Abstract

Apoptosis is a main feature of AIDS pathogenesis and is thought to play a role in the progressive decrease of CD4+ T lymphocytes in infected individuals. To determine whether apoptosis occurs in infected and/or in uninfected peripheral blood T lymphocytes, we have used a recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infectious clone expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Using flow cytometry, we have determined the incidence of apoptosis by either terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling or annexin-V assays in different cell subpopulations, i.e., in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells that were GFP positive or negative. After HIV-1 infection of purified peripheral blood lymphocytes, we observed that apoptosis occurred mostly in infected CD4+ peripheral blood lymphocytes. Remarkably, the presence of monocyte-derived macrophages in the culture increased dramatically the apoptosis of uninfected bystander T lymphocytes, while apoptosis in HIV-infected T lymphocytes was not changed. We therefore demonstrate that HIV-induced apoptosis results from at least two distinct mechanisms: (i) direct apoptosis in HIV-infected CD4+ T lymphocytes and (ii) indirect apoptosis in uninfected T cells mediated by antigen-presenting cells.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is characterized by the progressive depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes (15). The drop in the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes is preceded by early T-cell functional defects characterized in vivo by a loss of cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and in vitro by a failure of T cells to proliferate in response to T-cell receptor stimulation by recall antigens or mitogens (15, 29, 39, 51). Several hypotheses have been advanced to account for the loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes. They include (i) direct lysis of the cells by the virus infection (53, 55), (ii) syncytium formation (34, 52, 63), (iii) autoimmunity (17), (iv) cellular and humoral virus-specific immune responses (65), (v) superantigen-mediated deletion of specific T-cell subpopulations (22), and (vi) apoptosis (4). The potential role of apoptosis in CD4 depletion has been examined in several studies (31, 35, 58), and increased apoptosis in freshly isolated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in cultures grown with blood isolated from HIV-positive individuals has been reported (18, 19, 32, 38, 44, 48). Increased apoptosis in both CD4+ mature T lymphocytes and thymocytes after HIV infection in the hu-SCID mouse model has also been described (3, 11, 41, 42, 56).

Using protease inhibitors to block virus replication, recent studies have indicated that rapid turnover of circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes occurs in HIV-1-infected individuals (21, 60). These studies have highlighted a dynamic inverse correlation between plasma virus levels and CD4+ T-cell levels in patients (21, 60). While these observations suggested destruction of HIV-infected cells in vivo, no direct evidence was provided for this assumption, and the possibility remains that the HIV-mediated cell killing is indirect, i.e., that mostly uninfected cells are killed. In fact, apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander uninfected lymphocytes present in the vicinity of HIV-infected cells in the lymph nodes of HIV-infected humans and of SIV-infected monkeys (16). In lymph nodes, indirect apoptosis of uninfected T cells could result from CD4 cross-linking, secretion of apoptotic cytokines or viral proteins, or involvement of antigen-presenting cells (7–9, 33, 42, 45, 61, 64).

To determine whether HIV-induced apoptosis occurs via a direct or an indirect mechanism, we generated a recombinant HIV-1 genome encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Since GFP is expressed as an early viral product by this recombinant virus, we have used flow cytometry to discriminate between GFP-positive (infected) and GFP-negative (uninfected) peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) to determine the incidence of apoptosis, as measured by terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and annexin-V assays, in both cell subpopulations. We observed that after infection of purified PBLs by HIV-1 in vitro, cells undergoing apoptosis are almost exclusively GFP-positive infected CD4+ T lymphocytes. In contrast, after HIV infection of a mixed population containing both PBLs and monocyte-derived macrophages, cells undergoing apoptosis are essentially GFP-negative uninfected bystander T lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

CEMx174 is a CD4+ T-cell/B-cell hybrid line generated from the polyethylene glycol-mediated fusion of 721.174 and CEM.3 cells (47). Jurkat is a CD4+ T-cell line. Both CEMx174 and Jurkat cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Isolation and culture of PBLs and blood monocyte-derived macrophages.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from healthy donors as described previously (12). In short, Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden)-isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells were incubated for 1 h on 2% gelatin-coated plates. Adherent tissue culture-differentiated macrophages (TCDM), >94% CD14+ by flow cytometry analysis, were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) pooled AB human serum (Sigma, St Louis, Mo.) for 48 h before transfer to six-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells per well in a 3-ml total volume. Nonadherent cells, >98% which were PBLs as assessed by CD45+ (Simultest Leucogate; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) detection by flow cytometry analysis, were harvested after Ficoll-Hypaque isolation and adherence. PBLs were cultivated in RPMI with 10% FCS supplemented for the first 48 h with phytohemagglutinin A (PHA; 5 μg/ml; Sigma) before the addition of human recombinant interleukin-2 (hrIL-2; 20 IU/ml; Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). For coculture, PHA- and IL-2-activated PBLs were mixed with 10% TCDM and cultivated in RPMI with 10% (vol/vol) FCS supplemented with hrIL-2 as described above. Culture medium was replaced every 2 days.

Generation of 89.6 HIV-1 clones expressing both wild-type and bright mutated GFP.

To create the viruses designated HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T, we inserted the GFPwt, GFPRS, and GFPS65T genes amplified by PCR into the nef open reading frame of HIV-89.6 (13, 54). The XhoI (nucleotide [nt] 3353)-XhoI (nt 3866) fragment of 89.6-3′Eco was modified as follows. The first 110 nt of the nef gene were deleted, the ATG start codon of the nef gene was mutated (into ATA), and two restriction sites corresponding to EagI and XmaI were introduced into the nef gene by PCR with the following primers: 5′- ACC GAG CTC GAG CGG CCG ACC ATG CGA CCC GGG CAC TTG CCA CCT ATC TTA TAG CAAA-3′ and 5′-GAT GCA CTC GAG GGG ACC CGA CAG GCC CGA AGG-3′. This modified XhoI-XhoI fragment was cloned into the 89.6-3′Eco plasmid digested by XhoI. We refer to this construct as HIV-89.6-EagI/XmaI. A fragment containing the cDNA for GFP was obtained after digestion of pGFP (Clontech) with SmaI and EagI and was cloned into the EagI-XmaI sites of plasmid HIV-89.6-EagI/XmaI. We refer to this construct as HIV-GFPwt. Fragments containing cDNAs for brighter GFPs were obtained from plasmids pRSGFP-C1 and pS65T-C1 (Clontech) after digestion with AgeI and XmaI and cloned into plasmid HIV-89.6-EagI/XmaI digested by XmaI. We refer to these constructs as HIV-GFPRS and HIV-GFPS65T, respectively.

Generation of viral stocks.

The circular permutated infectious molecular clone of HIV-1, pILIC19 (gift from A. Rabson), was digested by EcoRI and religated on itself to eliminate the EcoRI (nt 5743; pILIC)-EcoRI (nt 400; pUC19) fragment. We refer to this construct as pILIC19ΔE. To generate vector pEV114, the ApaI (nt 2010)-EcoRI (nt 5743) fragment from pNL4-3 (1) was cloned into vector pILIC19ΔE digested by ApaI and EcoRI. Wild-type and mutant HIV-1 infectious DNAs were generated after ligation of a left hemigenome (EcoRI-digested pEV114) with the single-long terminal repeat (LTR)-containing right hemigenome constructs described above (EcoRI-digested HIV-89.6, HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, or HIV-GFPS65T). Ten micrograms of concatemerized proviral DNA was transfected into 107 Jurkat cells by the DEAE-dextran procedure (59). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, Jurkat cells were cocultivated with 107 CEMx174 cells to allow rapid and efficient recovery of progeny virus. Virus stocks were prepared from supernatants after filtration through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, quantified by measuring reverse transcriptase (RT) activity, and stored at −80°C.

Infections.

CEMx174 and Jurkat cells were cultivated in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS at a density of 106 cells/ml. TCDM, PHA-activated PBLs, or TCDM-PBL cocultures were cultivated in six-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells/well. The 3-ml final volume included RPMI supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) pooled AB human serum for the TCDM cultures or 10% FCS supplemented with hrIL-2 (20 IU/ml) for the PHA-activated PBLs. After 2 h of exposure to virus at 37°C, cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the unadsorbed inoculum and reincubated in fresh culture medium at 37°C. Culture supernatants were collected every 2 days and assayed for RT activity. Cell pellets were harvested and washed twice with PBS before fixation with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min. Fixed cells were used to perform flow cytometry analysis.

RNase protection analysis.

HIV-1-specific transcripts were detected by RNase protection analysis after lysis of cells in guanidine thiocyanate (20) (Lysate Ribonuclease Protection kit; U.S. Biochemicals). An HIV-1-specific 32P-labeled antisense riboprobe was synthesized in vitro by transcription of pGEM23 (30) with SP6 polymerase according to standard protocols (6). A glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-specific antisense probe (provided with the Lysate Ribonuclease Protection kit; U.S. Biochemicals) was synthesized by the same protocol and used in the same reaction with the HIV-1 probe. The HIV-1 antisense RNA probe protects two RNA fragments of 83 and 200 nt which correspond to the 5′ and 3′ LTRs, respectively (30).

Western blotting.

CEMx174 cells, uninfected or infected with either HIV-89.6 or each of the three HIV-GFP clones, were harvested at the peak of RT activity. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in 150 mM NaCl–10 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris (pH8)–10 mM NaN3–1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride–5 mM iodoacetamide–1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40. Protein concentrations in cell lysates were determined (Protein Assay; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Sample proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose (Hybond-ECL; Amersham). Membranes were blocked in PBS with 3% (wt/vol) dried milk and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. The binding of polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP, used at 1:2,000 (Clontech), was determined by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) used at 1:1,000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) and by chemiluminescence (ECL kit; Amersham). For detection of virion-associated proteins, HIV-1 lysates were prepared by ultracentrifugation of each virus stock and resuspension of pellets in Laemmli buffer at a concentration of 30,000 cpm of RT/μl. Lysates were heated at 95°C for 5 min and subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with a 1:2,000 dilution of purified human anti-HIV-1 IgG (National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reagent Program). A second antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was then used at 1:10,000 for enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham).

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS were labeled for either the TUNEL or annexin-V assay as described below and analyzed by flow cytometry with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). CD4 and CD8 detections were performed with PerCP-labeled anti-human CD4 and CD8 mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson). Specific fluorescence was assessed by comparison with cells stained with isotype controls (Becton Dickinson). The purity of the PBL population was confirmed by the detection of CD45+ antigen (Simultest Leucogate; Becton Dickinson). The specific fluorescence of GFP was excited at 488 nm. Data from 5 × 104 cells were collected, stored, and analyzed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

RT activity assay.

HIV-1 production was measured by determining RT activity in culture supernatants by using a microassay (2).

TUNEL assay.

After fixation with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, 5 × 106 cells per sample were washed three times with 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS. After being washed with terminal transferase buffer (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in a 50-μl final volume, cells were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in a 50-μl final volume containing 20 U of terminal transferase, 2.5 mM CoCl2, 5 μM 16-dUTP biotin, 5 μM dUTP (all from Boehringer GmbH), and 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. After being washed (0.3% [vol/vol] Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h, cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in phycoerythrin-labeled streptavidin (Boehringer GmbH) diluted 1:200 in PBS. After one wash in 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS, cells were resuspended in PBS and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Apoptosis was measured in both uninfected and infected PBLs isolated from the same donor, and values of the specific apoptosis in PBLs and in CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations were expressed as follows: (percentage of apoptosis in infected culture) − (percentage of apoptosis in uninfected culture).

Annexin-V assay.

Purified annexin-V (Biodesign International, Kennebunk, Maine) was biotinylated in vitro and purified according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotinylation Kit; Pierce). The modified protein was examined after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis by Western blotting using horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin diluted 1:2,000 in PBS and chemiluminescence (ECL kit; Amersham). This analysis showed the presence of a single 35-kDa band on the gel corresponding to the known molecular mass of annexin-V (data not shown). The annexin-V assay was performed as reported previously (27). After fixation in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, 5 × 106 cells were washed three times in PBS. After incubation in HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES–NaOH [pH 7.4], 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2) supplemented with 2.5 μg of biotinylated annexin-V per ml for 15 min at room temperature, cells were washed twice with PBS before incubation for 1 h in phycoerythrin-labeled streptavidin (Boehringer GmbH) diluted 1:200 in PBS at room temperature. To determine the integrity of the plasma membrane, 2 μl of a 50-μg/ml solution of propidium iodide was added to each sample in a 100-μl final volume. After one wash in PBS, cells were resuspended in 500 μl of PBS for flow cytometry analysis. Apoptosis was measured in both uninfected and infected PBLs isolated from the same donor, and specific apoptosis in PBLs and in CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations was expressed as follows: (percentage of apoptosis in infected culture) − (percentage of apoptosis in uninfected culture).

RESULTS

Construction of HIV-1 molecular clones expressing either wild-type or bright mutated GFP.

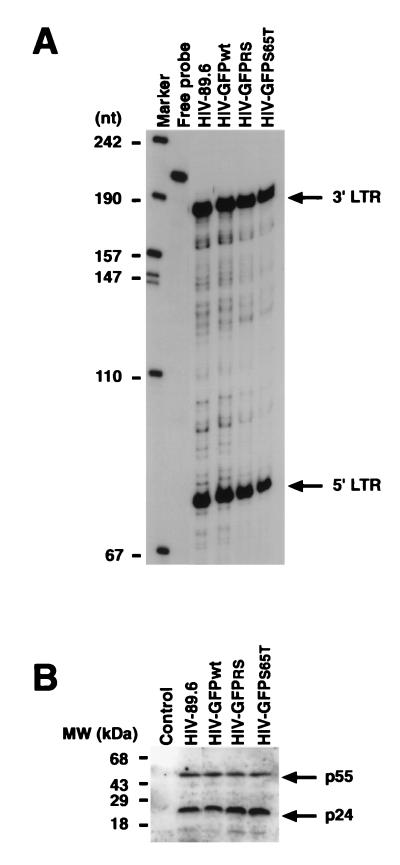

To distinguish between infected and uninfected cells, we introduced the GFP reporter gene into the 89.6 infectious molecular clone of HIV-1 (13). This virus presents dual tropism for both primary human monocytes/macrophages and PBLs and is representative of natural isolates encountered in patients. We cloned genes encoding distinct forms of GFP into a modified HIV-89.6 infectious molecular clone in which the first 110 nt of the nef open reading frame (nt 3757 to 3866), including ATG, had been deleted and replaced with two unique cloning sites XmaI and EagI (Fig. 1). Three different forms of GFP were used: the wild-type form and two mutated forms characterized by increased fluorescence and called GFPRS and GFPS65T (Clontech). The three resultant recombinant HIV clones are called HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T. The recombinant HIV genomes were ligated and transfected into CEMx174 cells, and virus stocks were harvested and quantified by RT activity measurement. Since the integrated fragment corresponding to GFP (780 nt) might interfere with the packaging of the HIV genome into particles, we used an RNase protection assay to determine whether all three virus genomes (HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T) were packaged with the same efficiency as the parental clone (HIV-89.6). Similar amounts of virus particles, based on RT activity content, were pelleted by centrifugation. Lysed pellets were used both in an RNase protection analysis using an antisense RNA probe corresponding to the U3-R region of HIV (Fig. 2A) and in a Western blot analysis using a antiserum specific for HIV proteins (Fig. 2B). This experiment showed similar packaging of the HIV genome by all four viruses (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis of the same virus lysates confirmed that similar amounts of virus particles were used (Fig. 2B).

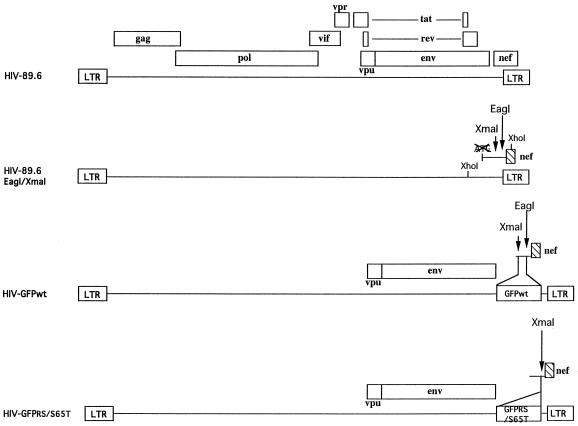

FIG. 1.

Construction of HIV-1 molecular clones expressing either wild-type or mutated GFP. The parental virus, HIV-89.6, is shown at the top, and the insertion of GFPwt, GFPRS, or GFPS65T into the nef open reading frame is illustrated below the sequence. HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T contain an inserted GFPwt, GFPRS, or GFPS65T gene, respectively, at the 3′ end of env. Open boxes indicate open reading frames of genes expressed in the virus construct.

FIG. 2.

Packaging of recombinant HIV-GFP genomes. (A) RNase protection analysis of HIV genomic RNA purified after ultracentrifugation of culture supernatants. Two protected fragments corresponding to the 3′ and 5′ LTRs are shown. (B) Western blot analysis of ultracentrifuged virion-associated proteins performed with an IgG fraction purified from HIV-infected individuals. The control lane shows results for the resuspended pellet obtained following ultracentrifugation of supernatant harvested from uninfected cells.

Replication of HIV-GFP clones in the CEMx174 cell line, in primary human PBLs, and in macrophages.

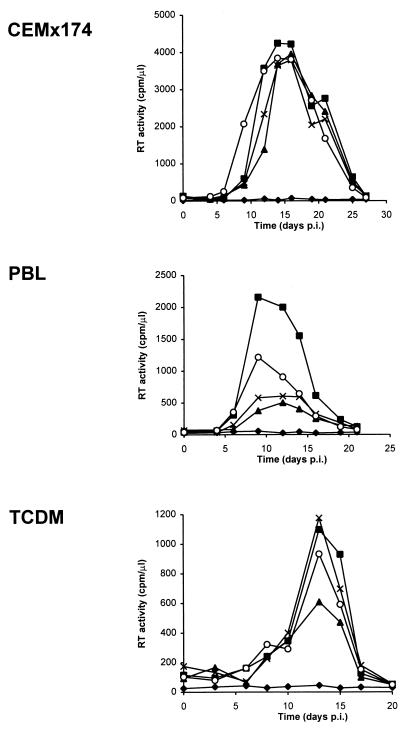

Next, we assessed the ability of HIV-89.6 and HIV-GFP viruses to infect CEMx174 cells, Jurkat T cells, human PBLs, and TCDM (Fig. 3). All four viruses replicated with the same kinetics in CEMx174 cells, demonstrating that the presence of the GFP gene within the viral genome did not impair viral growth in this cell line (Fig. 3). In contrast, the efficiencies of replication of the three HIV-GFP clones were diminished by a factor of 2 to 5 in primary PBLs in comparison to that of HIV-89.6 (Fig. 3). This decrease in replication efficiency is most likely secondary to the disruption of the nef gene and the resultant disruption of Nef, which, as previously reported, has a role in HIV-1 replication in primary PBLs (24). In TCDM, all four viruses replicated with similar kinetics (Fig. 3). As previously reported, these viruses did not replicate efficiently in Jurkat T cells (data not shown) (54).

FIG. 3.

Replication of HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T clones in CEMx174 cells, primary human PBLs, and TCDM. CEMx174 cells, PHA- and IL-2-activated PBLs, and TCDM were either left uninfected (⧫) or infected with HIV-89.6 (▪), HIV-GFPwt (▴), HIV-GFPRS (×), or HIV-GFPS65T (○) clones (5 × 105 cpm of RT/5 × 106 cells). RT activity was measured in culture supernatants. Results are representative of three independent experiments. p.i., postinfection.

GFP expression during infection with HIV-GFP.

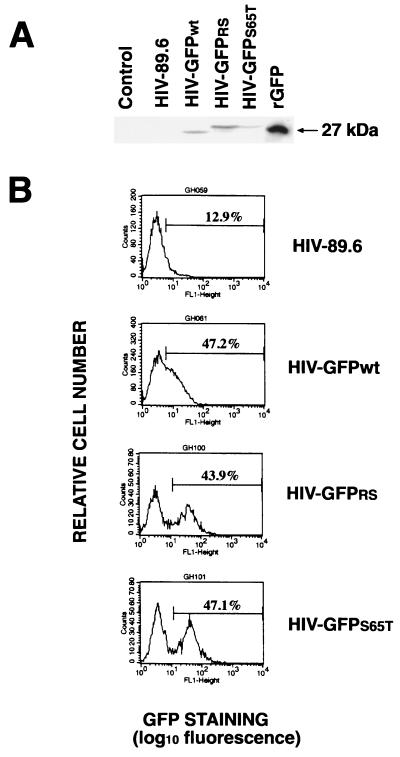

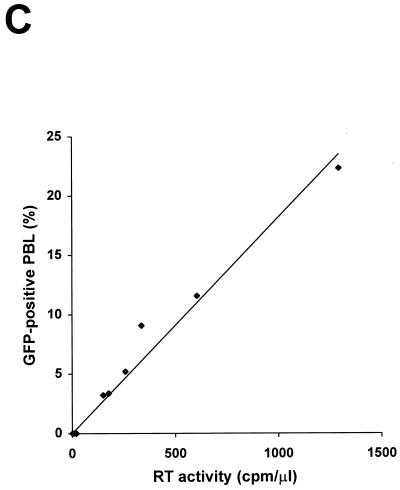

To examine the expression of GFP during infection with HIV-GFP viruses, we harvested CEMx174 cells infected with either HIV-89.6 or the three GFP-recombinant HIVs at the peak of RT activity. Cells were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Fig. 4A). No GFP protein could be detected following infection with HIV-89.6. Instead, infection with HIV-GFP viruses resulted in the appearance of a new band of 27 kDa reacting with the anti-GFP antibody. The size of the GFP expressed in cells infected with HIV-GFPwt was similar to that of the recombinant purified GFP (Fig. 4A). In contrast, two distinct immunoreactive bands of 27 and 30 kDa were observed in cells infected with HIV-GFPRS or HIV-GFPS65T, respectively (Fig. 4A). Flow cytometry analysis of CEMx174 cells, uninfected (data not shown) or infected with HIV-89.6, showed nonspecific autofluorescence (Fig. 4B). Cells infected with HIV-GFPwt showed a small shift in the fluorescence peak (Fig. 4B); however, discrimination between the two cell subpopulations, GFP negative and GFP positive, was not possible. In contrast, in cells infected with HIV expressing the brighter GFP variants, GFPRS and GFPS65T, two distinct subpopulations were easily detected on the basis of their fluorescence (Fig. 4B). The percentage of GFP-positive cells present in the PBL culture following infection with HIV-GFPS65T was linearly correlated to the level of RT activity in the culture supernatant (r2 = 0.98) (Fig. 4C). Therefore, cell fluorescence as a reflection of GFP expression allows the identification of infected cells in a heterogeneous population comprising both uninfected and infected cells.

FIG. 4.

Cells infected with HIV-GFP express GFP. (A) Detection by Western blot analysis of GFPs in CEMx174 cells infected with HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T clones but not with HIV-89.6. Recombinant GFP (500 ng; Clontech) was loaded as a positive control. Uninfected cells were loaded as a negative control (Control). (B) Flow cytometry analysis of CEMx174 cells uninfected (data not shown) or infected with HIV-89.6, HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T viruses. Cells were harvested at day 15 postinfection, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence values (in the defined gate) for HIV-89.6, HIV-GFPwt, HIV-GFPRS, and HIV-GFPS65T were 10.1, 15.9, 46.2, and 48.9, respectively. (C) Percentage of GFP-positive PBLs correlates linearly with the RT levels in the culture supernatants (r2 = 0.98).

Apoptosis occurs in both uninfected and HIV-infected cultures.

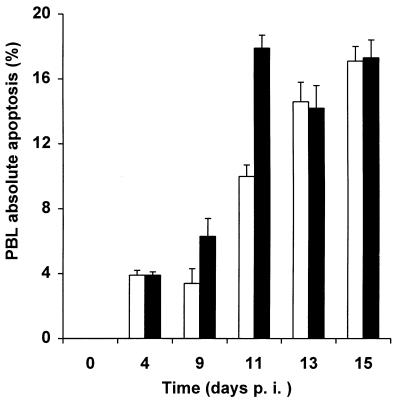

To detect apoptosis in human PBLs, we used two assays which examine two different markers of apoptosis. The TUNEL assay detects the presence of nicks in DNA, a late event in the apoptotic process, whereas the annexin-V assay detects the appearance of phosphatidyl serine at the cell surfaces of apoptotic cells and represents an earlier marker (36). We performed a time course analysis following infection of purified human PBLs with HIV-GFPS65T. Three different variables were monitored as a function of time: (i) RT activity in culture supernatants; (ii) apoptosis level, by the TUNEL or annexin-V assay; and (iii) HIV gene expression by GFP measurement. In three independent experiments, no apoptosis was detected at the time of PBL isolation (Fig. 5). Starting at day 4 following stimulation with PHA plus IL-2, we observed significant apoptosis even in uninfected PBLs, as previously reported (Fig. 5) (44). Interestingly, levels of absolute apoptosis were higher in infected PBLs than in uninfected PBLs usually at days 9 (P = 0.04; t test) and 11 (P = 0.001; t test) postinfection, demonstrating specific HIV-dependent apoptosis (Fig. 5). No difference in apoptosis between infected and uninfected populations was noted earlier (day 4) or later (days 13 and 15). Similar results were obtained with several other donors, whose cells displayed significant specific HIV-dependent apoptosis from days 9 to 17 postinfection (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Apoptosis occurs in both uninfected and HIV-infected human PBLs. Purified PBLs isolated and activated with PHA and IL-2 were either left uninfected (□) or infected by HIV-GFPS65T (▪). A total of 5 × 106 cells were harvested at each time point, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, and labeled by TUNEL assay to measure apoptosis. By single-color flow cytometry the levels of apoptotic cells were determined in parallel in both uninfected and infected PBLs. The averages ± the standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown. p.i., postinfection.

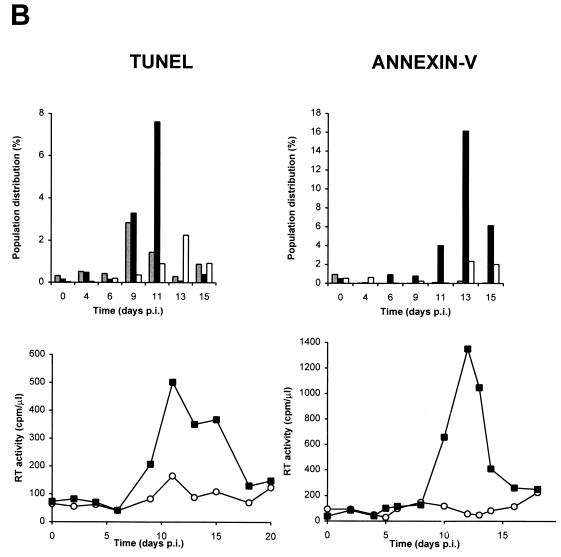

Apoptosis occurs predominantly in infected cells after HIV infection of purified human PBLs.

To determine whether HIV-specific apoptosis occurred in GFP-positive (productively infected) or GFP-negative (uninfected or unproductively infected) cells, we combined the measurement of GFP fluorescence and TUNEL or annexin-V assays of PBLs at each time point following infection (Fig. 6). Both GFP-negative and GFP-positive PBLs underwent specific apoptosis, but specific apoptosis occurred at a significantly higher rate in GFP-positive than in GFP-negative PBLs (Fig. 6). To measure the rate of apoptosis specifically dependent on HIV infection, we compared the rates of apoptosis in infected and uninfected cultures of cells from the same donor. For example, the fractions of cells located in the upper right quadrant (UR) or upper left quadrant (UL) were compared for infected (URi or ULi) and uninfected (URu or ULu) cultures. HIV-specific apoptosis is defined as the difference between these two values. For example, ULi−ULu represents the percentage of cells undergoing HIV-specific apoptosis in GFP-negative cells, whereas URi−URu represents HIV-specific apoptosis in GFP-positive cells. The peak of specific apoptosis in both GFP-positive and GFP-negative PBLs was concomitant with the peak of viral replication as determined by measurement of RT activity in culture supernatants (Figure 6B). Interestingly, a subpopulation of GFP-positive PBLs was resistant to apoptosis and usually was detected at the same time as or following the appearance of GFP-positive apoptotic PBLs (Fig. 6B). All cell populations were also tested for trypan blue exclusion and propidium iodide staining under nondetergent condition (36) and were uniformly negative by both tests (data not shown). The finding of a positive annexin-V assay result combined with a negative propidium iodide staining in nondetergent conditions is therefore consistent with apoptosis.

FIG. 6.

Apoptosis occurs predominantly in HIV-infected GFP-positive cells after infection of purified PBLs. (A) Two-color flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in PBLs infected with HIV-GFPS65T as measured by the TUNEL assay. Purified PBLs were left uninfected or were infected with HIV-GFPS65T. At day 11 postinfection, cells were harvested, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, and labeled by TUNEL assay (TdT labeling) as reported in Materials and Methods. By two-color flow cytometry, the cell population distribution was determined in both uninfected (ULu, URu, LRu) and infected (ULi, URi, LRi) PBLs. (B) Measurement of specific apoptosis in human PBLs infected with HIV-GFPS65T as determined by TUNEL and annexin-V assays. Purified PBLs were infected and analyzed as described for panel A. The histograms represent the PBL population distribution: apoptotic GFP-positive cells (solid bars; URi − URu), apoptotic GFP-negative cells (shaded bars; ULi − ULu), and nonapoptotic GFP-positive cells (open bars; LRi − LRu). RT activity (graphs) was measured in culture supernatants harvested from uninfected (○) and infected (▪) PBLs. Panels of TUNEL and annexin-V assays represent data obtained from two different donors, and each panel is representative of the results observed in five independent experiments using different donors. p.i., postinfection.

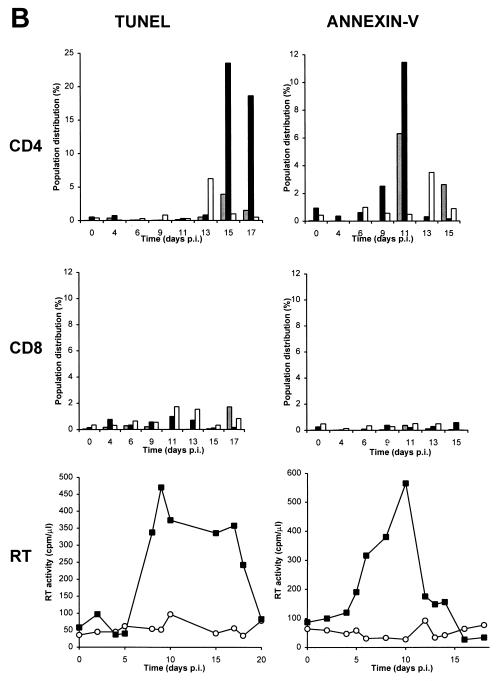

Apoptosis occurs almost exclusively in HIV-infected CD4+ T lymphocytes and not in CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection of purified PBLs.

To determine the PBL subpopulation which undergoes apoptosis during HIV infection, we infected purified PBLs with HIV-GFPS65T and monitored viral replication by measurement of RT activity in culture supernatants. After labeling cells with anti-human CD4 and anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibodies, we measured GFP expression and apoptosis by both TUNEL and annexin-V assays in both CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte populations (Fig. 7). Using three-color flow cytometry, we observed that specific apoptosis occurred almost exclusively in CD4+ T lymphocytes and not in CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 7). In CD4+ T lymphocytes, an increase in apoptosis was observed during HIV infection of GFP-negative cells (5.38 versus 1.46%); the extent of the increase was much larger for GFP-positive cells (55.78 versus 32.26%). The peak of specific apoptosis in CD4+ T lymphocytes was concomitant with the peak of viral replication or followed it by 24 to 48 h (Fig. 7B and data not shown). No significant apoptosis of PBLs was observed prior to the viral replication peak (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Nonapoptotic GFP-positive CD4+ T lymphocytes could be detected by both TUNEL and annexin-V assays at the time of or following the main peak of apoptosis (Fig. 7). CD8+ T lymphocytes showed less than 1% specific apoptosis even at the peak of viral replication (Fig. 7). The percentage of CD4+ T lymphocytes undergoing specific apoptosis ranged from 10 to 30% depending on the donors (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Using either the TUNEL or the annexin-V assay to measure apoptosis, we found as a rule that 90% of apoptotic CD4+ T lymphocytes were GFP positive, while only 10% were GFP negative after HIV-1 infection of purified PBLs (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Apoptosis occurs almost exclusively in HIV-infected GFP-positive CD4+ T lymphocytes and not in CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection of purified PBLs. (A) Three-color flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infected with the HIV-GFPS65T clone as measured by the TUNEL assay. Purified PBLs were left uninfected or were infected with the HIV-GFPS65T clone. At day 15 postinfection, cells were harvested, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by the TUNEL assay. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were labeled (TdT labeling) with anti-human CD4 and anti-human CD8 PerCP-labeled monoclonal antibodies. The cell population distribution (UL, UR, LR) for both uninfected and infected CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes was determined by three-color flow cytometry. (B) Measurement of specific apoptosis in human peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infected with the HIV-GFPS65T clone by the TUNEL and annexin-V assays. Purified PBLs were infected with the HIV-GFPS65T clone. RT activity was measured (graphs) in culture supernatants harvested from uninfected (○) and infected (▪) PBLs. A total of 5 × 106 cells were harvested at each time point, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, and labeled concomitantly by either TUNEL or annexin-V assays with anti-human CD4 or anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibodies. The cell population distribution for both uninfected and infected CD4+ and CD8+ PBLs was determined by three-color flow cytometry. The histograms represent the CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte population distribution: apoptotic GFP-positive cells (solid bars; URi − URu), apoptotic GFP-negative cells (shaded bars; ULi − ULu), and nonapoptotic GFP-positive cells (open bars; LRi − LRu). Panels showing the results of TUNEL and annexin-V assays represent data obtained from two different donors, and each panel is representative of results observed in five independent experiments with different donors. p.i., postinfection.

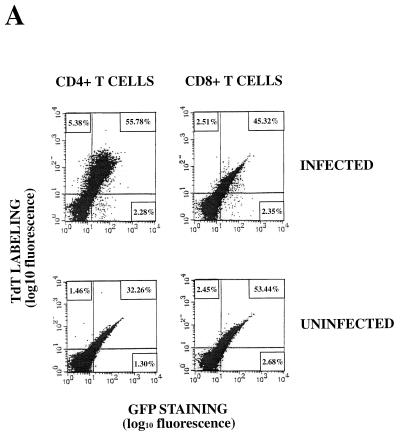

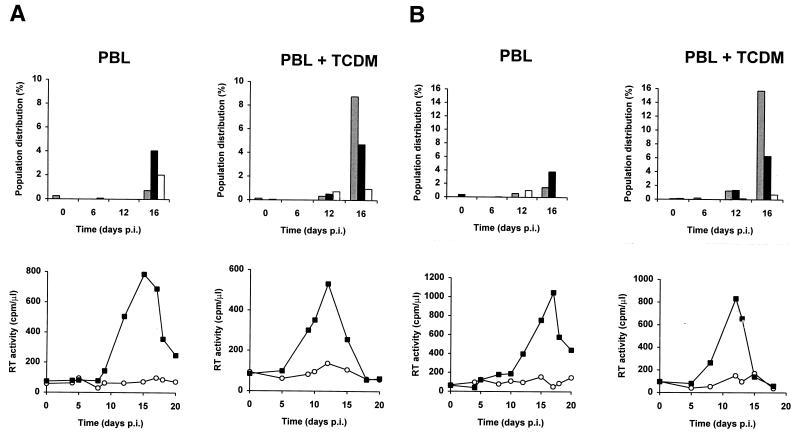

Monocyte-derived macrophages increase apoptosis in bystander uninfected T lymphocytes but not in HIV-infected T lymphocytes.

To determine whether antigen-presenting cells could modify the phenotype of apoptosis observed after HIV infection of purified PBLs, we combined measurements of GFP fluorescence, apoptosis by the TUNEL assay, and RT activity at several time points following infection of either purified PBLs or of a PBL–monocyte-derived macrophage coculture (Fig. 8). In contrast to purified PBLs, in which apoptosis occurred mostly in GFP-positive PBLs and to a lesser extent in GFP-negative PBLs, the presence of monocyte-derived macrophages dramatically enhanced the rate of apoptosis in GFP-negative PBLs but did not modify the rate of apoptosis in GFP-positive PBLs (Fig. 8). Therefore, in the presence of monocyte-derived macrophages and PBLs, HIV-specific apoptosis occurred at a significantly higher rate in GFP-negative than in GFP-positive PBLs. Specific apoptosis in both GFP-negative and GFP-positive PBLs was concommitant with the peak of viral replication, as determined by measurement of RT activity in culture supernatants (Fig. 8). A subpopulation of GFP-positive cells resistant to apoptosis was detected both in the presence and in the absence of monocyte-derived macrophages (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Monocyte-derived macrophages induce apoptosis in uninfected GFP-negative bystander T lymphocytes, but not in HIV-infected GFP-positive T lymphocytes. Measurement of specific apoptosis in human PBLs after infection of either purified PBLs (PBL) or PBLs and TCDM (PBL+TCDM) with HIV-GFPS65T as determined by a TUNEL assay. Either purified PBLs or cocultivated PBLs and TCDM were infected and analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 6. The histograms represent the PBL population distribution: apoptotic GFP-positive cells (solid bars; URi − URu), apoptotic GFP-negative cells (shaded bars; ULi − ULu), and nonapoptotic GFP-positive cells (open bars; LRi − LRu). RT activity was measured (graphs) in culture supernatants harvested from uninfected (○) and infected (▪) cells. Panels A and B represent data obtained from cells of different donors. p.i., postinfection.

DISCUSSION

We have used an HIV reporter virus expressing GFP to distinguish between infected and uninfected cells in a heterogeneous population. We observed that apoptosis occurs almost exclusively in CD4+ and not in CD8+ T lymphocytes during infection of purified PBLs. Ninety percent of CD4+ T lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis expressed GFP and therefore were infected, while 10% of cells did not and therefore represent either uninfected bystander cells or cells early in the infectious cycle. Monocyte-derived macrophages triggered apoptosis in GFP-negative uninfected bystander T lymphocytes and did not affect apoptosis in GFP-positive HIV-infected T lymphocytes. These observations demonstrate that HIV alone is capable of triggering apoptosis in infected CD4+ peripheral blood T lymphocytes and that, in purified PBLs, apoptosis is limited almost exclusively to infected cells. In contrast, antigen-presenting cells such as monocyte-derived macrophages are a key regulator of apoptosis in uninfected bystander T lymphocytes.

Previous studies have reported increased apoptosis during HIV infection: independently of the phase of HIV infection (acute, asymptomatic, or AIDS), lymphocytes isolated from infected individuals undergo accelerated apoptosis in comparison to lymphocytes from uninfected individuals (14, 18, 38). Interestingly, this increased apoptosis is much less pronounced when lymphocytes from HIV-2-infected individuals are examined. Since HIV-2 infection usually runs a milder clinical course, these observations suggest that apoptosis has a direct bearing on HIV pathogenesis and the development of immunodeficiency (23). Since productively infected cells are rare in the peripheral blood of infected individuals (46, 50), most of the lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis are probably uninfected and a direct cytopathic effect of HIV is probably not the sole mechanism. This possibility is supported by recent in vivo studies showing that apoptosis occurs predominantly in uninfected bystander T cells in lymph nodes of HIV-infected children and in SIV-infected monkeys (16).

Recent studies using inhibitors of HIV-1 protease showed that the turnover of HIV-infected CD4+ T lymphocytes in peripheral blood was higher than previously estimated and strictly dependent on virus production (21, 60), demonstrating a direct link between virus production and CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion. However, these data do not allow a distinction between direct and indirect cytopathic effects of HIV infection, and this question has therefore remained unanswered. While both direct and indirect mechanisms of HIV-induced apoptosis should respond therapeutically to a blockage of HIV replication, one can envision that an indirect mechanism could be modulated therapeutically without affecting virus replication. Such treatment would therefore circumvent the problem of HIV genome variability and the appearance of virus-resistant strains.

To differentiate between infected and uninfected cells, we have constructed a recombinant virus expressing GFP. Since the GFP cDNA replaces the nef open reading frame, we anticipate that GFP is expressed with kinetics identical to those of nef with respect to the virus life cycle, i.e., within the first 6 h postinfection (26). In addition, since GFP is not packaged within virus particles, GFP detection is strictly limited to infected cells, thereby alleviating a problem encountered when other viral proteins were used as markers for the specific detection of infected cells (10, 20a). Introduction of the GFP cDNA within our infectious HIV clone results in the deletion of the nef open reading frame. While nef is nonessential for virus replication in vitro, nef is a critical factor for HIV and SIV pathogenesis in SCID-hu mice and macaques, respectively (24, 25), and its deletion could therefore modify the ability of HIV to induce apoptosis. Since nef expression is restricted to the infected cell, any nef-mediated effect on apoptosis is likely to be limited to the infected cell. Therefore, it is unlikely that the indirect apoptosis mediated by monocytes/macrophages that we have observed is dependent on nef. In support of this contention, we have detected the same macrophage-dependent increase in apoptosis with several other isolates of HIV expressing a functional nef protein (20a). However, nef is likely to contribute to the direct apoptosis associated with virus replication since nef is an important factor in the replication of HIV in primary lymphocytes (40). To test these predictions, we will reconstruct the nef open reading frame in the context of our GFP-expressing recombinant virus and directly test the role of nef expression in HIV-induced apoptosis.

Our data demonstrate for the first time that HIV itself can kill CD4+ T lymphocytes directly via induction of apoptosis. The peak of apoptosis was concomitant with the peak of viral replication or followed it by 24 to 48 h, suggesting a direct link between viral replication and apoptosis. This form of apoptosis is mediated in a direct fashion by one of the viral products in the infected cell and does not involve the secretion of a toxic product in culture supernatant since uninfected cells are unaffected. We also observed that this form of apoptosis is independent of the presence of monocytes/macrophages in the culture system. As discussed above, given the enhancing role of nef expression in HIV replication in PBLs (20a, 40), we anticipate that direct apoptosis will be enhanced when examined in the context of a nef-expressing virus. Our results therefore demonstrate that the CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion observed in the absence of antigen-presenting cells occurs as a direct consequence of virus infection. Additionally, other mechanisms besides those studied here are at play in infected individuals since all our studies were performed on peripheral blood cells isolated from uninfected individuals, who were not experiencing an anti-HIV immune response. In vivo, cytotoxic T cells and antibodies directed against gp120 and other viral products can play additional and critical role in the induction of apoptosis. In future studies, we will examine the role of distinct HIV-encoded proteins by introducing mutations in the open reading frames of their genes.

Interestingly, we have reproducibly observed the emergence of a population of nonapoptotic HIV-infected (GFP-positive) cells. Such cells typically emerged after most of the infected T cells had undergone apoptosis and probably represent a subpopulation of T cells resistant to apoptosis induction by HIV. Previous reports have documented the existence of a subpopulation of T cells expressing low levels of CD4 that can support HIV-1 replication without demonstrating significant cytopathic effects (5, 28). Another possibility is that these T cells resistant to HIV-induced apoptosis constitute a pool of memory T cells refractory to apoptosis (57). Since apoptotic cells are short-lived and hard to detect in vivo, the emergence of infected and apoptosis-resistant cells in infected individuals could account for the observation that most infected T cells are nonapoptotic in vivo (16).

We demonstrate that HIV infection is associated with an increase in apoptosis in uninfected T cells. Surprisingly, we found that this increase is strictly dependent on the presence of monocytes/macrophages. Preliminary experiments indicate that this increase in apoptosis affects both uninfected CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations (20a). Previous studies have documented that, independently of HIV infection, monocytes/macrophages are required to prime peripheral blood T cells to undergo apoptosis (43, 62). Recent studies also indicate that macrophages play a critical role in inducing apoptosis in CD4+ cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals but not in CD4+ cells isolated from healthy individuals (7, 8). In this system, apoptosis was mediated by tumor necrosis factor and the Fas ligand (7, 8). Several other mechanisms have been proposed to explain the induction of apoptosis in uninfected bystander lymphocytes: cross-linking of surface CD4 (9, 44); secretion of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, lymphotoxin, and transforming growth factor β (49, 64); and secretion of soluble Tat protein (33, 37, 61). Interestingly, CD4 cross-linking has been reported to induce apoptosis in normal CD4+ T lymphocytes when the cross-linking is performed in unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells but not in purified PBL preparations (44). These data therefore support our observations on the critical role of macrophages in apoptosis induction.

In conclusion, we have established a new infection system for the study of HIV pathogenesis. This system is based on the in vitro infection of primary cells isolated from healthy individuals with a GFP-expressing recombinant HIV genome. We have used this system to systematically dissect the mechanism of HIV-induced apoptosis. Tagging of infected cells via expression of GFP has allowed the direct determination of apoptosis rates in both infected and uninfected populations. We demonstrate that distinct mechanisms underlie HIV-mediated apoptosis in infected and uninfected cells. In future studies, we will examine in greater detail the role of accessory cells and specific HIV-encoded gene products in these processes. It is anticipated that through such a systematic approach, the role of various factors, both viral and host dependent, will be closely defined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to C. A. Amella for help with cell culture and to H. Schmidmayerova and G. Zybarth for providing the primers (LTR and human tubulin) and recombinant GFP, respectively. We thank the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (NIAID, NIH, PHS) for reagents used in this study. We thank M. Laspia and A. Robson for reagents used in this study.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the NIH of the United States Public Health Service (AI40847-01A1) and by Institutional Funds from the Picower Institute for Medical Research. C. Van Lint is “Chargé de Recherches” of the Fond National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS, Belgium).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldrovandi G M, Feuer G, Gao L, Jamieson B, Kristeva M, Chen I S Y, Zack J A. The SCID-hu mouse as a model for HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1993;363:732–736. doi: 10.1038/363732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameisen J C, Capron A. Cell dysfunction and depletion in AIDS: the programmed cell death hypothesis. Immunol Today. 1991;12:102–105. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asjo B, Ivhed I, Gidlund M, Fuerstenberg S, Fenyo F M, Nilsson K, Wigzell H. Susceptibility to infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) correlates with T4 expression in a parental monocytoid cell line and its subclones. Virology. 1987;157:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene & Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badley A D, Dockrell D, Simpson M, Schut R, Lynch D H, Leibson P, Paya C V. Macrophage-dependent apoptosis of CD4+ T lymphocytes from HIV-infected individuals is mediated by Fas-L and tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1997;185:55–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badley A D, McElhinny J A, Leibson P J, Lynch D H, Alderson M R, Paya C V. Upregulation of Fas ligand expression by human immunodeficiency virus in human macrophages mediates apoptosis of uninfected T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:199–206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.199-206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banda N, Bernier J, Kurahara D K, Kurrle R, Haigwood N, Sekaly R P, Finkel T H. Crosslinking CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus gp120 primes T cells for activation-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1099–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benzair A B, Hirsch I, Chermann J C. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) to partially purified membrane vesicles of lymphoblastoid cell line CEM. J Virol Methods. 1993;45:319–330. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonyhadi M L, Rabin L, Salimi S, Brown D A, Kosek J, McCune J M, Kaneshima H. HIV induces thymus depletion in vivo. Nature. 1993;363:728–732. doi: 10.1038/363728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collin M, Herbein G, Montaner L J, Gordon S. PCR analysis of HIV-1 infection of macrophages: virus entry is CD4 dependent. Res Virol. 1993;144:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(06)80006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collman R, Balliet J W, Gregory S A, Friedman H, Kolson D L, Nathanson N, Srinivasan A. An infectious molecular clone of an unusual macrophage-tropic and highly cytopathic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1992;66:7517–7521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7517-7521.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estaquier J, Tanaka M, Suda T, Nagata S, Golstein P, Ameisen J C. Fas-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: differential in vitro preventive effect of cytokines and protease antagonists. Blood. 1996;87:4959–4966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauci A S. Multifactorial nature of human immunodeficiency virus disease: implications for therapy. Science. 1993;262:1011–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.8235617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkel T H, Tudor-Williams G, Banda N K, Cotton M F, Curiel T, Monks C, Baba T W, Ruprecht R M, Kupfer A. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat Med. 1995;1:129–138. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golding H, Robey F A, Gates F T, Linder W, Beining P R, Hoffman T, Golding B. Identification of homologous regions in human immunodeficiency virus I gp41 and human MHC class II beta 1 domain. I. Monoclonal antibodies against the gp41-derived peptide and patients’ sera react with native HLA class II antigens, suggesting a role for autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Exp Med. 1988;167:914–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gougeon M L, Garcia S, Heeney J, Tschopp R, Lecoeur H, Guetard D, Rame V, Dauguet C, Montagnier L. Programmed cell death in AIDS-related HIV and SIV infections. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:553–563. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groux H, Torpier G, Monte D, Mouton Y, Capron A, Ameisen J C. Activation-induced cell death by apoptosis in CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected asymptomatic individuals. J Exp Med. 1992;175:331–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haines D S, Gillespie D H. RNA abundance measured by a lysate RNase protection assay. Biotechniques. 1992;12:736–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Herbein, G., and E. Verdin. Unpublished data.

- 21.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imberti L, Sottini A, Bettinardi A, Puoti M, Primi D. Selective depletion in HIV infection of T cells that bear specific T cell receptor V β sequences. Science. 1991;254:860–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1948066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaleco A C, Covas M J, Victorino R M M. Analysis of lymphocyte cell death and apoptosis in HIV-2-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:185–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamieson B D, Aldrovandi G M, Planelles V, Jowett J B M, Gao L, Bloch L M, Chen I S Y, Zack J A. Requirement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef for in vivo replication and pathogenicity. J Virol. 1994;68:3478–3485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3478-3485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kestler H, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S Y, Byrn R, Groopman J, Baltimore D. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3708–3713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3708-3713.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger C P, Kuitjen G A, Keehnen R M, Pals S T, van Oers M H. Annexin-V for flow cytometry detection on B cells undergoing apoptosis. Blood. 1994;84:1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalski M, Bergerson L, Dorfman T, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Attenuation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cytopathic effect by a mutation affecting the transmembrane envelope protein. J Virol. 1991;65:281–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.281-291.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane H C, Drepper J M, Greene W C, Whalen G, Waldmann T A, Fauci A S. Qualitative analysis of immune function in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Evidence for a selective defect in soluble antigen recognition. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:79–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507113130204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laspia M F, Wendel P, Mathews M B. HIV-1 Tat overcomes inefficient transcriptional elongation in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:732–746. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurent-Crawford A G, Krust B, Muller S, Riviere Y, Rey-Cuille M A, Bechet J M, Montagnier L, Hovanessian A G. The cytopathic effect of HIV is associated with apoptosis. Virology. 1991;185:829–839. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90554-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis D E, NgTang D S, Adu-Oppong A, Schober W, Rogers J R. Anergy and apoptosis in CD8+ T cells from HIV-infected persons. J Immunol. 1994;153:412–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li C J, Friedman D J, Wang C, Metelev V, Pardee A B. Induction of apoptosis in uninfected lymphocytes by HIV-1 Tat protein. Science. 1995;268:429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.7716549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lifson J D, Reyes G R, McGrath M C, Stein B S, Engleman E G. AIDS retrovirus induced cytopathology: giant cell formation and involvement of CD4 antigen. Science. 1986;232:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.3010463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin S J, Matear P M, Vyakarnam A. HIV infection of human CD4+ T cells in vitro. Differential induction of apoptosis in these cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:330–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin S J, Reutlingsperger C P, McGahon A J, Rader J A, van Schie R C, LaFace D M, Green D R. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCloskey T W, Ott M, Tribble E, Khan S A, Teichberg S, Paul M O, Pahwa S, Verdin E, Chirmule N. Dual role of HIV Tat in regulation of apoptosis in T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:1014–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyaard L, Otto S A, Jonker R R, Mijnster M J, Keet R P M, Miedema F. Programmed cell death of T cells in HIV-1 infection. Science. 1992;257:217–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1352911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miedema F, Petit A J, Terpstra F G, Schattenkerk J K, De Wolf F, Al B J, Roos M, Lange J M, Danner S A, Goudsmit J, et al. Immunological abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected asymptomatic homosexual men. HIV affects the immune system before CD4+ T helper cell depletion occurs. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1908–1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI113809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller M D, Warmerdam M T, Gaston I, Greene W C, Feinberg M B. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosier D E, Gulizia R J, Baird S M, Wilson D B, Spector D H, Spector S A. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human-PBL-SCID mice. Science. 1991;251:791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1990441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosier D E, Gulizia R J, MacIsaac P D, Torbett B E, Levy J A. Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells in human-PBL-SCID mice infected by noncytopathic HIV isolates. Science. 1993;260:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.8097595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munn D H, Pressey J, Beall A C, Hudes R, Alderson M R. Selective activation-induced apoptosis of peripheral T cells imposed by macrophages. A potential mechanism of antigen-specific peripheral lymphocyte deletion. J Immunol. 1996;156:523–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oyaizu N, McCloskey T W, Coronesi M, Chirmule N, Kalyanaraman V S, Pahwa S. Accelerated apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infected patients and in CD4 cross-linked PBMCs from normal individuals. Blood. 1993;82:3392–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oyaizu N, McCloskey T W, Than S, Hu R, Kalyanaraman V S, Pahwa S. Cross-linking of CD4 molecules upregulates Fas antigen expression in lymphocytes by inducing interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion. Blood. 1994;84:2622–2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saksela K, Stevens C, Rubinstein P, Baltimore D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA expression in peripheral blood cells predicts disease progression independently of the number of CD4+ lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1104–1108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salter R D, Howell D N, Cresswell P. Genes regulating HLA class I antigen expression in T-B lymphoblast hybrids. Immunogenetics. 1985;21:235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00375376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarin A, Clerici M, Blatt S P, Hendrix C W, Shearer G M, Henkart P A. Inhibition of activation-induced programmed cell death and restoration of defective immune responses of HIV+ donors by cysteine protease inhibitors. J Immunol. 1994;153:862–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmid D S, Tite J P, Ruddle N H. DNA fragmentation: manifestation of target cell destruction mediated by cytotoxic T-cell lines, lymphotoxin-secreting helper T-cell clones, and cell-free lymphotoxin-containing supernatants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1881–1885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schnittman S M, Psallidopoulos M, Lane H C, Thompson L, Baseler M, Massari F, Fox C H, Salzman N P, Fauci A S. The reservoir for HIV-1 in human peripheral blood is a T cell that maintains expression of CD4. Science. 1989;245:305–308. doi: 10.1126/science.2665081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shearer G M, Bernstein D C, Tung K S K, Via C S, Redfield R, Salahuddin S Z, Gallo R C. A model for the selective loss of major histocompatibility complex self-restricted T cell immune responses during the development of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) J Immunol. 1986;137:2514–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodroski J, Goh W C, Rosen C, Campbell K, Haseltine W A. Role of HTLV-III/LAV envelope in syncytium formation and cytopathicity. Nature. 1986;322:470–474. doi: 10.1038/322470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Somasundaran M, Robinson H L. A major mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus-induced cell killing does not involve cell fusion. J Virol. 1987;61:3114–3119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3114-3119.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stefano K A, Collman R, Kolson D, Hoxie J, Nathanson N, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Replication of a macrophage-tropic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in a hybrid cell line, CEMx174, suggests that cellular accessory molecules are required for HIV-1 entry. J Virol. 1993;67:6707–6715. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6707-6715.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevenson M, Meier C, Mann A M, Chapman N, Wasiak W. Envelope glycoprotein of HIV induces interference and cytolysis resistance in CD4+ cells: mechanism for persistence in AIDS. Cell. 1988;53:483–496. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su L, Kanesima H, Bonyhadi M, Salimi S, Kraft D, Rabin L, McCune J M. HIV-1-induced thymocyte depletion is associated with indirect cytopathy and infection of progenitor cells in vivo. Immunity. 1995;2:25–36. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suda T, Tanaka M, Miwa K, Nagata S. Apoptosis of mouse naive T cells induced by recombinant soluble Fas ligand and activation-induced resistance to Fas ligand. J Immunol. 1996;157:3918–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terai C, Kornbluth R S, Pauza C D, Richman D D, Carson D A. Apoptosis as a mechanism of cell death in cultured T lymphoblasts acutely infected with HIV-1. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1710–1715. doi: 10.1172/JCI115188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Lint C, Ghysdael J, Paras P, Burny A, Verdin E. A transcriptional regulatory element is associated with a nuclease-hypersensitive site in the pol gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:2632–2648. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2632-2648.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Novak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Westendorp M O, Frank R, Ochsenbauer C, Stricker K, Dhein J, Walczak H, Debatin K M, Krammer P H. Sensitization of T-cells to CD95-mediated apoptosis by HIV-1 Tat and gp120. Nature. 1995;375:497–500. doi: 10.1038/375497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu M X, Daley J F, Rasmussen R A, Schlossman S F. Monocytes are required to prime peripheral blood T cells to undergo apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1525–1529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoffe B, Lewis D E, Petrie B L, Noonan C A, Melnick J L, Hollinger F B. Fusion as a mediator of cytolysis in mixtures of uninfected CD4+ lymphocytes and cells infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1429–1433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng L, Fisher G, Miller R E, Peschon J, Lynch D H, Lenardo M J. Induction of apoptosis in mature T cells by tumour necrosis factor. Nature. 1995;377:348–351. doi: 10.1038/377348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. T-cell-mediated immunopathology versus direct cytolysis: implication for HIV and AIDS. Immunol Today. 1994;15:262–268. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]