Abstract

Background

Fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) is frequently associated with abnormal oxygenation; however, little is known about the accuracy of oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2) compared with arterial blood gas (ABG) saturation (SaO2), the factors that influence the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and the impact of PaCO2 on outcomes in patients with fibrotic ILD.

Study design and methods

Patients with fibrotic ILD enrolled in a large prospective registry with a room air ABG were included. Prespecified analyses included testing the correlation between SaO2 and SpO2, the difference between SaO2 and SpO2, the association of baseline characteristics with both the difference between SaO2 and SpO2 and the PaCO2, the association of baseline characteristics with acid-base category, and the association of PaCO2 and acid-base category with time to death or transplant.

Results

A total of 532 patients with fibrotic ILD were included. Mean resting SaO2 was 92±4% and SpO2 was 95±3%. Mean PaCO2 was 38±6 mmHg, with 135 patients having PaCO2 <35 mmHg and 62 having PaCO2 >45 mmHg. Correlation between SaO2 and SpO2 was mild to moderate (r=0.39), with SpO2 on average 3.0% higher than SaO2. No baseline characteristics were associated with the difference in SaO2 and SpO2. Variables associated with either elevated or abnormal (elevated or low) PaCO2 included higher smoking pack-years and lower baseline forced vital capacity (FVC). Lower baseline lung function was associated with an increased risk of chronic respiratory acidosis. PaCO2 and acid-base status were not associated with time to death or transplant.

Interpretation

SaO2 and SpO2 are weakly-to-moderately correlated in fibrotic ILD, with limited ability to accurately predict this difference. Abnormal PaCO2 was associated with baseline FVC but was not associated with outcomes.

Keywords: interstitial fibrosis

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Pulse oximetry (SpO2) is commonly used as a surrogate for arterial blood oxygen saturation; however, the reliability of SpO2 as a surrogate of SaO2 in patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) remains unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the characteristics of pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas (ABG) in patients with fibrotic ILD.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our findings raise important questions regarding the clinical utility of ABG and pulse oximetry in patients with ILD.

These results may affect the way each measurement is used clinically and highlight the need for additional studies comparing and optimising these tests.

Introduction

Fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) is frequently associated with clinically significant hypoxaemia and need for supplemental oxygen.1 Arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) is typically estimated using pulse oximetry (SpO2), which can be performed at rest, with ambulation and nocturnally. A minority of patients with fibrotic ILD also have abnormalities in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) as measured by arterial blood gas (ABG), which can occur secondary to advanced ILD or other causes (eg, respiratory muscle weakness, concomitant airways disease).

SpO2 is an inexpensive and non-invasive method of estimating SaO2; however, several factors affect the accuracy of SpO2, including darker skin pigmentation, anaemia, acidosis, critical illness and systemic sclerosis.2 3 The accuracy of SpO2 as a surrogate of SaO2 has been assessed in multiple populations, including patients with critical illness, both stable and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. However, there are limited data on the accuracy of SpO2 in fibrotic ILD and on the potential to predict this difference using baseline characteristics.4–7 There are similarly limited data on factors that influence PaCO2 and the impact of PaCO2 on disease outcome.

An improved understanding of the interpretation and prognostic significance of ABG findings would enhance clinical decision-making. We therefore sought to compare SpO2 and SaO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD, identify clinical variables associated with discordance between these measurements and identify variables and outcomes associated with abnormal PaCO2. We hypothesised that SaO2 and SpO2 would be within 2% for 95% of patients with fibrotic ILD at rest when SpO2 was ≥80% as previously seen in the general population,2 and that patients with fibrotic ILD with resting hypoxaemia would have higher levels of discordance between SaO2 and SpO2. Lastly, we hypothesised that clinical variables associated with abnormally high PaCO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD would include high body mass index (BMI), active smoking status and lower forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).

Methods

Study design, population and data collection

A retrospective chart review was completed on patients with fibrotic ILD enrolled in the prospective multicentre Canadian Registry for Pulmonary Fibrosis (CARE-PF).8 9 Eligible patients for this substudy were adults with any fibrotic ILD subtype who had an outpatient ABG performed while breathing room air. There were no exclusion criteria.

ABG measurements

The most recent room air ABG collected on any date after diagnosis or within 90 days prior to identification of fibrotic ILD by chest CT was recorded to provide the greatest spectrum of data that would maximise generalisability (ie, some patients provided an ABG early in their disease course, and some patients later in their disease course). Extracted data included pH, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), bicarbonate (HCO3-) and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2). PaCO2 was assessed as both a continuous and a categorical variable that grouped patients as abnormal (<35 or >45 mmHg) or normal (35–45 mmHg).10 Each ABG was assessed for acid-base abnormalities and further categorised into their primary abnormality (referred to as ‘acid-base category’), including acute respiratory acidosis or alkalosis, chronic respiratory acidosis or alkalosis, or metabolic acidosis or alkalosis. Given the absence of clear standards on ABG interpretation, we created the following definitions for each acid-base abnormality:

Acute respiratory acidosis was defined as pH <7.35 and PaCO2 >45 mmHg.

Acute respiratory alkalosis was defined as pH >7.45 and PaCO2<35 mmHg.

Metabolic acidosis was defined as pH <7.35 and HCO3- <22 mEq/L.

Metabolic alkalosis was defined as pH >7.45 and HCO3- >26 mEq/L.

Chronic respiratory acidosis was defined as pH <7.4, PaCO2 >45 mmHg, HCO3- > 24 mEq/L with PaCO2 and HCO3- increased above their respective baselines (PaCO2= 40 mmHg, HCO3- = 24 mEq/L) in a ratio of 10:2 or greater.

Chronic respiratory alkalosis was defined as pH >7.4, PaCO2<35 mmHg, HCO3- <24 mEq/L with PaCO2 and HCO3- decreased below their respective normal values (PaCO2 = 40 mmHg, HCO3- = 24 mEq/L) in a ratio of 10:3 or greater.

Additional measurements

Baseline characteristics used in the correlation analyses included age, sex, self-reported race, BMI, smoking pack-years and baseline lung function (percent-predicted values for forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)). Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) were included for correlational analysis if patients had a PFT completed within 6 months of the ABG collection date. All PFTs were performed in accredited hospital-based laboratories according to standardised technical specifications.11 12 Physiological obstruction was defined as FEV1/FVC <0.7. Patients with a room air ABG and room air SpO2 taken within 30 days of each other were included in the analyses assessing correlation of and difference between SaO2 and SpO2, with a secondary analysis considering only same-day tests. ILD diagnoses were assigned based on multidisciplinary assessment according to previous guidelines where available, grouping patients into five major categories of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTD-ILD), fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), unclassifiable ILD and other ILD.

Statistical analysis

Data shown are mean±SD, median (IQR) or number (%). All continuous variables included in multivariable analyses were scaled by a factor of 10. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All analyses were performed using Stata BE V.17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

The correlation between SaO2 and SpO2 was assessed using a Spearman correlation coefficient (r value), with the difference between SaO2 and SpO2 assessed using a paired t-test. The association of the difference between SaO2 and SpO2 with age, sex, race and baseline lung function (FVC and DLCO) was tested on unadjusted analysis using a Spearman’s rank correlation, followed by multivariable linear regression with the same baseline variables.

The associations of PaCO2 with each of age, sex, BMI, smoking pack-years and baseline lung function were tested on unadjusted analysis using linear and logistic regression for continuous and categorical PaCO2, respectively, as defined above. This was followed by multivariable linear regression and multivariable logistic regression, respectively, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, smoking pack-years and baseline lung function. Three separate adjusted models were completed with different baseline lung function measurements included due to collinearity between FVC and FEV1. The primary model included FVC and DLCO, with additional models including FEV1 and DLCO, and another with all three measurements. This was completed to assess whether FEV1, used as a surrogate for concomitant airways disease, may affect our results. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard regressions assessed whether PaCO2 was associated with time to death or transplant, with the multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking pack-years and baseline lung function (FVC and DLCO).

The association of acid-base category with age, sex, BMI, smoking pack-years and baseline lung function was tested on both unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression as well as with a multinomial model that assessed all acid-base categories. The same three adjusted models used in the PaCO2 regression analyses were used for each acid-base category regression analysis and the multinomial model. Regression analyses were completed if the acid-base category had ≥25 patients, with acute respiratory alkalosis, metabolic alkalosis, chronic respiratory acidosis and chronic respiratory alkalosis reaching this threshold. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard regressions assessed whether each acid-base category was associated with time to death or transplant, with the multivariable model adjusted for the same baseline variables used in the regression analyses.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

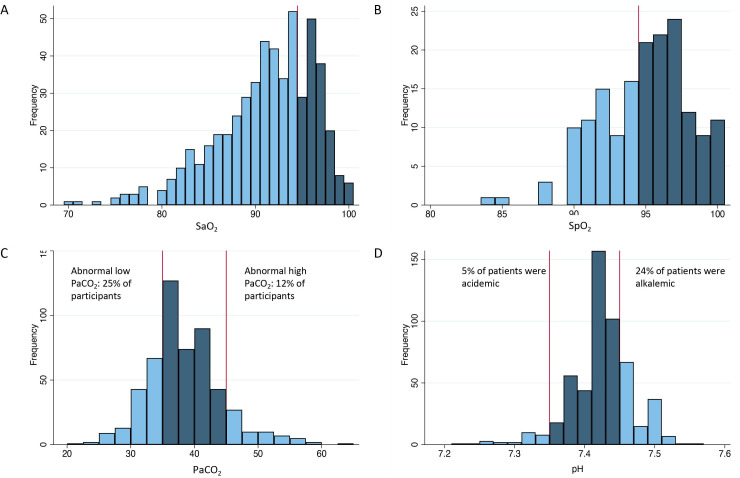

A total of 532 patients with an outpatient room air ABG were included (table 1). Median time from ILD diagnosis to performance of the ABG was 4 years (IQR 0.9–6.1), with 151 patients (28%) having the ABG drawn within the first year of ILD diagnosis. ABG characteristics are shown in figures 1 and 2. Mean SaO2 was 91±5% for the full cohort. Mean SaO2 was 92±4% and SpO2 was 95±3% for 105 patients with both an ABG and a corresponding room air SpO2. Mean PaCO2 was 38±6 mmHg, with 135 patients (25%) having PaCO2<35 mmHg and 62 patients (12%) having PaCO2 >45 mmHg. Of patients with elevated PaCO2, 7 patients (16%) had evidence of physiological obstruction compared with 40 patients (11%) without an elevated PaCO2. Of the 151 patients who had an ABG drawn within the first year of diagnosis, 7% had an elevated PaCO2 vs 9% of those who had the ABG drawn within the first 5 years of diagnosis and 11% for patients who had the ABG taken any time after 10 years of diagnosis. Mean pH was 7.43±0.05, with 155 patients (29%) having an abnormal pH, 27 of whom were acidotic (17%) and 128 alkalotic (83%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of entire cohort (N=532)

| Variable | Value |

| Age, years | 68 (59–74) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 299 (56) |

| Female | 233 (44) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 37 (7) |

| Black | 12 (1) |

| Indigenous | 24 (5) |

| White | 445 (85) |

| Other/missing† | 13 (2) |

| Smoking status | |

| Ever smoker | 372 (70) |

| Pack-years, smokers | 22 (9–38) |

| Pack-years, all | 11 (0–31) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29 (25–34) |

| ILD diagnosis category | |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 165 (31) |

| CTD-associated ILD | 149 (28) |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 67 (13) |

| Unclassifiable ILD | 100 (19) |

| Other ILD* | 51 (9) |

| Baseline lung function | |

| FVC %-predicted | 65±19 |

| FEV1 %-predicted | 69±19 |

| FEV1/FVC <0.7 | 48 (11) |

| DLCO %-predicted | 47±17 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 12 (2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 77 (14) |

| Congestive heart failure | 15 (3) |

Data shown are mean±SD, median (IQR) or n (%).

*Other ILD included drug-related ILD (n=3), vasculitis (n=5), cystic lung disease (n=8), infiltrative lung disease (n=3), acute respiratory distress syndrome (n=1), asbestosis (n=3), aspiration-related ILD (n=1), organising pneumonia (n=8), idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (n=1), respiratory-bronchiolitis ILD (n=2), radiation pneumonitis/ILD (n=1), other (n=15).

†Other race included Pacific Islander and Metis.

CTD, connective tissue disease; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ILD, interstitial lung disease.

Figure 1.

(A) Histogram of SaO2 values with a reference line at the boundary of normal. (B) Histogram of SpO2 values with a reference line at the boundary of normal. (C) Histogram of PaCO2 values with reference lines at boundaries of normal (35 and 45 mmHg). (D) Histogram of pH values with reference lines at boundaries of normal (7.35 and 7.45). Abnormal values are shown in light blue.

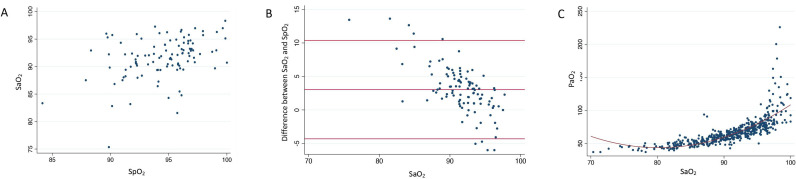

Figure 2.

(A) Scatter plot of room air SaO2 and paired room air SpO2 measured within 30 days of each other. (B) Scatter plot comparing paired SaO2 from room air arterial blood gas (ABG) and room air SpO2 taken within 30 days of each other. Red lines indicate mean difference and the corresponding 95% CI. (C) Scatter plot comparing paired SaO2 and PaO2 from room air ABG. Red line indicates the curve of best fit. A minor jitter function was added to all graphs to better display overlapping data points.

Association of SaO2 and SpO2

Room air SaO2 and SpO2 values were documented within 30 days of each other for 105 patients. SaO2 and SpO2 were moderately correlated (r=0.39, p<0.001; figure 2A), with SpO2 on average 3.0% higher than SaO2 for those with paired measurements (95% CI 2.3 to 3.7, p<0.001). For patients with an SpO2 ≥80%, 36% had an SpO2 that was within 2% of the SaO2. There was greater discordance between SaO2 and SpO2 with lower SaO2 values (r=–0.60 for association of SaO2 with the difference between SaO2 and SpO2, p<0.001) (figure 2B). Correlation between SaO2 and SpO2 was stronger (r=0.55) when limiting to measurements from the same day (online supplemental figure 1), with SpO2 on average 1.8% higher than SaO2 for those with same-day paired measurements (95% CI –3.5 to –0.2, p=0.02). On both unadjusted and adjusted analysis, none of age, sex, race, baseline FVC or baseline DLCO were associated with the difference between SaO2 and SpO2. Results were similar when restricting analyses to same-day measurements. As a surrogate for elevation, study site had no impact on study results. The non-linear association of SaO2 and PaO2 is shown in figure 2C.

bmjresp-2023-002250supp001.pdf (62.6KB, pdf)

Associations and prognostic significance of PaCO2

The association of PaCO2 with baseline variables is shown in table 2 (panels A, B). PaCO2 as a continuous variable was associated with FVC, FEV1 and smoking pack-years on unadjusted analysis (figure 3). On the primary adjusted analysis, only FVC and DLCO were independently associated with PaCO2 as a continuous variable. Compared with normal PaCO2, abnormal PaCO2 (either high or low) was associated with lower baseline FVC and FEV1 on unadjusted analysis, but only with lower FVC on the primary adjusted analysis. Results were not significantly different on the additional adjusted analyses in which FEV1 was either substituted for FVC or added to the primary adjusted model. PaCO2 as either a continuous or categorical variable was not associated with time to death or lung transplant on multivariable analysis.

Table 2.

(Panels A–B) Unadjusted analyses and the primary adjusted analysis of the association between baseline variables and PaCO2 as both a continuous and a categorical variable; (panels C–F) unadjusted analyses and the primary adjusted analysis of the association between baseline variables and each acid-base abnormality with ≥25 patients in each category.

| (A) | ||||||

| Variable | PaCO2 continuous | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| Coefficient | 95% CI | P value | Coefficient | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | –0.29 | –0.73 to 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.12 | –0.45 to 0.69 | 0.68 |

| BMI | 0.28 | –0.62 to 1.19 | 0.54 | 0.25 | –0.77 to 1.27 | 0.63 |

| Pack-years | –0.19 | –0.41 to 0.04 | 0.10 | –0.02 | –0.32 to 0.27 | 0.87 |

| Male sex | –0.28 | –1.31 to 0.75 | 0.59 | –0.64 | –1.94 to 0.66 | 0.33 |

| FVC | –1.07 | –1.35 to –0.79 | <0.001 | –1.28 | –1.67 to –0.88 | <0.001 |

| DLCO | 0.01 | –0.37 to 0.35 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 0.14 to 0.97 | 0.008 |

| (B) | ||||||

| Variable | Abnormal PaCO2 (high or low) | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.06 | 0.91 to 1.24 | 0.43 | 0.99 | 0.79 to 1.23 | 0.91 |

| BMI | 0.77 | 0.56 to 1.07 | 0.12 | 1.02 | 0.68 to 1.51 | 0.94 |

| Pack-years | 0.95 | 0.88 to 1.03 | 0.21 | 0.93 | 0.83 to 1.05 | 0.25 |

| Male sex | 1.24 | 0.87 to 1.77 | 0.24 | 1.31 | 0.79 to 2.16 | 0.29 |

| FVC | 1.15 | 1.04 to 1.28 | 0.008 | 1.22 | 1.05 to 1.43 | 0.01 |

| DLCO | 0.98 | 0.86 to 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.75 to 1.03 | 0.11 |

| (C) | ||||||

| Variable | Acute respiratory alkalosis | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.12 | 0.88 to 1.41 | 0.36 | 0.94 | 0.65 to 1.37 | 0.75 |

| BMI | 0.84 | 0.51 to 1.38 | 0.49 | 1.52 | 0.80 to 2.90 | 0.20 |

| Pack-years | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.57 | 0.99 | 0.83 to 1.18 | 0.91 |

| Male sex | 0.87 | 0.52 to 1.46 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 0.40 to 1.89 | 0.73 |

| FVC | 1.27 | 1.10 to 1.47 | 0.001 | 1.49 | 1.19 to 1.86 | 0.001 |

| DLCO | 1.06 | 0.88 to 1.29 | 0.54 | 0.89 | 0.70 to 1.13 | 0.34 |

| (D) | ||||||

| Variable | Metabolic alkalosis | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.35 | 0.98 to 1.85 | 0.07 | 1.38 | 0.81 to 2.36 | 0.24 |

| BMI | 1.15 | 0.63 to 2.12 | 0.65 | 1.62 | 0.74 to 3.56 | 0.23 |

| Pack-years | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.25 | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.37 | 0.34 |

| Male sex | 0.57 | 0.30 to 1.10 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.06 to 0.57 | 0.004 |

| FVC | 0.75 | 0.60 to 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.45 to 0.99 | 0.04 |

| DLCO | 0.73 | 0.53 to 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.69 | 0.45 to 1.04 | 0.08 |

| (E) | ||||||

| Variable | Chronic respiratory acidosis | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.11 | 0.77 to 1.60 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 0.56 to 1.54 | 0.77 |

| BMI | 1.38 | 0.65 to 2.90 | 0.40 | 2.32 | 0.97 to 5.55 | 0.06 |

| Pack-years | 0.97 | 0.94 to 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.50 to 1.08 | 0.12 |

| Male sex | 0.73 | 0.33 to 1.64 | 0.44 | 1.05 | 0.33 to 3.36 | 0.94 |

| FVC | 0.70 | 0.53 to 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.52 to 1.17 | 0.23 |

| DLCO | 1.02 | 0.75 to 1.35 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 0.74 to 1.54 | 0.74 |

| (F) | ||||||

| Variable | Chronic respiratory alkalosis | |||||

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.71 to 1.40 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.48 to 1.24 | 0.28 |

| BMI | 0.61 | 0.27 to 1.35 | 0.22 | 1.01 | 0.35 to 2.89 | 0.98 |

| Pack-years | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.81 to 1.31 | 0.79 |

| Male sex | 1.13 | 0.51 to 2.49 | 0.76 | 2.19 | 0.62 to 7.64 | 0.22 |

| FVC | 1.35 | 1.07 to 1.71 | 0.01 | 1.61 | 1.17 to 2.20 | 0.003 |

| DLCO | 0.91 | 0.667 to 1.23 | 0.54 | 0.80 | 0.56 to 1.12 | 0.19 |

Linear regression was used with PaCO2 as a continuous variable, and logistic regression with PaCO2 as a categorical variable (abnormal (<35 or >45 mmHg) and normal (35–45 mmHg)). Logistic regression was used for all analyses with the acid-base categories. Significant associations are bolded. All continuous variables were scaled by a factor of 10.

BMI, body mass index; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 3.

(A) Scatter plot of PaCO2 and baseline FVC percent. (B) Scatter plot of PaCO2 and baseline FEV1 percent. (C) Scatter plot of PaCO2 and smoking pack years. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Acid-base analyses

The association of each acid-base category with baseline variables is shown in table 2 (panels C–F). A total of 15 patients had an acute respiratory acidosis, 7 patients had a metabolic acidosis, 70 patients had an acute respiratory alkalosis, 41 patients had a metabolic alkalosis, 26 patients had a chronic respiratory acidosis and 28 patients had a chronic respiratory alkalosis.

On unadjusted analysis, both higher FVC and FEV1 were associated with an increased risk of an acute respiratory alkalosis (eg, for every 10% increase in FVC, there was a 1.12-fold increased likelihood of having an acute respiratory alkalosis). Both FVC and FEV1 remained significantly associated with acute respiratory alkalosis on their respective adjusted analyses.

On unadjusted analysis, lower FVC, FEV1 and DLCO were associated with an increased risk of metabolic alkalosis. In the primary adjusted analysis, FVC remained independently associated with an increased risk of metabolic alkalosis; however, no baseline lung function measurements retained statistical significance in the adjusted analysis that included all baseline lung function measurements.

Decreased FVC and FEV1 were associated with a greater frequency of a chronic respiratory acidosis on unadjusted analysis. On the primary adjusted analysis, no variables retained statistically significant association with a chronic respiratory acidosis. However, both FEV1 and BMI were associated with a chronic respiratory acidosis in the model with FEV1 substituted for FVC and in the model with all three baseline lung function measurements. Higher FVC was associated with an increased risk of a chronic respiratory alkalosis on both unadjusted and multivariable analyses.

In the primary multinomial model, FVC (OR 1.4, p=0.005) was associated with acute respiratory alkalosis, male sex (OR 0.18, p=0.003) and FVC (OR 0.65, p=0.04) were associated with metabolic alkalosis, no variables were associated with a chronic respiratory acidosis, and FVC (OR 1.61, p=0.002) was associated with a chronic respiratory alkalosis. In the multinomial model that substituted FEV1 for FVC, FEV1 (OR 1.39, p=0.009) was associated with acute respiratory alkalosis, male sex (OR 0.22, p=0.007) and DLCO (OR 0.63, p=0.03) were associated with metabolic alkalosis, BMI (OR 2.64, p=0.03) and FEV1 (OR 0.62, p=0.02) were associated with a chronic respiratory acidosis, and FEV1 (OR 1.45, p=0.03) was associated with a chronic respiratory alkalosis. In the multinomial model that included all three baseline lung function measurements, both BMI (OR 2.84, p=0.02) and FEV1 (OR 0.48, p=0.02) remained associated with a chronic respiratory acidosis, and only FVC (OR 2.02, p=0.03) was associated with a chronic respiratory alkalosis. None of the acid-base categories were associated with time to death or transplant on either unadjusted or multivariable analysis.

Discussion

We completed a retrospective chart review on a large prospective cohort to assess the clinical utility and potential limitations of pulse oximetry compared with ABG in patients with fibrotic ILD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the reliability of SpO2 as a surrogate of SaO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD, showing frequent but mostly minor differences in these values. This is also the first study to assess the clinical significance of abnormal PaCO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD, showing some association of abnormal PaCO2 with reduced lung function but without any substantial prognostic significance.

Contrary to our hypothesis, most patients (64%) had a difference between SaO2 and SpO2 of 3% or more. The correlation of SaO2 and SpO2 was 0.39 (considered weak to moderate) when these were measured within 30 days of each other, improving to only 0.55 when measured on the same day. This correlation is lower than other studies completed in other respiratory populations (typically r>0.88).2 However, some of the recent studies in COVID-19 have mixed results, with one study showing only a 1% discrepancy between SpO2 and SaO2 but others having much weaker correlation,13–15 suggesting the importance of evaluating specific diseases and subpopulations in future studies.16 In the general population, pulse oximetry is considered accurate to within 2% (±1 SD).2 Some factors that decrease reliability include hypoxaemia, low perfusion states, anaemia and darker skin pigmentation,3 7 17–20 with the potential that ILD-specific factors contribute to this greater discordance. We found that SpO2 tended to overestimate SaO2, and the variance was larger at lower levels of arterial oxygenation, which is consistent with most previous studies,2 but with no baseline characteristics other than SpO2 itself that were sufficiently associated with the magnitude of difference between SaO2 and SpO2 to be clinically useful. Another study showed that SpO2 ≤91% identified nearly all patients with fibrotic ILD who required long-term oxygen therapy,21 suggesting that patients with SpO2 >91% do not need testing for hypoxaemia even though there may still be substantial discordance with SaO2. Lastly, quality of life and depressive symptoms are worse in patients with IPF who have more advanced physiological abnormality, functional impairment, exercise tolerance and greater oxygen needs, thus suggesting the importance of appropriate management of hypoxaemia in patients with severe disease.22 23

There are limited data on PaCO2 levels and the predictors and clinical significance of abnormal PaCO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD. In our study, only 7% of patients early in their disease course (within 1 year of diagnosis) had elevated PaCO2 compared with 11% of patients when measured ≥10 years after diagnosis. This is consistent with a previous study showing that patients with fibrotic ILD are typically eucapneic, even with poor lung function, and that changes in PaCO2 are not related to spirometric values.24 This is contrary to other respiratory populations such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which has an inverse relationship between FEV1 and PaCO2.25–29 In our population, only decreased baseline FVC was a reliable predictor of elevated or abnormal PaCO2 and chronic respiratory acidosis in adjusted models.

Neither abnormal PaCO2 nor specific acid-base categories were associated with time to death or transplant in our analysis. This is in contrast to patients with obstructive lung disease, and particularly COPD in which higher PaCO2 is associated with worse disease severity.25 Additionally, chronic respiratory acidosis has several clinical consequences in COPD, including myocardial depression, arrhythmias, decreased peripheral vascular resistance and hypotension, respiratory muscle weakness and an increase in proinflammatory cytokines.30 The severity of acidosis is also associated with poor prognosis in COPD.31–38 For patients with restrictive lung disease, PaCO2 at time of lung transplant is associated with increased 1-year post-transplant mortality, and it is therefore used as part of the Lung Allocation Score.39 However, there are no data to our knowledge that confirm the clinical significance of abnormal PaCO2 values prior to transplant, suggesting that there is currently insufficient evidence to justify routine performance of ABG for assessment of acid-base status in patients with fibrotic ILD.

Due to our limited sample size, we analysed SaO2 and SpO2 values that were taken within 30 days of each other, rather than requiring these to be acquired on the same day. However, our results were similar when limiting to same-day measurements in patients who had concurrent measurements. A larger study is needed to further evaluate the correlation and difference between SaO2 and SpO2. We did not have any data on the type of pulse oximeter used, and other literature suggests variability in SpO2 between different brands of pulse oximeter. We did not have haemoglobin measured concurrent to the ABG and SpO2 values, so this variable was therefore excluded from the multivariable model. Future studies should evaluate whether anaemia alters the reliability of SpO2. We also lacked reliable data on skin colour and were further limited by small numbers of patients in some race subgroups. More careful assessment of skin colour would be helpful in future studies to better assess how skin pigmentation affects SpO2 accuracy. All our measurements were completed in a static environment; however, it would be of interest to test correlation of these values under both static and dynamic circumstances, particularly as SpO2 is often used in an exercise setting to determine which patients qualify for long-term oxygen therapy. Finally, we captured patients at variable durations since diagnosis. Although this increases heterogeneity, this also improves generalisability of findings.

In summary, we show only a weak-to-moderate correlation between SaO2 and SpO2 in patients with fibrotic ILD and frequent minor differences in these values, without any clinically useful predictors of a greater difference. These findings raise questions regarding the clinical utility of ABG and pulse oximetry in patients with ILD. As the field of ILD moves towards a precision medicine approach,40 this discordance of SpO2 and SaO2 highlights a potential pitfall in exclusively using SpO2 in the assessment of the treatable trait of hypoxaemia. This further emphasises the need for additional studies comparing and optimising these tests. Abnormal PaCO2 was associated with baseline FVC but was not prognostically informative. Collectively, these findings call attention to some of the limitations of ABGs in patients with fibrotic ILD, indicating the need for additional high-quality prospective studies to better characterise the potential clinical utility and performance characteristics of ABG in this patient population.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KerriBerriKerri

Presented at: This work was previously presented at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) International Conference in Washington, DC, USA, in May 2023 as a poster presentation titled ‘Characteristics of Arterial Blood Gas in Patients with Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease,’ and therefore published as an abstract in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Contributors: Study conception and guarantor: CJR. Funding acquisition: CJR. Study design: MAD, CJR. Data collection: All authors. Data analysis: MAD, D-CM, CJR. Data interpretation: All authors. Writing: MAD, CJR. Editing: All authors.

Funding: The CAnadian REgistry for Pulmonary Fibrosis (CARE-PF) is funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Competing interests: MAD reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript. KD reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript. DA reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Canadian Institute for Health Research and from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec en Santé. CD reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript. JHF reports personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. KJ reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pulmonary Fibrosis Society of Calgary, University of Calgary School of Medicine; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Three Lakes Foundation, Pliant Therapeutics, Theravance, Blade Therapeutics. MK reports grants from Canadian Institute for Health Research, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pieris, Prometic; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, European Respiratory Journal, Belerophon, United Therapeutics, Nitto Denko, MitoImmune, Pieris, AbbVie, DevPro Biopharma, Horizon, Algernon, CSL Behring. SDL reports consulting/personal fees and moderator honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, honoraria from Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, grants from AstraZeneca and the University of Saskatchewan. HM reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Gilead. VM reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Roche; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. BM reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript. JM reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. D-CM reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim. CJR reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Pliant Therapeutics, Cipla, Veracyte.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board approval #H22-00780. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Khor YH, Gutman L, Abu Hussein N, et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of hypoxemia in fibrotic interstitial lung disease: an international cohort study. Chest 2021;160:994–1005. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen LA, Onyskiw JE, Prasad NGN. Meta-analysis of arterial oxygen saturation monitoring by pulse oximetry in adults. Heart & Lung 1998;27:387–408. 10.1016/S0147-9563(98)90086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mardirossian G, Schneider RE. Limitations of pulse oximetry. Anesth Prog 1992;39:194–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebmeier SJ, Barker M, Bacon M, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximetry recordings in ICU patients: A two centre observational study of simultaneous pulse oximetry and arterial oxygen saturation recordings in intensive care unit patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 2018;46:297–303. 10.1177/0310057X1804600307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGovern JP, Sasse SA, Stansbury DW, et al. Comparison of oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry and co-oximetry during exercise testing in patients with COPD. Chest 1996;109:1151–5. 10.1378/chest.109.5.1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannhart B, Michalski H, Delorme N, et al. Reliability of six pulse oximeters in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1991;99:842–6. 10.1378/chest.99.4.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohyama T, Moriyama K, Kanai R, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximeters in detecting hypoxemia in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126979. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryerson CJ, Tan B, Fell CD, et al. The Canadian Registry for Pulmonary Fibrosis: design and rationale of a national pulmonary fibrosis registry. Canadian Respiratory Journal 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/3562923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher JH, Kolb M, Algamdi M, et al. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities in the Canadian Registry for Pulmonary Fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med 2019;19:223. 10.1186/s12890-019-0986-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro D, Patil SM, Keenaghan M. Arterial Blood Gas. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Barjaktarevic IZ, et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:E70–88. 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1600016. 10.1183/13993003.00016-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen LS, Helias M, Raia L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the association between pulse oximetry and arterial oxygenation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Rep 2022;12:1462. 10.1038/s41598-021-02634-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubano JA, Maloney LM, Simon J, et al. An evolving clinical need: discordant oxygenation measurements of intubated COVID-19 patients. Ann Biomed Eng 2021;49:959–63. 10.1007/s10439-020-02722-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson‐Baig N, McDonnell T, Bentley A. Discrepancy between SPO2 and SAO2 in patients with Covid‐19. Anaesthesia 2021;76:6–7. 10.1111/anae.15228 Available: https://associationofanaesthetists-publications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13652044/76/S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ntatsoulis K, Karampitsakos T, Tsitoura E, et al. Commonalities between ARDS, pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19: the potential of autotaxin as a therapeutic target. Front Immunol 2021;12:687397. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.687397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bickler PE, Feiner JR, Severinghaus JW. Effects of skin Pigmentation on pulse oximeter accuracy at low saturation. Anesthesiology 2005;102:715–9. 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cahan C, Decker MJ, Hoekje PL, et al. Agreement between noninvasive oximetry values for oxygen saturation. Chest 1990;97:814–9. 10.1378/chest.97.4.814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bothma PA, Joynt GM, Lipman J, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in pigmented patients. S Afr Med J 1996;86:594–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feiner JR, Severinghaus JW, Bickler PE. Dark skin decreases the accuracy of pulse oximeters at low oxygen saturation. Anesth Analg 2007;105:S18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes B, Sanchez-Martinez J, Fletcher L, et al. Use of pulse oximetry to select who should be screened for long term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in interstitial lung disease (ILD) patients. Eur Respir J 2014;44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreuter M, Swigris J, Pittrow D, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: Insights-IPF Registry. Respir Res 2017;18:139. 10.1186/s12931-017-0621-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzouvelekis A, Kourtidou S, Bouros E, et al. Impact of depression on patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERS International Congress 2017 abstracts; September 2017. 10.1183/1393003.congress-2017.PA357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javaheri S, Sicilian L. Lung function, breathing pattern, and gas exchange in interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1992;47:93–7. 10.1136/thx.47.2.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Miao X, Ding K, et al. The relationship of partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) with disease severity indicators such as BODE and GOLD in hospitalized COPD patients. Int J Clin Pract 2022;2022:4205079. 10.1155/2022/4205079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fard RM, Zarezadeh N. Relationship between FEV1 and PaO2, PaCO2 in patients with chronic bronchitis. Tanaffos 2004;3:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dave C, Wharton S, Mukherjee R, et al. Development and relevance of hypercapnia in COPD. Can Respir J 2021;2021:6623093. 10.1155/2021/6623093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez-Roisin R, Drakulovic M, Rodríguez DA, et al. Ventilation-perfusion imbalance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging severity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:1902–8. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00085.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saure EW, Eagan TML, Jensen RL, et al. Explained variance for blood gases in a population with COPD. Clin Respir J 2012;6:72–80. 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2011.00248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand IS, Chandrashekhar Y, Ferrari R, et al. Pathogenesis of congestive state in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: studies of body water and sodium, renal function, hemodynamics, and plasma hormones during edema and after recovery. Circulation 1992;86:12–21. 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffrey AA, Warren PM, Flenley DC. Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease: risk factors and use of guidelines for management. Thorax 1992;47:34–40. 10.1136/thx.47.1.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoo GW, Hakimian N, Santiago SM. Hypercapnic respiratory failure in COPD patients: response to therapy. Chest 2000;117:169–77. 10.1378/chest.117.1.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kettel LJ, Diener CF, Morse JO, et al. Treatment of acute respiratory acidosis in chronic obstructive lung disease. JAMA 1971;217:1503–8. Available: https://jamanetwork.com/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren PM, Flenley DC, Millar JS, et al. Respiratory failure revisited: acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis between 1961-68 and 1970-76. Lancet 1980;1:467–70. 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plant PK, Owen JL, Elliott MW. Early use of non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on general respiratory wards: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:1931–5. 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02323-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onadeko BO, Khadadah M, Abdella N, et al. Prognostic factors in the management of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract 2005;14:35–40. 10.1159/000081921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Budweiser S, Jörres RA, Riedl T, et al. Predictors of survival in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure receiving noninvasive home ventilation. Chest 2007;131:1650–8. 10.1378/chest.06-2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ucgun I, Oztuna F, Dagli CE, et al. Relationship of metabolic alkalosis, azotemia and morbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypercapnia. Respiration 2008;76:270–4. 10.1159/000131707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egan TM, Murray S, Bustami RT, et al. Development of the new Lung Allocation System in the United States. Am J Transplant 2006;6:1212–27. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khor YH, Cottin V, Holland AE, et al. Treatable traits: a comprehensive precision medicine approach in interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2023;62:2300404. 10.1183/13993003.00404-2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2023-002250supp001.pdf (62.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.