Abstract

Introduction:

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is commonly performed during radical prostatectomy (RP) for prostate cancer staging. This study aimed to comprehensively analyze existing evidence compare perioperative complications associated with standard (sPLND) versus extended PLND templates (ePLND) in RP patients.

Methods:

A meta-analysis of prospective studies on PLND complications was conducted. Systematic searches were performed on Web of Science, Pubmed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library until May 2023. Risk ratios (RRs) were estimated using random-effects models in the meta-analysis. The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using Review Manager software.

Results:

Nine studies, including three randomized clinical trial and six prospective studies, with a total of 4962 patients were analyzed. The meta-analysis revealed that patients undergoing ePLND had a higher risk of partial perioperative complications, such as lymphedema (I 2=28%; RR 0.05; 95% CI: 0.01–0.27; P<0.001) and urinary retention (I 2=0%; RR 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09–0.94; P=0.04) compared to those undergoing sPLND. However, there were no significant difference was observed in pelvic hematoma (I 2=0%; RR 1.65; 95% CI: 0.44–6.17; P=0.46), thromboembolic (I 2=57%; RR 0.91; 95% CI: 0.35–2.38; P=0.85), ureteral injury (I 2=33%; RR 0.28; 95% CI: 0.05–1.52; P=0.14), intraoperative bowel injury (I 2=0%; RR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.14–5.27; P=0.88), and lymphocele (I 2=0%; RR 1.58; 95% CI: 0.54–4.60; P=0.40) between sPLND and ePLND. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in overall perioperative complications (I 2=85%; RR 0.68; 95% CI: 0.40–1.16; P=0.16). Furthermore, ePLND did not significantly reduce biochemical recurrence (I 2=68%; RR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.28–1.24; P=0.16) of prostate cancer.

Conclusion:

This analysis found no significant differences in overall perioperative complications or biochemical recurrence between sPLND and ePLND, but ePLND may offer enhanced diagnostic advantages by increasing the detection rate of lymph node metastasis.

Keywords: complications, lymph node dissection, prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy, surgical procedures

Introduction

Highlights

The clinical benefits of pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) in men with PCa undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) have been a subject of controversy due to the limited availability of clear evidence, despite its status as the gold standard for cancer staging.

Through the analyses we derived no significant differences in overall perioperative complications or biochemical recurrence between sPLND and ePLND, but ePLND may offer enhanced diagnostic advantages by increasing the detection rate of lymph node metastasis.

This is the first meta-analysis of generalized prospective study on lymph node dissection in prostate cancer.

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) has been widely adopted as a standard procedure in radical prostatectomy (RP) for the management of prostate cancer (PCa) following its introduction by Walsh and other researchers in the 1980s1. The clinical benefits of PLND in men with PCa undergoing RP have been a subject of controversy due to the limited availability of clear evidence, despite its status as the gold standard for cancer staging2,3.

The extent of lymph nodes coverage provided by different templates can vary considerably among studies. However, the Prostate Cancer Guideline Panel of the European Association of Urology (EAU) has defined the limited template to include only the obturator lymph nodes, the extended pelvic lymph node dissection (ePLND) to include the internal iliac obturator, and external iliac nodes, and the standard pelvic lymph node dissection (sPLND) to encompass both the external iliac and obturator nodes4. Considerable debate still persists regarding the optimal extent of PLND. An extended approach to PLND is recommended by both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Association of Urology (EAU)5,6. In contrast to the guidelines of the EAU and NCCN, the American Urological Association (AUA) does not endorse a particular template for PLND. And the AUA emphasizes the need to weigh the benefits and risks associated with each approach. While some studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between the detection of positive pelvic lymph nodes and the extent of PLND, the therapeutic and diagnostic merits of a more expansive PLND persist as a contentious subject3,7–9. While certain studies suggest improved outcomes, others argue that PLND does not provide therapeutic advantages10,11.

To address this, we carried out a prospective study-based meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of ePLND compared to sPLND on complications and survival rates without biochemical recurrence (BCR) in patients undergoing RP.

Materials and methods

We followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)12, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR2)13 to conduct the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Literature search

Our search strategy involved conducting a comprehensive systematic literature review in four databases (Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Embase, and Pubmed) updated through May 2023, using the search string ‘(‘prostate cancer’) AND (‘pelvic lymph node dissection’ OR ‘pelvic lymphadenectomy’) AND (‘biochemical recurrence’ OR ‘complications’)’. Additionally, we searched the references of the included articles for additional relevant documents to enhance the comprehensiveness of our search.

Selection criteria

We conducted a meta-analysis of prospective studies on perioperative complications between standard dissection and extended dissection in patients with cancer who underwent RP. To be eligible for inclusion, the studies had to include at least two groups of patients: one group undergoing limited pelvic lymph node dissection (lPLND) or sPLND, and the other group undergoing ePLND. In order to ensure consistency in our analysis, we treated lPLND as sPLND. We excluded publication types such as letters, editorials, and reviews. Studies with unreported data, which hindered data collection for outcome measures, were also excluded. Our primary emphasis lay in assessing the incidence of perioperative complications and BCR.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Three reviewers (Ding, Wang, and Tang) were responsible for extracting, compiling, and conducting an in-depth review of the data. In cases of disagreements or uncertainty, discussions were held among the other researchers (Wu, Zou, and Cui) to reach a consensus. Key information, including publication year, study design, the first author, lymph node-positive rate, median number of lymph nodes retrieved, risk stratification, clinical stage, Gleason score, median PSA level, surgical approach (robotic, laparoscopic, or open), surgical method, several specific complication rates, and overall complications rate, were documented for each study and cohort on the PLND template. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was employed as a tool for evaluating the quality of learning curve studies since there is no specific risk of bias assessment tool available.

Statistical analysis

The Review Manager software (version 5.4.0)14 was used to analyze the data statistically. To evaluate the heterogeneity among the included studies, the I-square (I 2) and Q tests were employed. In cases where the heterogeneity was deemed considerable (P<0.05 and I 2 ≥50%), the random-effect model was employed. Conversely, the fixed-effect model was chosen for the purpose of meta-analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

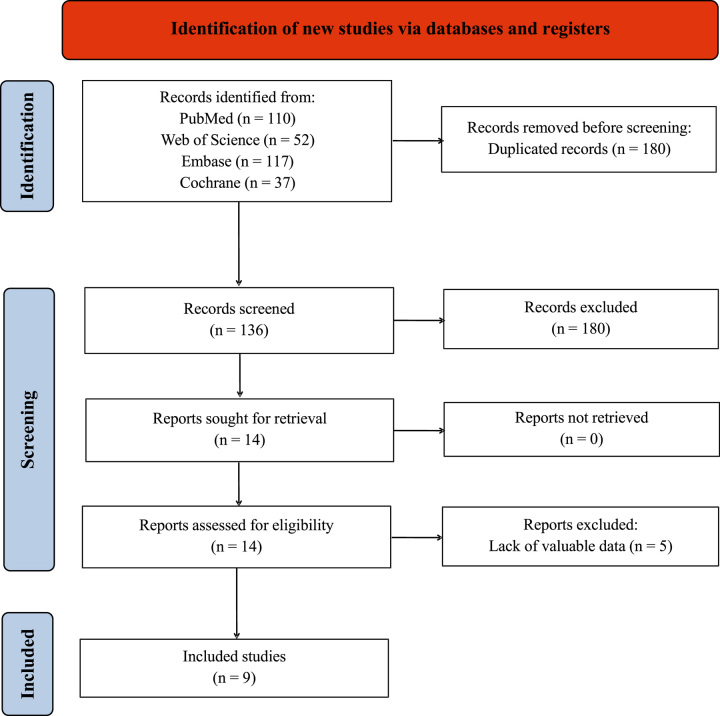

A total of 4962 patients across nine studies published from 2010 to 2021 were included in the analysis15–23. The identification of relevant studies was illustrated in Figure 1 through a flow diagram. A comprehensive search of four databases and examination of article references yielded 316 articles. After screening for duplicates and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 14 articles remained. Following a thorough review, nine articles met the criteria and were included in the final analysis. The exclusion of the remaining five articles were due to lack of valuable data.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process. RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Details of the included studies

Table 1 displays the details of nine articles included in our final analysis, specifically focusing on study designs. Among the included studies, three were randomized clinical trials (RCTs)15,16,19, and the remaining six were retrospective studies17,18,20–23. This analysis considered only studies with a comparison arm. Although several studies referred to ‘limited PLND’ as a comparison to ePLND, our criteria categorized both templates as sPLND. Two studies employed robot-assisted surgery20,21, two utilized laparoscopic surgery22,23, while five did not specify the surgical approach15–19.

Table 1.

Details of the included studies.

| Simple size | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Design | Experimental group | Control group | Trial | Control | Method |

| Eden et al. (2010)23 | UK | Prospective | ePLND | sPLND | 121 | 311 | Laparoscopic |

| Ryuji et al. (2011)17 | Japan | Prospective | ePLND | lPLND | 49 | 51 | Unknown |

| Rousseau et al. (2014)22 | France | Prospective | ePLND | sPLND | 127 | 176 | Laparoscopic |

| Yuh et al. (2013)21 | USA | Prospective | ePLND | lPLND | 202 | 204 | Robotic |

| Altok et al. (2018)20 | USA | Prospective | ePLND | sPLND | 282 | 282 | Robotic |

| Touijer et al. (2019)19 | USA | RCT | ePLND | sPLND | 757 | 723 | Unknown |

| Bogdanović et al. (2019)18 | Serbia | Prospective | ePLND | sPLND | 48 | 109 | Unknown |

| Lestingi et al. (2021)16 | Brazil | RCT | ePLND | lPLND | 40 | 40 | Unknown |

| Touijer et al. (2021)15 | USA | RCT | ePLND | sPLND | 740 | 700 | All surgical approaches |

ePLND, extended pelvic lymph node dissection; lPLND, limited pelvic lymph node dissection; sPLND, standard pelvic lymph node dissection.

Qualitative assessment of eligible studies

A total of six prospective studies and three RCTs were included in the review. Studies included in the review were rated as A or B in terms of quality. Additional information regarding the study quality can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of individual study.

| Study | Allocation sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Loss to follow-up | Calculation of sample size | Statistical analysis | Level of quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eden et al. (2010)23 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Ryuji et al. (2011)17 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Rousseau et al. (2014)22 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Yuh et al. (2013)21 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Altok et al. (2018)20 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Touijer et al. (2019)19 | A | A | A | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | A |

| Bogdanović et al. (2019)18 | A | A | B | 0 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

| Lestingi et al. (2020) | A | A | A | 17 | Yes | ANCOVA | A |

| Touijer et al. (2021)15 | A | A | B | 29 | Yes | ANCOVA | B |

A, all quality criteria met (adequate): low-risk of bias; B, most quality criteria met (adequate): moderate risk of bias; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 3 provides clinical characteristics, including clinical stage, Gleason score, median PSA, lymph node positivity, number of retrieved lymph nodes, and D’Amico risk stratification for the patient population in each study-based on the PLND template. The extended group demonstrated significantly higher values for both the percentage of patients with node-positive disease and the number of retrieved lymph nodes.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patient populations in each study separated according to PLND template.

| PSA, median(range) | Gleason score, mean (range) or mode (%) | Clinical stage, mode (%) | D’amico risk stratification | No. LNs Retrieved, median (IQR) | % pN1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Standard/limited | Extended | Standard/limited | Extended | Standard/limited | Extended | Standard/limited | Extended | Standard/limited | Extended | Standard/limited | Extended |

| Eden et al. (2010)23 | 11.0 (2–20) | 8.0 (1–15) | 7 (4–10) | 7 (6–10) | T2 (63%) | T2 (57%) | Intermediate | Intermediate | 6.1 (2–8) | 17 .5 (2–23) | 0.80% | 9.60% |

| Ryuji et al. (2011)17 | 9.9 (1.32–39.5) | 9.4 (0.9–31.9) | ≤7 (70.6%) | ≤7 (71.4%) | T1c (66.7%) | T1c (79.6%) | Unknown | Unknown | 8.3 (2–19) | 14.1 (5–33) | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Rousseau et al. (2013) | 11.3 (2.01–47) | 9 (1.45–66.4) | 7 (53.6%) | 7 (59%) | T1 (60.9%) | T1 (60.5%) | Intermediate | Intermediate | 6.7 (NA) | 15.6 (NA) | 5.70% | 18.90% |

| Yuh et al. (2013)21 | 5.9 (4.4–9.1) | 5.5 (4.2–8.3) | 3+4 (54.9%) | 3+4 (59.9%) | T1 (72.1%) | T1 (68.8%) | Intermediate | Intermediate | 7 (5–9) | 21.5 (17–27) | 3.90% | 11.90% |

| Altok et al. (2018)20 | 5.4 (4.2−7 .5) | 5.3 (4.1−8.1) | 3+4 (56%) | 3+4 (58%) | cT1 (65%) | cT1 (65%) | Intermediate | Intermediate | 8 (6–12) | 16 (11–21) | 5.00% | 13.00% |

| Touijer et al. (2019)19 | 5.9 (4.3–8.6) | 5.7 (4.2–8.2) | 8 (88%) | 8 (84%) | T1c (61%) | T1c (61%) | Unknown | Unknown | 12 (8–17) | 14 (10–20) | 12.00% | 14.00% |

| Bogdanović et al. (2019)18 | 10.30±5.08 | 12.44±4.41 | 7 (33.03%) | 7 (43.75%) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 17.27±5.66 | 24.46±10.98 | 8.25% | 16.67% |

| Lestingi et al. (2020) | 10.4 (6.9–13.9) | 10.5 (6.5–17) | 3+4 (38%) | 3+4 (42%) | T1 (52%) | T1 (57%) | Intermediate and high | Intermediate and high | 3 (2–5) | 17 (13–24) | 9.09% | 16.89% |

| Touijer et al. (2021)15 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 12 (8–17) | 14 (10–20) | 11.20% | 13.60% |

IQR, interquartile range; PSA, prostate specific antigen.

Perioperative and intraoperative outcomes

Blood loss and operative time

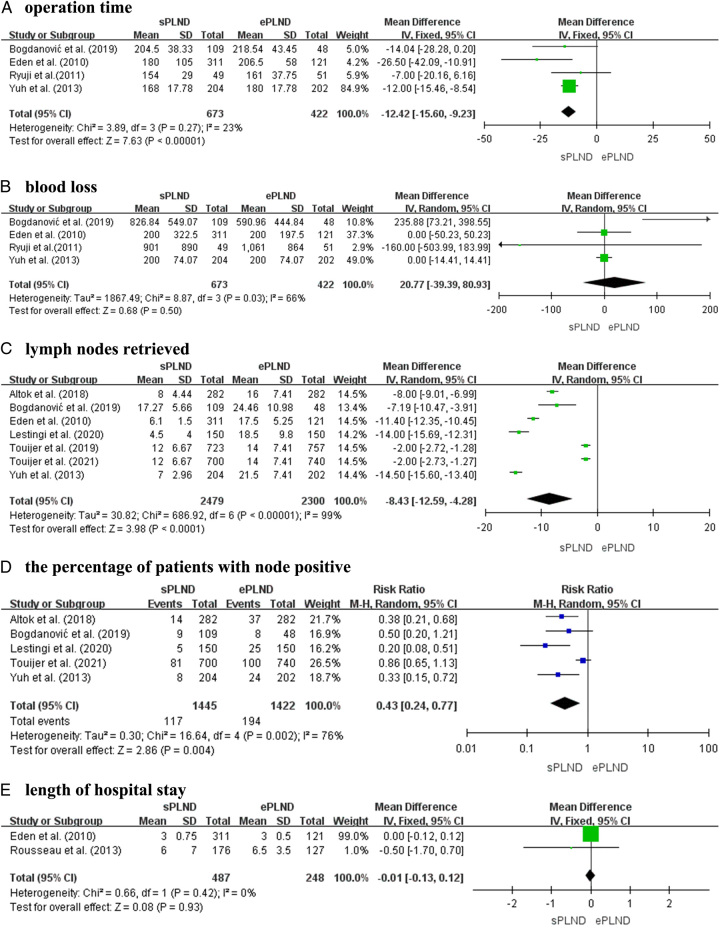

Four articles, encompassing four prospective studies with a total of 1095 patients, (673 patients undergoing sPLND and 422 undergoing ePLND), provided data on the surgical duration. A fixed-effects model analysis indicated a mean difference (MD) of −12.42 with 95% CI of −15.6 to −9.23 (P<0.001), suggesting that patients undergoing ePLND had longer surgical duration compared to those undergoing sPLND (Fig. 2A). However, there was no significant difference observed for blood loss (MD, 20.77; 95% CI: −39.39–80.93; P=0.50) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing the result of (A) operation time, (B) blood loss, (C) lymph nodes retrieved, (D) the percentage of patients with node-positive, and (E) length of hospital stay. Note. M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; df, degrees of freedom.

Lymph nodes retrieved

In seven articles, including four prospective studies and three RCTs, involving 2479 patients undergoing ePLND and 2300 patients undergoing sPLND, the number of retrieved lymph nodes was reported. A random-effects model analysis was conducted due to a significant P-value of less than 0.001. The MD was −8.43, with 95% CI of −12.59 to −4.28 (P<0.001) (Fig. 2C). Based on these findings, it was concluded that ePLND resulted in more lymph nodes being retrieved than sPLND.

The percentage of patients with node-positive

In the analysis of the proportion of patients with node-positive disease who underwent sPLND and ePLND, five studies were included. These studies consisted of three prospective studies and two RCTs, involving a combined total of 2867 participants, with 1445 patients undergoing sPLND and 1422 patients undergoing ePLND. The results indicated a significantly elevated proportion of patients afflicted with node-positive disease in the ePLND cohort as opposed to the sPLND cohort (RR 0.43; 95% CI: 0.24–0.77; P=0.004, I 2=76%) (Fig. 2D).

Length of hospital stays

Regarding the duration of hospitalization, data on this outcome measure were available from only two prospective studies, involving a total of 735 patients (487 sPLND patients and 248 ePLND patients). The analysis, conducted using a fixed-effects model, revealed no statistically difference in the duration of hospitalization between two groups (MD, −0.01; 95% CI: −0.13–0.12; P=0.93) (Fig. 2E).

Complications and efficacy

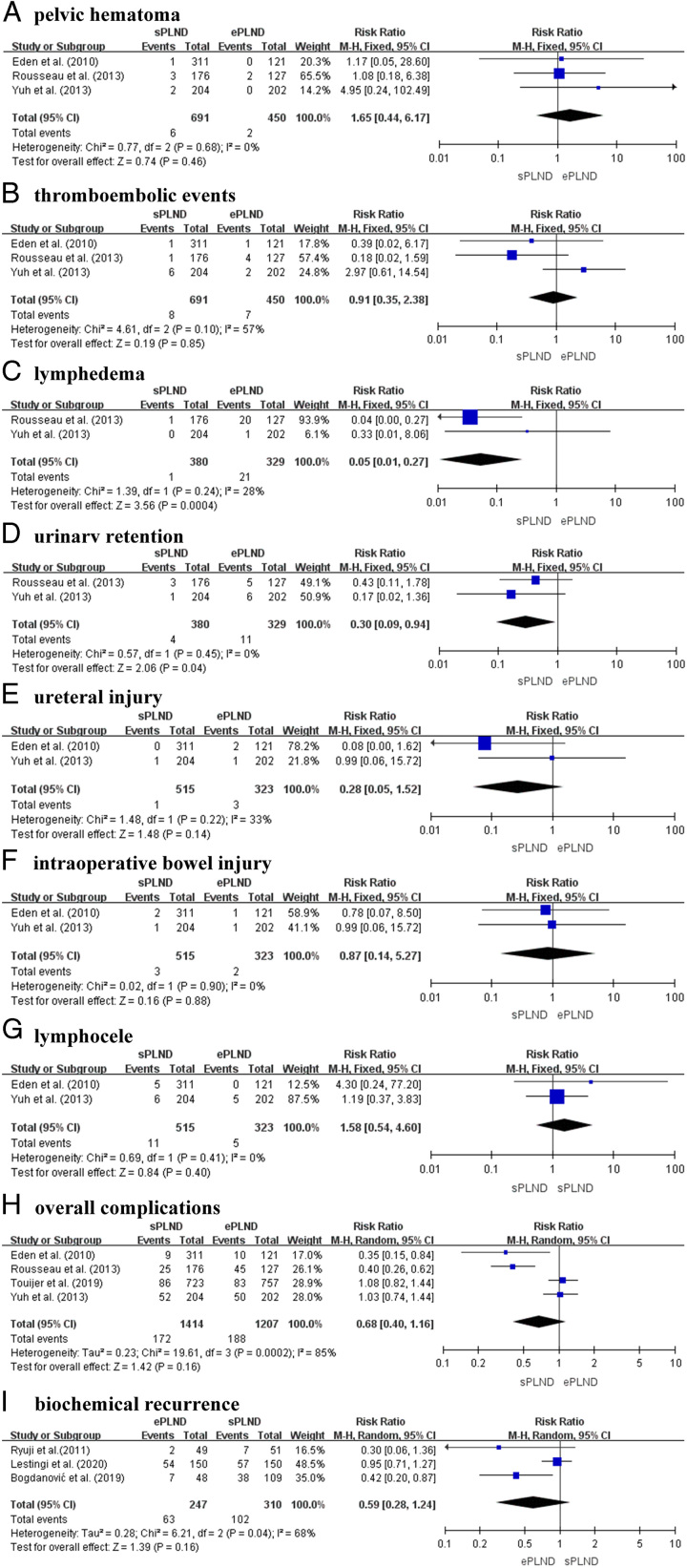

Three prospective studies, involving a total of 1141 patients (691 sPLND patients and 450 ePLND patients), provided data on the incidence rates of pelvic hematoma and thromboembolic events. The results indicated no significant difference in the incidence of pelvic hematoma (RR 1.65; 95% CI: 0.44–6.17; P=0.46, I 2=0%) (Fig. 3A) or thromboembolic events (RR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.11–4.55; P=0.71, I 2=57%) (Fig. 3B) between the sPLND and ePLND groups.

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the result of (A) pelvic hematoma, (B) thromboembolic events, (C) lymphedema, (D) urinary retention, (E) ureteral injury, (F) intraoperative bowel injury, (G) lymphocele, (H) overall complications and (I) biochemical recurrence in sPLND vs ePLND.

Two prospective studies, involving 709 participants (380 undergoing sPLND and 329 undergoing ePLND) were conducted to analyze the incidence rates of lymphedema and urinary retention between the two surgical techniques. The results revealed a significant increase in the incidence of lymphedema (RR 0.05; 95% CI: 0.01–0.27; P=0.0004, I 2=28%) (Fig. 3C) and urinary retention (RR 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09–0.94; P=0.04, I 2=0%) (Fig. 3D) in the ePLND group.

Two prospective articles provided data on the rates of ureteral injury, intraoperative bowel injury, and lymphocele in a total of 838 patients, including 515 sPLND patients and 323 ePLND patients. The analysis showed no significant differences in the rates of ureteral injury (RR 0.28; 95% CI: 0.05–1.52; P=0.14, I2=33%) (Fig. 3E), intraoperative bowel injury (RR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.14–5.27; P=0.88, I 2=0%) (Fig. 3F), and lymphocele (RR 1.58; 95% CI: 0.54–4.60; P=0.40, I 2=0%) (Fig. 3G) between the sPLND and ePLND groups.

Figure 3 presents the comparison of ePLND versus sPLND regarding the risk of perioperative complications, based on our meta-analysis of nine studies. Among 1414 patients who underwent sPLND, 172 (12.2%) experienced perioperative complications. In the ePLND group, which included 1207 patients, 188 (14.8%) encountered such complications. The findings from the included studies were diverse, with some indicating higher overall complication rates in ePLND group, while others showing slightly higher rates in sPLND group. Complication rates between sPLND and ePLND were not significantly different in our study (P=0.16). However, significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I 2=85%; P<0.001), indicating the need for a random-effects model. The relative risk of overall complications, as determined by the random-effects model, revealed no significant difference between the sPLND cohort and the ePLND cohort (RR, 0.68; 95% CI: 0.40–1.16) (Fig. 3H).

BCR

Three studies, consisting of two prospective studies and one RCT, encompassed a total of 557 participants (247 participants undergoing ePLND and 310 participants undergoing sPLND) and were utilized to assess the effect of two surgical procedures on BCR. The statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in BCR between sPLND and ePLND (RR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.28–1.24; P=0.16, I 2=68%) (Fig. 3I).

Discussion

Despite PLND being widely accepted as the gold standard for staging prostate cancer, the optimal extent of the surgical procedure remains uncertain3. While ePLND has been correlated with increased rates of nodal disease detection, it remains unclear whether this more extensive surgical approach leads to significant changes in complication incidence and BCR rates. In our study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of all available prospective studies that compared sPLND and ePLND, with a specific focus on reported rates of complications and BCR. Our objective was to quantitatively assess the disparities in the risks of complications and BCR between these two surgical templates.

Patients diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer, as indicated by PSA levels below 10 ng/ml, Gleason score below 7, and clinical stage no higher than T2a, are considered ineligible for PLND6,24. Nevertheless, patients diagnosed with high-risk prostate cancer (defined as a Gleason score of 8 or higher, clinical stage of T3a or higher, or PSA level exceeding 20 ng/ml) and a significant number of patients with intermediate-risk disease (characterized by clinical stage of T2b or T2c, PSA level ranging from 10 to 20 ng/ml, or a Gleason score of 7) – especially those exhibiting a primary Gleason grade 4 in the prostate biopsy - demonstrated a distinct need for PLND. In contemporary practice, the utilization of ePLND is advocated whenever lymph node dissection is indicated for these patients6. The literature incorporated in our study pertains to patients diagnosed with moderate to high-risk prostate cancer who meet the criteria for lymph node dissection surgery.

Our study found no significant difference in BCR between ePLND and sPLND, which is different from the conclusion of most previous studies that increasing the area of lymph node dissection has survival benefits11,25. One study found no significant difference in overall survival among patients with moderate to high-risk PCa who had RP with or without PLND26. Another study recently demonstrated for the first time that excessive lymph node dissection in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC) reduces the efficacy of immunotherapy, suggesting that unnecessary excessive dissection does not improve the long-term survival27. There were no significant differences in local recurrence and overall survival between patients with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis who underwent sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) alone and those who underwent complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)28. Compared to eLND only at the bifurcations of the aorta, LND extended to the inferior mesenteric artery (seLND) does not appear to benefit the overall population of patients with invasive bladder cancer29. These findings challenged the prevailing belief that extended lymph node dissection is superior, and could potentially influence the discussion-making process for the majority urologists regarding the implementation of extended or standard lymph node dissection.

Our analysis findings are consistent with previous reviews3,4 and reveal that there is no significant disparity in overall perioperative complications between ePLND and sPLND. There was no significant difference in overall complications between the two surgical approaches in this meta-analysis, which included four prospective studies involving 2621 patients. These findings are line with the majority of studies included in our analysis. Our findings contradict the results of a meta-analysis and review, which reported a statistically significant decrease in perioperative complication with sPLND compared to ePLND30. However, our findings are consistent with a previous meta-analysis finding no significant difference between ePLND and sPLND on overall complications31. Based on our analysis and the collective clinical experience of our authors, we believe that in the majority of cases involving RP with PLND, the utilization of an ePLND template imparts notable diagnostic benefits without a substantial escalation in the incidence of more frequent or severe complications.

ePLND is associated with a notable rise in the incidence of complications, including lymphedema and urinary retention, in comparison to sPLND. Moreover, the ePLND group exhibited a higher frequency of ureteral injury, intraoperative bowel injury, thromboembolism events, and overall complications. Notably, these complications were more prevalent on the side where the extended dissection was performed. Although statistical significance was not achieved for these differences, it is reasonable to infer that ePLND may lead to a slight but discernible increase in the incidence of complications.

Lymph node dissection is commonly performed during RP, primarily for diagnostic purposes rather than therapeutic benefits. The extended template has the potential to identify the staging of prostate cancer and facilitate the identification of lymph node metastasis, while minimizing the risk of additional complications. However, further investigation is required to ascertain whether improved staging has any significant impact on overall or cancer-specific survival outcomes. Nevertheless, there remains an ongoing discussion regarding the optimal extent of this procedure. Expanding the extent of dissection presents technical challenges; however, with the guidance of proficient urological surgeons or mentors, it does not increase the risk of complications. Therefore, careful consideration of the surgical expertise and individual patient characteristics is crucial when determining the appropriate extent of lymph node dissection during RP.

PSMA PET has developed rapidly in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in recent years, but PSMA PET cannot completely replace lymph node dissection32,33. In my opinion, PSMA scan cannot completely replace lymph node dissection. For patients with negative PSMA, it is still necessary to screen high-risk patients for PLND, mainly for the following reasons. First, PSMA PET-CT scan can detect small metastases in the body, but it requires a certain amount of tumor cells to accumulate in order to have positive imaging. When the number of tumor cells that have metastasized to the lymph nodes is relatively small, false-negative results are often obtained. Second, some prospective randomized controlled studies and some large-scale retrospective meta-analyses have found that even if we apply the most accurate PSMA PET-CT scan, there are still a considerable number of PSMA negative patients with lymph node metastasis, so the negative predictive value is relatively low34. Thirdly, in clinical practice, for high-risk patients with a risk stratification level of three or above (PSA>20 ng/ml, or clinical stage T3a or above, or Gleason score 8–10), if the PSMA scan results are negative, there is still a significant proportion at risk of false negatives32. Therefore, we cannot only rely on PSMA negativity to determine that patients do not need lymph node dissection. Although PSMA PET significantly improves the accuracy of diagnosing lymph nodes, for high-risk patients who may still have false negatives, the lymph node dissection cannot be omitted.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged in this meta-analysis. Firstly, the number of articles included in our analysis was limited, which reduces the strength of our findings. Additionally, the majority of studies we analyzed were prospective in nature, with only three RCTs, Secondly, there were variations in surgical techniques and baseline patient characteristics among the included studies, which introduces the potential for allocation bias and other confounding factors that may have influenced our results. Thirdly, there were inconsistencies in how the extent of surgery was defined and how complications were reported, which posed challenges in conducting a reliable meta-analysis. While some studies distinguished between lPLND and sPLND, we categorized all nonextended PLND cases into the sPLND group. Given these limitations, our meta-analysis indicates that when considering all surgical modalities, there is no significant difference in overall complications and BCR between ePLND and sPLND. Taking into account these qualifying limitations, our analysis reveals no difference of overall complications and BCR between sPLND and ePLND when considering all surgical modalities. The limitations mentioned above should be considered when interpreting these results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our meta-analysis provides valuable insights into the comparison between ePLND and sPLND in prostate cancer treatment. While no substantial disparities were observed in the occurrence of complications and rates of BCR, ePLND may offer enhanced diagnostic advantages by increasing the detection rate of lymph node metastasis. These findings can inform clinical decision-making and guide future research efforts in this field. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize the limitations of our study and continue to advance prostate cancer treatment research in order to enhance treatment outcomes and improve the quality of life for patients.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82370690, 82000649), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Nos. ZR2023MH241), and Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (Nos. tsqn201909199, tsqn202306403).

Author contribution

G.D. and G.T.: data curation, investigation, formal analysis, and writing – original draft; T.W.: data curation, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, visualization, and writing – original draft; G.D., T.W., and G.T.: formal analysis, investigation; methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing; Q.Z.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing; Y.C. and J.W.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, and writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: PROSPERO.

PROSPERO CRD number: CRD42023463787.

Register name: A Comparative Analysis of Perioperative Complications and Biochemical Recurrence between Standard and Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Guarantor

Guixin Ding, Gonglin Tang, Tianqi Wang, Qingsong Zou, Jitao Wu, and Yuanshan Cui.

Footnotes

Guixin Ding, Gonglin Tang, and Tianqi Wang contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 5 December 2023

Contributor Information

Guixin Ding, Email: 1923317213@qq.com.

Gonglin Tang, Email: tgl1136@163.com.

Tianqi Wang, Email: weatherking@hotmail.com.

Qingsong Zou, Email: zou_qingsong@126.com.

Yuanshan Cui, Email: doctorcuiys@163.com.

Jitao Wu, Email: wjturology@163.com.

References

- 1. Hyndman ME, Mullins JK, Pavlovich CP. Pelvic node dissection in prostate cancer: extended, limited, or not at all? Curr Opin Urol 2010;20:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palapattu GS, Singer EA, Messing EM. Controversies surrounding lymph node dissection for prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2010;37:57–65; Table of Contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Briganti A, Blute ML, Eastham JH, et al. Pelvic lymph node dissection in prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2009;55:1251–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fossati N, Willemse PPM, Van den Broeck T, et al. The benefits and harms of different extents of lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2017;72:84–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohler JL, Armstrong AJ, Bahnson RR, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016;14:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol 2017;71:618–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heidenreich A, Ohlmann CH, Polyakov S. Anatomical extent of pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2007;52:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Briganti A, Chun FKH, Salonia A, et al. A nomogram for staging of exclusive nonobturator lymph node metastases in men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2007;51:112–119; discussion 119-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Touijer K, Rabbani F, Otero JR, et al. Standard versus limited pelvic lymph node dissection for prostate cancer in patients with a predicted probability of nodal metastasis greater than 1%. J Urol 2007;178:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen J, Wang Z, Zhao J, et al. Pelvic lymph node dissection and its extent on survival benefit in prostate cancer patients with a risk of lymph node invasion >5%: a propensity score matching analysis from SEER database. Sci Rep 2019;9:17985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sood A, Keeley J, Palma‐Zamora I, et al. Extended pelvic lymph-node dissection is independently associated with improved overall survival in patients with prostate cancer at high-risk of lymph-node invasion. BJU Int 2020;125:756–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;10:Ed000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Touijer KA, Sjoberg DD, Benfante N, et al. Limited versus extended pelvic lymph node dissection for prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Urol Oncol 2021;4:532–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lestingi JFP, Guglielmetti GB, Trinh QD, et al. Extended versus limited pelvic lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy for intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer: early oncological outcomes from a randomized phase 3 trial. Eur Urol 2021;79:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsumoto R, Sakashita S. Prospective study of extended versus limited lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy with localized prostate cancer. Hinyokika Kiyo 2011;57:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bogdanovic J, Sekulic V, Trivunic-Dajko S, et al. Standard versus extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in the patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Vojnosanitetski Pregled 2019;76:929–934. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Touijer K, Sjoberg D, Benfante N, et al. Comparison between limited and extended lymph node dissection for prostate cancer: results from a large, clinically-integrated, randomized trial. J Urol 2019;201:E788. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Altok M, Babaian K, Achim MF, et al. Surgeon-led prostate cancer lymph node staging: pathological outcomes stratified by robot-assisted dissection templates and patient selection. BJU Int 2018;122:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuh BE, Ruel NH, Mejia R, et al. Standardized comparison of robot-assisted limited and extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer. BJU Int 2013;112:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rousseau B, Doucet L, Perrouin Verbe MA, et al. Comparison of the morbidity between limited and extended pelvic lymphadenectomy during laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Prog Urol 2014;24:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eden CG, Arora A, Rouse P. Extended vs standard pelvic lymphadenectomy during laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int 2010;106:537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol 2011;59:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fossati N, Parker WP, Karnes RJ, et al. More extensive lymph node dissection at radical prostatectomy is associated with improved outcomes with salvage radiotherapy for rising prostate-specific antigen after surgery: a long-term, multi-institutional analysis. Eur Urol 2018;74:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Preisser F, van den Bergh RCN, Gandaglia G, et al. Effect of extended pelvic lymph node dissection on oncologic outcomes in patients with D’Amico intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy: a multi-institutional study. J Urol 2020;203:338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deng H, Zhou J, Chen H, et al. Impact of lymphadenectomy extent on immunotherapy efficacy in post-resectional recurred non-small cell lung cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanvido VM, Elias S, Facina G, et al. Survival and recurrence with or without axillary dissection in patients with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis. Sci Rep 2021;11:19893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Møller MK, Høyer S, Jensen JB. Extended versus superextended lymph-node dissection in radical cystectomy: subgroup analysis of possible recurrence-free survival benefit. Scand J Urol 2016;50:175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kong J, Lichtbroun B, Sterling J, et al. Comparison of perioperative complications for extended vs standard pelvic lymph node dissection in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Exp Urol 2022;10:73–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gao L, Yang L, Lv X, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies on the efficacy of extended pelvic lymph node dissection in patients with clinically localized prostatic carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014;140:243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stabile A, Pellegrino A, Mazzone E, et al. Can negative prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography/computed tomography avoid the need for pelvic lymph node dissection in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis with backup histology as reference standard. Eur Urol Oncol 2022;5:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luiting HB, van Leeuwen PJ, Busstra MB, et al. Use of gallium-68 prostate-specific membrane antigen positron-emission tomography for detecting lymph node metastases in primary and recurrent prostate cancer and location of recurrence after radical prostatectomy: an overview of the current literature. BJU Int 2020;125:206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pozdnyakov A, Kulanthaivelu R, Bauman G, et al. The impact of PSMA PET on the treatment and outcomes of men with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2023;26:240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]