Abstract

Objectives

Experience of psychosocial environments by workers entering trade apprenticeships may differ by gender. We aimed to document perceived harassment and to investigate whether this related to mental ill-health.

Methods

Cohorts of workers in welding and electrical trades were established, women recruited across Canada and men from Alberta. Participants were recontacted every 6 months for up to 3 years (men) or 5 years (women). At each contact, they were asked about symptoms of anxiety and depression made worse by work. After their last regular contact, participants received a “wrap-up” questionnaire that included questions on workplace harassment. In Alberta, respondents who consented were linked to the administrative health database that recorded diagnostic codes for each physician contact.

Results

One thousand eight hundred and eighty five workers were recruited, 1,001 in welding trades (447 women), and 884 in electrical trades (438 women). One thousand four hundred and nineteen (75.3%) completed a “wrap up” questionnaire, with 1,413 answering questions on harassment. Sixty percent of women and 32% of men reported that they had been harassed. Those who reported harassment had more frequently recorded episodes of anxiety and depression made worse by work in prospective data. In Alberta, 1,242 were successfully matched to administrative health records. Those who reported harassment were more likely to have a physician record of depression since starting their trade.

Conclusions

Tradeswomen were much more likely than tradesmen to recall incidents of harassment. The results from record linkage, and from prospectively collected reports of anxiety and depression made worse by work, support a conclusion that harassment resulted in poorer mental health.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, harassment, prospective studies, workplace

What is important about this paper?

This study found that the majority of women entering the male-dominated trades of welding and electrical work report harassment, particularly during their apprenticeship, and that the harassment is largely from coworkers and has a sexual component. There is increasing recognition that workplace harassment of any worker is unacceptable, with obligations on the employer to take action to eliminate it. Evidence of ongoing mental health impacts reinforces this obligation.

Introduction

Although it has been recognized for many years that women entering the trades may find the workplace culture challenging (Bridges et al. 2020), there are few quantitative studies to document risks to their safety or mental health. Curtis et al. (2018) provided data on the experiences of women and men in the construction trades and record rates of bullying in women, which were twice that in men. Harassment, the focus of the current report, differs from bullying in that it may include single events not necessarily entailing a power imbalance (Einarsen 2000). As such, it would be expected that the prevalence of harassment would be greater than that of bullying, which was estimated by Nielsen et al. (2010) to be 14.8% worldwide. Given the high rates of sexual harassment in tradeswomen, reported by Curtis et al. (2018), the harassment rates in women entering the trades, although largely unknown, are of concern.

Few opportunities arise to compare the employment experiences of women and men, closely matched by type of work. Studies of differential harassment have largely been conducted in large organizations with women in a minority (at least in certain roles) including among physicians (Frank et al. 1998), the military (Street et al. 2007), and firefighters (Jahnke et al. 2019). The WHAT-ME cohort (Cherry et al. 2018) comprised women and men recruited from welding and electrical trades and followed at 6-month intervals for up to 5 years. Although much of the study focus was on particulate and metal exposures (Galarneau et al. 2022), reproductive, and other health outcomes (Cherry et al. 2021; Cherry et al. 2022), a final questionnaire included questions on workplace harassment, which is the focus of this report. The structure of the cohort, with large numbers of tradeswomen closely matched to men in the same work, allows us to address outstanding questions about the prevalence and nature of harassment of women in the skilled trades and its relationship to mental ill-health (Rudkjoebing et al. 2020).

The analysis reported here had 3 objectives. The first was to describe and compare the reported experiences of workplace harassment in women and men, closely matched on type of work, in trades traditionally entered by men. The second was to use the data collected prospectively on anxiety and depression made worse by work to contribute to discussion of the effects of harassment on mental ill-health, acknowledging that interpretation of such data as causal is fraught with uncertainties Third, taking advantage of data linkage to administrative health records, to assess the relation of self-reported harassment to prospectively collected physician reports of mental ill-health, so removing the element of health self-report.

Women in the welding and electrical trades in Canada

Women make up only a small proportion of skilled workers in the welding and electrical trades in Canada. Data from the 2021 Canadian census suggests that only 4.1% of those in the technical metal working trades (largely welders) were women and only 3.2% in the electrical trades (Statistics Canada 2023). Apprenticeship data from 2016 to 2020 showed higher rates, with on average 8.3% of welding apprentices recorded as female and 4.2% of apprentices in the electrical trades. During this period 48% of Canadian women welding apprentices and 24% in the electrical trades were registered in Alberta (Statistics Canada 2021). While only 12% of Canadians live in Alberta, the province’s focus on the energy and extraction industries creates a strong demand for skilled labor and an openness to employing women in the trades.

Methods

Cohort recruitment and follow-up

Four cohorts were set up, of women and men who had started an apprenticeship in a welding or electrical trade since 2005, as previously described (Cherry et al. 2018). Recruitment of women began in January 2011 and of men in January 2014. To recruit sufficient women to address questions about reproductive outcomes, women were recruited from every Canadian province or territory, men just from Alberta. Participants were recontacted every 6 months after recruitment for up to 3 years (men) or 5 years (women). Questionnaires were completed online or by telephone, in English or French. Along with questions on work, reproductive history, and health, at each contact participants were asked if they were experiencing symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, dermatitis, shoulder pain, back pain, Raynaud’s phenomenon, anxiety, or depression, and whether these were made worse by work (questions 1.1 to 1.8 supplementary materials 1). After a participant had completed their last regular contact, they were sent a final “wrap-up” questionnaire that included the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Bjelland et al. 2002), questions on ethnicity (question 6.3 in supplementary materials 2) sexual orientation and gender identity (question 6.4), use of recreational drugs (questions 6.5–6.8), and workplace harassment (questions 4.1–4.43). A shorter version of the “wrap-up” was used for those whose contact since baseline had been intermittent. No payment was made for participation in the study overall, but participants were paid $20 Canadian for returning this final short form. The section on harassment was less structured for this group (question 5.1 in supplementary materials 3).

Measurement of exposure to harassment

The full questionnaire asked separately about harassment during two time periods: the apprenticeship and during work in the trade as a certified tradesperson. Respondents were asked: during your apprenticeship were you (i) ever subjected to psychological harassment; (ii) ever subjected to physical violence; (iii) ever subjected to sexual harassment? with parallel questions for the post-apprenticeship period. A positive answer to any of these defined “harassment” as used in this report. Those who reported harassment were asked structured questions about each type of harassment and given open-text fields in which to provide details, if they wished. Inspection of the open-field responses suggested that the pre-coded options did not always accurately represent the events described and all responses, including those from the short questionnaire, were coded using a standard scheme, allowing for interpretation and incorporation of open-ended comments. The coding noted the work role of the harasser, the type of harassment, and the response of the participant. In those few instances, where it was unclear, on the short questionnaire, whether an event occurred during or after apprenticeship, it was assigned to the apprenticeship period; initial inspection of responses from the long questionnaire suggested it was rare for a respondent to report harassment once a journeyperson in the absence of such incidents during apprenticeship. Recoding of open-text fields was used only to reflect the details reported. All reports of harassment were retained as the exposure variable of interest.

Measurement of mental ill-health

At each periodic contact, the respondent was asked: do you have days when you feel sad, empty or depressed most of the time? Do you have days when you feel worried or anxious most of the time? If the respondent said yes to either, they were asked: Was this made worse by work? These questions were added after the recruitment of women had started. They were present for all men but missing for one or more contacts for women recruited before April 2013. Such reports of symptoms are referred to as a “periodic anxiety report” or “periodic depression report”. The analysis included, as the first key outcome, reports of anxiety or depression symptoms made worse by work.

In Alberta, information on mental ill-health prior joining the trade and in the years since the start of trade work was available from linkage to the Alberta administrative health database for those who gave consent. In Alberta health care is free at the point of service. To be paid by the provincial health care insurance plan, a physician has to record at least one diagnosis. With ethical approval and participant consent these data can be made available for research. Physician reports for 1 April 2002–31 March 2018 were extracted. Four variables were constructed (i) any diagnosis of an anxiety, stress, or adjustment disorder: International Classification of Disease 9th Revision (ICD-9): 300.0 to 300.3, 300.5 to 300.9 308.0 to 308.9, 309.0 to 309.9: ICD-10: F40 to F43, F45, F48 before the date of joining the trade (ii) any diagnosis of an anxiety, stress, or adjustment disorder since the date of joining the trade (iii) any diagnosis of a depressive disorder (ICD-9: 300.4 311; ICD-10: F32, F33, F34.1) before the date of joining the trade, and (iv) any diagnosis of a depressive disorder since the date of joining the trade.

The second key outcome for the Alberta sub-cohort was a physician diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive condition at any time since joining the trade.

Measurement of confounders and effect modifiers

The HADS was completed during the long form of the wrap-up questionnaire. It includes 7 questions for anxiety and 7 for depression using a 4-point scale (0 to 3), with a score for each subscale ranging from 0 to 21. The preamble asked respondents to consider how they had been feeling in the last week. In this analysis, the scores obtained at the end of the study were used as a surrogate for scores that would have been obtained before entering the trade, had that been possible, and so to adjust for a personal characteristic that might relate to reporting harassment. Such an approach is conservative in that it does not allow for changes to HADS scores that might have arisen through harassment.

Other potential confounders were trade (welding or electrical) and gender (woman or man) recorded by the apprenticeship board. For the Alberta sub-cohort, a physician’s diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive condition at any time before joining the trade was included as a potential effect modifier.

Statistical methods

Prevalence of reporting any harassment since starting in the trade was calculated overall and for women and men by trade, by period of employment (apprenticeship or as a certified tradesperson). Episodes reported as harassment were examined by the work role of the harasser (supervisor or coworker) and by whether or not the incident included a sexual component. Effects on mental health were examined by the proportion of questionnaires on which the respondent recorded having symptoms of periodic anxiety or periodic depression made worse by work. This was calculated as a percentage of the total responses for that participant. As participants had periods not working or working in other jobs, computation of episodes made worse by work included only those in their trade at the time of reporting. A probit (fractional) regression examined factors associated with the proportion of periodic reports of anxiety or depression made worse by work. Multilevel multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the relation of reported harassment to episodes of anxiety or depression made worse by work. Differences by gender were explored by stratification. Further logistic regression analyses, using data from the administrative health database, took as the outcome variables physician-recorded anxiety or depressive disorders, with reported harassment as the exposure of interest and adjusting for the same disorder recorded in the health database before joining the trade. The analyses were carried out in Stata (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Recruitment and completion

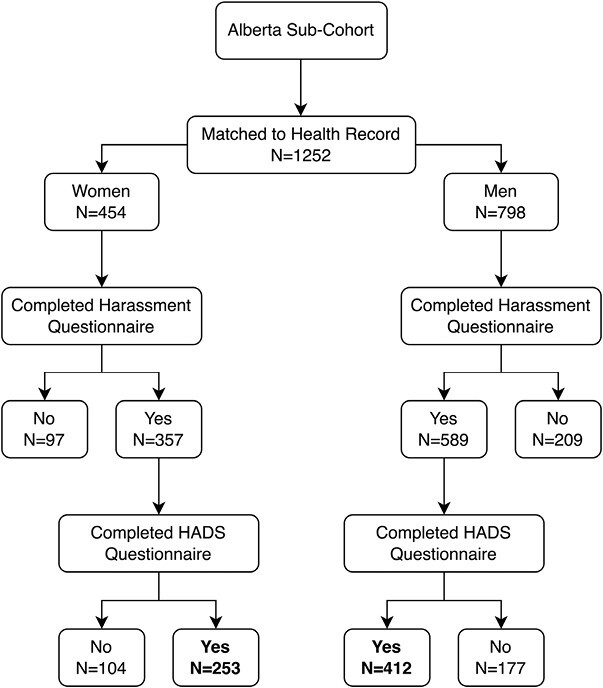

One thousand eight hundred and eighty-five tradespeople completed the baseline (recruitment) questionnaire, 1,001 in welding trades, and 884 in electrical trades. Four hundred and forty-seven in welding were women with 438 in the electrical trades. Mean age at starting the apprenticeship was 25.5 years. In the whole cohort, 75.0% (1413/1885) completed the harassment section on either the long (976) or short (437) follow-up questionnaire, including 691 women (Fig. 1). There were 1,252 in the Alberta sub-cohort data linked with the administrative health database: 946/1,252 (75.6%) answered the harassment questions (Fig. 2). Almost all (97%) of those completing the harassment questions on the long questionnaire also completed the HADS questionnaire (948/976 in the whole cohort 665/686 in the Alberta sub-cohort). Of those completing the long questionnaire, 45 identified as Indigenous People, 43 identified as LGBTQ+, and 88 reported using recreational drugs at least weekly.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the main study cohort.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart for the Alberta sub-cohort.

Reports of harassment

Overall (Table 1) 45.3% reported that at some time since starting their trade, they had experienced harassment. The proportions were similar for welding (47.1%) and electrical trades (43.5%) but markedly higher for women (59.5%) than men (31.7%). Among those completing the long “wrap up,” the proportions reporting harassment during apprenticeship were similar to the overall estimate (62.1% in women, 32.3% in men) but lower for the period “in trade” (48.3% in women, 22.9% in men). Those identifying as Indigenous People reported somewhat greater harassment overall (62.2%; Fisher’s exact test: P = 0.126) as did those identifying as LGBTQ+ (69.8%; Fisher’s exact test P = 0.012) or being frequent users of recreational drugs (61.4%; Fisher’s exact test: P = 0.033). More women than men reported being harassed by their supervisor and, particularly, by coworkers (50% of women and 22% of men during their apprenticeship). Other harassers were mentioned much less frequently. Much of the reported harassment had a sexual component with 44% of women reporting this in relation to their apprenticeship and 28% once qualified and working in the trades (Table 1).

Table 1.

Report of harassment by gender, trade, type of harassment, and employment period.

| Harassment period | All | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Harassed = yes | % | N | Harassed = yes | % | N | Harassed = yes | % | |

| Anya | |||||||||

| Welding | 709 | 334 | 47.1 | 336 | 205 | 61.0 | 373 | 129 | 34.6 |

| Electrical | 704 | 306 | 43.5 | 355 | 206 | 58.0 | 349 | 100 | 28.7 |

| Both | 1413 | 640 | 45.3 | 691 | 411 | 59.5 | 722 | 229 | 31.7 |

| During apprenticeshipb | |||||||||

| Welding | 454 | 210 | 46.3 | 206 | 128 | 62.1 | 248 | 82 | 33.1 |

| Electrical | 520 | 246 | 47.3 | 269 | 167 | 62.1 | 251 | 79 | 31.5 |

| Both | 974 | 456 | 46.8 | 475 | 295 | 62.1 | 499 | 161 | 32.3 |

| Who? | |||||||||

| Supervisor | 974 | 265 | 27.2 | 475 | 157 | 33.3 | 499 | 108 | 21.6 |

| Coworker | 974 | 348 | 35.7 | 475 | 237 | 50.2 | 499 | 111 | 22.2 |

| How? | |||||||||

| Sexual | 974 | 224 | 23.0 | 475 | 208 | 43.8 | 499 | 16 | 3.2 |

| In trade, post-apprenticeshipb | |||||||||

| Welding | 359 | 136 | 37.9 | 156 | 82 | 52.6 | 203 | 54 | 26.6 |

| Electrical | 433 | 140 | 32.3 | 217 | 98 | 45.2 | 216 | 42 | 19.4 |

| Both | 792 | 276 | 34.8 | 373 | 180 | 48.3 | 419 | 96 | 22.9 |

| Who? | |||||||||

| Supervisor | 792 | 146 | 18.4 | 373 | 82 | 22.0 | 419 | 64 | 15.3 |

| Coworker | 792 | 196 | 24.7 | 373 | 139 | 37.3 | 419 | 57 | 13.6 |

| How? | |||||||||

| Sexual | 792 | 109 | 13.8 | 373 | 105 | 28.2 | 419 | 4 | 1.0 |

aThose completing the long or short harassment questions.

bThose completing the long harassment questions only.

Harassment, anxiety and depression at the final contact

Among those who had completed the HADS questionnaire as part of the final contact, participants reporting harassment had higher scores on both the anxiety and depression scales, with similar patterns for men and women (top panel of Table 2).

Table 2.

Anxiety and depression from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and proportion of periodic reports by report of anxiety or depression made worse by work by harassment reported on “wrap-up” questionnaire.

| Any report of harassment | HADS score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | ||||||

| N | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | |

| Women | |||||||

| No | 163 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

| Yes | 300 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.5 |

| All | 463 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 3.2 |

| Men | |||||||

| No | 313 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 3.1 |

| Yes | 172 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 4.1 |

| All | 485 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| Overall | |||||||

| No | 476 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Yes | 472 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

| All | 948 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| Report of harassment | All with periodic reports while in trade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of reports with anxiety made worse by work (%) | Proportion of reports with depression made worse by work (%) | ||||||

| N a | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | |

| Women | |||||||

| No | 131 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 15.7 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 13.3 |

| Yes | 246 | 0.0 | 21.6 | 31.8 | 0.0 | 15.3 | 27.4 |

| All | 377 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 28.1 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 24.1 |

| Men | |||||||

| No | 288 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 18.4 |

| Yes | 157 | 14.3 | 24.7 | 30.2 | 0.0 | 18.7 | 29.4 |

| All | 445 | 0.0 | 15.5 | 25.4 | 0.0 | 11.6 | 23.5 |

| Overall | |||||||

| No | 419 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 19.4 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 17.1 |

| Yes | 403 | 0.0 | 22.8 | 31.2 | 0.0 | 16.6 | 28.2 |

| All | 822 | 0.0 | 16.0 | 26.7 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 23.8 |

Note: All HADS scores for those reporting and not reporting harassment differed with P < 0.001.

aParticipants completing the HADS questionnaire and periodic reports while in trade.

Harassment and periodic reports of anxiety and depression made worse by work

The average number of questionnaires with a response to questions about periodic anxiety and depression was 5.2 (median 6) for men and 4.6 (median 4) for women, reflecting the late inclusion of the question for women and their greater likelihood of leaving the trade or taking time away for childbirth or other reasons. At the time of the “wrap-up” questionnaire, 25% (182/722) of men but 43% (296/691) of women reported not currently working in their trade. While in their trade 37.8% (168/445) of men reported at least once that they had anxiety made worse by work and 28.3% (126/445) depression made worse by work. The proportions for women were similar, 35.5% (134/377) and 25.2% (95/377). Those reporting harassment on the “wrap-up” questionnaire had a higher proportion of periodic episodes made worse by work. This was seen for both women and men (lower panel of Table 2). In a fractional regression analysis, the proportions made worse by work were significantly higher for those reporting harassment (Table 1 in supplementary materials 4).

The higher proportion with symptoms made worse by work could have arisen either from reporting more anxiety or depression, without increased work attribution, or from the same levels of anxiety or depression but with a greater attribution to work. Table 3 considers first the relationship between periodic anxiety and depression and reported harassment. The odds ratio for harassment was always greater than 1.00 but not significantly so for anxiety in women. Type of trade did not contribute (except marginally for depression in women welders). Men were more likely than women to have periodic reports of anxiety, having adjusted for HADS anxiety score. The lower part of Table 3 gives the odds that a reported episode of anxiety or depression would be attributed to work. Here, reported harassment was strongly related to work attribution of both anxiety and depression overall and in women. For men, while the odds ratios were clearly above 1 (1.67 for anxiety and 1.53 for depression) these had a probability >0.05. Age did not add to these models.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression of periodic reports of anxiety and depression while in trade.

| Periodic reports of anxiety or depression while in trade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Women | Men | |||||||

| Anxiety | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Harassment reported | 1.86 | 1.28 to 2.71 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.68 to 2.05 | 0.567 | 2.55 | 1.56 to 4.16 | <0.001 |

| HADS anxiety | 1.37 | 1.30 to 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 1.26 to 1.45 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 1.30 to 1.49 | <0.001 |

| Trade: welding | 0.95 | 0.67 to 1.36 | 0.797 | 0.88 | 0.53 to 1.46 | 0.617 | 1.00 | 0.61 to 1.63 | 0.988 |

| Gender: male | 1.55 | 1.07 to 2.23 | 0.020 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Harassment reported | 2.79 | 1.75 to 4.45 | <0.001 | 4.35 | 2.11 to 8.96 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 1.22 to 4.12 | 0.009 |

| HADS depression | 1.37 | 1.29 to 1.45 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 1.29 to 1.55 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 1.27 to 1.49 | <0.001 |

| Trade: welding | 1.43 | 0.95 to 2.15 | 0.086 | 1.65 | 0.95 to 2.85 | 0.074 | 1.30 | 0.74 to 2.29 | 0.364 |

| Gender: man | 1.06 | 0.71 to 1.58 | 0.786 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| N observations | 4027 | – | – | 1718 | – | – | 2309 | – | – |

| Participants | 822 | – | – | 377 | – | – | 445 | – | – |

| Periodic reports of anxiety or depression made worse by work (in those reporting symptoms) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Women | Men | |||||||

| Anxiety | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Harassment reported | 2.04 | 1.27 to 3.29 | 0.003 | 2.64 | 1.27 to 5.48 | 0.009 | 1.67 | 0.88 to 3.15 | 0.115 |

| HADS anxiety | 1.14 | 1.07 to 1.21 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.07 to 1.26 | 0.001 | 1.11 | 1.01 to 1.21 | 0.028 |

| Trade: welding | 0.69 | 0.44 to 1.08 | 0.104 | 0.69 | 0.36 to 1.32 | 0.258 | 0.68 | 0.36 to 1.27 | 0.226 |

| Gender: man | 2.01 | 1.25 to 3.23 | 0.004 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| N observations | 944 | – | – | 420 | – | – | 524 | – | – |

| Participants | 397 | – | – | 184 | – | – | 213 | – | – |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Harassment reported | 2.31 | 1.30 to 4.10 | 0.004 | 4.97 | 2.04 to 12.09 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 0.73 to 3.19 | 0.259 |

| HADS depression | 1.09 | 1.01 to 1.17 | 0.023 | 1.09 | 0.98 to 1.22 | 0.120 | 1.09 | 0.99 to 1.19 | 0.077 |

| Trade: welding | 0.97 | 0.58 to 1.64 | 0.920 | 1.21 | 0.59 to 2.48 | 0.597 | 0.85 | 0.41 to 1.75 | 0.652 |

| Gender: male | 1.45 | 0.83 to 2.55 | 0.194 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| N observations | 723 | – | – | 312 | – | – | 411 | – | – |

| Participants | 324 | – | – | 143 | – | – | 181 | – | – |

The analyses in Table 3 were then repeated for the Alberta subsample with adjustment for mental ill-health prior to joining their trade, taken from the administrative health database. Among the 1,252 matched, 16.6% (208/1,252) had an anxiety-related condition before entering the trade, and 13.3% (167/1252) had a depressive condition (Table 2supplementary materials 4). No relation was found between previous mental ill-health and the likelihood of reporting anxiety or depression, or such a condition made worse by work. (Table 3, supplementary materials 4).

Sexual harassment

An additional analysis considered whether the type of harassment (sexual or other) was associated with differences in reports of periodic anxiety or depression and their attribution to work. For women differences in odds ratios between sexual or other harassment were small but much larger increases were found, for both anxiety and depression, for the small numbers of men reporting sexual harassment (Table 4, upper panel, supplementary materials 4) although this increase among men reporting sexual harassment was not reflected in their attribution to work (Table 4 lower panel, supplementary materials 4).

Table 4.

Relationship of harassment to physician-diagnosed depression and anxiety disorder since joining the trade (logistic regression).

| All | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety-related disorder | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Reported harassment | 1.27 | 0.97 to 1.67 | 0.082 | 1.13 | 0.74 to 1.75 | 0.570 | 1.38 | 0.97 to 1.96 | 0.070 |

| Anxiety condition before entered trade | 2.13 | 1.49 to 3.05 | <0.001 | 3.21 | 1.87 to 5.50 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 0.90 to 2.42 | 0.124 |

| Gender: female | 1.42 | 1.07 to 1.87 | 0.014 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Depression disorder | |||||||||

| Reported harassment | 2.09 | 1.55 to 2.81 | <0.001 | 2.00 | 1.26 to 3.18 | 0.003 | 2.14 | 1.46 to 3.16 | <0.001 |

| Depressive condition before entered trade | 2.36 | 1.59 to 3.51 | <0.001 | 2.76 | 1.61 to 4.72 | <0.001 | 1.95 | 1.07 to 3.55 | 0.029 |

| Gender: female | 1.23 | 0.90 to 1.66 | 0.189 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| N | 946 | 357 | 589 | ||||||

Harassment and physician records of mood disorders since joining the trade

The final table (Table 4) reports on the relationship between reported harassment and diagnoses recorded in the administrative health database. The outcome variables were diagnoses since joining the trade. Among 946/1,252 who had completed the harassment questions, 47.6% had been recorded by a physician as having an anxiety-related condition since joining their trade, and 29.1% had a depressive condition (Table 5 in supplementary materials 4). From Table 4, reported harassment was related to physician-diagnosed depressive disorders in both men and women but the relationship to physician-diagnosed anxiety disorders was much weaker.

Discussion

This report had three objectives. The first was to describe and compare the reported experiences of workplace harassment in women and men, closely matched on type of work, in trades traditionally entered by men. It found substantial reports of harassment in both genders, particularly during apprenticeship training. Levels were markedly higher in women, with harassment by coworkers, and behavior with a sexual component being particularly in evidence. The second objective was to use the data collected prospectively to contribute to the discussion of the effects of harassment on mental ill-health. Although missing some data that would have helped interpretation, the observed relationship between post-hoc reporting of harassment and the periodic reports, collected prospectively, of anxiety and depression made worse by work, cannot easily be attributed solely to bias or unmeasured confounding. Third, for those linked to the Alberta administrative health database, the analysis assessed the contribution of harassment to physician-recorded mental ill-health, so removing the element of health self-report. The results support the contribution of reported harassment, particularly to depression, in both women and men.

The prevalence rates reported here, 60% for women and 32% for men, appear high but reflect the length of the reporting period: the median time from the start of apprenticeship to the final questionnaire was 10.7 years for those still in their trade. Prevalence rates for workplace harassment are less clearly determined than those for bullying but recent data suggest that women and younger workers may be particularly at risk. In Hungary, the 12-month prevalence of offensive behavior at work was 53% in women and 45% in men, with rates over 60%, for both men and women aged 18–29 years (Szusecki et al. 2023). These figures are close to the reported 12-month prevalence of 60% for workplace violence in workers aged less than 25 years in the United States with higher rates (69%) in women (Rauscher et al. 2023). Riddle et al. (2023) concluded that some 50% of women in the United States experience workplace sexual violence with increased risk in male-dominated occupations. The rates of harassment reported here for the WHAT-ME cohort are considerably higher than the 12-month predicted probability of harassment estimated for workers across Canada, which found 18% for women and 14% for men (Hango and Moyser 2018) but these cannot be compared directly as the reporting periods were so different. The ratio of rates for women and men (1.9 here, 1.3 for all Canadian workers) is, however, consistent with a higher than-average excess risk of harassment for women in these traditionally male trades.

The strengths of the study include the recruitment and retention of a large cohort of women and men going through the same apprenticeship training in the welding or electrical trades and, largely, working in the same trades post-apprenticeship. A further strength is the repeated prospective collection of symptoms of anxiety and depression and reports of the role of work in making those symptoms worse. The link to administrative health data is an additional strength.

There are also limitations, both for the study overall and for its ability to answer the questions central to this analysis. First, as discussed elsewhere (Cherry et al. 2018), the response to the invitation to take part in the study was low (5%–15%) and those taking part may differ importantly from the whole cohort starting an apprenticeship since 2005. Recruitment to, and retention in, a prospective study, such as the one reported here depends very largely on the identification of participants with the goals of the study. Here, at recruitment, the aim was to identify the effects of work in the welding and electrical trades on physical health and the outcome of pregnancy. There was no focus on harassment at the time of recruitment (and indeed this was added in the final contact to reflect concerns raised by a steering group of women welders). While it is uncertain whether those who volunteered for the cohort will have differed from others in the trades in their experience of harassment, this would not be a systematic effect reflecting recruitment strategies. Second, although a 75% response rate to the final questionnaire is high for a follow-up study covering several years (Graaf et al. 2013; Nguyen et al. 2023), inclusion in the central analyses reported here was limited to those 948 completing the HADS scale (50% of those recruited). Similarly, information on ethnicity and gender identification was collected only in the long wrap-up and small numbers limited discussion of the outcomes of harassment in these subgroups. Moreover, the attribution of participants to male and female sub-cohorts, derived from apprenticeship records, did not allow consideration of a gender spectrum. A further limitation is the absence of data on when the harassment occurred: we could not link harassment events to a specific report of anxiety or depression made worse by work or to a date of physician diagnosis, nor can we estimate 12-month prevalence rates to compare with other studies. Data on mental health before the study were limited to administrative health reports in the Alberta cohort. Although the use of physician records is a strength, there are limitations to these data. Physicians record billing codes that correspond to their clinical impression and it cannot be assumed they carried out a full mental health assessment. The record only indicates that the worker’s mood was sufficiently disordered to trigger a billing code from the physician. Further, the physician database would not include mental health assessments by a psychologist or counselor. An additional limitation was the absence of data on other psychosocial aspects on work (such as the degree of control exercised by the worker over how they carried out work tasks. which may have influenced mental health directly or mitigated the ill-effects of work stressors (Svane-Petersen et al. 2020)). There may also have been uncontrolled confounding from demographic factors such as marital status or physical ill-health on which only limited data were collected.

The inherent difficulty in studies of the effects of harassment on mental health lies in the measurement of harassment. While it may be possible to get independent or objective measures of mental health (as here), use of outside perspectives (Cowie et al. 2002; Gullander et al. 2014) to record harassment has important limitations, particularly perhaps for sexual harassment and other behaviors not in the public view. In the present study, involving hundreds of different workplaces, measurement other than self-report was not feasible. Self-report is a strength in that the person experiencing workplace events as harassing is presumptively the best source of information about the event (with external reality checks, if available), but reliance on self-report has particular difficulties for assessing the causal link (if any) between harassment and later mental ill-health. Both experience and recollection of harassment may reflect current mental health. Someone who is anxious or depressed for reasons unconnected to work may find workplace frictions to be harassing to a degree they would not have experienced without the external stressors. Similarly, recollection of workplace events may be colored by current mental state, with those now anxious or depressed being more likely to interpret past frictions in a negative light. Further, a report of harassment may reflect dissatisfactions about working conditions more generally, rather than specific harassing behaviors. The design of the present study counters most of these potential biases. The collection of self-report data on harassment only at the end of the study avoided biases that would have arisen from the simultaneous recording of exposure and effect. The possibility of a long-standing susceptibility to mental ill-health, affecting both workplace anxiety/depression and perception of harassment, has been addressed by adjustment for HADS anxiety and depression scores. It remains possible that a negative relationship to work may have influenced both the prospective reporting (from 2013) of anxiety or depression as work related and the retrospective report of harassment (from 2016, after completion of the last prospective report). A simplified analysis (supplementary materials 5) suggests that it would have needed 38% of false positives (106/278 reports of harassment that did not occur) among those who had reported either anxiety or depression made worse by work for such a bias to negate these findings.

The analysis reported here suggests that events at work (presumptively including harassment) can worsen mental health, perhaps only transiently, but resulting in physician diagnoses of depressive conditions. Literature reviews of interventions to manage and reduce uncivil behavior and sexual harassment at the workplace (Tricco et al. 2018; Diez-Canseco et al. 2022) have little to say about approaches to organizational change but training interventions to influence knowledge and perceptions at the individual level are unlikely to change behavior if organizations continue to condone workplace harassment (Bowling and Beehr 2006). In Ibadan, Nigeria, Fawole et al. (2005) succeeded in reducing violence against women apprentices by interventions with employers and the community. Legislation against harassment (Government of Canada 2020; Government of Alberta Occupational Health and Safety 2023), following adoption of the International Labor Organization convention (2019), may help to enforce change in egregious cases, but pressure from employer organizations and groups such as Supporting Women in Trades (2023) [switcanada.caf-fca.org] in Canada may, over time, bring more lasting change. Turner et al. (2021) and Curtis et al (2022) have approached the steps that would be needed to change the culture of the work environment, based on their studies of women in the construction industry Their conclusions emphasize the need for strong leadership and a safe working environment in which women are not fearful to report unsafe working conditions, with Curtis et al. (2022) advocating for a mentor from outside the immediate worksite to provide construction apprentices with support. Access to groups at risk of harassment is not always easy and this study was particularly fortunate to have support from the apprenticeship boards of every Canadian province and territory in identifying and approaching women in the trades. The documentation of harassment and its relation to depression in those in their early years in the welding and electrical trades underlines the ongoing need for cultural change as women enter occupations historically the preserve of men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Laura Rodgers played a major role in contacting the participants over the several years of follow-up and in obtaining participation in the “wrap-up questionnaire.”

Contributor Information

Jean-Michel Galarneau, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alberta, 8303-112st, Edmonton, T6G 2T4, Canada; Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, T2N 1N4, Canada.

Quentin Durand-Moreau, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alberta, 8303-112st, Edmonton, T6G 2T4, Canada.

Nicola Cherry, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alberta, 8303-112st, Edmonton, T6G 2T4, Canada.

Author contributions

NC devised the study and lead the research team. J-MG created the data bases used in the analysis. QD-M was integral to the conception and coding of the details of reported harassment. All contributed to the analysis and writing of the report.

Funding

This work was funded by WorkSafe BC, the Government of Alberta (OHS Futures program), and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FRN 130235).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval

The project was reviewed by the Health Ethics Review Board of the University of Alberta (Pro00017851). All participants gave written informed consent. The work was carried out by observing the standards of the Helsinki Declaration

References

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug T, Neckelmann D.. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002:52(2):69–77. 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling NA, Beehr TA.. Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: a theoretical model and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2006:91(5):998–1012. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D, Wulff E, Bamberry L, Krivokapic-Skoko B, Jenkins S.. Negotiating gender in the male-dominated skilled trades: a systematic literature review. Constr Manag Econ. 2020; 38(10):894–916. 10.1080/01446193.2020.1762906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry N, Arrandale V, Beach J, Galarneau JF, Mannette A, Rodgers L.. Health and work in women and men in the welding and electrical trades: how do they differ? Ann Work Expo Health. 2018:62(4):393–403. 10.1093/annweh/wxy007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry N, Beach J, Galarneau JM.. Ergonomic demands and fetal loss in women in welding and electrical trades: a Canadian cohort study. Am J Ind Med. 2022:65(5):371–381. 10.1002/ajim.23336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry N, Galarneau JM.. Occupational dermatitis in welding: does nickel exposure account for higher rates in women? Analysis of a Canadian cohort. Ann Work Expo Health. 2021:65(2):183–195. 10.1093/annweh/wxaa049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie H, Naylor P, Rivers I, Smith P, Pereira B.. Measuring workplace bullying. Aggress Violent Behav. 2002:7:33–51. 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00034-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis HM, Meischke HW, Simcox NJ, Laslett S, Monsey LM, Baker M, Seixas NS.. Working safely in the trades as women: a qualitative exploration and call for women-supportive interventions. Front Public Health. 2022:9: 781572. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.781572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis HM, Meischke H, Stover B, Simcox NJ, Seixas NS.. Gendered safety and health risks in the construction trades. Ann Work Expo Health. 2018:62(4):404–415. 10.1093/annweh/wxy006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Canseco F, Toyama M, Hidalgo-Padilla L, Bird VJ.. Systematic review of policies and interventions to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace in order to prevent depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022:19(20):13278. 10.3390/ijerph192013278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen S. Harassment and bullying at work: a review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggress Violent Behav. 2000:5(4):379–401. 10.1016/s1359-1789(98)00043-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fawole OI, Ajuwon AJ, Osungbade KO.. Evaluation of interventions to prevent gender-based violence among young female apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Educ. 2005:105(3):186–203. 10.1108/09654280510595254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M.. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998:158(4):352–358. 10.1001/archinte.158.4.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau JM, Beach J, Cherry N.. Urinary metals as a marker of exposure in men and women in the welding and electrical trades: a Canadian cohort study. Ann Work Expo Health. 2022:66(9):1111–1121. 10.1093/annweh/wxac005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta Occupational Health and Safety. 2023. Workplace harassment and violence [accessed 2023 Dec 4]. https://www.alberta.ca/workplace-harassment-violence.aspx.

- Government of Canada. 2020. Requirements for employers to prevent harassment and violence in federally regulated workplaces. [accessed 2023 Oct 5]. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/workplace-health-safety/harassment-violence-prevention.html#.

- Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, Tuithof M, ten Have M.. Sociodemographic and psychiatric predictors of attrition in a prospective psychiatric epidemiological study among the general population. Result of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Compr Psychiatry. 2013:54(8):1131–1139. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullander M, Hogh A, Hansen AM, Persson R, Rugulies R, Kolstad HA, Thomsen JF, Willert MV, Grynderup M, Mors Oet al. Exposure to workplace bullying and risk of depression. J Occup Environ Med. 2014:56(12):1258–1265. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hango D, Moyser M.. 2018. Harassment in Canadian workplaces [accessed 2023 Dec 4]. statcan.gc.ca.

- International Labor Organization. 2019. C190—Violence and Harassment Convention [accessed 2023 June 21]. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C190.

- Jahnke SA, Haddock CK, Jitnarin N, Kaipust CM, Hollerbach BS, Poston WSC.. The prevalence and health impacts of frequent work discrimination and harassment among women firefighters in the US fire service. Biomed Res Int. 2019:2019:6740207. 10.1155/2019/6740207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Thomas AJ, Kerr P, Stewart AC, Wilkinson AL, Nguyen L, Altermatt A, Young K, Heath K, Bowring Aet al. Recruiting and retaining community-based participants in a COVID-19 longitudinal cohort and social networks study: lessons from Victoria, Australia. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023:23(1):54. 10.1186/s12874-023-01874-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MB, Matthiesen SB, Einarsen S.. The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying a meta-analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010:83(4):955–979. 10.1348/096317909x481256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher K, Casteel C, Davis J, Myers D, Peek-Asa C.. Prevalence of workplace violence against young workers in the United States. Am J Ind Med. 2023:66(6):462–471. 10.1002/ajim.23479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle K, Heaton K.. Antecedents to sexual harassment of women in selected male-dominated occupations: a systematic review. Workplace Health Saf. 2023:71(8). 10.1177/21650799231157085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudkjoebing LA, Bungum AB, Flachs EM, Eller NH, Borritz M, Aust B, Rugulies R, Rod NH, Biering K, Bonde JP.. Work-related exposure to violence or threats and risk of mental disorders and symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020:46(4):339–349. 10.5271/sjweh.3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2021. Number of apprenticeship program registrations [accessed 2023 Dec 4]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710002301.

- Statistics Canada. 2023. Statistics Canada Table: 98-10-0594-01 [accessed 2023 Dec]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810059401.

- Street AE, Gradus JL, Stafford J, Kelly K.. Gender differences in experiences of sexual harassment: data from a male-dominated environment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007:75(3):464–474. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supporting Women in the Trades. 2023. https://switcanada.caf-fca.org/ [accessed 5 Dec 2023].

- Svane-Petersen AC, Holm A, Burr H, Framke E, Melchior M, Rod NH, Sivertsen B, Stansfeld S, Sørensen JK, Virtanen Met al. Psychosocial working conditions and depressive disorder: disentangling effects of job control from socioeconomic status using a life-course approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020:55(2):217–228. 10.1007/s00127-019-01769-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szusecki T, Konkolÿ Thege B, Stauder A.. The prevalence and mental health correlates of exposure to offensive behaviours at work in Hungary: results of a national representative survey. BMC Public Health. 2023:23(1):78. 10.1186/s12889-022-14920-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Rios P, Zarin W, Cardoso R, Diaz S, Nincic V, Mascarenhas A, Jassemi S, Straus SE.. Prevention and management of unprofessional behaviour among adults in the workplace: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2018:13(7):e0201187. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Holdsworth S, Scott-Young C, Sandri K.. Resilience in a hostile workplace: the experience of women onsite in construction. Construct Manage Econ. 2021:39(10):839–852. 10.1080/01446193.2021.1981958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.