INTRODUCTION

Sleep is a natural biological state for reducing wakefulness, metabolism, and motor activity characterized by a reversible state and lack of responsiveness to some stimuli 1,2 . According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the phenomenon can be classified into two stages: non-rapid eye movement (NREM – N1, N2, and N3) sleep stages and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (R) stage 3 .

Sleep has also been associated with functional brain connectivity and is required for processing information, energy conservation, and restoration 4 . Sleep deprivation occurs when an individual does not sleep well or even insufficient quantity or low quality of sleep, which leads to a decreasing performance and subsequent deterioration in general health 5 . This condition can impair several behavioral and biological activities, affecting cognition and mood, increasing fatigue, and decreasing vigor. This picture impairs speed, decision-making, and accuracy of motor tasks 6 .

Although some environmental factors can interfere with the duration as well as the quality of sleep, it is also genetically controlled 7 . In particular, some studies have demonstrated that sleep deficiency leads to the injury to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in mammalian cells, leading to cellular injury 8-10 . This is consistent with the idea that sleep loss could induce genotoxicity 11 . As a result, this systematic review was motivated to answer the following question: Can sleep deprivation induce genetic damage in mammalian cells?

METHODS

Search strategy

In this research, we evaluated genetic damage in mammalian cells induced by sleep deficiency. This systematic review was performed according to the methodology described in the PRISMA guidelines statement 12 . For this purpose, a search was performed on the following scientific databases: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science, and all studies published in the past 10 years (2013–2023) that investigated the relationship between genetic damage and sleep loss were searched. All articles using a combination of the following keywords were selected: "sleep deprivation," "sleep loss," "paradoxical sleep deprivation," "genotoxicity," "genetic damage," "DNA damage," "comet assay," "single-cell gel electrophoresis," "mutation," "sister chromatid exchange," and "micronucleus assay" to refine the search strategy. Boolean operators were used (AND and OR) to combine the descriptors through different combinations as described elsewhere 13 .

Data extraction

The following data were presented using a particular data collection form: year of study, study design, origin, number of individuals, genotoxicity assay, species used, methodological parameters, negative and positive control groups, blind analysis and statistics, main results, and conclusion.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The quality assessment of the selected articles was based on previous studies published elsewhere 13 . The following information from the quality instrument was used: (1) study design, (2) identification and treatment of confounding factors, (3) blind analysis, and (4) data analysis. The criteria used to evaluate the study design were the number of participants per group, statistical analysis, and blind analysis. The confounding factors considered were cytotoxicity, number of repetitions, and positive and negative controls. After that, strong, moderate, and weak classifications were used as follows: the study was considered strong when it showed dominance on all items, except one; if it was on two items, it was considered moderate; and if the study did not control three or more items, it was considered weak.

RESULTS

Study selection

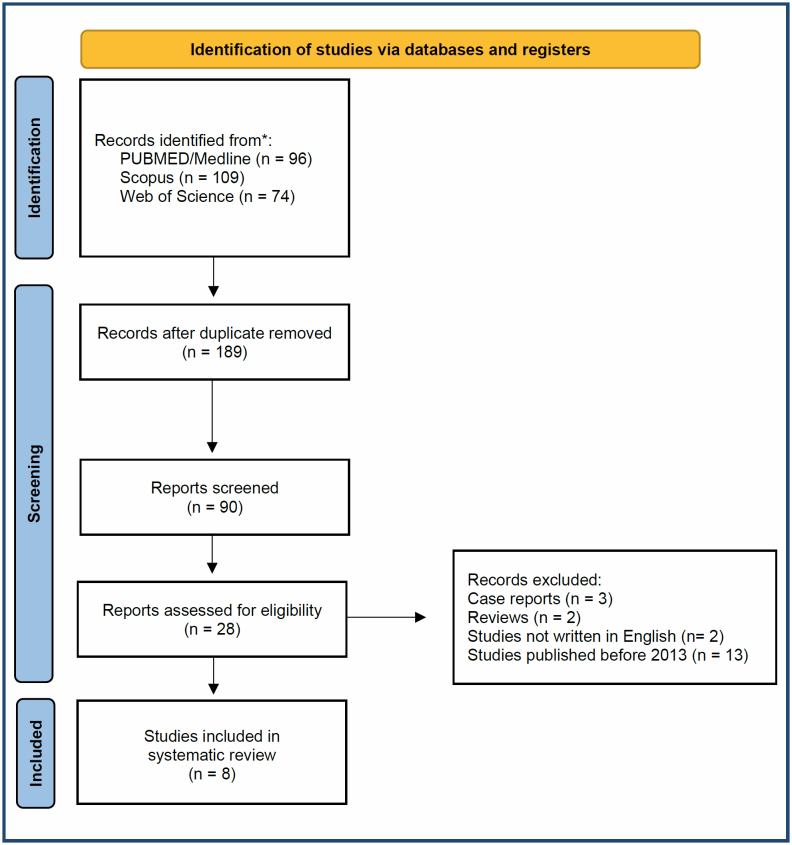

Initially, the study was able to identify 279 papers, of which 189 publications that were duplicates were excluded from the analysis. After screening all the articles, 161 studies that were not relevant were removed. In addition, reviews, case reports, editorials, papers not written in English, or letters to the editor were not considered. Finally, full texts of the remaining eight studies were sought and thoroughly read by two authors (DVS and DAR). The search strategy is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

Variables related to sleep deprivation and genotoxicity (confounders)

All variables evaluated in the studies are demonstrated in Table 1. The studies evaluated DNA damage by different methodologies. Alkaline single-cell gel (comet) assay was performed in three studies 8-10 . TUNEL assay was applied by Everson et al. 11 , counting cells into slides. Plasma or urine levels of 8-OHdG were evaluated by Everson et al. 11 , Valvassori et al. 12 , and Zou et al. 14 . Zhang et al. 13 performed FISH using telomere length as a numerical parameter of genotoxicity.

Table 1. Variables analyzed in the studies in chronological order.

| Author | Target organs | n | Negative control | Positive control | Assay | Number of cells evaluated | Cytotoxicity | Evaluated parameters | Blind analysis | Proper statistics description | Experimental design associated with other conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al. 10 | Peripheral blood | 24 volunteers 9 Males 15 Females 20.08±2.42 years of age |

Yes | No | Alkaline comet | 100 comets | No | DNA damage % | No | Yes | – |

| Everson et al. 11 | Liver Lung Heart Jejunum Spleen |

Control rats (n=7) Sleep deprivation (n=7–11) Recovery (n=5–6) |

Yes | No | TUNEL 8-OHdG |

Four sections – |

Yes | Counting cells pg 8OHdG/μg DNA |

No | Yes | – |

| Kahan et al. 8 | Skin | 12 mice (n=4/group) |

Yes | Yes | Alkaline comet | 50 comets | No | Tail intensity and tail moment | Yes | Yes | Aging |

| Moreno-Villanueva et al. 15 | Peripheral blood | 16 volunteers 8 Males 7 Females 36.4 ± 7.1 years of age |

Yes | Yes | FADU | – | Yes | DNA intensity | No | Yes | Radiation ex vivo |

| Tenorio et al. 9 | Peripheral blood Heart Kidney Liver Brain |

60 rats (n=25/group) |

Yes | Yes | Alkaline comet | 50 comets | No | Tail intensity | Yes | Yes | Obesity and aging |

| Valvassori et al. 12 | Brain | 40 mice (n=10/group) |

Yes | No | 8-OHdG | – | No | Plasma concentration | No | Yes | Lithium |

| Zhang et al. 13 | Lymphocytes Bone marrow Testis |

96 volunteers 28 mice (n=7/group) |

Yes | Yes | FISH | – | No | Telomere length | No | Yes | Folic acid diet |

| Zou et al. 14 | Urine samples | 16 volunteers | Yes | No | 8-OHdG | – | No | Plasma concentration | No | Yes | – |

SD: sleep deprivation; FADU: fluorometric analysis of DNA unwinding; FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization; SCE: sister-chromatid exchange; Dash (–): not applicable.

Main results

In the study conducted by Tenorio et al. 9 , the genotoxic effect was seen in the peripheral blood, liver, heart, and brain cells of obese old rats submitted to sleep deprivation.

Regarding oxidative DNA damage, 8-OHdG expression was increased in the liver, jejunum, and lung of rats exposed to total sleep deprivation 11 . Similarly, brain cells increased 8-OHdG in mice exposed to paradoxical sleep deprivation 12 . In humans, the same result was observed in urine samples 14 .

The study conducted by Cheung et al. 10 showed an increase in DNA strand breaks in peripheral blood cells of humans after sleep deprivation. In the study conducted by Zhang et al. 13 , sleep deprivation was associated with telomere shortening in the bone marrow and testis cells of mice and in the peripheral blood cells of humans. Conversely, the studies conducted by Kahan et al. 8 and Moreno-Villanueva et al. 15 did not show positive genotoxicity in the blood cells of sleep-deprived humans.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The quality assessment of manuscripts is shown in Table 2. After reviewing all studies, five papers were classified as strong 8,9,14,15 . In addition, two studies were categorized as moderate at the final rating, because they did not control two relevant variables 11,13 . Finally, two studies were categorized as weak 10,12 .

Table 2. Quality assessment and final rating of the studies in chronological order.

| Author | Number of confounders | Details | Final rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al. 10 | 3 | Positive control; cytotoxicity; and blind analysis | Weak |

| Everson et al. 11 | 2 | Positive control and blind analysis | Moderate |

| Kahan et al. 8 | 1 | Cytotoxicity | Strong |

| Moreno-Villanueva et al. 15 | 1 | Blind analysis | Strong |

| Tenorio et al. 9 | 1 | Cytotoxicity | Strong |

| Valvassori et al. 12 | 3 | Positive control; cytotoxicity; and blind analysis | Weak |

| Zhang et al. 13 | 2 | Cytotoxicity and blind analysis | Moderate |

| Zou et al. 14 | 1 | Cytotoxicity | Strong |

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate if, and to what extent, sleep deprivation induces genetic injuries in mammalian cells. For this purpose, a total of eight studies were selected in this setting. The single-cell (comet) gel assay is an excellent, reliable method for evaluating DNA strand breakage, including DNA adducts, single- and double-strand breaks, and deficient repair sites. This technique is a simple method that allows the proper investigation of DNA strand breaks that can originate from many contexts and paradigms 16 . In this review, the comet assay was the preferred method for evaluating genetic damage by sleep deprivation as the majority of papers (three studies) have demonstrated positive genotoxicity induced by sleep deprivation in multiple organs of rodents by comet assay. In fact, it has been assumed that DNA damage is driven by sleep 17 . This is because sleep induces nuclear stability, i.e., sleep regulates the homeostatic balance between genetic damage and DNA repair system 17 . Nevertheless, it remains obscure how DNA damage is induced by sleep, and the role of the DNA repair system in this scenario. Anyway, these findings suggest that genetic damage plays an important role as a biological regulator of sleep in mammalian cells 18 . In the past decades, the single-cell gel comet assay Expert Group has established some guidelines for conducting the methodology in a proper way 19 . First, it is mandatory to evaluate at least 25 comets per slide. Additionally, the percentage of the tail (known as tail intensity or % DNA in tail) is the best option when analyzing comet assay associated with an image analysis system.

Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation can cause DNA damage using other assays, such as FADU and TUNEL tests. Of particular importance, the studies conducted by Everson et al. 11 and Valvassori et al. 12 have demonstrated that sleep deprivation was able to induce oxidative DNA damage, as depicted by 8-OHdG expression. It is important to highlight that 8-OHdG is synthesized from the reaction of the hydroxyl radical (HO•) and guanine, which is the most common way for DNA damage. As a result, a pro-mutagenic agent has been formed when the DNA damage is not repaired 20 .

One important reason that can be categorized as a confounding factor in genotoxicity studies is the adoption of negative and positive controls in the experimental design. For any in vivo genotoxicity assay, it is mandatory to demonstrate the specificity as well as the sensitivity of the methodology. Most of the studies included in this review performed tests with positive and negative controls. Nevertheless, the studies conducted by Cheung et al. 10 and Everson et al. 11 did not provide concurrent positive control in the experimental design. Another question refers to cytotoxicity. High cytotoxicity is the main confounding factor in genotoxic investigations 21 . Underestimating cytotoxicity may lead to incorrect or misleading data interpretation. In this sense, it is necessary to have more information regarding the association between cytotoxic and genotoxic effects to achieve more sensitive results. Ten studies included in this review did not perform complementary analysis for cytotoxicity.

Considering various parameters used for evaluating the studies included in the review, there is some tendency in the literature showing genotoxic effects that are induced by sleep deprivation. Anyway, such information will bring new insights for a better understanding of the consequences induced by sleep deficiency on genetic material.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors acknowledge research grants received from CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico, Grant Number #001) for productivity fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rasch B, Born J. About sleep's role in memory. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(2):681–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams RM. Sleep deprivation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(3):493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bah TM, Goodman J, Iliff JJ. Sleep as a therapeutic target in the aging brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16(3):554–568. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00769-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long T, Li H, Shu Y, Li K, Xie W, Zeng Y, et al. Functional connectivity changes in the insular subregions of patients with obstructive sleep apnea after 6 months of continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Neural Plast. 2023;2023:5598047–5598047. doi: 10.1155/2023/5598047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruder K. A good night's sleep. Sleep loss can affect not only your quality of life, but your health as well. Diabetes Forecast. 2006;59(10):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groeger JA, Lo JC, Santhi N, Lazar AS, Dijk DJ. Contrasting effects of sleep restriction, total sleep deprivation, and sleep timing on positive and negative affect. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:911994–911994. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.911994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehgal A, Mignot E. Genetics of sleep and sleep disorders. Cell. 2011;146(2):194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahan V, Ribeiro DA, Egydio F, Barros LA, Tomimori J, Tufik S, et al. Is lack of sleep capable of inducing DNA damage in aged skin? Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(3):127–131. doi: 10.1159/000354915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenorio NM, Ribeiro DA, Alvarenga TA, Fracalossi AC, Carlin V, Hirotsu C, et al. The influence of sleep deprivation and obesity on DNA damage in female Zucker rats. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68(3):385–389. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(03)oa16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung V, Yuen VM, Wong GTC, Choi SW. The effect of sleep deprivation and disruption on DNA damage and health of doctors. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(4):434–440. doi: 10.1111/anae.14533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everson CA, Henchen CJ, Szabo A, Hogg N. Cell injury and repair resulting from sleep loss and sleep recovery in laboratory rats. Sleep. 2014;37(12):1929–1940. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valvassori SS, Resende WR, Dal-Pont G, Sangaletti-Pereira H, Gava FF, Peterle BR, et al. Lithium ameliorates sleep deprivation-induced mania-like behavior, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis alterations, oxidative stress and elevations of cytokine concentrations in the brain and serum of mice. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(4):246–258. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhao R, Hu X, Zhang B, Lv X, et al. Folic acid supplementation suppresses sleep deprivation-induced telomere dysfunction and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4569614–4569614. doi: 10.1155/2019/4569614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou Y, Ma X, Chen Q, Xu E, Yu J, Tang Y, et al. Nightshift work can induce oxidative DNA damage: a pilot study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):891–891. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15742-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno-Villanueva M, Scheven G, Feiveson A, Bürkle A, Wu H, Goel N. The degree of radiation-induced DNA strand breaks is altered by acute sleep deprivation and psychological stress and is associated with cognitive performance in humans. Sleep. 2018;41(7) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drummond GWB, Takeshita WM, Castro GM, Santos JN, Cury PR, Renno ACM, et al. Could fluoride be considered a genotoxic chemical agent in vivo? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Health Res. 2023:1–14. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2023.2194616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schibler U. PARP-1 drives slumber: a reciprocal relationship between sleep homeostasis and DNA damage repair. Mol Cell. 2021;81(24):4958–4959. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zada D, Bronshtein I, Lerer-Goldshtein T, Garini Y, Appelbaum L. Sleep increases chromosome dynamics to enable reduction of accumulating DNA damage in single neurons. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):895–895. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08806-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speit G, Kojima H, Burlinson B, Collins AR, Kasper P, Plappert-Helbig U, et al. Critical issues with the in vivo comet assay: a report of the comet assay working group in the 6th international workshop on genotoxicity testing (IWGT) Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2015;783:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graille M, Wild P, Sauvain JJ, Hemmendinger M, Guseva Canu I, Hopf NB. Urinary 8-OHdG as a biomarker for oxidative stress: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3743–3743. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malacarne IT, Takeshita WM, Viana MB, Renno ACM, Ribeiro DA. Is micronucleus assay a suitable method for biomonitoring children exposed to X-ray? a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Biol. 2023;99(10):1522–1530. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2023.2194405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]