Abstract

The ie2 gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) is known to transactivate transient expression from viral promoters in a host cell-specific manner. We report that transfection of Spodoptera frugiperda (SF-21) cells with ie2 was sufficient to arrest the cell cycle, resulting in the accumulation of enlarged cells with abnormally high DNA contents. By 72 h posttransfection, more than 50% of ie2-transfected cells had DNA contents greater than 4N. There was no evidence of mitotic spindle formation in these cells, and expression of ie2 appeared to block cell cycle progression in S phase. Several ie2 mutants were analyzed to further define the region of IE2 responsible for arresting the cell cycle. Analysis of these mutants showed that deletion of the RING finger motif eliminated the ability of IE2 to arrest the cell cycle but did not affect its ability to transactivate the ie1 promoter. Moreover, mutation of a single conserved cysteine (C251) of the RING finger motif abolished the ability of IE2 to block cell cycle progression but had no apparent effect on its trans-regulatory activity. In contrast, a mutant of IE2 containing a deletion of residues 94 to 173 was able to block cell division but lacked trans-regulatory activity. Thus, the ability of IE2 to arrest the cell cycle depended on the integrity of the RING finger motif and was distinct from and independent of its ability to trans-activate the ie1 promoter. IE2 also arrested the division of cells derived from other insect species, Trichoplusia ni (TN-368 and BTI-TN-5B1-4) and Helicoverpa zea (Hz-AM1).

The product of the ie2 gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) is a ∼49-kDa protein, IE2, which activates the transient expression of plasmid-borne reporter genes under the control of viral promoters in SF-21 cells. IE2 was originally identified by its ability to trans-activate expression from the early AcMNPV 39K promoter in the presence of another viral trans-regulator, IE1 (5, 16). The effect of IE2 on expression from the 39K promoter was traced to the ability of the IE2 gene, ie2, to trans-activate expression from the ie1 promoter (6) in transient expression assays. In SF-21 cells, ie2 is also required, along with 17 other viral genes including ie1, for optimal transient expression from reporter plasmids carrying a late viral promoter (26, 32). In these assays, efficient late expression requires the replication and stability of the reporter plasmid carrying a viral homologous repeat sequence which binds IE1 and is thought to serve as an origin of DNA replication (18, 21, 33). The requirement of IE2 in optimizing plasmid DNA replication and late gene expression is host specific, since it is required in SF-21 cells but not in TN-368 cells (25, 35). The host dependence of IE2 may explain the observation that ie2 is nonessential for replication of the closely related baculovirus Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus (BmNPV) in Bombyx mori cells (13).

IE2 is a nuclear protein which contains a RING finger motif at its center (23, 40). RING fingers, or C3HC4 motifs, form a cross-braced zinc coordinating structure (11, 12, 24) and are found in a number of proteins of diverse function. The AcMNPV genome alone contains a total of five genes encoding proteins with RING finger motifs: IE2, CG30 (41), PE-38 (22), IAP1 (3, 8), and IAP2 (1). Although the RING finger motifs of the IE2s of both AcMNPV and BmNPV differ slightly in the spacing of one cysteine pair from the canonical RING finger motif, a canonical RING finger motif is found in the ie2 homolog of Orgyia pseudotsugata nuclear polyhedrosis virus (OpMNPV) (40). Like the RING finger-containing mammalian oncogene PML, AcMNPV IE2 and PE38 localize to discrete structures within the nucleus (23).

While studying the effects of early AcMNPV genes on apoptosis in SF-21 cells (34), we noticed that transfection of plasmids expressing ie2 resulted in the enlargement of the cells. We now report that ie2 expression blocked cell cycle progression but did not block cellular DNA replication, resulting in an increase in the number of cells with an abnormal DNA content, greater than 4N. In addition, we found that mutants of IE2 containing either a deletion of the RING finger motif or a mutation of an individual conserved amino acid residue of the RING finger motif lacked the ability to block cell division but retained the ability to trans-activate the ie1 promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Spodoptera frugiperda IPBL-SF-21 (SF-21) (44), Trichoplusia ni BTI-TN-5B1-4 (46) and TN-368 (20), and Helicoverpa zea Hz-AM1 (28) cells were cultured at 27°C in TC-100 medium (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.26% tryptose broth, as described previously (31).

Reporter plasmids and plasmid constructs.

The reporter plasmid phcIE1 (29) contains the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene under the transcriptional control of the ie1 promoter (17) and a portion of the hr-5 (37) sequences of AcMNPV.

Plasmid pBs-PstN, containing the AcMNPV PstI-N fragment (from 97.0 to 98.9 map units [m.u.], was described previously (32). Plasmid pBs-PstNfs has a frameshift mutation at the BglII site at 98.4 m.u. within the ie2 gene that results in the premature termination of IE2 synthesis. To construct pBs-PstNfs, pBs-PstN was digested with BglII, blunt-ended with T4 DNA polymerase, and then religated. The frameshift was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

To construct plasmid pBs-IE2Δ(94–173), pBs-PstN was digested with HpaI and SnaBI and then religated. Thus, pBs-IE2Δ(94–173) contains an in-frame deletion of the 237-bp HpaI-SnaBI fragment in the ie2 gene. The ie2 coding sequence also contains an HpaI-like site (ATTAAC), HpaI*, that can be digested with high concentrations of HpaI restriction enzyme. The 543-bp HpaI-HpaI* fragment was deleted from pBs-PstN by digestion with a high concentration of HpaI and replaced with the 363-bp HpaI-DraI fragment of ie2. The HpaI-DraI fragment was obtained by digestion of a PCR-amplified product of the AcMNPV ie2 gene with HpaI and DraI, followed by gel purification. The resulting plasmid, pBs-IE2Δ(215–274), contained an in-frame deletion of the 180-bp DraI-HpaI* fragment. Sequence analysis was used to confirm that pBs-IE2Δ(94–173) and pBs-IE2Δ(215–274) have the expected in-frame deletions of the HpaI-SnaBI and DraI-HpaI* fragments, respectively.

Plasmid pHSP70PLVI+CAT has been described previously (7) and contains the CAT gene under the transcriptional control of the Drosophila melanogaster hsp70 promoter (42). This plasmid was used to construct plasmid pHSP70FLAG-PLVI+ (provided by G. G. Prikhod’ko), which contains an in-frame sequence encoding a FLAG epitope tag (GACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAA) downstream of the hsp70 promoter. To construct pHSP70FLAG-IE2, expressing FLAG-ie2, the PCR-amplified ie2 open reading frame (ORF) was inserted into pHSP70FLAG-PLVI+. Primers used to amplify the ie2 gene were a 5′ primer in the sense orientation (5′-GCCGGATCCAATATGAGTCGCCAAATC-3′) and a 3′ primer in the antisense orientation (5′-TCCCCCGGGTTAACGTCTAGACATAACAG-3′). The same strategy was used to construct pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173) and pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(215–274). Site-specific mutagenesis was performed on pHSP70FLAG-IE2 with a Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit using the selection primer CATCAGAGTCGCTAGCGATGTAAACGATGG and the mutagenic primer CTGTGTACAAAGCTTTTTGCAGCGC to generate a mutant IE2 containing alanine instead of cysteine at residue 251 (pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A).

Transfection, transient expression assays, and CAT assays.

SF-21 cells (2.0 × 106 cells per 60-mm-diameter dish) were transfected with 2.0 μg of the reporter plasmid phcIE1 and 1.0 μg of each of the other plasmids by using Lipofectin (Gibco BRL). Transfected cells were incubated at 27°C and harvested at 24 h posttransfection. CAT assays (15, 37) were performed by using 1/50 of each cell lysate. In those experiments involving heat shock, the cells were heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection for 30 min at 42°C and then harvested 6 h after heat shock. The percentage of viable cells was determined at various times as described previously (7, 34).

Flow cytometry.

For flow cytometry, the medium was removed at the indicated times posttransfection and the cells were fixed and stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The cells were harvested and washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 6.2. After fixation in 80% ethanol for 30 min on ice, the cells were washed again with ice-cold PBS and stained with a solution containing 1 μg of DAPI per ml, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 μg of RNase A per ml in PBS. DAPI-stained cells were analyzed with a Coulter EPIC 753 flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, Fla.), as described previously (7).

Microphotography and immunofluorescence.

SF-21 cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 35-mm-diameter culture dishes and transfected with the indicated plasmids, as described above. At 48 h posttransfection, growth medium was aspirated and the cells were rinsed with PBS (pH 6.2) and fixed in methanol at −10°C for 20 min, followed by two washes in PBS. To detect the microtubule network, cells were incubated with a 1:500 dilution of DM1 anti-alpha tubulin (Sigma) in PBS containing 1 μg of DAPI per ml for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were washed in PBS and incubated with a 1:50 dilution of lissamine rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) in PBS. Cells were washed twice in PBS and mounted on glass slides in Gelmount.

Immunoblot analysis.

Transfected cells were heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection and harvested 3 h after heat shock. Cells were lysed in SDS buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 125 mm Tris-HCl [pH 6.7], 30% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.002% [wt/vol] bromphenol blue, 2% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol). Proteins from lysates of the transfected cells were separated on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). FLAG-tagged proteins were detected with a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Eastman Kodak Co., New Haven, Conn.) followed by a 1:10,000 dilution of rabbit anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Amersham). Immunoblots were visualized by the chemiluminescence method (Amersham).

RESULTS

Expression of AcMNPV ie2 blocks cell division.

By light microscopy, we observed that SF-21 cells transfected with a plasmid containing the PstI-N fragment of the AcMNPV genome, pBs-PstN, became enlarged by 48 h posttransfection (Fig. 1A). The pBs-PstN-transfected cells continued to increase in size until 72 h and existed in this enlarged state for more than 96 h after transfection without obvious signs of stress (data not shown). This unusual morphology was not detected in SF-21 cells transfected with the vector plasmid pBluescript KS+ (pBs) (Fig. 1B).

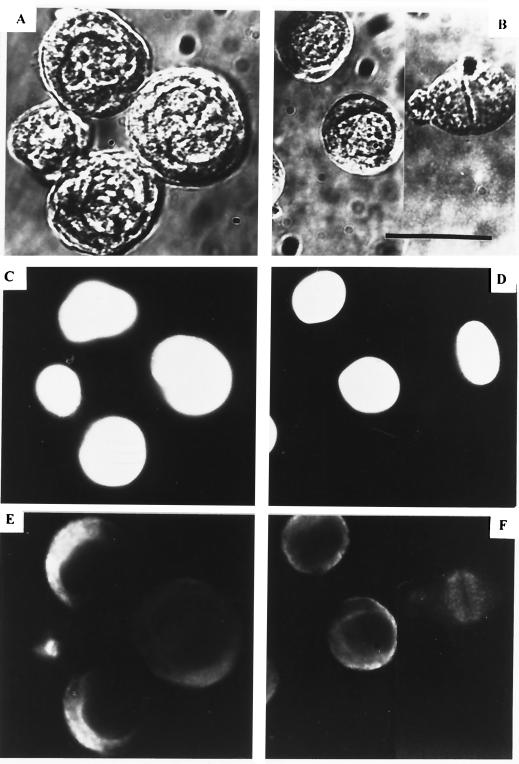

FIG. 1.

Expression of the AcMNPV PstI-N fragment blocks cell division. SF-21 cells (0.5 × 106 per 35-mm-diameter dish) were transfected either with 0.5 μg of plasmid pBs-PstN (A, C, and E) or with the same amount of the control vector plasmid, pBs (B, D, and F). At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed in methanol and then double stained with DAPI (C and D) and DM1 anti-alpha tubulin (E and F), and the same field of cells was examined by phase-contrast (A and B) and immunofluorescence (C to F) microscopy. All cells were photographed at the same magnification; note the larger sizes of the cells transfected with pBs-PstN. Also, one of the four cells in panels A, C, and E does not appear to have been transfected with pBs-PstN. In panels B and F, mitotic spindles can be observed in the cell on the right. Bar, 25 μm. (G) SF-21 cells were transfected with either pBs or pBs-PstN and harvested after 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, and the numbers of viable cells were counted in the presence of trypan blue.

To test whether enlargement of the cells was accompanied by enlargement of the nucleus, SF-21 cells were transfected with either the pBs-PstN plasmid or pBs and stained at 48 h posttransfection with DAPI, which is specific for DNA. The pBs-PstN-transfected cells were observed to contain a single enlarged nucleus (Fig. 1; compare panels C and D). We also analyzed the effect of pBs-PstN transfection on the microtubule network by immunofluorescence staining of pBs-PstN-transfected cells. The microtubule network was characteristic of nonmitotic cells and was similar to that of nonmitotic pBs-transfected cells (Fig. 1; compare panels E and F). There was no evidence of the extension of mitotic spindles in the enlarged pBs-PstN-transfected cells (Fig. 1E), whereas mitotic spindle formation was observed in some of the control pBs-transfected cells (Fig. 1B and F).

To determine if transfection with pBs-PstN affected cell division, the number of viable SF-21 cells was quantified by staining of the pBs-PstN- or pBs-transfected cells with 0.04% trypan blue (Fig. 1G). By 48 h posttransfection, the number of cells in the control pBs-transfected culture had increased more than fourfold, and by 96 h the cells had undergone three to four rounds of division. In contrast, no significant increase in cell number was obtained in the culture transfected with pBs-PstN from 24 to 96 h posttransfection. By 72 h, the cell numbers in the pBs-PstN-transfected culture were less than 30% of those observed for the control cells. The gradual increase in viable cells observed in the pBs-PstN-transfected culture is probably due to division of cells which did not acquire pBs-PstN during the transfection process. There was no evidence of apoptosis or necrotic cell death in the cultures; there were no signs of membrane blebbing, oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation, or cell debris (data not shown). Thus, transfection of SF-21 cells with pBs-PstN blocked cell division.

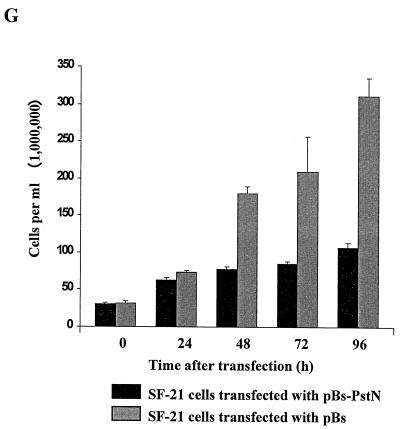

The PstI-N fragment of the AcMNPV genome contains ie2 and three smaller ORFs (Fig. 2). Transfection of pBs-PstNfs, a plasmid containing the PstI-N fragment with a frameshift mutation at the BglII site within the ie2 coding sequence (Fig. 2), failed to block cell division (data not shown). These results suggest that ie2 was probably the gene affecting cell cycle progression upon transfection of SF-21 cells with pBs-PstN.

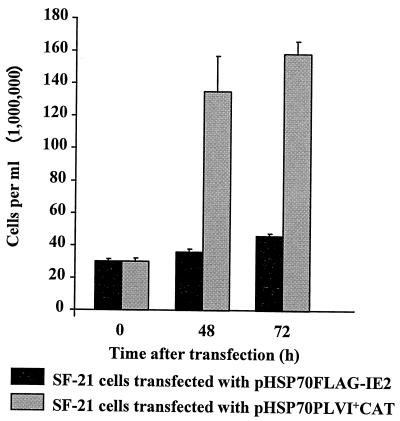

FIG. 2.

Physical map of the 96.9- to 0.0-m.u. region of AcMNPV with a partial restriction map. Locations and directions of ORFs between 96.9 and 0.0 m.u. are based on the sequence determined by Ayres et al. (1). Schematic representations of wild-type and mutant forms of ie2 are shown below the lines representing each plasmid. The RING finger motif is indicated by the shaded R box. Restriction sites are abbreviated as follows: HIII, HindIII; PI, PstI; HI, HpaI; B, BglII; S, SnaBI; D, DraI; HI*, HpaI-like site (see Materials and Methods).

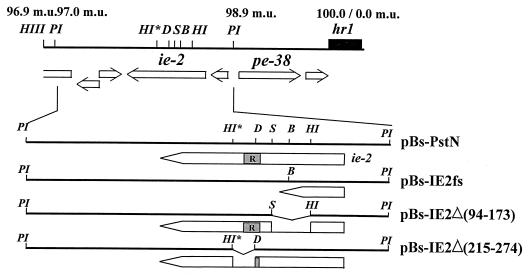

To determine if expression of the ie2 coding sequence alone was able to block cell division, we transiently expressed ie2 by transfecting SF-21 cells with pHSP70FLAG-IE2, a plasmid containing the N-terminally FLAG-tagged, PCR-amplified ORF of IE2 under the transcriptional control of the D. melanogaster hsp70 promoter. Plasmid pHSP70PLVI+CAT, which expresses the CAT gene, served as a control. Less than a twofold increase in the number of viable cells was observed for cells transfected with pHSP70FLAG-IE2 through 72 h posttransfection, whereas pHSP70PLVI+CAT-transfected cells underwent normal cell division (SF-21 cells normally double every 18 to 24 h [31]) and increased in number more than fivefold by 72 h posttransfection (Fig. 3). This effect of pHSP70FLAG-IE2 was also confirmed by light microscopy analysis of the transfected cells; by 48 h posttransfection, pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected cells had become enlarged compared with control transfected cells (see below). Thus, IE2 blocked cell division and caused cell enlargement following transient expression.

FIG. 3.

Expression of ie2 arrests the cell cycle. SF-21 cells were transfected with either pHSP70FLAG-IE2 or control pHSP70PLVI+CAT and heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection. At 48, 72, and 96 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and counted as described in Materials and Methods.

IE2 arrested the cell cycle in the S phase.

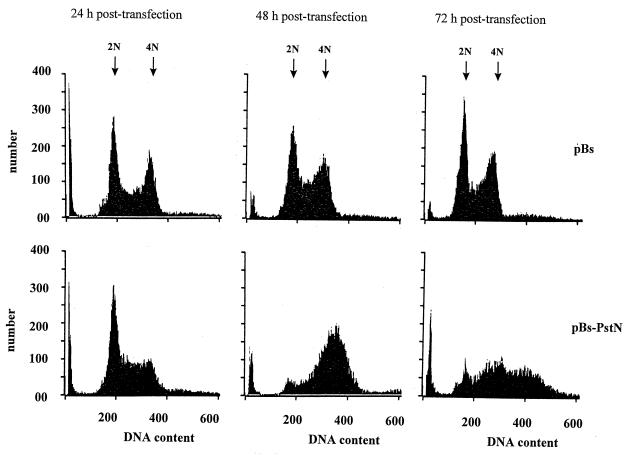

To determine whether IE2 prevented cell division by arresting cells at a specific point in the cell cycle, we analyzed the DNA content of ie2-transfected cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). Cells transfected with the control plasmid pBs had similar DNA profiles at 24, 48, and 72 h posttransfection (Fig. 4), correlating with stable 4N:2N DNA content ratios of 0.93, 0.92, and 0.94, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, significant changes occurred in the cell cycle distribution of SF-21 cells transfected with pBs-PstN expressing ie-2 (Fig. 4). At 24 h posttransfection, a lower proportion of pBs-PstN-transfected cells appeared to have a 4N complement of DNA, and greater proportions were found in the G1 and S phases (Fig. 4; Table 1). At 48 h posttransfection, a large proportion of ie2-expressing cells contained a 4N or higher amount of DNA compared with cells transfected with the control, pBs (Fig. 4; Table 1). By 48 h, the 4N:2N DNA content ratio had increased to 5.4 in pBs-PstN-transfected cells, compared to 0.92 in control cells (Table 1). By 72 h posttransfection, more than 50% of the pBs-PstN-transfected cells had abnormal DNA contents of greater than 4N (Fig. 4; Table 1), indicating that expression of ie2 blocks cell division and that cellular DNA replication continues. On the basis of these data and the lack of mitotic spindle formation, it appears that ie2 arrested SF-21 cells in the S phase of the cell cycle and that the normal control of cellular DNA replication was altered.

FIG. 4.

DNA content analysis in ie2-transfected cells. SF-21 cells were transfected with either pBs-PstN expressing ie2 or the vector alone (pBs). The cells were washed, fixed, and stained with DAPI at the indicated times. Histograms show the results of flow cytometric analysis of DAPI staining intensity. The abscissas show relative amounts of DAPI fluorescence, reflecting DNA content, and the ordinates show cell numbers. The results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

IE2 arrests SF-21 cell division but not DNA replicationa

| Plasmid (time posttransfection [h]) | DNA content (%)

|

4N:2N ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2N | 2N–4N | 4N | >4N | ||

| pBs (24) | 38.2 | 15.6 | 35.6 | 10.6 | 0.93 |

| pBs-PstN (24) | 43.2 | 20.0 | 27.2 | 9.6 | 0.62 |

| pBs (48) | 38.6 | 17.9 | 35.5 | 8.0 | 0.92 |

| pBs-PstN (48) | 7.6 | 8.4 | 40.7 | 43.3 | 5.4 |

| pBs (72) | 41.9 | 8.7 | 39.4 | 10.0 | 0.94 |

| pBs-PstN (72) | 11.9 | 8.4 | 27.6 | 52.2 | 2.3 |

SF-21 cells were transfected with either pBs or pBs-PstN and analyzed by flow cytometry at different times posttransfection. The percentage of cells containing 2N, 4N, or more than 4N DNA in each cell culture (Fig. 4) was derived from histograms of the DNA content.

Deletion of the RING finger region blocked the ability of IE2 to arrest the cell cycle.

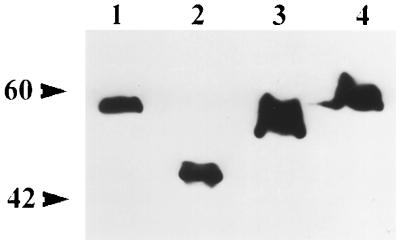

To determine if a specific region of IE2 was important for its ability to arrest the cell cycle, we constructed two deletion mutants of IE2 and tested their transactivation capabilities and their effects on cell cycle progression in transient assays. Plasmid pBs-IE2Δ(215–274) has an in-frame deletion of the DraI-HpaI* fragment resulting in the deletion of amino acids 215 to 274, thereby eliminating the RING finger motif from IE2 (Fig. 2). In pBs-IE2Δ(94–173), the HpaI-SnaBI fragment of PstI-N was deleted, leaving the RING finger domain intact but deleting amino acids 94 to 173 (Fig. 2), including several arginine, proline, and serine residues that are conserved between the AcMNPV and OpMNPV ie2 genes. To ensure that the ie2 deletion mutants could be expressed in SF-21 cells, we also constructed plasmids containing FLAG-tagged coding sequences of the ie2 mutants under hsp70 promoter control. These constructs, pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173) and pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(215–274), as well as pHSP70FLAG-IE2, were tested for expression in SF-21 cells (Fig. 5). Plasmids pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173), pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(215–274), and pHSP70FLAG-IE2 were transfected into SF-21 cells, followed by heat shock treatment. FLAG-IE2 and IE2Δ(94–173) showed comparable levels of expression (Fig. 5; compare lanes 1 and 2). Slightly higher levels of expression were observed for the IE2Δ(215–274) mutant protein (Fig. 5, lane 3).

FIG. 5.

Expression of FLAG-IE2 and FLAG-IE2 mutants. SF-21 cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of pHSP70FLAG-IE2 (lane 1), pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173) (lane 2), pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(215–274) (lane 3), or pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A (lane 4), heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection, and harvested 3 h after heat shock. Equal amounts of cell lysates were analyzed by SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody.

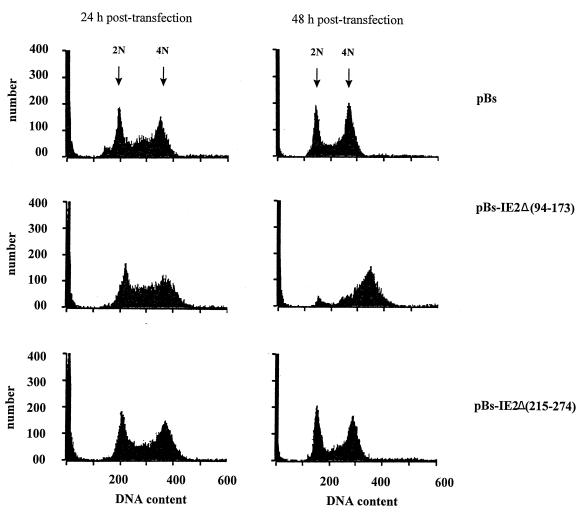

To test if these deletion mutants were able to arrest cell division, SF-21 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing either the normal or FLAG-tagged versions of ie2Δ(94–173) or ie2Δ(215–274) and examined by light microscopy as well as by flow cytometry. Enlarged cells were not observed in cultures transfected with pBs-IE2Δ(215–274), while pBs-IE2Δ(94–173) caused the enlarged cell phenotype (data not shown). At 24 and 48 h posttransfection, pBs-IE2Δ(94–173)-transfected cells had DNA profiles similar to those of cells transfected with pBs-PstN expressing intact ie2 (compare Fig. 6, middle row, with Fig. 4, bottom row). Thus, deletion of residues 94 to 173 of IE2 did not affect its ability to block the cell cycle. SF-21 cells transfected with pBs-IE2Δ(215–274) had a stable cell cycle distribution, similar to that of cells transfected with the vector alone (Fig. 6). This demonstrated that deletion of the RING finger region eliminated the ability of IE2 to affect the cell cycle.

FIG. 6.

DNA content analysis of SF-21 cells transfected with deletion mutants of ie2. SF-21 cells were transfected with pBs-IE2Δ(94–173), pBs-IE2Δ(215–274), or the control vector plasmid, pBs. Transfected cells were harvested at 24 or 48 h posttransfection. After being washed, fixed, and stained with DAPI, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. DAPI fluorescence is plotted on the x axes and is proportional to DNA content. Cell numbers are shown on the y axes.

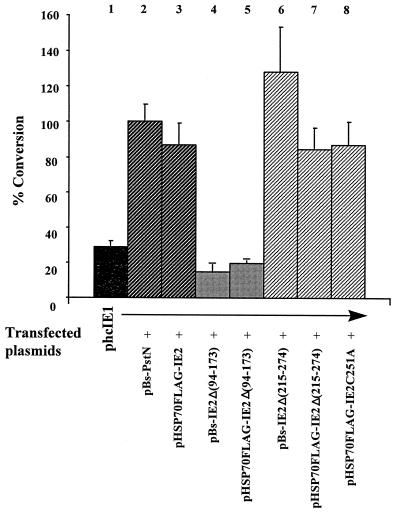

Transactivation properties of IE2 mutants.

To determine if the IE2 deletion mutants retained transregulatory activity, we analyzed their abilities to activate expression from phcIE1, a reporter plasmid containing the CAT gene under ie1 promoter control. When SF-21 cells were cotransfected with phcIE1 and pBs-PstN or pHSP70FLAG-IE2 expressing ie2 under the control of either its own promoter or the hsp70 promoter, the levels of CAT activity increased approximately threefold compared with that in cells transfected with the reporter plasmid alone (Fig. 7; compare lane 1 with lanes 2 and 3). Higher levels of CAT activity were also observed for cells cotransfected with phcIE1 and plasmids expressing ie2Δ(215–274) (Fig. 7, lanes 6 and 7). Thus, deletion of the RING finger motif did not impair the ability of IE2 to activate the ie1 promoter. Plasmids pBs-IE2Δ(94–173) and pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173) were not able to transactivate the CAT gene under ie1 promoter control (Fig. 7, lanes 4 and 5). Moreover, the levels of CAT activity in these cells were approximately twofold lower than in cells transfected with the reporter plasmid alone, suggesting interference with factors responsible for ie1 promoter activation or direct repression of the ie1 promoter.

FIG. 7.

Transactivation of the ie1 promoter by IE2 deletion mutants. SF-21 cells were transfected with the reporter plasmid phcIE1 alone or cotransfected with phcIE1 and pBs-PstN, pBs-IE2Δ(94–173), pBs-IE2Δ(215–274), pHSP70FLAG-IE2, pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(94–173), pHSP70FLAG-IE2Δ(215–274), or pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A. CAT activity relative to that from phcIE1 cotransfected with wild-type ie2 under its own promoter (lane 2, 100%) was determined. The data are averages of two or more experiments, and standard errors are indicated.

Site-specific mutation of the IE2 RING finger.

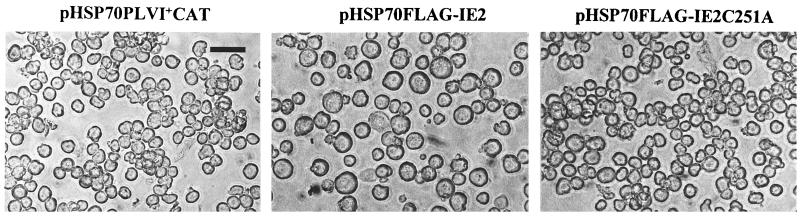

To determine if the RING finger was specifically involved in blocking cell cycle progression, we constructed pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A, a plasmid containing FLAG-tagged IE2 with an alanine in place of one of the seven conserved cysteine residues of the IE2 RING finger motif. Transient expression of pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A in SF-21 cells did not result in an enlargement of the cell size (Fig. 8). Analysis of the trans-regulatory activity of FLAG-IE2C251A showed that this mutant was able to stimulate levels of CAT activity from the ie1 promoter comparable to that determined for wild-type IE2 (Fig. 7; compare lanes 3 and 8). Thus, modification of a single conserved residue of the RING finger motif of IE2 abolished its ability to arrest the cell cycle but did not affect its trans-regulatory activity.

FIG. 8.

Effects of FLAG-IE2C251A on cell size and growth. SF-21 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the FLAG-tagged version of wild-type (pHSP70FLAG-IE2) or RING finger mutant (pHSP70FLAG-IE2C251A) IE2 or with the control CAT gene (pHSP70PLVI+CAT) and examined by light microscopy at 72 h posttransfection. Bar, 50 μm.

These results confirmed that the RING finger motif of IE2 is important for the ability of this gene to block cell division but is not responsible for the ability of IE2 to transactivate the ie1 promoter. Furthermore, this transactivation ability of IE2 is distinct from its ability to block the cell cycle, since the IE2Δ(94–173) mutant lacking transactivation potential can block cell division.

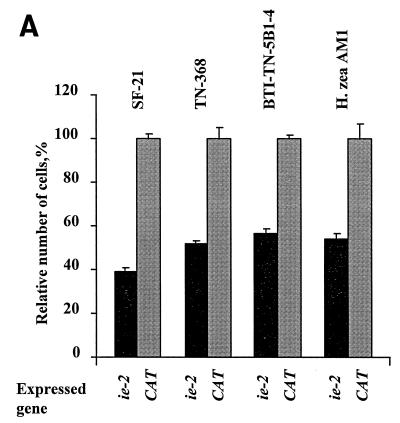

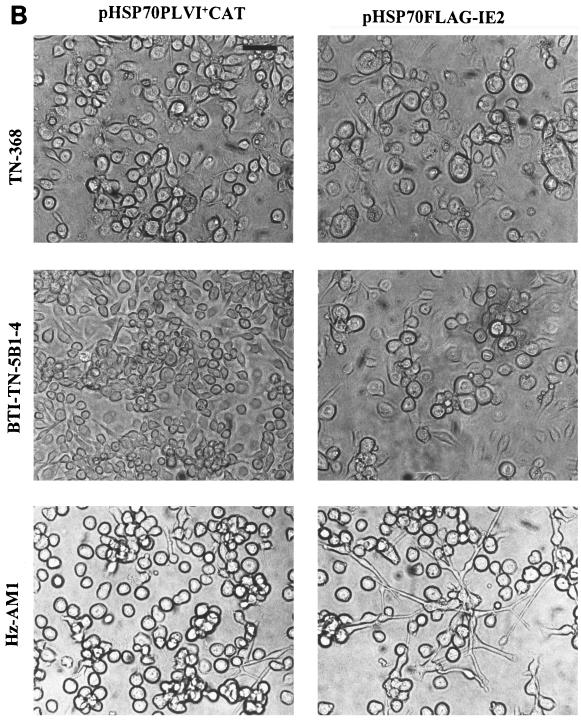

Effects of ie2 expression in different cell lines.

Since the requirement for IE2 in transient expression assays is cell line specific, we analyzed the ability of IE2 to arrest cell division in cell lines derived from other insect species. SF-21, TN-368, BTI-TN-5B1-4, and Hz-AM1 cells were transfected with pHSP70FLAG-IE2 and heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection. At 72 h posttransfection, approximately 50% of the normal numbers of viable cells were obtained in the pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected TN-368, BTI-TN-5B1-4, and Hz-AM1 cells at 72 h posttransfection (Fig. 9A), similar to the reduction in cell numbers observed in the pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected SF-21 cell culture. There was no evidence of apoptosis or necrotic cell death in any of the transfected cultures. Thus, IE2 expression affected the ability of cells to divide, and this resulted in decreases in the numbers of viable cells. This result was confirmed by light microscopic analysis of pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected cells (Fig. 9B). No enlarged cells were observed in control pHSP70PLVI+CAT-transfected cells. In contrast, many of the TN-368, BTI-TN-5B1-4, and Hz-AM1 cells transfected with ie2 exhibited altered cellular morphologies at 72 h posttransfection. A dramatic enlargement of cells was observed in pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected BTI-TN-5B1-4 cells. A less dramatic but nevertheless noticeable increase in cell size was observed in TN-368 cells transfected with pHSP70FLAG-IE2, whereas Hz-AM1 cells expressing IE2 became elongated and had long protrusions at 72 h posttransfection (Fig. 9B). We conclude that AcMNPV ie2 was able to affect the cell division of cell lines derived from other species.

FIG. 9.

Effects of ie2 expression in different cell lines. (A) Percentage of viable cells in pHSP70FLAG-IE2-transfected cultures relative to that observed in control cells transfected with pHSP70PLVI+CAT in each cell line. The cells (0.5 × 106 cells per 35-mm-diameter dish) were transfected with 0.5 μg of pHSP70FLAG-IE2 and heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection. The cells were harvested, stained, and counted at 72 h posttransfection. (B) Morphology of TN-368, BTI-TN-5B1-4, and Hz-AM1 cells transfected with pHSP70FLAG-IE2 or control plasmid. Transfected cells were heat shocked at 18 h posttransfection and photographed at the same magnification at 72 h posttransfection. Cells transfected with pHSP70PLVI+CAT served as controls for normal cell growth and regular morphology. Bar, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a new activity of IE2: cell cycle arrest. SF-21 cells transfected with ie2 cease dividing and eventually contain a single enlarged nucleus with a greater than 4N complement of DNA. Cell cycle arrest appears to occur in the S phase, based on several observations. During the first 24 h following transfection, cells were able to progress from G2 through M to G1 and S, based on the fact that the proportion of cells with a 4N complement of DNA decreased during this period while the proportion of cells in the G1 and S phase (2N and 2N to 4N) increased (Table 1). By 48 h, however, cells with a 4N or greater complement of DNA predominated, indicating that DNA synthesis continued in these cells in an unregulated fashion which precluded transition into G2 and M. There were also no signs of mitotic spindle formation in the ie2-enlarged cells.

The purpose of arresting the cell cycle in S phase remains unclear, although the most obvious possibility would be to provide a nuclear environment which is more conducive to viral DNA replication. However, ie2 is a dispensable gene for both AcMNPV and BmNPV replication in at least some cell lines (13, 35), so cell cycle arrest does not appear to be essential for virus replication in those cell lines. IE2 of BmNPV appears to accelerate viral DNA replication slightly but reproducibly (13), although it is not known whether this effect is due to the transactivation or cell cycle arrest properties of IE2.

The ability of IE2 to arrest the cell cycle requires the presence of the RING finger but appears to be independent of the ability of IE2 to trans-activate gene expression. Deletion of residues 215 to 274, which encompass the majority of the RING finger motif of IE2 (only the first two cysteines of the motif remain), eliminated the ability of IE2 to block the cell cycle but did not eliminate its ability to trans-activate expression from the ie1 promoter. A similar effect was observed for an IE2 mutant with an alteration in a single conserved residue of the RING finger motif. Our observation that modification or deletion of the RING finger motif did not affect the ability of IE2 to trans-activate the ie1 promoter contrasts with the properties of an IE2 mutant described by Yoo and Guarino (48) which precisely eliminated the RING finger motif (residues 207 to 254). This 207-to-254 mutant was found to be severely impaired in its ability to transactivate the ie1 promoter (48). Since a mutant lacking the nine residues just N-terminal of the RING finger (i.e., a mutant deleted between residues 198 and 206) also lacked the ability to trans-activate the ie1 promoter (48), it is possible that residues 207 to 215 are crucial for IE2 trans-activation potential in our 215-to-274 mutant.

The IE2 mutant lacking residues 94 to 173 was unable to trans-activate the ie1 promoter but retained the ability to block the cell cycle, reinforcing the view that the trans-activation activity of IE2 may be unrelated to its ability to influence the cell cycle. Interestingly, the IE2Δ(94–173) mutant not only failed to trans-activate the ie1 promoter but also had a negative effect on its expression. It is possible that this negative effect on ie1-promoted gene expression is due to the arrest of the cells in S phase, in which case IE2 would require a transactivation activity in order to compensate for this negative regulatory effect. However, it is also possible that the mutant form of IE2 interacts with factors affecting ie1 expression in a negative fashion. It is clear that gene regulation by IE2 is far more complex than originally envisioned.

A number of other viruses are known to affect the cell cycle during infection. Smaller DNA viruses such as simian virus 40, papillomaviruses, and adenoviruses depend on many cellular enzymes for viral DNA replication and induce cellular replication factors (reviewed in references 30 and 43). Simian virus 40 stimulates cells to synthesize DNA, and the majority of cells acquire a greater-than-G2 tetraploid DNA content. Human adenovirus E1A proteins induce quiescent cells to enter S phase of the cell cycle by deregulating checkpoint controls, while the E1B proteins block apoptosis and promote a favorable cellular environment for viral replication (10, 14, 36, 39, 45). Large mammalian DNA viruses also arrest the cell cycle during infection. Human cytomegalovirus, for example, seems to inhibit cell cycle progression at multiple points, including the transition from G1 to S (4, 9, 27). The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 causes the accumulation of cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle and stimulates replication (19, 38). In contrast to human immunodeficiency virus type 1, the oncoviruses require host cell proliferation for productive infection (2).

Baculovirus infection has long been known to induce significant changes in infected cells during the first 6 h of infection, including cytoskeletal rearrangements and host chromatin dispersal within the nucleus, which enlarges during this period (47). The ability of baculoviruses to arrest the cell cycle has not been previously reported, and the involvement of a RING finger protein in this process is especially intriguing. Understanding the interaction between baculoviruses and the cell cycle should lead to new insights into viral pathogenesis. We intend to investigate the basis of the host range dependence on IE2 in the context of virus infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Grigori G. Prikhod’ko, Somasekar Seshagiri, and Jeanne McLachlin for technical advice. We are grateful to C. H. Keith (University of Georgia Department of Cellular Biology) for the assistance and reagents necessary for immunofluorescence. We thank S. Hilliard (University of Georgia Cell Analysis Facility) for assistance with flow cytometry.

This research was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AI23719 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayres M D, Howard S C, Kuzio J, Lopez-Ferber M, Possee R D. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:586–605. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieniasz P D, Weiss R A, McClure M O. Cell cycle dependence of foamy retrovirus infection. J Virol. 1995;69:7295–7299. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7295-7299.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnbaum M J, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J Virol. 1994;68:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2521-2528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bresnahan W A, Boldogh I, Thompson E A, Albrecht T. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits cellular DNA synthesis and arrests productively infected cells in late G1. Virology. 1996;224:150–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson D D, Guarino L A, Summers M D. Functional mapping of an AcNPV immediately early gene which augments expression of the ie-1 trans-activated 39k gene. Virology. 1988;162:444–451. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson D D, Summers M D, Guarino L A. Molecular analysis of a baculovirus regulatory gene. Virology. 1991;182:279–286. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90671-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clem R J, Miller L K. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5212–5222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crook N E, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittmer D, Mocarski E S. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits G1/S transition. J Virol. 1997;71:1629–1634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1629-1634.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson N, Harlow E. Adenovirus E1A targets key regulators of cell proliferation. Cancer Surv. 1992;12:161–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett R D, Barlow P, Milner A, Luisi B, Orr A, Hope G, Lyon D. A novel arrangement of zinc-binding residues and secondary structure in the C3HC4 motif of an alpha herpes virus protein family. J Mol Biol. 1993;2334:1038–1047. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freemont P S, Hanson I M, Trowsdale J. A novel cysteine-rich sequence motif. Cell. 1991;64:483–484. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90229-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomi S, Zhoi C E, Yih W, Majima K, Maeda S. Deletion analysis of four of eighteen late gene expression factor gene homologues of the baculovirus, BmNPV. Virology. 1997;230:35–47. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrum F D, Ornelles D A. The early region 1B 55-kilodalton oncoprotein of adenovirus relieves growth restrictions imposed on viral replication by the cell cycle. J Virol. 1997;71:548–561. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.548-561.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarino L A, Summers M D. Functional mapping of a trans-activating gene required for expression of a baculovirus delayed-early gene. J Virol. 1986;57:563–571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.563-571.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarino L A, Summers M D. Nucleotide sequence and temporal expression of a baculovirus regulatory gene. J Virol. 1987;61:2091–2099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2091-2099.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarino L A, Dong W. Functional dissection of the Autographa californica nuclear virus enhancer element hr5. Virology. 1994;200:328–335. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan D O, Landau N R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hink W F. Established insect cell line from the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Nature. 1970;226:466–467. doi: 10.1038/226466b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kool M, Van den Berg P, Tramper J, Goldbach R W, Vlak J M. Location of two putative origins of DNA replication of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1993;192:94–101. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krappa R, Knebel-Mörsdorf D. Identification of the very early transcribed baculovirus gene PE-38. J Virol. 1991;65:805–812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.805-812.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krappa R, Roncarati R, Knebel-Mörsdorf D. Expression of PE38 and IE2, viral members of the C3HC4 finger family, during baculovirus infection: PE38 and IE2 localize to distinct nuclear regions. J Virol. 1995;69:5287–5293. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5287-5293.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovering R, Hanson I M, Borden K L B, Martin S, O’Reilly N A, Evan G I, Rahman D, Pappin D I C, Trowsdale J, Freemont P S. Identification and preliminary characterization of a protein motif related to the zinc finger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu A, Miller L K. Differential requirements for baculovirus late expression factor genes in two cell lines. J Virol. 1995;69:6265–6272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6265-6272.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu A, Miller L K. The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J Virol. 1995;69:975–982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.975-982.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu M, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits cell cycle progression at multiple points, including the transition from G1 to S. J Virol. 1996;70:8850–8857. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8850-8857.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntosh A H, Ignoffo C M. Characterization of 5 cell lines established from species of Heliothis. Appl Entomol Zool. 1983;18:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris T D, Miller L K. Promoter influence on baculovirus-mediated gene expression in permissive and nonpermissive insect cell lines. J Virol. 1992;66:7397–7405. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7397-7405.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nevins J R. Adenovirus E1A: transcription regulation and alteration of cell growth control. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;199:25–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79586-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Reilly D A, Miller L K, Luckow V A. Baculovirus expression vectors: a laboratory manual. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman and Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passarelli A L, Miller L K. Three baculovirus genes involved in late and very late gene expression: ie-1, ie-n, and lef-2. J Virol. 1993;67:2149–2158. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2149-2158.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Person M, Bjornson R, Pearson G, Rohrmann G. The Autographa californica baculovirus genome: evidence for multiple replication origin. Science. 1992;257:1382–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1529337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prikhod’ko E A, Miller L K. Induction of apoptosis by baculovirus transactivator IE1. J Virol. 1996;70:7116–7124. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7116-7124.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prikhod’ko, E. A., A. Lu, and L. K. Miller. Unpublished data.

- 36.Quinlan M P. Enhanced proliferation, growth factor induction and immortalization by adenovirus E1A 12S in the absence of E1B. Oncogene. 1994;9:2639–2647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rankin C, Ooi B G, Miller L K. Eight base pairs encompassing the transcriptional start point are the major determinant for baculovirus polyhedrin gene expression. Gene. 1988;70:39–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Re F, Braaten D, Franke E K, Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J Virol. 1995;69:6859–6864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6859-6864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shepherd S E, Howe J A, Mymryk J S, Bayley S T. Induction of the cell cycle in baby rat kidney cells by adenovirus type 5 E1A in the absence of E1B and a possible influence of p53. J Virol. 1993;67:2944–2949. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2944-2949.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theilmann D A, Stewart S. Molecular analysis of the trans-activating IE-2 gene of Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1992;187:84–96. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiem S M, Miller L K. A baculovirus gene with a novel transcription pattern encodes a polypeptide with a zinc finger and a leucine zipper. J Virol. 1989;63:4489–4497. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4489-4497.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toeroek L, Karch F. Nucleotide sequences of heat shock activated genes in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Sequences in the regions of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the hsp70 gene in the hybrid plasmid 56h8. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:3105–3123. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.14.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tooze J E, editor. DNA tumor viruses. (Molecular biology of DNA tumor viruses, part 2.) Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaughn J L, Goodwin R H, Tompkins G J, McCawley P. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) In Vitro. 1977;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vousden K H. Regulation of the cell cycle by viral oncoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:109–116. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wickhman T J, Davis T T, Granados R R, Shuler M L, Wood H A. Screening insect cell lines for the production of recombinant virus in the baculovirus expression system. Biotechnol Prog. 1992;8:391–396. doi: 10.1021/bp00017a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams G V, Faulkner P. Cytological changes and viral morphogenesis during baculovirus infection. In: Miller L K, editor. The baculoviruses. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 61–96. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoo S, Guarino L A. Functional dissection of the ie2 gene product of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:164–172. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]