental biomarkers assessed; however, this correlation was less accurate when assessed for a wider GA window. Two small studies suggested that maternal metabolomic profiling had low accuracy to estimate GA with a pooled RMSE of 2.90 weeks.

Implications of all the available evidence

There are at present no antenatal biomarkers that accurately predict GA over a wide window of pregnancy. Postnatal biomarkers appear more promising but are not available to guide antenatal care (such as who should receive magnesium sulphate for neuroprotection or steroids for lung maturation). Although metabolomic profiling from newborn blood spot appears more accurate than from cord blood, acceptability must also be considered. Further studies are needed in biomarker discovery; and to compare the most promising of these biomarkers in terms of accuracy and cost as well as equipment and infrastructure required. These are important considerations as biomarkers are most likely to be beneficial in LMIC settings, where these are significant barriers to implementation.

Introduction

Accurate gestational age (GA) poses a significant global challenge, especially in Low- and Middle- Income Countries (LMICs). Recent research indicates that only 64 of 195 countries worldwide have national routine data to estimate preterm birth, meaning that estimates are heavily influenced by the lack of GA estimation.1 Relying on the reported last menstrual period (LMP) is often unreliable, due to inaccurate recall of dates, or irregular menstrual cycles, which is more common in breastfeeding women, those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or malnutrition.2 Although first trimester ultrasound scans are considered to be the gold standard for dating pregnancies,3,4 they are not commonly available in these settings at present, due to women presenting late for antenatal care.5 Later pregnancy dating using ultrasound biometry is much less accurate,6 and although novel tools have reduced this inaccuracy7,8 higher rates of inaccurate GA assessment remain an issue in the highest burden settings.

Accurate estimation of GA is crucial in obstetrics for multiple reasons. Firstly, at the level of the individual woman, it is essential for making obstetric decisions such as identifying patients who would benefit from interventions like steroids for fetal lung maturation9 or magnesium sulphate for neuroprotection10; interpreting diagnostic information such as malpresentation or a low lying placenta, which are only relevant near term. Secondly, at the level of the individual neonate, knowledge of GA is crucial to distinguish different types of small vulnerable newborns, i.e. babies that are small due to preterm birth or small for GA (SGA), ensuring they can receive appropriate care. Lastly, at the population level, knowledge of GA is essential to understand the prevalence of preterm birth as it is the leading cause of mortality in children under five years of age globally.11 This knowledge allows for targeted allocation of resources to improve outcomes.

Although estimating GA at birth through neonatal assessment is possible, this information is not available for prenatal care; and is often highly imprecise with estimates deviating by ±3 to 4 weeks from the gold standard.12 One way in which the assessment of GA may be improved is the use of biomarkers, such as those in maternal serum and urine, umbilical cord blood and neonatal heel prick testing. There would be an obvious benefit to an accurate, reliable and cost-effective biomarker that could estimate GA in this way. Therefore, our research question is what maternal or newborn biomarkers that assess GA exist. Several candidate biomarkers have been investigated, but to date no systematic evaluation of the accuracy of these biomarkers to estimate GA has been undertaken. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to identify, and determine the accuracy of, prenatal and postnatal biomarkers that have been proposed for the estimation of GA.

Methods

This systematic review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO identifier CRD42020167727) and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) statement.13

Literature search

To identify potentially eligible studies, we searched MEDLINE(OvidSP)[1946-present], EMBASE (OvidSP)[1974-present], CINAHL (EBSCOHost)[1982-present], LILACS https://www.globalindexmedicus.net/, medRxiv https://www.medrxiv.org/, and Science Citation Index (Web of Science Core Collection)[1900-present] from inception to 15th September 2023. The search included a combination of subject headings and textwords for “gestational age”, “estimation” and “biomarkers” (Appendix S1). There were no language or date restrictions. In addition, we searched Google Scholar and screened proceedings of relevant conferences and reference lists of identified studies and relevant reviews.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) cohort or cross-sectional studies that assessed the accuracy of biomarkers in women with healthy singleton pregnancies or in any newborns for estimating GA at any point during pregnancy or at birth, respectively; (2) the gold standard GA age used in the study was based on the best obstetrical estimate (last menstrual period, dating ultrasound or a combination of both); and (3) the study reported at least one statistic assessing correlation or agreement of GA estimation, or diagnostic accuracy.

Studies were excluded if: (1) they were case–control studies, case series or reports, editorials, comments, or reviews without original data; (2) the gold standard GA used in the study was based on neonatal physical and neurologic assessment or was not reported; (3) they did not report any statistics assessing correlation or agreement of GA estimation or diagnostic accuracy, or sufficient information to calculate them could not be retrieved; (4) they included pregnancies or newborns with specific pathologies. In cases of duplicate publication, we selected the most recent and complete versions and supplemented if additional information appeared in the other publications.

Assessment of risk of bias

The risk of bias in each included study was assessed independently by two authors (EB and AC-A) using a modified version of the QUADAS (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)-2 tool.14 Disagreements in risk of bias assessment were resolved through consensus. We evaluated five domains believed to be important for the quality of studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers for estimating GA. Each domain was scored as “low risk”, “high risk”, or “unclear risk” of bias. The domains evaluated and their interpretation, were as follows:

-

1.

Study design—“low risk of bias”: pregnant women or newborns consecutively or randomly selected and prospective cohort design; “high risk of bias”: convenience sampling (arbitrary or non-consecutive recruitment) or retrospective cohort design.

-

2.

Description of the biomarker—“low risk of bias”: the study report included a detailed description of the biomarker(s) assessed including sampling site, assay used, manufacturer of assay, GA at which the sample was collected (for prenatal biomarkers) and age at testing in hours after birth (for postnatal biomarkers), and frequency of testing; “high risk of bias”: if this information was not reported.

-

3.

Reference standard—“low risk of bias”: GA that was established by early ultrasound measurement of fetal crown-rump length (between 8+0 weeks and 13+6 weeks), or by the woman’s LMP corroborated by early ultrasound, or by the woman’s LMP that was in agreement (within 7 days) with ultrasound measurements performed later in the pregnancy, or by certain ovulation date. This last criterion was not included in the PROSPERO protocol but the reviewers subsequently agreed it was appropriate to consider a study as a low-risk of bias for this domain; “high risk of bias”: GA that was not established according to the previously mentioned parameters.

-

4.

Blinding—“low risk of bias”: GA based on biomarker(s) results was estimated without knowledge of the results of the “gold standard” GA; “high risk of bias”: GA based on biomarker(s) results was estimated with knowledge of the results of the “gold standard” GA. Our predefined protocol stated that an explicit statement that researchers were blind to the actual GA would render the method at low risk of bias. Nevertheless, upon review of studies we concluded that for very large studies, it would be very unlikely that researchers would estimate GA based on knowledge the “gold standard” estimate of GA, and we included this criterion retrospectively as low risk of bias.

-

5.

Inclusion of participants in the primary analysis—“low risk of bias”: if at least 90% of enrolled women/newborns in the study were included in the primary analysis; “high risk of bias”: if less than 90% of enrolled women/newborns in the study were included in the primary analysis.

If there was insufficient information available to make a judgment about the bias of a domain, then it was scored as “unclear risk of bias”.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (EB and AC-A) independently extracted data from each eligible study using a standardized data collection form. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and consensus. Information was extracted on study characteristics (first author’s name, date of publication, geographic location of the study, study design, recruitment of participants, time period for recruitment of participants, prospective or retrospective data collection, blinding, and completeness of follow up and reporting of withdrawals); participants characteristics (inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, and demographic characteristics); description of the biomarker(s) assessed (GA at sampling for prenatal biomarkers, age at testing in hours after birth for postnatal biomarkers, sampling site, frequency of test, analytical method used, cut-off values, biomarkers included in predictive models, and costs); reference standard used (definition of “gold standard” GA); outcomes (definition of outcomes); main findings of the study; and measures of diagnostic accuracy of biomarker(s) for estimating GA for the entire cohort and/or model development and validation subsets, and subgroups of participants (coefficient of correlation, coefficient of determination, standard error of estimation, root mean square error [RMSE], mean absolute error, proportion of mothers/infants with predicted GA within 1 and 2 weeks of GA estimated by the gold standard method, and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with 95% confidence interval (CI) to discriminate GA across a dichotomous preterm birth threshold).

Data synthesis

Studies that assessed prenatal biomarkers were grouped according to GA at which the biomarker was measured (4–10 weeks, 4–16 weeks, and all trimesters of pregnancy), whereas postnatal biomarkers were grouped according to sample site (neonate heel prick blood and cord blood). Meta-analyses were performed if at least two studies assessed the same biomarker(s) and reported similar measures of diagnostic accuracy for estimating GA. Data were synthesized in several ways.

First, we estimated pooled coefficients of correlation with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for prenatal biomarkers (human chorionic gonadotrophin, pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein, human placental lactogen, and metabolomic profile in maternal serum) according to GA at which the biomarker was measured, and for postnatal biomarkers (DNA methylation profile in cord blood) by using the Hedges-Olkin (a conventional summary meta-analysis with a Fisher Z transformation of the correlation coefficient)15 and Hunter-Schmidt (a weighted mean of the raw correlation coefficient)16 methods. In this systematic review, the correlation coefficient measures the strength of the linear relationship between the GA predicted by the biomarker and that estimated by the gold standard method. It varies between −1 and 1 with 0 indicating no linear relationship, +1 indicating a perfect positive linear relationship, and −1 indicating a perfect negative linear relationship.

Second, pooled RMSE (overall average deviation in weeks between the GA predicted/estimated by the biomarkers and that estimated by the gold standard method) with 95% CI was estimated for metabolomic profile in maternal serum, metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening. This was done for all infants, and for subgroups of infants with a GA ≥37 weeks and <37 weeks, and infants born SGA (birthweight below the 10th percentile for GA). DNA methylation profile in cord blood from RMSEs, SDs and sample sizes reported in each study.

Third, pooled proportions of infants with predicted GA within 1 and 2 weeks of GA estimated by the gold standard method were calculated for metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening (heel prick blood and cord blood). Percentages (95% CIs) in individual studies were logit transformed to obtain pooled proportions with 95% CIs. Pooled proportions were obtained for all infants and for subgroups of infants with a GA ≥37 weeks, <37 weeks, 32–36 weeks, and <32 weeks, and infants born SGA (birthweight below the 10th percentile for GA). Finally, the method described by Zhou et al.17 was used to calculate the pooled AUC with 95% CI for metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening to discriminate infants with a GA <34 weeks from those with a GA ≥34 weeks, and infants with a GA <37 weeks from those with a GA ≥37 weeks.

All meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model because we anticipated that there would be substantial heterogeneity between the results of the studies. The random effects model tends to give a more conservative estimate with wider 95% CI. Heterogeneity of the results among studies was evaluated by estimating the quantity І2,.18 A significant level of heterogeneity was defined as І2 ≥ 30%.18 We planned to explore potential sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup and sensitivity analyses and to assess publication and related biases by examining the symmetry of funnel plots using Deeks’ test19; however, most of these analyses were not performed given the small number of studies included in most meta-analyses performed.

Statistical analyses were performed by using StatsDirect (Version 3.3.5; StatsDirect Ltd, Merseyside, United Kingdom).

Ethics

As a systematic review, our study did not involve direct participation of human subjects and focused solely on previously published and publicly available data. It did not require institutional review board approval for this reason. The ethical principles governing this study adhere to the established guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses and was based on registration of the protocol, search and analysis strategy to enhance transparency and preclude selective reporting.

Role of the funding source

The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, in writing the paper or the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Selection, characteristics, and risk of bias of studies

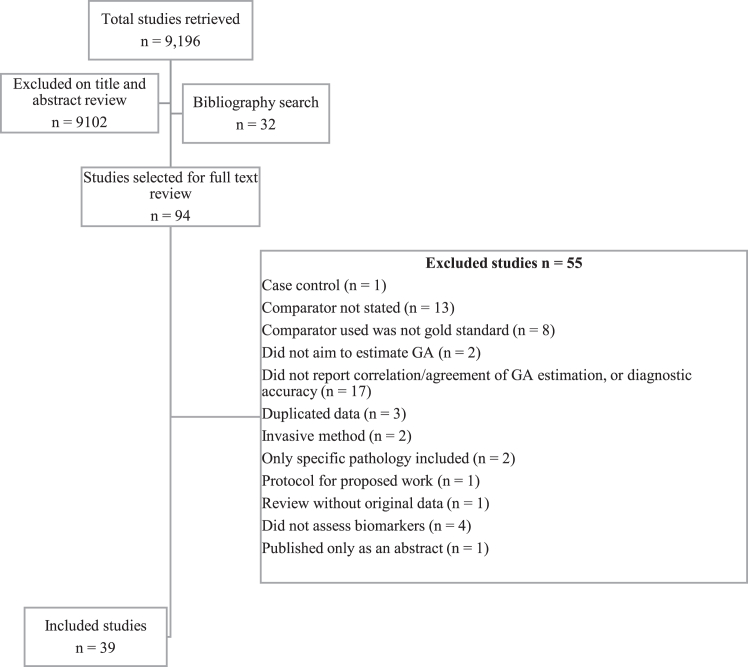

Our search returned 9,196 studies, of which 94 were selected for full text review. Of these, 55 were excluded based on the prespecified exclusion criteria discussed in Methods section (Fig. 1). References for excluded studies can be obtained from the authors upon request. The remaining 39 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 Twenty studies, including 2050 women, assessed prenatal biomarkers,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 and 19, including 1,738,652 newborns, assessed postnatal biomarkers.41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing screening process of studies in biomarkers review; adapted from PRISMA.20

The main characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review are presented in Table 1, Table 2. Among studies that assessed prenatal biomarkers, 14 evaluated placental hormones (human chorionic gonadotrophin [hCG], human placental lactogen [hPL], pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein [SP1] and placental protein-14),21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 three evaluated metabolomic profiles,37,38,40 and one each evaluated plasma proteomics,36 cell-free RNA [cfRNA] transcripts,35 and exon-level gene expression39 (Table 1). Most studies (95%) were conducted in high-income countries (United States, United Kingdom, and Denmark). Only one study was conducted in LMICs. Among studies that assessed postnatal biomarkers, 13 evaluated metabolomic profiles (Acyl-carnitine, amino acid, fatty acid, ceramide, ceramide 1-phosphate, galactosylceramide, phosphatidyl acid, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, cholesteryl ester, and sphingomyelin),42, 43, 44,47, 48, 49,51, 52, 53,55, 56, 57, 58 five evaluated genome methylation profiles (DNA methylation profiles),45,46,50,54,59 and one evaluated fetal haematological components (isoenzymes of erythrocytic carbonic anhydrase)41 (Table 2). Twelve (63%) studies were conducted in high-income countries and seven (37%) in LMICs.

Table 1.

Characteristics and main findings of included studies that assessed prenatal biomarkers for predicting gestational age.

| First author, year | Country (Region) | Design | Sample size | Biomarker(s) | Biological sample | Gestational age at testing | Reference standard | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peeters, 197621 | USA (Colorado) | Prospective cohort | 9 | hCG hPL |

Serum | 10–25 weeks | GA estimated by LMP | At 12–17 weeks of gestation, hCG combined with hPL provided an estimate of GA within ±9.4 days of that provided by LMP; at 12–15 weeks of gestation, hPL alone provided an estimate of GA within ±12.3 days of that provided by LMP. |

| Lagrew, 198322 | USA (Kentucky) | Unclear | 95 | hCG | Serum | 4–18.6 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Whittaker, 198323 | UK (Newcastle) | Prospective cohort | 35 | hCG hPL |

Serum | 3–20 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Ahmed, 198424 | UK (Aberdeen) | Prospective cohort | 34 | hCG SP1 |

Serum | 2–16.7 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Lagrew, 198425 | USA (Kentucky) | Prospective cohort | 15 | hCG | Serum | 4.1–8.6 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Westergaard, 198526 | Denmark (Odense) | Prospective cohort | 26 | hCG SP1 |

Serum | 4.3–8.6 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Ahmed, 198527 | UK (Aberdeen) | Prospective cohort | 56 | hCG SP1 |

Serum | <5 (N = 13) and 5–16 (N = 43) weeks | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Ahmed, 198628 | UK (Aberdeen) | Prospective cohort | 62 | SP1 | Serum | 5–16 weeks | GA estimated by LMP | When GA predicted by SP1 was greater than that estimated by LMP, the mean difference (SD) was 6.5 (5.8) days. When GA predicted by SP1 was lower than that estimated by LMP, the mean difference (SD) was 2.6 (1.4) days. |

| Bersinger, 198629 | UK (Aberdeen) | Prospective cohort | 139 | SP1 | Serum and urine | 4–16 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Chervenak, 198630 | USA (New York) | Retrospective cohort | 77 | hCG | Serum | 4.0–8.6 weeks | GA estimated by ovulation date | The average prediction error (gestational age estimated by ovulation date minus gestational age predicted by hCG) varied between 2.1 days (SD, 3.6) and 4.1 days (SD, 6.8) |

| Whittaker, 198731 | UK (Newcastle) | Prospective cohort | 585 | hPL | Serum | 6.3–18.9 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Thomson, 198832 | UK (Aberdeen) | Prospective cohort | 233 |

|

Serum | <16 weeks | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Johal, 199133 | UK (London) | Prospective cohort | 100 |

|

Serum | 5.7–11.6 weeks | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Larsen, 201334 | USA (multicity) | Prospective cohort | 178 | hCG | Urine | 0–8 weeks | GA estimated by ovulation date, LMP and ultrasound | The agreement between the GA based on the hCG concentration and that based on the ovulation day was 95.9% for a GA of 1–2 weeks, 93.4% for 2–3 weeks, and 95.2% for 3–8 weeks. |

| Ngo, 201835 | Denmark (Copenhagen) and USA (Pennsylvania and Birmingham) | Prospective cohort | 31 full-term pregnancies (Denmark) and 38 pregnancies at risk for preterm birth (USA) | Cell-free RNA transcripts | Serum | Second and third trimester | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Aghaeepour, 201836 | USA (Stanford) | Prospective cohort | 27 (17 in training cohort and 10 in validation cohort) | Proteomic profile | Plasma | 7-14, 15–20, and 24–32 weeks | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Sylvester, 202037 | USA (Stanford and Birmingham) | Retrospective cohort | 58 (36 in model development cohort and 22 in the validation cohort) | Metabolomic profilea | Serum | First, second and third trimester | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Liang, 202038 | Denmark | Prospective cohort | 38 (21 in discovery cohort, 9 in a first validation cohort, and 8 in a second validation cohort) | Metabolomic profileb | Plasma | Weekly, from 5 weeks to postpartum period | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Tarca, 202139 | United States | Prospective cohort | 133 | Exon-level gene expression | Whole blood | 8 to >37 weeks | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Contrepois, 202240 | Bangladesh, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Zambia (discovery cohort); United States (validation cohort) | Retrospective cohort | 119 (99 in discovery cohort and 20 in validation cohort) | Metabolomic profilec | Urine | 8–19 weeks | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

AUC, area under the curve; CRL, crown-rump length; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; GA, gestational age; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; hPL, human placental lactogen; LMP, last menstrual period; PE(P-16:0e/0:0), 1-(1Z-hexadecenyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; PP, placental protein; RMSE, root mean squared error; SD, standard deviation; SP1, pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein; THDOC, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone.

Acyl-carnitine, amino acid, fatty acid, ceramide, ceramide 1-phosphate, galactosylceramide, phosphatidyl acid, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, cholesteryl ester, and sphingomyelin.

THDOC, Estriol-16-Glucoronide, Progesterone, PE (P-16:Oe/0:0) and DHEA-S.

C19H26O7S, C24H30O9 and estriol glucuronide.

Table 2.

Characteristics and main findings of included studies that assessed postnatal biomarkers for predicting gestational age.

| First author, year | Country (Region) | Design | Sample size | Biomarker(s) | Biological sample | Newborn age at testing | Reference standard | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moynihan, 197741 | Ireland (Dublin) | Prospective cohort | 45 | Isoenzymes A, B and C of erythrocytic carbonic anhydrase | Cord blood | At birth | GA estimated by LMP |

|

| Wilson, 201642 | Canada (Ontario, April 2007–March 2009) | Retrospective cohort | 249,700 (124,854 in model development dataset; 62,412 in validation dataset; and 62,434 in test dataset) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeninga | Heel prick blood | 24–72 h | GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound |

|

| Ryckman, 201643 | USA (Iowa) | Retrospective cohort | 230,013 (153,342 in model-building dataset; 76,671 in model-testing dataset) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningb | Heel prick blood | 0–24 h (14%); 25–72 h (84%); >72 h (2%) | GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound |

|

| Jelliffe-Pawlowski, 201644 | USA (California) | Retrospective cohort | 729,503 (547,127 in training dataset; 182,376 in testing dataset) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningc | Heel prick blood | 12 h to 8 days (91% between 12 and 72 h) | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Knight, 201645 | Multicountry | Retrospective cohort | 1342 (207 in training dataset, and 1135 in testing dataset) | DNA methylation profile | Cord blood (872 neonates) and heel prick blood (470 neonates) | From birth up to 39 days | GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound |

|

| Bohlin, 201646 | Norway | Retrospective cohort | 1753 (1068 in training dataset, and 685 in replication dataset) | DNA methylation profile | Cord blood | At birth | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Hawken, 201747 | Canada (Ontario, April 2009–September 2011) | Retrospective cohort | 300,132 (validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeninga | Heel prick blood | 24 h to 7 days | GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound |

|

| Wilson, 201748 | Canada (Ontario, January 2012–December 2014) |

Retrospective cohort | 159,215 (79,620 in model development dataset; 39,785 in validation dataset; and 39,810 in test dataset) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningd | Heel prick blood | <48 h | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Murphy, 201949 | Bangladesh | Prospective cohort | 1069 (external validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood samplese | Cord blood (1036 samples) and heel prick blood (487 samples) | 0 min to 2 h (cord blood); 25 min to 40 h (heel prick blood) | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Michaeli, 201950 | Israel (Jerusalem) | Prospective cohort | 41 (10 in training group and 31 in test group) | DNA methylation profile | Cord blood and placental samples | At birth | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Hawken, 202051 | Zambia (Lusaka) and Bangladesh (Matlab) | Prospective cohort | 1487 (external validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood samplesf | Heel prick blood (662 infants) and cord blood (1404 infants) | At birth (cord blood); 24–72 h (heel prick blood) | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Hawken, 202152 | China (Shanghai) | Retrospective cohort | 4448 (external validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningg | Heel prick blood | <72 h | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Oltman, 202153 | Uganda (Busia) | Prospective cohort | 666 (external validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood samplesh | Heel prick blood (666 infants) and cord blood (640 infants) | At birth (cord blood); ≤3 h (heel prick blood) | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Haftorn, 202154 | Norway and Finland | Retrospective cohort | 1941 (1429 in training dataset, and 512 in replication dataset) | DNA methylation profile | Cord blood | At birth | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

| Sazawal, 202155 | Tanzania, Pakistan and Bangladesh | Retrospective cohort | 1311 | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningi | Heel prick blood | 24–72 h | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Jasper, 202256 | Uganda | Retrospective cohort | 150 (external validation cohort) | Metabolomic profile derived from cord blood samplesj | Cord blood | At birth | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Hawken, 202257 | Canada (Ontario, January 2015–December 2017) |

Retrospective cohort | 52,659 (50,735 spontaneously conceived and 1924 conceived from ART) | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screeningk | Heel prick blood | <48 h | GA estimated by ultrasound and date of embryo transfer |

|

| Hawken, 202258 | Kenia | Prospective cohort | 1039 | Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood samplesl | Heel prick blood (1039 infants) and cord blood (1012 infants) | Within 30 min of delivery of the placenta (cord blood); 24–72 h (heel prick blood) | GA estimated by ultrasound |

|

| Haftorn, 202359 | Norway | Retrospective cohort | 2138 (1709 in training dataset, and 429 in replication dataset) | DNA methylation profile | Cord blood | At birth | GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound |

|

ART, assisted reproductive techniques; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; GA, gestational age; LBW, low birth weight; LMP, last menstrual period; RMSE, root mean square error; SD, standard deviation; SGA, small for gestational age.

Acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C16, C18, C18:1, C18:2), amino acids (arginine, phenylalanine, alanine, leucine, ornithine, citrulline, tyrosine, glycine, argininosuccinate, methionine, valine, biotinidine), fatty acid oxidation (C3DC, C4DC, C5OH, C5DC, C6DC), enzymes (galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase, biotinidase), and hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone).

Acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C3-DC, C4, C4-DC, C5, C5:1, C5-DC, C5-OH, C6, C6-DC, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C14-OH, C16, C16:1, C16:1-OH, C16-OH, C18, C18:1, C18:1-OH, C18:2, C18:OH), amino acids (alanine, arginine, citrulline, glutamate, isoleucine + leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, valine), enzymes (galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase, biotinidase), and hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone).

Free carnitine, acyl-carnitines (C-2, C-3, C-3DC, C-4, C-5, C-5:1, C-5DC, C-6, C-8, C-8:1, C-10, C-10:1, C-12, C-12:1, C-14, C-14:1, C-16, C-16:1, C-18, C-18:1, C-18:2, C-18:1OH), amino acids (alanine, arginine, citrulline, glycine, methionine, ornithine, phenylalanine, proline, 5-oxoproline, tyrosine, valine), thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and galactose-1-phosphate-uridyl-transferase.

Acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C5:1, C6, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C16, C18, C18:1, C18:2, C10:1, C12:1, C14:1, C14:2, C4OH, C5:1, C5DC, C5OH, C6DC, C16:OH, C16:1OH, C18OH, C18:1OH, C3DC, C4DC), amino acids (alanine; arginine; citrulline; phenylalanine; leucine; ornithine; tyrosine; glycine; argininosuccinate; methionine; valine; succinylacetone), hemoglobins (adult haemoglobin: HbA(A) and variants (S, C, D, E) fetal haemoglobin: HbF (F), acetylated HbF (F1), combined HbF (F + F1)), endocrine markers (17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)), and enzyme markers (biotinidase; galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT); immunotripsinogen).

Acylcarnitines (N = 31), amino acids (N = 12), haemoglobin profiles, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, thyroid stimulating hormone; immunoreactive trypsinogen, t-cell receptor excision circles, biotinidase activity, galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase activity.

Acyl-carnitines (C0; C2; C3; C4; C5; C5:1; C6; C8; C8:1; C10; C10:1; C12; C12:1; C14; C14:1; C14:2; C16; C18; C18:1; C18:2; C10:1; C12:1; C14:1; C14:2; C4OH; C5:1; C5DC; C5OH; C6DC; C16:OH; C16:1OH; C18OH; C18:1OH; C3DC; C4DC), amino acids (Arginine, phenylalanine, alanine, leucine, ornithine, citrulline, tyrosine, glycine, methionine, valine), hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone), haemoglobins (adult haemoglobin, fetal haemoglobin, and acetylated HbF), and enzyme markers (biotinidase and immunotripsinogen).

Acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C8, C10, C12, C14, C16, C18, C10:1, C12:1, C14OH, C14:1, C14:2, C16OH, C18OH, C18:1, C18:2, C3DC, C4DC, C4OH, C5DC, C5OH, C5:1, C6DC, C8:1), TSH, 17OHP, alanine, arginine, citruline, glycine, leucine, methionine, ornithine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and valine.

Acyl-carnitines (free carnitine, C2, C3, C4, C4-DC, C4-OH, C5, C5-OH, C6, C8, C10, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C16, C16:1, C16:1-OH, C18, C18:1, C18:2), amino acids (alanine, arginine, citrulline, glutamate, leucine, methionine, ornithine, phenylalanine, succinylacetone, tyrosine, valine), and hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone).

Alanine, arginine, isoleucine + leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, valine, C2, C3, C3-DC, C4, C4-DC, C5, C5:1, C5-OH, C5-DC, C6, C6-DC, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14-OH, C16, C16:1, C16-OH, C16:1-OH, C18, C18:1, C18:1OH, C18:2, GALT, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Arginosuccinate, isoleucine + leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, valine, C3, C4, C4-DC, C4-OH, C5, C8:1, C14, C14:1, C16, C18-OH, and C18:1.

Haemoglobins (adult haemoglobin, fetal haemoglobin, and acetylated HbF), endocrine markers (17-hydroxyprogesterone, thyroid stimulating hormone), amino acids (arginine, phenylalanine, alanine, leucine, ornithine, citrulline, tyrosine, glycine, methionine, valine), acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C5:1, C6, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C16, C18, C18:1, C18:2, C10:1, C12:1, C14:1, C14:2, C4OH, C5:1, C5DC, C5OH, C6DC, C16:OH, C16:1OH, C18OH, C18:1OH, C3DC, C4DC), enzyme markers (biotinidase, immunoreactive trypsinogen), and immune markers (T-cell receptor excision circles).

Haemoglobins (adult haemoglobin, fetal haemoglobin, and acetylated HbF), endocrine markers (17-hydroxyprogesterone, thyroid stimulating hormone), amino acids (arginine, phenylalanine, alanine, leucine, ornithine, citrulline, tyrosine, glycine, methionine, valine), acyl-carnitines (C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C5:1, C6, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C16, C18, C18:1, C18:2, C10:1, C12:1, C14:1, C14:2, C4OH, C5:1, C5DC, C5OH, C6DC, C16:OH, C16:1OH, C18OH, C18:1OH, C3DC, C4DC), enzyme markers (biotinidase, immunoreactive trypsinogen, galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase), and immune markers (T-cell receptor excision circles).

Biomarkers were obtained from the following biological samples: maternal serum21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35,37 (six biomarkers), maternal plasma36,38 (two biomarkers), maternal whole blood39 (one biomarker), maternal urine29,34 (two biomarkers), cord blood41,45,46,49, 50, 51,53,54,56,58,59 (three biomarkers), newborn blood spot42, 43, 44, 45,47, 48, 49,51, 52, 53,55,57,58 (2 biomarkers) and placental sample50 (one biomarker). Further breakdown of this is available in box 1. Biomarkers were evaluated throughout the three trimesters as well as in the immediate postnatal period: first trimester (18 studies), second trimester (nine studies), third trimester (five studies) and postnatally (21 studies). Samples were collected once only (22 studies), serially (12 studies) and frequency was not clearly defined in five studies.

Box 1. Potential biomarkers identified and type of biological sample analysed.

Prenatal biomarkers

-

1.

Maternal serum

cfRNA

hCG

hPL

Sp1

Placental protein 14

Metabolomic profile (Acyl-carnitine, amino acid, fatty acid, ceramide, ceramide 1-phosphate, galactosylceramide, phosphatidyl acid, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, cholesteryl ester, and sphingomyelin)

-

2.

Maternal plasma

Proteomic profile

Metabolomic profile (THDOC, Estriol-16-Glucoronide, Progesterone, PE (P-16:Oe/0:0) and DHEA-S)

-

3.

Maternal whole blood

Exon-level gene expression

-

4.

Maternal urine

Sp1

Metabolomic profile (C19H26O7S, C24H30O9 and estriol glucuronide)

Postnatal biomarkers

-

1.

Cord blood

DNA methylation profile

Isoenzymes of erythrocytic carbonic anhydrase (A, B and C)

Metabolomic profile (Acyl-carnitines, amino acids, enzymes, enzyme markers, fatty acid oxidation, free carnitine, haemoglobins (adult haemoglobin: HbA(A) and variants (S, C, D, E) fetal haemoglobin: HbF (F), acetylated HbF (F1), combined HbF (F + F1)), hormones (Thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, galactose-1-phosphate-uridyl-transferase), immunoreactive trypsinogen, t-cell receptor excision circles)

-

2.

Placental sample

DNA methylation profile

-

3.

Newborn blood spot

DNA methylation

Metabolomic profile (Acyl-carnitines, amino acids, enzyme markers, haemoglobin profiles, hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone), immunoreactive trypsinogen, t-cell receptor excision circles)

DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; hPL, human placental lactogen; LMP, PE(P-16:0e/0:0), 1-(1Z-hexadecenyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; PP, placental protein; SP1, pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein; THDOC, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone.

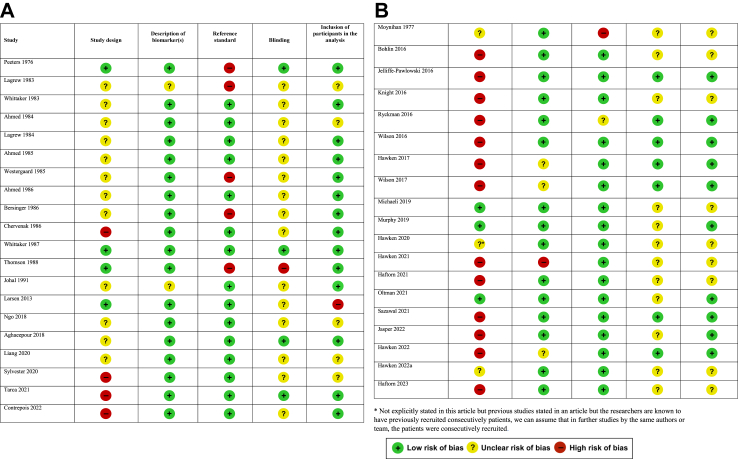

The risk of bias in each included study is summarised in Fig. 2A (prenatal) and 2B (postnatal). Only one study31 was judged to be at low risk of bias for all five criteria (3%). Eight studies (21%) were deemed to be at low risk of bias for 4 domains and 14 were judged to be at low risk of bias for 3 domains (36%). The remaining 16 studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for ≤2 domains (41%). The most common shortcomings were related to the study design and blinding of researchers to the results of the “gold standard” GA. The majority of studies included in our review were prospective (56%), with 41% performed retrospectively and unclear in one study.22 Blinding of the gold standard was performed in 11 studies (28%), documented not to have occurred in one (3%) and unclear in the remaining 27 studies (69%). In 26 studies (67%) the reference GA was the gold standard (Ultrasound or LMP corroborated by ultrasound), 12 studies (33%) used LMP or ovulation date without ultrasound corroboration and one study (3%) used a combination of ovulation date with LMP and ultrasound.

Fig. 2.

A Risk of bias assessment in studies assessing prenatal biomarkers. B Risk of bias assessment in studies assessing postnatal biomarkers.

Accuracy of prenatal biomarkers to estimate gestational age

Overall, the correlation of the GA predicted by hCG in serum and the GA estimated by LMP was higher when testing was performed before 9 weeks than at or after 9 weeks (Table 1). Meta-analyses showed that the pooled coefficients of correlation were 0.88 (95% CI, 0.83–0.92, I2 = 56%; 6 studies) at 4–9 weeks and 0.43 (95% CI, 0.30–0.54, I2 = 0%; 3 studies) at 4–16 weeks (Table 3). For SP1, the pooled coefficients of correlation were 0.84 (95% CI, 0.80–0.88, I2 = 78%; 4 studies) at 5–10 weeks and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.66–0.75, I2 = 98%; 4 studies) at 5–16 weeks. For hPL, the pooled coefficient of correlation was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.69–0.84, I2 = 80%; 3 studies) at 6–16 weeks. The average difference between the GA predicted by hCG before 9 weeks and the GA estimated by LMP ranged between 0.4 and 2.2 weeks (median, 0.6 weeks; 5 studies).

Table 3.

Meta-analyses of the predictive accuracy of prenatal and postnatal biomarkers for gestational age.

| Biomarker | Biological sample | Population | Average deviation |

Correlation coefficient |

Predicted gestational age |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled RMSE (95% CI), weeks | No. of women or infants (No. of studies) | Pooled r (95% CI) | I2, % | No. of women or infants (No. of studies) | Within ±1 week of GA estimated by gold standard method |

Within ±2 weeks of GA estimated by gold standard method |

|||||||

| Pooled % (95% CI) | I2, % | No. of infants (No. of studies) | Pooled % (95% CI) | I2, % | No. of infants (No. of studies) | ||||||||

| Prenatal biomarkers | |||||||||||||

| hCG between 4 and 9 weeks | Serum | Women | – | – | 0.88 (0.83–0.92) | 56 | 261 (622, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hCG between 4 and 16 weeks | Serum | Women | – | – | 0.43 (0.30–0.54) | 0 | 185 (322,25,27) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SP1 between 5 and 10 weeks | Serum | Women | – | – | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | 78 | 255 (424,26,27,29) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SP1 between 5 and 16 weeks | Serum | Women | – | – | 0.71 (0.66–0.75) | 98 | 462 (424,27,29,32) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hPL between 6 and 16 weeks | Serum | Women | – | – | 0.78 (0.69–0.84) | 80 | 303 (323,31,32) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Metabolomic profile | Serum | Women | 2.90 (2.61–3.21) | 39 (237,38) | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0 | 39 (237,38) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Postnatal biomarkers | |||||||||||||

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | All infants | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 536,612 (942,43,47, 48, 49,51,55,57,58) | – | – | – | 68.8 (65.8–72.0) | 99.8 | 541,726 (1142,43,47, 48, 49,51, 52, 53,55,57,58) | 94.4 (94.0–94.8) | 91.6 | 488,028 (942,43,47, 48, 49,51, 52, 53,55) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | Infants ≥37 weeks | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 102,244 (242,48) | – | – | – | 69.2 (69.0–69.3) | 0 | 402,376 (342,47,48) | 96.1 (95.7–96.6) | 96 | 402,376 (342,47,48) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | Infants <37 weeks | 1.56 (1.48–1.63) | 107,627 (542,48,51,57,58) | – | – | – | 49.6 (39.0–63.1) | 99.8 | 594,583 (1042,44,47,48,51,52,57,58) | 80.1 (73.8–87.0) | 98.9 | 590,687 (642,44,47,48,51,52) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | Infants 32–36 weeks | – | – | – | – | – | 50.1 (28.9–86.6) | 100 | 544,942 (342,44,47) | 81.1 (69.7–94.4) | 99.9 | 544,942 (342,44,47) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | Infants <32 weeks | – | – | – | – | – | 49.7 (46.4–53.2) | 71.9 | 544,942 (342,44,48) | 76.6 (73.6–79.7) | 75.4 | 544,942 (342,44,48) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening | Heel prick blood | SGA infants | 1.43 (1.37–1.50) | 185,018 (842,43,47,49,51,55,57,58) | – | – | – | 52.2 (45.8–59.4) | 96.0 | 51,027 (748,49,51, 52, 53,55,57,58) | 86.9 (81.5–92.6) | 94.8 | 48,791 (548,49,51, 52, 53,55) |

| Metabolomic profile derived from cord blood samples | Cord blood | All infants | 1.57 (1.03–2.39) | 2198 (349,56,58) | – | – | – | 60.6 (59.2–62.1) | 0 | 7345 (549,52,53,56,58) | 89.2 (87.0–91.6) | 74.5 | 6333 (449,52,53,56) |

| DNA methylation profile | Cord blood | All infants | 1.60 (1.51–1.70) | 183,042 (244,53) | 0.85 (0.78–0.89) | 96.6 | 4501 (545,46,50,54,59) | – | – | – | – | – | |

CI, confidence interval; GA, gestational age; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; hPL, human placental lactogen; LMP, last menstrual period; r, correlation coefficient; RMSE, root mean square error; SP1, pregnancy-specific beta-1-glycoprotein.

The pooled coefficient of correlation for the GA predicted by metabolomic profiling in serum throughout the prenatal period and the GA estimated by ultrasound was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.81–0.95, I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 96 women). The pooled RMSE was 2.9 weeks (95% CI, 2.61–3.21). The AUC of models including several metabolites to discriminate between preterm birth and term birth was ∼ 0.90. One study37 reported that a model including 13 categories of metabolites predicted GA within 1 week of GA estimated by ultrasound for 67% of women and within 2 weeks for 78% of women. Two small studies reported that models of cell-free RNA transcripts35 and proteins36 in serum predicted GA with correlation coefficients of ∼0.90 and ∼0.95, respectively. Another study, involving 133 women, reported that whole-blood gene expression predicted GA with a correlation coefficient of 0.83 and a RMSE of 4.5 weeks.39

Accuracy of postnatal biomarkers to estimate gestational age: metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening

Thirteen studies reported on the use of newborn blood spot to estimate GA. Overall, the average difference between GA predicted by the newborn metabolomic models and the GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound was slightly over 1 week (pooled RMSE of 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00–1.06; nine studies) (Table 3). This biomarker performed better among term infants (pooled RMSE of 1.00 week; 95% CI, 0.97–1.04; two studies) than among preterm infants (pooled RMSE of 1.56 weeks; 95% CI, 1.48–1.63; five studies) and SGA infants (pooled RMSE of 1.43 weeks; 95% CI, 1.37–1.50; eight studies).

Eleven studies provided data to calculate the ability of metabolomic profiling models to estimate GA within one and/or two week(s) of the gold standard using newborn blood spots. Overall, GA was correctly estimated by metabolomic profiling models to within one week of GA estimated by LMP and/or ultrasound for 68.8% of infants (95% CI, 65.8%–720%, I2 = 99.8%) and within 2 weeks for 94.4% of infants (95% CI, 94.0%–94.8%, I2 = 91.6%). Metabolomic profiling models performed best among term infants, correctly estimating GA to within one week in 69.2% of newborns (95% CI, 69.0%–69.3%, I2 = 0%; 3 studies) and within two weeks in 96.1% of newborns (95% CI, 95.7 to 96.6, I2 = 96%; 3 studies). The metabolomic profiling had a lower performance among infants born before 37 weeks (GA correctly estimated within one week in 49.6% and within two weeks in 80.1%), infants born between 32 and 36 weeks (GA correctly estimated within one week in 50.1% and within two weeks in 81.1%), infants born before 32 weeks (GA correctly estimated within one week in 49.7% and within 2 weeks in 76.6%), and SGA infants (GA correctly estimated within one week in 52.2% and within 2 weeks in 86.9%).

The pooled AUC of metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening to discriminate infants with a GA <37 weeks from those with a GA ≥37 weeks was 0.933 (95% CI, 0.905–0.962; I2 = 100%; 8 studies). The pooled AUC of metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening to discriminate infants with a GA <34 weeks from those with a GA ≥34 weeks was 0.986 (95% CI, 0.980–0.993; I2 = 91.2%; 3 studies).

Accuracy of postnatal biomarkers to estimate gestational Age:Metabolomic profile derived from newborn cord blood

Overall, performance of metabolomic profiling models from cord blood was lower than that of metabolomic profiling models from samples of newborn heel pricks with a pooled RMSE of 1.57 weeks (95% CI, 1.03–2.39; three studies) and infants GAs correctly predicted within one week in 60.6% (95% CI, 59.2 to 62.1, I2 = 0%; 5 studies) and within two weeks in 89.2% (95% CI, 87.0 to 91.6, I2 = 74.5%; 4 studies). The pooled AUC of metabolomic profile models from cord blood in differentiating infants born before 37 weeks from those born at or after 37 weeks was 0.910 (95% CI, 0.873–0.946; I2 = 28%; 3 studies).49,53,56

Accuracy of postnatal biomarkers to estimate gestational age: DNA methylation profile

The pooled average difference between GA predicted by cord blood DNA methylation profile and the GA estimated by LMP and ultrasound was 1.60 weeks (95% CI, 1.51–1.70; two studies) with a pooled coefficient of correlation of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.78 to 0.89, I2 = 96.6%; five studies).

Exploration of heterogeneity

There was a significant level of heterogeneity among studies in the majority of meta-analyses performed. Most planned subgroup analyses could not be performed given the small number of studies included in the meta-analyses. However, subgroup analyses for maternal hCG between 4 and 9 weeks of gestation and the metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening in all infants, those born before <37 weeks of gestation, and those born SGA showed that the study setting, sample size, and the study quality did not provide an explanation for heterogeneity.

Discussion

Metabolomic profiling from newborn heel prick blood spots during the immediate postnatal period provided the most accurate estimate of GA, with a pooled RMSE of 1.03 weeks across all GAs. It performed best for term infants, showing slightly reduced accuracy for preterm or SGA infants. In addition, the metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot screening appeared to differentiate between preterm (<37 weeks) and term (≥37 weeks) infants, as well as between infants born before 34 weeks and those at or after 34 weeks with a pooled AUC of 0.93 and 0.98, respectively.

Metabolomic profiling and DNA methylation profile from cord blood samples provided less accurate estimates of GA compared to metabolomic profiling from heel prick blood samples, with pooled RMSEs of 1.57 and 1.60 weeks, respectively.

Among the placental hormones assessed, hCG measured between 4 and 9 weeks of gestation showed the highest correlation with the reference standard GA, usually estimated by LMP, with a pooled coefficient of correlation of 0.88. However, the pooled RMSE could not be estimated due to lack of data.

Evidence from two small studies indicated that metabolomic profiling from maternal blood samples collected throughout pregnancy to estimate GA had low accuracy, with a pooled RMSE of 2.90 weeks.

Insufficient evidence was available to evaluate other prenatal biomarkers, such as cell-free RNA transcripts, proteomic profile, and exon-level gene expression.

Our systematic review has identified promising methods for postnatal GA estimation using algorithms that combine metabolomic profile derived from newborn heel-prick blood spots with clinical and demographic variables (mainly birthweight, sex, and multiple birth status). These algorithms estimated GA postnatally to within approximately 1 week of a reference standard. This approach outperformed neonatal assessments like the Dubowitz and Ballard scores, which deviate by ±2.6 to 3.8 weeks from the gold standard GA.12 Therefore, metabolomics modelling based on heel-prick blood spot samples are highly likely to be a more accurate way to estimate GA when early pregnancy ultrasound is not available. Importantly, the metabolomic profile derived from newborn blood spot showed consistent performance across a variety of settings and ethnicities, including in high-income countries and LMICs. However, the requirement of tandem mass spectrometers or other necessary devices required for metabolomic profiling from heel prick blood spots poses a major limitation for implementation, particularly in resource-poor settings, and the cost of testing, estimated at approximately USD $50 per child, is also a significant obstacle.60

The second major limitation is that postnatal GA estimation using metabolomic profiling from cord blood samples or heel prick blood spots is not available to guide clinical prenatal care at the level of the individual woman. Therefore postnatal markers are not useful for prenatal care. Nevertheless, postnatal markers could be a fruitful avenue to guide research if they can be assessed in maternal blood or urine prenatally.

The challenges and importance of improving pathology and laboratory provision in LMICs was discussed in the Lancet series.61, 62, 63 The authors identified four key barriers to achieving optimal laboratory services in LMICs including lack of: trained personnel, education and training, infrastructure and agreed quality standards and accreditation.63 Costs are lower if the turn-around time is longer and if the laboratory is performing higher numbers of tests61 which could be overcome by centralising resources, however, this would prevent the results being available for individualised care of the pregnant woman or neonate.

There were differences in accuracy of postnatal GA estimation between metabolomic profiles derived from cord blood samples and heel-prick blood spots. In theory, most proteins or transcripts can be assessed in numerous different samples, and such differences may simply be due to variations in techniques rather than whether they are coming from cord or heel-prick. However, differences could also be attributable to various other factors, including timing of collection, fluctuations in neonatal analyte levels during the early postpartum period, and infant feeding status prior to collection.49 Samples taken directly from the newborn may better reflect their physiology compared to cord specimens. Although metabolomic profiling derived from cord blood samples for estimating GA was less accurate than from heel prick blood samples, it still outperformed Dubowitz and Ballard scores. Collecting cord blood samples does not cause discomfort to the newborn, may be more acceptable to parents and avoids extensive training required for heel prick sample collection techniques.

The main strengths of our study include the following: (1) the rigorous methodology used for performing the systematic review; (2) the use of a prospective protocol designed to answer a specific research question; (3) the extensive and continually updated literature searches without language restrictions; (4) the strict assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies; (5) the quantitative way of summarizing the evidence; and (6) the inclusion of >1.7 million newborns in the studies that examined the accuracy of postnatal biomarkers. Some potential limitations must also be considered. First, there was an important degree of heterogeneity in most of the meta-analyses performed. We explored the sources of heterogeneity and were unable to identify plausible explanations; therefore, pooled estimates should be interpreted cautiously. We used a random-effects model to pool results from individual studies, which provides the most useful and conservative estimate for informing practice in the presence of unexplained heterogeneity. Nevertheless, the between-study heterogeneity, inability to assess publication bias and small number of studies remain an important limitation of the study. Second, study quality was a limitation of the studies included in the review with only one-fourth of included studies being judged to be at low risk of bias for at least four domains. Third, most studies that assessed placental hormones did not use an appropriate reference standard for pregnancy dating because ultrasound was not widely available when such studies were conducted. Moreover, there was heterogeneity of reference ultrasound timing in some studies assessing postnatal biomarkers, mainly those conducted in LMICs, in which only a small proportion of women had reference ultrasound completed between 9 and 13 weeks of gestation. Fourth, authors of included studies chose a wide variety of statistics to report accuracy of biomarkers to estimate GA, which made combining results difficult. Fifth, the use of the logit transformation approach and ignorance of population weights in the calculation of pooled proportions has the potential to produce misleading pooled estimates. Sixth, we used the DerSimonian and Laird approach for random-effects meta-analyses, and it is possible that the 95% CIs of our meta-analyses could be slightly different if other statistical methods proposed for adjusting them are used (such as the Hartung, Knapp, Sidik and Jonkman or modified Knapp−Hartung methods for random effects meta-analysis). However, the approach we use is recommended in Cochrane reviews and these methods differ only in respect to the calculation of the confidence intervals, not pooled estimates. Finally, the number of studies that assessed several biomarkers, mainly prenatal ones, is still too small for us to draw firm conclusions.

In conclusion, our study has identified several candidate biomarkers that could estimate GA in settings where early ultrasound is unavailable. Further studies are required to compare the most promising of these biomarkers to each other, as well as to other modalities such as ultrasound, fundal height or other clinical markers of GA assessment, in order to identify which will prove most useful. Several factors would need to be considered including accuracy, cost, equipment and infrastructure required. This is particularly important in LMIC settings in which pregnancy dating is especially challenging. Cultural acceptability of such a test would also be an important consideration, as we know parents may prefer a cord blood sample to be obtained over a heel prick blood sample.51 Therefore, cord blood tests may have a place despite their lower accuracy in estimating GA. Finally, simplification of metabolomic profiling models to reduce the number of analytes while maintaining a good accuracy to estimate GA will be required to streamline the approach for scalable, cost-effective applications. Thus, although -omics technology is too expensive and impractical for widespread use, the techniques can be used to identify proteins of interest. In turn, inexpensive, point of care assays could then be developed for these proteins. Future studies should report on cost, as these methods are likely to have most benefit in LMIC settings where cost is an important barrier to implementation.

Contributors

ATP: Funding acquisition, project administration; EB, ATP: Conceptualisation; EB, ACA, NR, JV, ATP: Design of methodology; NR, EB, ACA: Literature search; ACA, EB: Data analysis; ACA, EB, JV, ATP: Data interpretation; EB, ACA, ATP: Writing–original draft; All authors: Writing—review & editing,: all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. ATP, EB and ACA have directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data in this publication are drawn exclusively from publicly available sources and datasets. All relevant information, including aggregated data and key study characteristics, can be accessed in the original publications cited in this review.

Declaration of interests

A.T.P. is a Senior Advisor of Intelligent Ultrasound. ATP is supported by the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre with funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) funding scheme. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR the Department of Health or any of the other funders. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102498.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Lawn J.E., Ohuma E.O., Bradley E., et al. Small babies, big risks: global estimates of prevalence and mortality for vulnerable newborns to accelerate change and improve counting. Lancet. 2023;401(10389):1707–1719. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savitz D.A., Terry J.W., Jr., Dole N., Thorp J.M., Jr., Siega-Riz A.M., Herring A.H. Comparison of pregnancy dating by last menstrual period, ultrasound scanning, and their combination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1660–1666. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napolitano R., Dhami J., Ohuma E.O., et al. Pregnancy dating by fetal crown-rump length: a systematic review of charts. BJOG. 2014;121(5):556–565. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papageorghiou A.T., Kemp B., Stones W., et al. Ultrasound-based gestational-age estimation in late pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(6):719–726. doi: 10.1002/uog.15894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brighton A., D'Arcy R., Kirtley S., Kennedy S. Perceptions of prenatal and obstetric care in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120(3):224–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Self A., Daher L., Schlussel M., Roberts N., Ioannou C., Papageorghiou A.T. Second and third trimester estimation of gestational age using ultrasound or maternal symphysis-fundal height measurements: a systematic review. BJOG. 2022;129(9):1447–1458. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee L.H., Bradburn E., Craik R., et al. Machine learning for accurate estimation of fetal gestational age based on ultrasound images. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):36. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00774-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung R., Villar J., Dashti A., et al. Achieving accurate estimates of fetal gestational age and personalised predictions of fetal growth based on data from an international prospective cohort study: a population-based machine learning study. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(7):e368–e375. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30131-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts D., Brown J., Medley N., Dalziel S.R. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conde-Agudelo A., Romero R. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in preterm infants less than 34 weeks' gestation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perin J., Mulick A., Yeung D., et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(2):106–115. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00311-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A.C., Panchal P., Folger L., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of neonatal assessment for gestational age determination: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;140 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McInnes M.D.F., Moher D., Thombs B.D., et al. Preferred reporting Items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W., Westwood M.E., et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedges L.V.O.I. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1995. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter J.E.S.F. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. Methods of metaanalysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou X.H.N.O., McClish D.K. Wiley; NewYork: 2002. Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeks J.J., Macaskill P., Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(9):882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D.L.A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peeters L.L., Lemons J.A., Niswender G.D., Battaglia F.C. Serum levels of human placental lactogen and human chorionic gonadotropin in early pregnancy: a maturational index of the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126(6):707–711. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagrew D.C., Wilson E.A., Jawad M.J. Determination of gestational age by serum concentrations of human chorionic gonadotropin. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(1):37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittaker P.G., Aspillaga M.O., Lind T. Accurate assessment of early gestational age in normal and diabetic women by serum human placental lactogen concentration. Lancet. 1983;2(8345):304–306. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed A.G., Klopper A., Dati F. Determination of the stage of gestation by the assay of chorionic gonadotrophin and Schwangerschaftsprotein 1. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91(12):1234–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagrew D.C., Wilson E.A., Fried A.M. Accuracy of serum human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations and ultrasonic fetal measurements in determining gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149(2):165–168. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westergaard J.G., Teisner B., Grudzinskas J.G., Chard T. Single measurements of chorionic gonadotropin and schwangerschafts protein for assessing gestational age and predicting the day of delivery. J Reprod Med. 1985;30(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed A.G., Klopper A.I. Observations on the dating of pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985;20(6):347–355. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(85)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed A.G., Klopper A. Estimation of gestational age by last menstrual period, by ultrasound scan and by SP1 concentration: comparisons with date of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(2):122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bersinger N., Luke G., Klopper A. Comparison of the concentration of schwangerschaftsprotein 1 (SP1) in the serum and urine of pregnant women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1986;21(3):113–116. doi: 10.1159/000298939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chervenak F.A., Brightman R.C., Thornton J., Berkowitz G.S., David S. Crown-rump length and serum human chorionic gonadotropin as predictors of gestational age. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(2):210–213. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittaker P.G., Lind T., Lawson J.Y. A prospective study to compare serum human placental lactogen and menstrual dates for determining gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156(1):178–182. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson M.A., Duncan R.O., Cunningham P. The value of serum human placental lactogen and Schwangerschaftsprotein 1 to determine gestation in an ante-natal population. Hum Reprod. 1988;3(4):463–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johal B., Setchell M.E., Chard T. A comparison of biochemical and biophysical determination of gestational age in early pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;11(5):340–341. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsen J., Buchanan P., Johnson S., Godbert S., Zinaman M. Human chorionic gonadotropin as a measure of pregnancy duration. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(3):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngo T.T.M., Moufarrej M.N., Rasmussen M.H., et al. Noninvasive blood tests for fetal development predict gestational age and preterm delivery. Science. 2018;360(6393):1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghaeepour N., Lehallier B., Baca Q., et al. A proteomic clock of human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(3):347.e1–347.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sylvester K.G., Hao S., You J., et al. Maternal metabolic profiling to assess fetal gestational age and predict preterm delivery: a two-centre retrospective cohort study in the US. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang L., Rasmussen M.H., Piening B., et al. Metabolic dynamics and prediction of gestational age and time to delivery in pregnant women. Cell. 2020;181(7):1680–1692.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarca A.L., Pataki B.A., Romero R., et al. Crowdsourcing assessment of maternal blood multi-omics for predicting gestational age and preterm birth. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(6) doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Contrepois K., Chen S., Ghaemi M.S., et al. Prediction of gestational age using urinary metabolites in term and preterm pregnancies. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8033. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11866-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moynihan J.B. Relationship between maturity and isoenzymes of erythrocytic carbonic anhydrase in newborn infants. Pediatr Res. 1977;11(8):871–873. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson K., Hawken S., Potter B.K., et al. Accurate prediction of gestational age using newborn screening analyte data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):51.e1–51.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryckman K.K., Berberich S.L., Dagle J.M. Predicting gestational age using neonatal metabolic markers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):515.e1–515.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jelliffe-Pawlowski L.L., Norton M.E., Baer R.J., Santos N., Rutherford G.W. Gestational dating by metabolic profile at birth: a California cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):511.e1–511.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knight A.K., Craig J.M., Theda C., et al. An epigenetic clock for gestational age at birth based on blood methylation data. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1068-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohlin J., Haberg S.E., Magnus P., et al. Prediction of gestational age based on genome-wide differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1063-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawken S., Ducharme R., Murphy M.S.Q., et al. Performance of a postnatal metabolic gestational age algorithm: a retrospective validation study among ethnic subgroups in Canada. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson K., Hawken S., Murphy M.S.Q., et al. Postnatal prediction of gestational age using newborn fetal hemoglobin levels. EBioMedicine. 2017;15:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy M.S., Hawken S., Cheng W., et al. External validation of postnatal gestational age estimation using newborn metabolic profiles in Matlab, Bangladesh. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.42627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falick Michaeli T., Spiro A., Sabag O., et al. Determining gestational age using genome methylation profile: a novel approach for fetal medicine. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39(11):1005–1010. doi: 10.1002/pd.5535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawken Sea Development and external validation of machine learning algorithms for postnatal gestational age estimation using clinical data and metabolomic markers. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.21.20158196v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hawken S., Murphy M.S.Q., Ducharme R., et al. External validation of machine learning models including newborn metabolomic markers for postnatal gestational age estimation in East and South-East Asian infants. Gates Open Res. 2020;4:164. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.13131.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oltman S.P., Jasper E.A., Kajubi R., et al. Gestational age dating using newborn metabolic screening: a validation study in Busia, Uganda. J Glob Health. 2021;11 doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haftorn K.L., Lee Y., Denault W.R.P., et al. An EPIC predictor of gestational age and its application to newborns conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Clin Epigenet. 2021;13(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sazawal S., Ryckman K.K., Mittal H., et al. Using AMANHI-ACT cohorts for external validation of Iowa new-born metabolic profiles based models for postnatal gestational age estimation. J Glob Health. 2021;11 doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jasper E.A., Oltman S.P., Rogers E.E., et al. Targeted newborn metabolomics: prediction of gestational age from cord blood. J Perinatol. 2022;42(2):181–186. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01253-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hawken S., Olibris B., Ducharme R., et al. Validation of gestational age determination from ultrasound or a metabolic gestational age algorithm using exact date of conception in a cohort of newborns conceived using assisted reproduction technologies. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;2(4) doi: 10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hawken S., Ward V., Bota A.B., et al. Real world external validation of metabolic gestational age assessment in Kenya. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]