Abstract

Objective

To characterise subphenotypes of self-reported symptoms and outcomes (SRSOs) in postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC).

Design

Prospective, observational cohort study of subjects with PASC.

Setting

Academic tertiary centre from five clinical referral sources.

Participants

Adults with COVID-19 ≥20 days before enrolment and presence of any new self-reported symptoms following COVID-19.

Exposures

We collected data on clinical variables and SRSOs via structured telephone interviews and performed standardised assessments with validated clinical numerical scales to capture psychological symptoms, neurocognitive functioning and cardiopulmonary function. We collected saliva and stool samples for quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA via quantitative PCR.

Outcomes measures

Description of PASC SRSOs burden and duration, derivation of distinct PASC subphenotypes via latent class analysis (LCA) and relationship with viral load.

Results

We analysed baseline data for 214 individuals with a study visit at a median of 197.5 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. Participants reported ever having a median of 9/16 symptoms (IQR 6–11) after acute COVID-19, with muscle-aches, dyspnoea and headache being the most common. Fatigue, cognitive impairment and dyspnoea were experienced for a longer time. Participants had a lower burden of active symptoms (median 3 (1–6)) than those ever experienced (p<0.001). Unsupervised LCA of symptoms revealed three clinically active PASC subphenotypes: a high burden constitutional symptoms (21.9%), a persistent loss/change of smell and taste (20.6%) and a minimal residual symptoms subphenotype (57.5%). Subphenotype assignments were strongly associated with self-assessments of global health, recovery and PASC impact on employment (p<0.001) as well as referral source for enrolment. Viral persistence (5.6% saliva and 1% stool samples positive) did not explain SRSOs or subphenotypes.

Conclusions

We identified three distinct PASC subphenotypes. We highlight that although most symptoms progressively resolve, specific PASC subpopulations are impacted by either high burden of constitutional symptoms or persistent olfactory/gustatory dysfunction, requiring prospective identification and targeted preventive or therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: COVID-19, virology, respiratory infections

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Prospective cohort study with inclusive patient population with postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) symptomatology from different clinical sources and index severity of COVID-19.

Structured telephone interviews and standardised assessments with validated clinical numerical scales.

Unsupervised clustering analysis for data-driven derivation of PASC subphenotypes.

Analyses based on self-reported symptoms and outcomes of a cohort with 214 participants, without available data on physiological or imaging measurements.

Analysis of non-invasive biospecimens for viral persistence may have missed viral signal in deep-seeded tissues.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound global impact on public health. The multiorgan involvement of SARS-CoV-2 infection highlights the critical need to understand the postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) and the long-term consequences on patients’ well-being and functionality.1 PASC, commonly referred to as long COVID, encompasses a wide range of clinical definitions, presentations and diverse trajectories.2–4 While most COVID-19 patients recover from their acute illness within a few weeks, PASC is estimated to affect 10%–20% of COVID-19 survivors across all ages.2 3 5 6 Notably, PASC can manifest in patients with severe acute COVID-19 as well as those with milder initial disease, with up to 4 million Americans unable to return to work, regardless of the severity of their acute illness, according to many reports.2 7 Large cohort studies have shown that PASC can contribute substantially to disability-adjusted life years by 2 years postinfection, with a persistent health burden in diverse populations.8

Postulated mechanisms for PASC include viral, host, environmental and treatment factors.9 10 The persistence of a SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in various tissue types, even months after acute COVID-19, is supported by both autopsy and tissue biopsy data revealing RNA and protein remnants of the virus in numerous tissues.11 The existence of this reservoir suggests the potential to influence host immune responses or release of viral proteins into the circulation. Extensive research also supports a multifaceted immune dysregulation with PASC.12 Circulating myeloid and lymphocyte populations in individuals with PASC exhibit marked differences compared with controls, alongside exaggerated humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 and elevated antibody responses to non-SARS-CoV-2 pathogens, notably Epstein-Barr virus. Subjects with PASC have also been shown to have significantly reduced systemic cortisol levels, without compensatory rise in adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, indicating a potentially impaired hypothalamic-pituitary axis response. Further research also demonstrates multisystem tissue damage, dysregulation of clotting and coagulation, dysfunctional brainstem/vagus nerve signalling and dysautonomia.13 Therefore, the evolving understanding of the phenotypic heterogeneity of PASC may reflect biological heterogeneity in the underlying mechanisms. The absence of standardised phenotyping has resulted in gaps in understanding prognosis for PASC and in developing effective preventive or therapeutic strategies.

We leveraged our clinical and research infrastructure to characterise subphenotypes of self-reported symptoms and outcomes (SRSOs) in subjects with PASC, identify factors associated with persistent PASC phenotypes and investigate mechanisms of biological heterogeneity related to viral persistence.

Methods

Study cohort

We conducted the post-COVID-19 impairment phenotyping and outcomes (post-CIPO) study, a prospective, observational cohort study with longitudinal follow-up of adult (aged ≥18 years) subjects with PASC-related SRSOs. We used an inclusive case definition of PASC, defined as the experience of any new or persistent symptoms for at least 20 days following a documented COVID-19 illness by positive quantitative PCR (qPCR). We enrolled patients from five different sources (see online supplemental file 1 for details), classified as inpatients versus outpatients at the time of COVID-19 illness. We pursued enrolment of participants from different sources, including patients who had been previously enrolled in acute COVID-19 studies as well as patients self-referred to this PASC investigation or referred by their physicians, or identified as eligible during clinical encounters in a post-COVID-19 clinic at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). This inclusive enrolment strategy was chosen for both feasibility purposes to reach a large sample size as well as to capture different populations at varying risks of PASC subtypes and severity. Following informed consent, we conducted a baseline study visit via structured telephone interviews during which we collected data on demographics, comorbid conditions, timeline of the previous COVID-19 illness(es), vaccinations and treatments received and then types/duration/severity of 16 PASC-related symptoms. We selected the 16 specific symptoms based on expert input and knowledge on PASC symptomatology at the time of cohort inception. These symptoms included fever, chills, muscle aches, ‘runny nose’, sore throat, cough, dyspnoea (‘shortness of breath’), nausea or vomiting, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, loss/change of smell, loss/change of taste, cognitive impairment (‘brain fog’), fatigue and chest issues (pain or palpitations), with detailed questionnaires provided in the Supplement. We conducted standardised assessments with validated clinical numerical scales to capture the following domains of function and symptomatology: (i) psychological symptoms: Generalised Anxiety Scale-7 (GAD7) for anxiety14; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) for depression15; Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) for insomnia,16 (ii) neurocognitive functioning: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-BLIND)17 and (iii) cardiopulmonary function: Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) Dyspnoea scale.18 We also asked participants questions for self-assessment of their overall PASC outcomes in terms of global health, recovery and impact on employment. For the purposes of this study, only baseline visit data were analysed.

bmjopen-2023-077869supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Biospecimen acquisition and molecular analyses

Following the study visit, subjects self-collected stool and saliva samples at a single time point that were stored in nucleic acid preservation media and mailed to our laboratory. We aliquoted specimens and stored them at −80°C until conduct of experiments. We quantified SARS-CoV-2 viral load in available biospecimens with one-step quantitative real-time PCR of the SARS-CoV-2 N gene and human RNaseP gene.19 20

Statistical analyses

We examined data for distribution and missingness (online supplemental figure S1). To examine for presence of distinct subphenotypes (classes) of SRSOs, we conducted unsupervised classification with latent class analysis (LCA) of self-reported symptoms at baseline visit in two separate analyses21: (i) we used symptoms experienced at any time post-COVID-19 (‘ever-experienced’) as input variables to examine retrospectively for ‘epidemiological clusters’ (LCA-1) and (ii) we used active symptoms at the time of the baseline visit to stratify subjects into ‘clinically active clusters’ (LCA-2). We examined model fit performance by calculating membership probability, entropy and the parametric bootstrapped log likelihood ratio between different classes, as well as a clinical relevance criterion of ensuring that each class has at least 5% of observations from the cohort. Results from the quantitative scales (GAD7, PHQ9, ISI, MoCA-BLIND, MMRC) were then mapped to each cluster across LCA-1 and LCA-2 analyses for a descriptive assessment of those data by cluster assignment. To examine whether cluster membership could be predicted by baseline clinical covariates, we used least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression models (with 10-fold validation) with clinical covariates as predictors and clusters as outcomes. We conducted subgroup analyses for inpatients and outpatients, separately. We performed non-parametric comparisons for continuous (described as median and IQR) and categorical variables between different groups and reported the nominal p values for all tests performed, with adjustments for multiple comparisons with a conservative Bonferroni correction for all comparisons between clinical groups. From available stool and saliva samples, we examined differential levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool and saliva samples by SRSOs and PASC subphenotypes. We conducted analyses in R (V.4.2.0), STATA V.17.0 and Mplus V.8.8.

Results

Cohort description

From March 2021 through January 2023, we enrolled a feasibility cohort of 214 individuals with PASC through various referral sources, when subjects reported symptoms consistent with PASC or sought care for PASC (table 1). The study visit took place at a median of 197.5 (IQR 143.0–323.2) days following COVID-19 diagnosis. Patients who were hospitalised during their acute COVID-19 illness (32% inpatients, table 1) were older, with higher burden of comorbid conditions, and were interviewed closer to their COVID-19 diagnosis compared with outpatients (all p<0.01, table 1). The UPMC post-COVID-19 clinic was the most common referral source to the post-CIPO study (31.8%, online supplemental table S1). Participants enrolled through the post-COVID-19 clinic or who were self-referred to the study were younger and with fewer comorbid conditions compared with patients referred from inpatient or outpatient studies of acute COVID-19 or referred by physicians for PASC (online supplemental table S1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 214 subjects included with postacute sequelae of COVID-19, stratified by inpatient versus outpatient status during acute COVID-19

| Variable | All | Outpatients | Inpatients | P value |

| Participants | 214 | 143 | 71 | |

| Age (median (IQR)), years | 49.9 (38.5, 62.3) | 44.1 (34.4, 54.6) | 62.0 (51.6, 68.5) | <0.0001* |

| Men (%) | 57 (26.6) | 30 (21.0) | 27 (38.0) | 0.01 |

| Whites (%) | 196 (91.6) | 132 (92.3) | 64 (90.1) | 0.78 |

| Body mass index (median (IQR)) | 30.0 (25.1, 34.7) | 28.9 (24.1, 33.6) | 31.3 (27.0, 36.6) | 0.01 |

| Inpatients (%) | 71 (33.2) | 0 (0.0) | 71 (100.0) | <0.0001* |

| No college-level degree (%) | 101 (47.2) | 56 (39.2) | 45 (63.4) | <0.0013* |

| Hypertension (%) | 75 (35.0) | 43 (30.1) | 32 (45.1) | 0.04 |

| Diabetes (%) | 32 (15.0) | 8 (5.6) | 24 (33.8) | <0.0001* |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 8 (3.7) | 3 (2.1) | 5 (7.0) | 0.16 |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (9.9) | <0.0006* |

| Stroke (%) | 9 (4.2) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (11.3) | <0.0010* |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 13 (6.1) | 3 (2.1) | 10 (14.1) | <0.0016* |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea (%) | 54 (25.2) | 23 (16.1) | 31 (43.7) | <0.0001* |

| Obstructive airways disease (%) | 60 (28.0) | 35 (24.5) | 25 (35.2) | 0.14 |

| History of cancer (%) | 11 (5.1) | 6 (4.2) | 5 (7.0) | 0.58 |

| History of immunosuppression (%) | 33 (15.4) | 15 (10.5) | 18 (25.4) | 0.01 |

| Anaemia (%) | 35 (16.4) | 16 (11.2) | 19 (26.8) | 0.01 |

| Ever smoker (%) | 80 (37.4) | 47 (32.9) | 33 (46.5) | 0.07 |

| Vaccinated for influenza (%) | 140 (65.4) | 97 (67.8) | 43 (60.6) | 0.37 |

| Vaccinated for COVID-19 (%) | 122 (57.0) | 81 (56.6) | 41 (57.7) | 0.99 |

| No. of COVID-19 vaccinations (median (IQR)) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.44 |

| Antiviral treatment during acute COVID-19 (%) | 33 (15.4) | 4 (2.8) | 29 (40.8) | <0.0001* |

| Prevalent SARS-CoV-2 variant during each acute infection period | <0.0001* | |||

| Wild type | 73 (34.1) | 32 (22.4) | 41 (57.7) | |

| Alpha | 73 (34.1) | 53 (37.1) | 20 (28.2) | |

| Delta | 37 (17.3) | 29 (20.3) | 8 (11.3) | |

| Omicron | 31 (14.5) | 29 (20.3) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Days since acute COVID-19 infection date (median (IQR)) | 197.5 (143.0, 323.2) | 221.0 (155.5, 350.5) | 161.0 (123.5, 238.0) | <0.009* |

We present continuous variables as median and IQR and categorical variables as number (%). We compared continuous variables with Wilcoxon tests and categorical variables with Fisher’s exact tests. We consider p<0.05 as statistically significant. We performed multiple testing adjustments with the Bonferroni test for 24 tests included in these comparisons.

*Statistically significant results following adjustment by multiple comparisons (p<0.002).

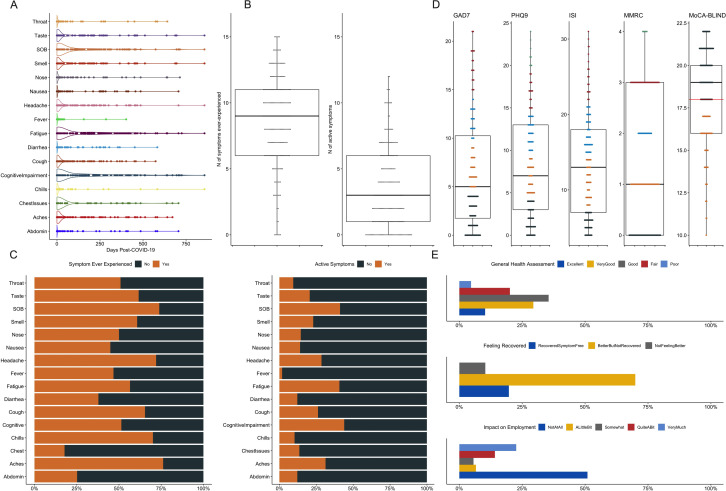

Baseline SRSOs

We first examined symptoms ‘ever-experienced’ post-COVID-19 and how long they lasted. Overall, participants endorsed a median of 9 symptoms (IQR 6–11) out of the total 16 symptoms in our questionnaire, with muscle aches, dyspnoea and headache being the most common ones (reported by >70% of participants). Distributions of the duration of these symptoms (expressed as estimated number of days for each symptom post-COVID-19) were highly right skewed (figure 1A), with fatigue, cognitive impairment and dyspnoea experienced for longer periods of time among those who reported these symptoms. At the time of baseline visit, participants endorsed a lower burden of active symptoms (median 3 (IQR 1–6)) compared with those ‘ever-experienced’ symptoms (median 9 (IQR 6–11) paired Wilcoxon test p<0.001, figure 1B). The most common active symptoms at time of baseline visit were dyspnoea, fatigue and cognitive impairment (reported by >40% of participants, figure 1C). The numerical scales examined from baseline visit (figure 1D) showed that more than half of participants reported mild anxiety or depression (GAD7 >4 or PHQ9 >4, respectively) while 42.5% reported moderate or severe insomnia and 43.6% reported clinically significant dyspnoea (MMRC ≥2). For objective neurocognitive testing, 34.4% had an abnormal MoCA-BLIND test (<18). For the self-assessment of outcomes, 39.7% deemed their general health as excellent or very good, 20% felt that they had fully recovered from COVID-19, whereas 49.6% reported that their employment ability had been affected to various degrees by PASC (figure 1E). We found significant associations of clinical covariates with active symptoms and clinical scales (online supplemental figures S2–S7), with COVID-19 vaccination associated with lower scores for depression, anxiety and insomnia, and higher odds for feelings of full recovery (online supplemental figure S8).

Figure 1.

Self-reported symptoms and outcomes among 214 subjects with postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) at baseline visit. (A) Distribution of the duration (in days) of each of the 16 interviewed symptoms post-COVID-19. (B) Subjects reported a median of 9 (IQR 6–11) ‘ever-experienced’ symptoms and a median of 3 (IQR 1–6) active symptoms at baseline visit. (C) Stacked bar showing the proportions of presence (‘yes’ in orange) versus absence (‘no’ in grey) for each of the 16 interviewed symptoms, with ‘ever-experienced’ symptoms shown in the left panel and active symptoms in the right panel. (D) Distributions of the numerical scales examined in the baseline visit: Generalised Anxiety Scale-7 (GAD7) for anxiety; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) for depression; Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) for insomnia, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-BLIND) for neurocognitive functioning and Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) Dyspnoea scale for cardiopulmonary function. An abnormal MoCA-BLIND test was defined as score of <18 (red line). (E) Self-assessed outcomes of general health (top panel), recovery from COVID-19 (middle panel) and impact of COVID-19 on employment (bottom panel). SOB: shortness of breath (dyspnoea).

PASC subphenotypes

In the ‘epidemiological cluster’ analysis, we conducted LCA by using symptoms ‘ever-experienced’ post-COVID-19 as input variables (LCA-1). LCA-1 revealed that a three-class model offered optimal fit (online supplemental table S2), with about equal distribution between the three classes (clusters, online supplemental table S3). Cluster 1 (31.3%) had markedly higher symptom burden, followed by cluster 2 (39.3%), whereas cluster 3 (29.4%) was an overall low symptom burden PASC subgroup (online supplemental figure S9A). More than 50% of cluster 1 subjects had experienced 15/16 symptoms (except for chest issues), whereas nearly all cluster 2 subjects reported loss/change of smell and taste (online supplemental figure S9B). Cluster 1 subjects had higher scores in scales for anxiety, depression and insomnia but no difference in neurocognitive scale (online supplemental figure S9C). We found no significant differences between clusters by baseline covariates (online supplemental table S3), but cluster membership was significantly associated with the self-assessed impact of PASC on employment (online supplemental figure S10).

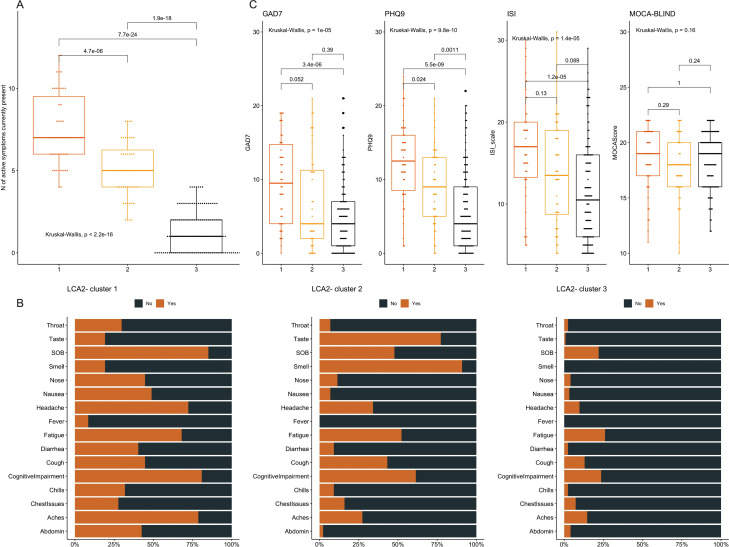

Next, we performed a ‘clinically active’ LCA by using active symptoms (LCA-2). LCA-2 also revealed that a three-class model offered optimal fit (online supplemental table S2), but subjects were now less evenly distributed (online supplemental table S4). Cluster 1 (21.9%) contained patients with higher symptom burden than cluster 2, but cluster 2 (20.6%) was distinguished by its high proportion of patients reporting a persistent loss of taste and smell (figure 2A). Cluster 3 included subjects that were now minimally symptomatic (57.5%). Cluster 1 subjects had higher scores for anxiety, depression and insomnia scales, but no difference in the neurocognitive MoCA-BLIND scale (figure 2C), despite 81% self-reporting cognitive impairment. Notwithstanding the lower burden of active symptoms in cluster 2 compared with cluster 1 (figure 2A, p<0.001), clusters 1 and 2 had similarly poor outcomes in terms of subjective recovery and impact on employment (online supplemental figure S11).

Figure 2.

Distributions of symptoms and numerical scales by the ‘clinically active’ subphenotypes of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). We conducted latent class analysis (LCA) by using the 16 active symptoms at baseline visit as input variables (‘LCA2’). (A) Cluster 1 subjects (21.9%) had significantly higher number of active symptoms compared with cluster 2 subjects (20.6%), who in turn had much higher number of symptoms compared with cluster 3 (57.5%). (B) Stacked bar showing the proportions of presence (‘yes’ in orange) versus absence (‘no’ in grey) for each of the 16 interviewed symptoms for each of the three clusters. (C) Cluster 1 subjects had much higher scores for the numerical scales Generalised Anxiety Scale-7 (GAD7) for anxiety, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) for depression and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) for insomnia, but no difference in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-BLIND) score for neurocognitive functioning. Number of symptoms and numerical scales between clusters were compared with a global Kruskal-Wallis test, and then pairwise comparisons with Wilcoxon tests adjusted for multiple testing with the Bonferroni correction. Only adjusted p values by the Bonferroni method are displayed. SOB: shortness of breath (dyspnoea).

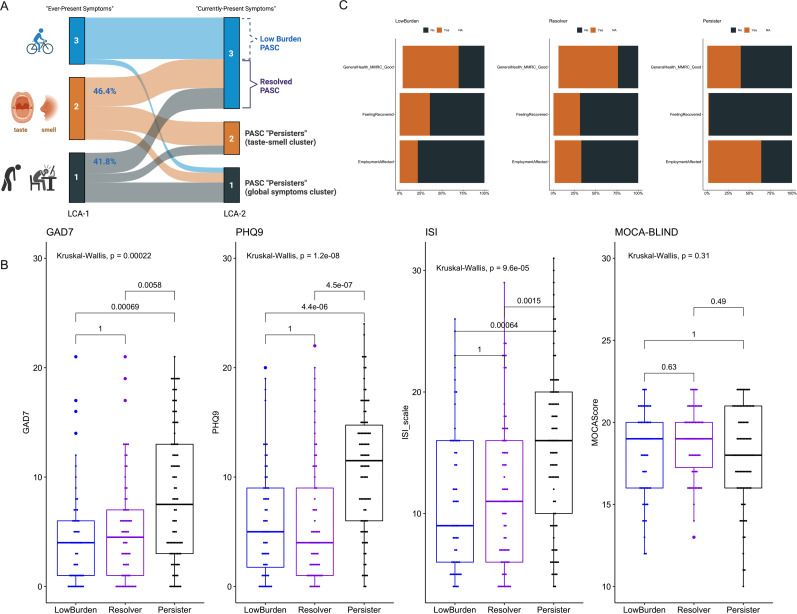

We then integrated the results from the two clustering approaches (LCA-1 and LCA-2) to understand how subjects transitioned over time from the epidemiological (LCA-1) to the ‘clinically active’ (LCA-2) classifications. LCA-1 and LCA-2 cluster memberships were strongly associated (McNemar’s paired test p<0.001), with notable transitions between clusters (figure 3A). A majority of cluster 3 subjects in the LCA-1 (88.9%) were also classified as cluster 3 by LCA-2, representing a population with consistently low number of PASC symptoms (‘low burden PASC’). Among subjects placed in clusters 1 and 2 by LCA-1, we noted that 41.8% of the multisymptomatic cluster 1 and 46.4% of the predominantly impaired taste/smell cluster 2 were classified as cluster 3 by LCA-2, representing a population who was highly symptomatic at some point post-COVID-19, but reported a low symptom burden by the time of the baseline visit. Thus, we considered such subjects transitioning to LCA-2 cluster 3 as representative of ‘resolved PASC’. Subjects classified as clusters 1 and 2 by LCA-2 represented a population of ‘PASC persisters’ (42.5%), either for the continued impairment of taste/smell in cluster 2 or for multiple symptoms in cluster 1 (figure 3A). ‘PASC persisters’ had significantly worse clinical scales for anxiety, depression and insomnia than ‘low burden’ (26.2%) or ‘PASC resolvers’ (31.3%), but no difference in the neurocognitive MoCA-BLIND scale (figure 3B). ‘PASC persisters’ reported significantly worse outcomes for subjective recovery and impact on employment compared with ‘low burden’ or ‘PASC resolvers’ (p<0.001, figure 3C). We found no significant differences in baseline covariates between these integrative PASC clusters, other than ‘PASC persisters’ having a lower proportion of vaccination (49.5%) compared with ‘low burden’ or ‘PASC resolvers’ (66.1% and 59.7%, respectively; p<0.001, table 2).

Figure 3.

Integrative clustering analysis revealed a subset of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) ‘persisters’ with high symptom burden, poor self-assessment outcomes and high numerical scales for anxiety, depression and insomnia. (A) Transitions between the two clustering approaches (latent class analysis (LCA)-1 and LCA-2). LCA-1 analysed ‘ever-experienced’ symptoms (epidemiological subphenotyping), whereas LCA-2 analysed active symptoms (‘clinically active’ subphenotyping). Most cluster 3 subjects by LCA-1 (88.9%) were also classified as cluster 3 by LCA-2 (‘low burden PASC’). Among subjects in clusters 1 and 2 by LCA-1, 41.8% of the multisymptomatic cluster 1 and 46.4% of the taste/smell predominant cluster 2 were classified as cluster 3 by LCA-2 (‘resolved PASC’). Subjects classified as clusters 1 and 2 by LCA-2 represented a population of ‘PASC persisters’, either for taste/smell predominant cluster 2 or the multisymptomatic cluster 1. (B) ‘PASC persisters’ had significantly worse scales for anxiety, depression and insomnia than ‘low burden’ or ‘PASC resolvers’, but no difference in the neurocognitive MoCA-BLIND scale. (C) ‘PASC persisters’ reported significantly worse outcomes for global health assessment, subjective recovery and impact on employment compared with ‘low burden’ or ‘PASC resolvers’ (p<0.001). Numerical scales between clusters were compared with a global Kruskal-Wallis test, and then pairwise comparisons with Wilcoxon tests adjusted for multiple testing with the Bonferroni correction. Only adjusted p values by the Bonferroni method are displayed.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics by integrative clusters of methods LCA-1 and LCA-2 through which we defined the subphenotypes of persisters, resolvers or low burden subjects with PASC

| Variable | Low burden | Resolver | Persister | P value |

| Participants | 56 | 67 | 91 | |

| Age (median (IQR)) | 56.6 (36.3, 67.8) | 49.4 (33.9, 57.9) | 50.0 (41.4, 61.7) | 0.08 |

| Men (%) | 18 (32.1) | 19 (28.4) | 20 (22.0) | 0.37 |

| Whites (%) | 48 (85.7) | 61 (91.0) | 87 (95.6) | 0.11 |

| Body mass index (median (IQR)) | 30.0 (25.6, 34.4) | 29.3 (25.3, 34.1) | 30.2 (25.1, 35.3) | 0.77 |

| Inpatients (%) | 27 (48.2) | 20 (29.9) | 24 (26.4) | 0.02 |

| No college-level degree (%) | 28 (50.0) | 26 (38.8) | 47 (51.6) | 0.25 |

| Hypertension (%) | 23 (41.1) | 20 (29.9) | 32 (35.2) | 0.43 |

| Diabetes (%) | 11 (19.6) | 7 (10.4) | 14 (15.4) | 0.36 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (4.4) | 0.48 |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0.57 |

| Stroke (%) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.0) | 4 (4.4) | 0.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (4.5) | 5 (5.5) | 0.56 |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea (%) | 13 (23.2) | 15 (22.4) | 26 (28.6) | 0.62 |

| Obstructive airways disease (%) | 11 (19.6) | 19 (28.4) | 30 (33.0) | 0.22 |

| History of cancer (%) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (4.5) | 5 (5.5) | 0.96 |

| History of immunosuppression (%) | 9 (16.1) | 8 (11.9) | 16 (17.6) | 0.62 |

| Anaemia (%) | 9 (16.1) | 11 (16.4) | 15 (16.5) | 1 |

| Ever smoker (%) | 23 (41.1) | 19 (28.4) | 38 (41.8) | 0.18 |

| Vaccinated for influenza (%) | 37 (66.1) | 46 (68.7) | 57 (62.6) | 0.73 |

| Vaccinated for COVID-19 (%) | 37 (66.1) | 40 (59.7) | 45 (49.5) | 0.12 |

| No. of COVID-19 vaccinations (median (IQR)) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.02 |

| Antiviral treatment during acute COVID-19 (%) | 12 (21.4) | 11 (16.4) | 10 (11.0) | 0.23 |

| Prevalent SARS-CoV-2 variant during each acute infection period | <0.002* | |||

| Wild type | 13 (23.2) | 28 (41.8) | 32 (35.2) | |

| Alpha | 4 (7.1) | 13 (19.4) | 20 (22.0) | |

| Delta | 10 (17.9) | 13 (19.4) | 8 (8.8) | |

| Omicron | 29 (51.8) | 13 (19.4) | 31 (34.1) | |

| Days since acute COVID-19 infection date (median (IQR)) | 186.5 (140.8, 279.0) | 181.0 (125.5, 319.0) | 214.0 (146.5, 372.0) | 0.24 |

We present continuous variables as median and IQR and categorical variables as number (%). We compared continuous variables with Kruskal-Wallis tests and categorical variables with Fisher’s exact tests. We consider p<0.05 as statistically significant. We performed multiple testing adjustments with the Bonferroni test for 24 tests included in these comparisons.

*Statistically significant results following adjustment by multiple comparisons (p<0.002).

Clinical predictors of PASC subphenotypes

Following derivation of PASC subphenotypes, we examined whether clinical covariates available at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis may predict PASC cluster membership with LASSO models. LASSO regression models found no significant predictors for the epidemiological clusters (LCA-1). For the clinically active clusters (LCA-2), LASSO regression revealed that higher body mass index (BMI), lower education level, history of anaemia and autoimmune disease increased the risk for the multisymptomatic cluster 1 membership, whereas history of COVID-19 hospitalisation, COVID-19 vaccination and infection with the delta variant were protective against cluster 1 membership (online supplemental table S5).

Viral persistence and SRSOs

We measured SARS-CoV-2 RNA (vRNA) load in 103 saliva samples and 101 stool samples available. We found detectable vRNA in six saliva (5.8%) and one (1.0%) stool sample. Therefore, we were able to perform exploratory analyses comparing viral positive and negative samples for saliva only (6 vs 97 samples, respectively, online supplemental table S6). Subjects with viral positive saliva samples had donated samples closer to their acute COVID-19 diagnosis (median of 133 vs 188 days, p<0.001), were more likely to have received antiviral treatment during acute COVID-19 (p=0.04), but otherwise had no significant differences in individual symptoms or cluster membership compared with subjects with negative viral load (online supplemental table S7).

Sensitivity analyses

We acknowledge that the definition of PASC has evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic, and our operational definition involved a shorter time period following the index date of the acute COVID-19 illness (≥20 days) compared with subsequent definitions by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (symptoms occurring ≥4 weeks or 28 days post-COVID-19)22 and WHO (symptoms occurring ≥3 months or 90 days).23 In a post hoc analysis, application of the CDC definition had no impact on the eligible cohort for analysis, because the shorter time period from index date to enrolment was 31 days. Application of the WHO definition would have resulted in exclusion of 21 subjects (9.8% of the cohort) who had been enrolled within 90 days from index date of acute COVID-19 illness (online supplemental figure S12). Exclusion of these subjects did not impact the distribution of the LCA clusters.

We also sought to understand whether the different enrolment sources for subjects into our cohort had an impact on the distribution of the PASC subphenotypes. Notably, we found significant differences in distribution of LCA-1, LCA-2 clusters and ‘persistent’ versus ‘resolved’ PASC by referral source (online supplemental figure S13). Patients who were followed from an original encounter during acute COVID-19 (inpatient registry or acute outpatient studies) had significantly lower proportions of the highly symptomatic cluster 1 (by LCA-1 and LCA-2) and ‘persistent’ PASC compared with patients that were referred to the study (by their physicians or self-referred) or who were enrolled in the post-COVID-19 clinic at UPMC (all p<0.0001, online supplemental figure S13). This analysis confirmed that there are distinct subpopulations among patients who meet the PASC definition, with much higher symptomatic burden and persistence of symptoms among patients seeking care for PASC or being referred to PASC investigations.

Discussion

Our study examined subphenotypes of SRSOs in an inclusive cohort of subjects with PASC. Our findings demonstrate the heterogeneous nature of PASC, with varying symptomatology, functional impairments and time course. Through unsupervised analysis of 16 self-reported symptoms, we identified 3 distinct PASC subphenotypes. Our results suggest that individuals evaluated for PASC at different time intervals after COVID-19 comprise discrete subpopulations of symptom burden and duration, with likely differing underlying disease mechanisms and care needs. The first subphenotype was characterised by high symptom burden (cluster 1), whereas the second subphenotype was distinguished by disturbances of smell and taste (cluster 2). Most subjects showed low symptom burden or had resolved PASC by the time of baseline visit (cluster 3). Most subjects in clusters 1 and 2 felt that they have not recovered from PASC, which impacted their employment. We investigated oral and gastrointestinal viral persistence as potential biological mechanisms for PASC, but overall found a low prevalence of detectable viral RNA in saliva and stool samples.

To better understand how COVID-19 survivors were feeling and functioning, we conducted structured telephone interviews enrolling individuals at various time intervals post-COVID-19. Subjects with PASC reported a median of nine symptoms that were ‘ever experienced’ since contracting COVID-19, with individual symptom durations being notably long. By the time of the baseline visit, which was conducted at a median of 197.5 days post-COVID-19, most symptoms had resolved, leading to a phenotype of low symptom burden or resolved PASC for most subjects. Nevertheless, 42.5% of participants displayed persistent PASC (clusters 1 and 2 in LCA-2), with poor self-assessment of health and recovery, as well as adverse impact on employment. PASC ‘persisters’ had higher scores for anxiety, depression and insomnia, and reported much higher prevalence of cognitive impairment, despite showing similar scores on objective neurocognitive scale testing, which may have not been detailed enough to capture more subtle neurocognitive deficits. Therefore, even among patients who are referred or personally seek care for PASC at some point after COVID-19, it is the subset of ‘persisters’ (42.5% in our cohort) that has high symptom burden and impaired functional outcomes that may warrant specific evaluation and treatment.

Among PASC ‘persisters’, we identified a distinct cluster with disturbances of smell and taste. Such disturbances varied from decreased or absent smell or taste to distorted or putrid sensations, which are common during acute COVID-19, and are also increasingly recognised as components of PASC with variable recovery trajectories seen in different studies.4 24 A recent large multicentre cohort study identified four PASC clusters, of which one cluster was defined by the persistence of smell and taste disturbances in all included subjects,3 highlighting the external validity of our clustering analysis. The proposed mechanisms of persistent olfactory and/or gustatory dysfunction involve conductive and sensorineural deficits, likely due to acute mucosal or neuronal damage during acute COVID-19.25 Therefore, these patients represent a distinct PASC subtype, which may require much different biological study and testing of interventions compared with other PASC clusters with constitutional symptoms and cognitive impairments.3 Nonetheless, we recognise that olfactory and gustatory symptoms have shown reduced prevalence with more recent Omicron variants.26 Our study population included infections from all major variants during the first 2 years of the pandemic, but we only included a small population of patients likely to have been infected by Omicron variants (14.5%). Updated analyses of populations at risk for PASC infected by SARS-CoV-2 in 2022 and 2023 will offer more insights with regard to the prevalence and clinical impact of a ‘smell and taste’ PASC cluster.

To improve subject identification for PASC studies enriched for highly symptomatic subjects, we conducted LASSO modelling to define predictors of PASC subphenotypes. We selected clinical variables that were easily accessible from electronic medical record reviews or subject interviews, as well as variables that had face value for PASC associations based on univariate analyses with SRSOs or LCA clusters. We found that a simple clinical model based on BMI, education level, anaemia, immune disease, hospitalisation, vaccination and delta variant infection accurately predicted cluster 1 membership by LCA-2. Concordant to recent evidence,3 27 our analyses also showed that vaccination was associated with lower probability of assignment to a multisymptomatic PASC cluster. Although external validation in larger datasets is required to establish generalisability of the prognostic value of such models, our analysis suggests that clinical variables available at the time of acute COVID-19 infection may aid in prioritising follow-up and study enrolment for subjects who are more likely to develop highly symptomatic and persistent PASC.

Our molecular analyses of non-invasive biospecimens with a sensitive qPCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 RNA19 20 showed overall low prevalence of viral persistence (5.8% for saliva and 1% for stool samples). The six subjects with viral positive saliva samples had donated samples at a median of 133 days following their acute COVID-19 diagnosis, and none of them reported a COVID-19 re-infection. Although such viral RNA detection does not prove ongoing viral replication or infectivity, we note that the studies of inpatients with COVID-19 have shown much shorter durations of saliva viral positivity (eg, a median of 18 days).28 The small sample size of positive saliva samples in our cohort did not allow us to perform robust testing of associations between viral load and PASC SRSOs or subphenotypes. We could not draw any inferences about viral persistence in other body reservoirs. However, our results allow us to conclude that viral RNA quantification in non-invasive biospecimens is unlikely to explain the observed PASC heterogeneity, and that future study of PASC needs to consider different biospecimens for viral persistence as well as additional biological mechanisms.9

Our study has several limitations. First, we relied solely on SRSOs, which may be biased by both over-reporting and under-reporting in ways that we could not test for. We did not conduct objective physiological tests, such as pulmonary function tests or neuro-imaging, which could have provided a more comprehensive understanding of PASC. Nonetheless, our analysis of self-reported symptom onset, duration and severity provided important insights into the broad spectrum of symptomatology experienced post-COVID-19. At the same time, we examined for symptoms experienced post-COVID-19, but could not distinguish as to whether some of the reported symptoms related to exacerbation of pre-existing conditions, such as chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia. Furthermore, the symptomatology questionnaire we used was extensive but not exhaustive, and we have thus not included important symptoms relating to dysautonomia, which has been increasingly recognised as a pathophysiological mechanism of PASC. Our study had a relatively small sample size of 214 participants, which may have limited our ability to detect further subphenotypes of PASC, whereas some of the reported associations between covariates, clusters and outcomes may be prone to type I error. Therefore, we applied conservative corrections for multiple testing for all reported associations and interpreted results that remained statistically significant following such adjustments.

We included participants from five different sources, which may have introduced selection biases and affected the generalisability of our findings. For instance, we observed lower PASC symptom burden in hospitalised patients who had more severe acute COVID-19 than outpatients. However, this does not suggest that severe acute COVID-19 is protective against PASC, but rather that the outpatients enrolled in our PASC cohort are likely to have a higher burden of PASC symptoms. Furthermore, we observed significantly increased burden of highly symptomatic PASC as well as ‘persistent PASC’ in subjects who were enrolled through a post-COVID-19 clinic or via physician referral to our study, who represented ~50% of our study population. Our study was thus enriched for severely symptomatic patients with PASC, and our results may not directly generalise to all survivors of acute COVID-19, although we made efforts to balance enrolment and increase representation of patients not specifically seeking care for PASC. Our cohort also consisted predominantly of white participants, which represents the demographics of the population in the catchment area, but may not necessarily represent specific subpopulations (eg, communities of colour) that may be at higher risk for PASC. Consequently, we urge caution when interpreting the observed associations. Finally, it is important to recognise that the PASC burden and impact on individuals’ lives can vary widely, and our findings may not be generalisable to all patients with PASC.

In summary, our study sheds light on the clinical heterogeneity of PASC. We identified distinct PASC subphenotypes driven by symptomatology type and burden. We show that viral persistence in non-invasive biospecimens has low prevalence and does not explain SRSOs or PASC subphenotypes. Our approach to PASC subphenotyping provides a reproducible framework for capturing a wide spectrum of SRSOs and identifying clinical subtypes with adverse impact on patient-centred end points. Future research on PASC should focus on developing and validating predictive models for timely identification of COVID-19 survivors who are at high risk of persistent PASC, as well as targeting mechanistic study and interventional trials in distinct subsets of patients with either high burden of constitutional symptoms or persistent olfactory/gustatory dysfunction.

bmjopen-2023-077869supp002.pdf (104.9KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Michael Flock, PhD at the University of Pittsburgh, who provided invaluable assistance in project coordination and grant contracting. The authors would also like to thank all study participants for their contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: GDK, SMN, AM. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: GDK, SB, JJJ, TM, AN, HG, CK, XW, KG, HQ, AD, MR, MB, BE, EW, CB, LJ, FD, ES, JWM, BM, FCS, SMN, AM. Final approval of the version to be published: GDK, SB, JJJ, TM, AN, HG, CK, XW, KG, HQ, AD, MR, MB, BE, EW, CB, LJ, FD, ES, JWM, BM, FCS, SMN, AM. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: GDK, SB, JJJ, TM, AN, HG, CK, XW, KG, HQ, AD, MR, MB, BE, EW, CB, LJ, FD, ES, JM, BM, FCS, SMN, AM. The acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: SB, JJJ, TM, AN, HG, CK, XW, KG, HQ, AD, MR, MB, BE, EW, CB, LJ, FD, ES, JWM, BM, FCS, SMN, AM. Article guarantor: GDK.

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant from Pfizer to the University of Pittsburgh.

Competing interests: GDK has received research funding from Karius and Genentech, unrelated to this work. GDK, AM, JM, FCS and SMN have received funding from Pfizer.

JWM is a consultant to Gilead Sciences, Inc. and has received grant funding from Gilead Sciences, Inc., to the University of Pittsburgh; receives compensation from Galapagos NV; and, holds share options in Galapagos NV, Infectious Disease Connect, Inc., and MingMed Biotechnology Co., Ltd., all unrelated to the current work.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by University of Pittsburgh IRB (STUDY21010001). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021;27:601–15. 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Mahoney LL, Routen A, Gillies C, et al. The prevalence and long-term health effects of long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2023;55:101762. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a definition of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA 2023;329:1934–46. 10.1001/jama.2023.8823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballouz T, Menges D, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Recovery and symptom trajectories up to two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: population based, longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2023;381:e074425. 10.1136/bmj-2022-074425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlis RH, Santillana M, Ognyanova K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of long COVID symptoms among US adults. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2238804. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selvakumar J, Havdal LB, Drevvatne M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics associated with post-COVID-19 condition among nonhospitalized adolescents and young adults. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e235763. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlis RH, Lunz Trujillo K, Safarpour A, et al. Association of post-COVID-19 condition symptoms and employment status. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2256152. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.56152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequelae of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nat Med 2023;29:2347–57. 10.1038/s41591-023-02521-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21:133–46. 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki A, Putrino D. Why we need a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of long COVID. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23:393–5. 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00053-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proal AD, VanElzakker MB, Aleman S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat Immunol 2023;24:1616–27. 10.1038/s41590-023-01601-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein J, Wood J, Jaycox JR, et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 2023;623:139–48. 10.1038/s41586-023-06651-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherif ZA, Gomez CR, Connors TJ, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Elife 2023;12:e86002. 10.7554/eLife.86002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297–307. 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawes P, Pye A, Reeves D, et al. Protocol for the development of versions of the Montreal cognitive assessment (Moca) for people with hearing or vision impairment. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026246. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580–6. 10.1378/chest.93.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs JL, Bain W, Naqvi A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 Viremia is associated with Coronavirus disease 2019 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74:1525–33. 10.1093/cid/ciab686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs JL, Naqvi A, Shah FA, et al. Plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels as a biomarker of lower respiratory tract SARS-CoV-2 infection in critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Infect Dis 2022;226:2089–94. 10.1093/infdis/jiac157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha P, Calfee CS, Delucchi KL. Practitioner’s guide to latent class analysis: methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Crit Care Med 2021;49:e63–79. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health . National research action plan on long COVID, 200 Independence Ave SW. Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. 2021.

- 24.Tan BKJ, Han R, Zhao JJ, et al. Prognosis and persistence of smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: meta-analysis with parametric cure modelling of recovery curves. BMJ 2022;378:e069503. 10.1136/bmj-2021-069503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan CJ-W, Tan BKJ, Tan XY, et al. Neuroradiological basis of COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2022;132:1260–74. 10.1002/lary.30078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Bartheld CS, Wang L. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction with the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cells 2023;12:430. 10.3390/cells12030430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsampasian V, Elghazaly H, Chattopadhyay R, et al. Risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2023;183:566–80. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chopoorian A, Banada P, Reiss R, et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva: implications for late-stage diagnosis and infectious duration. PLoS ONE 2023;18:e0282708. 10.1371/journal.pone.0282708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-077869supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-077869supp002.pdf (104.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.